When Timothy D speaks of an “information dark age” he is not talking about a lack of information. Our once ingenuous prophecies about deluges of images too great to comprehend, 15 minutes of fame and “big brother” defined an ominous future that is now past tense. D’s dark age is more about content and while the Internet might be a force for liberation its sinister side will fascinate artists for many years to come.

As part of the pre-exhibition research Timothy D and CCAS staff explored Chatroulette, a chat room that immerses its participants in the lives of suspect others while enabling intimacy, anonymity and exhilarating voyeurism. Moving from room to room engaging with three men, the final stop came with a stream of entertaining invective, lewd suggestions and finally a criminal act on the part of the unknown contact. This reminds us that the Internet is not just a source of useful information or a mode of communication, it is also an amusement park and massive crime scene where the latter two frequently overlap.

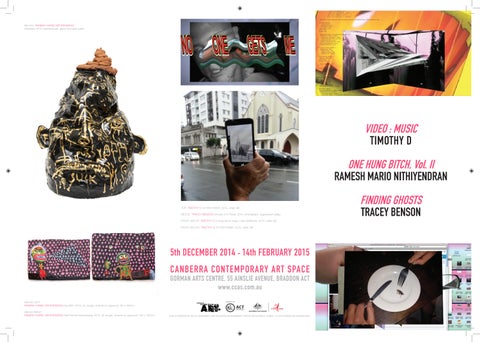

The Internet is Timothy D’s shadowy playground. His innocuously titled and net-centric exhibition Video : Music consisting of video, sound and live feed is, upon closer inspection, perverted and voyeuristic. D is of the last generation of artists not born with the Internet, but who have grown up in its omnipresent company. This exhibition reflects not only an enduring relationship with the net but also covers the period of its rapid development.

The source material for Timothy D’s work is not only the flood of images found on the Internet, however. He also speaks of the influence of the Flicker or the Structural film movement of the 1960s and early 70s, in particular one of its chief protagonists Paul Sharits whose seminal work T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968) included a looped soundtrack of the word “destroy”. The proponents of ‘flickers’ challenged the hegemony of mainstream cinema by treating film as the projection of still images presented in a very quick succession. The flicker therefore, is a collision of single shots creating rapid strobing that references and celebrates the flickering effect of silent movies of the 1920s.

While Sharits concern was the raw physicality of film or the machinery of projector and celluloid, in D’s time this sense of the material has been all but lost to the seemingly intangible technologies of digital video. And yet the basic concept of clashing stills remains. Thus he focuses on the endless illusions created by passing images and the effects on human consciousness. Along with his composed soundtrack, that augments a sense of conflict between image and sound, he, like avant-garde or experimental film makers aims to generate a disorienting environment in the gallery that will fracture the audience’s understanding of virtual and video imagery as it is encountered in everyday 21st century life.

Timothy D acknowledges that all films, digital or celluloid, are to some extent flicker films or at least the result of frame-by-frame progression through a camera and projector. Like the artists of the Structural film movement, however, he makes no attempt to hide the mechanics of vision and is able to show us what we might not otherwise see.

the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body

I once read that there are more words in the English for penis than any other object. While this may not be true, there are indeed many such words that emphasise the importance of penises in English at least. The phallus at the centre of Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s work is based on two cultural phallocentric paradigms – the first in Hinduism where Shiva Lingham, a symbol of power and fertility, is widely believed to represent Lord Shiva’s penis and is worshipped as part Hindu creation mythology. The lack of shame concerning genitalia in traditional Hindu society provides a stark contrast for the second paradigm, Christianity, which Nithiyendran describes as a “ … misogynistic, patriarchal religion that inadvertently worships the penis.” He recalls scripture classes and images of Jesus naked and nailed, his loincloth thinly disguising the holy genitalia. It is from the Victorian/Christian view of sexuality, supressed and policed, that modern pornography has emerged; all the more exciting for its furtive character.

The rise and rise of Internet pornography has generated a fertile contemporary context in which the phallus has been able to reclaim its central place. For Nithiyendran, however, this is not simply a story about men and throughout his works he has searched for ways to subvert cultural mores and conventions in sexual fantasy. One Hung Bitch was first based on a film of the same name with transsexual star Suzanna Holmes in the lead role. “ … with a huge penis … she fucks all these white men and women,” he says, “I looked at transsexual bodies, and bodies that were phallic but not gendered as completely male.” In other words, introducing a transgender figure into the overall story Nithiyendran is able to distance his work from straight white misogyny.

In the production of his work, be it 2 or 3D, painting, drawing, printmaking, ceramics, sculpture or installation Nithiyendran appears to pay little attention to technique (as we understand it). He described himself as “kinda shit at art, because I don’t colour within the lines”. His rejection of the rigidities of fine art making have generated a characteristic kind of anti aesthetic and enabled the development of a unique practice. Importantly, the work is tangible evidence of the artist’s hand and its power is not in a refined finish but rather an ability to communicate ideas around sex and societies in ways that are both outrageous and amusing. His works often have a raw unfinished quality that paradoxically becomes their finish, their ultimate resolve.

On this quasi-spiritual site of phallus worship One Hung Bitch, Volume II resembles a pagan bacchanal, a critical orgy in which the artist attempts to test and cajole, to mess with the minds of his audience. And yet it is not his intention to shock – especially since this is particularly difficult these days. One Hung Bitch, Volume II reflects cultures with hang-ups through the presentation of deified “dickheads” and “shitheads” that take the piss while providing incisive commentary. There is something distinctively liberating about Nithiyendran’s work as one feels the joy of his defiance, as if he has done whatever he has been told not to do – with brilliant success.

Quotations from an interview with Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran by Luke Watson http://www.oystermag.com/interview-phallocentric-artist-ramesh-mario-nithiyendran

One Hung Bitch, Vol. II has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, NAVA, UNSW Art and Design, and The City of Sydney

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran is represented by Gallery 9, Sydney

The title FindingGhosts is not simply a cute attempt to generate a frisson around three series of regular photographs taken as part of city walks in Auckland, Dunedin and Copenhagen. Tracey Benson’s ghost metaphor is appropriate, not because ghosts have the potential to scare the bejesus out of the living, but rather because they connect us with the past. Where ghosts are present it is a past that is not quite dead, an unresolved past with which we are often uncomfortable.

Benson’s spectres of times past represent a psychogeography of the present. Pyschogeography, with links to Guy Debord and The Situationist International (1950s) concerns the ways geographic environments impact upon the emotions and behaviour of individuals. It is also about creating inventive strategies for exploring urban spaces and this is precisely what Benson achieves in her work with the technology of Augmented Reality.

Benson’s walks plot a course through an historic site/road such as Karangahape Road in Auckland. K Road, as it is also known, is significant in Māori legend and today has gained notoriety as a seedy space of nightclubs, strip joints, restaurants, thrift-shops, galleries and residences. For people on the walk the experience consists of three parts; the walk itself, the map with photographs of selected buildings along the way and a virtual encounter with the past. Using an application called Aurasma the viewer is able to place an Internet enabled mobile device running iOS or Android (tablet or smartphone) against the image and wait (seconds) to be transported into the past. From a hideous modern office block for example, emerges the beautiful Tivoli Theatre demolished in 1980 for the Sheraton Hotel scheme.

Augmented Reality (AR) is a live direct or indirect view of a physical, realworld environment whose elements are augmented (or supplemented) by computer-generated sensory input such as sound, video, graphics or GPS data. Much of its beauty for Benson’s project is that you don’t need to be on the actual walk to enjoy the experience. Finding Ghosts, the exhibition, consists of the remnants (photographs) of three walks that provide the viewer with the necessary information to be transported to another time. Through the changing architecture of her images that are both made and collected, the present is revealed through its comparison with the past. Depending on the subjective judgment of the beholder, there is a nostalgic poignancy in each transition that speaks to a bygone era. Importantly this does not come from Benson’s being didactic but rather as a response to this specific form of access to the past she has invited through the use of technological tools and the Internet.

The metaphorical ghosts occupy each fade, as we transition from a world of colour to the high contrast black and white world of archival photographs from the 1920s and 30s. Benson’s walks are fascinating journeys in time and while she seems somewhat distant from the work when it is shown in the gallery (compared to the walks) she also leaves her audiences with ample space for imagination.

David Broker, December 2014