ARMA CHRISTI

Lenten Reflections on the Instruments of the Passion

Fr Philip Caldwell

All booklets are published thanks to the generosity of the supporters of the Catholic Truth Society

Image Credits

Pages 7 & 8: Monogram of Christ Combined with Instruments of the Passion by Anonymous, Rijksmuseum. 31 & 32: Altarpiece with the Passion of Christ: Flagellation by German artist (ca. 1480-1495). Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1909. The Walters Art Museum; 51 & 52: Scenes from the Passion of Christ: The Crucifixion by Andrea di Vanni. Corcoran Collection (William A. Clark Collection), National Gallery of Art, Washington; 57 & 58: Hof Altarpiece: The Crucifixion by Hans Pleydenwurff, Sammlung Picture Gallery; 65 & 66: Christ Shown to the People by Jan Mostaert, The Jack and Belle Linksy Collection, 1982. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 71 & 72: The Deposition by Follower of Rogier van der Weyden, The J Paul Getty Museum; 77 & 78: The Entombment of Christ by Fra Angelico. Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington; 83: The Crucifixion; The Last Judgement by Jan van Eyck. Fletcher Fund, 1933, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 84: The Crucifixion with Saint Jerome and Saint Francis by Pesellino. Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Wikimedia Commons: page 15 & 16: The Crucifixion by Andrea di Bartolo, PD-Art; 25 & 26: Diptych with John the Baptist and St. Veronica by Hans Memling, PD-Art; 37 & 38: Rehlinger-Altar, Mitteltafel: Kreuzigung Christi by Ulrich Apt the Elder, PD-Art; 43 & 44: The Master of the Benediktbeurer Crucifixion, Crucifixion, Alte Pinakothek, PD-Art.

All biblical quotes are taken from the Jerusalem Bible

All rights reserved. First published 2026 by The Incorporated Catholic Truth Society Cabrini Community Campus Forest Hill Rd, Honor Oak, London SE23 3LE Tel: 020 7640 0042. www.ctsbooks.org © 2026 The Incorporated Catholic Truth Society.

ISBN 978-1-78469-856-0

The Arma Christi

The Arma Christi

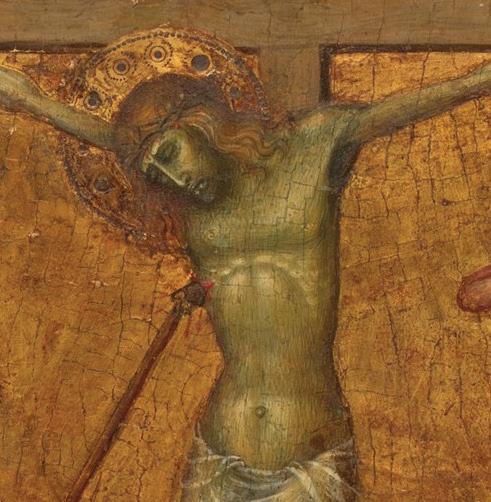

The parish church of Our Lady of Grace in Prestwich, Greater Manchester, is a neo-gothic building completed in 1930. Our forebears went to great lengths to decorate the interior beautifully and as an expression of faith. Inside there are a lot of wood carvings by the Italian art studio of Stuflesser. Behind the high altar is a huge reredos with a crucifix and statues of Our Lady and St John. Something similar graces the sanctuary of many churches, perhaps yours has the same? Set within the ornate wood carvings of the reredos, are some angels. They hover at the four corners of the Cross, carrying the instruments of the Passion. This, too, is a common arrangement. Over the years, many believers have found inspiration for their prayer before this altar: the figures standing guard over the drama of our salvation that is re-presented on the altar, daily. These weapons, called the arma Christi, have also made me think while I’ve been praying and reflecting on the Word and the Sacraments, that we participate in during the liturgy. As we approach the celebration of these mysteries again, at Easter, I thought it might be helpful to share these reflections with you.

Lent began with a declaration of war: The opening prayer on Ash Wednesday spoke about the beginning of a campaign. The language of spiritual combat is not so popular as it used to be. And yet, we can’t deny the reality

of the struggle: that as soon as we start to give things up, to try to tackle a bad habit and change, or to go from good to better, it’s a battle. We’re part of a spiritual battle against the dark powers that control us, rob us of our freedom, and make our life unmanageable. In this conflict, it’s good to know that God is on our side. But what might this mean in reality?

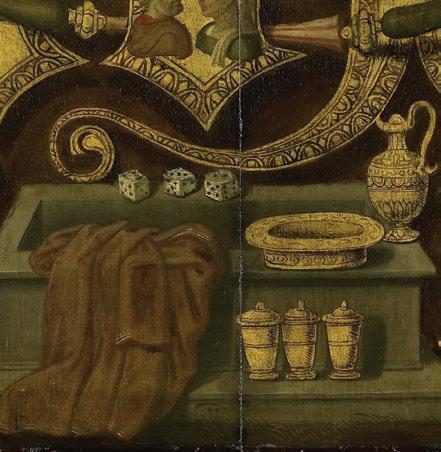

If you take a closer look at the angels carrying the arma Christi in our church or elsewhere – Bernini designed some archetypal ones on the Ponte Sant’ Angelo at Rome – you’ll see they often carry the lance or arrow, the hammer and nails, the crown of thorns, ladder and rope, the pillar, dice or even the cock that crew after Peter’s denial. There are all sorts among what the angels hold; a choice – but there’s nearly always Veronica’s veil – bearing the image of Christ’s face. This made me think that in these instruments – all of them – we come face to face with our own humanity. Like the disciples on Mount Tabor, who we consider on the Second Sunday of Lent, here we see a reflection of ourselves. In these weapons, we come face to face with our human weakness, as through the Passion and the ministration of the angels, it’s shaped anew into the image and likeness of God. Maybe these angels have a message for us this Lent – some wisdom they’d like to share with us about the spiritual battle that we’re engaged in? About what it means to have God on our side and the weapons of Christ at our disposal.

Whose weapons are they anyway? Well, they’re certainly not just the weapons of Jews – or the Romans or leaders: they’re the weapons of humanity itself. Instruments of evil that still mark our world, and that we all use in some way to wage war on each other and on creation. We might not have an actual lance or veil, but we can pierce with a sharp word or take someone’s image away with what we say or the gossip we engage in. Yet Jesus, who is on our side, has taken up these weapons of ours. For us and for our salvation, He has allowed them to be used against Him, so that the humanity that He shares with us might be transfigured into the image of God. Belonging to the whole of humanity, they have become the weapons of Christ – the arma Christi, so that we might use them now to transfigure us and our world. How can we do this?

Well, every time we’re pierced by criticism or crowned with some indignity – every time we have our own image maligned, thirst for what’s right, or taste the bitterness of life, we might share in his work of transfiguration. And every time these comparative pinpricks happen to us, we can be united, in Christ, to our sisters and brothers throughout the world, who suffer far more grievously than we do. Then, we have the chance to use these weapons for their good and for God’s glory. Sadly, each day, the news seems to present us with new conflicts in different parts of the world and in our own country – with what many have suffered and continue to suffer. Our good intentions,

honed through the prayer, fasting and almsgiving that this Season encourages are heightened just now. But how can we be united to these suffering others in a way that’s more meaningful than simply the money we could give?

Why don’t we ask God’s messengers, the angels who surround the Cross, the instrument that we will shortly kiss, to minister to us as they did to Him during His Forty Days? We wouldn’t want our kiss to be empty on Good Friday, would we? But rather, full of the compassion that these weapons can reveal. May the angels help us to win glory in the day of battle and to have our place in Christ and a share in His work.

Let me tell you about my teeth. I haven’t got many left! I’ve broken quite a number, and others were so damaged that they had to be extracted. Clenching, grinding, and biting down was a nightly activity of mine. Subconsciously, I’d sometimes do it in the daytime too. Often, I’d wake pushed right up to the headboard of the bed in a tight ball; the foetal position. My jaws would be aching, and on occasion my mouth full of blood. I had a Polish dentist – a good Catholic – and he made numerous guards and shields for my teeth. They didn’t work too well because I would bite through them.

One day, as he examined me, he said, “I don’t get it, Father, what’s going on?” I looked at him blankly. I’d been in quite a lot of pain and I just wanted him to make things better. “Well, this biting down and grinding; this breaking

of your teeth, it’s obviously fear. And this is what I don’t understand – the antidote to fear is faith. Don’t you have it? What exactly are you frightened of?” I wasn’t expecting a homily from the dentist that day but as I returned to the carpark, I wondered about his words. In the previous years, I had had a few challenges one after another: my mother had died quite suddenly, I’d had treatment for cancer, and in my new parish I’d suffered an aggravated burglary.

When we are tested, when we suffer in life, we can engage with it physically, even psychologically or mentally, without engaging with it existentially. With our very self, we can resist, hold ourselves back. My teeth exhibited the fact that I was withholding myself from what was happening to me. I was resisting and trying to prevail against these trials. I saw them as exterior to me and as things against which I must defend myself. I did not see them as a sharing in Christ’s sufferings – as a personal engagement to be with Jesus crucified. For all the theology I’d read and all the lovely sermons on the paschal mystery that I’d preached, I did not accept the sufferings that had come my way as a mysterious gift of personal identification with the death of Jesus. I was resisting with all my might. I was trying to put these things aside, to avoid or refuse them. And because I didn’t accept and identify, I had no comfort in life and therefore no joy. No joy in knowing that the Spirit was with me, uniting me to Christ, likening me to Christ.

I’m sure you won’t misunderstand me: I’m not suggesting I should have masochistically sought out this stuff, not suggesting these things came to me directly from the hand of God – but that a simple acceptance of the everyday sufferings of my life could have united me to Christ and the power of the cross. I cheer myself up by remembering just how much of the Scriptures is marked by a resistance like mine: Peter’s “God forbid it Lord, never” rings out in all of us (Matt 16:22).

It’s no accident that weeping and grinding of teeth is the hallmark image of hell. It’s really pride and selfishness that lead us to think we can cope alone and by going in on ourselves – literally – and in fact all we encounter is unhappiness and fear! We miss out on the life and freedom of the Gospel.