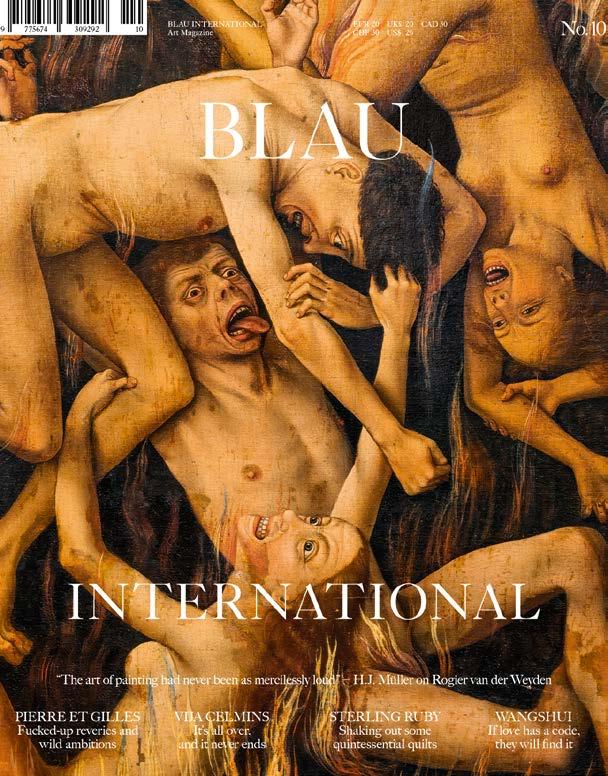

MIKE MEIRÉ

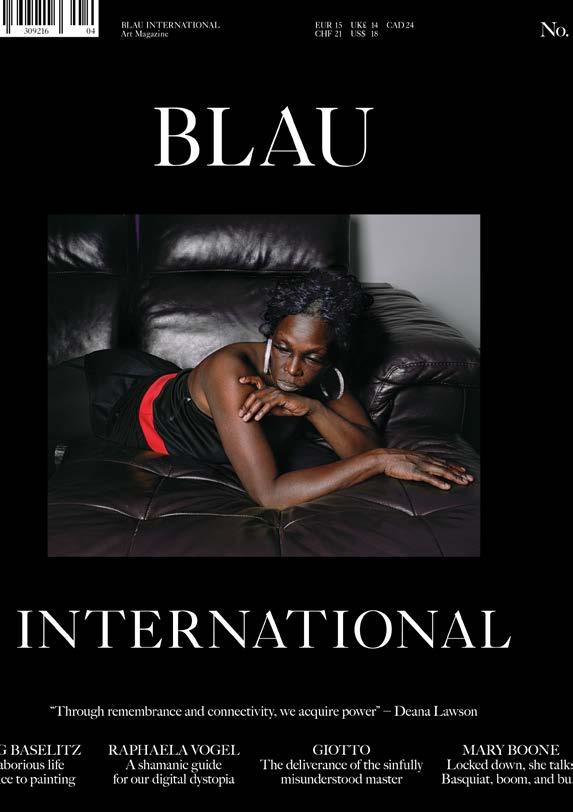

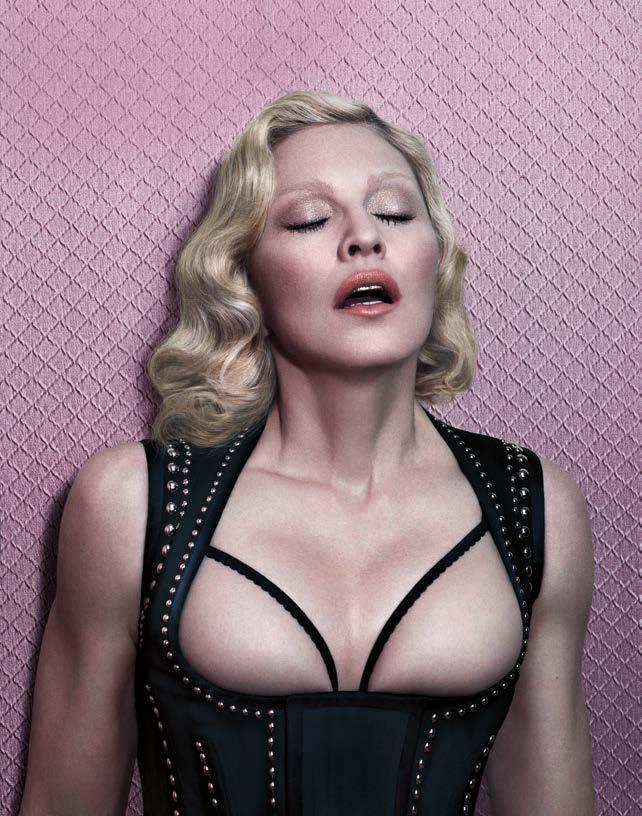

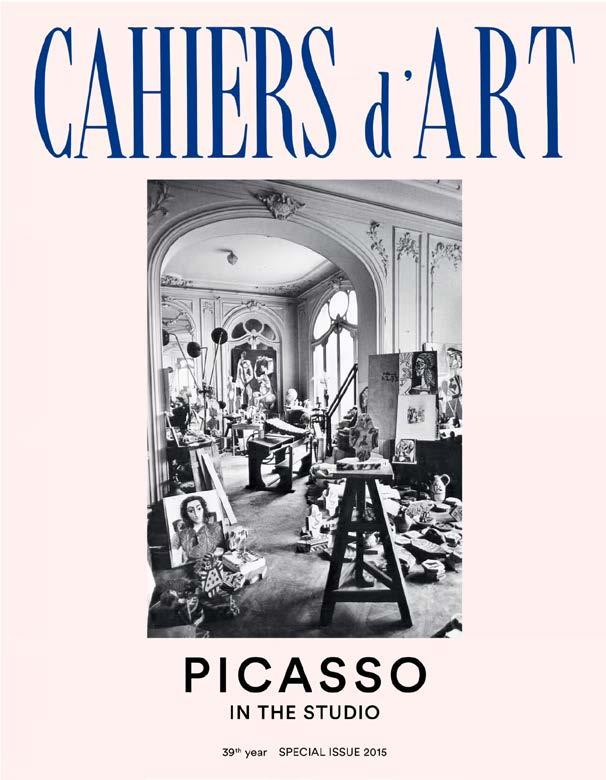

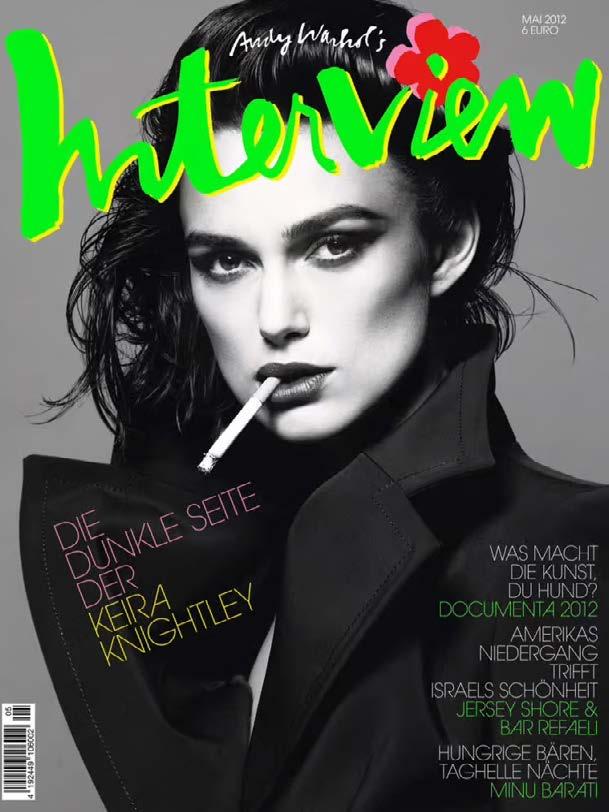

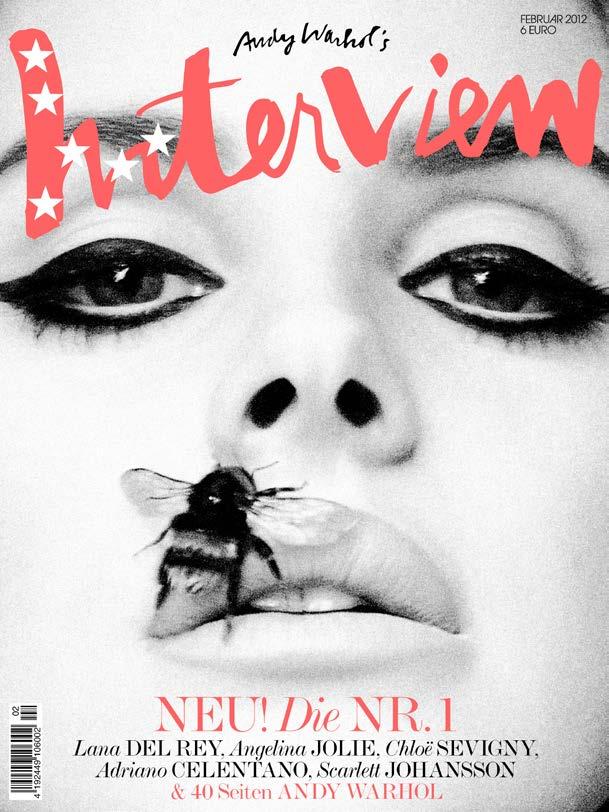

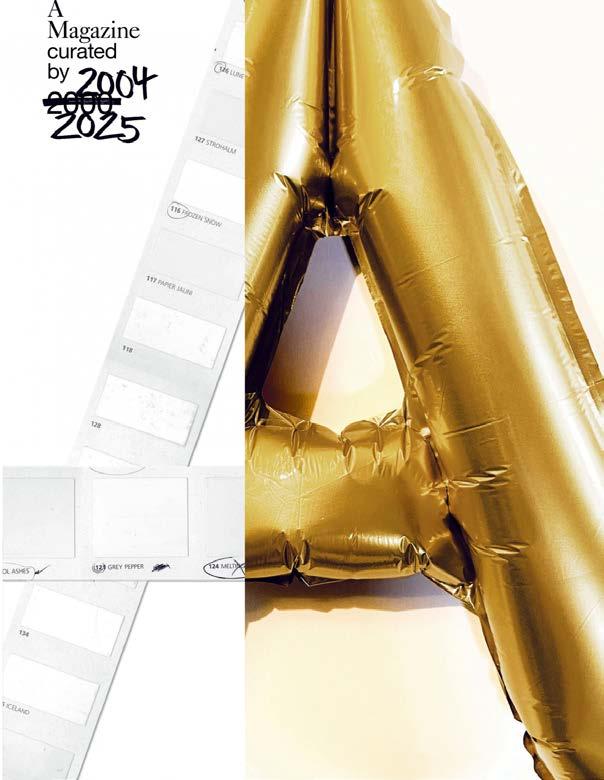

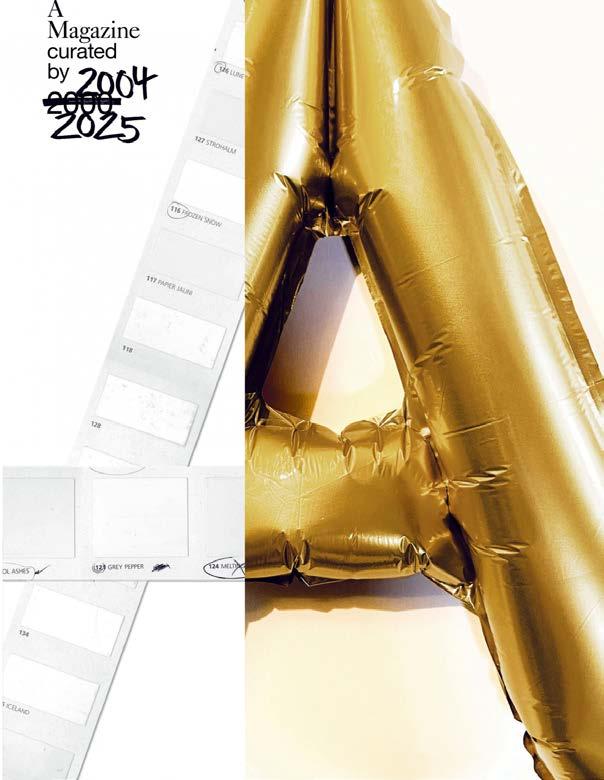

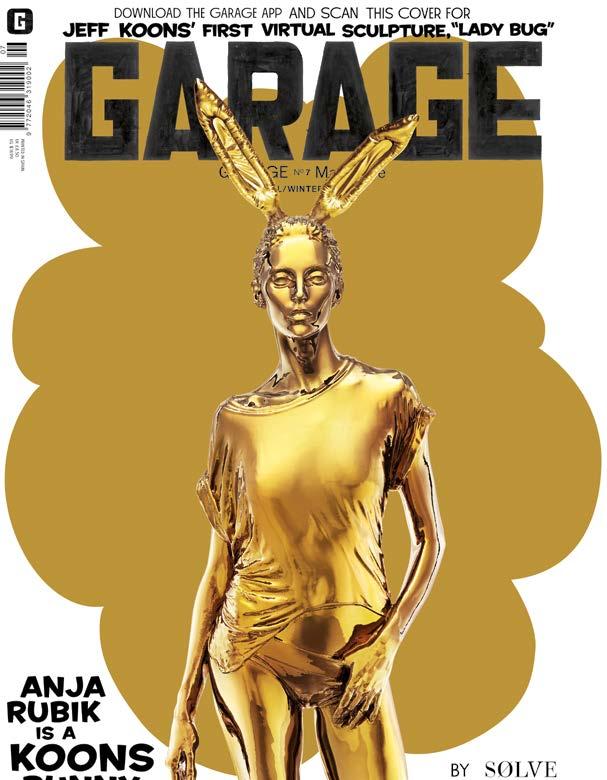

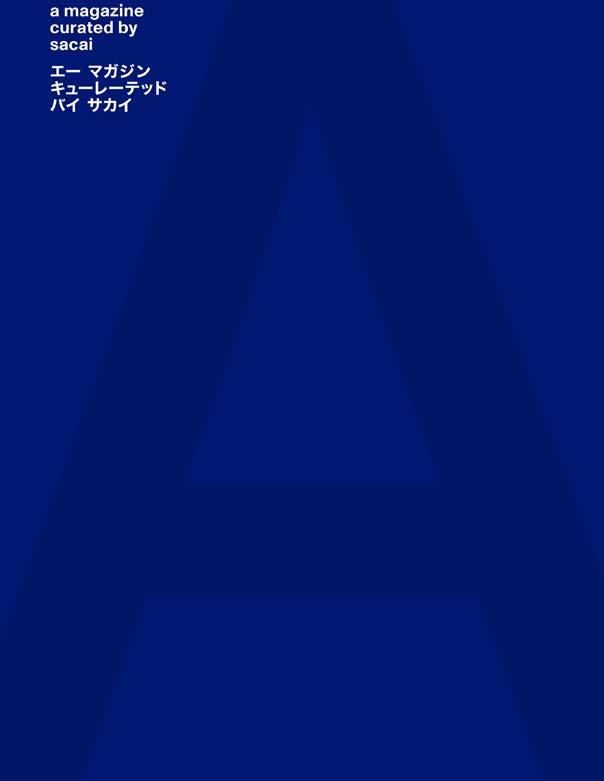

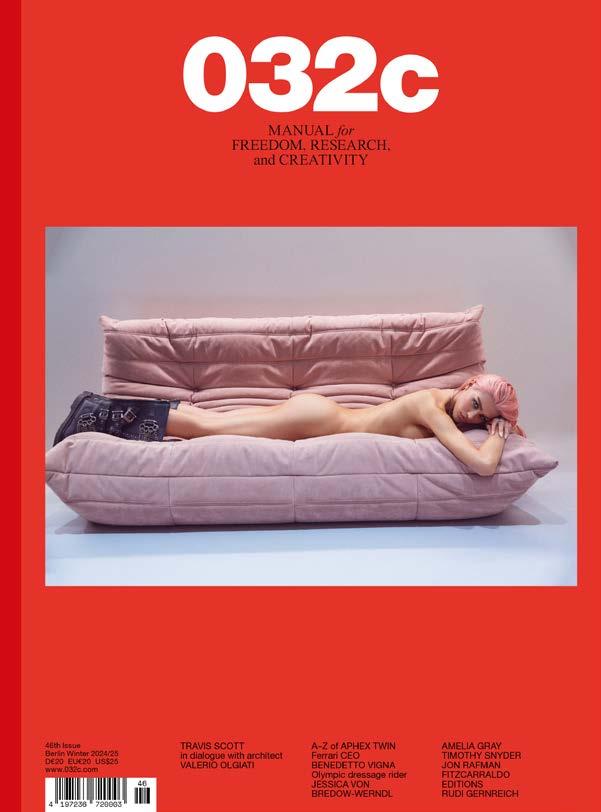

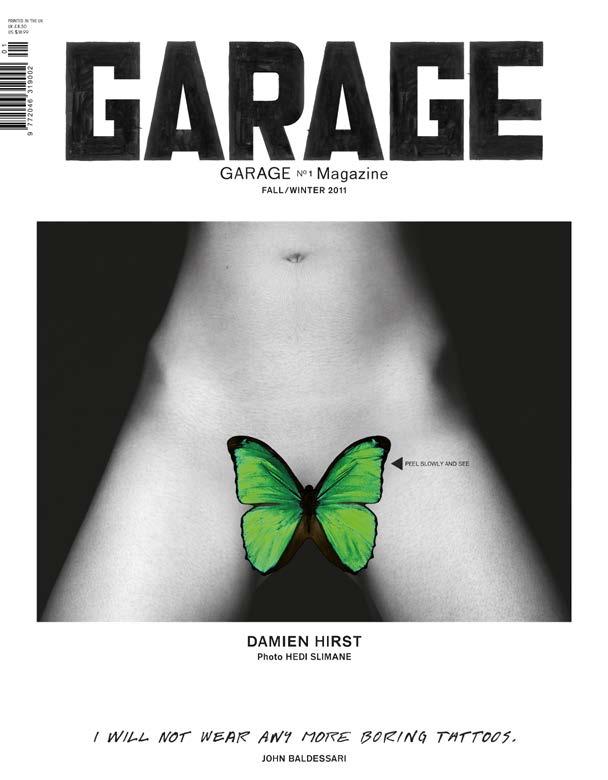

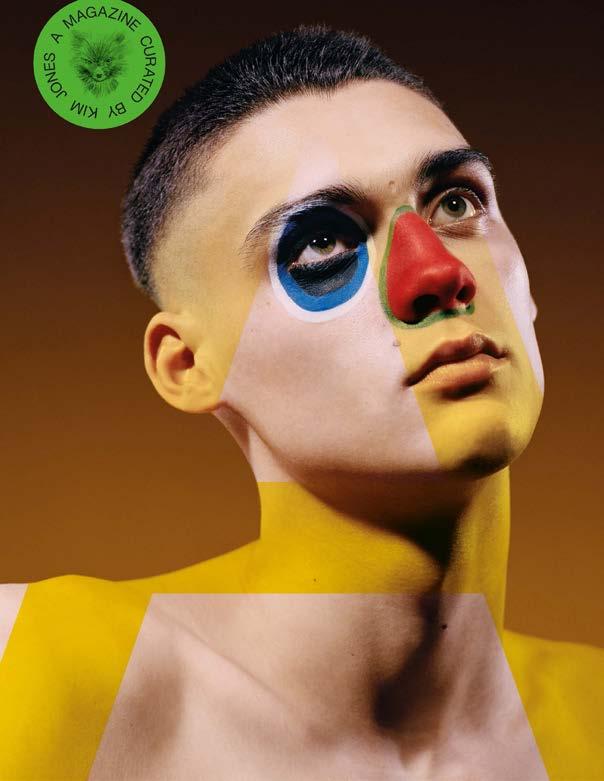

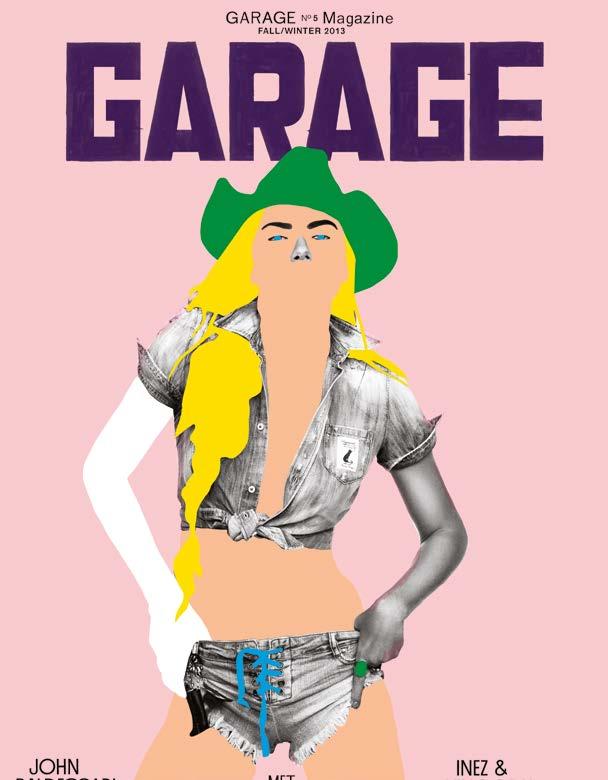

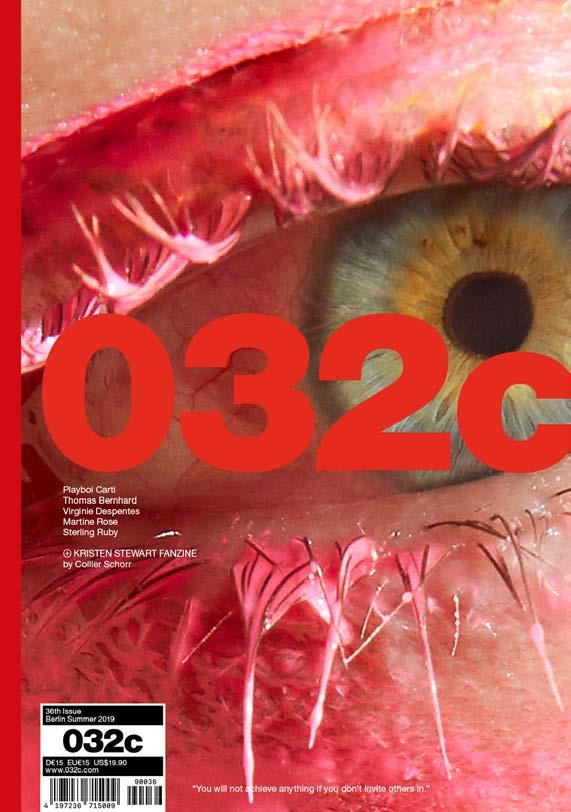

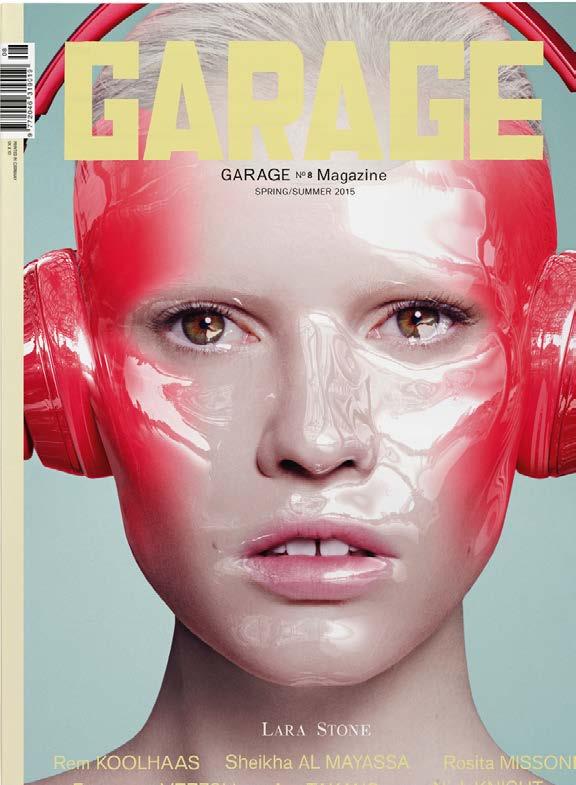

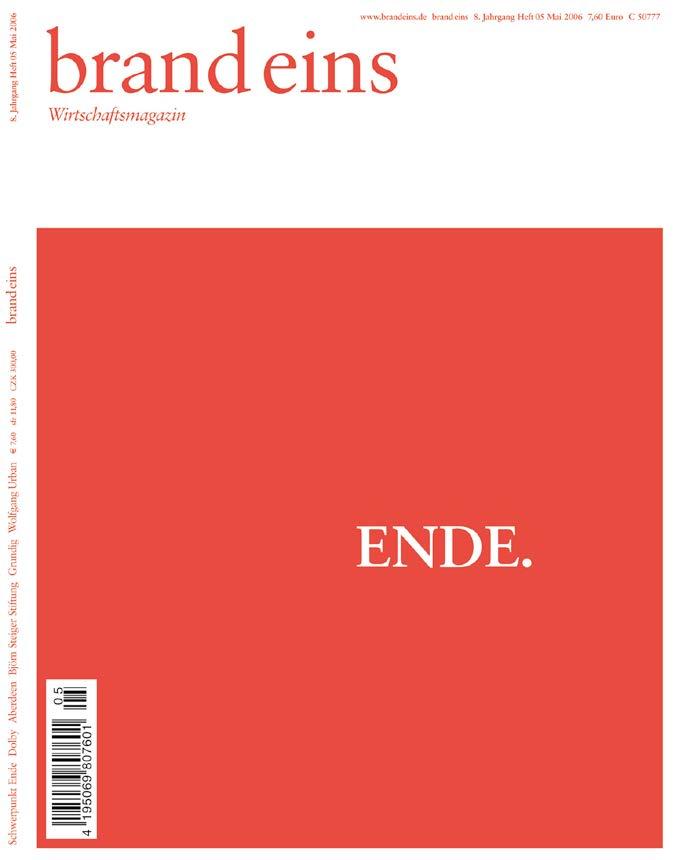

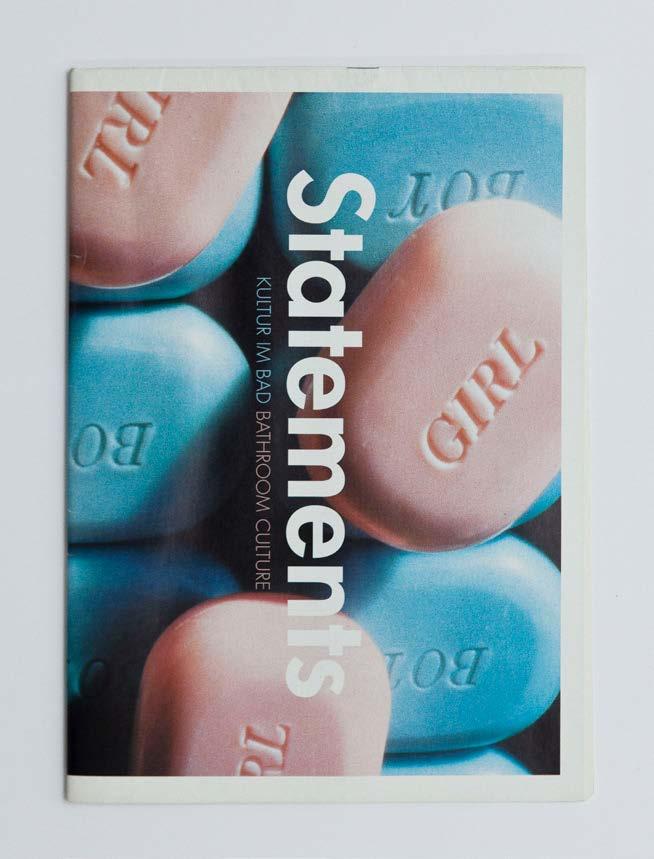

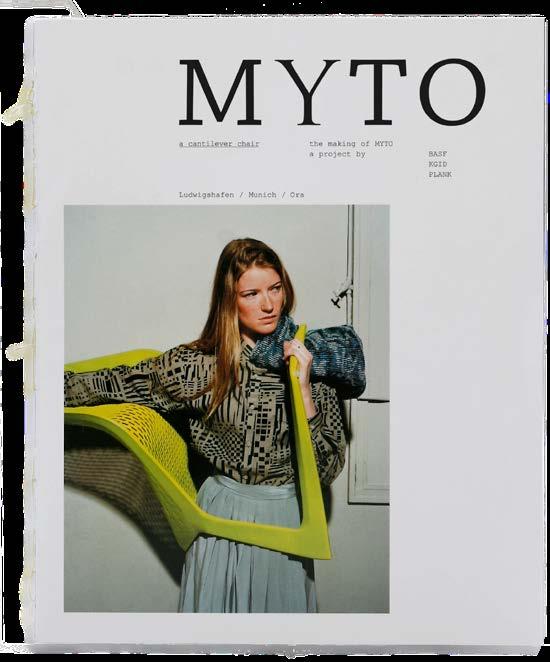

and Back cover] Covers for A Magazine Curated

[Cover

By, 032c, GARAGE, brand eins, Cahiers D‘ Art, German INTERVIEW and BLAU INTERNATIONAL; Art Direction Mike Meiré

Portrait: Markus Jans, 2025

MIKE MEIRÉ

Orchestrating

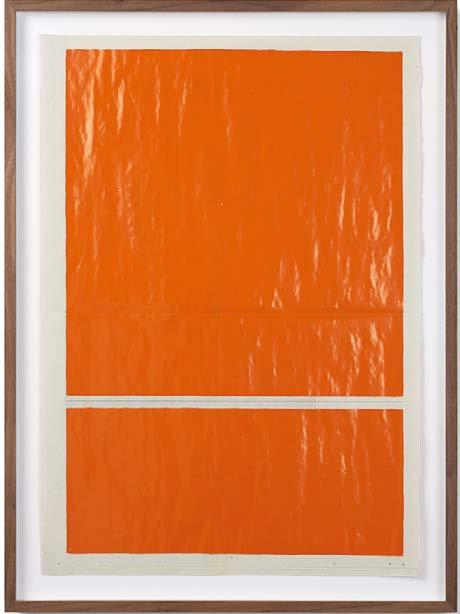

[Top] Grid Paintings

ABSTRACT PLEASURES

2013, laquer-paint on newspaper

50 × 35 cm (21 parts)

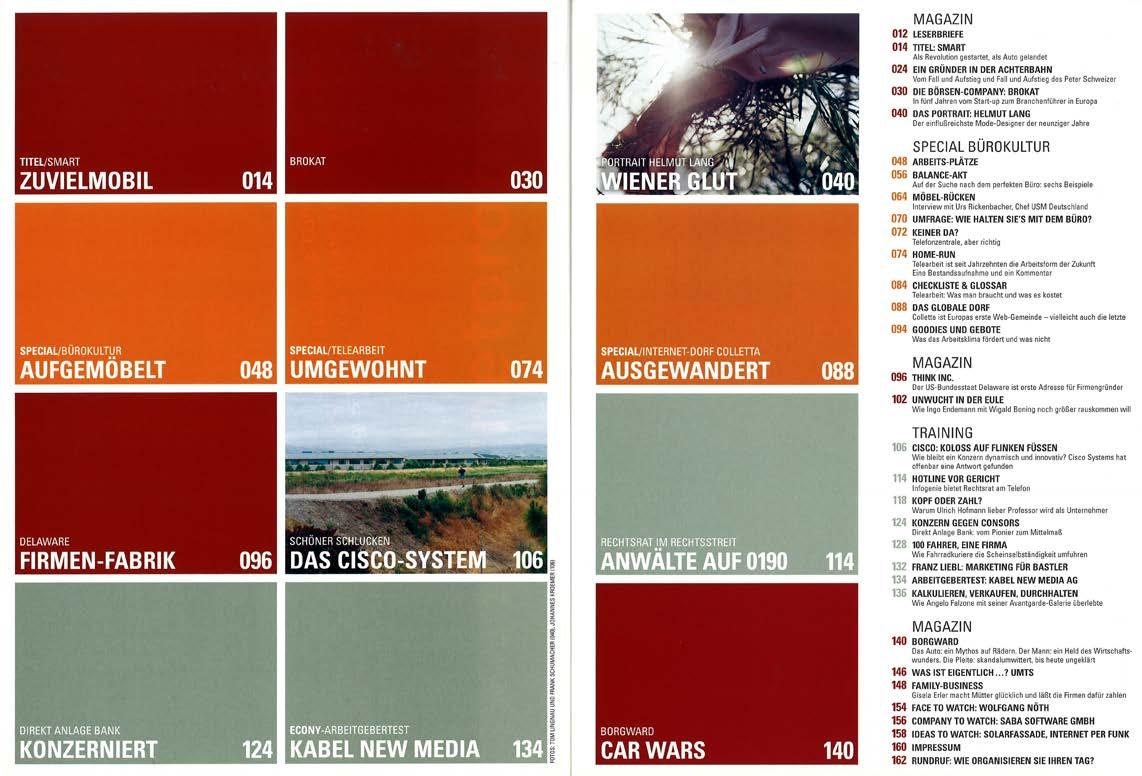

[Bottom] Excerpt (table of contents) from the Magazine ECONY, 1998 – 2001

You're in Majorca, how’s the weather? It's a little bit overcast, but this is fine. On the island, clouds are always coming and going. It's like our times, things come and go. You have to stay fluid.

That's the only certainty, isn't it, that things change constantly?

This is really what gives us and the companies we work with, the most headaches. Of course, we like a challenge, but at the same time, we have to let go of certain ways of doing things that we had got used to in the past. Things have just become more complex.

Orchestrating the algorithm

What’s the cause of all this change and complexity?

The pandemic really shifted something. Suddenly, everyone had to get comfortable with digital tools — not just tech people. We learned we could work from anywhere, and that changed everything. Work became nonstop, the idea of place kind of disappeared, and all the little rituals around how we used to communicate just faded.

When the iPhone got involved, things began to move faster — what used to be private or niche was just 'out there' for everyone to see. But, looking back, the pandemic didn't just change how we work, it changed how we connect and interact with each other.

Has the craft of design survived this digital shift?

What have we lost and what have we gained through digitization? I think the ‘craft’ just migrated into different channels. The craft is now within the code, the user interface, the UX. But that's why we have this revival of magazines, of analog qualities. For example, in London they play vinyl records in a certain bar while you drink your whiskey. And suddenly people realize, oh, the vinyl is finished after 20 minutes. But we are used to Spotify. We are used to never ending playlists.

When you put the needle on the record, it brings an awareness of physical time. I think that's really great. This is always what I think of when I start comparing how my work life has changed over the last few years, moving from magazines to strategy and so on.

What is the challenge that modern technology presents for creativity?

The big brands, T Mobile for example, they understand the situation. That there's so much information all the time, people are getting completely bored and depressed because they just cannot handle it. They don't know what is relevant and what is just entertaining. And that’s before we even get to TikTok.

Actually, I'm really affected by TikTok as well. I like it even more than Instagram. But of course, one’s mental capacity is deformed by it, in a way. I see this with my kids too. Sometimes it's hard to keep them focused on one topic for a long time. There’s this permanent state of being here, but thinking about somewhere else.

This generates a more superficial type of engagement. You see a lot of things, but it's hard to get people into the deep dive. I think this is the challenge for us as communication designers. We have to find ways to create a desirable surface, but then somehow you have a hook which says, “Okay, now is the moment where I should go deep.”

That's why the likes of Apple and other companies are coming up with these personal assistants which say, ‘Okay, for the next half hour, I have a moment of concentration.’ No SMS, no email, time to focus. In the long run, it needs a lot of discipline. And I think this is what people really have to chew on. It seems hard being disciplined these days.

Can good design give us depth worth exploring?

That's why I had this kind of mission statement, ‘aesthetics for substance’. We had already created this towards the end of the ‘90s. We understood somehow, even back then, the way things were going.

Did you train as a designer?

I never really studied. In the ‘80s, I did a couple of internships. And then there was a kind of a school project in Cologne that involved technical printing. But I never took a degree or anything like that. Rather, I see myself as an autodidact.

In 1983 I started my own Magazine, called APART. That was really my school. That and being together with like-minded people. That was the point where I started to ask myself, ‘when is something only known and when is something relevant?’

You don't have the luxury of postponing decisions anymore.

[Top] Telekom, Mobile World Congress, Barcelona, 2025

[Bottom] First issue of the magazine Apart, 1983

I wanted to figure out, why, for example, does this restaurant have tablecloths and the other not? Why, if both have tablecloths, is one full of diners, while the other one is empty? Seeing all these little things, observing, trying to find out what are the codes? What makes a certain movement, a certain thing, object, project, interesting?

This world is so obsessed with decoration. Design, can help to create beyond the surface, something which is a bit more sophisticated. Something where you understand, ‘okay, I'm leaving the level of entertainment and I'm digging into something. This could be interesting for me.’

Are you having these kind of conversations with the likes of T Mobile?

Yes, because this is really where we have to be. There's a lot of pressure on all these companies. We are driven by awareness, by money making, KPIs and so on. Everything has to reach certain performance criteria. We get used to that. But at the same time, where's the space for attitude? Where's the space for dreaming? Where's the space for poetry?

We are humans, not machines, but that doesn't mean it's always humans versus machines. I think that's more of a science fiction narrative.

In the long run we have to adapt to the fact that we live in a digitized world, we just have to learn to orchestrate the algorithm.

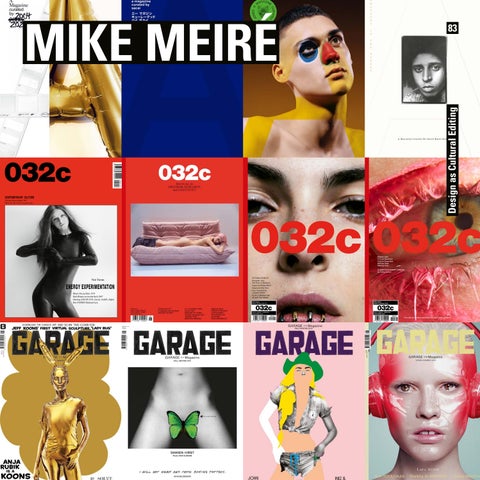

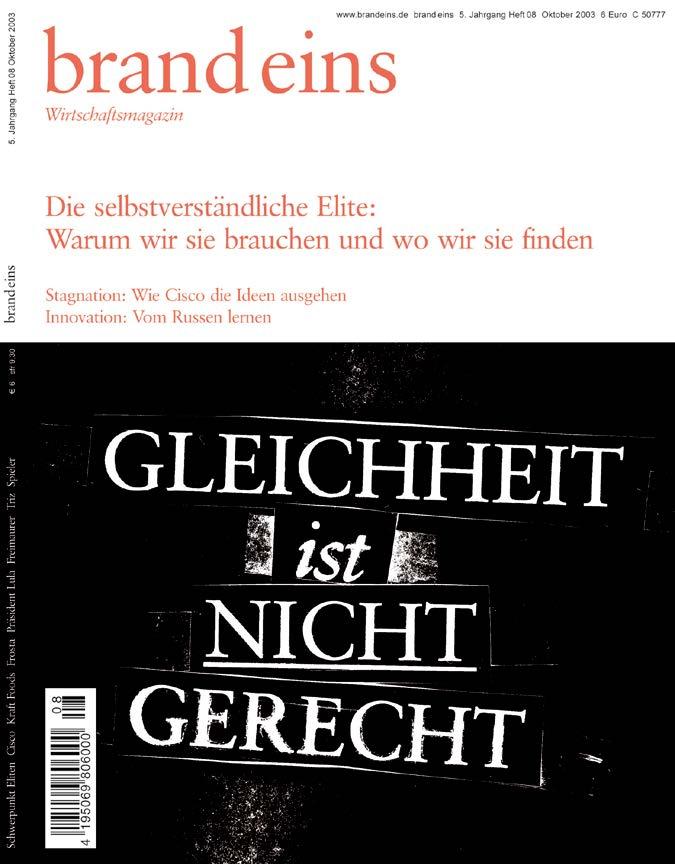

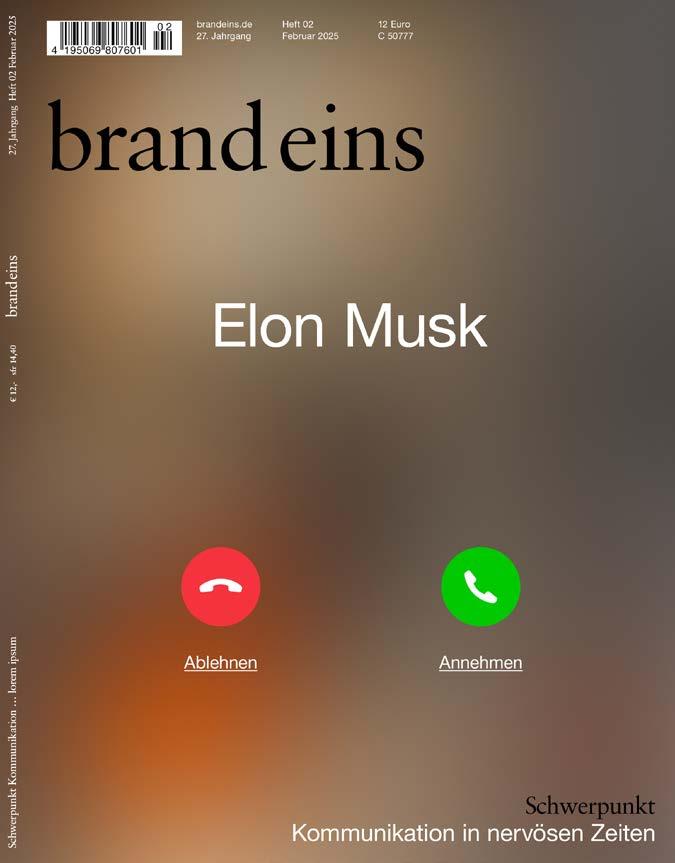

Covers of brand eins magazine

by Mike Meiré

We shouldn't see ourselves as victims. Technology is a tool. AI is a brutal disruptor in every field. It's a paradigm shift. It puts everything upside down.

Should we go back to living in caves, then? No! we got this. We’ve got to handle this. We have to face up to it, and we have to find a way to see what's in it for us.

What can designers bring to this brave new world?

As designers, we are professional dreamers, we make everything look beautiful. We have to understand, yes, the surface has to be desirable, but somehow we have to create a hook. This is where we have to fight a little bit, where we have to find the right partners in crime. This is where we can actually make a difference.

For example, brand eins the business magazine, which was founded in 1999 by Gabriele Fischer. I was there as well, so we have been working together for more than 25 years. It became a well known brand because we were able to understand there was a new economy coming.

For me as an observer, as an art director, as a creative, I understood, if you compare this to the traditional management magazines, you realize they're the young kids. They work at night, they have cables, they have keyboards. They smoke a lot, they look cool, they look exhausted too. It's a different world.

At that time, when young photographers, came into the office with their prints, I was looking maybe at 500 physical photo albums. Not like these days, PDF, PDF, PDF. No, it was physical work. You were sitting down with someone, and you spent maybe an hour or more, flipping through their portfolio. And then you chose.

Dilettant (Monoblock from 2014) on the cover of ARCH+ projekt bauhaus, 2017

But through this kind of curation I understood, this is how you generate an identity, and in the long run, this is what people are looking for, what brands are looking for. It’s the sense of everything we do. This has been lost a little bit.

The practice of design has changed, has it not?

Back then, if you designed something, if you said something, if you wrote something, it's going to be printed on paper. There is no undo button. It's a commitment. You had to think about quality, because it's not like digital. At that time, we were worried that, “Oh, my God! We wrote the name wrong. Should we put an errata in there?”

It was logistically, a nightmare. But it meant that I understood, if you design something and you are going to print it on paper, you have to be sure that it’s cool, because you cannot take it back.

There is no cultural undo button either, is there?

When I worked with Peter Saville — we had a joint venture, ‘The Apartment’ in London. When we worked together, most of the time, we were just sitting on this really cool, black leather couch, and talking. We were talking about, where's culture going? What are the codes? Should we really open the doors to culture and let industry in? Because, once we open Pandora’s box, we will sell out the things we believe in.

Nowadays this question is long forgotten. Companies need content. But it’s interesting to work as an art director, for a real magazine, with people, where we

create content. We style and design the content and bring it to the audience, and care about the audience.

We care about the response of the audience. It’s not just, ‘do you like this picture, yes or no?’ Then you click on an Instagram button. We create a space for resonance, where you have an exchange, where you talk. Where you talk about quality.

If you put it in a cultural context, the future is based on trust. It's up to you to find the people, the clients that believe in your work, and you believe in what they say.

As designers, we have a voice, we can say, ‘Listen, this is great. But maybe, if we go the extra mile, we will generate something which lasts a little longer.’ Maybe it generates a certain subconscious effect, so that we begin to get people to really start to believe in something.

As designers, we are professional dreamers, we make everything look beautiful.

How do you get into the magazines?

When I was still in my neighborhood in Cologne, a friend of ours from a different school came over. Somehow he had got the chance to make a magazine for his school. I had a reputation for being ‘the creative kid’ so he came to me for help. My brother thought it was cool too. And he quickly developed the instincts of being an efficient consultant.

Then, at some point, we realized we didn’t need to just do this for the school anymore. We understood that we could establish a platform for ourselves to speak to the world. From the very beginning I thought, maybe I am an artist? Nowadays it’s a different story, but at that time, it was very difficult to be an artist, because, you know, I was living in the suburbs of Cologne... So I used my artistic sensitivity to give the magazine an artsy feel. We even chose a name that included the word “Art” — we called it APART. Joy Division’s Love Will Tear Us Apart captured the emotion we were after: a sense of longing.

Somehow, maybe out of naivety, I was creating it in a way that was completely unexpected at that time. It broke with so many rules that some agencies saw it and called us in to see them. I was just 19, had spots everywhere, but they invited us to do pitches.

That was when we opened up our design studio and advertising agency. And then within maybe two, three years, my brother and I, we learned to run a company. I was just a curious kid, a curious teenager, growing up in the ‘80s. I was open to experimental things. We were always able, my brother and me, to cultivate that spirit. Even 40 years later, we are still curious.

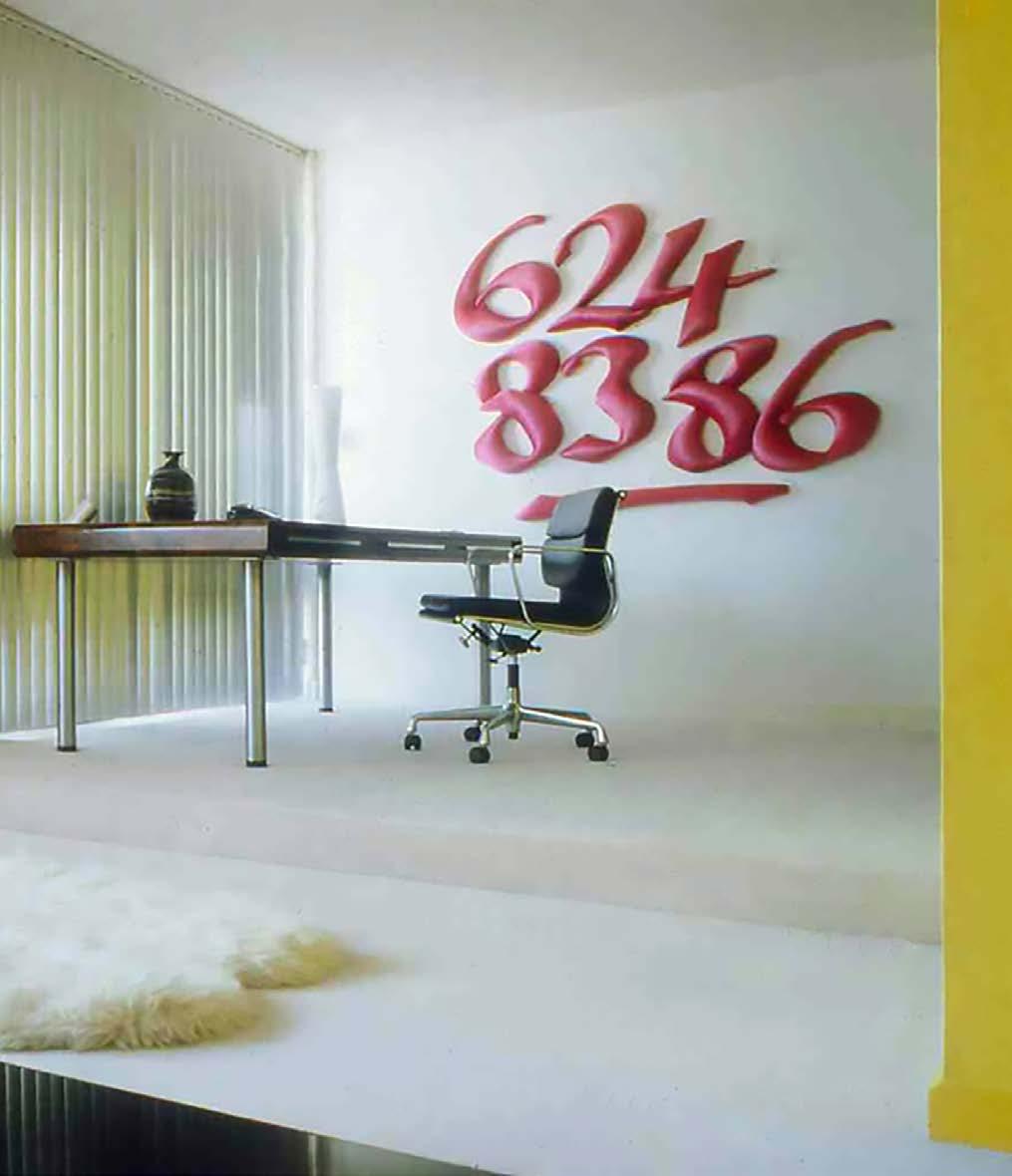

[Top left] First issue of STATEMENTS, curated as part of the Dornbracht Culture Projects during the YBA era (Young British Artists) in Mayfair [Top right & bottom] The Apartment, a project by Peter Saville and Mike Meiré in Mayfair London, 1996

Even within the madness of social media, there are moments where you get hooked.

2012, lacquer paint on newspaper

You have quite a large studio now, how has that changed your approach?

Oh yes, we are still around 60, but before the pandemic, it was 120. There's so many technical requirements for projects these days, you need people who have the necessary skills.

When we were small, I would touch everything. It’s unavoidable, you do everything and you are involved in every conversation.

Nowadays, it has evolved to a kind of orchestration, a curating processes. Picking the right people, putting the right team together, setting the right tone, giving a push in this direction. Understanding, listening.

I like to think of my studio as a place of culture. I don’t try to keep everyone busy. Rather, I try to make them aware of what we're doing here, right now.

Did you ever think of moving from print to art?

In 2009, while I was redesigning the Swiss newspaper, NZZ Neue Zurcher Zeitung, a gallerist from London, Niklas von Bartha came to me and said, “I think you're an artist, Mike, and I would like to represent you.”

At that time, while I was doing the NZZ job, I was fully occupied with the newspaper, I was working with the grid. And at some point, while I was painting over the grid, I saw a kind of a Bauhaus aesthetic, a kind of formal presence emerge.

It wasn’t a canvas. It was an ordinary, mundane thing, which you throw in the garbage at the end of the day. A functional part of the design work. But these things became something beautiful in the process. They became like abstract paintings. I call them the grid paintings.

Nicholas said to me, “Mike, I want you to focus the next three years only on paintings.” I said, “Are you serious? I can't do this. I have so many things to do.” He just said, “Do it.” And I did.

It must have taken some discipline to cloister yourself and just paint

Everything these days takes discipline. You have to put yourself into it. That’s what I did, I jumped in, even to the point where I said, ‘this is so boring!’ But then, suddenly I realized, if I paint all over everything, I see the holes. I see the folds of the object. Suddenly, I wanted to be super precise.

If you start meditating on the things you're doing and you put a certain effort into them, things get interesting.

It's the same way with digital tools. I think just now we're on this threshold, we are just bombarded with all these new things to learn, with these new channels. It gets to be too much. But at the same time, no, you know what? It keeps you alert, it keeps you young.

× 35 cm (4 parts) [Bottom left] Redesign of Neue Züricher Zeitung, 2009

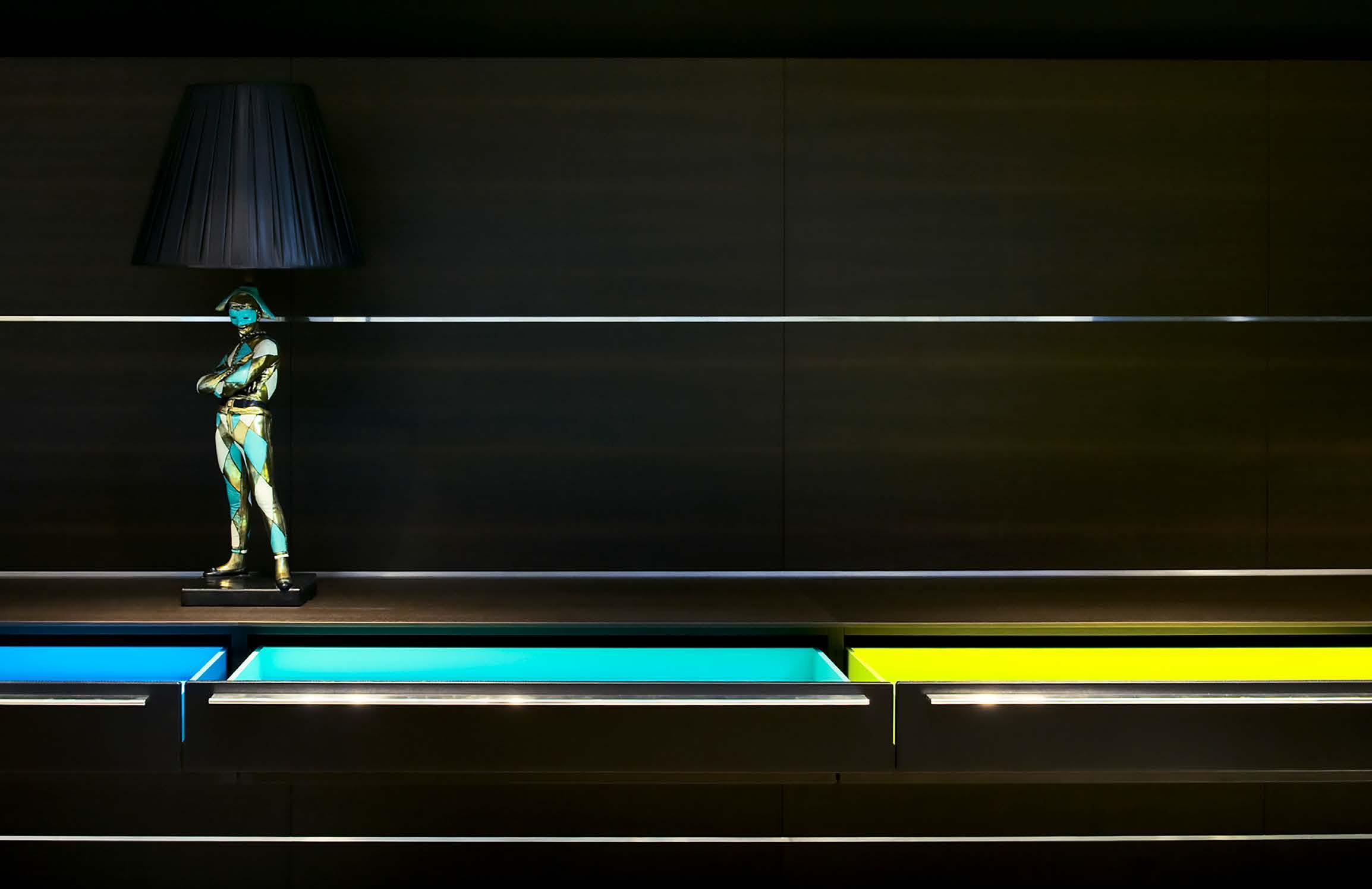

BMW Tales from a Neo Collective Future, Salone del Mobile Milan, 2022

You have to put in the work if you want the results?

I have always learned by doing. You have to do things as often as possible, until you develop a certain confidence, until you really understand what you're doing. There is no instant satisfaction in this respect. You have to really go into it.

It's easy to be so entertained that you lose track. You have to have your own inner agenda, your inner mission. You know what is at the core of it all? It's not only about selling. People need to love your brand, and then they're most likely going to buy your products. But how do you make a brand desirable?

It goes back to something which I always loved — the aura. That's the emotional logic.

How do you create, design, curate an aura that makes people think, ‘Wow, that's so fantastic!’

Why would a collector put 1000 euro into something where the physical value of the materials is just pennies. They want it because somehow it has an aura. It speaks to them.

Even within the madness of social media, there are moments where you get hooked. Why here and not somewhere else? What is it? You have to go the extra mile.

What did you bring from underground print to art direction?

Coming from the garage mentality, making magazines, that subculture where you worked on instinct, fast and very emotional. Even back then, I wasn’t picky on a signature. I wanted to find a visual language for the magazine. I was into quality and not, “hey, this is a Mike Meiré design.”

Nowadays, we have a strategy and the brand. I'm more interested in finding that thing on the street and then opening it up to culture, inviting people like Jurgen Teller to do something. Or working with Viviane Sassen, as we did in the zeros.

I have always asked, what can we do if we work on a corporate field, but we bring some kind of artistic freedom to it? Over time, I became like a bridge between the interests of the industry and the interests of the creatives. Because I had these two hearts in my chest I understood how to do this.

I have become the mediator between these two worlds.

Print documentary of the MYTO chair for BASF and PLANK. Product design by Konstantin Grcic, photographed by Viviane Sassen.

Where's the space for attitude?

Where's the space for dreaming?

Where's the space for poetry?

Dornbracht, The Farm Project, Salone del Mobile, Milan, 2005

THINK ON THESE THINGS 2009, lacquer-paint on newspaper 50 cm × 35 cm

If you start meditating on the things you're doing and you put a certain effort into them, things get interesting.

Bulthaup, Shifting Contexts, Salone del Mobile, Milan 2015

SARAH-GRACE MANKARIOUS

Design Friends would like to thank all their members and partners for their support.

COLOPHON

PUBLISHER Design Friends

COORDINATION Anabel Witry

LAYOUT Olga Silva

INTERVIEW Mark Penfold

PRINT Imprimerie Schlimé

PRINT RUN 250 (Limited edition)

ISBN 978-2-919829-12-5

PRICE 5 €

DESIGN FRIENDS

Association sans but lucratif (Luxembourg)

BOARDMEMBERS

Anabel Witry (President)

Guido Kröger (Treasurer)

Heike Fries (Secretary)

Hyunggyu Kim (Member)

COUNSELORS

Vera Heliodoro, Hyder Razvi, Olga Silva, Silvano Vidale

Support Design Friends, become a member. More information on www.designfriends.lu

Design Friends is financially supported by

This catalogue is published for the lecture of Mike Meiré "From Subculture to Strategy: Tracing the Emotional Logic of Design." at Rotondes on October 1st, 2025 organised by Design Friends.