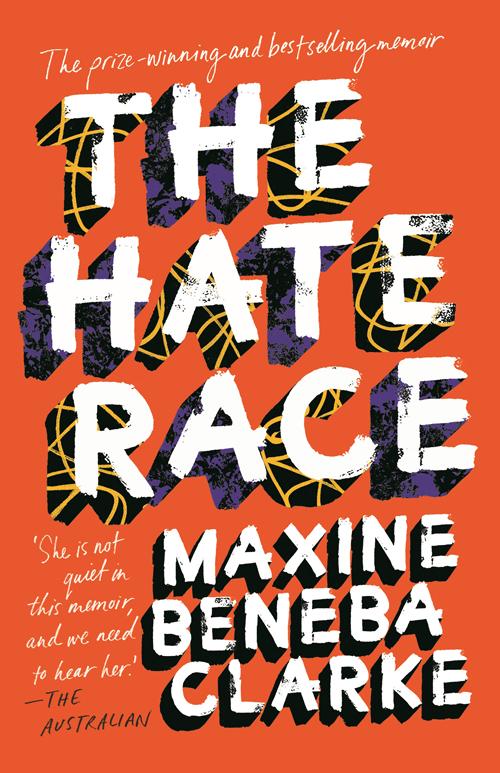

PROLOGUE

DRIVING SLOWLY ALONG the artery of North Road, you can track the varied and changing demographics of Melbourne’s inner east. Palatial beachfront mansions and Art Deco apartments slowly give way to overlarge suburban houses. This is the east side of the city –where everything is two-point-five-kids-and-a-four-wheel-drive respectable, un-grungy all the way from Elwood to Huntingdale.

I’m walking along the short stretch of North Road that takes me from my own street in the white-picket-fence, increasingly gentrified suburb of East Bentleigh to my son’s primary school, one of three primary schools within walking distance of our home. I’m bloody tired. In fact, I’m probably looking forward to the school holidays even more than my son. He’s five and a half, and in his first year at primary school. For the last ten weeks, the poor little critter’s been absolutely smashed with tiredness come three-thirty pick-up. He shuffles out of school babbling and incoherent, offering nonsensical insights into various parts of his day: which kid fell over and skinned their knee during snack time, what flavour icy pole he chose at lunchtime with a full analysis of exactly why.

I’m wheeling my chubby five-month-old daughter along in her pram, looking forward to two weeks of pyjama-clad French toast mornings, museum trips and non-school-assigned reading.

‘Fuck off, bitch.’ The voice comes from behind me.

Exactly what I don’t need this afternoon is to be caught up in someone’s very public domestic.

‘Go on, fuck off.’

An uneasy feeling runs down my spine. This isn’t some domestic dispute: he’s talking to me. I’m unprepared, stop for a second, startled. It’s been about ten months since I was openly abused on the street by a total stranger. Since moving from Sydney to

Melbourne four years back, it’s never happened so close to my home.

The white ute draws level with me, slows down. It’s around three and the traffic on North Road is almost bumper to bumper. The car behind the ute slams on its brakes.

‘Fuck off, you black bitch,’ the ute driver screams from the open window. ‘Go on, fuck off. You make me sick, you fucken black slut. Go drown your kid! You should go drown your fucken kid. Fuck off, will you!’

Suddenly, there’s that chest-tightening feeling. That heart-in-mythroat, pulse-in-my-temples fear. The dry tongue. The gasping for breath. The nakedness. The remembering how it can happen anywhere, at any time. That can’t-think freeze. I am four years old, on my first day of preschool, standing underneath the mulberry tree, watching another little girl’s lip curl up with disgust as she stares at me. I am slouched down on the high school bus, head bowed, pretending not to notice the spit-ball barrage, the whispered namecalling.

My baby daughter thinks it’s funny. She’s chuckling, kicking her fat legs in glee at the loud voice coming from the vehicle. My knuckles are gripping the pram so tightly that the fingertips on my right hand have started to go numb. I look straight ahead, trying not to pick up the pace too much. The turn-off for my son’s school is a few hundred metres away. Another horn beeps. It’s the motorist behind the ute. I know the ute driver’s a young bloke, but I don’t want to look any closer. That’s part of what he wants.

‘Fuck off, blackie! Why don’t you just piss off? Bitch! Go the fuck back to where you came from, back to your own fucken country, nigger!’ He puts his foot on the accelerator and the ute screeches away.

I round the corner. Off the main road, I stop the pram and sit down on somebody’s tan-brick front fence. I can’t breathe properly. Tears are streaming down my face. I’m heartbroken, but also angry –not at the young ute driver, at myself. For letting this upset me. I should be used to this. I should know better. I’m also thankful my daughter isn’t a few years older, old enough to understand. I’m thankful my five-year-old wasn’t walking with me. I’m also thankful

the bloke in the ute couldn’t see the baby: her beautiful caramel skin, her to-die-for medium brown eyes, the light brown ringlet curls starting to dance their way across her little fat head. I know that this, too, might add fuel to the fire.

I compose myself, check my watch. The school bell rings in five minutes. I have to make up time. The mother of a boy in my son’s class falls into step with me.

‘How’s your day been?’

I’m still shaking, can’t answer her for a moment.

‘Um. Sorry I’m I’m a little bit uh Sorry Some guy driving along the street just started yelling at me. I’m feeling a bit out of it, actually …’

‘Just now? What happened? What did he say?’

‘Go back to your own effing country. You know the drill.’

I can tell she doesn’t. She’s standing there with her mouth gaping open in shock. I feel embarrassed now, ashamed I even brought it up.

‘I’m okay. Don’t worry about it. It just hasn’t happened for a while, that’s all.’

She starts to stammer something, then looks away uncomfortably. ‘That’s horrible,’ she offers finally. ‘I’m so sorry. I don’t know what the hell gets into people. That’s just awful. I’m sorry you had to go through that.’

I don’t want sympathy. I want to un-hear what I just heard, unexperience what just happened. If racism is a shortcoming of the heart, then experiencing it is an assault on the mind. You should go drown your fucken kid! Go the fuck back to where you came from, nigger. The cumulative effect of these incidents is like a poison: it eats away the very essence of your being. Left unchecked, it can drive you to the unthinkable.

It’s day five of the school holidays and we’ve barely left the house. When we do go out, to the shops or park, I can feel all the white people looking at us. I don’t want to have to consider what they’re probably thinking.

I’m supposed to take my son to a theatre show tomorrow He’s been looking forward to it for over a month: grins widely every time he remembers the upcoming excursion. The kids’ theatre show is, quite frankly, my idea of hell. My son knows that, which is why he takes so much pleasure in asking me if I’m excited about it.

‘Are you looking forward to the show tomorrow, Mum? I can’t wait!’

‘I’m so excited about it, I think I’m going to wet my pants,’ I respond, deadpan.

‘Why do I have to have such a silly mother?’ He falls over onto the carpet in hysterics, rolls his eyes.

I do feel like I’m going to wet my pants. It’s only been one term, but I don’t want my child to go back to school. I remember, my god, so well, the unforgiving playgrounds of my youth.

I don’t ever want to go out of our house. We might sit next to somebody who racially abuses us under their breath. The usher who tears the ticket might wipe their hands on their shirt in disgust after their fingers brush mine. The server at the snack bar might spit on our hot chips during interval. Somebody might tell me I should drown my own child.

Go back to your own fucking country.

This is my country, that much I am sure. I was born here, the child of Black British parents, in 1979, in a maternity ward of Sydney’s Ryde Hospital, on the stolen land of the Dharug people. My early ancestors were part of the Atlantic slave trade. They were dragged screaming from their homes in West Africa and chained by their necks and ankles, deep in the mouldy hulls of slave ships, destined to become free labour for the New World. If slaves were lucky, they died in transit to the Caribbean – bodies thrown overboard, washed clean of the blood, sweat and faeces in which they’d spent most of the harrowing journey. If they survived, they found themselves in a nightmare: put to work on the harshest plantations on earth, overseen by some of the cruellest masters in the history of the Atlantic slave trade. I am the descendant of those unbroken.

I carry proudly the burnished mahogany of my ancestors, though my Africa is four continents, four hundred years of slavery, one forced migration, two voluntary migrations and many lifetimes ago.

So long ago, in fact, that Africa herself might not now recognise me. So long ago that when I die, the fierce, fertile continent of my origin might refuse my spirit entry: the wooden pombibele might refuse to drum out my funeral rites. Mwene Puto, the Lord of the Dead, with long thin fingers as blond as bone, might refuse to appear and claim me, and my soul will be spirited south, away from my first motherland, past the open corners of Yemen and Somalia and out into the Indian Ocean, sent packing back to Australia, the land of my birth: my country – my children’s country. The only home we know.

Part One

1.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE time show my father in flared cords and tightly fitted shirts, his oval-shaped afro rising high above his head. There’s my drama-school-graduate mother, dainty and petite in velour turtlenecks and large wooden earrings, sparkly eyed and beautiful. Both of them are Black Britain to a tee: full to bursting with seventies hippie hopefulness. And my god, their youth. Over the years, snippets of the journey, of how your father and I came to Australia, have been told and retold. The margins between events have blended and shifted in the tell of it. There’s that folklore way West Indians have, of weaving a tale: facts just so, gasps and guffaws in all the right places – because, after all, what else is a story for?

There are myriad ways of telling it. The young black wunderkind, the son of a cane-cutter with the god-knew-how-it-happened firstclass degree in pure mathematics. Gough Whitlam, the sensible new Australian prime minister, dismantling the last vestiges of the White Australia Policy. That fool English politician Enoch Powell, and his rivers of blood anti-immigration nonsense. Two academics arranging to meet at London’s Victoria station. A Qantas jumbo jet. My parents’ unforgettable arrival in Sydney, at the Man Friday Hotel.

When I gather the threads in my fingers, this is how I’d have it weave.

It’s 1973. My father’s parents, Louella and Duncan Clarke, gaze across the hall of the local West Indian Club to where their first son holds court among the neighbourhood well-wishers. Louella clenches her eyelids tightly shut, feeling she might well cry with pride. Then, slowly opening her eyes, she grips her husband’s worn, tired hand in hers.

‘Lou, all de trouble. It wort it. It well wort it, woman.’ My grandad turns to his wife, a smile dancing in his bloodshot eyes.

‘What trouble ye talkin bout, Dun?’ she would have asked, in that cheeky tone she often used to rile him.

Duncan would have looked at Louella then, well shocked. Surely the woman wasn’t losing her mind just yet. Surely she hadn’t forgotten the battles of these last thirty years. The wretched threeweek boat journey from Jamaica. Living in freezing English boarding houses. The riots. The early days with those fascists stirring up the streets so that no black person felt safe walking them day or night.

But then Duncan would have noticed, in the corner of Louella’s eye, the twinkle which had first drawn him to her, all those years ago back in Jamaica.

‘Ye never had any trouble wid dat chile yeself,’ Louella would’ve continued. ‘If mi do recall, was mi who, screamin an cussin so loud all-a Kingston musta heard, did squeeze de bwoy outta parts dat surely nat meant fe a likkle head wid a brain in it dat big te pass through!’

Duncan, he’d have laughed then. He’d have let echo one of those deep belly rumbles of his. Louella, she’d’ve joined him, chuckling away. They’d have sat together – I’m sure of it – side by side, watching the first of their four children celebrate his success.

My father, Bordeaux Mathias Nathanial Clarke, was the first-born son of two Jamaicans, and named with all the pomp and expectation that entailed. Born in the Jamaican capital of Kingston, Bordeaux migrated to London with his parents at nursery school age. At twenty-five, he’d just become one of the first in his community to secure a degree from a British university.

Thirty years since the first wave of mass migration to England from the Caribbean, Black London was finally coming into its own. The anticipation could be felt in the salons, pubs and jerk chicken take-outs of Tottenham, Seven Sisters, Brixton, Walthamstow and the city of Birmingham.

If ever the loyalty of Britain’s far-flung Africa-descended subjects left scattered over the West Indian islands post-slavery was in question, the voluntary participation of tens of thousands of young black men and women in the Second World War effort had put paid to these misgivings. By 1945, officially at least, West Indians were

seen as ‘true’ citizens, whose patriotism was no longer open to scrutiny: theirs was an allegiance which had been sworn in blood.

British immigration officers posted throughout the Caribbean to encourage migration to fill post-war employment shortages were very persuasive. My Jamaican paternal grandparents and Guyanese maternal grandparents lined up for passage to build a new life for themselves and their young families in a place where – they were assured – the streets were paved with gold.

Black people had lived in England, in sparse numbers, since slavery, but in 1945 the Empire Windrush ship pulled into the Tilbury docks carrying over four hundred and fifty Jamaicans. Those on board – mostly men – had braved the same Atlantic Ocean the British had used to forcibly transport their forebears to the plantations some hundred years back. They came brimming with hope; searching for work; thirsting for the better life Britain would surely offer.

So began the slow parade of ships from the islands to the British motherland. At the conclusion of each weeks-long voyage, hundreds of tired, hopeful passengers were unceremoniously dispersed into the grey ports of London. Often ostracised by their neighbours, belittled by their colleagues, short-changed by their employers and extorted by their landlords, the new arrivals moved from boarding house to boarding house, day labour job to day labour job, constantly on the move through the drab outer suburbs of the capital. The new West Indian arrivals desperately searched out their countrymen in the cold, lonely corners of a country which turned out to be nothing like they’d dared to dream.

But here, not thirty years later, Bordeaux Clarke had become living proof of the opportunities afforded by the struggles and sacrifice of his parents’ migration. Here was the accomplished young black man every West Indian father wanted their knock-kneed little brown boys to become.

This is how I’d have it sing.

‘Ow, Dad. Ow!’ Dragged by the ear by his Jamaican father across the room to meet the new graduate, a small black boy pushed his

lips out into a stubborn pout and scowled. Bordeaux stifled his amusement and tried to appear a suitably impressive role model for the poor kid.

‘See dis man?’ the boy’s father, a respected neighbourhood elder, asked.

‘’Course I see im, Dad – ’e’s standin right in fronta me!’ The boy squirmed out of his father’s grasp.

‘Chile, ye nyah know what’s good fe ye. Show de man some respect or me gwan give ye a lickin!’ The man cupped his hand under his ten-year-old’s chin, raising the boy’s face up towards the statuesque scholar standing in front of them. ‘Dis young man somebody ye should aspire te be, bwoy,’ he lectured. ‘Kiss de man’s feet. Go on – bend down right now, an kiss de man feet.’

This is a tale my Grandad Duncan once told me, to demonstrate how much respect my father’s education had commanded. That West Indian way, of spinning a tale. Bordeaux, if I know it right, would have shifted uncomfortably from foot to foot, while the serious man pointed down towards his black Dr Marten boots. Bordeaux, he’d have laughed, patting the nervous kid on the shoulder and waving the pair away, the older man still looking respectfully back over his shoulder.

Since the Clarke family’s arrival in London from Jamaica some twenty-three years before, it had been Bordy this and Bordy that.

‘Bordy’s teacher, dem nyah like im. Dem give de bwoy grief jus cause de chile too gifted.’

‘Bordy, im so smart, im really gwan meyk sometin of imself, ye know.’

If they hadn’t heard enough praise about the boy from the very proud Louella and Duncan Clarke over the years, all of Tottenham now appeared to have concrete validation of what the couple had been preaching: that their first boy, Bordy, was nothing short of brilliant. That in England, if a black child worked hard enough, any dream was achievable.

Bordy had paper. This wasn’t just any old piece of paper Bordy held, but a PhD from an English university. A PhD in not just any old subject, but mathematics. Tssssk. Any old Montego Bay layabout knew that was a damn hard gig.

To boot, Bordy had also recently married Millie and Robert Critchlow’s middle daughter, Cleopatra, the young Guyanese actress who’d recently graduated from the National School of Speech and Drama. A beauty, she was, and Bordy, with his soundwaves and equations and geek-glasses, with his numbers and slightly abrasive manner, he’d somehow nabbed her. God only knew how.

There had always been problems in England for people like Bordy and Cleo. For West Indians, that is. In the summer of 1958, fours years after the arrival of the Empire Windrush, random violent attacks on black people on the streets of London escalated over the course of two weeks, culminating in race rioting on the streets of Notting Hill, in West London. Hundreds of white folk – many of them working-class teddy boys spurred on by involvement in fascist antiimmigration groups – stormed the streets, attacking the houses of black immigrants.

Ten years later, in 1968, around the time Bordy and Cleo were thinking about studying for their A levels, the world seemed to be in the midst of a race crisis. In the United States, civil rights leader Martin Luther King was assassinated, leading to widespread race rioting across the country. In South Africa, the movement against the apartheid system of racial segregation had been temporarily stifled by political repression. At home in England, a politician named Enoch Powell gave a speech at the Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham. Hair slicked back, black jacket tightly buttoned, sparse moustache jumping over thin, pursed lips, he declared:

‘In this country, in fifteen or twenty years’ time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man’ It almost passes belief that at this moment twenty or thirty additional immigrant children are arriving from overseas in Wolverhampton alone every week … Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow …

Powell warned of English wives in childbirth turned away from overcrowded hospitals, of white children unable to obtain places in

local schools, of neighbourhoods changed beyond recognition. In the general election of 1970, the centre-right Conservative Party of the United Kingdom won an unexpected victory.

Despite these racial tensions, migrants of colour and their Britishborn children had truly made London their home. In Tottenham, a few island grocery shops had sprung up: aisles stacked with jerk seasoning, tinned ackee, smoked salt fish and bruised plantains. The occasional black hair salon could be seen, with racks of multicoloured hair-weave pieces, giant tubs of sticky dreadlock wax and netted sleeping caps spilling onto the footpaths. After twenty or so years, a strong black community was being forged.

Following his graduation, Bordeaux was offered a teaching post at Nottingham University. The post-war boom ground to a standstill. The economic climate in England started to falter. The country slid into recession. One of Bordeaux’s university colleagues was about to return home to Australia to take up a teaching post. The Australian man’s wife got on well with Cleopatra and the two couples had formed a solid friendship. The Australians advised Cleo and Bordy to consider moving to Australia.

‘Leave Great Britain,’ they urged. ‘Jump ship before it sinks.’

Bordy and Cleo knew Australia was a wealthy country colonised by the United Kingdom. They knew that Australia was a nation founded on the genocide, degradation and dispossession of black Indigenous inhabitants. They knew that, for many decades, Australians had lived under the White Australia Policy – which openly preferenced white migrants and excluded migrants of colour. The White Australia Policy was a system that, in 1919, Australian Prime Minister William Morris ‘Billy’ Hughes hailed as ‘the greatest thing we have achieved’. Decades later, after the outbreak of the Second World War, then Australian Prime Minister John Curtin had proclaimed: ‘This country shall remain forever the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race.’

But the young Australian couple assured Bordy and Cleo that things were changing. The White Australia Policy had been dismantled. The visionary new prime minister, Gough Whitlam, had been elected on a platform of increased immigration and land rights

for Indigenous Australians. Excitement was in the air Change was coming. On their return to Australia, the young couple started posting job openings back to Bordeaux, for positions in New South Wales, where they would be within reach to help the young black couple settle in to their new country.

Months ticked by without news. Upheaval within the Whitlam government had caused a freeze on government job appointments. Cleo and Bordy could make neither head nor tail of the ruckus, but it appeared Gough Whitlam, the man their friends had championed as the mandated architect of the new Australia, was no longer the prime minister. The silence suddenly broke, and a reputable university in Sydney’s west contacted Bordeaux to let him know they were seriously considering him for a position. He was required to send further identification, including a photograph.

Aware of the lack of diversity in Australia, Bordy strategically declined to include a photograph with his documentation. Weeks later, my father received notification that a professor from the Australian university happened to be visiting London, and would like to meet up with him to discuss the job offer The two academics decided Victoria station would make a good initial meeting point.

This is how my mother tells it. This is how the story hums.

‘How will I know who you are?’ the professor asked my father.

‘I’ll be wearing a pinstriped suit,’ Bordy replied carefully, ‘and carrying an umbrella.’

‘I’ll be carrying a red Qantas bag,’ the Australian professor said.

The day of the meeting, Bordeaux Clarke, dressed in his pinstriped suit, nervously kissed his young wife goodbye and headed to Victoria station. The train pulled in. Businessmen in dark suits, women pushing prams, groups of teenagers and families with suitcases filled the platform. The black man wearing his best pinstriped suit and carrying a large umbrella greeted the Chinese Australian professor carrying a red Qantas bag.

That folklore way of weaving the tale.

No-one was more surprised than Louella and Duncan Clarke when they found out that their brilliant young son had applied for a position at a university in Australia. As far as anyone knew, Australia was some bottom-of-the-earth island that had banned black folk from coming in for as long as possible, after shooting dead most of the ones they found there in the first place.

News of the newly married couple’s impending migration was the talk of black Tottenham.

‘Ye hear dat Bordy, Lou an Dun’s bwoy, im teykin im new wife Cleopatra to anudda country?’ one customer would remark to another down at the West Indian goods shop on the corner of West Green Road.

‘Nah, me nyah know dat. Ye serious? Where de two-a dem goin?’

‘Dem gwan Austreeyleea.’

‘Where dem gwan?’

‘Austreeyleea.’

‘Austreeyleea? Where de hell dat?’

‘Me nat sure. Somewhere at de bottom of de world. It British rule.’

‘Black folk dem live down dere?’

‘Is anyone guess!’

‘Why dem gwan dere?’

‘Bordy im get teachin job in de university dere.’

‘Me thought im already got teachin job up Nottingham?’

‘Well, im own fadda Duncan tell mi dat im leavin de country an goin dere.’

‘Lawd! Dat damn shame.’

I can see them now, the gossipmongers, shaking their heads in confusion as the shop attendant rang up their items.

This is how I tell it, or else what’s a story for.

2.

IN 1976, AFTER twenty-nine hours of travel, nine cardboard-consistency meals and two sleepless nights, racked with excitement, anxiety and anticipation, Bordeaux and Cleopatra Clarke arrived at Sydney International Airport. They disembarked wide-eyed from the enormous kangaroo-stamped jet, in the company of a hundred other tired travellers.

Their first impression of their new country was the sheer brightness: a luminous southern hemisphere sunlight they had never seen before in an impossibly clear blue sky. It was glorious, that light, as if they’d stepped suddenly out of grey, dreary Kansas into the motion-picture technicolour of Oz. Terra Australis. Endless possibility.

The ride out to Chatswood was longer than Bordy and Cleopatra had anticipated. The sparsely populated suburbs stretched as far as the eye could see. Large square houses stood on enormous blocks of clipped green grass, bordered by picket fences. The driver snuck curious glances at the well-dressed young black couple in his rearview mirror as he drove to the North Shore address they’d given him.

The car eventually slowed to a halt outside the hotel where the university had booked a room for my parents until more-permanent accommodation could be found. The excited but jet-lagged couple stood in the driveway, looking up at the hotel. Cleopatra shook her head in disbelief, leaned over and checked the number on the hotel letterbox against the address they’d been given. The couple locked eyes, shocked. The sign above the entrance proclaimed: Man Friday Hotel. They both knew Man Friday well. Man Friday, the Carib cannibal turned loyal servant of Robinson Crusoe. Man Friday the faithful who, in Defoe’s novel, loved his master so fiercely that, after serving the shipwrecked man on the island, he followed Crusoe back to England for a lifetime of willing servitude.

Bordy reassured his wife, as they hauled their suitcases from the back of the vehicle and the taxi slowly pulled out of the driveway. I can hear them now, those bogongs of doubt beginning their dustywinged beat beneath my mother’s rib cage. What kind of country is this? Cleo glanced quickly over to the street sign at the end of the road. Help Street it read, the white letters screaming out against the dark background.

Wishing to celebrate their arrival with the obligatory English wine and cheese before finally catching some sleep, Bordeaux and Cleopatra were directed to the local bottle shop by wary hotel management. The man behind the counter immediately directed the young black couple to the cask wine section. Bordeaux and Cleopatra, who had never seen cask wine before, peered through the holes in the cardboard casks to inspect the foil bags which appeared to contain the wine. Not realising they’d been directed towards the cheap, nasty booze assumed to be their consumption of choice, they selected one of the more expensive casks and headed back to the counter.

In the adjoining Franklins supermarket, wooden crates and cardboard boxes were stacked from floor to ceiling, creating makeshift aisles which rendered navigation of their trolley an Olympic feat. Ugly black block-writing screamed the names of smallgoods across white, plastic packages. Cleopatra reached instinctively for one of the few coloured packets in the cheese section of the refrigerator. Bordeaux caught his young wife’s hand mid-air, recoiling in shock. In giant blue lettering, the word COON leered at them.

Again, those beasts of doubt, waking and turning, deep in my mother’s gut. What have we done? What have we done?!

During Cleo and Bordy’s week-long stay at the Man Friday Hotel, there was no forgetting the ill-omened name. The distinctive hotel logo danced across pristine white towels, napkins, sheets and curtains: an embroidered trail of tiny black footprints, exploratory smudges on uncharted white territory.

In another sign the fates were stacked against them, the couple who had urged Cleo and Bordy to migrate to Australia made an unexpected move to rural South Australia to take over the family

farm. Their time left in New South Wales overlapped just a few months with Bordy and Cleo’s arrival, and then the young black couple found themselves well and truly alone.

Eighteen months after their arrival in Australia, my parents settled in the small outer Sydney suburb of Kellyville. Located on the rural fringe, houses in the area were comparatively cheap, and the sleepy suburban village was within commuting distance of my father’s teaching job at the university. Then, too, it was the kind of place the young couple envisaged they might start and raise a family.

The suburb was named after Hugh Kelly, who’d arrived in New South Wales as a convict in the early 1800s. On his release, Kelly amassed land in the area along with a pub, the Bird in Hand, which had stood on the intersection of two main roads: Wrights and Windsor. When Kelly died, around 1884, the land of his estate was divided up into farmlets and the area became known as Kellyville. Kellyville had remained semi-rural until the mid-sixties, when roughly a thousand homes were developed in an area that became known as ‘the village’.

Kellyville village was a cluster of mostly brick houses in the style of classic seventies suburbia. Three bedrooms. One bathroom. Carport or single garage. Concrete driveway. Carefully edged yard. In summer, lawn sprinklers were on constant rotation. On winter mornings, white frost sheeted the buffalo grass. The village was largely populated with young single-income families, or older empty nesters whose families had lived in the area for generations. On the village outskirts lived an assortment of city dropouts in caravans or small fibro houses backing directly onto bushland. Then there were the market gardeners, who largely kept to themselves, including a small number of Maltese, Italian and Chinese immigrants who’d brought one or two acres of cheap land and worked it for their living.

In Kellyville village everybody knew everybody. Bordeaux and Cleopatra Clarke, the young black couple who’d purchased the little blonde-brick house next to old Betty and Jack’s place on Hectare Street, were the most bizarre of blow-ins. They weren’t like the market gardener migrants; they’d bought inside the village, right in

the thick of things. Bordy could be seen mowing the lawn of a Saturday morning, thick glasses fogged up with perspiration, black muscles shining from underneath his dark blue Bonds singlet, striped terry-towelling sweatband circling his afro. His tight denim shorts raised the eyebrows of many a passer-by. Then there was Cleopatra, ever-stylish in her head wraps, earrings and boots. ‘An actress,’ people whispered to each other. ‘That’s what old Betty heard her say.’ And their English, that was perhaps the biggest oddity of all: so perfectly spoken. That was not how the locals expected black folk to talk. Heads were scratched. Fences were stared over. Gossip was spread.

There was history in it, though, this Africa-descended migration, if the new arrivals or their neighbours had only known. Among the convicts brought on the First Fleet to help build the new colony were several men of African descent, some likely hailing from the West Indies. On their release, these settlers of colour bought land, and brought up families, in Pennant Hills, not far from Kellyville. Over time, because of its inhabitants of colour, the area became known as Dixieland – named thus by white settlers after the region in America’s Deep South which incorporated Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and the eight other states of the slave belt which made up the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865. At the time of Bordy and Cleo’s arrival in Kellyville, though, the locals were likely unaware of this history. For many of them, Bordeaux and Cleopatra Clarke were the first black people they’d ever seen up close.

In these improbable surroundings, Bordy and Cleo’s family grew. First came a daughter, Cecelia, in 1978. Eighteen months later came their middle child – me. And in 1982 a boy was born, Bronson. Their family was now complete.

By the early 1980s, race riots had again erupted across the UK, as a result of British police officers abusing stop and search laws to racially profile and unfairly target ethnic minorities – namely, young black men. Race relations, under the United Kingdom’s new conservative prime minister, continued to be fraught. But none of this mess touched the little brick house on Hectare Street. The home

Bordeaux and Cleopatra had made was packed with love, laughter, playdough and pride.

So went my early childhood. This is how it sang.

Hectare Street sat at the very edge of Kellyville village. Down the end of our road, some eight hundred metres or so from our front door, was a small creek. The rickety bridge that crossed it served as the border between the village and the small acreage properties beyond.

In summer, us children would troop denim-shorted and hypercolour t-shirted with Mum or Dad down to the creek, clutching glass jars or empty ice-cream containers. We’d scoop up the clear, shallow water until we had a sufficient number of wriggling black tadpoles. The tadpoles were then kept on the back veranda of our house. Sometimes we’d rear them long enough for their heads to fatten and their two back legs to develop. Inevitably, though, there would be some kind of mishap. The bucket would be accidentally kicked over, or an unexpected downpour would cause the containers to overflow, and that would be the end of our endeavour to hand-rear frogs.

On weekends, we would drive down the back of Kellyville and buy fruit and vegetables from the market gardeners. Out in the small fields, workers would be stooped low to the ground, triangular straw hats or water-soaked head wraps protecting them from the unforgiving sun. Out front of each small allotment was a makeshift stand – often just a few plastic milk crates stacked together – loaded up with freshly picked tomatoes or strawberries. Each had a cardboard sign with the price and a tin honesty box.

To add to the eccentric mix of the outer margin of the city, peppered among the standard three-bedroom blonde-bricks were Federation-style houses, all complete with chimneys but missing television aerials. These were the houses of the Exclusive Brethren, a fringe religious group whose Australian headquarters happened to be in the village. Their windowless church hall was perched righteously on the hill next to the local Catholic primary school on

Hectare Street, while our unwaveringly atheist family lived at the bottom of the hill. Fitting, if amusing, geography.

Though our lives were worlds apart, I empathised with the Brethren children from an early age. They, too, had been thrust unexpectedly into this close-knit village, and were highly visible due to their different behaviour and old-fashioned attire. On Friday nights, the Brethren were duty-bound to proselytise, the head preacher (inevitably a tubby-around-the-middle ageing male) ranting about hellfire and damnation to bemused families queuing for fish and chips outside Nick’s Milk Bar on the Windsor Road shopping strip. Young Brethren women, skirts down to their ankles, cream blouses buttoned tightly at their wrists and necks, hair in rag curlers underneath their compulsory scarfs in preparation for the gathering later that night, provided a chorus of amens and praise the Lords.

‘The Lord can see everything, sinners.’ The preacher would point an accusing finger at a King Gee–clad man ferrying newspaperwrapped hamburgers home to his young family.

‘Amen, the Lord sees all!’ the Brethren women would murmur in agreement.

‘The Lord hears everything, sinners!’

‘Amen, brother.’

‘Everything!’

‘Oh yes, the Lord, he surely hears!’

My toddler brother, Bronson, my already-at-school older sister, Cecelia, and I would listen to the dire warnings drifting in through the open window of our family’s white Ford Falcon as we waited for Mum to hurry back from the milk bar with our fish and chips.

‘Everything! The Lord hears. Everything!’

What the Lord was supposed to have heard and disapproved of in the ultra-conservative bible belt of Kellyville was anyone’s guess.

IN 1983, AT the age of four, I started at the local preschool. Kids attended for several half-days a week. Clag glue, poster paint, naptime mats and morning-tea fruit were the order of the day. The play yard was lush and green, and contained play equipment fashioned out of wooden logs and old car tyres. I’d suffered tantrum-prompting envy at my older sister Cecelia’s entry into ‘big school’ the previous year, and had been eagerly looking forward to a kingdom of my own. I was also happy to escape temporarily the curious crawling expeditions of my one-year-old brother.

But in every Eden lurks a serpent, and in this paradise, the joykiller came in the form of a little girl named Carlita Allen. Tiny, freckle-faced, ash-blonde, rough-around-the-edges Carlita looked like she’d just stepped out of a glossy illustrated copy of Seven Little Australians. She was a Judy type: hardy, resolute, bold. The youngest in a family of three girls, she lived on one of Kellyville’s bush properties. Carlita was talkative and ballsy. By all accounts, we should have fast become friends. But from the moment she laid eyes on me, Carlita Allen decided she didn’t like me, and Carlita Allen made it known.

As the excited gaggle of four-year-olds lined up near the mulberry tree for our first day at preschool, Carlita Allen looked me up and down. Hand still clutching her mother’s, she examined me from head to toe. I stared back hopefully, waiting for a verdict to register on her face. Her right eyebrow slowly levitated into her forehead. She raised her right hand to her hip. Finally, a haughty sneer inched its way across the upper left corner of her mouth.

Carlita Allen leaned towards me. ‘You,’ she whispered loudly, ‘are brown.’

It wasn’t as if I hadn’t realised this very obvious difference between our family and almost all of the other people we knew. My

skin colour was simply a concrete matter of fact, much like the sky was blue. Carlita was right: I was brown. But until that very moment, holding my mother’s hand under the mulberry tree’s enormous fanlike leaves, it never occurred to me that being brown, rather than the pale pinkish of most of my friends and neighbours, was in any way relevant to anything.

There lurked, in this small girl’s declaration, an implied deficiency. I was in no doubt that there was something wrong with being brown, that being brown was not a very desirable thing at all. I craned my neck to look up at my mother, who in turn looked over at Carlita’s mother. Mrs Allen shrugged and smiled. She picked a cotton thread from her peach-coloured blouse. She held the thread out between thumb and forefinger.

‘Children are so honest, aren’t they?’ The thin cotton wisp floated slowly down to the ground.

Tension crept into my mother’s body. She turned her head and started chatting to the mother on the other side of her. I turned the comment over in my head. On the one hand, Carlita had simply stated a fact. On the other, the way in which she’d stated it had raised a whole lot of questions I really didn’t understand or know how to go about constructing answers to.

Despite the palpable visual differences of our family, my mother did everything she could to integrate us into our surroundings. Our entire neighbourhood seemed to orbit around my Mum: the school canteen worker, the infants school gross motor volunteer, local fete organiser and office holder for the Kellyville Reciprocal Babysitting Club. The front room in our house seemed a hub for neighbourhood gossip and gatherings.

On rare occasions, though, I would see another side of my mother. We’d be somewhere local – in the Castle Hill shopping mall searching for winter pyjamas, or piling into the car one Saturday after Little Athletics, and suddenly Mum would freeze and her eyes would widen. Then all three of us kids would suddenly be unbuckled at the speed of light and bustled across the road, or shovelled into a shopping trolley and wheeled at great haste over to the other side of Kmart. We came to recognise the cause of these urgent movements:

my mother had spied, lurking conspicuously on the periphery of our whitewashed lives, another black woman.

My mother’s excitement at the prospect of a kindred spirit wasn’t surprising, given the vibrant black community from which she and my father had come. Here, in these rare encounters, was a glimpse of that other world she’d left behind. My brother, sister and I would hang around, bored, through exclamations and interrogations, as details were swapped, future visits arranged. My mother was always uncharacteristically quiet after chance meetings of this kind; she’d be absent-minded and aloof, as if her thoughts had wandered elsewhere. Cleo had agreed to move to the other side of the world so that my father could take up a lectureship at an Australian university. Mostly, she seemed at peace with the decision, but if ever she questioned her contentment with her new life, it would be in the days after her encounter with another black woman.

A visit would usually follow. Inevitably there’d be other black children present. Directed by the adults to go play outside, we’d stand gaping at each other: them and us – total strangers somehow expected to instantaneously bond as kin. As with any family gatherings of this kind, there were sometimes connections: firm friendships forged which continued into adulthood. Then there were those other encounters – in which, despite our mirrored knotty afros, confrontational pouts and way-too-smart-for-Aussie-children specialoccasion attire, the children we visited with were as unlike us as the local louts who threw stones at us down at the BMX track around the corner from our house. It made no sense to me to equate brown with kinship, but nor did I expect being brown to disqualify me from friendship with those who weren’t – those like Carlita Allen.

The two preschool teachers walked along the row of variously excited and woeful new arrivals, introducing themselves cheerily, gently prying chubby fingers from parents’ legs and waving away tearful mothers. As they did, I tallied up the other brown people I saw on a daily basis. There were a few family friends of varying shades, perhaps ten or so. I saw people on the telly sometimes, on the news, or in the running races my father liked to watch. The telly was black and white though, so I could never really be sure. I saw brown folks in the newspapers some mornings, little kids even. But they were