MISSION: The Center for Photography at Woodstock provides an artistic home for contemporary photographers with programsin education, exhibition, publication, fellowships, ;nd services which create access to professional workspace, nourishing responses, and new audiences.

The Center acknowledgessupportfrom the New York Seate Council on the Arcs Visual Artists Program, the NYSCA ElectronicMedia & Film Programs, the National Endowment for the Arcs Visual Artists Organizations Program, and FilmNideo Arcs.

PHOTOGRAPHYQuarterly =62, Vol. 16 No. l, ISSN 0890 4639. Copyright© 1995 the Center for Photography at Woodstock, 59 Tinker Street, Woodstock, New York 12498. TEL: (914) 679-9957. FAX: (914) 6796337. All photographs and texts reproduced in this Quarterly are copyrighted by the artists. All rights reserved. No part of chis publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without wntten permission from the Center for Photography at Woodstock. The opinions and ideas expressed in this publication do not represent official positions of the Center.

Printing by Kenner Printing Co. Inc., New York City. Editing and design by Kathleen Kenyon. Text proofreading by Joan Munkacsi. Composition by Digital Design Studio, Kingston, New York.

The PHOTOGRAPHY Quarterly is distributed by Bernhard DeBoer, Inc., 113 East Centre Street, Nutley, New Jersey, 07110, and Desert Moon Periodicals, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS:

Sheva Fruitman, Susan Fowler-Gallagher, Rollin Hill, Kenro lzu, Colleen Kenyon, Ellen Levy,James Luciana, Tanya Marcuse, Elliott Meisel, Marc Miller, Joan Munkacsi, Jose Picayo, Lilo Raymond, Ken Shung, Alan Siegel, Tom Wolf.

STAFF: Executive Director, Colleen Kenyon; Associate Director, Kathleen Kenyon; Executive Assistant, Lawrence P.Lewis; Program Assistant, Steven West.

ADVISORY BOARD:

Norton Batkin, Ellen Carey, Philip Cavanaugh, Penelope Dixon, Susan Ferris, Cheryl Finley, Julie Galant & Martin Bondell, Beth Gates-Warren, Howard Greenherg, Sue Hartshorn, Bill Hunt, Greg Kandel, Peter Kenner, Laurie Kratochvil, Peter MacGill, Ann Morse, Sandra S. Phillips, J. Randall Plummer, Ernestine W. Ruben, Julie Saul, Susana Torruella-Leval.

FALL '94 ARTS ADMINISTRATION INTERNS: Kate Menconeri and Rachel Polaud (France).

SUMMER '94 WORKSHOP INTERNS: Kate Menconeri, Jojo Wemberg, and Steven West.

LIBRARIAN: John Dydo.

SUBSCRIBE:

To receive the PHOTOGRAPHY Quarterly, become a SubscribingMember. U.S.A. $25 annual fee. / Canada & Mexico $40 / International $45. Memberships are tax deductible to the extent of the law. The Center is a 501 (c)(3) charity.

PHOTOGRAPHY Quarterly single issue: U.S.A. $7 donation/ $9 postpaid. International / Canada /Mexico/ $12 postpaid.

FRONT COVER: © Debbie Fleming Caffery, Pine Needle Fire, December 1988

The Center's Permanent Print Collection of over six hundred photographs has been assembled since 1980 through the generous gifts of artists and individual donors. le includes three segments: strong holdings in contemporary work by visual artists of exceptional talent; a collection of historical images by Woodstock photographers; and an archive of the 1969 and I 994 Woodstock Festivals. The collection is open to the public by appointment with the Associate Director. The collection serves as a study resource for artists, teachers, students, and curators. Three traveling shows -Selections from the Collection -are available for travel: The Interior & Exterior World, The FamilyofMan, Woman, &Child, and Photographic Technology I The Other Side of Black-&-White. Please call 914-679-9957 if you are interested in hosting one of the exhibitions or viewing the archive.

Recent Additions to the Collection:

Mark Abihayo, Feathers; Helene Belanger, Body Fragment; Martin Benjamin, Statue of Buddy Holly; Charlie Carter, Mts. Come Out of the Sky and They Stand There with Three Floating Feathers; Margaret Casella, Paper Ribbon; Robert Clayton, Old House; and Tree with Flowers; Maryjean Viano Crowe, Visions Danced in Her Head; Richard Edelman, La Swola San Maro, Venice; Susan Fowler-

Gallagher, Hudson River from Vanderbilt Estate; and Nine Untitled Prints; Michael Frederick,Woodstock Rock Festival; Sidney Gottlieb, Reeds in Ice; David Heberlein, Carriage Farms Development Minnesota; George Holz, Teresa; Kathryn Hunter, Northern Arizona; Karen luppa, Cocooned Girl; Patricia Kay, Waipahu Street; Kathleen King, Untitled; Manuel Komroff, Atomic Rose; The Park Suite; and Untitled; Antonin Kratochvil, Funeral in Moscow; Poland; Pollution; and Romania; Eric Lindbloom, Benmarl Vineyard; Luis Mallo, Untitled Diptych; Tanya Marcuse, Untitled; Arezoo Moseni, Untitled; Thomas Payne, Resistors series; Jose Picayo, Untitled; Lilo Raymond, Angel; Untitled; and Untitled; Patricia Richards, Plansettes & Thunderbirds; Harold Roth, Williamsburgh Bridge; Joan Rough, Flight #1; Janet Russek, Venice, Italy; Shelley Rusten, Rural Considerations; David Scheinbaum, Untitled; Philip Schwiclers, Torst Lieons; Lorna Simpson, Wish Box 1,2,3 "III", (Donated by Peter Norton); Len Speir, Hooded Figure; Franjo Tholen, The Pencil of Nature No. 2, (Donated by Kathleen Kenyon); Lucille Khornak, Entangled; Jim Vecchi, Untitled; Susan Wides, Model Citizens; Mike Wilson, Untitled.

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Gift of Course

ln,trodu,ction

The Po-..ver of Grace pict;u,re selection by Kathleen Kenyon

Noted Books & Opportunity Knocks Kate Menconeri '1

/...,,an,dscape .For a Neu; Mille,-,,-,--,,iu,rn., Derek Johnston

Landscape Photography at the End

2

Kathleen Kenyon,CPW Associate Director.Portfolio Reviews, Fotofest, Houston, Texas, November 1994 (photo credit: Ben Caswell)

Luis Valdovino, Work in Progress, 1990, video still from Hybrid Identities, video exibition curated by Mona Jimenez (in conjunction with the Center's travelingshow Fire Without Gold)

3

&

4

1 a

7

22

Ellen Handy

.Jt's time to travel.

Twelve photographers show the way to power and grace.

Derek Johnston asks:

Has the path on which landscape photographers tread reached an end or a turning point?

Ellen Handy answers:

Show us the way to the new millennium.

To follow the Center's "family" you'll need a guidebook and a map. Our excursions include:

Spring 1994 arts interns Cherie Lane and JoJo Weinberg arrive.

1994 summer workshop interns Kate Menconeri, JoJo Weinberg, and Steven West come to Woodstock.

Fall arts administrative intern Rachel Polaud comes from (and returns) to France; Kate and Steve stay on. JoJo goes West.

Now we welcome the winter 1995 arts administration interns: Judi Esmond, Heidi Woldt, and Barbara Strnad.

Colleen Kenyon, the Executive Director, goes on an expedition to Long Island for Common Ground, Trends and Visions sponsored by the Alliance of New York State Arts Councils/the New York Foundation for the Arts.

My journey includes a week-long trip to Houston where it was a delight to review portfolios including those of Center members.

The two of us go to Yaddo for a March Artist-In-Residence. You will (won't) be able to find us in Saratoga Springs.

Derek Johnston makes a passage to Colorado for an eight month Artist-In-Residence. Steven West moves into his place. Derek loops back for the Workshop season (our 17th!).

Larry Lewis journeys to Poughkeepsie, New York, to teach at Marist College twice every week.

Steven West jaunts to photograph in New York City one weekend day.

At Photo Expo in New York City, Larry, Steven, Rachel and Kate, (with the Center member Mark Jargow at the helm), hosted the Center's booth. Hundreds of photographers collected our education and membership brochures.

Center exhibitions travel too. Fire Without Gold, co-curated by Miriam Romais and Christine Jackson, with a video exhibit, Hybrid Identities, assembled by Mona Jimenez, was shown here from October 15 to December 20, 1994. The shows next appear at the Walters Hall Gallery, Rutgers University, in New Brunswick, New Jersey (JanuaryFebruary 1995).

Selections from the Permanent Collection continually circulates. Now it's at home at The Bears down the road from us.

Woodstock Photography Workshop visiting artists soon will be here (and everywhere):

Jane Evelyn Atwood, Debbie Fleming Caffery (who'll teach in Lousiana), A.O. Coleman, Larry Fink, Lynn Goldsmith, Connie Imboden, Len Jenshel, Colleen Kenyon, Kathleen Kenyon, Robert Glenn Ketchum, Lucille Khornak, Antonin Kratochvil (he'll take his students to Eastern Europe), Eric Krieger, Ken Lassiter, Eric Lindbloom, Ann Lovett, Jim Luciana, Marie Claire Montanari, Frank Ockenfels 3 , Jose Orraca, John Placko, Eugene Richards, Ernestine Ruben, Jane Tuckerman (she'll lead her class in Mexico), Steven West.

Wherever you roam, we hope you carry "the Center" in your heart. -© 1995 Kathleen Kenyon, editor

Kate Menconeri (self portrait)

At rimes there exists a balance and harmony, an irnuilive connection of all things that stirs the spirit w create. At times chere is sublime meaning and magic. It lies wi1hin humanity, communications,learning;,ha, sparkof discoverywhen all ,ha, infonnation circlingwild in one's mind larcheson w mauer and rakesshapein vision and undersranding.This is the essenceof light, the breath of imagination.Each of the artim, ceachers, students,and situationshave, in eclecticways, contributedcothis processof discovery.Home base is Boston; Kate attended SUC Albany and now lives in Clinton Corners, New York.

JoJo Weinberg (photo: Steven West)

The Center for Phowgraphyis a powerfulresource.I, has providedme with the nourishmentnecessarylO confinn my status as a fine an phowgrapher.The insight I gainedas a workshop inrem hasmadeenteringthefieldof phowgraphya lessintimidating experience.Coming from Connecticut, Jojo attended SUNC New Paltz. She currently lives in New Mexico.

Steven West (self portrait)

When I was informed,ha, I would have ,he oppommi<)'w serveasan intern in CPW's workshopprogramI consideredmyself lucky. However, the acrnal experience surpassed all my expectations. It was an educariontechnically, anisticall)', and personally,beyondanythingI had ever known-pretty lucky a, that. Originally from Brooklyn, New York, Steven lives in Lake Hill, New York and studied at SUC New Paltz.

3

CHARLIE CARTER

MARYJEAN VIANO CROWE

JESSECA FERGUSON

TARA FRACALOSSI

SHAUNA FRISCHKORN

JENNIFER KOTTER

POWER Nouns-1, potence, potency, potentiality; might, force; ENERGY;ascendancy, ascendency, sway control; almightiness, omnipotence; AUTHORITY, STRENGTH. 2, ability; ableness; competency; efficiency, efficacy; validity, cogency; enablement; vantage ground; INFLUENCE; capability, MEANS, capacity; faculty, quality, attribute, endowment, virtue, gift, property, qualification. 3, pressure, elasticity; gravity, electricity, magnetism, electromagnetism; ATTRACTION; living force; ENERGY, FRICTION. 4, engine, motor, dynamo, generator; combustion, jet, rocket. Verbs-1, be powerful; be able; can; sway, control; compel. 2, strengthen, fortify, harden; empower, enable, invest, endue, arm, reinforce. 3, invigorate, energize, stimulate, kindle, refresh, restore. Adjectives-1, powerful, potent, potential; capable, able; equal to, up to; cogent, valid; effective, adequate; competent, STRONG, omnipotent; 11-powerf, , almightyr ~ectric, magneti ; ractive; energ Ile, forcible, o(ceful, incisive, trencha t, electrif~fg; influential; productive. 2, resistless, irresistible; 1 vincible, indomitable, i vulnera 7'impregnable, unconEJueFale; oveq:lOwering, overwhelming. Adverbs-powerfwlly, strongly, irresi ti ly, etc. GRACE a. & v.---n elicacy, tact, culture· graciousnes , courtesy; attractivene s, charm; compassion, mercy; saintless, PIETY, sinlessness.-v. honor, decorate; improv&. See BEAUTY, TASTE.BE AU TY Nouns-1, beauty, the beautiful, loveliness, attractiveness; form, elegance, grace, charm, beauty unadorned; symmetry; comeliness, fairness, polish, style, gloss; good looks. 2, bloom, brilliancy, radiance, splendor, gorgeousness, magnificence; grandeur, glory; delicacy, refinement, elegance. 3, Venus, Hebe, the Graces, goddess; witch, enchantress; charmer, reigning beauty, belle; Adonis, Narcissus. Colloq., eyeful, picture, dream, stunner, peach, knockout, raving beauty, good-looker. 4, beautifying; make-up, cosmetics; decoration, adornment, embellishment, ORNAMENTATION. Adjectives-1, beautiful, beauteous; handsome; pretty, lovely, graceful, elegant; delicate, dainty, refined; fair, personable, comely, seemly; bonny, good""l0oking; well-favored, wellmade, well-formed, well-proportioned; proper, shapely; SY.• m rical, regular, harmonious, sightly. Colloq., easy on the eyes, nifty, stunning, devastati g. 2, brilliant, shining; splendid, resplendent, dazzling, glowing; glossy, sleek· rich, go geous, superb, magnificent, grand, fine, sublime. 3, artistic, aesthetic; picturesqQwe 1-'composed,well-grouped; enchanting, attractive, becoming, ornamental; unde orm~d, u defaled, unspotted; spotless, immaculate; PERFECT, flawless. T A ST E No ns-:1, good taste, cultivated taste; delicacy, refinement, tact, finesse; nicety, DISCRIMI ATION; polish, ELEGANCE; grace, virtue; connoisseurship, fine art; culture, cultivation, fastidiousness; aesthetics. 2, taste, flavor, gusto, savor. 3, savoriness, tastinessAiweetness, sourness, acidity, acerbity; PUNGENCY. 4, seasoning, CONDIMENT; spice, relish; tidbit, dainty, delicacy, morsel, ambrosia, nectar. 5, of taste, connoisseur; epicure, gourmet; judge, critic, virtuoso. Verbs-1, have good taste, appreciate; judge, criticize, discriminate, distinguish, particularize; single out, draw the line, sift, estimate, weigh, consider, diagnose; pick and choose. 2, savor, taste, sample; relish, like, enjoy; tickle the palate. Adjectives-1, in good taste; unaffected, pure, chaste, classical, cultivated, refined; nice, delicate, elegant; fastidious, discriminative, discerning, perceptive; to one's taste, after one's fancy. 2, tasty, flavorful, strong. Adverbs-tastefully, elegantly; purely, aesthetically, etc.

Pict~lection by Kathleen Kenyon

4

GAIL LEBOFF

RICHARD LOPEZ.JR LUIS MALLO POLLY STEINMETZ OSCAR VAL VERDE MIKI WARNER

What is the weight of gravity on a descending scale?, I 994, silver print, l0 5/sx9"

Charlie Carter (Meridian, ID) (no statement)

5

Mary jean Viano Crowe (N. Easton, MA) I am sitting at the kitchen table watching my mother construct a cake for my birthday party. A small vinyl doll is placed in the hollowed-out center of two round layer cakes piled atop each other, secured with a slathering of frosting. It is sometime in the 1950s and my mother is happy, content at this fanciful task of inventing a doll cake, a dream girl, for my delight. My cake evolves. Her vanilla frosting gown, through the magic of food coloring, metamorphasizes into a palette of colorful swirls, complete with frosting flowerets. Later, my girlfriends and I will eat this cake, slicing away at her piece by piece, deconstructing her colorful skirt to literally feed upon it. But for now she is safe, beautiful, and insulated within the folds of her confectionery cocoon. I watch as my mother transforms this dime store doll, transporting her and me to another world. And when she is done I am eager to lick the frosting from the bowl, happy to consume the dream.

The Bake Off, image from the series All-Consuming Myths, silver prints and mixed media, 1994, 73x74" 6

Doll Cake 6A: Visions Danced in Her Head, I 994

Jesseca Ferguson (Boston, MA) My work with pinhole photography and natural light is about time. Lengthy exposures (an hour or more), the stillness of a skull found long ago, the arrangement of objects whose history I know-all these elements figure in my images. The syntax of the time-stained print (invoked by the use of hand-applied nineteenth century emulsions) serves as a further metaphor for the passage of time. Loss, dissolution, decay, that which is forgotten, and that which is remembered, that which falls away, and that which remains: these are my concerns. As Czeslaw Milosz has written: It is true, we have a beautiful time as long as time is time at all.

PearlStickNrue/Box, (for F.W.) 1993, pinhole cyanotype, 10x8"

gg Cup, 199 l

Skull/\',,"/!

7

Tara Fracalossi (Albany, NY) For the past few years I have culled images from religious (specifically Catholic and Russian Orthodox) iconography: Victorian death memorabilia and vintage stories of early Christian martyrs who have achieved a state of grace. I seek to explore how ritual, iconography, and organized spirituality build our notions of self-both the physical and the social.

Untitled (pair), 1992, silver with wax, organza and grommets, 63x5x 10"

8

C.mJlc,tock, I 99l, 24 pages, (open)

Shauna Frischkorn (Jamestown, NY) I explore the sensuality and visual beauty of the human face: the fullness of a mouth, the pattern in a hair line, the texture of a cheek. Even a portion of the face is so expressive that it renders the subject's spirituality. By working up-close with my subjects, the pictures convey universal human emotions. These feelings are an expression of human grace as seen in abstract yet intimate portraits. The technique used to create these images is the gum bichromate process. Contemporary artists are rediscovering what the Pictorialists knew in the late 1800s: the gum process distinguishes itself as a medium that is expressive, sensual, and tactile in subtle ways that the silver gelatin print can not be. Gum printing slows down the artist to think about the work and how colors will affect the image; therefore, the printing process itself becomes a creative extension of the portrait.

Untitled, 1994 gum bichromate on paper, 13'/,x 9 1/z"

Untitled, 1994

9

•

•

pumps not iron but irony and ironing

• It's yearning to be Rita

• The tool box confesses in its head shots • It's deepest desire to be a star of the Silver Screen • Even at the price of no life outside The Pictures

Image from the series Hardware, silver print, 40x30", 1989-1990

Jennifer Kotter (New York, NY) The battle ax dripping with lace and pearls flashes her blade

The bride stripped bare reveals her Victoria's Secret

The claw hammer struts her aspirations to finery• The work force muscle

Hayworth in negligee

10 Hardware, I 989- I 990

NY) I am concerned with gesture, form, and simplicity. It is important to me that my work be purely visual. I want the viewer to be captivated by the feeling in the image. For the past few years I have been creating a bird and flower series but most recently I have been making solarized Flower Portraits. In this work, I photograph fake and dead flowers at the seashore then manipulate the images in the darkroom, striving to bring them to life. The metamorphosis of make-believe into gestures of nature is at the work's core.

Untitled, from Bird & Flmver series, 1992

Gail Leboff (New York,

11

Untitled, from the FlowerPorrrai, series, 1994, framed Cibachrome, 56x35 1/z"

Richard Lopez, Jr_ (Bellerose, NY) I explore the concept of patriarchy and its legacy of oppression of the weak and the helpless in our culture. My own personal experience of the brutalizing effects of childhood sexual, physical, emotional, and spiritual abuse are a "microcosm of the crisis of abuse that afflicts our society and its most valued institutions: the family and the faith community." The portraits of children imply much more than is first seen. Each photograph is a celebration of the dignity and preciousness of childhood and a challenge to recognize the acts of violence committed against these most sacred. The images serve as a call to those who choose to ignore or deny the fact that some 3,000,000 children are the victims of abuse and neglect each year in the United States.

Britt: Age 9 Months, 1993, silver print, 5 1/.x3 3/,"

12 l?.f--,. • ... , i, :}"\ J.'t: .·.

Portrait of an Abused Child, 1991

Luis Mallo (Brooklyn, NY) The classical representation of the human form eternalizes the beauty and freedom of erotic expression. In Plato's The Banquet, Socrates concludes the famous symposium by transforming Eros into a philosophical ideal. Modern psycho-analytical theory, in contrast, has reinterpreted Eros as the instinctual force which seeks to unite individuals in bonds essential to the development of civilized societies. Freud referred to this force as the life instinct, which is constantly antagonized by the destructive impulse under the service of the death instinct, its counterpart. The struggle between these two principal instincts is made modern through the arrangement and juxtaposition of specific elements in the triptychs. The images are descriptive of our intellectual and technological abilities. They are symbolic, representing intricate mental processes which have created and continue to sustain civilization. The anxiety created from these internal debates causes what may be the most disturbing conflict of our existence.

13

Untitled, two triptychs from Erosand Civilizarionseries, 1993-94, sensitized steel and copper plates, each l8x36"

Polly Steinmetz (San

CA) Religious symbols are rich in sensuality and passion. I have no background in any religious belief, but I am curious and consider myself a wanderer among various cultural and spiritual icons. What is their visual power over the human spirit? I am involved in an authentic reaching out for the sources of lost myths. Luckily I can combine this search with a love affair of image-making.

Rafael,

a

a

14

Roman Reliquary, 1994, silver mural, purple velvet wood base, 8x4

1 • (detail of a photographic mural,

part of

larger mixed media installation)

1994

Han~in~ Christ,

Va I

or

is a work piece in five sections set to a poem by Richard Dehmel. The inspiration was first realized by Arnold Schoenberg's arrangement for string orchestra, an atmospheric, dark, and moody account of two lovers walking on a cold moonlit night. "I am carrying a child and not by you. I am walking here with you in a state of sin." Five distinct images reflect the transitional states. Agitation in the second movement follows close to the musical composition. The presence of the moon throughout the poem shows its radiant glow in the final movement to a serene coda.

"Irun,{igurcd N,ght V, I 994

Oscar

Verde (San Francisco, CA) Transfigured Night

Verklarte Nacht

15

Transfigured Night II, 1994, silver print, 10x8"

Miki Warner (Malibu, CA) I walk several miles daily in an area close to my home. As I walk I collect, a few at a time, plants that have a line, shape, or character appealing to me. Walking is a series of over forty images of plants, flowers, and leaves photographed with a pinhole camera, in studio, during the spring and early summer of 1993. I use the edge of the film as an extension of the image in order to imply movement. The work is meant to be seen as a series, creating rhythms that are similar to the act of walking. The isolation of the objects reflects, in some ways, my feelings about my own place in the world.

from

16 Untitled, 1993

Untitled,

the Walkingseries, 1993, silver print, 10x8"

OPPORTUNITYKNOCKS I PROFESSIONALSERVICES

The Center for Photography at Woodstock offers two types of internships: Workshop and Arts Administration. Call: 914-679-9957.

Artists Welfare Fund/New York Artists Equity Association assists visual artists, including film and video makers, with interest-free loans of up to $2,000 intended primarily for health related emergencies. Write: 498 Broome St., New York, NY I00 I 3. Tel: (212) 941-0130.

Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts administers two to six month residencies including studio, livingaccommodations, and small monthly stipend. For application send SASEto: Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, 724 South 12th St., Omaha, NE,,-68102.Tel:(402) 341-7130, Fax: (402) 341-9791.

Blue Sky Galll:!ryreviews work for exhibitions. Send twenty slides with SASE to the gallery, 1231 NW Hoyt, Dept.AF, Portland, OR 97219.

CEPA reviews proposals, slides, and portfolios by visual artists for exhibition on an ongoing basis. Submit representative slides, statement about the work, resume, and SASEto: Exhibitions Curator, CEPA,700 Main Street, 4th floor, Buffalo, NY 14202.Tel:(716) 856;2717.

Craft Emergen,s:y eliefFund (C!;l\E) provides interest free loans to professional craftspeople suffering career threatening em. ies sot as fire, theft, illness, an1r?atural djsaster; notification within one of application.Write: CERF,245 Mair;;;t., Northhampton, MA 0 I060. Tel: (413) 586-5898.

Critical Neecls Fund for Photographers with AIDS, prov sistance. Initial requests by phone:Tel: (212) 929-7190.

Department of Art, California State University Long Beach c ork that critically examines the ramifications of guns and violence in our sqciety. R,roand anti-gun work will be considered. Deadline: July I, 1995. For mor~ infonnadon call: BillLavenat (415) 647-9432 or Nancy Floyd at (714) 581-1239.

li;>upontVisitingArtists Fellowship awards one four-month semester facultyiq-residence position for photographers of color. Fellowship:$15,000. For information contact: Dupont Fellowship,The Art Institute of Boston, 700 Beacon St., B:\ton, ~A 02215. Tel: (617) 262-1223.

Fin!g.A,.rt\Work Center in Provincetown grants visual arts feUowshigsand resid~cies for writers and visual artists. Seven month fellowship each/ear in form of Ii d work space and modest monthly stipend. Oc~;f - MaQ'I,annual Feb. dea lltain application by mailingSASEto: Fine Arts Work Center, Box 565, Provin~own~MA 02657.

Money for Wof.!1eOgives •g to. $1,000 in smal grants for orth American artists whose work•,addresses women's issues. Awards also available to an outstanding lesbian artis~d,a(! confronting racism. For application send SASEto: Money for Women, Barbara Demig Memorial Fund, Box 40-1043, Brooklyn, NY 11240-1043.

MTA Arts for Transit offers two lightbox displays for photography in Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station, available for periods of two to four months each. For more information and guidelines send SASEto: Mona Chen, MTAArts for Transit, 347 Madison Ave., New York, NY I0017.

The National Arts Placement Affirmative Action Arts Newsletter contains career opportunities in the arts. (703) 860-8000.

Pollack Krasner Foundation assists visual artists of recognizable merit and financial need. For guidelines write: Pollack Krasner Foundation, 725 Park Ave., New York, NY I0021.

Transforming Our World, Ourselves: Peace by Peace, and 50 Years, Human Re-Visions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seeking submissions for ongoing series of exhibits, programs, publications, and public art projects. Send SASE for guidelines to: The Peace Museum, 350 West Ontario St., Chicago, IL 60610. Tel: (312) 940-1860.

Whitney Museum of American Art offers an independent study in studio art, curatorial, and critical theory. For an application write: Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, 384 Broadway,4th floor, New York, NY I00 I 3.Tel:(212) 431-1737.

NOTED BOOKS

TheCenter'sLibraryis open,free,fromnoonto5 p.m. Recentdonationsarelistedbelow. BRUSHFIRESINTHESOCIALLANDSCAPE:DavidWojnarowicz,ApertureFoundation.1994. ENTREDEUX,PoemesPierreBorhan,photographiesErnestineRuben,Paris,Audiovisuel.1987. ERNESTINERUBEN - PHOTOGRAPHS:FormsandFeelings,EditionStemmle,Schaffhausen, Germany,j989. HARMSWAY;Lust&madness,murder&mayhem,editedbyJoel-PeterWitkin, Twin.PalmsPublishers,1994.THEINTUITIVEEYE:Photographsfromthe DavidC. & Sarajean RuttenbergCollection,essaysby ColinWesterbeckand KathleenLamb,the ArtInstituteof Chicago,1991.RADIANTIDENTITIES:PhotographsbyJockSturges,introductionbyElizabethBeverly, afterwordby A.O.Coleman,ApertureFoundation,1994.SEASONSOFTHEWILD:A Journey ThroughOurNationalWildlifeRefugeswithJohnandKarenHollingsworth,WormPress.LENI RIEFENSTAHL:AMemoir,St. Martin'sPress,NewYork.1987.TRAVELER'SGUIDETOMUSEUM ARTEXHIBITIONS,SusanS. Rappaport,ed.,MuseumGuidePublications,1994.AMERICANPROSPECTS:PhotographsbyJoelSternfeld,PrefacebyAndyGrundberg,the Friendsof Photography, 1994.ANGELSATTHEARNO:PhotographsbyEricLindbloom,DavidR. Godine,1994.ATEN YEARRETROSPECTIVE,FocalPointGallery,1984.THEBIRTHOFACENTURY:Photographsby WilliamHenryJackson,St. Martin'sPress,1994.ROBERTCAPA:ABiography,RichardWhelan, Universityof NebraskaPress, 1994.COOKIEMUELLER by NanGoldin,Pace MacGillGallery, 1991.A DREAMOFENGLAND:Landscape,PhotographyandtheTourist'sImagination,John Taylor,St. Martin'sPress. EXCURSIONSALONGTHENILE:ThePholographicDiscoveryof AncientEgypt,essay by KathleenStewartHowe,Santa BarbaraMuseumof Art,1994. FEMALE TROUBLE by BettinaRheims,Schirmer/Masi,1991.FLESH & BLOOD:Photographers'Images of TheirOwnFamilies,PictureProject,1992.RAOULHAUSMANN:1886-1971,DerDeutsche SpiesserArgertSich,MuseumfurModerneKunst,PhotographieundArchitekturimMartin-GropiusBau,Berlin.MATTMAHURIN:PhotographsbyMattMahurin,editedbyMayalshiwataandTheresa Linsotti,RAM,Tokyo,Japan,1993.NATIONALGEOGRAPHICTHEPHOTOGRAPHS,photographs byLeahBendavid-Val,NationalGeographicSociety,1994.PORTRAITOFNEPAL byKevinBubriski, introductionbyArthurOIiman,ChronicleBooks,1993.PROVENCE:PhotographsbySonjaBullaty andAngeloLomeo,textby Marie-AngeGuillaume,AbbevillePress,1993.

IMAGINING FAMILIES:Imagesand VoicePhotographsbyFifteen Photographers, the National African American Museum at the Smithsonian Institution, 1994.

The other night I lay dreaming:I was alone wanderingin a cluster of second story apartments. Boxesof letters, photos, and scrapbookmemorabiliawere tucked away in each, awaiting my foreign hands, my sight, and my detached memory.And just as I reached up to grab one, a lifestory,a glimpseat the intimate, the owner came bounding into the room, freezingmy reach and thwarting my uninvited curiosity.The intriguing aspect of my dream was the fact that I did not know any of the people whose memories wereconcealed in those boxes.My motive was simplyto exploreanother's reality.

Almost everyone I know has spent hours musingover familyphoto albums.On one level familyphotographsserve to document the flesh, and a temporal union of people, on another they tell a story,disclosepersonal thoughts, and reveal familial relations, gender roles, values, and powerstructures.Fine art photographyalso has the quality of challenging one's perceptions of realities and the real. It can both lead and mislead. Interestinglyenough after my dream, I came upon ImaginingFamilies:Imagesand Voices, a book on the inauguralexhibition of the National African American Museum,created and curated by Deborah Willis.The collection featuresfifteen artists and their visions, re-visions,and perceptionsof"family,"commencingwith their own.

While all of the artistsfeaturedemployphotographyin someway,it is almost metaphorical that they should also paint, collage,write, and project slideson their installations. The artistic processesrevealedin this collection parallel in some waysideassuch as the "self' does not exist in isolation,and the familydoes not existoutsideof a community.LorieNovak, for instance,workswith literal slide projectionsover imagesof family, confronting societal projections and messages that L:thel,stereotype, and undermine our perceptionsof self.FayFairbrotherprints old negativesonto handmadequilts. This processsymbolizesbirth and death. Accordingto Fairbrother,those killed by their masters in KKKgroupswere wrappedand buried inside a quilt.

Beyondsharing a memory,these artists effectivelyconfront and challenge destructive stereotypes,racist ideology,and sexismby examining the roles and relationships within the family.Simultaneously,by deconstructing social structures and oppressive ideologiesone can begin to come to terms with the self. Much of the work focuseson ritual, symbolism,and emotionaljourneys.It is an extremelypoignantcollection of images and stories, pregnant with all the intimacy I had hoped to discover within those boxes in my dream. More, it critically examines the social forces and ideologiesthat obstructdeeper understanding.LornaSimpsonillustratesin her piece, "Coiffure,"that it is an understandingthat can only be affordedby being on the insideof a mask.

The common thread in all of these imagesand installationsis an artist who reveals and exposesthe self to the greater public in order to reach some kind of shared, collective understanding of our dual roles as kin and stranger. It is said that to successfully create-in any art form-inspiration must come from the core of one's soul. This leads straight to the family,familysignifyingblood, birth, and/or love, ancestry,and identity. It is illuminatingto see how art is used to promote healing in this collection of workand as a "socialbasisfor art": understandingone another-ethos-the Latin word for other which ironicallyalso means self-KM

EDITOR - KATEMENCDNERI

J l ol(

17

l a n d s C

Landscape art has developed beyond indulging in the expression of one's admiration of the natural world. It now envelops the relationships artists, people, and cultures have with the environment. Today's landscape is fragile and on the brink of irreparable damage. Contemporary artists are confronted with complex issues, from overpopulation to ozone depletion. The history of humanity is a chronicle of society's separation from nature and our desire to exercise control over wild things. Making beautiful photographs of the natural world is no longer a sufficient practice, even though it continues to be a necessary ritual for many photographers. Let us not continue to make art that perpetuates a romantic idealization of the landscape, art that in today's culture functions only as myth. We need to show the sources of environmental problems, not distort people's perception with a barrage of pristine land-

scapes. Today's landscape artists must address the issues confronting our culture and its environment, speak to the audience about the propositions we face, aid them in establishing better relationships with the land, and ultimately create work that functions as solutions to the problems.

The discovery of the New World introduced Europeans to a land so sublime that it forced artists to reconsider the aesthetic qualities oflandscape. Europeans came to the New World with the perception of wilderness as a wasteland harboring all sorts of unknown horrors. Unlike the mapped, isolated wilderness of home, the New World was uncharted, boundless, and incomprehensible. This new earth was the epitome of untouched nature; a true wilderness. Though the explorers and early white settlers of the New World were confronted with the raw realities of the primeval forest, the intellectuals, including

artists, freely romanticized this new landscape. Inspiration was found in the solitude of the deep, endless forests, on supreme mountain tops that reached straight to the heavens, and through unreal property seemingly carved by the hand of God. So vast and splendid was this land that the first European artists to use it as a subject depicted it as a possession of the divine. The Hudson River School of painters, the earliest organized group of American landscape painting, are known for their spiritual connections with and beliefs in the intrinsic values of the natural world. Because of their inability to comprehend a relationship with such an astounding presence, artists saw only nature's majesty.

Exploration of the West brought back stories of an improbable landscape. After the Civil War, as a part of a series of government-supported surveys, photogra-

a p e fo r

David Mussina, Panorama of the G,-and Canyon, 1992

18 a n e w

Lukas Felzmann, Muse and Restraint, 1992, (installation at the Friends of Photography, CA)

Lukas Felzmann, Day Dreaming, 1994

m l l

phers such as Timothy O'Sullivan and William Henry Jackson were commissioned by the government to go to places like Yellowstone, the Colorado Rockies, the desert Southwest, and the Sierra Nevada range to obtain photographic proof of their existence. The photographs made for these surveys depicted the magnificence of the American landscape and helped people to recognize the intrinsic value of untouched natural areas. This subsequently led to the establishment of the first National Park, Yellowstone. An interesting fact of history is that

lthese places were declared as valuable national treasures and set aside by people who actually had never experienced them firsthand. Photographers had simultaneously found a role in preserving the environment, and alienating their audience from the subject.

The impact of these classical photographs is so great that this original aesthetic has endured through more than a century of change. Our culture is inundated with images of the landscape's awesome beauty as ifit still exists today as it did more than a century ago. Landscape photographers have seen ground-breaking movements like the "new topographies," which investigated man's development of nature; individual photographers such as Richard Misrach and Mark Klett are addressing our culture's imprint on the landscape and relationship to it respectively. However, there has not yet emerged a recognized body of photography that directly addresses, or attempts to change, our perceptions of, and relationships to, the landscape. We are now on the verge of entering this new era of imagery, but for the most part the general public prefers classic landscape pictures.

Time-honored landscape

photography depicts nature as idealized and unchanged. Persons well-versed in photography fully understand the technical application of the medium and its ability to record things so that they appear much more precise and perfect than they are firsthand. Light, color, and detail can be enhanced or altered from the original scene. Photographs are not documents of the truth; they are representations of a reality that existed in front of the camera as interpreted through the artistic vision of the photographer. We sometimes forget that the camera is a framing device rendering only what the photographer has chosen to show. The realities that exist outside of the frame are not always revealed to the audience. This is especially true of many beautiful landscape photographs that quite often are taken from a roadside or parking-area overlook. An uneducated audience may actually believe the natural world is as pure and static as it appears in photographs. These classical reflections of the land can still evoke a sense of awe in the viewer, but they are misleading and inaccurate depictions of how earth now exists. Our appreciation for majestic landscapes is the reason that most conservation efforts have focused only on showpieces. Photographs have transformed certain places into icons, and as with Yellowstone, we recognize many of our national parks, monuments, and forests through images. It is necessary to have such preserves and an appreciation for them, but it is not sufficient to conserve based only on visual worth. We must also learn to recognize the value and importance of all the smaller pieces of our environment, like the nearby pond that acts as a resting place for migrating waterfowl. The contemporary culture is faced with incredibly complex issues

e n n l u m d e r e k

johnston

David Mussina, Buffalo Herd, Yellowstone National Park, I 989

Masumi Hayashi, Love Canal, No. I, 1991, panoramic photo collage, 2 l "x35"

Masumi Hayashi, EPA Superfund Site, Salem, 1990, panoramic photo collage, 26x3 l"

19

that must be solved in order for "nature" to continue to exist. It is my concern that where we focus our appreciation has contributed to some places becoming "islands of wilderness." Classical, romantic images of the landscape create a separate and distorted perception of contemporary society's environment. If an artist is inspired by the land's awesome beauty and has a romantic relationship with it, still he or she should take into serious consideration what the consequences are of serving up an idealized vision for the public's consumption.

Photographs are seductive. When people see an image of a beautiful place, it creates a strong desire to experience the area. What photographs cannot communicate directly are ideas like those of renowned ecologist Aldo Leopold, who in his essay, Round River, outlines nature as a complex series of ecosystems in which all aspects of life are interconnected. Humanity's undeniable place in this system compels us to experience nature, and our national parks have come to serve this need. Millions of people travel to the far reaches of America every year to fulfill some deep inner need, either spiritual or primal, to have a "natural" experience. As a result, many of America's best-known natural areas more closely resemble theme parks than natural preserves. We travel many miles only to participate in the same mundane, meaningless activities of our everyday lives and thus reaffirm our separateness from nature. We do not take the time to recognize the greater configuration of a vista and the importance of these places within a whole natural system. Nor do we recognize all the smaller parts of these systems which may be more accessible to us. We perceive nature as the fa~ade that photographs show.

"Industrial tourists," as phrased

The contemporary culture is faced with incredibly complex issues that must be solved in order for "nature" to continue to exist.

by Edward Abbey, spend their time roaming the countryside, trying to accummulate all the grand views of the United States. The expectations of these experiences are outlined by images that are etched into our memories. When one visits Yosemite National Park, one expects to see it as it is depicted in a picture one has previously seen, such as Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, California by Ansel Adams. Ifit so happens that the day or moment one is there is not as spectacular as the instant a photographer may have waited months or even years to capture, there is disappointment. We quickly move on, for there is only time for a fleeting glimpse of the most renowned vistas. Luckily they are clearly marked for us as scenic overlooks.

Karal Ann Marling refers to the bizarre space where culture clashes with the natural world as the "middle distance." In this "middle distance" one may not see, or care to notice, the paved parking lot lined with motor homes, or the guard rails that act as barriers between our world and the natural world. The landscape is presented to us as a spectacle. It looms in front ofus as a wonder, separate and distant from ourselves. It is this distance between nature and culture that restrains us from participating in the natural world and from truly understanding it.

We exempt ourselves from Earth's intricate workings and therefore remain passive observers of an alien world. Our lifestyles and technological advances support our belief that we are separate from, or above, nature. Writer and philosopher Morris Berman theorizes that the state of people's relationship to the natural world has two epochs: before and after the scientific revo1u tion. The first one is the enchanted view of nature, in which all life was believed to be a part of a

Mark Ruwedel, The Slow Death, 1993, (I) Snow Canyon, Utah, (r) The Gobi Desert, The Conqueror,StarringJohn Wayne, (filmed in 1954, following 31 atmospheric nuclear test in Nevada)

20

Willie Osterman, In Search ofMyth: #2, 1994 Earthographic print, l 4x 11"

Alan Phelan, detail from ReflectingPond (installation),1993 silverp-rint, wad, water,glass,brass,silicone, 70x20x3"

greater whole: "A member of this cosmos was not an alienated observer of it but a direct participant in its dramas." Berman refers to this as "participatory consciousness," which "involves merger, or identification, with one's surroundings, and bespeaks a psychic wholeness that has long since passed." The second epoch, post-scientific revolution, has developed a linear, scientific mindset that has been one of"progressive disenchantment." Our disconnection from nature is a result of this mindset. "[It] can best be described as disenchantment, non-participation, for it insists on a rigid separation between observer and observed. Scientific consciousness is alienated consciousness: there is no ecstatic merger with nature, but rather total separation from it." Photographs help maintain our observer status. Although they may initiate a relationship with the natural world, often they go no further. Instead of serving as a stepping stone to a rich and direct understanding of nature, photographs have become surrogates for such experiences.

Landscape photographers develop a unique relationship to the natural world. They spend extensive amounts of time in the outdoors, continually aware of light, weather, and the change of seasons. But they may delude themselves into believing that viewing their work is as moving an experience as making it. The classic methods used to communicate and establish an understanding of the intrinsic values of the natural world have come to a dead end. Perhaps this is because they never were actually able to sway humanity's need to feel control over nature. The roots of our problems lie deep within

Instead of serving as a stepping stone to a rich and direct understanding of nature, photographs have become surrogates for such experiences.

our psyches and solving them means questioning our culture's relationship to nature. We can no longer divide ourselves from nature, because we are undeniably a part of it. It is imperative for us to find a better understanding of the earth as a whole. This will require the development

of new mythologies and paradigms surrounding nature and ourselves.

If this is the path that we must follow, here is the place on the path where I find obstacles. Are images ever going to communicate ideas about conservation and ecology that we as a culture need to know? Is humanity too caught up in itself to care? Are we all living in a delusion by believing that we can cause change? Has our environmental situation already gone beyond the critical stage? Can civilization do nothing but decline? How close is the end of nature as we know it today? These are questions we must ask ourselves as we travel forward toward a new millennium.

-© 1995 Derek Johnston W o r k s C i t e d: Abbey, Edward. "Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks." Desert Solitaire. New York, NY: Random House, 1968. Berman, Morris. The Reenchantment of the World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981. Marling, Kara! Ann. "Not There But Here." Between Home and Heaven; Contemporary American Landscape Photography. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1992. Leopold, Aldo. "The Round River." A Sand Country Almanac; With Essays on Conservation from Round River. New York, NY: Ballantine, Books, a division of Random House, Inc., 1966.

Derek Johnston is an artist-in-residence at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado. He is a landscape artist whose work involves reenchanting the natural world. This article is presented with the hope that it will serve as a catalyst for more responsible practices of landscape art. Johnston is the curator for the Center for Photography at Woodstock (Woodstock, New York) exhibition Fragile Landscapes, May 20 -July 16, 1995. Included artists are: Don Bernier, Lukas Felzmann, Masumi Hayashi, David Mussina, Alan Phelan, Mark Ruwedel, and Willie Osterman.

I

Don Bernier, (I tor) Travelogue, 1994, 28:00 min., 3/4"; Two Nights in TJR9, 1993, I 3:00 min., 3/4"; Terra incognita, 199 I, 13:25 min., I"; video stills (original in color)

Willlie Osterman, In Search of Myth #8, 1994 Earthographic pnnt, l4x l l"

21

Don Bernier, (I tor) Travelogue, 1994, 28:00 min., 3/4"; Two Nights in T3R9, 1993, I 3:00 min 3/4"; Terra Incognita, 199 I, 13:25 min., I"; video stills (original in color)

The landscape is at present one of the subjects in contemporary photography which is the most revealing, problematic, and divisive of different photographic schools. This might at first sound like a surprising assertion: Artists and critics are so immersed in the discourses of the body and the problems of sexual politics and identities that the idea of the landscape is almost quaint, old-fashioned, and even irrelevant. But in fact, many of the most ambitious and innovative photographers now working concern themselves with landscape imagery. Nevertheless, it is also true that some of the most reactionary and derivative work in all the medium involves landscape work that is too imitative of great predecessors for its own good.

During the 1970s landscape was one of the dominant genres of photography; the "new topographies" and images of the "social landscape" were fashionable and endorsed by many museums. Much fine work in this mode exists, and many of its practitioners continue to work today, though with varying degrees of success. Lee Friedlander,the heroic figure of this group, abandoned his trademark out-the-car-window and around-the-telephone-pole images, following an organic development of style and subject which has resulted in some quite different images. On the other hand, StephenShore(once noted for highly colored pictures of the American vernacular landscape) has failed to find new forms for his work. It seems to have dried up or bogged down in the respectively arid and water-saturated landscapes of Texas and Scotland, where he has worked more recently. Aggressively formalist "straight" photography has fared badly n the long run. A theme repeated too often can come to lack conviction, and artists more concerned with formal issues than with meaning or content are those whose work becomes empty most quickly.

LewisBaltzis the landscape photographer whose work changed

PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE END E L L E N H A N D Y 22

LANDSCAPE

Lewis Baltz, Rule Without Exception, installation view, P.S.1, 1990. PiazzaSigmundFreud to the left, three 50x70" Duratran panels Rule Wirhoui Exceprion to the right, one 50x70" Duratran (original in color)

Lewis Baltz, Corso Dei Lavoro, (Luck in Luck), 1992, one panel, Cibachrome print, (original in color), 75x50" (Baltz reproductions Courtesy Janet Borden, Inc., New York)

Aggressively formalist straight" photography has fared badly in the long run.

most interestingly during the 1980s. Refashioning the nearly absolute clarity and austerity of his earlier work into a richer, more experimental form, Boltz hos mode a remarkable transition. Earlier projects like Pork City and Son Quentin Point were intelligent, ambitious, and impressive, but dangerously near to dogmatism, and uncomfortably precious in the form of print portfolios and limited edition books. One admired rather than liked that work.

Boltz's changing style is emblematic of the wider change in the photographic zeitgeist. In experimenting with new forms of presentation, like installations and light-box displays, Boltz hos paradoxically come to emphasize content over form. Always fascinated by marginal places on the edges of urban culture, Boltz used to make photographs whose very minimalism of presentation suggested that it must be their spore forms rather than their atypical subjects

that really mattered. Now that he is ploying with the presentation, the images' subjects hove begun to change too. Images like Piazza Sigmund Freud ore layered like millefeuilles pastries with meanings, ironies, and allusions.

The unconsidered spaces of European-built environments have a very different symbolic valence than American ones do. Boltz always understood how culture had acquired an upper hand over nature, but his recent works dramatize this rather than brooding about it, as his earlier ones did. Baltz's color work is a brilliant demonstration of what color materials really allow a photographer to say. It makes a mockery of the preciously decorative efforts of a photographer like Joel Meyerowitz. His initial confusion about whether color photography was an instrument for realist observation of changing light, or one for expressionistic renderings of his own emotions, led to increasingly empty (if popular) work. To the ex1entthat Boltz's cool aesthetic tolerates emotional investment in his photographs, it is the viewer's own emotion, brought to the photograph and exercised in the space of the represented landscape.

An equally unsentimental landscape photographer of the new breed is Alfredo Jaar, who uses both light boxes and installations, but to very different ends than those of Lewis Baltz. Jaor's probing and emotional pieces deal with global politics, often literally mapping connections between notions, industries, and individuals. More interested in border transaction than in urban spaces, Jaor's work demands a sophisticated cognitive involvement as well as an emotional response from the viewer.

Of course, many photographers still working in the traditional landscape modes ore also doing richly satisfying work. Of these,

Derek Johnston, Seeding Grasses, Hialea, 1992, l8x23", (original in color)

Ruth Thome-Thomsen, I979

toned silver print, from the Expeditionseries, 4x5 11

Ruth Thorne-Thomsen, Screwhead, Colorado, 1986 toned silver print from the series Viewsfrom ,he Shoreline, 5x4", (Thome-Thomsen photographs Courtesy Ehlers Caudill Gallery, Chicago, Illinois)

© MANUAL, (Hill/Bloom), Worldmaker, 1992 from the series Two Worlds, Type C prim, 39 1/zx36 1/z"

(Courtesy Jayne H. Baum Gallery, New York)

23

Thorne-Thomsen'sinfluenceis widespread among younger photographers,so muchso that today buildinga landscape seems as viable and available a choice for a photographer as findingone to photograph.

the most successful are those who, like Ray Metzker and Emmet Gowin, have arrived at their present lyrical imagery by way of a long search and many chapters of experimentation. Other artists whose technique is as impeccably conservative as that of Shore, Meyerowitz, or Paul Caponigro are doing landscape work animated by ideas and concerns far removed from the dead ends of l 970s-style formalism. Though the universe may contain eternal verities apprehendable by means of art, it is the art that acknowledges our temporal specificity which is most likely to reach the universality that lies beyond. Paul Graham knows this, and his classical color landscapes of the mid-l 980s are animated with the urgency and complexity of politics and history, human passions inscribed in and as graffiti on the troubled landscapes and streets of Northern Ireland. Richard Misrach's views of the American West work in a similar way. He presents that mythic landscape as the locus of the repressed consciousness of our culture's sins. Both men's passions keep pace with their discriminating visions.

Baltz, Joor, and Misrach all are concerned with what landscapes are like and with what they may reveal to an attentive or interrogatory viewer. Other photographers concern themselves with different questions, such as: Where are our landscapes today? How do we experience them? How are they composed? What meanings do we find in them? Ruth Thorne-Thomsen is one of the photographers who, in the 1970s, brought these questions into prominence by building delicately nuanced artificial landscapes for the benefit of her camera. These small, wistful images are like incitements to time travel. Their sites are the exotic destinations of more than a hundred years ago, and the photographic processes used mimic those in use at the very dawn of photography. Ouietly denigrating the notion that photographs are any kind of practicable surrogate for reality, Thorne-Thomsen's pictures are like declarations of independence from the tyranny of the Walker Evans school of on-site photography.

Her influence is widespread among younger photographers, so much so that today building a landscape seems as viable and available a choice for a photographer as finding one to photograph. While Thorne-Thomsen'slandscapes are poignant symbolic arenas, Derek Johnston's constructed landscape images contain an idealistic conception of the sublimity of the landscape while acknowledging the flaws and lacunae in human connection with nature in contemporary culture.

The collaborative team MANUAL (Edward Hill and Suzanne Bloom) uses a different type of studio construction to render landscape images, in that their work is computer generated. Their science-fiction style floating geometric forms are striking, if somewhat menacing impositions on the landscape. MANUAL's 1992 installation Forest Products included analog and digital photographs, video sculptures, and two interactive computer programs. Their work

24

MANUAL, Forest/Products, 1990-91, (Courtesy Jayne H. Baum Gallery, New York)

Lorie Novak, Fade Out, 1990/92, color photograph, 29 1/,x37"

Lorie Novak, Night and Fog, 1991/92, color photograph, 28 1/,x39" (Novak's pictures Courtesy Jayne H. Baum Gallery, New York)

Novak's exceptionallyintelligentand undogmaticwork persuasively insists that the landscape is not separate from those who walk upon it, and that our visions of it are not separable from our lives.

comments on environmental politics and economics, using contemporary technology to do so.

Lorie Novak also uses technology and imposes imagery onto the landscape, though in what is at once a far more literal and more evocative way. Her photographs depict haunting projections of photographic elements (often faces) onto nocturnal landscapes. Her inscription of faces and other images onto the earth itself, and her photographic recording of this intervention of art into nature, beautifully connect emotional states, habits of mind, and photographic practices. Novak's exceptionally intelligent and undogmatic work persuasively insists that the landscape is not separate from those who walk upon it, and that our visions of it are not separable from our lives.

With none of the lyrical loveliness of Novak's work, Jeff Wall's imposing photographs make some similar points. The strange and artificial tableaux he organizes both outdoors and inside are the painting of everyday life of our time, and at a truly heroic scale His immense color transparencies depict both scenes too banal ever to be recorded in snapshot photography, and highly stylized and dramatic narrative passages. Wall's work rejects the possibility of a landscape separate from human experience and puts significant as well as insignificant episodes before the camera to create images at an aggrandizing scale.

Landscape art for the twenty-first century needs to represent not just our topography but also our culture. National parks have come to look more like the crowded parking lots for trailers that Bruce Davidsonsaw on his trip west than like what AnselAdams saw on innumerable hikes at Yosemite. Nature is no longer separable from human experience but must include it. The landscape exists neither as wilderness nor as refuge from civilization. To alter an old conundrum, if a photograph is taken of a tree falling in a forest, then we know that someone was there to see and hear it. Landscape photography in the future will need to accept the kinds of insights achieved by the photographers I've mentioned above, and it will also continue to change. The most important attribute for the landscape photography of the future, to my mind at least, is intelligence. To follow in the footsteps of nature-lovers with cameras is now far from enough; to imitate the visual magic of Atget or Evanswithout thinking anew will not suffice If this genre is to continue to be meaningful, it will have to change more than remain the same.

- © 1994 Ellen Handy

E LL E N HAN DY is a Jane and Morgan Whitney Felow in the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A forthcoming publication includes PhotographyAs Womens Work: Visionsand Revisionism(on exhibition catalog for the Steinboum Krauss Gallery, New York City). Handy has written reviews of more than one hundred exhibitions of contemporary painting, sculpture, ond photography for Aris Magazine.

Jeff Wall, The Goat, 1989 installation view, Cibachrome transparency, fluorescent light, display case, 229x309cm

Jeff Wall, The StumblingBlock, 1991, Cibachrome transparency, flourescenr light, display case, 90x 1327/s''

Jeff Wall, Pleading, 1989, steel, plexiglass, and Cibachrome, 54x73 1/1x9 1/4'' (Wall's pictures Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York)

25

address correction requested

s;,.,t;.....,;w.,.-,,., © 1992 Annie Nash Crcaung Sun

March 18 - Moy 7 INFORMATION HIGHWAY/ ALLABOUT THE HUMAN RACE

CuratorColleenKenyon(Woodstock,NY). Picturesfromaroundthe worldusingnew technologies and communicationstrategies.

SOLO: ANNIE NASH (Corrales,NM). Theartistcreatesphoto collagework investigating relationshipsbetweenidentityand the landscape. Nash worksout of the traditional her family, descendantsal the Quinault-Cowlitz, a coast Salish communityin WashingtonState.

May 20 -July 16 FRAGILELANDSCAPES

CuratorDerekJohnston/Snowmass,CO).

Artists:Don Bernier,LukasFelzmann,Mosumi Hayashi, DavidMussina,WillieOsterman, Alan Phelan,MarkRuwedel.landscape arl con be more than expressingone'sadmiration for the beautyof the natural world. Thisshow is aboutthe complex relationshipsthatartistsand audienceshove withthe environment.

SOLO: DEAN McNEIL (NewYork,NY).

An installationof sculptureand large-scaleconceptual photography.Thesubjectof the sculpturesare figurinesin moralitytableau-which the artfstcreates, sets intoplay,and photographs. ..,

Woodstock Photography Workshops

JUNE - DebbieFlemingCaffery:ExploreCajun Country-FourDaysin SouthwestLouisiana;James Luciano:Introto DigitalImaging;LynnGoldsmith:The Businessof Makingan IntimatePortrait;LenJenshel: TheCatskillMountains;JULY - EugeneRichards: PhofographingPeople;Colleen& KathleenKenyon: GettingShown/BeingKnown;StevenWest: Meeting ThroughPhotography;FronkW. Okenfels 3 The30 MinutePortraitSolution;ErnestineRuben:How You Can DevelopYourPersonalDirection;Connie_~ Imboden:Figure& Form:TheNude;AUGUST-Ken Lassiter:Howlo CollectPhotography;Jane Evelyn Atwood: ConcernedPhotojournalism;JoseOrraca: Howlo Care for Phot09raphs;John Placko:Howto Make a FineBlackond WhitePrint; A.O. Colemon: WritingTo/FromPhotographs;Ann Lovett: Introductionto DigitalImaging;Marie Claire Montanari: TheNude Figure;Larry Fink: Discovering fhe Intuitive.SEPTEMBER - EricLindbloom: Photographyfor Teens;EricKrieger:Photographing the World'sMostFamousSmallTown;LucilleKhornok: Fashion& TheFigure;RobertGlenn Ketchum:The landscape of Colo, OCTOBER/NOVEMBER-Antonin Kratochvil:TenDaysin EasternEurope;Jane Tuckerman:FiveDaysin Oaxaco, Mexico

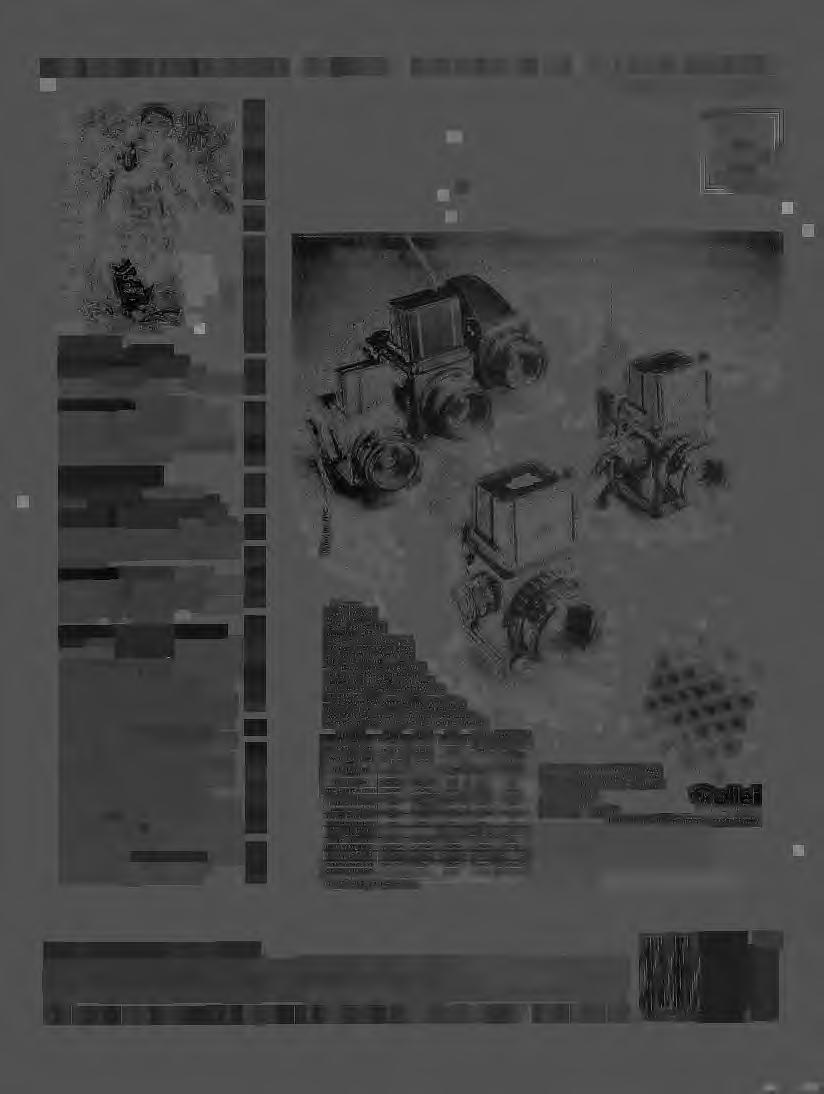

Now you can get Rollei's leading-edge performance, the complete 6003 camera: body with motor, coupled meter. back, and Zeiss80mm 2.8 Planar lens for only $3995 list. Rolle/ mode the 6003 a Jitlfe smaller, a fltlle lighter than the state-of-the-art 6008 and turned somestandard features Into optronst accessories. Compare Ro/lei against any competitive model (not Just those below). Both the 6008 and 6003 surpass off medium-format and many 35mm cameras: in technology, copob/lffy, quality;

ASTOSTUDENTS

TheCenterforPhotographyschooladmitsstudentsofanyrace,color,nationalandethnicoriginto allthe rights,privileges,programs,andactivities generallyaccordedormadeavailableto students at theschool. It doesnotdiscriminate on thebasisofsex,race,handicap,color,nationalorethnic originin its administration,educationalevents,admissionpolicies,scholarshipprograms,or other school administeredprograms. THE CENTER IS FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC WEDNESDAY THROUGH SUNDAY, NOON TO PM 7

THE CENTERFORPHOTOGRAPHY AT WOODSTOCK/59 TINKERSTREET/ WOODSTOCKNEW YORK12498 / TEL 914 679 9957 FAX 914 679 6337

::.:: '-' 0 I0 0 0 :s'= 1--<C >= 0... <C """ (.!;I 0 lo = 0... """ 0 """ LL.I I= LL.I '-' LL.I = I0 I= LL.I >LL.I :z: 0 I= >< LL.I :z: 0 1--<C '-' ::, 0 LL.I

Of NONDISCRIMINATORY POLICY

NOTICE

ACC.t~NiYH vuwm,......:;. w1T11.w:c UNIRA1'GilMIWF1Ml>I: IIACKI..WAIU.au/lNIUIT lfflltf1J70/1'0,.,f:,O/Jff/>ll/"°'/1:IO!Jffln1"0U.U/120/:l'lf1,~ Dl/fH IUIHJ 1'G VU IC)1993HPMarketing, All rights r&S&rYed price, performance. And with Ro/lei's Digital ScanBack, they put you at the leading-edge of ultra high-resolution Non-ProfitOrg. U.S.Postage PAID Woodstock,NY 12498 PermitNo.33 digltof/mogtng. ~ollel The Roi/et 6003. 'K' :::;,~~;ii:l}_~nd price fototechnic looking af things from your point of view. WARNING: USING A 6003 CAN BE DANGEROUS TO YOUR HASSELBLAO SYSTEM. "Manufacturer~ suggestect /Isl price, ocluo/ cteo/er priea may vary. Hosseibloct Is a reglsrerect lroctemork of Victor Houa/blod Inc. ::.,~G:xp 16Chap,nr.ti.Pfne&ookNJ070S8.201!808-9010 6 2>

25274 81205

9