this edition

ColumbusBarAssociation

EditorialBoard

Chair

Caitlyn Johnson

Joshua Cartee

Lisa Critser

Matthew Jalandoni

Janyce Katz

Garth Robotham

Melanie Tobias

Lexi Foster

1 Four Ways Lawyers Can Enhance Mental Well-Being and Professional Effectiveness

Scott R. Mote

7 Workplace Investigations: When, Who, What, Where, & How

Kent

Anders

7 Lawyers with Artistic License: Taylor G MacDonald Joshua Cartee

Jan E. Hensel

5 Supreme Court Reverses Sixth Circuit Standard for Employees Alleging Reverse Discrimination

Kevin R. Kelleher

1 Navigating Employee Political Expression: Legal and Practical Considerations for Ohio Employers

Laura Repasky

79 DEI in the Crosshairs

Scott DeHart

85OSHA Inspections: What Every Attorney Should Know Before the Knock at the Door

Amy Flowers

91 The One That Got Away: Promissory Estoppel and the Family Medical Leave Act

Helen M. Robinson

97Key Takeaways from Early EEOC Suits Under the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act

Colleen Koehler

Interested in writing? CLE credit eligible. Have a theme idea? Email publications@cbalaw.org for more information. The Winter 2026 Issue will feature articles on Corporate & Transactional Law. The Spring 2026 Issue will feature articles on Immigration Law.

By Kelli Amador

I was standing outside of my car in 2016 the first time I remember being called a racial slur. A bright sunny day in fall, someone had backed into my car, and I waited for the police to write a report. A man in a truck passing by rolled down his window to call me an ugly word for someone who is undocumented. At first, I didn’t realize that he was talking to me — I was standing near my parked car dressed in a suit, hair and makeup done for court, on my way to work. Too shocked to give way to fear, I didn’t even realize he was yelling at me until he had already driven away. What could make a stranger so bold as to single me out without knowing a thing about me?

Hispanic Heritage Month runs from September 15 to October 15 every year. Nationally, firm statistics on Latinos in the law are sobering: NALP reported in 2024 that 3.12% of partners at law firms were Latinx and 1.12% of those were Latina women.[1] Most Latinx professionals know that we may have to be the “first” that someone meets: first Latinx attorney, corporate lawyer, board member, or professional. But as our numbers grow, so does the strength in our community.

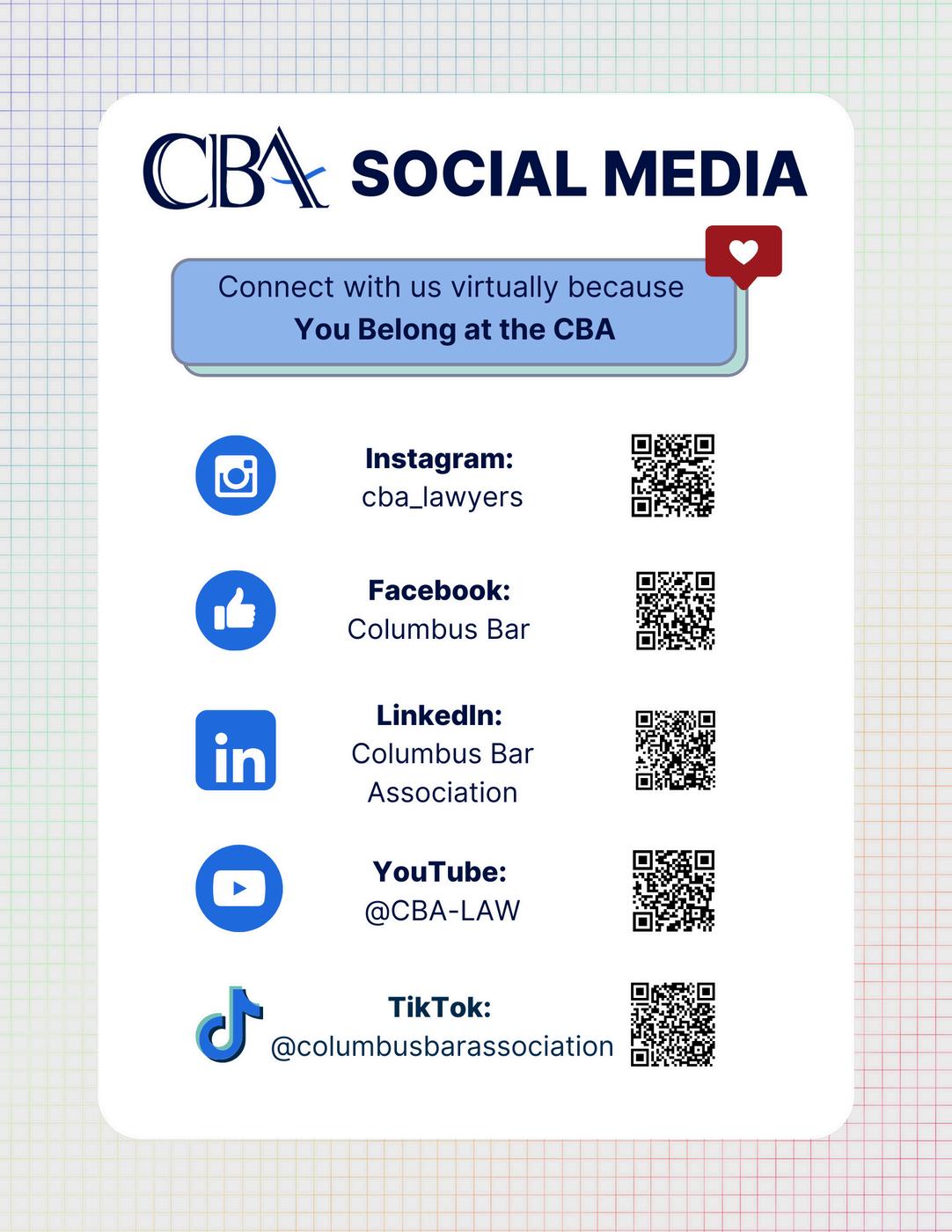

As I reflect on my own heritage, and my position in the community this month, I cannot help but be grateful for the opportunities given to me by the Columbus Bar Association. As a second-generation American and first-generation college and law school graduate, I am the first Latina to serve as President of the Columbus Bar Association — one of the highest honors of my life. Sworn in by Judge Marilyn Zayas, the first Latina appellate judge in Ohio, she reminded me, and the audience, how our differences are strengths and pave the way to success.

How right she was. I would be nowhere without mentors and support of people in my community. I joined the CBA when I was a freshly barred attorney at the instruction of my mentor: “The bar gives us so much,” she said, “it’s our duty to give back to it.” Dutifully, I’d march to the old building, sneak past the security guard into the elevator, and attend lunchtime meetings and Sidebars celebrations. The words, perhaps

forgotten by her, have echoed in my head at every bar event I attend. Attorneys serve an important role in our community: we bridge the gap between the public and the law. Attorneys from diverse and underrepresented groups understand our additional responsibility of being the “firsts.”

My mentor at Dinsmore once said our position means that once you make it up, you must reach back to pull someone up behind you. The work does not end once you “make it.” Through the bar, I have been given the opportunity to connect with my community and give back to it through mentoring and service. A self-policing profession, lawyers are also

responsible for enriching the profession through inclusion of historically underrepresented groups. The CBA continues one of the oldest diversity clerkship programs in the country a model so successful other bar associations mirror it in their own cities — to provide legal work experience for underrepresented law students from all backgrounds. Representation matters. Diversity, equity, and inclusion matter. Iron sharpens iron. While there is strength in our differences, there is endless support in our community as well.

It seems forever ago that I was standing outside of my car shocked by one emboldened man so let me instead embolden you, dear reader. You have the opportunity to give back to the community too — a chance to be mentored, to be a mentor, to forge valuable relationships, to give back to the community, to help police our profession, to contribute your knowledge to substantive law and it starts with your membership to the Columbus Bar Association. A reciprocal force, the bar has been there for me in every stage of my career. The CBA exists by and for attorneys like you. Come find your community with us.

[1] National Association for Law Placement, 2024 Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms 24 (Jan. 2025), https://www.nalp.org/uploads/Research/2024-25 NALPReportonDiversity.pdf.

JaneStempelArata

JoanneS.Beasy

DavidS.Bloomfield,Jr.

ThomasJ.Bonasera

SandraE.Booth

JamesH.Bownas

WilliamJ.Browning

WilliamL.ByersIV

SandraCarrillo

W.JeffreyCecil

MarkC.Collins

RonaldE.Davis

ShaneM.Dawson

RichardS.Donahey

RobertD.Erney

HenryL.Fein

JohnC.Fergus

StephenC.Fitch

RonaldA.Fresco

ScottN.Friedman

PeterJohnGeorgiton

JackG.Gibbs

PaulGiorgianni

DavidA.Goldstein

DanielRobertGurtner

DimitriosG.Hatzifotinos

BarronK.Henley

DouglasE.Hoover

CynthiaEllisHvizdos

RichardB.Igo

FrederickM.Isaac

VickiL.Jenkins

JohnS.Jones

MichaelS.Jordan

RussellA.Kelm

RobertW.Kerpsack

RussellW.Kessler

AllenS.Kinzer

KennethR.Kline

JenniferChristinaLee

RichardL.Levine

ScottT.Lindsey

ThomasK.Lindsey

AnnWhitlowLippman

DavidK.Lowe

MichaelD.Martz

WalterW.Messenger

DavidP.Meyer

RichardF.Meyer

JayE.Michael

ScottR.Mote

StephenA.Moyer

JohnC.Nemeth

ColleenK.Nissl

KimberlyD.Nocera

WilliamA.Nolan

JamesEvansRoberts,Jr.

RonaldL.Rowland

PhilipP.Ryser

JamesA.Saad

MichaelD.Saad

CharlesA.Schneider

KimberlyCalleryShumate

CarlD.Smallwood

JustinSolze

RobinL.Strohm

IraB.Sully

AracelyTagliaventi

J.TroyTerakedis

DavidH.Thomas

CharlesE.Ticknor

MelanieR.Tobias-Hunter

WilliamJohnWahoff

CharlesC.Warner

ScottN.Whitlock

BradleyB.Wrightsel

BenjaminL.Zox

ChristopherT.O'Shaughnessy

DavidC.Patterson

SamuelA.Peppers

WilliamG.Porter

FrankA.Ray

SusanD.Rector

By Jill Snitcher

Attorneys know better than anyone that doing nothing can be problematic a missed deadline, an unanswered filing, or a client left without counsel. Each choice not to act carries consequences. The same is true when it comes to the Columbus Bar Association (CBA). Choosing not to join, and leaving it to “others,” isn’t just opting out. It’s a decision with real costs for you, for your peers, and for the profession itself.

Maybe you’ve reached a place in your career where you have achieved success and find yourself very busy, with little time to refine your skills or build a bigger client base. You’ve built relationships with everyone in your circles, and you have little capacity to do anything more. You’re just too busy.

The Columbus Bar Association isn’t asking you to do more. As a legal professional you have a responsibility to maintain high standards of practice and conduct. Being a member of the bar association is a commitment that ensures your voice helps shape the future of the profession and ensures that lawyers have a seat at the table when local rules, practices, and policies are being shaped. Clients respect lawyers and law firms that engage with the profession at the local level where they live and work.

It’s tempting to think: “My membership doesn’t matter. The big firms will handle it.” But when too many attorneys leave their responsibility to others, the result is imbalance. The bar becomes associated only with the few who carry the weight, rather than representing the full spectrum of Central Ohio’s legal community solo practitioners, small firms, in-house counsel, and beyond.

The truth is simple: if everyone assumes someone else will do it, it’s not long before no one does.

When attorneys sit on the sidelines, the consequences ripple outward:

Eroded credibility. Membership signals accountability and professionalism. Fewer members weaken the collective reputation of the bar.

Lost influence. Without broad participation, the CBA’s voice in advocacy and community issues grows quieter, leaving decisions to be made elsewhere.

Fewer resources. Dues fuel networking, mentorship, and professional resources. Shrinking membership means less support for everyone.

A weaker future for young lawyers. The next generation relies on the CBA for connection and guidance. Without a strong bar, they enter a fractured community.

The CBA exists today because generations of attorneys before you believed in building something larger than themselves. They invested in an institution that connected peers, raised standards, and protected the profession. That legacy doesn’t survive on its own it survives because attorneys continue to step forward and say, “This profession matters.”

Membership is not just about what you receive in return. It’s about the statement you make: You are committed to the strength, credibility, and future of the legal profession in Central Ohio.

The cost of doing nothing is paid by all of us. The only question is whether we leave it to others or work as a whole to strengthen the profession we’ve built our careers upon.

ErodedCredibility

In law, doing nothing isn’t neutral. Miss a deadline, ignore a filing, or fail to object you pay the price. The same is true if we aren’t active in the Columbus Bar Association.

When attorneys choose not to support the CBA, they aren’t just saving a few dollars. Their absence weakens the very community they rely on and need.

From its admissions and ethics work to operating as the legal hub of Central Ohio, the CBA is the infrastructure that holds our legal community together.

Membership isn’t about what you get it’s about what we build together. But it only works if we all step forward. Doing nothing has a cost. It’s a cost we can’t afford.

ByKentMarkusandEmilySollars

On January 1, 2025, new provisions of the Ohio Rules for the Government of the Bar regarding professional liability insurance became effective. All attorneys are encouraged to carry liability insurance it’s better for them and for their clients if the unfortunate need for its use arises.

Before this year, attorneys who did not carry liability insurance were obligated to tell their clients so that clients could make an informed decision about the

retention of an attorney without such insurance. That rule has not been as effective as some might have hoped in protecting clients in circumstances when their attorneys badly fail them. The new rules, effective this year, add another layer of client protection.

Ohio attorneys, with certain very limited and enumerated exceptions, must now, in their biennial registration with the Ohio Supreme Court, provide two new types of information. First, they must provide the names of all

other states or territories of the United States in which the attorney is admitted to the practice of law. Second, attorneys (with certain narrow exceptions), when registering for active status, must now provide information about: (1) whether the attorney has professional liability insurance on the date of registration, and (2) whether the attorney has a plan to manage the attorney’s work or caseload in the event the attorney becomes temporarily or permanently unable to do so.

Although not, by any means, the only way to effectuate a plan associated with temporary or permanent disability, the Columbus Bar encourages all attorneys to consider making use of its free Advance Succession Registry. Using this registry, any attorney can designate another Ohio-licensed attorney to provide immediate assistance to an attorney’s clients if the attorney is no longer there to help. By joining the registry, attorneys decide

who will protect their clients. For more information, or to sign up for the CBA’s Advance Succession Registry, click on the link above or call the Columbus Bar Association.

Beginning with registrations for the 2025-2027 biennium, any attorney who lacks malpractice insurance will be denied registration for the biennium until such insurance is obtained (and the Court is so notified) or until the attorney completes the proactive management-based regulation (PMBR) curriculum on the ethical operation of a law practice developed by the Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC). Newly admitted attorneys are exempt from the requirement for their first biennium registration.

The rule provides that the Office of Disciplinary Counsel’s PMBR course shall be free and CLEaccredited. Substantively, it is, per the rule, to “assist attorneys in developing ethical

Attorneys reporting the purchase of professional liability insurance when seeking reinstatement must provide documentation showing the name of the insurer, the policy number, and the amount and date of coverage. The Ohio Rules for the Government of the Bar have long infrastructures to improve the delivery of legal services and client relations and enhance the provision of competent and costeffective legal services to prevent violations of the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct.” The new governance rule provides that the curriculum may include but is not limited to — continuing legal education on the ethical operation of a law practice. The ODC course must be open to any attorney admitted in Ohio. The rule also provides that all information related to an attorney’s participation in the curriculum is confidential, except that ODC may report proof of completion and aggregate statistics from the curriculum.

required that Ohio attorneys must either carry professional liability insurance or expressly notify their clients that they do not do so. The new provisions of Ohio Gov. Bar Rule 1, described above, help assure that clients are knowingly making the election to hire an attorney without liability insurance and that attorneys who choose not to obtain such insurance have a plan for their clients should they become incapacitated and have completed specific continuing education requirement aimed at minimizing risk to clients from uninsured attorneys.

By Delaney Barr-Brown

As lawyers, we have a duty to advocate for our clients and represent them to the best of our ability. Often, this plays out in our communications with opposing counsel, in arguments we make to the Court or other governing body, and in our legal research and writing. This is what we are taught in law school and what our “on the job” training gets us familiar with afterward.

That is not where our advocacy for our client begins, however. Our representation and advocacy starts the

moment a potential new client (PNC) reaches out to us. That is one of the greatest moments of impact that a lawyer can have on a client and usually one of the hardest times for the PNC.

PNCs who come to us can be part of many diverse, protected classes, and those facets of their lives often overlap.

A client’s experiences as a person of several protected classes can impact

their risk of discrimination, retaliation, and other adverse employment actions that may be traumatic to them.

To provide an example from employment law, a PNC may have just been fired due to their race, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, disability, age, or other protected class. They may have experienced harassment at their job based on these parts of their identity. They could have been retaliated against for reporting illegal conduct or a safety violation. Often, a PNC is going through one of the hardest times in their life and has experienced trauma as a result.

To be able to represent our clients to the best of our ability, we need to be aware of what they are going through and adapt our policies and procedures accordingly. Using an intersectional lens is one approach to better understand PNCs and ensure that you are able to get what information and cooperation you need at the same time.

LGBTQ+ women because these individuals’ concerns were not being addressed by either the mainstream women’s movement or the civil rights movement in the 1970s.[1] The problem with viewing this group through only one perspective either focusing on gender or the fact that they were of a minority race meant that the unique circumstances of those people at different axes of oppression were overlooked.

This exact problem occurred in an employment discrimination Title VII case, DeGraffenreid vs. General Motors, 413 F.Supp. 142 (E.D.Mo. 1976). The court determined that since GM did not discriminate against black men or white women, the black women that alleged gender and race discrimination could not have been discriminated against. However, the court viewed the situation through a single lens, meaning it was not able to recognize the unique circumstances of discrimination that black women experienced in that case.

The term “intersectionality” is based on the Combahee River Collective’s framework; the organization focused on the difficulties experienced by Black This case, among a few others, prompted Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s legal analysis in the 1980s. Dr. Crenshaw

explained that it would take an intersectional lens — one that focused on the different points where axes of oppression overlapped — to understand what the plaintiffs in these situations were going through. Intersection is defined as “the ways that numerous aspects of our identities, including race, gender, social class, sexual identity and disability, overlap and combine in ways that shape individual experiences, including experiences of privilege and/or oppression.”[2]

People who live at the intersections of axes of oppression are more likely to face discrimination, harassment, hostile work environments, retaliation, and other adverse actions. Not only does this impact their economic stability through their employment, but it can also impact the other areas of their lives as outlined in the Social Determinants of Health chart:

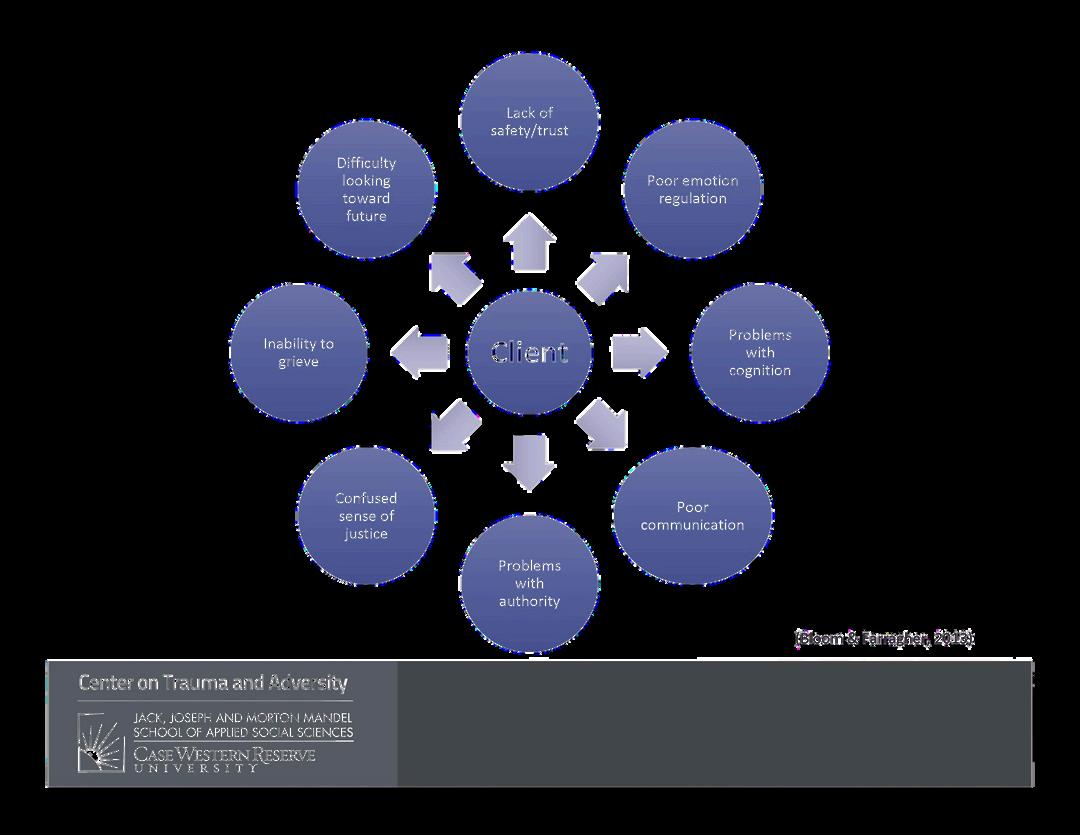

These experiences often result in trauma, which impacts a PNC in many different ways. Trauma can be defined as “An EVENT, series of events, or set of circumstances that is EXPERIENCED by a person as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening, and has lasting EFFECTS on the individual’s physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”[3]

What does this mean for our PNCs and how they interact with attorneys? Trauma can impact many different facets of a PNC’s life, including how they communicate with an attorney, their demeanor, their memory, their ability to define what they want out of representation, their ability to trust their attorney, and more.

Knowing that, how can we be better advocates and representatives for our clients from the PNC stage through the end of their case? We can adjust our processes to accommodate what they are going through, establish trust early on, and encourage them to take an active role in their case.

There are six core principles that can assist us to do so:[4]

Awareness: Everyone knows the role of trauma;

Safety: Ensuring physical and emotional safety;

Trustworthiness: Maximizing trustworthiness, making tasks clear, and making appropriate boundaries;

Choice: Respect and prioritize the client’s choice;

Collaboration: Maximize collaborating with and sharing power with clients; and

Empowerment: Prioritizing client empowerment where possible

Incorporating these principles into your practice can help address some of the difficulties that clients may have and also assist you throughout their case.

What are some concrete ways to do so?

Ensure that the first people speaking with the PNC know about trauma and how it may impact their demeanor, memory, and communication style;

Set up a “goals call” with the PNC to ensure that you can get any updates from them that may change your analysis, set boundaries about how you will communicate with them and when, get clarification on what their goals are and if your representation options match what they want, and build trust with your client from the very beginning of your representation;

Create templates for different stages of representation and use them after you begin representation so that your client knows what to expect, has something to refer back to in

between calls with you, and is in the loop throughout their case;

Set up regular check-in times with your client so that they have a say in their case, feel as if their voice matters, and are an active participant when you need them to be; and Have meetings with your client before big events (depositions, hearings, trial, etc.) to walk them through what to expect, answer any questions, discuss updates about their case, and make sure that they understand their role in the process.

By using these examples, you will 1) create trust with your client; 2) provide reliability, which helps establish safety and address some of the trauma symptoms outlined above; 3) build in choice and collaboration; and 4) empower your client during one of the hardest times of their life.

You will also receive 1) a more cooperative client during difficult times, like discovery or deposition preparation; 2) clearer communication and availability when important deadlines come up; 3) an advocate

during your client’s deposition or discovery answers; 4) fewer anxious emails and panicked phone calls from your client; and 5) more good reviews and referrals after representation ends.

It is worthwhile to look at how intersectionality, trauma-responsive representation, and the resources provided herein can help you and your clients.

Please feel free to reach out to me if you want to discuss things further; I am happy to be a resource or provide one!

1 See identiversity org, Digging into Intersectionality, https://www identiversity org/topics/lgbtq-identities/digging-intointersectionality (accessed July 18, 2025)

2. Id.

3. This definition came from a presentation titled “Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self-Care” given by members of the Case Western Reserve University Center on Trauma and Adversity in May 2021 For more information on the Center, visit https://case edu/socialwork/traumacenter

4 See New York State Office of Victim Services YouTube Channel Playlist on Trauma Informed Lawyering, available at https://www.youtube.com/@NYSOVS/playlists. See also Case Western Reserve University Center on Trauma and Adversity, What Is Trauma and Adversity,https://case edu/socialwork/traumacenter/ about-us/what-trauma-and-adversity (accessed July 18, 2025)

r-Brown

nn Firm LLC

egal.com

ByAndersJ.Miller

As a former high school English teacher who left the classroom to become a student-side education attorney, the education space is one I have been in for over ten years. My role now is as an education attorney who supports students and their families as they navigate special education concerns, Title IX cases, disciplinary issues, and their student rights generally. Although I have seen improvements to our education system, there is much more we need to do to meet the needs of our students. This need for reform in Ohio should start with moving away from our heavy reliance upon exclusionary-focused discipline, which disproportionately punishes our most vulnerable students, and towards restorative- focused discipline.

Exclusionary discipline is a consequence for a student that results in their removal from the normal educational setting or activities. The exclusion could be an in-school suspension, an outof-school suspension, or an expulsion.[1] Ohio Revised Code 3313.661 requires written policies regarding discipline for student misconduct that occurs on district property or occurs off district property but is connected to activities or incidents that do occur on school property.[2]

Excluding students from school has negative short- and long-term impacts on students, families, and schools. Students miss their schoolwork during exclusion and that exclusion rarely addresses the root causes of behavior.[3] Research also shows that classrooms that use exclusionary discipline for minor infractions have lower academic achievement.[4]

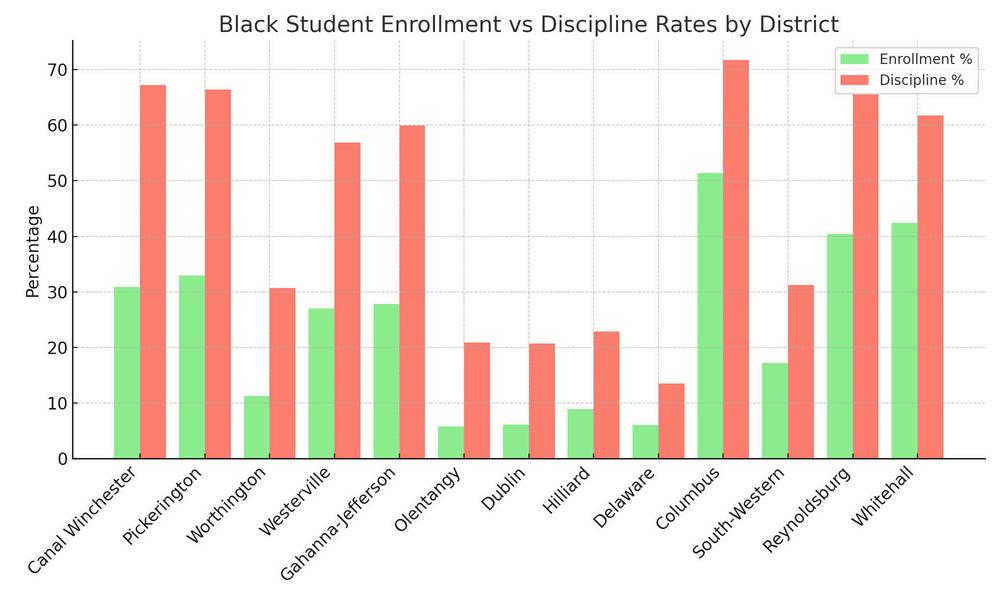

The charts used in this article are based on compiled data from the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce’s School Report Cards, which can be accessed at The charts used in this article are based on compiled data from the https://reportcard education ohio gov/download

Concerningly, exclusionary discipline is also disproportionately implemented. Students who come from lowincome families, non-white students, and students with disabilities are more likely to receive harsher and exclusionary discipline than other students for the same behaviors.[5]

Recent Central Ohio district data underscores these disparities even more starkly.[6] In Canal Winchester, Black students are only 30.9% of enrollment but account for 67.2% of all discipline occurrences making them 4.76

times more likely than white peers to be disciplined. In Pickerington, Black students represent 32.9% of enrollment but 66.5% of discipline, a 4x disproportionality. Even in suburban districts often viewed as high-performing, such as Worthington, Olentangy, and Dublin, Black students were between 2.5x and 3.2x more likely to face discipline than white peers. At Columbus City Schools, the state’s largest district, over 71% of all discipline cases were against Black students despite them being just over half of the enrollment.

struggle academically, grade, drop out from sc become involved in the justice system.[7] Acco is unsurprising that students with disabilit only a 69% graduat putting Ohio forty-three sixty-one states and under this metric.[8 graduation rate for Black is 75%, which is 15% lo graduation rates fo students.[9] Local disparities such as 4–5 likelihoods of exclusion students in nearby dis almost certainly contr these statewide outcome

Students with disabilities also face disproportionate exclusion. Columbus City Schools recorded 1,583 discipline occurrences involving students with disabilities, South-Western 458, Whitehall 347, and Reynoldsburg 183. Several suburban districts reported far fewer, or even zero, suggesting either underreporting or systemic inconsistency. Statewide, the pattern is consistent: students with disabilities are disciplined at far higher rates than their representation in the student body would predict. The long-term impacts on the excluded student are significant: that student is more likely to Ohio must, and can, do better. To

do so, we need to work together to promote policies that effectively address these inequities. Ohio’s disciplinary processes must be informed by restorative practices. These practices focus on strengthening prosocial skills and building relationships between students and their communities using conflict resolution.[10] In such restorative environments, the goal is to align the consequences for a student’s actions with addressing the harm those actions caused while learning from them.[11]

When I taught high school, these realities shaped my approach. I rarely submitted write-ups for removal even when pressured by colleagues to do so. Instead of outsourcing discipline to the main office, I focused on having students repair the harm they caused often through creative, classroom-based responses. When a student told me to “f--off” during class, I had him eat lunch with me for a week so we could learn how to better work together. When another threw a Chromebook across the hallway,

he became responsible for caring for and cleaning classroom devices for the following weeks. These behaviors would likely have earned multi-day suspensions elsewhere. But I found that restorative responses those that addressed both harm and underlying causes were far more effective in reducing repeat incidents and supporting student growth.

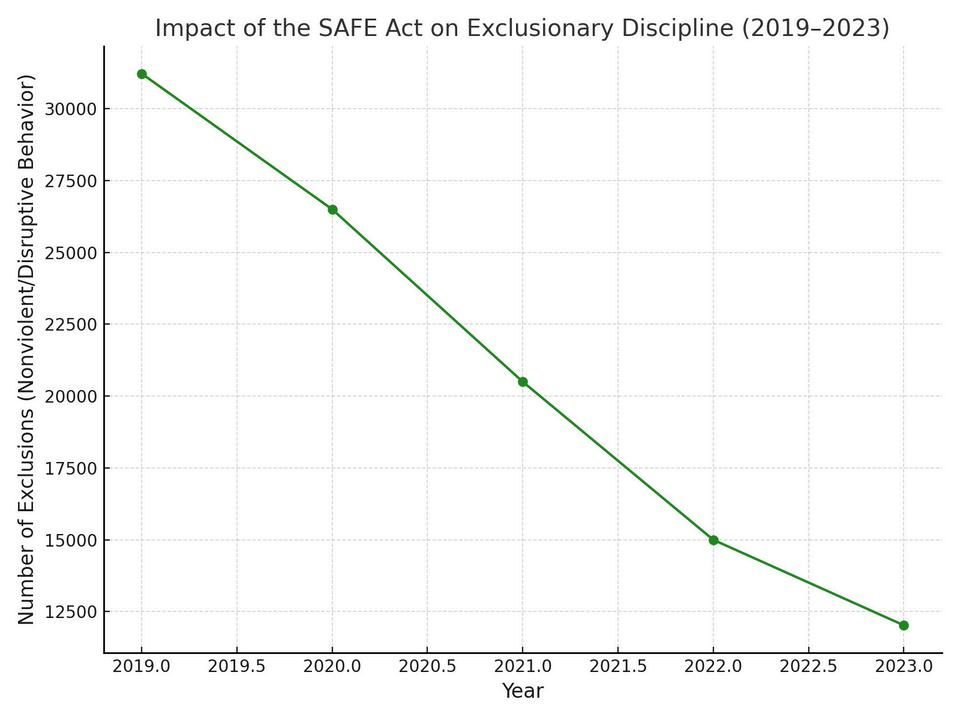

There are steps that we can take to address our discipline divides. Ohio should expand the Supporting Alternatives for Fair Education Act (SAFE Act) beyond third grade. The SAFE Act prevents schools from imposing exclusionary discipline on students in third grade or earlier who engaged in nonviolent or disruptive behavior and pose no significant danger to safety. The

law has been effective: in 2019, there were 31,224 such exclusions; by 2023, that number had dropped to 12,025. The SAFE Act also increased funding for behavioral supports to address underlying needs. Expanding it to include upper elementary and middle school students would help reduce exclusion when it is most commonly imposed.[12]

Additionally, Ohio must restore compliance with federal data requirements under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The new Central Ohio data makes clear why: without accurate reporting by race and disability, the students most affected by exclusion may remain invisible in state accountability systems. Even amid political shifts that seek to downplay disparate impact, IDEA remains federal law. The Ohio Department of Education and Workforce must follow it. Otherwise, the very students the law was designed to protect may get excluded from their education entirely.

As legal professionals, we are uniquely positioned to influence this system. You can assist students facing exclusion — either directly or by referring them to attorneys with education expertise. You can advocate at local school board meetings or testify at the Statehouse in support of equity-focused reforms. You can even run for school board yourself to help shape the policies driving these disparities. There are many ways to join this work, and all are urgently needed.

We must begin treating exclusionary discipline as the harmful, inequitable practice that the data and our experience show it to be. And attorneys must be part of that change.

Anders J. Miller

[1] Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Ohio School Discipline https://education ohio gov/Topics/ Student-Supports/Safe-and-Supportive-Schools/OhioSchool-Discipline (accessed July 29, 2025) (explaining Ohio law regarding school-related discipline)

[2] See id.

[3] Leung-Gagne, McCombs, Scott & Losen, Pushed Out: Trends and Disparities in Out-of-School Suspension, Learning Policy Institute (Sept 30, 2022), https://learningpolicyinstitute org/product/crdc-schoolsuspension-report

[4] Wang, Scanlon & Del Toro, Does Anyone Benefit from Exclusionary Discipline? An Exploration on the Direct and Vicarious Links Between Suspensions for Minor Infraction and Adolescents’ Academic Achievement, 78 Am Psychologist 20-35 (Sept 29, 2022), https://pubmed ncbi nlm nih gov/36174178

[5] Jacqueline M Nowicki, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities, U.S. Government Accountability Office (Mar. 22, 2018), https://www gao gov/products/gao-18-258

[6] The statistics in the following two paragraphs were compiled from report card data reported between 2019 and 2024, which can be found at Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, School Report Cards, Download Data, https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/download. See also Kim Eckhart & Katherine Ungar, 2024 State of School Discipline in Ohio, Children’s Defense Fund Ohio 11-13 (Mar 13, 2024), https://www childrensdefense org/wpcontent/ uploads/2024/03/2024-State-of-School-Discipline-inOhio pdf; Tanisha Pruitt, State of Ohio Schools 2023, Policy Matters Ohio (Oct. 3, 2023), https://policymattersohio.org/ research/state-of-ohioschools-2023/# edn8.

[7] Leung-Gagne, et al , supra note 3

[8] Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Ohio’s Special Education Determination, https:// education ohio gov/Topics/Special-Education/SpecialEducation-Monitoring-System/State-Determinations (accessed July 29, 2025) (detailing the struggling graduation rates for students with disabilities)

[9] Institute of Education Sciences, High School Graduation Rates, https://nces ed gov/programs/coe/indicator/coi (accessed July 29, 2025)

[10] Sean Darling-Hammond, Fostering Belonging, Transforming Schools: The Impact of Restorative Practices, Learning Policy Institute (May 18, 2023), https://learningpolicyinstitute org/product/impactrestorative-practices-report

[11] Larry Ferlazzo, What Do Restorative Practices Look Like in Schools?, EducationWeek (Feb 27, 2024), https://www edweek org/leadership/opinion-what-dorestorative-practices-look-like-in-schools/2024/02.

[12] Eckhart & Ungar, supra note 6, at 7.

ByDawnHays

While recently working with a legal team, we explored what it means to exercise emotional intelligence in real time. During a break, one participant quietly pulled me aside. His voice was tight; his face pained.

“I have a brother with an intellectual impairment,” he said, “and one of my colleagues will say things ‘are retarded’ if something goes wrong or ask if someone ‘rode the short bus to work’ when they screw up. If I hear it one more time, I might go off.”

When I kick off my employee training sessions, I begin with a brief introduction both personal and professional so participants can see me as more than a lawyer or consultant. I share all kinds of things and often share that I am a mom and that my daughter has autism. I think my sharing of that information and then sitting through a two-hour workshop on assertive communication gave this person the context and connection he needed to share with me something deeply troubling him. Ironically, he had known his colleague for years, but it was in that moment — with a relative stranger that he felt comfortable to speak.

This is the reality in many workplaces, especially law firms. I’d even go so far as to say that at least for most Gen Xers and Boomers we weren’t raised by folks who were stalwarts at being direct while also being respectful. Growing up in an ESL household and being raised by a single immigrant mom who was also a steel worker, I can speak for myself when I share that I grew up thinking being assertive meant demonstrating dominance, often by being the loudest and most relentless.

We often find it easier to “go off,” stay silent, or talk to anyone except the person who needs to hear the message. It feels safer to avoid vulnerability than to risk it — especially in legal environments where we believe competence means never showing discomfort.

The unavoidable result? Dysfunction that quietly erodes trust, collaboration, and productivity.

Most of us were never taught how to address conflict with courage what researcher Brené Brown calls “rumbling with vulnerability.” Assertive communication and conflict resolution are not inborn talents; they are skills. And like legal advocacy or trial preparation, it can be taught, practiced, and refined until it becomes part of an employee’s repertoire and firm’s culture.

Having practiced both in the employment law and in HR arenas, I have seen first-hand how teams that are able to rumble with respect produce higher quality work-product. Every HR Business Partner who has ever worked for me can attest to the fact that we have rumbled. So often I needed additional context to move off of my

initial determination of a situation or they needed some missing elements to more fully understand why their approach wasn’t optimal. The point is that we had to be willing to disagree sometimes with passion — to try to get to the best outcome.

In the above provided scenario, the participant and I worked through a role-played, assertive response. I know everyone despises this. I do too. But I assure you it works. The brain doesn’t know the difference between the real thing and practice so anything we can do to help drive a direct and respectful conversation is worth it.

By Friday, the employee from the law firm had raised the issue with his colleague in his own words. He said “I’m sure you don’t mean to but when you say crap like that I cringe.” The result? His colleague was embarrassed, apologetic, and — even better — grateful that he had addressed it directly instead of escalating the issue. Both parties left that conversation feeling relieved and more

confident in their relationship for having addressed the issue.

I often hear partners and leaders say they want to improve communication, trust, and collaboration within their firms. But without an intentional strategy — and without training leaders at every level those aspirations rarely take hold.

Whether you work with the Columbus Bar Association or another provider, law firm leaders are wise to invest in workforce development programs that strengthen emotional intelligence, build trust, and foster a culture where difficult conversations happen constructively. The payoff isn’t just a healthier workplace — it’s better client service, stronger retention, and a team that’s ready to “rumble” when it matters most.

By Joshua Cartee

“Indulge your imagination in every possible flight.”

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

Sewing and embroidery began for Taylor MacDonald as a way to transfigure herself into a heroine in a Jane Austen novel. At first, she enjoyed the quaintness of crafting something new out of something tiny. That initial interest in the creation of small things by hand has evolved into a means of exercising her imagination: making articles of clothing for herself and family members.

After growing up outside Boston, Taylor’s interests in the quaint and romantic led her to study French literature. She earned a degree in French from Davidson College in North Carolina and then continued her graduate studies in French Literature at Indiana University in Bloomington,

Indiana. While obtaining her degrees, Taylor spent a semester abroad studying in Tours, France, located in the Loire Valley. Years later, Taylor would return to southern France to exchange vows with her wife, fellow attorney and CBA member Julia Konieczny. (The author of this article was pleased to serve as master of ceremonies.)

from a local home supply store, and turned it into a pillow that now adorns a spot in the bedroom of Taylor’s nephew (Ryan’s son). During the COVID-19 pandemic, Taylor took to hand-sewing face masks, but when that process became too time consuming, she bought a cheap sewing machine and started making not just masks but other articles of clothing. In particular, she made dresses for her niece (daughter of Taylor’s other brother, Brad), who was three years old at the time. Taylor has continued to make articles of clothing for her nieces and nephews.

For herself, she has made a one-piece Watermelon Sugar romper à la Harry Styles. But, Taylor says, she enjoys making clothes for her nieces and nephews the most because the clothing is more forgiving in terms of fit and the fabrics are more fun.

Taylor began an earnest pursuit of her creative outlet in 2004. Her brother, Ryan, had outgrown one of his favorite Boston Red Sox t-shirts (Trot Nixon, right field) but couldn’t quite bring himself to get rid of the shirt. Taylor took the shirt, bought some stuffing

“It exercises a different part of the brain from practicing law,” she says. “So much of the law is about critical thinking and crafting arguments or considering the implications of this contract provision or that contract provision. It’s also never ending. By contrast, making clothes is tactile and physical. It’s also a finite process and there is something really tangible to show for it at the end.”

By day (and sometimes night), Taylor is a practicing attorney at Dickinson Wright PLLC in Columbus, where she has practiced law since graduating from The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law in 2022. At Dickinson Wright, Taylor practices corporate law in the Mergers and Acquisitions practice group and occasionally dabbles in the cannabis and hemp space. She has written and published several articles on the interaction between state-level cannabis and hemp regulation and federal law. She greatly enjoys her practice area and the problem-solving that it brings.

When she needs a break from the practice of law, though, Taylor conjures up the image of a Jane Austen scene, indulges her imagination by firing up the sewing machine, and creates something entirely new.

By Scott R. Mote

The legal profession is inherently demanding, requiring constant analysis, decision-making, and a high level of intellectual rigor. At times you may find yourself consumed by past cases, difficult decisions, or the potential repercussions of your actions, but dwelling on the past or fearing its recurrence can lead to stress, anxiety, and burnout.

Cultivating a mindset rooted in the present, acknowledging thoughts without being controlled by them, and fostering gratitude can significantly enhance your mental well-being and professional effectiveness.

You might sometimes revisit past events whether it’s a trial that didn’t go as planned, an ethical dilemma, or a moment of selfdoubt. While reflection is essential for growth, excessive rumination can lead to anxiety and stress. The gravity of your role as a legal professional can create lingering doubts. While the past can offer lessons, it should not dictate present emotions or impair professional judgment.

One of the most critical aspects of mental resilience is recognizing that while you cannot control the thoughts that enter your mind, you do have control over how you process them. Instead of suppressing intrusive thoughts, you can acknowledge them and redirect focus to the present moment. For example, a thought such as “I ruined that person’s life,” might enter your mind. You do not have control over that thought, but you do have the power to challenge that thought. A practical way to achieve this is through mindfulness techniques consciously returning attention to the here and now rather than getting lost in the “what-ifs” of past cases or decisions. Simple practices like taking a few deep breaths before entering the courtroom or engaging in deliberate, undistracted reading of case files can anchor the mind in the present.

If you find yourself in a situation where you cannot get in the present, try the 5-4-3-2-1 grounding method, where you identify five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, one thing you can taste. By engaging your senses, this technique helps shift focus from ruminative thoughts to the current moment.

Stress is an inevitable part of your job, but learning to manage it effectively is crucial. When facing an overwhelming situation whether it’s a difficult client, a contentious trial, or a heavy caseload — engaging in mindful breathing can help. Try a simple box breathing exercise, where you inhale for four seconds, hold it for four, exhale for four, and hold for four. This can provide immediate relief from stress and refocus your mind.

Additionally, adopting a structured routine that includes exercise, sufficient sleep, and healthy nutrition can enhance resilience. Prioritizing self-care leads to better long-term performance and decision-making.

It is not unusual for lawyers to hold on to the burden of past actions, fearing that mistakes may define your reputation or career. However, growth comes from experience, including errors. Instead of fearing the past, reframe mistakes as stepping stones to wisdom. A helpful perspective is to ask: “What did this experience teach me, and how can I apply that lesson moving forward?”

For instance, you might dwell on a negative news article that was written about you. Instead of focusing on the perceived wrongdoing, shift your focus to

the skills you can gain from this experience, such as embracing constructive criticism, enhancing communication skills, and building resilience and emotional intelligence.

Gratitude has profound psychological benefits. Research shows that practicing gratitude reduces stress, increases resilience, and improves overall well-being.

You can incorporate gratitude into your daily routine through simple practices:

Reflect daily: At the end of the day, take a few minutes to list three things that went well, no matter how small.

Show gratitude: Express appreciation to colleagues, clerks, or staff for their contributions. Acknowledging the hard work of others fosters a more supportive and positive work environment.

Shift your perspective: When facing a difficult case, remind yourself of the privilege of advocating for justice and making an impact.

excel in your career, but also lead to a healthier, more fulfilling life.

You operate in a profession that demands constant intellectual engagement and decisionmaking. However, the mental burden of past cases, perceived failures, and fear of future outcomes can create significant stress and anxiety. By learning to stay present, acknowledging thoughts without being controlled by them, and practicing gratitude, you can cultivate resilience and maintain your well-being.

The law is built on precedent, b personal growth and men health require a focus on the he and now. Embracing mindfulness, reframing past experiences as learning opportunities, and integrating gratitude into daily practice can help you not only

It's important to acknowledge that the pressures of your role as a legal professional may lead you to seek solace in alcohol or other substances to manage overwhelming thoughts and emotions. If you find yourself confronting such challenges, consider reaching out to the Ohio Lawyers Assistance Program (ohiolap.org / (800) 348-4343) or the Judicial Advisory Group (JAG) (ohiolap.org/judges / (800) 3484343), a peer-based, confidential assistance program dedicated to supporting judges and magistrates with both personal and professional issues.

By Jan E. Hensel

Imagine the following scenario: you receive a call from a client — a longtime colleague who has recently moved to an in-house counsel position. Your client informs you that their company has received an anonymous hotline complaint alleging that the company’s Chief Executive Officer is engaged in an extra-marital affair with the company’s Chief Human Resources Officer. The complaint also alleged that,

because of the relationship, the CHRO is receiving preferential treatment. Your client asks for your advice as to how to handle this very sensitive issue. You advise the client that an investigation is warranted. Having very little experience with such investigations, your client asks you to give them an overview of the process, including the decisions that they must make and what to expect. Being an experienced

workplace investigator yourself, and eager to help your client navigate this highly sensitive situation, you provide your client with this overview of the process to share with their team.

Workplace investigations are a valuable tool for addressing a broad spectrum of work-related issues. Among them: (1) to resolve internal issues; (2) to comply with company policies; (3) to take advantage of the Faragher/Ellerth affirmative defense; and (4) to otherwise minimize liability. This situation falls squarely within No. 3 above: to take advantage of the Faragher/Ellerth affirmative defense.

In the 1998 companion cases of Faragher v. City of Boca Raton and Burlington Industries v. Ellerth, the Supreme Court addressed employer liability for sexual harassment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. In these cases, the Court recognized an affirmative defense to employer vicarious liability for sexual harassment that does not result in a tangible adverse employment action. To take

advantage of the affirmative defense, an employer must establish (1) that it exercised reasonable care to prevent and promptly correct any sexually harassing behavior in the workplace; and (2) the employee unreasonably failed to take advantage of any preventative or corrective opportunities provided by the employer or otherwise to avoid harm. Investigations into allegations of workplace sexual harassment are a critical tool in establishing that the employer took reasonable steps to prevent and/or promptly correct sexually harassing behavior in the workplace. As such, there are few if any allegations of sexual harassment in the workplace that do not warrant an investigation. In our hypothetical, an investigation is clearly warranted to protect the company from liability.

All investigations should be conducted as promptly as possible. An investigation is most effective when conducted closely in time to the events being investigated. Interim measures may need to be put into place for protection of parties involved. Memories fade; people move on. Time is of the essence.

There are many factors to consider when selecting the appropriate investigator. Most importantly, the investigator must be impartial, unbiased, credible, and experienced.

Many investigations can be conducted in-house: by members of the human resources or internal audit teams who are trained in conducting workplace investigations. Because both the CEO and CHRO are targets of the investigation in the current hypothetical, an external investigator will be required someone whose future employment cannot be impacted by the CEO or CHRO.

Corporate Counsel or an Independent Third-Party Investigator

When an external investigation is needed, it is not uncommon for a corporate client to ask their go-to outside counsel to conduct the investigation. Before accepting this assignment, however, corporate

counsel must evaluate whether an independent third-party investigator would better suit the client’s needs.

In our hypothetical, it is likely that members of your firm have interacted with the CEO and CHRO. If so, the independence of an investigator from your firm could be questioned. In addition, if the results of the investigation are used in future litigation, you and your firm could be prohibited from representing your client. Under Ohio’s Rules of Professional Responsibility, the lawyer who served as the investigator would be precluded from acting as both an advocate and a witness in the ensuing trial. In cases where the lawyer/investigator’s conduct would create a conflict of interest, the investigator’s law firm could also be precluded from representing the company in litigation where the investigator will serve as a witness.

The first step in developing the strategy for the investigation is to determine the appropriate scope. In our

hypothetical, the scope could be limited to whether the CHRO is receiving preferential treatment because of her affair with the CEO. However, there may be circumstances in which a broader scope is warranted. If, for example, there have been prior complaints that the CEO has engaged in inappropriate workplace conduct with female subordinates, then the scope of the investigation may be whether the CEO has engaged in inappropriate workplace conduct with members of the opposite sex and, if so, whether his conduct violated the law and/or company policies. The scope defines the conduct of the investigation.

After the scope has been agreed-upon between the investigator and the client, the investigator must develop the investigative plan. The plan is the investigator’s tool for ensuring that the investigation is thorough and organized. The plan should include, at a minimum, the following elements: (1) definition of the scope of the investigation; (2) documents to review; (3) witnesses to interview; and (4) key questions to ask of each witness. Prior to conducting any interviews, the

investigator should review the complaint and company policies implicated by the complaint or related to the potential violation being investigated. If there are prior complaints of a similar nature, documents related to such past complaints should also be reviewed, as should any relevant written communications between the complainant and the alleged wrongdoer. The investigator may want to review the personnel files of both the complainant and the accused. While every investigation is unique, a careful review of relevant documents is essential to equip the investigator with the necessary background before conducting witness interviews.

The next step in the development of the investigation plan is to identify potential witnesses. Typically, the complainant is interviewed first, and the accused is interviewed last. In between, other identified witnesses with information relevant to the scope of the investigation should be interviewed.

An essential part of the planning process is determining where the investigation should occur. Should the investigatory interviews occur in person at the employer’s location? Should they be in person but at a remote location? Or is a remote investigation, conducted by videoconference, more appropriate? Numerous factors play into this decision, including the physical layout of the client’s facility; whether there is an appropriate onsite location to conduct interviews privately; and how disruptive the investigation will be to the employer’s operations.

Careful planning and preparation are critical to meaningful and efficient witness interviews.

During the interview, the investigator must maintain professionalism and objectivity. Confidentiality of the

investigation should be discussed with all witnesses, and all witnesses should be instructed that retaliation is prohibited and to whom suspected retaliation should be reported. Starting the interview with simple, informational questions name and position with the company, years worked, chain of command, etc. gives the witness a chance to relax, and it gives the investigator the opportunity to observe the witness’ demeanor in a relatively stress-free environment.

The substance of the complaint provides the basis for the questions asked of the complainant, and of the accused. When interviewing third party witnesses, the investigator should start with broad open-ended questions, such as, “Have you observed conduct in the workplace that makes you uncomfortable?” Successive questions become narrower based upon the information provided by the witness. Active listening tools, such as paraphrasing and summarizing the information shared by the witness, asking follow-up and clarifying questions, avoiding interruptions, and using supportive body language help to put the witness at ease in an inherently

stressful situation. Furthermore, the investigator must remain flexible; the information provided by the witness will often take the investigator down unexpected paths; relevant information may be discovered by pursuing these unanticipated avenues. At the end of each interview, the investigator should conclude with three important wrap-up questions: (1) Is there anything else I should know about this situation? (2) Is there anyone else I should talk to? (3) Are there any documents I should review? There are several options for documenting witness interviews. Some investigators choose to take notes as they conduct the investigation. Because it can be difficult to document the witnesses’ statements while remaining engaged in the interview, many investigators choose to record their interviews. Some investigators choose to prepare written statements of the interview and allow the witness to review and correct these statements. Another option is to have two investigators present for each witness interview, one of whom is primarily responsible for documenting the interview. Each of these options

has benefits and detriments that should be considered at the onset of the investigative process.

At the conclusion of the investigation, the investigator must analyze the evidence and evaluate the credibility of the information received. There are accepted resources that provide factors to consider in evaluating credibility; one example is the EEOC’s Enforcement Guidance on Vicarious Employer Liability for Unlawful Harassment by Supervisors. Key factors for assessing credibility include corroboration (the “gold standard” for credibility), opportunity and capacity to observe, past record of similar behavior, inherent plausibility, whether the witness had a motive to lie, and the witness’ demeanor. Note, however, that a practiced and well-versed liar’s demeanor may suggest more credibility than it deserves, while the demeanor of a nervous truthteller may suggest a lack of credibility. For these reasons, investigators should use demeanor very cautiously when analyzing credibility.

The final step in the investigative process is to prepare the investigative report. Every investigative report should include (1) pertinent background information such as the date of the complaint, the date the investigation was opened and when it was completed, the name of the investigator, and the names and dates of all persons interviewed; (2) the investigator’s factual findings; (3) an analysis of the evidence, including relevant credibility factors; and (4) the conclusion.

The report is the written work product of the investigation and the culmination of the investigative process. An effective investigation report should include clear and unequivocal findings, a statement of the evidentiary standard utilized (typically preponderance of the evidence), and alignment between the scope of the investigation and the findings. Should litigation ensue, not only the investigation report, but also the investigator’s file, will likely be discoverable.

When done well, workplace investigations can be useful tools to help companies manage difficult situations and minimize liability. Without the necessary planning and preparation, however, the results may be inconclusive and unhelpful. In the worst-case scenario, if the investigation proves to be lacking in independence, credibility, and thoroughness, it can increase the company’s liability when relied upon to make workplace decisions the exact opposite of the intended outcome.

Jan E. Hensel Dinsmore & Shohl, LLP

jan hensel@dinsmore com

By Kevin R. Kelleher

In June, the United States Supreme Court ruled that all employees are to be treated equally under Title VII. In Ames v. Ohio, the Supreme Court rejected the heightened standard the Sixth Circuit required of employees alleging reverse discrimination. Previously, the Sixth Circuit required members of the socalled majority groups to prove their employer was the unusual one that discriminated against them rather than minority groups. The Supreme Court found this requirement inconsistent with Title VII, which makes no distinction between majority and minority groups. Now, all claims for discrimination under Title VII are treated the same. As a result, all employers are expected to treat their employees equally, calling into question the legality of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (“DEI”) programs.

Discrimination Claims Under Title VII facie case for discrimination, a plaintiff must establish the following:

The McDonnell Douglas Burden Shifting Framework

Most claims for employment discrimination arise under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[1] Title VII prohibits employers from treating their employees differently on the basis of their “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”[2] Courts evaluate these claims based on the evidence the plaintiff submits to support their allegations. A plaintiff can present “direct evidence,” which “proves the fact of intentional discrimination without inference or presumption.”[3] However, these cases are rare.[4] Recognizing this, the Supreme Court established a burden shifting framework to allow plaintiffs to prove their case with indirect evidence.

Under a burden shifting framework, the plaintiff must first demonstrate a prima facie case of discrimination.[5] Then, the employer must establish a legitimate non-discriminatory reason for their conduct. Finally, the plaintiff must prove the employer’s articulated reason is a pretext for unlawful discrimination. To establish a prima

They are a member of a protected class; They are qualified for the position at issue; They were subject to an adverse employment action; and Circumstances giving rise to an inference of discrimination.

Where a plaintiff establishes a prima facie case, they create an “inference of discrimination” that the employer must rebut with a nondiscriminatory explanation for their conduct.[6] The employer’s failure to present evidence of a legitimate non-discriminatory reason leaves that inference unrebutted and creates a “mandatory presumption” of discrimination.[7]

The Sixth Circuit Distinguishes Claims for Discrimination and Reverse Discrimination

In 1985, the Sixth Circuit imposed a greater requirement on employees from majority groups (such as males or white employees) alleging discrimination.[8] In doing so, it reasoned “this nation’s history of discrimination” was “so

entrenched” that it permitted courts to infer discrimination against minority groups from actions that were “otherwise unexplained.”[9]

Accordingly, it imposed a greater burden on members of majority groups: to prove a prima facie case for reverse discrimination, a plaintiff had to establish “background circumstances [to] support the suspicion that the defendant is that unusual employer who discriminates against the majority.”[10]

Plaintiff-Appellant Marlean Ames worked for the Ohio Department of Youth Services (“ODYS”) as a program administrator. In 2019, Ames, a heterosexual woman, applied for a promotion to a management-level position. ODYS rejected her application and selected another candidate, a member of the LGBTQ community. Then, ODYS demoted Ames and replaced her with another employee who was also a member of the LGBT community.[11]

Because her orientation placed her in the majority group, the district court required Ames to establish background circumstances “sufficient to demonstrate that [ODYS] discriminated against a majority group.”[12] When she failed to do so, the court dismissed her claims for discrimination on summary judgment.[13] On appeal, the Sixth Circuit affirmed, finding Ames did not make “the necessary showing of ‘background circumstances.’”[14]

The Supreme Court’s Holding

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed the Sixth Circuit’s decision. It found the “additional ‘background circumstances’ requirement” to be inconsistent “with Title VII’s text” and its own “case law construing the statute.”[15] The plain language of Title VII’s anti-discrimination provision prohibits employers from discriminating against “any individual with respect to [their] compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”[16] “Congress left no room for courts to impose special requirements on majority-group plaintiffs alone.”[17]

To the contrary, the Supreme Court made clear: Title VII prohibited racial discrimination against white employees “upon the same standards as would be applicable were they [minorities].”[18]

The Sixth Circuit’s “‘background circumstances’ rule flout[ed] that basic principle.”[19]

Many employers believe fostering a diverse and inclusive workplace is an important part of a functioning business. Following Ames, employers need to rethink how they achieve this. Hiring and promotion policies that tend to favor one group over another have always been illegal. However, under Ames, the very policies that may have protected employers from claims of discrimination may now be used against them. Employers should scrutinize their policies and procedures to ensure employees are not disproportionately losing opportunities. If necessary, employers should consult with attorneys to ensure their policies comply with the law.

The Supreme Court has made clear: Title VII does not distinguish between minority and majority groups.

Employers cannot favor one group over the other. They must now work carefully to ensure they treat all their employees equally.

1 Ohio also prohibits discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex, military status, national origin, disability, age, or ancestry ” R C 4112 02(A) Ohio courts generally follow federal law in applying this statute. See, e.g., Plumber & Steamfitters Joint Apprenticeship Commt. v. Ohio Civil Rights Comm., 66 Ohio St.2d 192, 196 (1981).

2 42 U S C 2000e-2(a)

3 (Cleaned up ) Portis v First Natl Bank of New Albany, 34 F 3d 325, 328-29 (5th Cir 1994)

4 Kline v Tenn Valley Auth , 128 F 3d 337, 348 (6th Cir 1997) (“Rarely can discriminatory intent be ascertained through direct evidence because rarely is such evidence available.”).

5 McDonnell Douglas Corp v Green, 411 U S 792, 802 (1973)

6 St Mary’s Honor Ctr v Hicks, 509 U S 502, 528 (1993)

7 Id

8 See Murray v Thistledown Racing Club, Inc , 770 F 2d 63 (6th Cir 1985)

9. Id. at 67.

10. Id., citing Parker v. Baltimore & Ohio RR. Co., 652 F.2d 1012, 1017 (D C Cir 1981)

11 See Ames v Ohio Dept of Youth Servs (Ames II), 87 F 4th 822, 824 (6th Cir 2023)

12 Ames v Ohio Dept of Youth Servs (Ames I), 2023 U S Dist LEXIS 44979, *23 (S.D. Ohio Mar. 16, 2023).

13. Id. at 35.

14 Ames II at 825

15 Ames v Ohio Dept of Youth Servs (Ames III), U S , 145 S Ct 1540, 1544 (2025)

16 Id at 1546, citing 42 U S C 2000e-2(a)(1)

17 Id

18. (Emphasis in original.) Id., citing McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273, 280 (1976).

19 Id

With contentious political and social issues dominating public discourse — and the reach of social media amplifying individual voices employers are increasingly challenged by employee political expression both on and off the job. From protest attendance and yard signs to social media posts and political apparel, employees are engaging in a variety of ways. This article outlines key legal considerations and practical strategies for managing employee political activity in both the public and private sectors in Ohio.

By Laura Repasky

Public employees in Ohio are governed by a unique combination of federal constitutional protections and statespecific statutory limits. Notably, R.C. 124.57 prohibits classified employees from participating in certain partisan political activities, including:

Campaigning for candidates for partisan elective office;

Soliciting political donations; and Holding office in a partisan political organization.

These prohibitions apply at all times, not just during work hours, and may restrict off-duty conduct that would otherwise be protected for private citizens or, under certain circumstances, unclassified employees.

However, classified public employees may engage in the following off-duty political activities:

Voting and expressing opinions (orally or in writing);

Attending political rallies; Donating to candidates or causes; Circulating or signing nonpartisan petitions; Displaying signs or stickers on personal property; and Wearing political buttons or badges.[1]

Where R.C. 124.57 does not apply, public employers must analyze employee speech under the First Amendment. The courts apply a threestep test:

Public Concern: The speech must address a matter of political, social, or general community concern. (See Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011)).

Official Duties: Under Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006), speech made as part of official job duties is not protected.

Balancing Test: Using the Pickering-Connick standard, courts weigh the employee’s right to speak

against the employer’s interest in maintaining efficient and disruptionfree operations. (See Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968), and Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138 (1983)).

When evaluating employee political activity, public employers should consider:

Whether the speech occurred offduty;

Whether it involved illegal conduct (e.g., trespassing, violence, etc.);

Whether the employee was publicly identifiable (e.g., in uniform, listed work title on social media, etc.);

Whether public resources were used (e.g., email, time, materials, etc.); and

Whether the employee holds a sensitive position (e.g., law enforcement or public safety).

Employers must apply rules consistently and base any disciplinary action on conduct and its potential

consequences — not merely on the content of speech to avoid constitutional claims.

Unlike their public-sector counterparts, private employers are not bound by the First Amendment. In general, they have wide discretion to discipline or terminate employees for off-duty political expression. However, employers should proceed carefully, as several legal doctrines may still come into play.

NLRA

: The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) protects employee speech that constitutes concerted activity, particularly when addressing wages, hours, or other working conditions even when the speech is politically framed.

Anti-Discrimination Laws: If employee speech relates to race, religion, gender, or other protected

characteristics, adverse action may trigger liability under Title VII or the Ohio Civil Rights Act.

State Law Protections: While Ohio does not protect private employees from discipline for political activity, several other states do.

Multistate employers should check for applicable protections before acting.

Even where legal, taking disciplinary action for political speech can expose employers to reputational harm, workplace morale issues, and potential litigation.

To proactively manage political speech and avoid legal or practical pitfalls, employers should adopt the following best practices:

Policy Development

Draft content-neutral workplace policies on:

Political expression and decorum;

Social media usage;

Use of employer time and resources;

Workplace attire, insignia, and solicitation; and

Respectful communication and anti-harassment.

Public employers should ensure policies are narrowly tailored, advance a legitimate governmental interest, and allow alternative avenues of expression. Private employers should ensure policies do not run afoul of the NLRA.

Train supervisors to respond neutrally to political discussions; Training and Communication

Educate employees on the distinction between legal protections and workplace rules; and

Reinforce consistent enforcement of policies across political viewpoints.

If forewarned of planned demonstrations or walkouts, prepare contingency plans and communicate expectations, Advance Planning

Consult legal counsel when necessary to assess legal exposure.

When political expression becomes a workplace issue, employers should follow a structured approach: including possible disciplinary consequences; and

Determine if the conduct violated any workplace policy (e.g., attendance, conduct, misuse of time/resources).

For public employers, verify whether the employee is classified and whether R.C. 124.57 applies. Consider whether the speech was made in the course of official duties.

Did the speech cause disruption, reputational harm, or internal conflict? If not, discipline may be unwarranted.

Determine whether the conduct

Discipline must be based on conduct (e.g., harassment, insubordination), not the viewpoint expressed.

Link the action to specific policy violations and workplace impacts. Avoid editorializing.

For public employers and unionized workplaces, ensure disciplinary procedures align with collective bargaining agreements and statutory requirements.

After resolution, provide training to reinforce expectations and avoid future incidents.

In an era of heightened political engagement and digital expression, employers must balance operational needs, legal compliance, and employee rights. For Ohio labor and employment lawyers, advising clients in both the public and private sectors requires a may qualify as protected concerted activity under federal labor law.

careful understanding of constitutional law, labor protections, and the potential legal risks associated with addressing political speech. With clear policies, consistent enforcement, and thoughtful planning, employers can navigate these complex issues while minimizing liability and maintaining workplace harmony.

[1] A complete list is available at Adm.Code 123:1-46-02. Unclassified public employees may also engage in the enumerated off-duty political activities

Laura Repasky Franklin County Human Resources Director laura.repasky@franklincountyohio.gov

When then-U.S. President Barack Obama quipped to Congressional Republicans in 2009 that “elections have consequences,” he was underscoring a simple truth one that has been placed in sharp relief following the 2024 general election. Since the Trump Administration assumed the reins of power in Washington, D.C., on January 20, 2025, sweeping changes in personnel, policies, and priorities have occurred, including a marked shift in the political

By Scott DeHart

landscape related to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (“DEI”).

DEI broadly describes workplace policies and practices aimed at creating a culture that respects and values differences in race, gender, age, ethnicity, disability, religion, and other characteristics. “Diversity” focuses on representation, “equity” emphasizes fair access and treatment, and “inclusion” refers to fostering a culture

where all individuals feel welcomed, respected, and valued. Over the past two decades, DEI became prominent in corporate America and across the public sector. Critics argued that DEI policies (particularly those involving hiring goals, quotas, or targeted promotions) undermined meritocracy in the workplace and sometimes disadvantaged majority group employees. And as DEI gained traction, other longstanding practices designed to promote “affirmative action” notably, race-conscious admissions at institutions of higher education came under increased scrutiny. A turning point came in June 2023, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down raceconscious admissions policies in higher education in its landmark decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. 181 (2023).

The rollback of DEI programming at the federal level was a major pledge during Donald Trump’s bid to reclaim the White House. And upon taking office on January 20, 2025, President Trump wasted no time in delivering on his campaign promise. On the eve of his

swearing-in, President Trump signed Executive Order 14151 (“Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing”) directing all federal agencies to terminate DEI mandates, eliminate DEI positions, and purge DEI content from their websites and publications. The following day, President Trump signed Executive Order 14173 (“Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit‑Based Opportunity”), which rescinded the landmark Executive Order 11246 (and its related amendments), effectively ending affirmative-action obligations for federal contractors regarding race and gender. That Order clipped the wings of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (“OFCCP”), an agency within the U.S. Department of Labor that has served for decades as a federal DEI watchdog. President Trump flipped the script for federal contractors, whose longstanding affirmative action obligations were replaced by new clauses requiring contractors to certify that they do not operate unlawful DEI programs (and opening the door to civil liability under the False Claims Act for noncompliance).

Key federal civil rights agencies followed suit, performing an ‘aboutface’ in their guidance and enforcement priorities with respect to DEI programs. In March 2025, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) and U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) issued new technical assistance documents addressing DEIrelated discrimination. The first document, issued jointly by the DOJ and EEOC and titled, “What to Do If You Experience Discrimination Related to DEI at Work, ” provides examples of DEI-related discrimination and outlines the process for filing charges with the EEOC related to DEI initiatives.[1] The second document, issued by the EEOC and titled, “What You Should Know About DEI-Related Discrimination at Work,” provides a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between Title VII’s protections and DEI.[2] The EEOC guidance takes issue with employee resource groups (ERGs) and affinity groups, as well as other common DEI initiatives that have resulted in disparities in employment opportunities, compensation, access to training and mentoring, and other terms or conditions of employment.

Then, on the heels of President Trump’s executive actions, the U.S. Supreme Court removed a significant legal hurdle for so-called “reverse discrimination” claims by ruling unanimously that members of majority groups (e.g., white, heterosexual, male) do not have to meet a heightened “background circumstances” burden to pursue Title VII discrimination claims. Ames v. Ohio Department of Youth Services, 145 S.Ct. 1540 (2025). In the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Ames, EEOC Acting Chair Andrea Lucas affirmed the agency’s commitment “to dismantling identity politics that have plagued our employment civil rights laws, by dispelling the notion that only the ‘right sort of’ plaintiff is protected by Title VII” and underscored that employers will not be shielded from “any race or sex discrimination that may arise from those employers’ DEI initiatives.”[3]