LEVELING THE LEARNING CURVE

The new connected university is being invented as we write at colleges and universities around the world. It is based on the belief that active learning and peer-to-peer engagement must play a central role in learning and that technology can enable these practices. It is also based on the idea that learning does not happen only during course meetings but through a continuum of activities ideally driven by students themselves. Finally, it is based on the understanding that a great deal of learning happens when students are connected to people from diverse backgrounds and are engaged with real-life issues and problems.

By integrating digital tools such as active discussion boards, prerecorded video lectures, video cases, collaborative projects, Zoom, and live chats into core teaching and learning offerings, higher education finally joined the twenty-first century. Robert Ubell (2021) states: “We are all online learners now. Every day that we use Google for research, send an email, or use Zoom, we use the tools of digital education.”

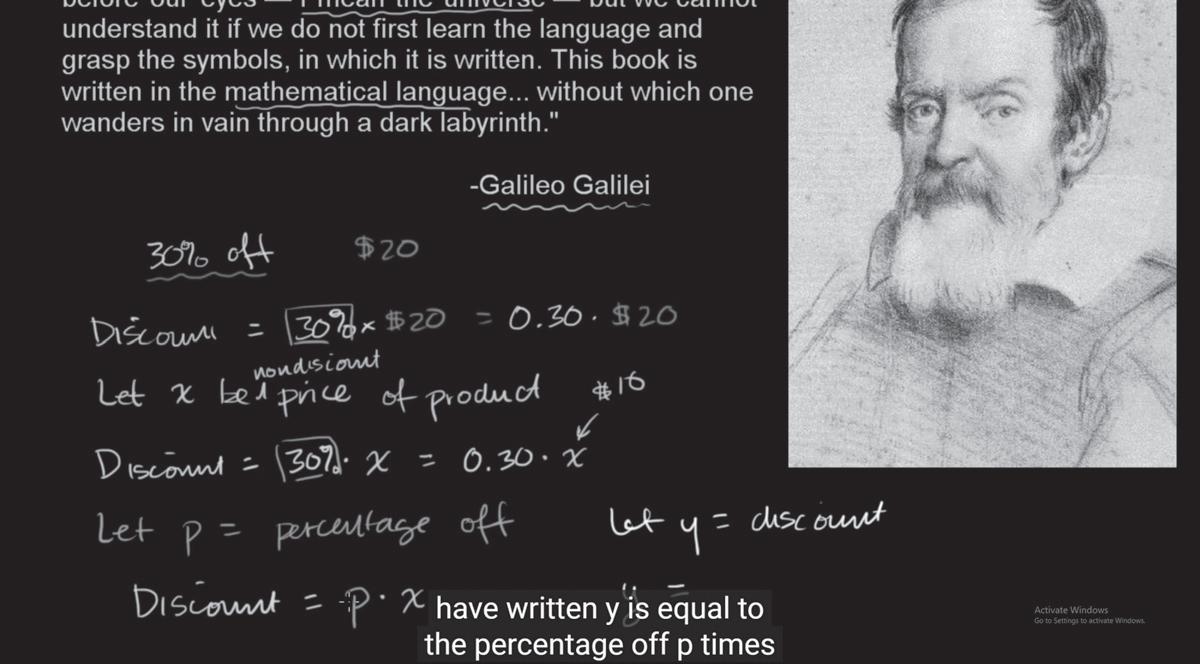

The amazing amount of information available online has made us all “active learners.” Today’s incoming first-year college students have studied in a K–12 environment in which teachers used Google Classroom, Blackboard, or Canvas to create active learning environments. Today’s students understand “googling it.” They grew up learning how to find YouTube videos from educational digital content providers such as Crash Course or the Khan Academy, which explain how to solve basic science and math problems (figure 3.1), and then they applied these lessons to specific assignments.

In high school social studies, it’s likely that teachers assign TED Talk videos, or clips from PBS shows such as Nova, Nature, and Frontline that PBS Learning Media makes available for easy downloading, along with teachers’ notes and discussion subjects (figure 3.2).

In many high school classes, students complete project-based activities, applying academic concepts to real-world problems. This approach improves learning outcomes and makes learning relevant (Linder 2017). Why should this active learning end when students enter college? Deep reading of literature and academic works should remain a key part of the college experience, but

readings should be complemented with the tools of twenty-firstcentury life and modern pedagogical practices. Techniques such as active learning, peer-to-peer engagement, and project-based teaching have been proven to improve student outcomes. Digital tools can help make them central to all classrooms. Finding the right balance between these different activities and modalities is the defining challenge of the twenty-first-century connected university.

The concept of active learning gained special prominence in the 1960s. It developed from constructivist learning ideas first advanced by theorists such as Jean Piaget (1896–1980), Lev Vygotsky (1896–1930), John Dewey (1859–1952), and others (Bain 2021; Reich 2020; Ubell 2021). Active learning was founded on the belief that people learn by doing, constructing their own knowledge by connecting it to their prior understanding and life experiences.

Digital tools can enhance active learning. Rather than only following lectures, students actively construct their own understanding of an issue. In Super Courses: The Future of Teaching and Learning, Ken Bain (2021) explores groundbreaking courses across a range of universities. One example of digital tools facilitating active learning can be found in physics courses at Harvard. In the 1990s, Eric Mazur gave his students videos and materials to read before class, and then used class time exploring “rich and inherently fascinating problems,” which he called the ConcepTest. Other examples include research and project-based design courses at the Rhode Island School of Design, and a history course built on role-playing and simulations at Northwestern University (Bain 2021).

Active learning is the common denominator in all of these courses. Students work with peers and construct their knowledge through active research projects. Active learning can happen in both in-person and online settings, and digital tools and blended delivery can make the active learning process seamless. This is often surprising because the idea that digital tools enable active learning seems counterintuitive. Prerecorded content seems passive.

Poorly planned online courses fall into this trap. But the best online courses and digital content create active, multifaceted learning experiences. By watching prerecorded video lectures or digital case studies, students can come to class ready for discussion and debate. By allowing learning to be a flow of activities—rather than the read/lecture/test cycle typical of traditional instruction— students can become actively involved in the concepts and analysis of their subjects and learn by doing.

2U’s Luyen Chou’s (2021) interest in online learning began when he realized that he had learned little from the traditional lecturebased courses he took as a student. As a young high school teacher, he decided to create a digital archeology site for his class. In this virtual environment, students could find digital artifacts, conduct their own research, and work in teams to construct their own understanding of the issues. “They were doing what I had fallen in love with, which was true scholarship. . . . I looked at this and said, ‘That’s what I want to be doing.’ ” It was classic “active” learning

concepts put into practice, and Chou realized that “digital technology allowed us to unlock that in a way that was much more robust than we could ever have done before.”

In this paradigm shift, the instructor’s role moves from “sage on a stage” to “guide by their side.” At Columbia, Stanford, Arizona State University, and Georgia Tech, active learning drove course redesigns. For Stanford’s Matthew Rascoff (2021), the key was to match the active learning strategy to the discipline, and physicists led the change. “Physics education, in most institutions now, is active, not passive,” Rascoff said. “It’s not lecture-driven anymore.” This change was driven by the example of the physics innovators Eric Mazur of Harvard and Carl Weiman of Stanford, who realized that students could best understand certain key concepts through personal experience and peer-to-peer learning. “They led to a transformation of physics education,” said Rascoff. Other fields soon followed their lead. The move online became a fantastic opportunity to rethink course design, turning a passive lecture-based learning experience into one that is built on the active construction of knowledge. “I think people within the discipline need to figure out the active learning strategy that is appropriate to their field. It’s going to look different in a writing class than in a physics class,” explained Rascoff.

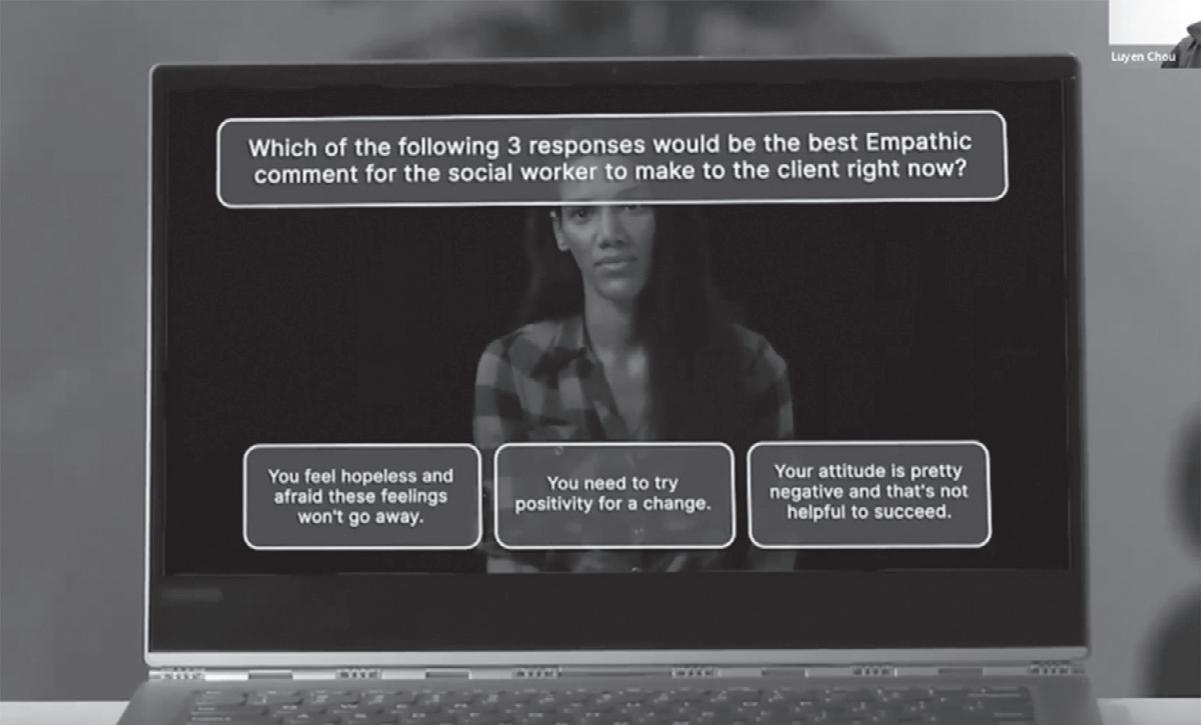

Digital tools enable active learning activities that would pose logistical barriers or cost too much to run in traditional classrooms. These tools include digital labs and demonstrations, digital case studies, and simulations in subjects as varied as social work, engineering, and crisis negotiation. At Arizona State University, business management classes often include video scenarios based on common situations (Jhaj 2021; figure 3.3). At Purdue, students use 360-degree walkthroughs of boiler rooms and other heating plants, allowing them to virtually enter these spaces and interact with layouts and equipment (figure 3.4). At Columbia and the Open Society University Network, digital case studies present students with realworld problems in all their messy complexity.

At 2U, the instructional design team of a social work course filmed simulated clinical situations involving social workers and

their clients (figure 3.5). “We have actors and actresses who play the parts of patient, clients, and practitioners, and the students actually interact with them online,” explained Luyen Chou (2021). The simulations and experiences are built into active learning experiences. Students interact with the digital activity or content, then build their own understanding of the issues.

Peer-to-peer learning is another core element of the new connected university that digital tools can support and enhance. Social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter are part of the daily routine of twenty-first-century digital natives. These platforms are built on user-generated content, which can foster peer-to-peer communication and sharing. Well-designed “digitally enhanced” courses—be they fully online, blended, or in person— also use these same concepts and techniques.

In networked courses at Columbia University, and with our partners at the Open Society University Network (OSUN), the most exciting moments come when students engage with each other. In live discussion or asynchronous debate, students share insights and feedback from their readings, video lectures, classroom meetings, professor conferences, and joint project conferences. The more students share with their peers, the more they are invested in their own learning. Being seen and heard is primal.

In OSUN collaborative courses, students from campuses around the world—in places such as Bangladesh, Kyrgystan, Russia, Germany, and the United States—meet online. Here peer-to-peer learning and collaboration are key. In countries that are transitioning to democracy or fighting growing authoritarianism, the OSUN courses focus on critical thinking and the exchange of ideas across cultural boundaries. “At its heart, liberal arts and sciences education is about the education of engaged citizens,” explained OSUN Vice Chancellor Jonathan Becker (2021). “It is the antidote to rote learning if done properly.” Digital tools such as video case studies, online discussion boards, and real-time brainstorming using tools like Padlet allow international project teams to connect and collaborate. “The assignments are meant to have students dialogue with each other,” explained Becker, “because a view of citizenship . . . is radically different in Palestine than it is in the United States, and [than] it is in Russia.” Despite the students’ different life circumstances, online tools let them connect in ways impossible to imagine even ten or twenty years ago. “My view is that eighteen-year-olds, wherever they are from, tend to find much more in common than they do different,” Becker said. “And that very fact of commonality gives a sense of normalcy that even people in incredibly difficult circumstances find comforting.”

For eCornell’s Paul Krause (2021), peer engagement can be more instructionally valuable than the production quality of prerecorded content. “We create a lot of highly produced videos with animations,” Krause said. “The reality is students are more likely to remember how they engaged with other students, the projects they were able to apply, and the feedback from their instructor.” These factors lead to high-impact courses that can “change the trajectory of someone’s career.”

Peer review sparks an exciting chain of activities: a virtuous cycle of student involvement and action that can drive learning in new directions. For Wiley’s Bill Cochran (2021), peer engagement is the key to successful digital course design. “How are we weaving in those interactive touch points?” Cochran asked. “How are we creating opportunities for students to learn from each other?”

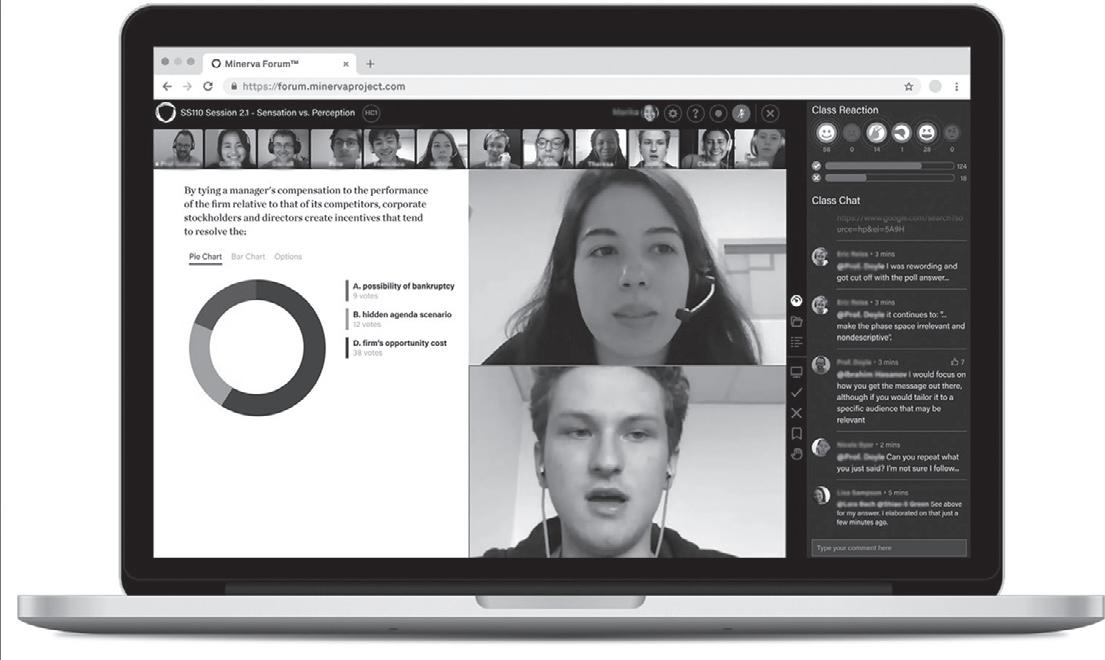

New educational conferencing platforms such as the Minerva Project’s Forum and the new educational webinar tool Engageli make a strong argument that certain forms of peer-to-peer interaction can often be even better online than in person. Minerva University, a San Francisco-based educational startup founded in 2012, is dedicated to radically reimagining education around active and peer-to-peer learning concepts. It has no formal campuses or classrooms but runs student dorms in San Francisco, Buenos Aires, Hyderabad, Seoul, Berlin, London, and Taipei. All classes meet 100 percent online in digital seminars run on its proprietary Forum platform. Minerva founder Ben Nelson (2021) believes that the core role of all educational institutions is social learning. “It involves a group of individuals who are peers, who explore the black and the gray, not the black and the white . . . what is certainly true, and what could potentially be true . . . that is the core reason for being for a university,” Nelson explained. “That entails active learning.”

For the one thousand students in Minerva University’s global cohorts, this active peer-to-peer learning happens on the Forum platform. “This is a technology that was built upon . . . decades of research into learning science about active, engaged, peer-based classroom environments,” explained Minerva Project’s Sharan Singh (2021). It allows professors to track participation by color coding each student’s video feed based on how much the student has talked during the session, allowing the professor to know whom they need to call on (figure 3.6). Other tools for real-time polling and chat enable what many would argue is a richer experience online than can be found in a “normal” in-person classroom.

Engageli, another Zoom alternative, also promises richer real-time social interactions than traditional classes. Launched during the pandemic, Engageli was co-created by Dan Avida and Coursera cofounder Daphne Koller when their daughters found themselves in “Zoom School” in April 2020. Avida and Koller searched for alternatives. Avida (2021) remembers, “Much to our surprise, when we dug around, Zoom was the best game in town. To rephrase, it wasn’t the best game in town; there was no real good game in town . . . so we set out to develop a platform that was built from the ground up for instruction.”

Although the Engageli platform began as a Zoom-like interface for video-conference-style classrooms, it soon moved into something that also offered tools for both asynchronous learning and live in-person classrooms (figure 3.7). Its real-time chat, document sharing, and polling features enable smooth transitions from general group discussion to smaller “breakout” rooms and back, and they can also be used to enhance and optimize in-person activities. Students in large classes can organize into smaller groups to meet online and synchronously “watch” a previously recorded lecture together, make notes, stop playback, and interact with the material in real-time in ways that are similar to the experience of a group video game (Avida and Spivak 2021).

The social aspects of online tools suggest the need to keep them in mind as classes return to campus. “A well-designed online course . . . helps you

like you are part of a learning community,” said Mathew Rascoff (2021) of Stanford University. Online tools and communities nurture learning “that is accountable, that is social, that is mind-expanding for our students.” It is here that “transformative learning happens. . . . It’s all about the interactivity among human beings that’s enabled by technology.”

feelFigure 3.6 The Minerva Forum platform

“An impressive cross-sector review of the successes and failures from across the digital higher education landscape. A must-read for university presidents, provosts, and deans looking to chart their institutions’ digital futures.”

— ANANT AGARWAL, FOUNDING CEO OF EDX“A crucial book at a crucial time. Education is key to development and our planet’s long-term survival. This book asks whether top universities are willing to accept the challenge of playing a major role in this.”

— JUDITH RODIN, FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION AND THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA“The pandemic let the EdTech genie of the bottle and it’s not going back. It’s clear that online tools and hybrid learning will play a key role in the future of higher education. This carefully researched book provides an important road map for what this future might look like.”

— VIKAS POTA, FOUNDER AND CEO, T4 EDUCATION“An important book for anyone who cares about the future of higher education in an interconnected world. Addresses both the key challenges and opportunities that post-COVID educational leaders face and the lessons that the pandemic period offers for the future.”

— JONATHAN BECKER, VICE CHANCELLOR, OPEN SOCIETY UNIVERSITY NETWORK“Industry after industry has been transformed by digital tools. This smart and practical book argues that now is the time for universities to finally embrace their digital futures and shows how.”

— NAJAT VALLAUD-BELKACEM, FORMER FRENCH MINISTER OF NATIONAL EDUCATION, HIGHER EDUCATION, AND RESEARCH