Bristol Grammar School, University Road, Bristol, BS8 1SR

Tel: +44 (0)117 933 9648

email: betweenfourjunctions@bgs.bristol.sch.uk

Editors: David Briggs and Luke Evans

Art Editor: Jane Troup

Design and Production: David Briggs, Luke Evans, and Louise Cox

Cover artwork: Izzy Hammond

Copyright © November 2025 remains with the individual authors

All rights reserved

BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS is published twice yearly in association with the Creative Writing Department at Bristol Grammar School.

We accept submissions by email attachment for poetry, prose fiction/non-fiction, script, and visual arts from everyone in the BGS community: pupils, students, staff, support staff, parents, governors, OBs.

Views expressed in BETWEEN FOUR JUNCTIONS are not necessarily those of Bristol Grammar School; those of individual contributors are not necessarily those of the editors. While careful consideration of readers’ sensibilities has been a part of the editorial process, there are as many sensibilities as there are readers, and it is not entirely possible to avoid the inclusion of material that some readers may find challenging. We hope you share our view that the arts provide a suitable space in which to meet and negotiate challenging language and ideas.

Writers’ Examination Board

The arts have always been a place to recount our origin stories, to narrate the construction of our individual identities over time. Salma Elsaid’s poems about family stories and culinary preferences achieve this particularly well, conjuring her personal memories for the reader so tangibly we can almost smell the oranges. With similar clarity and skilful use of concrete imagery, Dwiti Acharya and Clarissa Anissimova evoke the memoried flotsam and jetsam of lives lived in very specific environments, with their focused attention to this specificity feeling almost like an expression of love. Ellie Karlin and Sophia Barnicoat use their imaginative power in verse to lovingly consider the tragedy of young lives lost, while Lucy Crawford, in her plangent memoir, also shows love for a departed friend in the clarity and precision of her writing. Historian Angelika Cowell and our guest OB Gary Willmott show a similar devotion to their subjects in Cowell’s lively paean for the novels of Sir Walter Scott and Willmott’s series of haiku for the stations of London’s Circle Line, from which we’ve re-printed a small selection.

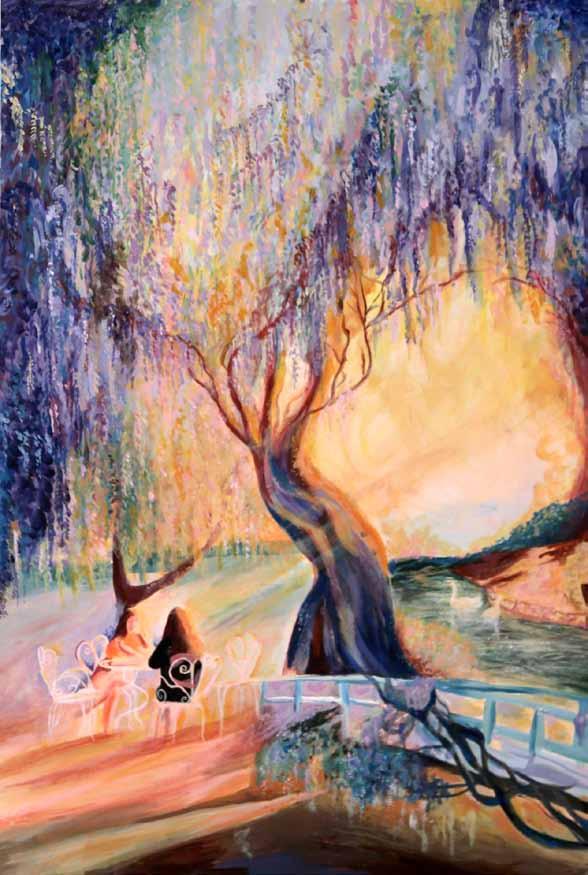

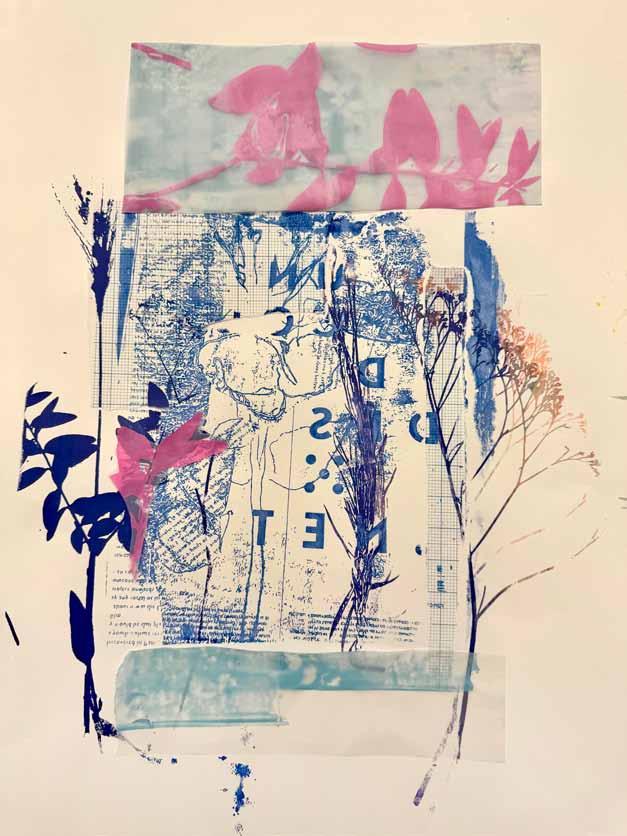

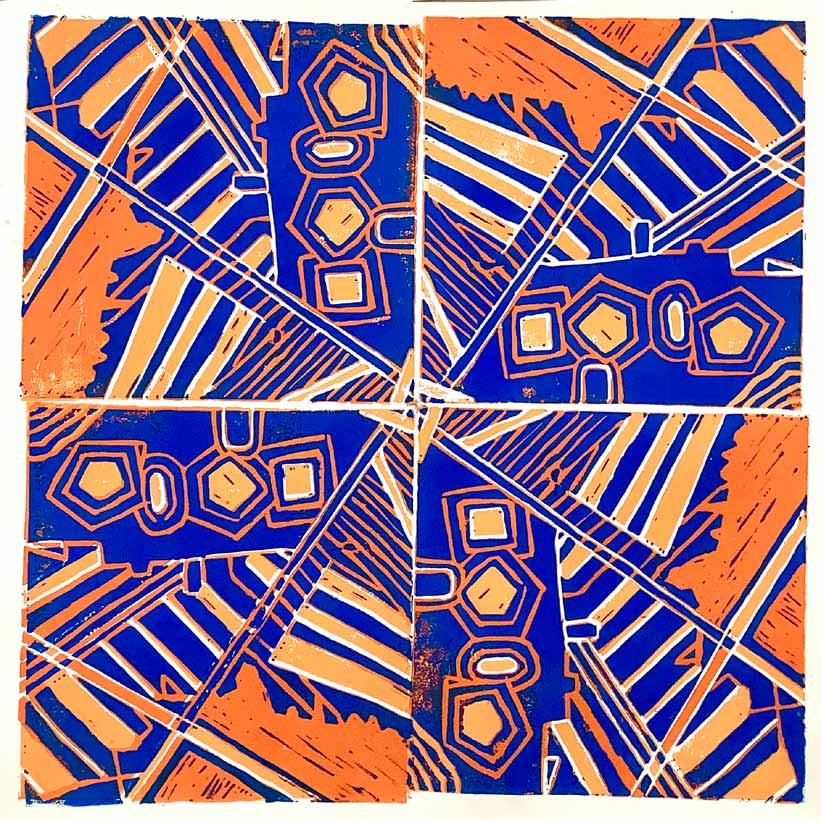

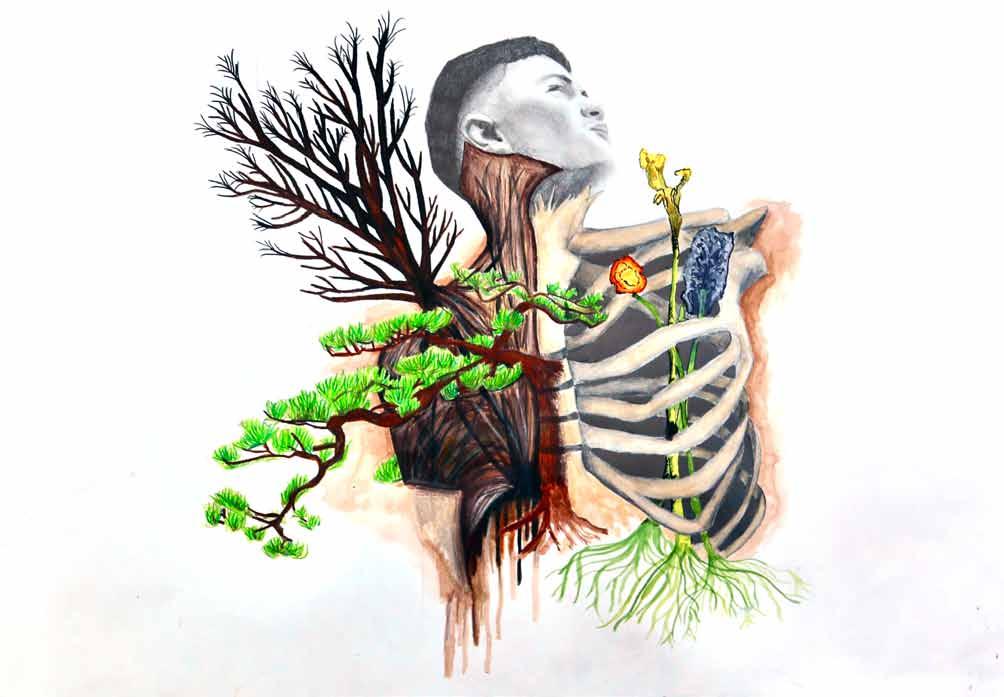

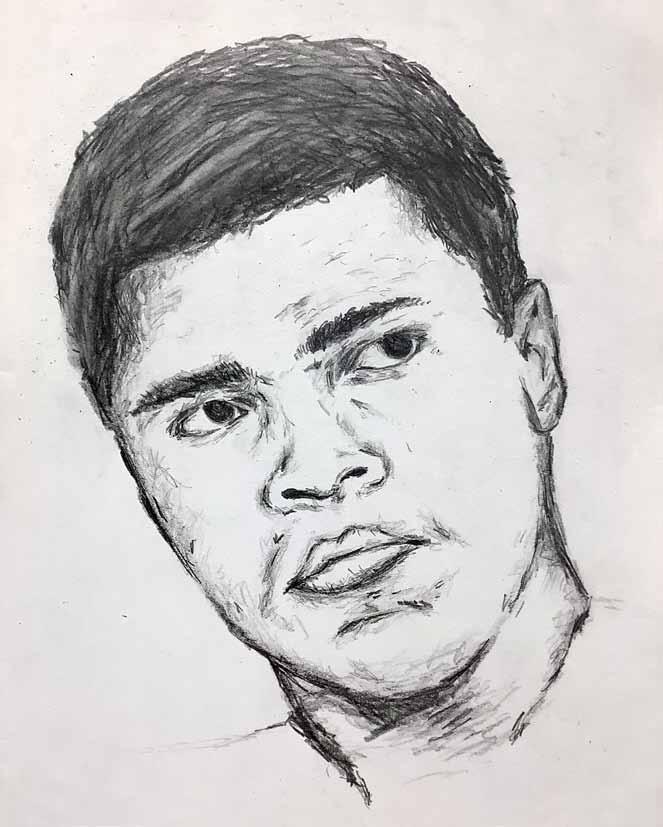

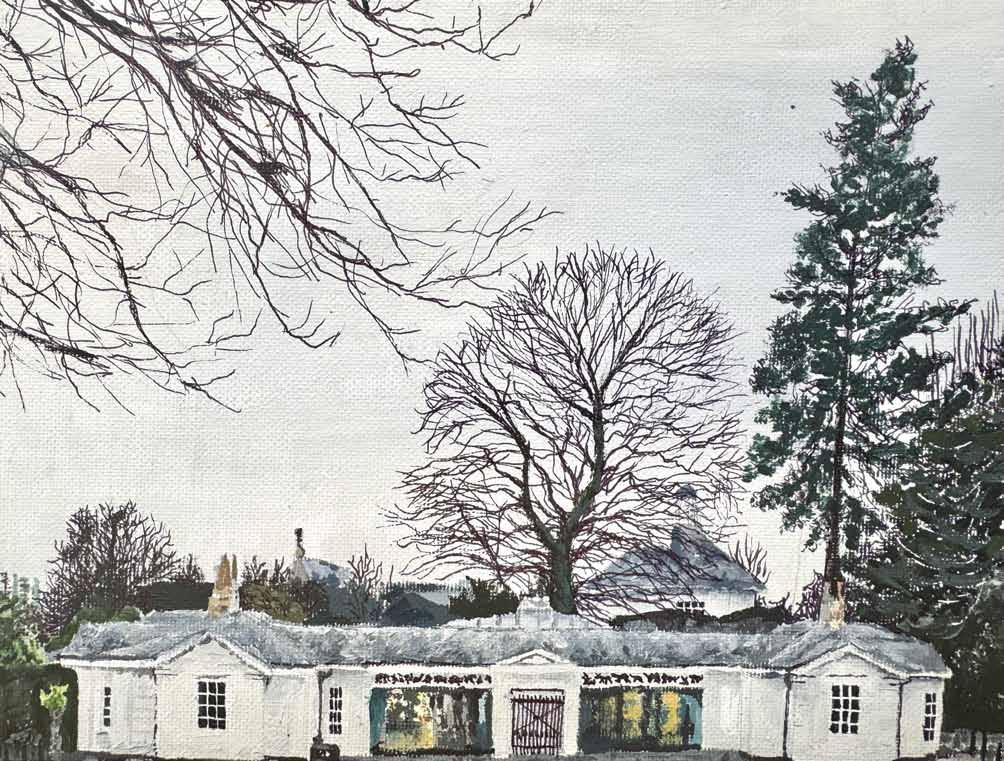

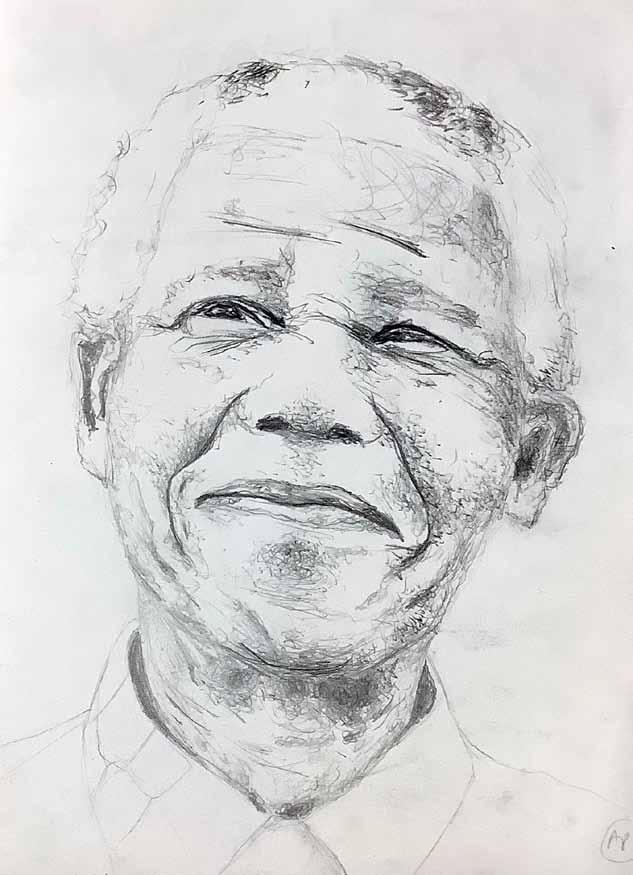

If focused attention and concentration is a way of showing our love for people and places, then it is also a hallmark of the skilful portraiture painting of Holly Osborne-Jones, Peter Scott-Samuel, Alfreda Barroso Taylor, Gita Hosdurga, Sal Errington, and Srisaul Buddha, and of the landscapes, both rural and urban, powerfully visualised by Izzy Hammond, Najma Tus Saqiba, Flora Woodall, Ollie Clayton, Issy Comins, and Anton Velichko. Interspersed among a strong visual arts section in this issue are vibrant mixed media pieces by Ellie Ganson, Amelia Spendley, and Daniel Yates, and sculpture by Iris Massie.

But it isn’t necessarily a requirement of the arts to have a strongly autobiographical element. They function exceptionally well in relation to both the wellness agenda, and the identity agenda, but they aren’t confined only to those arenas. They can simply provide a space for the imagination to unspool, explore, play, reflect. Idiosyncratic short stories from Henry Smith, Archie Granville, Flora Seymour, Miranda Box and Thalia Buck demonstrate this so entertainingly, as do the entries to the 2024-2025 Year 8 flash-fiction competition on the theme of space, from which we’ve included a selection of the winning pieces. Elsewhere in the magazine, Mark Velichko’s rich and operatic screenplay of murderous monks vies for our attention, Anton Velichko and Vihaan Joshi demonstrate great skill in their use of the sonnet form, and Andy Keen’s versions of poems by Sappho – perhaps inspired by Emily Wilson’s marvellous translations of Homeric epic – employ vibrant modern English to re-animate these ancient fragments of verse.

And the arts can, of course, also be political. Naomi Penney’s short story in the voice of a leopard gecko uses wit and humour to manifest ideas from Peter Singer’s questioning of human exceptionalism, and Josh Hawkes and Jacob Turner use painting to foreground significant and inspirational leaders in the civil rights movement, while Elora Roychowdhury uses painting to heighten awareness of climate change and Connie Yeo takes up the digital paintbrush to examine celebrity culture.

The arts are versatile. But however we approach them, we should know that the skill, thoughtfulness, and attention to detail evident in our approach is a measure of our love for our subject. We hope you’ll agree that there is no shortage of love in this ninth issue of Between Four Junctions.

David Briggs and Luke Evans

narratives

i told baba that i am tired of immigrant narratives. it was a moment of weakness – i cannot admit prejudice against myself to anyone. he had just painstakingly explained a poem to me – “kalimat spartacus al akhira” (the last words of spartacus) – and i had listened to him translate the standard arabic into the masri dialect i could parse. and baba said “they would have never made time for this poem if not for our revolution”. but all i remember of it is a night full of celebration and the sound of victorious cheers; what came after is something we seem to have run away from. when baba asked me if i liked the poem i told him that i loved it and when he asked if there are poems like it written in english i told him that i could never write one –for all the political poems i read are immigrant narratives –and i have gone off them completely.

oranges

i.

an orange split in half and thrown up into the sky becomes the sun. peeled and segmented by my grandmother – i wonder how she was able to climb so high.

she recklessly cuts mangos and apples for me, and i stare into the sky to see where they could be placed in the pale blue bursting above me.

ii.

in my grandmother’s back garden, there is a tree. she said it was mine – but before each orange ripens it falls to the ground and rots.

i told my mother that if she were to return home for good i would not follow. could not. she uprooted an orange tree and tried to teach it to love new soil.

i witness her pacing back and forth – her mind a branch that will break at the softest shake of wind. she does not ask if my insides are rotten but i am sure that she can smell the decay of fruit in my ribcage.

my mother slams the door shut and i witness her returning home in my dreams – leaving me with fruit flies buzzing around my fast-beating heart.

iii.

you tried to peel the layers back but as each one fell off there was no core, just layer upon layer of pith and rind and the most bitter seeds.

iv.

each night i used to have my hair braided after it was washed.

sitting in front of my grandmother or mother or aunt, their deft hands

would apply oil to each strand. in the morning, my darkened hair would

be released again – to be re-braided with a satin ribbon woven in.

i do not often braid my hair now –i leave it down until it is knotted

a mess i must work to fix.

v.

mama has kept everything she has ever loved in a drawer. stickers, jewellery, love letters. i cannot help but mirror everything my mother does, so my desk is covered in green envelopes and orange peels. she begs me to throw something away – but i see the boxes of seeds hidden underneath her bed.

vi.

hands dipped in marmalade. i spread my fingers apart and try to see the world through the amber sheen – as i have seen my mother do – but i was not born with the magic she seems to hold in the palm of her careful hand.

vii.

papers covered in scribbles are soaked in smooth orange – a moment of loss i cannot bear.

juice drips over my fingers as i try to dam the spill of sunlight across the kitchen table.

i do not save the notes, and instead must watch them crumble between my palms.

viii.

one day, i’d like to see the marvel in my daughter’s eyes as i peel an orange in front of her for the first time. she would not know where the slivers –filled with sweet juice –came from. perhaps she’d imagine them as the moon placed there by my careful hands.

ix.

they are to tear down her house. my grandma tells me this as she braids my hair in my room. the house where she climbed on top of terraces to sit with the grape vines in when she was younger than i am now. i ask why and how and why again until she tells me that it means more houses –as they are to build flats instead –and i fall quiet. i ask her about my orange

tree. she says that it will be cut down. i see the potential – each orange filled with a future i can only dream – whilst the still green spheres drop onto the ground and are left to rot. the tree will never grow ripe fruit.

I Come From

Roald Dahl book collections and solitaire. A Now That’s What I Call Musicals CD that’s older than me. New bikes that would get stolen by the end of the week.

I come from E6 sketchbooks from Hobbycraft

Half filled with pencil drawings of Ginny Weasley. Wednesday afternoons in the park, waiting For my sister’s 11+ tutoring to end.

I come from long drives every weekend

To cities with bland names like Hull or Stroud. Watching my sister play chess tournaments And getting to hold her trophy on the car ride home.

I come from hot chocolate in late December

In front of the Brailsford Lights Christmas Display And drives to Heathrow at four in the morning For flights that leave at noon.

I come from headlines about a virus in China

And the world shrinking to a house and a garden. Listening in to my sister’s lessons on Teams, Watching her draw the houses across the street.

I come from desks spaced six feet apart. Library books left in crates for days to disinfect.

And waiting impatiently for 8pm on Thursdays So I could clap and talk with my neighbours –The only other people I would see all week.

I come from Shelves of foreign novels and travel books, From the bark that follows the sharp slam of the neighbour’s basement gate, From the ‘calling’ sound on Skype.

I come from the sound of Classic FM at almost every meal, From scrambling to learn a new piece for Monday’s lesson, From practicing my sight-reading and scales, From ‘CBHCTYHOB Ha MOP03’ (whistlers go in the frost).

I come from mantelpieces full of trinkets, Matryoshka shaped candles, small clocks.

From French verb tables, watching films on the weekend, From You’ve Got Mail to The Parent Trap.

I come from occasional Sunday walks in Arlingham by the River Severn, From leaving dough to rise by the boiler, From buckwheat porridge with milk and sugar.

I come from playing makeshift poker with sea glass found on a beach in Brittany, And slapping away mosquitoes while grilling marshmallows On the dying flames of the barbecue.

I come from jumping into cold seawater on a hot summer’s day, And from cycling home after a trip to the market Trailing a smell of fresh peaches.

Guilt cannot purify What happened in the snow, As that red-blood sloughed Out, out.

You swore you felt Remorseful, Because you cannot be Guilty.

“It leapt straight up.” You’d swear it in court. You weren’t neglectful –Promise,

As that ether-dark Swamped and coated His face.

Because it wasn’t your fault.

They called you too late –Nobody had been watching. So there was nothing to be done. Just a girl,

Clutching a wooden spoon Frightfully tightly.

And a boy

Spread-eagled on the kitchen table,

Arm on the closest chair. And, compounded into the floor, Bootprints, one after another, Accusingly crimson –

Tracked in from the frost. Little, less, nothing. So wash the floor. Clean the saw.

It makes no difference; Winter will be hard anyway.

Working from Anne Carson’s translations of the fragmentary remains of Sappho’s poems (shown in purple), Andy Keen has stepped into Sappho’s sandals to imagine complete versions of these poems. Here is a selection from ‘The Sappho Versions’.

To sail is to speculate, And it is with gladness and Relief when we set out And go with good luck, And happen to gain the harbour

And the safety of black earth. Poseidon, in your mercy,

Protect those hardy sailors Who go forth in big blasts of wind

While we wait upon dry land And watch for their return.

For those who sail And transport the freight Are bold, when The easier course by far Is to stay at home, for many On the land will try

To recreate the dangers of the sea

By artificially making hardships

For themselves: great works

Not at sea, but on dry land,

To bring on shipless shipwrecks. Poseidon, in your mercy, Protect them too.

You used to garner envy, As lovers gave you greedy glances, But now it’s only pity, Your lip trembling In uncertainty. Your flesh by now old age Has overtaken. Your long dress covers Your ankles, as a boy flies in pursuit After some other girl, Whose pale and noble Shoulders are on show, taking His attention: but sing to us ! You are the one with violets in her lap, For it is song these days that mostly Amuses, for the boy eventually goes astray.

Tomorrow, we die. But for now, we live : To hope always for the future is the opposite of living in the immediate now, daring to feel, feeling to live,

living to dare. For the rawness Of life is sweet, But its fruit Is brief and sour, And so, we must live And sing of life, Not in a thin voice But boisterously, for all to hear.

The moon lights up the land; The stars whisper softly: it’s time to quit. It’s over, the hour has come, Yet here you are, luxurious woman, Working the room, sobriety fading, Eyes aching in the night, Your fragility on show.

My toxic relationships frequently Come back to haunt me, for those I treat well are the ones who most of all Have a tendency to harm me. It makes me crazy

To think of those poor souls Whom I have forgotten In my need to nourish the venomous. Although I love you, I want

To see you made to suffer. I wallow in myself: I am Aware of this, And yet all too often I repeat the pattern, And for that, I am sorry.

As I lie awake, I hear the inscrutable deep sound of the ocean rolling outside the window. I get up and go out, just an old lady walking on the sand, in the dark, my fluttering robes and jingling necklaces drowned by ocean’s sound. The ocean is king, Sweeping all away. Nothing survives it. And one by one, I take them off And hurl them into the waves: This one I bought for Gorgo But could not give, Although I tried, Overwhelmed by fear. Into the waves. This one was for Gyrinno

But no, I could not give. The fear came again. Into the waves. Into the waves. Into the waves.

Beneath the water’s surface, all is quiet and calm. The boy’s arms and legs don’t thrash, but jerk, this way and that, as if someone, far away, is yanking on a length of string. Most nights, imagining this moment, he’d hear his scream echo into the ocean’s apathy, taste the salty tang of its indifference, feel the tide of anguish in his open mouth – the same as the boys in the news stories with faces like his. He couldn’t have imagined that when his dreams turned real, finally, he’d hear only his mother’s laughter descending into tears, taste only the brownies his sister made on weekends. He never imagined he’d feel the tug of the string in his back as he watched the child’s face morph into a blur of bad jawline and teenage acne. Just before it finished, his own eyes floated before him, swimming with salt.

G ARy W ILLMOTT

London has long been a passion of mine and I’ve decided to return to a project I began some years ago: walking the Underground. It’s a remarkable way to discover the highways and byways of this bold, beautiful, unruly city; to learn its storied histories, view its architecture and infrastructure, and to experience the unfolding tapestry of its cultural diasporas. Each station opens into a world shaped by movement, memory, and migration. To walk the lines enables one to feel a sense of place in a city built by people as much as by planning; generations of immigrants who’ve brought with them their religions, rituals, traditions, food, community, and love. But also by those born and raised here, who have lived through the city’s changes, held its stories, and kept its everyday life turning quietly, constantly, and often thanklessly. Sadly too, as the city has grown, so some of those communities have been displaced by economic imperative and lack of opportunity.

Having previously walked three lines, I can vouch that it’s a revelatory experience. One that reminds me just how much multiculturalism gives us; not in clichés or token symbols, but in the shared resilience, creativity, care, and complexity that make this city more than the sum of its parts. But aside from that aspect of discovery, it is also wonderful to experience and record the stunning cityscapes and amazing architecture that has always defined the city and will continue to do so.

I’ve resolved to write a haiku triptych for each line and the Circle Line triptych can be seen here. Should you wish to follow the journey, I’m documenting it on Instagram @garystubewalks.

excerpt

Triptych I

Circle Line Reflections I.

Yellow, spiral line

Daffodil burst into bloom

Whoosh. Stillness descends.

II.

Walk: 32 stops.

Rain taps soft. Summer longed for. Thunder. Train passes.

III.

Counterclockwise – East.

Look West: a pause, maybe hope. Silence. One hand claps.

‘Upon

Upon the stage where softest shadows play, An instrument of power rests in peace. Its strings, like secrets, whisper night and day, Yet hold the strength to make the silence cease. The player steps with purpose, calm and bold, And strikes a chord that pierces through the night. Notes dance like fire, bright stories to be told, Awakening the dark with vivid light.

The neck, a path where nimble fingers roam, Unfolds a world of sound both wild and free. Through every strum, a universe could comb, A symphony of dreams that stirs the sea. Electric heart, your voice will ever soar –A timeless song that resonates, and more.

The dew twinkles in rays of morning dawn –Cascades of quiv’ring beads on each young leaf, Its gentle head looks down upon the lawn, The tender petals sagging full of grief.

The skeletons of trees creak in the gale, Which pulls its spindly stem from side to side. It stutters, flailing wildly, face all pale –Bracing itself to win the forceful fight.

The winds subdued, the tempest passes by. It shivers, shrugging off the melting snow From silken petals. A fragrance of a sigh Ebbs silently into sunset’s warm glow.

The snowdrop stands peacefully, still alive. The first flower to wake up and to thrive.

The shabby, colourless satellite, once the pride of mighty civilisations, now floats lifelessly, dented by asteroids. Planets hang cracked and wrinkled, scarred deeply by long lasting battles from long ago. Streaks of ice and hardened lava dominate their wounded surfaces, like frozen tears from a multitude of sorrows. Constellations and once-vivid nebulas dim and fade as they evaporate, like paint peeling off the walls of a long-forgotten nursery.

He shuts the dusty lid of the box of toys, preparing it for exile in the attic. His childhood has finished. There is no more space for these vague, distant memories.

I’m lost. That’s my name. Lost. Quite appropriate, considering my predicament. I’m lost inside a keyboard. Like the one that you use every day.

How I became Lost? Well, I was born, but I’m assuming that’s not what you meant. You meant how I got inside the keyboard, didn’t you?

Well, I was working on some Chemistry project when I spilt something on me, and the keyboard, and Whoosh! Here I am! For now, I’m in the SPACE key, in your computer! That is why you CANNOTHITTHESPACEKEY! I’m holding it up! How cool, right?

Not for me! Get me out, now!

Elena sat in the tiny apartment, silence pressing from all directions. Walls that were once a flashy white now bore the darkness of things lost. She’d swept shelves bare, tucked away memories – but the space remained heavy. Not the wide kind – cosmic, infinite – but the aching kind, the kind that echoed with laughter now absent.

She sat cross-legged in the centre of the room, a solitary beam of light warming her face. Maybe emptiness wasn’t absence. Maybe it was possibility. A clean slate. She closed her eyes, inhaled deeply, and for the first time in months, space felt like home.

I am floating. Floating towards my demise. Disconnected from my tether, I stare into the black abyss of space, my grave. I have approximately one minute until my oxygen is depleted.

I can see my crew rushing to their suits, but I know that it is too late. As I turn, I see a new side of the abyss, one of beauty and wonder. Fingers made up of gas and dust stretch into the unknown. Gleaming stars light up my helmet.

If this is my grave, it is all I could have ever asked for.

Three seconds left.

Goodbye, space.

Children are the worst. I’ve heard this is something of an unpopular opinion, but it really shouldn’t be. I’ve also seen many who seem to actively enjoy the presence of children. This is deeply disturbing. In the vast majority of cases, their behaviour is to be tolerated stoically, bearing in mind the sad fact that they are an essential part of the ecosystem and that we all once counted ourselves among them. Well, except for me. I never did.

I have however been in continual observation of those who willingly spend time with these heartless monsters – the poor wretches – and have concluded that they are simply so used to bad behaviour that their standards have lowered to an unspeakable extent. Case in point: Jack.

Jack likes to poke his finger as close to my face as it can get. He sticks his tongue out at me then grins like some idiotic wannabe comedian, complaining to his friends – while I’m sitting right there next to him – about how boring I am. It is utterly humiliating. We spend an hour together on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays and they are without a doubt the worst days of the week. Each time he walks into the room, I curse whatever potent substance the Biology teacher must’ve been drinking to have put this little tyke beside me on that seating plan of hers.

But Jack, despite having a moral compass more broken than the beaker Ruby dropped last Tuesday, receives the most praise of them all. Jack writes down one incorrect sentence about photosynthesis and it’s all: ‘That’s great, Jack!’, ‘Have a Praise Point, Jack!’, ‘Well done for all your hard work, Jack!’ Hard work, my balls.

Jack had asked the child in front for their notes. Jack had been playing pirated Blockblaster for the last hour. Or rather, he’d been trying to play pirated Blockblaster. The kid’s not possessed an ounce of logic or critical thinking in his entire short life. He’s died hundreds of times and, believe me, it is infuriating to watch.

My point is, these youths are savages. I never truly realised this until approximately one week ago. I should probably preface by telling you that I’ve been ill of late. It’s not been fun. I had the most terrible fever and couldn’t stand up for days. I just lay there snoozing, and boy did Jack have a field day then, ridiculing my monotonous behaviour. The worst part though had to be the pain. A stabbing pain, the kind that strips you of any dignity. Like the flipping over of a test paper to reveal an embarrassing score, which seems to leave one vulnerable and altogether miserable. A pain reaching to the core of my aforementioned balls.

It took a long while for the lab techs to notice I wasn’t crawling out of my cave to say hello, but after a few days the uneaten food rather gave the game away and I was shuttled over to the local vet for a diagnosis. It wasn’t cancer, thank goodness. For a guy in my position, that would be the end of the line. My ailment was in fact a testicular infection, which was for a short moment a relief until I realised the cost of treatment. Five hundred pounds. And for my death? Eighty. The time scale wasn’t exactly friendly, either. The treatment had to be administered within a fortnight and school closed up for half term that Friday, giving the Biology department a very small window to garner funding.

But boy did they use it.

Though my vision was somewhat foggy, I could make out people in my room during the next lunchtime – highly unusual. Those in the tanks on the opposite wall were taken out and held by small hands; there was chatter and a faint clinking of coins in a box on the table. I slowly uncurled myself and walked gingerly to the glass to gauge the situation. Pretty much all the Biology teachers were there, gathered around the other reptiles, trying to waft children in with smiles and the promise of letting them pet cute animals. I could faintly hear a determined voice outside the door repeating the same loud words to passers by: ‘Come inside! Meet the Biology animals, and donate to save our leopard gecko, Mike!’

It was strange hearing my own name yelled out among the din of feasting students, but a strange kind of warmth draped itself over my shivering frame as I realised there was some salvation for lizards like me. I might be free of this ridiculous pain in my nether regions, recover my full senses to observe the Science lessons, and have the privilege of watching Ruby smash yet another piece of glassware.

This made me smile for a time, and there I lay happily in the centre of the chaotic classroom, until I heard a dreadfully familiar voice reach me from the crowd – that of my nemesis.

‘But can’t they just buy another one?’ Jack eyeballed me as he whined. ‘This one never does anything anyway.’

What a mean little shit. I thought, my head throbbing. I hope he gets expelled.

After wandering aimlessly down the aisle, I shuffled into the final pew of Holy Trinity Church, bathing in its musty grandeur. The chandelier above solemnly flickered away as my frame trembled in the full unflinching gaze of the setting sun, which shone imperiously through the inky reds and blues of the crucifixion.

He bore the face of my son.

Albie was drinking with the other players, they had said. Filling the tavern with his laugh and jest and boyish grin. All three of which vanished when a hooded figure stalked into the candlelit pub.

Vision blurring into the plaques dedicated to Stratford’s dead and gone, I marvelled at the way the arches looped and curved majestically in my periphery. The organ stood as sombrely as it had during the funeral, and I remembered how I’d envied its steadfast sobriety, when all I could do was sob. I turned back to the elevated Christ. His eyes bore into mine – I looked away.

“Could a gambler seek salvation?’ I thought. “A spineless, debt-ridden gambler responsible for the death of his own boy?”

As I stood up with a creak, my eyes on the moonlit tiles beneath me, I imagined him to be smiling. A controlled, magnanimous smile which seemed to say, “You’ll have to find out. You don’t have long to wait.”

I hoped my fate would lie up in the tresses with those cherubic carved faces, one of which, no doubt, was my son’s. A chill ran through the emptied hall, as I realised with a shudder that my blood-sprinkled clothes were realistically packed and ready for the

fiery depths beneath my flapping soles. I tried to ignore the blade which lay benignly in one of my hands, pretending it was a propdagger for one of Albie’s plays and not the instrument of his revenger.

“He’s all that I have,” I had cried over and over, pleading guilty to whichever God was listening as I drove my carving knife through the spleen of the infamous lender whose money I’d squandered, doling out the same pitiful death he’d given my innocent son. It pained me to realise that he, with his money-grabbing eyes and threats upon threats, was to be my roommate for all eternity.

To evade the fast approaching raised voices which I could no longer ignore, I ambled over to the grave of the poet, his stone silver in the cold night. Albie had recited his plays as a boy, and until now I had never truly understood the sentiment behind those florid words.

“The readiness is all,” I muttered hoarsely, kneeling at the wordsmith’s tomb as the shouts of the constabulary flooded my senses.

“Aye, the readiness is all.”

Admittedly, Waterside is never fully quiet in warm weather, but the midsummer fair causes quite a commotion. It is traditionally three days long. On the first, market day, folk flock to the boats to trade earnings for whimsical ornaments and other worthless antiques. The second is when weddings happen, where you can split the cost with other happy romantics and say your vows around a roaring bonfire.

The final night is a masquerade. My mother is still adamant that such dances are treacherous. Many unchristian peoples use masks to hide from God, she said. To commit evil. But my older sister Margaret vehemently argued that no one could hide from God, I was the perfect age to attend, and she would chaperone. Margaret’s mood has been especially low recently, so my poor mother could only give in.

The boat is hot and dense. The windows are low, and I can see filthy water rising, lapping repeatedly against them. The sea of people sways to jazz. My sister and I wear matching masks, dresses and jewels. I feel invisible, and I’m sure Margaret would agree –if I could find her. A waiter wades through, offering drinks, and the crowd thickens.

“A glass?” The waiter waits and his eyes squint beneath a thick mask.

I take a glass and he raises a hand. Beckoning. Pointing to a side door. To the kitchen, perhaps? Or to nothing? I shake my head. The waiter shakes his, too. Gestures angrily. I clutch at my dress, pretending to have lost something else, and keep stepping backwards until I bump into someone and spill their drink. Then I run off the boat.

When my sister Margaret returns home hours later, she apologises. “Shouldn’t have worn the same outfit as you,” she laughs ruefully.

I daren’t ask if she and her lover made amends.

I doubt I’ll see them at the weddings next midsummer – if there even will be a celebration at all, for there are fewer unions every year, and I hear that the event planners are now considering them as a futile investment.

Suddenly, Phoebe felt a hand pull at the back of her head. Somebody yanked the wig from her scalp and her real hair fell to her shoulders. Phoebe turned around to see her furious-faced brother clenching the wig in his hands.

Phoebe Bell had been striding up Chapel Street, trying to look as natural as possible in her brother Ephraim’s coat and itchy white wig. Recently, her grandfather had died and left Ephraim the sum of £20. What did he leave Phoebe? Spoons. A rusting collection of silver spoons. Obviously, this was totally unjust, so Phoebe had devised a master plan to claim the £20 which was rightfully hers, or at least half of it for a new petticoat she had her eye on.

To Phoebe, the clearest course of action had been to disguise herself as Ephraim and go to Midland Bank. So, she had sauntered in to attempt to claim the money.

“My name is Ephraim Bell, I believe there is £20 here for me,” she muttered in the most manly tones she could muster, and looking at the floor in order to hide her clearly feminine features. The banker looked at her sceptically but then began to shuffle through some papers. He seemed to believe her, the plan was about to work.

Phoebe heard a sharp cough from behind her. “What do you think you’re doing?”

Phoebe stood awkwardly facing her brother, who was still clutching the wig. “I can’t believe you just tried to steal my inheritance!” He cried, frantically waving the wig about in the air.

“He left me spoons Ephraim, spoons!”

Ephraim sighed and began ushering her out of the bank.

“I hate primogeniture,” Phoebe muttered under her breath. She would be stuck with the spoons after all.

The old willow stood alone at the edge of the marsh, its gnarled branches reaching out like skeletal arms, as if grasping for something just beyond its reach. The marsh was a quiet place, the air thick with the scent of damp earth and the constant hum of unseen creatures. Beneath the willow, the ground was soft and spongy, the sort of ground that seemed to breathe with you, shifting with every step you took.

In the heart of the willow’s twisted roots, hidden beneath a blanket of moss and creeping vines, lay a hagstone – an ancient, worn stone with a hole bored clean through its centre. It had been there for as long as the tree had stood, maybe longer, though no one could remember exactly when it first appeared. Some said it had been left by the spirits who once inhabited the marsh, others that it was a gift from the moon itself, its light passing through the hole to reveal secrets hidden in the dark corners of the world.

The hagstone had an eerie quality. No one dared touch it, for fear of what might be revealed or what might come through the hole. The old woman who lived at the edge of the village – some called her a healer, others a witch – had often been seen standing near the tree, her sharp eyes watching the stone with a quiet intensity. Some said she could peer through it and see the threads of fate woven into the world, while others claimed she used it to communicate with the forgotten things that lived in the fog.

It was on nights like this, when the moon hung low and full, casting a silver sheen across the marsh, that the willow felt most alive. The wind whispered through its branches, and the air seemed to shimmer with a strange, unspoken energy. Those brave enough to venture near the tree often felt a chill run down their spine, as if the willow was watching them, listening to their every breath. The hagstone pulsed in the moon’s glow, its hole catching the light in a way that made the world beyond seem both near and impossibly distant. If you stood there long enough with your face just inches from the stone, you could almost hear the murmurs of the past, the lost voices of those who had come before, all waiting for something. What, exactly, none could say.

But there was one truth that held: the willow, the stone, and the marsh were not simply part of the world – they were a part of something older, something far deeper than anyone could ever understand.

Jonathan Johnson had been teleporting around for days, using the inbuilt cosmic railroad makers on his wheelchair to travel from planet to planet, looking for a connection to earth and a phone to use.

He’d arrived on an advanced land at first, but they ran from him, for no reason. Jonjon thought they might have been able to see Back-in-Black, his sit1. Most people wouldn’t be able to see sits, but they may have descended from sit users, and so the aliens’ blood may have had more potency.

Jonjon didn’t care. The next planet he landed on was still in its Stone Age, so he travelled on quickly, not before beating a sit user with a sit called Ugh-Oog, which he could only assume was a popular song on that planet.

It was very annoying how the system he was working in had much more limited reception, but JonJon carried on, hoping to make it to a planet closer to earth.

Jonjon wanted to phone his father, Geoff Johnson, and make sure he was okay, because Geoff Johnson’s old ward, a chap going by the name of Rio, had recently escaped from jail. Rio had been arrested for taking an illegal super-soldier serum that transformed him into something near a vampire – he could touch sunlight, or holy symbols, but he was impervious to pain, and could drink people’s blood.

Jonjon had stopped him, but now that Rio was free again, he might come after Geoff and Jonjon.

Jonjon had travelled across half the sector when he arrived on a planet with the right connection, but there was a problem. Everyone turned him away, or ran from him, but it wasn’t fear in their eyes, it was hatred. Of all the planets, he’d had to arrive upon one with the worst ableist teachings known across the galaxy.

After a long search, and being continually shunned away from public areas, Jonjon finally found a phone box. But there was a man in there, a man with high muscle definition, most likely not gained naturally. He was wearing a gold jacket that was high cut and had large shoulder pads, paired with gold trousers, and a belt with a heart clasp, on top of a purple looking shirt. As Jonjon looked up, he saw the man’s blonde hair, and a cruel sharp-toothed smile, and the line of blood dripping down his chin as he threw a frail, lifeless body to one side.

1 Sits are a physical personification of someone’s will, that have special powers. Back in Black was the ability to make an area go pitch black for a certain amount of time: the larger the area, the shorter the period of darkness.

Every year in December we yawned as Mum dragged us to the kitchen. She’d be covered in flour, with streaks of batter glistening on her forehead, as she furiously mixed the Christmas cake bowl, commanding us to pass her the sugar, or a spatula, as she read from a magazine. We enthusiastically obliged, as throughout the year she proceeded to then make various Simnel cakes, iced cupcakes, birthday cakes, for us, the neighbours, cousins, anyone she met on the street. We spent hours in the kitchen, happily whiling away the hours perfecting lemon drizzle cakes and sprinkling sugar on various biscuits.

When the Silver Jubilee arrived, she made multiple Victoria sponges, and we went to next-door’s house and marveled as a procession marched through London on their colour TV.

Around the house, she would order Dad to mow the lawn, angrily shouting at him if a blade of grass was a centimetre taller than the rest. She went ballistic if she saw us running around the block playing tag with other kids, and would angrily corral us back inside then plonk us in front of the piano to practise.

Mum fussed with our collars and combed our hair obsessively, and could spend hours carefully applying makeup and putting on the most fashionable clothes before she went anywhere – even if it was just to the local Woolworths or Tesco. But the definite highlight of her week was when she strolled down to the shops to buy her magazines. We trotted eagerly after her in perfectly-ironed shirts as she carefully perused the latest Vogue or Good Housekeeping. Before buying her many magazines, she would nervously look in her purse, then try to nonchalantly hand over money to the cashier.

As we started to grow up, it became a regular occurrence for shouting matches to be held in the kitchen: doors would be hastily slammed shut as Mum and Dad heard us coming, but it could never muffle the noise completely. The rest of the time, Mum had a permanent harried look about her and became even more frenetic about small things. She started to go everywhere in a stunning pink cocktail dress complete with high heels no matter the occasion, walking down the pavement as if she was a model, and the pavement her catwalk. Christmases and birthday were now horrible, as Mum insisted that we be increasingly more enthusiastic and smiley for the camera, as she shoved camcorders in our faces, filming every moment possible, then mailing the tapes to friends with captions like ‘Our Magical Christmas Celebrations’ or ‘Peter Absolutely ADORES His New Book’.

When Dad left one night, her fake grin grew even wider, even as it became harder to paper over the cracks in her life. I woke up one night, unable to sleep, and found Mum on the sofa, twenty housekeeping and lifestyle magazines piled up beside her, the lamp still on and her cocktail dress askew. An empty bottle of wine was beside her.

One summer, she began making all the watches we owned tick exactly in time, to the millisecond, and started scouting around the house, looking for imperfections.

After we eventually left home, fed up, she spent days in our old room, repainting the walls on a weekly basis, dusting and

vacuuming the carpet hourly. As she grew older, she refused to move to a nursing home, spending her days in our bedrooms with thickly-slathered-on make up.

Then she died, makeup brush in hand, and the outdated house was demolished to make way for a new motorway.

Icons

Procreate® digital artwork

E LORA ROy CHOWDHURy

Icons

Procreate® digital artwork

Collections

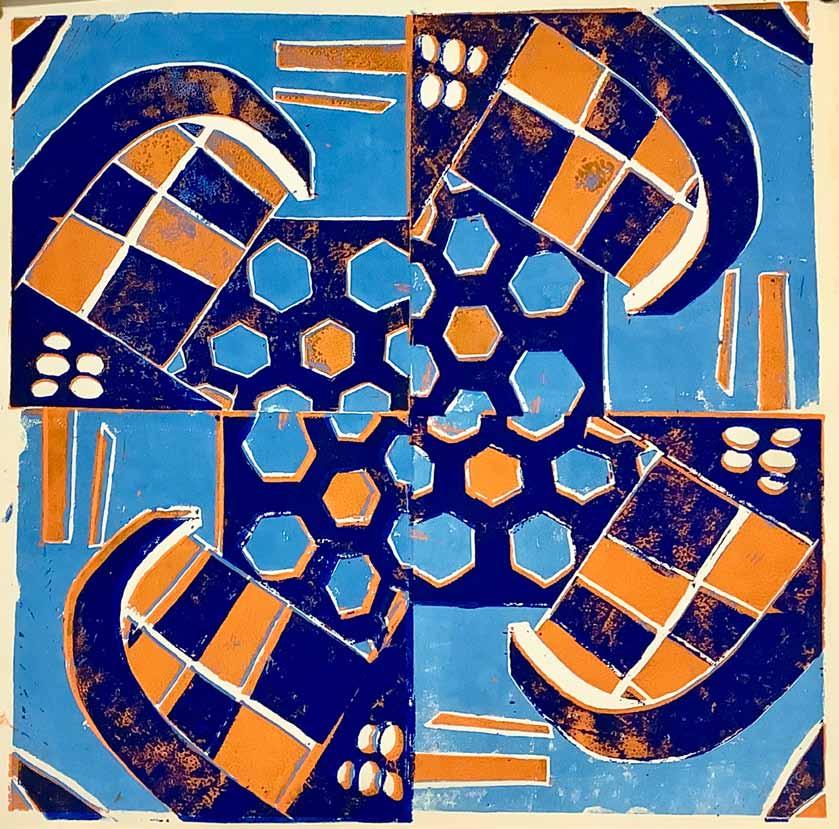

screen print

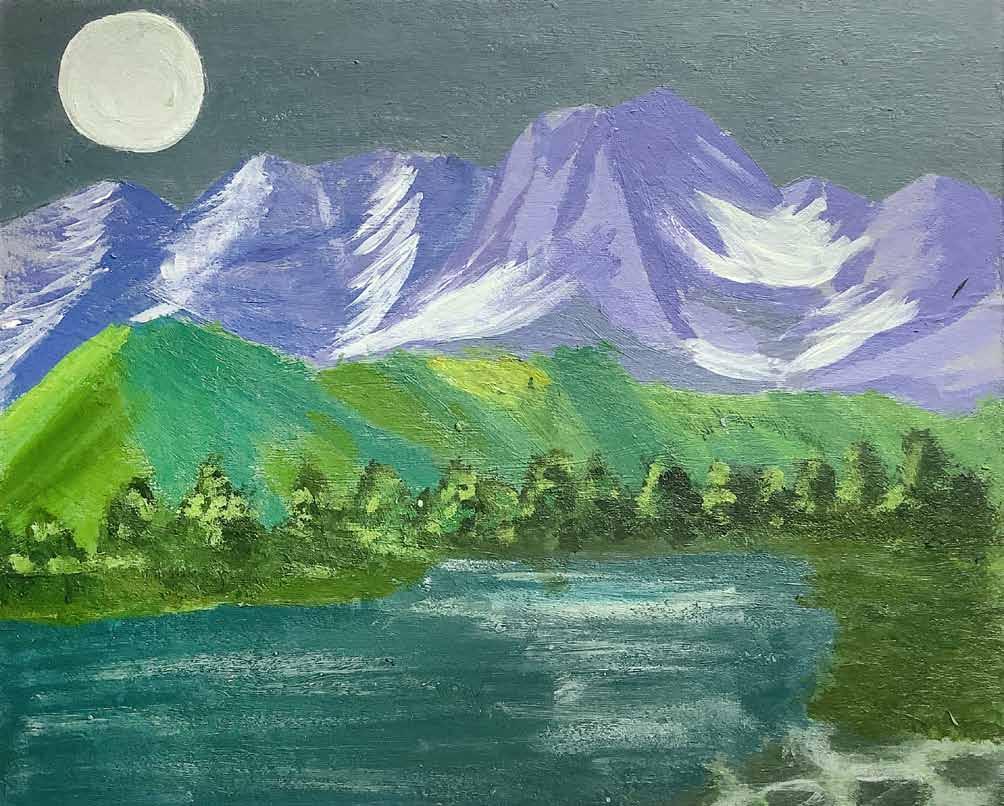

Landscape Remembered acrylic on board

Architectural Extraction linocut

Fantastical Beast

air-drying clay and acrylic paint

Memorable Landscape

H O lly Osb O rne-J O nes

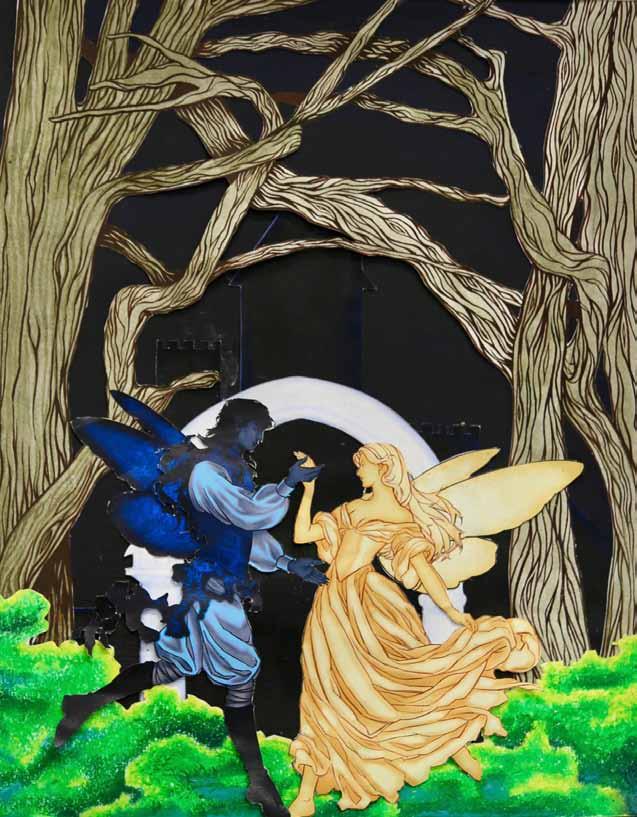

Oberon and Titania ink and dip pen, in relief

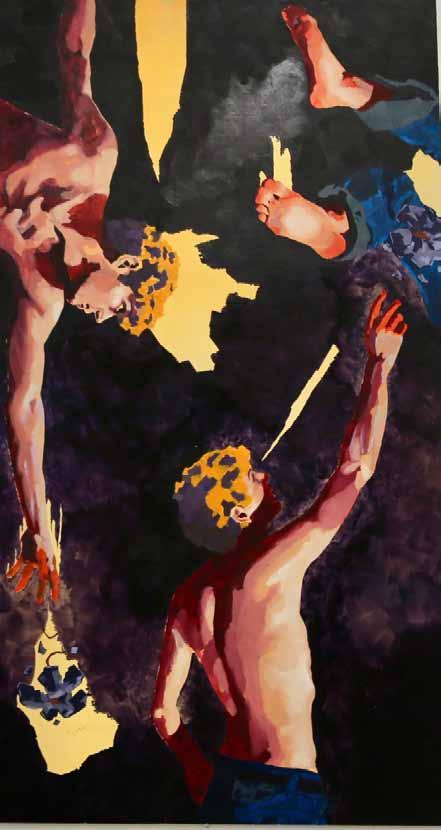

Untitled oil on board

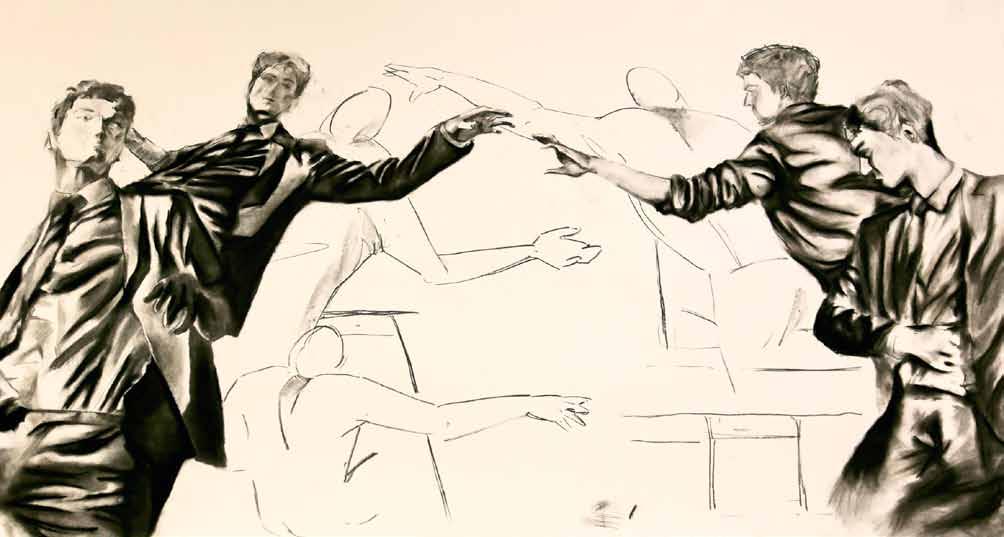

Dance Sequences – Human Form ink and tape on paper

Untitled pencil and ink on paper

ACOB T URNER

Icon pencil on paper

Untitled charcoal on paper

My Uncle pencil on paper

Childhood Memories

For some time now, and for reasons I cannot accept, reading Sir Walter Scott, once the world’s greatest literary figure, has fallen out of fashion. It is now on trend to declare him (with or without reading anything he has written) long-winded, unreadable, overly romantic, historically inaccurate. In my opinion, Sir Walter Scott is none of these any more so than, for example, Charles Dickens (and we all love him – and rightly so). Sir Walter Scott is a comic genius, a creator of strangely-named memorable characters, Shakespearean in their eccentricities, and he writes settings which are as colourful and visual as Thomas Hardy’s. He was once seen as the greatest novelist in and of his time, not just in Britain but all around the world. He has the largest monument ever made to a literary figure in the world on Princes Street, Edinburgh, he has that city’s main train station named after one of his novels, and a football team after another. Many of our cultural references about Scotland come from him, such as those associated with Burns’ Night. How can we have brushed him aside?

Sir Walter Scott was first a famous poet and then gave that up, largely because he claimed that his good friend Byron, writing at the same time, could not be bettered. He began writing novels at a time when reading novels was not in favour, not seen as acceptable reading material. I’d argue we can thank him for making them so. His most famous novels, the Waverley novels, are mostly set in Scotland around 100 years or so before he was writing (1815 – 1832). Some are set earlier. He came to define Scottishness following the time when Scotland could have become subsumed as part of the Union. Hailed as father of the historical novel, his passion for equipping his reader with historical facts may be at times over-zealous (there are many appendices and long detailed introductions) but once you love Scott you cannot help but admire the tenacity of his fervour for putting his definition of a Scotland that no longer existed into the permanence of the written text. He really wants his reader to understand and remember!

Yet, in reality, the historical minutiae behind his plots can easily be put aside. I’d advise you to skip his introductions unless you are a history geek (let’s remember that I am one). If I have persuaded you to read Sir Walter Scott, I’d start with Guy Mannering (the second Waverley novel) then go back to Waverley (the first), reading on from there. His stories do not generally rely on the history, however when they do, the history is fascinating because it is not the perspective that we learn here, down south.

My message is to be your own judge and avoid pre-judging. There are flaws in his writing, of course, but there is more to lose by not reading him. Trendy? Who cares. A good book is a good book is a good book. And Sir Walter Scott knew how to write them.

“I remembered my classmate, recently.”

“What about her did you remember?”

“I tried to … She feels hard to pin down in my mind now. I remember trying to memorise what little I knew of her – I don’t think it worked. She feels like a bad dream, something I can’t fully grasp, if that makes sense.”

“What was her name?”

The crash of waves on the shore, the tug of a strong wind. The grey of a Sunday; a crowded, silent room. November nineteenth, January twenty-first.

I can feel the tug of gravity as I’m pulled down again. I must have answered Heather because she says, “How does it feel, to forget?”

The flashes of memory feel like a hand around my throat, telling me not to speak. I feel the same recycled tears.

“It feels … inevitable. Horrible. I used to see her everywhere.”

The slant of a nose, the volume of a laugh, a certain shade of blonde, a girl with a ponytail with her back towards me. She opens her mouth, but I can’t hear her.

“Do you feel guilty?”

“Sometimes, when I don’t catch myself. It took me a long time to process all of it, to not feel guilty.”

We both know there’s so much more there, but she has learnt to read me very well. Heather knows when not to push, when to show me mercy.

I never talk about her, because the only people who understand have already said what there is to be said, and the rest have no idea what it was like. It took me almost six months to finally bring her up with Heather. It makes me tired, feeling as though I am back in it all. I am thankful every time, though, when I remember that it stays in the room behind the opaque glass.

She tries to find me, sometimes. Along the coastline of West Scotland on the eve of my fifteenth birthday, wrapped up in the gales and the crash of waves on the shore; in a silent, crowded room that reminds me of the day we were told; in the grey of clouds on a Sunday; every November nineteenth, every January twenty-first. Every time she appears I feel the sinking of my chest again and the same tears, so salty and bitter, scratching the sides of my throat. I catch myself forgetting too – forgetting her laugh, how she looked in my memory alone. I have completely forgotten how she sounded. I saw her almost every day for two years, and I cannot remember how she sounded.

When she does find me, I feel the incompleteness in my chest and the crevices of my mind – stories without all their parts, things left unsaid, actions not taken. Although I forget her, I can never forget the tears and the faces of grief and guilt.

Remembering hurts, but forgetting is something I know I will do, a tide I can’t stop.

We see a bird’s eye view of Constantinople at early dawn - a vivid red glow perches on the rooftops of the city, contrasting harshly with the narrow, capillarylike network of dark streets below. The camera gradually narrows down on the dome of the Hagia Sophia, its metallic crimson glint reverberating with each steady tremor of the Great Church’s bell. However, this bell toll doesn’t disturb the morning stillness of the city, by contrast, the deep vibrations act as a (somewhat unsettling) foundation for the thin, watery dawn to spill over.

Eventually the bell toll fades, and we hear a faint rendition of the orthodox chant Agni Parthene, lurking in the depths of the dome’s shadow. The baseline, a low D, is rather prominent, throbbing ominously and very much audibly underneath the melody. The melody itself is unnaturally rhythmic and plain, almost like a funeral march.

The camera begins to descend, eventually coming to focus on a white statue of an angel above one of the entrances to the Hagia Sophia. The chanting grows louder. A small bead of water rolls along the cold marble of the statue’s face, reflecting the fiery skies above. Perhaps this is the dew, or a pipe has burst somewhere in the building; its origins are of no importance. As the amber droplet comes to an uneasy halt, dangling hesitantly off the angel’s cheek, a blurry procession of hooded figures beneath it comes into view. The camera focuses in on the procession, and we see them more clearly – a group of monks, heads bowed, walking solemnly into the Great Church. One of the monks is swinging a thurible, its golden chain creaking lazily in time with the chant, which by this point is at full volume.

INT. HAGIA SOPHIA, DAWN.

The interior is still dark, except for a few delicate blades of sunlight leaving golden trails on the ornate iconostasis. The chanting stops, and the first bars of

the 2nd movement of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony begin playing. At first the music is only a slight rustle, drowned out by the priest, who has begun to growl something in Greek; his words scatter and lose themselves throughout the vast emptiness of the cathedral.

The monks form a solid semicircle around the back of a small shivering crowd. As one of them (MONK 1) adjusts his cloak, we catch a glimpse of the hilt of a dagger. The music grows in volume; the priest can no longer be heard.

MONK 1 gulps and shoots a fleeting glance at MONK 2, who is standing next to him. MONK 2 pierces his lips but continues looking forwards with a strained motionlessness. The music reaches bar 75, except the timpani part is replaced with a sudden tolling of bells, causing a collective shudder to ricochet through the glazed walls. The forceful peals have a jarring and pulsating quality to them; one can almost see cold waves of compressed air break over the stunned congregation.

MONK 1 gasps as the harsh polyphony resonates through his body and looks at MONK 2, who is starting to sweat profusely. He nods.

With mechanical swiftness both monks reach into their cloaks and draw their daggers. Whilst they aren’t in complete slow motion, their movements, as well as those of the other characters are weighted and trance-like, as if some sort of viscous, invisible fluid has filled the nave of the Great Church.

The two monks launch themselves at a tall man in front of them, who is wearing a fur hat and holding a thurible. Just as their blades are about to make contact with the folds of his cloak, the camera switches to show the thurible falling to the floor. It descends with painstaking slowness and bounces on the tiled floor with several dull thuds, veiled by the thunderous bell toll and music.

The camera returns to show the two monks, one of whom is clutching the man’s fur hat, the other struggling to support the body of the man himself. It is unclear whether the man is dead or wounded. The monks gape at the pale glimmer of his bald scalp, clearly appalled and confused.

Suddenly MONK 1 shoves MONK 2 out of the way to reveal another man, wearing an identical hat, hurrying towards a small wooden door in the corner. The man tears at

the rusty handle, which comes off with a large chunk of rotten splinters. He throws it on the floor and starts hammering at the door with his fists. We cannot hear him, but from the movements of his thin, weathered lips we can deduce that his cries use a narrow range of vocabulary.

As the monks close in, he turns to face them. A single ray of light cuts diagonally through his face, and in that crimson streak we see a bestial expression of pure terror.

In a last-ditch attempt to save himself he dashes to a small altar adjacent to the door and wrangles a simple wooden cross out of its iron holder. A heavy panting sound is heard as the man raises the cross above his head in a vain attempt at parrying the monks’ daggers.

The camera zooms in on the altar, as the panting grows more jagged and raspy. We see a splinter from one of the arms of the cross sink through the air above it, coming to rest on a large scarlet stain that is steadily eating into the white altar cloth. The camera cuts out.

INT. IMPERIAL BEDCHAMBER, MORNING.

Emperor LEO is writhing in his bed, wave upon wave of convulsions coursing through his muscular body. He opens his bloodshot eyes and sits up, panting heavily.

Salma Elsaid

Dwiti Acharya

Clarissa Anissimova

Sophia Barnicoat

Andy Keen

Ellie Karlin

Gary Willmott

Anton Velichko

Grace Jackson

Vihaan Joshi

Albie Frayling

Naomi Penney

Miranda Box

Thalia Buck

Henry Smith

Archie Granville

Flora Seymour

Connie yeo

Elora Roychowdhury

Izzy Hammond

Flora Woodall

Ellie Ganson

Issy Comins

Amelia Spendley

Daniel yates

Iris Massie

Ollie Clayton

Najma Tus Saqiba

Holly Osborne-Jones

Peter Scott Samuel

Gita Hosdurga

Salvador Errington

Jacob Turner

Joshua Hawkes

Srisaul Buddha

Alfreda Barroso Taylor

Angelika Cowell

Lucy Crawford

Mark Velichko