STEAM DREAMS

See Britain from a vintage rail carriage

See Britain from a vintage rail carriage

So the shortest day came, and the year died And everywhere down the centuries of the snow-white world

Came people singing, dancing, To drive the dark away.

Susan Cooper, ‘The Shortest Day’

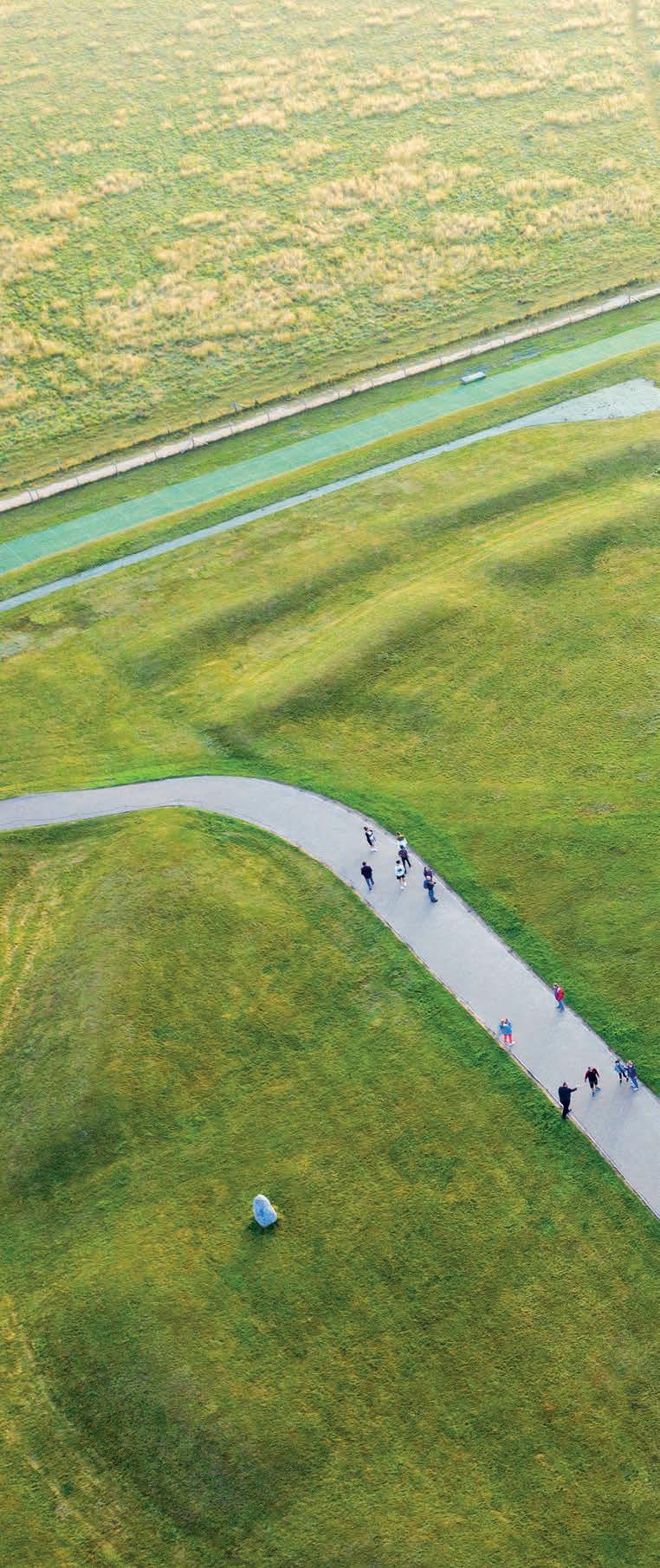

They came in darkness, a motley crowd some 4,500 strong, to windswept Salisbury Plain – young and old, punk, pagan, pilgrim, Druid, New Ager, eco-warrior, wiccan, shaman, sightseer… Some wore bobble hats, some antlers or mistletoe crowns. In a mood of anticipation, they waited as the sky turned from ink to powder blue to grey, and out of the shadows loomed the enigmatic stone colossi that exert such a pull on the imagination.

So, at 8.04am at Stonehenge, began 21 December 2024, the shortest day, the winter solstice, the pagans’ Yule. Drummers drummed, a hobby horse pranced, Morris men capered, yogis performed sun salutations… King Arthur Uther Pendragon, bearded and in full Druid regalia, conferred a knighthood on a young man. A harmony choir, a vision in scarlet, sang to honour the earth.

For pagans in particular, the winter solstice is more important than the summer solstice, since it is on this day that the sun is ‘reborn’ for the coming year – and no site holds so potent a spiritual power than Stonehenge, described by UNESCO as “the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world”.

As a curator for English Heritage, Dr Jennifer Wexler has responsibility for some 60 prehistoric sites. A specialist in archeological landscapes, she holds a Masters and PhD degree from University College London. Yet, for all the scientific rigour she brings to her work, she is as susceptible as anyone to the enchantment of such ancient rites. “I’ve been to three summer and two winter

Every December for the winter solstice, crowds gravitate to the ancient stones at Stonehenge, whose mystery has confounded and enchanted for centuries

WORDS ROSE SHEPHERD

Britain is blessed with more than 180 heritage lines and many other glorious rides too, as our writer found on a series of journeys covering more than 4,000 miles

WORDS TOM CHESSHYRE

Chugging down the five-and-a-halfmile Swanage Railway towards the coast in Dorset in southwest England, you are treated to perhaps the most awe-inspiring sight from any train in Britain, though that’s open to debate (there are so many). After your steam train slowly rattles along from Norden station, hissing, hooting and emitting great plumes of sulphur-smelling vapours, the jagged ruins of a classic medieval castle arise on a hillock to the right. You’re getting a close-up view of Corfe Castle, built by William the Conqueror in the 11th century, although it was previously the site of a residence where Edward the Martyr, the king of England, is believed to have been brutally assassinated aged 16 in AD 978.

Heritage trains and history all seem rolled into one here, and it’s even more enjoyable if you pay extra for a cab ride in the old locomotive pulling the carriages, so you can see the scenery emerging directly ahead. The driver will let you add coal to the furnace fuelling the loco, and pull the cable connected to the whistle, too.

The first passenger steam train sliding along the track of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, in northeast England, was on 27 September 1825, with Victorian rail pioneer George Stephenson at the controls, no less. The nation that invented

We delve into the fiery history of Britain’s biggest Bonfire Night celebration, which takes place in the unassuming Sussex town of Lewes

WORDS HENRIETTA EASTON

Anewcomer to Lewes would have a hard time believing that, once a year, this pretty town with its cobbled streets, higgledy-piggledy houses and cosy coffee shops transforms into the stage for Britain’s most dramatic and infamous Guy Fawkes Night celebration.

Tucked into a sweeping valley in the East Sussex South Downs, Lewes is home to a ruined medieval priory, a Norman castle and the Anne of Cleves House – gifted to her after her marriage to Henry VIII. The area was once a rural outpost of the Bloomsbury Group, and it’s also where revolutionary thinker Thomas Paine penned

The Rights of Man, a work that would go on to influence both the American and French Revolutions.

The world-famous Lewes Bonfire Night is just another string to the town’s historic bow. ‘Remember, remember the fifth of November’, as the children’s rhyme goes, and there’s no forgetting Bonfire Night in Lewes. Beyond the traditional bonfire and fireworks, the evening features an extraordinary torchlit procession with burning crosses, flaming barrels and effigies carried through the town’s narrow streets. Lewes’s celebration not only commemorates the Gunpowder Plot, but also honours 17 Protestant martyrs

from the town that were burned at the stake during the reign of Queen Mary I. Their execution site is marked today by a plaque outside the Lewes Council Building. Like bonfire nights across Britain, the origins of the celebration date back to 5 November 1605, when a failed Catholic plot to blow up King James I in Parliament was uncovered. Soon after, ‘An Acte for a publique Thanksgiving to Almighty God every year of the Fifth day of November’ was passed, which held that the day should be celebrated annually in perpetual remembrance of the plot. Across the country, church bells rang out followed by

services of thanksgiving and bonfires in the street to commemorate the 300 martyrs burned at the stake under Catholic rule.

But why does such a seemingly genteel town host such an unruly celebration? In Lewes, the burning of effigies began after the ‘Popish Plot’ in 1678: a fabricated conspiracy by priest Titus Oates, who falsely claimed that Catholics planned to assassinate King Charles II and overthrow the government. The lie gripped England in anti-Catholic hysteria for several years before Oates was finally rumbled and thrown in prison.

The first recorded Bonfire Night parade in Lewes took place on 5 November 1679, when young armed men carried images of the Pope, Guy Fawkes and other ‘enemies’ on long poles through the streets.

By 1832 the celebrations had become so unruly that police issued hundreds of prohibition notices. Blazing tar barrels were dragged through the timber-framed streets of Lewes’s affluent centre to make bonfires, threatening the lives and livelihood of the ruling classes. In 1847, London police forces were drafted in to control the Bonfire Boys.

When the Pope restored Catholic bishops in England in 1850, the Bonfire Boys responded with fury, burning effigies of the Pope once again alongside signs proclaiming

Those attending the event today experience many of the same traditions. Seventeen burning crosses are carried through the town and a wreath-laying ceremony takes place at the War Memorial. Ladies’ and men’s races to pull a flaming tar barrel thunder down Cliffe High Street, and a flaming barrel is thrown into the River Ouse to symbolise the throwing of the magistrates into the river after they had read the Riot Act to the Bonfire Boys in 1847.

What began as a dark and dangerous display of rebellion has evolved into a proud celebration of the town’s history

From the 1800s onwards, Lewes’s Bonfire Night took on an increasingly rebellious and political tone. Gangs nicknamed the Bonfire Boys used the annual celebration as an opportunity for civil disobedience and a rallying point to protest against authority. Many of them were disenfranchised soldiers who had returned from the Napoleonic Wars to poverty and hardship. Adopting striped smuggler’s jumpers as their uniform and darkening their faces to avoid recognition, they were inspired by political reformists like Thomas Paine. The Lewes bonfire societies still wear these striped jumpers to this day.

‘No Popery Here’. The same year, they marked the spot where the Lewes Martyrs were burned and marched through the town with burning crosses.

In 1853 the first two bonfire societies were established: the Cliffe Bonfire Society and what is now the Lewes Borough Bonfire Society. After years of trying to prevent the yearly riots, the authorities grudgingly accepted the annual chaos.

The festivities culminate in separate bonfire and fireworks displays run by the seven different societies. Effigies are still paraded through the streets before being burned. Each year these include Guy Fawkes, Pope Paul V –the Pope in 1605 – and any current ‘Enemies of Bonfire’. For safety reasons roads and rail lines into the town are closed at 3pm on 5 November; those wanting to join in from further afield can watch a livestream of the processions from the comfort of their sofa by tuning into Rocket FM on YouTube.

What began as a dark and dangerous display of rebellion has evolved into a proud and spectacular celebration of the town’s history and independent spirit. Perhaps most remarkable of all is that after a night of burning crosses, flaming barrels and cursing at enemies, the town transforms back into its charming, well-mannered self. That is, until the fire is lit again the next year.

On the edge of Britain, Orkney stands apart – a place of wild seas and ancient stones that carry the echoes of an extraordinary past

Discover scenic landscapes and timeless stories in one of England’s most enchanting rural regions

WORDS CAROLINE BUTTERWICK