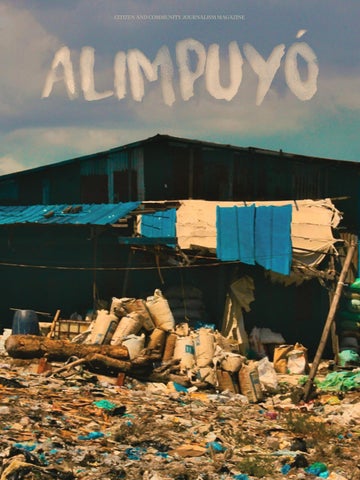

ALIMPUYO

@. Jannes Magayon

Alimpuyó /a·lim·pu·yó/ – a swirling or whirling motion.

There is a kind of motion that doesn’t rush forward—it circles. In forgotten spaces at the margins of our cities, this motion takes shape in smoke rising from heaps of trash, in the rustle of plastic under bare feet, in the breath of people who endure without pause.

This is the alimpuyó of survival— excruciatingly slow, circular, and unending.

Here, life does not unfold—it only circles back. To the same path. The same questions. The same struggle. They build something resembling life from what’s

left behind, not because it’s enough—but because it’s all there is.

This piece enters that quiet, unseen spin. It listens. It lingers.

And it asks, how long can we watch others move in these invisible currents—caught in loops of labor, loss, and longing— without being pulled in ourselves, before we choose to break the pattern??

Because cycles, even the harshest ones, can be broken.

And in every slow turn, there is a chance— may it be small—that the circle becomes a spiral. That it rises. That it leads not back, but forward.

06 | In the Wake of Waste: Caingin’s People of the Pile

NEWS

03 | Living in Limbo: Bulacan Garbage Crisis

04 | The last of RA 9003: An open ended closure of Landfills

FEATURES

10 | Stitching Thread, Mending Lives: Bernardo Gilsano’s Quest Towards Hope

12 | Living Beneath the Shadows of Filth: The Untold Plea of a Resident Living in the Floating Area

MOVIE REVIEW

13 | Manila in the Claws of Light

“Hindi namin pinangarap tumira sa tambakan,” says 65-year old Marcelino Labayo, who has lived on the Caingin dumpsite for 25 years.

After the closure of nearby landfills and mounting government pressure to clear informal settlements, residents like Labayo now face uncertain futures, caught between eviction orders and a lack of relocation options.

In October 2024, the Metro Clark Waste Management Corporation (MCWMC) landfill in Capas, Tarlac, ceased operations, leaving 12 towns in Bulacan scrambling for waste disposal solutions.

This is following a resolution made to stop the ongoing legal disputes with the Clark Development Corporation (CDC) and the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA), both slated to take control of the property.

Upon the expiration of a temporary restraining order (TRO) issued by the Capas Regional Trial Court on October 24, 2024, Kalangitan landfill, as others have come to know it, had ceased its operations entirely, leaving the many dozens of trucks carrying waste from Bulacan and neighboring provinces stranded.

With nowhere left to dump waste from about 1.8 million people across 12 towns in Bulacan, uncollected and collected garbage began spilling out back into the province, refilling waterways, streets or in some cases formerdump sites turned into illegal settlements.

After the collapse of the so-called “Promised Land” in Payatas in 2000 — a tragedy that buried over 200 people under mountains of garbage, public awareness of the dangers of living in dumpsites has significantly increased.

This led to the enactment of RA. 9003 or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, which mandates the closure of open dumpsites and promotes segregation, recycling, and the establishment of sanitary landfills.

However, the statute only reached full implementation in 2021 with over 300 dumpsites closed nationwide.

Illegal settlements began to emerge, taking over the remnants of these decommissioned sites and transforming them into makeshift communities built atop waste.

Such is the situation in Barangay Caingin in Meycauayan, Bulacan, where former dumpsite

land has become home to hundreds of informal settlers living among the heaps of trash which shouldn’t be there in the first place.

The area, home to toxic materials and industrial waste, poses serious health hazards to the residents of the “Floating Dumpsite”.

However, with nowhere else to go, the people of Caingin chose to stay among the garbage, selling and recycling junk despite the meager income, clinging to the only livelihood that keeps them afloat amid threats of eviction and neglect.

“Kung hindi kami makapagpatuyo ng plastic para sa PE class namin, wala kaming kita. Minsan isang araw, wala talaga,” sentiments of Kyle Labayo, a 17-years old student living in Caingin.

Kyle and many residents of the area rely on scavenging and recycling as their primary source of income, doing everything they can and settling for less because this is all they’ve ever known.

Despite the harsh conditions they’ve been set into, they cannot leave the site for it is not just a place to call home, but a workplace—one that, however meager, sustains their day-today survival and gives them a fragile sense of stability in an otherwise uncertain world.

“Sa totoo lang po, ang hirap na ng kabuhayan

dito. Kakaunti na lang ang basura, at minsan wala kaming kinikita.” says 65-year old Marcelino Labayo, a junk collector in Caingin for more than two decades

The waste that they used to collect and sell are also starting to be replaced by irredeemable industrial waste that are often toxic, unusable and dangerous, limiting their livelihood ever further.

Now under the threat of eviction, the people of the “Floating Dumpsite” are uncertain of what their future might hold.

Despite the government-sponsored housing project promised to them, it is still unclear whether it can truly offer residents a dignified life far from the stench, smoke, and struggle they’ve long endured.

Barangay Caingin is far from the only case of communities forced to live among waste due to poverty, lack of housing, and systemic neglect, it is a bane that every developing country must face, to progress without compromising the life and livelihood of their citizens.

Across Bulacan and many parts of the country, there are many more stories where garbage becomes both livelihood and landscape, and where promises of relocation remain vague or unfulfilled.

Fionah Kaye Molod

From a 2020 census noted in PhilAtlas, 4.72% or 139,740 Filipinos are living as informal settlers in the Payatas dumpsite, known as one of the largest slum areas in the Philippines and is currently being redeveloped into an urban park which opens the multifaceted issue involving relocation, livelihood challenges, and community adaptation.

Evidently, the reason behind the persistence of the settlers to live in slum areas is poverty. The offer of free housing is an opportunity to most that can not afford to rent and the availability of recyclable materials created livelihood.

Reliability to the dumpsite deepens as scavenging, vending, or operating junkshops become the usual source of income despite the health risks posed by the environment.

More than the hazardous materials and poor sanitation in the area, it is the lack of infrastructures that provide water, electricity, and other necessities that creates economically vulnerable settlers.

As commented by architect Louie Posadas with the Technical Assistance Movement for People and Environment, Inc. (TAMPEI Philippines) in an interview with Verafiles that the government mostly focuses on addressing the backlogs instead of long term solutions that address the worsening weather condition and humane standards for living.

“The government’s main consideration must be community needs, not numbers, not just resolving the backlog,” stated Posadas

“It’s sad that they arrived here without employment or a source of income. They were really hungry. The toilet bowl was broken. There was no electricity or

water. And their main doors could only be left open. It wasn’t safe, especially if there were young girls. Their safety was violated,” described Suzara.

Such conditions are a direct violation of Republic Act 7279 or the Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992 in which the provision of all basic needs such as water, electricity, proper sewage, and waste disposal must be met.

In the midst of these dilemmas and controversy, another major dumpsite was closed down—except, its a sanitary landfill.

The Commission on Audit (COA) called out Cebu city for their lack of Material Recovery Facilities (MRF) this 2024 thus raising concern of their insignificance toward composting and recycling which causes more expenses.

Reportedly, the Cebu City Government spent more of its budget on garbage collection and tipping fees as the LGU dismissed the utilization of their Php 3 million worth composting facilities and more than Php 50 million unused budget for the establishment of MRFs which is punishable by RA 9003 as it was mandated in law that one of the responsibilities of LGUs is the diversion of at least 25% waste in reuse, recycle or composting.

In the same year, Filipino environmental Justice group BAN Toxics, shared that RA 9003 must be reviewed and applied with stricter enforcement measures.

“RA 9003 is crucial but poorly implemented, and its shortcomings are evident, particularly during floods. There are also unseen effects, such as toxic waste contaminating the environment and posing longterm health risks to communities,” Thony Dizon as the Campaign and Advocacy Officer of BAN Toxics.

At the start of 2024, Senator Jinggoy Estrada probed the labor violations against the International Solid Waste Integrated Management Specialist Inc. (I-SWIMS) after the company allegedly bypassed laws to avoid the responsibility of providing due benefits to its workers as mandated by labor laws.

More than 70 garbage collectors came forward to file a complaint after being employed for 4 years with at least 18 hours of work from 5 A.M. to 11 A.M. but remained labelled as “volunteers”.

Their pay was also below the minimum wage of Php 573 to Php 610 in Metro Manila as they only receive around Php 250 to Php 300 per day without overtime pay and night shift differentials.

The garbage collectors were also required to work on holidays for free, they were also deprived of social protection benefits such as Social Security System (SSS), Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), and Home Development Mutual Fund (PagIBIG Fund).

“Such is a circumvention of the laws, particularly the Labor Code and this is supposedly perpetrated among the garbage collectors whose service to the company and nature of work is essential to its operations,” Estrada stated.

There are also cases of Ghost Projects and Fictitious Projects as found by the COA after a series of LGUs allocated funds to non-existent MRFs that are listed as complete or on-going.

Concludingly, the abrupt actions against open landfills and dumpsites pose a problem to unprepared LGUs, illegal settlers, and the environment while creating opportunities for corrupt officials to abuse the money of the taxpaying Filipinos.

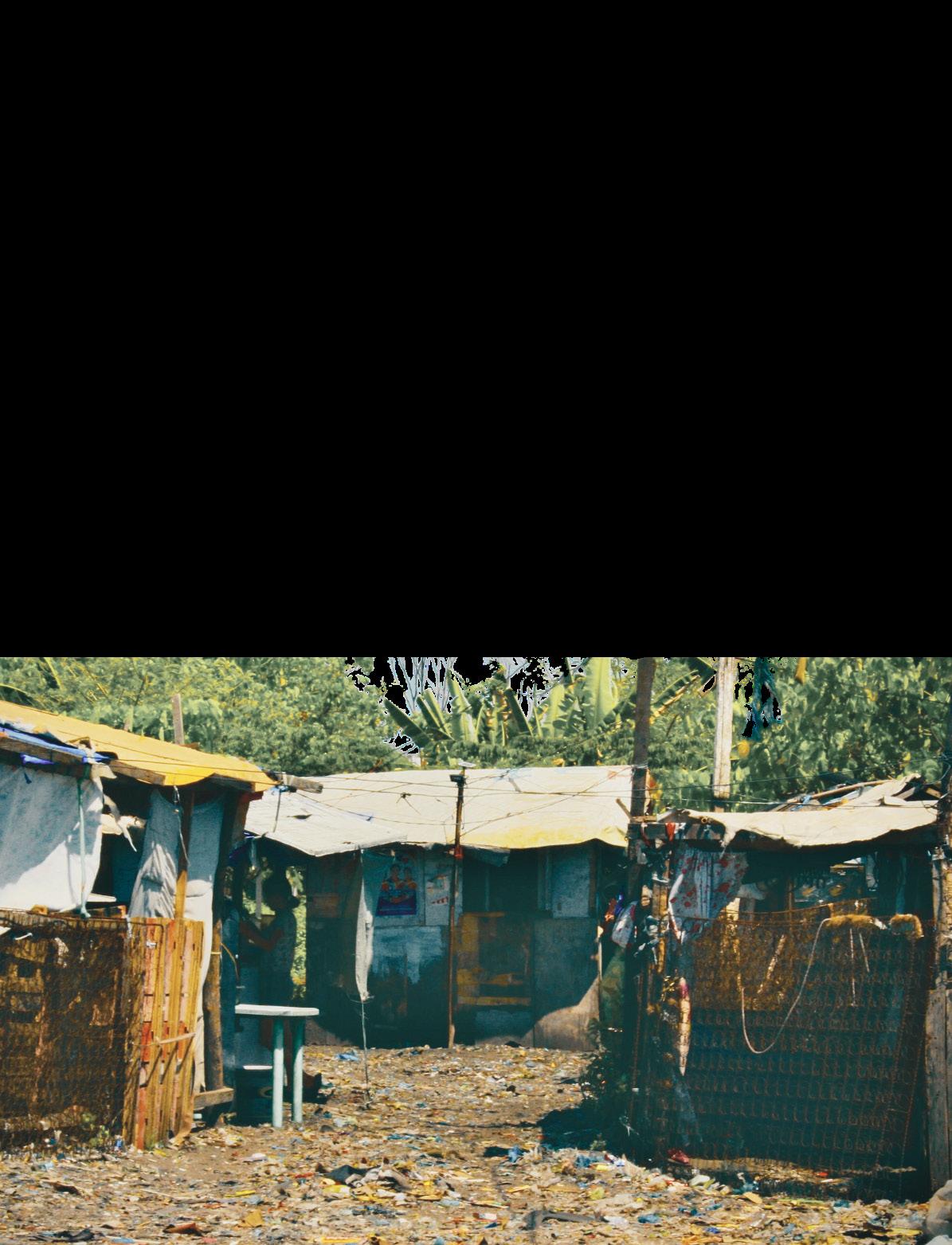

@. Bryan De Jesus

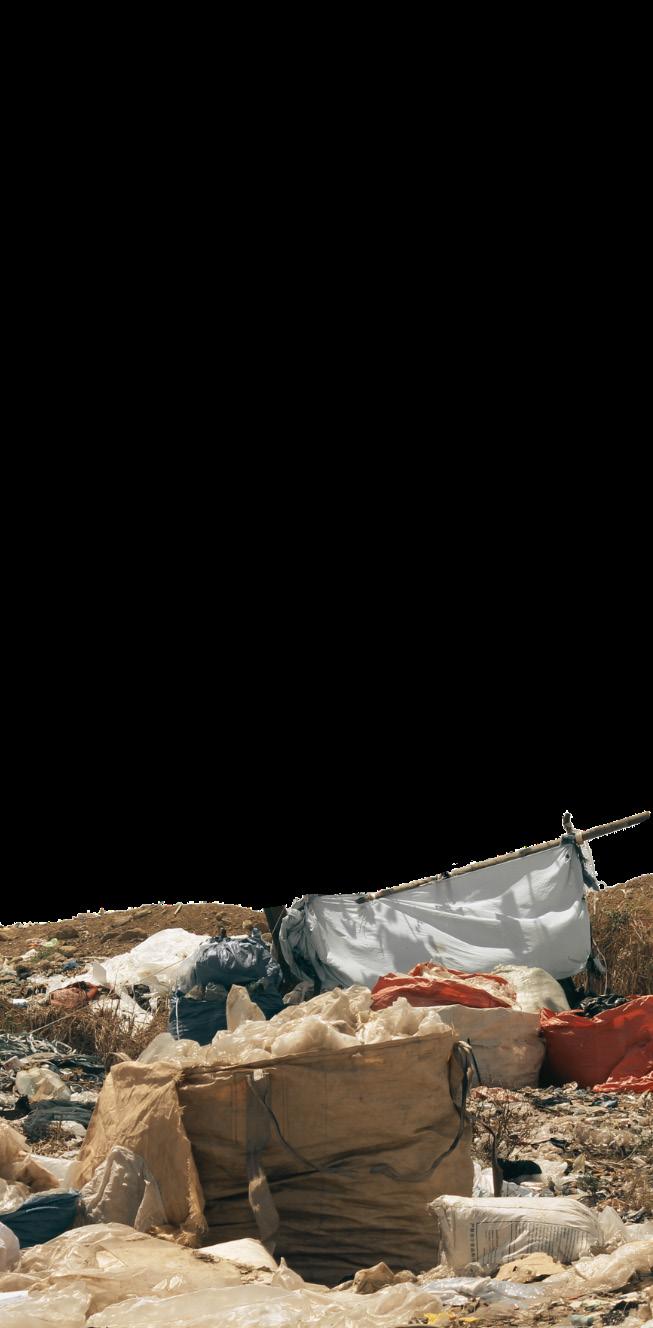

While people wake up in the comfort of their beds, far from the stench and squalor of urban decay, the people of Caingin stirs in a different reality. They wake, breathe, and live in the reek of garbage that never leaves the air. For they are living in the remnants of a dumpsite, the city’s burial for waste has become their home, their lives and a place to belong.

The dumpsite in Barangay Caingin, Meycauayan, was once an open disposal area situated alarmingly close to a tributary of the already polluted Meycauayan River.

Although the City Government of Meycauayan officially decommissioned the site, it was never truly shut down as residents from nearby barangays continue to treat it as an active dumping ground. Over the years, as piles of garbage grew, so did informal settlements, reflecting the degradation of the land itself. But this time, it’s not just waste being discarded, it’s people with nowhere else to go.

The ‘Floating Dumpsite’, as the residents call it houses hundreds of families who live with the waste. Despite the private ownership of the reclaimed land, it has become a place for refugees with nowhere else to turn to.

Aside from serving as a place to live, the dumpsite has also become a source of livelihood for the people of Caingin. The residents mainly scavenge heaps of trash, recycle materials, sell junk and other work that makes ends meet. In their words, as long as the job has dignity, they have no problems with it if they can eat three times a day.

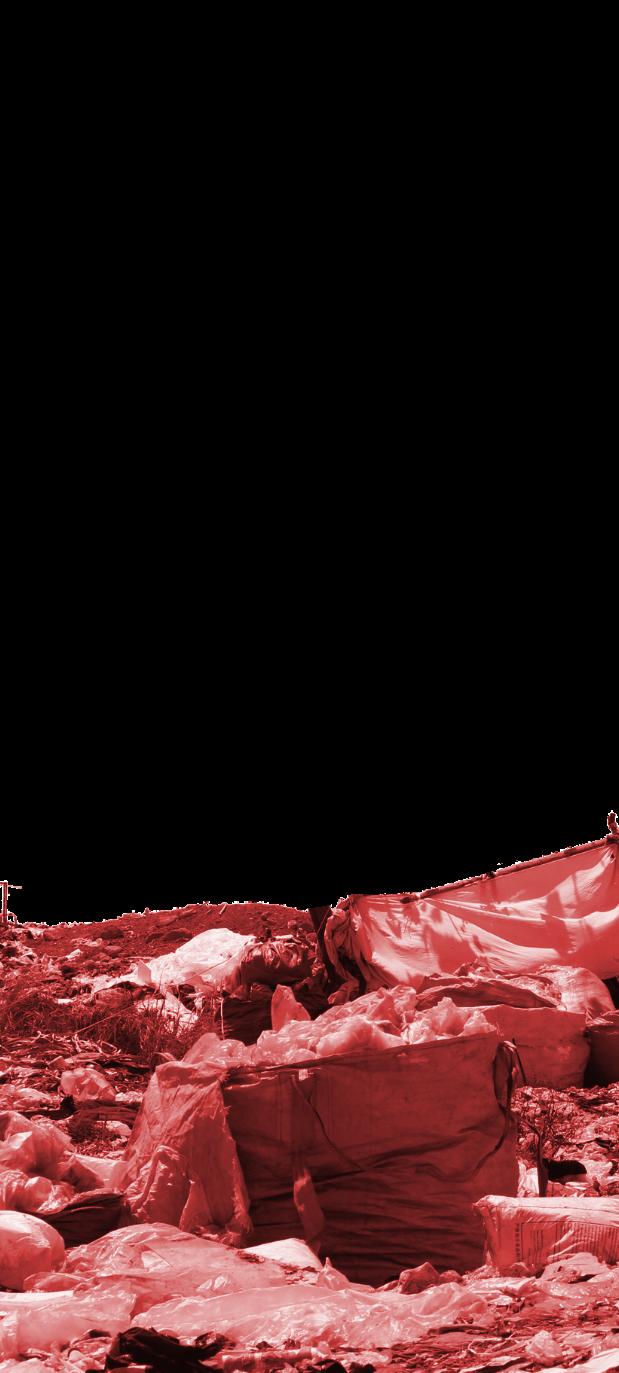

Unfortunately, the land that they are standing on has been subjected through years of industrial waste and has become unstable and toxic due to the chemicals it absorbed.

A study by Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Pure Earth in 2016 both flagged Caingin and the greater Meycauayan-MarilaoObando River System (MMORS) as a critical pollution hotspot. Heavy metals like lead, cadmium, and mercury have been detected in the soil and water, seeping from nearby tanneries, jewelry workshops, and informal e-waste processing hubs.

Due to this, the whole dumpsite is a health hazard and the residents are in constant risk from diseases and ailments they can unknowingly contact.

Moreover, a 2023 study by Cadondon et al. revealed that the air in areas like Caingin contains significant particulate matter and chemical residues, endangering not only the environment but also the respiratory health of residents.

Records of locals experiencing chronic coughing, skin conditions, and a persistent sense of fatigue has been a common trend for the floating dumpsite. It is further exacerbated by the lack of accessible medical assistance from the local government. And yet, despite knowing the dangers, residents continue to stay—because for many, it is the only place they can call home.

Despite the dumpsite being officially closed,

tonnes of waste still manages to find its way to Caingin. ADB reported that the area has been subjected to the continuous disposal of various waste, including hazardous materials that worsens the condition of the site overtime. The root cause mainly being poor and uncontrolled waste management practices around the area.

Inside the mountains and mountains of trash is where the heart of this story lies. The people of Caingin who live amongst the waste are not just passive victims of circumstance, they are survivors. Entire families have built their homes—their lives, on top of these piles of waste. They lived their lives surrounded by trash which is both a lifeline and a lingering threat.

Rosalinda Nabor, a 24 year old housewife considers the floating dumpsite as a blessing in disguise as their stay, albeit informal in arrangement, does not require rent or any major expenses.

“Mahirap pero nasanay na, mas nakakatipid din kami kasi walang binabayarang upa sa bahay” Nabor said in an exclusive interview.

However, people like Melissa are wishing for a housing project from the government due to the impending threat of eviction as the land, no matter how worse it has gotten, is still a private property.

“Gusto sana namin ng pabahay kung sakaling mapa-alis kami dito sa dumpsite, makapagsimula sana ulit ng bagong buhay” Melissa said.

Caingin and the

Air in areas like Caingin contains significant particulate matter and chemical residues

“Okay lang naman sana dito, wala ‘ding choice eh. Dito lang din kami napunta kasi napaalis na kami doon sa may unahan ng dumpsite,” Lea Cuarez, a 26 year old factory worker who have been staying in Caingin for three years shared her sentiments.

“sana rin mabigyan na ng update yung binigay sa amin na relocation form para sigurado nang mayroong lilipatan kapag napaalis na kami dito ng tuluyan.” She added

Aside from the harsh living conditions, the threat of eviction from the dumpsite is like a ticking bomb for the residents of Caingin. Many have lived in the area for years—some for decades— without secure land tenure, building lives on land that was never legally theirs. The shadow of uncertainty is looming and many residents are afraid that the place they once called home would eventually spit them all out.

Another pressing issue that the residents face in

demanded higher educational attainments, which most of the residents are unable to attain due to financial struggles.

At the end of the day, they only know what they’ve lived through, all the routines and the work they are born with in the pile of trash.

According to Barangay Caingin Captain Melanio Alcantara, they have been requesting for more housing from Meycauayan Mayor Henry Villarica, hoping that a concrete relocation plan would finally be set in motion.

Alcantara also reiterated that the barangay can only do so much to alleviate the suffering of the dumpsite residents. However, they reaffirmed their commitment to continue coordinating with the city government and relevant agencies to push

When asked about the state of the floating dumpsite, the local government of Meycauayan was unable to provide a proper statement, as key officials were reportedly unavailable at the time.

While there are existing laws and policies that specifically address urban housing issues like in Caingin. The execution is where the challenge lies.

Republic Act No. 7279 or the Urban Development and Housing Act (UDHA) mandates that local governments provide secure tenure and affordable housing options for informal settlers. Yet, despite this law, many residents remain in dangerous reclamation areas such as Caingin.

There are also government agencies such as the National Housing Authority (NHA) and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) who, on paper, should be the first ones to address these issues. However, due to coordination challenges and resource constraints, it heavily limits their impact to create meaningful change.

In the same vein, Republic Act No. 9003 or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act should have a framework and strategy for proper waste disposal and environmental protection, which is crucial in addressing the continuous dumping and pollution in Caingin. However, just like other laws, enforcement gaps allow illegal dumping to continue, exacerbating the condition of the people further.

The people of Caingin are not just victims of urban decay and societal neglect. They are the products of a systemic failure, yet the embodiment of resiliency.

What Caingin needs is not a temporary relief or band aid fixes, but sustained, long-term interventions that ensure safe housing, access to basic services, and viable livelihood opportunities. Until then, the so-called closure of the dumpsite remains meaningless.

Because for the people living atop the mountains of waste, the struggle for land, life, and dignity continues every single day.

From the gleaming “Jewelry Capital of the Philippines” known for its dashing and exceptional manufacturing, there lies a community who receives the opposite end of that glamour.

In the lively Barangay Caingin of the City of Meycauayan, Bulacan, there is an isolated community who makes the most of the disposed junk that gets dumped on their neighborhood. A growing population to what already is more than 60 families, they drift around a big chunk of soil that keeps them afloat from the groundwater beside a creek.

Their area is what is called in their community as the “Floating”. And just like it, the locals also just flow adrift, waiting for a ripple of change to come.

Floating towards an unsure direction of their tomorrow in the sea of scraps.

To live above a floating area of garbage is to endure. To make ends meet is not for the faint of heart. And to carry on without certainty—when the world offers no security, no comfort—is nothing short of remarkable.

In a place drowned by noise and fast lives, past the factories, beyond the markets, and hidden behind the city’s industrial pulse—is a midst few know, and fewer dare to enter.

Yet, there exists a man in Barangay Caingin, Meycauayan, Bulacan, whose quiet strength whispers a powerful lesson of resilience, and mirrors how the people who live there dare to carry on—even when surrounded by literal mountains of waste.

At an old-age of 64, Tatay Bernardo and his family were once tenants, close to the floating area where he now resides. And because of adversity he relied on making their own home—pieced together from scrap wood, old tarps, and rusting metal.

“Yung kumpare ko kasi dati nakatira diyan sa dulo, matagal na, sabi sa’min, “Pare, baka gusto mo tumirik doon [sa floating area] eh puwede ka naman kaya napasama ako rito.” He said in an exclusive interview.

“Wala naman kaming sariling lupa’t bahay kaya nung nalaman ko na puwedeng magtirik dito, kaya dito kami pati yung mga anak ko.” He added.

And to make it through, Tatay Bernardo clung to the one thing he knew—the steady rhythm of crafting guwantes. In a makeshift workstation inside his small home, he salvaged scraps of fabric handed to him. With painstaking effort, he often earned just enough to get through the week.

“Kasi nung bagong dating ako rito, namamasukan ako kaya nagka-interest ako na bumili ng sariling makina para dito na ako sa bahay gagawa.” He uttered. “Medyo mahina rin ako manahi ngayon [dahil] may edad na. Sa loob ng isang linggo nakaka-tatlong bundle ako, nakaka-ano rin, mga Php 3,300 ang mapapagbentahan ko. Isang libo per bundle.”

For about 46 years of experience and weathered hands in making guwantes, he managed to provide for and send his four children through highschool.

“Walang problema [sa pagbebentahan], sa mga hardware, tapos mayroon ding ahente na umo-order sa’kin. Ide-deliver naman nila ‘yon sa mga factory, mga pabrika.” He shared. “Dito ko pinalaki yung mga anak ko [sa pag-guwantis]. ‘Yan medyo nakakaraos din naman kami.”

STRUGGLES BENEATH THE SURFACE

However, merely surviving is not sufficient for daily life. Tatay Bernardo, and everyone who lives in the floating area shares the same hardships and obstacles, making living there more agonizing— the uncertainty and being uprooted in their home, the steep electricity bills, and the long walk just to fetch water.

“Minsan may mga tumutungo na rito, yung nagclaim sa lupa na ito na sila raw yung may-ari.” Tatay Bernardo explained.

“Tapos, ayun na nga, pinatawag kami sa barangay, nagsalita ako roon, kung sakali naman paalisin ninyo kami, saan naman tutungo yung ibang kasamahan ko diyan. Kasi yung hanap buhay nila, yung tinatrabaho nila ngayong araw na ito, ‘yon yung kakainin nila kinabukasan.” He added.

With quiet courage, he became their voice. He pleaded that if the eviction pushed through, families like his would have nowhere else to go but the streets. Not everyone could afford to rent a house, he explained—because if they could, they wouldn’t have chosen to live in a place that floated on garbage and dreams in the first place.

“Sabi nila paalisin kami at magbibigay sila ng kaunting halaga pam-paumpisa raw. Narinig namin na limang libo raw, sabi ko, saan

makakarating ang limang libo kako niyan?” He shared.

“Kung ido-down sa bahay ‘yan baka kulangin pa ‘yan. Paano pa yung pang-kain, syempre yung ibang tao rito, yung kinakayod nila sa araw na ito, sa hapon, ‘yon din yung pang-kain nila. Ganoon yung kalakaran dito talaga, yung sistema.” Tatay Bernardo imparted.

On top of the looming threat of eviction from the land they call home, their hardships are worsened by the high cost of electricity bills—another weight pressing down on already weary lives.

“Biruin mo, ang bayarin sa pinaka-main, magkano lang, nasa 12 sa isang kilowatts. Dito, 24 para sa isang kilowatts. Double po, ‘yun ang pinaka masakit dito.” Tatay Bernardo admitted honestly.

“Dito 600 kung susumahin, mag-electric fan ka pa, kung ano pa yung gagamitin mo [na appliances]. Pero nung nag-balik 24 per kilowatts yung singil sa’min, hindi namin kaya gumamit nang ganun.”

“Yung TV nga bihira ko lang buksan dahil nga ganoon, napakalaki [nang babayaran]. Minsan nga umabot ako rito nang kulang-kulang tatlong libo, sa isang buwan, ang laki. Kaya ‘yan ang

pinaka-problema.” He said.

And adding to their burden is one of life’s most essential needs—water. A basic right, yet it has become another source of struggle for them.

“Yung tubig, naku, nag-iigib kami doon sa labasan, ang layo. Biruin mo simula dito hanggang doon sa gate, doon kami nag-iigib, araw-araw ‘yan.” He stated in dismay.

“Sa container, minsan kaapg nagpapa-igib ako, halimabawa, yung container na 12 kilos ata yung laman, kapag sa main namin iigibin ‘yon, siyete lang. Kapag pina-igib namin sa tao ‘yon, bente isang container.”

“Minsan kapag kinakapos sa pambayad, magiigib na lang ng dalawang container para may gagamitin na pampaligo, mineral doon pa bibilhin.”

There’s no denying that Tatay Bernardo has weathered the trials of time and every storm life’s hardships have heaved his way.

At an early age, the torch of providing for the family was passed onto him by his father. He could have spent his teenage years in carefree

joy, but instead, he was exposed into the harsh realities of the world.

“Nung kabataan ko kasi, hindi naman talaga ako taga-rito, taga-Leyte ako.” He said.

“Hindi ako nakatapos, kasi yung tatay ko nung nasa grade 4 ako nun, nalaglag sa niyog, ako yung panganay, ako ang umaako ng responsibilidad sa mga kapatid ko. Kaya ‘yon yung nangyari, minsan nga umiiyak ako, sabi ko, grabe talaga ang nangyari sa’kin nung kabataan ko.” He painfully added.

And for Tatay Bernardo, the cruel truth for those forced to break their backs just to survive is— education becomes a privilege that not everyone could afford.

And without that piece of paper—a diploma— decent work remains a distant promise, always out of reach.

“Mahirap kasi talaga yung wala kang nakuha na napag-aralan. Kumbaga hindi ka talaga aangat na makakakita ka nang magandang trabaho.” Tatay Bernardo added. “Wala na kong ibang trabaho kasi wala na akong kakayahan dahil wala nang tatanggap sa’kin.”

Yet despite all the trials life hurled at him, Tatay Bernardo—through his humble craft of sewing

guwantes—managed to carry his family through. With his calloused hands, worn out by years of quiet sacrifice, tell the story of a father who chose persistence over despair.

“Wala na akong ibang pinapangarap ngayon kumbaga magtagal pa kami [ng asawa] para makita at masubaybayan pa namin yung mga apo at anak namin.” He uttered, filled with hope.

“Kung magkakapera, tindahan na maliit lang at tsaka bigasan. Dahil hindi naman namin kaya na mabigat na trabaho dahil pareho kaming may edad na. Hindi na kami maghahangad na maging milyonaryo pa kasi matanda na kami, ayos na sa’min na makakaraos lang ng pang-araw araw naming pangangailangan.”

Indeed, to live above a floating area of garbage is to endure, and Tatay Bernardo persists to see life beyond it.

To make ends meet is not for the faint of heart— strength comes from dwelling and holding on, from learning how to survive the unthinkable.

And to carry on without certainty—when the world offers no security, no comfort—is to make space for hope—that somehow, everything will fall into place, at the right time.

“Siguro naman hindi naiisip ng isang padre de pamilya na sumuko. Kung hindi talagang ipagpatuloy ang hanap-buhay na ganito dahil dito lang kami mabubuhay, dito lang kami makakauha ng pangkain namin.”

In the stillness of dawn, a fragile hope lingers— that someday, they will have a home they won’t need to flee, a life no longer lived on the margins. In a country hurtling toward progress, there are corners where hope clings to survival—places many would rather forget. One of them is a former dumpsite in Barangay Caingin, Meycauayan, Bulacan, where Tatay Marcelino has lived for over thirty years.

Locals call it the “Floating Area”—a fragile mound of refuse hovering over a creek, built on years of discarded waste. Yet to hundreds of families, it is a haven. They have built lives from the remnants others throw away.

A father of fifteen and a scavenger by necessity, Tatay Marcelino’s story echoes from the fringes. It speaks of resilience, sacrifice, and a longing for dignity—a cry for a better life shared by many who walk the same path.

“Nung una, hindi ko alam kung paano kami mabubuhay dito,” he said, his voice steady yet heavy with memory.

“Ang iniisip ko ay kung kailan kami maaalis sa ganitong buhay. Hindi pu-puwedeng sabihin natin na pabayaan nalang. nag iisip din tayo, lahat lahat iniisip ko rin. ” He added.

In a 2023 article by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) reaffirmed its commitment to supporting waste pickers, promising to explore more stable sources of livelihood.

“This sector remains excluded from the value chain of solid waste management, yet they are

vital players,” said Environment Secretary Maria Antonia Yulo Loyzaga during a WWF-Philippines media event.

Often ignored, the informal waste sector plays a critical role in the country’s waste segregation and management. Yet for Tatay Marcelino, the government’s promise of a better life remains a distant ideal.

“Kawawa kami, ‘yun talaga. Kawawa talaga. Kaya nga lang tinitiis nalang namin,” he painfully shared. “kasi kung iaasa namin to wala naman siguro kakayanin ang pamahalaan na tulungan kami. Kaya iniintay nalang namin kung ano matutulong nila.”

Scavengers, most of whom are informal settlers, are often denied access to basic services. Despite facing health and safety risks daily, they continue to depend on waste picking for survival (Ejares et al., 2014).

Meanwhile, a report from the Inquirer highlights that Bulacan officials are crafting contingency plans as the Metro Clark Waste Management Corp. (MCWMC) landfill in Tarlac prepares to close by October. The shutdown could disrupt waste disposal across 12 towns, affecting over 1.8 million residents.

For those in the Floating Area, trash is more than waste—it is home, livelihood, and reality. The thought of being evicted from the only land they’ve known as their own is a shared and silent fear.

“’Yun ang kinakakaba ng isang taong katulad namin. ‘Yon bang pupunta rito para paalisin kami. Hindi naman kami puwede paalisin lang dapat sana may matitirhan kami kung ganun.” he said with visible dismay.

Relocating entire communities from “danger zones” has become common. While often presented as benevolent, studies like Alburo-

Cañete’s Away from Danger? reveal the unintended harms of relocation—especially when it overlooks the deeper needs of the poor.

“At kung palalayasin niyo kami, sana naman may mapuntahan kami. Pero mas kailangan namin ng tulong sa hanap-buhay kaysa sa sapilitang relokasyon,” He uttered.

In 2010, the National Solid Waste Management Commission recognized waste pickers as crucial contributors to a sustainable waste system. The 2022 Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Act opened new possibilities, integrating these workers into formal systems and recognizing their rights.

Secretary Loyzaga underscored the need for local governments to provide financial literacy and livelihood training, and to create better data systems to ensure no one is left behind.

Signed into law on July 23, 2022, the EPR Act aims to curb plastic waste by making large companies responsible for collecting and recycling their product packaging—shifting accountability back to producers and offering new hope for those in the informal waste sector.

Maybe this is what Tatay Marcelino is waiting for. Amid the stench of garbage and the noise of a city looking away, hope still flickers.

His life, and those of his neighbors, force us to confront a difficult truth: progress often erases the stories of the poor, burying their struggles beneath promises of order and cleanliness.

Their fight is not just for land or livelihood—it is a fight for dignity, for a voice, for recognition. And perhaps one day, scavengers like Tatay Marcelino will no longer be dismissed, because in the end, they are simply human—just like us.

Hoping to always take a leap of faith because it takes a strong heart to endure this kind of life.

The light shines for those who are fortunate enough to exist in a place where light reaches them comfortably. But for some, it may not be so giving for they desperately seek for it on the pitch black actuality of their lives - fated to get torn.

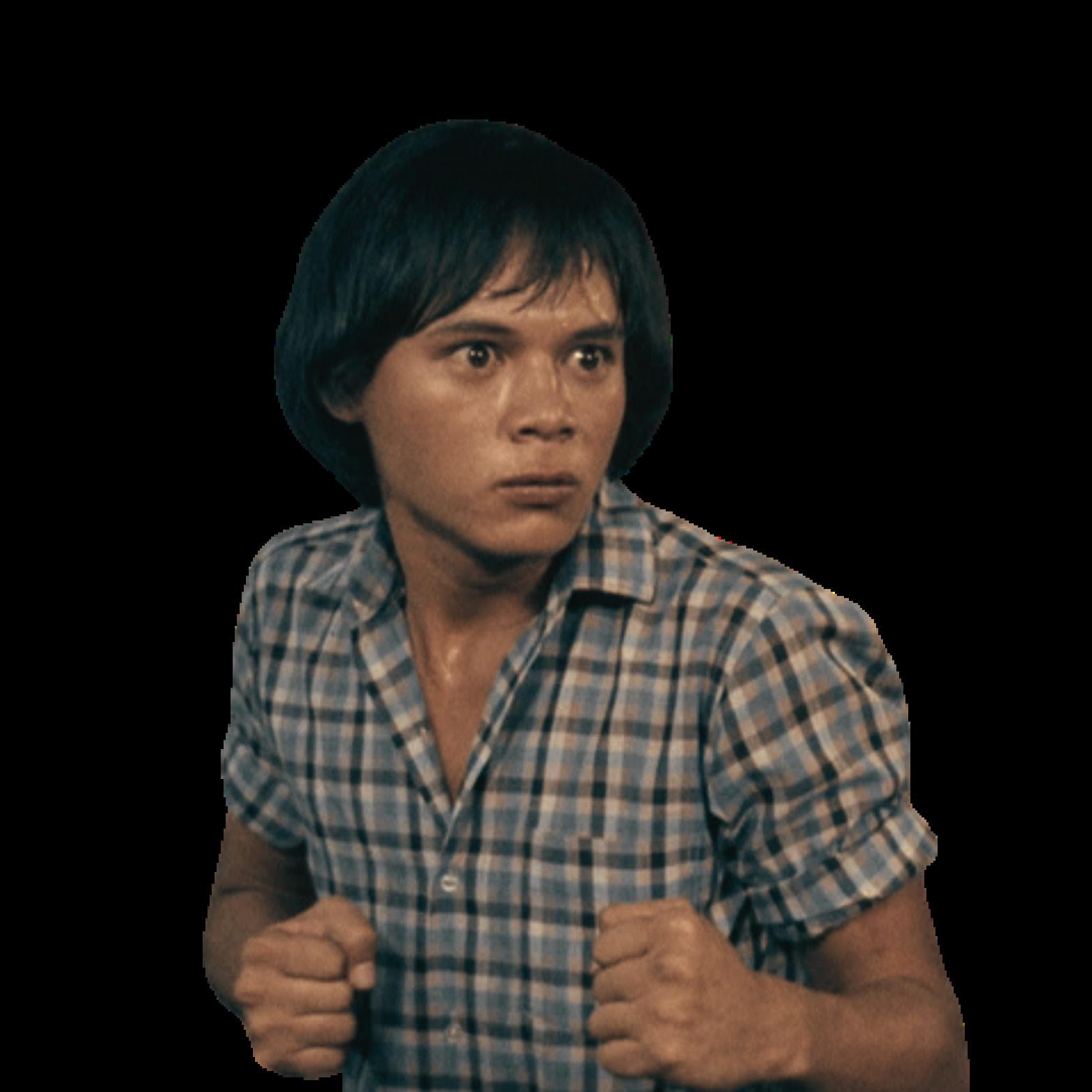

The year of 1975, Lino Brocka orchestrated a piece of film media that was heavily revered as a faultless depiction of social injustice and the harsh realities that we face in our country during that time. 50 years later, it still is more relevant than it should be—a haunting realization as I watched this movie.

Julio, the central character of the film, took off from his province in search of his lost love, Ligaya. Throughout the plot, Julio, despite the hardships that he continuously encounters ever since he set foot in Manila from the death-dealing conditions of his construction work, to finding himself engaging into selling his own body, and the overall dreading weight to be on the deepest slums of society he is constantly always on the lookout for “ligaya”.

Perhaps it is the kind message I have seen in this movie for it portrays the kindle that Filipinos always bring within their hearts despite many storms that come into their lives they always look for that joy that brings light onto their faces.

The film showed how the upper class ceaselessly exploit the vulnerability of people like Julio. Brocka’s vision flawlessly depicted how the poor

can be easily discarded and can be taken away from their privilege to be properly compensated for their efforts.

To this day, it is deeply unsettling to take into realization that looking at this film is as if you were looking towards a mirror that certainly reflects our current society that we have today. In reality, extreme poverty is still a common sight - one where people live in extreme conditions to fend for themselves.

Until today, those people are getting their rights taken from them and being trampled on in full view. Some of those people could not even pay attention to what it could do to their dignity as long as they are living.

Julio, at the end of the film, due to the pressing misfortunes and oppression that he got constantly thrown at, he took justice into his own hands the way he knew it could be brought for no one cared for people like him. Out of the pent up rage he has been gathering inside his heart, that scene gave the raw feeling of reality we have constantly being presented to us. At the end, Julio got killed. But the usual day in town goes on afterwards.

People like Julio and Ligaya have proven how easy it is for their class counterparts to strip away their name and identities, to be sold and used like mere objects for their own pleasure.

The government does not care, they are also the ones who take away.

To this day, people are looking for jobs not even to satiate their wants and needs but just to sustain their struggling lives but greedy employers like to take advantage of that will. People are looking for that light to damp their skins and make them prosper.

Those who are in power could easily bend, stretch, and break people who are beneath them and simply not care. Time goes on for the poor and no one will even remember them.

Watching the film felt like the struggle for a rightful and fair treatment for people like Julio does not simply end once the runtime of the film ends. The film serves as a wake up call but half a century has already passed since the film released, people are still helpless.

I knew that it should start within us to bring forth real change. It is up for the masses to break through that thick wall that separates the untouchable and the exploited. Brocka did not intend to ignite a fire within the hearts of the watchers for it is raw as it gets. You decide what you will do as the watcher to the story that you learned from the film.

The light may not be so giving for others but we must take a stand for the powerles