WEAVING LEGACIES DIANNE SMITH

WEAVING LEGACIES DIANNE SMITH

Weaving as Metaphor

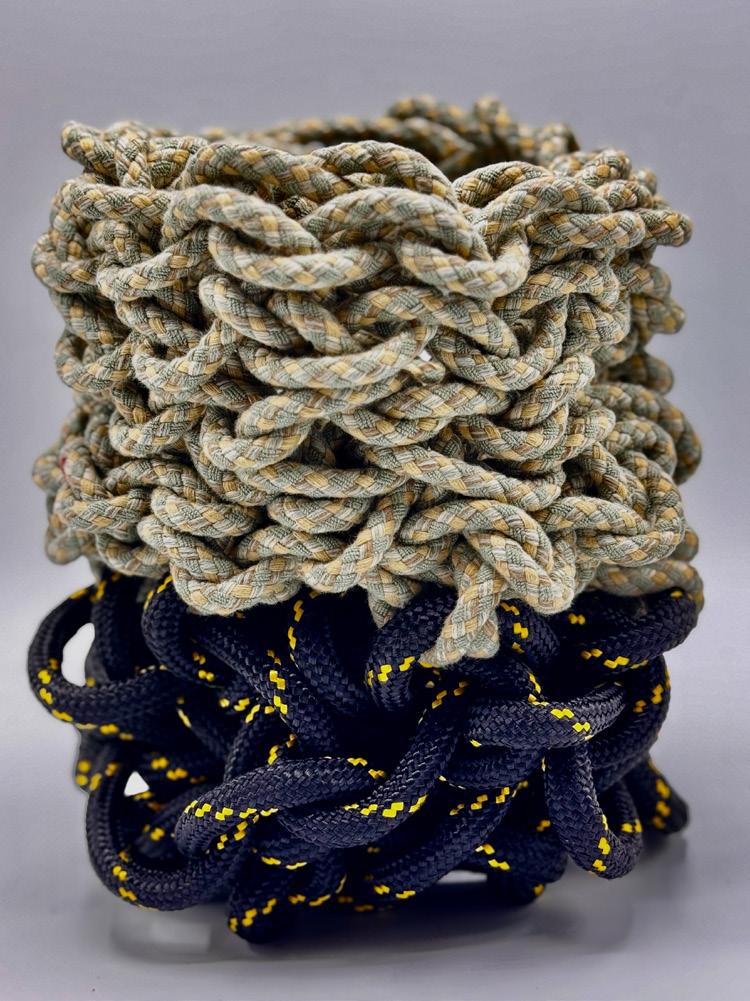

Ropes, wires, textured metal, flat pieces of aluminum, threads, ribbons, exquisite touches of gold and silver, ropes crafted in China, indigenous sisal twists; the materiality in Dianne Smith’s woven pieces weaves the past and the present. A Bronx native deeply rooted in its Hip Hop culture, Smith harnesses her creativity to craft contemporary sculptural pieces that resonate with the rich history of the African Diaspora. In doing so, she fosters a dialogue that transcends geographical boundaries and engages with an ongoing transcontinental narrative.

Inherent in the legacy of the African Diaspora is the ability to weave a complex fabric of identities and Smith does just that: claiming her weaving inheritance from both sides of the Atlantic. Twisted plastic yellow wall pieces and wire sculptures nod to traditions such as Zulu wire baskets, woven commercial ropes echo bold colored Masai beaded baskets while sisal rope twists are reminiscent of indigenous Mayan basket weaving in Belize, a strong tradition to this day. Some works are variations on a theme, part of a series, reminiscent of musical score, they are a beat and ask us to rhyme. They are calligraphy in space, an impulse to both contain and explore. Yet the tightness of some of the wall pieces evoke fingers that move with agility and precision; fingers that are used to weave hair into tight braids and cornrows. Twisted woven metal, ribbons tying onto itself, small hands weaving baskets to make Johnny cakes for breakfast.

While the woven pieces are in a constant exploration of the materials, they firmly inscribe

themselves in a contemporary context. The modernist traditions of Calder or Monk’s iconic Dream come to mind just as much as the work of contemporary Gullah master sweetgrass basket weaver Corey Alston; or native-American master weaver, artist Jeremy Frey. One could state that as the pieces simultaneously leads us to Africa, Belize and the Bronx, they code switch: post-colonial resistance to assimilation, integration and erasure at its best.

The timeless tale of Anansi is quite alive in the African Diaspora. He is the cosmic weaver, symbol of resilience that keeps ties together across bodies of water, across time and space. The current resurgence and recognition of this craft into the contemporary art space perhaps presents itself as a socio-cultural alternative; a profound response to the illusion of separation that permeates our world— a truth understood by many indigenous cultures in the profound interconnectedness that binds all life forms together.

VCC, Harlem, September 2025

IN CONVERSATION: Vladimir Cybil Charlier & Dianne Smith

Vladimir Cybil In Conversation with Dianne In her studio, surrounded by materials in flux, Dianne reflects on the origins of her weaving practice.

On beginnings:

“My first experiments weren’t with traditional weaving at all, dry cleaning hangers became small sculptures, then paper, rope, and cutup clothing followed. I didn’t know formal weaving techniques, but a memory surfaced of my Aunt Louise in Belize showing us how to knot and weave. Even when my mother and aunts couldn’t recall those details, I felt it must be something inherent, passed through the hands. I think of my grandmother kneading bread, scrubbing laundry, braiding hair, the wrist and hand movements themselves became my vocabulary.”

On inherited traditions:

“For me, it’s the ‘familiarity of the unfamiliar.’ I don’t claim specific lineages of African or Mayan weaving, but I trust that knowledge carried through ancestry reveals itself in my gestures. So much is passed down through the hands, whether we consciously name it or not.”

On training and relinquishing outcome:

“My formal training was in draftsmanship and painting. I can draw and use all mediums. But while training focuses on achieving a set result, a portrait that looks like its subject, I work from ambiguity and improvisation. I rarely know what the outcome will be, and I embrace that uncertainty. When people anticipate an installation and say, ‘I can’t wait to see what you do,’ my response is, ‘Me too.’ I create alongside the work, not in control of it.”

On improvisation and hip hop:

“I often use rope, worn fabric, or torn bedsheets instead of traditional materials. That comes from an improvisational ethos, making something from nothing. Growing up in the Bronx in the 1970s, hip hop emerged from precisely those conditions of survival and necessity. Like jazz, it was about finding a voice, making a way out of no way. That same spirit runs through my approach to weaving.”

On community and continuity:

“In my family, weaving was always communal, a task done together. My installations carry that forward; they become collective projects where others participate in tearing and crumpling materials. It’s like a weaving circle. For me, community is about more than economics; it is about family capital, sustaining one another’s well-being. Historically, weaving meant the community ate, survived, and educated itself. The act of weaving holds all of that knowledge of the hand.” Hey Cybil, did I answer the questions?

Dianne Smith as Material for the Arts Artist in Residence at a SoHo community event hosted by the organization, in 2017.

Orí Sorí Ikóré

Ifé Títí

Òrìsà Omi

Ojiji àti

Ìnà Rere

Alákor

Ayé Lòwó

Ojú Ina

Dianne Smith is a multidisciplinary artist with a career spanning more than two decades. She is a recipient of the Nancy Graves Foundation Award, a New York State Council on the Arts grant, the Lunder Institute Fellowship, and a Fulbright from the U.S. Consulate General in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Smith served as Director of Public Engagement at the Allentown Art Museum. Her work is in the collections of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Bronx Museum, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Brodsky Organization, and the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art. She earned her MFA in Creative Practice from the Transart Institute in Berlin, Germany, via Plymouth University, UK.

Instagram: @iamdiannesmithart

Website: www.diannesmithart.com

Vladimir Cybil Charlier is a New York-based Haitian American multi-disciplinary artist whose work has focused on developing a language to articulate a diasporic culture within a contemporary context. The search for that language has been the thread linking her different bodies of work, whether mixed-media paintings, videos, prints, or three-dimensional work. Charlier has attended art residencies at the Skowhegan School, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Fountainhead Studios, and, more recently, Brandywine Workshop and The Haystack Mountain School of Craft. Her work has been included at the Venice Biennial as well as The Cuenca and Panama Biennials, and recent exhibitions include Le Grand Palais in Paris, Relational Undercurrents at MOLA, Caribbean Crossroad at the Perez Museum, Transmutation of Alchemy at Tiger Strikes Astroid, and a solo exhibit at The Garner Arts Center.

EQUITY GALLERY

245 Broome Street, New York, NY 10002 (931) 410-0020

info@nyartistsequity.org

Ghana

Di Strong Ting