CALCULATING THE VALUE OF DOWNTOWN AUSTIN, TEXAS

A 2018 IDA STUDY

The International Downtown Association is the premier association of urban place managers who are shaping and activating dynamic downtown districts. Founded in 1954, IDA represents an industry of more than 2,500 place management organizations that employ 100,000 people throughout North America. Through its network of diverse practitioners, its rich body of knowledge, and its unique capacity to nurture community-building partnerships, IDA provides tools, intelligence and strategies for creating healthy and dynamic centers that anchor the wellbeing of towns, cities and regions of the world. IDA members are downtown champions who bring urban centers to life. For more information on IDA, visit downtown.org

IDA Board Chair: Tim Tompkins, President, Times Square Alliance

IDA President & CEO: David T. Downey, CAE

The IDA Research Committee is comprised of industry experts who help IDA align strategic goals and top issues to produce high-quality research products informing both IDA members and the place management industry. Chaired and led by IDA Board members, the 2018 Research Committee is continuing the work set forth in the IDA research agenda, publishing best practices and case studies on top issues facing urban districts, establishing data standards to calculate the value of center cities, and furthering industry benchmarking.

IDA Research Committee Chair: Kris Larson, President & CEO, Downtown Raleigh Alliance

IDA Director of Research: Cathy Lin

IDA Research Coordinator: Tyler Breazeale

International Downtown Association 910 17th Street, NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20006

202.393.6801

downtown.org

© 2018 International Downtown Association, All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form—print, electronic, or otherwise—without the express written permission of IDA.

Stantec’s Urban Places

Project Advisors for The Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities

Stantec’s Urban Places is an interdisciplinary hub bringing together leaders in planning and urban design, transportation including smart and urban mobility, resilience, development, mixed-use architecture, smart cities, and brownfield redevelopment. They work in downtowns across North America—in cities and suburbs alike—to unlock the extraordinary urban promise of enhanced livability, equity, and resilience.

Planning and Urban Design Leader: David Dixon, FAIA

Principal: Craig Lewis, FAICP, LEED AP, CNU-A

Senior Content Manager: Steve Wolf

IDA would like to thank the following individuals for their efforts on the 2018 edition of this project:

Ann Arbor

Susan Pollay

Amber Miller

Xuewei Chen

Atlanta

A.J. Robinson

Alena Green

Austin

Dewitt Peart

Jenell Moffett

Dallas

Kourtny Garrett

Dustin Bullard

Jacob Browning

Doug Prude

Durham

Nicole J. Thompson

Matt Gladdek

El Paso

Joe Gudenrath

Rafael Arellano

Paola Gallegos

Greensboro

Zack Matheny

Jodee Ruppel

Indianapolis

Sherry Seiwert

Catherine Esselman

Tom Beck

Minneapolis

Steve Cramer

Kathryn Reali

Ben Shardlow

Oklahoma City

Jane Jenkins

Jill Brown DeLozier

Phi Nguyen

Tucson

Kathleen Eriksen

Zachary Baker

Ashley La Russa

No city or region can succeed without a strong downtown, the place where compactness and density bring people, capital, and ideas into the kind of proximity that builds economies, opportunity, and identity. Despite a relatively small share of a city’s overall geography, downtowns deliver significant economic and community impacts across both city and region. Downtowns serve as the epicenter of commerce, capital investment, diversity, public discourse, and knowledge and innovation. They provide social benefits through access to community spaces and public institutions. They play a crucial role as the hub for employment, civic engagement, arts and culture, historical importance, local identity, and financial impact.

their space demands – be they residents or ‘those who, due to their work or interests, are potentially the most enthusiastic participants in city life’, the seat of government representation and key offices of both public and private organizations, and other functions that have an urban, regional, national or international significance.”1 This analysis explores downtown’s performance with a data-based look at how it contributes to the city and region around it.

More than anywhere else in our cities, downtowns and center cities transform in response to the needs of changing stakeholders. They reflect national economic and social trends. They serve as models of flexibility, dynamism, diversity, efficiency, and resilience on multiple levels. The power of a downtown and center city “is rooted in its concentration of exceptional and highly significant functions – those that have a high ratio of human experience to Informed by experts and downtown leaders from around the country, this analysis encompasses more than 100 key data points over two time periods (current year and historical reference year); over three geographies (downtown, city, and region); and across 33 benefits. Evaluating downtowns on five interrelated principles—

After a long period of decline in the middle and late 20th century, U.S. downtowns have experienced a resurgence in growth, livability, accessibility, and economic output. Over the past two decades, all but five of the fifty largest downtowns and central business districts (CBDs) in the U.S. experienced residential population growth; only two exhibited declines.2 U.S. downtowns stand poised to continue building their economic and political prominence to match their cultural and historical value.

This project begins to unpack these trends, quantifying the value of American downtowns.

Economy, Inclusion, Vibrancy, Identity, and Resilience—our analysis does three things: it articulates the multifaceted value of the American downtown, highlights downtown’s crucial impacts on a much broader area, and standardizes metrics to help measure how American downtowns and center cities deliver for city and region.

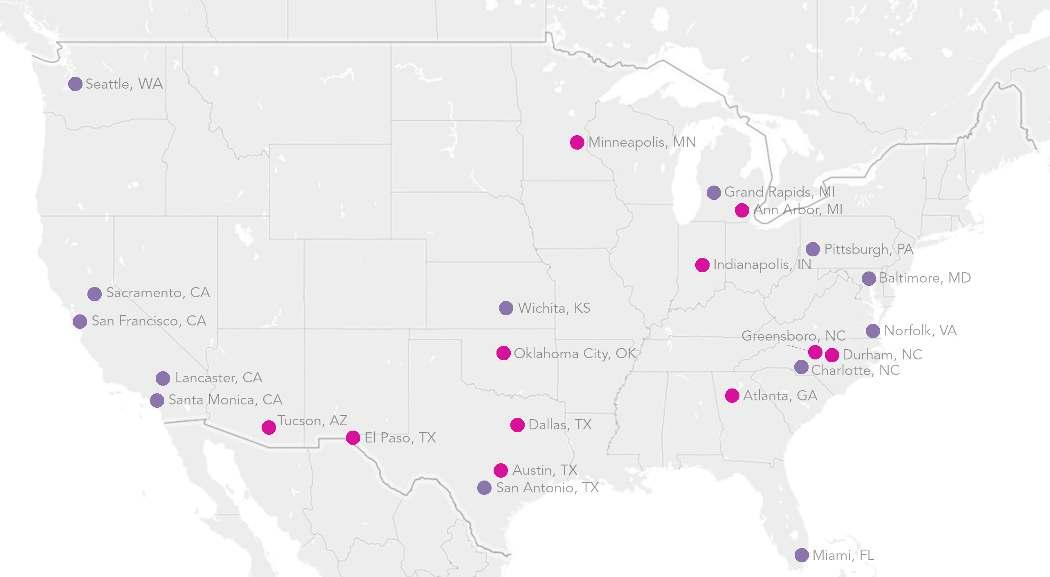

2018 marks the second year of the International Downtown Association’s work on The Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities. In 2017, IDA and Stantec’s Urban Places worked with 13 urban place management organizations (UPMOs) to develop a methodology for compiling and evaluating data from their center cities. Our analysis focused on trends and inherent qualities that highlighted downtowns’ contributions to the cities and regions around them. In 2018, we added 11 UPMOs to the original group to build an even broader understanding of the benefits of downtown investment.

The project aims to emphasize the importance of downtown, to demonstrate its unique return on investment, to inform future decision making, and to increase support from local decision makers. Informed by the award-winning Value of Investing in Canadian Downtowns, the initial iteration of this project:

• Created a framework of principles and related benefits to guide data selection for measuring the value of downtowns and center cities.

• Determined key metrics for evaluating the economic, social, cultural and environmental impacts of American downtowns.

• Developed an industry-wide model for calculating the economic value of downtowns, creating a replicable methodology for continued data collection.

• Convened various downtown organizations to help shape the IDA data standard and the key metrics for evaluating the impact of downtowns.

• Provided individual analysis and performance benchmarks for 13 pilot downtowns with this new data standard, including supplemental qualitative analysis.

• Empowered and continued to support IDA members’ economic and community development efforts through comparative analysis.

• Increased IDA’s capacity to collect, store, visualize, aggregate and benchmark downtown data over time.

The cohort of downtowns that took part in creating the 2017 Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities shaped its principles, methods, and value statements. They identified the most relevant metrics for measuring the value of downtowns. They included 13 UPMOs across the U.S. (Baltimore, Charlotte, Grand Rapids, Lancaster, Miami, Norfolk, Pittsburgh, Sacramento, San Antonio, San Francisco, Santa Monica, Seattle, and Wichita), which actively participated in testing this new industry-wide standard. This year we expanded the analysis to include UPMOs from Ann Arbor, Atlanta, Austin, Dallas, Durham, El Paso, Greensboro, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, and Tucson.

IDA and the pilot downtowns indicated the following top priorities for the study:

ENABLE ARTICULATION OF DOWNTOWN’S IMPORTANCE AND VALUE TO A RANGE OF STAKEHOLDERS.

CREATE A USEFUL SET OF TOOLS FOR REPLICABLE, DATA-DRIVEN MEASUREMENT OF VALUE.

DEFINE A BASELINE FOR ASSESSMENT OF PROGRESS AND PEER COMPARISON.

A downtown “has an important and unique role in economic and social development” for the wider city.3 Downtowns “create a critical mass of activities where commercial, cultural, and civic activities are concentrated. This concentration facilitates business, learning, and cultural exchange.”4

To measure the value of downtowns in relation to their cities, the analysis relied heavily on data that could be collected efficiently and uniformly for a downtown, its city, and its region. To tell the full story of a downtown’s impact, we chose boundaries to capture all of downtown, not just the area in which a UPMO, such as a business improvement district, might operate. To measure the relative densities of downtown and citywide inputs, we normalized the metrics by area, per resident, and per worker.

“ ” DOWNTOWNS HAVE ‘AN IMPORTANT AND UNIQUE ROLE IN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT’ FOR THEIR CITIES AND ‘CREATE A CRITICAL MASS OF ACTIVITIES WHERE COMMERCIAL, CULTURAL, AND CIVIC ACTIVITIES ARE CONCENTRATED. THIS CONCENTRATION FACILITATES BUSINESS, LEARNING, AND CULTURAL

EXCHANGE.’ International Downtown Association

i Refer to the appendix for the full methodology.

This project analyzes the value of a downtown within its city, slicing key metrics by change over time, value per square mile, value per resident, and share of city in the areas of economy, inclusion, vibrancy, identity, and resilience. The resulting value calculation focuses on the compelling metrics generated from the core indicators. The data metrics include:

Economy: employment, tax revenue, assessed value

Inclusion: diversity, education level, housing and rent prices

Vibrancy: retail sales, demand, density, market vitality, population growth

Identity: events, destinations, visitors, downtown hashtags

Resilience: environmental, social and economic resilience, including mode share and community resources

The project focused on creating the framework, selecting and weighting data metrics, collecting the data, creating and applying the valuation methodology, providing individual downtown and aggregate analysis of the participating cohorts, and building a baseline dataset.

Downtowns and center cities occupy a small share of city land area but have substantial regional economic significance. As traditional centers of commerce, transportation, education, and government, downtowns frequently function as economic anchors of their regions. Because of a relatively high density of economic activity, investment in the center city provides a greater return per dollar than in other parts of the city. Just as regional economies vary, so do the economic profiles of center cities—the relative concentration of jobs, economic activity, retail spending, tax revenue, and innovation varies across our sampling. Comparing the economic role of downtowns and center cities to the larger city or region is useful in articulating downtowns’ unique value, as well as in setting development policy.

Downtowns and center cities welcome all residents of the region, as well as visitors, by providing access to opportunity, essential services, culture, recreation, entertainment, and civic activities. Though the specific offerings of each downtown may vary, they share the attributes of density, accessibility, and diversity, which promotes this access.

Thanks to a wide base of users, downtowns and center cities can support a variety of retail, infrastructure, and institutional uses that offer broad benefits to the region. Many unique regional cultural institutions, businesses, centers of innovation, public spaces, and activities are located downtown. The variety and diversity of offerings respond to the regional market and reflect the density of downtown development. As downtowns and center cities grow, their density—of spending, users, institutions, businesses, and knowledge—allows them to support critical infrastructure, such as public parks, transportation services, affordable housing, or major retailers that can’t function as successfully elsewhere in the region.

Downtowns and center cities preserve local heritage, provide a common point of physical connection for regional residents, and actively contribute to the brand of their region. Combining community history and personal memory, a downtown’s cultural value plays a central role in preserving and promoting the region’s identity. Downtowns and center cities serve as places for regional residents to come together, participate in civic life, and celebrate their region, which in turn promotes tourism and civic society. Likewise, the “postcard view” visitors associate with a region is virtually always an image of the downtown.

Broadly defined, resilience means a place’s ability to withstand shocks and stresses. Because of the diversity and density of resources and services, center cities and their inhabitants can better absorb economic, social, and environmental shocks and stresses than their surrounding cities and regions. The diversity and economic strengths of downtowns and center cities equip them to adapt to economic and social shocks better than more homogenous communities. Consequently, they can play a key role in advancing regional resilience, particularly in the wake of economic and environmental shocks that disproportionately affect less economically and socially dynamic areas.

This study has adopted a definition of the commercial downtown that moves beyond the boundaries of a development authority or a business improvement district. For one thing, geographic parameters vary across data sources and may not align with a UPMO’s jurisdiction. IDA’s Value of Investing in Canadian Downtowns report expresses the challenge well:

“Overall, endless debate could be had around the exact boundaries of a downtown, what constitutes a downtown and what elements should be in or out. Yet it is the hope of this study that anyone picking up this report and flicking to their home city will generally think: Give or take a little, this downtown boundary makes sense to me for my home city.”5

Like our Canadian study, this project worked to resolve the challenges of comparative boundary setting. IDA adopted a commonly understood definition for each downtown, using boundaries of hard edges, roads, water, natural features or highways. IDA worked with each UPMO to determine the boundaries of their downtown for this project, with a focus on aligning with census tracts for ease of incorporating

data from the U.S. Census. Within these boundaries, IDA measured multiple factors falling under each principle, looking at trends over time, proportion to the overall city, growth, and city share. The results suggest how a downtown proportionally contributes to its city in a given field, over time, per resident or per square mile.

“

” DOWNTOWNS ARE LIVING, BREATHING THINGS THAT EVOLVE OVER TIME. THEIR BOUNDARIES WILL CHANGE AS TIME GOES ON, AND THAT’S JUST PART OF THE INEVITABLE NATURE OF 21ST CENTURY URBANISM.

Centro San Antonio

Urban place management organizations lead the resurgence in downtowns and center cities by advocating for targeted investment designed to activate and maintain vibrant, accessible, and welcoming downtowns. These UPMOs—including business improvement districts, downtown development authorities, and other publicprivate partnership groups—successfully bring together a broad range of stakeholders, provide place-based leadership, and bridge the gap between the public and private sectors. Since 1970, property and business owners in cities throughout North America have realized that revitalizing and sustaining vibrant and coherent downtowns, central business districts, and neighborhood commercial centers require special efforts beyond the services municipalities alone can provide. Inspired downtown leadership complements these efforts, builds downtown confidence, and strengthens the urban place management industry. The industry has grown at a rapid

“

” WITHOUT A DOUBT, A SUCCESSFUL DOWNTOWN IS CRITICAL. THE CITY’S INVOLVEMENT IS EVEN MORE SO. DOWNTOWNS DON’T HAPPEN – MOST OF THEM HAVE TO BE NURTURED AND WORKED ON FROM BOTH THE PUBLIC AND THE PRIVATE SIDE.

International Downtown Association rate, with approximately 2,500 urban UPMOs in North America and an estimated 3,000 total globally.

The success of a downtown hinges on multilateral cooperation among individuals, developers, employers, and institutions aiming to reach the same revitalization goals. Ensuring continued investment, UPMOs must continually articulate the value of center cities, not only to obvious allies but also to external stakeholders who benefit from downtown but may not recognize the role they play in helping ensure their downtown’s economic, social, and civic success. Most downtowns “have active business improvement districts that have taken on critical leadership roles: they have improved the management of the public realm, offered strong advocacy for the area among public and private decision-makers, provided up-to-date research, funded capital improvements, and promoted long-term planning.”6

Constantly evolving in response to local needs and challenges, downtowns and center cities are never “done.” They require continuous investment, improvement, and development to stay vibrant and economically competitive. Every downtown featured in this report is a distinctive place, with its own history, culture, land use patterns and politics. Some downtowns serve as important drivers of economic performance and lynchpins of regional identity, and these contextual differences matter.

This project applies a range of metrics to quantify how each of 24 downtowns supports its city and region in five critical areas: economy, inclusion, vibrancy, identity, and resilience–our five ‘principles’ of downtown value. Our relatively small sample of 24 does gain representational power by its selection of downtowns that operate across a range of geographies and within widely varying contexts. Nevertheless, we recognize that its extrapolations may not apply to every downtown across the U.S. Since the data come predominantly from the 2015 and 2016 American Community Surveys (ACS) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, some metrics may not align precisely with more recent data from local downtown, municipal, or

proprietary sources. However, our methodology focuses on the proportion of downtowns’ contributions to their cities and regions to highlight their impacts. This analysis restricted itself to publicly available data to make sure that organizations without access to proprietary data could replicate it (although some downtowns do compile or have access to such data).

We chose only data sources with which we could measure both downtown and citywide performance to assure applesto-apples comparisons.

Additional challenges included difficulty acquiring data from partners or unavailable data; the length of time required to get information from partners or city departments; the need for the political will and relationships to acquire such data; a lack of municipal data broken out at the downtown level; defining downtown boundaries that best align with data sources; acquiring updated data from all sources; acquiring full sets of municipal finance indicators; a lack of GIS shapefiles; and the perennial challenges of timing, funding, and staffing capacity.

Compared to the first year, downtowns added as part of the 2018 cohort benefitted from additional analysis on regional comparisons and the inclusion of safety indicators. As this project continues to evolve, future iterations should add:

• Public health indicators

• Housing-affordability implications

• Analysis of residential patterns in downtown-adjacent neighborhoods

The next round of downtowns will apply the methodology established in the first two iterations of this analysis, incorporating several of these additional points. IDA, working with Stantec’s Urban Places, will also release a Downtown Vitality Index that represents a global standard for measuring downtowns in an interactive method online.

These terms appear throughout the report:

Average Daily Pedestrian Traffic The methodology for arriving at this figure can vary by municipality. Typically, downtowns provided a figure representing average daily pedestrian traffic on one of their busier streets.

Census Tract is a small, relatively permanent statistical subdivision of a county or equivalent entity, updated by local participants prior to the decennial U.S. census.

Census Block Group is a statistical division of a census tract, generally defined as containing between 600 and 3,000 people and used to present data and control block numbering in the decennial census.

Commercial Use is defined as any non-residential use.

Creative Jobs are represented by a downtown’s share of citywide and regional Arts and Entertainment jobs, as defined by the federal government’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Deliveries are the total square footage of real estate property bought or sold.

Destination Retail includes clothing, electronics, and luxury goods stores, as defined by the federal government’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Event Venue includes publicly accessible venues typically used for public events such as conferences, conventions, and concerts. Each participating downtown organization compiled its own list, a method that built some subjectivity into the lists: the downtown had the final say on, for example, whether a venue is not fully publicly accessible but is nevertheless part of the fabric of the event community and should be included.

Knowledge Industry Jobs include jobs within these industries, as defined by the federal government’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS): Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Rental and Leasing; Management of Companies and Enterprises; Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services; Information; and Health Care and Social Assistance.

Middle-Class This study uses national definitions of employment earnings to define middle-class and middleincome demographic groups. This definition does not necessarily reflect the number of people who self-identify as middle-class, nor does it capture those who have achieved certain aspirations, such as owning a home, having retirement savings, or sending children to college. The U.S. Census defines middle-class or middle-income earnings as annual household income of $40,000 to $100,000.

• Attainable middle-class rent means monthly rental rates between $800 and $1,500 a month, as defined by the U.S. Census.

• Attainable middle-class housing prices means unit sale prices between $300,000 and $750,000, as defined by the U.S. Census.

Professional Jobs the Professional, Scientific, and Technical services sector is part of the Professional and Business Services supersector, coded 541, within the federal government’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Rent-Burdened households are defined in the U.S. Census table B25070, which measures gross rent as a percentage of household income in the past 12 months. Rent-burdened populations represent the sum of households paying more than 30 percent of household income for rent.

Retail Demand measures the total spending potential of an area’s population, determined by combining residential population and household income characteristics.

Public Capital Investment is defined by each downtown individually but typically includes municipal, state, and federal investment in capital projects such as infrastructure and open space projects within downtown boundaries as defined for this analysis. Some downtowns could only collect data for a subset of public investments such as municipal public investment. In those instances, a footnote indicates the absence of data from the other sources. The timeframe is the most recent full year available (2017).

Square Footage To estimate square feet of built uses, we assumed residential units measured 1,000 sq. ft and hotel rooms measured 330 sq ft.

Public and Private Investment comprise total annual investment by the public and private sectors into a downtown.

A city’s strength and prosperity depend on a strong downtown and center city, which serve as centers of culture, knowledge, and innovation. The performance of downtowns and center cities strengthens the entire region’s economic productivity, inclusion, vibrancy, identity, and resilience.

DOWNTOWN PARTNER

Downtown Austin Alliance

CITY

Austin, TX

Austin is a world-class tech hub, leading the nation in population and economic growth since the recession. Downtown is the iconic cultural capital of this fastgrowing city, charming residents and visitors with its fiercely authentic sense of place, identity, and volume of experiential offerings. It is also a breeding ground for new tech, with a vibrant startup scene and numerous small to medium sized tech offices.

Downtown Austin has experienced fast-paced residential population growth and a boom in housing development. The number of residential units increased 66% between

2010 and 2018 to reach 9,400. Using residential units as an indicator, the Downtown Austin Alliance (DAA) estimates the current downtown population is around 14,000 residents, a 237% increase since 2000.1 Developers continue to add new housing, with another 3,300 units either under construction or in planning. Factoring in the housing units in the pipeline, the population of downtown could exceed 19,000 within the next few years.

For the purposes of this study, we will use the most recent American Community Survey population estimates which counted a total of 6,840 residents in 2016. This number is the base for other demographic and characteristics and for consistency for comparisons with the other downtowns in this study.

15% of all jobs in Austin are downtown. In the past five years, 2013–2018, employment has grown almost 20% downtown and slightly faster citywide at 23%. There is undeniable demand for locating businesses downtown. Downtown has nearly 20% of the city’s office space, and office rents are higher on average than rents citywide, indicating that businesses are willing to pay a premium for downtown space. The office space inventory has grown 17% and first floor retail space has grown 4% since 2010.

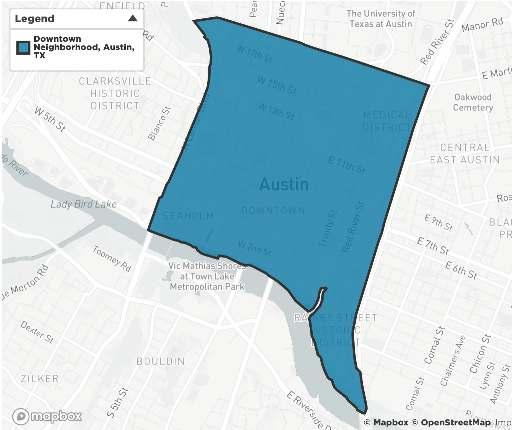

Defining Boundaries

This study area extends beyond the boundaries of the downtown public improvement district, as geographic parameters vary across data sources and don’t typically align with a place management organization’s jurisdiction. IDA recommended that the urban place management organizations participating in this study use the commonly understood definition of downtown and match boundaries to hard edges, roads, water, natural features or highways. IDA worked with each group to align its downtown study area with census tract boundaries for ease of incorporating publicly available data from the U.S. Census.

We defined downtown as the area bounded by East Martin Luther King Jr Blvd. on the north, I-35 on the east, Shoal Creek on the west, and the Colorado River on the south. This geography comprises census tracts 7 and 11. The city is the City of Austin, and the region is the Austin-Round-Rock metropolitan statistical area.

IDA measured multiple factors within each value principle, focusing on trends and growth over time and how downtown compared to the city and the region. These five central principles—economy, inclusion, vibrancy, identity, and resilience—were identified in workshops with the first cohort of urban place management organizations evaluated for this study. Page 44 in Appendix 1 lays out the principles and 33 sub-benefits used to choose the study’s metrics. Our goal was to build a deeper understanding of downtown’s contribution to citywide and metro-area performance across a range of areas.

Downtowns make up a small share of their city’s land area but have substantial economic importance.

While downtowns and center cities constitute a small share of citywide land area, there’s no understating their regional economic importance. As traditional centers of commerce, transportation, education, and government, downtowns serve as economic anchors for their cities and regions. Thanks to highly concentrated economic activity, investment in the center city yields a high level of return per dollar. Analyzing the economic role of downtowns and center cities in the larger city and region highlights their unique value and provides a valuable guide for development policy.

A downtown’s diversity and density of resources and services better positions it to absorb economic shocks and stresses than suburbs and less dense regions. Research suggests that, when compared to suburbs and edge cities, “downtowns have been a little more resilient during the downturn and possess certain sectors with the potential for recovery.”2

Benefits of Economy: Economic Output, Economic Impact, Investment, Creativity, Innovation, Visitation, Spending, Density, Sustainability, Tax Revenue, Scale, Commerce, Opportunity

Downtown Austin is an economic driver for the city, contributing more than $530 million in tax revenue in 2017. Tax revenue generated downtown represents a major asset to the city. Despite its small geographic area, downtown accounts for 9% of all property tax, 44% of all hotel tax, and 10% of all sales tax in the city. Since 2015, the amount of hotel tax and sales tax generated has increased 18%.

National findings indicate that the more valuable real estate in a metropolitan area is increasingly found in revitalized downtowns, and downtown Austin is no exception.3 It has

high combined assessed value due to significant investment and demand. With an average value of $16 million per acre, downtown land is 20 times more valuable than the citywide average. Assessed value per acre is high relative to other downtowns in our study, reaffirming downtown Austin’s appeal even at the national level.

Downtown’s 92,000 workers account for 15% of the worker population citywide. Downtown workers have an array of employment opportunities, with the highest counts in public administration; professional, scientific, and technical services; and accommodation and food services. In aggregate, these three sectors employ 63% of all downtown workers.

A 2017 report from global real estate firm Savills, Tech Cities 2017, ranked Austin as the world’s number-one tech destination.4 The report examined nearly 100 factors to rank tech hubs’ attractiveness to tech companies. The report highlighted Austin’s tech environment, talent pool, low real estate costs, and vibrant startup scene as its strongest assets.

Research confirms that businesses in multiple sectors across the U.S. increasingly choose to locate in downtowns “to attract and retain workers, to build brand identity and company culture, to support creative collaboration, to centralize operations, to be closer to customers and business partners, and to support triple-bottom-line business outcomes.”5 The concentration and wide array of professional fields present in downtown speak to its appeal to a diverse talent pool and the employers who need them. While the biggest tech companies in Austin have independent campuses outside of downtown, many smallto-medium businesses and secondary offices for larger firms have set up shop downtown. Facebook, Netspend, Google, Cirrus Logic, and Silicon Labs are the five largest tech offices downtown, with a combined 2,700 employees. Indeed will add another 3,000 employees in the next few years with many of them located in a 37-story downtown tower currently under construction. Knowledge industries account for 37% of jobs in downtown – roughly 34,000 jobs in total.

Downtown Austin attracts higher wage earners, reflecting national trends, with the share of educated and more affluent residents living in the urban core increasing across the 118 largest U.S. metropolitan areas since 1980.6

Several large tech companies have built campuses outside of downtown, a pattern that helps explain downtown’s relatively low share of citywide knowledge jobs. Leading examples include Dell’s 13,000 employees, Apple’s 6,000 employees, and IBM’s 5,400 employees, all working at campuses outside of downtown. Downtown also has a low share of the city’s creative jobs. According to a report from Austin Music People, conducted by a local consultant in economic development, Austin’s music industry lost more than 1,200 jobs between 2010 and 2014.7 Deeply concerned by this trend, the Austin City Council adopted a measure to fund programs designed to help the music industry.8

Downtown

Austin’s assessed value is $17B, over 10% of the city’s total assessed value

Downtown $16M

Downtowns and center cities invite and welcome residents and visitors by providing access to opportunity, essential services, culture, recreation, entertainment, and participation in civic activities.

Benefits of Inclusion: Equity, Affordability, Civic Participation, Civic Purpose, Culture, Mobility, Accessibility, Tradition, Heritage, Services, Opportunity, Workforce Diversity

Inclusion “is one of the many common characteristics of vibrant and thriving downtowns across the nation…Great downtowns are inherently equitable because they enable a diverse range of users to access essential elements of urban life. These elements include, but are not limited to, high-quality jobs, recreation, culture, use of public space, free passage, and civic participation. Perhaps more importantly, downtowns are the places where we should expect to experience the diversity so uniquely appealing to people everywhere.”9

Traditionally, residents with a broad range of education levels, work experience, ethnicities, ages, and incomes have called downtown home. In downtown Austin, 74% of residents are non-Hispanic white, 8% Asian, and 3% black. 13% of residents identify as Hispanic. That figure reflects a key reason downtown lags both the full city (with 35% of residents identifying as Hispanic) and the region (32%) in residential diversity.

Workforce diversity shows similar patterns across downtown, city, and region. This suggests that downtown may offer residents from all backgrounds greater access to economic opportunity. A recent McKinsey study underscores the importance of building on this access. It found companies with more racially and ethnically diverse workforces 35% more likely to perform better than their respective industry medians.10

Downtown’s residential population has grown increasingly wealthy since 2010, with a decline in households earning less than $40,000 annually and a doubling of the number earning more than $75,000. In fact, 55% of households downtown earn more than $100,000 annually. Thus, median household income downtown, $106,000, is 1.5 times higher than the citywide median, $67,000.

Rapid income growth in a neighborhood often signals displacement of lower-income residents, but according to the Brookings Institution’s Metro Monitor-2017 report, the Austin region is one of only four U.S. metro areas that has achieved inclusive economic growth.11 Inclusive growth occurs when all segments of society share in the benefits of economic growth (e.g., improved employment, middle-class wages) and economic outcomes reduce racial disparities. For instance, rising household incomes in Austin can be attributed at least partially to increasing wages for the entire population. Between 2010 and 2015 the Austin-Round Rock MSA saw increases a 5% increase in employment, 8% increase in median wage, and an 8% reduction in relative poverty. Yet, Austin also ranks as one of the most economically segregated cities in the country according to a study by Martin Prosperity Institute.12 Although incomes across all demographics have increased, poorer neighborhoods remain geographically separated from affluent neighborhoods.

Less than $15,000

$15,000-$40,000

$40,000-$75,000

$75,000-$100,000

$100,000 and above

MEDIAN INCOME DOWNTOWNCITYREGION

MIDDLE CLASS* RESIDENTS

*Middle-class households are defined as those with incomes between $40,000 and $100,000 annually. This definition is based on national averages, which may not align fully with local definitions.

Downtown Austin has a highly educated population. 73% of residents over the age of 25 hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. This percentage has increased 5% since 2010, when 68% held a bachelor’s or advanced degree. Interestingly, the share of residents with advanced degrees has risen 10% since 2010 and the share of residents with a high school education or below has decreased 7%.

Downtown has a mix of both rental and owner-occupied housing units, and both types have seen costs rise significantly since 2010. In 2016, about two-thirds of rental units downtown cost $1,500/month or more, and the number of units renting for more than $2,000 per month had jumped 250%. On the owner-occupied side, the median home value downtown in 2016 reached just over $400,000, an increase of $100,000 since 2010.

Despite these increases, compared to other downtowns in this study, the number of rent-burdened households, those spending more than 30% of their income on housing, remained relatively low at 27%. 5% of residents downtown live in poverty, a lower rate than in the city or region. The increases in household income have so far been able to mitigate higher housing costs, but as these values continue to increase, the Downtown Austin Alliance and the City of Austin will have to take a preemptive approach to the issue of affordability and housing. The Downtown Austin Vision, launched in May 2018, encourages the growth of a more diverse population by increasing the quantity and variety of downtown housing options appealing to a wider range of ages and incomes.13

Due to their expansive base of users, center cities can support a variety of unique retail, infrastructural, and institutional uses that offer mutually reinforcing benefits to the region.

Downtowns and center cities typically form the regional epicenter of culture, innovation, community, and commerce. Downtowns flourish due to density, diversity, identity, and use. An engaging downtown “creates the critical mass of activity that supports retail and restaurants, brings people together in social settings, makes streets feel safe, and encourages people to live and work downtown because of the extensive amenities.”14

Benefits of Vibrancy: Creativity, Innovation, Investment, Spending, Fun, Utilization, Brand, Variety, Infrastructure, Celebration

Downtown represents 3% of all retail sales and 11% of retail stores citywide.15 Its 7,000 residents, 92,000 workers, and Austin’s 27 million annual visitors generate $600 million in retail and food and drink sales in the study area. Ten distinct and named corridors across downtown, each with its own character and offerings, host retail, live music, and nightlife attractions. As an example, the food review site The Infatuation describes Rainey Street as “an adorable, neighborhood-y street, with craftsman houses that are actually bars, string-light covered

patios, food trucks, craft cocktails, and a constant stream of both locals and non-locals looking to party.16

More than half of downtown’s 540 storefront businesses are restaurants or bars. Another 11% are destination retail stores, which consist of clothing, shoe, electronic, jewelry, luggage, and leather stores. Retail space costs on average $2 to $17 more per square foot than the citywide average, and storefront vacancy is 6%, indicating strong demand for downtown storefront space. The 6% vacancy rate—high relative to other downtowns—may represent an issue to focus on in the future.

TOTAL RETAIL BUSINESSES

4,878

NUMBER OF RETAIL BUSINESSES PER SQUARE MILE

13,325

3

NUMBER OF RESTAURANTS AND BARS

2,545

4,269

NUMBER OF DESTINATION RETAIL BUSINESSES

1,740

Downtown functions as a regional destination for dining and nightlife. Retail marketplace data show that most storefront sales far exceed local demand for their type of business, signaling a large volume of non-resident spending. For instance, food and beverage sales account for slightly over half of total downtown spending, and an estimated $284 million out of $314 million comes from non-residents. Similarly, destination retail (clothing, jewelry, electronics) brought in about $59 million in sales (10% of total downtown sales), with about $38 million coming from non-residents.

A growing residential population typically marks a vibrant and fast-changing downtown; more residents bring more energy and character to their new home. From 2010 to 2016 the Austin-Round Rock MSA was the fastestgrowing metropolitan area in the United States, with a 19% population increase. Downtown Austin’s population grew by 85% during that time, showing that downtown captured a disproportionate amount of regional and city growth. An analysis of potential renters from Apartment Guide in Austin shows that downtown ranked as the city’s most popular neighborhood.17 Developers responded to this demand by adding residential inventory equivalent to an astonishing 66% of existing stock between 2010 and 2016.

Downtown has a large concentration of residents—34%— aged 25 to 34 years, and relatively few 24 or younger. Compared to citywide figures, this shows how much the 25-to34 age group values downtown living. A Need-To-Know Guide for Moving to Austin suggests downtown’s appeal to this group: “If you’re someone who loves dining, entertainment and elegant condo living, downtown Austin is the place for you. While it comes with a hefty price tag, downtown Austin is the cultural epicenter of it all. You’ll find a vibrant business district, delicious restaurants, artistic communities and tons of apartments and condos to choose from.”18

The University of Texas at Austin sits on the edge of downtown. With a student population of 51,000, UT has a profound impact on the demographics and vibrancy of downtown. Through its large student body, proximity, and attractions like the Ransom Center, the Blanton Museum of Art, and Texas Memorial Stadium, the university brings additional activity and vibrancy to downtown.

(2010 - 2018)

Downtowns and center cities preserve the heritage of a place, provide a common point of physical connection for regional residents, and contribute positively to the brand of the regions they anchor.

Downtowns are “iconic and powerful symbols for a city and often contain the most iconic landmarks, distinctive features, and unique neighborhoods. Given that most downtowns were one of the oldest neighborhoods citywide, they offer rare insights into their city’s past, present, and future.”19 The cultural offerings in downtown enhance its character, heritage, and beauty, and create a unique sense of place not easily replicated in other parts of the city.

Benefits of Identity: Brand, Visitation, Heritage, Tradition, Memory, Celebration, Fun, Utilization, Culture

111,336

PHOTOS POSTED ON INSTAGRAM WITH #DOWNTOWNAUSTIN

333,906

PHOTOS POSTED ON INSTAGRAM WITH #KEEPAUSTINWEIRD

*Instagram downtown hashtag count as of October 2018.

Known as the “Live Music Capital of the World,” Austin has a strong and widely recognized identity. Few cities in the United States have comparable brand reach and recognition. Articles and top-ten lists from publications such as U.S. News, Zagat, Wallet Hub, and Thrillist celebrate Austin’s food, entertainment, and cultural offerings. Downtown epitomizes the staples of the city’s culture, with dozens of live music venues, hundreds of restaurants and bars, more than 100 public art installations, and a rich history as represented in 190 historic structures. In addition, downtown has 24 museums and more than 150 acres of open space between its greenways and parks. Parks and open spaces, including Lady Bird Lake, make up about 20% of downtown’s footprint.20

“Keep Austin Weird,” a catchphrase embedded in the city’s culture, speaks to a powerful sense of place. Beginning as an offhand comment on a radio show, it has ballooned into a local mantra and campaign for supporting local businesses.21 It communicates a deep commitment to preserving what makes the city special. In the book Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas, author Joshua Long describes the conflict between the resident creative class and incoming capital investment, which many see as a threat to Austin’s identity and authenticity. As a key source of local identity and a focal point for capital investment, downtown stands right in the middle of the tug-of-war between preservation and development.

Austin sees 27 million visitors annually and hosts several events with national and international drawing power. First among these, downtown-based South by Southwest (SXSW) Conference & Festivals organizes and hosts tradeshows and festivals to “celebrate the convergence of the interactive, film, and music industries.” Combined attendance for SXSW events totaled nearly 289,000 in 2018, with attendees from 102 countries, and the festival generated $350 million in economic impact in the city.22 Other major events include the Austin City Limits Festival and Austin Trail of Lights, both located next to downtown at Zilker Park. Downtown has more than 10,000 hotel rooms at a healthy occupancy rate of 81%, with another 1,000 on the way.

At its broadest, resilience means a place’s ability to withstand shocks and stresses. Thanks to their diversity and density of resources and services, center cities and their residents can better absorb economic, social, and environmental shocks and stresses than other parts of the city.

Diversity and economic vitality equip downtowns and center cities to adapt more readily to economic and social shocks than more homogenous communities. Similarly, density puts downtowns and center cities into a better position to make the investments needed to hedge against and withstand increasingly frequent environmental shocks and stresses.

Benefits of Resilience: Health, Equity, Sustainability, Accessibility, Mobility, Durability of Services, Density, Affordability, Civic Participation, Opportunity, Scale, Infrastructure

Economic Resilience

As noted in the Economy section, downtown Austin is economically resilient, with strong activity across a range of sectors, including public administration and professional, scientific, and technical services, that enables recovery from or adaptation to negative shocks like a financial crash or the decline of a particular industry. Residents’ educational achievement—an unusually high 73% of those 25 and older— makes them better equipped as individuals to withstand economic shocks.

Social Resilience

Diversity, density, and access to public gathering places and community supports all contribute to making downtowns and center cities socially resilient. Further, research shows that walkable urban places typically have greater diversity, a higher share of low-income people, and lower racial segregation than drivable suburban areas.23 Additional research by the George Washington University Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis found a positive relationship among walkable urbanism, economic performance, and social equity, although the researchers caution that these findings don’t eliminate the need to develop mechanisms and policies to assure affordability.

With 30 parks, 5 libraries, 11 community centers, 12 religious institutions, and more than 10 schools, downtown Austin provides opportunities for residents, employees, students, visitors, and others to meet, learn, and take part in civic life. As stewards of downtown, urban place managers work to make neighborhoods more livable and “create communities that welcome people of all walks of life, offer the services necessary for residents, and create integrated and holistic communities.”24 The availability of parks, outdoor activities, and open space in the center city enhances quality of life by providing opportunities for downtown residents to pursue healthier lifestyles.

Access to community resources is critical for the social resilience of low-income residents. In 2017, the downtown area accounted for 400 people—47% of the total Austin-area count of homeless people. The inclusive economic growth discussed in the Economy section may explain the drop in the poverty rate, but that decrease may also result from displacement of low-income households.

SHARE OF CITY

1%

RENT-BURDENED RESIDENTS 0.5% RESIDENTS IN POVERTY

Efficient buildings and a robust transportation infrastructure enhance both a city’s resilience and its sustainability. Downtown has 63 LEED-certified buildings, more than 100 public transit stops, 27 bike-share stations, and 50 electric-vehicle charging ports. The city has aggressively pursued a sustainability program, such as a new ordinance prohibiting restaurants from disposing of food waste in landfills that took effect in October 2018.25 The new rules redirect food scraps from all restaurants to farms or composting sites. Although not the first city to deploy legislation to fight food waste, Austin has taken the lead among cities in pushing implementation to the restaurant level.

Achieving several of the goals outlined in the Downtown Austin Plan would increase both social and environmental resilience. They include an urban rail project, investment in signature parks, investment in infrastructure, permanent supportive housing, and denser development.26

Compared to Austin citywide, downtown has a significantly higher Walk Score (90 vs. 40), Transit Score (68 vs. 34), and Bike Score (89 vs. 51). Downtown residents depend significantly less on driving to get around then do residents citywide or in the region, with 11% walking to work and 4 % biking. Transit currently has a low mode share, but Capital Metro’s proposed Project Connect lays out a vision for significantly expanding transit connectivity across the region and better supporting regional population and economic growth.

Fast-growing downtown Austin anchors a booming regional economy. The city has been able to deliver inclusive economic growth, raising quality of life for residents at all income levels. Developers continue to build housing to meet significant demand to live in the colorful and thriving downtown neighborhood. People have rallied to preserve Austin’s strong sense of place as unprecedented commercial interest focuses on downtown. Downtown provides a cornucopia of cultural and experiential offerings in its restaurants, bars, museums, music venues, museums, public art, and parks. The City keeps sustainability and resilience top-of-mind, with public officials working to mitigate social issues and implement sustainable practices while developers construct energy- and water-efficient buildings.

Based on the data collected for the Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities study, we identified three tiers of downtowns, defined by stage of development. We divided the 24 downtowns that have participated to date into “established”, “growing” and “emerging” tiers based on average growth in employment, residential density, population growth, job density, and assessed value per square mile. It is important to note that downtown geography and demographics served as the sole basis for the tiers and that a small sample size required a conservative approach to generalizations.

Austin’s downtown falls in the “growing” tier. These tables show how it compares to its peers in the same tier, and to the citywide average for tier cities. For the full set of cities by tier and accompanying data points, please refer to the Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities compendium.*

ARBOR

On average, these downtowns cover 3% of citywide land area and have an assessed value of $7.4 billion or 11% of citywide assessed value. Compared to the tier, Austin accounts for:

*The compendium report is available at the IDA website,

APPENDICES

PROJECT METHODOLOGY

PRINCIPLES AND BENEFITS

DATA SOURCES

ADDITIONAL IDA SOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

In 2017, IDA launched the Value of U.S. Downtowns and Center Cities study. The IDA Research Committee worked with 13 downtown organizations, Stantec’s Urban Places as a project advisor, and HR&A Advisors as an external consultant to develop the valuation methodology and metrics. This year, IDA added another 11 urban place management organizations (UPMOs) and worked with them to collect local data, obtain data from agencies in their cities, and combine these metrics with publicly available statistics on demographics, economy, and housing. Data collected included publicly available census figures (population, demographics, employment, transportation), downtown economic performance, municipal finances, capital projects, GIS data, and the local qualitative context. The downtown partners chosen in both years represent diverse geographic regions and have relatively comparable levels of complexity and relationships to their respective cities and regions.

The project measured the performance of American downtowns using metrics developed collaboratively and organized under five principles that contribute to a vital urban center. Project aims included:

• Benchmarking performance of downtowns using a replicable, scalable framework.

• Creating a baseline for future data collection to build a growing case for the need for both public and private investment in downtowns.

• Developing a common set of metrics to communicate the value of downtowns.

• Expanding the range of arguments that UPMOs can make to stakeholders based on publicly available data.

Despite a relatively small footprint, a downtown has large economic and community impacts, producing multiple benefits for both its city and region. These impacts include higher land values, substantial economic development outputs, return on investment for both public and private sectors, and more efficient use of public infrastructure. These impacts illustrate the critical contribution a downtown makes to a region’s economic development, identity and brand, social equity, culture, vibrancy, and resilience.

Guiding questions for this project included:

• What is the economic case for downtowns? What stands out about land values, taxes, or city investments?

• How do downtowns strengthen their regions?

• Can we standardize metrics to calculate the value of a downtown?

• How can downtowns measure their authentic, cultural and historical heritage?

• How does the diversity of a downtown make it inclusive, inviting, and accessible for all?

• What inherent characteristics of downtown make it an anchor of the city and region?

• Due to its mix of land uses, diversity of jobs, and density, is downtown more socially, economically, and environmentally resilient than the rest of the city and region?

Downtowns have differing strengths: some function as employment anchors, some as tourist hubs, and some as neighborhood centers. Some are all three. We distilled the factors for measuring the value from attributes common to all downtowns regardless of their specific characteristics. These included fun, diversity, density, creativity, size, economic output, mobility, brand, investment, resilience, health, sustainability, affordability, fiscal impact and accessibility.

This project began with a Principles and Metrics Workshop held in 2017 with representatives of UPMOs from the initial 13 pilot downtowns. The workshop focused on developing value principles that collectively capture a downtown’s multiple functions and qualities. Workshop participants worked to refine values that would speak to each principle that helps make downtown a vital piece of the city and regional puzzle. The participants grouped the value principles into five categories. The principles and the benefits that make downtown valuable provided the basis for determining benchmarking metrics.

Downtown advocates tailor their arguments to the interests of different audiences. For instance, within the economy argument, the figure for sales tax revenue generated downtown would have resonance for government officials but likely wouldn’t hold much interest for visitors and workers. For these audiences, a downtown management organization might assemble data showing the types of retail available downtown, whether the offerings meet user needs, and how fully residents, workers, and visitors use these retail establishments. During creation of the data template, the

study team sought arguments that would appeal to multiple audiences and worked to identify metrics that could support multiple value statements. The workshop identified these preliminary value statements:

1. Downtowns are typically the economic engines of their regions due to a density of jobs, suppliers, customers, professional clusters, goods, and services.

2. Downtowns offer convenient access to outlying markets of residents, customers, suppliers, and peers thanks to past and ongoing investment in transportation infrastructure.

3. Downtowns provide a concentration of culture, recreation, and entertainment.

4. Downtowns offer choices for people with different levels of disposable income and lifestyle preferences.

5. Because of their density and diversity, downtowns encourage agglomeration, collaboration, and innovation.

6. Downtowns are central to the brand of the cities and regions they anchor.

7. Downtowns can be more economically and socially resilient than their broader regions.

8. Downtown resources and urban form support healthy lifestyles.

9. Downtowns’ density translates into relatively low percapita rates of natural resource consumption.

10.Relatively high rates of fiscal revenue generation and efficient consumption of public resources mean that downtowns yield a high return on public investment.

These value statements organized and guided development of the full range of metrics for the valuation template. They also helped the workshop participants settle on the five principles the analysis would examine: economy, identity, vibrancy, inclusion, and resilience.

THE 33 SHARED BENEFITS

Each of the principles comprises a variety of sub-benefits. These helped shape the metrics and arguments used in this study.

AFFORDABILITY

CREATIVITY & INNOVATION DENSITY DESTINATION

ECONOMIC IMPACT

ECONOMIC OUTPUT

EMPLOYMENT INVESTMENT

OPPORTUNITY

SIZE AND SCALE SPENDING SUSTAINABILITY

TAX REVENUE & IMPACT

ACCESSIBILITY

AFFORDABILITY CIVIC PARTICIPATION COMMUNITY DENSITY DIVERSITY EMPLOYMENT EQUITY HEALTH

INFRASTRUCTURE MOBILITY OPPORTUNITY SERVICES

SIZE AND SCALE SUSTAINABILITY

ACTIVITY BRAND CELEBRATION CULTURE DESTINATION FUN HERITAGE INFRASTRUCTURE MEMORY TRADITION UTILIZATION VISITATION

ACCESSIBILITY

AFFORDABILITY CIVIC PARTICIPATION COMMUNITY CULTURE DIVERSITY EQUITY HERITAGE MOBILITY OPPORTUNITY SERVICES SUSTAINABILITY TRADITION

ACTIVITY BRAND CELEBRATION COMMUNITY CREATIVITY & INNOVATION DENSITY DESTINATION DIVERSITY FUN INFRASTRUCTURE OPPORTUNITY SPENDING UTILIZATION VARIETY

This section describes the process of selecting metrics, identifying data sources, and developing arguments for the value of downtown. Building on the workshop’s discussion and recommendations, the study team undertook a literature review and extensive analysis of possible additional metrics for evaluating downtowns and center cities. Together, these suggested a set of data points. The study team selected each data point for its ability to articulate the benefit that it provides downtown, and to do so in a robust and replicable method for downtown proponents.

The study team favored data categories that downtown UPMOs already collect or have easy access to:

• Data collected by downtown UPMOs:

o Retailer information

o Employer information

o Development activity

o Pedestrian counts

o Events information

• Publicly available data:

o U.S. Census Bureau

o Bureau of Labor Statistics

o State departments of labor

o HUD State of the Cities Data Systems

o Municipal assessment data

o Municipal land use data

o U.S. Energy Information Administration

o Bureau of Transportation Statistics

o FBI crime data

• Proprietary data:

o Real estate

o Demographics

o Labor

o Economic impacts

Additionally, the team focused on data sources that get updated frequently enough to allow for comparative analysis over time. Other priorities for choosing data sources or determining metrics included the ability to demonstrate downtown value from numerous vantage points. Similarly, different metrics can illustrate similar arguments and can be analyzed in numerous ways to address a single principle or audience. We looked for metrics that could work together to bolster a single argument or make specific points standing alone. In our research, data is most compelling when communicated in relation to another data point and placed in the context of the city or region. Combining these qualities, input from the participants, and best practices seen in other downtown and center-city studies led the team to a final suite of metrics designed to illustrate downtown value.

The primary data source for downtown and citywide residents came from the American Community Survey (ACS) of the U.S. Census. This data provides a point-in-time comparison between a downtown and a city. While some individual UPMOs have access to updated figures for downtown and citywide residential population, this report relied on the ACS to assure consistency across downtowns, and to allow a focus on contextual comparisons.

It’s worth keeping in mind the fact that a minor shift in downtown population may seem unusually large when expressed as a proportion if the base population is small. Larger cities might see slower proportional growth, while still densifying rapidly. As with any data source, ACS data estimates may represent one place more accurately than they do another, over- or underestimating population in comparison to locally collected data.

To meet the goal of providing metrics that allow comparison across jurisdictions, we made sure necessary data was available for every downtown, city, and region. For each metric, the data template required an input—for example, total workers—and the team then performed calculations to determine related metrics like growth rates, geographic density, employment density, shares of cohort (e.g., workers by educational attainment), and downtown’s share of citywide and regional figures.

The team worked to identify a set of replicable, scalable, and accessible metrics for each value statement that could support downtown advocacy to a range of audiences. The assessment tool standardized the choice of baseline metrics, typically already collected by downtown UPMOs, and introduced new metrics that represent an attempt to quantify important but subjective elements such as inclusivity, fun, heritage and memory. To support value statements and identified characteristics, three types of data fully illustrate each argument:

1. Absolute facts provide quantitative context and a feel for the scale of the characteristic being used to make the argument.

For example, under economy, a UPMO might want to make the argument that a thriving financial services sector plays a critical role in the city’s economy. The number of financial services jobs, their related earnings, and taxes paid represent absolute facts that support this argument.

2. Indicators measure an argument at a secondary level by focusing on inputs or outputs and may reflect the subject geography or serve as benchmarks for comparison to peer downtowns or case studies of best practices.

At this level, a UPMO could argue that in addition to their direct economic contribution, financial service jobs in downtown assure stable demand for a range of services and retail offerings at different price points that serve all residents. To make this argument, the downtown management organization might map retail vacancies against concentrations of financial services firms to illustrate the relationship between distance to financial services office nodes and viability of retail.

3. Qualitative assessments inject anecdotal context and color into an argument.

For this level, the downtown management organization could include news reports or an interview with the CEO of a major financial services firm that lays out the value they see in locating downtown.

Together, these different types of information allow IDA and the UPMO to communicate downtown’s unique value to the city.

Beyond relevance for different intended audiences (including journalists), the study team imposed three additional filters on data sources to account for the varying capacities of UPMOs, the need for future replicability, and a strong interest in tracking performance against peer downtowns. Data needed to be:

1. Readily available to most downtown management organizations (and ideally public),

2. Replicable (enabling year-to-year comparisons), and

3. Scalable across jurisdictions, allowing for benchmarking and regional comparisons.

Applying these standards helped us assemble a set of metrics that allow downtowns to participate equally in the analysis regardless of a UPMO’s financial resources or technical ability. IDA provided detailed instructions to participating UPMOs on how to use all the metrics selected. To enable downtown management organizations to use the metrics confidently to promote their downtowns, IDA provided a description of each data source, including frequency and method of collection. We directed the UPMOs to use clear qualifying language to introduce the use of proprietary or “crowdsourced” sources (surveys, Yelp reviews, Instagram posts). We expect most downtowns to rely on similar sources of proprietary data, but participating downtowns may prefer one choice over another (such as CoStar or Xceligent) when obtaining similar data. To the extent possible, data sources should remain consistent across geographic scales (downtown, city, region) and consistent over time for longitudinal analysis.

While the data template and profiles highlight data points for comparison purposes, IDA encouraged each downtown organization to customize its presentation of arguments to highlight the values most relevant to its city and the audiences it wants to reach. For instance, a downtown with a strong transportation system might choose to emphasize transit accessibility in articulating inclusion, while one with little public transportation infrastructure might choose to emphasize the diversity of transit users.

IDA and the pilot downtowns identified five value principles as themes for the project: Economy, Inclusion, Vibrancy, Identity, and Resilience. Though the ways downtowns produce value for their cities and regions differ, broadly applied, these statements convey the overarching value of downtowns. Each value statement is supported by multiple metrics and methods of articulation tailored to different audiences. In creating the data template, we worked to identify arguments that would appeal to multiple audiences, and to use metrics to support multiple value statements.

This study developed a definition of the commercial downtown that moved beyond the boundaries of a development authority or a business improvement district. For one thing, geographic parameters vary across data sources and may not align with a UPMO’s jurisdiction.

Urban place management organizations vary widely in terms of their geographic definition. To make boundaries replicable and comparable across data sources, the study team recommended aligning each downtown with commonly used census boundaries. In most cases this meant using census tracts, the smallest permanent subdivisions that receive annual data updates under the American Community Survey. They make ideal geographic identifiers, since new data is released regularly, and tract boundaries do not change.

Employing census tracts may not accurately reflect the value of every downtown. In some cases, census block groups more accurately captured the downtown boundaries. Though the Census Bureau occasionally subdivide block groups over time, block groups also receive annual data updates and are compatible with most data sources. We looked to the 2012 publication, The Value of Canadian Downtowns, for effective criteria:

1. The downtown boundary had to include the city’s financial core.

2. The downtown study area had to include diverse urban elements and land uses.

3. Where possible, we sought hard boundaries such as major streets, train tracks, or geographic features like rivers.

4. An overarching consideration was that data compiled align with selected downtown study areas.

IDA’s study Downtown Rebirth: Documenting the Live-Work Dynamic in 21st-Century Cities provided further guidelines for defining downtown geography. Recommendations included defining employment nodes at the census tract level; adding census tracts beyond the commercial downtown to define a”greater” downtown, including half-mile and one-mile polygons within the conformal conic projection.

“

” DEFINING DOWNTOWN BOUNDARIES IS A MAJOR CHALLENGE, AS EACH PERSON LIVING IN A CITY HAS A DIFFERENT UNDERSTANDING OF DOWNTOWN BASED ON THEIR PERSONAL EXPERIENCES.

International Downtown Association

After determining each downtown’s boundaries, the study team calculated resident population within the boundaries using census data; calculated employment levels using Total Jobs data for each tract in the selected areas, and calculated live-work statistics using Primary Jobs data by taking the number of workers who live and work in an area and dividing it by the number of all workers living in the area. Primary Jobs differ from Total Jobs by designating the highest-wage job as the “Primary” one if an individual holds more than one job. Using the Census Bureau’s On The Map tool, the study team created maps to show the borders of each area.

Each downtown provided IDA with the geography selection for its downtown, which IDA then worked to refine, given local conditions and UPMO needs. Customized shapefiles or census tracts defined the downtown boundaries. For city and regional boundaries, IDA worked with the downtown management organization to confirm the accuracy of the respective census-designated place or MSA.

IDA collected the selected data points for all downtowns from the recommended sources and then input them into the data template. Completing the data template necessarily involved a wide range of sources. This section covers preferred sources for demographic, market, labor, and real estate data.

Covered in this guide

Recommended sources for demographic, market, labor, and real estate data include:

LEHD On the Map: The data template requires two datasets from LEHD: (1) an “area profile” of workers in the years 2015 and 2010 and (2) an “inflow/outflow” profile that describes how many workers live in the study area and how many live outside it.

An intuitive, easy-to-use mapping and data tool for the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD) dataset.

On the Map pulls and aggregates labor data (e.g. employment, workforce composition, commute flows) from the LEHD based on an inputted geography.

LEHD allows UPMOs to define their geographies in census-compatible terms as well as access labor data.

U.S. Census, American FactFinder: American FactFinder is the U.S. Census Bureau’s publicly available data source. It is a powerful tool for accessing census data. For this study, this source serves as the basis of our demographic and social analysis.

WHAT IS IT?

WHAT DOES IT DO?

HOW ARE WE USING IT?

The U.S. Census Bureau’s free, public data portal.

American FactFinder pulls and aggregates demographic and social data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s decennial census (every ten years) and American Community Survey (every year). Any user can query the American FactFinder for a specific fact or set of facts, a geography, and a time period and receive raw numbers for use in a template.

FactFinder provides the basis of our demographic and social analysis.

ESRI Business Analyst: ESRI Business Analyst is ESRI’s tool for retrieving demographic and market data targeted toward business users.

WHAT IS IT?

WHAT DOES IT DO?

HOW ARE WE USING IT?

ESRI’s proprietary data tool designed for casual and business users.

ESRI Business Analyst allows users to define custom geographies (including drive times) and pull demographic and social indicators as well as proprietary indicators such as retail spending.

UPMOs will use ESRI to pull retail spending and establishment data, as well as demographic data within an average commute time.

Real estate market data: Real estate market data can come from a variety of sources, including real estate data services, which require subscriptions; market reports, available online; and local brokers and economic development agencies, who frequently track real estate information.

WHAT IS IT?

WHAT DOES IT DO?

HOW ARE WE USING IT?

Indicators such as absorption, deliveries, vacancy rates, and average rent.

Real estate data, accessed through real estate data services, market reports, or brokers, allows UPMOs to speak to the built form and economy of their downtowns.

Real estate data, which can come from various sources, is used to make economic and density arguments in the data template.

Municipal data: Collected at the municipal level, this data includes information such as local investment, capital projects, tax assessments, tax revenue, crime and safety statistics, and land uses. Agencies collecting this data typically include the mayor’s office, the tax assessor’s office, planning and zoning, licensing and codes, economic development, and the comptroller’s office. These data can flesh out the story of downtown’s economic and fiscal impact on the city.

Downtown stakeholder data: Data collected from downtown stakeholders at the place management level include bicycle and pedestrian counts, cleanliness and safety statistics, events, major employers, development tracking, residential tracking, surveys, and other insights into the localized place. Downtown management organizations already report many of these statistics in their annual or state of downtown reports.

The data template provided a framework for a three-step process. For this report, IDA first entered static data points from a downtown and data sources for the downtown, city, and region for the current year and a reference year (in this case, 2010). Based on these inputs, the template automatically generated a set of detailed valuation metrics. IDA then linked the outputs to final profiles, using the statistics to construct value statements on the significance of downtowns.

Provide a common set of metrics to communicate the value of downtown.

Expand the range of arguments UPMOs can make to their stakeholders using publicly available data.

Save time and effort by automating portions of analysis.

Enter value for downtown, city, and regionComputed automaticallySelected and refined by downtowns

ï Total land area

ï Number of jobs

ï Jobs per mi² downtown vs. city (dividing jobs by total land area)

ï Growth in jobs over time (comparing 2010 to the current year)

ï Percentage of city jobs (dividing downtown jobs by city jobs)

For each static data point entered, the “outputs” tab of the data template contained calculations that compared and normalized metrics across time and geography, including:

• Change since 2010

• Value per square mile

• Value per acre

• Value per resident

• Value per worker

• Share of cohort

• Share of city

• Share of region (for some data points)

The selected data had to communicate the arguments for downtown while being scalable, compelling, and replicable across jurisdictions. The metrics underpin a framework designed to strengthen the advocacy that the downtown management organizations already undertake by creating arguments relevant not only to downtown allies but to stakeholders not yet convinced.

“As the economic engine of the city, downtown has a density of jobs nearly three times the city average, a rate of job growth twice the city average, and nearly 40 percent of total city jobs.”

The final methodology, informed by experts and downtown leaders, encompasses more than 100 key data points, 33 benefit metrics, and nine distinct audiences. It evaluates the results through the lenses of the five principles of economy, inclusivity, vibrancy, identity, and resilience. The resulting study articulates the value of downtown as a place, highlighting its unique contributions and inherent value for the local city and region.