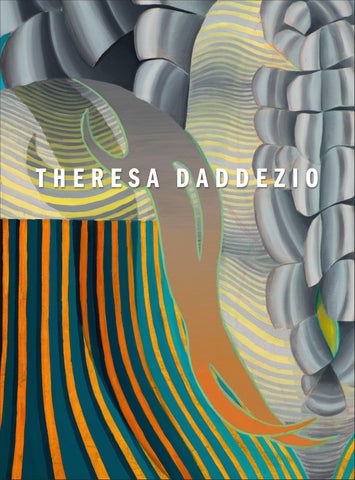

THERESADADDEZIO

THERESADADDEZIO

REWORLDING DC MOORE GALLERY InterviewwithElizavetaShneyderman

32 CYCLOPS , 2022 . Oil on linen, 50 x 38 inches

54 BECOMING & UNBECOMING AninterviewwithElizavetaShneydermanandTheresaDaddezio

ELIZAVETA SHNEYDERMAN • Could you speak to the bio-aesthetic of your work—that is, its depiction of genomic multiplication in painted forms?

THERESADADDEZIO • My work considers the ways in which the natural world is altered by human intervention and, interrelatedly, the ways in which technology adapts to the natural environment. This current series contains amalgamations, visual realizations of hybrid entities. Plant mimicry—plants and insects surviving under duress, coevolving to imitate the other sex’s reproductive organs to benefit pollination—is a concept I wanted to explore with image making. These paintings emerge as biomorphic abstractions characterized by undulating linework describing tubes, channels, or networks that carry energy and appear as organic forms. ES • I’m also curious about the motifs in each painting. They reoccur between paintings, and yet, each painting, it seems to me, is dictated by its own unique credo. What is the relationship to recurring motifs? DANTE’S FINGER , 2022 . Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches

THERESA DADDEZIO ’S PAINTERLYINVESTIGATIONS of abstraction and its taxonomies are testaments to the interspecial epoch in which we live. Ecologies and economies shape these painterly ideas—freeflowing interpretations of the natural world transform texture and color into optical scenographies which knit improbable worlds together. Despite their complexity as abstractions, the planar realities invoke plausible, visual environments. Interwoven, nonhierarchical, and symbiotic surfaces bring tactile environs into view. Vibrant ribbons, textural fields of color, and chromatic tensions are manipulated and interpellated. It is from this place of artificial-real physicality—from the harmony of human and nonhuman, organic and inorganic—that Daddezio finds kinship. We sat down in her studio and discussed everything from biological motifs, fantasy, digital influence, divinity, to worlding.

QUEEN, 2022 . Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches 76

PEACOCKING , 2022 Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches 98

TD• Well,it’s achieved through an active discovery in the process of painting. Often I’m just playing, fumbling, and figuring it out. In this study for Heart of the Andes [ p. 16 ] , I’m deciding which chroma makes the most sense spatially within this exact world. In Scarab [ p. 23 ] , the blue expanse in the center bottom quadrant is both a flat shape and suggests an underwater environment. I really like that intentional ambiguity. A lot of my color relationships come from my engagement with and teaching of color theory, especially Josef Albers, Johannes Itten, and the Hunter Color School through my graduate studies with Gabriele Evertz. The light pink hue in this series is a direct phenomenological response to the light at sunset that is reflected onto a brick wall outside my studio window at the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program. It becomes a glowing red sky 1110 FOXTAIL , 2022 Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches

TD• In the sense that I start with drawing, my work is very traditional. These drawings are often scratchy and unresolved. Certain motifs reappear as connections between separate compositions, revealing a larger narrative across a grouping of paintings. These motifs derive from observations in the perceptual world that I reduce to simplified forms, creating a short-hand for the natural/biological and industrial/ artificial. These various formal elements may appear as serpentine, volumetric, structured, or linear. Most of my drawings are in a small moleskine notebook alongside notes and reflections on day-to-day life. If I think a drawing is compelling,I’ll develop it into a painting on paper.This is often how I workshop color in my paintings. Recently, I started to adapt the painting on paper by uploading the image to my computer, digitally collaging, and recombining elements within the image. I started to think about this type of computeraided imaging as a metaphor for gene splicing and rewriting, which was partially how I ended up using these axial quadrants that create totemic compositions. I often create interrelationships between two paintings. Peacocking [ pp. 8 / 9 ] and Foxtail [ p. 11 ] are two of those works, which took some time to resolve. While working on Foxtail ,there was a point where the painting seemed complete, yet the image lacked an element of surprise. A few weeks later, I was photographing the painting to better see the composition. When the composition is seen on a screen the size of your hand, it’s easier to get a sense of tangible proportions and balance. I was noticing that the camera does this funny thing where it doesn’t quite capture the chromatic distinctions and spacing of linework, glitching into moiré-esque patterns. I was looking at the photograph and decided that this blurring between the distinction of the real painted image and its fake digital capture was an effect I wanted to incorporate.

ES • It’s clear that you have a mastery of color relationships. You know what you’re doing.

1312 OWLEYE , 2022 Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches

1514 creating striae. I essentially lifted that light to create a sense of believable, illusionistic space within my paintings. I want these paintings to be experienced as a believable fiction and the light to lead you into a space that you can enter.

TD• Fundamentally, all painting is the various combinations of line, shape, and color. Because I know the rules of illusionism to create from observation, I can intuitively break them. I don’t want the paintings to simply be beautiful observations of nature, Iwant them to agitate,be strange and unnerving in their color.In IceBloom [ pp. 20 /21 ] there is an area of saturated orange next to a bronze metallic hue that appears luminous and glossy in certain light, but as you move your position in front of the painting, the metallic loses its luster and appears as an almost sickly skin color.

ES • I’m also thinking about the paintings’relationship to light sources, specifically in context with the doctrine of“believable fictions.” How are you painting with light sources in mind, given your interest in artificial plausibility—or the potential for abstraction to inhabit realism?

ES • Another question—you gesture to this with the moiré moment in Foxtail —but in terms of how the works translate to a digital sphere, I’m curious: are you inverting or playing with this digital relationship somehow? Now that you know that our digital apparatuses can be fooled,so to speak,I am wondering if you are intentionally toying with or subverting the mechanics of their digital reproduction.

TD• Ienjoy playing with simultaneous contrast, creating vibrating edges with complimentary hues that share an equal intensity. The handmade qualities, permitting the viewer to see the under-drawing through the linen along with layers of thick and thin paint applications, are ways to encapsulate time. There is a record of the painting’s making that can be read on the surface through the directness of a thin glaze or the meticulous process of drawing a vibrating line. This record of time breathes life into the paintings and encourages the viewer to read the work both with their eyes and their physical presence, which is something I’ve always been interested in, having been involved in dance since I was a child.

ES • It’s a wholly enmeshed process.

TD• I’ll often work through an idea by recreating an image in variously scaled studies, slicing and fragmenting the composition, introducing a new color, or simplifying dense areas. It’s more about a possibility: what if a motif repeats here? Because I am inventing a lot, it helps to have something to look at to reference. Whether compositionally, GALEA , 2022 . Oil on linen, 50 x 35 inches

16 HEART OF THE ANDES , 2022 Oilonlinen , 62 x 80 1 4 inches

In Vine [ p. 31 ] there is a spiral tendril that can be read as either a vine or a telephone cord. This motif repeats in another painting but adapts to the environment in an effort to camouflage its visual language.

TD • I work on one painting at a time to the point that it feels almost complete, then I’ll begin the next one. In that sense they are serial. However, I often turn my paintings around in the studio and revisit them months later. This allows me to see the work with fresh eyes and make decisions I may not have otherwise made when I was completely engrossed with one work. This also allows works to become pairs as motifs and color combinations transfer from one painting to another. For example, Galea [ p. 15 ] is a partner to Ice Bloom . They can be separated and operate fully as individual works, but together there is a reciprocity of visual language. The interrelationships from one work to the next also give the appearance of my paintings morphing and mutating from one to the next. When I have a vision for a painting, I’m asking about how that work fits within the series. As a way to create continuity between the paintings, I started pulling elements from a previous work and adapting those forms into the painting in progress.

1918

TD •There needs to be enough diversity without being too genomically disparate... I think a lot about the work of Donna Haraway.

ES • It makes sense to me that you’re a gardener, because I feel like the work of gardening and the work of painting here is interrelated. Two genres of the same task: birthing, seeding, interpellating. You know how to crossbreed.

ES • So they’re osmotic in every dimension— TD•They self-perpetuate. ES • Like the animal kingdom. Biomimicry.

TD•Yes, my near surroundings are absorbed in my practice, whether from an irregular band of light that creates a reflection, or a motif from a previous painting.

like using collaged elements, or taping pieces of Color-aid paper directly to the canvas to determine color relationships. Recently, I rescued this orange chair from my studio building’s recycling. When placing it in front of my paintings, it totally transformed the color relationships in my work and I immediately felt like many of my paintings needed orange. It can be something really basic as pulling an object in. ES • So there’s a lot of osmosis?

In Queen [ p. 7 ] , deep red and blue floral shapes at the top quadrant appear as petals and pistils, but because of the compositional arrangement, this top section also shares a resemblance to a royal’s head in a Victorian portrait. Intentionally creating these ambiguities is a way for me to depict the concept of biological life forms adapting to appear as us. Back to plant mimicry, it’s as if the plants in an effort to garner empathy are trying to look like us. Asking, what are you humans doing? You know that I’m a big gardener—

TD• She decenters the role of the human in our current climate condition. This idea is also a big part of my work, too. The curvilinear, biomorphic shapes in my paintings become appendages to something more industrial and structured—at times these biomorphic forms are interrupted by compositional fragments, at other times they appear as if emerging from tubular structures. The compositional axis and frontal plane operates in a similar vein as portraiture, but they’re not necessarily human— they are composite forms, composed of multitudes of texture, illusion, imagery—the paintings become anthropomorphic. I think about the possibility of reworlding—an awareness of our surrounding life forms—that Haraway discusses in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene . She also proposes the idea of “making kin with” as a framework to consider the various adaptations that are taking place to survive our rapidly changing climate.

TD•I’ve found that the process of nurturing a garden from seed to fruit is very similar to creating a painting: there is an anticipation, a sense of the unknown, always an element of surprise when something, be it an image or a plant, manifests. There is only so much pre-planning one can do, ultimately the image or plant has a mind of its own. There is a kind of material vitality expressed in paint. Jane Bennett in Vibrant Matter: APoliticalEcologyofThings describes the material vitalism implicit in all substances and I would add that pigments, as minerals derived from the earth, when understood through the lens of other animate lifeforms, move much slower than our human sense of time permits us to fully grasp, there is a sense of deep time.

ES • Not to get too cerebral, but it sounds like the paintings also function as receptacles of your own environs—embodying studio light, absorbing the color around you. This could also be said of your artistic whims vis-à-vis your reusing of certain motifs or patterns. Do you work serially?

ES • Yeah, gene pool. I get this feeling that in terms of their content, there’s that relationship to this genome or genetic biopool, but taking that metaphor and also extending it to the actual life of the paintings as they wobble and sit and bleed across one another in space is intriguing to me. Where is Donna Haraway here for you?

ICE BLOOM 2022 . Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches 21

ES • Otherwise it’s all just an illustration of divinity.

2322 SCARAB ,

TD • Yes, but there’s also a dove in her painting. She’s doing things that are totally unorthodox for the time, when either you have figurative painting or you have something that’s geometric, flat, or totally abstracted. But she’s symbolically combining those languages as an invitation to play and not feel bound by any one prescribed painterly orthodoxy.

TD• I think the work is situated within the Modernist canon. Yet instead of adhering to any one particular pedagogy of image-making, I’m selecting and remixing certain approaches. The flatness and frontality of the image becomes complicated by my use of trompe l’oeil, illusion, volumetric form. However, this recombining of image-making strategies is never just for the sake of the image superficially. There is a lineage in my work that I trace to painterly approaches of Georgia O’Keefe, Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, and Sonia Delaunay via compositional and decorative elements of Art Nouveau and Art Deco. I’m playing with prescribed ways of creating space and recombining them, creating something new from that. I enjoy operating in a space of intentional ambiguity between the forms and what they represent—there is a nearness to abstraction, yet the work still operates very much within direct perceptual observations. The flower, tree, mountain, or body of water is reduced to its core elements, becoming a symbol of something organic. I also draw from Hilma af Klint in ways that I don’t know how to fully articulate because I am hesitant to talk about mysticism in art, which I think is up to the viewer. If they have a transcendental experience, then that is legitimate, but you can’t make an object that actually is in and of itself transcendental.

TD • I’m using a mix of synthetic and natural pigments, some that have been in existence for centuries and others that were only developed within the past 50 years. 2022 Oil on linen, 50 x 35 inches

ES • How do you contend with painterly legacies of spatial illusion and abstraction, given the works’fidelity to illusion, trompe l’oeil, fantasy and unfantasy, becoming and unbecoming?

ES • Not to mention, there’s real contemporaneous color.

ES • It’s devotional.

TD• There is something ouroboric about an image attempting to illustrate creation. What I found fascinating about Hilma af Klint’s Guggenheim show was that her work was clearly not just abstract as Modernism has characterized.

2524 SUNBATHER 2022 Oil on linen, 80 x 62 inches

ES • Multiplicity, or the simultaneity of life forms— TD•The intermeshing, too. ES • It’s not top-down monotheism—it’s a dispersed realm.

ES • So they’re truly symbiotic.

Considering deep histories embedded in pigment, the concept of Gaia theory comes to mind, that essentially the earth is a unified living organism connected by mycorrhizal networks underground. It’s a contemporary theory in studying the natural world that harkens back to ideas in many pagan cultures and religions.

2726

TD• We’re at a time where we’re rediscovering a lot of pagan or indigenous knowledge, especially now that science supports what people knew for centuries. In our rooftop garden, my fianc and artist Greg Lindquist and I are growing“TheThree Sisters”— corn, squash, and beans—described in Braiding Sweetgrass by botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer. These three plants thrive when grown together, mutually creating shade, attracting beneficial and deterring invasive insects, and providing essential nutrients through their intertwined root systems.

TD • I’m reflecting on the ways we are changing, and in the process, destroying our home and habitat. But, we’re not separated from it, we’re not different. My work is an acknowledgment of human destruction, and an optimistic exploration of possible futures for lifeforms co-evolving. MELISSUS , 2022 . Oil on linen, 52 x 38 inches

ELIZAVETA SHNEYDERMAN is aNew York-based curator and researcher. She is curator at the Riga Technoculture Research Unit ( RTRU Her essays on contemporary art and visual culture have been published in Artforum, Animation Studies Journal, BOMB Magazine, TheBrooklynRail ,and Rhizome , among others.

CHRYSALIS SERPENT , 2022 . Oil on linen, 38 x 32 inches 2928

USING A HYBRIDIZATION of biological and botanic forms, Theresa Daddezio’s work explores notions of consciousness, fragility, and sexuality within the language of painting indebted to the history of abstraction. Her compositions create a compressed visual environment where shapes take on “a believable fiction” of nearly identifiable forms, with the spatial and textural juxtapositions created by the artist transforming lines into resemblances of flora, figures, and vessels. Daddezio’s application of paint creates optical oscillations of flatness, depth, vibrancy, and subtlety. Earthen tones commingle with synthetic palettes, complicating the delineation of the natural versus the artificial and reflecting the technological lens through which today’s natural world is examined. Daddezio is based in Brooklyn , NY. She received an MFA from Hunter College in Visual Art and BFA at SUNY Purchase in Painting and Drawing. Her selected exhibitions include Painting As Is II , Nathalie Karg Gallery, New York , NY; Augurthyms , Hesse Flatow, New York, NY; Altum Corpus , DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY; Carbona Sunrise, Transmitter Gallery, Brooklyn, NY; A Mind of Their Own , Pentimenti Gallery, Philadelphia, PA; Three , DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY; Known: Unknown , New York Studio School, New York, NY; Abstraction in the 21 st Century , the University of Hawai’i, Manoa; Rhythms, Rhymes, Repetitions , Studio Kura, Itoshima, Japan. Her work has been featured in Art Maze , Hyperallergic , The Queens Ledger , Bushwick Daily , and The L Magazine . She participated in the Sharpe Walentas Studio Program (2021–22) in Brooklyn and in the Wassaic Residency Project in Upstate New York (2018). 3130 , 2022 . Oil on linen, 36 x 24 inches

THERESADADDEZIO VINE

This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition THERESA DADDEZIO DC Moore SeptemberGallery8–October 8, 2022 Catalogue © DC Moore Gallery, 2022 ISBN:978 0 9993167 8 8 Becoming&Unbecoming © ElizavetaShneyderman, 2022 Catalogue Managers : Heidi Lange & Edward De Luca Design: Joseph Guglietti l Interview Editor:Greg Lindquist Photography © Steven Bates Printing: Brilliant cover:GALEA, 2022 (detail). Oil on linen, 50 x 35 inches DC MOORE GALLERY 535 West 22 StreetNewYork,NewYork 10011 212.247.2111 dcmooregallery.com