Serving

and Carson Valley FALL 2025

Serving

and Carson Valley FALL 2025

publisher: harryJONES

editors: allisonJONES

MelanieCano

layout design: aaronJONES

Contributing Writer: MarkMclaughlin

Northwoods Tahoe is distributed FREE in locations in Truckee and Tahoe, also on www.northwoods.news and www.Issuu.com.

When you visit our advertisers, please mention that you saw their ad in Northwoods Tahoe. Thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: Articles, if printed, become the exclusive property of Community Media LLC. We reserve the right to edit, or choose not to print submissions. The views and opinnions expressed in the content of Northwoods Tahoe are not necessarily shared by the Publisher, Editor, Community Media LLC or anyone else.

2292 Main Street, Suite 7, Genoa, NV 89411

Mailing: PO Box 1434 Genoa, NV 89411

For advertising: (530) 582-9012 email: harry@communitymediallc.net

(775) 301-8076

WWW.NORTHWOODS.NEWS

WWW.TAHOEWEATHERCAM.COM

© 2000-2025 Community Media LLC. Reproduction of any part of this publication by written approval only.

By Mark McLaughlin, Historian

Like Tamsen Donner before her, Electa Louesa DeWolf was a teacher who felt the power of the Sierra. But unlike Tamsen, whose 1846 wagon train stalled in deep snow north of Donner Lake with tragic consequences, Electa reached Truckee in comfort, by train in 1874.

The transcontinental railroad, completed in May 1869, opened the door to safe cross-country travel for westbound emigrants. The long ribbon of iron rail connected the Atlantic States with California, and removed most of the dangers faced by early emigrants.

Tamsen Donner had been writing a book during her overland crossing of ’46. Unfortunately, the manuscript was lost during that tragic winter. Fate was kinder to Electa DeWolf, and the letters she wrote during her stay in the Sierra between 1874 and 1881 have been saved for posterity.

Electa began her education in 1847 at a little country schoolhouse in Vernon, Ohio. In 1864, she graduated first in her class from the Western Reserve Seminary at West Farmington, Ohio, with the degree “Mistress of English Literature.” In Ohio, she began her teaching career, but other dreams still burned in her heart. In a letter, Electa wrote, “Three things I have always felt I could never be reconciled to have unseen: the Ocean, Mountains, and California.”

Electa got her wish for all three in 1873 when Nathan Parsons, an Ohio native and now a California pioneer living in Sardine Valley north of Truckee, wanted a teacher for his four children. Mr. Parsons offered to pay Electa’s train fare to California and back, in addition to compensating her for the time spent teaching the children.

continued on page 4

The Pacific Tourist...A Complete Traveller’s Guide of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads (1876) Page 3, The Palace Car. Public Domain

Nathan Parsons and his wife owned the Sardine House, a station and lodging house on the Henness Pass Road, the most direct route between Reno and Sacramento. Just a few years before, Mrs. Parsons had played sleuth when she observed several guests at her hotel behaving suspiciously. She followed one of the men to the bathroom, and through a peephole watched him pour $20 gold pieces into an old boot, which he lowered into a latrine. Mrs. Parsons tipped off the sheriff, who ended up capturing the group of men. It turned out they were bandits who just pulled off the first Western train

holdup, known to historians as the Great Verdi Train Robbery.

The transcontinental line had been running for only five years, but Electa’s letters, later published in several Eastern papers, offer firsthand insight into passenger enthusiasm for trains. She wrote, “Pullman, the man of palace car fame, has made traveling by steam in these latter days almost a luxury. The ride from Chicago to San Francisco can be accomplished now in six

days, and with very little fatigue.” Just a few years before, the overland trek by wagon train would have taken from five to six months of strenuous physical effort.

Electa switched to the Central Pacific railroad line in Ogden, Utah, and bade farewell to her traveling companions when they reached Truckee. She then quickly turned her attention to the beauty of the Sierra landscape. She wrote, “The mountains are glorious. The air up here is pure and bracing, the sky has an intensity of color never seen in low altitudes, and the sunsets often beggar description.” Electa arrived at Sardine Valley around Thanksgiving, and was astounded at the mild weather at such a high elevation. She wrote, “Within the past two days we have been enjoying a pleasant season, warm in the sun, cool in the shade, the exact counterpart of that I’d expect here during the last two weeks in November.”

Winter weather wasn’t far behind, however. Mark Twain once said, “There are two seasons here, the

A real nursery for any plant lover. We’ve been helping Sierra gardens thrive for over 40 years.

Christmas Accouterments:

•Silvertip Christmas Trees (Limited Quantity)

•Greens, Wreaths, Garland, Poinsettias & Ornaments

Fall Specials:

•Mountain Cold-Hardy Plants

•Organic Compounds, Potting Soils & Fertilizers

•Native Trees, Shrubs, & Wildflowers

•Pottery, Art, & Gifts

breaking up of one winter and the beginning of the next.” Twain was describing Mono Lake, but his observation is just as accurate when applied to the High Sierra. Electa wrote, “Our first snow fell on the last day of November. I shall always remember that winter with its snow, which was eight feet deep on a level, solidly packed snow. The road from Sierra Valley to Truckee was kept open all winter, but I well remember by what work and effort, so that we were not isolated.”

Despite the persistent snowstorms, Electa wrote, “A man must be hard to please if he cannot be suited here.” She also mentioned the dramatic contrast between the staggering Sierra snowpack and the lush green of the lower valleys in California: “Today there will come into this mountain-hotel, a man on snow shoes, having come over snow thirty and forty feet deep; tomorrow a man from below, telling of green fields of grain almost ready for harvest, fresh vegetables, strawberries and flowers; another from a dozen miles away talking of dusty roads and gardening in progress; and we at the same time are looking out over a valley and hills covered with about two feet of snow. This valley [Sardine] has an elevation of over six thousand feet above sea level. Nothing but grass will grow here. Yet we have upon the table

d’hôte all the early garden vegetables, and strawberries are in market.”

In today’s fast-paced world, visitors to the Sierra rarely take the time to observe the subtleties of natural phenomena, but in the 19th century, it was a favorite pastime. Consider a day after school for Electa and her students: “Today, after lessons, my pupils and I went out on snow shoes in search of buttercups, real genuine buttercups and a little white flower resembling candy tuft, and found them growing cheerily not two feet from the snow. Nothing is strange nor improbable so far as climate is concerned.” She later wrote, “Probably not less than thirty-three-feet of snow has fallen here during the winter. On the tenth of March there was eight feet of very solidly packed snow.”

After her first winter in the Sierra, the glory of spring was something to be celebrated: “When I wrote you last, we were still rejoicing in about four feet of snow. May brought in her train a bevy of warm, sunny days; and, presto! the change. The snow, except upon the higher mountains and on the hills with a northern exposure, disappeared as if by magic, and the beautiful green of resurrected nature covered the valley. Probably not less than a hundred varieties of wild flowers, some of them exquisitely beautiful, could be gathered here.”

The following summer, Electa explored Independence Lake, so named by Gus Moore, who “discovered” it June 28, 1860, and took a party of ladies and gentlemen there to celebrate Independence Day. On the Fourth of July, 1874, Electa climbed Castle Peak with a group of friends led by Truckee patriarch Charles McGlashan.

Although she complained about the riding attire women were obliged to wear in those days, in a letter four days later, she exulted in the challenge: “The excursion was a trifle hazardous perhaps, but now that we are all safe at home without broken bones, the spice of danger only adds flavor to the occasion. A rare excursion because probably no Fourth of July before found adventurers upon Castle Peak.”

Electa also admired the sublime beauty of Donner Lake: “The surrounding scenery is picturesque and grand, and the drives along its shore are exceedingly pleasant. Under the influence of a high wind the waters danced and the white caps of mimic waves chased each other to shore, dashing upon the beach in white wrath, and yet beneath this rough exterior you could look down into quiet depths.”

Composition & Presence

Dominated by its face, the painting is rendered in a tight, almost confrontational close-up. By cropping the animal so tightly, Sweeney removes any contextual background, instead letting the bison itself carry the full weight of the narrative. We are locked into direct eye contact, which creates a sense of tension that justifies the cautionary title. The horns, framing the composition, act almost like parentheses enclosing your gaze and holding it firmly in place. This choice amplifies the immediacy of the encounter—it feels less like a painting of wildlife and more like a standoff.

Sweeney’s palette is both naturalistic and expressive. The deep violets, mauves, and russet tones lend the bison’s fur an impressionistic vitality, while the highlights—especially on the horns and snout—pull the form forward with a luminous intensity. The background swirls of purples, oranges, and soft pinks blur into the edges of the animal, suggesting movement, dust, or even the primal energy of the plains. This ambiguity enhances the psychological tension: the bison seems to emerge from an almost elemental haze, larger than life and unyielding.

The texture of the fur is handled with painterly variation: some passages are highly worked, showing the tangled density of the bison’s coat, while others dissolve into looser strokes that echo the swirling background. This balance prevents the work from becoming systematic

while still maintaining a strong sense of realism. The horns and nose are treated with a different kind of attention—smooth, reflective, and almost marble like—which contrasts sharply with the matte density of the fur. This draws the eye directly to these critical features, emphasizing both threat and individuality.

Perhaps the strongest achievement of this work is how it captures both majesty and menace. The bison’s eyes, rendered with a glint of light and subtle asymmetry, seem to follow the viewer—alert, sizing us up. Combined with the forward push of the composition, the effect is almost confrontational. The title “Get Back in Your Car” comes to life here: it’s as if we are already too close, standing in the animal’s space, facing the raw power of the wild.

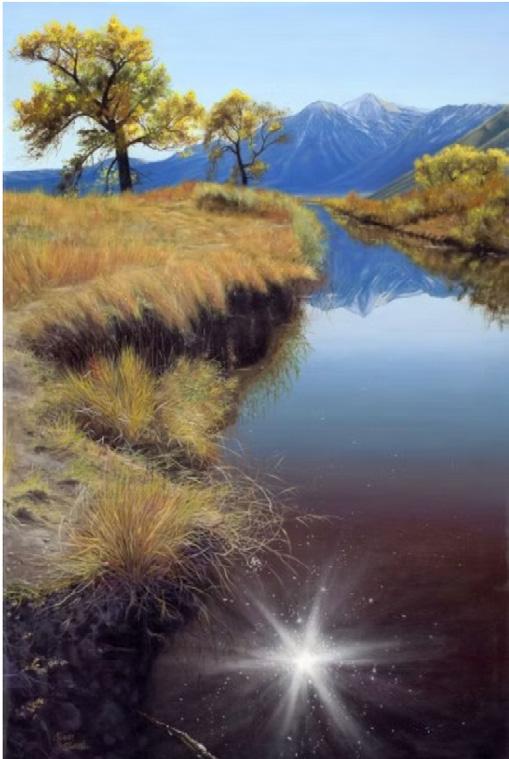

As a landscape painter, She is constantly observing nature—whether walking, cycling, or driving—always seeking scenes that capture light, mood, or atmosphere in a new way. She carries a

camera to record these moments, later using photos and sketches to develop compositions. Her process begins with loose backgrounds that gradually build toward areas of detail, balancing definition with softer spaces to create depth and mood. Influenced early by mentor Julie Gilbert Pollard, She values strong design and abstract shapes as the foundation for realism. Her goal is to share the nuances of the natural world, revealing details and moods that might otherwise be overlooked, and to create paintings that speak with clarity and emotional resonance.

Visit The Genoa Gallery to see more artwork by Teri Sweeney

Often positioned near the primary point of entry, mudrooms are a popular addition to many family homes. These organizational dynamos are the perfect place to catch muddy boots, backpacks, sports equipment and dirty paws before they make it all the way into the main living areas.

Luxurious mudrooms in high-end homes can sometimes boast custom cabinetry, full bathrooms, laundry facilities, showers for pets and direct pantry access.

Regardless of whether your mudroom is an actual room or just a small space near the front door to hang bags and jackets, the organizational basics are the same:

Get Hooked: Securely anchor a row of strong hooks along the wall for coats, hats, scarves or other seasonal accessories that may otherwise find themselves dropped on the floor upon arriving home.

Mud Happens: Mudrooms are meant to handle dirt so nix the carpet and lay down tile or hardwood flooring. Pick a stylish rug to catch dirt in its tracks while also adding a design element to the space.

Shoe Space: Place a wooden bench or sturdy coffee table near the door so everyone has a place to sit while removing shoes. Slide a few baskets or bins underneath as an alternate location for storing backpacks and other gear when not in use.

Take Command: Create a family command center by adding a small cabinet or desk with a corkboard above. It makes for a perfect spot to stash keys, charge cell phones, open mail, sort school papers and post the family calendar.

Find more organization tips and tricks at eLivingtoday.com.

Garage doors can experience a variety of issues, from minor annoyances to major malfunctions. However, regular maintenance can not only ensure safety and longevity, but also prevent small issues from escalating into costly problems.

Common problems include the door not opening or closing properly, unusual noises during operation, the door reversing before it fully closes, uneven door movement and slow response time from the opener or remote control.

Identifying the root cause is the first step to fixing the issue.

• Door not opening or closing properly: This could be due to misaligned sensors, which can be fixed by adjusting the sensor brackets at the bottom of the tracks or cleaning the lenses.

• Noisy door: This can typically be resolved by tightening all the hardware, including hinges, bolts and screws - as well as the opener’s chain or belt - or lubricating the moving parts such as rollers, hinges and tracks. Be sure to replace any that are worn out or damaged.

• Door reversing before it hits the floor: Often caused by an obstruction in the path of the door or a misadjusted limit setting. Check for an object blocking the door (or a sensor) or reset the limit to alleviate.

• Door moving unevenly: Possibly due to worn-out springs or cables, it’s often best to replace the damaged parts.

While many garage door maintenance tasks can be handled by homeowners, certain situations warrant professional intervention. For instance, if you notice significant damage to the springs or cables, it’s best to call a professional.

Discover more easy and effective DIY solutions for common garage door problems at eLivingtoday.com.

If you’ve ever scrambled across a boulder field high in the Sierra Nevada, you may have passed within inches of a creature you never knew was there. Tucked deep between granite slabs lives the Mount Lyell Salamander (Hydromantes platycephalus), a rare amphibian that has perfected the art of mountain survival.

The Mount Lyell Salamander doesn’t stand out at first glance. Its body is flattened and mottled in shades of gray and brown, patterned perfectly to blend into the granite slopes it calls home. Younger individuals often sport golden or greenish hues, but all share the same body plan: short limbs, a stubby tail, and webbed toes that help them cling to slick, rocky surfaces. [1]

This camouflage is essential, because the salamander lives in some

of the most exposed environments in the Sierra—talus slopes, rock fissures, and even mossy cliffs kept damp by melting snow.

Unlike most salamanders, the Mount Lyell Salamander has no lungs. Instead, it breathes entirely through its skin and the lining of its mouth, which means it can never stray far from moisture. The cool seepages of high elevations—anywhere from 4,000 to over 12,000 feet—are its refuge. [2]

Most of the time, the salamander remains hidden, emerging during wet nights or in the wake of snowmelt. On a rare lucky evening, hikers may spot one gliding silently over granite, vanishing back into a crevice at the first sign of movement.

The salamander’s reproduction is as unusual as its lifestyle. Females lay small clusters of eggs in moist rock crevices during late

1) California Herps – Hydromantes platycephalus (Mount Lyell Salamander): https://www.californiaherps.com/salamanders/ pages/h.platycephalus.html

2) Stebbins, R. C., & McGinnis, S. M. (2018). Species Account for U.S. Forest Service, Region 5: Mount Lyell Salamander Hydromantes platycephalus (Pre-publication Draft). ResearchGate. https:// www.researchgate.net/publication/328345859

summer or fall. Instead of hatching as aquatic larvae, the embryos develop fully inside the eggs. When they finally emerge, they are tiny, fully formed salamanders, skipping the tadpole stage altogether. [2]

A typical clutch contains only six to fourteen eggs, which makes every successful hatch an important contribution to the population.

Fortunately, the Mount Lyell Salamander is not currently endangered. Biologists consider it stable across its range, though its specialized habitat makes it sensitive to local disturbance. [2] For now, it remains a quiet symbol of the Sierra Nevada’s hidden biodiversity.

So next time you’re high in the granite wilderness, pause for a moment and look closely at the cracks between the rocks. The unassuming Mount Lyell Salamander may be there, reminding us that even the harshest landscapes have room for mystery and life.