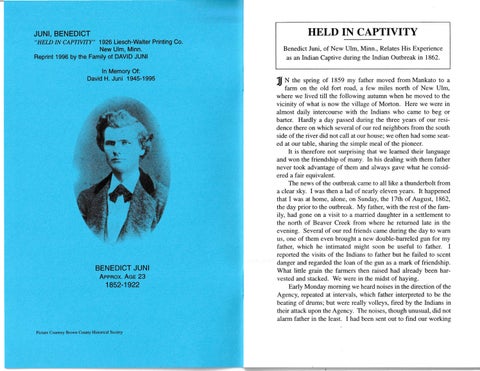

JUNI, BENEDICT

"HELD IN CAPTIVITY" 1926 Liesch-Walter Printing Co.

New Ulm, Minn.

Reprint 1996 by the Family of DAVID JUNI

ln Memory Of: David H. Juni 1945-1995

BENEDICT JUNI

Appnox. AcE 23 1852-1922

JUNI, BENEDICT

"HELD IN CAPTIVITY" 1926 Liesch-Walter Printing Co.

New Ulm, Minn.

Reprint 1996 by the Family of DAVID JUNI

ln Memory Of: David H. Juni 1945-1995

BENEDICT JUNI

Appnox. AcE 23 1852-1922

Benedict Juni, of New Ulm, Minn., Relates His Experience as an Indian Captive during the Indian Outbreak in 1862.

!f N ttre spring of 1859 my father moved fromMankato to a - farm on the old fort road, a few miles north of New Ulm, where we lived till the following autumn when he moved to the vicinity of what is now the village of Morton. Here we were in almost daily intercourse with the Indians who came to beg or barter. Hardly a day passed during the three years of our residence there on which several of our red neighbors from the south side of the river did not call at our house; we often had some seated at our table, sharing the simple meal of the pioneer.

It is therefore not surprising that we learned their language and won the friendship of many. In his dealing with them father never took advantage of them and always gave what he considered a fair equivalent.

The news of the outbreak came to all like a thunderbolt from a clear sky. I was then a lad of nearly eleven years. It happened that I was at home, alone, on Sunday, the 17th of August, 1862, the day prior to the outbreak. My father, with the rest of the family, had gone on a visit to a married daughter in a settlement to the north of Beaver Creek from where he returned late in the evening. Several of our red friends came during the day to warn us, one of them even brought a new double-barreled gun for my father, which he intimated might soon be useful to father. I reported the visits of the Indians to father but he failed to scent danger and regarded the loan of the gun as a mark of friendship. What linle grain the farmers then raised had already been harvested and stacked. We were in the midst of haying.

Early Monday morning we heard noises in the direction of the Agency, repeated at intervals, which father interpreted to be the beating of drums; but were really volleys, fired by the Indians in their attack upon the Agency. The noises, though unusual, did not alarm father in the least. I had been sent out to find our working

oxen which had strayed off during the night. On my return with the oxen the Hayden brothers, our nearest neighbors, hastened to our place with the news that the Indians were plundering and killing the whites. Father was still skeptical, but was soon prevailed upon to prepare for flight to Fort Ridgely, the nearest place of refuge, which was about fifteen miles from our place.

Mrs. Mike Hayden was left in father's charge. Her husband and his brother, John, being armed went to join Mr. Eisenreich and another man whose name I cannot recall. They felt confident they could defy any band of Indians they would be likely to meet. Alas, not one of the number lived to relate any deeds of valor. The hay rack was replaced by the box, the oxen were hitched to the wagon, a few articles of clothing, some bedding and food hastily put on;Mrs. Hayden, my mother and the small children placed on top and all given in charge of Mr. Zimmermann, who had been helping my father during harvest and haying. On the way he called at his house and added his family to the load. He, too, boasted of how he would defend those entrusted to him with gun and sword for he was the proud possessor of both.

If he did not raise his gun nor draw his sword in the defense of his charge it was not for want of courage, but for lack of oppornrnity. He and his two sons died at their post of duty. The Indians were not out to distinguish themselves for acts of bravery on that day, but to kill as many of the unsuspecting pale faces as they could and they generally succeeded in this before their victims were aware of their presence.

I was sent out by father to round up our cattle, of which we had nearly thirty head and drive them in the direction of the fort. On the way father with my brother, Christian, and elder sister, overtook me, relieved me of the cattle and sent me back to alarm some people who lived at the foot of the bluffs some distance from the road. I reached two families who had already taken alarm and were preparing to flee. They implored me to go with them saying that they would strike for the unsettled prairie and thus avoid meeting Indians, which proved a wise precaution as the party reached the fort in safety. I remained obdurate to their entreaty, mostly because I failed to realize the dangeq and started back in my path of duty. Just as I reached the spot where now the depot is at Morton, I saw three Indians emerging from the nuurow pass between the rock, through which the only then passable road lay; I turned to the left in order, if possible to circumvent the mass of rock, but I feared I should make

slow progress over the somewhat swampy ground. I had turned but a few rods out of the road when the three Indians simultaneously leveled their guns at me. Prudence prompted me to halt, for I had often admired their skill, in bringing down a duck when on the wing, and reasoned that they might with equal facility pick a boy from a horse, thought on the run.

The Indians were about i50 yards from me. One of the three, whom I well knew, and who was noted for his sullen silence, came towards me and asked me whether I intended to offer any resistance. I made no reply. He then took the horse by the bridle and led it towards the road. It occured to me that perhaps he was more anxious to secure the horse than the boy and only regarded me as an encumbrance.

Acting upon the thought I jumped off, the Indian leaped to the place I had vacated without deigning me worthy of another glance, nor did his companions pay any further attention to my movements. The three Indians knowing me and my people were well ashamed to do me bodily harm and would perhaps have taken me with them had I not chosen to continue on my route. Having met such an obstacle in the road I now decided to give it a wide berth wherever practicable. I kept to the north of it and circumvented the high rocks as I had intended to do on horseback. Up to this time I had experienced no fear and even after meeting with the three Indians I took no pains to hide myself from view, but just before reaching the road again I saw the dead body of the ferry man lying in the grass. His little dog was sitting by it and licking the blood that was oozing out of the wounds about his face. The dumb creature wagging his tail turned his eyes upon me beseechingly as if he expected me to help his master. I turned away with a shudder and was now fully convinced that the Indians really meant harm to the whites. Hereafter I proceeded with more caution The road approached the bluffs so I was forced to cross over to the south side of it. I sped on as long as there were no Indians in sight, but as soon as the Indians appeared I lay in the grass till they had passed. Once or twice their dogs came where I was lying and sniffed at me and I expected they would betray me to their masters by barking, but they seemed to treat me with as much contempt as the three warriors at Morton.

I was now about five miles from home and was approaching Faribault's house, which stood- against the bluff where a large creek enters the valley. Here I ventured into the road, but only to dart back into the cornfield in front of the house. Near the house stood a group of Indians

cnS,lrg,od itt utt itnitttittc,cl tliscussiort. I littcr lcirrttr-:tl wlutt tltr: llolrt'ol torrtention was. Here our lcam with thc lirgitivcs had beorr stoppcd, lhc rrrcn in charge killed the women and children, with the exception of Mrs. Hayden, who had jumped from the wagon with her babe in her arm and managed to escape, were hustled into the house and there kept prisoners till their fate should be decided.

In the house were my mother, my younger sisters, Mary Ann and Lizzie and my brother, Fred, a babe of about three months, Mrs. Zimmermann, her daughters, Mary and Lizzy, and her son, Charles. Mr. Zimmermann and his sons, John and Gottfried had fallen but a few rods from the house. Fortunately they were ignorant of the fate that had befallen Mrs. Humphery and her daughter but half a mile further on, or their distress would have been greater. Dr. Philander Humphery in his flight from the Agency had sought refuge in the house of John Magner because his wife was sick and exhausted.

He sent his son, a lad of twelve, to a nearby spring for water to assuage the feverish thirst of his wife. While he was waiting at the door for the return of his son was shot and the house set on fire. The charred remains of the three were later found in the ruins. The boy escaped, met Captain Marsh and his men in their fateful march to the ferry and strange to say came through that fiery ordeal without a scratch.

What about the prisoners in Faribault's house? you ask. The counsel of the more friendly disposed Indians finally prevailed and the party was allowed to proceed on their way to the fort, which they reached after much delay. I must now go back in my narrative to where I left my father, a brother and sister, driving the cattle. They had not gone far beyond Morton when they met a party of Indians who were trying to catch some horses belonging to the settlers. My father being asked to assist complied with the request. The Indians thereupon urged him to abandon his herd and leave the traveled road and seek safety on the prairie. He reluctantly followed their advice. The Indians after having shaken hands with him departed. After a long and weary tramp over prairie and through sloughs father and the two children, whose feet were now bleeding, reached the fort.

When he learned that the rest of his family were not there he wanted to return to search for them, but was not allowed to do so, as every man was sorely needed for the defense of the fort. An hour or more later his anxiety was partly relieved as his wife with three children were brought

irr, brrt l, wlro irccortling to the llrogranr should havo put in my appcarance with thcrn, was not thcrc and they concluded that I had been killed. Alter seeing Indians at the house of Faribault, I crossed the creek at some distance below the ford and then again turned into the road which here ascends the bluffs. I had gone about half way up when I was suddenly confronted with two young warriors who were coming down the hill. The younger of the two drew his bow and was about to pierce me with an arrow when the other pushed his bow aside with the butt of his gun. He asked whither I was going. I replied that I was going Tee-peetonka, "the house big," meaning the fort. He gave me to understand that such could not be and ordered me to face about and keep close in front of him where he could have his eyes on me. The one with the bow could not refrain from torturing me in some way. He had picked up a big blacksnake whip by the roadside and would at intervals give me a lash across my bare legs that made me jump. This was perhaps done with the object of accelerating my speed, for I think that they had been out reconnoitering in the direction of the fort and had ascertained that Capt. Marsh and his men were on their way to the Agency.

On approaching the ford I saw John Zimmerrnann, a young man of about twenty-one lying in such a position that I believed he was taking a nap in the shade. I tried to arouse him, at which the Indians smiled, but soon found that he was sleeping a sleep from which there is no waking. I had always been much attached to John and it was hard for me to meet him thus. His brother lay in the creek a little below the ford and their father in the road on the side of the creek nearest the house. My captors seemed to see some signs of life in him, turned him over and crushed his skull with the butt of the gun. Here our household goods, such as had been hastily loaded in the morning, lay scattered. It occurred to me that in my captivity I might not know how to pass the time, I therefore picked up our family bible which I knew would afford me material for thought and reflection. Much to my surprise I was ordered to drop it. It seems they did not wish to have my march impeded by luggage.

I was hurried along till we approached the ferry. Here I saw Mrs. Eisenreich with her five children, some of them bleeding from tomahawk wounds, coming through the tall grass, followed by a half-breed on horseback, who urged them on with the cuts of a long whip. I now think that this half-breed was Henry Milford, who was hung with the Indians at Mankato. A halt had to be made here to transfer the teams and people to

the other side of the Minnesota river. Mrs. Eisenreich and her children were suffering from thirst, but did not dare to stir to get near the water. She begged me to fetch her some which I did. As there was no other vessel on hand I took the pail from the ferry, which was used for watering horses and oxen, but we all drank with relish the warm river water. On seeing an Indian whom I knew, approaching with horse and buggy, I called his attention to the woman and her children and he took them from their tormentor and made room for them in his buggy, took them to his lodge and cared for them during the remainder of their captivity.

According to the last accounts she is still living in the vicinity of Morton.

Horses and cattle have manifested more or less repugnance to the proximity of the red man. A number of teams, mostly ox teams, had now accumulated at the ferry and their pony drivers experienced considerable difficulty in getting them to venture on to the ferry. I stepped up to the foremost pair and spoke to them in the language of the pale face. The result so pleased the Indians that my reputation as a driver was made not only for that day but for future occasions as you will later learn. I had to take all the teams across and was rewarded by many wash-to-do and grunt of satisfaction.

After having crossed the river my captor. who also assumed the role of my protector, waited sometime before proceeding to the agency, which was situated on the brow of the southern bluff. The young lndians, mostly armed with new shot guns, some double-barreled and some single-barreled, among the latter a few flintlocks, flocked to the ferry with full powder homs and shot bags filled with freshly cast balls, hardly cold from the mould. I later, upon my arrival at the village, witnessed the work of converting the shot into balls by the squaws. For targets new tin pans, of which several stacks had been brought down from the stores, were used. T'he pans were thrown into the river and allowed to float down stream some distance; each marksman watching his own pan, then firing at it. If hit, the pan would spin around and then sink out of sight. This was not done for pastime, but to learr the range and bearing of their new weapons.

A half hour later this practice was to be repeated and heads of soldiers were to be bobbing out of the water for targets instead of tin pans.

Considering the class of firearms used by the Indians, their marksmanship was excellent. Even before I ascended the hill the Indians were deploying along both banks of the river, seeking positions of vantage for the coming fray with Captain Marsh's men. When I entered the Agency

several buildings were burning. The looting of the stores and warehouses was still in progress. In one place I saw a white man carried out of a house on a mattress, whether dead or wounded I could not ascertain.

Several Indians must have come across with some minne waukan, "fire water," and imbibed too freely thereof, for they were raving like demons. One of them brandishing a large butcher knife came towards me and as he espied me he made a savage lunge at me, but my captor dexterously warded off the blow with his blanket. The impetuosity of the onslaught carried him well past us and I was hustled out of the way of the would-be assassin.

Just before leaving the Agency I saw our oxen and wagon driven in the same direction we were headed. I exclaimed delighted, "There is our team!" My captor smiled at my remark and said good naturedly, Well if that is your team we will have a ride. He hailed the Indian who stopped and took us along. I was installed as driver and the oxen seemed as much pleased in obeying the commands as their young master in issuing them'

The first week I had but few tasks to perform and would sit for hours on the bluff and look across the valley at our house, and at that of Mr. Eisenreich, imagining all sorts of impossibilities. Though my cool, common sense taught me better I generally imagined that they were inhabited as before. There I was sitting with only a stretch of two miles intervening and no one to hinder me from going where I pleased, for I was never guarded and could roam about at will. Why not go over and verify my fond longings? I would certainly have acted on such an impulse had it not been for the cloudy waters of the Minnesota that lay between. I had but a few months before, when the river was full from bank to bank, attempted to swim across and would have been drowned had it not been for the presence of mind of a girl who was near the scene and directed by rescue. You no longer wonder that I dreaded to tempt fate a second time. I have been asked, "why did not more prisoners try to escape if they were so free to move about!" The uncertainty of how far we would have to travel and into what hands we might chance to fall on our way, made us rather bear the ills we had than to fly to others we knew not of'

A day or two after my capture several had come to assist my hostess in sewing. They eyed me frequently and I soon found out that a regulation Indian suit was being made for me. It consisted of a belt, a breech or loin cloth, a shirt, a pair of leggings and a pair of moccasins' I was not allowed to wear any kind of headgear as the Indians were not in the habit

of wearing any in camp. I was ordered to discard my clothes of which there were but two articles, a hickory shirt and a pair of trousers - I had lost my hat early in the morning of that eventful day - and put on the new. Of course I was in need of instruction as to the proper use and adjustment of some of the parts of the outfit. I made a neat bundle of the old clothes and was about to stow them away in the tee-pee when I was commanded to throw them into a nearby ravine.

Soon after my arrival at the village I was asked as to my name. When I gave them the name Benedict my interlocutors were simply disgusted. They had never heard of such a name and had no use for it. They were suspicious that I was joking with them. If it had been either Joe or John it would have stuck to me, but as it was, I must of needs be rechristened and received the name of Ta-han-sha. Nor was it long before I was the indignant possessor of a nickname.

At that age my hair was a silvery white and sorely in need of the shears. As I wandered about the camp the Indian youth of my age would have paid no more attention to me than to one of their own number, but my white tow head touched their vein of ridicule. I was greeted from all sides "Pa-ska!" "Pa-ska!", meaning "Head-white" as the Indians put it, for they invariably have the adjective follow the noun.

Camp was shifted a few times during the first ten days without however getting far away from the original site. I think it was more for drill than any other purpose. During the battle of Birch Coulie there was great excitement in the camp. We at times could plainly hear the roar of battle. Towards evening of the first day the squaw told me that she feared I was not safe in camp. She took me to the timber along the bluff. When she espied a hollow basswood tree she ordered me to get into that and stay there all night. A little before dark a heavy shower, though of but short duration, fell in that region. The top of the tree had been broken off and the rain came down the hollow trunk and I was soon wet and numb. Then, too, fear such as children are often possessed ofwhen darkness sets in, began to seize me and I sneaked back to camp and hid in the tee-pee like a guilty cur. It was not slight surprise to my hostess the next morning to see me crawl out from under a robe.

The Indian, who had appropriated our team, remembering how easily I managed the oxen soon came to get me to do some hauling for him. I did this two or three times, but one day on returning from such an errand, my hostess, who had always been stern to me, though she would

not have me suffer in any way, told me that if I worked for other people I could also board there. This started the tears. I had begun to regard this as my home and though not greatly attached to her, I loathed to part with her daughters, whom I looked up to as elder sisters. When the Indian came again with the same request, I told him how matters stood. So much the better, he said, you shall live with me hereafter, and I went along though with a sad heart. Though parted the two maidens did not forget their white brother, Ma-sunka-ska, as they called me. After a lapse of weeks, when their camp was miles away from ours, they came to visit me and asked me to go with them to return the visit. I asked for permission and was granted a leave of absence of one day, from one afternoon to the next. It is needless to say that I was royally entertained. Kind reader, you will not take it amiss when I confess that tears start to my eyes when my memory reverts to these maidens. Think of Christ's words: "I was in prison and ye visited me not," did not they and others of their race exemplify more practical Christianity than many of our so-called Christians of the white race? War always brings cruelties in its train. Upbraid me not if I cannot refrain from making one plea for this so much accursed race. Consider the enlightenment they had and put yourself in their place. You who follow this narrative closely will notice that the red man has similar aspirations and views of life to ours and is susceptible in a degree to kind emotions and capable of noble deeds. There are writers who have exhausted their vocabulary in search of vile epithets to hurl against him. Their writings fairly teem with expressions like "Red devil," and "Bloodthirsty hound." I care not what warranty there may be for the use of such terms; it ill comports, with our much vaunted civilization. If perchance you, gentle reader, have learned by the perusal of these lines to judge him less severely I shall consider one object of my feeble effort as achieved.

Allow me to introduce you now to the new household of which I formed a part for nearly the remainder of my seven weeks captivity. It consisted of two brothers in their best years, each having a wife. The elder who now claimed me had three children, a son of my age by the name of Chaska, a daughter by the name of Winona and a son of about three whose name I cannot recall, if, in fact, he then had one.

The two brothers lived in peace with themselves and wives, under one roof, till some weeks later. I here had regular duties assigned to me. It devolved upon me to furnish all the water and fuel needed in the

preparation of meals and other household purposes, to provide the horses and the oxen with forage and water, to replenish the tobacco pouch of my lord and master with a mixture of kinikinick and plug if no kinikinick was to be found I took inside bark of white ash. Having attended to these duties I was at liberty to amuse myself as I chose. At first I was still annoyed by the calling of the nickname and complained about it to the squaw. She immediately took me under treatment saying that she would effectually stop that source of annoyance. She streaked and dotted my face on a brown background with various bright colors and powdered my hair red as was the vogue with the braves. She repeated this operation every morning, after she had given me a rubbing off with a moist dish rag, unless we happened to be on forced marches. I must admit that I no longer found any cause to complain on that score. Chaska on becoming acquainted with me assumed the role of protector and I was never molested while in his company. We would frequently make excursions to the river bottom on our ponies - I had a colt of hardly more than a year assigned to me. There we would search for plums and grapes of which we generally found an abundance. Before starting on such a trip Chaska would take a brick of maple sugar cut it in two with his tomahawk and give me half which we stowed away in our shirts until we could eat it along with wild fruit. At the tee-pee there was generally a bag of crackers mixed with lump sugar, or a box of raisins or figs opened for us to help ourselves for lunch. The regular meals were good and liberal rations allotted to each. My supper invariably consisted of two cakes fried in lard, each nearly as large as a pie, about a quart of strong black coffee which I could sweeten to taste. At first the squaw added the sugar when she poured out the coffee but I grumbled that it was too sweet and that my food was not salted. She said, "Well if I can't suit you, there is a bag of sugar and another with salt, help yourself?" For dinner we had fresh pork, mutton or beef stewed along with potatoes or green corn. Breakfast varied more than dinner and sometimes was the same as the supper. On the march, we would eat crackers, pemmican and jerked beef. I had never lived so well as far as food was concerned and though I had lost some flesh while at Camp Release and on the trip down, about the first remark that I would hear after the usual greeting was, "How fat you have grown!" or "What's the matter with your nose?" In the first place that prominent land mark in my physiognomy had been sun burnt and then often hit by stones thrown at me by Indian boys when I ventured out alone or went to

fetch water. It sometimes happened that there was a veritable hail of stones. I had to pass through and the bottom of the pail would be covered with them when I got to the tee-pee. Of course these conditions did not prevail and were only exceptional, but recent and aggravated enough to have left me disfigured when I reached my people.

During the first weeks of my captivity I met none of my fellow prisoners and was not aware that there were any except Mrs. Eisenreich, her children and myself. I had met only one person who could speak any language other than Sioux and that was Mr. Robinson, a neighbor of ours, who had an Indian woman for a wife. He could give me no information as to the fate of my people but nevertheless I was glad to meet him. There was another occasion on which there was great excitement in camp. The Indian happened to be at home and feared for my safety. He rolled me up in a buffalo robe and sat on me and calmly smoked his pipe when a few furious Indians rushed into the tee-pee demanding the white boy. They were advised to find him before scalping him. When the storm of fury had calmed I was released from my uncomfortable position.

Here let me tell you something of their sources of supply especially that of meat. There was an abundance of cattle, sheep and hogs in the country all of which the Indians appropriated to their use and held in common. The hogs were killed and eaten first because they were the hardest to herd or to be fed. Then came the sheep of which there must have been a thousand or more. The cattle were kept to the last and driven along from camp to camp as long as the forage lasted or the Indians were not too closely pressed by the soldiers. Usually in the forenoon if the camp was not on the march some young Indians would go out to the herd, shoot three or four head, the squaws were on hand with knives to loosen the hide from the part desired and carry it off. If there was any part that was not wanted it would be left on the hide. These hides along the outskirts of the camp were later picked up by teamsters that had hauled provisions for Sibley's army. Then there were patches of potatoes and corn that had been planted by some of the farmer Indians. There was also quite a supply of dried buffalo meat or pemmican among the Indians. The Indians dried much of their beef and buried it along with corn in large circular pits in the dry prairies. Other articles, even wagons, were hidden in that way, Sibley's mules later benefited by some of these stores.

When we started on the first long march the camp was aroused at about midnight. I had hardly got through rubbing the sleep out of my

eyes before the command was given to break tents and load. This was all done in a wonderfully short time and without confusion. The train was soon on the move. We kept on the rest of the night and all next day, passing Redwood, then Yellow Medicine, and did not halt till we reached Hazelwood, some miles above Yellow Medicine excepting a few minutes rest for the animals and for lunch.

On this trip I for the first time saw many of the other prisoners. Among others Mrs. Inefeld who asked me whether I knew what had become of my married sister Mary I told her that I was totally ignorant as to the fate of my family excepting father whom the Indians told me had been killed and which I believed until I was told by some of Sibley's men that he was still among the living. Mrs. Inefeld was the sister of my sister's husband and had lived in the same neighborhood. The neighbors to the number of about thirty had gathered at the house of Michael Zitzlaff , my sister's husband, but were soon surrounded by many Indians and slaughtered with the exception of Mrs. Inefeld and her babe a few weeks old and her sister, Mary. The two were offered the alternative of captivity or death. My sister calmly chose the latter while Mrs. Inefield was led away and she was shot. Mrs. Inefeld's experiences in her captivity are far from pleasant. She was to do sewing for the squaws. It was soon noticed that the babe was a hindrance to her work and the squaws tried to separate mother and child but found it difficult to carry out.

They then hit upon a plan of starving the child by reducing the rations of the mother to a minimum. August Gluth, now a prosperous farmer in the town of Eden came to the rescue. He shared his rations with the mother. When this was discovered his too were cut down so that he could not spare any of his. He was determined however to help the woman in her straits. He went about the camp and begged food or picked up some as the case might be, hid it in his clothing and gave it to the woman. They thus managed to keep the child alive. Mrs. Inefeld and August Gluth were both released at Camp Release. My master and his brother brought home a team of horses and a wagon loaded with pork and flour from a raid towards Hutchinson. On this raid they captured an American lady whose infant child they killed. I think that her husband was an officer in Sibley's Army but cannot recall his name. You can imagine how pleased this woman was when she found that she was not the only white captive and she was in a family where there was a companion in misery, she said, "Oh, how glad I am that there is some one with whom I can exchange a

few words." She pulled out of her dress pocket a few doughnuts, such as the warriors were supplied with when out for battle and said: "Just think they expected me to eat this stuff but I can't although I have not had a bite for two days." I smiled and said she would yet learn to eat such stuff with relish. She asked me if I could furnish her some food which the Indians had not touched. I baked some potatoes in the hot ashes of the fire place and she ate them with evident delight. It was not long before she partook of food that was served to the others.

The pleasure of meeting was mutual. We had frequent talks together as to our probable fate. But we were not to enjoy each other's company long. About a week after her arrival these two brothers fell out. I did not ascertain the cause of the quarrel. The younger took the fair captive and his squaw and found other quarters and my master retained the team and the loaded wagon. The addition of the team to the household of course added to my labors. It was at times difficult for me to find plenty of feed on the dry prairies for both the horses and oxen. The horses must have been hungry at times for they began to devour the salt pork and flour that was within their reach. Although I had no quarrels with my master's brother yet he could not forbear wreaking his vengeance upon me.

One day after a heavy shower in which I had been caught I divested myself of all clothing excepting my belt and breech cloth and hung it up to dry. I was sent on an errand to a distant part of the camp on my pony thus scantily attired. It happened that I passed the lodge of this Indian, he and a few companions were standing around the open fire. He noticed me, picked up a buming ember of a yard in length and hurled it at me, striking me across my thighs at the same time hitting the pony. I lost no time in getting away from the place and reporting this spiteful act to my master, who appeared highly displeased with his brother.

Here among the Indians I for the first time saw three of the white man's inventions, playing cards, paper money, and an album with tin-type pictures. These things were given to the children with which to amuse themselves. I might easily have appropriated some of the money. The red man then looked with disfavor upon paper money and I doubt that he valued it at all. It sometimes happened that I alone was left in charge of the tee-pee. At such time there came a girl of about my age to keep me company. Whether she was bidden to come or whether she came of her own accord I do not know but I well remember the shy little brown maiden. She brought the album along to show me. We would sit for hours and

silently gaze at the pictures therein although the faces were all strange to both of us. Then I would dig down to the bottom of my uncle's trunk which my master had left on our wagon and get her the few copies of Harper's Weekly.

The illustrations were then mostly war scenes. There was hardly a word spoken but we were company to each other all the same. She would leave as suddenly and quietly as she had come. On her next call the same programme would be enacted with perhaps the only variation that I would show the periodicals first. In my day dreams I have often seen the mysterious little visitor sitting by ,ry side. It is but natural that she should be of more than trivial interest to me and that I often long to meet the friends of those days when friends were few but thoroughly appreciated.

The bringing up of children, it seemed to me, caused the Indian parents but little trouble. They grew up as contented and happy as kittens or puppies. There was no crying of the babes, and when older no scolding or inflicting of punishment. Of course a child sometimes made a mistake but a look of disapproval was sufficient to deter it from repeating the same. Morally the adults stood on a higher plane than the average white person. I have not yet heard of a single case where a female captive has had cause to complain on that score. Although I have had relatives among them and would indirectly if not directly have become acquainted with such cases.

I was looked upon as quite a prodigy because I could read, and they also believed that I was able to write though as a matter of fact I was not proficient in the latter art at that time. When visitors came as they sometimes did, it was quite natural that I should sometimes be the subject of their conversation. They would tell me that my mother had written a letter in which she requested my return. I was asked whether I was willing to go home again and similar talk would be carried on. When they touched the domain of religion, philosophy or astronomy as they seemed inclined to do my vocabulary failed me as I knew but two words pertaining to those subjects.

Some of these visitors would ask me to call on them the following day and dine with them. It also happened that after I had finished my meal at the tee-pee I would stroll through the camp and as I passed some tent in which the occupants were still eating I was invited to partake of some food with them. On one of these occasions I experienced the pleasure of eating with knife and fork from porcelain plates, as is the custom among the whites.

At Hazelwood there were three buildings still intact when we first formed camp there, a residence, a work shop and a two-story building serving both as chapel and school house. It was the best equipped school house I had seen so far. The boys first ransacked the desks, scattered the books and other utensils and rang the large bell that hung in the belfry. When they tired of this window panes afforded targets for stones and arrows. Next the work shop was visited and some of the rod iron formed into spears and these hurled at fence posts. The day's program was concluded by a monstrous bonfire in the evening. The white frame dwelling of Mr. Riggs and the Williamsons fell prey to the flames. Bear in mind this was not done by adults but by boys not yet in their teens and elicited no applause from their parents. I well remember the sad look and the depreciating shake of the head when I told my master of the day's work. There were four or five white boys of about my age that now frequently met. Louis Kitzmann, now conductor on the C. & N.W, was the eldest and acted as our leader. If the odds were not too much against us we would accept challenges from parties of Indian boys in which the latter were generally worsted. The applause from the Indians would be unstinted as if their own sons were the victors.

There were several reasons why the Indians should form more than one camp. The supply of wood and water was not adequate for a large camp, the site chosen, while admirably adapted for a small camp, was not extensive enough, for the formation of a large one; there were factions among the Indians and it was deemed best to keep these apart. My master belonged to the war party, and that party kept its camp from five to ten miles in advance of the party that was disposed to be friendly to the whites and treat with them.

About the sixth week our camp was shifted from Hazelwood to a place a few miles beyond Lac qui Parle, a lake, formed by the widening of the Minnesota river. The name is the French translation of the Indian name, meaning "Lake which speaks." The north shore in early years was densely wooded and the wall of foliage reflected sounds emanating from the other shore, hence the name. Indians having no term for echo could therefore not call it Echo Lake. With them all names, whether of persons or places, have a significance and are more appropriately applied than among us.

If any communication, such as results of engagements or raids, request or order was to be made public it would be done by means of a

camp crier who passed slowly through camp either on foot or on horseback. Apparently these announcements aroused little interest as the braves remained seated in their tee-pees calmly smoking their kinikinick. Nevertheless it was a far more effective way of advertising than our way of distributing bills or posters. Short grunts informed the crier that he commanded the attention of those within the reach of his voice.

Before going too far in my narrative let me again touch upon the language of the Sioux of Dakotas as they styled themselves. Their system of numeration is more perfectly decimal than ours. Our terms eleven and twelve are an inheritance from the duodecimal system. There is no such anomaly in the red man's system. He expresses twelve thus: wix-jim-inuy sam ta nu-pa, ten plus two; twenty-five, wix-jim-in-ny nu-pa sam-ta sap-ta, two tens plus five; three hundred thirty-four soldiers, sag-er-daso-bach-a yem-men-ny wix-jim-in-ny yem-men-ny sam-ta to-pa, soldiers hundred three (meaning three hundred) tens three plus four. If I had not forgotten the term "eight" I could give you all the numbers up to 999. But let me not tax your patience with a philological discourse, till forbearance ceases to be a virtue.

It was the custom with the Sioux that the head of the family on lighr ing his pipe would pass it around to each one present whether member of family or visitor. Each would take a few puffs and then hand the pipe to the next one till it got back to the head who would then smoke till the charge was exhausted. To refuse the pipe was considered a serious breach of etiquette. Only infants were excused from participating in this social function. I had tact enough not to give offense by declining. The Indians on taking a draught would close their lips and expel the smoke through the nostrils.

Before departing for a battle the warriors all painted and fully equipped mounted their ponies and about six or eight abreast formed in a column and proceeded through the principal streets of the camp at the same time singing a solemn chant. Their guns they held in a vertical position in front of them, the butts resting on the pommel of the saddles or on the ponies' back. At intervals the guns were discharged. I could hear the bullets sing as they returned from their skyward journey. After having made the rounds of the camp several times they broke into a wild gallop with a terrific yell and were soon lost to sight. On some of these occasions the camp was well nigh deserted as far as able bodied men and youths were concerned.

When preparations were going on for the battle of Wood Lake I was led to believe that I would be allowed to go along. Had I not a pony and a flintlock? Before long a warrior turned up who lacked a mount and to him my pony went. Then another came who was short of a weapon and mine went to him. I had sincerely believed that I would at least be permitted to look on. As a good Indian it was my duty, if I took an active part, to fight on the side of the Indians. However I had not fully settled that question in my mind and fortunately was not present when the battle waged and no one accused me of treason to my country. There being no men in camp I was detailed to guard the tent where powder and lead was stored on the night preceding the battle.

The plan was well worked out and if it had not miscarried as the best plans sometimes will, the result would have been more disastrous to the soldiers than to the Indians. News of the defeat reached camp before noon the next day and in a remarkably short time the camp was struck and the squaws on the move for a new site further on towards the border of the state. Tee-pees had again been pitched when the crestfallen warriors returned.

My master told me to get up early for I was to be sent to my mother. "We will be driven to the northwest, our cattle we shall be obliged to leave behind, winter is coming on and you will suffer from hunger and cold," he said. Though he was not in a joking mood, I did not attach any significance to his remarks. The next morning after my chores were done and I had finished my breakfast he ordered me to put on white man's clothes. My mistress had provided for such an emergency. She had somewhere gotten hold of a pair of men's trousers and had cut off about one foot from each shaft. All I retained of my former suit was the calico shirt. I slipped into the trousers which, as you will readily believe, were far from being a perfect fit. My master had a high sense of propriety and would not send me off hatless and coatless. So he skirmished about until he found a gray linen duster that reached to my feet and a silk stove pipe hat that rested on my ears. Thus ludicrously attired I was to depart. I had lost my sense of humor or my appearance would have provoked a fit of laughter in me - Indians rarely laugh.

I did not evince joy at my prospective deliverance. On the contrary when I realized that this was not a mere masquerade and that my master had been in earnest when he told me that I was to go home lumps rose to my throat. When I emerged from the tee-pee a horse was in readiness.

"Mount" my master said. At this tears rushed to my eyes. My master swung himself on and then grabbed me and seated me behind the saddle and galloped off. It was rather an abrupt way of parting but no doubt the best as it saved me the pain of parting with the children who were still asleep. I had become attached to both of them and to my master. I had despaired of ever getting back to civilization and was contented with my condition. Why should I therefore, be anxious to leave? My master rode at a rapid pace for several hours when I beheld on a knoll the stars and stripes. There was a sort of enclosure around the flag made by stretching ropes from stake to stake. I was ushered into this enclosure along with a number of other white prisoners, some say one hundred and twenty-five - who had been brought in from various directions' My master was adverse to display any feelings or witness the repetition of the scene enacted at the lodge and therefore hastened back the moment I touched the ground. A half-blood Indian was in charge here- He noted down the name and age of each one delivered. The list was forwarded by couriers to St. Paul and published in the Pioneer, now Pioneer Press. This was the first intimation my father had that I was still among the living and he and others bent on a like errand hastened to reach Fort Ridgely whither the liberated white were to be sent.

The prisoners at the time were not informed of the plans and only found out that they had exchanged good quarters and food for bad. We were soon marched in a body to an Indian camp a few miles distance. On the way to this camp a young brave galloped up to my side, flung a new double blanket over-robe, saying that this was from my friends, that I had just left in such an unceremonious manner, and disappeared as he had come. Some of my fellow prisoners envied my good fortune- One youth who subsequently succeeded in stealing the blanket offered me a sabre for it which he had picked up on the way. Mrs. Inefeld told me that it would just be the thing for herself and babe and that I should give it to her. I could not gainsay the pertinency of her remarks and would most likely have parted with it had it not come into my possession in such a manner. At the camp we were not quartered with families but were assigned to a large circular pit under the canopy of heaven. In daytime we had no shade and at night no shelter from cold.

We were all fed out of a large wooden chopping bowl and on a diet that was repulsive to us at first, though I soon leamed to relish it. It was dried buffalo meat that had been pounded into shreds and then packed

-19-

into skins. There were a few broken crackers mixed with this. The bowl was passed around and each grabbed a handful or two. For a beverage we had the water from a nearby swamp. Had we known that this was to last but a week we would have cheerfully endured it.

The women said to the boys, "You can get away but we with our lir tle ones have no hope in flight." After the first day we were at times allowed to leave the enclosure and stroll about the camp. Louis

Kitzmann, August Gluth and myself agreed that we would make a break for liberty. We leisurely walked to the outskirts of the camp. When cautioned not to go too far we replied that we were to get some ponies that were grazing at some distance from the camp. Having reached these we headed for the nearest timber, knowing that some stream must be near that would lead us to the Minnesota river.

Just on reaching the timber an Indian with a short handled ax came out of the ravine. He had been cutting kinikinick. He made a dash for us; we scattered, he followed me and soon laid his hand on me. He gave me to understand that if I made a second attempt my head would go off. The other boys escaped and soon met Sibley's men and retumed with them later. I was taken back to camp and the Indian who conducted me back determined that I should serve him as a means of ingratiating himself with General Sibley. The camp we occupied was fortified by several successive trenches on the side, where it was open to attack. A wide swamp bent nearly around it. It was a well chosen spot for defensive purposes.

On the day of Sibley's approach we had to carry water into camp all morning, as though the Indians were expecting a siege. At least that was the impression we received from all we saw. The Indians themselves were perhaps not fully informed as to Sibley's plans regarding them, or did not trust the reports. Towards ten o'clock we saw a dust cloud on the prairie to the southeast of us. Later we could see the glitter of the bayonets in the sun, and soon the artillery, then the infantry filed past us to a swell in the prairie. Much to my disappointment all disappeared beyond it. I had expected that they would storm the camp without delay and slaughter the Indians, little thinking what might become of us.

After waiting some time for the reappearance of the soldiers I could restrain myself no longer. I jumped into the first trench climbed up on the outer side and the same with the next although guns were pointed at me. I had become disgusted with the maneuvers of the soldiers and I was going to ascertain what they were at. I found they had gone into camp just on the other side of the swell.

I soon found a fbrmer neighbor, a Mr. Thiele who gave me the first authentic news from my people; fed me with bean soup and beef and gave me an English leather hunting coat with ever so many pockets in it. He thought it would be more serviceable than the linen duster though not much better fit. It wasn't quite so long.

I was soon approached by an orderly who told me that I must go back to the camp fiom whence I had come till the formal release would take place. Though I never had any love for mere formality I meekly obeyed the order. Soon a battalion of soldiers came over to the Indian camp. The prisoners were delivered to the officer in charge. The Indian who had frustrated my attempt at flight took me by the arm and handed me to the officer claiming much credit that he had saved my life. A hollow square was formed by the soldiers, the released were placed in the center and marched over to the camp of General Sibley, which was named Camp Release. Darkness was now approaching. We saw rows and rows of white tents, empty save that a bayonet was stuck in the sod with a lighted candle in it.

"Come boys," I said to a few of my chums, "let's stay in this. I'll spread my blanket and will go to sleep." It did not take us long to fall asleep.

Sometime in the night we were aroused with kicks and curses. Soldiers came to occupy it. We were out in the dark wondering where we might find a place where we would be allowed to rest undisturbed. Upon inquiry I was assigned to a large round tent occupied by a number of released lady prisoners and two or three little girls. I was at the same time given to understand that I was to wait upon the ladies.

Our food now consisted of nothing but rice and sugar with occasionally a cracker, that would move without being touched. Soldiers will understand what I mean. The little girls and myself had one tin dish of rice with one spoon between us. Each took a few spoonfuls and then passed the spoon to the next. I soon tired of this kind of living. If I could only find my friend Thiele again. I firmly believed that he would give me some different food but I searched in vain. If I saw a crust of bread on the ground, though trodden into the dust by the mules, I picked it up and ate it. Some brick had been hauled from Yellow Medicine and a Iarge brick bake oven erected. I watched the process of bread baking one day and while the baker was looking into the oven one of a number of loaves of bread that had been laid out to cool disappeared under my coat. I was

ashamed to share such ill gotten goods with the little girls and sneaked away and finished the loaf that day without wasting any of it, either. I was now beginning to be pestered with vermin. I went to the river bank, picked as many lice, commonly called graybacks, out of my trousers as I could find and dropped them into the river. My shirt I threw away and it too floated down the river. Then I took a bath but found the relief only temporary. Upon my arrival at Le Sueur my father gave me a thorough scrubbing with a brush and soap suds, and buried all the clothes that I had worn. He found several raw spots on my back as large as a nickel, where the lice had actually eaten away the skin. You may be shocked at my recital, but when I started to write these articles I made up my mind to give all details as far as I can remember them. I have shown you so many beams of sunshine that you will pardon me if I have called your attention to a dark shadow.

After a two weeks' stay at Camp Release we found an opportunity to get home with a provision train. The same wagon that carried me also carried four or five squaw prisoners. They busied themselves in making a pair of moccasins which, when finished, were presented to me. We experienced great difficulty in finding food on our way. We subsisted exclusively on parched corn. At the fort I was met by my father and a few former neighbors. Here for the first time since the outbreak I was to eat under a roof, from a table covered with white linen, and white porcelain dishes. I think it was the officers' mess as the companies ate their meals around the campfire on the open prairie, and it was only the first evening that I was the recipient of such a mark of favor. When I entered the lighr ed mess hall and glanced over the long tables I anticipated a feast. You can imagine my disgust when the first dish set before me was boiled rice and sugar. After a few days' sojourn at the fort my father took me to Le Sueur where he had found a temporary home for his family.

DURING THE SIOUX MASSACRE OF 1862.

My parents, in 1862, lived in Milford township, Brown county, four and one-half miles west of New Ulm. My father owned a claim upon which they raised vegetables, which did not grow plentifully. Some of these they carried to town (New Ulm) and exchanged them for a few groceries.

Our house was built against a hillside with the bare ground as a floor; two posts in front and some cross-pieces, on which some rails were fastened. These, covered with long grass or hay and topped with earth, was the roof. The side logs were plastered with yellow clay. A vegetable cellar consisted of a hole scooped out of a hillside having a hole through the earth roof, which diminished in size as it neared the surface.

At the time of the Indian outbreak we possessed no cattle of any kind, and few other belongings. One evening in August, 1862, a neighbor came to warn my folks that the Indians were on the warpath and we should go to New Ulm for protection. We went to town the next morning at daybreak; father carrying my little sister, Clara, 2 112 years old, and mother carried the baby, 3 months old. My older brother, 9 years, and [, 5 years, walked.

We met a party of four men from town, going west, to get an old aunt and her family. Two of these were the Loomis brothers. They were all killed on their return within half a mile of New Ulm.

The women and children were put in a large cellar or basement on the main street of New Ulm. The men were given guns to guard outside. A keg of powder was placed in this cellar, which the women were to ignite if the Reds should reach their hiding place.

That night a meeting of quite a number of men was held in one of the buildings nearby. They were to decide what to do.

The Indians were setting buildings on fire a short distance away, but were a bit cowardly about attacking the buildings protected by guns. By the light of burning buildings an Indian picked for his mark an arm, evidently akimbo, which protruded from the open doorway of the building, which was crowded with men. The marksmanship was good for the bone of the upper arm of my father was shattered.

The next day a company of soldiers from St. Peter arrived. The wounded, and women and children were taken by wagon train to St. Peter.

My father was taken there to a hospital; his arm was amputated, but bloodpoisoning set in and a few days later he died, leaving mother with four small children.

The mayor of St. Peter did all he could in helping all the homeless and cared for the wounded.

Among the names upon the New Ulm Indian monument on Center street is that of Ferdinand Krause, my father. He had graduated in

Germany as a minister, but on account of his freedom of thought and speech, emigrated from Halle, Saxony, in 1853, and stayed in Baltimore for three years before coming to Minnesota. My father, my oldest brother and my sister all died at St. Peter that same winter after the Indian massacre, so my mother had only myself and baby brother left. Little brother died two years later.

MRS. BENEDICT JUNI New Ulm, Minnesota