Chinese Calligraphy Studio, Artist Residence, and Museum

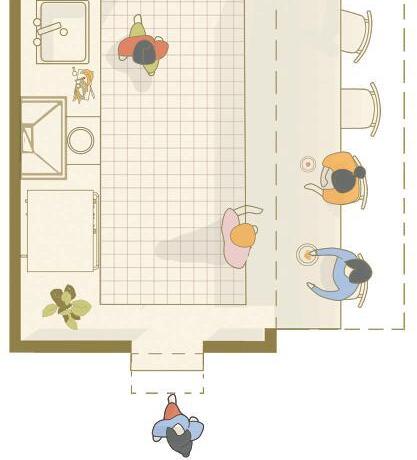

A variety of artistic practices drive the architecture of an artist collective block, which contains 6 live/work structures individually designed by studio peers to foster a culture of interconnection among block artists and public engagement with diverse mediums.

Artist Collective Mediums -

a: Tattooing

b: Chinese calligraphy

c: Surfboard care

d: Mexican cuisine

e: Japanese wagashi confections

f: Korean soju brewing

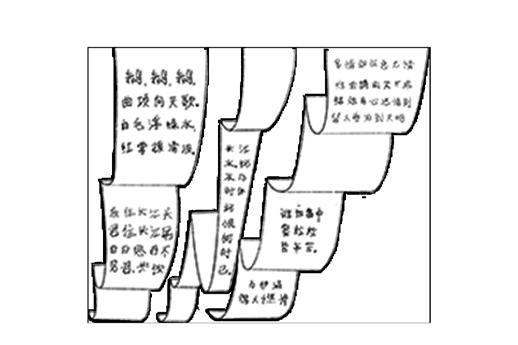

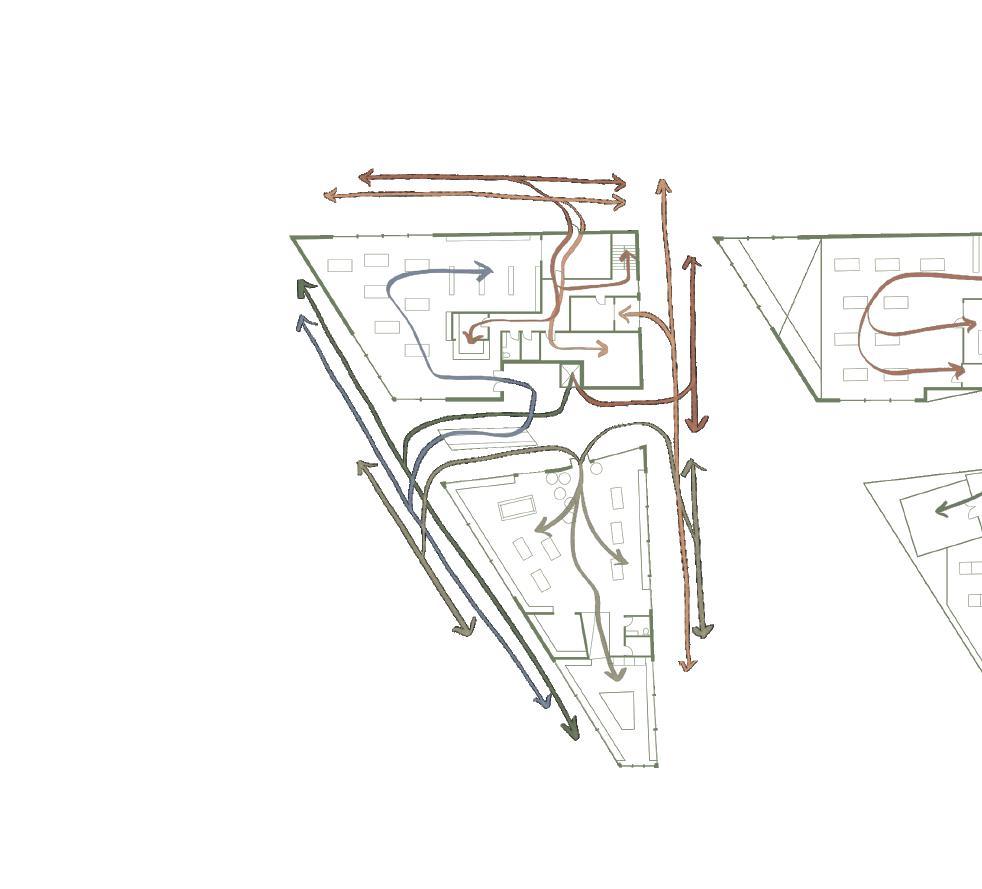

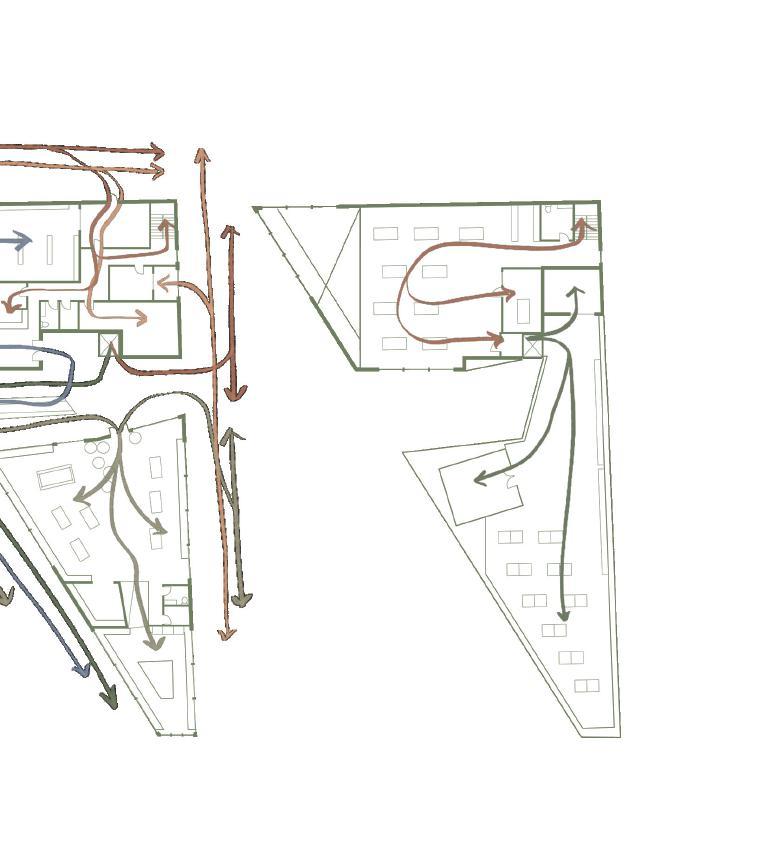

This project envisions a Seattle Museum of Traditional and Contemporary Calligraphy (SMTCC), where the essence of a calligrapher’s work inside the museum is reflected through the design of the building as a whole (“inside out”). Through the museum’s outward expresssion, the public is invited inside to not only visit exhibited artwork, but learn about the process of the art’s creation through the lens of Chinese calligraphy being both an ancient art and a modern medium for expression (“outside in”).

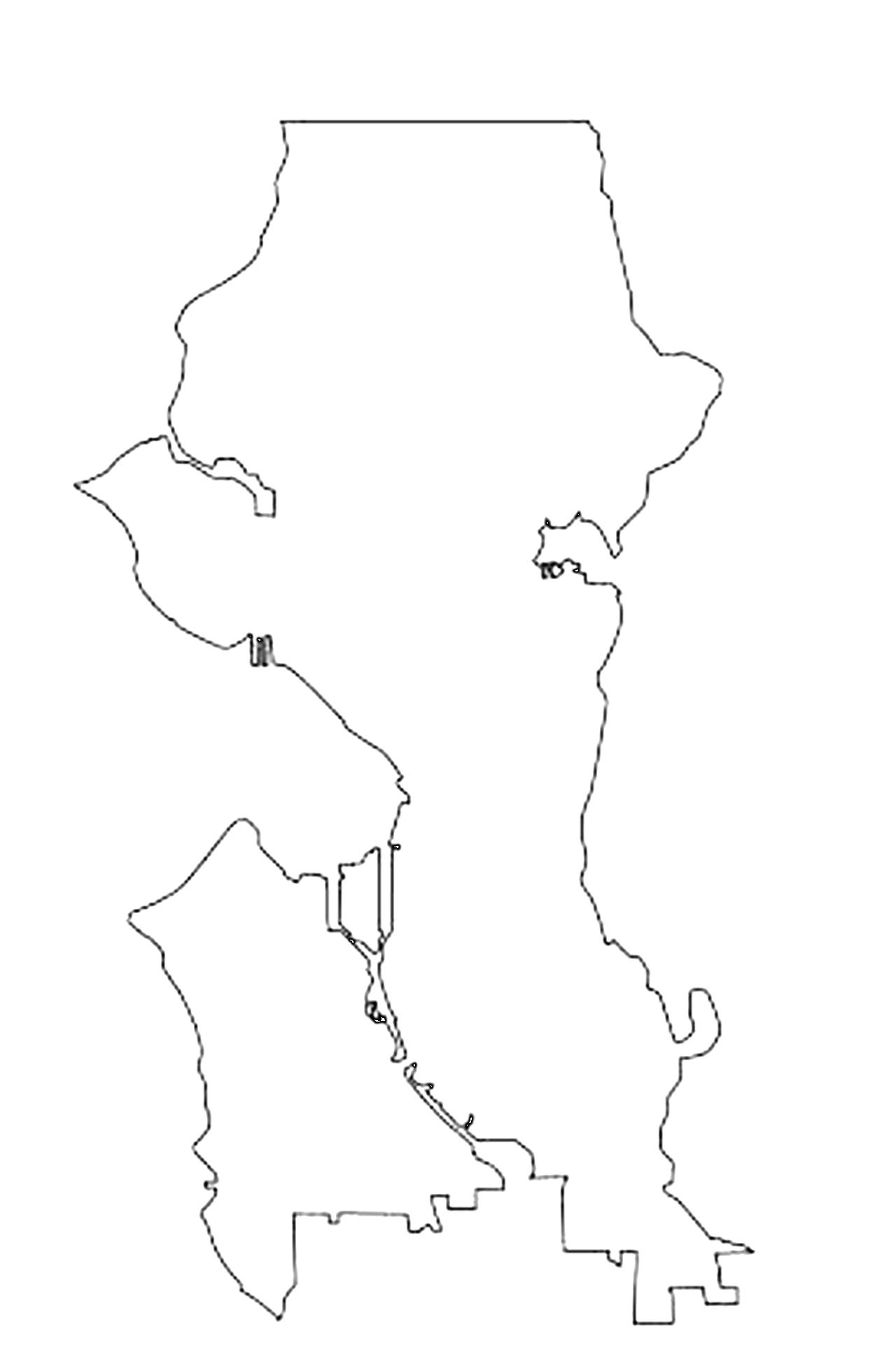

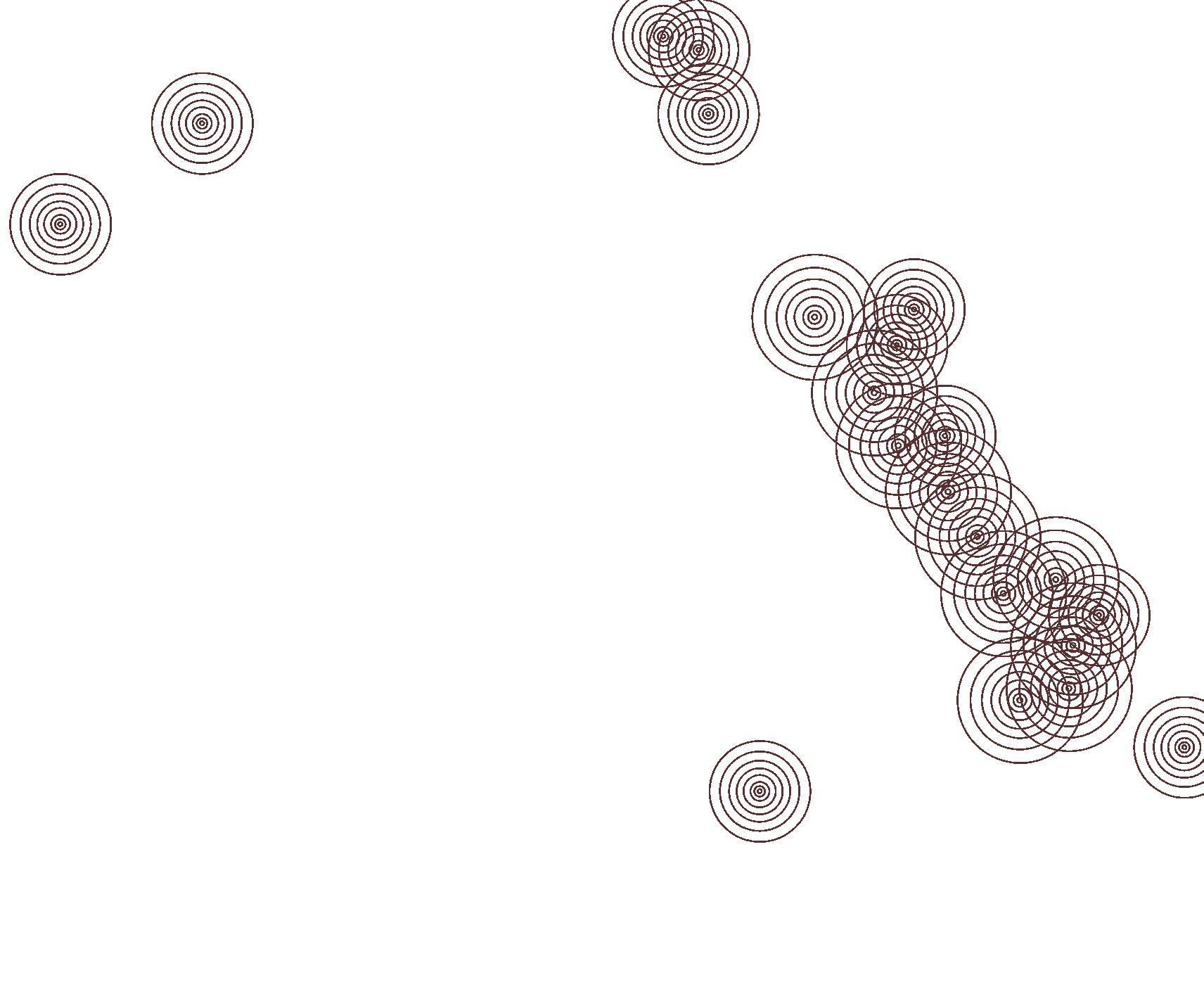

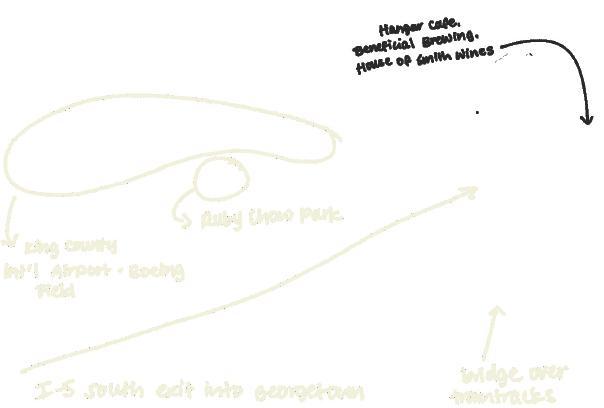

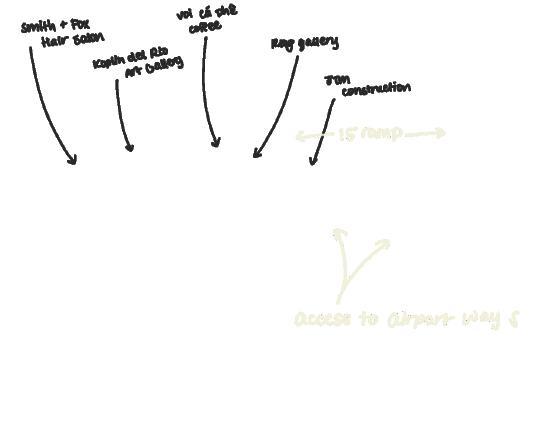

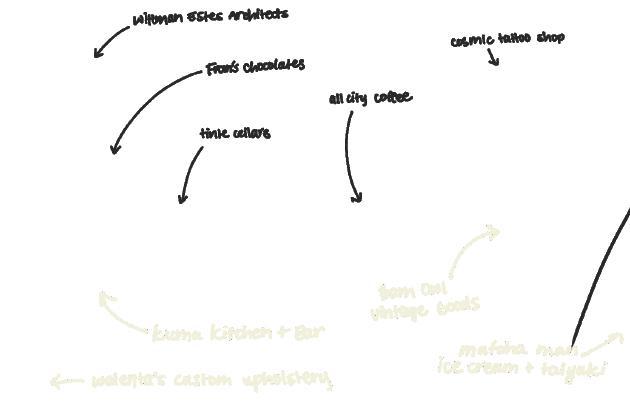

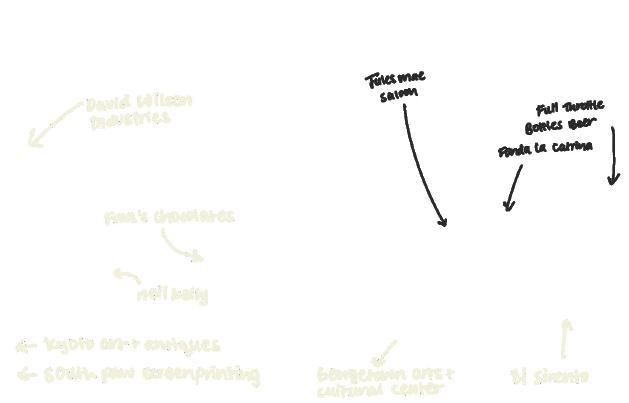

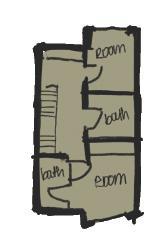

The artist block and SMTCC is settled in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood. Populated with the storefronts and facilities of many creatives, the area is a hub for making. Currently, places of making are concentrated to the east of the neighborhood.

Achieving a creative culture that is inclusive of greater Georgetown, the artist block promotes expanding density to the southwest.

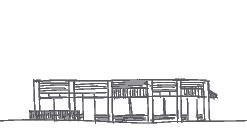

Through pedestrian scaled facade designs and glazing that allow peeks into various crafts, the establishments of Georgetown draw passerby into making processes. Following suit, SMTCC elevations are proportioned into thirds, with a third at grade to welcome the public into views of calligraphy being crafted, exhibited, and its exterior and interior architectural influence.

Human-scaled facade proportions

South Facing (Side) Elevation

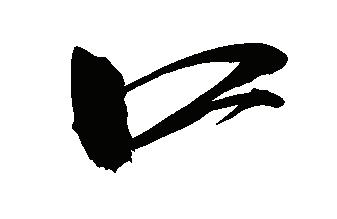

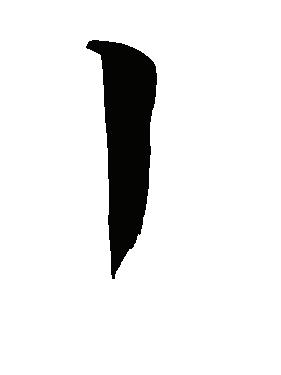

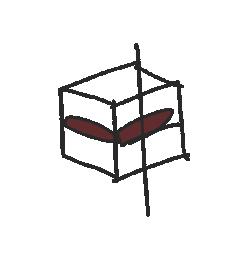

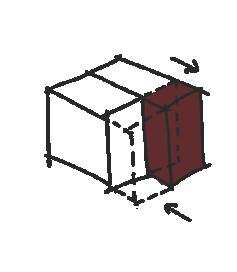

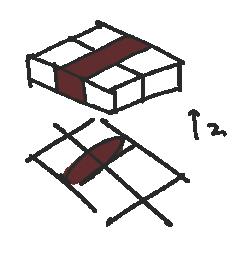

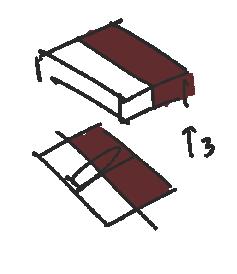

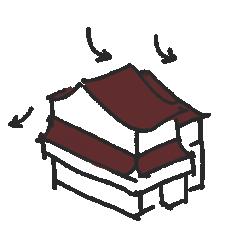

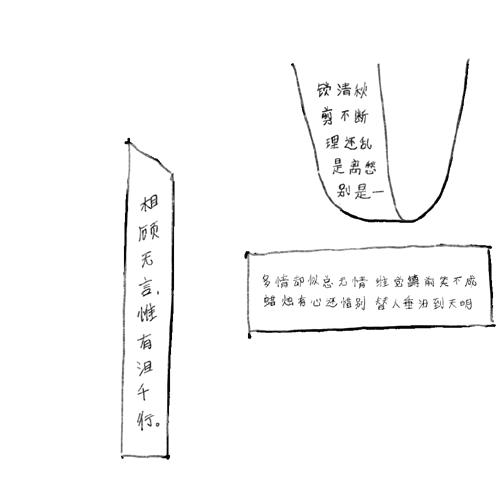

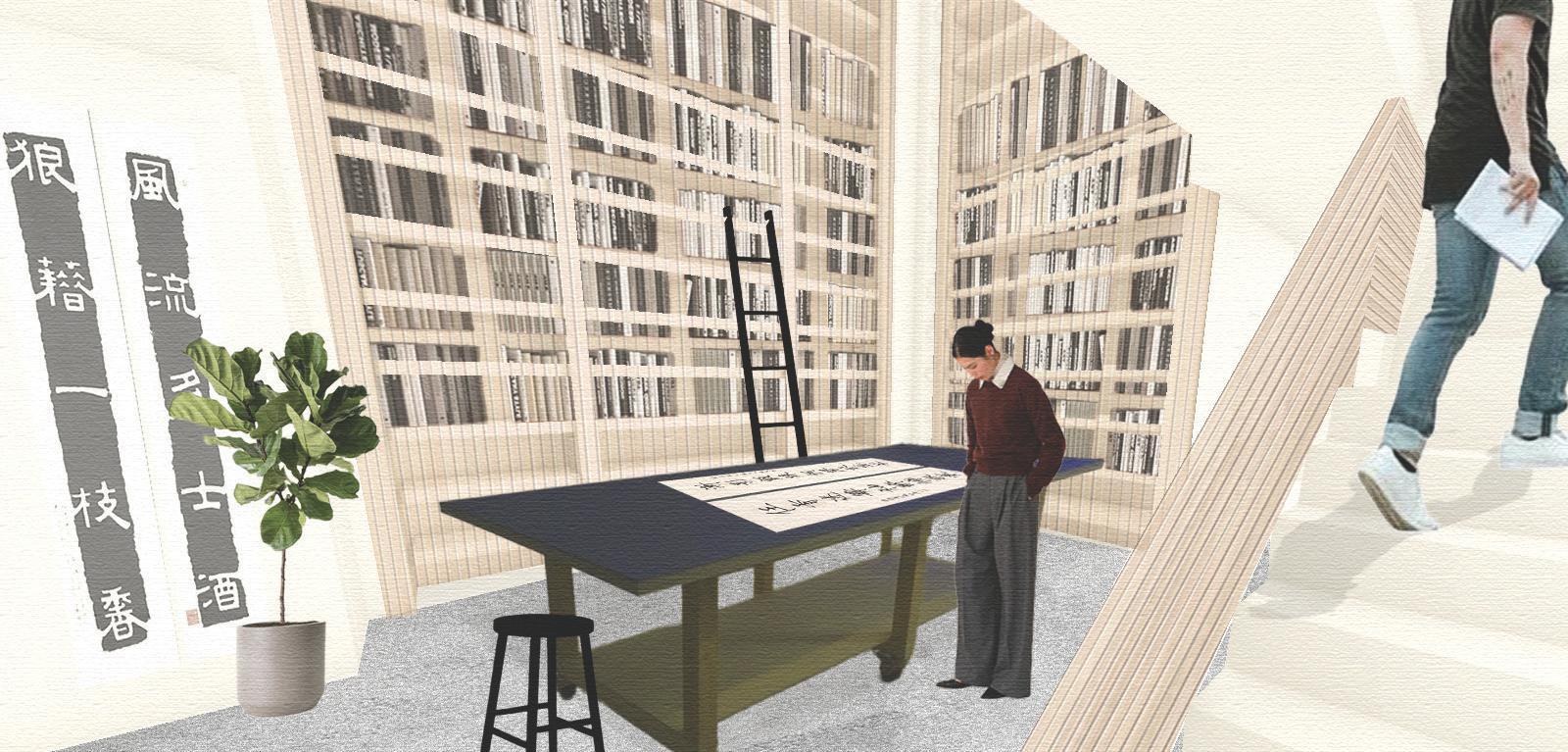

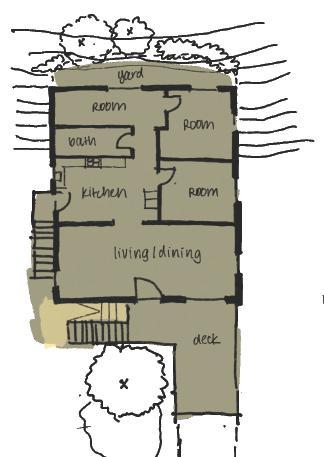

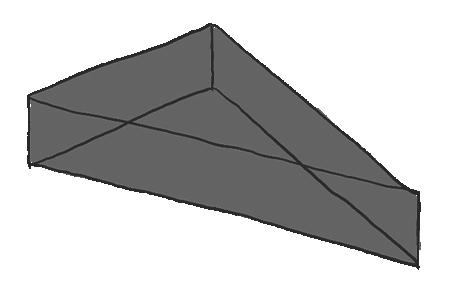

The building’s design development uses the Chinese character for “middle”/“center” and its traditional stroke structure to sculpt facades and spaces. Stroke order and hierarchy, integral to the practice of Chinese calligraphy, also inspire the round-about circulation of the museum’s core, which features tall spaces to accentuate the verticality of artwork and a double height library where visitors can take a peek into the craft of a calligrapher below.

massing design development

massing design development

Studying the spatial qualities and facade design of a mid-term design iteration informed final design moves, such as reversing the divide between private and public spaces. This brings added visibility of exhibited art to pedestrians, shields library materials from north winds and weather, and heightens the library’s feel of intimacy. An additional iteration is seen in the roof structure, inspired by Chinese hipped roofs, 庑殿顶, which further weaves the museum art to cultural origins while expressing a contemporary sweeping design.

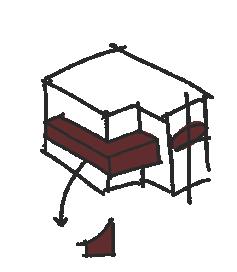

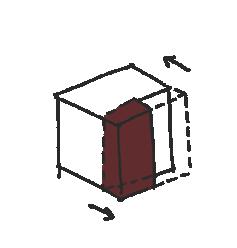

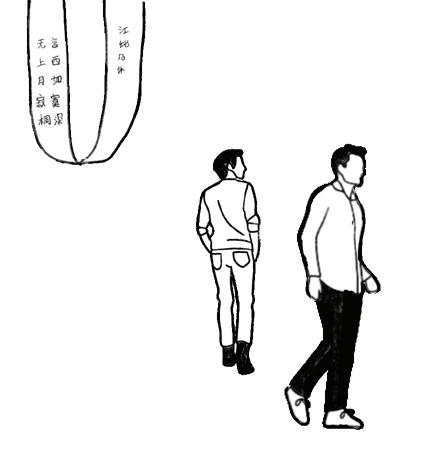

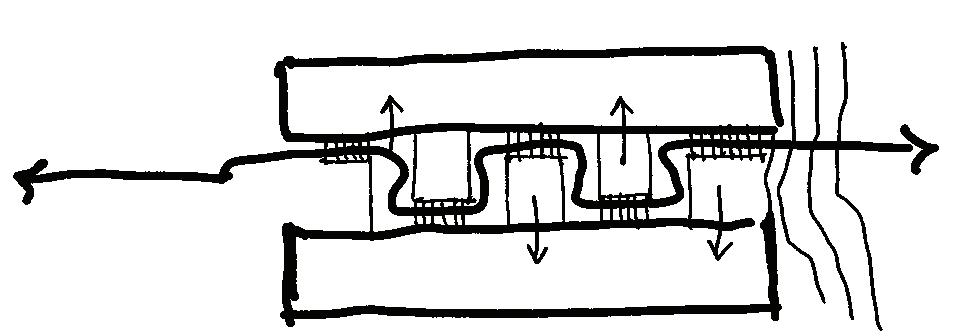

Relationship between inside and out: Weatherproof exterior curtain and sliding doors shield visitors and art...

while allowing them to coexist with nature.

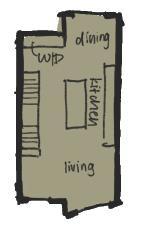

While museum visitors view art, a resident calligrapher may work and live with controlled degrees of privacy (ie circulating gallery doors can open during exhibition hours and close when needed). The working spaces fully support traditional essentials (4 Treasures of the Study) and practical workflows, as the double height library serves as ample material storage and an integrated below-stair sink supplies running water for ink preparation.

and art storage)

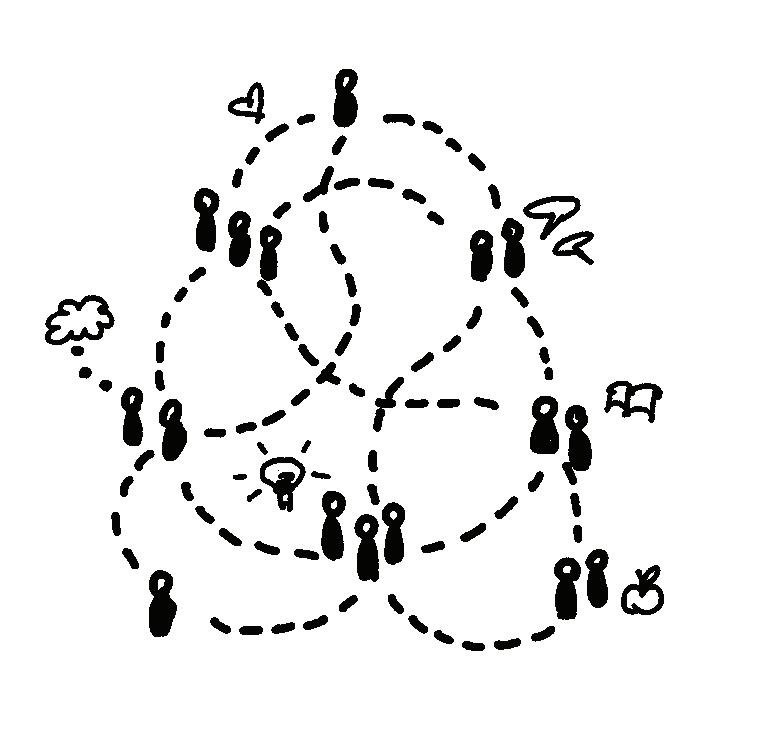

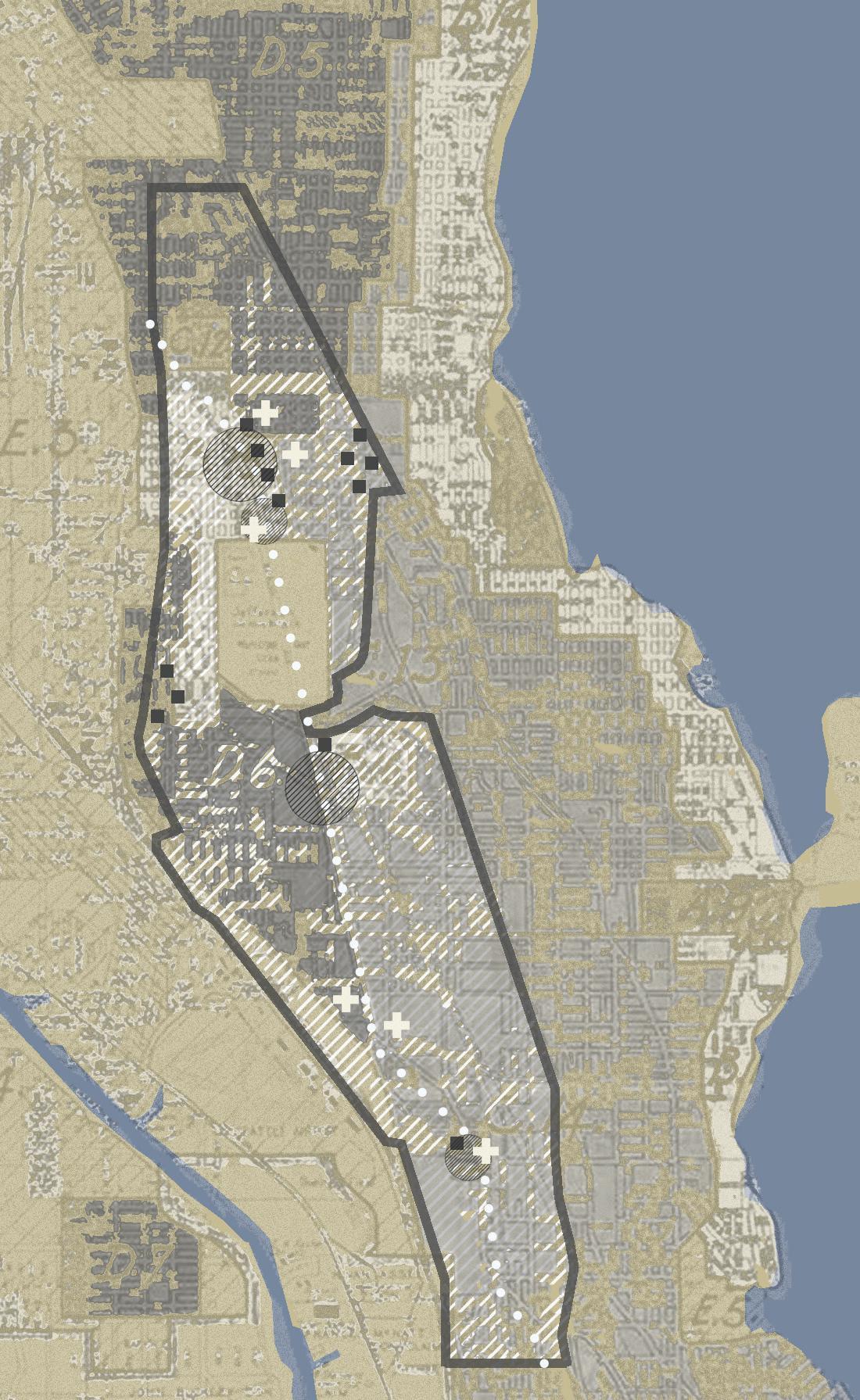

While the adjacent Capitol Hill embodies an accessible art scene, the South Lake Union (SLU) area of Seattle is dominated by the exponential growth of large tech companies and luxury lifestyle programming. To break down socio-economic and cultural divides between the two neighborhoods, this project draws inspiration from fungal systems to propose a design intervention that serves community members and their passion projects, rather than corporate interests. The ways in which creativity and market success operate in SLU are thus reimagined.

* While my partner Hannah and I collaborated on the larger concepts and architecture of the project, Hannah directed graphics (brochure design, logo, plan drawings) and I directed model making, mapping, and the site section.

traffic “magnets” in Capitol Hill + SLU

MYCELIUM Phase 3 1”:1/8” model

(above) Aerial view; Phase 4 apartment resident view

(left) John Street west-facing view

Concept diagram: A Blocked vs Exploratory Pedestrian Experience Existing SLU Culture Community Forward Marketplace

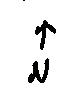

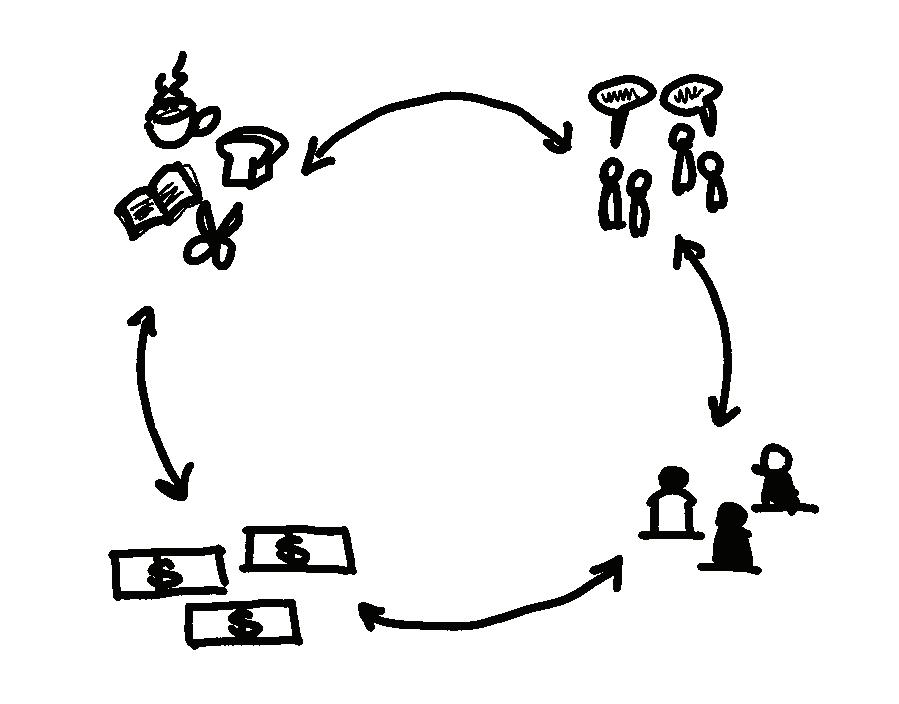

Operating Structure

Abstracted Diagram

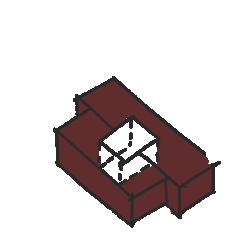

Rather than building a wholly new environment for the benefits of a few, MYCELIUM repurposes a neglected outdoor corridor and the two abandoned warehouses that flank it in order to provide spaces where individuals can work on and share their creative pursuits with peers and patrons. Akin to how mycelium networks transport nourishment to fungi, the site serves as a networking medium, providing resources and opportunities to support small scale ventures.

- John St / Terry Ave access - Elevators installed in warehouses for all mobility capacities.

- Prefabricated shop modules occupy larger areas, dedicating space to creators/business owners

- “Infecting” warehouses by adapting use to allow module occupancy and covered “third-space” gatherings

- Increase SLU density and diversity through affordable apt housing on formerly empty parking lots atop warehouses

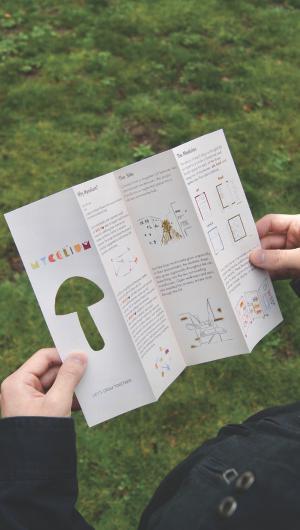

A brochure (left) can be utilized as a tool to understand the project mission and navigate the site. It presents the project site as a destination for creative empowerment and inclusivity.

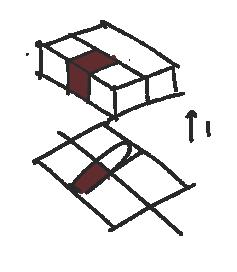

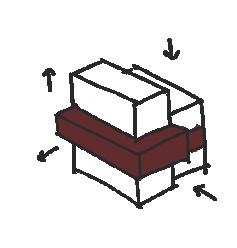

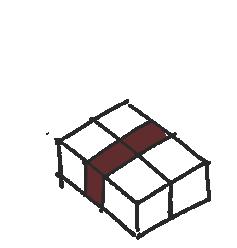

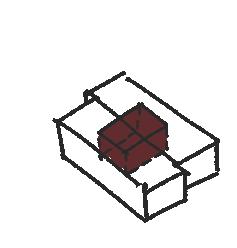

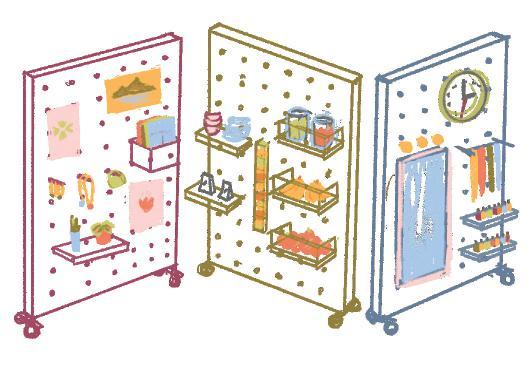

Individuals and communities can establish roots by utilizing the 8’x12’x8’ modular shops designed to fit compactly onto the project site and provide small “starter-spaces” for passion projects. The spatial flexibility of these shops allow users to tailor the modules to their needs, while supporting particular functional categories: making and sharing arts/objects, providing services, and preparing food/drink.

Module peg boards, illustrated

Module uses exemplified:

Arts and objects

Service

Food + drink

Small bar seating for longer visits

Mobile peg boards help separate private + public spaces

Walk up order counter for quick exchanges

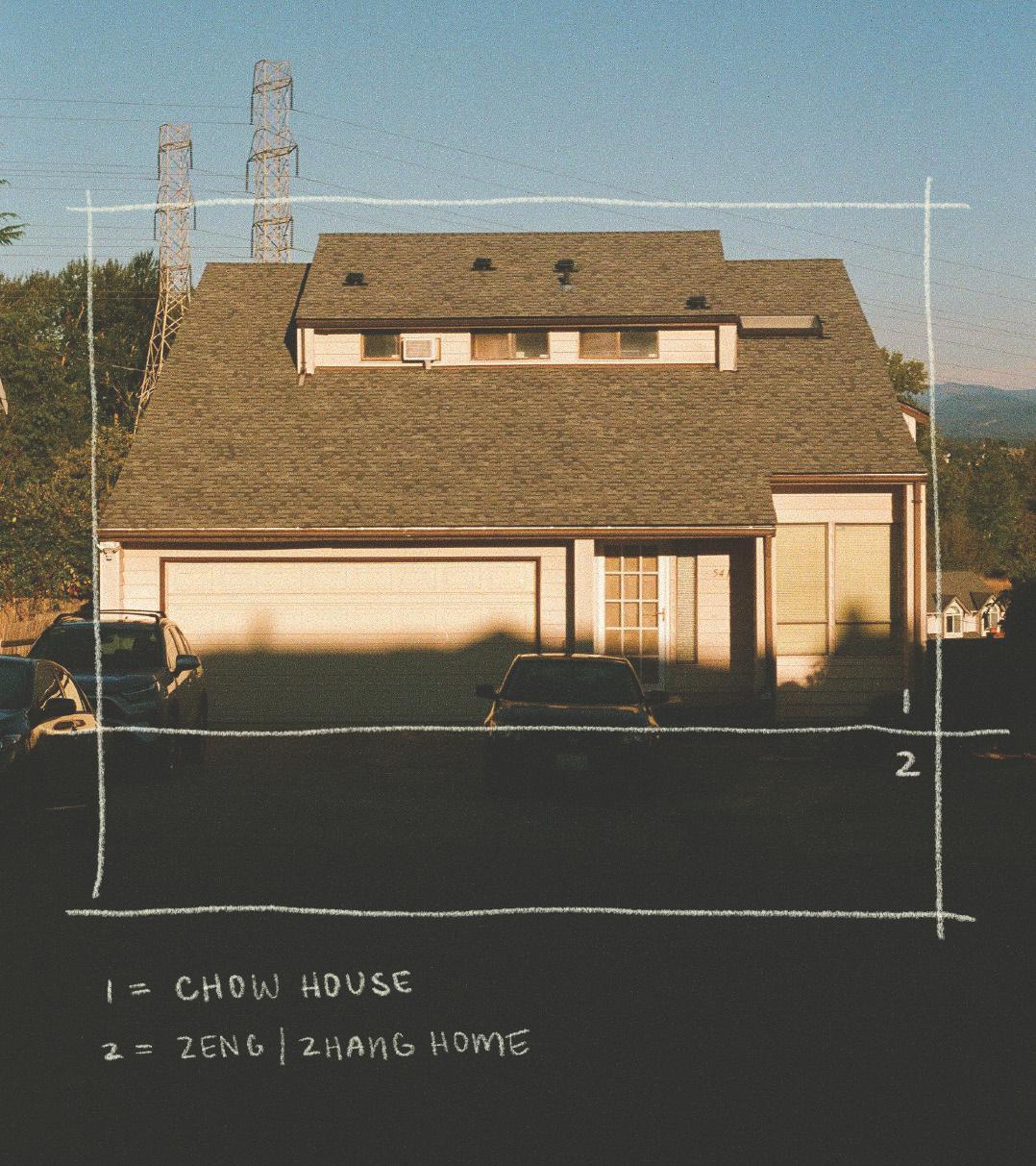

Exploring Urbanism and Housing Typologies in Beacon Hill, Seattle

A 10 minute drive from downtown Seattle, Beacon Hill has been home to many throughout history, including waves of immigrant populations and my own family in the early 2000s. This capstone assembles documentation of history, urban interventions, and common housing typologies to understand the role of communities and their evolutions in shaping the public and domestic environments of Beacon Hill. In other words, “How have people found home in Beacon Hill?”

*All photos taken personally with Pentax ME film camera.

Discriminatory redlining and city policies have historically affected southern Seattle at large, influencing how areas like Beacon Hill have housed large BIPOC and immigrant populations. In the context of additional systemic conditions, the following photos document how the hill’s community has intervened with their enviroments, creating spaces that exhibit economic agency through the establishment of businesses, or creative agency through public art.

Inferred Family/Occupant(s) 1

Inferred Family/Occupant(s) 2

Probable shared space

* Drawings not to scale/approximated.

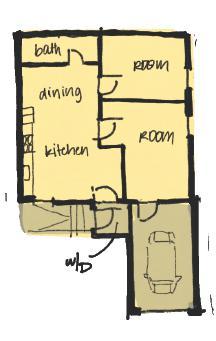

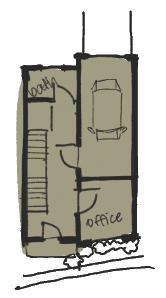

Columbian Way 98144

By dissecting two Beacon Hill housing typologies through in-person visits and online research via King County’s Department of Assessments, I was able to represent the two structures in abstracted section diagrams, plan drawings, and 3:16” scale study models. These materials allowed me to more closely analyze and compare approximate spatial relations, leading to inferences of how the two houses are/ were used by occupants. I quickly found Case Study #1 resembled my own lived experience in Beacon Hill, where two families coexisted in one single family-zoned house, divided by top and bottom with distinct egress thresholds for the different occupants. Analysis of Case Study #2 suggests an opposite form of occupancy, where spaces flow into each other, forming one cohesive home, rather than two.

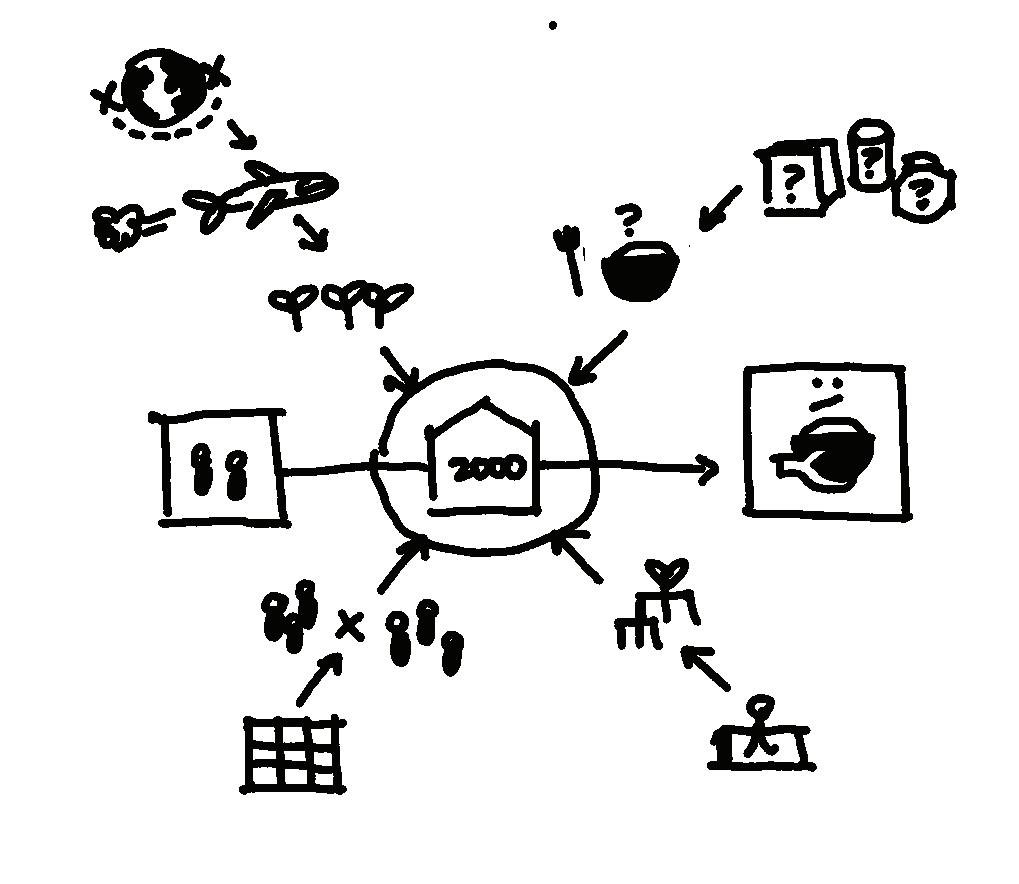

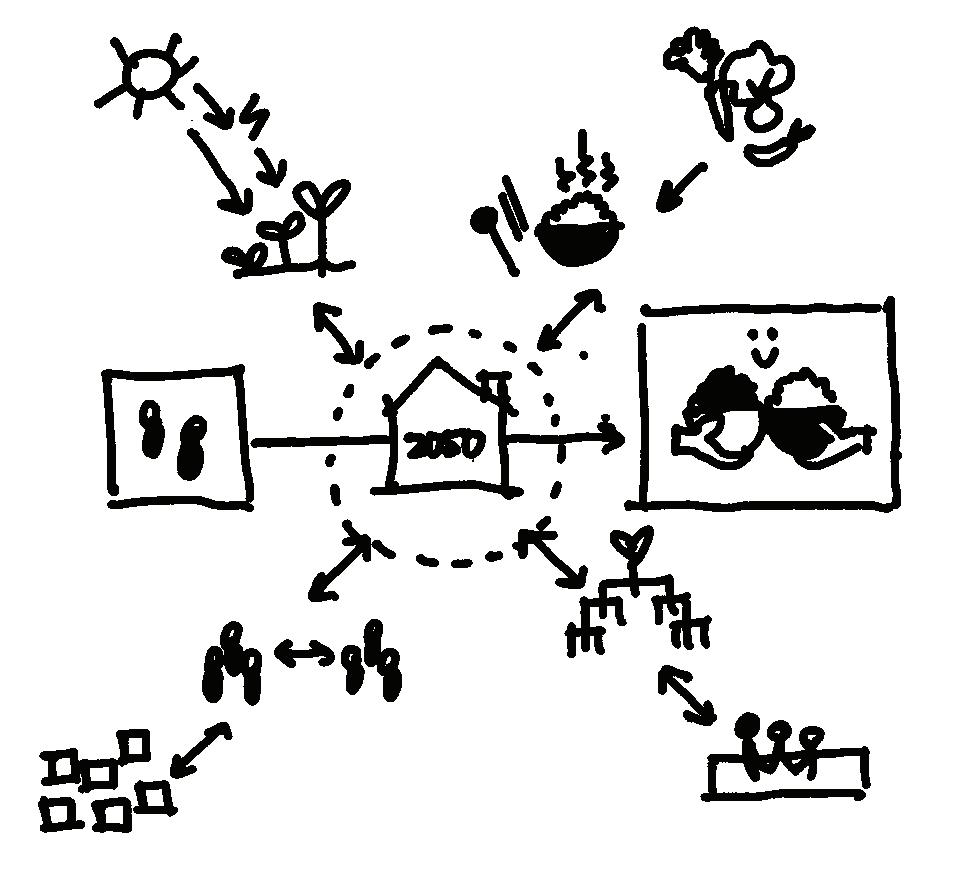

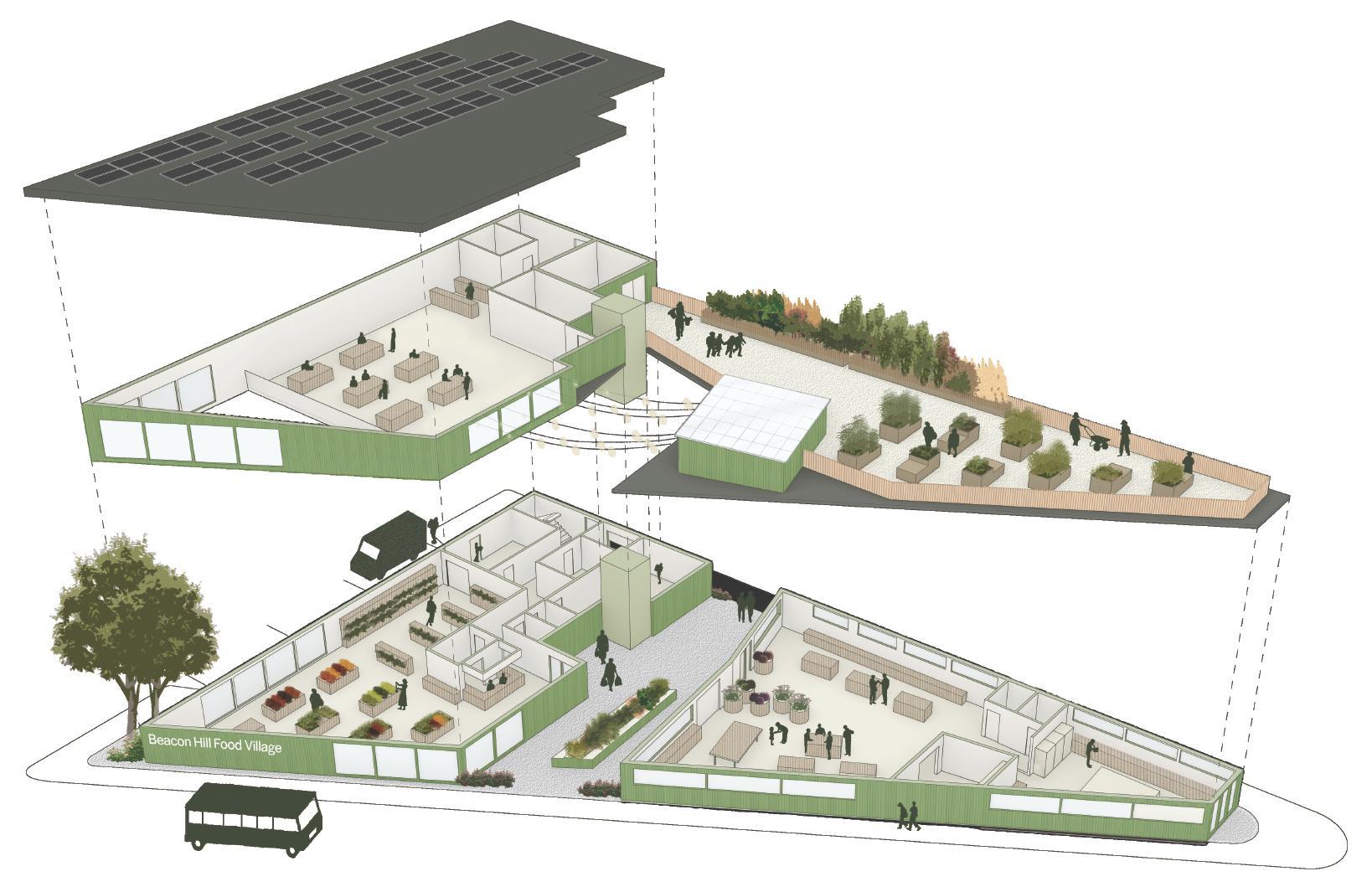

Food, Horticulture, + Cultural-Preservation Community Center

Seattle food banks lead powerful work to mitigate food insecurity, particularly in underserved BIPOC communities, but often face issues such as difficulty supplying healthy and culturally-relevant foods, and the lack of adequate spaces and infrastructure to maintain optimal resource distribution. The Beacon Hill Food Village, situated in reach of families in need and supporting a network of existing food banks, is designed to transform how food is grown, accessed, and celebrated to empower communities and the individuals to work to serve them.

“The food forest integrates food plants into

self-sustaining, semi-natural ecosystem.”

Food Village Design Values

Equitable + healthy food access (A) Intergenerational cultural empowerment (B) Future forward/sustainable urban horticulture (C) Cross community learning + connecting (D)

Surrounding Site Context

Proposed Site Block

Beacon Ave S, Seattle, WA 98144 [Currently WaFed Bank]

(pictured below) Beacon Hill establishments for culturally relevant groceries (left to right: El Centro de La Raza, Seattle Super Market, La Esperanza Mercado y Carniceria)

Access to various culturally-relevant foods and ingredients can be integral to a sense of belonging and identity - for example, how can a family remember heritage dishes if they can’t access the chilies that make the recipe authentic? Through indoor hydroponic + outdoor seasonal gardening, community kitchens, and photovoltaic panels supplying renewable energy, the Food Village empowers visitors with spaces to celebrate food and culture, while supporting local grocers and food banks with year-round fresh produce.

Flexible office space for various mission-driven community organizations (D)

Parking for food trucks or facility employees/volunteers (A)

Angled rooftop maximizes PV panel energy production; food can be distributed, stored, and grown throughout power outages (A, C)

Close proximity of tools/equipment to garden beds gardening made easy for kids/elderly/people with limited mobility (B)

Greenhouse aquaponics grow produce of international origins (A, C)

- communities can use specific ingredients for year-round culturally significant dishes (B) - smaller carbon footprint of globally imported produce (C)

Open layout encourages community interactions + concurrent activities (D)

Garden beds with integrated seating allow kids/elderly/people with limited mobility to garden comfortably (D)

Commercial kitchen fit for preparation of cultural feasts/ food events (ie Cinco de Mayo, Lunar New Year) (B,D)

(A)

The Food Village redefines systems within the design to promote con nection between users. Building circulation allows user groups to enjoy dedicated spaces for their activities/work, but still encourages interac tions with other groups. The food bank in particularly rejects convention al grocery design, where “international” foods are made overtly distinct, alienating groups and their identities; instead, all foods despite origin are presented for easy visibility.

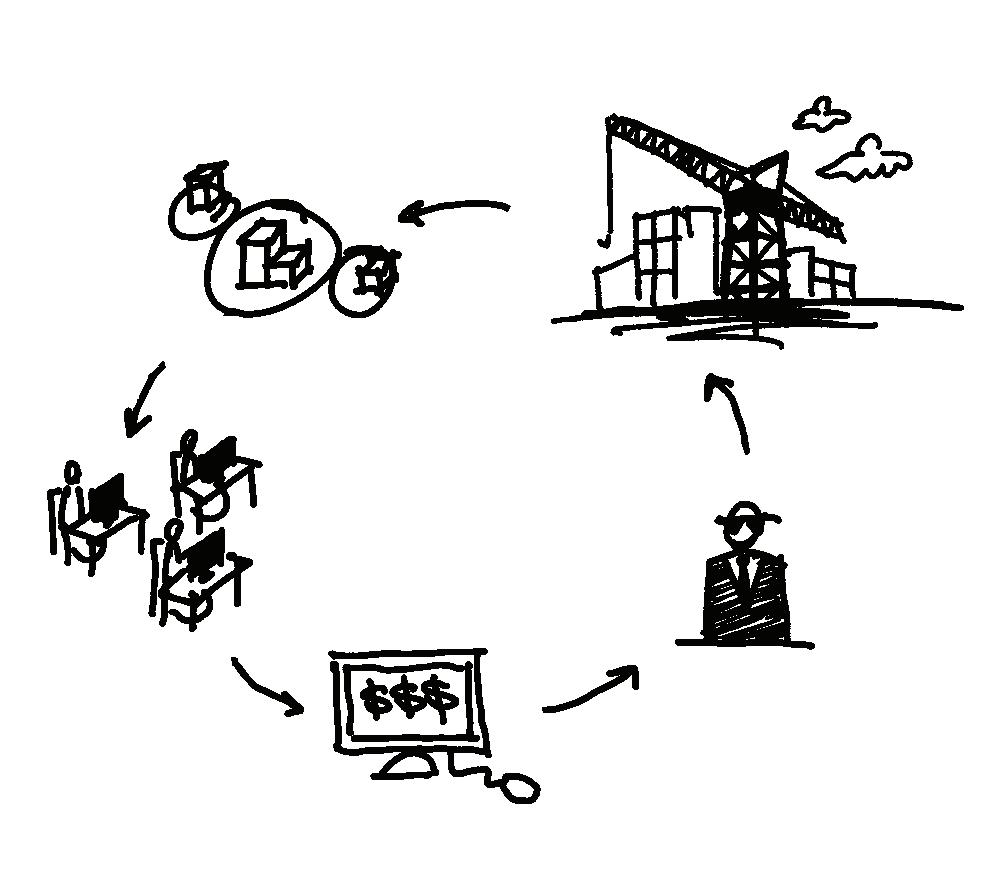

Conventional grocery system Revised distribution model

All “international” products made distinctly foreign

Food products of global origin honored for cultural significance and made visible

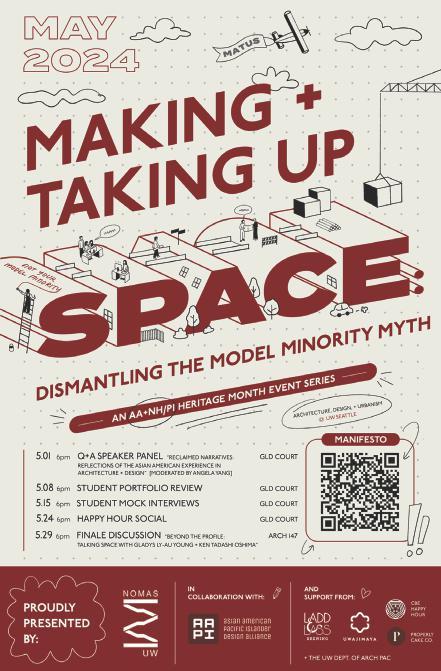

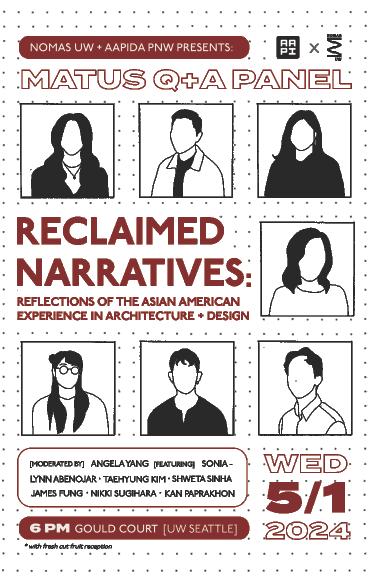

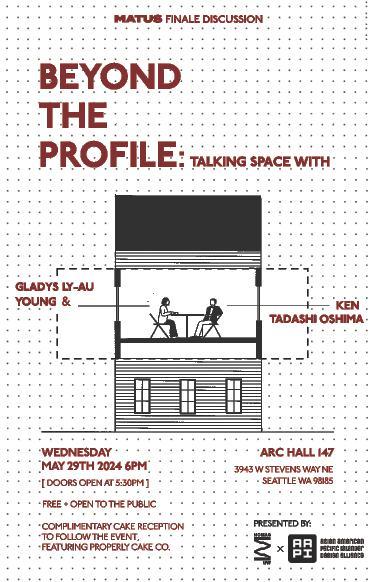

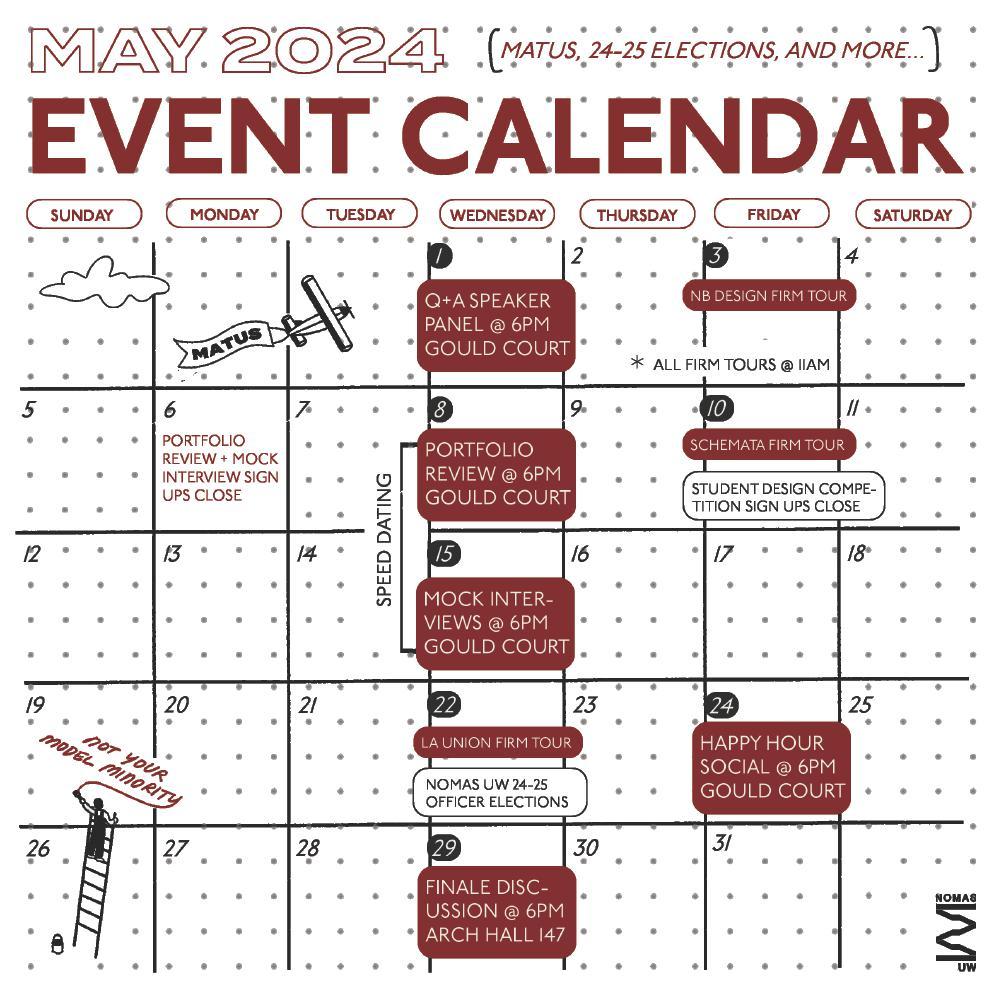

“Making and Taking Up Space: Dismantling the Model Minority Myth”, an event series in honor of 2024 May’s Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AA+NH/PI) Heritage Month, was founded by four architecture peers and I in response to growing diversity and changing student values in the University of Washington College of Built Environments (UW CBE). As young students of design, our collaborative group sought to reclaim narratives and assert our passions to make and take up space despite the model minority myth that has plagued not only AA+NH/PI communities, but all communities of color. While collaborating to plan 8 different events, I led the development of MATUS’s graphic identity with the goal to express a spirited message of empowerment through text, color, and illustration.

Each MATUS event was planned in detail, with different promotional graphics (created by myself with weekly design critique/input by co-collaborators and NOMAS UW) so audiences could catch on to their distinct messages. For example, the ideas of diverse experiences (related to Q+A panel) and “behind the curtain” stories (related to finale discussion) inspired the illustrations of event posters. Merchandise, such as drink glasses and tote bags, were designed with similar motifs so individuals could remember and celebrate MATUS beyond a single month.