ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the NHS Trusts that participated in the LIFE BEYOND THE CUBICLE Second Pilot.

NHS Trusts

• Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health NHS Partnership Trust

• Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

• Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

• East London NHS Foundation Trust

• Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust

• North London Mental Health NHS Partnership Trust

• Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust

• Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust

• Royal Sussex County Hospital

• South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust

• University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust

Life Beyond the Cubicle Steering Group

• Dr Karen Lascelles

• Dr Dorit Braun

• Margaret Rioga

• Dr Nicola Shephard

Funding

This research study was commissioned by Making Families Count (MFC) to evaluate the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources. MFC was awarded project funding to develop these resources by NHSE South-East Region (with HEE legacy funds).

Glossary of Terms

LBC - Life Beyond the Cubicle

Family carers - The term family carers refers to individuals such as family members, partners, or friends who provide informal, unpaid care and support to someone with physical, mental, or emotional needs. These individuals may not always identify themselves as carers, but their contribution should be recognised and valued.

MFC - Making Families Count

Mental Health Crisis - A mental health crisis refers to a situation in which an individual experiences a sudden and severe deterioration in their mental health, requiring an urgent response from mental health services. This may include acute distress, suicidal ideation, self-harm, psychosis, or behaviours that pose a risk to the individual or others. A crisis is often self-defined by the person experiencing it and may require immediate clinical assessment, intervention, and support from crisis resolution or home treatment teams.

Service User - A service user is an individual who accesses, uses, or is eligible to use health or social care services. In the context of NHS England, this term encompasses patients, clients, and individuals receiving care, support, or treatment. It reflects a person-centred approach, recognising the individual’s role in shaping their care experience and outcomes.

Patient - A patient is an individual who is receiving or registered to receive care, treatment, or support from NHS services. This includes individuals accessing primary, secondary, community, or specialist care. The term reflects a person-centred approach and encompasses both physical and mental health services, recognising the rights, needs, and preferences of the individual in all aspects of their care.

Executive Summary

This evaluation report assesses the acceptability and value of the Life Beyond the Cubicle e-learning modules on healthcare professionals working in both community and in-patient settings. Designed to enhance understanding and engagement with family carers, the modules were widely adopted during the pilot phase as part of continuous professional development and were praised for their clinical relevance, emotional depth, and practical application.

A key strength of the modules was their ability to foster reflective practice. Through a structured format and the integration of lived experiences, the modules encouraged healthcare staff to critically examine their assumptions, values, and approaches to involving family carers. Participants reported that the content prompted meaningful self-reflection, particularly around complex issues, such as confidentiality, consent, and risk management. Peer discussions further enriched this process, allowing staff to share experiences and collaboratively explore ethical dilemmas.

The evaluation revealed measurable improvements in staff confidence and practice. Notably, there was a 14% increase in participants who strongly agreed they felt confident involving family carers in risk and safety planning. The training also led to a more nuanced understanding of confidentiality, with participants developing strategies to balance ethical and legal responsibilities in complex family dynamics.

Beyond knowledge acquisition, the modules inspired behavioural change. Seventy-seven percent of participants indicated they intended to modify their practice to better involve family carers, and 99% found the content relevant to their current or future roles. The training also enhanced emotional awareness, helping staff become more attuned to the experiences of families and promoting a more compassionate and inclusive approach to care.

In conclusion, the Life Beyond the Cubicle has proven to be a valuable and impactful resource in advancing reflective practice and strengthening motivation for effective family carer involvement in healthcare. To sustain these positive outcomes, it is recommended that healthcare organisations continue to embed these principles into routine clinical practice through ongoing training, reflective supervision, and organisational support.

1. Introduction

Making Families Count (MFC) in partnership with Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust developed the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources. The aim of the resources was to enhance healthcare professionals knowledge and skills in order to work collaboratively with carers ensuring that, where possible, they were involved in the care of their family member during mental health crisis. There is literature that underpins the involvement of carers within the care of their family member particularly at times of mental health crisis (Bradley & Green, 2018; Murphy et al., 2015; Warrender et al., 2021), however there is no consensus on effectiveness of the different interventions to educate and empower healthcare professionals in developing authentic collaboration with carers/families. The Life Beyond The Cubicle resources were co-produced by clinicians, people with lived experience of mental health crisis and carers, supported by an Advisory Group. The co-creation of the resources was essential for ensuring that the materials reflected the experiences and aspirations of those with lived experiences as well as the learning needs of clinicians which is what makes these resources innovative and engaging for healthcare professionals.

Family carers are often the first to identify symptoms of relapse or changes in mood and behaviour, making them valuable allies for healthcare professionals (Yesufu-Udechuku et al., 2015). The Triangle of Care framework (Carer’s Trust, 2010) emphasises the importance of including carers as key partners in mental health care, promoting better communication and collaboration among carers, service users, and health professionals. It is essential for patient safety that, wherever possible and appropriate, healthcare providers recognise and involve family carers as key partners in the assessment, treatment, and evaluation of care for patients with mental health problems. The LBC resources were designed to address these challenges by providing healthcare professionals with the understanding, tools, and knowledge to collaborate more effectively with family carers. This evaluation report assesses the effectiveness of the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources (Appendix 1) in enhancing the skills and knowledge of mental health professionals to recognise and involve family carers.

2. Evaluation of the Life Beyond the Cubicle

Modules

Aim

This project aimed to evaluate how healthcare staff utilise the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources and assess their acceptability for clinical practice.

Evaluation Questions

1. How do healthcare staff use the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources?.

2. What learning, if any, did participating healthcare staff gain from the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources?

3. How do healthcare staff engage with the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources and how acceptable are these for integration into clinical practice?

2.1 Sample

The sample comprised of clinical staff from eleven NHS organisations who completed the Life Beyond the Cubicle resources. The staff held various roles within the NHS Trusts (nurses, occupational therapists, consultants, psychologist, healthcare support workers). The staff worked across different community and inpatient services. From this sample, four individuals were recruited for more in-depth interviews.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1 Questionnaires

Pre and post-questionnaires were designed to assess the participants perspectives on working with family carers during times of mental health crisis, both before and after engaging with the LBC modules. The questionnaires were embedded in each module. The pre-questionnaire provided baseline data for the evaluation. The post-questionnaire assessed the participants experience of completing the modules, any lessons learnt and any subsequent influence on clinical practice.

The questionnaires primarily gathered quantitative data, but some of the questions included qualitative data, and where this data exists, it is used to provide some context to the quantitative data.

2.2.2 Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with healthcare staff that had completed the e-learning modules to gather an in-depth understanding of their experience. This involved using a predefined set of open-ended questions, allowing the interviewer to explore specific topics while also providing the flexibility to probe deeper based on participants’ responses (Appendix 2).

2.3 Data analysis

Quantitative data were statistically analysed using IBM® SPSS® statistics software. The questionnaire consisted of a mixture of closed and open-ended questions to facilitate detailed, narrative responses allowing participants to express and describe their experiences. The qualitative data from the interviews was analysed using thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, 2017). This method of analysing data highlighted the patterns and themes in the data.

Sample Size

Questionnaires

Pre-Questionnaire - 161 responses

Post-Questionnaire - 184 responses

Interviews - 4 x individual interviews

Findings

In this section, the evaluation report will outline the quantitative data from the pre and post-questionnaires. We include quotes from the free text in the pre and post-questionnaires, to provide context to the quantitative data.

3.1 Quantitative Findings

The Pre and Post-questionnaire Findings for Questions on Experience of Working with Family and Friends Carers

The pre and post-questionnaire analysis is based on nine questions designed to assess participants experience of working with families of patients who had experienced mental health crises. All modules had a pre and post questionnaire and the responses have been compared for this evaluation report. Participants completed the modules in their preferred order, and the questionnaires were not mandatory, resulting in different totals for the pre- and post-questionnaires. Specifically, 161 participants completed the pre-questionnaire, while 184 participants completed the post-questionnaire. The preand post-questionnaire responses could not be matched, as participants had the option to complete the questionnaires anonymously. The participants were required to respond on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. The data is presented below under each question, as a table showing the pre and post results, this is then followed by a brief overview of the main findings. In the post questionnaire 8 out of 15 questions allowed participants to offer additional comments. Section 3.3 provides a thematic analysis of these comments.

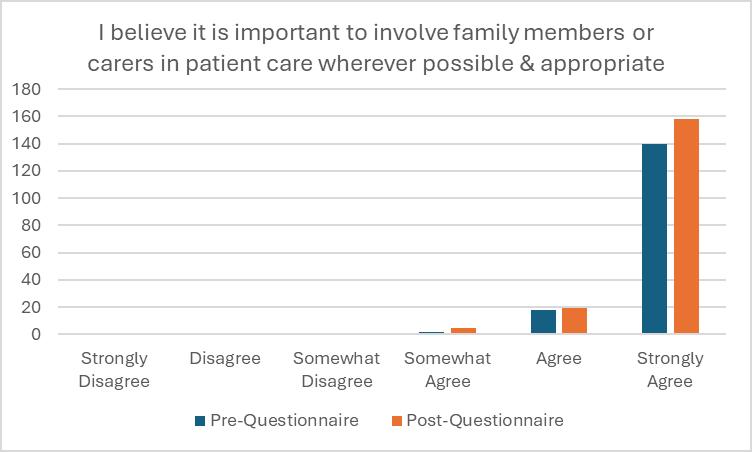

Data from Question 1

‘I believe it is important to involve family members or carers in patient care wherever possible and appropriate.’

Pre-questionnaire revealed that the vast majority of participants (99.5%) were in agreement that it was important to involve family members or carers in patient care wherever possible and appropriate; 87% of participants strongly agreed with this statement. Post-questionnaire showed consistent findings with 99.5% of participants agreeing with the above statement; 86% of participants strongly agreed with this statement.

Findings from both the pre- and post-questionnaires indicate a strong consensus among participants on the importance of family and friends in supporting individuals with mental health needs. This perspective likely reflects the influence of participants’ professional codes of conduct and organisational values, which emphasise the involvement of patients and carers in the delivery of care.

Data from Question 2

‘I am confident in involving family and carers in patient care.’

Pre-questionnaire findings indicated that 99% of participants were in agreement that they were confident in involving family and carers in patient care; 45% were in strong agreement. Post-questionnaire analysis revealed similar findings; 99% of participants were in agreement that they felt confident in involving family and carers in patient care. However, the percentage of participants who now strongly agreed with this statement had increased to 59%.

Data from Question 3

‘I am confident in involving family and carers in risk assessment and safety planning.’

Pre-questionnaire findings showed that the ‘agree’ options scored the highest for the statement ‘I am confident in involving family and carers in risk assessment and safety planning’ (98.5% of participants).

Post-questionnaire findings revealed similar findings with 98% of participants agreeing with the above statement. However, 51% of participants now were now in strong agreement which had increased from 37% at the pre-questionnaire stage.

Data from Question 4

‘I am confident about when I can and can’t share information with family and carers.’

Pre-questionnaire findings demonstrated that the vast majority of participants (98%) were in agreement that they felt confident about when they could and could not share information with family carers.

Post-questionnaire findings similarly showed that 98% of participants were in agreement with the above statement. However, the percentage of participants who strongly agreed had risen from 40% pre-questionnaire to 51% postquestionnaire.

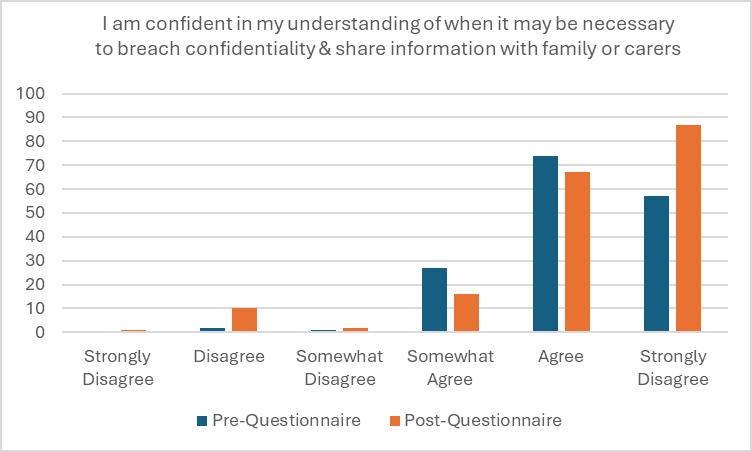

Data from Question 5

‘I am confident in my understanding of when it may be necessary to breach confidentiality and share information with family or carers.’

Pre questionnaire findings revealed that a high proportion of participants (98%) agreed to some extent that they felt confident in understanding when it may be necessary to breach confidentiality and share information with family and carers. Post-questionnaire findings indicated that the overall proportion of participants who were in agreement with the above statement had decreased slightly to 93%. However, the percentage of participants who strongly agreed with the above statement had increased from 35% (pre-questionnaire) to 47% (post-questionnaire).

Data from Question 6

‘I consider my professional duty with regard to patient confidentiality to be a barrier to involving family or carers in patient care.’

In the pre-questionnaire, 20% of participants agreed or somewhat agreed with the statement, while this figure decreased to 10% in the post-questionnaire. Conversely, the proportion of participants who disagreed or strongly disagreed increased from 50% in the pre-questionnaire to 60% in the post-questionnaire. Notably, those who selected ‘Disagree’ rose from 35% to 45%. These changes suggest that the modules were effective in clarifying how confidentiality can be maintained while still engaging family or carers in patient care.

Data from Question 7

‘I am confident in my knowledge and understanding of the Triangle of Care’.

Pre-questionnaire findings showed that the vast majority of participants (92%) felt confident in their knowledge and understanding of the Triangle of Care. In contrast, only (8%) of participants disagreed to some degree with this statement. Post-questionnaire findings indicated similar results overall with 97% of participants in agreement with the above statement to some extent. However, the percentage of participants who strongly agreed with this was found to have risen from 32% (pre-questionnaire) to 47% (post-questionnaire).

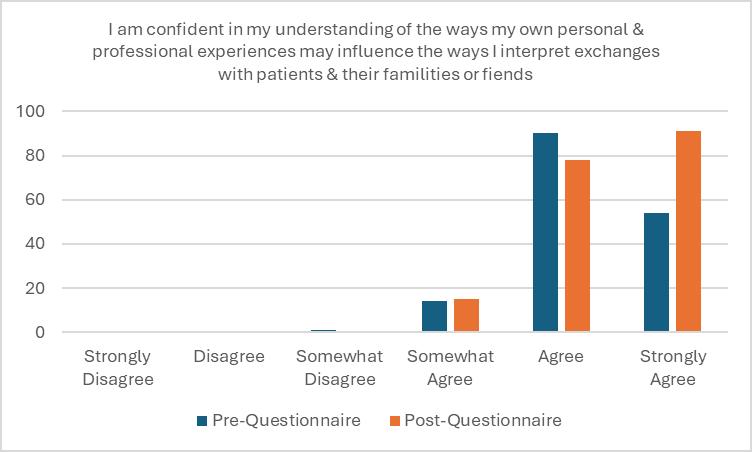

Data from Question 8

‘I am confident in my understanding of the ways my own personal and professional experiences may influence the ways I interpret exchanges with patients and their family or friends.’

Pre-questionnaire results showed that the significant majority of participants (99.5%) agreed to some extent that they were confident in their understanding of the ways their own personal and professional experiences may influence the ways they interpret exchanges with patients and their family or friends. Post-questionnaire revealed that participants were all in agreement (100%) with the above statement to some degree. What is more, the percentage of participants who strongly agreed had increased from 34% (pre-questionnaire) to 50% (post-questionnaire).

Data from Question 9

‘I am confident in my understanding of the ways that assumptions I hold may impact how I work with patient and their family or carers.

Pre-questionnaire findings demonstrated that 99% of participants agreed to some extent that they were confident in understanding how assumptions they may hold could impact their work with patients and their family or carers.

Post-questionnaire findings showed similar findings overall with 98% of participants indicating that they were in agreement with the above statement. However, the percentage of participants who strongly agreed were found to have increased from 34% (pre-questionnaire) to 47% (post-questionnaire). This increase suggests that the training had a positive impact on enhancing clinicians’ confidence in recognising and addressing their assumptions.

3.2 Qualitative Findings

Individual Interviews

Four individual interviews were conducted with healthcare professionals who met the inclusion criteria. The interviews were conducted online due to accessibility for the healthcare professionals as participants were based in different healthcare sites. The interviews were conducted on Microsoft Teams and lasted for up to an hour, allowing participants enough time to contribute to the depth of the discussion.

The findings from the interviews are themed in line with the evaluation questions in the section below. Excerpts from participants` narratives of the interviews are used to support the findings. The abbreviations e.g., ‘P1’, stands for Participant 1, and refer to the interviewed participants. This abbreviation is used at the end of each excerpt to identify the source.

Individual Interview Demographics

P1 - Nurse Consultant (Female)

P2 - Recovery College Tutor (Female)

P3 - Clinical Psychologist (Female)

P4 - Clinical Psychologist (Male)

Individual Interview Findings

How do healthcare staff use the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources?

Some participants used the video links in the training guide in their clinical risk training and carer training and others suggested that the videos and resources could be used in staff reflection/supervision groups.

‘And time wise that’s kind of easier. But also you know you’re bouncing ideas off other people as well within the team and you’re hearing the concerns the individual is you know was obviously a lot more comprehensive ‘(P3)

In addition to the peer conversations and learning, participant 3 found that the group sessions were more productive in terms of time management for the team and ensuring that there was shared learning for all colleagues.

The videos were highly rated by all the participants stating:

‘Very thought provoking. The use of the videos. although short was extremely powerful and helps to really highlight the identified areas.’ (P1)

The participants followed the order of the modules when completing them but were aware they could complete them in any order. There was recognition that some of the e-learning topics were emotive, and this could require debrief and time for reflection.

‘The content is emotionally heavy...In lots of ways, and I think that’s why it was so useful to have the options of doing one module and being able to come back to it.’ (P2)

Participant 3 suggested that opportunities for debriefing on the e-learning content could be in clinical supervision sessions.

‘And I have supervision on the crises line anyway. So, you know, my supervisor also would have done the training as well. So, and I think we did have a, we did have a bit of a conversation about it.’ (P3)

The main challenge with completing the modules was the time commitment due to the workload demands for healthcare professionals and the need for staff to have protected time to complete the modules.

‘Actually doing the reflection and thinking about the fear video and not enough time in the day to write your notes and stuff like that. I’d worry whether staff without support would actually be utilising it to the best.’ (P1)

Participant 3 observed that, although staff had completed the e-learning modules, they may not have fully engaged with all the content. However, staff acknowledged the value of the modules and indicated they would refer back to the modules when necessary.

‘I think you know, the people looked at the training materials, they looked at the videos, but I don’t think they looked at the reference materials. It’s just a kind of matter of time and it’s something that what would happen is certain people would go back and look at it on a different occasion. I think when they felt they had a bit more time to do so.’ (P3)

The participants stated that due to the number of modules, there was a risk of staff not adequately engaging with the content.

‘I would worry that it get a bit lost in translation if people are rushing to try and complete it’ (P1)

The participants had mixed reviews on whether the Life Beyond the cubicle modules should be part of mandatory training. Participants 1 and 4 felt that there would be more meaningful engagement if staff had a choice in completing the modules or if they were included in staff induction or another planned staff training. However, Participants 2 and 3 reported that the e-learning modules were important for all mental health professionals and should be included in mandatory training.

‘...But I do think that there is a real opportunity if it were included as part of essential or mandatory.’ (P2)

Participant 4 suggested reviewing the module lengths to ensure that they were consistently bite size to aide completion.

‘...that I thought about was the time, so I don’t why but I but I so in my head somehow each model was about half an hour and that’s what I was ready to do. And then I don’t know which module it is, is 3 or four. I think becomes an hour suddenly.’ (P4)

What learning, if any, do the healthcare staff gain from The Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources?

All the participants agreed that the modules were impactful in terms of supporting staff to reflect on their practice and working collaboratively with family carers and patients.

Participant 2 shared that, the design of the material within the e-learning module was helpful as there were opportunities to write reflections which enabled them to internalise the learning.

‘I thought that was really important for me. I really like the fact that it was internalised. You could do the reflective writing at the same time, I thought that was really, really helpful.’ (P2)

Participant 1 said that the content was clinically relevant and addressed key topics which cause conflict and uncertainty for staff, adding that the content was clinically relevant because it was a close representation as to how staff felt when caring for patients in mental health distress.

‘Actually, is a really real representation of how staff feel. I do feel that that is a reasonable, obviously slightly different in each area….’ (P1)

Similarly, Participants 2 and 3 reported that the actors were realistic in their interpretation of the case studies, and there is a sense in which participants two and three were able to reflect on the work they’ve done with previous patients in light of the new training they have received.

‘The videos were personal stories and when they were acting actors. And I think that some of the personal stories, you know, reminded me of particular clients and they reminded me of similar stories that I have encountered… it sort of provoked reflection about some of the some of the clients that I’ve worked with.’ (P3)

Participants valued the content and the design of the e-learning modules, highlighting the effectiveness of the videos and the clarity of the instructions. They recognised the relevance of the topics covered, with Participant 3 specifically noting the module on confidentiality as particularly valuable.

‘Caldicott Guardian mentioned in there in the training was really helpful because I think there’s probably not enough support around thinking about what confidentiality means and how you can get information’. (P3)

The participants highlighted areas for development in the e-learning modules such as incorporating some inpatient content.

‘Reflection because obviously it’s thinking about containing people in the community and those, you know, the transfers of family and carers and of those fears that are transferring to the person. So I did wonder if an inpatient staff was watching it, whether they would get the same benefit of it.’ (P1)

What impact does the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources have on clinical practice?

The interviews suggested that the Life Beyond the Cubicle e-learning resources were effective in supporting the participants to reflect on their practice. The participants in leadership roles found that the training provided them with a valuable tool to facilitate group reflection and peer learning.

‘It actually got my brain thinking and reflecting about my practice and obviously the practice of my colleagues and what some of those assumptions are.’ (P1)

Participant 3 acknowledged that there are competing priorities within healthcare services and the e-learning modules assisted refreshing her team on the importance of involving family /carers in their work with patients.

‘For our clients and often that sort of dictated by whatever current trends are in the in the in the NHS. So, it was just a really good opportunity just to kind of freshen our focus and think, hang on, who can we speak to, and how soon can we speak to them and how can we best do that to enable them to kind of speak freely.’ (P3)

Participant 4 acknowledged that the e-learning modules supported staff to reflect on their innermost feelings and frustrations which was important for developing self-awareness, shared learning with peers and informed real time practice.

‘People talking about their own examples, experiences, people that we’re seeing right then that week, you know, and didn’t know what to do, didn’t know how to speak to people, were concerned about who they included. And so on it was live…’(P4)

Participant 2 reported the benefits of engaging in the reflection exercises in the Life Beyond the Cubicle e-learning modules, and advocated for healthcare professionals to actively engage in clinical supervision so that they could reflect on their practice, learn, and enhance care and their own wellbeing.

‘So I think a lot of it’s about the courage and the confidence and having really good supervision for anybody in these roles, so that there’s a sort of sense that there’s a shared learning,. Kind of deepening of our reflexive practice and a kind of reinforcement that we’re all doing the best we can and that if in order to make good changes we have to have difficult conversations.’ (P2)

This new sense of self-awareness empowered participant 2 to be more proactive about championing the family carer voice within the multidisciplinary team as well as with patients and their families.

‘So there was something about that that felt really empowering because instead of being frightened to talk about it..., It’s definitely made me look for more opportunities. I’m much more likely to say is there a role for me working with the carers?’(P2)

The e-learning modules helped Participant 2 to be more proactive to not only champion the family carer voice but also to seek out opportunities to introduce initiatives to promote family carer activities within her healthcare trust. These opportunities included a family carer workshop and co-design of a training workshop and creating a directory of local charities and organisations that could support family and friends’ carers.

‘The other thing that it did is it encouraged me to offer to be a carer’s champion for the trust I because of watching it, I offered. I put my hand up to do the carers workshop.’ (P2)

3.3 Perspectives on Module Content

The post-questionnaire had additional questions which aimed to assess the participants’ views on the e-learning module. The findings from these questions are presented below with a brief overview of key findings.

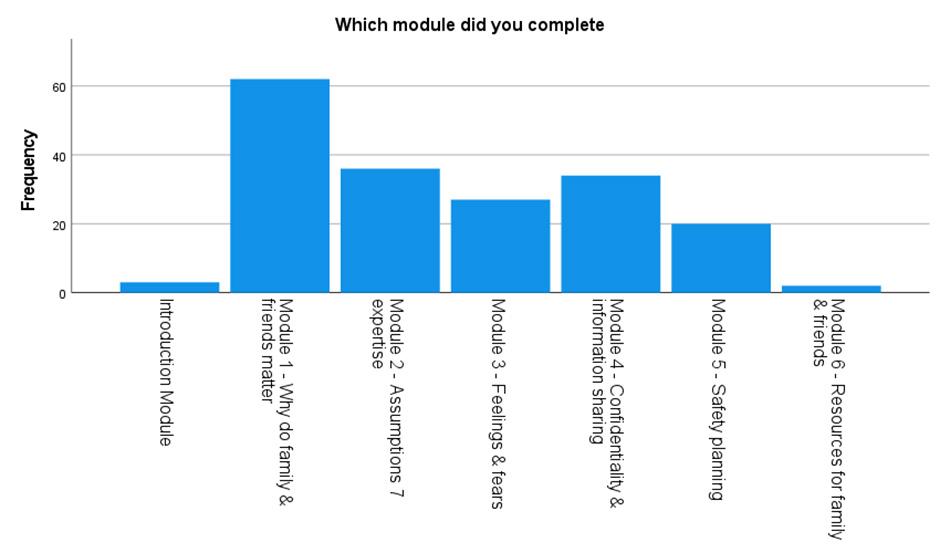

Participants responded from across the full range of e-learning modules (please see the diagram below). The participants did not have to complete the modules in a standard order and not all the participants would have completed the postquestionnaire. In reviewing the data on the modules completed, it would appear that Module 1, 2, 4, 3 and 5 were the most popular.

99% of participants responded that the module they had completed was relevant to their current / future practice. Of these participants, 63% reported that the module was extremely relevant to their current / future practice.

The vast ajority of participants (90.2%) felt there were parts of the module they had completed that were beneficial to their practice. 89% of participants felt that there were parts of the module they had completed that were important to share with colleagues. Only 11% of participants reported that there were not any parts of the module that they felt important to share with colleagues

The feedback from participants highlights the emotional impact of the training content. One participant noted, “Sad when hearing the negative experiences especially of the lady who said she would never ring the crisis team as they don’t care.” Another shared, “The video of the young carer was very emotional for me - I felt concerned of how isolating it must feel, and the weight/responsibility of not knowing whether your loved one is safe (even whilst you are away at school for the day). It made me want to do something to help young carers.”

Additionally, the distressing experiences of service users were evident in comments such as, “The video re the person that had been suicidal and was sent home alone with no one checking,” and “distress that service users and carers felt when dealing with a crisis and having to navigate an unhelpful system.” These reflections underscore the importance of the training in fostering empathy and understanding among clinicians. As one participant expressed, they now “feel more understanding why carers feel frustrated at times.”

Did any aspects of the module alter your views about working with family members?

The data indicates a nearly even split among participants regarding the impact of the module on their views about working with family members, with 49% reporting a change in perspective and 51% not experiencing any change. This division highlights the varied responses to the module’s content. One participant emphasised, “Don’t be scared to involve carers/family members - it’s imperative that we do,” underscoring the importance of family involvement in care. Another noted, “Support and care are important in our life,” reflecting a general appreciation for the role of support systems.

The module’s discussion on handling first incidents of psychosis was particularly impactful for some, as one participant shared, “I think treating everyone as if it is their first time seeking help for this and overexplaining resources, support available, what will happen going forward may be useful.” This approach aims to ensure that no assumptions are made about the individual’s knowledge or preparedness. Additionally, the importance of communication style was highlighted: “Thinking about how often I am ‘opening up the discussion’ vs closing it down... It is useful to consider alteration of your communication style to accommodate the person and their needs in the specific moment.”

Participants also reflected on the value of admitting uncertainty, with one stating, “That ‘not sure’ responses are okay!!... I will worry less about my response being ‘not sure’ and take this pause to get more information.” This perspective encourages seeking additional input when needed. The module also raised awareness about approaching family and friends regarding service users, as one participant noted, “Made me more aware of how to approach family and friends regarding service users.” Finally, the gravity of involving family opinions was emphasised: “It hammered home the importance of taking their opinions on board and that there are real life and death consequences to these decisions.” This underscores the critical nature of considering family input in care decisions.

Are you planning to make any changes to how you work with patients and family members as a result of working through this module?

The data reveals that a considerable majority of participants (77%) plan to make changes in their approach to working with patients and family members after completing the module, while only 23% do not intend to make any changes. This indicates a strong impact of the module on participants’ practices. One participant mentioned, “Tend to do this already,” suggesting that some of the recommended practices were already in place for certain individuals. Another echoed this sentiment, stating, “Most of the techniques we already use them.”

The importance of involving various stakeholders in safety planning was highlighted by a participant who noted, “stay involving patients, family, friends, staff in planning for their safety.” This underscores the collaborative approach needed in care. Additionally, the module served as a reminder of the need to consider safety even with limited resources, as one participant reflected, “just a reminder though of the need to consider safety even with few resources available to use and engage carers in this constantly.”

Participants also emphasised their ongoing commitment to involving family members, with one stating, “I always try and involve family/carers where possible and will continue to do so.” Another participant mentioned specific actions they plan to take, such as “Checking the services available for young carers. Reviewing the Caldicott principles.” This shows a proactive approach to improving care practices.

Including reflections on carers in supervision sessions was another key takeaway, as one participant shared, “Include reflections with regards to carers, in my supervision.” Finally, the importance of emphasising the role of carers was noted: “ “Involve them even more proactively. Ask them how their relatives difficulties are impacting on them..” This highlights the need for continuous engagement with carers to enhance the support provided to patients.

Participants shared various comments about their engagement with the LBC modules, highlighting both their enjoyment and areas for improvement. One participant expressed appreciation for the self-care aspect, stating, “I really appreciated the ‘self-care’ moment added in - I think often healthcare professionals can be quite hard on themselves, so this moment to notice the ‘good’ things you have done, alongside the fact that you can always do more to improve, was nice.” This underscores the importance of self-reflection and acknowledging positive actions.

Effective communication was another key theme, with one participant noting, “Effective communication and building rapport.” The variety of scenarios was also appreciated, despite some technical issues: “true and false quiz slow to respond to clicks, large mixture of scenarios was good to have.” This indicates that diverse content is valuable, even if there are areas for technical improvement.

The reflective nature of the modules was praised, with one participant suggesting, “I think this is a great model - really helpful to reflect - maybe link a word document for reflections to be collated?” This highlights the desire for tools to facilitate ongoing reflection. The ability to save and review responses was also valued: “I like the Freedom to speak up function of being able to download a copy of the script and save a PDF of open text answers to reflective questions.”

Participants found the use of different mediums and the modular approach to be engaging and user-friendly, as one noted, “The use of differing mediums and length of each is really well balanced. Very engaging. Very user friendly. Modular approach is always welcomed by practitioners as it fits with clinical capacity.” Overall, the feedback reflects a positive reception of the modules, with suggestions for enhancing the reflective and technical aspects.

4. Conclusion

The Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources have had a demonstrable and positive impact on healthcare professionals working across both community and inpatient settings. Widely adopted as part of continuous professional development during the pilot phase, the modules were valued for their clinical relevance and practical application. While views differed on whether the training should be mandatory, there was strong agreement on the significance and utility of the content. As Cusack et al. (2015) highlight, fostering authentic relationships with family carers is essential for delivering recoveryoriented care—an ethos that is deeply embedded in the design of these modules.

A key strength of the modules was their ability to cultivate reflective practice. The e-learning platform provided a psychologically safe and engaging space for staff to critically examine their own beliefs, assumptions, and behaviours in relation to family carer involvement. The structured format encouraged a logical progression through the material, while the integration of lived experiences added emotional resonance and practical insight. Participants consistently reported that the modules prompted them to pause, reflect, and reconsider how they approach complex issues such as confidentiality, consent, and risk management in their day-to-day practice.

This reflective process was further enhanced through peer discussions, which allowed staff to share experiences, challenge perspectives, and collaboratively explore ethical dilemmas. These conversations were considered by participants to be instrumental in deepening understanding and fostering a more nuanced approach to care. However, time constraints within clinical environments were considered to be a notable barrier to full engagement. This highlights the importance of employers providing protected time for professional development or embedding the content into existing training and supervision structures (Lemieux-Cumberlege & Taylor, 2019).

Participants reported increased confidence in involving family carers, particularly in risk and safety planning—an area where carers often play a critical role in identifying early signs of relapse (Bradley & Green, 2018).

Post-training data showed a 14% increase in those who strongly agreed with feeling confident in this area. The participants responses suggested that the modules also encouraged deeper reflection on confidentiality, with the aim of helping staff navigate the ethical and legal complexities of information sharing. As Giacco et al. (2017) suggest, training is most effective when it incorporates the lived experiences of carers, a feature that enriched peer discussions and supported practical problem-solving. Woof et al. (2019) further emphasise the delicate balance healthcare professionals must maintain when working with complex family dynamics.

Beyond knowledge acquisition, the modules inspired meaningful behavioural change. A significant proportion of participants (77%) indicated plans to adjust their practice to better involve family carers, and 99% found the content relevant to their current or future roles. The training also enhanced emotional awareness, enabling staff to better understand and respond to the experiences of families, thereby having the potential to promote more compassionate and inclusive care.

In summary, feedback from participants who took part in the evaluation of Life Beyond the Cubicle suggests that the modules can be a valuable and impactful resource in advancing reflective practice and strengthening family carer involvement in healthcare. To maintain and expand on these positive outcomes, it is recommended that healthcare organisations continue to integrate these principles into routine clinical practice through training, reflective supervision, and organisational support.

5. Recommendations

1. Integrate Training into Professional Development: Healthcare organisations should incorporate the Life Beyond the Cubicle modules into staff training. Given the positive feedback on the content’s relevance and the importance of involving family carers, making this training a standard part of staff development can promote trust wide implementation.

2. Provide Protected Time for Training: To address the challenge of time pressures in clinical environments, employers should allocate protected time for healthcare professionals to complete the e-learning modules. This could be achieved by scheduling dedicated training sessions or integrating the modules into existing staff development and clinical supervision schedules.

3. Foster Reflective Learning and Peer Discussions: Encourage reflective learning and peer discussions as part of the training process. The modules have shown to be effective in promoting nuanced thinking and emotional atonement to family carers’ experiences. Structured opportunities for staff to discuss their reflections and share strategies with peers can enhance learning outcomes and support the practical application of new skills.

4. Monitor and Evaluate Impact: Implement ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the training’s impact on clinical practice. Collecting data on changes in staff behaviour, patient outcomes, and family carer involvement can help identify areas for improvement and ensure the training remains effective and relevant.

References

Bradley, E., & Green, D. (2018). Involved, inputting or informing: “Shared” decision making in adult mental health care. Health Expectations, 21(1), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12601

Cusack, E., Killoury, F., Nugent, L. E., Yesufu-Udechuku, A., Harrison, B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Young, N., Woodhams, P., Shiers, D., Kuipers, E., & Kendall, T. (2015). Interventions to improve the experience of caring for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 206(4), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147561

Lemieux-Cumberlege, A., & Taylor, E. P. (2019). An exploratory study on the factors affecting the mental health and well-being of frontline workers in homeless services. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(4), e367–e378. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12738

Woof, V. G., Ruane, H., Ulph, F., French, D. P., Qureshi, N., Khan, N., Evans, D. G., & Donnelly, L. S. (2019). Engagement barriers and service inequities in the NHS Breast Screening Programme: Views from British-Pakistani women. Journal of Medical Screening. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141319887405

Yesufu-Udechuku, A., Harrison, B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Young, N., Woodhams, P., Shiers, D., Kuipers, E., & Kendall, T. (2015). Interventions to improve the experience of caring for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(4), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147561

Appendix 1 Overview of the Life Beyond the Cubicle Resources

1. Five e-Learning modules including an Introduction, and Resources for family carers.

Resources were designed with the aim of enabling healthcare professionals to reflect on effective ways to engage families/friends when assessing and treating a service user during an acute mental health episode.

The resource was designed to both equip and encourage healthcare professionals to work collaboratively with carers. The modules use bespoke short films created by professional actors to provide video and audio videos to act as a stimulus and to share real lived experiences to bring the lived experiences of patients and families to life.

E-learning Modules

- Introduction (includes guidance notes on using the resources)

- Module 1 Why do Families and Friends matter?

- Module 2 Assumptions and Expertise

- Module 3 Feelings and Fears

- Module 4 Confidentiality and Information Sharing

- Module 5 Safety Planning

- Resources for Family and Friends

2. A Handbook to support facilitated group-based training.

The handbook incorporated film and audio stimulus materials from the e-Learning modules to suggest ways the staff can support group-based learning on the themes of the eLearning modules. The handbook was designed for use by clinical practice educators, ideally co-facilitating with a trained and supported family carer. This aspect of training enables richer dialogue and discourse between healthcare professionals to promote deeper reflections on experience and consideration of the facilitators and barriers to effective and authentic family involvement, with a view to taking positive action when back in practice.

Appendix 2 Full Title of Research:

An Evaluation of the impact of The Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources developed for health professionals working with people in mental health crisis.

Individual Interviews Semi-Structured Questions

The absolute minimum number of questions will be asked to allow participants to tell their stories.

The researchers will commence the interview process by introducing themselves, and clearly stating its purpose. Although confidentiality issues contained in the information leaflet and consent form has been explained to the participant, these will be reiterated. Permission to record the conversation on Ms Teams will be sought underpinned by a clear rationale. Participants will also be encouraged to sign consent forms. This will be followed by the use of questions.

1. Tell me about your experience of working with carers? (Prompts: heard about it?)

2. In your opinion, what would support working more collaboratively with cares? (Prompts: tell me more, why)

3. In your opinion, what would be a barrier when working collaboratively with carers? (Prompts: tell me more, why)

4. Tell me about the Life Beyond the Cubicle e-learning modules you completed? (Prompt: why?)

5. What impact did the e-learning modules have for you? (Prompts: clinically, personally, tell me more, why)

6. What impact did the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources have on your clinical practice?

7. What learning, if any, did you gain from the Life Beyond the Cubicle learning resources

8. What did you think about the format/presentation of the e-learning modules? (Prompts: why?, tell me more, how)

9. Is there anything you would change in the modules? (Prompts: tell me more, why)

10. Any other comments?

Appendix 3 Other Sources of Evaluation Feedback

In addition to the BNU evaluation of the project, the Life Beyond the Cubicle Co-Creation Group also conducted their own independent review of the e-learning modules. The findings from this evaluation are shared in this section of the report.

Qualitative insights into the Resources

The Evaluation Team had access to a number of sources of qualitative information about how the resources were developed and used:

In the development and initial testing phase of the work:

1. The Co-Creation Group process as reported to the Advisory Group

2. The discussions at the Advisory Group meetings, notes of the meetings and papers presented to meetings, which included early drafts of modules

3. Feedback collected from the first pilot at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, provided to the evaluation team, presented to the Advisory Group and later to a conference at BNU in June 2024

In the wider testing phase of the work:

4. Online meeting discussions held at Stakeholder/Partner meetings of those NHS Trusts that tested the resources in 2024; these meetings were convened by the Evaluation Team leader

5. Structured Interviews with 4 people from the NHS Trusts who tested the resources

6. Feedback from 4 individual reviewers received by the project co-ordinator, provided to the evaluation team, and presented to the Advisory Group meeting of July 2024, as part of a detailed paper on feedback and revisions made.

The Co-Creation Group

The Co-Creation Group comprised patients, family carers and clinicians. The Group met regularly to create the first draft of the resources. Their suggestions for content were based on the aspects of care that group members found helpful, the aspects group members thought needed to improve and the barriers group members identified to such improvements.

The scenarios and case studies use in the resources were all generated by members of the Co-Creation Group.

Group members with lived experience as patients and as family carers contributed to audio and video materials used in the resource.

The Advisory Group meetings

Members of the Advisory Group contributed to suggestions of content and of approach. Their role was to be critical friends, bringing a diverse range of expertise and experience from across the mental health system. They reviewed early drafts of materials and offered suggestions for elements that needed to be strengthened.

The combination of the Co-Creation Group and Advisory Group contributions set the parameters of the resources, and agreed the module titles and content.

The first pilot at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust

This pilot checked the relevance of the modules, obtained feedback on aspects that required amending or correcting and confirmed that the overall structure of the resources was effective.

Feedback from this testing was organised around two questionnaires: one at the start of each module and a second at the end. The second questionnaire allowed for individuals to write free text in response to some of the questions. The results gave some insights into whether or not people’s views changes/developed after they had worked through the modules.

A report to the Advisory Group of this feedback showed 34 feedback responses, from a possible total of 51 who completed the start quiz about their confidence levels on starting a module. Of the 34 responses

• 21 said it was very relevant

• 10 said extremely relevant

• 3 said somewhat relevant.

The feedback overall was very positive. It was used to guide the revisions that were made before wider testing. A report to the Advisory Group confirms that spelling errors and typos were corrected, the design was tidied and made more consistent, and some repetition was removed.

The second questionnaire asked whether, and what changes learners were planning to make having worked through the modules. Some examples of their responses that were reported to the Advisory Group include:

• Yes, more collaborative work would be extremely helpful as I feel family and friends are more aware of the changes, they see in those they care for. Getting their viewpoint, support and understanding would be extremely useful as well as making sure they are supported and not alone dealing with it by themselves.

• Be clearer with family members around what services can and can’t provide

• Make more time to listen to carers and family.

• Safety planning needs to be inclusive of carer’s when possible.

• I will try to make sure I check in more with family members, and consider if I need to speak to patients or their close ones on their own to get more information

• I will try to consider more what my values are and how my actions can align well with them.

• I will ask how the patient feels about their involvement more often, and will explore and revisit this if appropriate.

• Be more proactive in obtaining friend/family/carer information and revisiting the importance of their involvement (if appropriate and safe) for their mental health recovery and wellbeing of the people in their life

• It will make me think about the feelings and wishes of both patients and families a lot more

• I need to actively seek consent to reach out to family, ask what support they need, suggest to ward manager that we should dedicate someone to be a family champion

• Try and spent time talking to the family member alone

Comment

It is clear from the subsequent evaluation findings that the process used to develop the resources ensured that they were rooted in the needs of clinicians working with people and their families in a crisis.

Stakeholder/Partner Meetings

These meetings were convened by the Evaluation Team to support the testing and feedback processes. The discussions offered suggestions to encourage staff in the Trusts that were testing to sign up to use the resources. They also identified two specific scenarios in the modules that needed to be clarified. These clarifications were made and reported to the Advisory Group.

Feedback from four individual reviewers

The project team received feedback from four people who were not part of the NHS Trusts testing the resources. One reviewer did so on behalf of NHS England, the other three offered insights from their own perspectives. The NHS England reviewer commented:

• Overall, my impressions of these modules are that they are very accessible. I also felt that these showed a good understanding of the pressure staff are under at the moment, and these modules reflect that and do it in a way which is sensitive and caring.

• The fact that in each module there are prompts to take some time to reflect is of particular importance to clinical practice.

• I also felt that the information was presented throughout in a non-judgmental and caring way, which is important as it means staff will be able to access these modules knowing that there is a desire to educate and support and not blame.

In a report to the Advisory Group in July 2024, the project coordinator identified all the changes proposed by the individual reviewers, and from the Evaluation team, and showed which changes had been incorporated into the final version of the resources.

High Wycombe Campus

Queen Alexandra Road

High Wycombe

Buckinghamshire HP11 2JZ

Aylesbury Campus

59 Walton Street

Aylesbury

Buckinghamshire HP21 7QG

Uxbridge Campus

106 Oxford Road

Uxbridge

Middlesex

UB8 1NA

Telephone: 0330 122