EDITORIAL

It is with great pleasure that I present this edition of the magazine, dedicated to the unique vision and remarkable journey of Klaus Mitteldorf. Our partnership spans more than three decades, built on trust, friendship, and admiration. Since the early days of Paparazzi, I have had the privilege of sharing Klaus’ work and closely following the evolution of his art, which consistently surprises us with its boldness and sensibility.

Over the years, Klaus has explored color, texture, and the female body in his work, creating an impressive body of photographic art that has helped elevate the standards of Brazilian photography.

This year, our collaboration welcomes a new, special chapter. Together, we took part in SP Arte with the launch of the book Klaus Mitteldorf MMXXV and an exhibition at Carcara Galeria, moments that reaffirm both the relevance of his artistic production and the strength of our shared work. The magazine now in your hands offers yet another space to celebrate this trajectory and share with the public the power of Klaus’ gaze, which continues to evolve without ever losing its essence.

I hope each page becomes an opportunity for discovery and for connecting with the intensity of his work. For me, as an editor and long-time partner, it is an honor to open this issue with the certainty that Klaus’ photography remains alive and vibrant.

Carlo Cirenza

NORAMI

The artist takes many years to discover themself, then just as long to find a personal and original language, then to master it, and still takes a lot of time to discover the technique, the material, and the medium to create his works.

Klaus Mitteldorf chose photography as his means of expression and did so completely. He not only used the modern, technological camera but also the entire possible array of tools: airplanes, helicopters, balloons, cars, motorcycles, bicycles — and he even takes photos on foot.

His photos clearly show that he is a globetrotter, one of the famous Marco Polos of photography. He belongs to the generation of photographers who are disciples of the photographic philosophy pioneered by Look and later Life magazines, now followed by GEO, the German version of Geographic Magazin.

But I think Klaus has two visions that define him as an artist, one of which is his athletic side; the other is his German heritage of great graphic tradition.

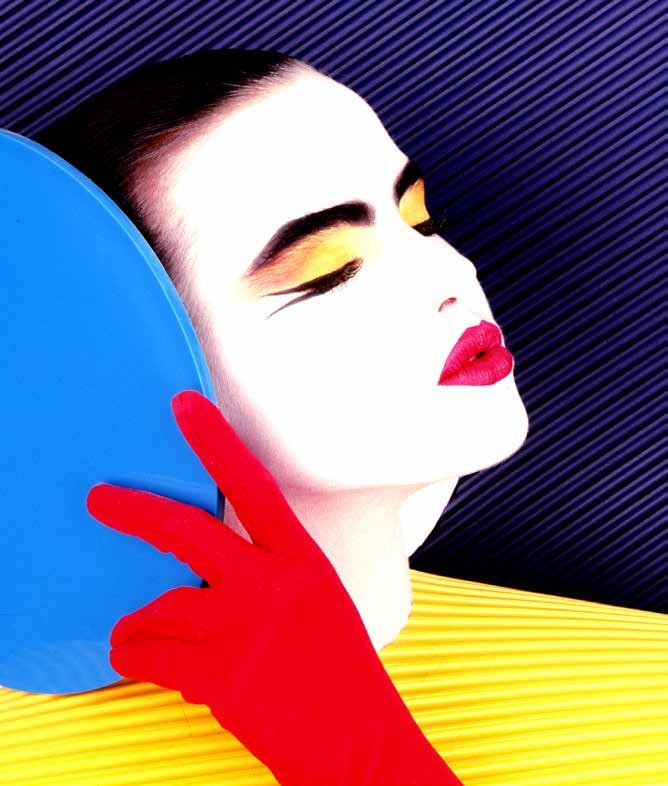

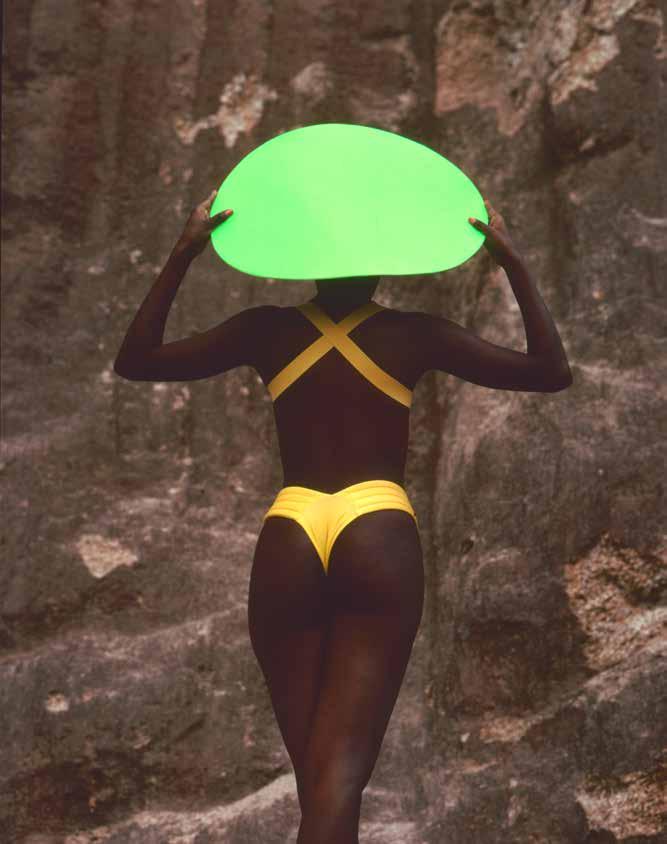

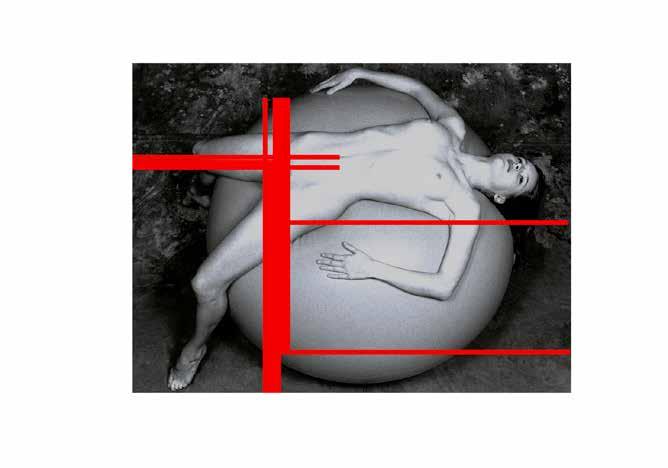

Klaus is a graphic artist, and I align myself with this side of him. If he were not a photographer, he would be a graphic designer, painter, sculptor or even a designer. He has a perfect sense of European graphic balance, like the masters Kurt Schwitters, Mondrian, Werner Schreib, or Hans Friederich, who dominate space and content with unique talent and balance. In fact, graphic art has always existed; it was the Germans who discovered it as a great form of artistic expression.

He uses the camera viewfinder like a modulated sheet of paper and frames his elements as a typographer frames his types. He is still possessed by the glamour of models posing on tropical beaches, but I find his elements — static — even more perfect, which, with a natural imbalance, are composed by his photographic talent.

He is an authentic Paulista, like thousands of others: tall

and blond, more like a German from Hamburg or Munich. He is the true product left by immigrants who came from all over the world to this fabulous state of Brazil: São Paulo.

This alone already says a lot, as they are serious, hardworking, and highly talented people. In fact, Klaus represents the new generation of German photographers settled in São Paulo, who left deep marks, always bringing new knowledge and new techniques.

Beyond this origin, Klaus has another quality: his Brazilian side. He is the bohemian Klaus, but not a common bohemian. He is a bohemian soaked in the day, intoxicated by the sun, the blue sea, and the deep skies. He wanders the world in search of a shape or a ray of light, a shadow or a color, without thinking, without earning, without time, without hour, without day, as a true bohemian does.

Klaus’ difference is that he couldn’t care less about this utterly commercial, monetarist, cold, and calculating world. Like any bohemian, he also needs money to buy film, lenses, cameras, pay for trips, and even for a drink now and then, “professionally.”

That is why he accepts commercial work, precisely to have the resources to fly, take his photos, his images soaked in delirious colors, which are intoxicating by the seaside. But, as you will see, Klaus is a very serious bohemian. His photos are never out of focus, nor blurry, and certainly never shaky. They are precise, straight, almost cutting. I believe this is his German, perfectionist side. This beautiful combination of a Brazilian bohemian and a German perfectionist is a perfect cocktail, with the following ingredients: a dose of sky, two doses of sea, a woman, a palm tree, two bananas, a yellow parasol, and a magenta scarf; put it all into the camera, click well, press the shutter, and there emerges a Klaus Mitteldorf.

Francesc Petit

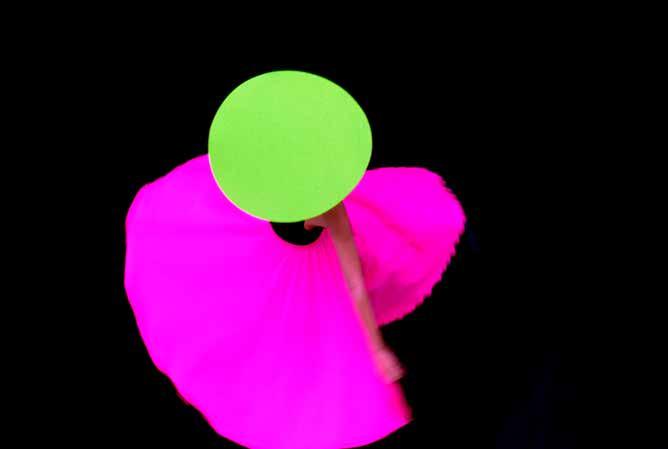

Norami (1989)

The Last Day of Spring

It all began with a bittersweet fragrance that filled the air. Then we were on the lookout. And soon they came, many of them, more than many. Like shadows, only of light. Amazons, passionately ardent – the females from somewhere.

The closer they came, the stronger grew the perfume; inebriated, we danced blindly among ourselves.

They didn’t want much, not even Power. In their otter fur bags – they Said – they carried old phantoms o four unconscious. It was this that scared us; it was that bewitched us. Supreme irony. It was with our own demons that the Amazons subjugated.

And when there was nothing more to do, because we had neither the strength nor the Will – and we were by then pure instinct – we gave ourselves up to giving them pleasure. It was in this way that they came once, twice and three times.

After the fourth time, we could no longer stand the Idea of waiting. We ran into the Forest, scaled the dunes, dived into the sea, looking for any sign f their arrival. And when the first fragrance was felt in the air, we started to howl. It was witchcraft. It was heat. Then we ran for our nests and pretended to be asleep.

The Amazons no longer needed to brandish their bags. We were already a conquered people. Now it was only a question f choosing the hammock, touching skins and enjoying the pleasure. When they went away, we would GO back to our normal daily life.

With the feeling that something very new was germinating both in their and our bellies.

Valdir Zwetsch

Last Day of Spring - Norami (1989)

A MATTER OF SENSUALITY

Lilo Wirth: Klaus Mitteldorf, how did it all start?

Klaus Mitteldorf: When I was twelve, I got my first camera. I found it immediately very easy to capture things with it and thus to make the world accessible to me.

L. W.: How did it go on from there - the life, the picture-taking?

K. M.: I tried to change the world a bit by means of photography. But it took me a long time to realize that it really worked. Then I was already 25. I was born in 1953. It wasn’t until 1978 that I really became serious about photography. Because I also had started to study architecture; that was in 1975. At that time photography was a side-line; I took a lot of photos at the beach, because I was a surfer as well.

L. W.: Exactly. You are a Brazilian ...

K. M.: I live in Sao Paulo. That is where I was born and where I grew up. That is where I spent the greatest part of my life. I travel a lot; I have been everywhere. And when I finished my architectural studies in 1978, I started to work as a photojournalist in various fields. In that way I photographed all kinds of things: shows and architecture, sports and many other things. I never worked as an architect, but my architectural studies helped me very much. Eventually they facilitated my final decision to be an artist. Because that had always been my problem up to then: I never knew what would become of me, because I always liked so many different things.

L. W.: Thus, photography rescued you from the dilemma of the multi-talented person?

K. M.: Yes, in a way. Because for a certain time I also studied in Hamburg. When I had finished school in Brazil, I went to Hamburg to prepare for one year for the German “abitur”, the school leaving examination qualifying for university entrance. After that I attended lectures on oceanography at the university. Because the ocean, the sea, has always fascinated me. In most

of my works the sea is always present. My hometown, Sao Paulo, is not directly situated by the sea, but not far from it. I always had a close relation to the sea; I love it and I try to keep near it. Five times I have already visited Hawaii; if you count all my stays I have spent there at least a whole year. Everywhere I was, be it Africa, Chile or Bali, there was always the sea. All these travels were almost automatically connected to photographing. The camera seems to be a part of me. And everything is interesting.

L. W.: But yet you want to change - or improve - the world by photographic means?

K. M.: I wouldn’t mind improving it, if it were possible. But what I really try to do is to show in the photographs my own way of seeing. Because I have a very personal way of representing things. And thus, it is unavoidable that I change them a bit because I want to represent them in such a way as my eyes would like to see them. This does not mean that I don’t like the world; I even find it very attractive. I am even fascinated by things that others don’t like. Often, I see very interesting details, little things, that others don’t notice. Before, in the first phase of my life as a photographer, I mainly documented things. That was in the initial four, five years. At that time, I took pictures of many things pertaining to nature and to human beings. I was looking for the aesthetical in them and thus formed my own language.

L. W.: How would you define this language?

K. M.: At the moment it consists of very graphic things. Certainly, that is due to the influence of my architectural studies, which helped me to find myself. The first certainty in my life was that I was very good at composing. In this way very graphic things came into existence. The compositions were very strong, with much color. And even in the black and white photos of this series color is still recognizable.

L. W.: How do you represent color in black and white?

K. M.: It is a kind of black and white which shows a certain contrast, an inexistent coloration, yet still in some way recognizable. I use different shades of grey, black and white. Especially in the works shown here there is a little bit of everything I have ever done.

The pictures of this series were created in the years 1990 and 1991. They were all taken in Brasil, in Sao Paulo. Not all at the same time, but in the course of these two years in five, six stages, in which I always looked for new interpretations. In this way a regular story emerged.

In 1989 I had published a book in Switzerland. It showed exactly what I had developed in the past ten years as my own style, very graphic, very colorful works. Up to then I had felt absolutely comfortable with this kind of photography, but after the book had been published and this work was finished in my life, I looked for new elements.

L. W.: So this series defines an intermediate phase?

K. W.: It is a phase of change. It lasted about from 1988 to 1992. During this time I tried out and looked for new things. With this work I discovered a new way. Thus, it became very rich and marked the beginning of a new development.

L. W.: Might it be called an experimental work?

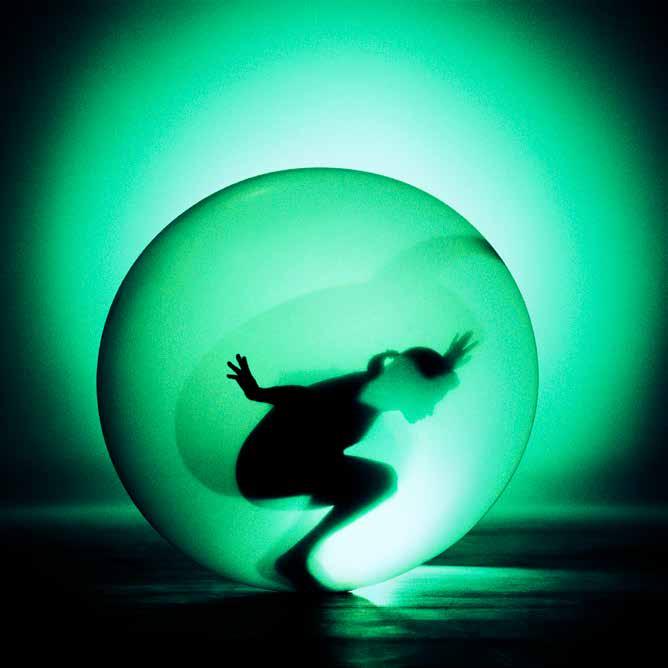

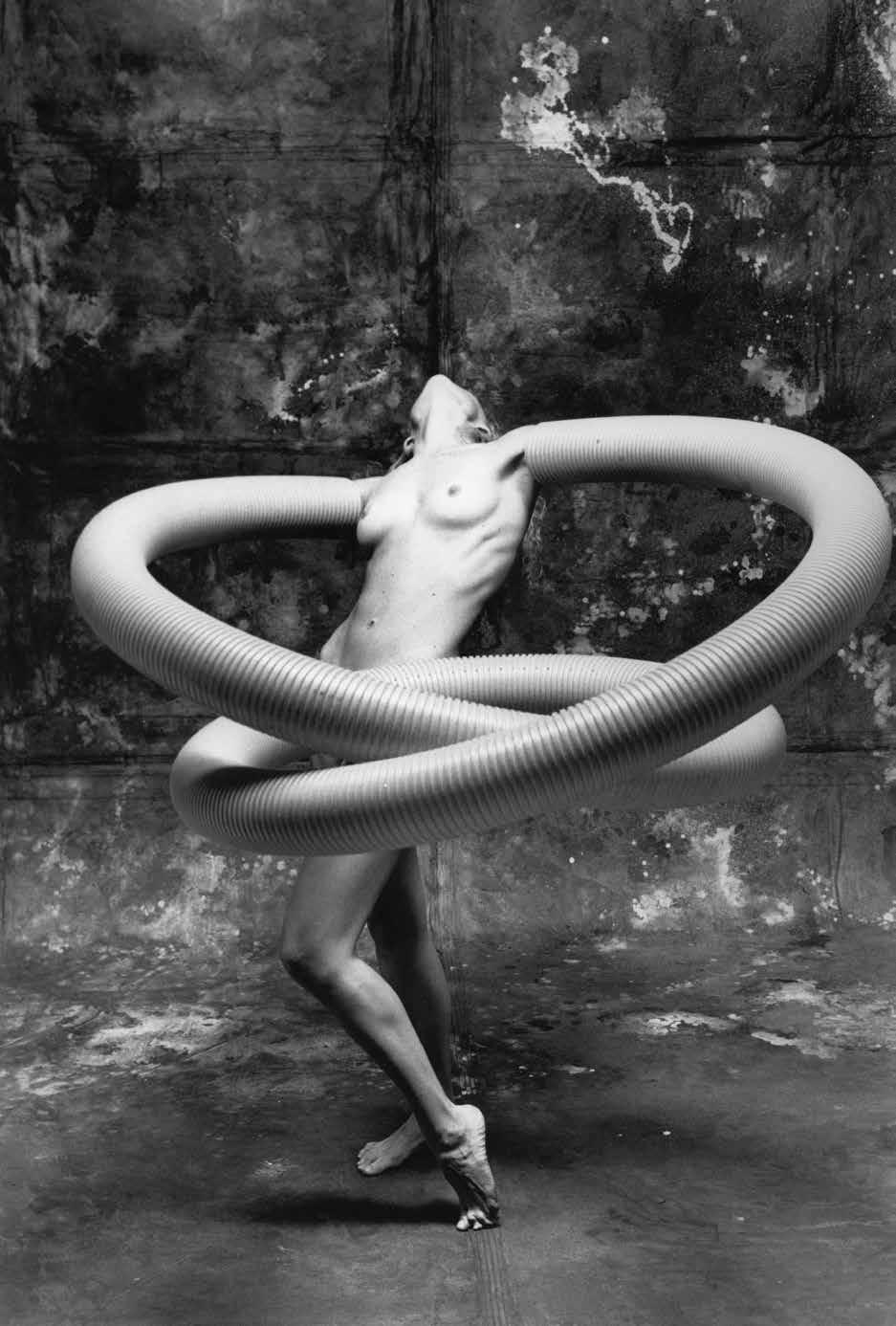

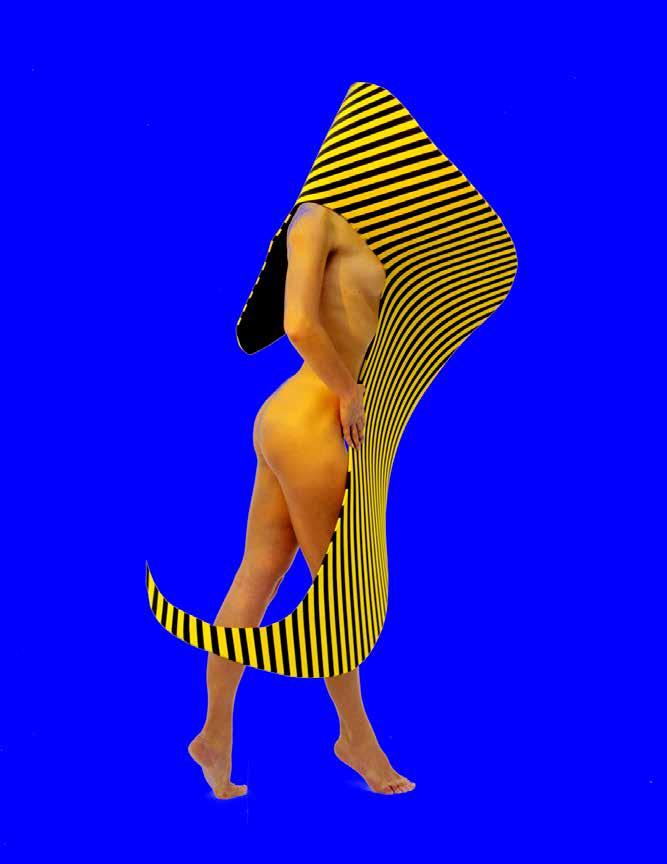

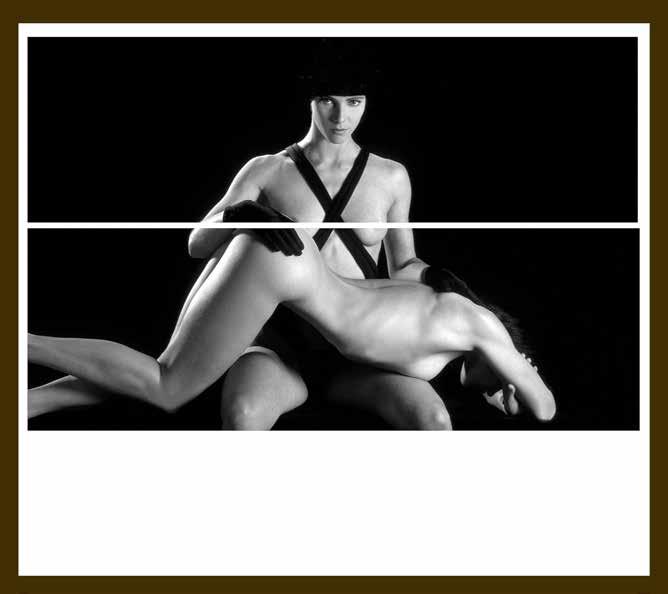

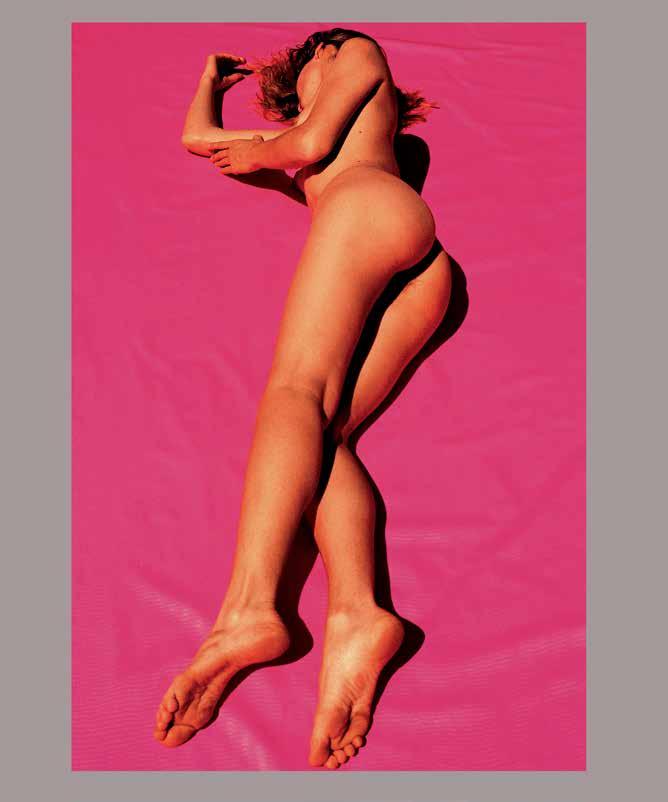

K. W.: Yes, I experimented a great deal with women, with elements. Women are always present in my work, as is the sea, or the water. There always has to be an additional element. I left statics, which I had preferred earlier, behind me. I abandoned strict composition and tried to incorporate motion into the pictures, and more expression. That was very important to me.

L. W.: Are these exclusively pictures of women? Are there no men among them?

K. M.: Since my early beginnings I never photographed men, always just women. Women are the beings I need to express myself. It is hard to say why this should be so; I don’t know it to this present day. But somehow they inspire me, and I

have a very good relationship with women. Therefore, it is easy for me to pass my thoughts on to them. They understand me, and they are able to interpret the things I want to show.

L. W.: Is it not a matter of something else as well?

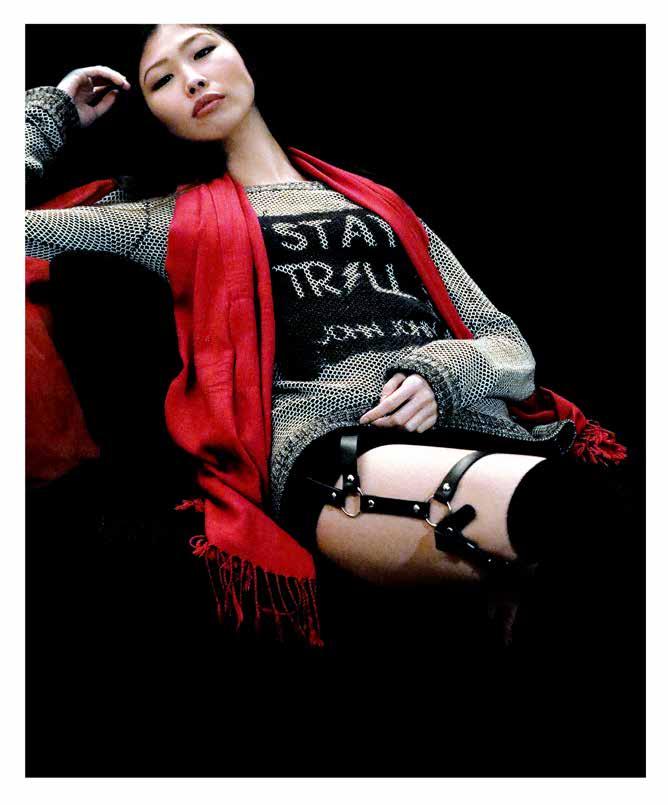

K. M.: It is a matter of sensuality. But certainly not of eroticism. Sometimes, especially here in Germany, people get me wrong on this point. I am not concerned with eroticism, but with something much more subtle. Most people might not even see it. Eroticism may show up - at first glance -, but behind it there is something quite different. An artist cannot easily express in words what he sees.

L. W.: Or else he would have become a poet or a writer...

K. M.: However, the medium of photography makes it very easy for me to express my feelings. This series contains in different forms many things that I experienced during the time of their coming into being. That extends from the aesthetical to the most subtle emotions. If you look at the pictures long enough, you will by and by discover things that are not so apparent. The pictures are less superficial than one might think.

L. W.: Is it not also very much a matter of who you take the picture of?

K. M.: Yes, certainly. Most of the persons shown here are women I know. One is a dancer, another one is an actress, and still another one might happen to be a model. Yet I am not looking for models, but for women that are in some way connected to the work I am just doing. They have to have a certain contact to it. And since here I am very much concerned about expression, about physical expression and about interpretation, I needed quite special persons who were suited to it. They were always the same three, four girls with whom I repeated during those two years the same things over and over again and added new ones.

L. W.: Was there something like a plan?

K. M.: This is no work to be done in one or two days. I had no strict layout in my head. In fact, I had nothing in particular

in my head, just every time new stories. I knew I wanted to interpret something with these shawls and these bodies. Then I experimented a lot, and I also let myself be inspired. For instance, by Rodin and Camille Claudel. These two kind of thrilled me at the time. Aesthetically, they were very much on my mind: I saw an exhibition and I read books about them. But though they inspired me, one should not draw parallels.

L. W.: Did you use the scarfs to emphasize the sculptural aspect?

K. M.: Exactly. Not only for emphasis, but also to create new forms and to narrate stories.

L. W.: Isn’t that a rather abstract approach?

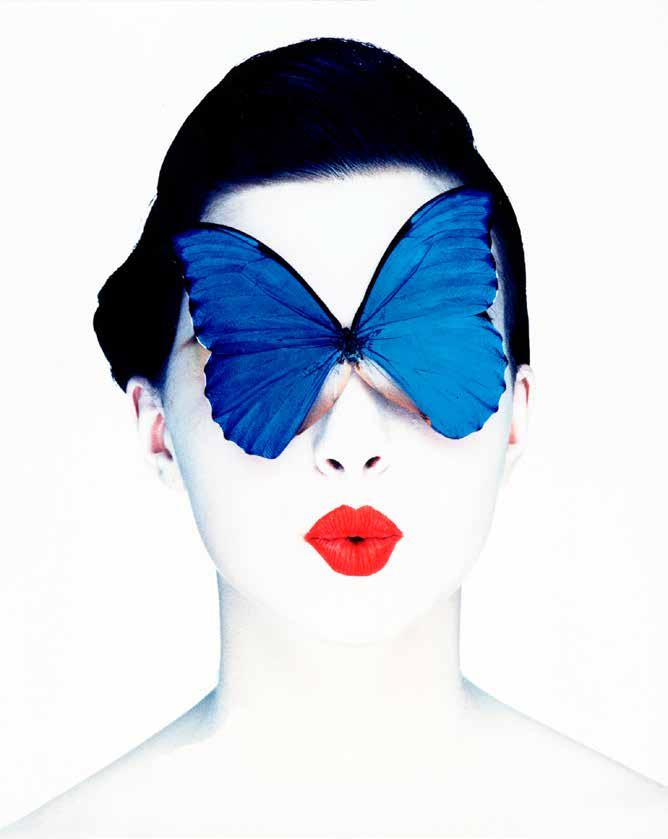

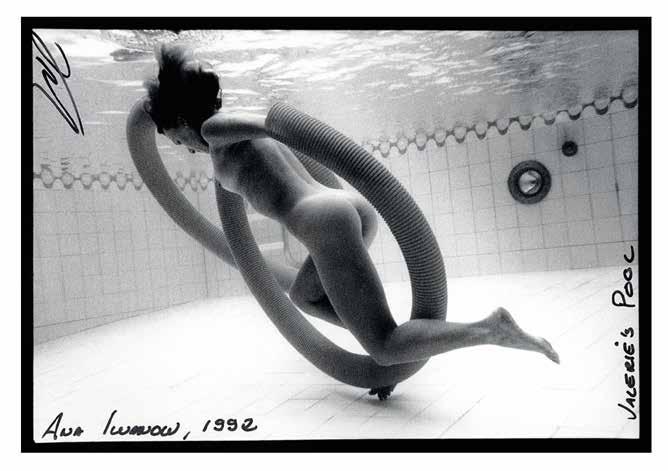

K. M.: Yes, indeed. But there are all kinds of different stories. There is, for instance, something medieval or something mythological. I explored various fields. Then there are these big tube-like elements, which I also use for interpretation. One picture, for instance, is called “Anna and the Serpent”, another one “Anna and the Butterfly”.

L. W.: I notice that you tend to transform women into animal creatures. What exactly does that mean?

K. W.: Personally, I have no idea. As I told you, I have no layout, no plan. I arrange a photo-session; there is everything I want, gathered in one place: the women, the landscape, the elements. And then I just let it flow, without giving it too much thought. It just wells out of me, as nature intends. How and why this happens I don’t know to this day. I haven’t yet found any explanation for it.

L. W.: Couldn’t it be the privilege of the photographer that he doesn’t have to explain? In contrast to those contemporary painters, sculptors and object artists who are completely detached from the object and thus have to rely on a theoretical framework. Maybe that is something one doesn’t need so much as a photographer?

K. M.: Yes; but in my case one still does. Because it is exactly the same: I have to combine these elements. I am

just reading a book by Wim Wenders about photography; its title is “Once”. There he writes about how photography really just happens once, at this one and very moment. Basically, he continues, there are two pictures: the one the photographer is taking and seeing at this very moment, but also the photograph as his self-portrait behind the camera. What he represents at this very moment when he presses the shutter release button.

Lilo Wirth

International Nude Photography Magazine

Divas (1991)

OPHELIA S DEATH

There are photographers who travel all over the world in search of their photos; others invest in expensive studios, and others chase celebrities, wealthy people, and beauties, hoping to catch them off guard... Klaus Mitteldorf, however, does not need much to establish his photographic universe: three models, a swimming pool, plastic flowers, and fabric backdrops are enough to transform his visions into images. For it is not reality, as it presents itself around him, that interests his photography, but rather that universe originating in his head, his fantasy, his dreams. In his most recent book, with the complicated title Zur Rechtfertigung der hypothetischen Natur der Kunst und der Nicht-Identität in der Objektwelt (For the Justification of the Hypothetical Nature of Art and the Non-Identity in the Objective World), Peter Weibel states: “It is art to demonstrate that the world is artificial”. We ask ourselves how to do it... The starting point would have to be a direct confrontation with the world in order to demonstrate its character, its artificiality. But the one who portrays the world as it presents itself runs the risk, in the end, of having in his hands an image that harmonizes so closely with reality, as we perceive it, that it ends up seeming extremely normal and ordinary to us, and thus the photographed reality no longer seems artificial, but rather exactly real. However, Peter Weibel also does not assume that it is enough to portray reality by means of other instruments in order to unmask it as artificial. The current and evident popularity of produced photography probably lies in the fact that it has recognized, within its own medium, its limits in analyzing reality, now seeking possibilities of preceding the analysis to the photography or, in other words, no longer analyzing by photographing, but photographing what has already been analyzed. This is a matter of central importance for Klaus Mitteldorf. In his conversation with artist Luiz Paulo Baravelli, it became evident that the

photographer finds themself in a process of detachment from professional photography, which, in his opinion, does not allow him to exercise introspection, egocentrism, and uncommitted fantasy. The interesting aspect of this process of change from advertising photographer to photographer-artist is the fact that it is not a transformation from documenter of reality to documenter of fictitious worlds, but rather a change of paradigms: from social fiction, from the virtual reality of advertising, to the subjective fiction of individual fantasy. That the change from advertising photography to the world of the visual arts is experienced primarily as an act of liberation undoubtedly aligns with this process. However, it is not merely a matter of choosing: photographer or artist, as Baravelli would have it. Confronted with the present reproductions of Klaus Mitteldorf, Baravelli noted that the photographer is condemned, always, to photograph something concrete, whereas the visual artist has at his disposal the imaginary and abstract world. Also his is the image of the photographer as a kind of hunter of a reality that is always already established and external to the work. In his opinion, photos produced like those of Klaus Mitteldorf, with complex and time-consuming assemblies, cannot be considered photography per se. Once someone decides to express themself through photos, he must always take into account that aesthetics and technique are intrinsically interconnected. There is not, Baravelli asserts, such a thing as abstract photography, in the sense that there is abstract painting. All these considerations must be mentioned, as they largely correspond to those of Klaus Mitteldorf, and because they illustrate, on the one hand, the circle of problems with which the photographer is confronted in his current work, and, on the other, his doubts regarding his definition as a photographer. As I have already stated, this is not a matter of choosing between photography or visual arts. The question is what the photographer does, what his interests and problems are, and how they manifest not only in each photo but in his

entire body of work. If it were true that the photographer is condemned to portray exclusively external reality, then only documentary photography, such as photojournalism, portraiture, architectural photography, or landscapes, could be called photography. The entire field of advertising and art photography, which moves in universes of fiction, would have to have another name. There is, without any doubt, such a thing as abstract photography. The 1950s also left their mark on photography. The 2 x 1 meter silver gelatin paintings of Chargesheimer, the “chimigrams” of Pierre Cordier, the abstractions of Fritz Pitz, Hans Martin Holzhäuser, or Gottfried Jäger, to mention a few, are well-known examples of this line in photography. Without any doubt, what Klaus Mitteldorf primarily grants to the visual arts also pertains to photographer, namely, that he may create his own aesthetics opposed to the prevailing common sense, if he wishes to prevent photographic aesthetics from being reduced to photographic technique itself. Those who do not make this break run the risk of subjugating their technical perfection and aesthetic notions to the rules of professional media photography. Klaus Mitteldorf is following this difficult path, seeking for his, so to speak, figurative language (which he masters so well) new contents, now defined by themself. The detachment from professional photography represents for Klaus Mitteldorf an act of liberation, an independence in defining the content of his photos. And this is exactly what he alludes to when, in conversation with Baravelli, he speaks of the contradiction between the work of the visual artist and that of the photographer. Klaus Mitteldorf does not so much oppose the aesthetics of advertising photography as its external definition. Just like Reinhardt Wolf before him, or today Peter H. Fürst, he strives to find his path, to dissolve the prevailing contradiction between the artist-photographer and the professional media photographer.

Klaus Mitteldorf sees no need whatsoever to deny

his technical skill and refinement, and thus produce low-tech photos, as do visual artists who work with photography. In this attitude, we must agree with him.

For if technology is not a criterion for the visual arts, it cannot be one for art photography either — that is, neither the perfect use of photographic technology nor the amateurish one can be criteria for evaluating a work of art. It was in his work in the media that Klaus Mitteldorf learned, exemplarily, to formulate fictions photographically, to make fantasy look like reality. Now, however, he no longer transports into photographs the ideas of advertising, but rather his own. And it is extremely important to him that they always seem like fictions, that their artificiality becomes evident, and that they can never, under any circumstances, be confused with reality.

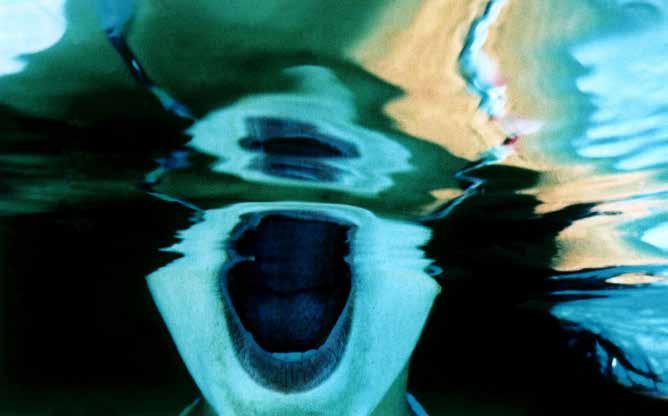

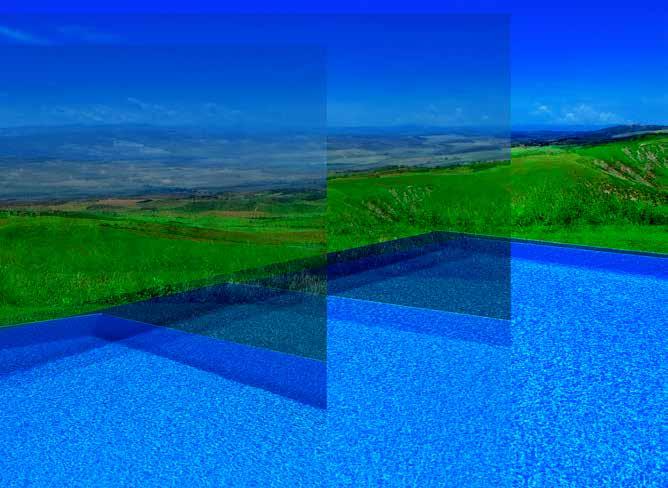

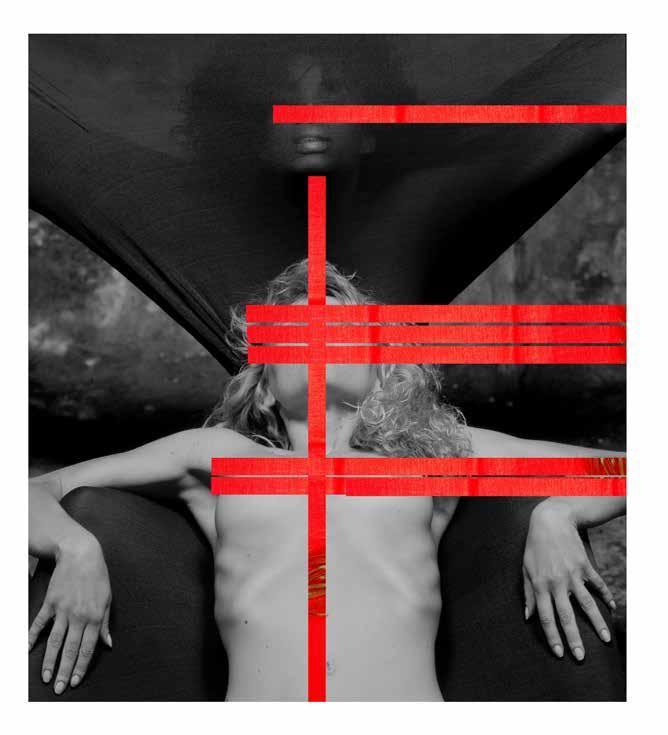

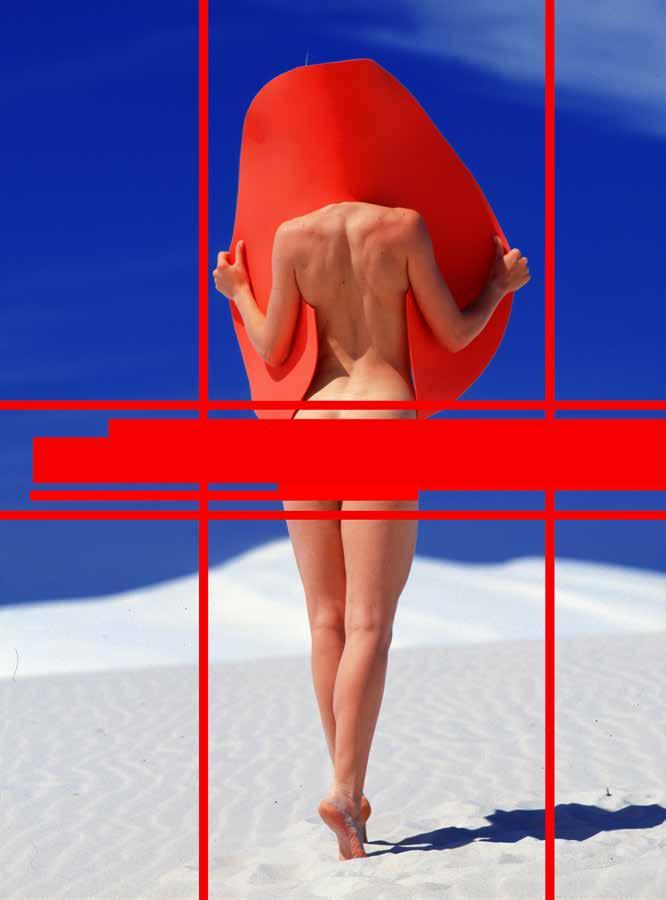

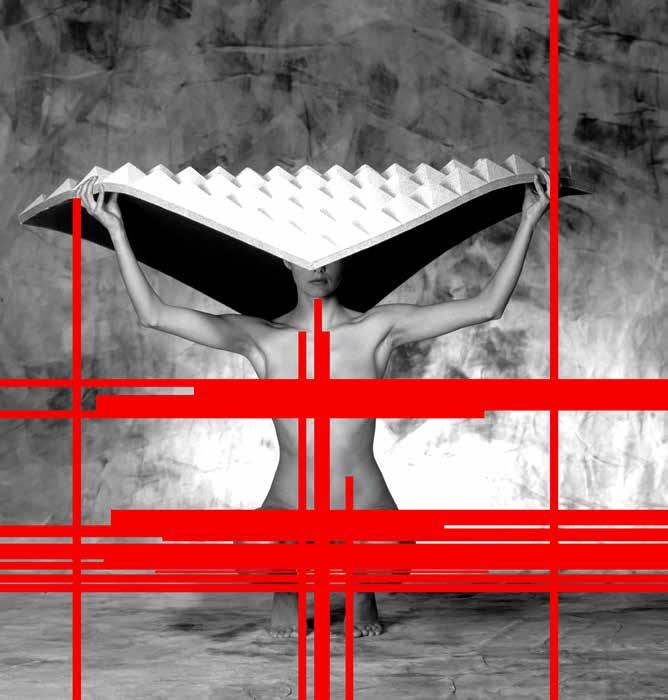

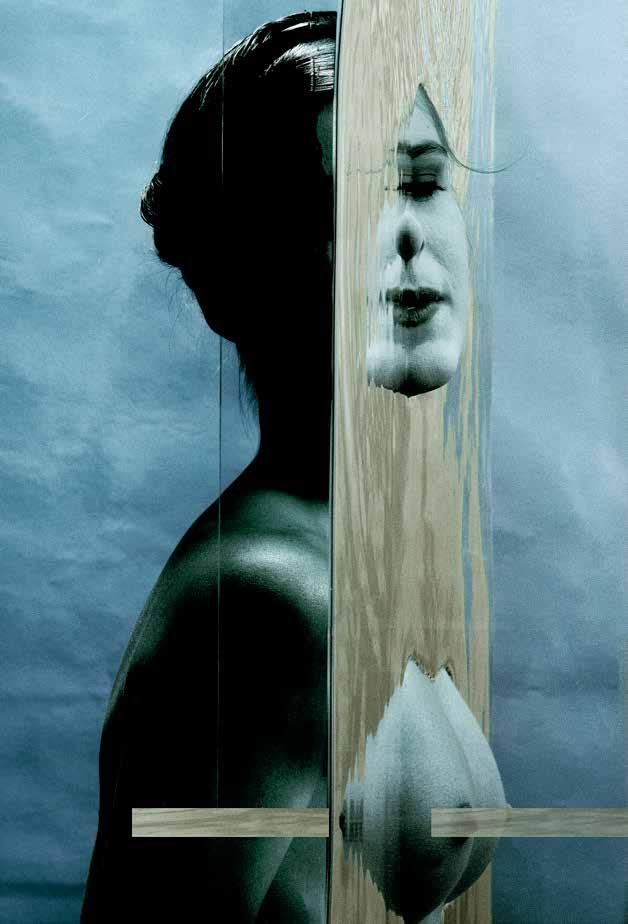

But since his fantasies, now made visible, are also part of reality, they are statements in relation to it. It does not interest Klaus Mitteldorf, however, to create mere critical oppositions to reality, but rather essays of a beautiful and idealized “counter-reality,” which can only be placed critically in relation to reality as long as it itself remains spotless. The reproductions presented here can be subdivided into three parts: the aquatic photos, the geometric ballets, and the amorphous play of forms. They all share in common a coloring that seems artificial to us. In the illuminated areas, the water is red, the bodies are greenish-yellow, the flowers blue and green. In the geometric ballets, the bodies are naturalistically plastic, but are confronted, complemented, or covered by plastic and glass elements, and with this, their corporeality is, on the one hand, underlined, and on the other, ends up seeming unreal. The most striking aquatic photos are those in which the water acts as a dividing line between two worlds, cutting the body in two. The greater its plasticity, the greater the difficulty in defining the space. In the black-and-white series with the dark fabric, new beings constantly appear — mosquitoes, resembling insects and spiders, in which body forms are

glimpsed, and which, nevertheless, show moving statues in the most diverse positions. Sculptures, elements such as water and wind, movement, ballet. These are the terms that come to mind when we observe the reproductions of Klaus Mitteldorf. It is no coincidence that some scenes recall Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, that the exasperated artificiality of some heads reminds one of Salvador Dalí’s sculptures or of Pop Art. But much of the effect of strangeness and novelty is motivated by a coloring that has its homeland in Brazil. A coloring to which we are not accustomed, and which we possibly know only from a few images of Carnival in Rio. This coloring is not merely multicolored. Taken in isolation, the colours could even be defined as muted and warm tones. The impression of colouring results, primarily, from a mixture of colours that does not respect our rules of chromatic combinations.

Above all, we find a series of non-complementary colour combinations that, on the contrary, are close to one another on the colour wheel, such as bluish-green, blue, violet, and purplish red. To European eyes, these combinations are disharmonious, or at least strange. For us, this colouring, in its entirety, can only underline the impression of artificiality, of fictitious worlds. But how could it be otherwise in a world in which the flowers are plastic, and yet this is not the reason they seem so artificial.

Dr. Reinhold Mißelbeck

Director of the Department of Photography and Video Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany

FLOWERS

Photography today is a highly technological product. It does not matter what is being seen through the camera. From the lens backward to the final print, the process carries the precision and technical mystery associated with advanced industry. It would be possible, marginally, for an artisanal photograph to still exist, in which the artist-photographer would fabricate the camera, the film, the chemistry, and the printing support – but that is absolutely not the case here.

Klaus Mitteldorf uses the best camera, the best film, the best light, and the best paper. The impression his work leaves is one of extreme technical refinement, of something at the very edge of what is possible with current photographic technology. If a photographer positions themself as an advertiser or media professional, such technically perfect photography would be in its natural habitat: the latest car model photographed by the latest camera model, laser photolithographed and printed in the magazine by the most modern rotary press. There is no discontinuity, and the reader receives a message that is not foreign to the medium that produced it. All would be well. Klaus could define himself as this type of professional and carry out this activity satisfactorily and without problems. But, for better or worse, he was bitten by the virus of art, and what could have been a profitable and glamorous profession became a straitjacket.

When a photographer redefines themselves as an artist, everything becomes much more complicated, especially with the evident association of photography with painting, understood here in the broad sense of producing fixed images. I list a few of the points where the two activities meet and conflict:

- The photographer, in a strict definition, is limited to creating a negative and copying it in a way that can be called definitive. The purist photographer does not crop his negative, does not

interfere with it after it is developed, and his “authorized” print must be able to be repeated identically.

- A visual artist is allowed an infinity of manual and industrial processes that are outside the standard procedure. He may incorporate low-tech or even zero-tech processes, harmoniously mixing the traditional with the ultramodern.

- The photographer is condemned to photograph something concrete, while the visual artist has easy access to the entire imaginary and abstract world.

- There is, now culturally, an impediment for the advertising or fashion photographer to transgress what is beautiful, clean, elegant. This is a central problem for Mitteldorf.

- A one-square-meter painting is a medium format within the reach of any painter, but a heroic size for a photographic print. A feeling of claustrophobia comes from photos that compress too much information into small formats. One must remember that, in a photo, space will be within the subject, whereas in a painting, space will be in the painted surface.

- The visual arts, and especially painting, have a very long history, something like forty thousand years. As photography is around 150 years old, moving from one field to another greatly expands the universe of references and comparisons. A simple thing in photography – a portrait, for instance – when considered within the larger scope of painting, must also deal with every other portrait ever made.

- The question of time and the “decisive moment.” Speaking of Cartier-Bresson, critic Dan Hofstadter says that every photograph is “an interception.” The simplest painting is a deliberate, successive construction, whereas the photographer is a kind of hunter of a reality already prepared and external to the work. Eventually, a posed photo, as happens here, may have a complex and lengthy staging, but the instant in which this scene becomes photography is not a construction, mainly because it is so brief, almost imperceptible. Photography, when treated as visual art, places production and recording in conflict.

In simple terms, much work is done when one photographs, but it is work that happens before and after the blind, decisive moment. When one paints, the situation is exactly symmetrical.

- Today, painters and photographers alike are in a subordinate position in relation to technology, but this is felt more acutely in the case of the photographer. If, for instance, in the eighteenth century no one knew more about paints than the artist-painter and no one knew more about metal casting than the master sculptor, today certainly Rolls-Royce knows more about painted surfaces than any artist, and NASA knows more about casting than the most informed sculptor. Even the most technically skilled photographer has only a schematic knowledge of how all his material works and, even if he stretches the limits, is forced to stay within what Hasselblad and Nikon provide. The painter at least has the possibility of making something dirty, wrong, and artisanal – and with that, exercising symbolic independence.

- It is normal, when photographing, to shoot five rolls of film in an hour. Then, among the 180 photos, one is chosen. The artist’s process is much more arduous – I am satisfied if I manage to produce a work every ten days, after ten hours a day in the studio. Good or bad, that work will embed all this conception. I do not deny the photographer’s effort, but it is a more diffuse, centrifugal effort, not centripetal like that of the painter. The hypothesis of pressing the shutter once every ten days should be considered by our photographer-turned-artist.

- In art, in painting in particular, half of the work is removing things after having placed them, reworking, correcting the course within the work. Perhaps this is technically possible in photography, but it goes against all its practice.

- One might argue that I am inventing this shift of Mitteldorf into the world of the visual arts, that he himself does not clearly position himself as such. I explain: modernism has placed us all in an ambiguous situation; what is called “visual arts” today covers an almost infinite range of manifestations and techniques. A visual artist is one who makes tiny figurative and

sentimental watercolours and one who projects laser beams onto the moon, who creates gigantic installations with railway scrap and who digs holes in the desert, the graffiti artist, the wild performance artist, and the conceptual artist who uses only typed texts. Some even take photographs. It has become difficult to establish a limit. After more than one hundred years of struggle to affirm the autonomy of the artist, modernism has triumphed, but that victory is in quotation marks. We can do whatever we like and call the result art – and this is a very simple, but very difficult situation. In truth, in all the examples of “visual artists” listed above, there is only a tenuous thread connecting them: an attitude of introspection, egocentrism, and uncommitted fantasy. This is the only thing that unites them, since materials, processes, and modes of production, dissemination, and funding vary at random. The impossibility of exercising introspection, egocentrism, and uncommitted fantasy is what makes professional photography the straitjacket against which Klaus is struggling. As he distances himself from advertising and illustrative work and disinterestedly records his personal fantasies, he becomes a visual artist and even a traditional visual artist (a “painter”), since his activity results in treated, fixed, and durable surfaces. In the classic phrase of Surrealism, it is not the glue that makes the collage, and surely today it is not the paint that makes the painting. It is a matter of attitude.

It seems that the somewhat dizzying hypothesis of becoming an artist tout court is still ripening for him. It is easy and not entirely fair to say that he still takes refuge in the technique he knows well. If, behind the camera, his certainty is indisputable, what that camera sees is a tangle of problems; the photographer knows exactly what he is doing, but the man gropes his way forward. I wrote elsewhere that, when starting a work, an illustrator knows everything, and an artist knows nothing. All his technical experience can do little to elucidate the specifically artistic problems, of the image itself. Despite

this “knowing nothing,” the trajectory of his work develops with clarity. From the first reproduced photos, from 1984 to 1990 (which I do not like), to the recent ones (which I like very much), the evolution is from exterior to interior, from stylization to delicacy, from effect to sensitivity. It is curious to see that the work evolves but becomes more tentative, groping for possibilities and risking entertaining simultaneous and conflicting visions. Within him, the photographer and the artist point toward opposite extremes of the artistic universe. This tension between poles impregnates Klaus Mitteldorf’s entire process with dualisms. Some of these dualisms are clear and acknowledged; others, we must discover. If I had to summarize in one sentence what is reproduced in this book, I would say that there is an aesthetics of desire and a desire for aesthetics struggling for the possession of his soul. We live in a world split by Judeo-Christian polarities: heaven and hell, body and soul, culture and nature, man and woman are clear extremes, but both aesthetics and desire are more diffuse, slippery terms. Choosing to express oneself through photography casts aesthetics toward the technique itself, with the sunlit clarity of the enamelled surface fighting with the darker world of desire to which the subject of the photos alludes. From the list of conditions enumerated earlier I wish to highlight one, simple: there is no such thing as abstract photography, in the sense that there is abstract painting. Not even Man Ray’s contact photograms escape this observation: every photo is a photo of something. This apparent limitation is used by Klaus as a fact in his favour: the photos are not beautiful images taken of just anything, like a still life, for example, nor are they accidental finds such as a beautiful light effect on a mountain cliff in which the photographer had no part. These are beautiful photos of beautiful (and metaphysical) situations created specifically to be photographed. It is inevitable for the viewer to imagine himself making these photos, under the sun or in the water, in the presence of these mythical faceless women. The existence

of a correlation between the mood of reality and the mood that its record produces is here a metaphor for this figurative commitment of the photo. It is an approximation, but we might think that aesthetics is an abstract notion, whereas desire depends on a being-there, of a reimagined reality. The figurative image describes the variety of the world and its infinite richness; it is an art of the surface of things. As Italo Calvino says: “It is only after knowing the surface of things that you can venture to discover what lies beneath. But the surface of things is inexhaustible.” Figurative art is horizontal, topographic, human, and compromising. The “looking beneath,” impossible according to Calvino, is an ascent or a digging, aiming at paradise if we choose one direction, or at hell if we choose the other. The horizontal search is aesthetic; the vertical is ethical. Matisse is horizontal, Mondrian is vertical, Andy Warhol is horizontal, Pollock is vertical, the Italian Renaissance is horizontal, Islamic art is vertical. The surface is always beautiful, and what we call drama could be described as the intertwined fate of the surfaces of the world; this intertwining presupposes some overlap, a hint of verticality. A surface is always the limit of a body, and the interior of beauty is a mystery. The passage from purely formal beauty to the recent allusions to the mysterious is also one of the polar migrations through which Mitteldorf’s work passes.

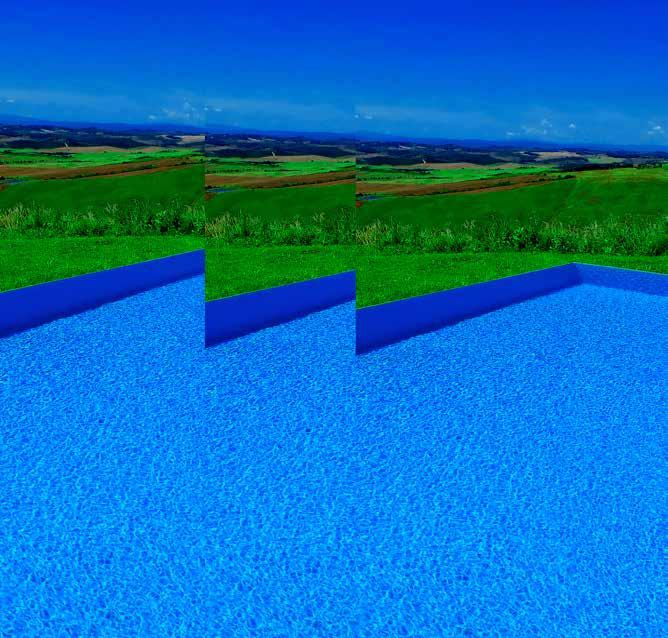

In these photos the sign that water represents is clear: an immensely mutable and sensual medium, but only possible for man in transitory situations. From the calm surface of a lake, one can just as easily see the stars reflected or sink into a hostile unknown. We might think here, without literal interpretations, of Jungian metaphors of the unconscious. The most recent series (of Ana in the swimming pool) is, without a doubt, the best art in this album, the photos that have the most to say to us, where the war and festival of the horizontal and the vertical, of surface and depth, are most clear. Flowers and women do not belong to the water and are there in

passing; what is being represented is an instant, and an instant of action for the woman, a human being. She needs to swim to stay near the surface, where is the air she will need in the next few seconds, but the flowers, stereotypical symbols of the beautiful, will surely sink, already cut and dead. Swimming can be an intense pleasure or a terrifying necessity; that these instants of life and death are also instants of desire and beauty is a synthetic yet poignant commentary on human existence. There are between-the-lines meanings. That the photos are taken in a swimming pool and not in a lake or the sea is an allusion to art and to the declaration of implicit artificiality. A swimming pool is a parallelepiped of water, and it is through the geometrization of nature that we distinguish ourselves from it. That the flowers are plastic is a subtle irony, because this is only perceived outside the photo, when one reads the titles, since the eye has seen and been moved by “nature.”

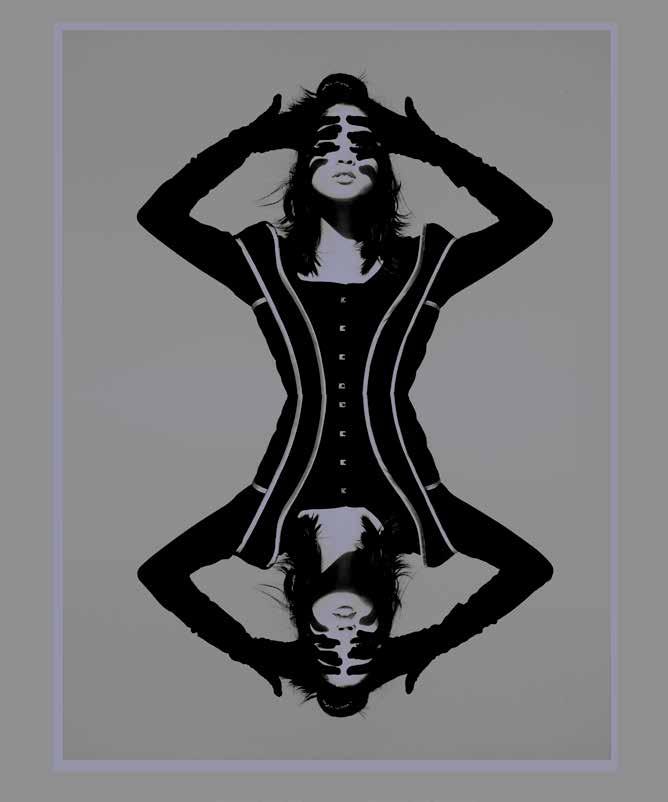

This awareness of polarities also clearly returns when we notice that there are several photos printed as negatives or, with a little less clarity, in the older works where the two models appear, the white and the black. In these photos, one must notice an air of violence, of gagging and immobilization, and this has an important echo. For many people, the threshold between eroticism and pornography is not very clear. As Mittendorf’s vision points in that direction, I allow myself to define: sex is action, and erotic sex is a harmonic action between two people; pornography, understood here as sexual violence, is any act of a sexual nature carried out against someone’s will, generally a woman, that is, an immobilization of her, physical or mental, while the man acts. As a painter, I often work with female models, and the very situation of remaining motionless while the artist acts have a parallel with pornography. In these photos of Ana and Zuleica, this is a disturbing fact; staging strange and forced poses, introducing geometric elements, and using harsh light are the possible actions of the photographer here, an action almost absent in the Ana in the pool series,

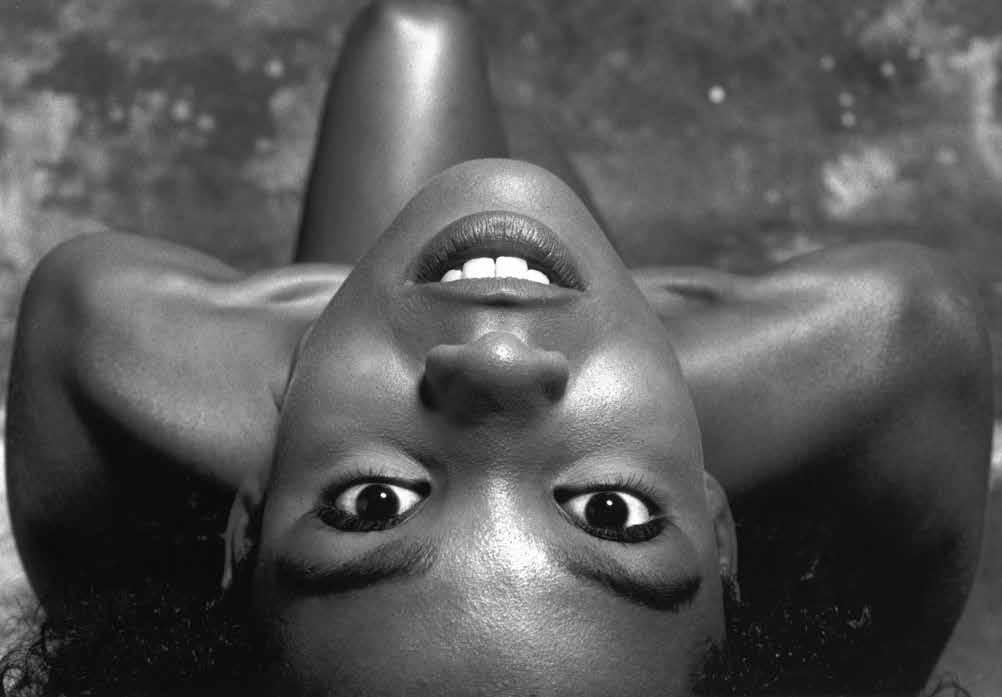

where the light stretches, the gestures are of pleasure, and she acts of her own accord, guiding the photographer’s action rather than being immobilized by him. The photos came close to being pornographic but became erotic.

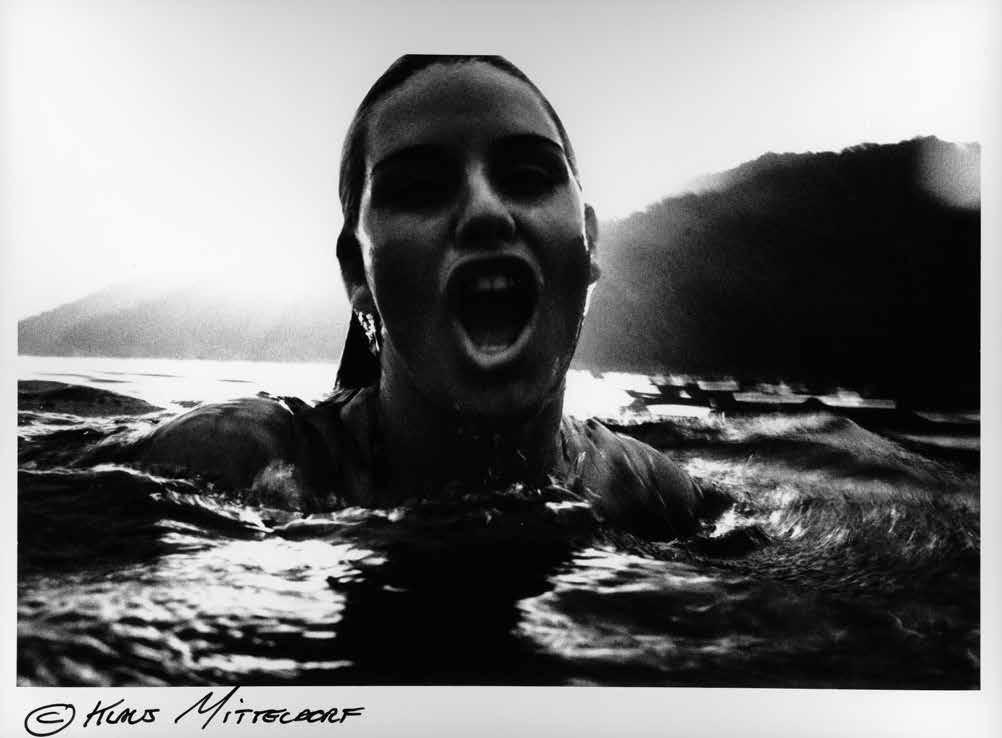

Placed wisely as a conclusion, the last and the antepenultimate photos, of Karina screaming, perhaps point to a direction for Mitteldorf’s future work. He finally comes close to that mysterious figure, who acts with passion, screaming –we do not know whether in calling or in despair – and makes an almost journalistic photo, in black and white and without formalism. It is the record of a woman’s action, not the pose of a model. Close-ups are very rare in his work, and here again appears a polar difference between these photos and a similar, older one (Papillon). The clock has made a full turn, but time continues – bon voyage, Klaus!

I would like to add another different thought that Klaus’s work evokes. It is, surprisingly, a political notion, in a body of work that seems to pass by this issue. He is a person of dual nationality; half Brazilian, half German, and one of the sources of his energy is the tension between these two very different ways of being. The rich, old, white, orderly country coexists within him with the poor, young, mixed, and unequal country. This polarity also implies symmetrical assumptions for the respective artists.

Put simply, the function of the artist is always to be on the opposite side of the common sense of the average person and to say all the time that the reverse of what is practiced might be interesting. Thus, it is characteristic how the most sensitive German artists generally make tense, dirty, embittered art, and how vital, clean, and positive is the art that, also generally, Brazilian artists make. Artists always do the opposite: given a row of arrogant, shiny limousines, one thinks of slashing tires and breaking windshields; given a pile of rusty wrecks, one thinks of patching them with wire so they last a bit longer. In his first works, Klaus is still harsh in this moralizing

choice: the photos impose geometry and cleanliness almost by force; even the “tropical” colour is harsh and schematic, the women’s sensuality prohibitive and dry. There are even frightening imaginations, like that of the photo on page 56. He gradually realized that this “German” order does not work here. It is necessary to find a Brazilian order, and one of the things I find most enchanting in the new works is when he glimpses it. An Israeli diplomat, visiting Brazil, found it impossible to have a pessimistic view of life in a place with so much water, and water serves Klaus to investigate the principles of this new Brazilian order: fluidity, lightness, iridescence, and a metaphysical eroticism that impregnates even plastic flowers. It is a political platform suited to the country we desire.

Luiz Paulo Baravelli

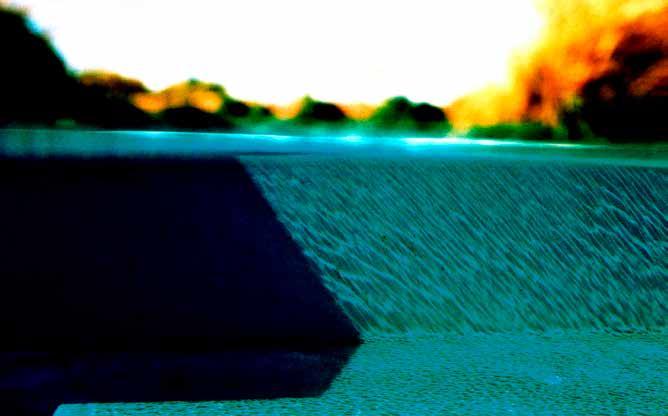

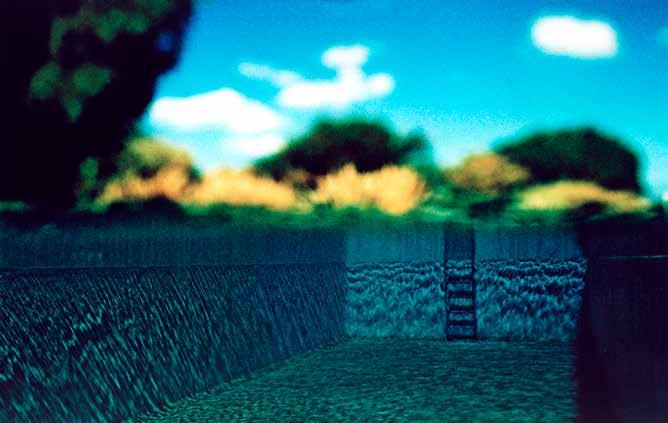

KLAUS MITTELDORF REGISTERS THE AGONY OF THE MODERN WORLD

In his most recent book, “The Last Cry”, he makes a flagrant portrayal of models as unprepared and aimless beings at the end of the millennium.

As a photographer, Cartier-Bresson embraced the surrealistic ethic, apart from his aesthetic which, in his own words, was nothing but the resolution of a literal joke. In other words, the French Cartier-Bresson never perceived the parody, but the (po)ethic of surrealism — the construction of a fantastical world appealing only to concrete elements — the same ethic perceived by the Brazilian photographer Klaus Mitteldorf. His third book, “The Last Cry”, to be released as part of the Pinacoteca no Parque project, is proof of this resistance to mere aesthetics and surrender to the ethics of surrealism. The book, which will cost R$ 35 during the event (and R$ 45 at bookstores), is a sophisticated project published by Terra Virgem. “The Last Cry” is 136 pages long and printed in seven colours by the highly regarded Italian publishing house Mondadori, with an initial edition of 3,500 copies. The publication is a graphic project by Sylvia Monteiro, with a preface by Professor Rubens Fernandes Júnior. It has nothing in common with the two previous books released by Mitteldorf: “Norami” (1989) and “Klaus Mitteldorf Photographs” (1992). This is an investigation of signs of a different nature.

While the first two worked as a showcase window of the impeccable technical work of a photojournalist trained in architecture and dedicated to fashion and advertising, “The Last Cry” is an essay about existential pain — more precisely, about the anguish of the end of the millennium, when the world seems to be populated by survivors of every kind (those with rare diseases, victims of nuclear disasters, the chronically depressed, etc.).

Water is the common denominator of all his 60

photographic works and installations (both colour and blackand-white) that will be shown in conjunction with the release of the book.

The “cry” can be either the primal relief cry of Munch, or like the one in the final part of T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” — a cry for help for all of humankind.

Beautiful top models, commonly seen on the covers of international magazines, emerge shouting from the waters of lagoons, beaches, and rivers, but their cries — paraphrasing Saint Matthew — are not heard in the squares. It is quiet, mute, inaudible. Therefore, a pure cry of desperation, echoing drowned bodies. The drowning, obviously, is a metaphor for the limits to which every human being is subjected. It can represent either death or rebirth. This subject is very familiar to the photographer, a well-experienced surfer who has saved at least three people from drowning.

The locations are diverse: from a lake in Bavaria to the Paraguaçu River, from the backlands of Bahia to pools and beaches.

The techniques are equally varied, from Polaroids to film and pre-press, including salted paper processes from the early 20th century.

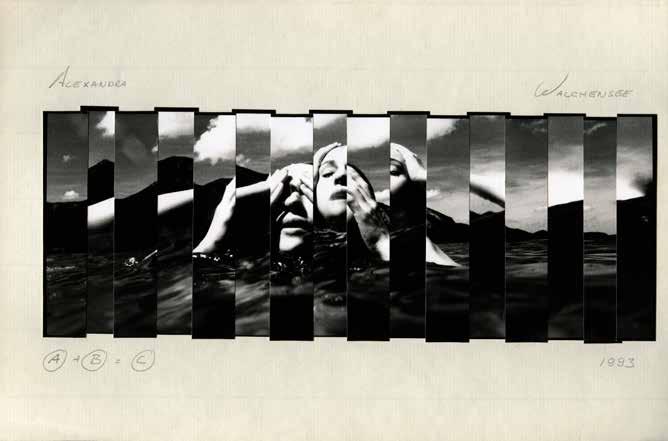

Among the 60 photos chosen by curator Rubens Fernandes, “Autobahn” (highway), a series of 22 photograms, draws attention for the dramatic tone of the model’s cry in this four-meter-long panel. This time, the medium is not water but earth. Made five years ago on the road connecting Munich to Salzburg, the essay shows the German model Alexandra (resembling Liv Ullmann at the end of Ingmar Bergman’s “Shame”): morally affected by civil wars and ashamed of being one of the Holocaust survivors.

“I am not a subtle photographer; I like strong colors and have always pursued a high level of technical excellence”, says Mitteldorf, the son of a chemical engineer who hoped his son would graduate in oceanography. Initially influenced

by the technique of Art Kane and the sensual surrealism of Sam Haskins, Mitteldorf was traumatized when he first began distorting bodies like Kertész. “I wanted to create a surrealistic scenario in a realistic setting until I discovered there was nothing better than adopting nature as a model.”

Another of Mitteldorf’s concerns: how to photograph the spirit — in other words, how to make visible what is invisible in people? If Klee could do it in his paintings, why couldn’t photographers?

Here lies the explanation for the concentrated focus on the models’ faces and the lack of focus on the scenery. These are photos taken in bad weather, under precarious lighting conditions, in order to heighten the expression of these agonizing cries. “There are also romantic references to Ophelia’s death, but I wouldn’t say this is a book of fine arts — it is one of analysis, of investigation into the philosophy of photography.”

By Antonio Gonçalvel Filho O Estado de São Paulo

The Last Cry (1998)

FROM THE NEGATIVE TO THE SYSTEM

The other’s Gaze emerges from beyond. It resembles nothing: only itself. A photographic portrait is a revealer of this frontier: It can go from nothing to the world beyond.

From the almost surrealist essays where characters emerged from the waters to meet other bays and cities , and later naked bodies, the image of the missing saint, a disguised self-portrait, and beyond, when all the movement of the visual muscle found another/same/even more abstract direction in superimposed figures and portraits with glasses and a brain also scattered through the streets . From then until now, a decade and a half has passed. Klaus Mitteldorf finally arrives at this time of today, agoraquando (now-when), fragmented, and delivers to São Paulo his “virtual and technological” system. The twin towers have fallen; war has become as popular a spectacle as soccer; advertising offers human feed to strengthen the health of your neighbor; and Brazil, in its popular ultimatum, has created a language with no plural, where its “new” children, always in ascending order, try to open the airplane window on their first honeymoon flight. Inside, we are emptier still. With all this daily celebration melting away seconds, photography has forever established itself as a language of speed, of flow, and of confrontation between what is appearance and what is memory. When? Now?

And so the photographer, using a cell phone and a lowdefinition camera, took to the streets to deal with what interested him in the city where he lives and observes. He started from his personal archive, where more than three decades of his history are preserved, to the day after. São Paulo Blues is about this experiment between what is perpetual, virtual, and technological. Between what is offering and what can be imaginary. Matter or meaning? Mitteldorf — with his interpretation plates that in some cases transform negatives into positives/originals inverted

to negative/positives revealed as negatives — moves forward in quick takes seen from inside buses, on rusted avenues, in scenes lived in Capão Redondo between music and raw, naked reality. In his wanderings through the city’s backstreets — those that many who live “on the other side” can hardly imagine truly exist — he witnessed the people of crack in their oldest haunts, where now there is only rubble. These are images of that public wound where each user fights for their rights: on a visit during a political campaign, when everything is promised, a certain senator walking through the city centre heard the plea of a passerby: “Your Excellency, we no longer have space on the street. Why don’t you get a building and just verticalize Cracolândia? Put us in there and let our collective suicide roll.” The spectre of that man is in the photograph.

In a game of doubles, and to launch “São Paulo Blues”, Mitteldorf took as inspiration the painting Lilith (1987) by the German artist Anselm Kiefer, also a sculptor who often uses photography as support for his work. It is a piece lit in tones between ochre and brown, where São Paulo is seen from above, sprawled with its muscular buildings and interlinked veins. Seeing them — the painting and the city — it becomes inevitable to dive into their depths. Mitteldorf made a similar image, lighting and setting aflame a panoramic view in the upper 30%. Dust, dirt, and disappearance between concrete and mountains. It is the penultimate image of this book. If in Kiefer everything is coded through what the artist seeks to represent the past, memory, and to face what lies ahead, Mitteldorf’s intention with his blues codes is to deal with this same decoding/representation in the city he inhabits, to go beyond the painting and the myth of the first woman, Lilith — created equal to the first man and expelled from Paradise for trying to claim that equality. One turmoil inside another. One city inside another.

It is this tangle of motives that opens “São Paulo Blues”. A view from the bottom up, the wires of Capão Redondo, a geometric construction in graphic despair, a kind of headphone through which the voice of reality screams, only to soon after

have the non-imaginary world meet the verticality of myths that become part of the earth: now the buildings appear as cutouts; now we are here walking over the old stream, the Anhangabaú Valley; now the satellite dish casts a rounded shadow and that barred window integrates into the blazing panorama as much as the sound of the headphone that vibrates outside because, behind the bars, under house arrest, we still need to breathe. It so happens that before today, someone passed by here and scrawled in German, on some remaining wall: bodenlos — without ground. Inside the city, without ground. “São Paulo Blues” goes beyond photography, in a chronicle that immediately poses a question: what does the artist intend to “see” from here on? Is this a photography book? No, a book. A book in search of calm? A book of despair? A book of reflections? A book of mirrors? Even being a worn-out word, a mirror will always be a mirror: “A woman without a mirror and a man without selfconfidence — how could they survive in this world?”

A sepia light bathes the seat of Mano Brown’s car, from Racionais MCs. In semi-gothic letters it reads: “Vida Loka” (crazy life) You can still see a small shadow of the rearview mirror with some beads (a kind of talisman) hanging. It is in that sliver of mirror that the singer looks at himself and glances back as he drives, seeing the city and its passersby go by the side of his life and the side of others’ lives. Neither the singer nor the city is absent. This is a detail photograph. A summary. It is not an image of appearance. We are talking about a record of memory and imagination. Photographs were made to be interpreted. “São Paulo Blues” is an essay to be interpreted. Nothing in it is easy. A few pages earlier, the same icon, another car (what do men really prefer: self-confidence or a convertible? These days you can finance the latter in up to 90 months), graffitied on the gate of a house displays a period model to proclaim: “Peace! For Those Who Deserve It!” Bang. Bang. Bang. .38 caliber or Taurus 380? No, the shots are inside us. Hollow. Reverberating into eternity. A simple photograph points to the future: “For Those Who Deserve It!” And once again, the page of the book opens: “I am not of

peace [...] Peace is for the rich [...] Don’t ask me to cry anymore. I’m dried up. Peace is a disgrace. Carrying that silly rose in my hand [...] I won’t put on that blank face. I won’t pray. I’m not the one who’s going to take the square. In that crowd. Peace solves nothing. Peace marches. Where does it march to? Peace looks beautiful on television. Did you see that actress? On the trio elétrico, that actor?”

“Peace for those who deserve it!” That’s it. Page by page the word changes constantly, just as the photographs of “São Paulo Blues” may change. But what is a photograph if we cannot see it? Nothing. No photograph is ever the same when we look at it twice. And what is a book if we do not open it? Jorge Luis Borges answers that it would be “just a cube of paper and leather, with pages. But if we read it something rare happens: it changes at every moment”. No photograph is ever the same when we look at it twice. A photograph is like an open book: it can change at every moment.

Diógenes Moura Writer and photo curator

ACQUA

If words help us define people and things and create concepts, it becomes very difficult when we try to find an adjective to define Klaus Mitteldorf.

Perhaps the one that comes closest to him is the word investigative — or better yet, curious. But words — as often happens — are not always enough to explain or to tell what we mean. Mitteldorf manages to gather a myriad of knowledge and transform it into information through the construction of images. It may sound obvious, but it is not when we speak of Klaus. He manages to surprise us at every moment. He always comes up with something new, which, like the alchemists, he transforms into a striking image.

To think of Klaus’s images only in terms of extreme sports is far too little, given the variety of work he proposes to us. Restlessness, perhaps, is another word that comes to mind when we think of Klaus. From an early age, he always wanted to experiment, discover, and go beyond the limits imposed by film leaflets or the dogmas of photography: “I am a contrarian. I have always liked to go against pre-determined formulas that try to tell us what to do and what is right. I have always loved to research, and it was this research that determined the character of my work”.

These characteristics turned into saturated, contrasting images — but not harsh ones. They are images full of sensuality, of fluidity: “an image without contrast is not one of my photos”. His beginning in photography, however, did not come through research or study. It happened almost by chance. Often, we have the impression that it is photography that chooses us, not the other way around. It imposes itself: “in photography I found the place where I could be rebellious — not in a bad sense, but in the sense of being able to go against the current”. In his family, there was no tradition in this area: “my father was a chemist, my mother a housewife, and my siblings are all

engineers or managers. My artistic culture came from the school I attended, which was a Waldorf school. A school that taught me to work with forms and materials: I learned woodworking, ceramics, I learned to work with fabrics”.

Unlike many photographers of his generation, his idols were not connected to either photography or cinema: “I always read a lot, but my books were more about history, including art history. Painting and sculpture influenced me much more than cinema or even photography itself”.

But at a certain point, photography entered his life — or crossed his gaze. And it was through photography that he learned to see, to feel, and to realize that it would be the most fitting medium for him to express himself. Photography, which since its beginning has always been generous — adapting well to all forms of knowledge, helping to turn the invisible into visible — also adapted well to Klaus Mitteldorf’s need to translate, in a synthetic yet mysterious and subtle way, what he felt — and still feels — in his soul.

At the age of 13, he received his first camera — a Yashica. It was with this camera that he discovered the fascination of the image. It began to accompany him everywhere he went: “I loved photographing my friends; I was already trying out some experiments, but of course, they were all very bad. But I loved photographing”. Perhaps they were unpretentious images, boyish, curious — but over time they became what the French theorist André Malraux (1901-1976) defined as an “imaginary museum,” that is, chosen and sculpted images that we keep in our minds and bring back to the surface to produce new ones. Not just any image. A critic of his own work, he was never satisfied with what he produced. It was the late 1960s: “I compared what I did with other photographs I saw and could not understand how photographers achieved certain results, and I thought everything I did was nonsense, meaningless.”

But that feeling, instead of discouraging or paralyzing him, gave him the drive to go further, to experiment again: “I

set up a lab in my bathroom and spent days developing and enlarging. And it was during that time I spent in the darkroom that I discovered a series of things that became important not only for my photographic work but also for my personal life”.

Photography became his notebook, almost an interpreter between him and other people. Shy at first glance, he transformed when he saw the world through the lens: “people understood me through my images and liked what I did. It was through the eyes of others that I learned to like what I was doing”.

This, of course, brought him greater self-confidence and the possibility of continuing this path that gave him pleasure, that brought him peace.

Like many photographers, Klaus Mitteldorf also comes from architecture school. He entered the Brás Cubas College in Mogi das Cruzes, São Paulo, in 1974, at the age of 21. College was very important to him: “I created a really cool circle of friends, with people with great minds. With them, I began to travel, go to the beach. I learned to surf. And it was in this coexistence that I realized that I liked to document this life I was living with them”. Water is a source of inspiration in his photography. Perhaps due to the familiarity he built over the years: “I have always been fascinated by water. I like to photograph the fluidity of water, wet bodies. My photography is very sentimental. I am a very intuitive person”.

It is true — but we must not forget that the same calm sea often transforms and overwhelms us. If it fascinates, it also frightens. And that was another challenge Klaus accepted. With his youth friends, he discovered surfing. And he learned to surf precisely because he saw the beauty of photos taken in the water. And it was exactly the beach and surfing that gave him the chance to become a professional in imagery: “I began working for a magazine from Rio, the first surf magazine in Brazil, called Brasil Surf”.

While surfing, he continued his studies at college. But perhaps instead of designing architectural projects, pencils and

drafting tables were tracing a new life project. When he finished college four years later, the profession of architect had already been archived. Klaus had already had his photographs published in several magazines: “I even worked with Bardi for Arte Vogue magazine, photographed for Pop magazine, covered surfing championships, etc. In fact, I started as a photojournalist, but then, to feel more independent, I decided to set up my own studio”.

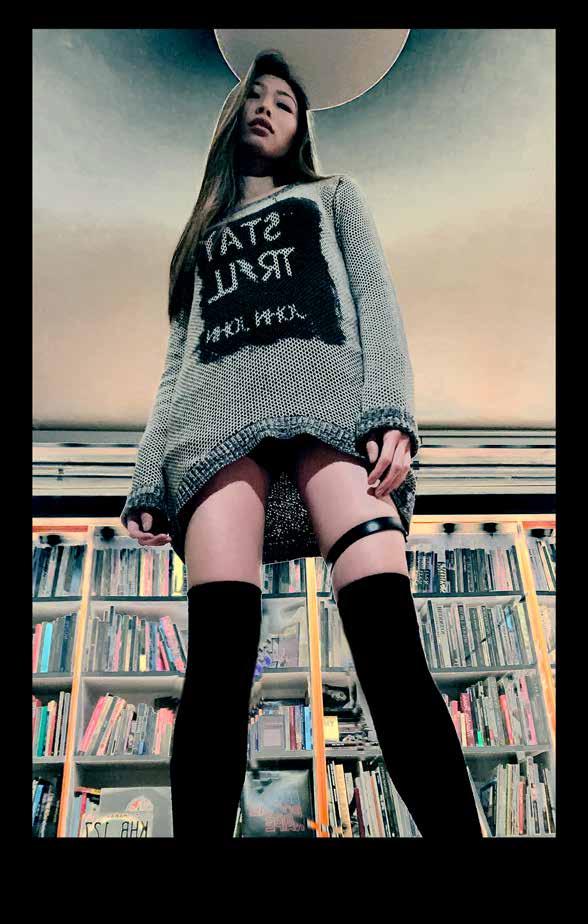

And it was in the studio that he allowed him to create his imaginary world, drawing from his image archive the scenarios he had been building for years. Closer to fashion than to advertising, it was in the studio — which he turned into a “creation lab” — that all the inventiveness he had stored could finally come to the surface: “Fashion taught me to photograph people, to direct. Besides that, it allows me to show creativity”.

And not only when conceiving the image. In his eagerness to create, Klaus even went as far as to “invent” clothes. He would draw, a stylist would turn his drawing into clothing, Klaus would hire a model and photograph not only the fashion setting but his own clothing: “only fashion photography allows this freedom. It is relatively free. You must reinterpret an existing element — the garment — but you can place people in many ways. Fashion photography is where I feel at home, where I can create in every sense.”

But it is not always like that. Often, depending on the client, fashion photography is so commissioned, so restricted, that it does not allow any great flight — but within what is possible, Klaus seeks that freedom.

That is why he has often attempted independent productions: “on vacations I always did shoots I wanted, also as experiments. I set up scenarios, called models, brought the clothes I had made, and...”

In these processes, beyond photography, came the discovery of another passion: cinema — directing people, creating stories through a sequence of images: “I take great pleasure in directing. Today I like making films. In fact, in the

1970s, when I started photographing professionally, I also made films. Very bad ones. I used a Super 8, and who taught me was Jean Manzon . I filmed and photographed. Over time, I ended up dedicating myself to photography, leaving cinema for later.”

Not much later, since he is making films now. This is yet another of Klaus’s abilities — not compartmentalizing life but knowing how to take advantage and bring together all the knowledge he has acquired over the years. Not an easy thing in our society, which demands that we constantly take sides in a manichean this-or-that way. But that does not work for Klaus.

While thousands of photographers or pseudo-image theorists complain about the incessant production or the banality of the image, he — with a gaze that still holds the daring of youth — takes this moment for yet another experiment. His most recent interest is directed at cell phones “that photograph”. Instead of complaining about the low quality of the images or using the phone just as a toy, he paid attention: “this texture, which some think is bad, I find very interesting. I cannot get this type of image with my equipment. And since I love working with textures, I discovered a new source. I am really enjoying this experience”. So much so that, despite some people turning up their noses, he will soon publish a book precisely with these images that many consider disposable and unworthy of being in a publication.

That is why we can say that photography has taken on a vital role in Klaus Mitteldorf’s life: “photography, above all, is very good therapy. Besides having fun with it, it is a source of selfknowledge, and that is why I love photographing both at work and on vacation. It has helped me communicate with the world”. But it is not just that. Photography helped Klaus change his way of seeing the world: “it helped me see — much more than I knew I could see. It broadens your horizons and helps you see what you didn’t believe you were capable of seeing. It makes you believe in what you are seeing. It is in photography that I take refuge whenever I have a doubt.”

Simonetta Persichetti

PHOTOGRAPHY AS WRAPPED WATER

If the images in “Introvisão” are liquid, and if, when confronting the other, we hold to the idea that photography will always be a self-portrait, what Klaus Mitteldorf signals in this series is a tactile provocation within a very fragile visual field (the gaze) and another way of thinking about how one sees — toward the other (before) and toward oneself. It is within this almost sculptural material — three-dimensional in its shadow-box contours — that the photographer throws himself into the abyss: seeing seen by the gaze. By delving into the senses that only vision transforms into life and death, “Introvisão” allows each image to free itself from itself: what is seen is not what is looked at. One sees what it contains, as in a game of beginnings, the reflection of that other, the one who is naked beyond the front, within oneself, he himself, the other.

Klaus Mitteldorf has always wielded his scalpel before the exuberance of colour. He is a photographer of layers. In earlier moments, he turned bodies and wet landscapes into abstraction, as a supplement for a psychology in which reality could confront itself with a make-believe construction. This is why he maintains a contextual relationship with painting, most precisely with a strong passage through a Matissean facture: light touches in a poetic explosion that redeem colour. There is a glancing perception in his images. By plunging beyond form, the photographer establishes a symbiosis, without allowing that possible play of synonyms to lead the revealed soul into the field of explicitness. This agreement is only possible over time. Mitteldorf probes his photography with images of a memory that, when meeting the possibilities of what now stands before his camera (the other tactile object), evokes literature as a “matter of emphasis”: without distortion, the gaze of reality elevates the temporality of the dream. This is the abyss between matter and distance.

In the moments when the photographer crosses the line of colour to reach black and white, and to see through the

eyes of others — himself — the instructions for use remake the transparencies. Cut like themes from cinema, here lies another question: photography almost as an installation within its present body (the next tactile object). Without wounds, “Introvisão” reaches the third eye to return to the initial theme: seen in transparency, the image turns toward itself and recognizes human existence as part of a corpus with no interrupted flow — sometimes paused, so that the gaze may return to the state from which it came; at other times announcing the fluidity of balance, so that the poetics of imagination may write its days; at other times still, immune to time, because there photography recognizes itself, to reflect the spirit of what others are — those, the ones here, ourselves. This is the abyss like wrapped water.

Diógenes Moura

Photography Curator

Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo

Introvision (2006)

NEXT: COMPLEX VISUALITIES

“The arts are not conceived as historically invariable actions of humankind, nor as an arsenal of ‘cultural goods’ that live in a timeless existence, but rather as a process that unceasingly advances, as a ‘work in progress’ in which every artwork participates.”

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

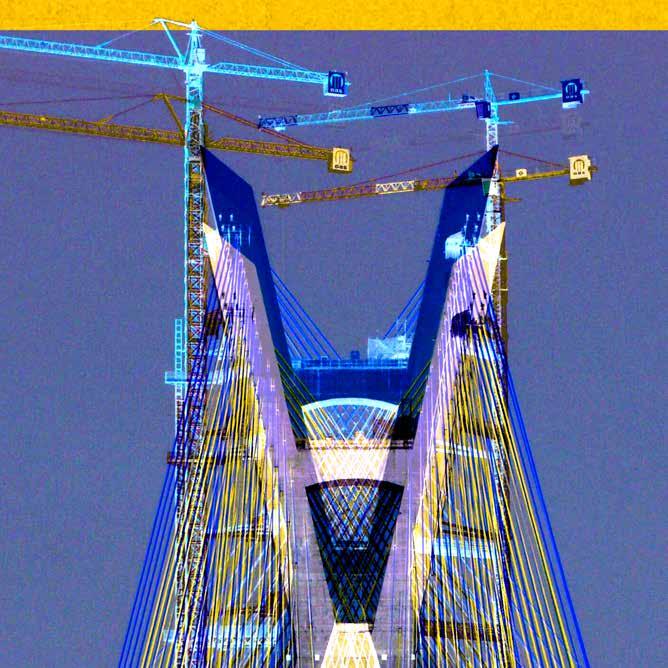

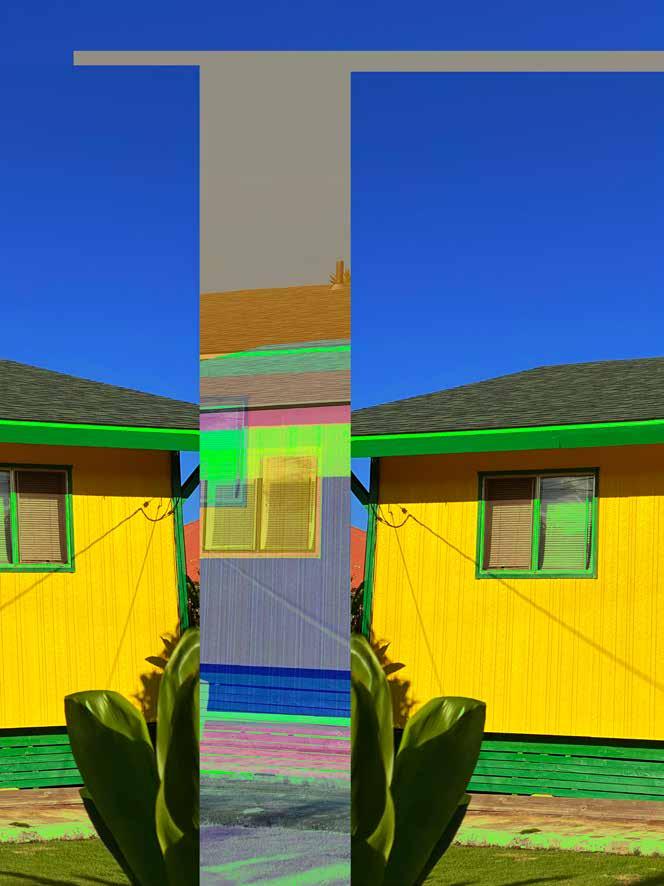

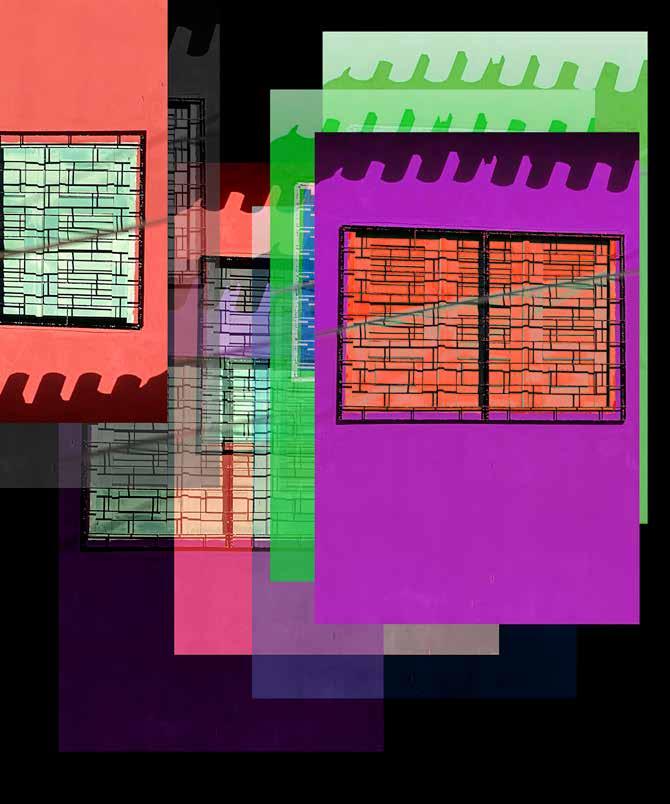

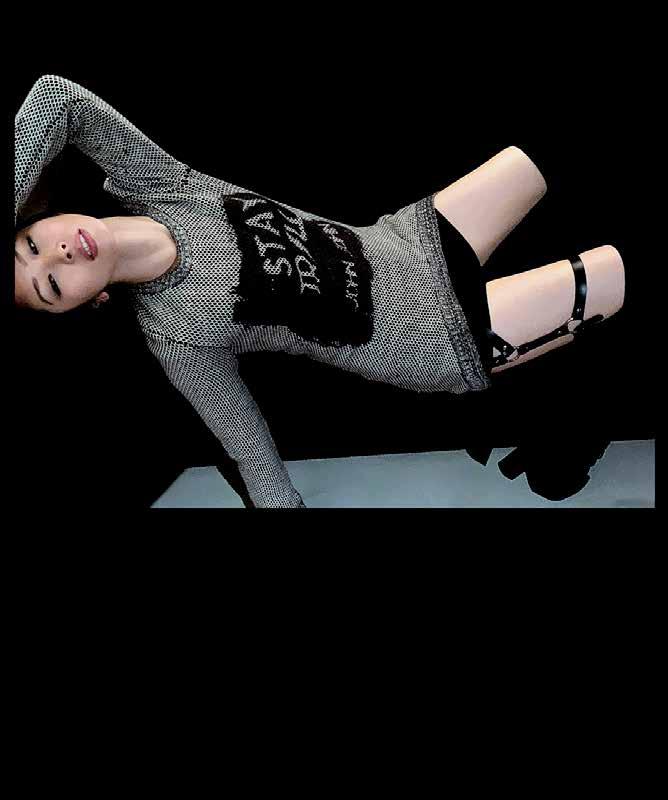

“Next” is a new series of images created by São Paulo artist Klaus Mitteldorf. It is unlike his first photo shoots, with their stunning syntheses of shapes wrought in an exuberance of striking colors, evincing a profound influence from his German origins on his visual production. They are also different from the pictures he made during his monochromatic forays, sometimes exploring the dramaticity of black and white, sometimes navigating through the blues. He studied architecture and was a surfer along São Paulo’s North Shore where he made incredible experiments as a pioneering surf documentarist using Super-8 cinema; he has lived in Germany, created photographs for important national and international advertising campaigns, and worked as a fashion photographer and movie director.

Throughout his wide-ranging, successful career, he has needed to master various optical codes and visual languages while transiting through a succession of mutually distinct phases, in ceaseless movement, plotting new courses for his nearly always explosive, uneasy photography. Currently unbound from commercial restraints, his production is now graphically and artistically bolder than ever. All of this has garnered his work an unquestionable position of importance within the context of Brazilian photography produced over the last decades.

Perhaps the artist’s most noteworthy characteristic is precisely the continuous flow of his production. In the series “Next”, the photographs – can we still call them photographs? –not only captivate our gaze but also throb on our retina, making our central nervous system shift into high gear to unravel the

visual puzzle it is faced with. I would say that it is nearly impossible to re-encounter the different times and places present in these pictures; when we can, it is through the help of clues provided by their titles. Not that this is important, but in the Western culture we are all immersed in, we are always seeking to discover the true meaning of what we see. It is hard to allow ourselves to be simply swept away by the beauty of the shapes or by the thrill of the signs that pulsate in each of these images.

When asked about their nature, Klaus Mitteldorf sidesteps: “I don’t know how to explain it, but the first thing I knew, I was taken over by the need to create these images”. Certainly, they do not fit into any category or trend of contemporary photography. They synthesize this globalized world, where millions of devices and applications are available to all who wish to visually document their everyday life. In Klaus’s visionary view, even though we see the images one by one, they actually “massage” our retina intermittently, as though they were superimposed on transparent, vibrating layers.

Canadian thinker Marshall McLuhan, the precursor of the concept of the global village, stated that “There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.” This is precisely what Klaus evidences in his images. In other words, in the not-so-distant future we will be seeing in a way predicted by the mechanic world, as though the mechanic visual possibilities anticipated what we would soon be seeing. McLuhan was also a pioneer in stating that each technological moment gives rise to a perceptually new man. It is enough to consider how sensorially different we are from our ancestors.

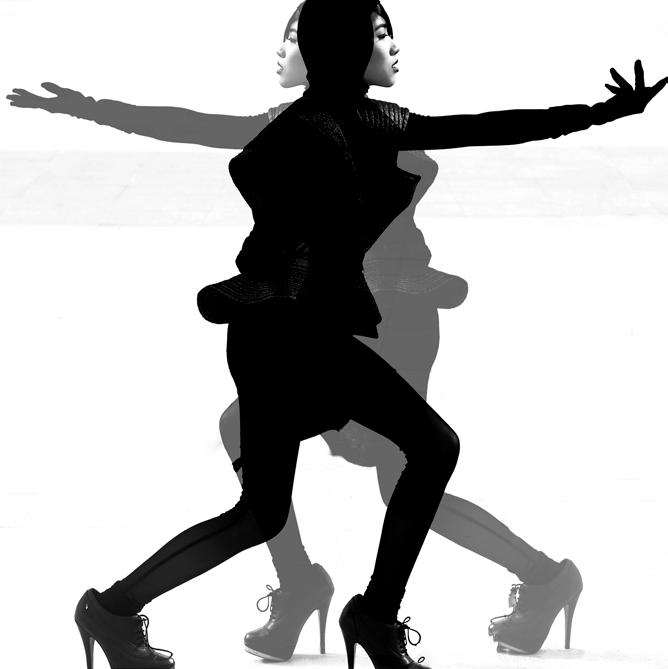

Certain historical shifts in visual language, of which we are already aware, can be associated with the images of the “Next” series. While the photo shoot foreshadows new perceptive possibilities, it also points to other moments of aesthetic rupture as a reference. The photo series “Next” inevitably brings to mind the experiments of Eadweard Muybridge, of Etienne-Jules Marey, of photodynamism (the Italian futurism of Giacomo Balla and

of the Bragaglia brothers) and even cubism. In light of this visual vocabulary of movement, Klaus Mitteldorf proposes new visual configurations arising from his own experience as an artist who explores and elaborates other perceptive possibilities. As we know, the progress of art requires courage, boldness, and rebellion in order to create unlikely tensions and to counteract environmentally imposed visual patterns.

In 1967, Marcel Duchamp, in an interview given to critic Pierre Cabanne, stated that his greatest influence in making Nu descendant un escalier, 1912, was not cinema, as many people had thought up to then. Actually, what had really touched the artist were Étienne-Jules Marey’s pioneering experiments with chronophotography. Marey set forth the idea that photography could be more interesting if it did not seek to capture “the before” or “the after” of a given instant, but rather “the during” of the time span of a given action. This is an astonishing thought for those who still see photography as a mere documental record of reality. Marey’s researches were so important and decisive for the photographic language that they later paved the way to Duchamp’s revolutionary ideas, which, for their part, constituted a new paradigm for the visual arts.

Establishing paradigms in contemporaneity, independently from the media used, is nearly impossible. But artists unceasingly seek visual possibilities that record our own time or point to future paths. A photo series developed in recent years by Klaus Mitteldorf, “Next” is an imagistic proposal that requires a perceptually differentiated spectator. It uses the same bidimensional surface which has supported photography for more than 170 years, including the experiments of Marey, of photodynamism, and of cubism, which sought to revoke the perspectivist illusion and to instate new modes of sensing and assimilating other sensations made possible by the machinic world.

Klaus Mitteldorf has unveiled the essence of the contemporary mechanic world, centered on digital technology, and knew how to create based on software. The images acquired

a pop aspect that recalls some of Rauschenberg’s collages from the 1960s. But of course, beyond these possible references it is necessary to know about the artist, including his background and the procedures he uses. With know-how and perspicacity, Mitteldorf aims to question the photographic image, which for him was never the simple representation of reality.

His response is a radical one: he takes some of the machinic effects and articulates them with the visual universe he has idealized in his creative paths. Mitteldorf proposes an interplay of images where blending, superposition, transparence, displacements and other artifices trigger distinct sensations that intensify and prolong a supposed continuity of the photographic shot’s frozen moment of time. He gives rise to a different sensation of rhythm that stems from the dynamic of the movements; he is concerned with the intermovement of a gesture; he explores the perception of the gaps between the movements. “Next” furthermore involves a performative character that is likewise present in other photo shoots the artist has produced, for example, “O Último Grito” [The Last Cry], where a performance facet is discernible in the actions of the photographic subjects.

Now his photographs have taken on other visualities, even while maintaining some of the unmistakable features of the aesthetics of his previous works, including color and movement, which accentuate their pop character. Klaus Mitteldorf has always been impulsive in the construction of his images, whose complexity and provocative tone are enough to make the viewer question their veracity. But this is entirely consistent with the artist’s opposition to creating works with an unchangeable reality. “Next” unleashes a frenzied visual possibility without breaking away from a certain tradition, without aiming to be a disconcerting discovery; its original, authentic images come like a condemnation of the rampant imagistic banality of everyday life.

In his manifesto “Futurist Photodynamism” of 1911, Anton Giulio Bragaglia emphasizes that “we are certainly not concerned with the aims and characteristics of cinematography

and chronophotography. We are not interested in the precise reconstruction of movement, which has already been broken up and analysed. We are involved only in the area of movement which produces sensation, the memory of which still palpitates in our awareness.” More than 100 years later we come upon “Next”, the outcome of a free outlook that perceives the symbolic power of the layers that kindle the multiple sensations that pervade our gaze with transparencies and radiant visions of light. The interpenetrations and superpositions of the images evidence distinct times which nevertheless coexist in the elaborate ethereal space created by Mitteldorf.