A DECADE OF YOUNG ARTISTS

MIAMI ART WEEK EDITION

BAL HARBOUR SHOPS, 9700 COLLINS AVENUE MIAMI

Find Your Beachfront Home in the Sky

On a pristine stretch of coveted oceanfront, this limited collection of light-filled homes in the sky, designed by the visionaries Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), Ro et Studio, and Enea Garden Design, features stunning vistas in every direction.

NOW UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Three- to six-bedroom residences priced from $13 Million. Schedule a private preview at our Sales Lounge in Bal Harbour Shops. RivageBalHarbour.com 786.572.3441

FOUNDER

Sarah G. Harrelson

EXECUTIVE

Mara Veitch

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Julia Halperin

CO-CHIEF

Johanna Fateman & John Vincler

SENIOR

Ella Martin-Gachot

ASSOCIATE

Sophie Lee

ASSISTANT

Sam Falb

ART

Everything

CHIEF

Carl Kiesel

VICE

Lori Warriner

DIRECTOR

Ian Malone

VICE

Michael Riggio

PUBLIC

Ethan Elkins

Dada Goldberg

MARKETING AND

ASSOCIATE

Hailey Powers

DIGITAL AND

COORDINATOR

Paloma Baygual Nespatti

PREPRESS/PRINT

PRODUCTION

Pete Jacaty & Associates

The art world is rarely without something to say about the evolution of Miami—especially on the eve of Art Basel Miami Beach.

In this issue, writer Janelle Zara talks to gallerists weighing the feasibility of making the journey to Miami on a shoestring budget. Meanwhile, the Bunker Artspace’s Maynard Monrow and Laura Dvorkin reveal how they staged a major show of LGBTQ+ work just 15 minutes from Mar-a-Lago. As calendars fill with an insurmountable number of commitments, figures including Casey Fremont and Alex Israel weigh in on the messy business of navigating gallery dinners while dodging less-than-gracious diners and braving the open bar. We also offer our guide to the best shows, satellite fairs, and other happenings across the city.

In these pages, you’ll also find our 10th Young Artists list, a roundup of 27 rising talents to look out for in Miami and beyond. For the second year in a row, we’ve partnered with MZ Wallace to offer the MZ Wallace and CULTURED Young Artists Prize, continuing our commitment to providing one artist from our annual list with the material aid so necessary to making the work that inspires us. We also gathered more than two dozen alums from the list to mark its 10 -year anniversary. In these pages, they reflect on how their careers have evolved since we first met them and speak candidly about the biggest challenges—and proudest moments—they’ve experienced along the way.

See you at the fairs.

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief

YOUR GUIDE TO MIAMI GALLERIES AND MUSEUMS THIS WEEK

FROM UP-AND-COMING GALLERIES TO MAMMOTH PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS, CONSIDER THIS YOUR WELL-ROUNDED ART DIET.

“LANDSCAPES”

BY STUDIO LENCA

Where: David Castillo Gallery

When: Through Jan. 31

Why It’s Worth a Look: The artist’s first solo show in Miami brings together his vibrant paintings of “Historiantes,” figures in his native El Salvador who re-enact oral histories of colonization.

Know Before You Go: Studio Lenca, who lives in Margate and works out of Tracey Emin’s TKE Studios, has work on view concurrently at the Rubell Museum in Miami and MoMA PS1 in New York.

“THAT WAS THEN, THIS IS NOW”

Where: 119 NE 41st Street, Miami

Design District

When: Dec. 2–Jan. 2

Why It’s Worth a Look: For Jeffrey Deitch, a booth at Art Basel Miami Beach isn’t enough. He’s spreading out with a pop-up exhibition featuring a range of buzzy artists including Leyla Faye, Hannah Taurins, and more.

Know Before You Go: Deitch has organized high-gloss exhibitions in Miami for years, sometimes in partnership with Larry Gagosian. This year, he’s going solo.

“DISORDER” BY

ANETA GRZESZYKOWSKA

Where: Voloshyn Gallery

When: Through Jan. 10

Why It’s Worth a Look: The Polish artist, born in 1974, makes the kind of work about familial dynamics with which psychoanalysts would have a field day. This show is no different.

Know Before You Go: The centerpiece is a new body of work, THE DAUGHTER, 2025, which captures the artist in staged tableaux with relatives wearing a hyperrealistic mask based on her own face when she was 14.

Where: The Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

When: Dec. 2–Mar. 29

Why It’s Worth a Look: This is the first posthumous survey of the Chicago-born abstract sculptor, who died in 2023. It charts his evolution across 25 works made between the 1950s to the 1990s.

Know Before You Go: What you’ll see in the museum is just a small slice of Hunt’s output. He also created more than 150 public art commissions, many of which are engaged with themes of social justice.

“COMING FORTH BY DAY” BY WOODY DE

OTHELLO

Where: Pérez Art Museum Miami

When: Through June 28

Why It’s Worth a Look: The Miami native is best known for hand-built ceramics that transform everyday objects—clocks, telephones, mirrors— into anthropomorphic, spirited figures. For his first hometown museum solo, he will present new ceramics, wood sculptures, and a large bronze.

Know Before You Go: This show is one you can smell as well as see. The installation includes clay-painted walls and herbal scents.

“BLUE MAGICK” BY SHAYLA

MARSHALL

Where: Walgreens storefront, 23rd Street and Collins Avenue When: Ongoing

Why It’s Worth a Look: Inside one of the most highly-trafficked Walgreens in Miami Beach, Shayla Marshall has created two scenes: one of a mother tending to her daughter’s hair and another of a drugstore aisle stacked with braiding hair products and combs.

Know Before You Go: The artist says that the presentation—organized by the Bass and the Bakehouse Art Complex—reflects her journey from “absence to visibility” as safe products for Black hair became easier to find.

“RICHARD HUNT: PRESSURE”

Studio Lenca , Paisaje 2025. Photography courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery.

Richard Hunt, Low Flight , 1998. Photography by Frankie Tyska and courtesy of White Cube.

Woody De Othello, Ibeji, 2022. Photography by Eric Ruby, courtesy of the artist, Jessica Silverman, and Karma.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, MAMA nr. 32 2025. Photography courtesy of the artist and Voloshyn Gallery.

“NOX PAVILION” BY

LAWRENCE LEK

Where: The Bass

When: Through April 26

Why It’s Worth a Look: The show brings viewers inside a fictional therapy center called Nox (short for “Nonhuman Excellence”), where sentient self-driving cars undergo psychological treatment.

Know Before You Go: The Londonbased artist has explored the Nox universe in his work since 2023; this presentation includes a two-channel film, an interactive video game, and more.

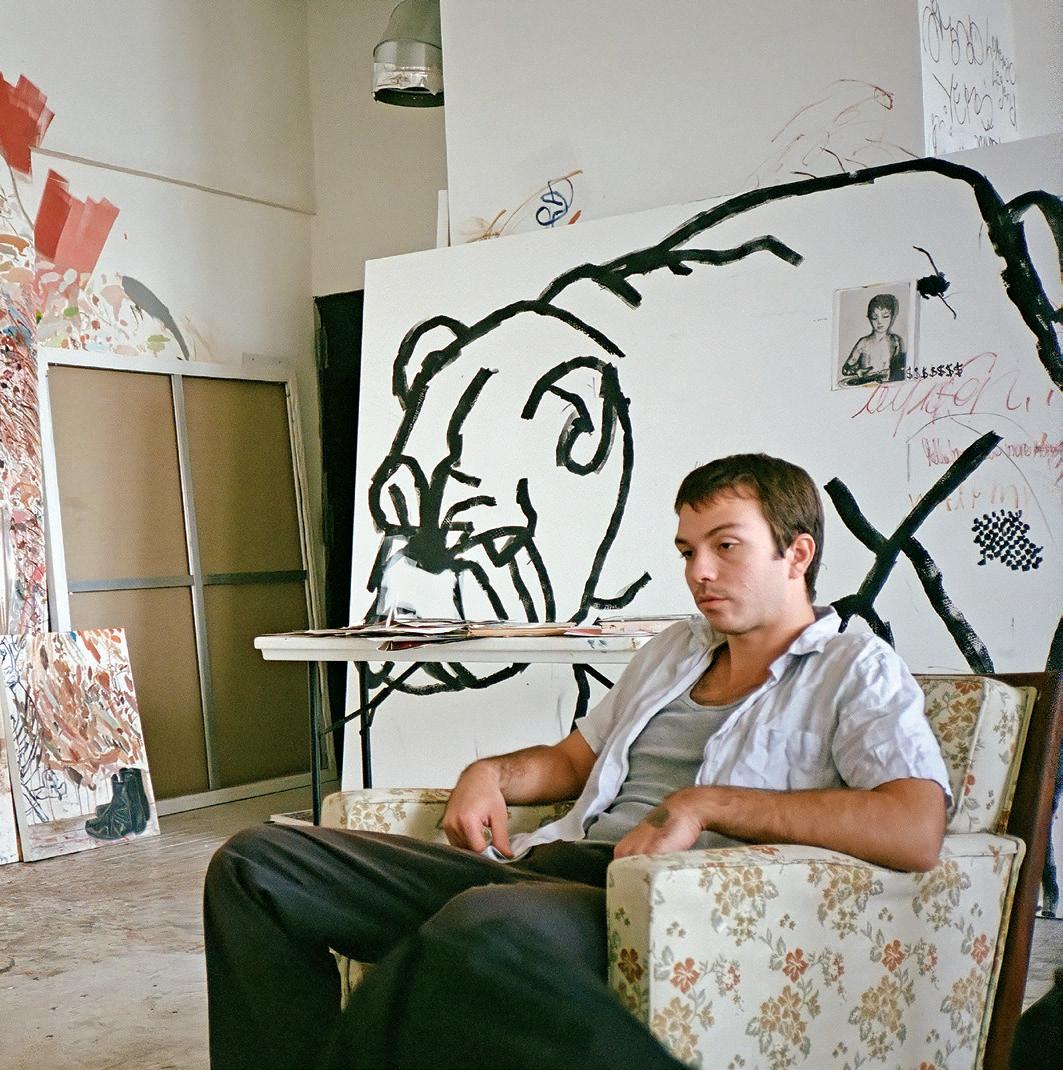

“FIRST

LIGHT” BY

THOMAS HOUSEAGO

Where: Rubell Museum

When: Dec. 1–Sep. 27

Why It’s Worth a Look: The first single-artist survey to take place at the expanded Rubell Museum presents more than 20 sculptures and collaged paintings by the Los Angeles-based art world bad boy-made-good Thomas Houseago.

Know Before You Go: The private museum will also present solo presentations by emerging stars including Yu Nishimura, 2025 CULTURED Young Artist Lorenzo Amos, and Young Artist alum Ser Serpas.

“CHANGES: REFLECTIONS ON TIME & SPACES”

Where: Spinello Projects

When: Dec. 1–Jan. 10

Why It’s Worth a Look: To mark the Miami gallery’s 20th anniversary, founder Anthony Spinello is bringing together work by 15 artists with ties to the gallery, including Agustina Woodgate and Eddie Arroyo.

Know Before You Go: Making the presentation all the more personal, the works in the show are all drawn from Spinello’s private collection.

“INDIGENOUS

FUTURISM”

BY CECILIA VÁSQUEZ YUI

Where: Mindy Solomon Gallery

When: Through Jan. 10

Why It’s Worth a Look: Inspired by the concept of Indigenous Futurism, Cecilia Vásquez Yui, a member of the Shipibo-Conibo tribe, creates ceramic sculptures that recall technological objects sent from a future era into the rainforest of the present.

Know Before You Go: With a population of more than 20,000, the Shipibo-Conibo people are one of the largest Indigenous groups of the Peruvian Amazon.

“A WORLD FAR AWAY, NEARBY AND INVISIBLE: TERRITORY NARRATIVES IN THE JORGE M. PÉREZ COLLECTION”

Where: El Espacio 23

When: Through Aug. 15

Why It’s Worth a Look: The show at the private contemporary art space founded by Jorge M. Pérez takes a broad look at how territory shapes identity, memory, and belonging through nearly 150 works by more than 100 international artists.

Know Before You Go: Curated by Claudia Segura Campins, Head of Collection at Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, the exhibition places the work of local Miami artists like Nina Surel and Jennifer Basile alongside such famous names as Chris Ofili and Pat Steir.

“UNDERWATER AND UNDERNEATH” BY LAURIE SIMMONS

Where: Andrew Reed Gallery

When: Through Jan. 17

Why It’s Worth a Look: For the beloved photographer’s second show with the Miami gallery, Simmons is presenting works from three series that span the early 1980s to the late ’90s.

Know Before You Go: In the series “Water Ballet” and “Family Collision,” human forms and toy figurines float underwater. The third series, “Underneath,” features surreal images of mannequins framing unsettling domestic scenes.

“THE BEST SHOW DURING MIAMI”

BY SUSAN KIM ALVAREZ

Where: KDR

When: Through Jan. 10

Why It’s Worth a Look: Aside from the fact that the show has perhaps the best title of any exhibition on view during Miami Art Week, it boasts dense paintings teeming with animals, cartoon figures, and plant life.

Know Before You Go: The Miamibased artist draws from her Cuban, Vietnamese, and Jewish heritage to create dreamscapes that sometimes include her relatives as she imagines they looked when they were younger.

Cecilia Vásquez Yui, White Tiger, 2020. Photography courtesy of the artist, Mindy Solomon Gallery, and the Shipibo Conibo Center.

Thomas Houseago, Stage 3 - Mirror in Studio - living with not in 2023. Photography by Chi Lam, courtesy of the artist and Rubell Museum.

Susan Kim Alvarez, Mouth of Miami 2025. Photography courtesy of the artist and KDR.

Violeta Maya, Mi versión del origen del mundo I-III, 2024. Photography courtesy of the artist and El Espacio 23.

Lawrence Lek, NOX (Film Still), 2023. Photography courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ.

If You See Nothing Else at Design Miami…

The 2025 edition of the revered design fair, which celebrates its 20 th anniversary this year, ushers in a cadre of gallerists and artists reviving esoteric processes, paying tribute to American design forebears, and manipulating known materials into foreign forms. These six booths are not to be missed among the wealth of offerings on view.

BY LEE CARTER

Marking 20 years as the leading design fair, the increasingly international Design Miami opens its doors in its hometown this week. Under the curatorial leadership of Glenn Adamson, the 2025 edition’s theme is “ Make. Believe .”—a rallying cry for imagination and ingenuity. “We’re creating a conversation about skilled craft and unfettered imagination,” he notes, “and the way those two things continually inform each other.”

The fair, which runs from Dec. 2 -7, once again transforms Pride Park on Miami Beach into a whirlwind of collectors, gallerists, curators, and design cognoscenti, not to mention the curious art crowd that never fails to drift over from Art Basel Miami Beach at the Convention Center next door.

This year’s edition of the fair will play host to over 70 galleries—including 25 first-time exhibitors—who have taken the theme to heart. Together, the designers and dealers participating in the 2025 program lean heavily into material exploration, from Rich Aybar’s compact rubber armchair, modeled on the gooey tactility of a slug, on view with Milan’s Delvis (Un)Limited, to Jack Craig’s sculptural manipulations of synthetic carpeting for Detroit’s David Klein Gallery. Narrative, too, comes to the fore: London’s Charles Burnand Gallery presents intricate yet monumental works with enough backstory to fill a book. Several exhibitors tip their hats to visionary forebears, as with Moderne Gallery’s focus on the pioneering woodwork of George Nakashima and Superhouse’s tribute to the radical furniture artists of the 1980 s. Given the range of perspectives on view, CULTURED has selected six presentations that embody Design Miami’s dream-big ethos this year, each one imaginative and ambitious in its own way.

Delvis (Un)limited

A champion of Italian craftsmanship, the experimental Milanese art-meets-design space has earned a reputation for spotlighting fresh young practitioners. Its booth offers an eye-popping mix: Rich Aybar’s rubber Slug Chair marries whimsy with high concept, while Objects of Common Interest unveils a rock-like, shock-pink resin creation that pops open to reveal a hidden bar and speaker system inside.

Adrian Sassoon

Devoted to ceramics, hardstone, and glass, the London gallery promises to dazzle Design Miami visitors with its explorations in contemporary craft. Highlights include jagged, geology-inspired vases by Kate Malone and luminous cast-blown glass works by Joon Yong Kim, the Seoul-based designer renowned for his poetic oscillations between transparency and opacity.

Wexler Gallery

Philadelphia’s Wexler Gallery’s booth features a compelling lineup of newly represented designers. Among them is German artist Henry Baumann, whose globular towers of translucent resin evoke amoebic, primordial ooze—playful, biomorphic, and mysterious. Mining an altogether different vein is the British designer Sofia Karakatsanis, who is debuting a series of hand-carved wooden chairs. Known for her intuitive process and reverence for raw materials, Karakatsanis lets the wood’s grain dictate each piece’s form, transforming raw timber into oneof-a-kind sculptural furniture.

Friedman Benda

A Design Miami stalwart, Friedman Benda gallery returns with a characteristically idiosyncratic presentation featuring architectural designer Javier Senosiain, ceramic artist Nicole Cherubini, and Fernando Laposse, the young Mexican talent known for transforming unconventional materials such as corn husks and agave fibers into yeti-like “monster” lamps, among others. The buzzy outfit—with locations in New York and Los Angeles—will also debut The Lost Cloth Object, a joint effort between Stephen Burks and Italian wood manufacturer ALPI. This collaboration sees the American designer and Columbia professor of architecture juxtapose motifs from the textile traditions of the Kuba Kingdom of Central Africa— particularly the bold, geometric patterning of embroidered Kuba cloth— with the color, grain, and texture of endangered woods.

Superhouse

The New York gallery was founded in 2020 with the mission of giving trailblazing yet overlooked American furniture designers from the late-20 th century their flowers. This involves taking a fresh look at the audacious 1980 s when, as founder and director Stephen Markos puts it, “American designers started to treat furniture as art—deeply personal, political, and full of attitude.” This year, Superhouse presents landmark pieces by 12 of the era’s most impactful designers, many of which have never before been shown to the public. Standouts include Dan Friedman’s exuberant folding screen, as riotous as it is playful, and Alex Locadia’s molded-leather Batman Chair of 1989 , of which only two were produced.

Charles Burnand Gallery

The London institution brings a spiritual edge to the fair this year with a look beyond function and form and toward the mystical and monumental. New works by designers including Marc Fish, DEGLAN, Fabrikr, Kyeok Kim, and Studio Furthermore delve into esoteric processes and materials—from charred iroko wood to color-shifting dichroism and the stacking of opaque hanji paper. At the center of it all is Jan Waterston’s Strata Cabinet—the British designer coaxed solid ash into a sinuous, monolithic presence that feels both ethereal and grounded.

Rich Aybar, Slug Chair 2025, for Delvis (Un)limited Gallery. Photography courtesy of Piercarlo Quecchia.

Fernando Laposse, Patachin, 2024. Photography courtesy of Friedman Benda.

Jan Waterston, Strata Cabinet , 2025. Photography by Graham Pearson and courtesy of Charles Burnand Gallery.

Sofia Karakatsanis, Resilience , 2023. Photography courtesy of Wexler Gallery.

Dan Friedman, LM Screen 1982. Photography courtesy of Superhouse.

Kate Malone, Mega Magma , 2025. Photography courtesy of Adrian Sassoon.

THE MIDSIZE DEALER’S GUIDE TO MIAMI ON A BUDGET

WHILE THE MEGAGALLERIES RENT OUT CARBONE AND SHACK UP AT THE EDITION, SMALL AND MIDSIZE GALLERIES GET THRIFTY TO SURVIVE ONE OF THE BIGGEST WEEKS IN THE ARTWORLD CALENDAR.

BY JANELLE ZARA

The art world’s annual retreat to Miami can look very glamorous—that is, “if you squint,” says New York gallerist Margot Samel. For every capacious Escalade pulling up to the Edition, there is an emerging dealer splitting an Uber to an Airbnb with a colleague. “Miami gets expensive fast,” Samel explains. “The quiet, unglamorous choices are the ones that save you.”

Samel, who will make her Art Basel Miami Beach debut this year with a solo presentation of Argentine painter Carolina Fusilier, is one of

many exhibitors who will be spending strategically in Miami. The mounting costs of shipping, booth fees, airfare, and hotels are challenging, especially on top of the year-round expenses of running a gallery during a challenging year for the art market. Jeffrey Lawson, founder of Untitled Art, told ARTnews that he had been shrinking the size of the fair’s booths to accommodate struggling gallerists’ budgets.

The consensus among young dealers is that fairs provide a level of exposure that wouldn’t be possible otherwise—which keeps them coming back, even if participation is a gamble.

“For a gallery like ours, especially in a slow market, the fair can feel like stepping onto Wheel of Fortune,” says NADA exhibitor Marina Vranopoulou, founder of the Athens, Greece, gallery Dio Horia. “You spin, you hope, and you try to land in the right spot.”

Making it through Miami Art Week on a shoestring is possible. It just requires preparation, fortitude, and foregoing certain luxuries. Ahead of the whirlwind, we gathered a few tips from the dealers who are making it work.

Above: Photography courtesy of Art Basel.

GETTING THERE

“We run on low-drama operations: no last-minute flights or hotels, no 11thhour framing,” says Samel, who started planning for Miami in June. “The trick is booking hotels before the ink on the acceptance letter is even dry.” Walking distance from the fair is ideal, she adds, for avoiding hellish traffic and expensive Ubers.

Artist Alex Nazari, founder of LA gallery Gattopardo, recommends flying into Fort Lauderdale, a less popular and therefore less expensive hub than Miami International. From there, she’ll drive off in the car she rented through

Costco for the low price of $250 a week, plus the $65 annual membership. This year, she is presenting a suite of paintings by Raffi Kalenderian at NADA (small enough to ship in a cardboard bin rather than a heavy wooden crate and easily carried home in the event they don’t sell).

And rather than compete in Miami with a million different events, she’s throwing Kalenderian a party in LA before the fairs begin. “So many people aren’t coming to Miami, and I’d love for them to see the work,” Nazari says.

A LITTLE HELP FROM YOUR FRIENDS DIY ART HANDLING

According to a recent Artnet report, add-ons at Art Basel can range from $128 to access an electrical outlet to as much as $800 for an additional light—all frills small gallerists have learned to do without. “We minimize absolutely everything,” says Vranopoulou, who even brings her own chairs from home, packed into the same crate as the art. Any works that don’t fit into the crate go into her suitcase. Once onsite, she’ll build out a conceptual, post-apocalyptic group presentation with her husband, Tom. (In true small-business fashion, family members double as cheap labor.)

Cole Solinger of the San Francisco gallery House of Seiko prefers not to outsource any work he can do himself. Tapping into skills he learned as an art handler, as well as in “remedial” woodshop at art school, he’s building the frames and slipcases for his group showing at NADA. Rather than flying out an extra salesperson or seeking one out in an unfamiliar town, he also plans to staff the booth himself for the entire fair. So will Nazari, whose preferred form of caffeine is Ito En bottled green tea. “It keeps you perky without the crash and coffee breath,” she notes.

Do-it-yourself doesn’t necessarily mean going it alone. Over the years, Samel has developed a circle of peers she can rely on for emotional support and other resources. “We share shipments, share staff, share Advil,” she says, and at other fairs in the past, they’ve shared Airbnbs. “Nothing bonds people faster than making pasta in a barely functional rental kitchen.”

Although it’s an arduous week, dealers say it’s worth going out in Miami at least once. “I let my friends who work at big galleries pay for dinner,” says one Miami exhibitor. Cutting out drinking and smoking also goes a long way. “I just don’t believe people are closing deals at 2 a.m. after four martinis anymore,” the exhibitor adds. “Get on an SSRI and get on with it.”

Photography by Ryan Whelan and courtesy of Cole Solinger.

Image courtesy of Margot Samel.

Raffi Kalenderian, Mac’s Club Deuce , 2025. Photography courtesy of Gattopardo.

The Collector’s Edit

This season, take a note from the late Peggy Guggenheim with a fair-week wardrobe that channels breezy abundance.

Any art-world veteran will tell you that an art fair is a fashion moment. Even when the sartorial choices are understated— gallery blacks, sleek suiting, endless cashmere—they never fail to telegraph a delicately attuned sense of status, par for the course in an ecosystem that is relentlessly self-aware.

It’s always refreshing to catch a flash of irreverent glamour weaving its way between gallery booths. Few figures have occupied the role of the art world’s sartorial north star better than Peggy Guggenheim, legendary heiress and inimitable patron of avant-garde artists including Wassily Kandinsky, Mark Rothko, and Jean Cocteau.

Guggenheim’s commitment to the experimental extended to her wardrobe—which, in her youth, featured no small number of cellophane-wrapped gowns (courtesy of her good friend Elsa Schiaparelli), and, in later years, gave way to piles of golden jewelry, mismatched earrings, and a notorious pair of saucer-sized sunglasses (commissioned from another friend, the artist Edward Melcarth). Whatever the collector wore, she wore it with ease— reclining, with a dog on each side, in her personal gondola as it glided through the Venetian canals.

Guggenheim’s spirit is alive and well in Miami this year, and ready to be channeled into bold looks that leave a strong impression on more restrained dressers. Classic silhouettes—A-line dresses, mercilessly cinched trench coats—accompany heavy gold accents—a cascade of diamonds, a formidable cocktail ring, a steep metallic heel (Level has the one you need)—and art-conscious statement pieces (a Dior Lady Art bag, naturally). The look, this season, is breezy abundance.

David Yurman Sculpted Cable Open Cocktail Ring in 18K yellow gold with black onyx and diamonds, $8,800

Prada embroidered sequin dress, $5,500

Schiaparelli Measuring Tape Sunglasses, $3,360

Van Cleef & Arpels Ludo Secret Watch featuring diamond, lapis lazuli, mother-of-pearl, and sapphire set in 18K yellow gold, Price upon request

Double C de Cartier lighter, yellow-gold finish metal, $1,340

Peggy Guggenheim wearing a Schiaparelli dress. Photography courtesy of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Amina Muaddi at Level Shoes Anok 105 slippers, $1,065

Burberry Car Coat, $3,150

Dior Lady Art limited edition in collaboration with Eva Jospin, Price upon request

Reza mismatched Nirvana and Atoll earrings with sapphires and diamonds, Price upon request

Clockwise from top right: Photography courtesy of Schiaparelli, Reza, Dior, Prada, David Yurman, Level Shoes, Burberry, Cartier, and Van Cleef & Arpels.

Your wealth. Your mission. Your investments.

Unpredictable times call for important conversations. At Glenmede, you receive sophisticated wealth and investment management solutions combined with the personalized service you deserve.

The Miami Social Calendar

From power panels to late-night invites, these are the Art Week moments that will define the season outside the Convention Center.

The Events

DECEMBER 1–4

Miami, WE ARE ONA Style

The collective arrives in Miami with an immersive culinary installation at the newly opened Andaz Miami Beach, conceived in collaboration with designer Sabine Marcelis, whose luminous material language sets the tone for a multi-sensory dining journey with the José Andrés Group. Andaz Miami Beach, 4041 Collins Avenue

DECEMBER 2–8

Galerie Estrada’s First Art Week

Etéreo, the vintage clothing concept by Zabrina Estrada, is expanding its Miami footprint with a gallery space. Its inaugural presentation, “Transcultural Salon: 1910–1930,” explores a moment when the East and West intersected, featuring pleated silks, hand-painted velvets, and brocades.

Galerie Estrada, 7636 NE 4th Court

DECEMBER 2

A Fireside Chat with ECOLOGIES

Moderated by CULTURED Editorat-Large Julia Halperin, this conversation brings together leaders from an array of institutions to discuss how we build and sustain creative communities. Panelists include NADA Executive Director Heather Hubbs, Knight Foundation VP for Arts Kristina Newman-Scott, and PAMM Director Franklin Sirmans.

Ice Palace Studios, 1400 N Miami Avenue

DECEMBER 3

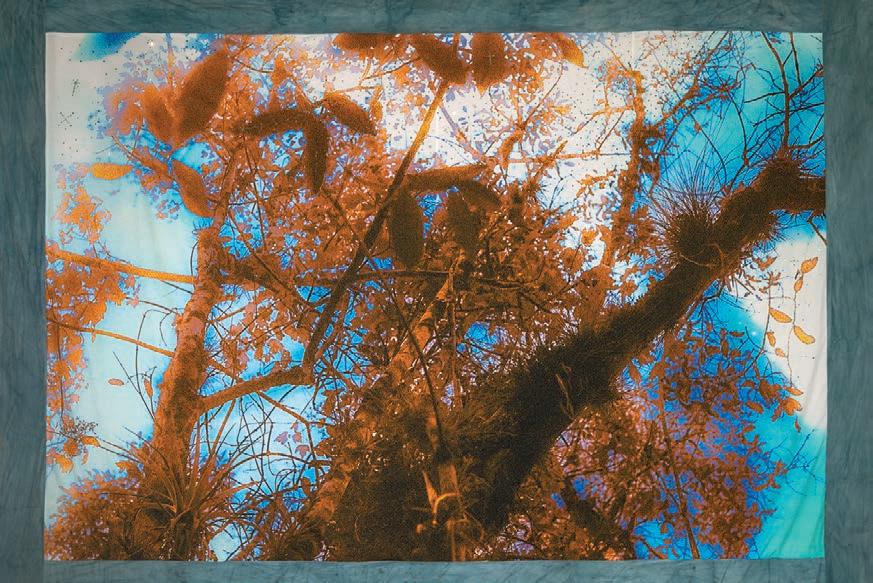

Champagne, With a Side of Sam Falls

Ruinart toasts its “Conversations with Nature” partnership with Sam Falls, hosting a cocktail that merges champagne ritual with the artist’s atmospheric, earth-driven sensibility. This is also the last chance to see Falls’s installations before they move permanently to the Maison Ruinart in France. Miami Beach Convention Center, 1901 Convention Center Drive

Marni’s Next Chapter Unlocked Marni extends the vision of its new creative director, Meryll Rogge, with

an art installation curated by the designer at the line’s Design District boutique. It’s a must-visit for those seeking the inside scoop on where the Italian house is headed next.

Marni Miami Design District, 173 NE 40th Street

The New York Literati’s Touch-Down

Nina Johnson hosts a toast to The Whitney Review’s latest issue and “Acid Bath House,” Jarrett Earnest’s deliriously fun group show at the gallery—complete with go-go dancers, spoken-word performances, and an ice sculpture emblematic of Miami’s flamboyant take on partying. Brother’s Keeper Bar, 1710 Alton Road

Sukeban Strikes Again

The legendary all-female Japanese wrestling league returns for a one-night Miami takeover, creative-directed by co-founder Olympia Le-Tan, with a cameo by drag queen Violet Chachki. Expect spectacle, sweat, and a rowdy crowd.

Miami Beach Bandshell, 7275 Collins Avenue

Miu Miu Hits Refresh

In a swirl of glass, velvet, and brushed metal, Miu Miu is reintroducing itself to the city just in time for Art Week. Featuring the latest Holiday 2025 collection, the line fêtes the launch of its newly redesigned boutique with an invite-only party (but don’t worry, the boutique doors will be open to the public as soon as the champagne is cleared).

Miu Miu Design District, 190 NE 39th Street

The Critics’ Table Heads to Miami What is the role of criticism today? How does it relate to the rest of the art world? CULTURED is staging a live edition of the Critics’ Table to parse these questions and more with Co-Chief Art Critic Johanna Fateman, alongside contributors Jarrett Earnest and Whitney Mallett.

Ice Palace Studios, 1400 N Miami Avenue

CULTURED Goes Tropical

Step out of the fair circuit and into the Jean-Georges Miami Tropic Residences for CULTURED’s panel featuring Editor-at-Large Julia Halperin, artist Marcel Dzama, Hanabi

art consultancy Founder Jamie Stagnitta, and the Residences’ architect Glenn Pushelberg. Jean-Georges Miami Tropic Residences, 3501 NE 1st Avenue

Manolo Blahnik and Achille Salvagni’s Dolce Vita

At the Miami Beach Edition, architect and designer Achille Salvagni raises a glass alongside Manolo Blahnik in an evening honoring craftsmanship and a shared dedication to living life beautifully.

The Miami Beach Edition, 2901 Collins Avenue

Burberry’s Miami Makeover Burberry partners with BritishAmerican artist Sarah Morris on a vivid redesign of its Miami Design District façade, reimagined in her signature abstract geometry. The collaboration will receive a toast at an in-store cocktail followed by an intimate dinner at Andaz Miami Beach, hosted by Morris herself.

Burberry Design District, 112 NE 39th Street

When the Art World Crowns Its Own

The Art Basel Awards, which were announced earlier this year, will culminate in a grand ceremony hosted during this year’s Miami Beach edition. BOSS (the awards’ presenting partner) will inaugurate the BOSS Award for Outstanding Achievement—granted to an artist with both purpose-driven work and global visibility—while 12 gold medalists will be honored with their prize.

New World Center, 500 17th Street

DECEMBER 5

Brunch With a Bite

Chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten hosts a tasting brunch and dinner at Matador Room (also at the Miami Beach Edition). The family-style experience blends signature favorites with seasonal dishes, beginning with a bespoke welcome cocktail.

The Miami Beach Edition, 2901 Collins Avenue

NADA

The Fairs

Back at Ice Palace Studios for its 23rd edition, running from Dec. 2-6, NADA gathers nearly 140 galleries, art spaces, and organizations from 30 countries and 65 cities. Expect a mix of rising talent, first-time exhibitors, and NADA stalwarts, as well as a programming series presented with the Knight Foundation, PAMM, and CULTURED

Ice Palace Studios, 1400 N Miami Avenue

Untitled Art

Untitled Art returns to Miami Beach from Dec. 3-7 with a 160-deep exhibitor list that spans emerging galleries, nonprofits, and global heavy-hitters across mainstream and emerging art locales. This edition sees the fair continue its “Nest” sector for young galleries and deepen its climate commitment with the Gallery Climate Coalition.

Ocean Drive and 12th Street

Satellite Art Show

From Dec. 4-7, the artist-run Satellite Art Show transforms the entire Geneva Hotel into a maze of installations, galleries, and experiences—an intentionally unruly counterpoint to Miami’s more buttoned-up fair circuit. Raw, strange, and always memorable, it pulls in an audience hungry for the unpolished edge of Art Week (and includes a nightly party at the hotel bar).

The Geneva Hotel, 1520 Collins Avenue

Open Invitational

For its sophomore edition in Miami, the Open Invitational renews its commitment to highlighting progressive art studios and artists with disabilities. Founders and industry veterans David Fierman and Ross McCalla see the fair, which runs Dec. 1-6, as an exercise in what a friendlier, more inclusive art ecosystem could look like.

Melin Building, 3930 NE 2nd Avenue

‘Thank You For Asking’

Maribel Pérez Wadsworth and Kristina Newman-Scott, the Knight Foundation’s new leaders, are on a mission to ensure that the arts remain woven into the fabric of cities across the U.S.

Newspaper magnate siblings John S. and James L. Knight established their eponymous foundation with $9 ,047 in 1950 . Their belief? That a well-informed community could best determine its own true interests and was essential to a thriving democracy. Since then, the foundation has supported the people, insights, and organizations that lead to healthier communities, including by investing in culture and those who make, research, and write about it. Over the past two decades, the impact-focused nonprofit has doubled down on its commitment to the arts sector, pouring more than $485 million into arts and culture initiatives across the country. That support, at a time when federal funding is decimated every day, is no small gesture. Against this fraught backdrop, Maribel Pérez Wadsworth, who joined Knight as the President and CEO in 2023 , sees “hope and momentum at the local level.”

Since January, her mission to champion “artists and institutions as local entrepreneurs, job creators, and community builders” has met its match in Kristina Newman-Scott, the Foundation’s Vice President for Arts. A cultural Swiss Army Knife, Newman-Scott has left her mark everywhere from the art scene of her native Jamaica to the State of Connecticut, where she led the Office of the Arts and State Historic Preservation Office. Ahead of Miami Art Week, where CULTURED, NADA, and the Pérez Art Museum Miami will stage ECOLOGIES, four days of dialogue tackling a cross-section of urgent topics, CULTURED sat down with the executive to talk about leading with curiosity and care.

Kristina, you have approached art from every angle in your career. You were a practicing artist, you worked in radio and TV, you led arts organizations like BRIC as well as Connecticut’s Office of the Arts. Is there one of these experiences that feels like it really paved the way for what you do now?

I would not be at Knight today had I not had all of those experiences. But working for the city then state government, I really had to learn how to not make

assumptions about what people thought the importance of culture was in society. I also got close proximity to city concerns and workings—from the mayor to parks and water to small business development. That really helped me start to understand what it means when you’re tuned in to the people that you’re here to serve, and was the genesis for [my understanding of] how culture, when placed appropriately, can amplify some of these bedrock challenges.

Art can be a conversation starter about so many things, whether that’s climate or housing. It’s a way to open people up.

That’s what I love about working with artists. Because I started out as an artist, I have so much respect for how they lift up the things that they’re trying to communicate. When I worked for the State of Connecticut, we partnered with the Land Art Generator to bring artists, designers, engineers, and community members together in Willimantic for a design challenge centered on renewable energy and public space. The proposal that was selected, Rio Iluminado, was not just a beautiful artwork but a sculptural energy system that used the sun, the river, the cycles of the seasons and the movement of local species to teach us about climate, reciprocity and resilience. This kind of work doesn’t just illustrate solutions—it helps people envision them. Instead of being like, “Here’s a five-point plan that tells you why you should care.”

And when did you first become aware of the Knight Foundation’s work? What conversations have felt the most exciting to you since joining?

Knight came into my world when I was with the State of Connecticut. There was always this great research that Knight would share with the field, and I think I was conducting our own art strategy plan for the Office of the Arts. Since joining, I’ve been doing a lot of grounding work. It’s important for me to work from a place of understanding and curiosity. I want to be service-oriented. Things are moving so fast, and I don’t make any

assumptions. What feels like a win for me is that across our cities, we’ve been curating these conversations where we’re hearing from different leaders coming in to sit with culture [workers and] artists at the table, some for the first time. I feel really energized by that because we’re using our influence—not just in terms of the money that we’re investing, but in gathering, convening, and connecting.

The other amazing thing about this job must be the sheer geographical expanse of the places that Knight is investing in— from Saint Paul to Akron to Miami. Our country is changing in real time. What has it felt like to be working in these different communities in this fraught moment?

Maribel often says that the power to create change is not lost, it’s local. In a place like Akron, we see organizations really experimenting with the policy shifts they can make through an organization like ArtsNow. You’ll see downtown Macon reimagined by an artist and a city planner. There are these visionary leaders who recognize the value of culture. Every place has their own kind of special sauce, but one thing that has been consistent is

that there is an openness. No one is like, “Prove it to me.” They’re all like, “Oh no, tell me more.” It’s a really generative time. If we can test some of these ideas around the arts as infrastructure in authentic ways across our Knight cities, they become models for the entire nation.

What’s a lesson you’re taking from this first year into your next year with Knight?

That I don’t think it’s our role in private philanthropy to be prescriptive. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had grantees look at me and be like, “Thank you for asking.” Before designing an art strategy that is going to be responsive, relevant, and connected, it has to be informed by the people we are in this work with.

Portrait of Kristina Newman-Scott by Nicole Combeau and courtesy of the Knight Foundation.

Curated by Joshua Friedman

Pop Goes Pensato

Joyce Pensato’s darker leanings were often belied by her penchant for depicting cartoon characters. A new show of the late artist’s work lays these dueling forces bare.

BY SAM FALB

Joyce Pensato never met a Mickey Mouse she couldn’t disfigure. The late painter— known for turning pop culture’s most recognizable cartoon faces into dripping, manic images—found a rich terrain, both emotionally and formally, in the onscreen realm. The Brooklyn native’s canvases were always loud, even when rendered in black and white. She wielded enamel with a masterful

HIBA SCHAHBAZ

edge, distilling the iconography of mass culture into something as grotesque as it was human.

Six years after her death at the age of 78 , the ICA Miami has organized an expansive posthumous survey, on view through March 15. The show brings together more than 65 works spanning five decades, from her earliest Batman sketches to the explosive enamel paintings that defined her late era.

“We wanted to bring renewed attention to Joyce’s critical place in American art history,” ICA Art + Research Center Director Gean Moreno tells CULTURED

“Her practice intersects Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and a uniquely personal visual language, yet she has often been overlooked in canonical narratives.” Leading the charge are the ICA’s artistic director, Alex Gartenfeld; curator Stephanie Seidel; and Moreno. Gartenfeld first worked with the artist in 2013 , commissioning murals that traveled to Rome and Paris. Then, in 2017, the trio invited Pensato to create a site-specific installation for the museum’s “The Everywhere Studio” exhibition, which explored the significance of the artistic sanctum. This year’s

show, the most comprehensive presentation of her work to date, unfolds across character-themed rooms—featuring The Simpsons, South Park , Mickey Mouse, and Batman. (“I see him as strength and real power,” she once told New American Paintings of the caped crusader. “I tried to do Spider-Man but he looked like a ballerina!”)

Beyond the cartoon veneer lies a painter deeply engaged with the history of abstraction. Early oil works from the 1980 s reveal the influence of her mentor, Joan Mitchell, with broad slashes of color and flurries of energy. As Pensato’s confidence grew, so too did her wit. “We kept circling back to the tension Joyce draws between humor and darkness,” Seidel continues. “On the surface, her subjects are familiar cultural icons, but she pushes them into a psychological terrain where comedy dissolves into tragedy.” Her influence, they posit, can be felt in the work of a generation of artists, like Sean Landers or Cosima von Bonin, who came of age two decades after her. In their gestures, whether painted or performed, one senses the echo of Pensato’s insistence that art can—and should—simultaneously entertain, disturb, and illuminate the complications of contemporary life.

DIANA EUSEBIO

mocanomi.org

Portrait of Joyce Pensato. Photography by Elizabeth Ferry and courtesy of Petzel.

CURATED BY JASMINE WAHI

CURATED BY KIMARI JACKSON

Self Portrait as Leda (After Michel Angelo) 2020 / Tea, gouache, and watercolor on handmade paper / Courtesy of Simi Ahuja and Kumar Mahadeva

Miami Meets Here

At Miami Tropic, Jean-Georges brings his culinary vision home with the city’s first abc kitchens, curated lifestyle programming, and striking interiors by Yabu Pushelberg—all overlooking Miami’s vibrant Design District.

ON MIAMI TIME

IN MIAMI’S DESIGN DISTRICT, THE PATEK PHILIPPE BOUTIQUE IS A CULTURAL DESTINATION WHERE HERITAGE AND HOSPITALITY COMMINGLE.

PRESENTED BY PATEK PHILIPPE

MIAMI DESIGN DISTRICT BOUTIQUE

BY MARA VEITCH

Today’s Miami, any longtime denizen would agree, is a place of continual reinvention. However, a few things endure: an Art Deco ethos, all-consuming jungle flora, and, of course, a taste for the sumptuous.

The marriage of the city’s old spirit and new appetite is best embodied in the Miami Design District, a cultivated hub for public art, luxury retail, and dining. At its heart, tucked in a 1920 s neoclassical gem, is a Patek Philippe boutique that encapsulates the Miami Design District’s focus on craftsmanship.

Patek Philippe was founded in 1839, and has long been synonymous with an unwavering legacy. The Miami boutique aligns with Patek’s values, and remains committed to providing the highest level of quality and service for current and future generations.

“We wanted the design to feel timeless, so it’s as relevant today as it will be 15 years from now,” says managing partner Brian Govberg, whose family has been a retailer for Patek Philippe since 1987

Inside, the boutique unfolds more like a living room than a retail floor; it’s an unhurried environment replete with lounge seating, a

champagne bar, and a private ivy-covered terrace that beckons clients to linger. Since the timepiece boutique opened its doors in 2022 , it’s become clear that its function has indeed followed its form—clients make ritual pilgrimages to the space for a moment of respite in the midst of the bustling district. “We think less about transaction,” Govberg says, noting that the demand for Patek Philippe timepieces often outpaces availability. “We think more about education, connection, and building relationships over time.”

When a curious visitor arrives at the boutique for their appointment, they are paired with a knowledgeable advisor who has undergone an extensive training program with the brand, ensuring each potential client receives an education and service consistent with Patek Philippe’s highest standards.

For the Patek Philippe Boutique Miami, the goal is simple: offer the kind of experience one remembers. “Even if a client doesn’t purchase a timepiece during their visit, they leave with a story, and a sense that they are welcome.” Perhaps that’s why the space is always humming—with collectors, connoisseurs, and the curious alike.

Mina Stone’s Miami Vice

This tropical twist on a cold-weather staple was inspired by our Food Editor’s trove of Art Basel Miami Beach memories.

BY MINA STONE

This salad is a feast for the eyes and the mouth: colorful, crunchy, tangy, and sweet. It is a perfect addition to the holiday table, as it pairs well with any main dish. Even better, you can make it ahead of time. Imagine this as a classic winter salad that went down to Florida for Art Basel Miami Beach. Cabbage is abundant in the Northeast, while mangoes are one of the most prolific Florida crops. The salad is perfect on its own or mounded on top of roasted fish, pork, chicken—you name it. A few fun facts about the salad. One: It is vegan. Two: The pistachio and the mango belong to the same plant family, Anacardiaceae. Three: It’s heavenly to eat!

Illustration by Cassandra MacLeod.

Eamon Ore-Giron: Conversations with Snakes, Birds, and Stars

48 & 52 Walker Street

November 7 - Decemeber 20, 2025

Art Basel Miami Beach

Booth G20

Dec 3 - 7, 2025

A Glamorous Collective Hallucination Hits Miami

Jarrett Earnest dropped acid at a bathhouse in Washington, DC. The resulting trip brought the renowned critic all the way to Miami, where he’s curated a queer séance of a group show at Nina Johnson.

BY ADAM ELI

When I sat down to interview Jarrett Earnest over soggy eggs and burnt toast at the Washington Square Diner, my first question was, essentially, “How the hell am I supposed to interview you when the show hasn’t gone up yet, and the press release is just a list of artists and a story about you taking acid at a gay bathhouse?” The group exhibition in question—which could only be titled “Acid Bath House”—is on view at Nina Johnson through Feb. 14 . It is the second show Earnest has curated at the Miami space; for his first, in 2014 , he positioned a massive mermaid tail by artist Ann Liv Young in the center of the gallery and draped a pirate flag over its sign. The critic, with his bushy beard and arms tattooed with pieces by Caravaggio and Tom of Finland, has become something of a cult figure in New York’s queer art scene. Some fear him, many desire him, and nearly all seek his approval. “Acid Bath House” features photography, sculpture, textiles, painting, and drawings on paper from artists including Juliana Huxtable, TM Davy, and Genesis Breyer P Orridge. Not unlike their curator, the works’ combined effect evokes a reverence for celestial, mindbending pleasure. To make sense of the séance, I grilled Earnest on his South Florida roots, queer trash, and why getting lost in the sauce is rather glamorous after all.

Tell me about the show.

After the experience described in the press release, I decided to do a show based on queer erotic psychedelia. I’ve curated big group shows before, and I can’t use renderings. I can’t imagine where all of the pieces will go, because an artwork has all of this embodied information that is surplus to an image of it, surplus to how you might describe it. When you place pieces next to each other, it teases out different dimensions—they start speaking to each other. And

that’s what is exciting to me about curating a show. It’s a form of crafting an argument. If you could make that argument any other way, then it doesn’t really need to exist as an exhibition. It could be a book, a podcast, an article.

What are you arguing here?

I’m still waiting to discover that. One thing I love about art is that it’s like spending time with someone. A painting holds a physical space in the room but also a kind of presence. It’s an extension of the person who made it. The show is about pleasure and connection. It’s filled with people I’m super excited to think about together. It feels like throwing the best party ever.

In the press release, you ask, “Does ‘queerness’ still exist? Is it a force? Does it push toward liberation, toward fluidity and change, or is it too easily mired in defining architectures of privilege to get out of its own way? Can we separate queerness from ‘identity’ as it currently functions? And, if so, should we?” Can you speak to that?

The word glamour, historically, comes from a kind of magic—a spell that changes one’s ability to perceive you, and reality generally. That’s what I like about queer artists, especially the ones that I am including. For example, I’m including this LSD drawing by Steven Arnold that has never been shown. He was a photographer who made sets and costumes out of garbage, turning them into just the most unbelievably elegant phantasmagoric images. He died of AIDS and

isn’t as wellknown as he should be. There is a lineage of queerness where you are given trash and, through your imagination, skill, and belief, make it into something fabulous. Glamour is probably what I miss the most in our present reality. There’s so little glamour these days.

What’s something that is completely unglamorous?

The Internet is not glamorous. Contemporary fashion is not glamorous. The way that so many artists our age want to be little professionals is unglamorous. They act like their interest is in making commodities. When you want to participate in the “market” or the “art world” in a certain way, you’re forced to produce too much too fast. To me, spending time is glamorous. You can get lost, which is the beauty of an artistic and intellectual life—the capacity to forget where you’re going and end up somewhere else.

Not to be a diva or anything, but then why are you showing during Art Basel Miami Beach?

You are so right. I am not an artfair person— I do not set foot in them—but I come from South Florida and I care a lot about how fucked up it is. Florida has become a roadmap of our dystopian future. It’s really leading the country in its insane antitrans legislation; it is so grim. While the international art world is focused on South Florida, it is important to me to acknowledge this. So the context is not necessarily about Art Basel; it’s about Florida, queerness, and transness in this extremely hostile environment.

Photography by Jonathan Grassi, 2025, and courtesy of the curator.

Fifteen minutes from Mar-a-Lago, one art space has something to say on behalf of Florida’s LGBTQ+ community.

A Rainbow Statement In A Red State

BY SOPHIE LEE

“I once heard someone, upon entering Beth Rudin DeWoody’s home and spotting a Tom of Finland and many other queer-themed works, say, ‘It looks like a gay man lives here,’” recalls Laura Dvorkin, the co-curator of the Bunker Artspace. It’s not the expected take on the storied patron and Palm Beach art space founder’s collection. But DeWoody is cementing her perennial dedication to the queer canon with “Beyond the Rainbow,” a new show of LGBTQ+ work organized by Dvorkin and the space’s co-curator Maynard Monrow, as well as 19 other artists, curators, gallerists, architects, and writers.

Inspiration first struck when DeWoody visited Paris’s Centre Pompidou two years ago, and took in “Over the Rainbow,” a similar celebration of LGBTQ+ creatives. “That experience sparked the idea to create an exhibition of our own at the Bunker Artspace—one that honors the LGBTQ+ community and their art, impact, and activism at this pivotal moment, and in this crucial place: Florida,” explains Monrow, nodding to the fact that since his election in 2019, the state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, has been pursuing an aggressive campaign to roll back protections for queer families, limit healthcare for trans citizens, and prevent education on gender and sexuality in schools. (The Bunker Artspace also stands a mere 15 minutes from Mar-a-Lago.)

DeWoody’s desire to weigh in on the state’s political climate is a natural extension of her longstanding engagement, says Dvorkin, who points to the patron’s support of organizations like God’s Love We Deliver dating back to the height of the AIDS crisis. The new show, open by appointment only through May 1, 2026 , features artwork by boldface names like Catherine Opie, Andy Warhol, Nicole Eisenman, and Lyle Ashton Harris. Dvorkin and Monrow note less of a focus on including only queer artists, and more of an interest in identifying pieces that limn queer themes of identity, diversity, and representation, or that resonate personally with the panel of curators. “The installation process was an exciting and deeply meaningful journey—one that revealed unexpected connections and conversations,” shares Monrow. “For instance, we placed a Martin Wong drawing of skeletons alongside a handmade exhibition announcement by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and a General Idea work on paper titled AIDS (Reinhardt). Together, these pieces form a powerful curatorial statement on the AIDS epidemic.”

Elsewhere, a room resembling an “old-school library” is filled with books and other work by the likes of Joe Brainard, John Ashbery, and Allen Ginsberg. There are also spaces dedicated to the late Nancy Brooks Brody and Pippa Garner, who was approached to be a curator, but died before the exhibition was put together. Though the Bunker is now flush with these kinds of critical tributes and pieces, Dvorkin wants to ensure her community knows that “first and foremost, this exhibition is a celebration.”

Edie Fake, Leather Weather, 2020. Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody. Photography courtesy of the artist and Broadway Gallery.

Chloe Chiasson, Sunday Confessions , 2022. Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody. Photography courtesy of the artist and Albertz Benda.

Art Basel Miami Beach

Booth C23

December 5–7, 2025

Congratulations to Cecilia Vicuña, who is nominated as an Icon Artist in the 2025 Art Basel Awards.

Cecilia Vicuña in her studio.

Photo by William Jess Laird

A FIELD GUIDE TO THE GALLERY DINNER

WE GATHERED A CROSS-SECTION OF ART-WORLD INSIDERS TO WEIGH IN ON THE GRAND SOCIAL EXPERIMENT THAT IS A GALLERY DINNER. FROM END-OF-THE-TABLE EXILE TO MID-PARTY B12 INJECTIONS, NO CAUTIONARY TALE, DEBAUCHEROUS EXPLOIT, OR HOT TIP WAS OFF-LIMITS.

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Few art-world events are simultaneously as mythologized and dreaded as the gallery dinner. At a great one, you might observe deals being made, career trajectories fast-tracked, and maybe even the next great industry tryst ignited. At a bad one, you could be seated next to someone who has no idea who the artist is, or perhaps worse, isn’t aware that they are already dead. The speeches are interminable. There’s not nearly enough

THE BEST AND THE WORST DINNERS

“I was at a dinner where the crowd was so massive that I didn’t eat. To make it worse, there were ‘VIPs’ who were served at their tables, while other guests weren’t. It’s very bad form to have two levels of guests.”

MERYL ROSE, collector

“I went to one for a close friend’s show where the gallery director only invited his random bros. No press, not even any collectors. I thought, Damn, my friend really needs a new gallery.”

— JANELLE ZARA, writer

“I was recently at a dinner that Jose Martos and his wife, Servane Mary, hosted at their beautiful apartment for Michel Auder’s show. That was really great—an intimate, intergenerational mix of smart and funny people drinking too much wine and smoking cigarettes.”

TIF SIGFRIDS, partner at Canada gallery

STRATEGIC SEATING

“If there is an artist on each side of me, it’s heaven! The worst is to be seated next to an obnoxious collector who insists on showing pictures of their collection.”

MERYL ROSE

“Seated dinners are stressful for everyone—from the hosts to the guests. Someone should publish a book of select seating plans from historical gallery dinners; it would provide a fascinating insight into how the art world functioned at different times.”

MATTHEW HIGGS, artist, chief curator and director of White Columns

“People think the end of the table is exile, but it’s where the best conversations happen.”

CHRISTIANA

INE-KIMBA BOYLE , founder of Gladwell Projects

“The best seat? Beside Sharon Stone— no contest. The worst? Beside an art dealer without hosting privileges.”

ALEX ISRAEL, artist

wine flowing to wash the whole ordeal down. You get the picture.

The gallery dinner is an antiquated exercise. Yet, as a contracting art market and the Covid pandemic have reshaped how the art world spends its time and money, this particular brand of gathering endures. To explore its strange staying power, we asked industry veterans to spill their best and worst memories, hot tips, and words of wisdom for those wondering what a seat at the table really gets you.

“There was a White Cube dinner in an embassy. Stunning setting, candlelight, a great assortment of loose-lipped guests who were well-acquainted with the royals. It was also one of the worst, as I was seated across from a collector who had flipped multiple pieces of mine at auction. They didn’t recognize me and kept trying to make small talk.”

NATALIE FRANK , artist

“I would like to be seated next to Joan Jonas and her dog. Or L.J. Roberts and their dogs. Or Dominique Fung and her dog. Or Timothy Lai and his dog. Or maybe just their dogs.”

PAMELA HORNIK, collector

LOCATION IS EVERYTHING

“The best location is a home... or Mr Chow.”

CASEY FREMONT, executive director of the Art Production Fund

“Somewhere terribly chic, possibly with a bit of faded glory or something pastoral and garden-like—so, the Chateau Marmont.”

—HELEN

MOLESWORTH, curator

Eva Presenhuber, Urs Fischer, Cassandra MacLeod, and Gavin Brown attend a David LaChapelle exhibition celebration dinner at Mr Chow, 2008. Photography by Shaun Mader/ Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

“The best location is a private home you’ve always wanted to see, and when you get there the host says, ‘Yeah go ahead, take a look in my closet. Raid my pill cabinet. Drink whatever wine you think has the prettiest label.’”

SARAH HOOVER, writer

“Anywhere but behind a velvet rope, where I literally sat once at a friend’s dinner.”

ARDEN WOHL, poet and philanthropist

“Just because Hudson Yards is close to Chelsea does not mean it’s a good place to host a dinner.”

—SARAH GOULET, publicist

“The best location is Gasthaus zum Hirschen, a tavern and hotel run by a third-generation family about 30 minutes by car outside of Basel. Galerie Max Mayer has its Art Basel dinner there.”

PAUL LEONG, collector

“The best location is definitely in the middle of a gallery surrounded by an artist’s work. At a James Cohan dinner for their first Byron Kim exhibit, Byron’s seven-anda-half-foot-tall night sky paintings were installed all around us. Each one revealed itself as dinner went on, very similar to the experience I once had at an Ad Reinhardt David Zwirner opening. As I sat in the middle of the gallery talking with the artist’s daughter, Anna, all 13 of those black paintings started to come alive as my eyes adjusted to every nuance.”

MIHAIL LARI, collector

“Confirming a seated dinner and not showing up. Or showing up and leaving an empty seat halfway through dinner.”

MICHAEL NEVIN, co-founder of the Journal Gallery

“Rearranging the place cards.”

ALEX ISRAEL

“Trashing the venue or the food at the table—or worse, being rude to staff. I’ve seen it, and it’s the kind of thing that lingers. The art world never forgets bad behavior at the table.”

CHRISTIANA INE-KIMBA BOYLE

“Treating spouses as less important… and seating them next to people who couldn’t be bothered to talk about or care about the art.”

MIHAIL LARI

“If it’s an open kitchen, people feel like it is okay to come and just pick off the plates. It’s so weird, yet it happens every single dinner. People see food in front of them, and something primal kicks in.”

MINA

STONE, chef and author

NO ONE COMES FOR THE FOOD, OR DO THEY?

“I don’t care about the food as long as it’s served by 9 p.m. and there is dessert.”

BENJAMIN GODSILL, art advisor

“Andy Warhol said it best.”

MICHAEL NEVIN

“I was always trained for there to be an open bar and wine on the tables, and I do think it really feels convivial, more European, and more fun. I remember being at an art event where they poured the wine, and at some point, it got so exhausting because they never came around … The wine should be good, but that does not mean it has to be expensive. I serve more white than red, but there should be both.”

MINA STONE

“Cocktail hour is called that for a reason. You get one hour, then people need to be fed something on a large plate.”

SARAH HOOVER

NOTABLE SIGHTINGS

“The weirdest thing I ever witnessed at a gallery dinner was Sylvester Stallone getting handsy with my friend who was interviewing him.”

NATALIE FRANK

WHAT HAPPENS AT THE GALLERY DINNER…

“A girlfriend and I wanted to remain cool and mysterious by not eating from the buffet, and instead snacked on too many pot brownies.”

CASEY FREMONT

“At a Sprüth Magers dinner many years ago, the person across from me abruptly stopped speaking to me. They still give me the cold shoulder to this day. Was it something I said? We’ll never know.”

JANELLE ZARA

“It’s always fun when the dinner’s at someone’s home. I’ll never forget one such evening at the former residence of my friend, the LA collector Rosette Delug. The night ended in her palatial bathroom, the entire party queued up for B12 shots in the tush—administered, naturally, by our fearless hostess herself.”

ALEX ISRAEL

“I sat next to Jeffrey Gibson at a gallery dinner, and he took a selfie of us on his disposable camera. I’m still waiting for a copy of that photo.”

“Not knowing who the artist is, and not having seen the show.”

—NATALIE FRANK

“Texting during the remarks.”

— PAUL LEONG

“Over-ordering. The horrible last ‘meat course’ when no one is hungry anymore, the shame of being witness to so much waste.”

HELEN MOLESWORTH

“Great food is a connector as well as good wine. When the company is not up to the test, it helps you survive terribly dull conversations.”

VALERIA NAPOLEONE , collector

“Good food is a plus. Good company is a must!”

TIF SIGFRIDS

“Dinners are supposed to start ‘promptly’ after the opening, but they never do. I’m usually starving by the time the food arrives.”

PAUL LEONG

“Once, I witnessed a dealer and a collector quietly arrange an entire loan for a major exhibition between courses. It felt like a piece of art history was being drafted in real time at the table— a reminder that these dinners can be as consequential as they are convivial.”

ARDEN WOHL

“Mid-conversation, a gallery director came up to us and started eating off of my friend’s plate. Yes, we were all a little tipsy. No, none of us were tipsy enough for that.”

JANELLE ZARA

“The weirdest was a dinner in a castle in Venice for an artist who had quietly passed away, although no one knew it at the time. The night ended with an EDM DJ set that lasted until 4 a.m. I woke up to the news a few hours later. In hindsight, I think the dinner was technically a ‘celebration of life’ thing?”

CHRISTIANA INE-KIMBA BOYLE

PAMELA HORNIK

A WORD OF ADVICE

“I think museum directors and curators should publicly reveal which gallery dinners they attend, just like British politicians have to declare any ‘gifts’ that they receive. This would be useful information!”

—MATTHEW HIGGS

“Seating charts are minor masterpieces of diplomacy—trust the system, and make the most of whoever lands next to you.”

SARAH GOULET

“Thank the people that served you. Just to go up to the catering team and say, ‘It was really good. Thank you for this evening.’ Even a wave from the door. Anything to feel like the service portion was acknowledged is really nice. It’s never annoying.”

MINA STONE

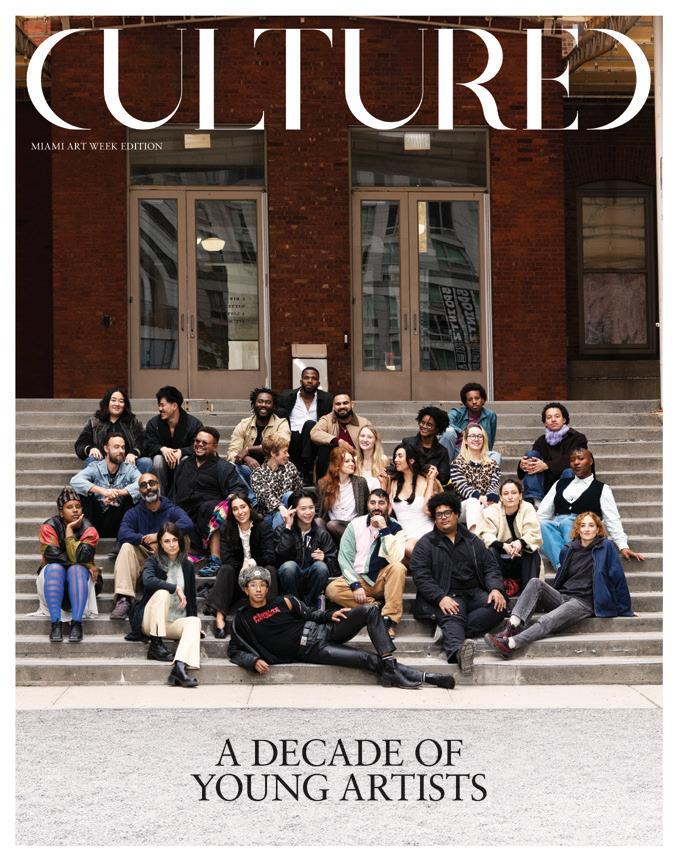

A DECADE OF YOUNG ARTISTS

247 ARTISTS, 10 YEARS, COUNTLESS DELIBERATIONS. TO MARK THE FIRST DECADE OF CULTURED ’S YOUNG ARTISTS LIST, WE GATHERED A CROSS-SECTION OF ALUMS AT MOMA PS1.

Photography by Dana Scruggs

There is a school of thought that takes issue with magazines and nonprofits that sort and platform artists based on age, citing the art world’s sometimes exploitative relationship to novelty and the need to make room for an idea of emergence that isn’t tied to youth.

CULTURED is one of those magazines. Every year for the past decade, we’ve nominated 20 to 30 artists aged 35 or under for the Young Artists list. Some were already market-endorsed when they were featured, others surfaced from staunchly underground scenes. Some received MFAs from lauded programs, others were lifelong

autodidacts. Their practices have been equally wide-ranging: Among the 247 artists featured since 2016 are a clown, a comedian, a stonemason, and an aspiring actor.

We compile these lists with the firm conviction that looking to younger artists is about more than finding the next hot thing. Each time, the exercise brings us back to the drawing board: Who is shaking things up? Who is the art world overlooking? Who is asking the questions no one will?

The exercise surfaces a constellation of voices who are reckoning with a messy world through the work they

make. Their relative youth is really the least interesting thing about them.

And the Young Artists list alums have continued to surprise us at every turn. Since being featured, they have ventured into new mediums, started bands, designed handbags, shown at every conceivable scale and in every conceivable climate. They’ve lost everything, called out the art world’s hypocrisies, and formed mutual aid networks while they were at it. To celebrate a decade of their accomplishments, we welcomed 27 Young Artists—representing every edition of the list thus far—for a

reunion photoshoot at MoMA PS1, which became a colorful backdrop for Dana Scruggs’s unconventional riff on a yearbook picture. Some of these artists have been close for years; others have never met in person. But if the mood on set revealed anything, it’s that they are stronger together.

Left to right, top row: Sasha Gordon, Oscar yi Hou, Arcmanoro Niles, Dominic Chambers, Bony Ramirez, Ilana Harris-Babou, Malcolm Peacock, and Chase Hall; second row: Brian Kokoska, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, Sarah Faux, Cynthia Talmadge, Hannah Beerman, Martine Gutierrez, and Theresa Chromati; third row: Shala Miller, Ajay Kurian, Chloe Wise, Louis Osmosis, Borna Sammak, Andrew Ross, and Jo Messer; fourth row: Rachel Rossin, Miles Greenberg, and Willa Nasatir.

WHAT’S THE SINGLE GREATEST CHALLENGE OF BEING AN ARTIST TODAY?

“Survival.”

HANNAH BEERMAN

“Money. It’s boring and upsetting to say, but that’s what’s ruining everyone’s lives. It all goes to landlords. Artwise, that’s easy; it’s just like, Does it rock or not? And you have control over that.”

BORNA SAMMAK

“Wanting the work to evolve and to not be as impacted by others’ opinions or other work I’ve been seeing.”

SASHA GORDON

“Having to fight a new battle every fucking day. Speaking the language of the trenches. Keeping a Duolingo two-week streak in Trenchanese.”

LOUIS OSMOSIS

“The storm of images we have to contend with.”

—OSCAR YI HOU

“Acceptance.”

THERESA CHROMATI

WHAT’S THE SILLIEST THING A COLLECTOR, CURATOR, OR JOURNALIST HAS ASKED ABOUT YOUR WORK?

“There was a British collector who told me about his visit to India: ‘Even though they were

so poverty-stricken, they still had so much joy in their eyes.’ That was a tough one.”

AJAY KURIAN

“Honestly, I think things could get stupider. Everyone’s a little too informed. I feel like most people’s questions are almost too heady. I challenge someone to ask me stupider questions.”

— MARTINE GUTIERREZ

WHAT’S BEEN THE PROUDEST MOMENT IN YOUR CAREER SO FAR?

“Two things from the 2017 Whitney Biennial stand out. One was working with Tiffany & Co. and going through that whole process with five other artists. It felt like this weird camp where we got to work with this multibilliondollar company and do whatever we wanted. Then I had this installation in the stairwell, and this little girl—she couldn’t have been more than 3 or 4—was reaching for one of my sculptures. Her mother said, ‘I know that’s your favorite, but we have to go.’

That really did it for me.”

AJAY KURIAN

“A homecoming exhibition I had at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis in 2023, 10 years after leaving St. Louis to pursue my education in the arts.”

—DOMINIC CHAMBERS

“To be able to look at a piece and just let it be. Getting to that moment where I don’t have to pack everything in, and instead be like, It’s done, move on.”

THERESA CHROMATI

WHERE DO YOU SEE YOURSELF IN 10 YEARS?

“Back in my home country, the Dominican Republic. Somewhere close to the beach, where I would have my studio close to the water. I could see myself being, like, 100 years old and still working.”

BONY RAMIREZ

“In New Orleans, in a halfbathhouse, half-metal venue.”

BORNA SAMMAK

“Retired, ideally. The survey is happening this year, and then it’s just gardening.”

—MARTINE GUTIERREZ

WHAT’S A RUMOR ABOUT YOU THAT YOU KIND OF WISH WERE TRUE?

“That my work is really cerebral.”

—ANDREW ROSS

“That I’m dating Timothée Chalamet. Everyone confuses me with Kylie [Jenner] all the time, it’s crazy.”

—CHLOE WISE

“They’re all true, babe.”

—MILES GREENBERG

Miami Beach, USA

GEORGE NAKASHIMA, BENCH FROM AN EXCEPTIONAL PAIR OF BOOKMATCHED CONOID BENCHES, 1972, COURTESY OF MODERNE GALLERY

19TH STREET AND CONVENTION CENTER DRIVE

YOUNG ARTISTS 2025

When CULTURED debuted its first Young Artists list a decade ago, we were coming off a few years of a booming art market. Some emerging artists had made six-figure sums from a single exhibition. But what goes up must come down—and down it went.

The same boom-and-bust cycle is happening now. What we know from experience is that artists who are coming up at this moment have more freedom to experiment, to fail, and to grow. To help lighten their load, for the second year in a row, CULTURED is teaming up with MZ Wallace and an expert jury to award one artist from our 10th annual list an unrestricted $30,000 grant.

The following pages introduce 27 artists aged 35 and under who are working in the United States at a time of great economic uncertainty and political upheaval. They were selected from dozens of submissions by the magazine’s editors and contributors, as well as art dealers, collectors, and artists from around the world. Each has a rising profile, something important to say, and a novel way in which to express it.

SHEN XIN

35 — SAINT PAUL, MNI SOTA MAKOCE (MINNESOTA) AND PORTREE, ISLE OF SKYE

Operating out of New York and Los Angeles, as well as Tucson, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Saint Paul, the artists in this year’s cohort work in media ranging from video games to precious gemstones. But they rarely restrict themselves to a single material (or even one home base). And for all that talk about young people being sexless these days, plenty of them are unafraid of exploring the erotic in their art.

One thing they all share is a commitment to pushing their work into uncomfortable, sometimes revelatory, and deeply engaged places. CULTURED will continue to mirror that commitment, now and in the years to come, no matter the weather. Thanks to the work of these artists, the future looks bright.

This year’s Young Artists Prize winner will be selected by MoMA curator T. Lax, Hammer Museum curator Erin Christovale, and Met curator Jane Panetta. The recipient will be announced on Dec. 10.

What’s in a name? Shen Xin, who was born in Chengdu, China, has centered their practice on what the language we use surfaces, and leaves out, since earning an MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art in 2014. Their work—exhibited at the Swiss Institute, Walker Art Center, and through Dec. 21 at Edinburgh’s Collective—filters this inquiry through moving image, performance, and writing that draws from personal history, myth, and scientific research.

Describe one work you’ve made that captures who you are as an artist. Since the relationship between the works and myself is not unchanging, I can describe the most recent work I’ve made. It is a 16mm film with a short duration in black and white, and the film is developed by utilizing the leaves of a type of cotoneaster on the Isle of Skye. Titled Bearing Fruit of Fondness, it’s a film that explores innate belonging of mother-child patterns in one’s life through filming the everyday, that is absent of both strangeness and familiarity.

Describe your work in three words. Truth, kindred, light.

What’s an artwork you didn’t make, but wish you had?

On my father’s bookshelf, I encountered

Liverpool from Wapping by John Atkinson Grimshaw when I was little. I was taken by the warm light; it reminded me of how we used to pass by windows and shop fronts like that. The quality of this light near the water is hard to come by today.

What’s an underrated studio tool you can’t live without?

A pair of binoculars. If you live in built-up areas this might sound strange, but I live in the country and it’s a form of distraction I enjoy: watching those who come and go in the sky and in the ocean.

Is there a studio rule you live by? I try to tune into my aspirations before I start doing anything, while keeping in mind the subject for every practice.

Photography by Geoffrey Van.

COCO KLOCKNER

34 — NEW

Coco Klockner cut her teeth in the DIY music scene of the early 2010s, where she finessed a sense for sound, site sensitivity, and timing that has percolated into sculptural interventions shown at Silke Lindner, lower_cavity, and, most recently, in her first institutional solo, on view at SculptureCenter in Queens through Dec. 22. Her material lists have included everything from sounding rods to a first-aid kit—all fodder for an ongoing investigation into strategies of transfeminine representation and beyond.

Describe one work you’ve made that captures who you are as an artist. A piece I return to is from 2022 . It consisted primarily of sculptural adjustments to a set of hi-fi tower speakers that I grew up with. They played a sound piece that was very slightly modulated by convolution reverb profiles taken at 10 -minute intervals of the space that the work was installed in, creating a duplicated reverberation of the space—as if there was a perfect sonic model of the room inside of the room.

I think about the disclosures demanded of trans people—always but especially this year—and how a perpetual demand to know what’s inside, what’s underneath, what a voice sounded like, and so on, operates. The sonically doubled room somehow felt like a resonation of that dynamic, but also just a very earnest experiment in how material functions when it’s performing.

Imagine someone gives you $150,000 to make anything you want—no strings.

What are you making?

I would buy a boat and install one perfect sculpture inside of it before sending it out to sea somewhere, maybe near Point

In Yasmine Anlan Huang’s Her Love is a Bleeding Tank —featured in the 2024 Whitney Biennial—the Guangzhou-born artist refracts both the yearning and alienation of girlhood through a cartoon image projected onto an increasingly watery eye. The video poem distills Huang’s cross-media interest in channeling the codes of melodrama and the “good girl” archetype into work that probes everything from fetish to techno-capitalism. Her second book, Becoming Everyone, Everywhere, will be published early 2026.

Nemo. I’d like for it to circulate in the ocean forever.

What’s an artwork you didn’t make, but wish you had?

Jason Rhoades’s The Costner Complex (Perfect Process) from 2001. Gorgeous, mind-altering, strange, depressing, uplifting.

What’s an underrated studio tool you can’t live without?

Cookies and treats within arm’s-length distance.

Is there a studio rule you live by?

Cookies and treats within arm’s-length distance need Tupperware; mouse-chewable plastic from the store is not enough.

Who are the three people, alive or dead, invited to your dream art-world dinner party?

Greer Lankton, Candy Darling, and Harun Farocki would be so funny. I think Harun would clam up, Greer would be starstruck by Candy, and Candy would just be eyes glued on the door for the next most glam person to walk through.

YASMINE ANLAN HUANG

29 — NEW YORK AND LONDON

Imagine someone gives you $150,000 to make anything you want—no strings. What are you making?

This would be ideal for realizing my first medium-length film, which I am currently fundraising for. It centers on an optical condition known as a rosette cataract, which, as its name suggests, manifests as a rosette pattern in the eye. The protagonist wakes to find herself afflicted with it, and as she adapts to this metaphorical affliction, her altered vision causes her to romanticize war, pain, and violence. In my previous films, I didn’t have the resources to fully realize the haunting, intertwining beauty and violence of my vision. For this one, the central optical effect cannot be achieved by makeup but requires CGI, which I’m no expert in and costs a lot. With this no-strings-attached money, I could work with specialists of CGI and lighting to realize the work’s full potential.

Describe your work in three words. Self-referential, innocent, and monumental.

What’s an underrated studio tool you can’t live without?

Honestly, since I travel so frequently and have to pack everything—like works, tools, etc.—into my 30 -inch luggage, it’s hard to imagine anything I could truly not live without. In such conditions, everything seems disposable. In a sense, my luggage becomes my studio. With that being said… do Bluetooth speakers and professional headphones count as studio tools or studio vibe boosters?

Is there a studio rule you live by? Follow the spreadsheet and calendar entry, and never be a deadline fighter!

Photography by the artist.

Photography by Yiyang Cao.

ALICE BUCKNELL

32 — LOS ANGELES

ASHER LIFTIN

Describe your work in three words. Constructing a picture.

Tell us about a teacher who changed the way you think about art.