DANCE, HEALTH AND WELLBEING

People Dancing Summer Intensive. Photo: Andrew Moore.

I

AM HERE, I AM WHOLE, I BELONG

Yaël

Owen, Deputy CEO and Head of Health & Wellbeing at People

Dancing introduces this timely collection of informative, inspiring, and current writing across dance, health, and wellbeing...

At a time of rapid growth in community and participatory dance practice firmly rooted within the field of Creative Health this collection of articles captures the rich thinking, reflections, and practice of community artists, academics, policy creators and researchers shaping the ways in which we approach this work and what it means for the communities we work with.

The writers included in this special focus come from all across the UK, united by a shared passion and belief in the value of dancing and its power to enhance wellbeing. They reflect how dancing can make us feel better not just as individuals, but as a society, offering not only connection, expression, and joy, but pathways to equity and inclusion.

Dr. Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt helps to contextualise the place of dance and how it features in the current evolving landscape of arts and health, and Victoria Hulme Executive Director of the Culture Health & Wellbeing Alliance considers the power of Creative Health to point us to a fairer society.

Welsh community dance practitioner and lecturer at Cardiff Met University, Heidi Wilson reflects the place of ‘love’ within community dance practice, Dr. Bethany Whiteside, Senior Lecturer at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland shares an emerging, participant co-created approach to dance research. From Northern Ireland, Dr. Anna Carapellotti and her

dance with Parkinson’s group reflect on seven glorious years of dancing together.

Julie McCarthy and Daniel Fulvio write about a unique collaboration to support school readiness and creativity in early years settings across Greater Manchester and Dr. Sue Smith, Falmouth University and Chair of People Dancing considers creating the conditions for healthy risk taking with students. The impact and joy of African Holistic Dance with communities in the Midlands is explored by Birmingham based Sandra Golding and finally, Dr. Kathryn Stamp and Dr. Noyale Colin tell us about the development of their publication, Dancing, a guide to working in dance, health & wellbeing.

From the breadth of this writing, we can conclude that the field of Creative Health – a term adopted via an open competition to name The Inquiry Report Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing (2017) - remains complex and evolving, shaped by an intricate and interconnected ecosystem of organisations, people, practices, and ideas.

We offer this collection of writing underpinned by this complexity; as a celebration of how far the work has come specifically across participatory dance practices but in the knowledge that there is still so much more to learn, clarify, embed and develop.

This is no better exemplified than by Penny Greenland, MBE, in an article written for Animated in Spring 2005, the wonderfully titled We Can Do Hard Things and I would claim it is still as important and relevant today as it was exactly 20 years ago.

In the context of 2005, when many dance practitioners were already working within the health sector, Penny, founder of Jabadao (1) highlighted the complexities not only of working in health settings but also within dance itself, noting that “dance is not one practice, but many different ones.” (2)

And her writing serves as a call to action for the clearer articulation and greater specificity in naming the breadth of dance practices in action within and across the health and wellbeing space, with dance practitioners taking the lead. For, Penny argues, by more clearly defining what we do and what we do well we can help the health sector in better understanding, navigating, and integrating our work to support better equity, opportunity and outcomes for people in physical and mental health and in promoting overall health and wellness.

‘But at this point, we the practitioners, must take the initiative, articulate our practices, and identify our partners. Sort ourselves out. (3)

It is our aim that the launch of our new Dance, Health & Wellbeing network might go some way to support Penny’s still relevant call to action. Here we will create space for continued learning, connecting, collaborating and advocating, led by the needs and

Photo: Chris Stenton.

Live Well & Dance with Parkinson’s, Northeast. Photo: Rachel Cherry. challenges of practitioners working across the sector. And I am delighted we will be joined by Kathryn and Noyale to share more about their book.

So we hope this series of articles focused on dance, health, and wellbeing, alongside partners, participants, collaborators, advocates, and networks, can also help us continue to ‘sort ourselves out’! Because, in the end, I sense what we all really want for our communities, our participants and ourselves is the recognition we do this work well, and to share across the complexities of the ecosystem how dancing together with others brings immense joy, creativity and a complete sense of wellbeing.

As Sandra Golding writes in her article Dancing our Way Home, ‘To feel joy in the body is to declare, even in the face of adversity: I am here, I am whole, I belong.’

Information about each author and their work can be found at the end of their articles.

References

1. https://www.jabadao.org

2. Greenland, P, Animated, Spring 2005, ‘We can do hard things’, p.31

3. Greenland, P, Animated, Spring 2005, ‘We can do hard things’, p.32

People Dancing Summer Intensive. Photo: Andrew Moore.

DANCE IN HEALTH AND WELLBEING: PRACTICE, RESEARCH AND POLICY

Where does dance feature in the evolving landscape of arts and health? Dr. Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt, research lead and author of the seminal report Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing, traces the development of dance within creative health, considering its contribution to wellbeing across many communities, and the potential of the arts to support health, wellbeing and equity for everyone.

Practice

It is difficult to know where to begin this story, as acknowledgement of the health benefits of the arts dates back to antiquity. (1) In the early modern era (17367), William Hogarth brought the arts into the healthcare environment by painting biblical scenes on the walls of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. In late modernity (1859), Florence Nightingale observed that the ‘variety of form and brilliancy of colour in the objects presented to patients are actual means of recovery’. In 1942, artist Adrian Hill coined the term ‘art therapy’ to denote the harnessing of health impacts. The late 1950s saw the birth of Paintings in Hospitals, which continues to loan artworks to health and care organisations. The early 1970s saw visual art graduates in Manchester rejecting

the market in favour of site-specific works in healthcare settings, (2) and the second half of the decade saw dance artist, Gina Levete offering dance workshops to disabled children and then adults across London and the rest of the UK through Shape Arts.

In late 2024, the Mayor of London published a report I had written, based on research undertaken in collaboration with London Arts and Health called Understanding Creative Health in London: The Scale, Character and Maturity of the Sector. The report captured the evolution of creative health approaches since Hogarth’s time in metropolitan health, care, culture, heritage and community settings. Two timelines – beautifully visualised by artist Rae Goddard – include, for example, the inception of the Carl Campbell Dance Company in 1978, Academy of Indian Dance (now Akademi) in 1979, Adzido Pan African Dance Ensemble in 1984, Green Candle Dance Company in 1987 and Sadlers Wells’ Company of Elders in 1989, collectively extending the benefits of dance to health and wellbeing. People Dancing’s website is replete with examples of present-day dance practice directly and indirectly enhancing health and wellbeing throughout life.

Research

In parallel with the growth of practice, the evidence base for the health and wellbeing benefits of dance has been expanding to encompass a range of methods. In the United States in 1968, an early workshop of dance therapists, movement researchers and clinicians considered the mental health benefits of dance. (3) In the 1970s and ’80s, US researchers advocated dance as a resource vital to the physical and mental wellbeing of older adults (4) as part of a holistic approach. (5)

In the UK, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance was an early entrant into the field of dance, health and wellbeing research. A review of research articles published over the first two decades of the new millennium found dance making contributions to health and wellbeing across seven domains: embodiment, identity, belonging, self-worth, aesthetics, affective responses and creativity. (6)

A significant portion of the evidence base for dance, health and wellbeing is centred on the role of dance and movement in promoting physical activity and fitness. (7) Adjacent research highlights the contribution of dance to social connectedness, mental health, wellbeing and quality of life, (8), including in people with chronic conditions. (9) A considerable body of work has been dedicated to the integration of movement and cognition. (10) In children, a link has been discerned between dance, literacy and reading comprehension. (11) In people with dementia, multiple positive effects have been observed via engagement with dance. (12)

A contested area in the literature relates to dance and falls prevention. An early randomised controlled trial (the gold standard of empirical health research) suggesting that ballroom dancing among care home

Photo: Mae London.

residents improved balance and reduced the number of falls in the study population. (13) However, a 2024 review of 41 previous studies found little evidence that dance could help to reduce falls. (14) More encouraging results have been seen in relation to fear of falling, coordination, mobility, stamina and social relations. (15,16).

In 2023, the Sport and Recreation Alliance calculated the social value of movement and dance activities, attributing the highest value (£2 billion p.a.) to an uplift in mental health and wellbeing for participants and volunteers. (17) Further social value was observed in reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes (£157 million) and in diminishing the risk of developing dementia (£149 million), with significant value also seen in relation to cardiovascular disease/stroke (£45 million) and hip fractures (£39 million) as well as in reduced demand for psychotherapy services (£28 million) and GP visits (£19 million).

Research has consistently shown that dance helps to improve clinical signs and provides holistic benefits to people with Parkinson’s Disease. (18, 19) At King’s College London, the Scaling-up Health Arts Programmes: Implementation and Effectiveness Research (SHAPER) project explored Dance for Parkinson’s, run by English National Ballet since 2010, finding that dance can lead to improvements in pain and symptoms in people with Parkinson’s. Alongside this, People Dancing’s project, Live Well & Dance with Parkinson’s, was centred on participatory dance practice across six areas in England, celebrating the joy of people dancing together, community development and lived experience leadership. (20) SHAPER also examined Rosetta Life’s Stroke Odysseys, a dancebased programme for adults recovering from acquired brain injury, an approach known to be particularly relevant to people recovering from a stroke. (21)

Policy

As practice and research advanced, various discussion forums arose, with attention initially focused on the arts in healthcare settings. For Understanding Creative Health in London, we were able to provide an overview of nationally significant convergences. Pertinent among these was a collaboration between the Department of Health and Arts Council England, which, in 2007, gave rise to A Prospectus for Arts and Health, paving the way for future collaboration.

While negative publicity curtailed this promising joint initiative, one parliamentarian was not prepared to allow momentum to be lost. Former Member of Parliament and Minister for the Arts Lord Howarth of Newport continued to advocate for recognition of the health and wellbeing benefits of the arts. At a meeting with members of the National Alliance for Arts, Health and Wellbeing, Lord Howarth offered to set up an All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Arts Health and Wellbeing, which he did in 2014. The following

year, the group initiated an inquiry into the health and wellbeing benefits of the arts, to which I was recruited as Researcher from a base at King’s College London. The inquiry convened a series of specialist meetings and 16 roundtables in Parliament, on themes as wideranging as young people’s mental health, dementia, palliative care, dying and bereavement. My task was to bring oral testimony from the APPG meetings together with the most compelling evidence and examples of practice.

Seven years before the parliamentary inquiry began, in 2008, the World Health Organisation had published the results of a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, chaired by Professor Sir Michael Marmot. (22) This had identified profound health inequalities between and within countries, due to the uneven distribution of power and resources. In 2010, Marmot had built on this to publish Fair Society, Healthy Lives, commissioned by the Secretary of State for Health, which applied this thinking to the UK and made recommendations for targeted work to improve the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age – collectively known as the social determinants of health. (23) The arts were conspicuous by their absence from both reports.

Addressing this omission during the APPG inquiry, we persuaded parliamentarians to acknowledge the potential contribution of the arts to tackling health inequalities. Accordingly, I adopted a social determinants framework and arranged my findings across the life course to produce a substantial report, which was published in 2017. (24)

The title of the inquiry report – decided via an open competition – was Creative Health, which has been widely taken up as the current name of the arts and health movement. From a policy perspective, one of the major successes of the Creative Health report has been that discussion of the arts in relation to the social determinants of health is now commonplace.

Dance featured throughout Creative Health, in relation to early childhood development, educational attainment, Parkinson’s, recovery from surgery, rehabilitation from brain injury and improved physical and mental health and wellbeing in people of all ages. Building on evidence that dance and movement activities delayed cognitive deterioration while reducing challenging behaviours, improving mood and enhancing quality of life, the report highlighted examples of practice that realised the value of dance to people with dementia. The inquiry report also evidenced multiple indirect benefits of dance, including selfexpression, communication, creative capacity and social and emotional capabilities.

A case study within Creative Health was devoted to the Alchemy Project, a research collaboration between Dance United and the early intervention in psychosis team at South London and Maudsley Hospital, with input from King’s College London. The 18- to 35-year-olds taking part demonstrated clinically

significant improvements in wellbeing, communication, concentration and focus, level of trust in others, team working and quality of life.

Progress is being made against each of the ten recommendations made in Creative Health, notably the inception of the National Centre for Creative Health (NCCH) and Arts Council England’s support of arts and cultural organisations with health and wellbeing outcomes. Collaboration between these organisations led to creative health associates being hosted within each of the seven NHS regions in England between 2023 and 2025. A similar scheme, operated by the Greater London Authority in partnership with local government, saw a creative health lead being appointed by South East London Integrated Care Board.

In 2023, the All-Party Parliamentary Group published the results of a review of the benefits of creative health, which outlined a vision of the arts as ‘integral to health, social care and wider systems, with creativity recognised by the general public, healthcare professionals and policymakers as a resource to support health and wellbeing’. (25) The following year, the group was renamed the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Creative Health.

Regional progress

In addition to making recommendations to central government, the Creative Health Review identified the importance of devolved government in developing local strategies. As such, the review advised ‘that Metro Mayors consider how their devolved powers can support creative health in their region and work in partnership with ICS (Integrated Care System) leaders

to deliver coherent strategies and develop sustainable creative health infrastructure at scale using local assets’. This has led to the formation of the Metro Mayors’ Creative Health Network to share knowledge and drive progress.

A founder member of the network, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, had previously commissioned me to work closely with the local ICS to develop a dedicated Creative Health Strategy, which was published at the end of 2022. (25) This strategy highlighted the benefits of dance to early childhood development and detailed dance workshops for NHS staff coordinated by Lime Arts. Adopting a life course approach, the strategy advocated dance during working-age and older adulthood, drawing on the expertise of such local organisations as Company Chameleon and Global Grooves.

Throughout 2023, another founder member of the Metro Mayors’ Creative Health Network, the Greater London Authority, convened a discursive policy-design process that involved the sector and people with lived experience, celebrated the capital’s diversity, and considered ways in which creative health might be embedded in the community beyond health and care systems. Having evaluated the policy-design process, in 2024 I partnered with London Arts and Health to conduct a thorough scoping of the creative health sector in the capital. This comprised an overview of settings alongside a snapshot of practice, workforce, funding and commissioning, resulting in the aforementioned report Understanding Creative Health in London.

For the early months of 2025, another network member, the West Midlands Combined Authority, invited

People Dancing Summer Intensive. Photo: Andrew Moore.

me to undertake an analysis of creative health activity, research and data in the region. The internal report I drafted noted Coventry’s advocacy, during its year as UK City of Culture in 2021, of the promotion of physical activity through dance as one of five step changes. My report also recorded the presence of a dancer in residence at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, workshops being offered by Birmingham Royal Ballet to people of all ages, an elders’ contemporary dance company at Warwick Arts Centre and a Somatics and Pain Network at Coventry University, working with dance to support people living with chronic pain. Dance featured prominently among regional organisations funded by Arts Council England identified as pursuing creative health approaches.

West Yorkshire Combined Authority is in the process of procuring a consortium to develop and deliver a regional creative health strategy, with other network members likely to follow suit.

Into the future

In the coming years NCCH creative health associates, embedded in every ICS in England, will be pivotal to ensuring that the arts are more fully integrated into the NHS.

In the community, we are going to see more creative health regions, cities and boroughs being established and more dedicated work happening in our neighbourhoods that draws out the health and wellbeing benefits of creativity, culture and heritage. (this is a good one) My hope is that the integration of creative health approaches becomes less subject

to a postcode lottery and that every library, community centre, school and college up and down the country offers creative health activities. At the same time, the creative health workforce and leadership will come to be more representative of the communities they serve.

For me, the biggest untapped potential of creative health is recognition of its role in increasing equity. Following on from the hypothesis advanced in Creative Health, more research is needed into the relationship between the arts and the social determinants of health. Findings from this research will then need to be implemented in practice, with resources being invested according to the Marmot principle of proportionate universalism, on a sliding scale according to need. Only when the benefits of creativity, culture and heritage are equitably distributed – and socioeconomic gaps in health and wellbeing narrowed – will the full potential of creative health be realised.

After this article was written, we very sadly lost Alan Howarth, Lord Howarth of Newport, a great parliamentary and personal champion of creative health. Alan’s memoir – Begun, Continued – will be published on 10 October 2025. His legacy in the sector will live on.

References

1. See, for example, Arcangeli, A. (2020). ‘Dance and Health: The Renaissance Physicians’ View’. Dance Research. Volume 18, Issue 1, pp. 3–30. doi: 10.3366/1291009

2. Now Lime Arts, operating under the auspices of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

People Dancing Summer Intensive. Photo: Andrew Moore.

3. Bird, B. (1968). ‘The Workshop on Dance Therapy: Its Research Potentials’. CORD News. Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 8–9. doi: 10.2307/1477685

4. Helm, JB & Gill, KL. (1975). ‘An Essential Resource for the Aging: Dance Therapy’. Dance Research Journal. Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 1–7. doi: 10.2307/1478650

5. Fersh, IE. (1980). ‘Dance/movement therapy: A holistic approach to working with the elderly’. American Journal of Dance Therapy. Volume 3, pp. 33–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02579617

6. Chappell, K, Redding, E, Crickmay, U, Stancliffe, R, Jobbins, V & Smith, S. (2021). ‘The aesthetic, artistic and creative contributions of dance for health and wellbeing across the lifecourse: a systematic review’. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. Volume 16, Issue 1. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2021.1950891

7. Fong Yan, A, Cobley, S, Chan, C. et al. (2018). ‘The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Physical Health Outcomes Compared to Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Sports Medicine. Volume 48, pp. 933–951 doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0853-5

8. Salihu, D, Kwan, RYC, Wong, EML. (2021). ‘The effect of dancing interventions on depression symptoms, anxiety, and stress in adults without musculoskeletal disorders: An integrative review and meta-analysis’. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. Volume 45. doi: 10.1016/j. ctcp.2021.101467.

9. Wshah, A, Butler, S, Patterson, K, Goldstein, R, Brooks, D. (2019) ‘“Let’s Boogie”: Feasibility of a Dance Intervention in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease’. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. Volume 39, Issue 5, pp. E14–E19. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000428.

10. Bläsing, B, Calvo-Merino, B, Cross, ES, Jola, C, Honisch, J, Stevens, CJ. (2012). ‘Neurocognitive control in dance perception and performance’. Acta Psychologica. Volume 139, Issue 2, pp. 300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.12.005.

11. Makopoulou, K, Neville, R & McLaughlin, K. (2020). ‘Does a dance-based physical education (DBPE) intervention improve year 4 pupils’ reading comprehension attainment? Results from a pilot study in England’. Research in Dance Education. Volume 22, Issue 3, pp. 269–286. doi: 10.1080/14647893.2020.1754779

12. Mabire, J-B, Aquino, J-P, Charras, K. (2019). ‘Dance interventions for people with dementia: systematic review and practice recommendations’. International Psychogeriatrics. Volume 31, Issue 7, pp. 977–987. doi: 10.1017/ S1041610218001552

13. da Silva Borges, EG, de Souza Vale, RG, Cader, SA, Leal, S, Miguel, F, Pernambuco, CS, Dantas, EH. (2014). ‘Postural balance and falls in elderly nursing home residents enrolled in a ballroom dancing program’. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Volume 59, Issue 2, pp. 312–316. doi: 10.1016/j. archger.2014.03.013.

14. Lazo, K, Yang, Y, Abaraogu, U, Beyer, FR, Eastaugh, C, Norman, G & Todd, C. (2024). ‘Effectiveness of dance interventions on falls prevention in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis’. Age and Ageing. Volume 53, Issue 5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afae104

15. Veronese, N, Maggi, S, Schofield, P, Stubbs, B. (2017). ‘Dance movement therapy and falls prevention’. Maturitas.

Volume 102, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.05.004.

16. Vella-Burrows, T, Pickard, A, Wilson, L, Clift, S, & Whitfield, L. (2019). ‘“Dance to Health”: an evaluation of health, social and dance interest outcomes of a dance programme for the prevention of falls’. Arts & Health. Volume 13, Issue 2, pp. 158–172. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2019.1662461

17. Sport and Recreation Alliance. (2023). Social Value of Movement and Dance.

18. Pereira, APS, Marinho, V, Gupta, D, Magalhães, F, Ayres, C, Teixeira, S. (2018). ‘Music Therapy and Dance as Gait Rehabilitation in Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Review of Evidence’. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. Volume 32, Issue 1, pp. 49–56. doi: 10.1177/0891988718819858

19. McGill, A, Houston, S, Lee, RYW. (2014). ‘Dance for Parkinson’s: A new framework for research on its physical, mental, emotional, and social benefits’. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. Volume 22, Issue 3, pp. 426–432.

20. https://www.communitydance.org.uk/what-we-do/live-welland-dance-with-parkinsons

21. Morice, E, Moncharmont, J, Jenny, C, et al. (2020). ‘Dancing to improve balance control, cognitive-motor functions and quality of life after stroke: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial’. BMJ Open. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037039

22. World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Final report of the commission on social determinants of health.

23. Marmot, M, Allen, J, Goldblatt, P, Boyce, T, McNeish, D, et al. (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives – The Marmot Review: Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010.

24. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. (2017). Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing.

25. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing and National Centre for Creative Health. (2023). Creative Health Review: How Policy Can Embrace Creative Health.

Info

Dr Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt has worked in Parliament and with the Greater London Authority, Greater Manchester Combined Authority, London Arts & Health and many universities, trusts and foundations. She drafted the parliamentary report that gave the Creative Health movement its current name, and she has done much to advance the argument that creative-health approaches can increase equity. www.rebeccagordon-nesbitt.org/

“Creative Health is always part of a bigger picture. The long histories of participatory practice that underpin Creative Health are rooted in the idea of building a fairer society.”

Wanna Dance? (Cheshire Dance). Photo: Abbigale Blake 2023. Below: Victoria Hume. Photo: @inspiredmaephotography.

Executive Director of the Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance, Victoria Hume reflects that the real power of Creative Health is “not in its ability to distract us from pain or difficulty, but in the ways in which it can help us see what is really going on.”

It’s a strange, contradictory time in creative health at the moment. In many ways our broader culture has moved towards the idea that creativity supports our health; the government is talking about the kind of ‘neighbourhood’ healthcare that fits well with creative approaches and “community assets” like museums and heritage sites. There is more widespread acceptance of well-evidenced impacts on our health and wellbeing – and we are starting to see clearer evidence of the knock-on cost savings for health (1). A real sea change has occurred in the last few years with the beginnings of infrastructure roles for creative health – creative health leads and associates – and more joint working between culture and health within local authorities.

All this is happening despite changes that on paper should be devastating the sector. Years of cuts to culture budgets, an NHS a state of perpetual privation and rearrangement while social care limps on, unreformed. But what we do have, across the UK, is a sustained commitment from our arts councils to creative health. Our Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA) surveys between 2021 and 2023 shared that the UK’s arts councils became the biggest funder of creative health initiatives, overtaking independent Trusts and Foundations. In England, Arts Council England (ACE) funding is behind much of the limited – but growing – infrastructure of creative health, whether through the National Centre for Creative Health or the Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance, London Arts and Health, the Mayoral Creative Health Network, the National Arts in Hospitals Network (2), or partnerships with local authorities.

We can see the drain of funds from our public institutions as symptomatic of a wider malaise, but this support is symptomatic of something, too – of progressive forces finding space inside our institutions to drive systems change with intelligent, often small investment that unlocks something larger. You can see this in South Yorkshire, for example, where four local authorities, the mayoral authority and ACE have come together – committing both their collective intelligence and (small) financial investments to a new Creative Health Board and Lead. This will start to build a scaffolding for freelancers, small organisations and larger providers across the region to meet health and social care on equal terms.

This kind of small-scale collaboration is as much about the intent to work across structures as it is about the actual money set aside.

When the Labour government first came to power, the new Culture Secretary, Lisa Nandy, envisaged a new era of cross-departmental working as she announced that she would sit on all of Labour’s five Mission Boards and that culture would be threaded through everything from crime prevention to health (3).

This early optimism seems not to be carrying through in documents like the Creative Industries Plan, which doesn’t overtly mention health. And yet… there is another change that gives grounds for optimism, and new ways of connecting with the budgetary support this might unlock: Creative Health is far better aligned with questions of wider social change than it once was.

To quote the Creative Health Quality Framework: “Creative Health is always part of a bigger picture.

Eline Kieft (tutor), People Dancing Summer Intensive 2025. Photo: Andrew Moore.

“Creative Health is always part of a bigger picture. The long histories of participatory practice that underpin Creative Health are rooted in the idea of building a fairer society.”

The long histories of participatory practice that underpin Creative Health are rooted in the idea of building a fairer society.”

We’ve moved from discussions of the arts as a top-down dose that distracts or palliates to considering creativity as a way of being in the world that gives us a measure of control over our own wellbeing. Another important part of this is de-centring this work: we are not a silver bullet in competition with other movements but we have the capacity to be part of, influencing and influenced by, wider networks.

This way of being is about developing both our agency and our ability to find community.

Or perhaps about finding our own place in the world, not just by describing endlesslessly and solipsistically in increasingly old-fashioned-seeming social media posts, but through relationships and empathy – with ourselves, with others, with nature. This shift is essential to claims that creativity and the culture sector are critical to tackling health inequalities.

We are living in a time of dissociation: the schism between what we hear in politics, between what is described as reasonable, and the various violences we see unfolding around us, widens all the time. Specifically, a clampdown on dissent and peaceful protest in this country (4) is having a deadening effect on our ability to say what we see.

“By emphasising a person-centred, equitable approach to practice, the Quality Framework is intended to support work that reveals and challenges inequities and supports positive action.”

The key word here is perhaps ‘reveals’. The real power of creative health is not in its ability to distract us from pain or difficulty, but in the ways in which it can help us see what is really going on – a gesture which gives power and visibility to people from whom it has been taken away.

Cheshire Dance’s Wanna Dance programme –shortlisted for this year’s CHWA Awards (5), works with people with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities (PIMD), “based on the principles of joining, amplifying and connecting one-to-one with a partner’s movement” (6).

This empathic approach makes visible an experience of life that is often totally hidden; and by embedding

dance artists in staff teams, the approach opens up the possibilities for communication across the whole working culture.

Likewise the Gloucestershire-based charity Music Works, winner of the Collective Power award, are trasforming mental health by opening up spaces for the truths of young people’s experiences, equipping them with the skills and, crucially, the confidence to tell their own stories. The stories of Wanna Dance, or of Music Work’s Knife Angel programme, pull our collective consciousness towards a place grounded in reality.

As one of the artists involved says, “refresh your brain” (7). In this way these small creative gestures change everything, for all of us.

We believe strongly that the creative practitioners and organisations making this happen need proper support. This means long-term financial support, wellbeing support, leadership training, peer-to-peer learning. There is so much astonishing work being done already, and CHWA’s job, along with many others, is to open up the landscape around these roots, so that they can spread and grow.

References

1. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/678e2ecf432c55fe2988f615/rpt_-_Frontier_Health_ and_Wellbeing_Final_Report_09_12_24_accessible_final.pdf

2. See our recent event What’s the National Picture in Creative Health? (21 May 2025) https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=HiiqCoO45xQ

3. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/news/blog/ new-government-interested-creative-health

4. https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/uk-alarmingcrime-and-policing-bill-yet-another-assault-right-peacefullyprotest

5. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/get-involved/ chwa-awards-2025

6. https://www.cheshiredance.org/groups_and_projects/ wanna-dance/

7. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQ4qKfLXMAM

Info

Victoria Hume is Executive Director of the Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA) www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/

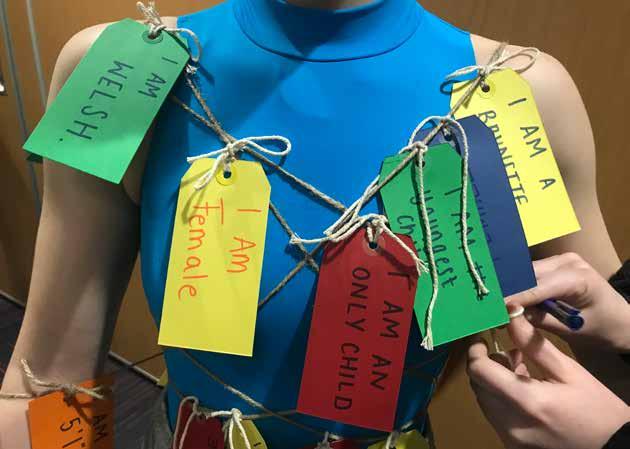

FLOURISH: IDENTITY, BELONGING AND CONSENT-FORWARD DANCE IN HE

Dr Sue Smith considers the imperative to create and establish healthy learning and practice cultures that support dance students in Higher Education – our future dance workforce – to flourish and “be present, be brave and take risks”.

Photo: Sue Smith.

Falmouth University: Luis Moore & Amy Wiliams Photo: Steve Tanner.

In this piece I want to acknowledge some of the current challenges around student wellbeing in Higher Education. Many of us working in universities are increasingly focused on ensuring that we create and establish healthy learning and practice cultures that support our students to flourish, signposting to other vital services when needed. (1)

Here at Falmouth University, where I am Course Leader for Dance and Choreography, our commitments to ‘healthy’ and ‘safe’ practice challenge us to interrogate the conditions for a dance pedagogy that acknowledges, and seeks to mitigate, the increasing risks to student mental health. In this article I will share some thoughts on the complexity of this challenge as well as an example of how we are addressing a need for more transparent working practices that articulate our principles for dancing together.

This process is called Flourish.

As would be expected, we take time to carefully create and deliver dance practices in technical, theoretical and creative modules that we consider to be safe and empowering. We couldn’t do our work successfully if we didn’t have confidence in this. Contact improvisation, partner work, or exploring the human condition as student artists, for example, would be impossible without robust, reflexive processes for navigating the terms of participation. While we prioritise student experience in this way, mental health remains a concern across the HE sector.

A survey from Student Minds (2023) (2) revealed that 57% of student respondents reported a mental health condition and that 27% had a diagnosed condition.

Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) (2025) (3) data tells us that in 2015 only 2% of students reported a mental health condition. These figures are startling, painting a picture of increasing pressures on young people in university, with socio-economic background, Covid and neurodiversity key risk factors for poor mental health. Economic precarity and debt burden also play a significant role in increased student stress University College Union (UCU) (2025).

These concerning statistics are read alongside a proliferation of research of the positive effects of dance on health and well-being. How do we as dance educators in HE consider this paradox in our settings? How can the potent health and wellbeing contributions of dance co-exist and intersect with the demands of higher education on young people? How can we build cultures of supportive practice that also afford the measurement of academic achievement?

In the 2021 article, the aesthetic, artistic and creative contributions of dance for health and wellbeing across the lifecourse: a systematic review, Chappell et al (4),

articulated seven interrelated contributions that dance makes to Health and Wellbeing: embodiment, identity, belonging, self-worth, aesthetics, affective responses and creativity.

These contributions to health will resonate with many of us working in community dance settings. I am reflecting on how these contributions are supported in a university dance course context and specifically how aspects of belonging, self-worth and identity can be activated to support better mental health. ‘Developing a new social identity’ was listed as one of the key stressors for students in a 2025 National Institute for Health and Care Exellence (NICE) report (5).

Of course, there are differences between community dance projects designed for distinct social or health outcomes and the teaching/learning context on a degree course: the staggering financial investment, the time scale of engagement, the shadow of master teacher paradigms that exist in many technical contexts. In our departmental team, questions of supporting individual academic attainment and balancing challenge, curiosity and empowerment remain live. How do we support our students, as a future dance workforce, to do their best work through cultivating healthy technical and creative practices that are also aware of and articulate expressions of identity and belonging?

With these issues in mind, at Falmouth University, we have developed Flourish: a process of consultation to agree some principles for dance practice with students. Its intention is to support students to understand their agency and our collective responsibilities and to shape a live document that outlines how we want to study and dance together. I am reminded of Fiona Bannon’s (2012) prescient work on Relational Ethics in HE dance as I consider how issues and ideas of consent are intrinsically linked to student well-being and underpin empowered decision-making. Flourish foregrounds the importance of individual agency…what conditions need to be in place to work safely and ‘well’ and to enable us to take the risks we want to take?

This is especially challenging when modules are also encouraging students to be innovative, experimental and bold: in other words, to work outside their comfort zone. We choose to explore ideas of boundaries, consent and what it means to be daring or risky in a learning culture that is increasingly charged with issues of identity, vulnerability and sensitivity to/comfort with certain content. To borrow a phrase from the emerging field of Intimacy Co-ordination (6) these practices need to be ‘consent-forward’. It is never perfect though and situations do arise that are challenging. It is useful to be reminded that no space is ever risk-free and that we >>

can never create completely safe spaces, but Flourish helps us to support students to, ‘be present, be brave and take risks’, a position Kristin Horrigan outlines in her 2024, Integrating Consent Practice in Dance Education (7).

Students are increasingly aware of their prerogative to make decisions about their own bodies, aligning this with narratives around social justice, influenced for example by social movements such as #metoo and #blacklivesmatter. Such influences, alongside experiences of physical isolation during Covid and increasing cultural awareness of sexual violence and trauma, have had significant impact. The statistics I began with are also likely to be indicative of students’ growing willingness to report mental health issues, alongside increasing systemic acknowledgement of the need to attend to student wellbeing and safety. The Office for Students (2025) (8) has issued requirements for consent and bystander policy and procedure to be implemented from this academic year at all registered universities.

Consent is a fascinating lens through which to consider some of the well-being and creative practices we engage in as dance practitioners within HE. Ideas of an empowered, ethically driven dance study that considers the intersecting dynamics of lived experience and student expectation underpin what we could consider to be ‘safe practice’.

These challenges are common across the dance sector and important work is taking place in different contexts to support and advance this, for example the Safer Dance working group (9) projects with artists and practitioners led by People Dancing and One Dance UK and there is an increasing appreciation of the intersectionality of health and equity as articulated for example in the recently published Beyond Barriers Research, which is a call to action urging the dance sector to address barriers to progression and employment in dance for disabled people (10).

At the recent People Dancing annual Summer Intensive, I attended the Choreography of Consent workshop led by Anna MacDonald and Marie-Andrée Jacob and members of the AHRC network, established to investigate law and choreography. The team introduced some of their emerging lines of enquiry. The workshop prompted movement and discussion around themes including capacity to consent, the conditions required for consent, compliance and resistance, with time for considering some of the slippery complexities of consent including trust, fluidity, the spoken/unspoken and power dynamics.

I am struck by the insights afforded when considering consent through its etymological roots. Con-sent – with listening, or to feel together. This suggests a co-active engagement, with ‘con’ meaning ‘with’ or together’ and ‘sent’ from the latin ‘sentire’, to feel, to perceive. Anna, Marie and the team

encouraged us to think about consent as a mutual process of reaching agreement, as dynamic, muscular and synergistic. As proponents of our mainly nonverbal artform, we embody a felt state of knowing: tacit knowledge as articulated by Sara Houston in her work on Soft Skills in Dance (Houston 2024) (11). These qualities may be uncodified, but they are profoundly felt. Our practices feel safe and are established out of incrementally refined processes of care with and between experienced dance practitioners and educators. Feeling ‘safe’ is a key theme for student wellbeing and it would be foolish to be complacent about how important this is. Over the last few years along with my colleagues at Falmouth we have been asking how we communicate these knowledges in a learning landscape where we are increasingly required to evidence safety and consent and increasingly vulnerable to related challenges.

And so back to Flourish.

Flourish is a process co-created with students that results in a framework for boundaries rather than a set of rules. Flourish makes space for us to learn from students’ understandings of the ‘safe’ spaces and means to dance. There is power in the invitation to create and articulate these principles, helping establish from the outset, the fundamental tenet that student voice and experience is important and should be taken seriously. The Flourish process is thoughtfully guided with emerging ideas critically explored and rationalised and tensions unpacked: modelling how to attend to different views and opinions is paramount. This is a summary of the Flourish process.

1. Introduce how we work in communities. Our course is a community of students, lecturers, technicians, public-facing and public programme staff, operational staff including cleaners, maintenance and café workers. Discussion about the other communities we are part of e.g. housemates, societies or clubs, online communities including social media or gaming networks, extended family etc.

2. Introduce questions of what makes a community. Discussion includes shared priorities, interests or values, sometimes location or specific relational bonds. Concepts of the personal, relational and systemic are introduced. The oscillation between and across these spheres is also emphasised across the course on a modular level.

3. How do we want to dance together here? What might we offer and agree to as a community of dancers? What do we expect from each other? How do we engage in ‘safe’ practice? What is ‘dancing well’? This is a useful prompt as it initiates discussion about being physically, mentally and emotionally well and what we mean by dancing well (or achieving) and how these understandings inter-relate.

“Flourish foregrounds the importance of individual agency…what conditions need to be in place to work safely and ‘well’ and to enable us to take the risks we want to take?”

4. How do these thoughts fit in with the following words: agency, responsibility, respect, care and sustainability. These themes were drawn out of the thinking done by year 1 students the first time we went through this process in 2022/23.

5. The writing is done on large pieces of paper, is not rushed or particularly codified. Some students doodle; others list. They create a group document around each theme, and the activity is loosely held so they move between sheets as they wish but they are encouraged to write something on each one even if it is to star something they agree with.

6. Notes are then drawn together and presented back to the students at a later date. They check in on it as a comprehensive account of our thinking together and we discuss our commitment to it. Students in years 2 and 3 (who went through this process themselves in year 1) are also invited re-read the document and annotate it if they wish. This serves as a reminder of the principles and that the process is dynamic: has something changed for you?

7. The document is uploaded to our shared digital learning space. It is also shared with any visiting artists in advance of their visit.

Dance study demands a consistency of effort and ongoing dynamic of discovery. This ‘learning zone’ is tiring, demanding and often uncomfortable. We are searching for a balance between creating the conditions for those who want to ‘push further’ and ‘dig deeper’ and supporting those who need a different approach that day/week or on an ongoing basis, without perpetuating an unhelpful culture of failure. Even when student empowerment is emphasised e.g. how many times to cross the floor, whether to jump/ participate etc, we remain mindful of the entrenched pressure to keep going and to seek approval.

We question how to work to recalibrate our interpretation of ‘when the going gets tough, the tough get going’ and to challenge the heritage of replication as the only marker of success.

Codifying this process through Flourish helps to facilitate discussion and brings these themes into transparency. The investment in this process supports teaching and learning as it progresses, helping us to

Falmouth University: Luis Moore & Amy Wiliams Photo: Steve Tanner.

manage potentially difficult conversations if and when issues arise and to underpin critical thinking. Flourish can support students to understand the culture of listening, empathy and consent we aim to cultivate and the important role they play in maintaining safe and healthy boundaries. This process of defining a cultural sensibility is articulated helpfully by Haarhoff and Lush (2023) (12) as a ‘bubble’ of consent. If we want our students to be able to work with risk, touch, eye contact or to play with power or vulnerability, we need to underpin this with agreements around respect, responsibility and care.

With student mental health statistics telling us that young people are dealing with an increasing amount of stress during their university years, the need for urgent attention to systems and processes that help us nurture genuinely supportive learning environments is pressing. Working in tandem with wider university mental health support, empowering healthy approaches to self-care and building supportive communities that can enable students to safely work with risk and vulnerability feels like a good balance to strive for.

References

1. Student mental health is widely reported in mainstream media as being high on the agenda of universities whose spending on this has reportedly increased by at least 73% with some universities increasing spending by 600%.

2. www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/student_ minds_insight_briefing_feb23.pdf

3. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/ cbp-8593/#:~:text=Prevalence%20of%20mental%20health%20 issues,as%20the%20chart%20below%20shows

4. Chappell K, et al, The aesthetic, artistic and creative contributions of dance for health and wellbeing across the lifecourse: a systematic review. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. 2021 Dec;16(1):1950891. doi: 2021 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34342254/.

5. www.nice.org.uk/topics/mental-health-in-students/ background-information/risk-factors/

6. www.equity.org.uk/advice-and-support/know-your-rights/ higher-education-intimacy-coordination-direction-guidelines

7. Kristin Horrigan 2024, Integrating Consent Practice in Dance Education. www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15290824.20 23.2285502

8. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/ blog/what-students-can-expect-from-new-regulation-on-freespeech-and-preventing-harassment-and-sexual-misconduct/

9. www.dsswg.org.uk/

10. https://www.communitydance.org.uk/what-we-do/disabilityand-inclusion/the-working-group

11. https://empowering2.communicatingdance.eu/guidebook/en/

12. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19443927.202 3.2191987

Info

Dr. Sue Smith is Course Leader for Dance & Choreography at Falmouth University and Chair of the Board at People Dancing. www.falmouth.ac.uk/staff/dr-sue-smith

Falmouth University: Exploring identity & belonging. Photo: Sue Smith.

DANCING OUR WAY HOME

Performer, practitioner, researcher and writer shares her practice and perspectives on African Holistic Dance, highlighting its deep roots in wellbeing and community. In these spaces, dance becomes a language of healing, a celebration of survival, and a pathway to liberation.

Introduction

In many African and diasporic cultures, dance is not merely an art form; it is a way of being, a language of the spirit, and a vital tool for healing, storytelling, and community cohesion. African Holistic Dance, an evolving practice rooted in African and Caribbean movement traditions, positions the body as a vessel of wisdom, resistance, and restoration. It is not only a performance, but a spiritual and somatic journey, a process that links the individual to the collective, and the present to ancestral memory.

This article explores the role of African Holistic Dance within community settings, and the ways in which this embodied practice supports wellbeing, emotionally, mentally, spiritually, and socially.

What is African Holistic Dance?

African Holistic Dance is an integrative approach to movement that blends African and Caribbean dance traditions with somatic awareness, energy work, and community-based healing. Unlike traditional dance forms taught in institutional spaces, African Holistic Dance often emerges from lived experience, oral traditions, and ancestral wisdom.

Drawing on rhythmic patterns, drumming, call-andresponse, storytelling, breathwork, and elemental >>

Earl Grey & Fifty Shakes Event. Photo: Idriss Assoumanou.

Photo: Aisha Golding.

“African Holistic Dance is not a trend. It is a return – a re-rooting in ancient practices that honour the full spectrum of human experience.”

connection (Earth, Water, Fire, Air and Ether), the practice honours the cyclical rhythms of nature and life. Each session becomes a ritual, reconnecting participants with their body, land, lineage, and collective purpose.

Central to this approach is the understanding that healing and wellness are communal acts; individual transformation is inseparable from the wellbeing of the group. Dance, then, becomes a medicine – a way to return home to oneself while being held by the wider community.

Community as the dance floor of healing

In community spaces across the African Diaspora, African Holistic Dance is being used to reconnect people to themselves and to each other. Community centres, churches, allotments, schools, women’s shelters, care homes, and cultural festivals have all become stages for this kind of dance work. Here, movement is not judged by aesthetic standards but celebrated for its authenticity and capacity to express truth.

Workshops often begin in circle, symbolizing equality, unity, and the ancestral realm. When drums are sounded and music played it’s not just for rhythm, but to awaken memory, release tension, and guide the group’s emotional terrain.

In this setting, laughter, tears, stillness, and exuberant expression all have space.

The practice intentionally includes people across generations and abilities – elders, mothers, youth, those with mental health challenges, a range of physicalities – inviting each to find their rhythm and pace. Whether seated or standing, grounded or flowing, participants co-create a container for embodied truth and communal restoration.

Dance and wellbeing: A holistic perspective

Through a Western biomedical lens, dance is increasingly recognised as a form of physical activity that improves cardiovascular health, coordination, and fitness.

African Holistic Dance moves beyond the physical and addresses wellbeing across four interconnected domains:

1. Emotional and mental wellbeing

Through expressive movement and improvisation, participants can safely process trauma, grief, anxiety, and emotional blockages. Dance becomes a language when words fail. The repetition of rhythmic movement stimulates endorphin release, reduces cortisol levels,

and promotes mental clarity. As participants move with breath and beat, they begin to unlock stored tension, allowing for release and emotional regulation.

2. Spiritual connection

African Holistic Dance sees the body not just as matter, but as energy. The practice often includes meditative sequences and chakra work (or energy centre alignment), particularly through the Moving A-NK-H meditation, which integrates breath, movement, and ancestral invocation. Participants report feelings of grounding, expanded awareness, and connection to something greater than themselves – be it spirit, ancestors, or the Earth.

3. Social belonging and cultural identity

Many in the African diaspora experience cultural dislocation, marginalisation, and historical trauma. African Holistic Dance acts as a vehicle to reclaim identity, honour cultural roots, and strengthen social bonds. It is a space of joy, remembrance, and

Crossing Borders Respectfully. Photo: Idriss Assoumanou.

“Workshops often begin in circle, symbolising equality, unity, and the ancestral realm. When drums are sounded and music played it’s not just for rhythm, but to awaken memory, release tension, and guide the group’s emotional terrain.”

Decolonising dance and wellness spaces

African Holistic Dance also raises important questions about who leads wellness, how knowledge is valued, and whose bodies are centred. In many wellness and somatic spaces, practices from African and Indigenous cultures are appropriated without acknowledgment. African Holistic Dance challenges this by placing Black bodies, voices, and experiences at the centre.

It insists that healing is not a product to be bought, but a birthright to be reclaimed. The practice affirms that cultural specificity matters – that dance rooted in African cosmologies can serve as powerful medicine for people who have been historically erased, exploited, or silenced.

By decolonising the lens through which dance is seen and experienced, African Holistic Dance invites a more inclusive, ethical, and embodied understanding of wellbeing.

Looking forward: Dance as community infrastructure

As global crises intensify – climate change, racial injustice, mental health epidemics – the need for culturally grounded, community-centred healing practices grows more urgent. African Holistic Dance offers a model for how movement can serve as infrastructure: a tool for resilience, cultural education,

and collective care.

Policymakers, educators, and public health professionals would do well to recognise and support these grassroots initiatives. Funding for dance and wellbeing should not only go to institutions and mainstream models, but also to community practitioners, elders, and cultural custodians who hold deep, embodied knowledge.

Conclusion

African Holistic Dance is not a trend. It is a return –a re-rooting in ancient practices that honour the full spectrum of human experience. In community, dance becomes a language of healing, a celebration of survival, and a pathway toward liberation.

To dance holistically is to remember. To move in rhythm with others is to mend the frayed threads of community.

To feel joy in the body is to declare, even in the face of adversity: I am here, I am whole, I belong.

In the words of an elder dancer,

“When we move together, we remember who we are.”

Info

www.movingtubalance.co.uk info@movingtubalance.com

A Time To Breathe. Photo: Hana Kovacs.

Photo: Andrew Moore.

Photo: Julie Howden.

METHODS IN MOVEMENT: THINKING DIFFERENTLY

Dr. Bethany Whiteside, specialist in the field of Dance for Health and Senior Lecturer at Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, shares an emerging partnership-based approach to dance research methods from co-creation through collaboration, the dance score as an artefact, and capturing the dancing danced.

“Ifeel smart in a different way!” This gleeful announcement was made at the end of a practical series of workshops involving dancers living with multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s, as coresearchers. The project titled, Methods in Movement, is explored further below. The sentiment is one that resonated more widely across the studio, and certainly with the academic researchers, as we all embraced the opportunity to work ‘differently.’

Dance for Health (DfH) is a well-established and constantly evolving field with projects and foci ranging from activities and projects tailored for people living with specific named conditions through to a more general association with wellbeing. The International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS) characterise DfH activity as ‘holistic, evidence-based activities… (with) trained teaching artists engag(ing) people as dancers, rather than patients, in joyful, interactive, artistic practice’ (1): a definition that centres academic rigour and dance experience but also nods towards the real-world context that the majority of DfH activities exist within.

However, this multifaceted definition is somewhat at odds with the more dominant trend within this

‘evidence-base’, with much academic research taking a quantitative approach to consider the impact of dance on particular health symptoms. This places value on the more tangible transactional nature of dance rather than on the subjective experience felt by dancers and dance practitioners. There is enormous potential for dance-based research methods i.e. methods rooted in movement rather than speech, written text, or numbers, to be a means of both discovering and presenting new knowledge. However, much discussion in the academic literature about the potential for such methods is theoretical. Practical exploration and development of dance research methods within DfH –tangible action, touch, experimentation, frustration, and joy – is challenged by inherent funding and logistical concerns. For example, individuals involved should be appropriately acknowledged and remunerated.

Introducing the project

Mindful of this context, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland successfully applied for and were awarded a Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) Research Collaboration Grant. Methods in Movement (MiM): DfH Scotland Research Network is an 18-month project that began in April 2024 with two core aims: to develop dancecentred methods in dance for health research and develop a national (Scottish) DfH network.

Reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the field, the core project team is comprised of dance scholars, Drs Bethany Whiteside and Emily Davis (Royal Conservatoire of Scotland), Prof. Sara Houston (University of Roehampton), and Dr Morven Shearer who has a background in medical ethics and healthcare policy (University of St Andrews).

Colleagues from project partners, Emma Smith at Dance Base, Scotland’s National Centre for Dance, and Tiffany Stott at Scottish Ballet, Scotland’s National Dance Company, are also an integral part of the team.

Activities to date (July 2025) have included a review of academic studies that cite dance-based methods and desk-based and survey activity to map DfH activity in Scotland. We also held an online consultation with Scotland-based DfH practitioners and organisations, and a series of in-person workshops with individuals from the longstanding SB Elevate® programme (dance for multiple sclerosis) and Dance for Parkinson’s programmes at Scottish Ballet and Dance Base, respectively.

These workshops (with each partner) took place during spring 2025. We discussed, shared, wrote, and danced together ideas and emotions that were particularly meaningful to the dancers and practitioners involved, culminating in two co-created choreographic scores. Both scores reflect a particular culture of care that exists within each community, explored first through speech, then words, and then through movement. We used movement throughout to reconnect and refresh, to gesticulate and experiment.

“There is enormous potential for dance-based research methods i.e. rooted in movement rather than speech, text, or numbers, to be a means of both discovering and presenting new knowledge.”

should always aim to do good but should also be a joyful experience wherever possible. A core thread running throughout the workshops, that came to the fore during concluding de-briefs, was that of joy and how this manifested in different ways. We are especially excited to understand how the experience of being a co-researcher rather than a research participant may have impacted on dancers’ confidence and offered them a sense of excitement, through doing something ‘different’ to their regular Dance for Health class. We are keen to understand practitioners’ insights on how choreographic scores could be creatively developed within DfH spaces and if they feel the workshops have changed their relationship with dancers (particularly long-term dancers, who they have worked with for many years). As academic researchers, we have valued an approach where the responsibility of carrying out the research – experimenting with choreographic scores –was shared.

In terms of the project’s next phase, we will be considering how this approach – the act of co-creation through collaboration, the score as an artefact, and the dancing danced – can be developed further as a research method. Words and movement could be further analysed to understand responses to a particular research question or focus. Developing and disseminating such activity will circle back into supporting the second aim of the project – to develop a Dance for Health network in Scotland, supporting organisations and individuals in their evaluation and research activity – and we hope will have wider resonance much further afield.

This project is supported by an RSE Research Collaboration Grant.

References

1. International Association for Dance Medicine and Science. (2021). Dance for Health. Accessed at: https://iadms.org/ education-resources/dance-for-health/

Info

Dr Bethany Whitside is Senior Lecturer and Doctoral Degrees Coordinator at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

B.Whitside@rcs.oc.uk

https://pure.rcs.ac.uk/en/persons/bethany-whiteside

Photo: Robbie McFadzean.

SAFELY GATHERED IN: LOVE AT THE HEART OF DANCING WITH PARKINSON’S

Treflects on her shifting learning across ten years of Strictly Parkinson’s Powys in mid-Wales and how dance is all about ‘meaningful and genuine human connection’. Are we brave enough to characterise Dancing with Parkinson’s as a practice with love at its centre.

conversation with members of Strictly Parkinson’s about undergarments! Participant Margaret’s grandma referred to her bloomers as a place ‘where all is safely gathered in’...what a wonderful way to describe Strictly Parkinson’s!

François Matarasso writes in 2025: ‘Success in community arts projects… comes in all shapes and sizes, in all colours and feelings, and for many different reasons. Competence will deliver a good project. A great one comes from the unforeseeable interaction of people and situation – it is co-created and therefore neither predictable nor controllable. There is everything to learn from reflecting on how it has come about because, by understanding and creating the underlying conditions for success, you increase the chances of achieving it.’

With 35 years of community dance under my belt, I finally feel secure in my practice. I am beginning to wonder about learning and legacy.

In my most treasured practice, dancing with Parkinson’s, I meet the greatest joys and most significant challenges of my dancing life. Loss and bereavement, in my experience, are part of this rich context. Here, I have come to think of death as simply the shrugging-off of life, letting it slip gently from the shoulders. My own experience with serious illness allowed me to fall into step with mortality. This is freeing and helps me meet my Parkinson’s community with compassion and without fear. We do not shy away from difficult moments. “I feel closer to him when I am here”, Jane offers. The space is peopled with much-loved ghosts.

With only four blank pages left, my journal tracks ten years of Strictly Parkinson’s.

The beginning is highly organised, aligning movement and vocal content with symptoms. It gradually shifts to the point where these considerations are taken as read, and it gives way to lists of who is

coming to the pub for lunch, what to write in a card and, most recently, favourite songs about trees. It turns out there are many, as our collective memory begins to whirr.

The song, The Ash Grove is familiar to most from school days. The brightness of the tune from the Welsh folk canon belies a narrative of love and loss in the lyrics. We give it a go, the pitch determined by our dear friend whose grip on a shared reality is unravelling.

These days, most of our dancing is necessarily seated. Keeping with the folk theme, we invent a May Pole dance. We loop, knot, plait, weave, get in a muddle, and laugh. Not a ribbon or a pole in sight; pure movement-play and imagination are at work here.

Looking around the circle, I note that none of us is free of a health condition or two. Parkinson’s, with its many and varied manifestations, is joined by heart conditions, hyper-tension, long COVID, cancer, dementia, auto-immune conditions, diabetes, vascular disease, arthritis…and there is bereavement, of course. For loved ones and for one’s own changing self.

Nel Noddings (2) characterises effective teaching as a relationship of care. I find this useful.

Community Dance, for me, has always involved teaching of some kind, although we more usually refer to it as ‘leading’ or ‘facilitating’. It is emotional, intellectual, physical and above all, creative and responsive. We are in continuous dialogue with ourselves, each other, dance and our moving expressive bodies, with life itself. As wellness and emotions are in constant flux, this is a practice of navigation.

The craft of Community Dance is so embedded in who I am it has become intuitive. I lean on it heavily to guide us through uncharted territory. It has not failed me yet. My attention is largely attuned to the emotional undertones of each moment; this takes precedence over the dancing. Knowledge of each person, their family circumstances, their tastes and preferences,

>>

Photo: Bill Hart

“The craft of Community Dance is so embedded in who I am it has become intuitive. I lean on it heavily to guide us through uncharted territory. It has not failed me yet.”

Strictly Parkinson’s, Photographer/Filmmaker: Nikki Davies (and below)

every invitation to participate, every activity created.

Noddings asserts that ‘empathic accuracy’ is more likely to be achieved when relationships are well established. In holding and ‘reading’ the space, tensions can arise between an individual’s emotional needs and progressing through a group session. For us, the individual’s needs take precedence. If one person is distressed, we all feel it. We negotiate the moment together. In Nodding’s work the needs of ‘the curriculum’ and ‘the institution’ can overshadow empathic relationships, despite it being well evidenced that we only learn effectively when our emotional and safety needs are met. Luckily, at Strictly Parkinson’s, we have no curriculum to ‘deliver’ and we are our own ‘institution’, answerable only to each other. Self-funded through legacies and donations to the South Powys branch of Parkinson’s UK, we are freed from agendas imposed by others. Free to be who and what we are. And what we are, above all else, is a kind and loving community.

Dr Jools Page (3) builds on Noddings’ work making a brave leap from ‘care’ to ‘love’ in discussing relationships between professionals and pre-school age children. In this context, parents look to child-care professionals to provide their children with a secure, safe and loving environment in which they can thrive. I am not likening the two contexts but I wonder if we are brave enough to characterise Dancing with Parkinson’s as a practice with love at its centre?

To my mind, there are significant parallels including building authentic and close relationships, contact with families, shared information around health needs and treatments. I increasingly feel that mine is a practice of love.

Page asserts that adults who work in emotionally loaded roles need to be nurtured themselves. Do we do this? And if so, how? Personally, my greatest

source of support comes from the members of Strictly Parkinson’s themselves. Relationships are reciprocal. Opening to their ever-present warmth and friendship is nourishing and revitalising.

Noddings reminds us that, ‘teachers sometimes forget how dependent they are on the response of our students.’ Knowing that our care has been received comes in a range of responses, a look, a touch, a smile, a vocalisation, a movement, a twinkle behind the eyes, a tear, a conversation. In short, meaningful and genuine human connection. This reward, affirmation and encouragement build my confidence, helps me to grow in capability and capacity and is a source of wellbeing.

As Cai Tomos (4) beautifully puts it, “care goes both ways in this practice”.

References

1. François Matarasso on 16 February 2025 Blog Finding the good – François Matarasso

2. Noddings, N. (2012) The Caring Relation in Teaching, Oxford Review of Education, 38:6, 771-781, DOI: 10.1080/03054985.2012.745047

3. Page, J. (2018) Characterising the principles of Professional Love in early childhood care and education, International Journal of Early Years Education, 26:2, 125-141, DOI: 10.1080/09669760.2018.1459508

4. Tomos, C., Arts, Health and Improvisation. Workshop for Wales Wide Training Programme, 7th May 2024

Info

Heidi Wilson is facilitator for Strictly Parkinson’s in South Powys, and Senior Lecturer in Dance at Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University. Heidi combines this work with freelance and consultancy across the community arts sector in the UK. www.cardiffmet.ac.uk/staff/heidi-wilson/ wahwn.cymru/knowledge-bank/video-strictly-parkinsons

MOVEMENT IN SCHOOL READINESS

Daniel Fulvio of major UK contemporary dance company, Rambert and Julie McCarthy of Greater Manchester Combined Authority/ NHS GM share their reflections on a unique partnership project in early years settings, which is not only supporting school readiness but inspiring the creativity of early years practitioners.

Early Moves is a playful early years dance partnership programme using dance and movement to broaden access, unlock potential, and create positive change in the lives of early years children, their families and across early years settings. It is part of the Greater Manchester Creative Health Place Partnership (1), a three-year programme led by Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and NHS Greater Manchester, with Rambert, with its reputation for cutting edge work, has evolved into the most widely touring contemporary dance company in Britain. Rambert tours new, large scale across the UK complemented by equally extensive education, outreach and participation work.

Early Moves is part of a broader creative health programme in Greater Manchester which aims to embed creative health approaches across the health and social care eco-system, with a particular focus on

some of Greater Manchester’s most pressing health

For the partners involved in Early Moves, it’s success is demonstrating how dance and movement can be a powerful tool for improving school readiness, supporting children facing the most acute inequalities whilst at the same time promoting the development and wellbeing of the early years workforce.

In the six months since Rambert and Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) launched Early Moves, 17 nurseries across eight of Greater Manchester’s ten boroughs have taken part, over 30 early years practitioners have been supported to gain skills and confidence to lead dance sessions in their settings, and many have observed important and sometimes unexpected ways that movement has help their preschoolers’ development.

The programme began with the understanding that movement can support children to develop gross motor skills involving the whole-body; walking, running, and jumping and fine motor skills; using the small muscles in the hands, fingers, and wrists (2). These skills are building blocks for literacy and numeracy and crucial for physical coordination, balance and sitting up (gross skills) and for self-care, hand eye coordination and learning to write (fine skills) (3).

Increased opportunities for rich, self-directed, physical play also have positive impacts on gross motor skill development and young children’s ability to sit still, focus and engage socially and children who start school with good levels of physical development are more likely to thrive in their reception year and beyond, with a ripple effect positively impacting their confidence, career opportunities and overall life outcomes for years to come.

Early Moves is designed to support early years settings to embed regular, imaginative movement into children’s daily routines in a way that is low-cost, of high quality and in a way that is sustainable beyond the life of the project. Whilst our original focus was to test the impact of movement sessions on gross motor skills, we are starting to see promising impacts in other areas of development, including literacy, numeracy and selfregulation.

Working closely with Local Authority Early Education Leads across Greater Manchester, we started by identifying early years settings best placed to benefit from participation – whether they were eager to try new approaches, or because they served communities facing persistent inequalities and with limited access to resources. This ensured the programme could be quickly embedded and could respond to local need.