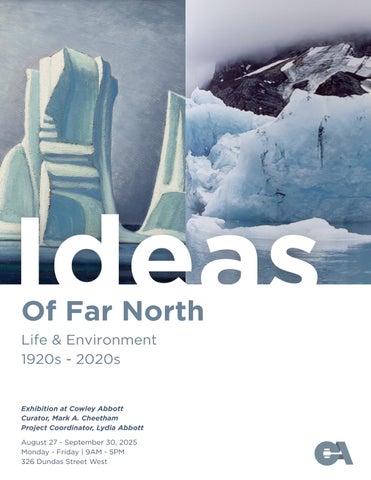

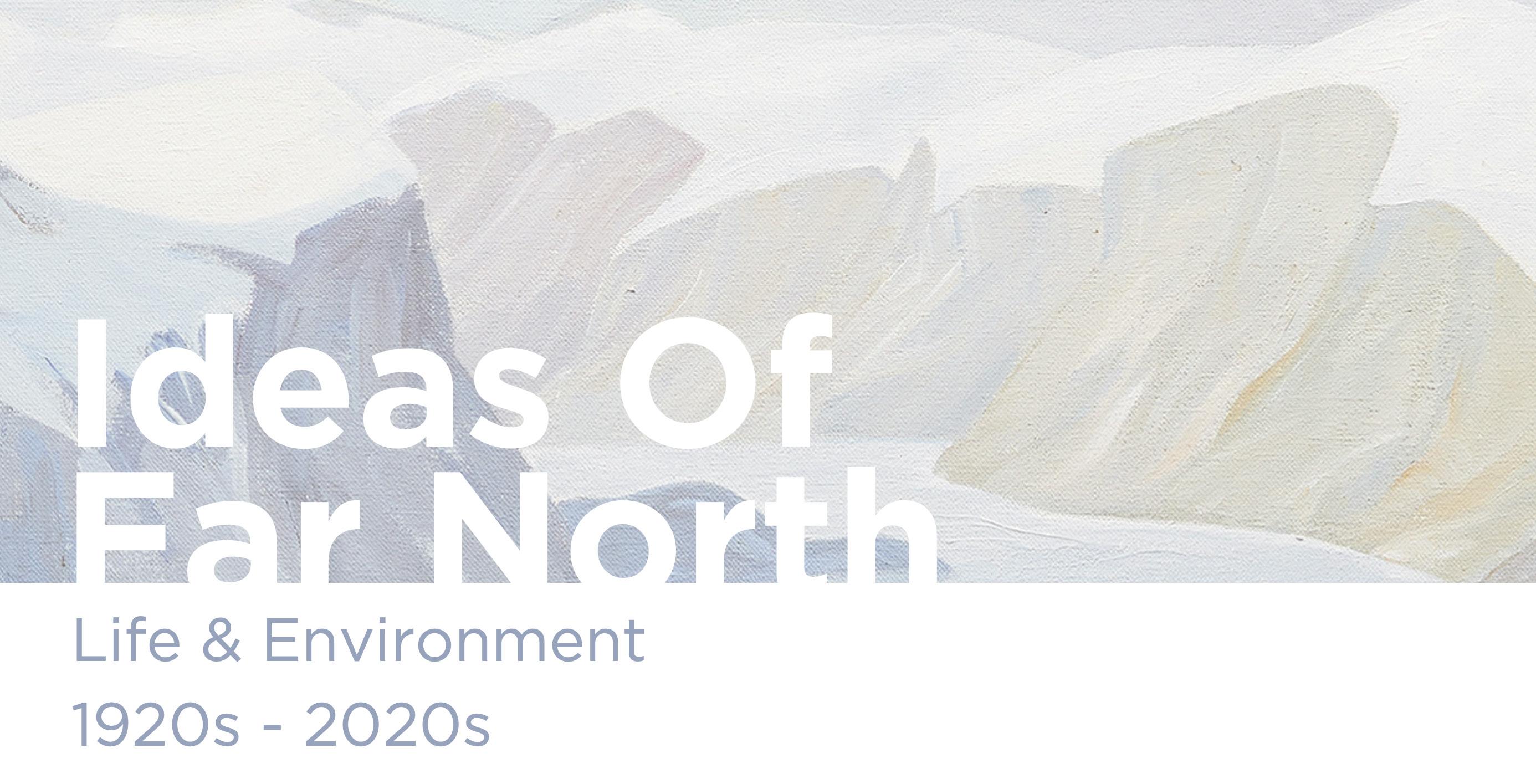

Of Far North

Life & Environment

1920s - 2020s

Exhibition at Cowley Abbott

Curator, Mark A. Cheetham

Project Coordinator, Lydia Abbott

August 27 - September 30, 2025

Monday - Friday | 9AM - 5PM

326 Dundas Street West

From early maps to lavishly illustrated travel narratives to oral histories, paintings, and prints, images of the far north from both southern and Indigenous standpoints have been increasingly integral to its understanding. Beginning in the 1920s, some of Ontario’s best-known artists, notably Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, and later, Doris McCarthy, travelled to, pictured, and defined for many southerners the look and nature of the far north, including the Arctic. Their views encapsulate a still-potent identity for many Canadians, but for others, paradigms to revise. Ideas of Far North explores how visions of this region have changed over a century. Challenged by Indigenous and settler artists, and shaped by global environmental concerns, familiar paradigms have evolved. Once seen as an existential threat, the region is now recognized as itself vulnerable to climate change. The exhibition invites us to examine the constant interaction between different versions of the far north from our southern perspective in Canada and from other parts of the circumpolar north.

Always a relative term for those not living there, North has been taken as aggressively negative (a murderous climate) as well as transcendently positive (a source of mystical purity and renewal). Well before Canadian Confederation in 1867, the polar regions of Inuit Nunangat were zones of speculation—exploratory, economic, and imaginative—whether for those who lived there, for visitors, including whalers and the infamous British captains Martin Frobisher in the sixteenth century and John Franklin in the nineteenth, and for literary figures, most notably Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Jules Verne’s The Purchase of the North Pole (1889).

Ideas of Far North, as a title and collection of work spanning one hundred years, is designed to sound and look both familiar and unexpected. The title will be familiar to many—thanks to A.Y. Jackson’s book The Far North: A Book of Drawings by A.Y. Jackson (1927); pianist, composer, and thinker Glenn Gould’s 1967 The Idea of North radio program, in which he sampled testimonies of what North meant to five respondents in Canada’s Centennial year; and comedian, musician, and art collector Steve Martin’s exhibition The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris, seen in Los Angeles, Boston, and Toronto in 2015-2016. Many visitors will be acquainted with some of the work on view, but not in the contexts developed by more recent presentations of far north.

Why return to these well-canvassed themes and artists? From the Group of Seven to N.E. Thing Co.’s jocular mapping of the Arctic circle in the late 1960s or Joyce Wieland’s The Arctic Belongs to Itself of 1973, presentation of the North in Canada (as elsewhere) is bound up with nationalism. These well-known contexts are enjoined today by renewed questions about the sovereignty of this country and of northern peoples. New attempts to define a national identity follow. In addition—before, during, and doubtless after the politics of 2024-2025—the environmental vulnerability of this region has and will run according to its own alarming clock, however much human activity ignited what seems to be an increasingly urgent countdown. Interlaced with these pressing matters is the enduring passion for many types of pictures of the far north, from iconic Group of Seven depictions of icebergs to Inuit musings on their rapidly changing existence in this region to overtly ecological art.

In addition to these resonances with earlier investigations of the art of the North, I want to insist briefly on the different inflections in the title of this exhibition, variations that I hope will lead to new looking and thinking. Ideas of Far North claims multiplicity, unlike the other three titles noted and a superb book on the topic, Sherill Grace’s Canada and the Idea of North (2001). While many have adopted a plural understanding of the art and its issues in this context—none more tellingly than Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art, edited by John O’Brian and Peter White (2007; 2017)—adding the ‘s’ and dropping the definite article ‘the’ reminds us to see how different recent art focused on this region is from its acknowledged predecessors and to think with the art about ongoing environmental, political, and identity issues. Ideas of Far North does not offer a redundant critique of earlier paradigms but sets out to establish new comparative frameworks in the present.

One of the pleasures of exhibitions is that as viewers, we are largely free to look where we wish and to entertain whatever comparisons occur to us. Curators have a narrative, but it is always open to on-the-spot emendations. What through-lines are suggested in Ideas of Far North? Chronology is significant because artists frequently refer to predecessors. The earliest examples included are Frederick G. Banting’s drawings and A.Y. Jackson’s book of 1927; the most recent is Laura Millard’s Motion Lamp 3 from 2024. Yet these poles are connected. Millard began as a painter, and, like Banting, she acknowledges the inspiration of the Group of Seven’s en plein air approach at high latitudes. Second, geography figures in the definition of ‘far north’ and is consciously various in this exhibition, which includes work from Svalbard, Norway, plus a range of locales in Canada, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, the northern Pacific Coast, and Alaska. But geography is not the prime factor in the ever-relative definition of far north. Themes are also in play, including Inuit mythologies and everyday life, the nature of sea, land, ice, and atmosphere—especially around liminal shorelines—and urgent ecological problems. Technologies of transport and conveyance appear in many of the works collected here.

What most distinguishes the recent examples from earlier views of the far north, however, is the medium in which investigations are undertaken. Gould’s radio play remains a beacon of radical media innovation for its time. Ideas of Far North presents an array of inventive media and techniques, including video and the sonic environment in experimental music and sound art (Walde), a salvaged object turned into sculpture (Gruben), photographs taken through lenses made of ice (Duke) and from a drone (Millard), prints and drawings by Inuit artists, and Millard’s multi-media motion lamp. The exhibition encourages viewers to draw visual and conceptual relationships among disparate works with northern themes.

The following numbered entries on individual artists and artworks proceed chronologically and emphasize thematic, geographic, and intermedial relationships. An online version of the exhibition and additional information can be found at https://arcg.is/11f9L90 or scan the QR code below.

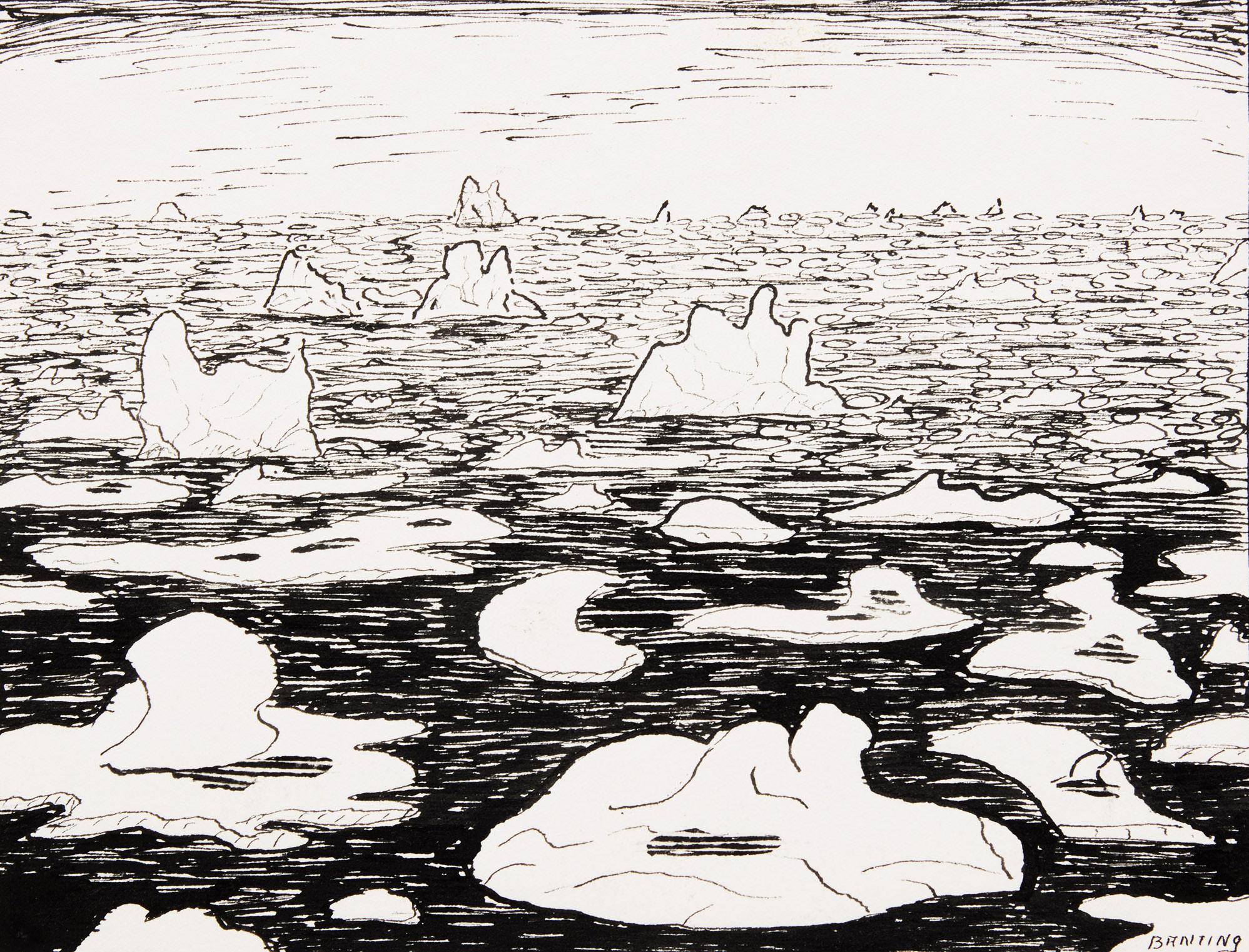

1. Frederick Grant Banting

Dundas Harbour, 1927 ink on paper signed lower left

4.75 x 6 ins (12 x 15.2 cms)

2. Frederick Grant Banting

Icefield, 1927 ink on paper signed lower left

4.75 x 6 ins (12 x 15.2 cms)

It comes as a surprise to many that Dr. Banting— best known as the Nobel Prizewinning co-discoverer of insulin—was a passionate and accomplished artist. With his close friend A.Y. Jackson, he travelled extensively in the Arctic in the summer of 1927 on the government supply ship Beothic. Banting had been tutored by Jackson over the previous two years. Their responses to the landscape of the far north are similar in structure and focus, but this takes nothing away from Banting’s abilities. Both men recorded what they saw from the ship and on shore in small, rapid sketches, some of which they later developed in larger oil paintings. Both Dundas Harbour and Icefield have an abiding energy and directness thanks to Banting’s assertive lines and sharp tonal contrasts. The latter was illustrated in Jackson’s book Banting as an Artist (1943). The distant horizon lines in both drawings suggest a vast space despite the constraints of the small surface. The immediacy of these drawings remains a century later.

1.

2.

3. Alexander Young Jackson (author)

The Far North: A Book of Drawings by A.Y. Jackson

Rous and Mann Ltd., Toronto, 1927, edition 1 of 1000, printed on Carlyle Japan paper, with an introduction by Dr. F. G. Banting and descriptive notes by the artist, signed by A.Y. Jackson on the title page 9.5 x 8 x 0.5 ins (24.1 x 20.3 x 1.3 cms) (overall)

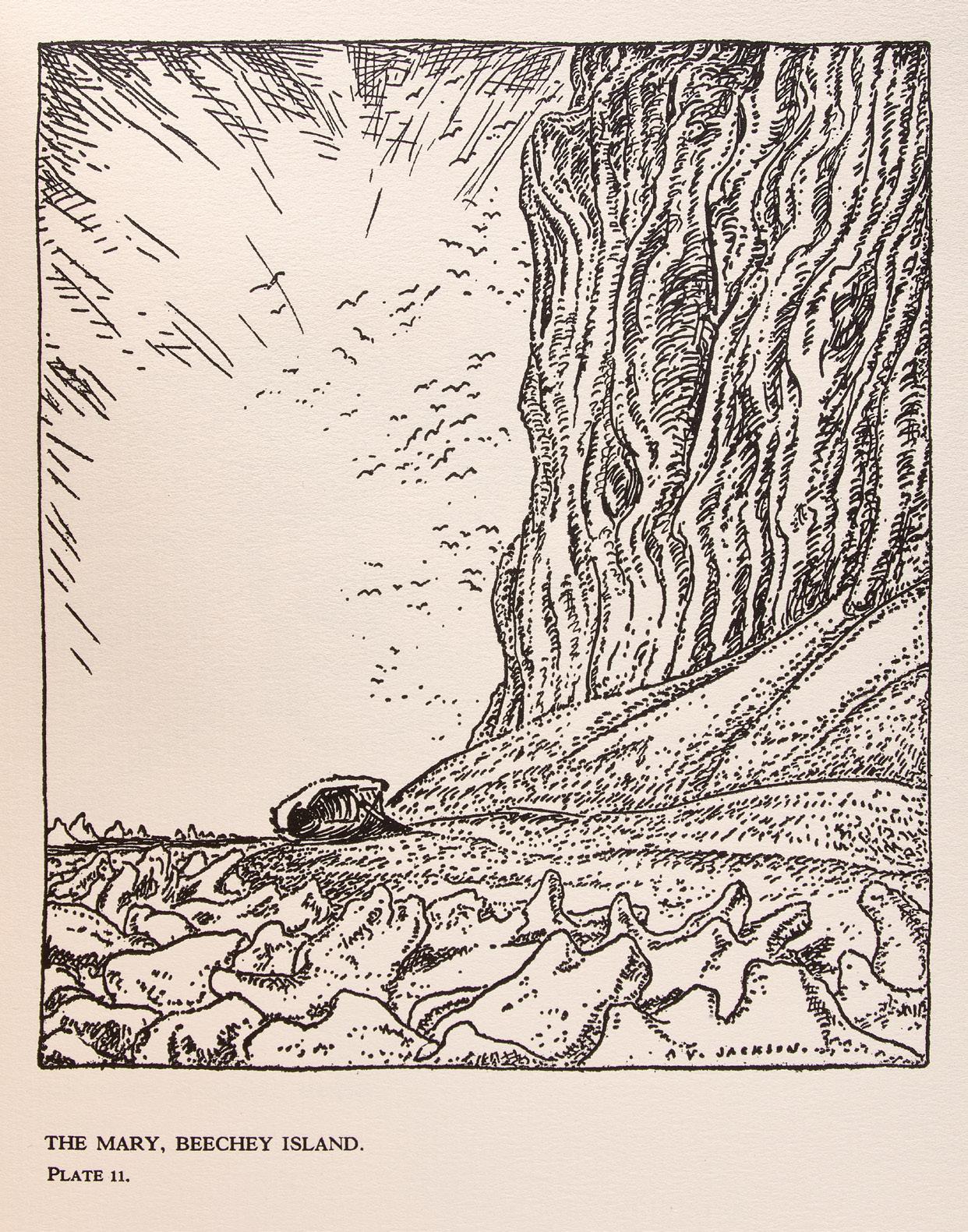

This personal and detailed record of A.Y. Jackson and Frederick G. Banting’s Arctic voyage in 1927 can remind us of two significant aspects of Jackson’s approach to art (and to some extent of the Group of Seven’s generally). First, the subject is not only landscape: Jackson is interested in the history of this region from a Western, visitor’s perspective. He draws and writes about a famous site where the lost John Franklin expedition of 1845 in search of the Northwest Passage first wintered, Beechey Island. On August 4, 1927, he comments, “The small relief ship left for Franklin is still on the beach. A great pile of sheer rock about a thousand feet high rises from the water…. A miserable little beach [is] where Franklin and his men made their winter quarters.” Second, the book includes seventeen black and white woodcut plates that reproduce Jackson’s drawings. Printed reproductions and broad public dissemination across Canada were key to the Group’s familiarity and reputation as artists for the nation.

4. Lawren Stewart Harris

Icebergs, Smith Sound II, c. 1930 oil on panel signed, titled and inscribed “I. Icebergs-Smith Sound II” on the reverse 12 x 15 ins (30.5 x 38.1 cms)

Lawren Harris was drawn north as if there were a magnet at the pole, as was imagined on maps for centuries. The trajectory of his quest for ever purer and more dramatic landscapes took him out of Toronto to Algonquin Park, the Laurentian Mountains, the Algoma region of Northern Ontario, to the Rockies, and in 1930, to the Arctic with A. Y. Jackson. Though he valued what Torontonians call the ‘near north,’ it was on this voyage—again on the Beothic—that he made some of his most memorable work. Harris went north, but crucially for his thinking and subsequent painting, he sought to bring what he construed as its spiritual purity back to the south as an infusion for himself and society at large. North is distilled in a painting didactically titled Winter Comes from the Arctic to the Temperate Zone (1935; McMichael Canadian Art Collection). Painted after his trip to the Arctic, after the last Group of Seven exhibition in 1931, and as the cosmopolitan Harris was experimenting with abstraction as artist in residence at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, the painting is a pivotal image of the ideology of North as a cleansing force in society. Ultimately, Harris’s theosophical beliefs removed the north from the confines of time and space altogether.

We can see Icebergs, Smith Sound II as a step towards Harris’s goals. Simplified and stylized, the sculpted lines of the icebergs create monuments, even in a small sketch—whose dimensions are no barrier to the immensity of the sea, land, and sky that Harris evokes. Harris and Jackson exhibited their initial Arctic paintings at the Art Gallery of Toronto in May 1931, literally bringing the Arctic to the temperate zone.

5. Alexander Young Jackson

Eastern Arctic, 1930 oil on panel

signed and dated 1930 lower right; signed, titled, dated, inscribed “Artic” [sic], “Joe McCulley”, “owned by “H.V. Ross” and the Naomi Jackson Groves inventory number (”NJG 108”) on the reverse 8.5 x 10.5 ins (21.6 x 26.7 cms)

As on his 1927 trip in the Arctic with Frederick G. Banting, A.Y. Jackson showed his interest in the human presence in the Arctic landscape, past and present, and in this sketch, Inuit integration with nature. A Painter’s Country, his autobiography, is replete with references to Arctic explorers. Here, however, he is very much in the present. He shows what we take to be a family—with children, dogs, and the technologies necessary for this terrain and climate, including the summer tents and qamutiiks (sleds)—encamped in apparent harmony with the dramatic land and sea from which they live. The locale is identified as ‘Nerke’ on Siorapaluup Kangerlua (Robertson Fjord) in northwestern Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland). Knowing little about Inuit ways and legends, Jackson nonetheless painted aspects of their everyday lives that recent Inuit artists also emphasize, whether in the latter part of the twentieth century (see the following entries) or today in Maureen Gruben’s case (no. 15).

6. Lucy Qinnuayuak, E7-1068, Kinngait (Cape Dorset) Umiaks, 1976 stonecut

inscribed with the artist’s name, titled, dated “Dorset 1976” and numbered 31/50 in the lower margin 28 x 25 ins (71.1 x 63.5 cms)

Since the 1950s, the Kinngait Printmaking Studios have been a locus for the development of Inuit art in Nunavut. Living in Kinngait from the 1960s, Lucy Qinnuayuak was a leading practitioner in an ever-increasing variety of printmaking in this locale. Her prints and drawings are widely exhibited and collected. Umiaks is both immediate in its internal narrative and expansive in its reference to the wooden-framed, skin-covered boats used extensively in the circumpolar north for millennia to transport people and cargo and for hunting larger marine animals.

As we see here, some had sails. Qinnuayuak’s version is more nuanced than its apparent simplicity suggests. Pivotal elements of the design change from the top to the bottom image: the pattern on the side of the boat changes and a seal appears behind the boat, seeming to watch it float by. Only the person in the bow remains in the same watchful attitude.

7. Doris Jean McCarthy

Iceberg Fantasy #10, 1972 watercolour

signed lower right; titled and dated “721026” (26 October 1972) on a card attached on the reverse of the frame 12 x 15 ins (30.5 x 38.1 cms) (sight)

8. Doris Jean McCarthy

Pangnirtung, 1973

acrylic on canvas

signed lower right; titled and dated “730803” (3 August 1973) on the reverse 24 x 30 ins (61 x 76.2 cms)

Doris McCarthy is perhaps best known for her images of icebergs, a particularly complex example of which we see in Iceberg Fantasy #10. Her first excursion this far north was in 1972, the date of this watercolour, after she retired from a forty-year teaching career. She returned in 1973 and then frequently to different locations in the far north. Though McCarthy’s icebergs are often compared with Lawren Harris’s from the 1930s, this example suggests limits to the analogy. The intricate mirroring of forms here departs from Harris’s assertive stylization of form and colour. In Pangnirtung, she presents one of the most physically dramatic locales in Nunavut.

7.

9. Ruth Annaqtuusi Tulurialik, E2-16, Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake)

Untitled (Legend of The Sea Spirit), c. 1990 coloured pencil signed in syllabics lower right 22.25 x 30 ins (56.5 x 76.2 cms) (sheet)

An important centre for Inuit artmaking established in the early 1960s, annual collections from the Sanavik Co-operative at Qamani’tuaq first appeared in 1970. Ruth Tulurialik began working at the co-op in this year and has continued to create highly coloured and complex images of Inuit life and mythology. The legend of the sea spirit seen here is related to the many versions of the creation myth that turns around the sea goddess Sedna. In 1986, Tulurialik and David F. Pelly published Qikaaluktut: Images of Inuit Life, in which many of her drawings evoke and picture Inuit oral histories. There, as here, the images trace stories that are at once epic and whimsical.

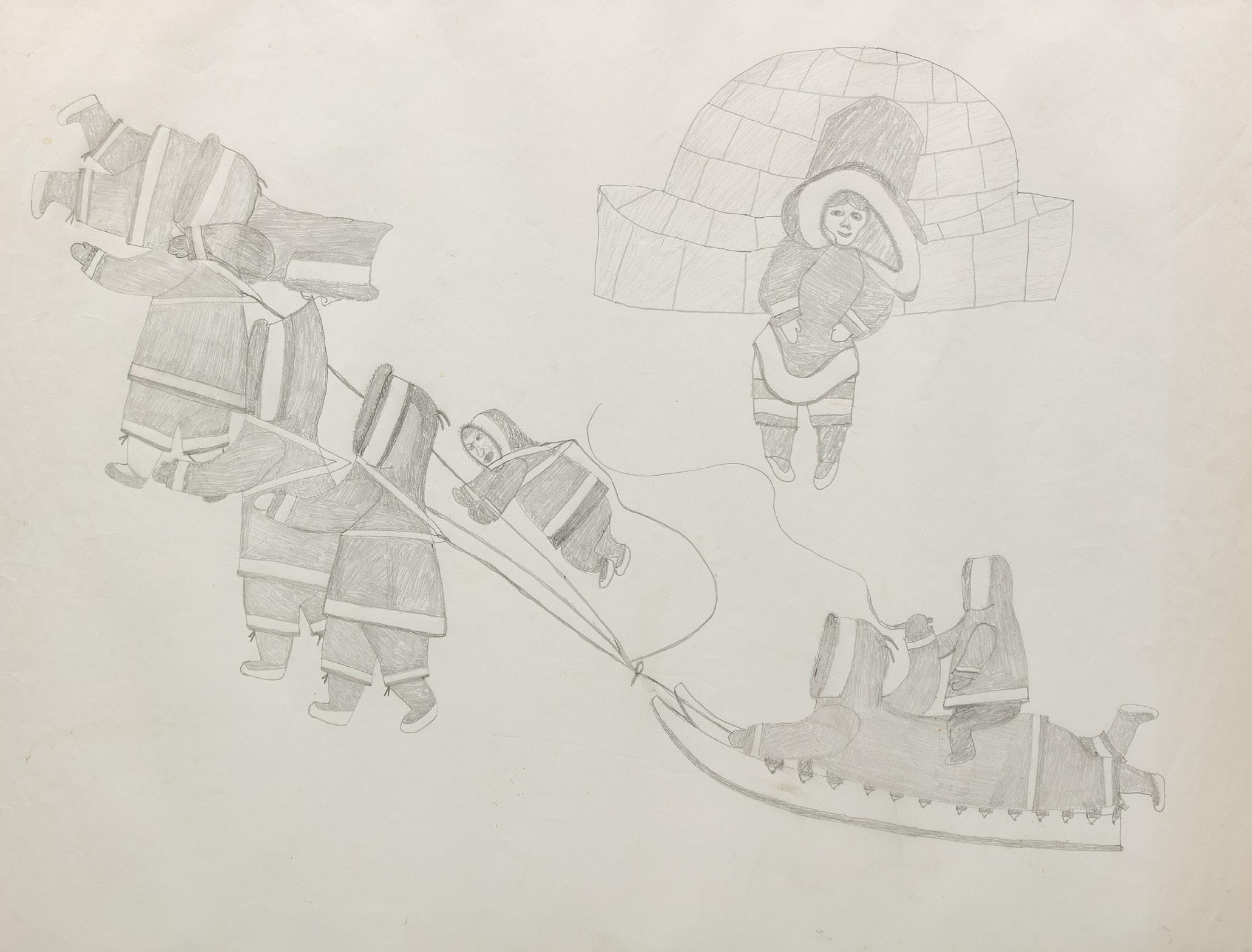

10. Mary Pitseolak, E7-974, Kinngait (Cape Dorset)

Untitled (Family and Qamutiik)

graphite drawing

20 x 25.75 ins (50.8 x 65.4 cms) (sheet)

Working in sculpture and the graphic arts out of Kinngait, Mary Pitseolak has been exhibiting since the early 1960s. Here we see a family group on a qamutiik, their dwelling nearby. The image is playful: a small figure rides atop an adult on the sled. Other figures take the place of the expected dogs. The sled is again a central technology, now seen from inside this seasonal hunting culture rather than by an outside observer, as in A.Y. Jackson’s Eastern Arctic (no. 5).

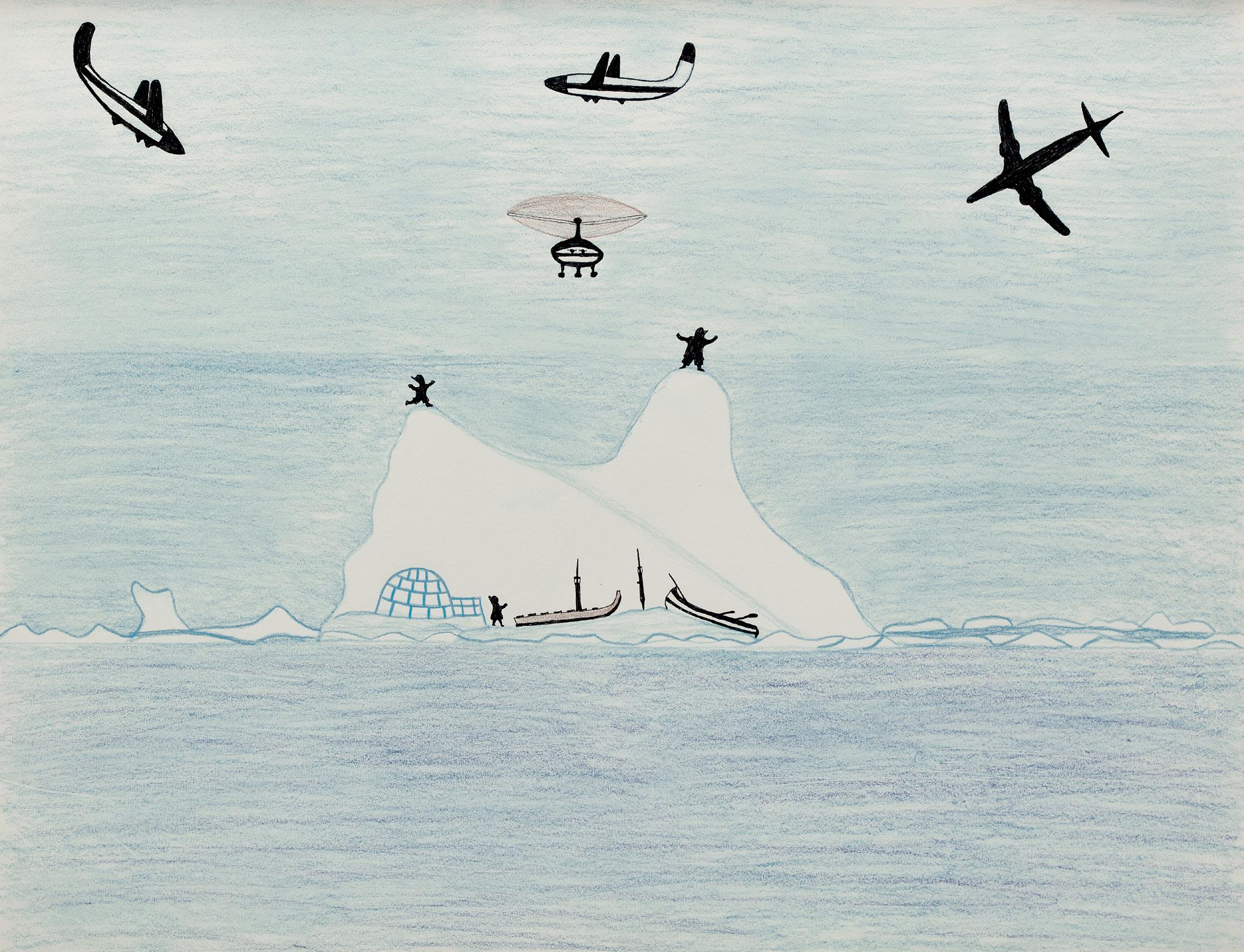

11. Pudlo Pudlat E7-899, Kinngait (Cape Dorset)

Untitled (Airplanes), c. 1991-1992 coloured pencil and felt tip 20 x 26 ins (50.8 x 66 cms)

A significant theme in Inuit art is the intrusion of and adaptation to Western or southern technologies. Some of the best known are Pudlo Pudlat’s drawings from the Kinngait studios, where he began to make art in the 1960s. Here, three Inuit stand on an iceberg. Two have climbed to its peaks; the other remains on the floe with their boats. The sky is filled with aircraft. Two of the three planes and one helicopter seem intent to land, or to come as close to the ground as possible. The other plane is departing, suggesting the feeling—if not the literal description—of busy air traffic. The figures’ gestures are ambiguous, implying that the supplies and visitors flown into the Arctic are a mixed blessing. The delicacy of Pudlat’s technique only intensifies the seriousness of the changes he witnesses in the contemporary Arctic.

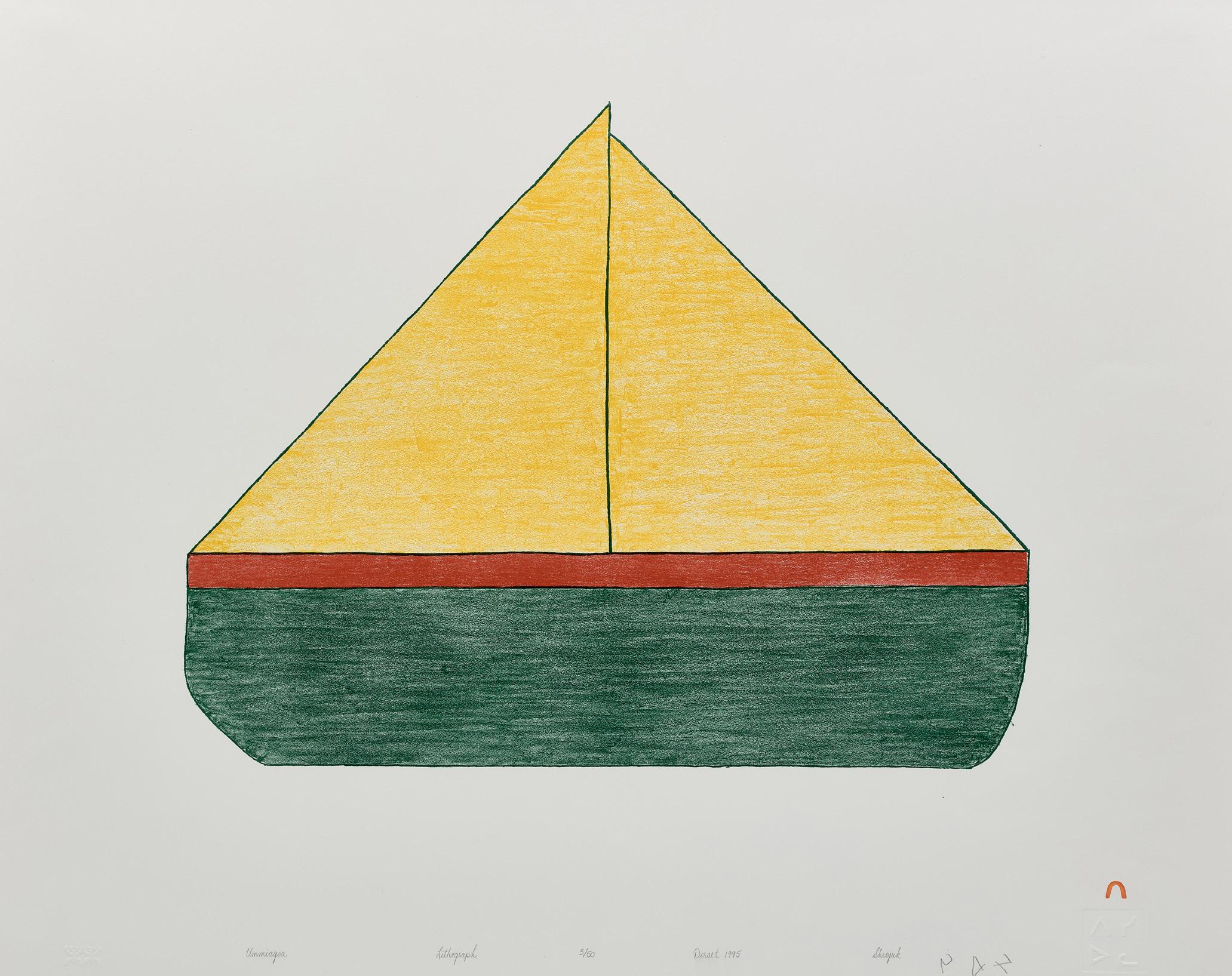

12. Sheojuk Etidlooie

E7-941, Kinngait (Cape Dorset)

Ummiagoa (Toy Boat), 1995 colour lithograph signed in syllabics, inscribed with the artist’s name, titled, dated “Dorset 1995” and numbered 3/50 in the lower margin; collector’s inscription on the reverse 22.5 x 26.5 ins (57.2 x 67.3 cms) (sheet)

Sheojuk Etidlooie only began to make art in her sixties, producing prints and drawings in the Kinngait studio. Ummiagoa presents the uniqueness of her style in its radical simplification of the form and saturated colour. Akin to Maureen Gruben’s sculpture based on a toy sled (no. 15), the boat’s centrality as a conveyance in contemporary Inuit life is underlined by its conscious reproduction in miniature for children’s play. It is important to everyone in the community.

13. Paul Walde

Glen Alps Score from “Alaska Variations”, 2016 edition of 5 plus 1 artist’s proof archival digital print on matte paper 15 x 33 ins (38.1 x 83.8 cms) single channel 4K video installation with stereo audio, duration: 68:30

Glen Alps is an aural and visual mapping of the flora on Little O’Malley Mountain at Glen Alps in Anchorage, Alaska. Walde composed the score by “assigning instruments to each major grouping of vegetation on the mountain face; [he] translates the location and size of the trees and shrubs into standard notation, with each species being represented by a group of instruments.” He explores the considerable extent to which plants at higher altitudes and latitudes are especially vulnerable to climate disruption. His sonically emotive Glen Alps is an explicitly environmental artwork and an example of ecoacoustics. If he were to redo the work now, after almost ten years, change in the vegetation would produce a different score.

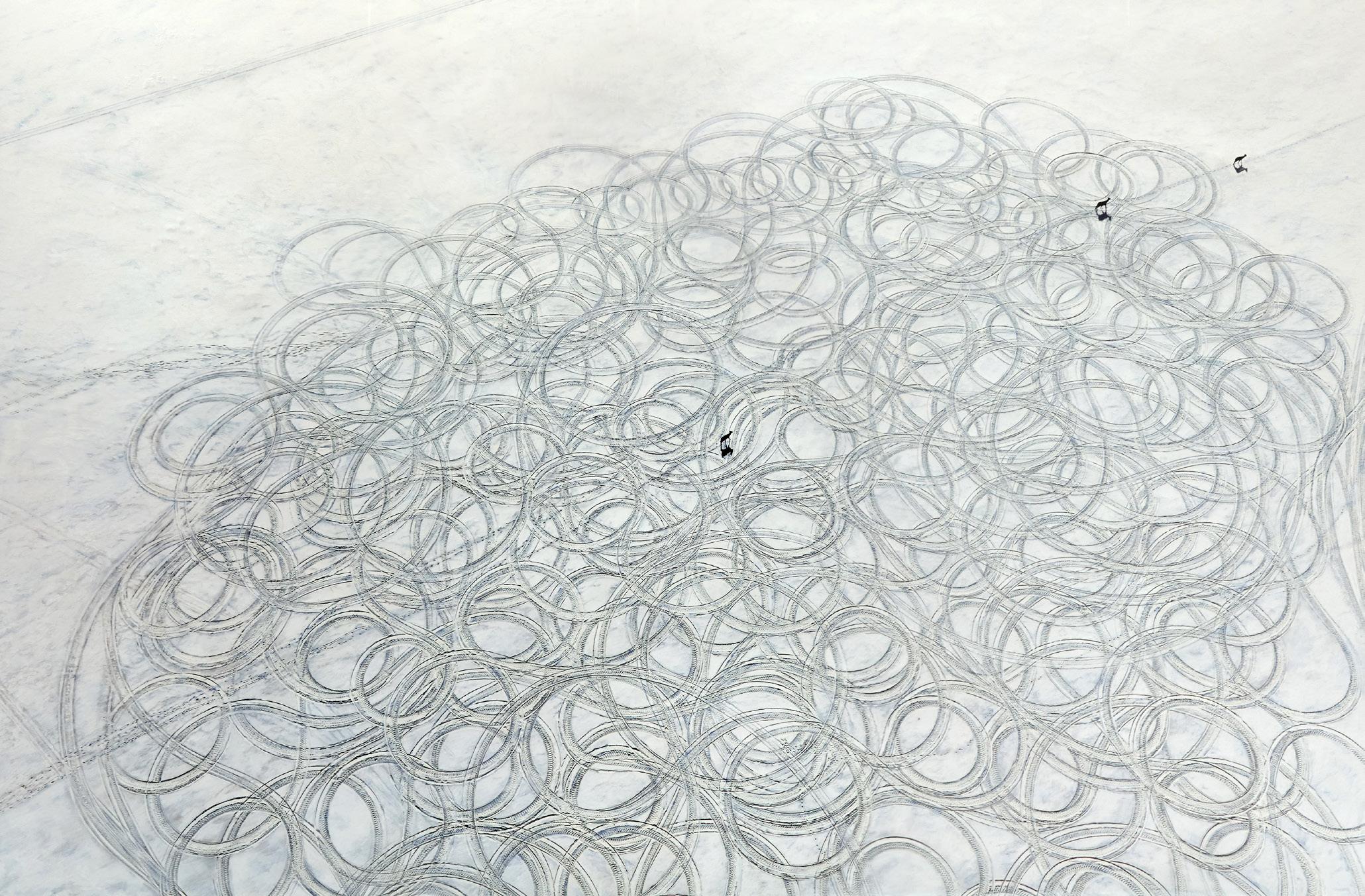

14. Laura Millard

Crossing I, 2017

digital print on Hahnemuehle paper with graphite, gouache and chalk 44 x 66.5 ins (111.8 x 168.9 cms)

This remarkable image was made at Three Mile Lake in the Muskoka Lakes region north of Toronto. That it is a drawing over a drone photograph begins to suggest its innovativeness, as does the fact that the interlacing circles on the frozen lake were inscribed by Millard with a snowmobile. The inevitable racket of producing this ephemeral pattern contrasts profoundly with its stillness as an image, an evocative silence claimed by the deer—captured serendipitously by the drone camera—as they purposefully cross the lake in a straight line. Crossing I makes an environmental point. In Millard’s words, “I am interested in the contrast between the orderly movement of the deer against the chaotic path of the Skidoo and how it reverses our assumptions of the rational human and the wild animal.”

15. Maureen Gruben

Untitled (Sled), 2023 salvaged sled, clay and acrylic paint

33 x 14.5 x 6.25 ins (83.8 x 36.8 x 15.9 cms)

Maureen Gruben grew up and now works in Tuktoyaktuk, on the Arctic Ocean in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories. Her parents were traditional Inuvialuit knowledge keepers, a culture she maintains through works such as Untitled (Sled). She has arranged and photographed modern, working versions of the qamutiiks (sleds) not unlike those we see in A.Y. Jackson’s painting (no. 5).

But this sculptural example is different because it has been built up from a toy sled, an armature that Gruben salvaged—as she often does— from her local landfill site. The work is literally recycled, an environmental priority she embraces and also a metaphor for the reappearance of this Inuit invention in miniature. Without picturing a landscape, this work is very much about land, its uses and preservation. Gruben maintains the original’s playfulness in an art world setting by placing the toy on a plinth and reconstituting its surface to give it the appearance of a ‘serious’ bronze sculpture.

Courtesy of the artist and Cooper Cole, Toronto.

16. Tristan Duke

Life Boat at Dahlbreen Glacier, Svalbard 02, 2022

ice lens photograph, pigment print signed and numbered 1/5 in the lower margin

42 × 60 ins (106.7 × 152.4 cms)

17. Tristan Duke

Palisades Fire, California 03, 2025

ice lens photograph, pigment print

signed and numbered 1/5 in the lower margin

42 × 60 ins (106.7 × 152.4 cms)

Analogue photography is inevitably a recreation, a ‘fixing’ of momentary light conditions. Tristan Duke takes the self-referentiality of this material fact further by fabricating his photographic lenses from the same glacial ice that he photographed while on the Arctic Circle Residency Program in Svalbard in the summer of 2022. In a material and an elusive, haunting sense, he is photographing ice with ice. The ice is creating a pictorial autobiography. The wet surfaces of his ice lenses betoken melting glaciers, yet ironically, without the clarity of this liquid surface, his photographs would not be successful.

Life Boat at Dahlbreen Glacier, Svalbard 02 is an image of everyday transport to and from the expedition ship Antigua. Yet the global climate emergency might make us think of climate refugees or of an immediate maritime crisis. Duke asks, “is this the rescue party or the ones in need of rescue?” And where is the pilot heading? This question could be extrapolated to the Arctic and the planet.

Not content to show us the climate crisis in the far north alone, Duke has also photographed fires with ice lenses. Here he materializes two bold ideas: the first lenses used for starting fires were made of ice by Zhang Hua in third-century China. Today, the climate disruption experienced at the poles is also responsible for the increased frequency of fires worldwide.

16.

17.

18. Laura Millard

Motion Lamp 3, Svalbard, 2024 refurbished vintage motion lamp, photograph and collage on backlit film 12 x 6 (diameter) ins (30.5 x 15.2 cms)

Laura Millard was part of an invited group of artists and scientists on the Arctic Circle Alumni Residency in the Arctic Archipelago of Svalbard in the summer of 2024. These islands at 82 degrees north are heating more quickly than anywhere else on the planet, with a dramatically negative effect. Among Millard’s reckonings with this reality is a suite of motion lamps that combine her photographs of disappearing glaciers with lamps that rotate thanks to heat convection from their bulbs. Popular in the mid-twentieth century as mementos of tourist sites such as Niagara Falls, Millard reconstitutes the lamps themselves and what they show to underline the increase in global temperatures in the increasingly touristic far north. People watch this happening in her images, but as in Crossing 1, we humans are turning to climate issues too slowly, even pointlessly ‘going in circles.’ The lamps seem as poignantly fragile as the ecologies they present.

Acknowledgements

My first and last thanks are to Lydia Abbott, Project Coordinator, who gave me the opportunity to curate this exhibition at Cowley Abbott and who has been the most gracious, insightful, and industrious collaborator. Thanks too to Rob Cowley for his enthusiasm for this project and to Patrick Staheli and Sierra Bailey for producing the accompanying catalogue. My thanks to the private collectors who so generously lent their work and to the contemporary artists and their representatives who have supported Ideas of Far North. I am especially grateful to Tristan Duke, Laura Millard, and Paul Walde for ongoing discussions about their work and attendant issues. Special thanks to Elizabeth Harvey, who has considerable expertise with ideas of the far north and has heard more about my plans than anyone.

About the Curator

Mark A. Cheetham is the author of books, volumes, articles, and exhibitions on abstract art, Immanuel Kant and art history, postmodernism, and many contemporary artists. His current research and curating focus on ecological art and word-image interfaces in 19th-century publications on Arctic voyaging. He is preparing the exhibition Arctic Fever: Image and Narrative in North Circumpolar Voyaging in the Long 19th Century (Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, January–April 2026). Cheetham is a Guggenheim Fellow, a Clark Art Institute Fellow, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto.

Notes

1A.Y. Jackson’s book is included in this exhibition (no. 3). For Glenn Gould, consult https://www.cbc. ca/radio/ideas/glenn-gould-idea-of-north-radio-documentary-1.6682765.

For Steve Martin, consult https://hammer.ucla.edu/exhibitions/2015/the-idea-of-north-thepaintings-of-lawren-harris.