Expect smart thinking and insights from leaders and academics in data science and AI as they explore how their research can scale into broader industry applications.

Predicting the Next Financial Crisis: The 18-Year Cycle Peak and the Bursting of the Al Investment Bubble by Akhil Patel

“Insuring Non-Determinism”: How Munich RE is Managing Al’s Probabilistic Risks by Peter Bärnreuther

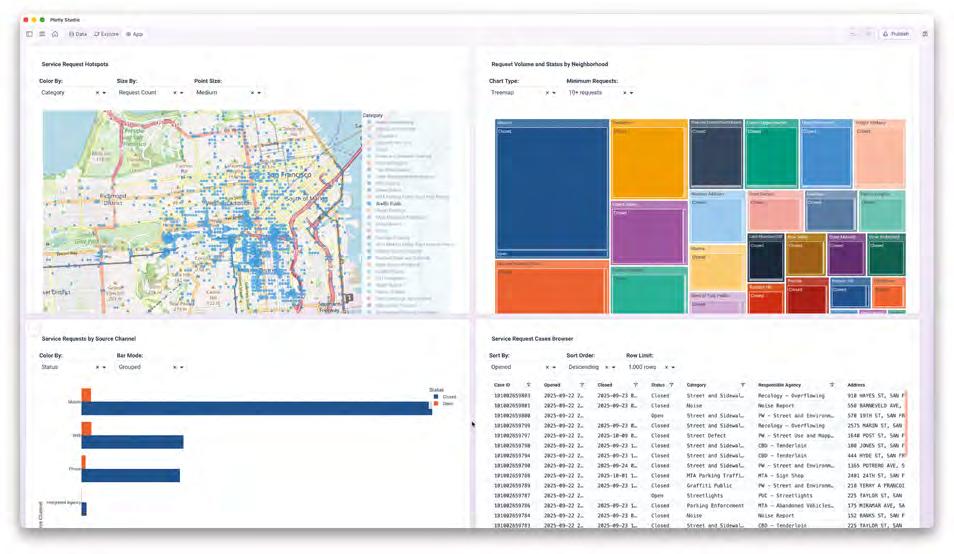

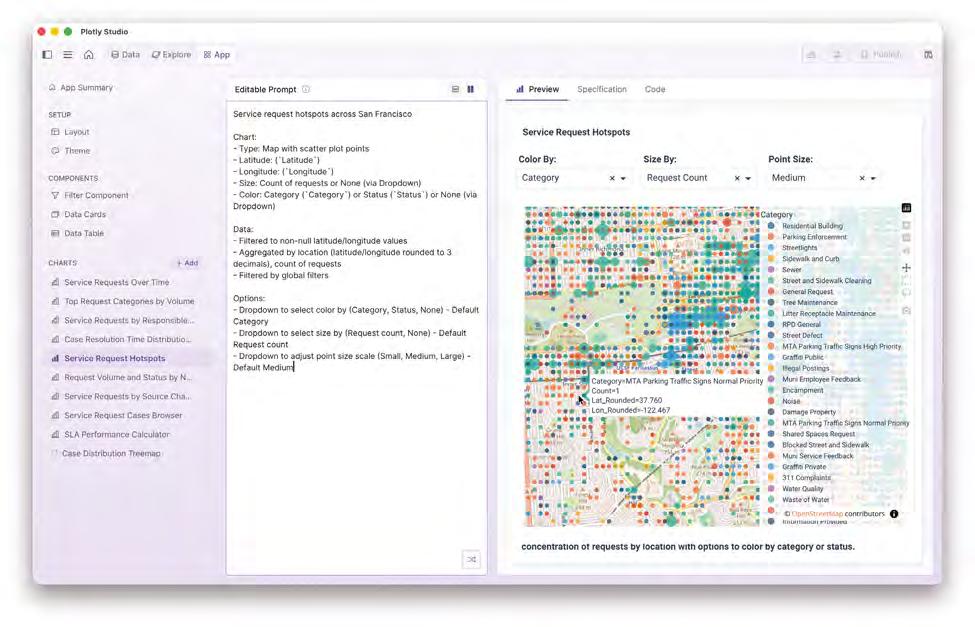

How Al is Transforming Data Analytics and Visualisation in the Enterprise by Chris Parmer & Domenic Ravita

Helping you to expand your knowledge and enhance your career.

Hear the latest podcast over on

CONTRIBUTORS

Ahmed Al Mubarak

Piyanka Jain

Nikhil Srinidhi Saurabh Steixner-Kumar

Biju Krishnan

Akhil Patel

Chris Parmer

James Duez

Francesco Gadaleta

Nicole Janeway Bills

EDITOR

Damien Deighan

DESIGN

Imtiaz Deighan imtiaz@datasciencetalent.co.uk

Data & AI Magazine is published quarterly by Data Science Talent Ltd, Whitebridge Estate, Whitebridge Lane, Stone, Staffordshire, ST15 8LQ, UK. Access a digital copy of the magazine at datasciencetalent.co.uk/media.

DISCLAIMER

The views and content expressed in Data & AI Magazine reflect the opinions of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the magazine, Data Science Talent Ltd, or its staff. All published material is done so in good faith.

All rights reserved, product, logo, brands and any other trademarks featured within Data & AI Magazine are the property of their respective trademark holders. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by means of mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Data Science Talent Ltd cannot guarantee and accepts no liability for any loss or damage of any kind caused by this magazine for the accuracy of claims made by the advertisers.

As we begin another new year, the data and AI world finds itself at an interesting inflection point. On one hand, we’re witnessing the emergence of technologies that promise to fundamentally reshape how enterprises operate. On the other hand, we’re confronted with increasingly urgent questions about value realisation, investment sustainability, and the practical realities of implementation at scale.

This tension between promise and pragmatism runs throughout our latest issue, beginning with our cover story from Ahmed Al Mubarak of Howden Re on agentic AI and context engineering. Ahmed explores what may well be the defining enterprise AI trend of 2026: the rise of autonomous AI agents capable of decision-making and task execution. His focus on context engineering for unstructured data addresses a critical capability gap that has long hindered AI adoption in real-world business environments.

The timing of this focus is deliberate. Industry analysts widely predict that 2026 will mark the year when AI agents transition from experimental proof-of-concepts to production deployments at scale across enterprises. Organisations that have spent the past two years testing and learning are now preparing to operationalise these systems. Yet as the article demonstrates, success will hinge not just on the sophistication of the agents themselves, but on our ability to engineer the contextual frameworks that allow them to operate effectively with the messy, unstructured data that dominates most business environments.

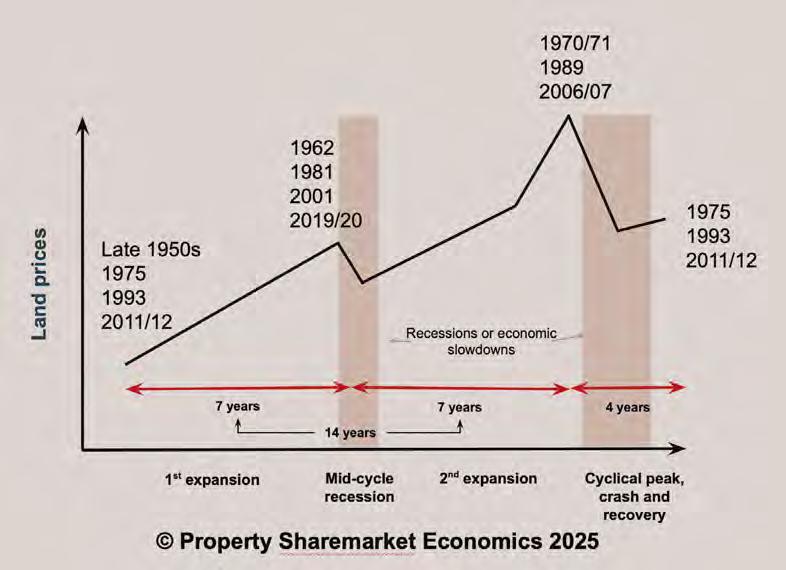

This forward-looking optimism, however, must be tempered with cleareyed realism about the challenges ahead. Akhil Patel offers a provocative contribution that serves as an essential counterweight to the prevailing AI enthusiasm. He is predicting that the AI investment bubble will burst within the next 12-18 months, coinciding with the peak of an 18-year economic cycle and potentially triggering the next global financial crisis.

Whether one agrees with Patel’s predictions or not, his analysis demands serious consideration. The capital flowing into AI has reached extraordinary levels, yet tangible returns remain elusive for many organisations. This disconnect between investment and value creation is precisely the kind of imbalance that has historically preceded market corrections.

The practical path forward emerges in our other featured contributions. Piyanka Jain examines how central decisioning systems are poised to replace traditional dashboard-centric business intelligence, a shift that reflects the move from passive reporting to active, AI-driven decision support. Nikhil Srinidhi’s article examines the architectural challenges of building data systems that can balance the flexibility AI demands with the control and governance that enterprises require.

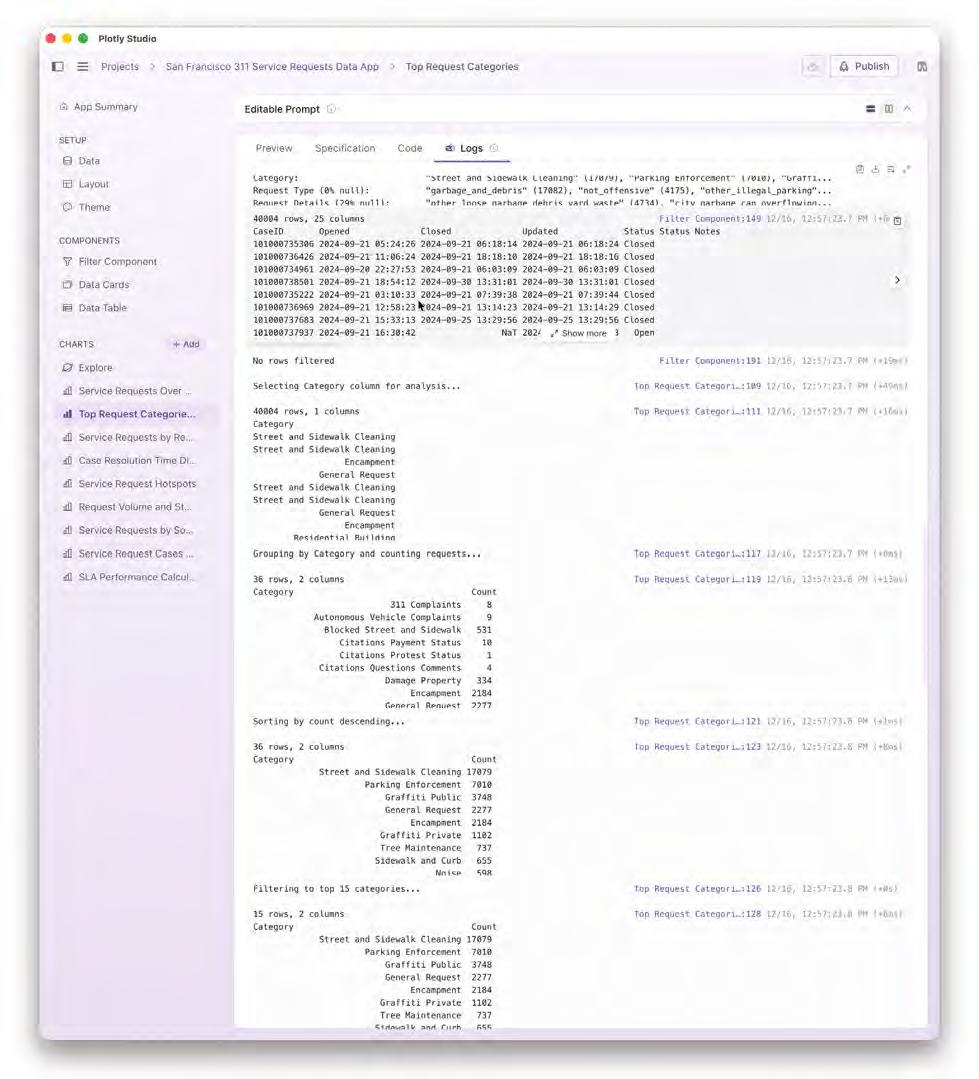

Biju Krishnan in ‘Measuring an Earthquake with a Ruler,’ challenges the conventional wisdom around AI ROI measurement. He argues that traditional metrics are fundamentally inadequate for assessing transformative technology. Meanwhile, Chris Parmer from Plotly demonstrates how AI is already transforming enterprise data analytics and visualisation, providing concrete examples of value creation today rather than tomorrow.

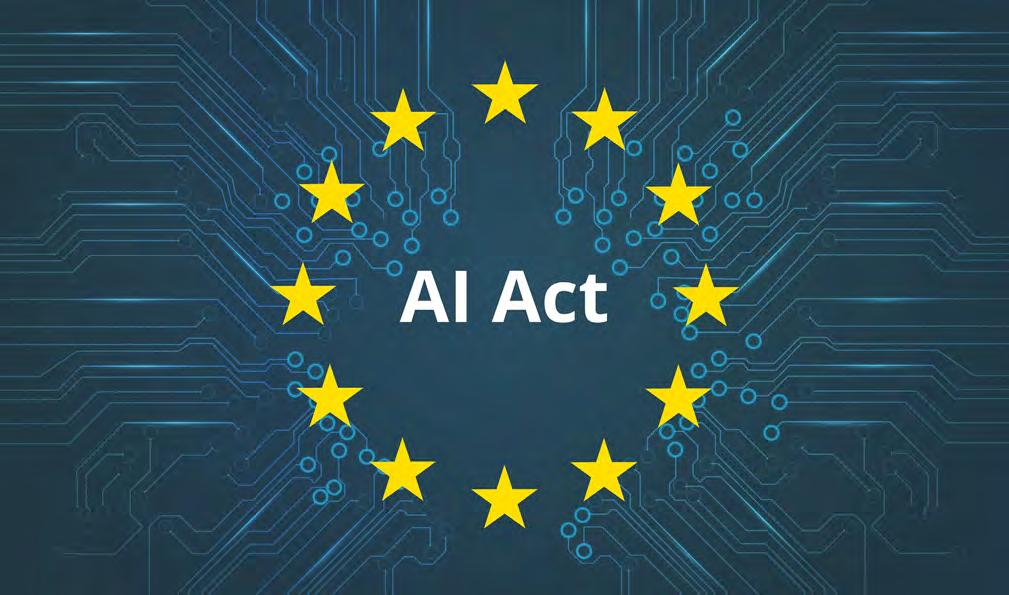

As these technological advances accelerate, the regulatory landscape is also evolving. James Duez provides essential guidance on what the EU’s AI Act means for business, risk, and responsibility, a timely reminder that innovation must be matched with governance.

What emerges from these diverse perspectives is a more nuanced picture than either the AI evangelists or sceptics typically paint. Yes, agentic AI and advanced analytics hold transformative potential. Yes, 2026 may well mark an inflection point in enterprise adoption. But realising this potential will require not just technical sophistication but also architectural wisdom, measurement discipline, regulatory compliance, and perhaps most critically, honest assessment of where we are creating genuine value versus where we are simply riding a wave of capital and hype.

BRIDGING THEORY AND PRACTICE:

REWIRE LIVE 2026 - 5TH MARCH - FRANKFURT

The gap between AI’s promise and its practical implementation is precisely why we’re once again co-promoting Rewire LIVE 2026 on March 5th at the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt. This event represents exactly the kind of honest, businessfocused conversation our industry needs as we navigate the transition from experimentation to scaled deployment.

Unlike technical AI conferences, Rewire LIVE is designed specifically for business leaders grappling with real implementation challenges. The program focuses squarely on business models, organisational change, and ROI – not model architecture or coding frameworks.

Last year’s attendees from Deutsche Bank, Roche, Munich Re, Lufthansa, Novartis, DHL, Bayer, BioNTech, and over 30 other organisations came together to tackle the hard questions around architecture and integration, governance frameworks, and workforce augmentation. The interactive mastermind sessions, where participants work through real business challenges collaboratively, provide exactly the kind of peer learning that helps separate genuine opportunity from hype.

As we stand on the cusp of another significant year for enterprise AI adoption, events like Rewire LIVE offer an essential forum for the kind of pragmatic, business-focused dialogue needed right now.

Places are strictly limited, and for more information and registration, visit rewirenow.com/en/resources/event/ai-that-actually-works/

As we move into 2026, the organisations that will thrive are those that can hold both these truths simultaneously: embracing the genuine innovations in AI while maintaining rigorous standards for practical implementation and value delivery. We look forward to continuing these critical conversations with you, both in these pages and in person in Frankfurt.

Damien Deighan Editor

Aslarge language models (LLMs) evolve, one principle has become unavoidable in my day-to-day work: the quality of the input governs the quality of the output especially when the inputs are messy, multi-format, and spread across the enterprise. For years, many of us leaned on OCR, vision models, and increasingly elaborate prompts to coax LLMs into reproducing the structure of source documents. That works until it doesn’t. Real-world content varies wildly by layout and language, and often mixes dense prose with tables, figures, scans, handwriting, and screenshots. The result is brittle pipelines and prompts that need constant tweaking. What has emerged in response is context engineering: a disciplined way to design, structure, and deliver exactly the right information, in the right format, at the right time, so the model can actually do the task at hand (Schmid | 2025 | philschmid.de).

In my own practice as a data scientist, I’ve built solutions that transform raw reports into usable data for AI applications and business intelligence. Some models did a credible job turning financial statements with embedded tables into Markdown; most failed to preserve the table’s original semantics and layout. The deeper challenge was variability. Semi-structured tables in financial reports change year-to-year, company-to-company, and country-to-country. Language localisation adds another layer of ambiguity. Prompt engineering helped up to a point. But as I kept rewriting prompts to fit the next exception, it was clear that the problem wasn’t only the instruction. The problem was the context. Context engineering systematises the ‘what’ to unlock the ‘how’ we design the information environment; data, knowledge, tools, memory, structure, logic, and environment, that surrounds the model so it behaves predictably and productively (Mei et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org).

AHMED AL MUBARAK is a recognised UK global talent in machine learning and artificial intelligence, currently working as a Director of business Intelligence and data science at Howden Re. With a strong background in data strategy, AI integration, and digital transformation, Ahmed focuses on leveraging emerging technologies to drive innovation and efficiency across global business operations. His professional journey combines technical expertise with strategic insight, reflecting a deep commitment to responsible and impactful AI adoption.

I use a practical definition: context engineering is the discipline of shaping what the model sees and can do before it generates a token, ensuring the task is plausibly solvable with minimal improvisation (Schmid | 2025 | philschmid.de). In other words, it is not just better prompting; it is the deliberate combination of content, constraints, and capabilities that make LLMs useful inside complex workflows. Anthropic company makes a similar distinction between prompt engineering (instructions) and

context engineering (curation and delivery of the right evidence and tools) for agentic systems (Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com).

To make this concrete, I frame context engineering as layered components that the agent can rely on throughout its run. I often present the following table when onboarding stakeholders, because it clarifies how each piece contributes to reliable outputs.

CATEGORYCOMPONENTDESCRIPTION

Knowledge LayerData

Knowledge

Operational LayerTools

Memory

Structual LayerStructure

Behavioural LayerContext

Canonical, layout-preserving representations of source documents (text blocks, tables with header-cell linkage, figures with captions, entities, citations)

Domain rules, glossaries, policies, and examples e.g. underwriting guidelines, regulatory clauses

External capabilities the agent can call (OCR, table/figure extractors, search, calculators, unit converters, translation)

Session or persistent stores of prior decisions, reviewer feedback, and approved phrasing

Target schemas, section templates, and output contracts (JSON, doc templates)

Logic Guardrails and rules ('cite every number', 'prefer newest reguations', 'no PII')

Integration LayerEnvironment

Connectors, access scopes, and orchestration (indexes, queues, export targets)

PURPOSE / FUNCTION

Supplies grounded evidence the model can recombine without losing structure

Ensures outputs are domain-correct and consistent

Extends beyond pure text generation into action and computation

Provides continuity, reduces repeat errors, and enables learning over time

Gives the agent a shape to write into; improves reproducibility

Encodes operating norms that reduce ambiguity and risk

Makes the context usable within enterprise systems and compliance regimes

This framing aligns with the literature: surveys now describe context engineering as a holistic practice that couples retrieval, processing, and management of contextual inputs to LLMs (Mei et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org), while practitioner sources emphasise the importance of shaping what the model ‘sees’ and the tools it may invoke (Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com; LlamaIndex | 2025 | llamaindex.ai).

PROMPT ENGIN EERING FOR SINGLE TURN QUERIES

Unstructured content is everything that refuses to sit neatly in relational tables: emails, PDFs, slide decks, scanned forms, spreadsheets with evolving columns, charts, images, and handwritten notes. The practical obstacles are well-known to anyone who has tried to automate enterprise reporting. Reading order on multi-column pages is easily scrambled. Side-by-side tables lose header–cell relationships. Figures become detached from captions and units. Equations, stamps, and watermarks confuse naïve OCR. Multilingual fragments collide with domain jargon. Without a layout-preserving representation and a disciplined selection of context, LLMs hallucinate links

between cells, misinterpret numbers, or simply ignore crucial evidence.

In my experience, two constraints matter most. First, selecting the right context: the agent must retrieve enough evidence to be correct but not so much that the window is clogged with irrelevant material. Second, fitting the token window: the context must be compact, structured, and deduplicated, so the model sees just what is needed, exactly once. That means we cannot treat the document as a blob of text. We must convert it into a structured substrate so the agent can query tables as cells with headers, figures with captions and alt text, sections with IDs, entities with types then index those pieces for targeted retrieval (LlamaIndex | 2025 | llamaindex.ai).

tool name

tool input/outp ut parameters tool

query: Annotated[str, "A language query or question."]

) → str :

"""Useful for retrieving knowledge from a database containing information about XYZ. Each query should be a pointed and specific natural language question or query."""

<code>

return retrieved_knowledge

ENTERPRISE DATA TODAY: WHERE THE MESS LIVES Enterprise data is scattered by design. Some live in email threads and calendar invites. Some sit in OneDrive or SharePoint, some in Slack or Confluence, some in S3 buckets with cryptic prefixes, some in line-of-business portals. Even ‘simple’ files arrive in a dozen types of PDFs of varying provenance, images and scans, spreadsheets with hidden columns, or mixed-language reports from regional teams. If you manage to pull the right files, the next problem is semantic: extracting the right slices from unstructured or semi-structured formats while preserving their meaning. I have found that the fastest path to reliability is to normalise all sources into a layout-preserving, canonical

JSON that becomes the single source of truth for generation and export. Tools like modern document parsers and layout engines produce consistent elements: pages, blocks, tables, figures, entities, citations, without flattening away structure. On top of that canonical layer, we build a hybrid index (vector + lexical + metadata) and label each chunk with jurisdiction, line of business, effective dates, language, and freshness. The agent retrieves evidence bundles per section top-k passages, required tables, and key figures bounded to the token window, then writes into a target schema. Compared to ‘send the whole PDF to the model,’ this approach is auditable, scalable, and much cheaper.

To build integrations with hundreds of foundational libraries and forge relationships with their maintainers, contributing back to upstream projects through careful diplomacy.

02

Canonical JSON Format

To create a representation language rich enough for complex spreadsheets, simple enough for basic text documents.

03

Cutting Edge Quality

To handle unhandleable documents – scanned PDFs, embedded charts, complex layouts requiring visual understanding via Vision Language Models, Object Detection Models, and Computer Vision techniques.

And Generative LLM model to handle the text in the document.

One subtle but important shift in 2025 has been the rise of AI configuration files ; machine-readable context and instructions checked into the repository, such as AGENTS.md, CLAUDE.md, or copilot-instructions.md. Instead of scattering the ‘first context’ across prompts and tribal knowledge, teams standardise how agents should behave in a specific codebase or project. The file encodes the project structure, build/test commands, code style, contribution rules, and references. Agent tools read the file automatically and inject its content into their working context (GitHub | 2025 | github.blog; agents.md | 2025 | agents.md).

A recent work-in-progress study examined 466 opensource repositories and found wide variation in both what is documented and how it is written; descriptive, prescriptive, prohibitive, explanatory, conditional, with no single canonical structure yet (Mohsenimofidi et al | 2025 | arxiv. org). That variability matches my experience: AGENTS.md is most powerful when it encodes not just instructions but also context logic , the guardrails that determine how an agent chooses and uses evidence. If you want reproducible behaviour, version your context alongside your code.

When I propose context engineering to stakeholders, I describe it as a lightweight ‘operating system’ for agents. Its job is to orchestrate how data, knowledge, tools, memory, structure, logic, and environment come together at run time.

The ingestion pathway accepts sources from email, OneDrive/SharePoint, Slack/Confluence, S3, and direct uploads. Parsing combines OCR and layout detection to preserve headings, reading order, footnotes, sideby-side tables, figures with captions, and equations. Canonicalisation converts everything to JSON with strict linking between headers and cells, captions and figures, and cross-references. Indexing builds hybrid search over all elements with rich metadata. Selection composes compact evidence bundles per section that fit the window. Planning decomposes the task into sub-goals mapped to tools: compute KPIs, normalise units, summarise exposures, reason about compliance. Drafting writes section-bysection into target schemas with per-paragraph citations. Validation runs numeric, structural, and compliance checks. Export renders multiple formats PDF, PPT, HTML from the same canonical draft. Feedback writes reviewer edits into memory, so the next run starts smarter.

Standardised Elements

Title Section header

Narrative Text Body content

Table Structured data

Image Visual content

This pipeline turns a static model into a programmable, tool-aware writer. It also reduces risk. Grounded evidence and per-paragraph citations curb hallucination. Target schemas unlock automated QA. And the context logic protects against failure modes such as stale regulations or missing loss runs (Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com; DAIR. AI | 2025 | promptingguide.ai).

HANDS-ON DEMO: WRITING

TECHNICAL REPORT WITH AN AGENT

I’ll anchor the above with a real-world scenario I build frequently: producing a quarterly insurance technical report from scattered content. The company asks the AI agent to deliver a print-ready PDF, a presentation-grade PPT, and an HTML page with live citations. The data arrives in every shape imaginable: scanned policy schedules; emails with embedded tables; spreadsheets whose columns change annually; photos of damage; prior reports in multiple languages. Prompt engineering alone will not tame this variety.

The run begins with intake that preserves layout. Content from email, OneDrive, Slack, Confluence, and S3 is parsed so reading order, headings, footnotes, and sideby-side tables survive extraction. Each artefact becomes canonical JSON, not a flattened blob. Tables retain header–cell linkage and include text grids, optional HTML, and a faithful image snapshot. Figures carry captions and alt text. This universal representation makes mixed-language pages and embedded charts intelligible to the agent without losing structure (LlamaIndex | 2025 | llamaindex.ai).

Before querying anything, the agent receives a short AGENTS.md-style brief. It states the audience and tone, the mandatory sections (Executive Summary, Exposure Profile, Loss History, Coverage Analysis, Recommendations, Appendices), the approved phrasing for sensitive topics, and the guardrails: cite every number, prefer the newest regulation, redact PII, use UK spelling. It also enumerates registered tools with their scopes: table reconstructor, risk ratio calculator, currency converter, date harmoniser, translation helper, and templating engines for PDF/PPT/

HTML. This ‘first context’ constrains behaviour and prevents the tool from wandering.

For each section, the agent composes a bounded evidence bundle. For Loss History, it retrieves the five-year claim table with date, cause, paid, and case reserve; a figure showing quarterly frequency; and a passage that explains the spike in Q4. It computes frequency and severity, calculates loss ratios, normalises currencies and dates, and annotates each paragraph with its source IDs. Tables are rebuilt from structured cells, not pasted as screenshots. Captions remain attached to their charts. If evidence is missing, the agent flags the gap and suggests next steps instead of inventing data. This retrieval-aware writing loop produces text that is faithful, traceable, and ready for review (Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com; DAIR.AI | 2025 | promptingguide.ai).

Quality assurance runs in parallel. Validators check totals within tolerance, enforce header–cell alignment, and ensure every required section is present. Unit and date normalisers catch silent inconsistencies. A compliance pass redacts PII and scans for prohibited phrasing. Any discrepancy becomes a visible note for the agent to resolve by fetching better evidence or marking a decision for human review. Editorial changes flow back into memory, so the next report begins with the newest boilerplate, the latest regulatory references, and the team’s approved tone. Publishing is simply rendering the same canonical draft into multiple formats. The PDF is print-ready for underwriters and auditors, the PPT distils each section into a slide with highlights and exhibits, and the HTML carries deep links into the evidence log so reviewers can jump from a claim statistic to the source row. Because everything stems from the same structured draft, there is no drift between formats.

Several small techniques pay outsized dividends. I keep evidence bundles under a hard token budget and prioritise diversity of sources over repetition. I strip duplicate passages aggressively at retrieval time to avoid polluting the window. I store units and currencies explicitly alongside values in the canonical JSON and normalise them before generation. I treat tables as first-class objects: headers, data types, totals, footnotes, and units are embedded and validated. I make captions mandatory for figures and link them to the nearest paragraph to prevent orphaned visuals. I push style and compliance into context logic: casing, spelling (en-GB vs en-US), phrasing constraints for risk disclosures, and redaction rules. Importantly, I version the context schemas, briefs, rules alongside the code, because context is now part of the software artefact (GitHub | 2025 | github.blog; Mohsenimofidi et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org).

When a model fabricates a number, the instinct is to tighten the prompt. In my experience, fabrication is more often a context failure. The model did not see the right evidence, or it saw too much contradictory evidence, or it lacked a rule that forbade speculation. Retrieval noise, stale documents, and silent unit drift are common culprits. The remedy is upstream: curate the index, privilege freshness in the ranking, annotate units and dates, enforce ‘no evidence → no claim,’ and keep explicit gaps visible in the output. Another failure mode is format fidelity: tables that look right but misalign headers and cells. Treating tables as objects with validations, not pictures, prevents subtle integrity loss. A third is scale drift as tasks grow longer and agents call more tools. Here the fix is to encode planning: require the agent to produce a plan that maps sub-tasks to tools, then execute with explicit inputs/ outputs logged in memory. These patterns are echoed across practitioner guides and research agendas on agentic systems (Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com; Villamizar et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org; Baltes et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org).

Context engineering benefits from clear metrics. I measure groundedness (share of sentences with traceable citations), section completeness (mandatory fields present), numeric integrity (totals within tolerance, unit consistency), layout fidelity (table header–cell alignment, caption attachment), and editorial effort (redlines per thousand words). On the operational side, I track token budget adherence, tool error rates, and time-to-publish. These are not abstract KPIs; they pinpoint which part of the context pipeline needs attention: index quality, selection heuristics, rules, or validators. Methodological guidance for LLM-in-SE studies underscores the need for rigorous, reproducible evaluation when agents interact with real artefacts (Baltes et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org).

Agentic coding tools have normalised the idea that we should document for machines, not just humans. The adoption of AGENTS.md-style files in open-source shows teams actively shaping their agents’ context–project structure, build/test routines, conventions, and guardrails then versioning that context in Git. The emerging research suggests styles and structures vary widely, but the trajectory is clear: context is becoming a first-class software artefact (Mohsenimofidi et al. | 2025 | arxiv. org). In my view, the same pattern will define enterprise reporting, customer service, finance ops, and risk management. As tasks lengthen and tool calls multiply, the backbone of reliable automation will be a context OS: layout-preserving data, explicit knowledge, callable tools, durable memory, structured outputs, enforceable logic, and a well-integrated environment.

I started this journey believing that better prompts would fix unreliable outputs. After building dozens of pipelines on top of documents that resist structure, I now believe something different. Prompting is necessary; context engineering is decisive. When we treat context as an engineered system – complete with schemas, indexes, rules, and validators – LLMs become competent collaborators rather than gifted improvisers. In the insurance report demo, context engineering turned chaotic inputs into a grounded, auditable narrative that ships as PDF, PPT,

and HTML on schedule. The payoff is consistent across domains: fewer redlines, faster cycles, clearer audit trails, and models that learn from feedback. The discipline is still evolving, and conventions for documenting machinereadable context are far from settled. But the direction is unmistakable. The next generation of AI systems will be built on the quiet infrastructure we place around the model, not only on the cleverness we push into the prompt (Schmid | 2025 | philschmid.de; Anthropic | 2025 | anthropic.com; Mei et al. | 2025 | arxiv.org).

Anthropic. “ Effective Context Engineering for AI Agents ” 2025 anthropic.com engineering/effective-context-engineering-for-ai-agents

Baltes, S. et al. “ Guidelines for Empirical Studies in Software Engineeri ng involving Large Language Models ” 2025. arxiv.org/abs/2508.15503

DAIR.AI. “ Elements of a Prompt | Prompt Engineering Guide ” 2025 promptingguide.ai/introduction/elements

GitHub. “ Copilot Coding Agent Now Supports AGENTS.md Custom Instructions (Changelog )” 2025 github.blog/changelog/2025-08-28-copilot-coding-agent-now-supports-agents-mdcustom-instructions/

Horthy, D. “ Getting AI to Work in Complex Codebases ” 2025 github.com/humanlayer/advanced-context-engineering-for-coding-agents

LlamaIndex. “ Context Engineering: What It Is and Techniques to Consider ” 2025 llamaindex.ai/blog/context-engineering-what-it-is-and-techniques-to-consider

Mei, L. et al. “ A Survey of Context Engineering for Large Language Models ” 2025 arxiv.org/abs/2507.13334.

Mohsenimofidi, S., Galster, M., Treude, C., and Baltes, S. “ Context Engineering for AI Agents in Open-Source Software ” 2025 arxiv.org/abs/2510.21413

Schmid, P. “The New Skill in AI is Not Prompting, It’s Context Engineering” 2025 philschmid.de/context-engineering

Villamizar, H. et al. “ Prompts as Software Engineering Artifacts: A Research Agenda and Preliminary Findings ” 2025 arxiv.org/abs/2509.17548

PIYANKA JAIN is the CEO of Aryng and AskEnola. With decades of experience with global enterprises, she specialises in analytics strategy, decision science, and the practical adoption of AI. She is the bestselling author of Behind Every Good Decision and a leading voice on the responsible application of AI within analytics and adjacent fields.

Fordecades, dashboards served as the standard interface between people and data. They gave leaders visibility they never had before and helped formalise the way organisations reviewed performance. Their rise marked a shift toward data-informed cultures. Yet, in 2025 and beyond, their limitations are becoming undeniable. Insights are fragmented across systems, data lives in silos, and human interpretation often clouds truth with bias. The result is decision latency and inconsistency when speed and precision are what define market leaders.

Fortunately, a new architecture is emerging that closes these gaps. Enter the Central Decisioning System (CDS): a unified, intelligence-driven ecosystem that brings together people, data, and AI agents into one continuous decision loop.

Dashboards were once revolutionary, but today they are static, fragmented, and slow. They show what happened and where trends point, but they do not help users interpret patterns, weigh trade-offs, or decide what to do next. Leaders often bounce between multiple dashboards for finance, marketing, sales, and product, each one telling part of the story. KPI definitions differ across tools, the timing of refresh cycles is inconsistent, and visualisations depend heavily on manual configuration. The result is a set of partial truths that still require analysts to stitch together insights.

Organisations that rely exclusively on dashboards find themselves conducting long review meetings, reconciling numbers, and revalidating findings instead of acting. That level of friction becomes a structural limitation. This is why the future is not better, or fancier, dashboard solutions, but an entirely new decisioning architecture.

A CDS is a unified, always-on intelligence layer that connects all data sources, human inputs, and AI agents to make and distribute consistent, data-backed decisions across the organisation. With CDS, instead of piecing together insights manually, teams interact with a system that already understands relationships between entities, past decisions, business rules, and expected outcomes.

Core capabilities of a CDS would include:

● Seamle ss integration across systems such as emails, documents, Slack, and CRMs

● Semantic understanding of business concepts and relationships, creating a family tree of insights

● Automated triggers that connect data, people, and actions in real time

● A s elf-refreshing repository of organisational intelligence accessible to all. It would function like Yahoo Finance for your entire organisation: live, contextual, and endlessly queryable.

A new architecture is emerging [...]. Enter the Central Decisioning System (CDS): a unified, intelligencedriven ecosystem that brings together people, data, and AI agents into one continuous decison loop.

Enterprises today juggle too many systems with too little coherence, with dashboards often reflecting fragmented truth, making the idea of a single source of truth difficult to achieve.

Deep-dive analyses by specialists take weeks instead of minutes, and insight generation depends on a few analysts, creating bottlenecks that slow everyone else. When a question requires pulling data from multiple systems and validating definitions across teams, the time needed to arrive at a decision grows significantly. Analysts become gatekeepers, not by choice but by necessity, and those bottlenecks slow down the entire organisation. The result is delayed and inconsistent decision-making that erodes agility and trust.

A CDS removes all this friction by aligning data, logic, and analysis in one place. Instead of static reports, decision-makers receive validated, context-rich intelligence in minutes. This reduces variability in how decisions are made and increases confidence in the insights

teams rely on each day. In any market, this consistency becomes a structural advantage.

A CDS raises the baseline of decision quality across the company. Every employee, regardless of tenure, can understand business dynamics through patterns learned by the system. Recommendations become more consistent because they are generated from unified logic rather than individual interpretation. AIdriven actions reduce manual work, especially in areas where rules are already known.

The shift in team roles is significant.

Analysts transition from creating reports to designing analytical models and validating decision logic. Data engineers and data scientists focus on architecture and modelling that support scalable automation rather than one-off solutions. Their expertise shapes the intelligence layer that informs daily decisions. On the other hand, with CDS in place, a sales representative starts the day with a call list already ranked by

conversion likelihood. HR receives early indications of rising attrition risk before it becomes visible in traditional metrics. Finance is notified the moment an unexpected pattern appears in transaction data.

Each of these instances, and the decisions they involve, would previously have required manual investigation. A CDS, however, makes all of them not just data-driven, but also decision-driven, and ultimately, business-outcome-driven.

The path to a Central Decisioning System begins with the rise of AI analysts and agentic AI. These systems shift organisations away from static dashboards toward a model where users can engage directly with data through natural language. Instead of searching across multiple tools, teams can ask questions conversationally and receive precise, context-aware answers grounded in validated logic.

AI analysts bring a semantic understanding of business concepts that traditional analytics platforms

cannot provide. They recognise entities such as customers, products, regions, and channels, and they understand how these elements relate to each other across different datasets. This creates a shared vocabulary between humans and systems, which is essential for a CDS because it ensures that every query, recommendation, and action is grounded in consistent meaning. Agentic AI extends this capability by interpreting intent, identifying the underlying decision a user is trying to make, and assembling the required analysis automatically. It performs multi-step reasoning, retrieves information across systems, evaluates conditions, and suggests next actions. This is the early form of the decision automation that a CDS requires.

As AI analysts and agentic systems integrate more deeply into an organisation’s operational environment, they begin to connect analytics with real-time triggers, workflows, and data streams. Over time, these capabilities evolve into the unified intelligence layer that defines a CDS. The shift is gradual but significant: from isolated reports to an interactive intelligence environment that continuously interprets what the business needs and delivers actions rather than static outputs.

AI analysts and agentic AI are not the final stage, but they form the essential bridge that enables organisations to move toward a fully centralised, always-on decisioning system.

The potential risks of a CDS are also real, of course. It could become an opaque black box, and AI-generated insights could carry embedded

biases. To counter this, feedback loops should be built so human judgment continues to refine AI logic. Automation must be balanced with accountability to preserve trust in the system’s recommendations. Any system that concentrates decision logic must be designed with transparency.

A CDS should never operate as an opaque environment. To prevent this, explainability must remain a design principle. Clear audit trails, traceable reasoning, and documented logic paths help organisations maintain accountability. Feedback mechanisms allow teams to correct, challenge, or refine the system’s conclusions. These safeguards will ensure that the system strengthens decision quality without removing human oversight.

The CDS will reshape how data teams operate, reducing manual analytics work and emphasising

architecture, modelling, and oversight. Decision-making will shift from episodic reviews to a continuous, adaptive flow of intelligence. The organisations that thrive will be those that think and act as one system, with decisioning intelligence woven into every layer of their operations.

The future of enterprise intelligence is not another visualisation tool but a thinking fabric that connects insight to action continuously and intelligently. Building toward a Central Decisioning System starts now, not later. For leaders, the imperative is clear: audit your decision architecture today. The question is no longer if dashboards will fade but whether your organisation is ready for what comes after.

The organisations that thrive will be those that think and act as one system, with decisioning intelligence woven into every layer of their operations.

NIKHIL SRINIDHI

NIKHIL SRINIDHI helps large organisations tackle complex business challenges by building high-performing teams focused on data, AI and technology. Before joining Rewire as a partner in 2024, Nikhil spent over six years at McKinsey and QuantumBlack, where he led holistic data and AI initiatives, particularly in the life sciences and healthcare sector.

How would you define data architecture and why should business leaders care?

In a small company, your daily conversations serve as the data architecture. The problem arises at scale. Once you have multiple teams, you need something that contains those agreements and design patterns, and you can't have 100 meetings a week explaining this to a whole organisation.

It's critically important because without it, everyone is building with different blueprints. Imagine constructing a building with each person using a different schematic. Connecting it to the origin of the word ‘architecture,’ it's really a way of ensuring everyone is working toward the same end goal. For data, it's about how you work with technology, different types of data, how you process it, and how you deal with structural and quality issues in a way that moves the needle forward.

I'd argue that architecture is key to scaling data and AI correctly. That's why organisations have been investing heavily in it. However, many haven't got everything they'd like out of it, so there's still an ROI question worth discussing.

Data architecture is really a way of ensuring everyone is working toward the same end goal.

What made data architecture a C-suite topic, and what role does AI play?

Twenty years ago, companies like IBM provided the full value chain from databases to ETL to visualisation. Over time, many companies began specialising in niche parts of the data value chain. Enterprises suddenly faced new questions as the importance of data grew: Which combination of technologies should I use? Where should I do what? Often you had data in one place and certain capabilities in another. Do you move the data? Do you move the capability?

Now with generative AI requiring vast amounts of unstructured information, you're thinking about knowledge architecture and information architecture. How do you ensure the right information feeds these models? The problem is growing fast.

Could you clarify the key layers of a modern data stack? I'd break it into two aspects. First is the static aspect, the data technology architecture: what tools, components, and vendors you use from ingestion through to consumption.

The second aspect is the dynamic part: data flows. How data moves from creation to consumption, with clarity about where processes should be standardised and where they can vary.

What's important is providing guidelines on how these patterns and technologies can be applied at scale. Successful data architecture becomes easily applied by the teams actually building things.

What principles should good modern data architecture have?

on these decisions so organisations walk into them consciously rather than falling into them. Whoever's building the architecture needs to be well-versed in the business strategy. When architecture becomes so generic you can switch the company name and it works for any industry, it probably won't work.

What are the biggest misconceptions about modern data architecture?

It depends on the industry, of course, but the biggest misconception I've encountered is that extreme abstraction will always make your architecture better. There's a tendency for architecture to become overly theoretical, but we need to ensure we make pragmatic trade-offs.

How do you make it pragmatic? There might be a specific part of the architecture, like your storage solution, where it's okay not to have all the flexibility through abstractions or modularity. You can double down on specific technologies and storage patterns. It's okay to commit to something. For example, if you want to store all your data as Iceberg tables or Parquet files, and that's a decision you've made for now, you can go with it. You don't have to build it in a way where you're always noncommittal about your decisions.

What's important is recognising where commitment benefits you and where it could become a cost.

The business or data strategy describes what to do with data. Why we need it, what businessobjective it helps achieve, what date represents ourcompetitiveadvantage. Architecture focuses on how.

Ironically, while architecture suggests permanence, data architecture needs modularity and flexibility. If there's a disruption in one component or an entirely new processing method emerges, you should be able to switch that component without breaking the entire system.

The human angle is often ignored. How do you encapsulate architecture as code and reusable modules that development teams can easily pull from a repository? The more practical and tangible you make it, the better.

Another quality is observability. You should be able to tell which parts of your data architecture are incurring the highest costs, which are growing fastest, and where leverage is reducing when it should be increasing.

How should data architecture align with business strategy, and where do you see disconnects?

The business or data strategy describes what to do with data. Why we need it, what business objective it helps achieve, what data represents our competitive advantage.

Architecture focuses on how. So, building things effectively and efficiently with optimal resources. It provides perspective on trade-offs. You can't have lower cost, higher quality, and speed simultaneously. Architecture should provide crystal clear clarity

For example, in life sciences R&D, you'd want to give consumers freedom to explore datasets in different ways. Diversity is fine there. But there's no point building the most perfect storage layer that tries to remain neutral. The misconception that architecture must be perfectly modular at every angle leads to unnecessary work.

How has GenAI influenced data architecture decisions in traditional business sectors?

GenAI has achieved visibility from the board to developers. The realisation is that without leveraging proprietary information, the benefit GenAI provides will be the same for any company.

The biggest challenge is providing the right endpoints for data to be accessed and injected into LLM prompts and workflows. How do you build the right context? How do you use existing data models with metadata to help GenAI understand your business better?

The broader question is, how do you handle unstructured data? Information in documents, PDFs, PowerPoint slides. How do you make this part of the knowledge architecture going forward? There's no clear approach yet.

How should organisations approach centralisation versus decentralisation?

I'll be controversial. While data mesh was an elegant

concept, the term created more confusion than good. It became about decentralisation versus centralisation, but the answer always depends.

For high-value data like customer touchpoints, you'd want standardisation. Centralisation may be fine. But ‘centralised’ triggers reactions because it means ‘bottleneck.’

Much advantage comes when data practitioners are deep in business context. If someone is working in the R&D space or clinical space, the closer they are to domain knowledge, the better, even if they have a background as a data engineer or data scientist. In these situations when something is centralised, requirements get thrown back and forth.

Focus on how you want data, knowledge, and expertise to flow. There's benefit to having expertise at the edge, but also to controlling variability. Both approaches should be examined without emotion.

What's your approach to separating signal from noise in the current data and AI landscape?

First, understand what types of data you have. A data map that's 70-80% correct is enough to start. ‘All models are wrong, but some are useful.’

Second, understand technologies and innovations in flux within each capability. Know the trends so you can identify leapfrog opportunities rather than doing a PoC for every capability.

Third, determine what is good enough. ‘Perfect is the enemy of good.’ Half the time, organisations pick solutions with a silver bullet mentality. Be honest, this works in 80% of cases, but here's the 20% that won't. Being aware of that de-hypes the signal.

To recap: know capabilities' connection to business value, understand market trends, and identify the extent capabilities need to be implemented, recognising you have limited resources.

What mindset and capability shifts do organisations need around data initiatives?

Working backwards, successful organisations have product teams that rapidly reuse design patterns and components to focus on problems requiring their expertise. Moving away from what we call pre-work to actual work.

Data scientists spend 70-80% of their time on data cleaning and prep. We want everyone to easily pull integration pattern codes, templates, and snippets without reinventing the wheel.

Individuals need to build with reusability in mind. If it takes 10 hours to build a module, it may take three more hours to build it in a more generalised fashion. Knowing when to invest that time is critical.

People building architecture need a customerfacing mindset. Think of other product teams as internal customers. This drives adoption and creates a flywheel effect.

How should organisations structure the data architecture capability?

The most successful architects have grown from

engineering implementation roles. They've built things, been involved in products, then broadened their focus from one product to multiple products. That's the most successful way of scaling the architectural mindset.

Even if architecture is a separate chapter, intentionally bring them together in product teams. Make the product team, where developers, architects, and business owners collaborate, the first level of identity an employee has.

If you ask an employee ‘what do you do?’ They should say ‘I'm part of product team X,’ not ‘I’m in the architecture chapter.’ This mindset shift requires investment. It's a people issue. It’s about ensuring there is trust between groups and recognising what architecture is at that product team level.

How should we measure the impact of data architecture? What's a smarter way to think about the value?

There's no clear-cut answer because data architecture is fundamentally enabling and it's difficult to directly attribute value. It's like a highway. Can you figure out what part of GDP comes from that highway? You can use proxies, but it's abstract.

The most important thing is almost forgetting ROI. Nobody questions whether a highway is important. Nobody questions the ROI of their IT laptop. We need to dream about a future where data architecture is similarly valued.

Ensure whatever you build connects to an initiative with a budget and specific business objective. You're not just building something hoping it will be used. Recognise that some capabilities individual product teams will never be incentivised to build and you need centralised teams with allocated budget for that.

Benchmark against alternatives: what would it cost teams to build this on their own using AWS or Azure accounts? Is there an economies of scale argument?

Measure proxy KPIs where possible because, ultimately, it's about the feeling of value. But also tell the story of what would happen without a central provider. What would it cost individual teams to do that on their own? That helps justify and track ROI.

Can you give some examples from regulated industries that illustrate the principles you have shared?

In life sciences R&D, data architecture is about bringing together different data types, including unstructured information and making it usable quickly. There's a big push in interoperability using standards like FHIR and HL7. If you're designing something internally, why not use these from the start rather than building adapters later?

Beyond the commercial space, there's also increasing effectiveness in filing for regulatory approval and generating evidence. There's tremendous value in ensuring you have the right audit trails for how data moves in the enterprise, especially as companies enter the softwareas-a-medical-device space. Knowing how information and data travels through various layers of processing is made possible through data architecture.

One of the biggest competitive advantages is becoming better at R&D. How do you take ideas to market? How do you balance a very academia-driven approach with a datadriven and technology-driven approach? This is where data architecture can be quite impactful.

Think about developing different types of solutions that require medical data to support patient-facing systems or clinical decision support systems. In all of these, it's highly critical to get it right in terms of how data flows, but also to ensure the data that's seen and used has a level of authenticity and trust.

The kinds of data we're working with vary from realworld data you can purchase – from healthcare providers, hospitals, especially EMRs and EHRs – to very structured types of information. How do you take that information, combine it, build the right models around it, and provide it in a way that different teams can use to drive innovation in drastically different spaces? Data architecture there is less about giving you an offensive advantage and more about reducing the resistance and friction to letting the entire research and development process flow through.

For example, how do you build the right integration patterns to interface with external data APIs? The datasets you're buying are probably made accessible via APIs you need to call, and you're often bound by contracts that require you to report how often these datasets are used. If you're using a specific dataset 30 times, it corresponds to a certain cost. However, if you're not able to report on that, the entire commercial model you can negotiate with data providers will change. They'll naturally have to charge more because they don't have a sense of how it's being used and will be more conservative in their estimates.

Being able to acquire data in different forms with the right types of APIs and record usage is a huge step forward.

Good data architecture is needed because across that architecture, you apply data observability principles. How is my data coming in? When is it coming in? How fresh is the information? How is it stored? How big is it? Who is consuming this information? What kind of projects do they belong to? How are they using it? Are they integrating these datasets directly into our products or tools?

Successful organisations go for leaner solutions with four to five integration patterns. They say: ‘This is how we get external data. If there's a way not covered by these, talk to the team.’ This level of control is required, because without it, tracing data and maintaining lineage becomes very difficult.

A lot of the value comes from acquisition in the pipeline. The second source of value comes from how data is consumed. What kind of tools can you provide an organisation to actually look at patient data? For example, with multimodal information, genomic information, medical history, diagnostic tests. How do you bring them all together to provide that realistic view? This is also an area where data architecture is very important because this goes much more into the actual data itself.

Also, what are the links between the information? How do you ensure you can link different points of data to one object? What kind of tools can you provide to the end user to explore this information? The classic example is combining a dataset and providing a table with filters, letting users filter on the master dataset. But recognising the kinds of questions your users would have also allows you to support those journeys. In these situations, successful companies have always taken a more tailored approach. Identifying personas and then building up that link between all these different types of data, especially in the R&D space.

Can you elaborate on the stakeholder challenges in life sciences?

Life sciences need diverse technologies and integration patterns, but technology and IT are still seen as a cost bucket. The more technologies you have, the more quickly data gets siloed.

Where to draw the line on variability in data architecture – especially in storage and data acquisition – is critical. This quickly balloons to a large IT bill. When you can't directly link value to it, organisations cut technology costs without realising the impact. It can dramatically affect capabilities in commercial excellence or drug discovery pipelines. We need to bring these two worlds closer together.

How does the diversity of life sciences data – such as omics, clinical trials and experimental data –affect architecture?

When you have such diverse multimodal data and dramatically different sizes, it's important to ensure you have good abstracted data APIs even for consumption within the company. If I'm consuming imaging information or clinical trial information, how do I also have the appropriate metadata around it that describes exactly what this data contains, what are its limitations, under what context was it collected, and under what context can it be used, depending on the agreement?

This kind of metadata is key if you want to automate data pipelines or bring about computational governance. This is a key capability when you're dealing with very sensitive healthcare information, and data is often collected with a very predefined purpose. For example, to research a specific disease or condition. Initially it might not be clear whether you can use that information to look at something else in the future.

These kinds of agreements that have been made in the past or haven't been made yet need to get to the granularity where the legal contracts you sign with institutions, individuals, and organisations about data use are somewhat translatable and depicted as code in a way that can automatically influence downstream pipelines where you actually have to implement and enforce that governance.

For example, if a dataset is only allowed to be used for a specific kind of R&D, it needs to show up at the data architecture level that only someone from a specific part of the organisation (because they're working on this project) can access this information during this period. The day the project ends, that access is revoked, and all this is done automatically. This isn't the case yet. It's still quite hybrid. This computational governance, because of the multimodality of the information combined with sensitivity, is the biggest problem many of these companies are trying to solve today.

Could GenAI help researchers navigate complex data catalogues with regulatory and compliance requirements?

I think GenAI has immense capability here because many of the issues are around how you process the right types of information in a very complex setting, recognising there are legal guidelines, ethical guidelines, and contractual guidelines you want to ensure work properly. It also interfaces from the legal space to the system space, where the information actually becomes bits and bytes.

Through a set of questions and a conversation, you can at least determine what kind of use this person is thinking about, what kind of modalities are involved, where those datasets actually sit, and which ones are bound by certain rules. This is where the ability to deploy agents can make sense because when you want to really provide this kind of guidance, it means you need clarity that's fed into the model as context that it can then base its analysis upon. Or if it's a RAG-like retrieval approach, you need to know exactly where to retrieve the guidance from.

The logic to evaluate is sometimes something that may need to be deterministically encoded somewhere for it to be used. That requires individuals to identify or create what I call labelled data for this kind of application. If this was the scenario, this was the data, this was the user, this is what they wanted and here's the kind of guidance the AI should provide. With that level of labelled information, you have a bit more certainty.

Organisations have vast amounts of unstructured data that could be vectorised and embedded to navigate it better, to increase utilisation. How do you see this evolving in the future?

Vector databases, chunking, indexing, and creating embeddings in multidimensional spaces is the first step. But architecture is still limited by how you ensure data sources can be accessed via APIs and programmatic calls and protocols. You still need that so all the different islands of information have a consistent, standardised way of interfacing with them.

This is the upgrade data architectures are currently going through, driven by use cases.

What's your one piece of advice for leaders responsible for data architecture?

Simplify and make data architecture accessible. Use simple English. Don't use jargon. Make it a topic that even business users want to understand. Just like Microsoft made everyone comfortable with typing or Excel, architecture needs to adopt that principle. It doesn't mean everyone needs to spend cognitive capacity on it, but it's helpful if everyone understands its place.

Just like Microsoft made everyone comfortable with typing or Excel, architecture needs to adopt that principle.

DR SAURABH STEIXNER-KUMAR is a data and AI leader with a rare blend of scientific depth and industry impact. At one of the largest financial institutions in the world, he drives global analytics and machine-learning initiatives end-to-end. From setup to model development to deployment, he excels at delivering scalable, business-critical solutions. Saurabh previously worked in luxury retail, leading data science projects spanning personalised recommendations and marketing attribution, integrating state-of-the-art algorithms with big data platforms. With a PhD from the Max Planck Institute and a research portfolio published in Science and Nature Scientific Reports , Saurabh brings deep expertise in decision science, leadership, and stakeholder management. His career across major players in finance, retail, aviation, and neuroscience empowers him to bridge cutting-edge research with real-world applications, making complex AI not just understandable but actionable for modern enterprises.

INTRODUCTION: THE INVISIBLE THREAT

Money laundering is a crime built on invisibility. Unlike a bank robbery or credit card scam, there is no single dramatic act, no obvious victim, no immediate loss. It is so subtle that without checks in place, it would remain hidden forever. Criminals don’t need to create new money but only make dirty money look clean. In the contemporary world, it has become even easier and even more dangerous.

Funds from drug trafficking, corruption, cybercrime, and human trafficking are fed into the legitimate financial systems before being layered through transfers, investments, and complex transactions. These transactions are designed to obscure their origins before finally reemerging as seemingly legitimate money. It is particularly difficult to detect because of the deliberate blending

of illegal funds with legitimate activity. A fraudulent transaction may be hidden among millions of routine ones, structured to appear perfectly ordinary.

Hiding in the Maze

Complexity is what drives the money laundering schemes. The systems designed for our modern society, like fast cross-border payments and diverse financial products, are the very mechanisms that criminals exploit. Shell companies offering various financial solutions over multiple jurisdictions make it harder to uncover the trail of money.

Cryptocurrencies have recently added another dimension to the difficulty. While digital assets promise transparency, they also enable newer money laundering schemes where the regulators and compliance teams often trail behind the criminals.

DR SAURABH STEIXNER-KUMAR

For many years, financial institutions have primarily relied on the rule-based transaction monitoring systems to spot suspicious behaviour. It is a relatively simple logic of using thresholds, which, when crossed, trigger an alert that then must be investigated by the investigation unit. This usually overwhelms the teams because of a very high number of false positives.

A money launderer may study such rules and intentionally exploit them to only transact below set thresholds. This is called smurfing, where the transactions look normal, but they are part of a bigger money laundering scheme. One must look beyond rigid systems and explore newer avenues.

Money laundering is not a victimless crime. Laundered money funds organised crime, sustains corrupt regimes, and enables terrorist financing. Every successful laundered scheme reinforces the underlying criminal activity, fuelling cycles of exploitation and violence. For financial institutions, the risks are equally severe. Failure to detect laundering exposes banks to regulatory fines, reputation damage, and potential exclusion from international markets. It’s a stark reminder that the stakes are not just moral but existential.

What makes laundering so elusive is its reliance on legitimacy itself. Unlike overt fraud, where criminals attack the system in obvious ways, laundering relies on the financial system’s everyday functions. It uses ordinary accounts, routine transactions, and lawful institutions as its camouflage. It’s challenging to preserve the speed and efficiency of global finance while ensuring it is not exploited for crime. Too much friction can stifle legitimate activity, while too little opens the door to abuse. Navigating this balance is one of the great challenges of modern compliance.

A Moving Target

Money laundering can be described as a crime without borders, and in today’s hyper-connected world, that description has never been more accurate. Illicit funds now move with the same speed and ease as legitimate funds, slipping through jurisdictions in seconds and disappearing into layers of opaque financial networks. What once required couriers with suitcases of cash can be achieved with a few keystrokes. The result is a global problem that seeps into nearly every corner of the economy, undermining governments, fuelling organised crime, distorting markets, and damaging trust in the global financial market.

If you’ve ever wondered why news headlines so often feature war, terrorism, and organised crime, it’s important to remember that none of these tragedies would be possible without money quietly moving through the global financial system. Behind every act of violence lies a trail of funds that often appear, at first glance, to be completely ordinary transactions. You might assume stopping this flow would be straightforward, but financial institutions face two immense challenges. First , detecting illicit funds is incredibly complex. Criminals constantly evolve their tactics, using sophisticated and ever-shifting methods to mask the origins of their money. Only advanced analytics and modern technology can keep pace with such professionalised networks. Second , banks must operate efficiently and competitively. They’re expected to balance strong anti-financial crime efforts with the realities of running a business, which naturally shapes the level of ambition they can commit to. Traditional monitoring systems have been the industry standard for years, even though their limitations are widely recognised. Transforming this landscape can feel like fighting on several fronts at once. But the potential impact is enormous. By shifting from a mindset of simply meeting requirements to one of embracing what is truly possible with today’s technology, we open the door to saving countless lives. That goal makes every step of progress not only worthwhile but essential.

Dr. Oliver Maspfuhl (Over two decades in the financial sector)

Money laundering is not static. As soon as one method is exposed, another emerges. We will be exposed to innovative money laundering schemes of the future. The constant evolution ensures that detection efforts can never stand still. The demand is to see beyond the obvious patterns. Traditional methods have laid the foundation, but they are no longer enough. We need to embrace new technology to help us in this fight against money laundering. We need to ensure that the financial systems can be fully trusted by society and that they remain a tool for growth.

Shell companies are a cornerstone of money laundering networks. Easy to establish and often registered in tax havens, these paper entities typically have no employees, offices, or genuine operations. Their sole function is to obscure ownership and control of funds. By layering transactions across multiple shell companies in different jurisdictions, launderers create a trail so convoluted it can take years for investigators to follow. Some countries have introduced beneficial ownership registries to bring transparency, but enforcement is inconsistent, and

DR SAURABH STEIXNER-KUMAR

secrecy continues to be a selling point in many of these financial hubs.

The digital age has only widened the playing field. Online gambling platforms allow criminals to deposit illicit funds, place minimal bets, and withdraw the balance as clean money. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based assets present an even more complex challenge. While blockchains are transparent in theory, the pseudonymous nature of digital wallets, combined with mixing services and decentralised exchanges, can make tracing transactions extremely difficult. Regulators face a delicate balancing act of encouraging financial innovation without losing control.

The stakes extend far beyond financial misconduct. Laundered money doesn’t just shelter the profits of drug cartels and corrupt officials, but it also fuels human trafficking and terrorism. Traffickers use intricate financial networks to mask the funds earned from exploiting vulnerable people, routing money through informal transfer systems, cash-heavy businesses, and global banks. Terrorist groups, meanwhile, depend on laundering to fund operations, purchase weapons, and recruit followers, often hiding flows behind charities or digital currencies. In both cases, laundering provides the lifeblood that sustains industries of exploitation and violence.

What makes money laundering particularly difficult to combat is the way it adapts to every attempt at enforcement. Stricter banking regulations in one region often push illicit flows to less-regulated markets elsewhere. This means that money laundering does not disappear but merely shifts shape and location. Furthermore, the integration of the global financial system means that weaknesses in one jurisdiction can have a snowball effect worldwide.

Governments and institutions are fighting back. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has set international standards on anti-money laundering (AML), urging countries to harmonise their rules and cooperate more closely. Banks and regulators are increasingly deploying

artificial intelligence and advanced analytics to detect unusual patterns hidden in transactions. But criminals are agile, often moving faster than regulators can respond. Ultimately, tackling money laundering requires a combination of global coordination, technological innovation, and political will. Transparency in ownership structures, stronger cross-border cooperation, and accountability in both public and private sectors are essential. Money laundering may be a crime without borders, but that does not mean it is unstoppable.

The most traditional and trusted way of detecting money laundering in banks and financial institutions is the rule-based monitoring methods. These are the basic tools that are straightforward, transparent, and loved by the compliance departments. There is a very good reason that these methods exist, as these are simple to implement and at the same time easy to explain. There is a clear set of thresholds and scores that define the reasoning behind any suspected transaction. Some examples could be large cash deposits, transfers to high-risk areas, or an unusually high number of transactions.

Simplicity, although it is a sought-after trait, because it means that the regulators are at peace, also results in complacency. If banks want to be ahead of the criminals, they need to be flexible in their approach. They have to look beyond the simplified assumptions of rule-based systems and evolve. They need to move quickly before the criminals can find newer ways to evade the police. A smart criminal may use certain unknown patterns to move money before new rules can be set up to detect it. It’s a hide-andseek game, where the seeker is only looking in places where the hider was found before, unaware of the evolution of the playing field.

There is also the burden of maintaining a large team of investigators with the traditional approaches, because

these methods generate an extremely large number of false positives. This is well understood by the example of a legitimate customer who has had a new business client and therefore suddenly deals with a larger number of transactions or transactions in foreign currency. Or another legitimate customer who has had a major change in lifestyle due to marriage or having children, and suddenly has a different transaction pattern. In both these examples, the customers may be flagged, and investigators will have to use their already limited time to file and close these legitimate cases. Such a system is not only inefficient but also introduces fatigue, where the investigators become desensitised and overlook potentially genuine cases.

It is a well-known fact that a vast number of alerts generated by the rule-based systems are false positives; however, a manual investigation into these is what keeps the financial system running with well-known caveats. This is still by far the most standard way around the world, which, although draining financially and on the individuals, is accepted by the regulators. The once-advanced system is showing its age due to the changing environment. We have several new advanced financial offerings in the form of new digital platforms and cryptocurrency exchanges, which generate activities that are too subtle and too complex for the rule-based methods to detect.

The transaction monitoring field is also evolving thanks to recent technological developments. There is more research in dynamic and intelligence-driven tools like machine learning and artificial intelligence. There are smarter and more efficient ways that are in use and in development to detect suspicious behaviour of criminals. It should be seen as a necessary and natural evolution of the blunt tools from the past to the newer and sharper tools of the present and future. In retrospect, the rule-based systems form an essential starting and base point from which we build the solutions of the future to assist the fight against money laundering.

The rise of AI (artificial intelligence) and data science may be seen as a new phenomenon, but the field has existed for a long time and has been hiding in plain sight behind the more traditional concepts of psychology, statistics, and computer science. Slowly but steadily, it is reshaping the landscape of transaction monitoring, not only from the technological point of view, but also from a philosophical one. We are no longer simply looking at some definitions from the textbooks, but rather exploring hidden patterns. We are looking at recognising the context, intent, and other sophisticated reasoning that may point to criminal behaviour.

At the core of the new generation of money laundering detection are several key techniques that are transforming the financial industry.

Anomaly detection can be considered as the very basic kind of monitoring within the AI-driven tools. I like to compare

it with the concept of personalisation, where a certain routine behaviour of a customer is considered normal, and anything that is out of the ordinary of this personalised bubble is a cause of concern.

Conceptually, every customer forms a unique profile, and this is constantly adapting to the change in behaviour within a certain limit. The power of this method lies in its adaptability, as it is capable of understanding the subtle signs of a shift in behaviour. The goal is not to remove the false negatives but rather to reduce the noise significantly and allow the investigators to put effort into more meaningful alerts.

Predictive Analytics:

Anticipating Risk

Predictive analytics is a different way of looking at the problem. Where the traditional way of detecting money laundering is to detect it within the transaction behaviour after it has already taken place, predictive analytics tries to identify it before it occurs. I like to think of the movie Minority Report , where the idea is to look for signs and make a conclusive prediction of crime and potentially stop it.

Looking at the historical patterns of transactions and other metadata like demographic information and general behaviour, certain AI models can identify some signs of risk. Taking the movie example, if a person who has never held a gun is lifting and pointing a gun towards someone with anger on his face and a potential motive, it is safe to predict that he might shoot. Such a sign should be alerted for investigation.

Such predictions can not only help in identifying crime but also support the resource allocation that can then be based on the risk profiles. Prioritisation and categorisation of the investigations can be the difference between catching the criminal and letting him slip through the mountain of false alerts.

Entities involved in money laundering do not just use one instrument within one institution, but a large and complicated network to hide the trails. This may involve using differently spelled names and multiple accounts and transaction routes, to name a few that are hard to link together. Entity resolution aims to link all the fragmented pieces together to form a complete picture so that they can judge the transactions.

The technique can involve using linking and mapping tools to view the network of entities and unravel the broader behavioural pattern. Such a sophisticated mechanism is only possible with the AI-driven approach and could not be captured with the static rulebased algorithms.

Transaction monitoring has moved far beyond simple transfers of amounts in numbers. It also exists within the

DR SAURABH STEIXNER-KUMAR

subtle descriptions that form these transactions. There can also be unstructured forms of information from media and public activities. Human language is a complex thing to comprehend for computers, and the modern tools are now able to look deeper into these messages where the previous approaches could not.

Natural language processing is able to demystify the messages that follow transactions and may be able to generate alerts based on risk. Not only that, but the procedures of knowing the customer and regular screenings are also boosted with these new techniques and play their part in fighting money laundering.

It is crucial to note that the advancement in technology should be seen as a new development in sharpening the tools that we have at our disposal to fight money laundering. The objective of using new technology is not to replace humans or their expert judgment in detecting wrongdoing, but rather to make them better equipped to do the job more reliably and efficiently than ever before.