4.4 Microclimate and User Comfort

Related SPD sections • 4 3 Green and Blue Infrastructure

Key City Plan policies

32. Air Quality

33 Local Environmental Impacts

41. Building Height

Microclimate refers to the local climate of a small area or of a particular habitat, which is different from the macroclimate of the larger surrounding geographical area.

The public realm should be designed to achieve optimum comfort levels for users to encourage longer dwelling periods. This can be done by considering microclimatic factors such as:

• Temperature / Thermal Comfort

• Sunlight / Solar exposure (sky view and shadowing)

• Wind / Air direction, movement, and speed

• Air Quality/ Dust and pollution

• Acoustic Comfort / Environment

Context

This guidance is focused on the impact of microclimates in the public realm. Both natural and human-induced conditions such as wind, sun, temperature, air quality and noise create specific micro-climates within urban environments.

Micro-climates influence how people use the public realm and should therefore be carefully considered when designing proposals for public spaces. Any scheme development should take a proactive approach to mitigating adverse local microclimatic conditions.

Building design can have a significant impact on the public realm. Proposed developments should not negatively impact the usability, comfort or safety conditions of a public space.

Temperature/Thermal Comfort

Thermal comfort in the public realm is described as the ‘feels like’ quality of the microclimates, i.e. a person’s perception of feeling neither too hot nor too cold. Many factors influence people's experiences of thermal comfort, including age, and physical attributes. Thermal comfort modelling encapsulates all of the effects on the microclimates such as wind, sunlight, temperature and humidity, a good understanding of thermal comfort conditions enables new schemes and public spaces to be developed to the highest thermal comfort quality.

Thermal comfort will vary season to season, sunny areas that are subject to windy conditions may be appealing in the summer months but uncomfortably cold in winter. Equally, shaded areas may not be comfortable to dwell in in the winter but are appealing in hot summer weather. Therefore, it is key to forward plan and create a robust and adaptive public realm.

London is experiencing hotter and drier summers that are further impacted by the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI). The UHI can cause London to be up to 10°C warmer than neighbouring rural areas as the sun rays are absorbed and radiated by hard

surfaces, rather than by vegetation such as trees, plants, and grass. The UHI reduces the ability for cities to cool and impacts on our own capacity to regulate temperature.

The use of carefully selected materials can curtail or add to thermal comfort, such as glazing, green walls and soft/ hard landscaping. Glass can reflect sunlight and radiate heat, making conditions sweltering hot in the summer and comfortably warm in the winter. Green roofs, living walls and green façades can be valuable for building energy performance and for urban microclimate mitigation increased greening can also reduce the impact of carbon emissions.

Expert judgement remains a requirement at the commencement of a scheme, as this guidance cannot cover all eventualities and schemes should be assessed individually.

Sunlight/ Solar Exposure (sky view and shadowing)

Sunlight has an important positive effect on public spaces; sunlit spaces are more attractive, are more pleasant to spend time in, and are beneficial to biodiversity, and public health

It is important to consider the solar glare or dazzle that can occur when sunlight is reflected from different materials such as a glazed façade or areas of metal cladding. This can affect public realm users and is a serious safety issue when drivers are blinded. For larger public realm schemes, the solar glare impacts should be assessed at an early phase of design to avoid the need to retrospectively address unforeseen impacts.

Shadows

When considering sunlight conditions, it is important to also consider the shadows which they can create.

There are a number of ways in which shading can be created in the public realm:

• By the change in time and setting of the sun, subsequently creating shadows from surrounding buildings, commonly seen in Westminster in areas with increased high-rise buildings.

• Deciduous trees are a good way to provide shade in the summer months and increase thermal temperatures in winter, as they will not be in leaf in winter, when sunlight is at a premium. The dappled shade of a tree is more pleasant than the deep shadow of a building, however, locations for tree planting should be chosen with care. The aim should be to have some areas of partial shade under trees, while leaving other areas in full sun. For more information regarding green infrastructure, please see Chapter 4.3 Green and Blue infrastructure within this SPD.

• For large-scale projects, a shadow plotting plan is an appropriate action to take, this would involve producing plans showing the location of shadows at different times of the day and year and its expected user pattern.

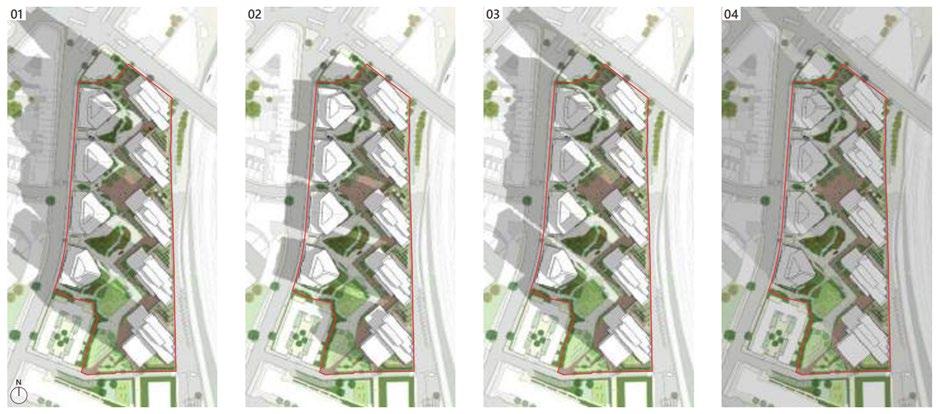

Case Study: Ebury Bridge

The below diagram highlights the change in shadows created by the sun at alternate times of the year. When an area is well lit by sunlight and offers places of respite in the shade, it can promote longer dwelling periods and increased use of the public realm

Bridge in spring, summer, autumn and winter, showing how green space is sited to maximise sunlight through the year.

Wind/Air direction, movement, and speed

Wind conditions within the public realm can affect comfort levels for users and like other microclimatic effects, can be affected by seasonal change.

Wind is a natural phenomenon that can be manipulated and impacted by its surroundings. Wind in the summer may be a welcome relief from intense heat, whereas in winter months high wind speeds may discourage individuals from dwelling in certain areas. In Westminster tall buildings can cause wind tunnels which directly affect the user experience creating uncomfortable and, in some instances, unsafe conditions. When considering the placement of a scheme and/ or street furniture it is important to consider the impact of wind tunnels and if possible, avoid close proximity to them. Effective landscaping can mitigate the impact of high wind speeds. Planters, ‘windrows of trees’ and ‘wind-break shrub hedges’ help to break up wind flows at ground level, and create a gentle breeze, an ambience of calmness generated by the sound of the leaves in the wind.

Note, building heights effect wind microclimates in the public realm, the taller the building the larger the impact. We follow guidelines produced by the City of London on Wind Microclimate which set out the general expectations for the types of wind microclimates studies required for various building heights.

Some existing tall building proposals may have involved wind modelling. These will be a useful resource in preparing public realm schemes.

Wind effects can have a major impact on cycling comfort and safety. In extreme cases, particularly the crosswinds can destabilize or push the cyclist into the path of vehicles. With increasing numbers of cyclists in London this is an important consideration.

Assessments should also take into account approved development within the vicinity. Even if development is yet to be built or in the early stages of construction, any new development is likely to cumulatively affect any wind modelling exercise so should be considered in wind assessments

Air Quality / Dust and Pollution

The long-term impacts of air pollution are widely known and recognised. In the short-term, air quality in the public realm can impact a user's decision to dwell in an area for prolonged periods or even cause them to avoid an area altogether. It is therefore important to shape the public realm to ensure exposure to air pollution is minimised to improve user comfort and contribute to improving user health long-term.

Benefits of improving air quality include:

• Contributing to urban cooling and helping to reduce the urban heat island effect, the public realm is a highly influential space which can be used to address the negative impacts of the urban heat island effect through creative and thoughtful design.

• Improving health and wellbeing.

• Encouraging users to dwell longer, benefitting local businesses and supporting social activity.

Westminster City Council have published their ‘Air Quality Action Plan’ which identifies several priorities to help keep our air clean: reducing or cleaning dirty journeys and creating better infrastructure for electric and low emission vehicles; placing emissions and pollution at the forefront of decision making on public spaces and buildings; making environmentally friendly options easier for everyone; moving the air quality agenda forward through thought leadership and innovation.

It is important to future proof designs for public realm schemes, with adaptative measures in mind. The placement of public spaces should take account of air quality microclimates For instance, it would not be appropriate to place a children’s play park in a location subject to high levels of emissions from petrol and diesel vehicles.

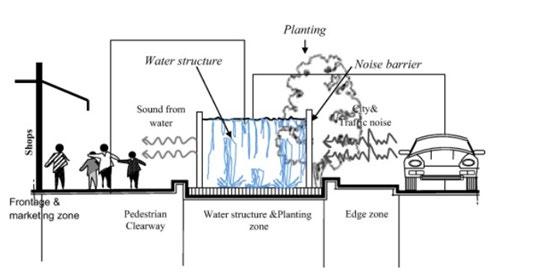

Pedestrians should be kept spatially away as best as possible where busy and polluting roads remain, strategically placed greening infrastructure and/or green corridors could be considered to create a barrier reducing the level pollutants which reach pedestrians; however, their careful placement is integral to the efficacy of this method.

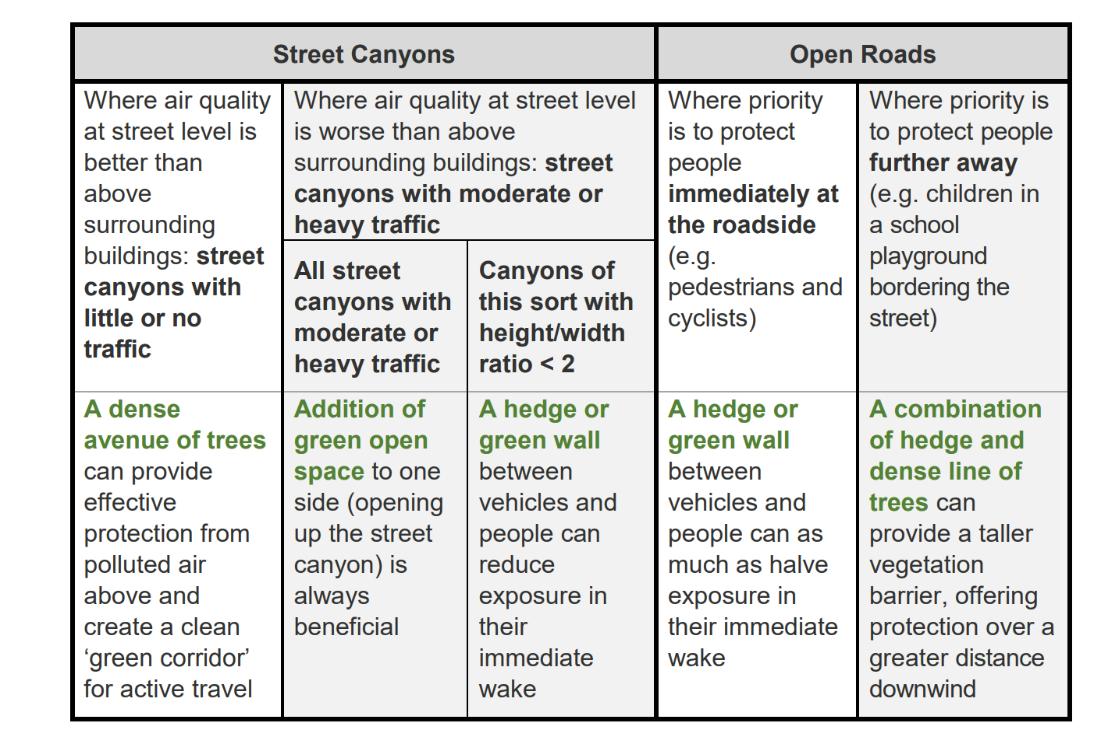

The Mayor of London has produced guidance demonstrating the different ways in which green infrastructure can be utilised to alleviate the effects of air pollution, outlined in the table below:

21: Mayor of London's right green infrastructure, right place.

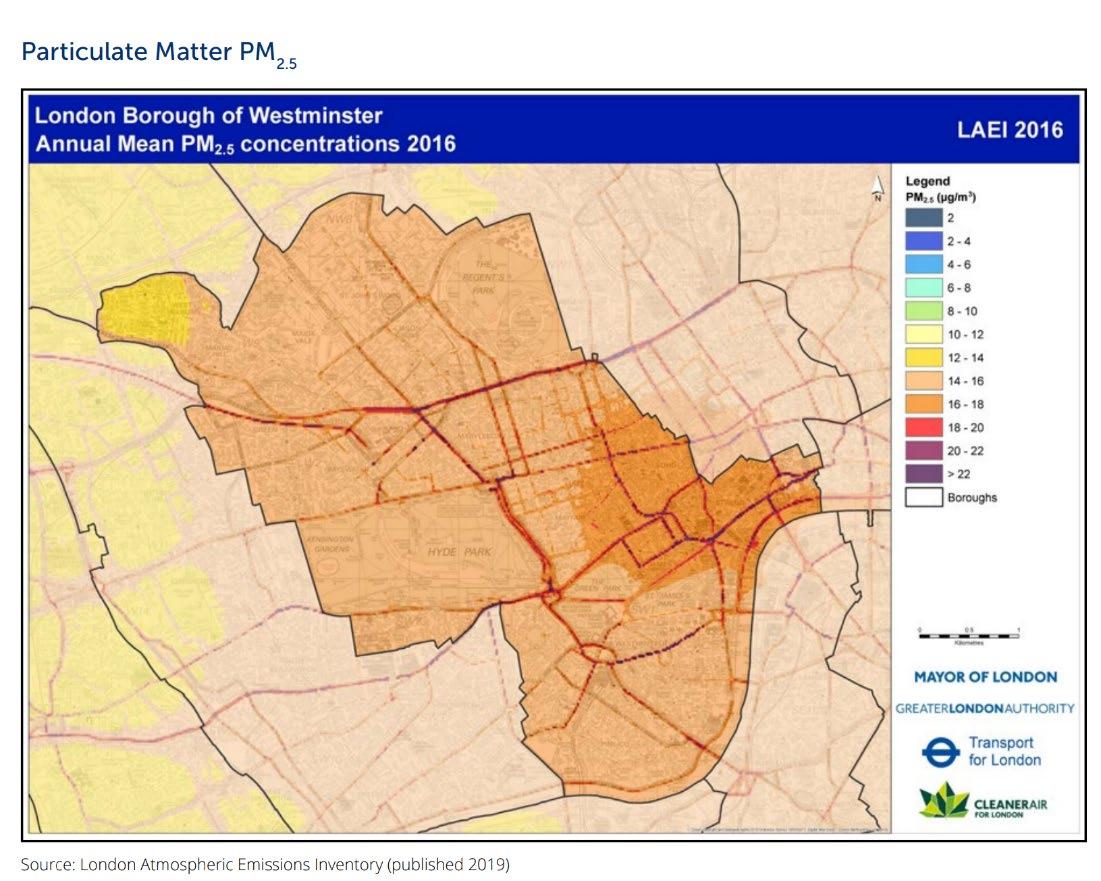

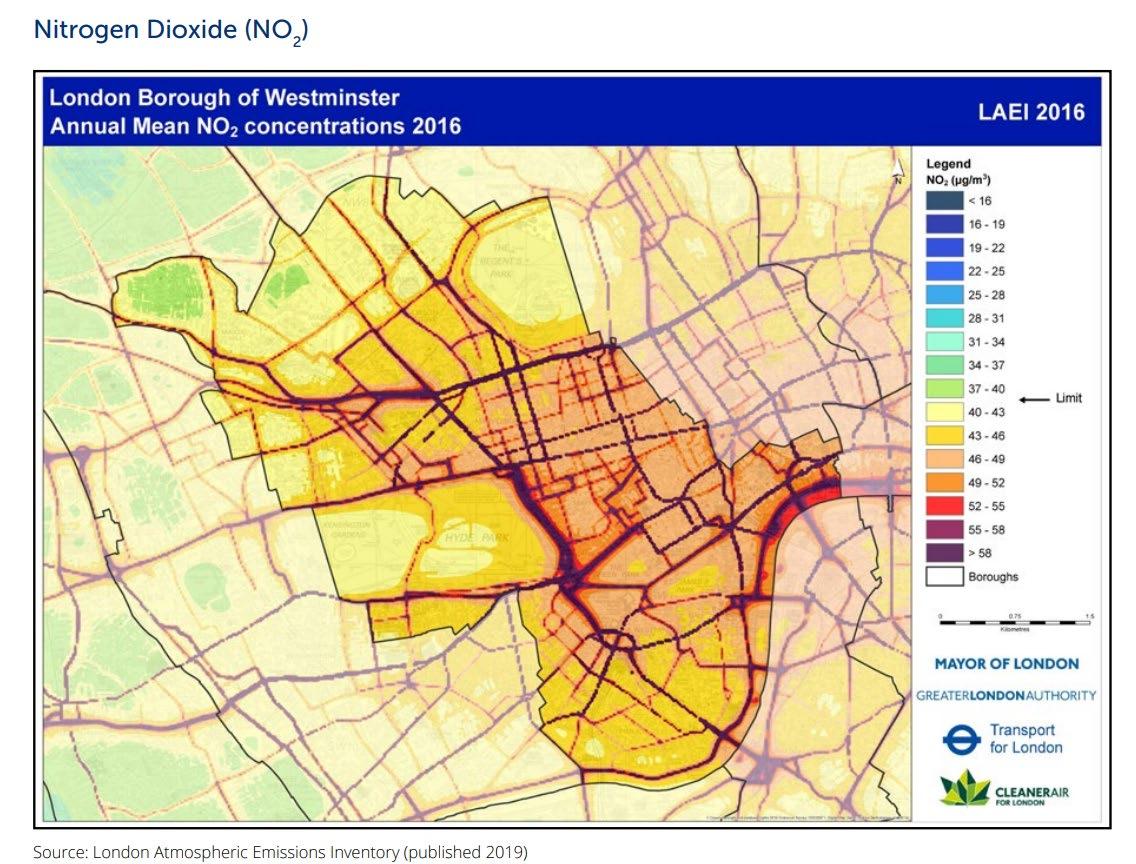

The below diagrams show the strong correlation between heavily congested traffic routes, and concentration of poor air quality throughout Westminster. It is important to monitor areas of known high pollution levels to be aware of the health risks to residents as well as regular visitors, to change behaviours and to encourage developments which will mitigate the effects of poor air quality.

Related Links:

Figure 22: Westminster annual mean particulate matter PM2.5 concentrations 2016.

Figure 23: Westminster annual mean nitrogen dioxide concentrations 2016.

• Air Quality data is available on the London Air Quality Network (London Air Quality Network)

• Breathe London (Breathe London)

• Diffusion tube data in our yearly reports regarding air quality data – for example WCC Annual Status Report 2020 Final.pdf

Micro-climate Guidance:

A. Public realm proposals and any development which will impact the public realm, should clearly demonstrate they have sensibly responded to and improved the specific micro-climates of the area.

B. It should be noted that microclimates differ at locations and will likely have separate considerations to be assessed and reviewed, therefore assessments should be undertaken individually.

C. Where new development or public realm schemes create a new microclimate, any negative impacts of said microclimate should be mitigated with immediate effect.

D. Seasonal change should be considered when designing an open space or brining forward development that will impact the public realm. This is to ensure alterations are robust throughout the year, certain elements within the space may be incorporated to address seasonal needs.

E. Materiality is also key to microclimates in relation to seasonal change. Opting for materials that are quick drying, antiskid/slip, or materials which do not create unpleasant glares such as metals or glass are important considerations when choosing the m aterial palette of a public realm scheme. Similarly, materials which do not overheat in the sunlight which can exacerbate the urban heat island impact, such as concrete and darker paving materials including asphalt.

F. Increased greening within the public realm can assist with heat absorption

Acoustic Comfort / Environment

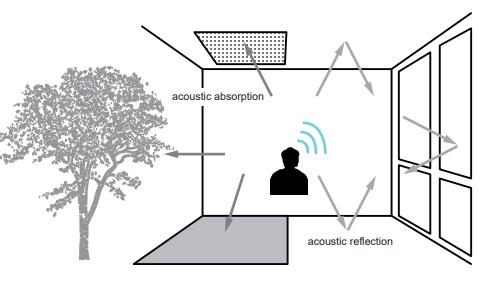

‘Soundscape’ describes the quality of the acoustic environment as people perceive it. In the city, the soundscape is broad ranging, but there are ways to mitigate the impact of harsher sounds when developing a public realm scheme by shaping the streetscape. The approach to effective sound scaping is influenced by the balance of unwanted sound (noise), natural sounds and the visual environment.

Types of sound that are experienced in an urban environment

In Westminster the dominant noise sources are traffic, sirens, and construction all of which detract from a balanced soundscape. Positive aspects to the soundscape in Westminster include birdsong, running water, human noise, trees rustling and unique sounds to Westminster (such as the chiming of Big Ben).

Mitigating the impact of unwanted noise is key to a successful acoustic microclimate. Effective sound scaping will increase the use of the space, encourage longer dwelling periods, and also offers crossover benefits to other aspects of the microclimate like air quality and visual amenity.

Where there is scope, controlling traffic noise is an important step in urban design and in achieving a more balanced soundscape. Legislation to reduce tyre noise is addressing this balance and low noise road surfaces can offer even greater benefits. Government plans to phase out the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2035 will also reduce traffic noise at lower speeds.

Traffic calming measures, timed pedestrianisation and traffic free neighbourhoods all provide enormous benefits to the local soundscape. Car free areas are becoming more common in European cities with particularly successful examples in Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Brussels.

The sound insulation effect of vegetation in urban environments is small, with the reductions ranging from 5 to 10 decibels (dB) Increased greening and planting have a greater impact on people’s perception of sound and as a result the soundscape is more likely to be considered positively. In addition, if road traffic is well screened visually this can have a large impact on perception.

Noise Guidance:

Where noise cannot be controlled and barriers, screening and absorption are used to mitigate the impact, the following should be considered:

A. Using water or artificial masking noise as an acoustic camouflage.

B. Increasing the distance between traffic and seating or paths.

C. Facing seating away from busy areas and roads.

D. Noise barriers, green walls, or green barriers at the roadside to mitigate noise levels.

E. Using absorbent materials for paving such as resin bound or rubberised materials.

F. Absorbent features on nearby buildings or structures such as green wall panels, complete green walls, green roofs, planting, and other absorbent materials such as acoustic panels.

G. Using buildings to screen traffic noise with the best examples being enclosed courtyards.

H. The City Council has introduced designated ‘ Tranquil Open Spaces’ in the city that are protected from intrusive noises largely from development.

Related links:

• Noise and Vibration in Environment SPD 2022