ILLNESS AND MEDICAL CARE

IN PUERTO RICO

U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT

PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

WASHINGTON, D. C.

U.

U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT

PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

WASHINGTON, D. C.

U.

By

JOSEPH W. MOUNTIN, Surgeon

ELLIOTT H. PENNELL, Associate Statistician

EVELYN FLOOR, Assistant Statistical Clerk

PREPARED BY DIRECTION OF THE SURGEON GENERAL

recinto PIEDRAS

No SE PRESTA FUERA DE LA SALA-»

For many years the municipalities of Puerto Rico have operated a system of public assistance which combines medical care and certain additional elements of relief. The system carries the official designa tion "Beneficencia Municipal." A few of the municipalities contain ing large cities erected hospitals at an early date. Provisions for public medical service in other parts of the island seldom, until recent years, included much more than care of the type that might be ren dered by a physician in his office or in the home of a patient. In addition, small sums of money may have been set aside in the budget of municipalities for the payment of hospital bills.

Shortly after the American occupation of the island there began a movement for the construction of local hospitals that finally extended to the smaller municipalities, many of which are essentially rural and extremely low in taxable resources. For reasons that svill be con sidered later the municipal system of medical care, especially in the second- and third-class municipalities, failed to develop in keeping with the standards of service desired by the medical profession and the civic leaders of the island.

Late in the fall of 1934 the Governor of Puerto Rico transmitted to the Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service a request for the assignment of personnel who would direct an inquiiy into the character of the local medical service and be responsible for preparing a report based on the findings. Actual field work was started during February 1935 and consumed a period of slightly more than 3 months.

Two of the authors (Mountin and Pennell) were in charge of the study from the initial planning through the preparation of the report. This extensive bod^'^ of data could not have been gathered, however, except for the assistance obtained on the island. The insular health department arranged the necessary entree. Health officers, public health nurses, and sanitary inspectors, normally attached to local health units, and numbering about 60 in all, were temporarily relieved from their regular duties and assigned to the field canvass. Municipal authorities most graciously placed their records at the disposal of the study staff and other agencies supported the field work in the same generous manner. Schedules were edited and coded in San Juan by the regular clerical force of the insular health department. Comple-

tion of the clerical work and the final analysis of the data were accomphshed.in Washington by the United States Public Health Service.

Pubhshed morbidity and mortahty data were used insofar as possible, but additional information was required to supplement the picture. PEspecially was this true regarding illnesses wliich did not enter the jvital statistics records of the insular health department and those C which may not have come to the attention of physicians.

In order to obtain an expression of the amoimt of illness in the general population, and especially the circumstances under which the illness occurred, it was necessary to study a sample of the population.

A total of 5,891 families, representing 31,756 individuals, were in cluded in the group used for this study. The family schedule used in the survey made provision for a description of the members and the premises, together with detailed data regarding illness, the amount and character of medical attention, and contact with public health agencies.

The director of beneficencia, or some other responsible person in each municipality, completed another schedule of information which was used in describing the facilities for medical care available in the municipality, and the services rendered through these facilities. These items were related to figures on receipts and expenditures obtained from the auditor for the insular government. More than half the municipalities were visited by one of the authors (Mountin) for the purpose of inspecting hospitals, clinics, and other facilities maintained for the care of the sick.

A more detailed description of each element of the study, together with the findings, will be presented in appropriate sections of the report. Before these data are shown, however, certain salient facts of a general character regarding the island and its people will he given to oiient the reader. Without this information, it would be impossible for any one but a technically trained person intimately acquainted with local conditions to appreciate either the influence that social and economic factors exert on the health and lives of the people, or the types of public services which would be adapted to the local needs.

The population of Puerto Rico has increased steadily since 1765, the first year for which records were available. This may be noted in table 1. During the last intercensual period the increase amounted to nearly a quarter of a million. In 1930 the total population was 1,5^,^3. The gross area of Puerto Rico, including the adjacent islands, is 3,435 square miles. Thus the average number of inhabitants per square mile is about 450. Appendix A shows the distribution of population and the area by municipalities. The problems usually created by excess population are further intensified in Puerto Rico by the fact that 72 percent of the population was classed as rural in 1930. San Juan, the largest city, contained 114,715 inhabitants. Mayaguez and Ponce, combined, contained 90,490 inhabitants. The remainder, or about 50 percent of the total urban population, resided in 37 towns which ranged in size from 2,500 to 25,000 inhabitants.

Table 1.—Population of Puerto Rico at different census periods from 1765 to 1930'

Practically all the inliabitants of Puerto Rico are native to the island, less than 1 percent being foreign born. According to the census of 1930, about 75 percent of the inhabitants were white and about 25 percent Negroes. Other races comprised less than 1 percent of the total population. There was considerable difference in the racial composition of the municipalities, the proportion of Negro population ranging from less than 10 percent in 12 municipalities to more than 50 percent in 5 municipalities. Generally speaking, the

1 Population figuresfor Puerto Rico and for the continental United States,when used for U.S.censual years, are quoted from U. S. Census reports. When population figures are required for intercensual years, esti mate are based upon published census figures. Birth and death statistics for the continental United States are taken from annual reports of the U. S. Census Bureau and are limited to the registration area, while those for Puerto Rico are from annual reports of the commissioner of health.

(3)

Negro population was relatively greater in the large cities and in those coastal municipahties where sugar cane is cultivated intensively. Economic and social distinctions between races are not clear cut. Mention has already been made of the growth in population, especially since the American occupation in 1898. The birth rate is now more than t%vice that of the continental United States, as may be observed in table 2. Another point to be noted in this table is the upward trend in the birth rate of Puerto Rico, contrasted with the falling rate for the continental United States. The actual increase in the population of Puerto Rico is not so rapid as the lugh birth rate would suggest since it is further illustrated in table 2 that death rates are also high. Nevertheless, when the rates of natural increase are compared for the two areas, it is evident that the net change in Puerto Rican population is considerably greater than in that of the continental United States.

Table 2.—Average rates of birth, death, and natural increase of the population in Puerto Rico and the continental United States during tivo 5-year periods, 1925-34

of young persons. This fact is strikingly illustrated by comparisons made between the age composition of the population in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States. Distributions by selected age groups of the inhabitants of the two areas are shown in table 3. According to these figures about 42 percent of the population in Puerto Rico is below 15 years of age, whereas in the continental United States the percentage is about 29. In the group above 45 years, the percentage for Puerto Rico is 13 and for the continental United States 23.

Table 3.—Age distribution of the popidation in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States for 1930

The average number of persons per family for the island as a whole, according to the census of 1930, was 5.3. while in the continental United States it was 3.8. In the 9 Puerto Rican cities having popu lations over 10,000, the average size of the family was 4.7. In the canvass of 5,891 families,^ the average size of the rural family is found to be 5.8, and of the families in towns of all types it is 4.9. The median size for rural families is 5.3 and for the town families, 4.4. Thus the rural families tend to be larger than those living in the urban comjumnities. The size of family should be kept in mind since its bearing on health becomes more apparent when the resources of the family are considered.

In the census of 1930 approximately 50 percent of those who normally follow gainful occupations gave agriculture as their usual source of employment; 20 percent, manufacturing; 10 percent, domestic and personal service; and the others were distributed among the trades, professions, and clerical occupations. Manufacturing is confined for the most part to needlework and the processing of four principal crops: sugar, tobaecoy-coffee, and fruit. Practically the entire tillable area of the island is devoted to the intensive cultivation of these four crops. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate certain phases in - the production of sugar. Generally speaking, the inhabitants of \ Puerto Rico are very poor, especially when compared with those of the (continental United States. In this study, data on income for the year 1934 were obtained from a representative sample of nearly 6,000 famihes. The median, or middle, family income of this group was $100 per annum and the average income was estimated to be about $230. Ninety percent of the Puerto Rican families included in the survey reported incomes of less than $500, while only 4 percent earned $1,000 or more. The average and median incomes for the families of the continental United States in 1929 were $2,800 and $1,700 according to Leven, Moulton, and Warburton (1). Only 7 percent of these continental families reported annual incomes of less than $500, whereas 79 percent had incomes of $1,000 or more. Some of this variance might be attributed to the difference in economic conditions of the 2 years, since the survey period in Puerto Rico corresponded with the trough of a depression, while the study made in the continental United States occurred when prosperity was at its height. Notwithstanding the possible effect of difference in time, the picture is perhaps only slightly distorted, since the Brookings Insti-

'The families in surveyed cities and towns, regardless at size, and in bidlt-up areas directly adjacent to those cities and towns are classified as urban. All other surveyed families are classified as niral.

1:17904—37 2

tution (2) reported that even in 1929 the Puerto Rican wage scale for laborers, who constitute a great majority of the earning class, was only slightly higher than that found during the survey. The difference between the income of the two areas is clearly reflected in their standards of hving.

It must be borne in mind that on the island even a small reduction in cash income constitutes a high percentage loss which may transpose a family from general poverty to the state of experiencing actual want. This situation, created by the economic depression, has been con siderably relieved by Federal aid, administered by the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration. The extent of this aid will he considered later in the report.

The income of Puerto Rican families varies considerably. In the survey made of 2,597 town and 3,294 rural families it was found that the median, or middle, annual income of the rural families was less than two-thirds that of the town group, the figures being $88 and $137, respectively. In the section on illness, consideration will be given to the possible significance of higher illness rates in relation to adverse economic conditions, also to the effect of income on the amount and character of medical care received.

*• The general subject of diet was investigated on a previous occasion by Eliot (3) but the findings which are briefly summarized portray conditions which have not changed materially. Eliot states, "The daily diet for the average family can be summarized as rice and beans twice a day—usually in large amounts, especially of rice; coffee twice or three times a day, with unrefined sugar and with or without a small amount of milk; bread in very small quantities, usually without butter; tuberous vegetables; and fruit in small quantities, the fruit chiefly for the cliildren. Some families had nothing but rice and beans, and a few were found that did not even have both rice and beans every day."

The families studied by Eliot were drawn predominantly from the cities and ontlying territory; consequently they might not be truly representative of the island since they had access to whatever variety in diet their income could afford. The rural dwellers raise very little to supplement that which they purchase in the neighborhood store where the stock is limited. In fact, the diet in rural districts, if observed, may have been found even more monotonous and inade quate, since different studies conducted in more prosperous times showed that the amount of money available to meet all needs varied from 9 to 12 cents per person per day in different sections of the island.

5,—Anotlier type of rural home built of thatch and bark.

The findings of Mitchell (4) -wdth regard to diet in the sample of families studied by him and coworkers accorded with those quoted from Eliot.

This dietarj*^ which is insufficient in amount, and particularly defi cient in animal proteid, results in a state of nutrition which is below that considered normal in the continental United States. Inadequate \ diet is likely to be an important factor in producing anemias of various 1types and deficiency diseases such as nutritional edema, sprue, and other related conditions which abound in Puerto Rico. Rickets, however, is not prevalent on the island.

According to the data secured in the family survey, lumber is used as construction material for nearly 90 percent of the town houses and about 60 percent of those in rural areas. Of the remaining city homes, the better ones are made of stucco and the poorer ones of discarded building materials of various types. In the rural sections discarded materials are used for many domiciles and thatch is also a frequent choice. Figure 3 illustrates a group of typical urban homes, while those shown in figures 4 and 5 are representative of the dwellings in rural areas. The building law requires that the houses be elevated above the surface of the ground or that some equally effective ratproofing measure be used. Elevation is the method chosen by the poorer families. All Puerto Rican homes have floors. Screening is not practiced to any appreciable extent on the island; thus the houses afford scarcely any protection against flies and mosquitoes. Bed nets, however, are in fairly common use.

Sleeping accommodations, both from the standpoint of facilities and rooms, are markedly inadequate. Hammocks and cots are often used instead of true beds; still 2 percent of the surveyed famihes did not possess even a hammock. Under such circumstances a crude pallet is arranged upon the floor as a place to sleep. Rural families suffer more acutely than urban because of inferior sleeping facilities. Likewise, overcrowding in their homes is more evident. Wliile 26 percent of the urban families have more than two rooms used for sleeping purposes, only 8 percent of the rural group have this amoimt of sleeping space. This difference is rendered more striking when it is recalled that the average urban family has 4.9 members, whereas the average size of the rural family is 5.8. The crowded condition of rural Puerto Rican homes is further emphasized by the fact that 30 percent of 539 rural families with 9 or more individuals have only one sleeping room. Overcrowding to this extent was reported by only 16 percent of the 233 urban families of tliis size. Such a high degree of I congestion undoubtedly facilitates the spread of transmissible diseases. Obviously, in the homes described, it is not possible to establish satis-

factory conditions for the accommodation of sick persons who require bed care. This throws an added burden on the hospitals.

The sanitation status in rural areas is of particular interest since it has a direct hearing upon the prevalence of intestinal parasites. Infes tation with hookworm especially is a problem of grave importance in Puerto Rico. Some method of excreta disposal was reported as readily available to all but 4 percent of the town families. About 20 percent of the houses are connected vdth a sewer. Sixty-five percent of the urban families have latrines, three-fifths of which are classed as being in good sanitary condition, and the remainder as poor. The latrines of neighbors are used by the other 10 percent of the town families. In the rural sections, 40 percent of the families have no facilities for excreta disposal; 48 percent own latrines, one-half of which are rated sanitary, the other half being in poor condition; and 10 percent of the rural families use the latrines belonging to neighbors. Only 2 percent of the homes are cormected with a private sewer.

Inasmuch as accessibility to transportation might exert a direct influence upon the availability of medical service, this point was determined for 5,891 families. Distance from a passable road was used as the criterion of accessibility.

Thirty-six percent of the total number of famihes lived in towns and 8 percent were classed as suburban famihes. Both groups were re garded as accessible to transportation facihties. The rural familes were subdivided into two classes: Those living on a paved or dirt road, and those on a path more than one-half mile from the nearest road. It was found that 18 percent of the total number of families hved on a paved or other passable road. Two percent of all families visited hved in homes located on a path approximately 1 mile from the nearest road on which an automobile could travel; 22 percent were situated on paths at distances ranging from 2 to 3 miles from such a road; and about 14 percent were more than 3 miles distant from the nearest motor transportation. Since these homes located on paths can be reached only on foot or horseback, the difhculty of securing medical care when illness occurs is easily understood. Frequently the only possible means of providing a patient with medical care is to carry him,in the manner pictured in figure 6, to the nearest physician or hospital.

Coastal municipalities hold decidedly the most favorable position from the standpoint of accessibility of homes to transportation. Figure 7 illustrates a rural section of the interior. It is noted that paths constitute the only outlet from the homes shown. Nearly onehalf of the rural homes in the center of the island, as compared with 5 percent of aU others considered, are more than 3 miles from a paved or dirt road.

FiuURE 7—This section of the interior shows the inaccessibiiity of homes to transportation. These dweiiings are located on patiis and can bo reached only on foot or iior.seback.

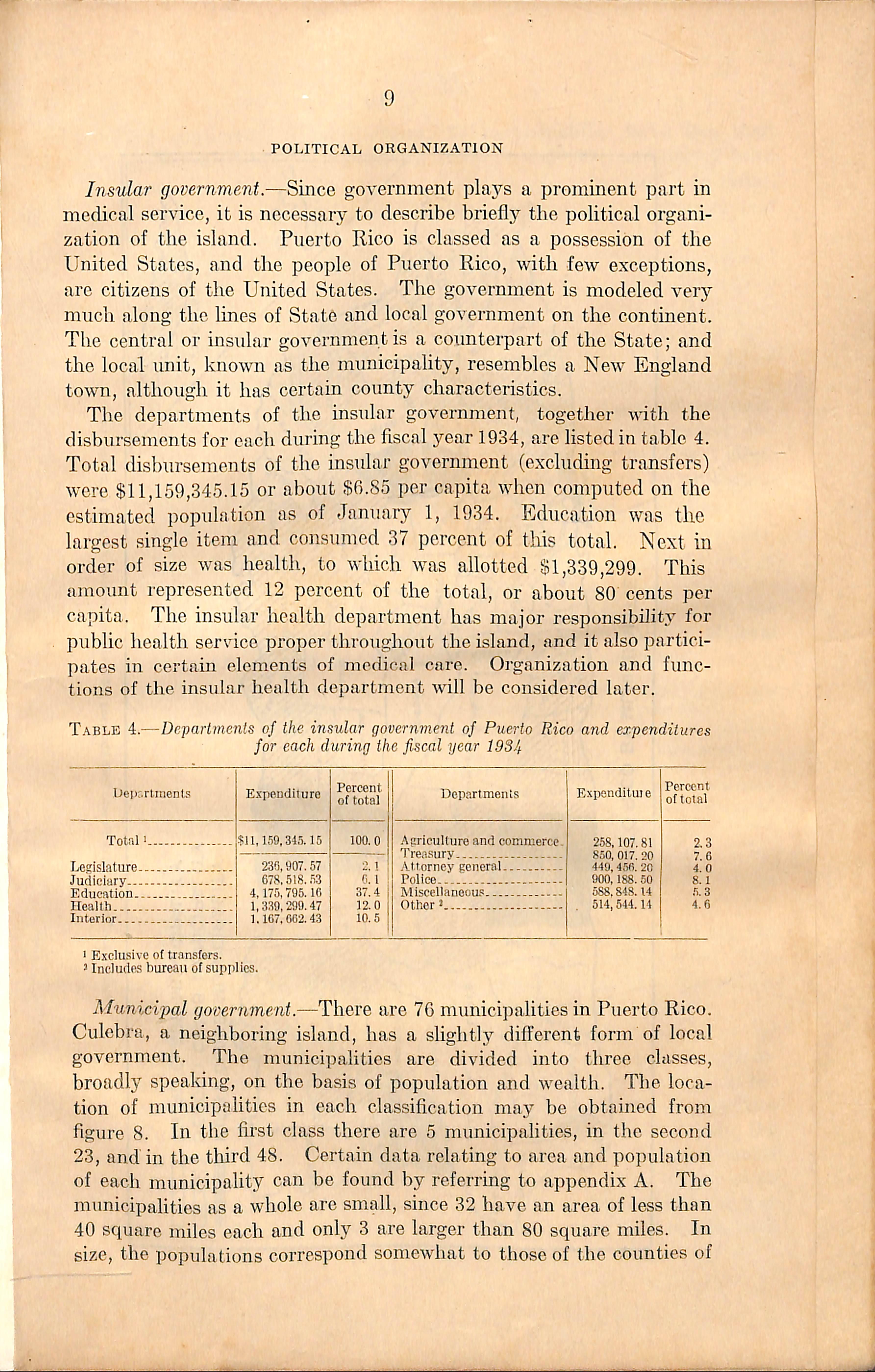

Insular government.—Since government plays a prominent part in medical service, it is necessary to describe briefly the political organi zation of the island. Puerto Rico is classed as a possession of the United States, and the people of Puerto Rico, with few exceptions, are citizens of the United States. The government is modeled very much along the lines of State and local government on the continent. The central or insidar government is a counterpart of the State; and the local unit, known as the municipality, resembles a New England town, although it has certain county characteristics.

The departments of the insular government, together with the disbursements for each during the fiscal year 1934, are listed in table 4. Total disbursements of the insular government (excluding transfers) were $11,159,345.15 or about $6.85 per capita when computed on the estimated population as of January 1, 1934. Education was the largest single item and consumed 37 percent of this total. Next in order of size was health, to which was allotted $1,339,299. This amount represented 12 percent of the total, or about 80 cents per capita. The insular health department has major responsibility for public health service proper throughout the island, and it also partici pates in certain elements of medical care. Organization and func tions of the insular health department will be considered later.

Table 4.—Departments of the insular government of Puerto Rico and expenditures for each during the fiscal year 19S4

Departmenls

Municipal government.—There are 76 municipalities in Puerto Rico. Culebra, a neighboring island, has a slightly different form of local government. The municipalities are divided into three classes, broadly speaking, on the basis of population and wealth. The loca tion of municipalities in each classiflcation may be obtained from figure 8. In the first class there are 5 municipalities, in the second 23, and in the third 48. Certain data relating to area and population of each municipality can be found by referring to appendix A. The municipalities as a whole are small, since 32 have an area of less than 40 square miles each and only 3 are larger than 80 square miles. In size, the populations correspond somewhat to those of the counties of

Figure 8.—The Island of Puerto Rico showing political classification of the 76 municipalities.

the continental United States; 33 'municipalities have less than 15,000 inhabitants; 36, between 15,000 and 30,000; and only 7 have more than 30,000 inhabitants. The last group contains two cities, San Juan and Ponce, and the two largest towns, Mayaguez and Arecibo.

Actual funds available in each municipahty for the conduct of local government during 1934 are listed in appendix B. Study of this table reveals that the total usable fimds for the support of all municipal functions are generally low, only nine municipahties having more than $100,000 available. Funds used during the fiscal year for the public functions of municipalities in different classes are given in table 5. While the iusular government assumes certain important responsi bilities, nevertheless, local funds__arnjmsjifficient for the__prop-CJ_discharge of municipalTimctlon^yhic^ according AoAilass^Jirslr..1asR municipnlities have some degree of responsibility for protection of personsjindjroperty, maintenance of highways,_ sanitation, cor rection, ed^ation, recreation, and charity (which includes medical care). Second- and third-class municipalities are more restricted in th^-Junctions, and even the authorized services as a rule are not well developed—^largely because of insufficiehtTeveniie: Thus the needs of the people become "secondary—to~the—availability of local resources in deterniining municipal governmental programs.

Table 5.—Total and per capita expenditures for all purposes in first-, second-, and third-class municipalities of Puerto Rico during the fiscal year 1934

Of particular interest from the standpoint of this study are the appropriations by municipalities of each class for medical care. This item appears in government reports imder the heading "Beneficencia", and will he considered later in part III, Medical Care.

Emergency reliej administration.—The rehef problem created by the economic depression current at the tune of the survey overtaxed in sular and municipal resources. The Federal Government came to the assistance of the island. A special agency Isnown as the Puerto B,ico Emergency Relief Administration, which follows very closely the pattern of State emergency rehef organizations in the continental United States, was created to meet this situation. This agency since its estahhshment has assumed almost complete responsibility for ma terial rehef. Such assistance may take the form of food orders, cash

grants, or employment. At the time of the survey approximately 60 percent of the families visited,in second- and third-class municipalities were receiving relief of some form. The percentage in the first-class mrmicipalities was reported to be somewhat less. Expenditures for relief by the Puerto Rico Emergency Relief Administration at the time of the survey were slightly in excess of $1,000,000 per month, or approximately the same as the total cost of the insular government for the same period.

Obviously it would not be possible to appraise the existing health facilities in Puerto Kico, or to make recommendations regarding changes, without an imderstanding of how illness expresses itself in the population.

Three indices were used to measure the prevalence of iUness and physical impairment: Deaths reported to the insular health depart ment, spepial studies made by other investigators, and the family canvass which was conducted as a part of the survey herein described. Reports of communicable diseases filed with the insular health department furnished some information, but they were not regarded a,s being sufficiently complete for the purpose of portraying the incidence of these diseases.

Notwithstanding the fact that only a small proportion of cases terminate in death, mortality data may be accepted as one quantita tive measure of the more serious types of Ulness. Reporting of deaths in Puerto Rico is said to be very nearly complete. On the other hand, causes of death as stated on the death certificate are not re garded by the insular health department as very reliable, since a \large percentage of the patients either have no attendant for the last lihiess or receive care under circumstances where accurate medical liagnoses are difficult to make. Under the circumstances, it is posjible to make deductions regarding illness only on the basis of gross mortality and deaths by age groups.

It has already been demonstrated in table 2 that the death rate of Puerto Rico is extremely high when compared ivith that of the continental United States. The proportionately higher birth rate in Puerto Rico, to which attention has also been directed, might be one factor in elevating the gross death rate, but the difference between the two areas is far too great to be explained on this basis alone. While ^all the underlying causes may not be understood completely, it is reasonable to suppose that the rates must be influenced adversely by a diet inadequate from the standpoint of quantity and quality, coupled with defective housing and sanitation, and the other un favorable circumstances thet usually accompany low income. Puerto Rico, in common with many tropical sections, is afflicted with tlu-ee (13) 137904—37 3

disease conditions—malaria, dysentery, and hookworm infestation— which directly an5 indirectly contribute to its excess mortality. Jji-4ulditieHr-ttii>er-culosis is extremely prevalent, and at the present time it is reported to be more malignant than it was some years ago. .The differences between Puerto Rico and the continental United States in death rates for selected age groups may be noted by referring to table 6. Attention is directed especially to the relatively high infant death rate in Puerto Rico. The rate for this age group in Puerto Rico is 159 as compared with 58 in the States. The greatest relative difference in mortality between the two areas is found when children between the ages of 1 and 4 years are considered. The death rate of this age group is six times as high in Puerto Rico as in the States. On the continent more deaths in proportion to the total occur among adults over 65 years of age when the degenerative diseases of the heart and kidneys and malignancy begin to take their toll, but even for this age group, wherein death occurs most frequently in the United States, the rate is still higher for Puerto Rico, the rates being 80 for the States and 100 for the island.

Table 6.—Death rates for certain age groups in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States during the year 1934

i Population estimates for specified age groups were obtained by applying percentage distribution for 1930 to estimated population as of July 1, 1934.

* The Puerto Rican total includes 19 deaths of persons whose age was unknown and the total for the continental United States includes 1,671 deaths of such persons.

Mention has already been made of the unreliability in the reported causes of death. Under the circumstances, anything more than a few general statements on differential mortality hardly seems justified. /In Puerto Rico deaths from intestinal infections, manifesting themIselves as diarrheal conditions, exceed those from any other known 'cause. The greater part of mortality from intestinal disorders occurs among children. Tuberculosis and pneumonia also rank as impor tant causes of mortality on the island. Whooping cough appears to be the only contagious childhood disease which causes a higher death rate on the island than on the continent. Although environmental conditions would seem to facihtate the spread of typhoid fever in

Puerto Rico, deatlis from this disease are not encountered as frequently as might be expected. Mortality rates for malaria and hookworm infestation do not express the serious problem which these diseases present, since deaths reported from these causes are relatively few in proportion to the cases. Indirectly, however, they constitute a grave situation, as will be disclosed in the next section.

Outstanding health problems of the island of Puerto Rico have been the subjects of intensive investigation by other workers on previous occasions. Their findings are of sufficient importance in this connec tion to warrant summarization for those who may not have access to the original publications.

Malaria.—Malaria is believed to have been endemic when Puerto Rico was first colonized by the Spaniards. Its occurrence is said to be mentioned throughout the history of the island. In recent years its incidence is believed to have increased on account of growth in popidation along the coast and extension of irrigation in connection with the cultivation of sugarcane. Malaria may be found in all parts of the island, but it is along the coast and, to a much less extent, in the nearby foothills that it constitutes the greatest problem.

In 1920 Grant (5) reported malaria parasites in the blood of only 1.3 percent of persons living in the mountains, while on the coast he found an average rate of about 30 percent. Earl (6) at a later date found essentially the same situation in the coastal area, and from 5 to 6 percent positive blood smears for individuals of the mountainous sections that were studied. Malaria is not believed by him to be a serious problem in the foothills, although occasionally localized epidemics occur, some of which are rather severe. According to Earl and his associates, the percentage of the population along the coast showing enlarged spleens varied from 11 at Guayama to 56 at Humacao, while the percentage with parasites ranged from 16 at Guanica to 55 at Humacao. These investigators believe that malaria is transmitted at all seasons of the year, but the highest prevalence occurs during September, October, November, and December.

Hookworm.—Hookworm infestation is extremely common. At the present time persons harboring the parasites may be found in all parts of the island, although infestation is much higher in certain regions. Hill (7) states that, in general, infestation increases from the coast to the interior. Conditions in the coffee-growing sections are most favorable for the propagation of the parasite. Even on the coast HiU found the average worm burden to be about 200, a condition wliich in dicates a serious problem. In the interior the infestation reached an estimated intensity of 500 worms per person. There children from 3 to 4 years of age were found harboring on the average approxi-

mately 100 worms, while children from 5 to 9 years had almost 300 worms or close to the average adult infestation.

Nutritional disorders.—Poor nutrition is a great factor in reducing efiBciency and in lowering vitality; it may also be presumed bo in fluence adversely the resistance of a large percentage of the population to specific diseases. The physical condition of a sample of approxi mately 500 children was studied by Eliot (3) who took into account such criteria as skeletal growth and body weight, amount of sub cutaneous fat, muscular development, onset of dentition, color of mucous membranes, and other physical findings. It was recognized of course that direct comparison could not be made with the children of the continental United States because of differences of racial stock, climatic conditions, and perhaps other influences on growth and body build. Eliot, however, has this to say of the nutritional status of the .children of Puerto Rico: "There is no doubt that the general nutriuional condition of the great majority of Puerto Rican children, as iseen from the clinical point of view, is far from being as satisfactory ^s that of the children in the continental United States. Many of the most poorly nourished or atrophic children are in a class entirely outside the public health experience of the physicians on the study and can be compared only with the cluldren suffering from severe marasmus or starvation who are seen elsewhere in hospital wards. Excellently nourished children, moreover, are seldom found and then only among the yoimger infants. The great mass of children belong in a group whose nutritional condition would be called fair or poor in continental United States."

After using slightly different criteria, Mitchell (4) reached essen tially the same conclusions. He states: "A definite relationship hav ing been established between the physical measurements of the chil dren and various socio-economic factors, we may safely conclude that the evidence is consistent with the claim that the Puerto Rican children suffer a considerable nutritional handicap."

Infant mortality.—It is believed by the local health authorities that the deaths among infants under 1 year of age in proportion to the live births is unduly high, but any definite statement on this point would be difficult to substantiate. Reporting of births is loiown to be far from complete,while over 90 percent of deaths are said to be registered. This difference in reporting alone would tend to elevate the death rates of infants. The average infant mortality rates for the three latest 5-year periods covered by published reports are used in table 7 to show the trend in deaths among children under 1 year of age. It will be observed that the rates for the most recent 5-year period show a precipitous drop from those which maintained during previous years. This lowering of the infant mortality rate may be due in part to the extension of the child welfare program, notably the milk stations, but it is difficult to account for changes on this basis alone.

Table 7.—Average live births, infant deaths, and infant mortality rates in Puerto Rico during three 5-year periods, 1920-34

An analysis of the causes of infant deaths in Puerto Rico was made by Fernos and Pastor (8) a few years ago and the following partial summary quoted from their report describes the situation in a very concise fashion.

"Infant mortality in Puerto Rico is high. Families are large, the marrying age begins early, and the density of population is great. Infant mortality is influenced by these factors. The rate is higher in the towns along the western coast than elsewhere on the island. It is lower in the inland municipalities, and increases in direct proportion with the conglomeration of inhabitants. Mortality is higher in the black than in the white race, and among boys it is greater than among girls. It is much higher among illegitimate than among legitimate children, and is especially noticeable among children from 1 to 6 months of age. The principal direct cause is disease of the gastro intestinal system, especially the pathological entity or entities figuring in the death registers under the names of diarrhea and enteritis. Diarrhea and enteritis cause 31 percent of the deaths of children under 1 year of age in Puerto Rico."

It was not possible to conduct any special study of infant mortality during the survey of medical care, but the general observations tended to substantiate the conclusions reached by Fernos and Pastor.

Tuberculosis.—Tuberculosis was given as a cause of death on slightly more than 16 percent of the death certificates filed with the insular department of health during the year 1934. As a reported cause of death it outranked all other diseases except diarrhea and enteritis, when the latter conditions were considered for all age groups. The accuracy of diagnosis may be open to question, first because of the inherent difficulty in arriving at such a conclusion, and second, because many times there is no physician in attendance for the last illness.

Notwithstanding whatever errors may exist in the mortality data, there is ample proof to support the contention that tuberculosis is a definite public-health problem, and perhaps the most outstanding one, on the island at the present time. According to some students of the subject, the disease is on the increase. Tliis would seem to

be borne out by a comparison of the death rates of Puerto Rico and continental Uaited States over a period of 15 years. During the most recent 5-year period, 1930-34, the average death rate from tuber culosis was nearly 5 times as high on the island as in the States, re spectively,296 and 64 deaths per 100,000 population being attributed to this cause. Tliis difference between the two areas is considerably greater than that which existed during the period 1920-24. At that time the Puerto Rican death rate from tuherculosis was just twice that of the continent, the corresponding average rates being 197 and 98. While the data on tuherculosis mortality given for Puerto Rico may not be comparable in all respects with those for the continental United States, yet the gross picture presented is that of a declining rate for the continental United States and a gradual upward trend in Puerto Rico.

After an exhaustive study of tuberculosis on the island, Townsend (9) became convinced that the alleged prevalence of tuberculosis is perhaps an understatement of the true condition. His findings may be summarized as follows; "The death rate from tuberculosis is about twice that of the continental United States. Pulmonary tuherculosis overshadows aU other forms—bone, joint, and glandular types are very rare. Rates are highest in cities.and especially among tobacco factoi-y workers. The disease is less frequent among those engaged in growing sugarcane than among those in other agricultural pursuits and it is comparatively rare in rural mountain dwellers. Milk is not a factor in disseminating the disease. Low income, overcrowding, inadequate diet, and chronic disease—especially malaria and hook worm, are beheved to be predisposing factors."

Death reports, however complete, disclose only a small part of the infection present in a population. A common procedure for determin ing the amount of infection is the application of the tuhercuhn test to a sample of the population. This plan was followed by Pastor (10) as part of a comprehensive study into the health of Puerto Rican children which was made by the American Child Health Association in 1930. The group tested included 189 urban and 335 rural children 8 years of age, and 691 urban and 348 rural cliildren of 10 years, or in all 1,563. The percentages of children in Puerto Rico showing positive reaction are contrasted in table 8 with the findings of other Workers using a similar method. According to the data presented in this table, Puerto Rico, with one exception, has a higher percentage of children showing positive reaction to tuberculin than any other area under consideration. Only in Vienna did a higher percentage of 10-year old children show positive reactions than in Puerto Rico; 8-year old cliildren there, however, merely approached the Puerto Rican record. In no part of the continental United States reported

sr'.iw-r.

19, in this table do the children show more than two-tliu'ds as much infection as those of Puerto Rico, and some have only about one-third the amount.

Table 8.—Percentage of children tested in certain areas who showed a positive reaction to tuberculin

Area

Urban: Puerto Rico.. Vienna Buenos Aires, Munich Minneapolis. Philadelphia.

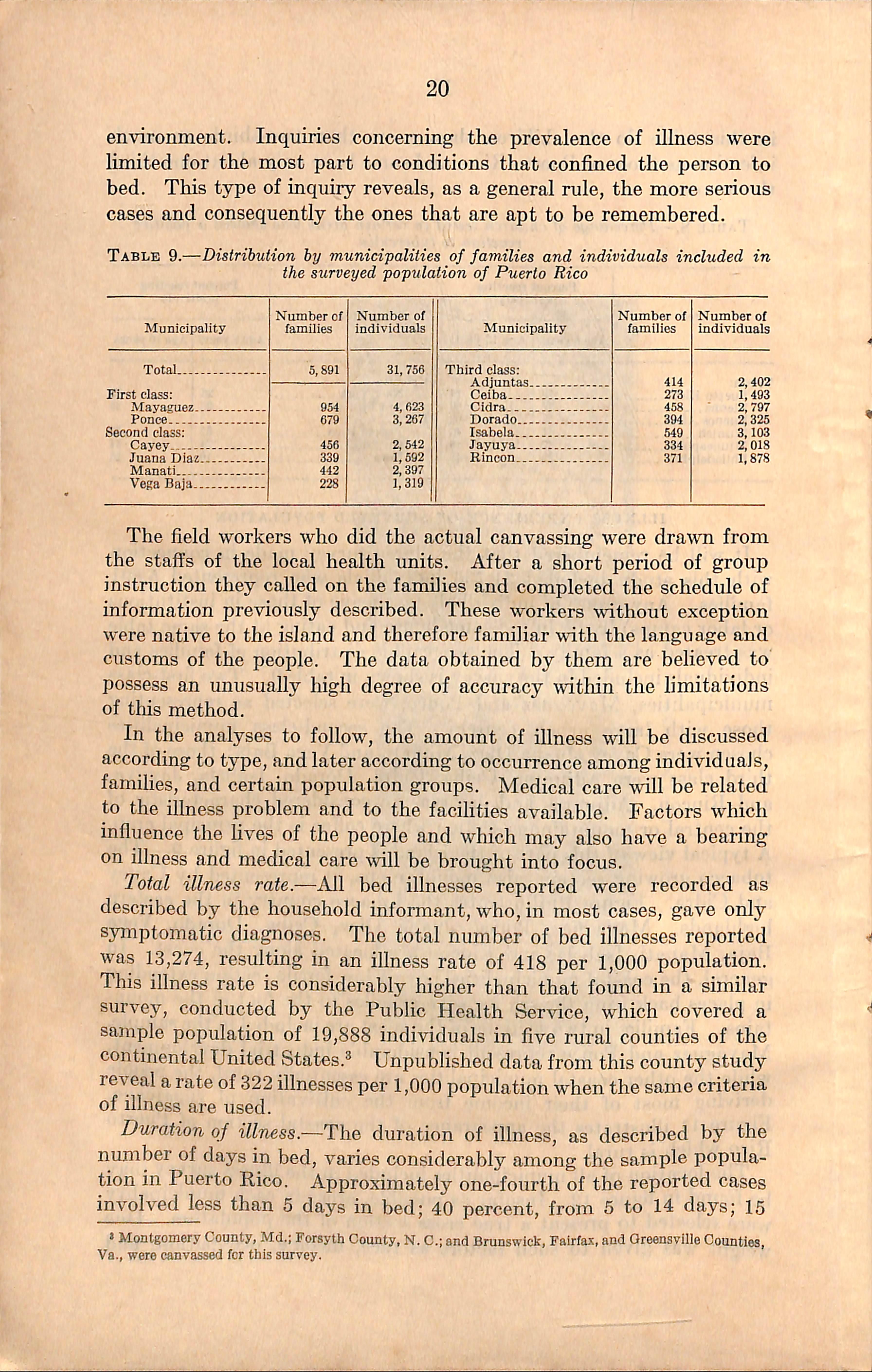

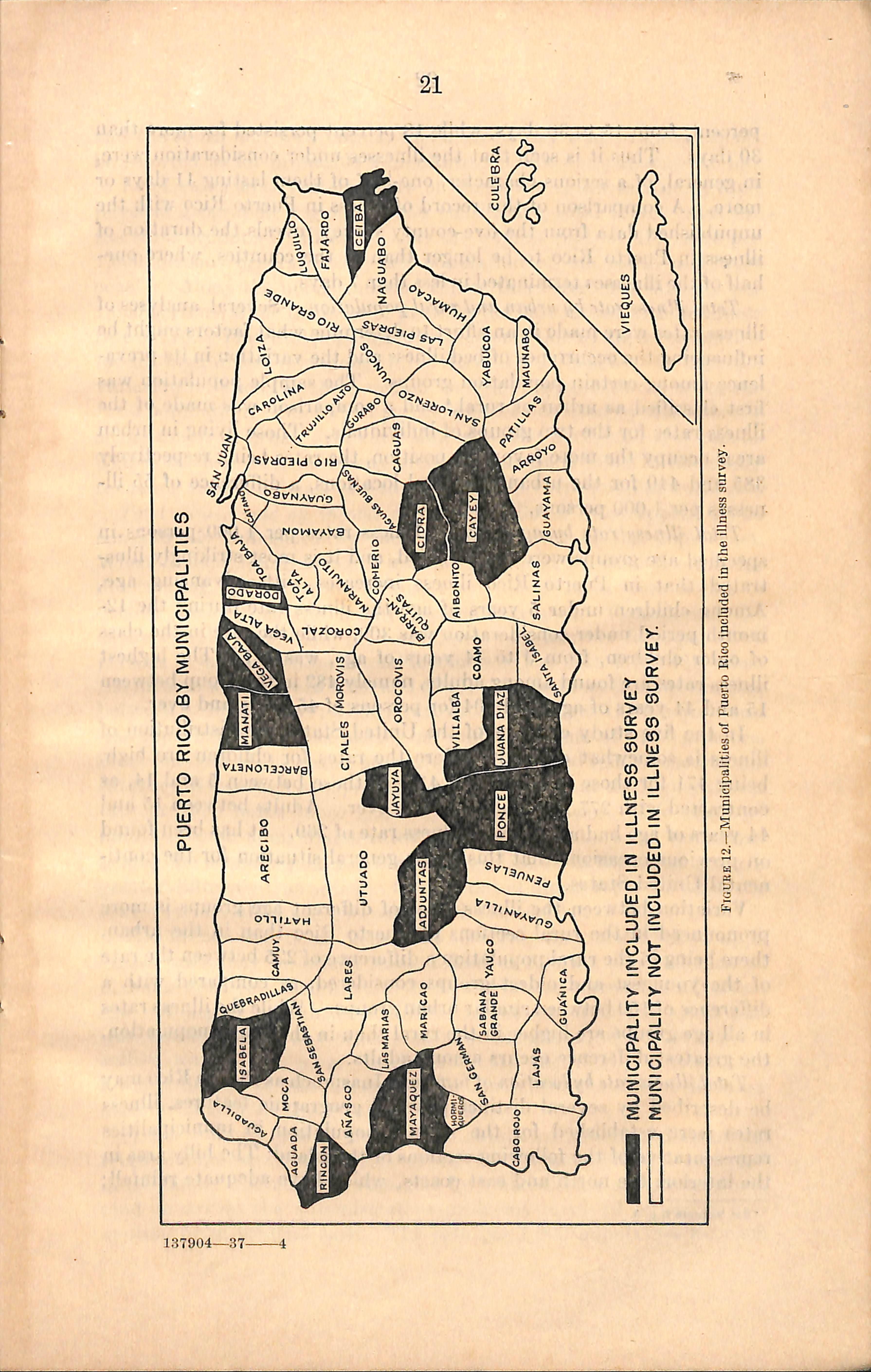

It whl be remembered that the Ulness survey made in connection wth this study included 31,756 individuals who represented 5,891 families. Any group of individuals (exclusive of those in institutions or labor camps)living in the same house and eating at the same table was treated as a family. The geographic distribution of families and individuals included in the survey is shown in table 9. Two first-class municipalities, Mayaguez and Ponce, were selected as representing those wdth large urban centers. The second-class municipalities chosen were Cayey, Juana Diaz, Manati, and Vega Baja; those of the third class were Adjuntas, Ceiba, Cidra, Dorado, Isabela, Jayuya, and Rincon. Adjuntas and Jayuya are considered characteristic of the central or mountainous section where coffee is the principal crop. A typical view of tliis part of the island is presented in figure 9. The tobacco growing section, also mountainous, is represented by Cayey and Cidra. Figure 10 illustrates the tobacco country in the eastern higlilands. Mayaguez, Ponce, Juana Diaz, Ceiba, Dorado, Yega Baja, Manati, Isabela, and Rincon are located along the coast. In general, the coastal municipalities have a low fertile section extending in places back from the sea for several miles to the foot of the moun tains. Families in two sections of the coast are included in the sample. Mayaguez and Ponce represent considerable industrial development, wliile the other coastal municipalities are essentially rural, the people deriving most of their income from the cultivation of sugarcane. Figure 11 illustrates the appearance of the coastal section of Puerto Rico which is rural.

The location of aU municipalities included in the illness survey may be found in figure 12. Insofar as possible, areas in each municipality were selected to present a true cross section of the population. Due weight was given to such factors as race, income, occupation, and

environment. Inquiries concerning the prevalence of Ulness were limited for the most part to conditions that confined the person to bed. This type of inquiry reveals, as a general rule, the more serious cases and consequently the ones that are apt to be remembered.

Table 9.—Distribution by municipalities of families and individuals included in the surveyed 'population 0/ Puerto Rico

The field workers who did the actual canvassing were drawn from the staffs of the local health units. After a short period of group instruction they called on the families and completed the schedule of information previously described. These w-orkers without exception were native to the island and therefore familiar with the language and customs of the people. The data obtained by them are believed to possess an unusually liigh degree of accuracy within the h'mitations of this method.

In the analyses to follow, the amount of illness wiU be discussed according to type,and later according to occurrence among individuals, famihes, and certain population groups. Medical care will be related to the illness problem and to the facilities available. Factors which influence the hves of the people and which may also have a bearing on illness and medical care Avill be brought into focus.

Total illness rate.-—All bed illnesses reported were recorded as described by the household informant, who,in most cases, gave only symptomatic diagnoses. The total number of bed illnesses reported was 13,274, resulting in an illness rate of 418 per 1,000 population. This illness rate is considerably higher than that foimd in a similar survey, conducted by the Public Health Service, which covered a sample population of 19,888 individuals in five rural counties of the continental United States.^ Unpublished data from this county study reveal a rate of 322illnesses per 1,000 population when the same criteria of illness are used.

Duration of illness.-—The duration of illness, as described by the number of days in bed, varies considerably among the sample popula tion in Puerto Rico. Approximately one-fourth of the reported cases involved less than 5 days in bed; 40 percent, from 5 to 14 days; 15 > Montgomery County, Md.;Forsyth County. N.C.;and Brunswick,Falrfa.x, and Greensville Counties, Va., were canvassed fcr tliis survey.

MUNICIPALITY INCLUDED IN ILLNESS SURVEY

MUNICIPALITY NOT INCLUDED IN ILLNESS SURVEY.

Figure 12.—Municipalities of Puerto Rico included in the illness survey.

percent, from 15 to 30 days, while 18 percent persisted for more than 30 days. Thus it is seen that the illnesses under consideration were, in general, of a serious character, one-half of them lasting 11 days or more. A comparison of this record of illness in Puerto Rico with the unpublished data from the five-county survey reveals the duration of illness in Puerto Rico to be longer than in the counties, where onehalf of the illnesses terminated in less than 7 days.

Total illness rate by urban and rural population.—Several analyses of illness rates were made in an effort to determine what factors might be mfluencing the occurrence of bed illness and the variation in its preva lence among certain population groups. The sample population was &st classified as tirban or rural,^ and a comparison was made of the illness rates for the two groups of individuals. Those living in urban areas occupy the more favorable position, the rates being respectively 385 and 440 for the urban and rural locations, a difference of 55 ill nesses per 1,000 persons.

Total illness rate by age group.—Illness rates per 1,000 persons in specified age groups were next studied, and it is most strikingly illus trated that in Puerto Rico illness increases with advancing age. Among children under 5 years of age the illness rate during the 12month period under consideration was 309, while the rate in the class of older children, from 5 to 14 years of age, was 327. The highest illness rates are found among adults, namely 482 in the group between 15 and 44 years of age, and 504 for persons of 45 years and over.

In the five study counties of the United States the distribution of illness is somewhat different. Here the rates for children are high, being 471 for those under 5, and 412 for those between 5 and 14, as contrasted with 277 for adults of 45 or over. Adults between 15 and 44 years of age had a still lower illness rate of 269. It has been found on previous occasions that this is the general situation for the conti nental United States.

Variation between the illness rates of different age groups is more pronounced in the rural sections of Puerto Rico than in the urban, there being in the rural population a difference of 225 between the rate of the youngest and oldest groups considered, as compared with a difference of 159 between similar urban groups. While the illness rates in all age groups are higher in the rural than in the urban population, the greatest difference occurs among adults.

Total illness rate by location offamily.—Inasmuch as Puerto Rico may be described by several distinct physical geograpliic features, illness rates were established for the sample population in municipalities representative of the following sections of the island: The hilly area in the interior, the north and east coasts, which have adequate rainfallj

'See footnote 2, p. 6.

and the south and west coasts, which are so dry that irrigation must be resorted to for profitable agriculture. These comparisons are felt to be of value since certain types of illness are characteristic of each physical geographic region. Upon considering total illness rates for the three sections it is learned that the highest rate, or 477 cases per 1,000 persons occurs among the population of the south and west coasts. Along the north and east coasts there were 399 illnesses per 1,000 persons, while the interior presents the best record with an illness rate of 370. The rural population,rather than the urban,is responsible for the high illness rate along the south and west coasts. In fact, the variation between the three regions is, in all cases, accentuated in the rural population. One rather surprising fact disclosed by this analysis is the excess of urban over rural illness on the north and east coasts. This is the first instance of any investigation made so far in this study revealing an urban illness rate that exceeds the corresponding rural one.

Toted illness rede by income of family. Illness rates appear to be considerably influenced by the economic status of the population. When annual family money income was used as the criterion for determinmg the economic status, total illness rates were noted to decline steadily as the family income increased. Considering the entire sample population, the total illness rate was 444 cases per 1,000 persons in families whose annual income was less than $100;436, when the income was between $10P and $249; 363,for those families earning between $250 and $749; while a rate of 297 cases per 1,000 individuals was reported in families having an annual income of $750 or more. Since one-half of the entire population of the island falls in the income category of less than $100,it will be appreciated that the higher illness rate prevails much more generally than the lower. The effect of family income upon illness rates would seem to be more important among the urban population than the rural, since in the urban group a greater difference was noted in the amount of illness reported when the lowest income class was compared with the highest.

The influence of such factors as location, age, and income upon illness rates may be briefly summarized as follows: The amount of illness is relatively liigh in rural areas and among persons of advanced age. A higher prevalence of illness maintains upon the south and west coasts than in any other section of the island, while the interior suffers least. The more nearly adequate the family income, the lower is the illness rate; or, stated conversely, the occurrence of illness becomes higher as the income level drops.

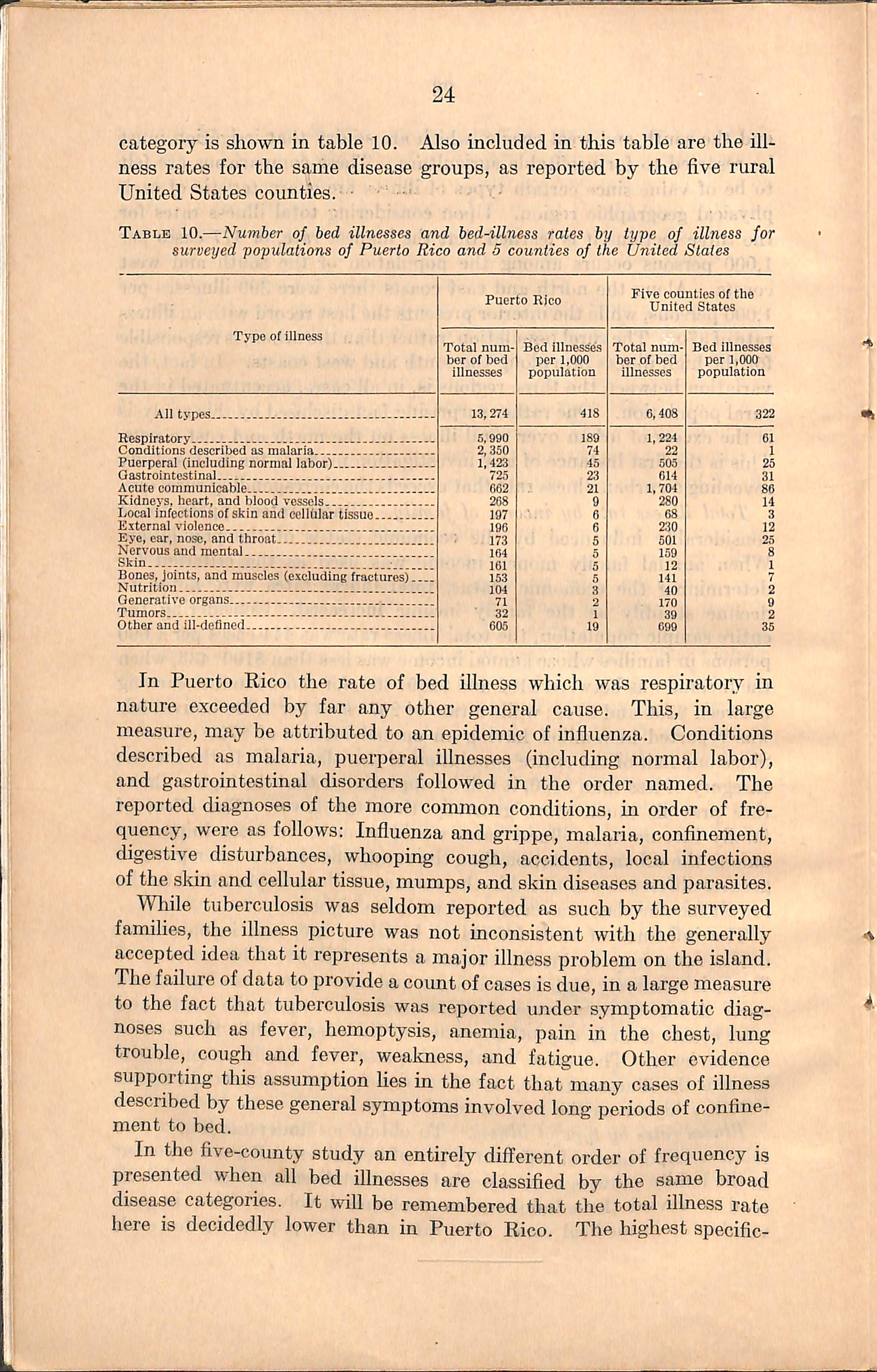

Illness rates by type of illness.—To obtain an understanding of the relative importance of different types of bed illness, all cases reported in the family canvass were classified by broad disease categories which tend to reveal the administrative problems involved either in pre vention or in medical care. The rate per 1,000 population for each

category is shown in table 10. Also included in this table are the ill ness rates for the same disease groups, as reported by the five rural United States counties. ■ ■ '

Table 10.—Number of bed illnesses and bed-illness rales by type of illness for surveyed populations of Puerto Rico and 5 counties of the United Stales

described as malaria

(including normal labor)

Kidneys, heart, and blood vessels

Local infections of skin and cellular tissue

External violence

Eye, car, nose, and throat

Nervous and mental II

Skin j

Bones, joints, and muscles (excluding fractur^)

Nutrition

Generative organs

Tumors

and ill-defined

In Puerto Rico the rate of bed illness which was respiratory in nature exceeded by far any other general cause. This, in large measure, may be attributed to an epidemic of influenza. Conditions described as malaria, puerperal illnesses (including normal labor), and gastrointestinal disorders followed in the order named. The reported diagnoses of the more common conditions, in order of fre quency, were as follows: Influenza and grippe, malaria, confinement, digestive disturbances, whooping cough, accidents, local infections of the sldn and cellular tissue, mumps,and skin diseases and parasites. While tuberculosis was seldom reported as such by the surveyed families, the illness picture was not inconsistent with the generally accepted idea that it represents a major illness problem on the island. The failure of data to provide a coimt of cases is due,in a large measure to the fact that tuberculosis was reported under symptomatic diag noses such as fever, hemoptysis, anemia, pain in the chest, lung trouble, cough and fever, wealaiess, and fatigue. Other evidence supporting this assumption hes in the fact that many cases of illness described by these general symptoms involved long periods of confine ment to bed.

In the five-county study an entirely different order of frequency is presented when all bed illnesses are classified by the same broad disease categories. It will be remembered that the total illness rate here is decidedly lower than in Puerto Rico. The highest specific-

illness rate in the counties was caused by acute communicable dis eases. The epidemic of measles, previously referred to, was partly responsible for the fact that this rate was four times as high as the corresponding one in Puerto Rico. Wliile the rate of gastrointestinal disturbances reported in the counties exceeded that of Puerto Rico, this, no doubt, was due to the fact that indefinite diagnoses, such as indigestion and stomach trouble unqualified, swelled the total for the counties. Such Ulnesses as diseases of the kidneys, heart, and blood vessels; disorders of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat; diseases of the bones, joints, and muscles; and tumors probably attained higher rates in the counties than in Puerto Rico because of the greater tend ency on the continent to obtain medical diagnosis and thus assign symptoms to the organs or parts of the body involved. Moreover, the people of Puerto Rico are not likely to rest in bed imless the illness has a large element of disability. The illness picture of Puerto Rico becomes most unfavorable when rates of respiratory and malarial conditions are compared with corresponding ones in the counties. Puerto Rico also showed an excess of puerperal conditions. This is to be expected in view of the facts that the birth rate for the island as a whole is relatively Irigh, and that the majority of the puerperal con ditions listed constitute cases of normal labor. While childbirth may not be considered a true illness in every sense of the word, yet it represents a definite need for medical care and so is included as a type of iUness for the purposes of this report.

To determine which types of ULness were more prevalent in the country than in cities or to\vns, all reported illnesses were classified according to broad disease categories, and the urban and rural rates were computed for each. Rural rates significantly exceeded urban for the following types of illness: Respiratory, conditions described as malaria, and acute communicable diseases. Some excess of puer peral illnesses was also noted in the rural population. No essential difference was found between the urban and rural groups for any other iUness category.

An analysis was made of illness rates in broad disease categories by geographic regions of the island. The purpose of this study was to ascertain which types of illness were responsible for the high illness rates in different sections. The most important difference between the rates of the south and west coasts and those of the north and east coastal regions lay in the amount of respiratory illness in the two areas. A rate of 236 was recorded in the municipalities of the south and west coasts, as compared with 172 for the interior, and 154 for the municipalities along the north and east shores. The area in the center of the island had less than one-half the rate of illness from conditions described as malaria as was reported by either coastal area. Gastrointestinal disorders also maintain a considerably lower rate in the interior.

The rate of acute communicable diseases, however, was higher in the interior than in cither area along the coast.

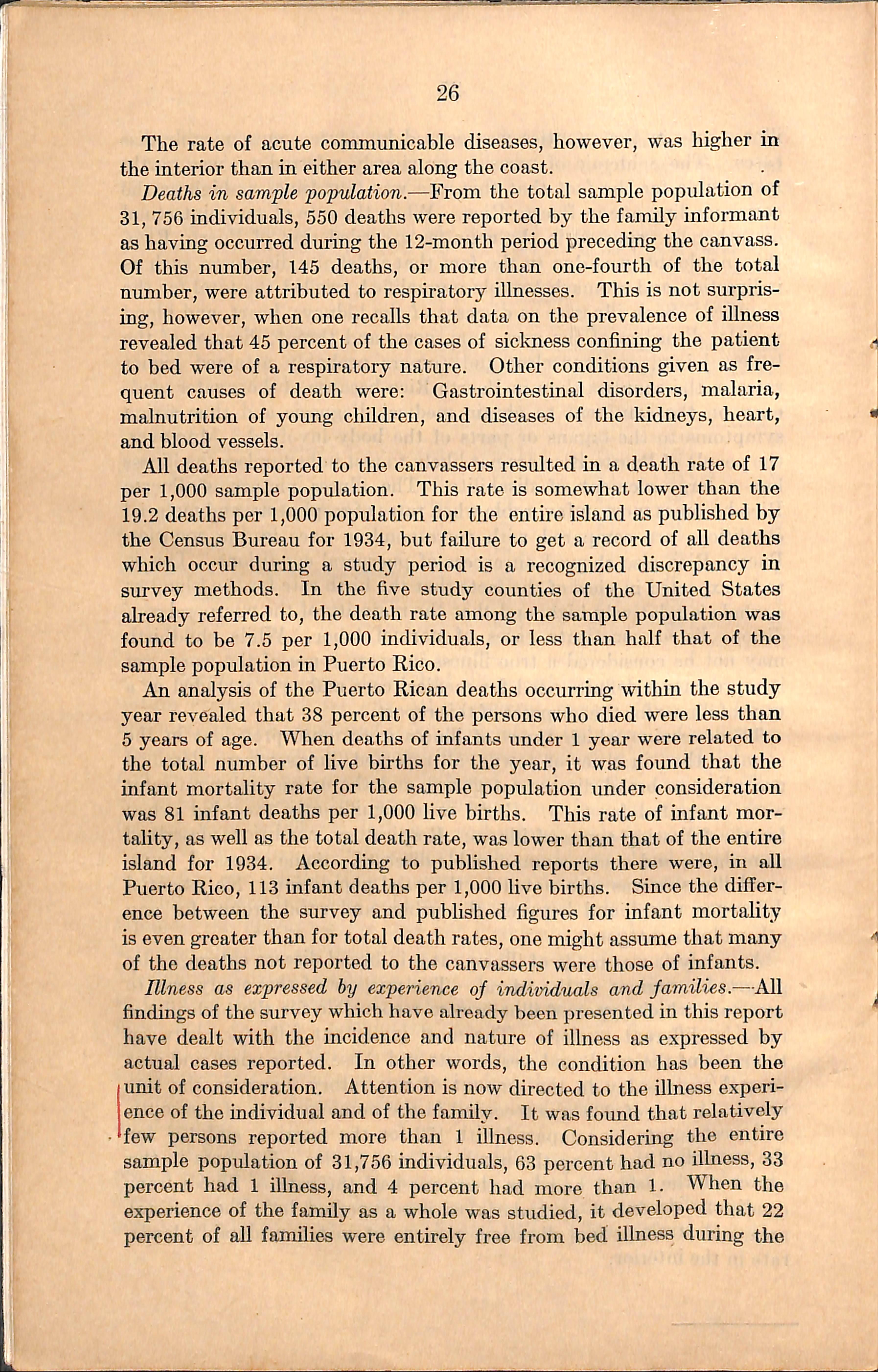

Deaths in sample population.—From the total sample population of 31,756 individuals, 550 deaths were reported by the family informant as having occurred during the 12-month period preceding the canvass. Of this number, 145 deaths, or more than one-fourth of the total number, were attributed to respiratory illnesses. This is not surpris ing, however, when one recalls that data on the prevalence of illness revealed that 45 percent of the cases of sicloiess confining the patient to bed were of a respiratory nature. Other conditions given as fre quent causes of death were: Gastrointestinal disorders, malaria, malnutrition of young cliildren, and diseases of the kidneys, heart, and blood vessels.

All deaths reported to the canvassers resulted in a death rate of 17 per 1,000 sample popxilation. This rate is somewhat lower than the 19.2 deaths per 1,000 population for the entire island as published by the Census Bureau for 1934, but failure to get a record of all deaths which occur during a study period is a recognized discrepancy in sm^vey methods. In the five study counties of the United States already referred to, the death rate among the sample population was found to be 7.5 per 1,000 individuals, or less than half that of the sample population in Puerto Rico.

An analysis of the Puerto Rican deaths occiirring within the study year revealed that 38 percent of the persons who died were less than 5 years of age. When deaths of infants under 1 year were related to the total number of live births for the year, it was found that the infant mortality rate for the sample population under consideration was 81 infant deaths per 1,000 live births. This rate of infant mor tality, as well as the total death rate, was lower than that of the entire island for 1934. According to published reports there were, in aU Puerto Rico, 113 infant deaths per 1,000 five births. Since the differ ence between the survey and published figures for infant mortality is even greater than for total death rates, one might assume that many of the deaths not reported to the canvassers were those of infants.

Illness as expressed by experience oj individuals and jamilies.—-All findings of the survey which have already been presented in this report have dealt with the incidence and nature of illness as expressed by actual cases reported. In other words, the condition has been the unit of consideration. Attention is now directed to the illness experi ence of the individual and of the family. It was found that relatively few persons reported more than 1 illness. Considering the entire sample population of 31,756 individuals, 63 percent had no illness, 33 percent had 1 illness, and 4 percent had more than 1. When the experience of the family as a whole was studied, it developed that 22 percent of all families were entirely free from bed illness during the

study year;45 percent suffered 1 or 2 illnesses, and 33 percent reported 3 or more. Upon comparing the illness record of urban famihes with that of the families of rural areas, the latter group appeared at a dis tinct disadvantage. Twelve percent of these families, and only half that proportion of the urban, had 6 or more illnesses during the year.

From data presented in foregoing sections it is apparent that the siclaiess hurden of the people of Puerto Rico is a heavy drain on their limited financial resources. It will also he recalled that the average number of persons per family for the island as a whole was 5.3 and that the average annual family income for a representative study group was $229. About 90 percent of the families included in the survey reported incomes of less than $500. Under such ch'cumstances only a very small percentage of families, those comprising the economically privileged group, could be expected to meet the costs of medical care through their private resources. The great majority do not have sufficient income to provide food, shelter, and clothing in amounts necessary to afford health and a reasonable degree of comfort. There is no large group vdth moderate income that might purchase medical service if the costs were distributed over time and through the popula tion by some prepaj'ment or insurance scheme. Because of these economic considerations medical care in Puerto Rico, for most of the population, must be a public service supported through taxation.

While the municipal governments constitute the primary agencies for providing medical care, it would be misleading if one were to exclude from consideration those facilities that are represented by private physicians, voluntary hospitals, local health units, and the institutions of the insular health department.

Physicians.—The total number of physicians in Puerto Rico is 436. Of this number 228 are located in the 5 first-class municipalities, 145 being in San Juan alone. In the 23 second-class municipalities, there are 131 physicians, and the remaining 77 physicians are divided among 43 of the third-class municipalities. Five third-class munici palities have no resident physician. A large percentage of the 41 physicians residing in Rio Piedras and Bayamon—both suburbs of San Juan, but rated as second-class municipalities—have offices in San Juan. Thus, in effect, the number of physicians practicing in the San Juan area is increased to 186, and the number available to the entire group of second-class municipalities is reduced to 90. From these fio'ures it is evident that the smaller and more rural municipalities suffer most from the lack of medical personnel. Table 11 shows the 137004—37 -•')

distribution of ali physicians on the island by connection as well as by class of municipality.

Table 11.—-Number of first-, second-,and third-class municipalities of Puerto Rico having resident physicians, and total nwnher of physicians according to connection residing in each class

Of the 436 physicians in Puerto Eico, 170 are classified as engaged in private practice exclusively, and it may be assumed that fees from patients constitute their principal source of income. More than half of these private medical practitioners are located in the more populous first-class municipalities. The insular health department employs 50 physicians, exclusive of health officers, who are engaged either in insti tutional service or in administrative work. There are 26 physicians connected with various local health units,and 59 have other affiliations. Those physicians classed as "other" are largely retired, a few are medical officers of the Army and Navy,and the remainder are engaged in research or teaching. Of the 131 municipal physicians, 119 are sustained by beneficencia, and the salaries of 12 are paid by the insular government. Taking the island as a whole, and including all physi cians, the number of persons per physician is approximately 3,750. When figured on the basis of first-,second-,and third-class municipahties having resident physicians, there are, respectively, about 1,750, 4,050, and 9,100 persons per physician. If one were to deduct from the total those full-time salaried physicians who are connected with health agencies, with institutions, and those described in table 11 by the designation "other", there would remain about 300 physicians. In reality, therefore, the average population load per physician engaged in caring for the general population is about 5,000.

Actually, physicians do not limit their practice to the municipal ities in which they reside; however, it is felt that the clearest picture of available medical personnel can be presented by using the munici pality as a basis of consideration. The uneven distribution of physi cians is fully illustrated by these findings; Ceiba, Las Marias, Luquillo, Moca, and Penuelas, represencing an estimated population of 55,000, have no resident physician. In striking contrast, San Juan has a resident medical practitioner for each 900 persons. The wide range in population load per physician for the other municipalities'may be

appreciated when one finds that in 17 municipalities a single physician is responsible for the care of 1,000 to 5,000 inhabitants; in 33 municipaUties the corresponding ratio is between 5,000 and 10,000 persons per physician;in 13, between 10,000 and 15,000; and in 7, over 15,000. The responsibility resting upon municipal physicians only will he discussed in the section treating municipal facilities.

Dentists.—The people of Puerto Rico are served by 143 dentists. Dentists as well as physicians have, congregated in the larger cities. In the 5 first-class municipalities there are 88 dentists; 46 are located in 19 of the 23 second-class municipalities; and only 9 are found in 6 of the 48 third-class municipalities. The need for additional dental service can well be appreciated when one considers that there are 42 third-class municipalities, representing a population of 572,775, and 4 second-class municipalities, representing 56,250 persons, without a single practicing dentist. When only the municipalities which have 1 or more practicing dentists are considered, the number of persons per dentist is about 4,500 for the first-, 10,500 for the second-, and 14,000 for the third-class group of municipalities. Eight of the dentists in the first-class municipalities and 6 in the second class are employed by beneficencia, usually for part-time service. The distribution of den tists, even more than that of phj'^sicians,is determined by the economic position of people in the several sections of the island.

General hospitals.—The island of Puerto Rico has 97 general hospital buildings, though 7, belonging to municipalities, are not used for care of patients. Of the total number, 61 belong to the municipalities; 34 are privately owned; and 2 district general hospitals are operated by the insular health department. Table 12 shows the distribution of these general hospitals according to class of municipality, and the number of hospital beds represented by each.

Table 12.—Total number of general hospitals and their bed capacities in first-, second-, and third-class municipalities of Puerto Rico according to ownership of hospitals

I There are in this group 7 municipel hospital buiidings, representing 116 beds, which are not being used tor hospitai purposes.

In all Puerto Rico there are 3,472 general hospital beds which are available for use. Of this number 1,764, or more than one-half, are

in the 5 first-class municipalities; 1,272 are in the 23 second-class municipahties; and 436 are in 27 of the 48 municipalities of the thirdclass group. Considering the island as a whole, there is 1 available hospital bed for every 470 persons. In the first-class municipalities the ratio is 225 persons per hospital bed; in the second-class group, about 425 persons per bed; and in the tliird, where hospitals are in use, there is only 1 available hospital bed for each 945 persons. No hospital beds are available in 21 of the tliird-class municipalities which have a total population of approximately 287,500.

With one exception, privately owned hospitals are located in the first- and second-class municipalities. Lares is the only third-class municipality having a privately owned general hospital. The capacity of this institution is 10 beds. The 7 private hospitals in San Juan have a total capacity of 425 beds and the 3 in Ponce have 288 beds. Two of those in San Juan and 2 in Ponce have between 100 and 130 beds each. The only other private hospital vnth more than 100 beds is located in Rio Piedras, a second-class municipahty, but really a suburb of San Juan. There are 150 beds in tliis hospital. Each of the 5 first-class municipalities and aU but 1 of the secondclass group have a municipal general hospital. San German is the exception. This municipality, however, contracts with a private hospital for the use of 25 beds by patients admitted through the beneficencia office. In the third-class group 34 of the 48 munici palities have a municipal hospital, although 7 of these buUdings are not in use for hospital purposes. Generally speaking, the capacity of municipal hospitals varies with the class of municipality. The average number of beds in hospitals owned by first-class municipalities is about 150, as contrasted with an average of 33 beds in the hospitals of the second, and 16 beds in those of the third class. A more detailed discussion of municipal hospitals will appear in the section of this report devoted exclusively to municipal facilities.

It must be recognized, of course, that, while the first class munici palities have a striking advantage over the other two groups in all facilities for the care of the sick, a similar situation would, no doubt, be found in the study of many areas of the continental United States, since the larger cities generally have more and better equipped hos pitals than are found in rural sections. In reality, many secondand third-class municipalities are unable to support the hospitals they now have. The presence or absence of a hospital in a munici pahty should not be interpreted as expressing the availability of hospital facilities, since service can be obtained on a contractual basis from hospitals located in neighboring municipalities.

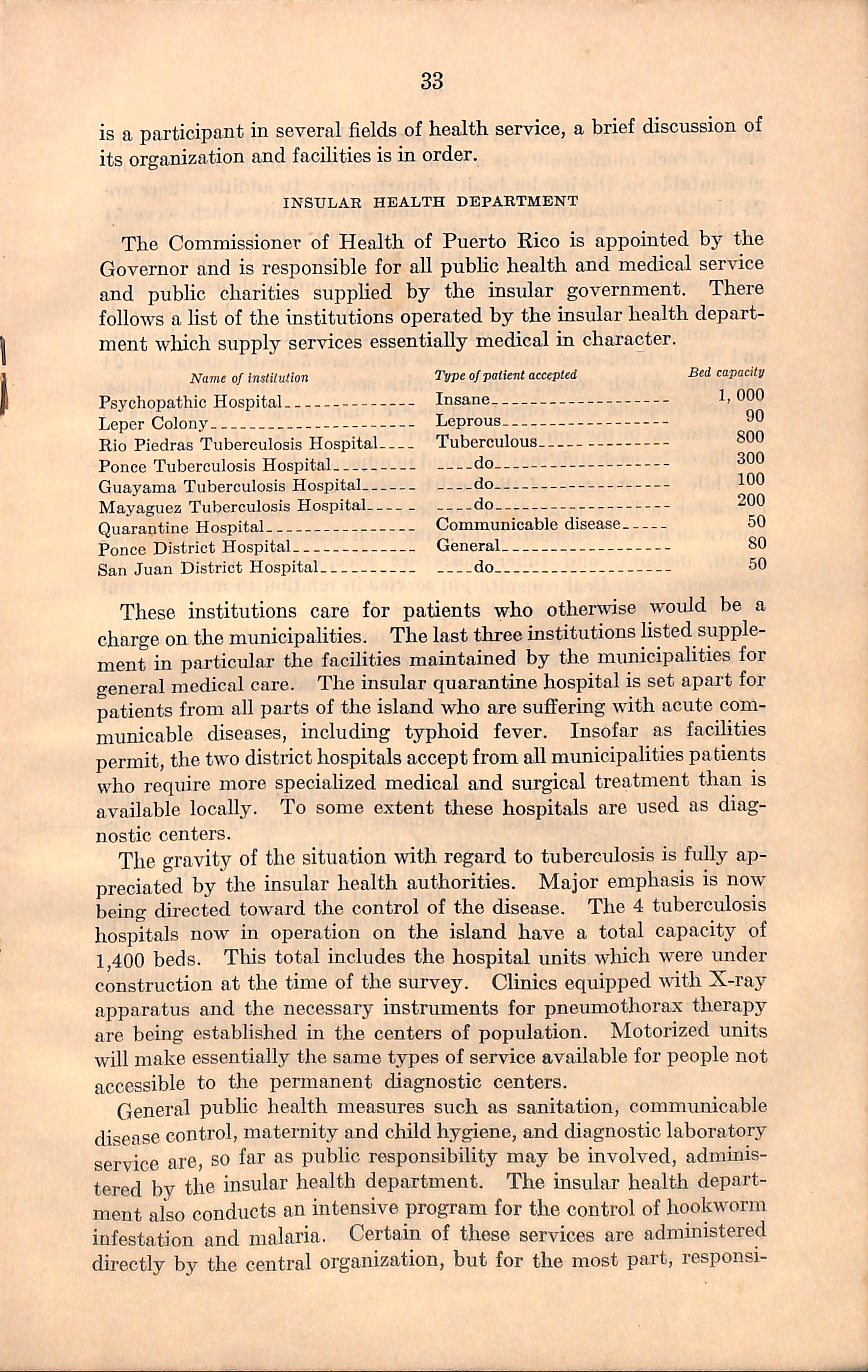

In the plan to be suggested later for improving hospital service in rural municipalities, the insular health department is to play a promi nent role. For this reason, and because the insular health department

is a participant in several fields of health service, a brief discussion of its organization and facilities is in order.

The Commissioner of Health of Puerto Rico is appointed by the Governor and is responsible for all public health and medical service and public charities supplied by the insular government. There follows a list of the institutions operated by the insular health depart ment which supply services essentially medical in character.

Name of instilution

Psychopathic Hospital

Leper Colony

Rio Piedras Tuberculosis Hospital

Type ofpatient accepted

90

Ponce Tuberculosis Hospital do 000

Guayama Tuberculosis Hospital do Mayaguez Tuberculosis Hospital do

Hospital

These institutions care for patients who otherwise would be a charge on the municipalities. The last three institutions listed supple ment in particular the facilities maintained by the municipalities for general medical care. The insular quarantine hospital is set apart for patients from all parts of the island who are suffering with acute com municable diseases, including typhoid fever. Insofar as facilities permit,the two district hospitals acceptfrom all municipalities patients who require more specialized medical and surgical treatment than is available locally. To some extent these hospitals are used as diag nostic centers.

The gravity of the situation with regard to tuberculosis is fully ap preciated by the insular health authorities. Major emphasis is now being directed toward the control of the disease. The 4 tuberculosis hospitals now in operation on the island have a total capacity of 1,400 beds. This total includes the hospital units which were under construction at the time of the survey. Chnics equipped with X-ray apparatus and the necessary instruments for pneumothorax therapy are being established in the centers of population. Motorized units will make essentially the same types of service available for people not accessible to the permanent diagnostic centers.

General public health measures such as sanitation, communicable disease control, maternity and child hygiene, and diagnostic laboratory service are, so far as public responsibility may be involved, adminis tered by the insular health department. The insular health depart ment also conducts an intensive program for the control of hookworm infestation and malaria. Certain of these services are administered directly by the central organization, but for the most part, responsi-

bility is discharged through local personnel. The minimum health staff of each municipahty is a sanitation officer who is paid by, and accountable to, the insular health department. In addition there are 24 health organizations known as public health units which serve 54 municipalities. The insular health department accepts major admin istrative and financial responsibility for these organizations, but in most cases there is some participation by the municipalities. Each of the 5 first-class municipahties has a health unit; 20 of the 23 secondclass municipahties are served by 14 health units and 6 sub-units; and in the third-class municipalities there are 5 health units and 24 sub-imits which render public health service to 29 municipalities. In most respects these organizations are comparable to county health departments of the continental United States. A list of the personnel employed by each unit may be found in appendix D.

While the program of the health units is primarily preventive in character, a large amount of medical service is rendered. Patients known to have or suspected of having such diseases as syphilis, hook worm, malaria, and tuberculosis are accepted for diagnosis and treatment. Medical consultation service in relation to maternal and child health may be obtained at special clinics.

From the foregoing discussion, it may be seen that the insular health department has certain clear-cut responsibilities in the broad field of medical care and that it has already taken definite steps to aid the municipals ties in the handling of particular problems relating to care of the sick.

Benejicencia municipal.—Care of the sick, exclusive of that furnished in the insular institutions, has remained very largely a municipal responsibihty. Public assistance of other types also devolves upon the municipalities under normal social and economic conditions. The law provides for common administration of medical care and material relief under what is known as "Beneficencia Municipal." The director of beneficencia usually is a physician who fills the dual position of municipal physician and director of municipal charities.

Table 13.—Total and per capita funds devoted to medical care and relief in first-, second-, and third-class municipalities of Puerto Rico during the fiscal year 1934

Expenditures for benedceneia

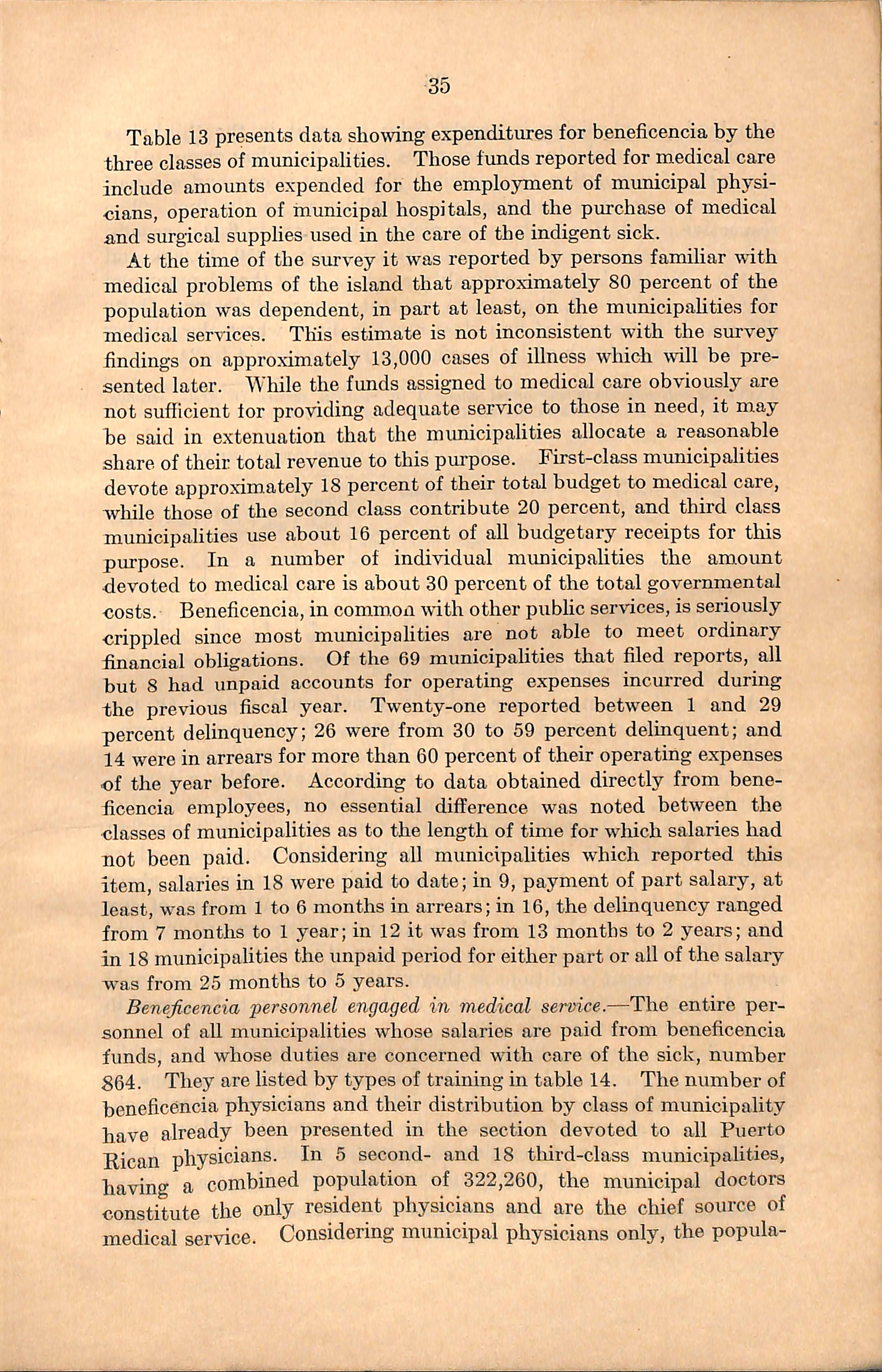

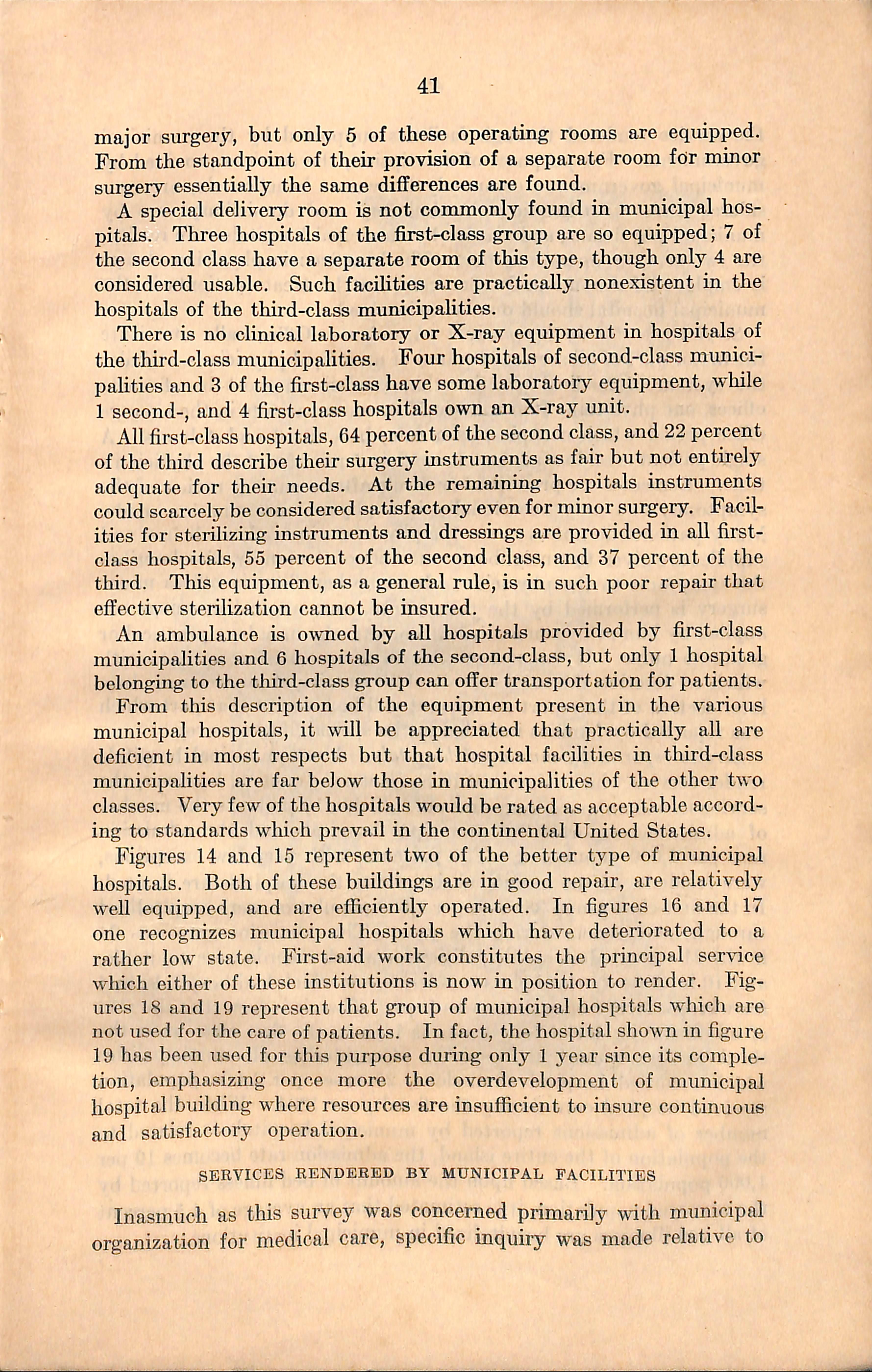

Table 13 presents data shomng expenditures for beneficencia by the three classes of municipalities. Those funds reported for medical care include amounts expended for the employment of mumcipal physi cians, operation of municipal hospitals, and the purchase of medical and surgical supphes used in the care of the indigent sick.

At the time of the survey it was reported by persons familiar with medical problems of the island that approximately 80 percent of the population was dependent, in part at least, on the municipalities for medical services. This estimate is not inconsistent with the survey findings on approximately 13,000 cases of illness which will be pre sented later. While the funds assigned to medical care obviously are not sufficient for providing adequate service to those in need, it may he said in extenuation that the mimicipalities allocate a reasonable share of their total revenue to this purpose. First-class municipalities devote approximately 18 percent of their total budget to medical care, while those of the second class contribute 20 percent, and third class municipalities use about 16 percent of all budgetary receipts for this purpose. In a number of individual municipalities the amount devoted to medical care is about 30 percent of the total governmental costs. Beneficencia,in commoii with other piibhc services,is seriously crippled since most municipahties are not able to meet ordinary financial obligations. Of the 69 municipalities that filed reports, all but 8 had unpaid accounts for operating expenses incurred during the previous fiscal year. Twenty-one reported between 1 and 29 percent delinquency; 26 were from 30 to 59 percent delinquent; and 14 were in arrears for more than 60 percent of their operating expenses of the year before. According to data obtained directly from bene ficencia employees, no essential difference was noted between the classes of municipalities as to the length of time for which salaries had not been paid. Considering all municipalities whicli reported this item, salaries in 18 were paid to date; in 9, payment of part salary, at least, was from 1 to 6 months in arrears;in 16, the delinquency ranged from 7 months to 1 year; in 12 it was from 13 months to 2 years; and in 18 municipalities the unpaid period for either part or all of the salary was from 25 months to 5 years.

Beneficencia personnel engaged in medical service.—The entire per sonnel of aU municipalities whose salaries are paid from beneficencia funds, and whose duties are concerned with care of the sick, number 864. They are listed by types of training in table 14. The number of beneficencia physicians and their distribution by class of municipality have already been presented in the section devoted to all Puerto Rican physicians. In 5 second- and 18 tliird-class municipalities, having a combined population of 322,260, the municipal doctors constitute the only resident physicians and are the chief source of medical service. Considering municipal physicians only, the popula-