BSBI CONTACTS

President PAUL ASHTON

Chair of the Trustees

Hon. General Secretary

SANDY KNAPP

Dept of Biology, Edge Hill University, St Helens Road, Ormskirk, L39 4QP president@bsbi.org +44 (0) 1695 650931

Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD chair@bsbi.org +44 (0) 942 5171

BARRY O’KANE hongensec@bsbi.org

Company Secretary and registered address MKS LLP Chartered Accountants 4 Beaconsfield Road, St Albans, AL1 3RD +44 (0) 1727 838255

Chief Executive JULIA HANMER 65 Sotheby Road, London, N5 2UP julia.hanmer@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7757 244651

MEMBERSHIP SUPPORT AND ADMINISTRATION

Hon. Membership Secretary (subscriptions and changes of address) and BSBI News distribution

Finance Manager (all financial matters except Membership)

Communications Officer (including publicity, outreach and website; British & Irish Botany)

Fundraising and Engagement Manager

Administration Officer (general enquiries about BSBI’s work)

Hon. Field Meetings Secretary (including enquiries about field meetings)

Panel of Referees and Specialists (comments and changes of address)

SCIENCE AND DATA

Head of Science

Scientific Officer (& Panel of VCRs –comments and changes of address)

Database Officer

Data Support Officer

COUNTRIES AND TRAINING

Countries Manager

Training Coordinator (FISC and Identiplant)

England Officer

GWYNN ELLIS 41 Marlborough Road, Roath, Cardiff, CF23 5BU gwynn.ellis@bsbi.org +44 (0) 2920 332338

Please quote membership no. on all correspondence.

JULIE ETHERINGTON Church Folde, 2 New Street, Mawdesley, Ormskirk, L40 2QP

julie.etherington@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7944 990399

LOUISE MARSH louise.marsh@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7725 862957

SARAH WOODS 23 Bank Parade, Otley, LS21 3DY sarah.woods@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7570 254619

JENNA POOLE jenna.poole@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7404 231178

JONATHAN SHANKLIN 11 City Road, Cambridge, CB1 1DP fieldmeetings@bsbi.org +44 (0) 1223 571250

JO PARMENTER jo.parmenter@tlp.uk.com +44 (0) 7710 252468

KEVIN WALKER kevin.walker@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7807 526856

PETE STROH peter.stroh@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7981 572678

TOM HUMPHREY tom.humphrey@bsbi.org

JAMES DREVER james.drever@bsbi.org

JAMES HARDINGMORRIS james.harding-morris@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7526 624228

CHANTAL HELM chantal.helm@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7896 310075

SAM THOMAS sam.thomas@bsbi.org

Wales Officer (Priority Plants Project) ALASTAIR HOTCHKISS alastair.hotchkiss@bsbi.org

Scotland Officer

Ireland Officer

MATT HARDING matt.harding@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7814 727231

BRIDGET KEEHAN bridget.keehan@bsbi.org +353 (0) 86 3456228

Training Officers (Northern Ireland) JO MULHOLLAND

PUBLICATIONS

BSBI News Editor

British & Irish Botany Editor-inChief

Book sales agent

KIM LAKE jo.mulholland@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7936 303429 kim.lake@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7448 345167

JOHN NORTON bsbinews@bsbi.org +44 (0) 2392 520828

STUART DESJARDINS bib@bsbi.org +44 (0) 7725 862957

PAUL O’HARA Summerfield Books, Penrith, CA11 0DJ info@summerfieldbooks.com +44 (0) 1768 210793

BSBI website: bsbi.org BSBI News: bsbi.org/bsbi-news Tel: +44 (0) 7404 231178

A WORD FROM THE PRESIDENT 1

ARTICLES

More common problems in identification

Bob Leaney 3

Seeing red (or is it blue?) Simon Harrap 10

Trollius europaeus (Globeflower) in the West Pennine Moors and experience in propagation for re-establishment Peter Jepson 13

Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien (Miles) 1817–1891

The Lady of the Flowers David C. Rayment 17

The extinct Glenridding Hawkweed Hieracium subintegrifolium discovered in two new sites at Ingleborough, Yorkshire Brian Burrow 20

BEGINNER’S CORNER

Speedwells (Veronica) Part 3 Mike Crewe 22

ADVENTIVES & ALIENS

Adventives & Aliens News 36

Compiled by Matthew Berry 25

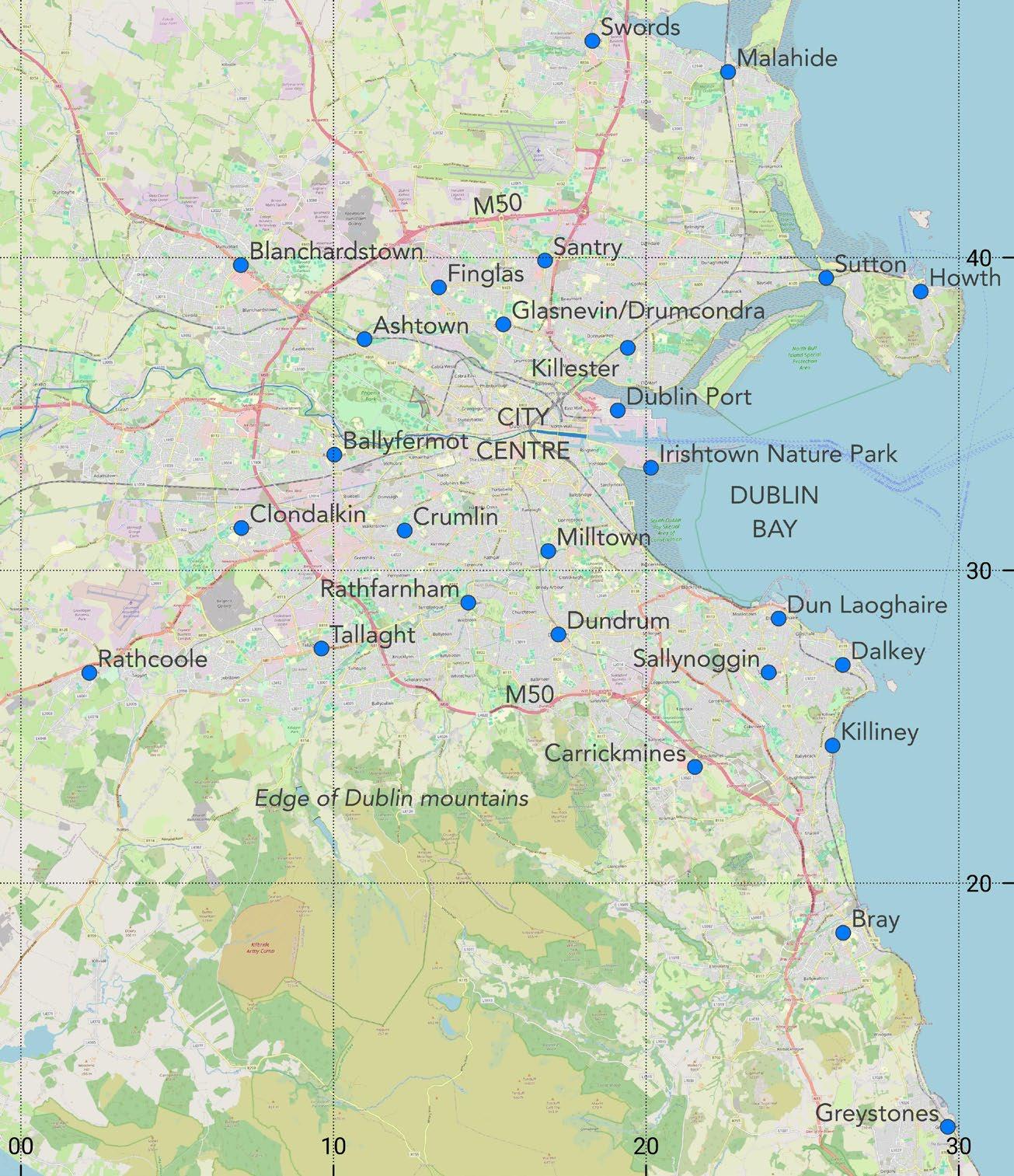

Alien plants in the greater Dublin area in 2024

Sylvia Reynolds 39

Sorbus incana (Silver Whitebeam) on Brownsea Island (v.c. 9), new to Britain and Ireland David Leadbetter 47

An overlooked non-native variant of Primula veris (Cowslip) originating from wildflower seeds and plantings David Broughton 49

SPECIAL ARTICLE

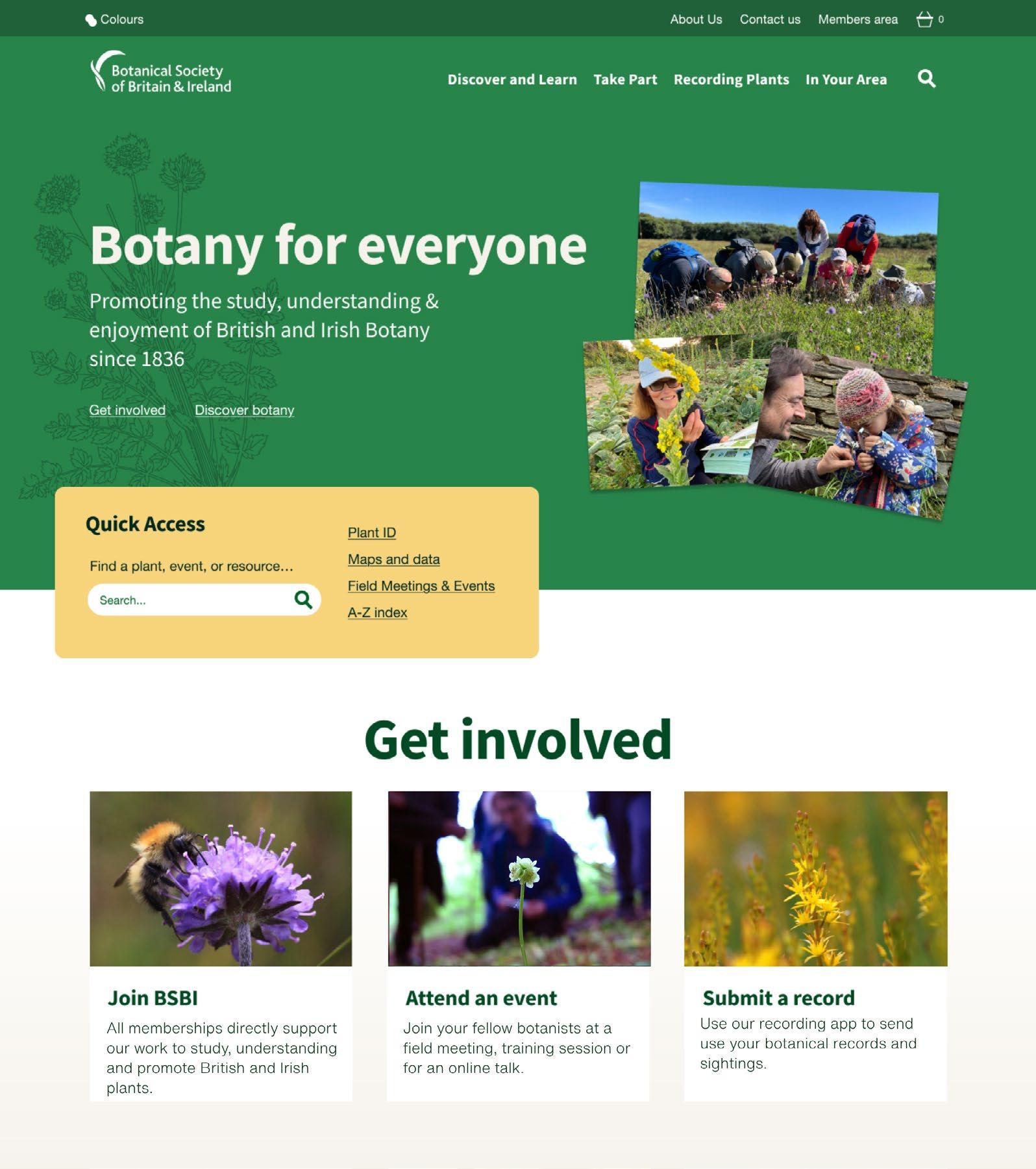

A new BSBI website designed for our botanical community Sarah Woods 53

Contributions for future issues should be sent

NOTICES

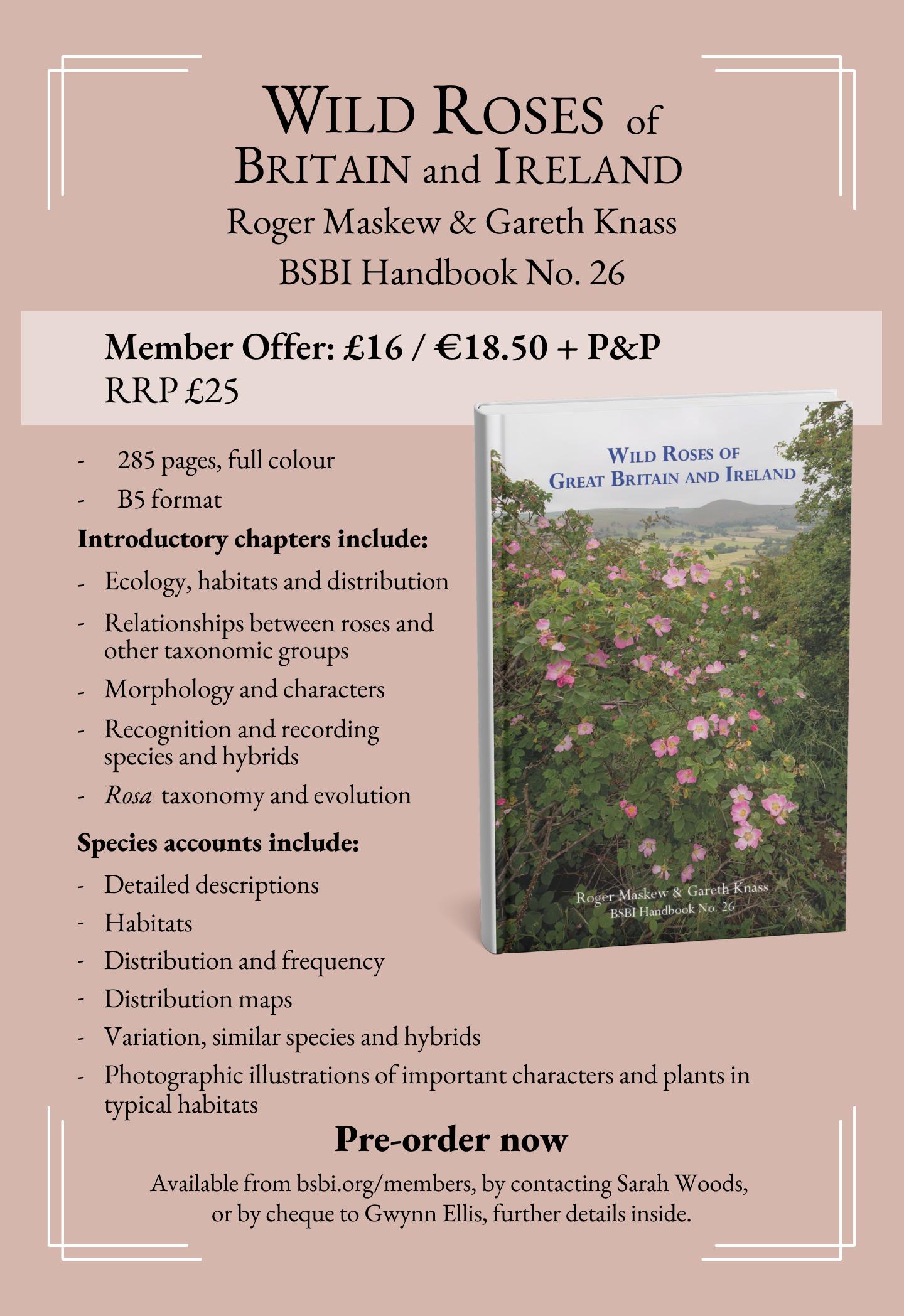

News, events and updates on the work of the BSBI and its members, including: dates of the forthcoming AGM, British and Irish Botanical Conference and New Year Plant Hunt; welcome to new staff; call to join the Skills and Training Committee; update on FISCs in Ireland; Wild Roses of Great Britain and Ireland new handbook; Panel of VCRs; contents of British & Irish Botany 7:2. 56

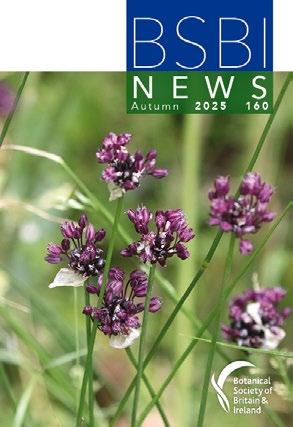

Cover photo: Allium scorodoprasum (Sand Leek), Clun Castle, Shropshire (v.c. 40). John Martin (see Country Roundups, p. 62)

The Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) is the leading charity promoting the enjoyment, study and conservation of wild plants in Britain and Ireland. BSBI is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (8553976) and a charity registered in England and Wales (1152954) and in Scotland (SC038675). Registered office: 4 Beaconsfield Road, St Albans, AL1 3RD. All text and illustrations in BSBI News are copyright and no reproduction in any form may be made without written permission from the Editor. The views expressed by contributors to BSBI News are not necessarily those of the Editor, the Trustees of the BSBI or its committees. BSBI ©2025 ISSN 0309-930X

A WORD FROM THE PRESIDENT

Recording is one of the key areas of work for the BSBI and its members. With the new BSBI Recording App, making such records is now easier than ever. Simply go to the new BSBI Documentation website: docs.bsbi.org to find out more. By the time you read this autumn will be well on its way but that doesn’t mean that recording can cease. Trevor Dines’ excellent new book Urban Botany (see review p. 79) shows that urban plants have a longer flowering season, so explore your local urban area and use the app. The records that you make all flow into the BSBI Distribution Database, to which you have access as a member. It is a fantastic resource covering all of Britain and Ireland and going back over many decades. This means it can be used to understand plant distributions at a geographic and temporal level. I think it is probably the most comprehensive set of national plant records and one in which members can be justifiably proud.

The Database also underpins the second of the BSBI’s key areas, that of publications of books and papers. The new GB Red List for vascular plants by Pete Stroh et al. is due to be published online this autumn as a special issue of British & Irish Botany

EDITORIAL

This issue includes the final part of Mike Crewe’s look at Speedwells (Veronica spp.) for Beginner’s Corner. We would welcome suggestions for topics to cover in future issues – either regarding identification of groups of commoner species – or on other aspects of field botany that haven’t been covered before or could benefit from an update. The series started in 2018 with a look at hand lenses, followed by articles on bud burst phenology of trees and shrubs, ticks, herbaria, ferns and recording grid references with smartphones and GPS. I would always be happy to receive articles from other contributors.

For beginners and ‘improvers’ I am pleased to present another in Bob Leaney’s series of guides to

This details our most threatened plants and is a direct product of the BSBI Database. This autumn also sees the publication of a new BSBI Handbook on Roses (see back cover of this issue and notice on p. 59). This is the second handbook the Society has published this year, hot on the heels of Angus Hannah’s fine Brambles of Scotland. It’s very rare to have two handbooks published in one year. Having been involved as editor with the BSBI Handbooks in the past I know how much effort is needed by the authors to see such a work through to publication, so my congratulations to all involved.

You will be able to view the books and meet other members face-to-face at this years British & Irish Botanical Conference on 29 November at Edge Hill University, Lancashire (see notice on p. 56). This is my home patch and I look forward to meeting many of you there. If books and meeting me aren’t enough to tempt you then let me add that there will be a fine collection of talks and activities on various botanical subjects. How can you resist?

Paul Ashton president@bsbi.org

‘common problems in identification’ – the previous on Mints was back in issue 153 (April 2023). This instalment (p. 3) solves four different problems, three of which relate to vegetative identification of basal leaves and younger leaves of similar-looking species that develop over winter or in early spring. The article should therefore help with botanising over the coming season. More from Bob will be included in the winter issue, due out by late January.

John Norton john.norton@bsbi.org

More common problems in identification

BOB LEANEY

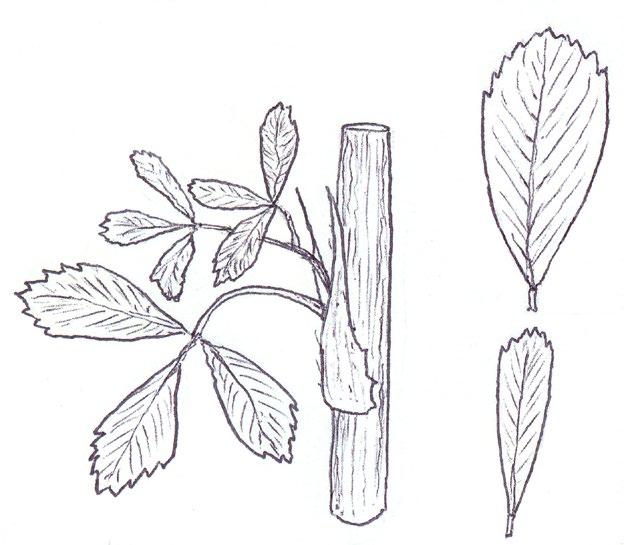

Here are presented some more ‘common problems’ encountered during recording sessions of the Norfolk Flora Group. This time, because the group has for several years been recording in the winter, many of the topics involve vegetative identification of basal leaves found in the winter and early spring.

As always the material presented is the result of notes, photocopies and drawings made on numerous specimens I have taken home after recording sessions, specimens where the group has found it difficult to reach a reliable identification in the field. The diagnostic characters and measurements discussed come from the usual standard texts listed in the reference section but there are also some novel characters and measurements made by myself or others in the group.

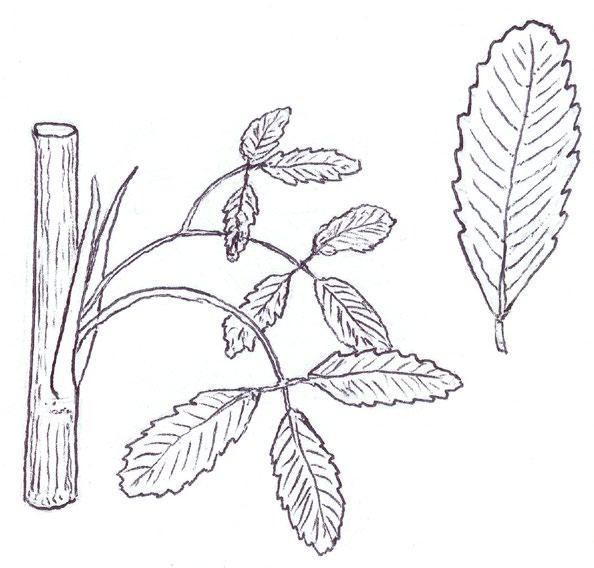

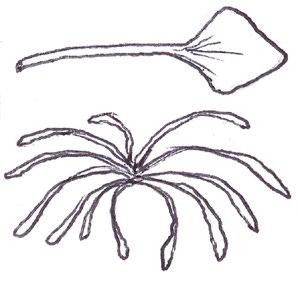

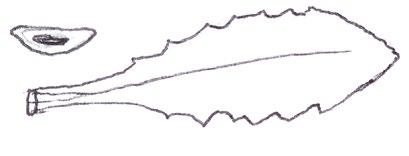

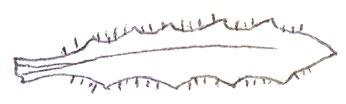

Medicago sativa vs Melilotus spp. (vegetative identification)

Early in the year, before flowering, Medicago sativa subsp. sativa (Lucerne) and species of Melilotus (Melilots) can look very similar, erect in habit and

Basal leaf rosettes (and flowers) of Erophila verna (Common Whitlowgrass). Mike Crewe

with very similarly shaped obovate leaflets. They frequently cause problems with identification, but can in fact be quite readily separated on stipule shape and the distribution of the serrations on the leaflets. Like all Medicago spp. Lucerne has broad-based, clasping stipules and leaflet serrations confined to the distal third or so of the leaflet; in Melilotus spp. the stipules are fine and awl-shaped, without a broad clasping base, and the leaflet serrations extend down onto the lower half of the leaflet (i.e. only the lower third or so of the leaflet is entire edged).

In Medicago subsp. falcata (Sickle Medick) and M. sativa nothosubsp. varia (Sand Lucerne) the stipules will be similar to those in subsp. sativa, but the leaflets are more narrowly obovate and both plants are much less robust and more trailing in habit, rather than erect. It is not possible to separate M. sativa subsp. falcata and nothosubsp. varia vegetatively, and the same goes for the Melilot species.

More common problems in identification

MEDICAGO SATIVA

Subsp. sativa

Broad-based clasping stipules

Serrations confined to distal third of leaflet

c. 1/3

Subsp. falcata and nothosubsp. varia

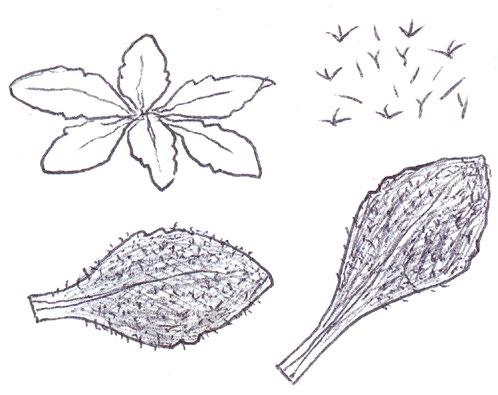

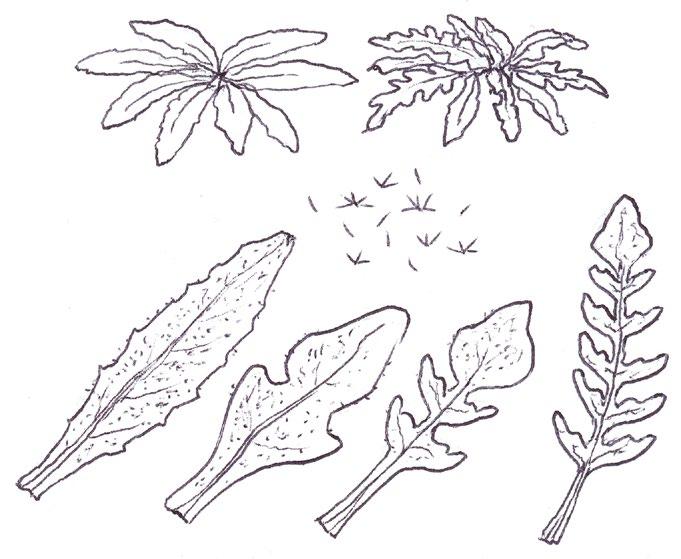

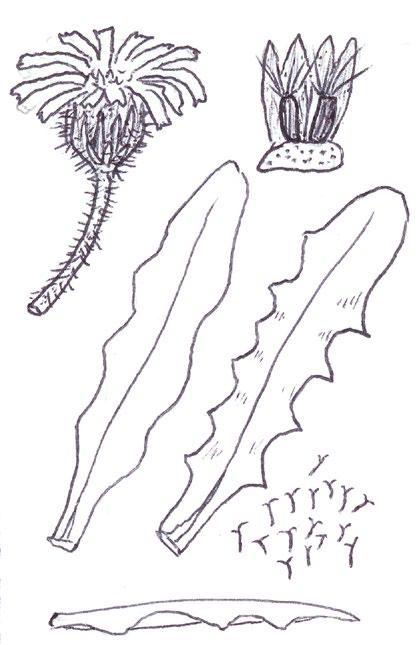

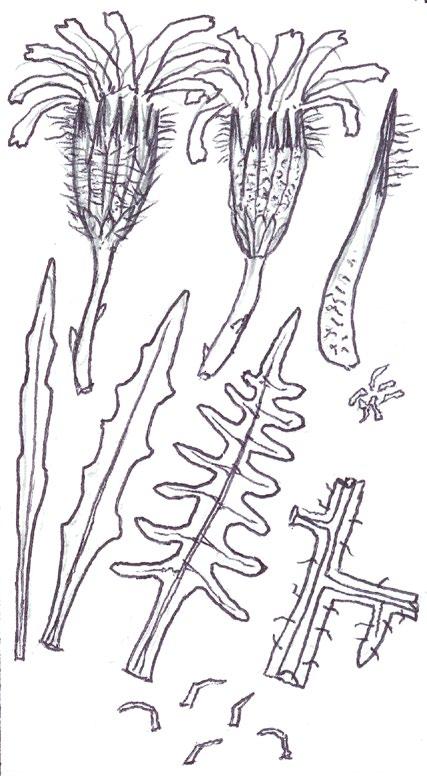

Tiny overwintering and spring basal rosettes

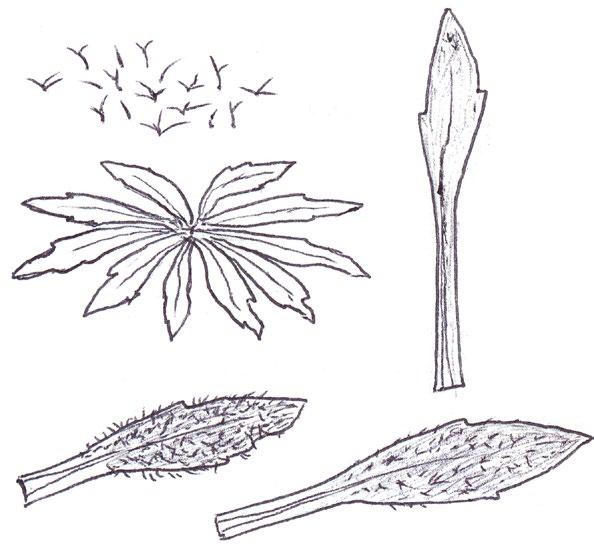

Tiny rosettes of the annual crucifers Erophila verna agg. (Common Whitlowgrass and related species), Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale Cress), Capsella bursapastoris (Shepherd’s-purse) and Sisymbrium officinale (Hedge Mustard) present frequent problems from early winter though until spring. The basal leaves of Erigeron canadensis (Canadian Fleabane) can also be tiny and one genotype can look surprisingly like Arabidopsis thaliana at this stage; one also has to look out for the succulent, more or less spathulate leaves of Saxifraga tridactylites (Rue-leaved Saxifrage), Montia fontana (Blinks) and Claytonia perfoliata (Springbeauty) in ruderal or pavement situations. All these plants are actually quite easily distinguished using the leaf shape, colour and indumentum characters illustrated here.

There seems to be be two very different common genotypes of Erigeron canadensis in our area, the typical one with very attenuated petioles and 1–2 (3) forwardly pointing triangular lobes near the leaf tip; and one, more resembling Arabidopsis, where the leaf is broadly ovate with a very short petiole and one tiny

MELILOTUS spp.

c. 2/3

Fine awl-shaped stipules without clasping base

Serrations on upper two thirds of leaflet

blunt lobe near the tip. Despite the very different leaf shape, both entities have the same regularly spaced out ciliate hairs on the petiole and typical forwardly curved hairs on the leaf edge further up. Basal leaf rosettes of Erigeron sumatrensis (Guernsey Fleabane) are usually much larger (5–10 cm across) and the leaves have 3–5 crenate-serrate lobes; the ciliate hairs on the petiole are sparser and interspersed with many shorter kinked hairs between. The basal leaves of E. floribundus (Bilbao Fleabane) are usually very much larger (10–15 (20) cm), shiny dark green and with numerous, very long, parallel-sided lobes.

Erophila verna agg. can only be reliably separated into the three species treatment used by Rich (1991) and Stace (2019) when in flower, so 8-figure grid references should be taken so that presumptive identifications of E. glabrescens (Glabrous Whitlowgrass) and E. majuscula (Hairy Whitlowgrass) can be checked later in the spring.

The Norfolk Flora Group has recently been finding populations of E. glabrescens, having noticed that the leaves of this species are noticeably pale yellowish-green and have very long petioles, about

EROPHILA VERNA GROUP

E. glabrescens

Pale yellowgreen

Petiole : blade ratio

c. ½ c. ¾

E. verna s.s. c. 2×

ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA

Typical Occasional

Dark shiny green

Basal leaves with truncate terminal lobe

Lobes with toothed lower edge

SISYMBRIUM OFFICINALE

More common problems in identification

CAPSELLA BURSA-PASTORIS

Very variable leaf dissection

Pale dull green

Lobes with smooth rounded lower edge

ERIGERON CANADENSIS & SUMATRENSIS

Broad leaved genotype

E. canadensis

Typical form

E. sumatrensis

Leaves simple at first, soon becoming trifid

SAXIFRAGA TRIDACTYLITES

All succulent, glabrous

No proper rosette Trailing decumbent habit Pale yellow green

MONTIA FONTANA

1(3) lobes

Early leaves narrowly spathulate

Later leaves simple rhombic Pale yellow green

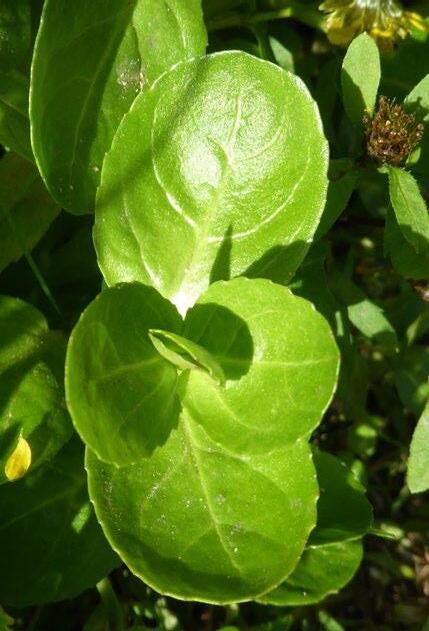

CLAYTONIA PERFOLIATA

E. majuscula

twice as long as the blade; the leaves are usually completely glabrous except for the leaf edge but there are often just one or two hairs on the lamina upper surface near the leaf tip. In E. verna s.s. the petiole is about three-quarters the length of the blade and the leaves are mid green, with moderate hairiness; E. majuscula has very densely hairy leaves, a similar mid green colour and the petiole is less than or equal to half the length of the blade.

Arabidopsis thaliana basal leaves, like those of Erophila , have a mixture of simple, forked and 3-rayed stellate hairs and are dark green and pretty much constant in shape – usually broadly ovate to elliptic with 2–3 obscure teeth around half way up and a very short petiole; in Norfolk we rarely see narrowly ovate to elliptic basal leaves with long petioles as in the Rich (1991) illustration.

The basal leaves of Capsella bursa-pastoris are extraordinarily variable in any one population or even in one plant! Usually, however, at least some will have pinnatisect or partially pinnatisect leaves with characteristic forwardly curved lobes showing an entire lower edge. Simple leaves found on their own cause the most difficulty, but with experience can usually be identified by their numerous tiny teeth, shape, pale green colour and combination of simple and (3)5 rayed stellate hairs.

The basal leaves of Sisymbrium officinale are very constant and readily identifiable by their dark, shiny green toothed pinnate lobes and characteristic truncate terminal lobe (not found on the otherwise very similar stem leaves later on).

Saxifraga tridactylites, Montia fontana and Claytonia perfoliata have basal leaves that are all slightly succulent, glabrous and more or less spathulate. The saxifrage usually grows on walls, in road and mud collected at wall bases, or in our region, in the depressions between the flint cobbles of decorative paving. Its rosettes are very tiny, around 1 cm across, and the leaves are characteristically held in a high arched posture. Early on this may be all there is to go on, but later a few ‘give-away’ shallowly trifid leaves will be produced; eventually deeply trifid leaves will begin to show in the centre of the rosette. Montia fontana can be an aquatic but nearly all our plants

grow either in damp hollows in amenity grassland or on road kerbs or in gutters. Blinks has a trailing habitat and does not produce a leaf rosette; the leaves are spathulate to obovate throughout. Claytonia perfoliata can be spotted by its striking pale yellowgreen colour; the first leaves are very narrowly spathulate and long petioled, and it can be many weeks before the broadly rhombic leaves appear.

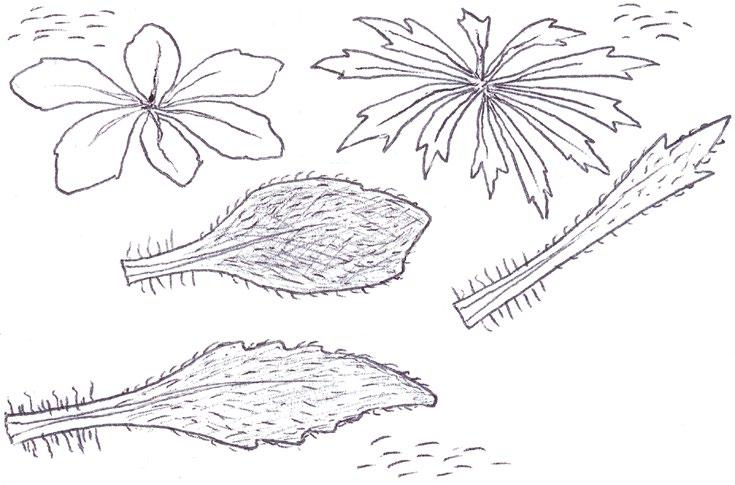

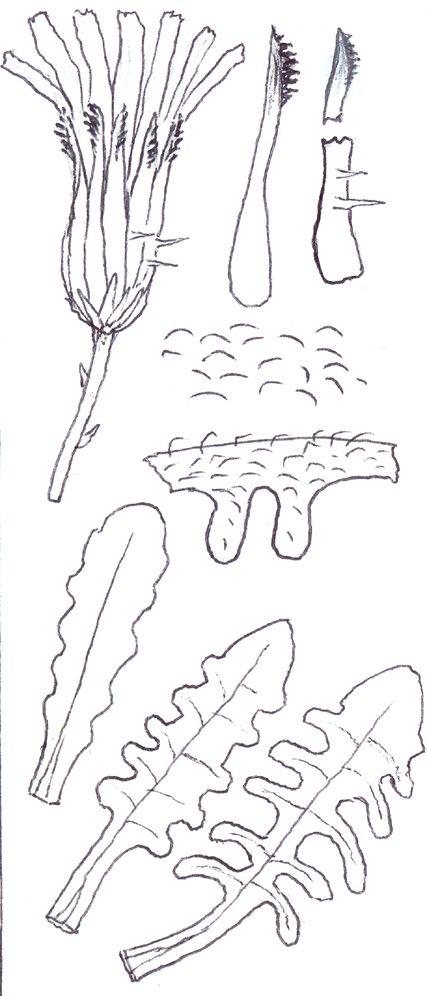

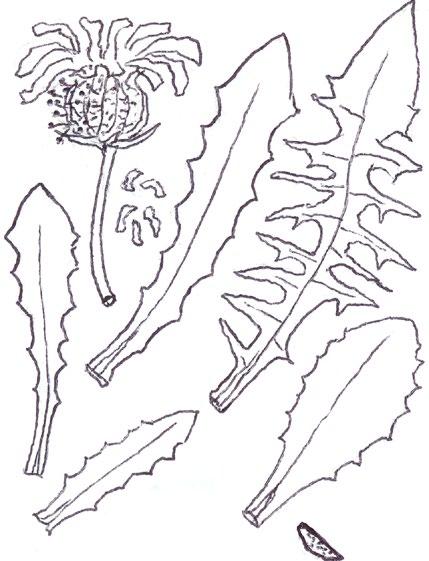

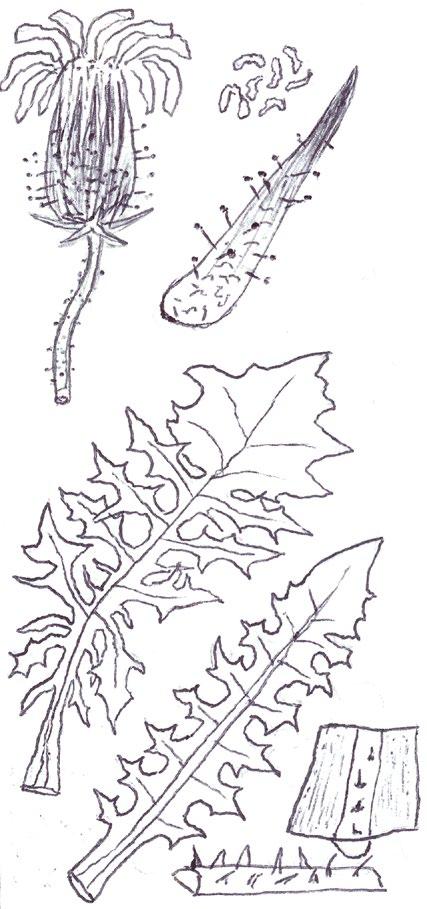

Overwintering and spring basal leaves of common yellow composites

Since embarking on winter recording the basal leaves of Hypochaeris radicata (Cat’s-ear), Scorzoneroides autumnalis (Autumn Hawkbit), Crepis capillaris (Smooth Hawk’s-beard), C. vesicaria (Beaked Hawk’s-beard), Leontodon saxatilis (Lesser Hawkbit) and less often L. hispidus (Rough Hawkbit) have been causing the group problems in almost every recording session. The basal leaves of these species are extraordinarily variable and frequently produce ‘lookalikes’ mimicking other species in the group – a few of these variations are illustrated in the BSBI Plant Crib (Rich & Jermy, 1988) and Sell & Murrell vol. 4 (Sell & Murrell, 2006) and more are shown here. It is important to realise that the simple obovate leaves of Crepis capillaris can be very like immature or shade leaves of Taraxacum (dandelions) and may not be separable vegetatively; also that the tiny winter leaves of this species can also closely resemble Hypochaeris glabra (Smooth Cat’s-ear).

Vegetative separation of these taxa on basal leaves is not always possible, but usually a reliable identification can be arrived at using:

• the shape of the leaf lobes (rounded, long and parallel-sided, triangular);

• the width of the terminal leaf segment compared with the width of the undissected leaf below;

• texture (thin and membranous, thick and leathery) and indumentum.

It is not only Leontodon hawkbits that have characteristic hairs; the hairs of the other species are not illustrated in the literature and difficult to describe, so hopefully the drawings here will be helpful.

LEONTODON SAXATILIS

HYPOCHAERIS RADICATA

LEONTODON HISPIDUS SCORZONEROIDES AUTUMNALIS

CREPIS CAPILLARIS

CREPIS VESICARIA

TARAXACUM

HYPOCHAERIS GLABRA

Leontodon saxatilis

Sparse forked hairs; fairly thin textured leaves; typically with sinuate leaf edge but on occasions can have very long triangular lobes which may be hooked forward or backward; leaf edge flat (not undulate). Leaf rosettes in favoured lawn type grass short leaved and fairly appressed to the ground, but in longer grass the leaves can be very long and ascending.

Leontodon hispidus

Dense forked hairs; thick leaf texture; leaf edge always sinuate to shallowly sinuate dentate; leaf edge usually undulate.

Scorzoneroides autumnalis

Usually has sparse once or twice kinked hairs (only occasionally glabrous); fairly thick textured leaves; leaf lobes usually long and parallel sided with obtuse (not broadly rounded) tips; very long lobed forms can have hardly any leaf lamina and long narrow ‘lobes on its lobes’; occasionally produces extraordinary long, linear, more or less entire leaves; terminal segment same width or narrower than width of the undissected part of the leaf below.

Hypochaeris radicata

Leaves seldom glabrous and nearly always with quite dense, arched hairs; thick textured; fairly wide terminal segment; leaf lobes usually short but can be very long and very occasionally have lobes on the lobes; leaf lobes always have broadly rounded tips.

Crepis capillaris

Usually glabrous, sometimes with a few weak bristles on undersurface midribs; very thin textured; winter leaves very small (only a few centimetres in length) and very constant with shallowly sinuate dentate edge; spring leaves are typically sinuate dentate, with terminal segment broader than the leaf below, but large leaved forms can have extremely long triangular lobes, with on occasions large triangular teeth on the lobes very like Crepis vesicaria (separation only possible if the latter has the diagnostic hairs described below).

Crepis vesicaria

The winter leaves are very long, dark green and strap shaped with fairly long, toothed triangular lobes, forming very characteristic dense, many leaved and appressed rosettes. The spring leaves have much longer lobes with long curved teeth, similar to those that Crepis capillaris can produce and already described. These types of leaves can only be ascribed to Crepis vesicaria if the diagnostic indumentum is present: either short, stout red bristles on the upper surface midribs (Poland & Clement, 2020) or longer, thinner hairs on the under surface midribs and lamina; all these hair types can be absent.

Glabrous leaves like this should not be identified, as they can be mimicked by both Crepis capillaris and Taraxacum , flowering plants of which can produce similar basal leaves to the spring leaves here illustrated.

Taraxacum

It is important to realise that immature late winter leaves or shade leaves of some Taraxacum microspecies can mimic the simple oblanceolate to obovate leaves of Crepis capillaris – both are usually glabrous or have just an occasional weak bristle on the undersurface midrib. Separation may be possible by looking for the hollow petiole of Taraxacum, but this can be difficult in small leaves; also note Crepis species can produce some white latex on squeezing the petiole, just like Taraxacum

Hypochaeris glabra

The very small basal leaves of this species very much resemble the tiny, single winter leaves of Crepis capillaris. They are always very small and glabrous except for the presence of fine ciliate hairs on the leaf edge, which are diagnostic. However, I’m not sure if ciliate leaf edge hairs are always present. Tiny glabrous leaves in spring or early summer on very poor soils should be gridded for confirmation when in flower if the record is thought to be a significant one.

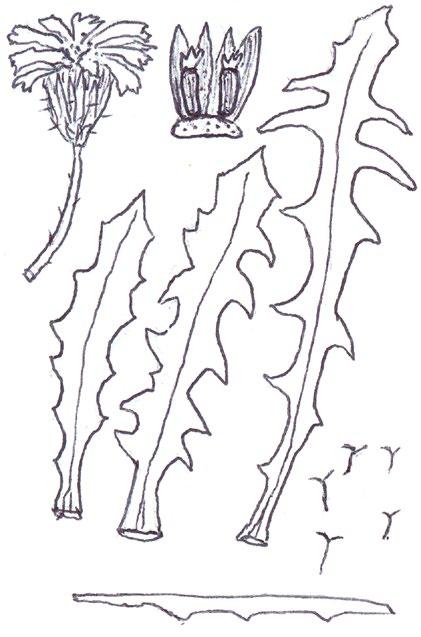

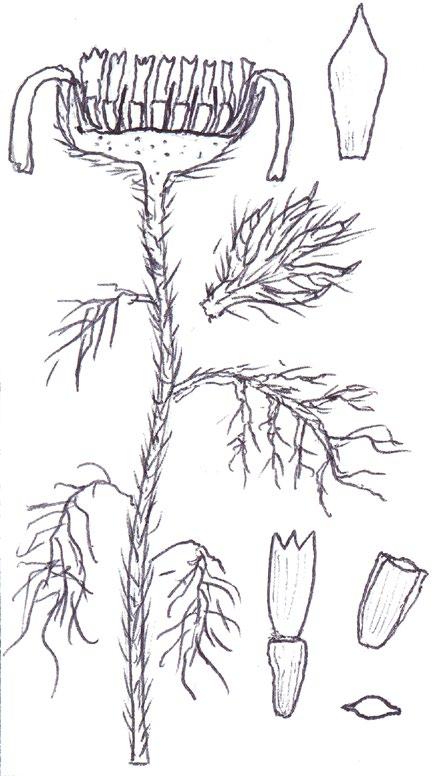

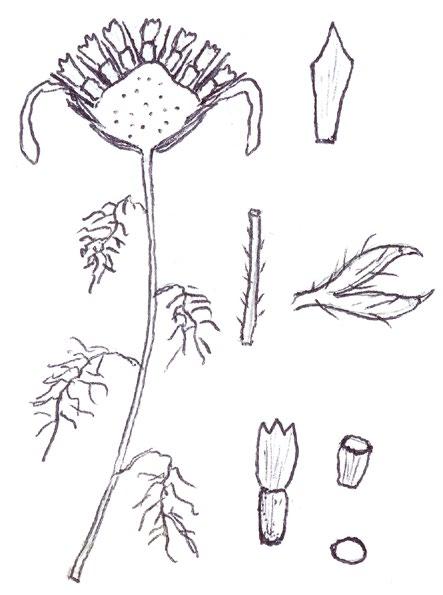

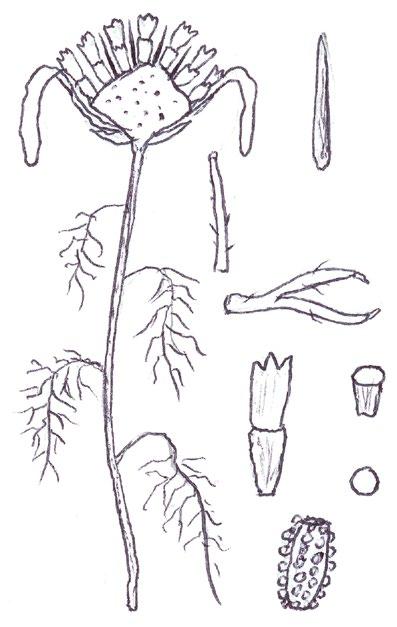

Identification of Anthemis and Cota

In Norfolk Anthemis cotula (Stinking Chamomile) is usually found on the heavy boulder clay south of Norwich and A. arvensis (Corn Chamomile) on the light sandy or chalky soils of the west. Over the last decade or so, however, we have been finding A. arvensis outside its native range and away from its usual arable habitats, in villages or suburbs, often as part of an obvious seed mixture sowing of ‘wildflowers’. We have also become gradually aware that Cota austriaca (Austrian Chamomile) is now to be found more commonly in such situations, largely since we realised that, compared with the Anthemis species, this plant is much more robust and thick stemmed, extremely hairy and much more strongly aromatic. Contrary to the usual descriptions, the two Anthemis spp. are both mildly scented and A. cotula does not smell particularly unpleasant; furthermore, the standard characters used to separate the two, hairiness and the shape of the terminal leaf segments, are far from clear cut and do not correlate with the shape of the receptacle scales.

More common problems in identification

In separating the species of these two general from each other, and from the mayweeds Tripleurospermum inodorum (Scentless Mayweed) and Matricaria chamomilla (Scented Mayweed), one has to become adept at thumbnail dissection of the flowerhead, so as to obtain a more or less central, vertical transection of the capitulum. T. inodorum is usually spotted because of its long, fresh green and finely divided leaves and long ligules; in M. chamomilla the leaves are not so long and the short ligules are nearly always strikingly reflexed. Confirmation is by finding a solid receptacle in T. inodorum and a vertically elliptical cavity in the receptacle of M. chamomilla. No receptacle scales should be found – these are characteristic of both Anthemis and Cota. The best way to find receptacle scales in the field and assess their shape is not to look for them in a thumbnail vertical transection, where they are very easy to miss between the disc florets, but to pinch off all the disc florets and rub them between finger and thumb into the palm of the hand for lens examination. On the other hand,

COTULA

COTA AUSTRIACA

COTA TINCTORIA (differences): greyish white colour, yellow ligules

ANTHEMIS ARVENSIS ANTHEMIS

their position on the capitulum and the shape of the capitulum are best looked for on a transection at home with a microscope.

I have taken home numerous Anthemis and Cota specimens for microscopy of a vertical transection and reached a different identification to that suspected in the field on many occasions: either because I have been able to find the linear receptacle scales of A. cotula confined to the central/upper part of the capitulum, or because the vertical transection revealed the more or less flat capitulum of Cota austriaca – in both Anthemis species the capitulum is strikingly conical.

Anthemis tinctoria (Yellow Chamomile), which used to be a fairly frequent find in urban habitats, has recently almost disappeared from the county, so I have not been able to confirm if this taxon also has a flat or near flat capitulum. It is certainly a very robust and very strongly scented plant like Cota austriaca, but with whiter leaves and of course, yellow ligules. Both Cota species have compressed

Seeing red (or is it blue?)

SIMON HARRAP

WhenI first started to photograph plants seriously in the 1990s I used slide film. Fairly quickly I came across a very significant limitation: plants with unquestionably blue flowers, if photographed in sunlight, would reproduce as reddish-purple on the slide. The very same plant, in the same place, if photographed under overcast conditions or in shadow, would reproduce as a more or less true-to-life blue. Hyacinthoides non-scripta (Bluebell) is one of the classic examples; if you search out published photographs of Bluebells in older books or even old postcards you will find examples of ‘pinkbells’. One of the most extreme cases of this blue-to-red transformation was Pinguicula grandiflora (Large-flowered Butterwort) which I photographed

and more or less keeled (not cylindrical) achenes, and this character can already be seen in the translucent, pale green, immature achenes found at anthesis, when these plants are usually spotted. It should be noted, however, that the tuberculate ribs on the achenes of A. cotula are not present at this stage.

References

Poland, J. & Clement, E.J. 2020. The Vegetative Key to the British Flora (2nd edn). John Poland, Southampton.

Rich, T.C.G. 1991. Crucifers of Great Britain and Ireland. BSBI Handbook No. 6. Botanical Society of the British Isles, London.

Rich, T.C.G. & Jermy, C. 1998. Plant Crib 1988. Botanical Society of the British Isles, London.

Sell, P.D. & Murrell, G. 2006. Flora of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 4: Campanulaceae–Asteraceae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Stace, C.A. 2019. New Flora of the British Isles (4th edn). C & M Floristics, Middlewood Green, Suffolk.

Bob Leaney

122 Norwich Road, Wroxham, NR12 8SA

in the Burren: in sunshine pink, in shadow blue (Figure 1).

I have no idea what the basis in physics is for the effect – perhaps in sunlight the plant reflects a lot of infrared which we cannot see but which is picked up by the emulsion on the slide film and then transposed into the visible red? Whatever the cause, it seemed strange to me that the authors, photographers and publishers of books featuring ‘pinkbells’ did not pick up on the error.

Authors (myself included) often work from photographs and/or herbarium specimens. Herbarium specimens seldom retain the true colours of the living plant, but this is usually obvious and therefore errors are mostly easily avoided. If the

colours on a photograph are misleading, however, one can see how errors can creep into the written word. It can be easier to visualise a photograph with false colours than it is to remember the real thing last seen months, years or even decades earlier. It is not just in the process of capturing an image that errors can appear; reproduction is fraught with problems. When we were working on Orchids of Britain & Ireland: A Field and Site Guide (Harrap & Harrap, 2006) we came across a whole range of frustrating issues. Most of the photographs reproduced in the book were taken on slide film, and for reproduction these were professionally scanned to produce a digital image. Try as we might, however, we could not get the colours right – rich pinks and magentas as in the genera Gymnadenia, Dactylorhiza, Orchis and Anacamptis were dulled. If you are lucky enough to have a copy of the book, take a look at the photos, or better still take it out into the field and compare it with the real thing. It was (and is) heartbreaking. It was not our fault, however, or the fault of the publishers or printers.

and

Seeing red (or is it blue?)

It is just a fact of life. Offset lithography (sometimes just ‘offset’ or ‘litho’), the technique still used for most commercial printing, almost always uses just four inks: cyan, magenta, yellow and black (CMYK for short). These four inks are combined to produce a vast range of colours, but there are some colours that they cannot produce – these colours are ‘out of gamut’. Unfortunately for us, our orchids’ magentas and pinks were well out of gamut and could not be printed by standard 4-colour litho, hence the muddy results. It is possible to expand the gamut of colours that can be reproduced, but that involves adding extra inks (see below) and is expensive – it is usually reserved for high-end fine art books, etc.

Digital imaging has transformed photography. A digital camera’s sensor collects data for three colour ‘channels’, red, green and blue (RGB for short) and these three colours are later mixed by computer to produce millions of colours. Digital images work especially well when viewed on screen, because screens use the same three colours (RGB) to recreate the image. All good so far, but RGB processes also

The slides were photographed on a light box and the raw digital images processed identically. On the slide taken in sunshine the flowers are reddish-purple; taken in the shade the same flowers are blue. But, in order to be reproduced here in print the digital images have to be converted from RGB to CMYK, which changes the colours again (they are duller and more muted).

Figure 1. Pinguicula grandiflora (Large-flowered Butterwort), Holywell, Cappanawalla, The Burren, Co Clare, 22 May 2004. Photographs taken in shade

in sunshine on Fujichrome slide film (probably Fuji Sensia).

have colours that are ‘out of gamut’, and these are not the same as the CMYK ‘out of gamut’ colours! Helpfully, however, they seem to impact less on the reproduction of images of plants. The net result is that digital photos viewed on screen tend to be more accurate than the printed versions (try comparing photos on a tablet or phone with the same species in a book, and with the real thing out in the open air).

There are still issues with digital photographs, however. For commercial printing, the photograph that came off the camera as an RGB file has to be converted into CMYK, because the printing press still uses those four inks and still has the same limited gamut of colours that can be reproduced. I think that bright blue, violet and magenta flowers are the worst offenders: they simply cannot be printed accurately.

One recent case is the BSBI’s very own Violas of Britain and Ireland (Porter & Foley, 2017). Violets are, by their nature, prone to problems in reproduction: take a look at the photographs of Viola riviniana and V. reichenbachiana: the colours bear little relation to reality, but I cannot be smug, as the colours as printed of Common and Early Dog-violets in Harrap’s Wild Flowers are not much better!

What to do? It is possible to print more accurately, and some desktop printers use eight or even more inks to produce an expanded gamut, but this is not yet the answer for a large run of affordable books or periodicals. Publishing online and viewing on screen can help a lot, as noted above, but online field guides and periodicals have other limitations, and my understanding is that ‘e-book’ versions of many field guides, etc. take the CMYK files used for the printed version and simply convert them back into RGB, this conversion producing another loss of fidelity. I think that the best thing at present is to be aware

of the issues and not to attach too much weight to the exact appearance of blue, violet and magenta flowers in your field guide or BSBI handbook. It would also be helpful for authors, especially of more technical reference works, to explicitly point out the shortcomings of a reproduced image (and in this I will try to take my own advice!).

Finally, the issues surrounding sun vs shade and RGB vs CMYK are not the only problems encountered in recording and reproducing colours. Bright, very saturated colours, such as red poppies or yellow daffodils, also pose a challenge, and it is all too easy to ‘blow’ a colour and end up with a solid block of red or yellow with no texture or detail. Another issue is the algorithms used by many cameras to construct an image from the raw data coming from the sensor (after all, just a string of numbers), especially when on ‘auto’. The software writers know that people like vibrant, bright images, and so the finished picture on you digital camera or smartphone tends to be pushed in that direction. In short, digital photography offers the opportunity to produce fantastic true-to-life images, but care has to be taken at every step if you are to really take advantage of that opportunity.

References

Harrap, A. & Harrap, S. 2006. Orchids of Britain & Ireland: A Field and Site Guide. Bloomsbury Publishing, London & New York.

Porter, M. & Foley, M. 2017. Violas of Britain and Ireland. BSBI Handbook No. 17. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Bristol.

Simon Harrap erigeron@norfolknature.co.uk

Trollius europaeus (Globeflower) in the West Pennine Moors and experience in propagation for re‑establishment

PETER JEPSON

In 2023 Natural England (Cheshire to England Team) commissioned me to undertake a study into previously known populations of Trollius europeaus (Globeflower) in and peripheral to the West Pennine Moors SSSI, in South Lancashire (v.c. 59). It was known that certain local sites had been lost in the last few decades but there was no up to date knowledge of all the sites. T. europaeus is considered of ‘least concern’ in Stroh (2014); whilst in Stroh (2023), it is considered relatively widespread in its core northern and western areas, but has clearly declined at the fringes of its range, a process which began before 1930 and still continues. A data search revealed sixteen sites in the wider area with nine sites within the SSSI boundary, six of which were known to me in the mid-1970s, with the seventh site for the last twenty five years.

Survey of previously known sites

Of the nine sites, T. europaeus only remained extant at two. The reason for the losses was attributed

Trollius europaeus (Globeflower) colony at Belmont, West Pennine Moors SSSI (v.c. 59), May 2023. Peter Jepson (photographs by the author)

to land management changes, either through the loss of seasonal grazing, increased tree cover or a combination of both. Most of the extinct populations were on valley side locations previously carrying open woodland, which were aftermath grazed in late summer in combination with their adjacent meadows following traditional haymaking. In this respect they constituted a form of wood pasture in a management regime that would comfortably fit with notions of ‘re-wilding’.

In terms of the two extant sites, one (Gale Clough) was small with only 34 blooms; its survival may be attributed to the fortuitous scrub clearance below overhead cables. The other (Belmont) was a large population growing on a field bank with over 1550 blooms in 2023 (photo above), a decrease of 48% from a count in 2000. This site had been receiving

Trollius

intermittent management for two decades, largely dependent on sheep sporadically wandering through a seasonally open gate and grazing the vegetation. At least some decline was associated with competition from Filipendula ulmaria (Meadowsweet) and the sward slowly becoming taller. The population had dipped before some cutting of the F. ulmaria after the T. europaeus has seeded resulted in a partial recovery of the latter.

Seed propagation for recovery

A part of the Natural England contract was to collect seed from populations and propagate at least 200 plants for a local recovery project. In order to ensure genetic diversity it was recognised that a proportion of seed should ideally be collected from outside the West Pennine Moors. The intention was from a site in the Forest of Bowland; however, most of the fruiting heads were missing, presumed due to slug predation, hence limiting the amount of seed available to harvest. Therefore, seed was collected from an additional site in the Yorkshire Dales.

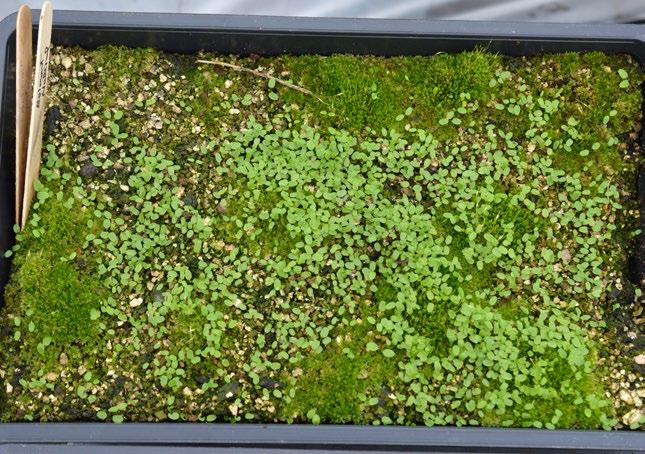

Ripe fruiting capitula were collected during July 2023 and the seed allowed to fall (Figure 1). From each site 2.5 ml of the seed was sown separately in seed trays within days of collection (natural sowing). There appears to be a consensus on the internet that chilling the seed of T. europaeus promotes germination. The Seedaholic website recommends, if seeds fail to germinate after 6 weeks, to chill the seed tray in a refrigerator at 4°C for 8 weeks. The notion of placing such a tray in our domestic refrigerator did not gain favour; instead 2.5 ml of seed from two of the sites were each mixed with moist sand and stored in small containers in a refrigerator for 8 weeks at c.4°C before sowing (stratified sowing). The remaining collected seed was amalgamated and stored in cool dry conditions over the winter, one batch being sown in mid-February 2024 (late winter sowing) and another in mid-March 2024 (early spring sowing).

The natural and stratified trays were kept in a polytunnel until the end of October and then put outside until the first few days in February, whereupon they were returned to the polytunnel.

The late-winter and early-spring 2024 sowings were kept outdoors for c.8 weeks before being brought into the polytunnel.

Two seedlings appeared from the natural sowing during the autumn but died off during late winter. By the end of February there was abundant germination in all trays (Figure 2), although the germination arising from the stratified sowing was marginally later. No seedlings appeared from either the late winter or early spring sowing in the following 12 months.

Overall the germination was good, resulting in many hundreds of seedlings. During 2024 a proportion was potted up for the local Globeflower recovery project. As a pilot a few of these were planted out in a local species-rich meadow in early spring 2025, however, these suffered in the drought that followed. Most of the potted up seedlings that germinated in 2023 flowered well in 2025.

A contribution to the recovery project was made in spring 2023 by the daughter of two of my deceased friends, by way of the donation of a large T. europeaus plant from her parent’s garden. The plant (Roy’s Plant) was of known provenance having been grown from seed collected locally several decades previously. At the time the plant was already in leaf and with numerous flower buds. The plant was split into a good number of individual crowns with all

Figure 1. Seed of Trollius eurpaeus collected in July 2023.

above ground growth removed prior to being potted individually. These were grown on in a polytunnel and by September 2023 several of the plants were sufficiently established to give a late flowering.

Potential limitation to sustainable recovery

In January 2024 my attention was drawn to the BSBI species account for T. europaeus (Stroh, 2015) and the potential adverse implications in particular paragraphs for delivering sustainable species reestablishment. In citing Pellmyr (1989) and Hemborg & Després (1999) the account states that, Trollius europaeus is an obligate outcrosser and depends almost exclusively on a seed parasite, small anthomyiid (Chiastocheta) flies, for pollination. Also in considering threats, Lemke & Porembski (2013) are cited in terms of dependence on Chiastocheta flies and that a decline in the local population of this pollinator is likely to impact upon small and declining populations of T. europaeus leading to a limitation of pollen quantity and a higher likelihood of selfing or inbreeding. However, the latter statement of selfing is at odds with the earlier statement that Trollius europaeus is an obligate outcrosser.

In these respects it would be reasonable to assume that a Trollius europaeus recovery project would need to comprise not just the plants but it also Chiastocheta flies to be successful in the long term. Suchan et al. (2015) hypothesize that if this interaction between flower and fly is specific and obligate, then T. europaeus should experience dramatic drop in its relative

fitness in the absence of Chiastocheta. However, in their research this hypothesis was not proven, as T. europaeus populations without flies demonstrate a similar relative fitness to those with the flies present, contradicting the putative obligatory nature of this pollination system. They also observed that many other insects also visit and carry pollen among T. europaeus flowers. Indeed this later point agrees with my observations that other insects regularly visit the flowers of T. europaeus, even bumblebees.

Investigations in July 2024 by experienced entomologists studying Chiastocheta failed to detect any of these flies at the Belmont site. Similarly none were found at the Bowland site either, although they are known elsewhere in the vicinity. They have also been recorded in the nearby Yorkshire Dales.

The Belmont, Bowland and Yorkshire Dales populations each produced abundant well-formed seed, which germinated in quantity in the following spring (Figure 1).

Further, the quote in Stroh (2015) that T. europaeus is an obligate outcrosser needs further assessment. Growing in the polytunnel, several of Roy’s Plants came into bloom during September 2023, however, it was not realised until mid-winter that two fully formed seed heads on different plants had developed. On examination it was found that both had dehisced but only one still retained a few seeds. Nine seeds were extracted and examined and found to be well formed. These were sown in January 2024 and by mid-summer one seedling had appeared. As both of the plants involved had been split from a single large

Figure 2. Young seedlings of Trollius europeaus growing in a seed tray, March 2024.

Trollius europaeus (Globeflower) in the West Pennine Moors and experience in propagation

clump, they must be genetically identical. Whether they were pollinated by insects or self-pollinated is immaterial as it amounts to the same. However, given their isolation and the time of the year it is reasonable to assume that no Chiastocheta flies were involved.

Stroh (2015) cites (Hitchmough, 2003) over the vulnerability of seedlings to slug predation in unmown and tall swards. This has synergy with the 2023 survey at the Bowland population where the vegetation was tall, rank and appearing to be neither mown nor grazed for many years; here almost all fruiting heads were missing. It was surmised that slugs had predated the fruiting heads. Similar decapitated stems were observed in the Yorkshire Dales but to a lesser degree. Indeed, in cultivation I have observed slugs ascending T. europaeus plants in late evening and there being many flower buds missing the following morning. I have encountered a similar problem with dense thatch swards and the decimation of plants of Alchemilla acutiloba (Starry Lady’s-mantle) leading to their loss.

Conclusions

My study strongly suggests the following:

• Populations of T. europaeus have declined in and around the West Pennine Moors and have also done so elsewhere in Lancashire over the last 50 years. This correlates with Stroh (2023). However, the reality may be more profound in that individual populations may be declining within core areas but still extant, so creating a record indicating presence in distribution mapping.

• Further studies are suggested to determine whether the Least Concern status needs adjusting to Near Threatened or Vulnerable.

• Seed should be sown soon after ripening and subjected to winter conditions to facilitate spring germination;

• No advantage was found in chilling the seed for 8 weeks before sowing; indeed such seedlings appeared a week or so later than those sown soon after ripening;

• No germination occurred with seeds stored in dry cool conditions and sown in late winter or early spring; and

• Re-establishment sites need to be appropriately managed such that the sward is not thatchy in order to limit the population of slugs and snails.

• Traditional hay field management involving cut and remove or comparable techniques should be viewed as a form of re-wilding; the walk away re-wilding approach allowing grazing stock to graze as they will, may allow too great a vegetation thatch to develop, to the detriment of T. europaeus

References

Hemborg A, & Despres, L. 1999. Oviposition by mutualistic seed parasitic pollinators and its effects on annual fitness of single and multi-flowered host plants. Oecologia 120: 427–436.

Pellmyr, O. 1989. The cost of mutualism between Trollius europaeus and its pollinating parasites. Oecologia 78: 53–59. Stroh, P.A., et al. (12 authors) 2014. A Vascular Plant Red List for England. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Bristol. Stroh, P.A. 2015. Trollius europaeus L. Globeflower. Species Account. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland website: bsbi.org/species-accounts. Suchan, T., Beauverd, M., Trim, M. & Alvarez, N. 2015. Asymmetrical nature of the Trollius–Chiastocheta interaction: insights into the evolution of nursery pollination systems. Ecology and Evolution. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Seedaholic: seedaholic.com/trollius-europaeus-globeflower.html [accessed 11 July 2023].

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank S. J. Martin for is first-hand knowledge of the Belmont Trollis europaeus (Globeflower) population and to Lancashire Environmental Records Network for the supply of historical records for Lancashire. Thanks are due to Ben Hargreaves for arranging funding for a polytunnel through the National Highways ‘Network for Nature’ programme. Additional thanks in consideration of Chiastocheta flies go Philip Brighton and Rob Zloch. A final thank you goes to Karen Rogers for her helpful administrations.

Peter Jepson

pjepsonecology@btinternet.com

Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien (Miles) 1817–1891 – The Lady of the Flowers

Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien (Miles) 1817–1891

The Lady of the Flowers

DAVID C. RAYMENT

Inthe Appendix to her paper, ‘Charlotte Grace O’Brien (1845–1909), her botanical interests and achievements’, which appeared in British and Irish Botany (7(1): 10–29, 2025), Sylvia Reynolds draws attention to the confusion surrounding the authorship of Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight (1881), by Charlotte O’Brien and Mr C. Parkinson (a Fellow of the Geological Society of London). As Reynolds states, Charlotte Grace O’Brien is often incorrectly cited as the co-author, instead of another Charlotte O’Brien of whom little is known. It is thought Miss Charlotte Grace O’Brien had never visited the Isle of Wight; but another Charlotte O’Brien, Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien, the true co-author of Wild Flowers, had resided there for nearly thirty years. Before then Mrs O’Brien had lived in Brighton, Sussex, and several times she exhibited cut flowers and wild flowers at the Brighton Show. This article introduces Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien to the reader and offers an insight into her life, character and botanical interests.

Birth and marriage

Mrs Charlotte O’Brien was born Patty Charlotte Miles at London on 3 December 1817 and was baptised there at the parish church of St Andrew, Holborn, on December 30. She was the daughter of John Miles, then a furniture seller, and his wife, also named Charlotte (www.ancestry.co.uk). The twentyeight year old Patty, however, was living on the east Kent coast at Broadstairs, Isle of Thanet, at the time of her marriage to the Irishman, Patrick O’Brien, at the parish church of St Peter. Patrick was then of Dunoon, Argyle, Scotland. The marriage was reported in the Sun (London, 29 April 1846) and is listed in the June Quarter of the Civil Registration Marriage Index (1846). The marriage was also reported in the Glasgow Herald (27 April 1846)

where Patty’s father is incorrectly named William. Thereafter, she appears only to have been known as Charlotte (except on legal documentation), perhaps because of the similarity of her first name with that of Pat, an abbreviation of Patrick.

The Brighton Show and Little Arthur’s Book of Biography

By 1856, however, Charlotte and Patrick were living at 17 Buckingham Place Road, Brighton. In that year she entered the third running of the Brighton and Sussex Floriculture and Horticultural Show, winning the first prize of £2 under the Cut Flowers category heading of ‘Device’. Under the same heading she achieved further success by winning first prize (£1) for her exhibit of wild flowers, for which she was the only entrant (Brighton Gazette, 12 June 1856). Two years later she won 50 shillings for coming second for cut flowers; and for wild flowers she won 10 shillings for coming third (Brighton Gazette, 16 September 1858). The O’Briens later moved a short distance away to number 20, which is where, in March 1859, Charlotte wrote a preface to her Little Arthur’s Book of Biography. The short preface is shown here in full:

‘The names of the good and great of all ages ought to be as familiar as “Household Words” to every child of nine or ten years of age. The fact that they are not so, has induced the writer to publish this very simple Biographical Text Book, which she trusts will prove as useful to children in general, as it has long been to her own little pupils’.

The book proper is in four columns – name in alphabetical order with a very brief description of the individual, place of birth, date of birth and year of death. The list of names begins with Sir Ralph Abercrombie. Other names include: Archimedes, Sir Richard Arkwright, John Audubon, Beethoven, Tycho Brahe, Chaucer, Edmund Halley, Lord Nelson, Sir Isaac Newton, Linnaeus and William

Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien (Miles) 1817–1891 –

Wilberforce, to name only a few. Last on the list is ‘Zwingle, or Zwinglius, the great Swiss reformer and patriot’.

Charlotte continued to exhibit at Brighton and, in 1860, in the third tent on the Lawn at the Pavilion, her contribution was: ‘a harp with flowers most artistically’. She also exhibited ‘a pretty collection of wild flowers, forty varieties in pots, to which a third prize is awarded’ (Brighton Gazette, 13 September 1860).

The O’Briens were still living at 20 Buckingham Place Road at the time of the 1861 census where Patrick is recorded as a teacher who obtained his BA degree at T.C.D. (Trinity College Dublin). Charlotte was a governess. They had six female pupils living with them aged between 11 to 18. For the same year Charlotte’s name is listed in Mair’s Schools List (1861) in the section headed ‘Ladies Private Schools’.

The O’Briens leave Brighton for the Isle of Wight

Charlotte and Patrick, however, left Brighton in 1862 when they moved to Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, which is where they established Roseville School in Grove Road. Even so, Charlotte continued to exhibit at Brighton and in 1864 her wild flowers achieved second prize (Sussex Advertiser, 2 July 1864).

On the 1871 census there were four scholars living at the school; all were boys, so Roseville was not a young ladies’ school as at Brighton. Patrick, who was listed on the 1871 census as ‘Private Tutor’, was a well-respected member of the Ventnor Local Board. He died later the same year at the age of 54. Patrick had Erysipelas, a bacterial infection which began in the face (Hampshire Telegraph, 13 December 1871). It must have been a difficult time for Charlotte. He was buried at the then new cemetery (Founded 1870) at Ventnor which is now managed by the Isle of Wight Council. A committee was soon formed to raise monies for a memorial. A monumental cross made of Wicklow granite was erected over the grave in November 1872 (Hampshire Advertiser, 16 November 1872).

Now a widow, Charlotte continued with Roseville School which undoubtedly took up much of her

time, but her interest in plants did not abandon her. During Christmas 1880, Charlotte wrote about her garden in correspondence to the local press: ‘In my garden I have in full bloom four different kinds of roses, veronicas of every shade, double stocks, French Marguerites, cyclamen, scarlet geranium, primroses, and violets in profusion. Surely we may go further and perchance fare worse …’ (Isle of Wight Observer, 1 January 1881). The piece was published outside her locality and even reached America when quoted in The Free Religious Index (1881), a paper published at 3 Tremont Place, Boston by the Free Religious Association every Thursday at a subscription cost of three dollars per year.

The writing of Wild Flowers and a visit to America Wood

The year 1880 was the same year in which she wrote the preface to Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, in collaboration with Mr C. Parkinson, FGS. The book was published the following year. The purpose of the book was ‘to enable temporary residents in the Undercliff to become acquainted with the wealth of wild flowers in the immediate neighbourhood, by pointing out the localities in which the different species may be found, and the time of year when they are in bloom. For the latter purpose a concise Floral Calendar is supplied, giving the names of all the rarer kinds of wild plants which may be successfully sought for in the different months’. The calendar runs from January to August: ‘With the month of August, the reign of summer may be said to end, although in fine seasons many of the above-mentioned plants may still be found in September. Then comes the time of seeds and berries, carrying us through what would otherwise be a bare and desolate time. But there is no such period in nature’.

On August 7, 1884, a few weeks before the end of summer’s reign, Charlotte gave a large picnic at America Wood, near Shanklin. Some travelled independently but others went by train ‘which stopped for the occasion near the woods’. When the forty or so persons had finished their lunch ‘some roamed about the woods gathering flowers

and ferns’, while others danced ‘to the music of a violin’. The piece continues: ‘The white and bright-coloured dresses of the ladies looked most picturesque flitting about amongst the surrounding green. The rays of the departing sun were spreading a rosy glow over the glens, cornfields, and trees as the joyous party sat down to tea, and afterwards started home after a memorable and most enjoyable day’ (Lady’s Pictorial, 16 August 1884).

The passing of the Lady of the Flowers

In 1884 Charlotte too was in her August, about to enter her Autumn, passing away on 25 March 1891 at her Roseville residence as her husband had done nearly twenty years earlier. The 73-year-old was an ‘estimable lady, widely known and respected throughout the Undercliff, and her somewhat sodden demise will be mourned by a large circle of friends’ (Isle of Wight County Press, 13 June 1891). Her estate was administered by her brother, Harry Miles (National Probate Calander, 1891), and the property in which she lived was sold at the Commercial Hotel: ‘This property is beautifully placed with south aspect and sheltered from the east and north winds, commands charming views of the sea and landscape, and is within a few minutes’ walk from the railway station. There is a neat garden well

stocked with trees and shrubs. The lot is leasehold for a term of 999 years from 25 December 1863, at the annual rent of £10’ (Isle of Wight County Press, 1891). The leasehold was sold to a Mr T. A. Worrell for £1,080.

It is unfortunate that Patty Charlotte O’Brien has not been properly recognised for her work which was erroneously attributed to another. The co-author of Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, now rests peacefully at the same cemetery as her husband. No doubt some cut flowers are nearby, perhaps some wild ones too.

References

Mair, R.H. (ed), 1861. Mair’s Schools List. National Probate Calendar Index of Wills and Administrations for England and Wales, 1891. (Named as Patty Charlotte O’Brien.)

O’Brien, C. 1859. Little Arthur’s Book of Biography, H. & C. Treacher, Brighton; Hamilton, Adams & Co., London. O’Brien, C. & Parkinson, C. 1881.Wild Flowers of the Undercliff, Isle of Wight, L. Reeve & Co., London.

Reynolds, S.C.P., 2025. Charlotte Grace O’Brien (1845–1909), her botanical interests and achievements. Journal of British and Irish Botany 7(1): 10–29.

The Free Religious Index, 27 January 1881. Free Religious Association, 3 Tremont Place, Boston.

David C. Rayment

botany.rayment@btinternet.com

A postcard depicting Ventnor, Isle of Wight c.1890 where Charlotte O’Brien lived from 1862 until her death in 1891. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2002708264. Mrs Patty Charlotte O’Brien (Miles) 1817–1891 – The Lady of the Flowers

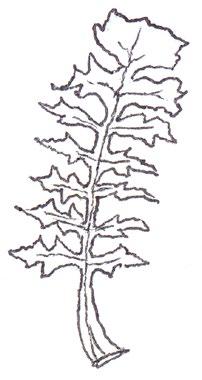

The extinct Glenridding Hawkweed Hieracium subintegrifolium discovered in two new sites at Ingleborough, Yorkshire

BRIAN BURROW

Glenridding

Hawkweed Hieracium subintegrifolium

Pugsley is a distinctive species in Hieracium section Tridentata characterised by its long, narrow, scarcely toothed (hence subintegrifolium), hairy leaves with conspicuous venation underneath and its broad, spreading panicle of large, dark flowering heads, and bracts with many microglands as well as numerous simple hairs and a few short glandular hairs (Pugsley, 1948; Sell & Murrell, 2006).

It was first discovered by H.W. Pugsley in limited quantity on grassy banks in Glenridding (v.c. 69) on 14 August 1927 (BM). It was last collected on a riverbank at Gillside on 18 August 1953 by J. E. Raven (E, 3 sheets; MNE, 1 sheet, grid reference NY378169). It has not been seen again despite much searching (Halliday, 1997; Sell & Murrell, 2006; Rich, 2013) so was classified as IUCN ‘Extinct’ (McCosh & Rich, 2018). Since 2013, I have also looked for it and Tim Rich has looked three times when camping at Gillside.

In August 2015, I found a few plants of a section Tridentata species in a side pothole at Pillar Pots, Ingleborough (SD734723). The plant had finished flowering and was difficult to access safely but I collected a few seeds from which I grew three plants and prepared herbarium specimens.

In July 2019, I found a few similar plants on Southerscales limestone pavement on Ingleborough (SD74077632, v.c. 64; Figure 1) which I provisionally identified it as H. subintegrifolium. In 2020, I collected a few seeds from which I grew a couple of plants and made some more herbarium specimens.

In March 2025, specimens from both sites were shown to T. Rich and compared with Raven’s 1953 Glenridding specimens, which, after allowing for cultivation, were found to be a good match for H. subintegrifolium. The cultivated plants were larger with more pronounced toothing on the leaves as might be expected compared to smaller plants with remotely denticulate leaves from Glenridding. This is a significant rediscovery of an extinct species in two new sites with an extension of range. Further surveys are planned for 2025.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mark Lynes for help with field work and use of his photographs and Tim Rich for confirming my identification.

References

Halliday, G. 1997. A Flora of Cumbria. Centre for North-west Regional Studies, University of Lancaster, Lancaster. Pugsley, H.W. 1948. A prodromus of the British Hieracia Journal of the Linnean Society of London (Botany) 54: 1–356. McCosh, D.J. & Rich, T.C.G. 2018. Atlas of British and Irish Hawkweeds (Pilosella Hill and Hieracium L.) (2nd edn).

Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Harpenden. Rich, T.C.G. 2013 Surveys of three endemic Lake District Hawkweeds: Hieracium filisquamum, H. fissuricola and H. subintegrifolium. Unpublished contract survey for Natural England, September 2013. National Museum of Wales. Sell, P.D. & Murrell, G. 2006. Flora of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 4: Campanulaceae–Asteraceae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Brian Burrow bburrow@hotmail.co.uk

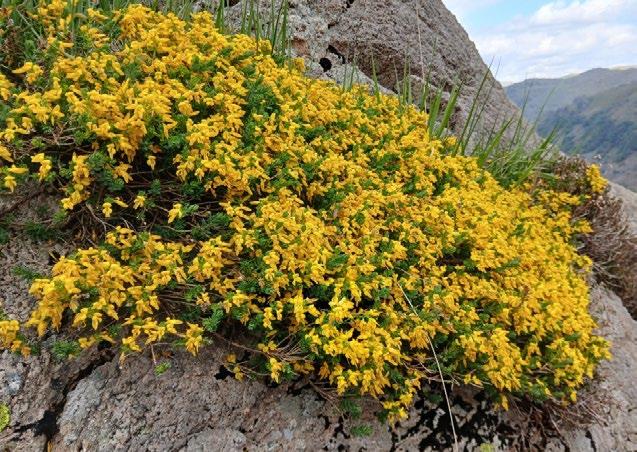

Figure 1. Hieracium subintegrifolium (Glenridding Hawkweed) on Southerscales, Ingleborough (v.c. 64) showing scarcely toothed leaves. Inset, capitulum. Mark Lynes

BEGINNER’S CORNER

Speedwells (Veronica) Part 3

This is the third and final part to our look at the commoner and more widespread speedwells (Veronica spp.) that occur in Britain and Ireland. Here we look at ways to identify the four speedwell species that are commonly found in wetland habitats. While some of the other species may occasionally be found in damp grassland or seasonally damp spots, these are the speedwells that are true denizens of wet places, typically occurring along the margins of rivers, streams, lakes and ponds and sometimes even standing in the water itself. As well as their love for wet places, these species all have another common trait – they have their flowers arranged in long spikes or racemes and it is details of these flower spikes, plus the appearance of the leaves, that will help with identification. When finding a speedwell in a wetland habitat, consider the shape of the leaves first, then move to the flowers: take a careful look at the flower colour, the size of the bract at the base of each flower and check whether the spikes of flowers

Veronica anagallis-aquatica (Blue Waterspeedwell) or its hybrid. Mike Crewe

arise opposite each other in the leaf axils or whether they alternate with each other, arising only from the base of one of a pair of opposite leaves. Note that the leaf toothing is very shallow in these species.

These four wetland speedwells are all rather widespread in Britain and Ireland, though three of the four become scarce or absent in upland areas and in the western and northernmost regions. As with so many of our wetland plants, they tend to do better where water quality is good and a small amount of range contraction has been noticeable in some species, especially in the more heavily populated areas of southern and central England.

As mentioned in Part 2, it is useful to remember that a common stalk that carries several flowers is a peduncle, while the individual stalks of each single flower are known as pedicels.

Mike Crewe mikedcrewe@gmail.com

MIKE CREWE

Brooklime (Veronica beccabunga). This is always a delightful species to find, with its glossy and rotund leaves and rich, royal blue flowers that may be found throughout the summer months. Brooklime is a relatively lowgrowing perennial that spreads to form mats on damp mud and along the margins of waterways, particularly favouring muddy deposits on the meanders of sinuous streams and rivers. It can be found throughout Britain and Ireland except in the highermost regions of Scotland and some of the Outer Hebrides. Amongst this group, Brooklime is easily identified by its rounded, glossy leaves and by the intense blue of its flowers. Flowers May–September. Photos: Mike Crewe

Marsh Speedwell (Veronica scutellata). Bucking the trend of the other wetland species covered here, Marsh Speedwell is local and generally uncommon in lowland England, becoming more frequent to the north and west, while it is the most widespread species in the upland regions of Scotland, Wales and northern England. In Ireland it is probably the most widespread species after Brooklime. Marsh Speedwell is a creeping perennial that can be identified by its relatively small and narrow leaves compared to others in the group (typically 2–4 cm in length) and by the flower spikes, which appear in only one axil of each pair of leaves, typically alternating up the stem. The leaves and stem often have a bronzy tint and the flowers are pale lilac-blue in colour, sometimes almost white. Flowers June–August. Photos: Mike Crewe (top left, top right); John Norton (bottom left).

Blue Water-speedwell (Veronica anagallis-aquatica) and Pink Water-speedwell (V. catenata). These two species are so similar that I have considered them both together; both are generally absent from higher regions of Britain but are otherwise widespread, with Blue being more common in much of Ireland and lowland parts of Scotland. These are both relatively large species, forming small stands of upright stems to 60 cm tall along the margins of a wide range of wetland habitats. They have rather elongate, stalkless, lanceolate leaves, though lower leaves of Blue Water-speedwell can have short petioles. Despite the names, the flower colour can often be difficult to determine, being various shades of bluish-pink or pinkish-blue, but the colour of ‘classic’ plants can be more helpful in identification. To tell the two species apart, it is best to look closely at the racemes of flowers, which appear in pairs opposite each other in the upper leaf axils. Each individual flower has a small leafy bract at its base which in Blue Water-speedwell is shorter than the pedicel of the flower that it is adjacent to. In Pink Water-speedwell this bract is almost as long as or longer than the adjacent pedicel. This feature should be checked when the flower is fully open, as the pedicels can lengthen later as the plant forms seed capsules, when this feature becomes less useful. In addition, the blue species has narrower and more attenuate, acutely pointed sepals, while the sepals of the pink species tend to be more ovate and abruptly (obtusely) pointed.

To complicate matters the hybrid between the two (Veronica × lackschewitzii) is common in some areas and often occurs in the absence of either parent. It usually grows more vigorously and taller than the two species and has longer racemes of flowers (usually >40 flowers). The capsules are often empty or poorly formed, so feel flat when squeezed with the fingers. There is a useful comparison table of characters of the two species and the hybrid in the Plant Crib account, available on the BSBI website (bsbi.org/plant-crib). Flowers June–August. Photos: top left and middle, Blue Water-speedwell (Mike Crewe); top right, Hybrid Water-speedwell (John Norton); bottom: Pink Water-speedwell (Mike Crewe).

ADVENTIVES & ALIENS

Adventives & Aliens News 36

Compiled by Matthew Berry

Flat 2, Lascelles Mansions, 8–10 Lascelles Terrace, Eastbourne, BN21 4BJ m.berry15100@btinternet.com

Anadditional record of Melica ciliata (Silky-spike Melick) was brought to my attention by Ken Balkow after the species featured in Adventives & Aliens News 35 (see v.c. 6). He found it on a green roof at Sharrow School, SK3485 (v.c. 63) in 2010, the plant’s identity having been confirmed by Bruno Ryves. It is published on p. 403 of The South Yorkshire Plant Atlas (ed. G. Wilmore et al., 2011), but was not in the DDb in early 2025.

I have included another of Andy Shaw’s epiphytic Tree-fern aliens in the present compilation (see v.c. 42), the justification for so doing as before. The plant was grown on and identified by him and at the time of writing there are at least three other species isolated in the same manner that await naming. It is inconceivable that this garden centre is the only one to which potentially or proven weedy alien plant species are hitching a ride in this way, or the only one from which they could be unwittingly disseminated by customers.

Claudia Pavia Kaplan, the finder of the v.c. 21 Cenchrus americanus (Pearl Millet) (see Adventives & Aliens News 35) provided two very helpful clarifications concerning her record. Firstly that the plant occurred in a postcode that meant it was more accurately located to Central Tottenham than to Tottenham Hale. Secondly and more importantly, that a more likely origin for the grass than bird seed was food or kitchen waste, the seeds being sold as ‘Bajra’ or ‘Whole Millet Seeds’ in many local Asian shops and markets.

Corrigendum: BSBI News 158, p. 31 (Adventives & Aliens News 34), in the fifth line of Zinnia elegans paragraph – ‘discoid capitula’ should be ‘radiate capitula’.

V.c. 1b (Scilly)

Cotula coronopifolia (Buttonweed). White Island (SV924175), 6/2024, D. Mawer (comm. R. Parslow): a number of flowering plants in a shallow seasonal pool on this uninhabited island off St. Martin’s, the sixth v.c. 1b record (the first having been made in 2002). It was growing with Suaeda maritima (Annual Sea-blite), a species only recorded once before in Scilly (Rosemary Parslow, pers. comm.) (see England roundup, p. 62). The site was revisited in 2025 by James Faulkenbridge when the plants were found to be flowering well in spite of efforts in 2024 to eliminate them. A glabrous, fleshy, procumbent to ascending annual or perennial (Asteraceae) to 30 cm, a native of S. Africa and New Zealand. It has alternate, aromatic, sheathing stem leaves that are basically broadly linear but ranging from entire to deeply lobed, even on the same plant, and solitary, yellow, hemispherical, discoid capitula (c.1 cm across) on long stalks. There are no receptacular scales and

Cotula coronopifolia, White Island, Scilly (v.c. 1b). James Faulkenbridge

the flattened, winged achenes lack a pappus. It is often associated with damp, saline places in some of which it is well naturalised. Adventives & Aliens News 19, v.c. 58. Stace (2019): 799.

V.c. 4 (N. Devon)

Helleborus × hybridus ‘Atrorubens’ (Lenten-rose Hybrid). Tawstock (SS560299), 27/3/2023, R.I. Kirby & S.H. Kirby: spread by seed from grave planting, with one single-flowered plant on a second grave and many first year seedlings in adjacent grassy areas, Tawstock Burial Ground. The first v.c. 4 record. A perennial herb (Ranunculaceae) with deeply lobed bracts, relatively few saucer-shaped flowers and leathery overwintering palmate leaves confined to the base of the stem. It differs from native H. viridis (Green Hellebore) in its larger flowers (5–7 cm across vs 3–5 cm), entirely free follicles (vs fused at base) that are shortly stalked (vs sessile) and its yellowish-green to purplish petaloid sepals (vs pale green). The hybrids are probably more commonly grown in gardens than is the pure H. orientalis (Lenten-rose) from Turkey. The Tawstock plants have been referred to ‘Atrorubens’, a clump-forming cultivar with reddish-purple to purple-pink, nodding or outward-facing flowers. Stace (2019): 112.

Jasminum beesianum (Red Jasmine). Fremington (SS51423250), 17/10/2024, R.I. Kirby & S.H. Kirby (conf. J. Poland): single clump in scrub beside a footpath. The first v.c. 4 record. An often scrambling deciduous garden shrub (Oleaceae) to 2 m, a native of China. The flowers are bright reddish-pink and usually six-lobed but are rather small and few in number in terminal leaf axils. They are followed by black, more or less globose berries (5–12 × 5–9 mm) that are presumably palatable to some birds. The simple leaves (more or less ovate-lanceolate and acuminate) distinguish it vegetatively from yellowflowered J. nudiflorum (Winter Jasmine), which has ternate leaves and white-flowered J. officinale (Summer Jasmine), which has pinnate leaves. J. humile (Yellow Jasmine) with yellow flowers and pinnate leaves, which differ from those of the preceding species in being alternate rather than (sub)opposite, is an occasional garden shrub from Asia that might

be better placed in another genus, Chrysojasminum Adventives & Aliens News 25, v.c. 50. Verbena rigida (Slender Vervain). Barnstaple (SS56663305), 12/9/2024, R.I. Kirby (conf. J.J. Day & M. Berry): single plant growing on a pavement edge where it abutted a grass verge, Firs Grove. The first v.c. 4 record. A tuberous-rooted perennial herb (Verbenaceae) to 60 cm from S. America, with sessile, stiff, hispid, serrate stem leaves and lilac or pale blue flowers arranged in terminal, elongating spikes, each individual corolla c.6 mm across. V. bonariensis (Argentine Vervain) is a taller plant with inflorescences that are more branched, leaves that are not as stiff or as leathery and bracts that are shorter than or equal to the calyx (vs longer than calyx). The fruiting spikes of V. bonariensis are shorter (c.2–3 cm vs greater than 4 cm) and the individual corollas only 3–3.5 mm across. It also has a shorter corolla tube (5–7 mm vs c.9 mm) and a shorter calyx (c.3 mm or less vs greater than 3 mm). In gardens

Verbena rigida, Barnstaple, North Devon (v.c. 4). Bob Kirby

V. rigida is a popular container and bedding plant, when it might behave more as an annual than a perennial. Stace (2019): 651.

Symphoricarpos × chenaultii (Chenault’s Coralberry). Barnstaple (SS57163242), 6/11/2023, R.I. Kirby (conf. M. Duffell): well naturalised by streamside landscaping that has matured into rough scrub, Rose Lane. The first v.c. 4 record. A deciduous, arching, garden shrub (Caprifoliaceae) with stolons that root at the tips. It is the artificial cross of N. American S. orbiculatus (Coralberry) and S. microphyllus from Mexico. S. albus (Snowberry) is a suckering shrub with pure white fruits (vs fruits usually with white spots on pink or pink spots on white) and glabrous styles (vs hairy). It also has hollow, hairless twigs (vs solid and hairy) and more or less glabrous leaf surfaces (vs leaves hairy below). S. orbiculatus has smaller (4–6 mm vs 6–10 mm), uniformly pink fruits and shorter (1–2 cm vs 2–3 cm), more obtuse leaves. S. × doorenbosii (Doorenbos’ Coralberry) is another garden hybrid (S. albus × S. × chenaultii), and the influence of S. albus is observable in the slight lobing of some leaves and the less hairy lower leaf-sides. Adventives & Aliens News 27, v.c. 110.

V.c. 5 (S. Somerset)

Anthyllis vulneraria subsp. carpatica (Kidney Vetch). Taunton (ST25002568), 11/6/2024, S.J. Leach (conf. J. Akeroyd): 12 plants on rough stony bank on east side of Bridgwater Road, Bathpool Bridge. The first Somerset record of this central European perennial herb (Fabaceae). Adventives & Aliens News 30, v.c. 95.

Davidia involucrata Baill. (Dove-tree). Yeovil (ST552162), 22/10/2024, I.P. Green: small tree self-sown near to parent tree. The first Somerset record. A deciduous tree (Nyssaceae) to c.18 m with a finely fissured grey-brown bark; it is a native of south-western China. The alternate, ovate, sharplytoothed leaves are cordate at the bases and abruptly contracted at the tips; they have slightly branched secondary veins, raised below and densely whitehairy lower surfaces. The inflorescences consist of a mass of many male flowers with one to seven stamens each and purple anthers, and an apically

inserted female or bisexual flower, which unlike the male flowers has a perianth. Each inflorescence is enclosed by two very conspicuous, white, wing-like bracts which have clearly inspired the tree’s best known English names: Dove Tree, Ghost Tree and Handkerchief Tree. The three- to six-seeded oblong ovoid fruit has a greenish, pale-speckled outer surface, turning purplish when ripe, 3–4 cm × 1.5–2 cm at maturity. It hangs down on a c.10 cm long stalk. Planted trees that have narrower leaves with shiny, glabrous lower leaf surfaces are sometimes segregated as var. vilmoriniana

Delosperma cooperi (Hook. f.) L. Bolus (Cooper’s Dewplant). Minehead (SS96864689), 13/7/2024, G.E. Lavender: a c.3 m × 0.5 m patch on rocky bank beside road. The first Somerset record. An evergreen, mat- or lawn-forming perennial (Aizoaceae) to c.15 cm tall, a native of S. Africa and a relatively hardy garden plant in Britain. It has trailing stems and fleshy cylindrical pale green leaves that are up to 5 cm in length. The long-lasting daisylike flowers are c.5 cm across and have numerous glossy, purplish-pink ‘petals’ (petaloid staminodes). Another garden plant from S. Africa, Delosperma nubigenum (Schltr.) L. Bolus, has one record in the DDb for v.c. 11 (2005), BSBI News 101, pp. 42–43. It has smaller ovoid leaves and yellow ‘petals’. In the generic key on p. 531 of Stace (2019), Delosperma comes closest to Drosanthemum – the former differs in having long, subulate stigmas (vs short and broadly triangular stigmas) and leaves that lack conspicuous papillae (vs leaves with very conspicuous papillae) (Eric Clement, pers. comm.).

Origanum majorana L. (Pot Marjoram). Minehead (SS9746), 24/7/2024, G.E. Lavender: the first Somerset record of this shrubby, highly aromatic perennial (Lamiaceae) from northern Africa and south-western Asia. Adventives & Aliens News 15, v.c. 15.

Campanula carpatica (Tussock Bellflower). Minehead (SS96584664), 18/6/2024, G.E. Lavender: on wall by pavement. The first Somerset record. A glabrous, clump-forming perennial (Campanulaceae) from the Carpathians that has decumbent stems and longpetiolate, ovate-cordate, sharply toothed leaves, 1.3–