Advanced Science Research Journal

ADVANCED SCIENCE RESEARCH PROGRAM

The Breck Advanced Science Research Program is the capstone course of the Breck science curriculum. This program gives students who are passionate about science and engineering the opportunity for an authentic, high-level summer research experience in collaboration with research professionals in universities, colleges or businesses.

Following the summer research component of the program, students participate in a year-long science research seminar class where they write and submit formal research papers and project presentations to the Twin Cities Regional Science Fair, Regional Junior Sciences and Humanities Symposium and the Minnesota State Science and Engineering Fair, with some students continuing on to the National Junior Sciences and Humanities Symposium or the International Science and Engineering Fair. In addition, Advanced Science Research students participate in a formal seminar at Breck where they present their work to family members, research advisors, and peers.

More information about the Breck School Advanced Science Research Program is available on our website: breckschool.org/asr.

Dr. Kati Kragtorp, Director Advanced Science Research Program

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pulling the Pressure Piece

Defining the Role of Piezo1 in a Mouse Model With Rheumatoid Arthritis

Graham Bailey and Samantha Dvorak

Turf Trouble

Does the DEET in bug repellent really kill grass? Year II

Abigail Endres and Selena Qiao

Immune Interference

Is aberrant DUX4 expression responsible for the downregulation of MHC class I genes stimulated by IFN-γ?

Abigail Getnick and Kelan McKay.

Farewell Forever

Degradation of Pentadecafluorooctanoic Acid Using UV-C Light and Titanium Dioxide

Dawson Miller and Caleb Li

The Piece Within Using Matrix Metalloproteinases to Cleave CD200 to Combat Cancer

Structure

Does Caffeine Help You Study? Investigating the effects of caffeine on adolescents’ long-term memory and sustained attention

Health Evaluation Robot for Basil – HERB

A modular robotic system for detecting nutrient deficiency in greenhouse basil

Unique Creeks

Monitoring Nutrient and Bacteria Levels in Rivers to Determine Factors Affecting Water Quality

Charlo Vasicek

Use your mobile phone to scan the QR code included in each article to watch videos of our students’ presentations.

Pulling the Pressure Piece:

Defining the Role of Piezo1 in a Mouse Model With Rheumatoid Arthritis

Graham Bailey and Samantha Dvorak

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases affect 10% of the world’s population (Autoimmune Disorders Found to Affect Around One in Ten People | University of Oxford, 2023). Affected patients experience chronic and painful symptoms that reduce their quality of life Despite the wide impact of autoimmune diseases, the various pathways behind them are not fully understood, leaving patients with limited access to adequate treatments. Two such autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and autoimmune valvular carditis affect millions of people around the world In the case of RA, up to 1% of the world’s population is affected, and, although valvular carditis is rare within the United States, it affects 40 million people around the world and is more common in areas with limited access to antibiotics (Osinski et al , 2024)

To fight off infections, the immune system has a complex organization of cells that are capable of recognizing and killing foreign invaders This requires molecular recognition of antigens so a coordinated response can be mounted To prevent the immune system from accidentally attacking the body, there are complex mechanisms that allow it to recognize material in the body as “self” and prevent the development of an autoimmune disease Several factors cause tolerance mechanisms to break down, including similar molecular structures between foreign antigens and other materials present in the body When tolerance mechanisms fail, the patient develops an autoimmune disease (Autoimmune Disease - an Overview | Science Direct Topics, n.d.). Despite similarities in the overall mechanism, there are a vast number of different autoimmune diseases, and a lot of diversity even within a single disease Because of this, treating autoimmune diseases frequently

focuses on dampening the entire immune system rather than targeted treatment, putting patients at risk for serious infections

In one type of autoimmune infection, rheumatic fever, a build-up of autoantibodies due to Group A Streptococcus infection causes an immune attack on various tissues throughout the body When antibiotic access is limited, patients can experience prolonged and repetitive infections (Marijon et al., 2012). The molecular similarities between Streptococcus antigens and human proteins, including cardiac myosin and extracellular matrix protein laminin, can cause molecular mimicry in which the immune system mistakes a self-component for a foreign antigen (Galvin et al., 2000). Activated B cells produce antibodies against the peptide, causing a build-up of autoantibodies that circulate through the body People with these autoantibodies will sometimes subsequently develop rheumatic fever, in which the heart and joints become temporarily inflamed (Galvin et al., 2000). Repeated exposures to Streptococcus antigens, and subsequent repeated episodes of rheumatic fever, increase the chance of developing long-term autoimmune diseases, such as RA and autoimmune valvular carditis.

In RA, disease progression begins with an immune response towards the joints in the body. As neutrophils are recruited into the joint cavity, they secrete leukotrienes, including leukotriene B4 (LTB4), which stimulates the mass infiltration of neutrophils (Chen et al., 2006). After leukocytes have invaded the synovial membrane, surrounding fibroblasts and macrophages are also activated, causing cartilage destruction and bone erosion (Smolen et al , 2018) As the disease progresses, patients begin to develop hyperplasia, resulting in tissue growth that fully surrounds the joint, known as a

synovial pannus, that causes additional damage to the bone and cartilage in the joint (Chen et al., 2006) This process causes long-term joint damage, decreased mobility, and chronic pain characteristic of RA (Smolen et al , 2018)

Through a similar and sometimes concurrent disease mechanism, autoimmune-induced valvular carditis causes chronic inflammation of the mitral valve, leading to calcification, stenosis, and oftentimes congestive heart failure (Marijon et al , 2012) In valvular carditis, autoantibodies bind to the mitral valve, causing inflammation and infiltration of immune cells, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix growth (Raizada et al , 1983) As valvular carditis progresses, the mitral valve thickens and calcifies, preventing normal function and allowing blood to leak between the chambers of the heart (Marijon et al., 2012). Eventually, the mitral valve’s reduced functionality requires a valve transplant; however, many patients with this disease have limited access to healthcare, and are unable to receive one Even when patients are able to get a transplant, only the symptoms of the disease are being treated, and not the underlying mechanisms that caused it, putting them at risk for further complications (Marijon et al , 2012)

The K/B.g7 mouse model is used to replicate and research Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD) and RA disease progression. Though these mice develop autoantibodies against a different antigen than in humans with RHD and RA, the cellular mechanisms resulting from these autoantibodies are comparable. The K/B.g7 mouse model has a transgenic T cell receptor (TCR), called KRN, and additionally expresses the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class II molecule g7 a combination that induces arthritis and valvular carditis in mice (Monach et al., 2007). K/B.g7 mice produce anti-glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) autoantibodies that cause the immune system to attack the joints and mitral valve (Monach et al , 2007) Autoreactive T cells then recruit B cells that produce anti-GPI autoantibodies, which accumulate in the joints and are assumed to

accumulate along the lining of the mitral valve (Breed & Binstadt, 2015). This antibody deposition targets the tissues of the joints and heart valve for attack by the immune system In the K/B g7 mouse line, the mitral valve is infiltrated by macrophages and CD4+ KRN T cells (Gorton et al., 2010). A transfer of serum from K/B.g7 mice to a non-K/B.g7 mouse induces autoimmune- mediated arthritis that is less severe than arthritis in K/B g7 mice, and does not induce valvular carditis

In patients with RA and RHD, the tissues surrounding areas affected by inflammation experience greater mechanical stress (Liu et al., 2022) In RA, synovitis causes increased joint stiffness, and in RHD, blood flow causes high mechanical pressure Mechanosensing proteins and ion channels are capable of sensing and responding to the stress present in the joint and heart (Liu et al , 2022) PIEZO1 is a mechanically sensitive ion channel capable of responding to mechanical stress by promoting inflammation (Liu et al , 2022) Based on the known proinflammatory effect of PIEZO1 in other heart diseases and its involvement in immune responses in the heart valves and joints of K/B g7 mice, it is theorized that PIEZO1 promotes the chronic inflammation observed in autoimmune valvular carditis and arthritis (Xie et al., 2023).

To study the effect of PIEZO1 on RA, we compared data on the severity of inflammation, bone erosion, and cartilage erosion in ankle tissue from Tcsf21-Cre Piezo1 floxed mice (Piezo-) to that of wild-type/Tcsf21-Cre mice (Piezo+). The Piezo- mice have Piezo1 deleted from Tcsf21-expressing fibroblasts, which was theorized to promote inflammation in this model and may be similar in humans We also analyzed the morphology of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained heart sections to make sure this remained unaffected in the Piezo- model.

Materials and Methods

Mice treatment and tissue collection

Piezo1 fl/fl Tcf21Cre+ (Piezo-) and wt/fl Tcf21Cre+ (Piezo+) mice were treated, handled,

assessed, and sacrificed by trained researchers, according to an established, IACUC-approved protocol, as part of the ongoing research conducted by this lab We did not have any direct interaction with the mice Serum from K/B.g7 mice was injected into recipient Piezoand Piezo+ mice. The recipient mice received two doses of 150 μL of serum given two days apart, totaling to 300 μL These mice were sacrificed on day 11 After the mice were sacrificed, their ankles and hearts were fixed in paraformaldehyde. Other researchers sectioned and stained the ankle sections using H&E, TRAP, and Safranin O.

Fixed mouse heart embedding protocol

Paraformaldehyde-fixed hearts in 30% sucrose solution stored at -20°C were put in a paper towel. A razor blade was used to cut off the apex of the heart about 1mm up from the tip. Then, while squeezing with tweezers to avoid air bubbles in the heart chambers, the heart was put in a 15 mm cube base mold filled with Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound (OTC Compound; Tissue Tek). The base mold was frozen using -20°C isopentane with dry ice then stored at -80°C.

Cryosectioning of heart tissue for mitral valve protocol

OTC molds with hearts were cryosectioned in a LEICA CM3050 S cryostat at -22°C Molds were mounted using OTC Compound then trimmed in 30 µm sections, adjusting the orientation until the blade was at the same angle as the heart. Additional sections were removed until two separate chambers of the heart appeared, after which the width of sections was shortened to 8 µm Once the mitral valve was reached, the next 45 to 30 sections were plac ed three to a slide on positively charged slides.

Cryosectioning of heart tissue for mitral valve protocol

Slides with the desired tissue were submerged in a 1x PBS (Gen Clone) for 5 minutes The area around the sections were dried, then outlined

Graham Bailey and Samantha Dvorak

with a pap pen (Invitrogen Super Pap Pen 00-8899).

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining of frozen heart and ankle sections protocol

Sections were covered with hematoxylin quick stain (Vector lab; H-3404) and allowed to sit for two minutes Then, the hematoxylin quick stain was tapped off and rinsed with tap water In a chemical hood, the slides were submerged in the following solutions: eosin stain for 1 minute, 95% ethyl alcohol (EtOH) for 5 minutes, 95% EtOH for 5 minutes, 100% EtOH for 5 minutes, then 100% EtOH for another 5 minutes Finally, an a dult researcher submerged the slides in a Xylene solution for 10 minutes, and mounted slides with VectaMount (from vector lab H-5000). The slides were left in the hood to dry overnight

Measurement of mitral valve leaflets

Under a microscope at 10x magnification, cellSens software was used to measure the widest part of the mitral valve.

Scoring

We assessed levels of synovial inflammation, bone erosion, and cartilage erosion in ankle sections by assigning clinical scores from 0 to 3 based on the severity of damage to the tissue per the SMASH protocol A score of 0.5, 1.5, or 2.5 was assigned when some of the criteria of the more extreme case was met but not to the usual full severity In between scores were also often based on relative differences between the inflamed joints. Images were first analyzed independently by both student researchers and then scores were compared and discussed to reach a consensus on the final score We were treatment-blinded while doing the analysis

Synovial Inflammation

To assess for synovial inflammation, the density of immune cell infiltration and the extent of hyperplasia of the synovial membrane were evaluated at 4x magnification as previously described in Hayer et al (2021) Half scores

were assigned for samples in between with characteristics in between scores.

Bone Erosion

To assess bone erosion shown from H&E staining in joints, the integrity of the bone shape, lesions, and level of bone penetration were evaluated at 4x magnification as previously described in Hayer et al. (2021). Half scores were assigned for samples in between with characteristics in between scores

TRAP

To assess bone erosion levels using TRAP staining, we evaluated the density and area frequency of osteoclasts stained. Based on the range of results in our data, we created a scoring system Half scores were not assigned to samples

Cartilage Erosion

To assess cartilage erosion shown from Safranin O staining, the cartilage presence and concentration were evaluated at 4x magnification as previously described in Hayer et al (2021) Half scores were assigned for samples in between with characteristics in between scores

A one-way ANOVA was used to determine statistical differences in morphological scores between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice

Results

Ankle examination

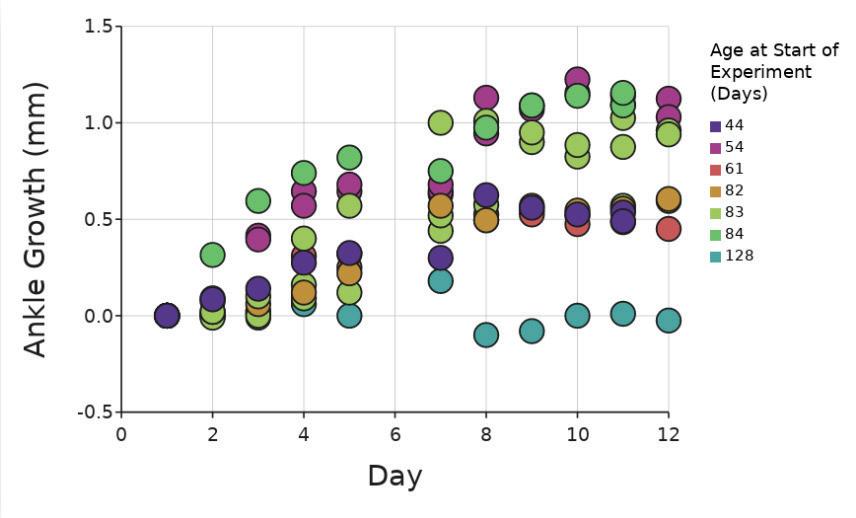

Researchers took ankle measurements and assigned clinical scores based on the level of inflammation observed. These measurements were taken each day, over the course of 11 days from the start of treatment. There was a significant difference between the mice based on age regardless of Piezo1 presence (p < 01; two-way ANOVA, Figure 1) due to a Piezomouse that was significantly older, at 128 days, than the other mice which had ages ranging from 44 to 84 days at collection. This mouse appeared to have far less growth in its ankle, likely due to being past the age of natural growth Even with the inclusion of this mouse, there was no

significant difference in ankle growth between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice (p = 0.08; ANCOVA).

Figure 1. Increase in ankle size (mm) in vivo compared to Day 1. Dots show individual ankle growth compared to the number of days into the experiment. Dots show individual scores for 44 days old mice, (n=1); for 54 days old mice, (n=2); for 61 days old mice, (n=1); for 82 days old mice, (n=1); for 83 days old mice, (n=3); for 84 days old mice, (n=1); for 128 days old mice, (n=1) Figure by authors

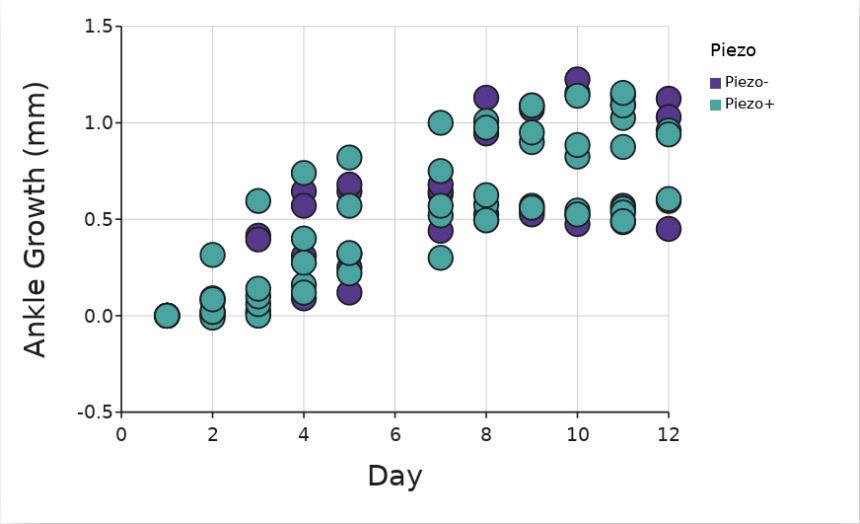

There was no significant difference in ankle growth in vivo between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice with the mouse that was 128 days old at the start of the experiment excluded (p = 0 90; ANCOVA, Figure 2) This mouse was excluded for all subsequent in vivo analyses

Figure 2. Increase in ankle size (mm) in vivo compared to day 1. Purple dots are Piezo+ mice (n = 5) and teal are Piezo- mice (n = 4) One Piezomouse was excluded due to age Figure by authors Clinical scores of ankles in vivo

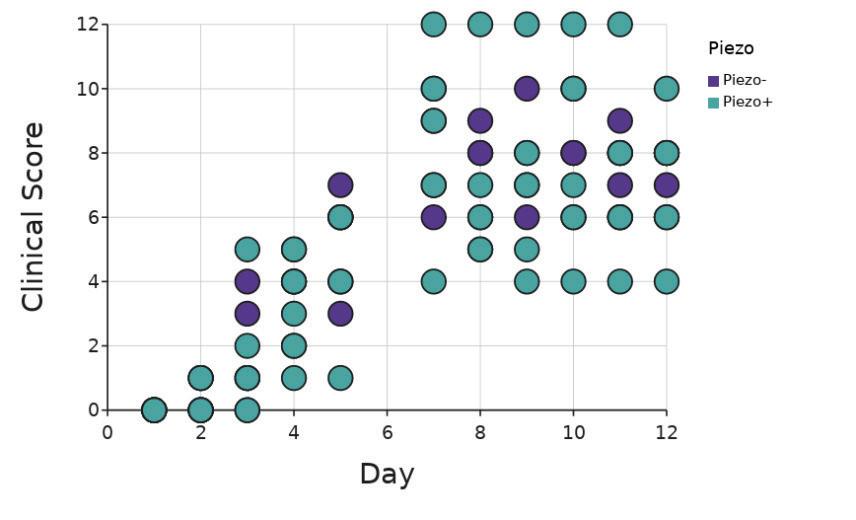

Ankles of mice were assigned clinical scores based on the level of inflammation observed by trained researchers over the course of 11 days from the start of K/B.g7 serum treatment. There was no significant difference (p = 0.32; two-way

ANOVA, Figure 3) in ankle clinical score in vivo between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice. For this analysis, the 128-day-old mouse was removed

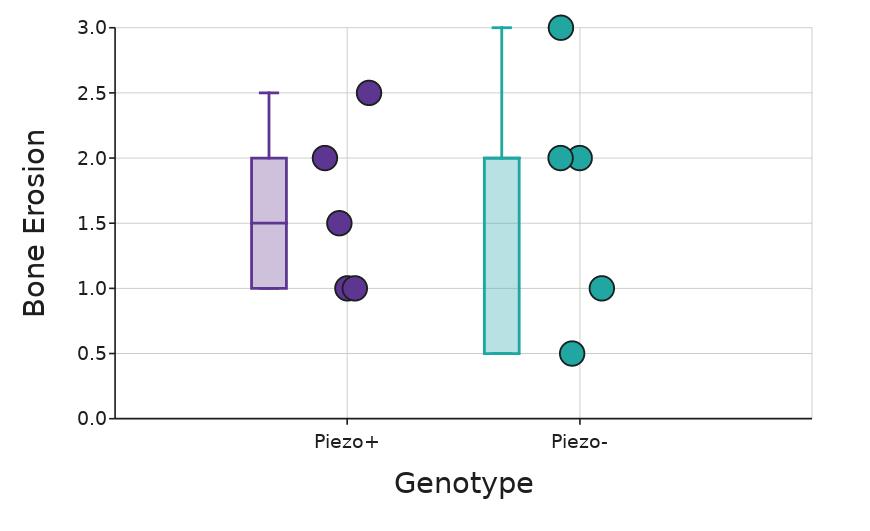

Bone erosion

Scores of bone erosion were assigned to ankles stained with H&E from Piezo+ and Piezo- mice collected after 11 days of K/B g7 serum treatment (Figure 4). There was no statistically significant (p = 1.00; Mann-Whitney U, Figure 4) difference in bone erosion presence as evaluated by the SMASH protocol and observed with hematoxylin and eosin staining between the Piezo+ and Piezo- mice

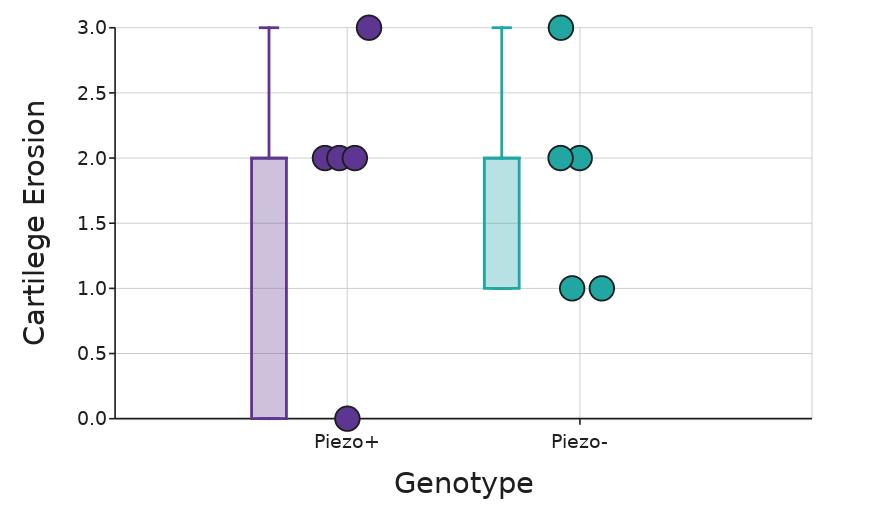

Cartilage erosion

Scores of cartilage erosion were assigned to ankles stained with Safranin O from Piezo+ and Piezo- mice collected after 11 days of K/B.g7 serum treatment There was no statistically significant (p = 0 91; Mann-Whitney U, Figure 5) difference in cartilage erosion presence as evaluated by the SMASH protocol and observed with hematoxylin and eosin staining between the Piezo+ and Piezo- mice.

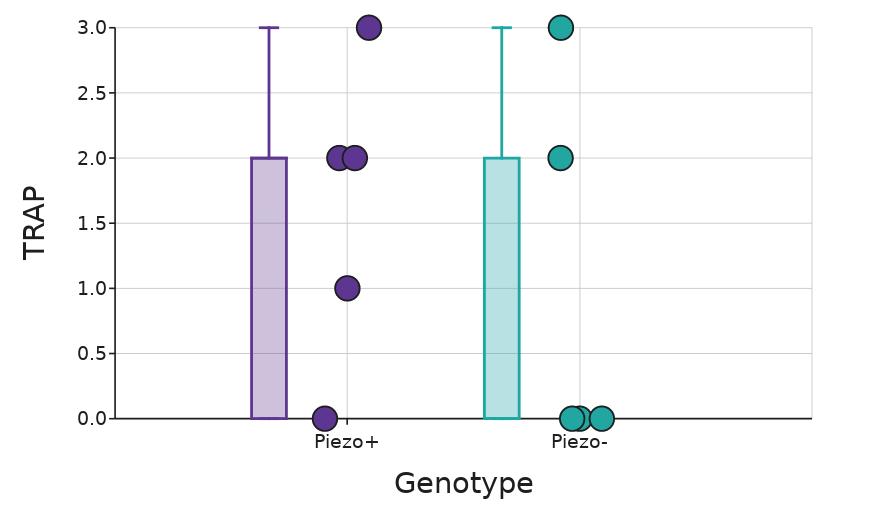

TRAP staining

There was no statistically significant (p = 0 51; Mann-Whitney U, Figure 6) difference in osteoclast presence as evaluated by the SMASH protocol and observed with TRAP staining between the Piezo+ and Piezo- mice.

Figure 3. Total ankle clinical score in vivo. Purple circles are Piezo+ mice (n = 5) and teal are Piezomice (n = 4) One Piezo- mouse was excluded due to age Figure by authors

Figure 4. Bone erosion score separated by genotype. Box whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points). Dots show individual scores for Piezo+ (n = 5) and Piezo- (n = 5) Figure by authors

Fgenotype. Box whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) Dots show individual scores for Piezo+ (n = 5) and Piezo- (n = 5). Figure by authors.

Figure 6. TRAP score separated by genotype. Box whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) Dots show individual scores for Piezo+ (n = 5) and Piezo- (n = 5) Figure by authors

Heart data

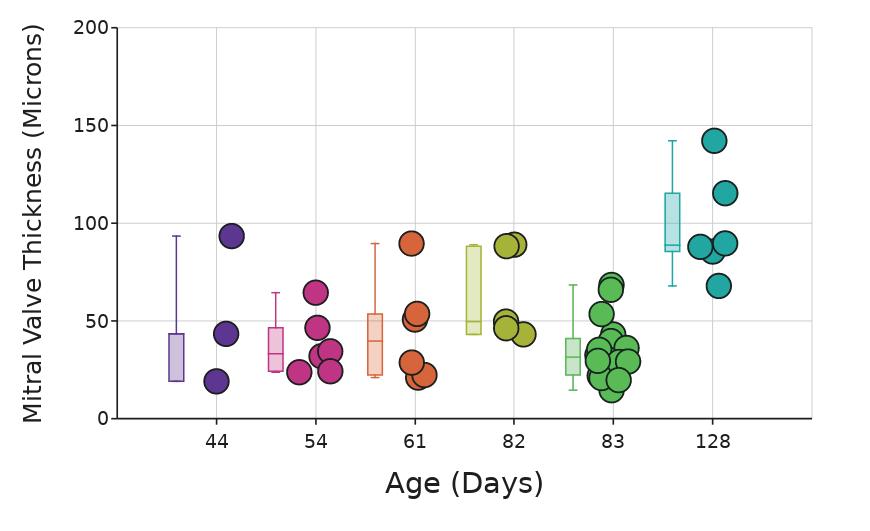

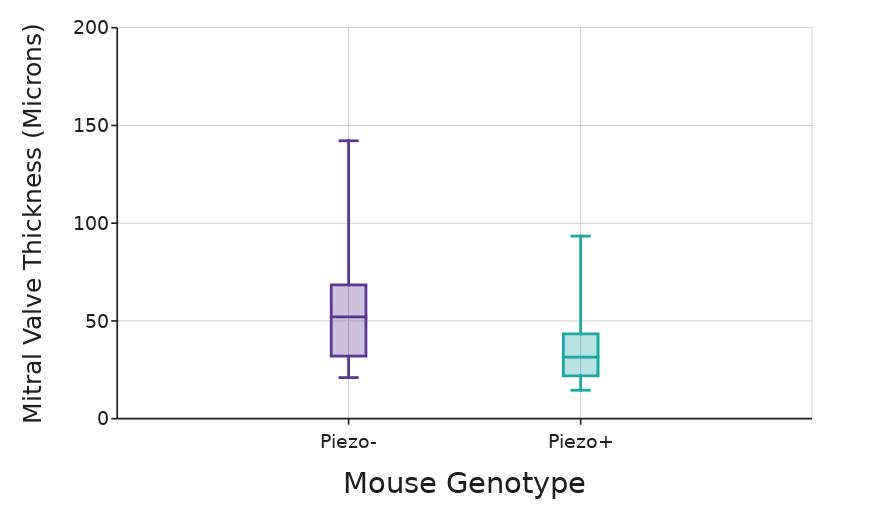

A statistically significant difference in mitral valve thickness was initially observed between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice (p < .05; Mann-Whitney U; data not shown) However, this difference was entirely due to the inclusion of the Piezomouse that was significantly older, at 128 days, than the other mice, which had ages ranging from 44 to 83 days at collection. This mouse had a significantly thicker mitral valve than all other mice except for the one mouse 82 days old, regardless of genotype (p< 05; ANOVA post-hoc Tukey's range test, Figure 7) Accordingly, this mouse was removed from further analysis. After exclusion of this mouse, there was no significant difference in mitral valve thickness between Piezo+ and Piezo- mice (p = 0 20; Mann-Whitney U; Figure 8)

Discussion

We found no statistically significant differences in any of the scoring of the in vivo ankle growth, the visibly arthritic qualities of the ankles and feet or the stained ankle sections scored for synovial inflammation, bone erosion, cartilage erosion, and osteoclast presence between the Piezo+ and Piezo- mice. Based on our results we can not conclude that PIEZO1 has any impact on the development or course of arthritis in mice given a K/Bg 7 serum transfer Our data and results also indicate that, as expected, the removal of Piezo1 has no effect on the morphology of the mitral valve in mice.

Limitations

We are cautious about concluding that there is no impact, due to some limitations of this preliminary investigation One limitation is that the sample size of mice we used was relatively small: only 10 mice, five Piezo+, and five Piezo-. There was also a wide range of ages that caused some variability in the data One outlier was removed due to its older age, however, there was still a lot of remaining variability in the data Though this variability didn’t appear connected to their ages, there were Piezo+ and Piezo- mice that were not fully age-matched at the onset of the experiment

Figure 7. Thickness of the mitral valves (µm) at each age. Box whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) Dots show individual scores for 44 days old mice: mouse B, (n=3); for 54 days old mice: mouse H, (n=3) and mouse I, (n=3); for 61 days old mice: mouse E, (n=6); for 82 days old mice: mouse A, (n=5); for 83 days old mice: mouse C, (n=6), mouse D, (n=6), and mouse F, (n=6); for 128 days old mice: mouse G, (n=6) Figure by authors

Figure 8. Thicknesses of the mitral valves (µm) compared to the mouse genotype. Box whiskers plot shows the median value (line), interquartile range (box), and the extent of the data (whiskers above and below at min/max data points) Dots show individual scores for Piezo+ mice: mouse A, (n=5), mouse B, (n=3), mouse C, (n=6), and mouse D, (n=6); and Piezo- mice: mouse E, (n = 6), mouse F, (n=6), mouse G, (n=6), mouse H, (n=3), and mouse I, (n=3) Figure by authors

It’s also possible that PIEZO1 may play a different role in human RA or in mouse arthritis not induced by K/Bg.7 serum.

Future work

Additional research will need to be done before PEIZO1 can be conclusively excluded as a possible factor Future work should include more

mice in experiments and age-matching within samples. Other models could include collagen-induced polyarthritis (CIA) and the IL-1RA knockout model In the CIA model, arthritis develops in multiple joints after immunization with cartilage-specific collagen II (Caplazi & Diehl, 2014). This produces immunoreactivity to type II collagen, which is also observed in human rheumatoid arthritis Additionally, it shares other commonalities with human RA, including the development of rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) that circle the body during the disease. Its similarity in mechanisms to human RA, makes it an ideal model for further defining the role of Piezo1 Another viable option is the IL-1RA knockout (KO) model which presents very similarly to human RA. IL-1RA knockout mice also have rheumatoid factor, develop autoantibodies to type II collagen, and are T-cell dependent, like in human arthritis (Caplazi & Diehl, 2014) Its T cell dependency in particular makes it an interesting model for further studying Piezo1 because it involves the adaptive immune system similar to human RA Since our data did not indicate that PIEZO1 is involved in worsening rheumatoid arthritis in the K/B g7 serum-transfer model, this research may narrow down potential targets for stopping the devastating effects of this disease. However, completely ruling out the role of pressure-sensing proteins would necessitate further research into their involvement in rheumatoid arthritis, and further defining the role of PIEZO1 within this and other mouse models.

Beyond PIEZO1, other pressure-sensing targets must be studied to determine any potential roles in worsening inflammation. One of these targets could include Piezo2, a mechanosensitive ion channel, which has been associated with other inflammatory diseases (Liu et al , 2022) Due to the observed correlations between pressure-sensing proteins and inflammation, further research must be done to understand these interactions fully.

Graham Bailey and Samantha Dvorak

Conclusions

Despite previous observations of pressuresensing proteins having a role in inflammatory diseases, there was no observable connection in our data Since PIEZO1 did not appear to be involved in the development of rheumatoid arthritis, it’s possible that PIEZO1 does not play a crucial role in developing the disease. This could be used to rule out pathways and narrow down effective targets for stopping the devastating effects of rheumatoid arthritis

This research is a first step towards ruling out one potential pathway for the development of rheumatoid arthritis Furthermore, the observation that Piezo1’s removal did not appear to impact the mitral valve in this model will allow for greater confidence in its removal as a way to evaluate PIEZO1’s potential implications in other related autoimmune diseases, like rheumatic heart disease

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Kati Kragtorp for guiding us through science research and creating this paper. We would also like to thank Dr. Bryce Binstadt for the opportunity to work in his lab and for his support throughout our research Additionally, we would like to thank Jenn Auger, Alyssa Peck, and Charles Rolls for their time spent teaching us these laboratory techniques and their assistance throughout our time in the lab

References

Autoimmune Disease An overview | ScienceDirect Topics (n d ) Retrieved July 21, 2024, from https://www sciencedirect com/topics/immunology-and-microbiolo gy/autoimmune-disease#: :text=Autoimmune%20diseases%20are %20a%20set,high%20financial%20costs%20%5B1%5D

Autoimmune disorders found to affect around one in ten people | University of Oxford (2023, May 6) https://www ox ac uk/news/2023-05-06-autoimmune-disorders-fou nd-affect-around-one-ten-people

Breed, E R , & Binstadt, B A (2015) Autoimmune valvular carditis Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 15(1), 491 https://doi org/10 1007/s11882-014-0491-z

Caplazi, P , & Diehl, L (2014) Histopathology in Mouse Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis In S J Potts, D A Eberhard, & K A Wharton, (Eds ), Molecular Histopathology and Tissue Biomarkers

in Drug and Diagnostic Development (pp 65–78) Springer New York https://doi org/10 1007/7653 2014 20

Chen, M , Lam, B K , Kanaoka, Y , Nigrovic, P A , Audoly, L P , Austen, K F , & Lee, D M (2006) Neutrophil-derived leukotriene B4 is required for inflammatory arthritis The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 203(4), 837–842 https://doi org/10 1084/jem 20052371

Galvin, J E , Hemric, M E , Ward, K , & Cunningham, M W (2000) Cytotoxic mAb from rheumatic carditis recognizes heart valves and laminin The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 106(2), 217–224 https://doi org/10 1172/JCI7132

Gorton, D , Blyth, S , Gorton, J G , Govan, B , & Ketheesan, N (2010) An alternative technique for the induction of autoimmune valvulitis in a rat model of rheumatic heart disease Journal of Immunological Methods, 355(1–2), 80–85 https://doi org/10 1016/j jim 2010 02 013

Hayer, S , Vervoordeldonk, M J , Denis, M C , Armaka, M , Hoffmann, M , Bäcklund, J , Nandakumar, K S , Niederreiter, B , Geka, C , Fischer, A , Woodworth, N , Blüml, S , Kollias, G , Holmdahl, R , Apparailly, F , & Koenders, M I (2021) “SMASH” recommendations for standardised microscopic arthritis scoring of histological sections from inflammatory arthritis animal models Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 80(6), 714–726 https://doi org/10 1136/annrheumdis-2020-219247

Liu, H , Hu, J , Zheng, Q , Feng, X , Zhan, F , Wang, X , Xu, G , & Hua, F (2022) Piezo1 Channels as Force Sensors in Mechanical Force-Related Chronic Inflammation Frontiers in Immunology, 13, 816149 https://doi org/10 3389/fimmu 2022 816149

Marijon, E , Mirabel, M , Celermajer, D S , & Jouven, X (2012) Rheumatic heart disease Lancet (London, England), 379(9819), 953–964 https://doi org/10 1016/S0140-6736(11)61171-9

Monach, P , Hattori, K , Huang, H , Hyatt, E , Morse, J , Nguyen, L , Ortiz-Lopez, A , Wu, H -J , Mathis, D , & Benoist, C (2007) The K/BxN mouse model of inflammatory arthritis: Theory and practice Methods in Molecular Medicine, 136, 269–282 https://doi org/10 1007/978-1-59745-402-5 20

Osinski, V , Yellamilli, A , Firulyova, M M , Zhang, M J , Peck, A L , Auger, J L , Faragher, J L , Marath, A , Voeller, R K , O’Connell, T D , Zaitsev, K , & Binstadt, B A (2024) Profibrotic VEGFR3-Dependent Lymphatic Vessel Growth in Autoimmune Valvular Carditis Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 44(4), 807–821 https://doi org/10 1161/ATVBAHA 123 320326

Raizada, V , Williams, R C , Chopra, P , Gopinath, N , Prakash, K , Sharma, K B , Cherian, K M , Panday, S , Arora, R , Nigam, M , Zabriskie, J B , & Husby, G (1983) Tissue distribution of lymphocytes in rheumatic heart valves as defined by monoclonal anti-T cell Antibodies The American Journal of Medicine, 74(1), 90–96 https://doi org/10 1016/0002-9343(83)91124-5

Smolen, J. S., Aletaha, D., Barton, A., Burmester, G. R., Emery, P., Firestein, G S , Kavanaugh, A , McInnes, I B , Solomon, D H , Strand, V., & Yamamoto, K. (2018). Rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 4(1), 1–23 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.1

Xie, L , Wang, X , Ma, Y , Ma, H , Shen, J , Chen, J , Wang, Y , Su, S , Chen, K , Xu, L , Xie, Y , & Xiang, M (2023) Piezo1

(Piezo-Type Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Component 1)-Mediated Mechanosensation in Macrophages Impairs Perfusion Recovery After Hindlimb Ischemia in Mice Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 43(4), 504–518 https://doi org/10 1161/ATVBAHA 122 318625

Abigail Endres and Selena Qiao

Tur f Trouble:

Does the DEET in bug repellent really kill grass? Year II

Abigail Endres, Selena Qiao

Introduction

DEET, or N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide, is a chemical that is typically the active ingredient in most bug spray repellents DEET is a neurotoxin believed to affect the olfactory receptors in insects and vertebrates, inhibiting an insect’s ability to locate humans (Martinez et al., 2016). DEET is extremely effective as an insect repellent; around one-third of the U S population annually uses DEET to prevent mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease (US EPA, 2013a).

DEET was originally developed by the U S Army in 1957 and registered for public use in 1964 (US EPA, 2013a). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reviews each pesticide at least every 15 years to ensure it is generally safe for public use (US EPA, 2013b) DEET was reviewed in 1998 and again in 2014 The EPA found that DEET is safe for humans to use and is slightly toxic to birds and fish (Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) DEET, 1998). However, this report did not examine the potential effects on the environment, stating that “environmental risk assessments are not conducted for pesticides with exclusively indoor use patterns” (Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) DEET, 1998).

Anecdotal evidence suggests that bug sprays containing DEET damage grass (DEET Is Lethal to Grass; Take Care When Using, 2016; “Is DEET Really All That Bad?,” 2019; Graedon & Graedon, 2007) In particular, this is a problem for golf courses Certain areas of golf courses, such as tee boxes and greens, are more sensitive and susceptible to damage due to short mowing heights. Repairing damage caused by bug spray is costly, not only in money but also in water and other natural resources Although there are no

rigorous peer-reviewed studies on the topic, there are a few informal studies and records of observations posted online addressing the subject In a short article from Michigan State, a professor states how they have observed that bug sprays kill grass (Frank, 2013) A brief study from Kansas State examined the impact of different commercial bug sprays on perennial ryegrass, with four replicants for each treatment group The study found that the bug sprays with a higher DEET concentration caused greater grass damage (Hoyle, 2017). A short report from Iowa State University tested the impact of different commercial chemical sprays on grass commonly used in golf greenways A researcher sprayed patches of bentgrass with bug sprays containing DEET and bug sprays without DEET Each application was repeated on three different patches, approximately a week apart. The researchers concluded that bug sprays containing DEET caused immediate grass damage that took upwards of three weeks to recover The patches sprayed with non-DEET bug spray showed no signs of damage (Christians, 2015). While these observations and findings are interesting, the research was not conducted very rigorously. Furthermore, while looking into the toxicity of DEET on plants, we were unable to find any other scientific reports on the subject

To our knowledge, no peer-reviewed study exists that investigates the toxicity of DEET to any plants We did find two papers that examined the environmental toxicity of DEET. A study reported that DEET that enters the environment through runoff poses a low environmental risk (Weeks et al , 2012) A study examined the potential toxicological effects of DEET in algae in environments with low water circulation They concluded that oxygen flux was significantly i nhibited when exposed to DEET, providing preliminary evidence that details the toxic effects of DEET (Martinez et al , 2016)

In Year One of this project (2023/2024), one of the authors (Qiao) tested how commercial insect repellents containing DEET impacted different types of grass This study used four treatment groups: 7% DEET, 25% DEET, a natural alternative containing lemongrass oil, and a control where no treatment was sprayed. The study tested perennial ryegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, and creeping bentgrass, each with six pots for each treatment group Perennial ryegrass and creeping bentgrass were tested because they are commonly used on golf courses, and Kentucky bluegrass is a common lawn grass in the northern United States (Bauer, n.d.). Qiao found that DEET affected all three types of grass in a dose-dependent manner, with the bug spray with 25% DEET damaging the grass the fastest However, the grass treated with 7% DEET bug spray eventually reached the same level of damage as the grass treated with the bug spray containing 25% DEET

Safety Data sheets for the 7% and 25% DEET insect repellent used in the first year of this study reported 60-100% and 30-60% respectively of the carrier ethanol in each solution as the only other major ingredient (OFF! Deep Woods Insect Repellent VII, Long Lasting Protection, Pump Spray, 2021; OFF! FamilyCare Insect Repellent IV, Unscented with Aloe Vera, Pump Spray, 2015) The 25% DEET bug spray had a lower concentration of ethanol, suggesting that it was the DEET and not the ethanol that was damaging the grass. However, this hypothesis was not tested in year one. Another limitation of the original study was that the grass damage was analyzed using a qualitative ranking system, meaning that the analysis could have been biased and subject to human error. Furthermore, the method of spraying wasn’t standardized, leading to inconsistent coverage of bug spray. Finally, the photos were taken with an iPhone camera, which automatically adjusted the color and contrast of the photo, leading to inconsistent lighting.

This year, our goals were to identify whether DEET or ethanol damaged the grass, if grass treated with DEET would recover, if the addition of DEET directly to the soil impacted the health

of the grass, and if DEET exposure to grass in an outdoor environment would impact the level of grass damage Lastly, we investigated DEET’s mechanism of toxicity

Materials and Methods

Planting and treatment standardization

One issue encountered in Year I of this study was that the unevenness of the soil during planting caused the grass in the pots to grow in a non-uniform manner, such that the grass was distributed unevenly

To address this problem, we designed a soil flattening tool (Figure 1) using the SolidWorks (Dassault Systèmes) computer-aided design (CAD) software We then 3D printed the tool on a Prusa i3 MK3S+ 3D Printer After the soil was added to the pot, the soil flattening tool was moved in a light circular motion above the soil. This act ensured that there was a firm and flat surface on which the seeds could be placed

Another issue in Year I was standardizing the angle and distance of the spray bottle to the grass To address this issue, we designed and 3D-printed a tool for a uniform method of spraying grass pots The two components of the tool were a pot holder for the grass and a rod that guided the user to hold the spray bottle at the correct angle and height. The pot holder was later used as the circular spraying template during the outdoor turfgrass plot experiments (Figure 1)

Analysis of images for indoor plants

We used a Canon EOS Rebel T7i Digital SLR camera to take photos of the grass. The pots of grass were moved to a room with consistent lighting and no windows The camera was positioned on a tripod at an overhead angle so that the images were taken from the top. A lamp was placed near the set-up to improve the lighting. The pots of grass were placed under the camera in a marked circle one by one so that the position of the pots in the image remained constant

The images were analyzed in ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). An ImageJ macro for extracting information about color in images was used to measure the area of the healthy grass in each picture (Strock, 2021) Since the damaged grass was a distinct yellow compared to the normal green color, we set parameters for color thresholds that would select and create a mask for the green portions of the grass Analyzing the mask generated the area of the healthy grass in pixels Some experimentation was done to determine the best parameters for the color threshold since some thresholds would incorrectly mask the background instead of the grass The HSB color space was used along with the Minimum thresholding method, which produced the best mask coverage results

Treatment of outdoor plots

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera), and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) plots were provided by the University of Minnesota Turfgrass Research Center, and two 1 by 1-meter plots were used for each type of grass. Within each plot of grass, there were four treatment groups with four replicants each, which totaled 16 treatments within each plot A circular spraying template was used to treat sections of grass at the 20, 40, 60, and 80 cm marks within the 1 x 1 meter plot At each spot, the grass was sprayed from four angles around the circular treatment area (0, 90, 180, and 270 degrees) with either 60% ethanol, 2 5% DEET, 15% DEET, or 25% DEET

Collection and analysis of images for outdoor plots

The outdoor plots were photographed from the top at an overhead angle One image was taken per plot, so there were two pictures per grass type. The benchmark used to standardize the photos were four flags that marked the corners of each plot The images were analyzed in ImageJ using the same macro template from the indoor experiments Because the plots were outdoors, the lighting in each picture varied based on the weather. Thus, we adjusted the color parameters for each image according to its lighting conditions Each photo of a single plot contained

Abigail Endres and Selena Qiao

sixteen treatments, each image was cropped into sixteen 400x400 pixel photos of the individual treatments, with the circle of treatment positioned in the center of each photo The damaged treatment circles were yellow while the background of healthy grass was green, so the new thresholds selected and masked the yellow grass. The area of the mask was then recorded for every cropped image

Sample collection and preparation for metabolomics analysis

Twelve pots of grass were grown in the standard setup at our school Once the grass had grown for three weeks, we transferred the tray of grass to a controlled growth chamber where it was stabilized for two weeks. The grass remained in the growth chamber throughout sampling. Six pots of grass were treated with ethanol and the other six were treated with 15% DEET

Samples were collected immediately after treatment and for five days after treatment In a line across the pot, we plucked 40 blades of grass, and then, perpendicular to that, we plucked another 40 blades of grass. If the grass was longer than 2.5 cm, we reduced the number of blades we selected to collect approximately 200 cm of grass The blades of grass were then placed into a test tube, which was then placed on dry ice

To prepare for liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis, the tubes were transported out of the freezer in a cooler box with dry ice One tungsten bead was then placed within each sample tube to help beat the plant tissue in the tube. A stock solution of methanol with 10% formic acid was then added to each tube based on the mass of the grass sample Each sample tube was then secured into the Geno/Grinder The tubes ran through the Geno/Grinder for five minutes at 150 rpm. The tubes were then placed into the microcentrifuge for 5 minutes at 1400 rpm

LC-MS methods

A trained researcher then performed LC-MS on the samples to create a map of how the metabolome of the grass changes after DEET

exposure and supplied the following information about these methods (K. Freund, personal communication): Metabolomic profiles were obtained using C18 reversed-phase ultraperformance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–hybrid quadrupole –orbitrap mass spectrometer (Ultimate® 3000 HPLC, Q Exactive™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an autosampler and with a sample vial block maintained at 4 °C Chromatographic separations were carried out on an Acquity reversed-phase C18 HSS T3 1.8 µm particle size, 2.1 mm × 100 mm column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with column temperature 40 °C, flow rate 0 400 mL/min, and 1 µL injected A 16 min gradient using mobile phases A: 0 1% formic acid in water and B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile was run according to the following gradient elution profile: initial 2% B, 0.5 min 2% B, 15 min 98% B, 0 5 min 2% B The MS conditions used were full scan mass range 125-1800 m/z, resolution 70 000, desolvation temperature 350 °C, spray voltage 3800 V, auxiliary gas flow rate 20, sheath gas flow rate 50, sweep gas flow rate 1, S-Lens RF level 50, and auxiliary gas heater temperature 300 °C Xcalibur™ software version 2 1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for data collection and chromatogram visualization. Sample analysis order was randomized across the entire sample set

Data processing and analysis

A trained researcher also performed the analysis of LC-MS results and supplied the following information about these methods (K. Freund, personal communication): The ProteoWizard tool MSconvert (Chambers et al , 2012) was used to convert raw files to mzML format for positive and negative ionization data MZmine 2 version 2.53 (Pluskal et al., 2010) was used to process chromatographic data through mass detection, chromatogram building, chromatogram deconvolution, and deisotoping steps Alignment of samples was attained through the RANSAC aligner tool, and gap filling using Same RT and m/z range gap filler algorithm was

performed to detect missing peaks. Non-peak shape features were removed after visual inspection and 1692 unique positive mode and 838 unique negative mode features were detected based on the combination of distinct m/z and retention time. Positive and negative datasets were exported to .csv file format and combined for analysis in RStudio (Posit Team, 2023) Data were log2-transformed before multivariate statistical analyses and were visualized using principal component analysis (PCA) using the R package ropls (Thévenot et al., 2015).

Results

Determination of Dose-Response of Grass to DEET Exposure

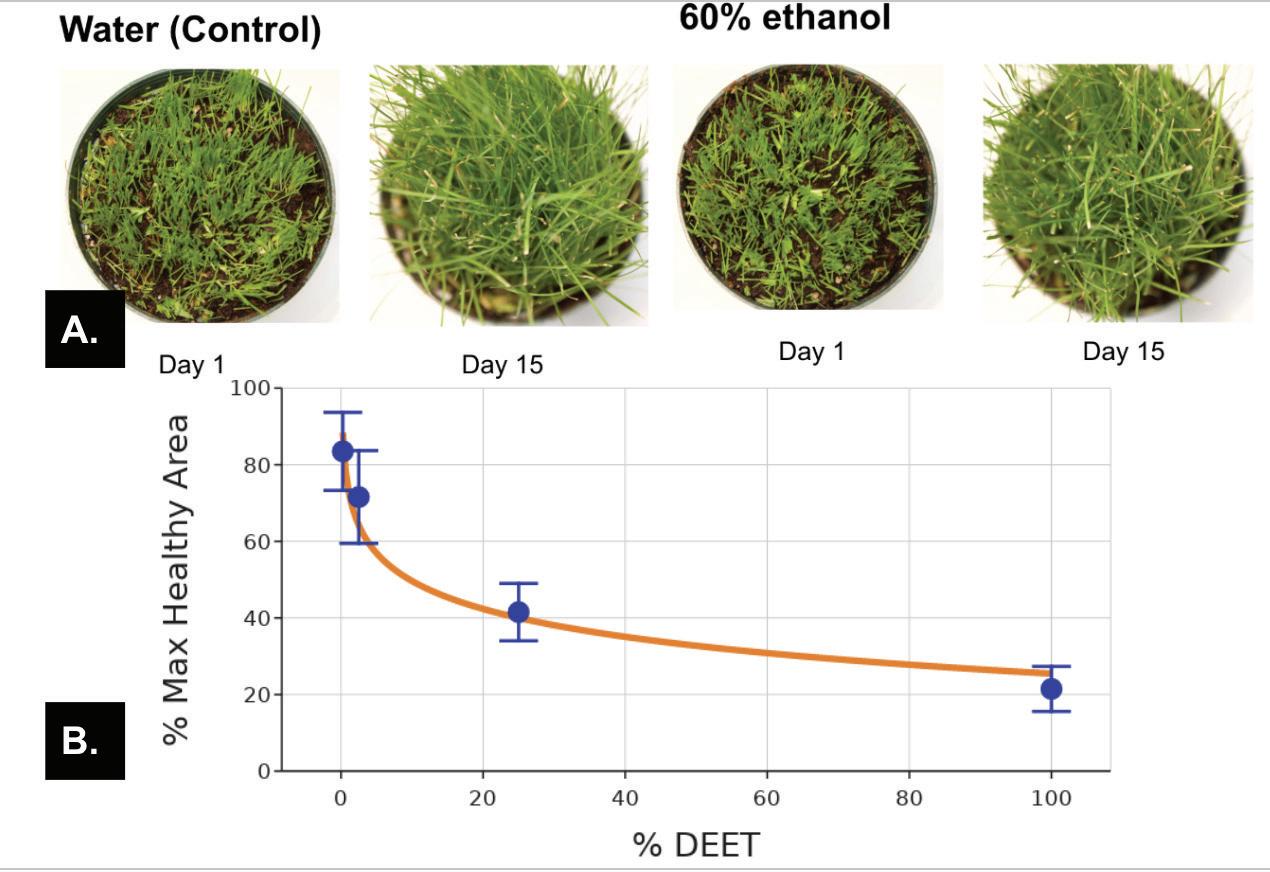

We initially conducted a pilot experiment with 10 pots of silver sport perennial ryegrass that had been cut to 2 cm One pot was sprayed with DI water, one was exposed to 100% DEET, two were exposed to 60% ethanol, two were exposed to 60% ethanol with 5% DEET, two were exposed to 60% ethanol with 15% DEET, and two were exposed to 60% ethanol with 25% DEET Images of the grass were captured and analyzed for damage All the grass sprayed with DEET in this pilot experiment died within three days of treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A) Representative images of grass treated with water and 60% ethanol on day 1 (immediately after treatment) and 15 days after treatment B) Percent of the maximum possible healthy (green) area of grass measured in images with different levels of DEET treatment one day after treatment The graph displays the mean and standard deviation of the percentage of healthy grass in pots treated with

0.25% DEET, 2.5% DEET, 25% DEET, and 100% DEET, one day after treatment All DEET solutions other than 100% DEET also contained 60% ethanol The percentage of healthy grass was calculated by dividing the area of the green grass in the DEET treatment groups over the “maximum healthy area”, or the average area of healthy grass in the pots treated with 60% ethanol n = 4 for all treatment groups Figure by authors

Based on these results, we decided to use lower concentrations of DEET to establish the lowest concentration of DEET that would damage the grass We kept the 100% DEET and 60% ethanol with 25% DEET solutions and replaced our other DEET treatments with 60% ethanol with 2.5% DEET and 60% ethanol with 0.25% DEET. The water-only control and the 60% ethanol solution were kept for this full dose-response experiment We planted 24 pots of perennial ryegrass so that there were 4 replicants of all the 6 treatments that were used in this experiment. There was no significant difference in damage between the grass exposed to the 60% ethanol solution and the grass exposed to water (data not shown) Accordingly, 60% ethanol was used as a control for subsequent data analysis

Within one day of exposure, pots treated with higher levels of DEET showed increased levels of damage, indicating that DEET damaged grass in a dose-dependent relationship (Figure 1) Based on this data, we calculated an effective dose to damage 50% of the grass (ED50) of 9 7% DEET

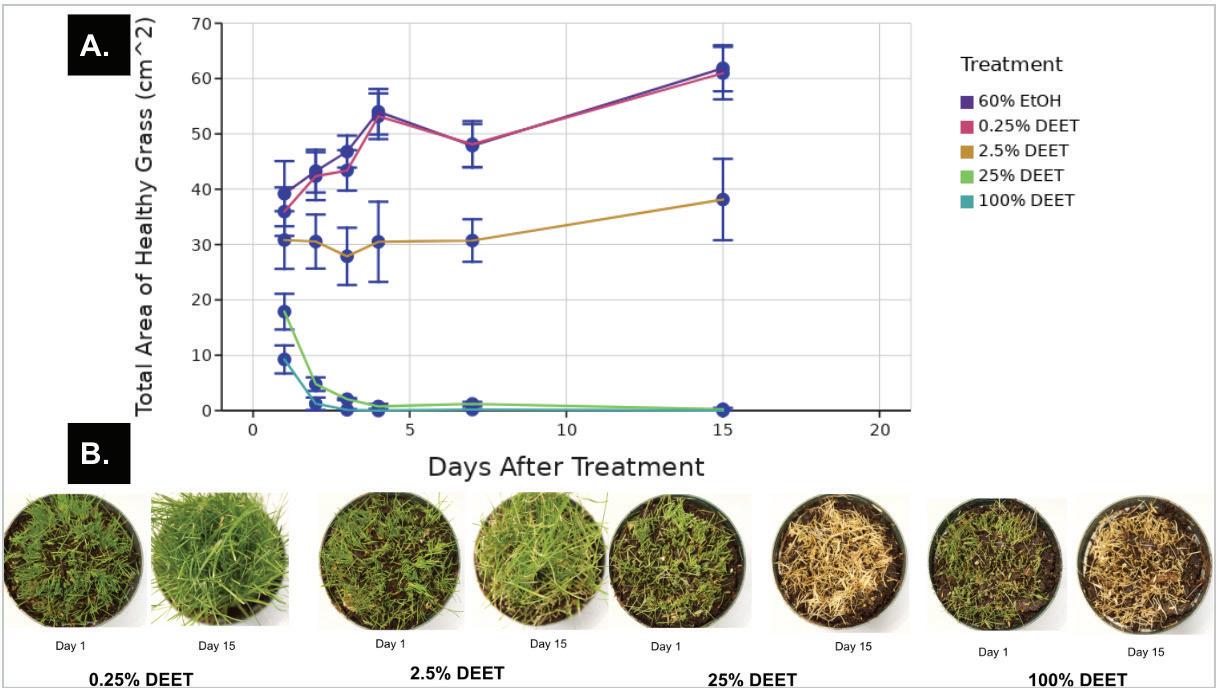

The area of healthy (green) grass over 15 days of exposure was not significantly different between pots treated with 60% ethanol and pots treated with 0 25% DEET (Figure 2, ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc; p = 0 99) This shows that 0 25% DEET does not have any visible effect on grass health. Pots treated with 2.5% DEET displayed a slower increase in green area over 15 days after treatment but had an overall increase in green over the course of the experiment and a majority of the grass was a light green by day 15 (Figure 2) By day 15, pots treated with 25% DEET and 100% DEET had no living grass (Figure 2). Pots treated with 100% DEET solution had no healthy grass by day 3, while 25% DEET-treated

Abigail Endres and Selena Qiao

grass reached that point by day 4 after treatment (Figure 2). We continued to follow the pots from the pilot and full experiments for several weeks after exposure No new growth was observed in pots treated with 5% DEET or higher, even up to 30 days after exposure (data not shown). In further trials, DEET treatment was immediately followed by either wiping the grass or spraying it with water in an attempt to reduce the damage, however, these interventions had no measurable effect on the level of grass damage (data not shown).

Figure 2. A) Total area of healthy (green) grass (cm^2) measured in images over 15 days after treatment The graph displays the mean and standard deviation of the percentage of healthy grass in pots treated with 60% ethanol, 0 25% DEET, 2 5% DEET, 25% DEET, and 100% DEET, one day after treatment All DEET solutions other than 100% DEET also contained 60% ethanol n = 4 pots for all treatment groups. B) Representative images of grass treated with 0 25% DEET, 2 5% DEET, 25% DEET, and 100% DEET group, 1 day after treatment and 15 days after treatment Figure by authors

Measurement of the Impact of Different DEET Exposure Methods

We experimented with alternate methods of DEET exposure to test if indirect exposure through the soil would affect grass health The grass was planted with a gap in the middle so that there was a circle of soil that was surrounded by grass. Using a pipette, the soil in the middle was exposed to different concentrations of DEET solutions Pictures of the grass were taken daily over the span of a week There was no significant difference between the green area in the grass treated with water and the grass treated with ethanol (data

not shown). Damage was confined to the area directly surrounding the treated soil (data not shown)

The area of healthy (green) grass was significantly different between the 60% ethanol control group and the 100% DEET treatment group on day 6 (data not shown) While the other treatment groups showed an initial decrease in the area of healthy grass for the first three days after treatment, this difference was not significant, and the area of healthy grass reached the same point as the control group (data not shown)

DEET Exposure in an Outdoor Environment

To understand the impact of DEET exposure on outdoor grass, turfgrass plots were provided by the Watkins Labs at the University of Minnesota to conduct an outdoor version of the ethanol and DEET experiment Three species of grass (perennial ryegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, and creeping bentgrass) were treated with solutions of 25% DEET and 60% ethanol, 15% DEET and 60% ethanol, 2.5% DEET and 60% ethanol, and 60% ethanol The purpose of this experiment was to confirm the existence of a dosedependent relationship between grass damage and DEET concentrations outdoors Since the 0.25% DEET treatment group had no visible effect on grass health and the 100% DEET treatment group caused similar amounts of damage compared to the 25% DEET treatment group, the 0 25% and 100% concentrations were not included. Instead, 15% DEET was used as an intermediate concentration between 2.5% and 25% DEET.

Pictures of the grass were taken daily over the span of a week. Damage was observed in treated areas within one day of treatment in the creeping bentgrass (data not shown), perennial ryegrass, and Kentucky bluegrass (data not shown) In the creeping bentgrass plots, compared to the 60% ethanol control, there was a significant increase in the area of damaged bentgrass exposed to 25% DEET, 15% DEET, and 2.5% DEET on days 1 through 7 (data not shown ), though there appeared to be some recovery in the grass

exposed to 15% DEET by day 7 (Figure 11). A similar pattern was observed in perennial ryegrass and Kentucky bluegrass (data not shown) A small amount of damage was noted in the 60% ethanol control sections at the spots where the template tool used during treatments was touching the bentgrass, but not in the middle area where the ethanol was actually sprayed (Figure 10) Although efforts were made to thoroughly clean the template tool between treatments, this damage is more consistent with residual DEET on the template tool, rather than damage resulting from the ethanol. We found that the outdoor grass was able to recover at a faster rate than the indoor grass This could have been a result of the weather or watering schedule, which may have lessened DEET’s effect on the grass. Additionally, differences in the uncontrolled lighting outdoors increased the potential inconsistency in image analysis.

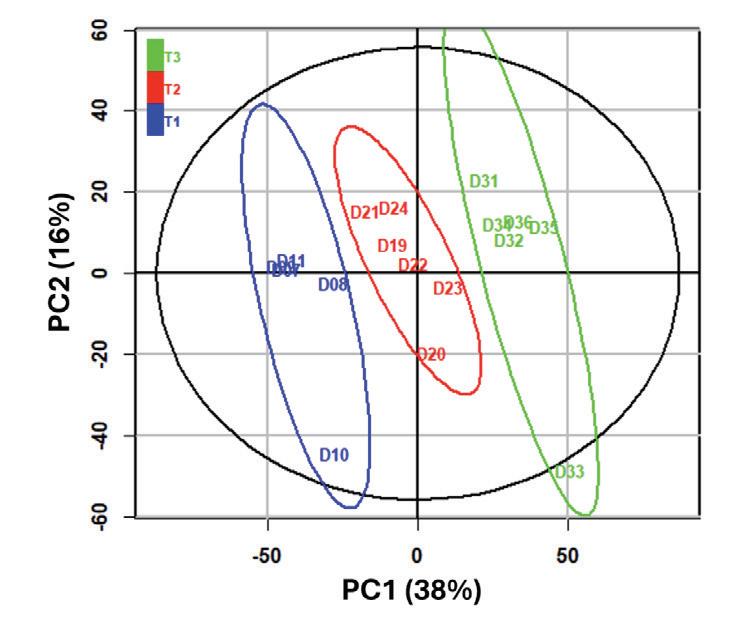

Assessment of Metabolomic Differences of Grass Exposed to DEET

Using equipment provided by the University of Minnesota, we investigated how DEET exposure changes the metabolome of grass, which in turn could help determine how DEET damages the grass. Pots of grass were treated with either 60% ethanol or 15% DEET using our standard procedure The 15% DEET treatment group was used to ensure that gradual damage occurred over a period of four days Samples were collected prior to treatment, 1 hour after treatment, and one, two, three, and four days after treatment, then processed for LC-MS analysis following standard procedures An untargeted metabolomics approach was used, involving simultaneous measurement and relative quantification of all known and unknown metabolites. Within each sample, all detected ions were scaled to the most abundant ion to quantify phytochemical content Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the effect of treatment on the metabolic profile of the grass. PCA is a common method used to investigate patterns and correlations in complex metabolomic data sets There was no difference in the metabolomic profiles of samples prior to

treatment with either 60% ethanol or DEET (data not shown).

Major differences were apparent in the metabolomic profiles of grass exposed to DEET as compared to 60% ethanol as early as 1 hour after exposure (Figure 3), and the metabolic profiles of grass exposed to DEET, but not 60% ethanol (data not shown), displayed significant shifts each day from day zero to day one (data not shown), with less separation in metabolic profiles on days two through four (data not shown), at which times the DEET-treated grass appeared to have mostly died (data not shown).

Figure 3. Samples prior to treatment with 15% DEET (blue), 1 hour after treatment (red) and 1 day after treatment (green). The percent of variation explained by each principal component is shown on each axis Figure by K Freund

Discussion

We determined that DEET kills grass in a dose-dependent manner in both a controlled, indoor environment and on three different species of grass in an outdoor environment We found the grass that died from DEET exposure did not recover up to 30 days after exposure. We demonstrated that grass next to DEET-exposed soil caused seemingly identical damage to grass sprayed with DEET This shows that the mechanism of DEET toxicity does not require direct application to the blade's surface. This experiment suggests that DEET is absorbed by the roots, causing damage to grass in the surrounding area Furthermore, an untargeted metabolomics analysis of treated grass revealed

Abigail Endres and Selena Qiao

significant differences in the metabolomes of treated grass within 1 hour of DEET application, indicating a rapid toxic mechanism In addition, the analysis revealed significant differences between the metabolomes of the time-sampled grass, indicating that DEET affects grass in a time-dependent manner. It can be concluded that DEET toxicity is caused by a change in the grass metabolome; however, identifying the specific metabolomic pathway responsible for the change requires further analysis

Future investigations will examine the toxic mechanism behind DEET’s effect on grass By continuing metabolomics analysis, we can get a deeper look into what specific features in the grass are changing after being exposed to DEET. The previous year, we conducted a time-lapse experiment using a camera to film a pot of grass after it had been treated with DEET Over the course of 24 hours, the blades of grass seemed to shrink in width and shrivel slightly, suggesting that the grass was losing water as a result of the DEET treatment. To test this hypothesis, we plan to use a fluorescence microscope to capture changes in stomata stained with DAPI A previous study conducted on algae indicated that photosynthesizing organisms might be more sensitive to DEET than non-photosynthetic microorganisms (Martinez et al., 2016). Thus, additional research should expand the scope to plants other than grass, as they are also possibly susceptible to DEET exposure Overall, this is a novel finding that opens up new, unexplored questions in the field of plant toxicology and indicates that, though the use of DEET-based bug sprays is necessary for protection from disease-causing insects, care should be taken when applying it to avoid contacting plants in the area.

References

Bauer, S (n d ) Minnesota Home Lawns University of Minnesota Extension Turfgrass Science https://turf umn edu/sites/turf umn edu/files/files/media/turfgrass i nfographic 1 pdf

Chambers, M C , Maclean, B , Burke, R , Amodei, D , Ruderman, D L , Neumann, S , Gatto, L , Fischer, B , Pratt, B , Egertson, J , Hoff, K , Kessner, D , Tasman, N , Shulman, N , Frewen, B , Baker, T A , Brusniak, M -Y , Paulse, C , Creasy, D , Mallick, P

(2012) A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics Nature Biotechnology, 30(10), 918–920

https://doi org/10 1038/nbt 2377

Christians, N (2015, August 25) Mosquito Spray Can Kill Grass Turfgrass

https://www extension iastate edu/turfgrass/blog/dr-nick-christians/ mosquito-spray-can-kill-grass

Deep Woods OFF killed the grass- Yikes! (2011, July 9) https://windsorpeak com/vbulletin/showthread php?403732-DeepWoods-OFF-killed-the-grass-Yikes!&p=3193658

DEET is lethal to grass; take care when using (2016, July 28)

Longview News-Journal

https://www news-journal com/features/atplay/deet-is-lethal-to-gra ss-take-care-when-using/article 7cba0999-c391-5f0d-b291-c20a42 cf5352 html

Frank, K (2013, May 30) Mosquito repellent can damage turf MSU Extension

https://www canr msu edu/news/mosquito repellent can damage t urf

Graedon, J , & Graedon, T (2007, August 28) Dead grass raises question on DEET safety | The Spokesman-Review https://www spokesman com/stories/2007/aug/28/dead-grass-raises -question-on-deet-safety/

Hoyle, J (2017, June 29) The Effect of Human Insect Repellents on Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Growth and Recovery | K-State Turf and Landscape Blog

https://blogs k-state edu/turf/the-effect-of-human-insect-repellentson-perennial-ryegrass-lolium-perenne-growth-and-recovery/

Is DEET Really All That Bad? (2019, August 16) No Mozzie https://nomozzie co uk/is-deet-really-all-that-bad/

Martinez, E , Vélez, S M , Mayo, M , & Sastre, M P (2016)

Acute toxicity assessment of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) on the oxygen flux of the dinoflagellate Gymnodinium instriatum

Ecotoxicology, 25(1), 248–252 https://doi org/10 1007/s10646-015-1564-z

OFF! Deep Woods Insect Repellent VII, Long Lasting Protection, Pump Spray (2021, August 6) Consumer Protection Information

Database

https://www whatsinproducts com/types/type detail/1/24071/stand ard/19-001-855

OFF! FamilyCare Insect Repellent IV, Unscented with Aloe Vera, Pump Spray (2015, February 23) Consumer Protection Information Database

https://www whatsinproducts com/types/type detail/1/16560/stand ard/p%20class=%22p1%22%3Espan%20style=%22color:

Pluskal, T , Castillo, S , Villar-Briones, A , & Orešič, M (2010)

MZmine 2: Modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1), 395 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-395

Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) DEET (1998) U S EPA.

https://www3 epa gov/pesticides/chem search/reg actions/reregistr ation/red PC-080301 1-Apr-98.pdf

Schneider, C A , Rasband, W S , & Eliceiri, K W (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis Nature Methods, 9(7), 671–675 https://doi org/10 1038/nmeth 2089

Strock, C (2021) Protocol for extracting basic color metrics from Images in ImageJ/Fiji Zenodo https://doi org/10 5281/ZENODO 5595203

Thévenot, E A , Roux, A , Xu, Y , Ezan, E , & Junot, C (2015) Analysis of the Human Adult Urinary Metabolome Variations with Age, Body Mass Index, and Gender by Implementing a Comprehensive Workflow for Univariate and OPLS Statistical Analyses Journal of Proteome Research, 14(8), 3322–3335 https://doi org/10 1021/acs jproteome 5b00354

US EPA, O (2013a, July 15) DEET [Overviews and Factsheets] https://www epa gov/insect-repellents/deet

US EPA, O (2013b, August 29) Registration Review Process [Overviews and Factsheets] Registration Review Process https://www epa gov/pesticide-reevaluation/registration-review-pro cess

Weeks, J , Guiney, P , & Ai Nikiforov (2012) Assessment of the environmental fate and ecotoxicity of N,N‐ diethyl ‐ m‐ toluamide (DEET) Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 8(1), 120–134 https://doi org/10 1002/ieam 1246

Immune Inter ference

Is aberrant DUX4 expression responsible for the downregulation of MHC class I genes stimulated by IFN-γ?

Abigail Getnick and Kelan McKay

Introduction

The gene Double Homeobox 4 (DUX4) is a transcription factor typically active during early embryonic development that plays an important role in regulating other genes during this period Past this stage, the DUX4 gene is typically repressed by both genetic and epigenetic processes, including DNA methylation and histone modifications. However, derepression caused by genetic mutations or loss of epigenetic silencing can lead to reexpression of DUX4 (Karpukhina et al , 2021) This aberrant DUX4 expression is believed to be the primary driver of muscle degeneration in Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD), a rare type of progressive muscula r dystrophy (Schätzl et al , 2021) DUX4 has also been found to be re-expressed in many solid cancers, and researchers have suggested that this upregulation may allow cancerous cells to evade detection from the immune system (Smith et al., 2023).

The current consensus is that immune evasion of cancer by the activation of DUX4 is driven by suppression of the Major Histocompatibility Complex class I (MHC I) MHC I refers to a set of genes that encode vital proteins that allow the immune system to detect and respond to foreign pathogens by presenting the immune system with peptide fragments of these pathogens. To do so, MHC I proteins break down intracellular proteins and bring their fragments to the cell ’s surface, allowing for immune cells such as T-cells and Natural Killer (NK) cells to recognize and destroy pathogens, including various bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells (Janeway et al., 2001). In the absence of MHC class I gene expression, diseased cells and other pathogens can more easily evade detection by the immune system For cancer, the suppression of MHC I may allow for undisturbed proliferation. MHC I suppression has also been

found to make developing immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint blockade, less effective for solid cancers Due to these findings, researchers have reported that upregulating MHC class I genes may allow for more effective application of immunotherapy against solid tumors (Cornel et al., 2020; Pineda & Bradley, 2023)

To study aberrant DUX4 expression, researchers use genetically modified cell lines with Tet-On systems in which doxycycline can be used to control activation of DUX4 transcription To create these Tet-On systems, a cell line is modified by introducing a reverse tetracyclinecontrolled transactivator (rtTA). When doxycycline is added, it binds to the rtTAs, causing them to change shape and allowing them to bind to the tetracycline response element (TRE) promoter upstream of the promoter that controls the DUX4 gene. When this connection occurs, the DUX4 gene is activated and transcription will occur. In the absence of doxycycline, the rtTAs remain unbound and the DUX4 gene stays dormant (Das et al , 2016) This system allows researchers to control when DUX4 is expressed in cells and research its effects more precisely. One known issue with these systems is leaky DUX4 expression. Past studies have found low levels of DUX4 RNA, even in the absence of doxycycline (Dandapat et al , 2014) Regardless of this challenge, these models have been key in learning more about aberrant DUX4 expression.

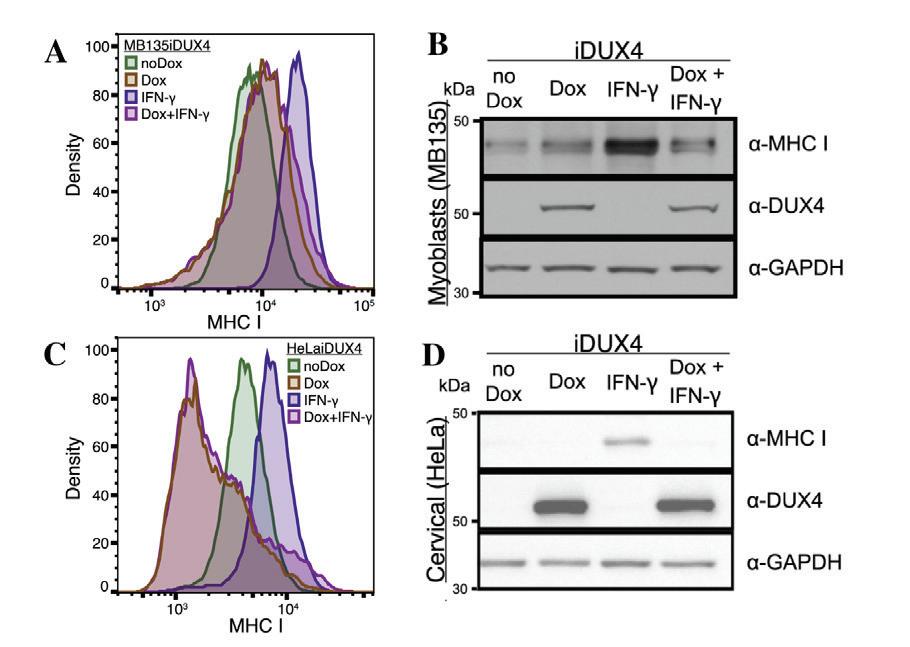

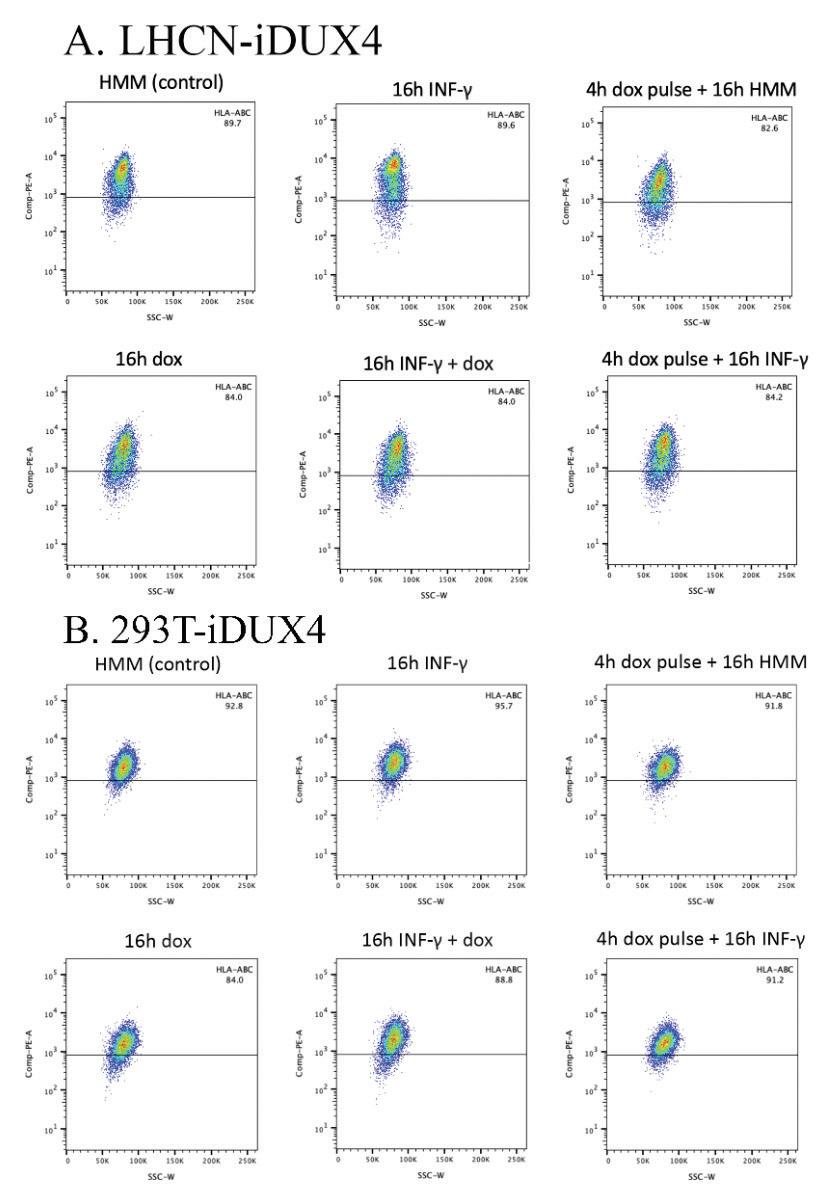

Working in the Tapscott Lab, Chew et al (2019) investigated how DUX4 expression affects MHC class I protein expression in vitro. Using several cancer cell lines with doxycycline-inducible DUX4, they reported that DUX4 expre ssion caused a decrease in MHC I protein levels measured using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis and western blots

(Figure 1C, D). Researchers also reported that treating these cancer cells with only interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) increased MHC I protein levels while the induction of DUX4 via doxycycline in addition to the INF-γ treatment decreased MHC I protein levels. In an inducible myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4), Chew et al. also reported that DUX4 induction reversed the increase in MHC I protein levels caused by the IFN-γ treatment (Figure 1A, B) Although not discussed in the paper, FACS analysis and western blots showed a slight increase in MHC I expression in myoblast cells when DUX4 was activated in the absence of IFN-γ (Figure 1A, B).

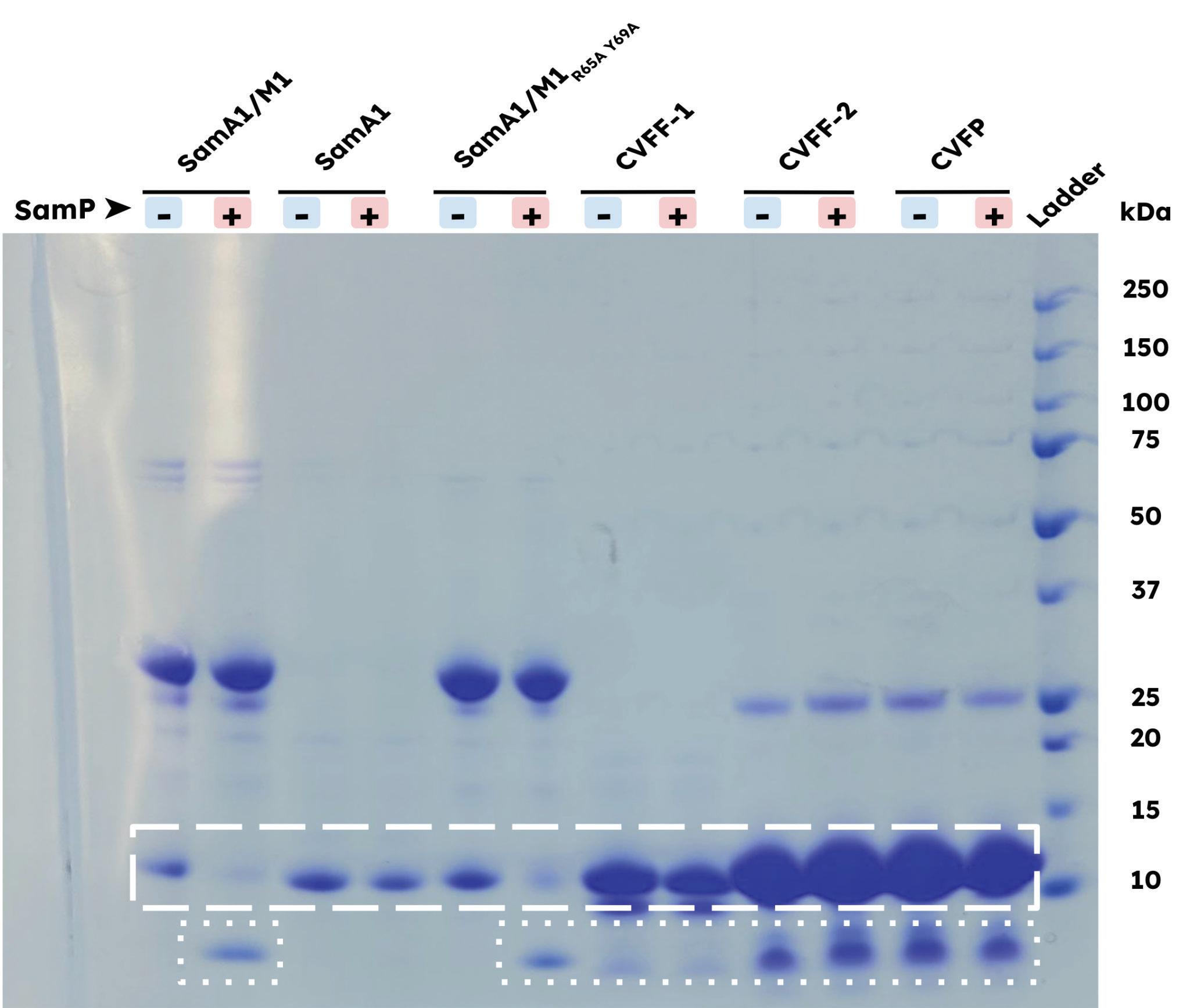

Figure 1. FACS data (A and C) and western blot data (B and D) showing effects of DUX4 activation (via doxycycline) and IFN-γ treatment on MHC I protein expression in an inducible myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4) and an inducible cancer cell line (HeLa-iDUX4). (A) FACS data of MHC class I protein levels in myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4) showing slight upregulation of MHC I with DUX4 activation. (B) FACS data of MHC class I protein levels in a cancer cell line (HeLa-iDUX4) showing downregulation of MHC I with DUX4 activation (C) Western blot data for MHC class I, DUX4, and GAPDH proteins for myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4). (D) Western blot data for MHC class I, DUX4, and GAPDH proteins for cancer cell line (HeLa-iDUX4) Modified from Figure 5 in Chew et al , 2019

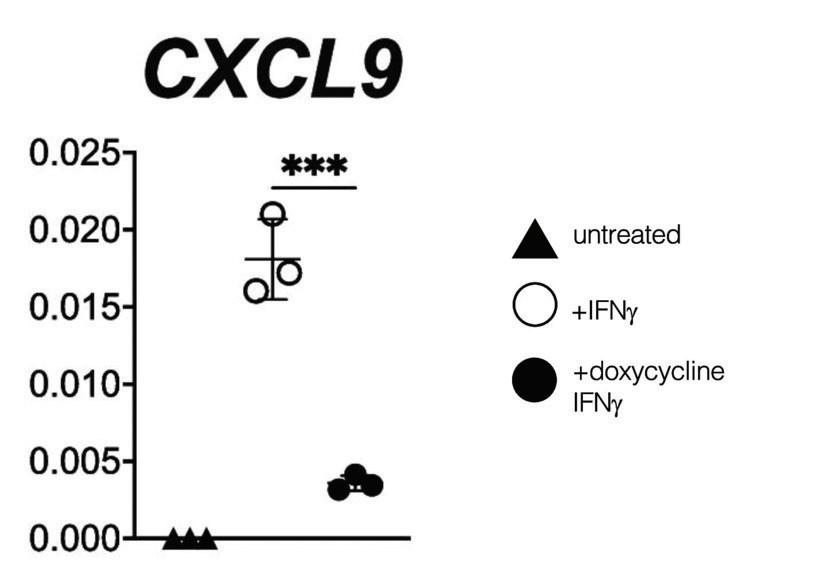

Also working in the Tapscott Lab, Spens et al. (2023) similarly investigated DUX4 repression of IFN-γ-stimulated gene induction Performing Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) on myoblast cell lines with inducible DUX4, they reported that IFN-γ stimulates an increase

in mRNA levels of CXCL9, an IFN-γ-stimulated gene involved in MHC. CXCL9 expression was reduced, but not eliminated, by DUX4 activation (Figure 2) Using chromatin immunoprecipitation, they also found a decrease in STAT1 binding to promoters of immune-related genes with DUX4 activation. They concluded that DUX4 directly suppresses interferondependent gene expression, leading to a reduction in interferon signaling pathway activity Notably, this study did not look at the effect of DUX4 activation in the absence of IFN-γ treatment.

Figure 2. RT-qPCR showing effects of IFN-γ and DUX4 (via doxycycline) treatments on myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4) RT-qPCR results of three treatments: untreated, 16 hour IFN-γ, and 4 hour doxycycline followed by 16 hours with IFN-γ in a myoblast cell line (MB135-iDUX4) showing upregulation in the presence of IFN-γ and downregulation in the presence of DUX4 expression (via doxycycline) Modified from Figure 1 in Spens et al , 2023

As part of our duties in the Bosnakovski lab, we ran an experiment designed to test the effects of two drugs on DUX4 induction in the myoblast cell line LHCN-iDUX4 Based on the published results, we looked for decreases in MHC I protein levels as an indicator of DUX4 repressive activity However, using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis, we found that regardless of DUX4 activation, the samples demonstrated strong, nearly 100%, expression of the MHC I proteins β2-microglobulin (B2M), and human leukocyte antigens (HLA) HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C.

These results conflicted with the data presented by previous research. This research was conducted by a single research group that concluded that DUX4 activation significantly suppresses MHC I expression in all inducible cell lines (Chew et al., 2019). This contradiction between our results and published results led us to wonder whether there may be a difference in how DUX4 behaves in myoblast cell lines versus cancer cell lines, in different versions of inducible DUX4 cell lines, or under different cell culture conditions.

We attempted to replicate published findings of DUX4 suppression of IFN-γ-stimulated MHC class I transcripts and proteins in both myoblast and cancer cell lines using the established protocols and cells used by the Bosnakovski Lab To formally investigate our preliminary observations, we tested whether MHC class I genes in both myoblast and cancer cell lines are suppressed by DUX4 expression in the presence and absence of IFN-γ.

We used six human myoblast cell lines: LHCN-iDUX4, D3F-iDUX4, D13D-iDUX4, 001-56 iDUX4, 007-56 iDUX4, and 008-56 iDUX4 as well as two cancer cell lines: 293T-iDUX4 and A204-iDUX4 All cell lines were DUX4 inducible via doxycycline Only the A 204-iDUX4 cells have been published to demonstrate the downregulation of MHC I with DUX4 induction (Chew et al., 2019). We performed six different treatments on each cell line: a control group treated with cell media; a 16-hour IFN-γ treatment; a 16-hour continuous doxycycline treatment; a 16-hour treatment of IFN-γ and doxycycline; a 4-hour doxycycline pulse followed by 16-hours in cell media; and a 4-hour doxycycline pulse followed by a 16-hour IFN-γ treatment We used FACS analysis to measure protein levels in all cell lines and performed qPCR on one cell line to both confirm that DUX4 was being properly induced and measure MHC class I mRNA levels.

Abigail Getnick and Kelan McKay

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Immortalized human myoblast cell lines were cultured according to standard cell culture procedures. Cells were plated in T-25 flasks and transferred to T-75 flasks once they hit 70% confluence Media was changed every three days until cells were confluent enough to plate in 12-well plates filled with 1 mL of the cell solution. The plates were then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere until cells had attached to the plate surface and were ready for treatments

Treating Cells

Cells plated in 12-well plates were treated with 10 μM lamivudine (3TC; TargetMol), 10 μM abacavir sulfate (ABC; TargetMol), and 200 ng/mL interferon-gamma (IFN-γ; BioLegend) diluted with cell media DUX4 was induced with doxycycline diluted in cell media to achieve a concentration of 200 ng/mL. The drugs were first added to media in 15 mL tubes to reach their respective dilutions. The well plates were then aspirated and the treatments were added to their respective wells The plates were then incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere until the treatment period was completed.

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

To perform Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis, treated well plates were aspirated and washed with 1x PBS The samples were trypsinized, collected in 15 mL conical tubes, and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1,300 rpm. The supernatant was aspirated and the samples were washed with 2% FBS PBS. They were then stained with two antibodies, 25 µg/mL HLA-A,B,C (BioLegend) and 100 µg/mL β2-microglobulin (B2M; BioLegend), in a 1:333 dilution with 2% FBS PBS. After staining, the samples were washed with 2% FBS PBS and resuspended in a solution of propidium iodide (MilliporeSigma) The samples were then run using a BD FACSAria flow cytometer Data was analyzed using FlowJo (BD Biosciences)

RNA Extraction

After treatments, well plates designated for RNA analysis were aspirated, washed with 1x PBS, and stored at -80ºC until ready for RNA extraction Standard RNA isolation procedures used to extract RNA with Zymo Research Direct-zol Miniprep Kit RNA samples were then brought to the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to measure their concentrations before storing them at -80ºC for future needs

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

To perform Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR), “master mixes” were created for each probe and primer being used For each master mix, 2.2 μl of premix per sample was used. Premix Ex Taq (Probe qPCR, Takara) was used for probes and TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Primer qPCR, Takara) was used for primers The premix was combined with 0 044 μL of Rox Reference Dye II (Takara) per sample, 0 248 μL of HyPure Molecular Biology Grade Water per sample, and 0.066 μL of the respective probe or primer per sample The master mixes were vortexed thoroughly and spun down before being stored on ice A multichannel pipette was used to plate the master mixes and cDNA samples in triplicates for qPCR in a 384-well plate. Samples were run using a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) Data was obtained using the 7500 System Software (Applied Biosystems) For analysis, all probes and primers were normalized to ACTINB, a common housekeeping gene used because of its high expression across many different cells (Chin, 2020)

Results

Confirming DUX4 Activation

To confirm DUX4 activation via doxycycline, qPCR was run on LHCN-iDUX4 cells to measure the expression of DUX4 target genes. When DUX4 is turned on, it activates a set of target genes that can lead to apoptosis, degrade myoblast cells (causing FSHD), and suppress the immune response Because DUX4 is extremely

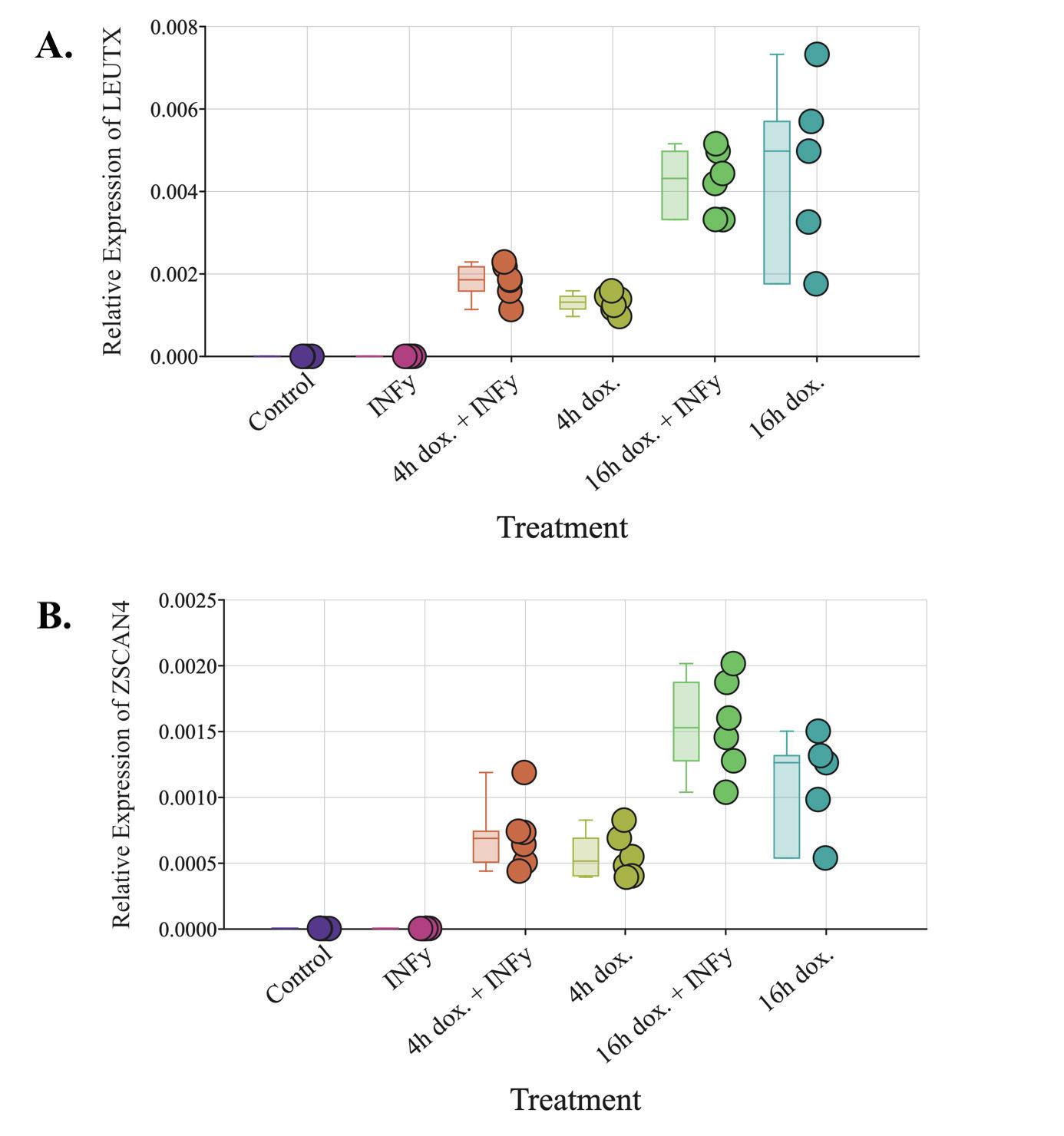

difficult to identify due to only being detectable in extremely low levels (<0.1% of cells), target genes such as LEUTX and ZSCAN4 are commonly used as biomarkers to indicate DUX4 expression (Banerji et al , 2020) ZSCAN4 mRNA levels were significantly higher (p≤0.01; ANOVA; Figure 3) in all treatments that included doxycycline (the 4 hour doxycycline treatment followed by IFN-γ, the 4 hour doxycycline treatment alone, the 16 hour combination treatment of doxycycline + IFN-γ, and the 16 hour doxycycline treatment alone) compared to the control.

Figure 3. qPCR results for DUX4 target genes on LHCN-iDUX4 cells (A) Relative expression of LEUTX with respect to ACTINB in LHCN-iDUX4 cells (B) Relative expression of ZSCAN4 with respect to ACTINB in LHCN-iDUX4 cells Control: cells cultured in 20% FBS HMM (n=6). IFN-γ: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6) 4h dox and IFN-γ: 4 hour exposure to 200 ng/mL doxycycline followed by a 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6). 4h dox: 4 hour exposure to 200 ng/mL doxycycline followed by a 16 hour period in 20% FBS HMM (n=6) 16h dox and IFN-γ: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline and 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6) 16h dox: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline (n=5). (Figure by authors).

Compared to the control, LEUTX mRNA levels were also significantly higher in all samples

treated with doxycycline with the exception of the 4 hour doxycycline treatment. Both LEUTX and ZSCAN4 mRNA levels were significantly higher in the 16 hour doxycycline treatment compared to the 4 hour doxycycline treatment LEUTX and ZSCAN4 mRNA levels were significantly upregulated (p<0.05) in the 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment compared to the IFN-γ treatment alone LEUTX and ZSCAN4 mRNA expression also increased significantly (p<0 01) in the 16 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment compared to the IFN-γ treatment alone.

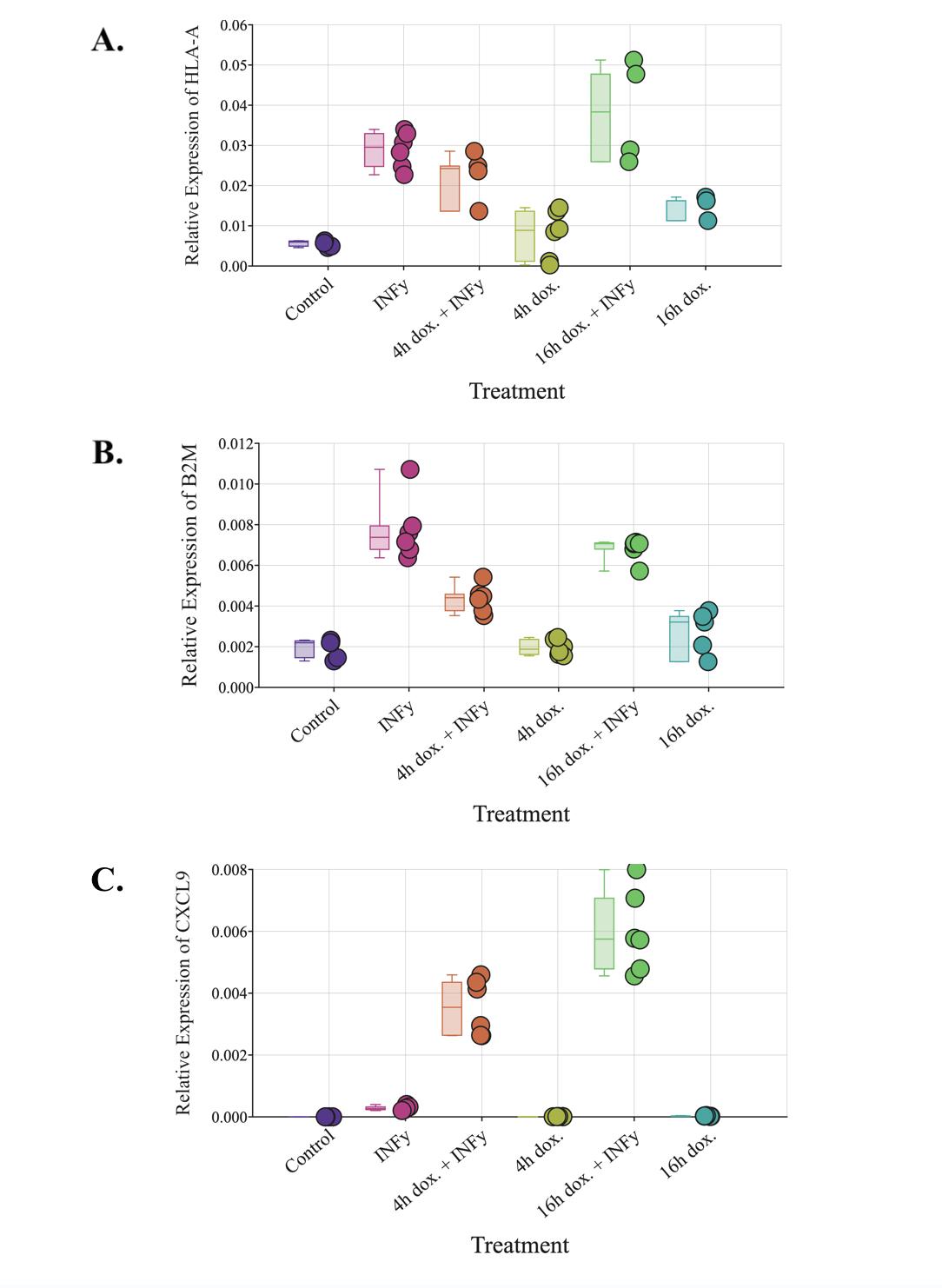

Effect of DUX4 on B2M and HLA-A mRNA expression

The qPCR was also run on LHCN-iDUX4 cells for MHC class I genes HLA-A and B2M. HLA-A is one of the three types of MHC class I genes found in humans that present antigens on a cell ’s surface (Janeway et al , 2001) B2M is also vital to the function of MHC class I (Wang et al., 2021). HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels both significantly increased (p<0.01; ANOVA; Figure 4) in samples treated with IFN-γ compared to the control HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels were also significantly higher (p<0.01) in the 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment compared to the control. There was a significant increase (p<0 01) in B2M mRNA in the IFN-γ treatment compared to the 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment, but HLA-A mRNA did not show a similar significant increase between these two treatments. The 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment also had significantly higher (p<0 05) HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels than the 4 hour doxycycline pulse alone The HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels were not significantly different in the 4 hour doxycycline pulse alone compared to the control. The 16 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment caused significantly higher (p<0 01) HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels compared to the control as well as significantly higher (p<0 05) HLA-A and B2M mRNA levels compared to the 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment. The 16 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment did not cause significantly different HLA-A or B2M mRNA levels compared to the treatment of

Abigail Getnick and Kelan McKay

IFN-γ alone but did cause significantly higher levels of HLA-A and B2M mRNA (p<0.01) compared to the 16 hour doxycycline treatment There was no significant change in HLA-A or B2M mRNA levels between the 16 hour doxycycline treatment and the control or between the 4 hour and 16 hour doxycycline treatments.

exposure to 200 ng/mL doxycycline followed by a 16 hour period in 20% FBS HMM (n=6) 16h dox and IFN-γ: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline and 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (HLA-A: n=4; B2M: n=6) 16h dox: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline (HLA-A: n=3; B2M: n=5) (Figure by authors)

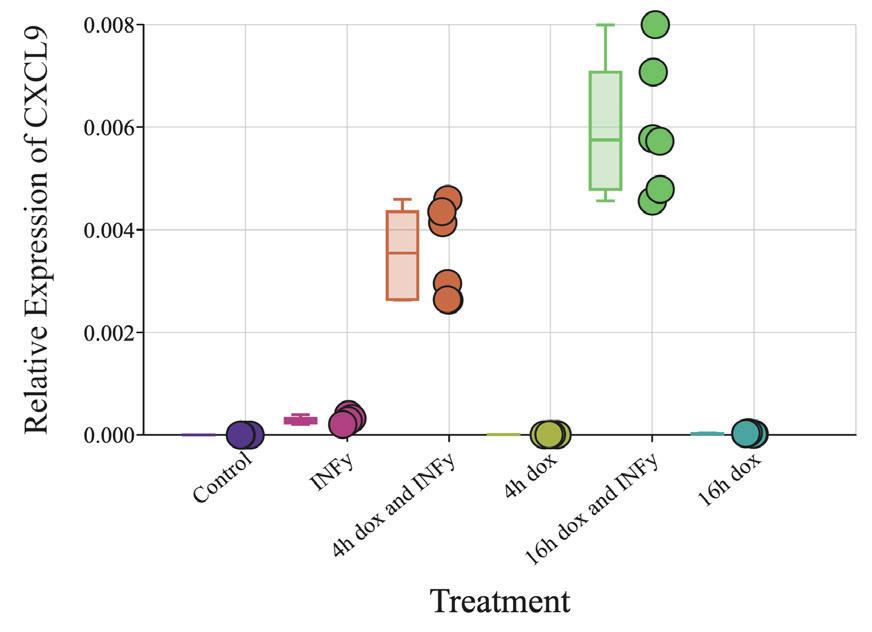

Effect of DUX4 on CXCL9 mRNA expression

CXCL9 is a chemokine that plays a vital role in signaling T cells toward tumor sites and is known to be upregulated by IFN-γ (Ding et al., 2016). Unexpectedly, when compared to the

control, the IFN-γ treatment did not significantly increase the level of CXCL9 mRNA. However, there was a significant increase (p<0 01; ANOVA; Figure 5) in the level of CXCL9 mRNA from the control to the 4 hour doxycycline pulse + IFN-γ treatment. The 16 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment also caused a significant increase in the CXCL9 mRNA level (p<0 01) compared to the control The 16 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment samples had even higher (p<0 01) mRNA levels than the 4 hour doxycycline + IFN-γ treatment. Both the sample treated with 4 hours of doxycycline and the sample treated with 16 hours of doxycycline showed no significant difference in CXCL9 mRNA levels when compared to each other or the control

Figure 5. qPCR result for CXCL9 on LHCN-iDUX4 cells. Relative expression of CXCL9 with respect to ACTINB in LHCN-iDUX4 cells.

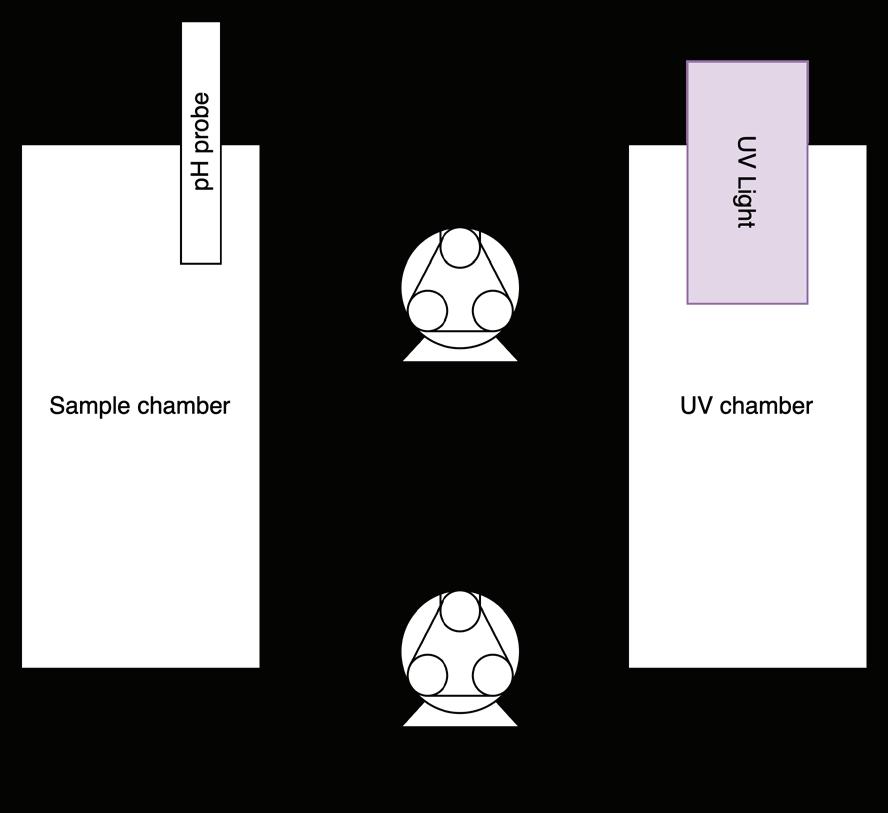

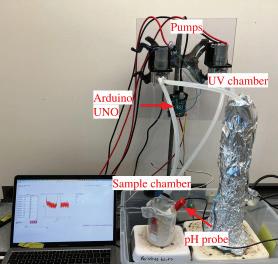

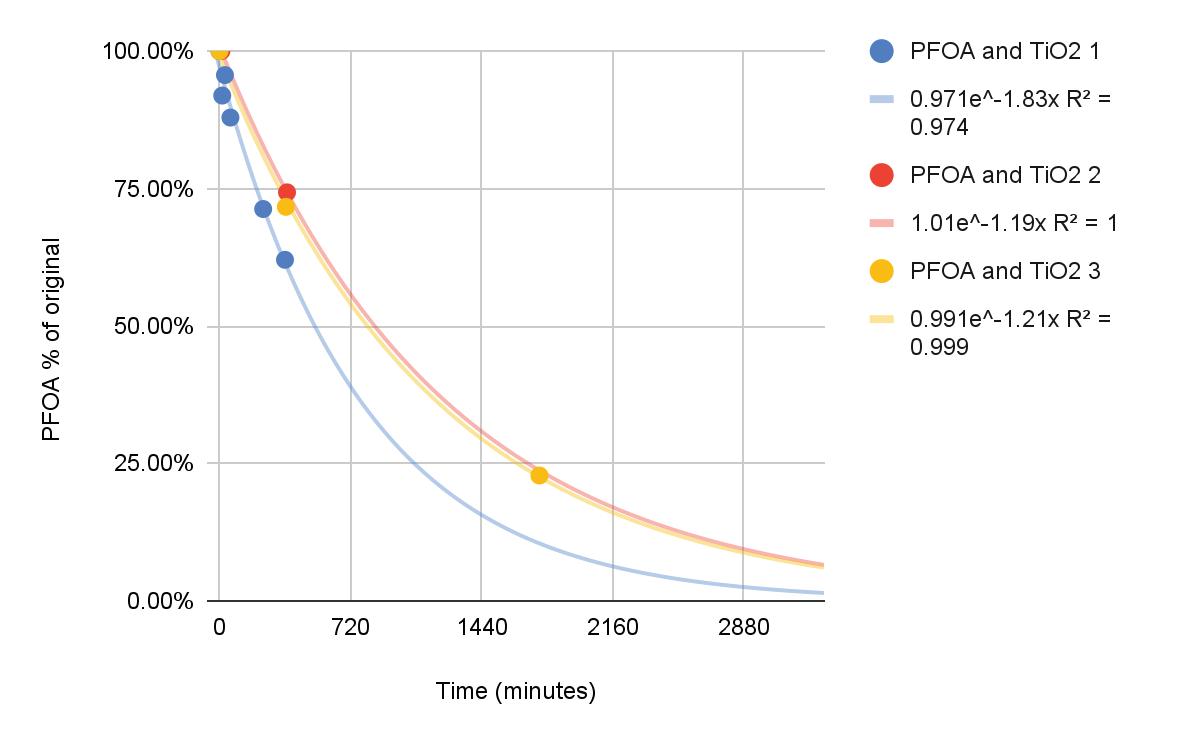

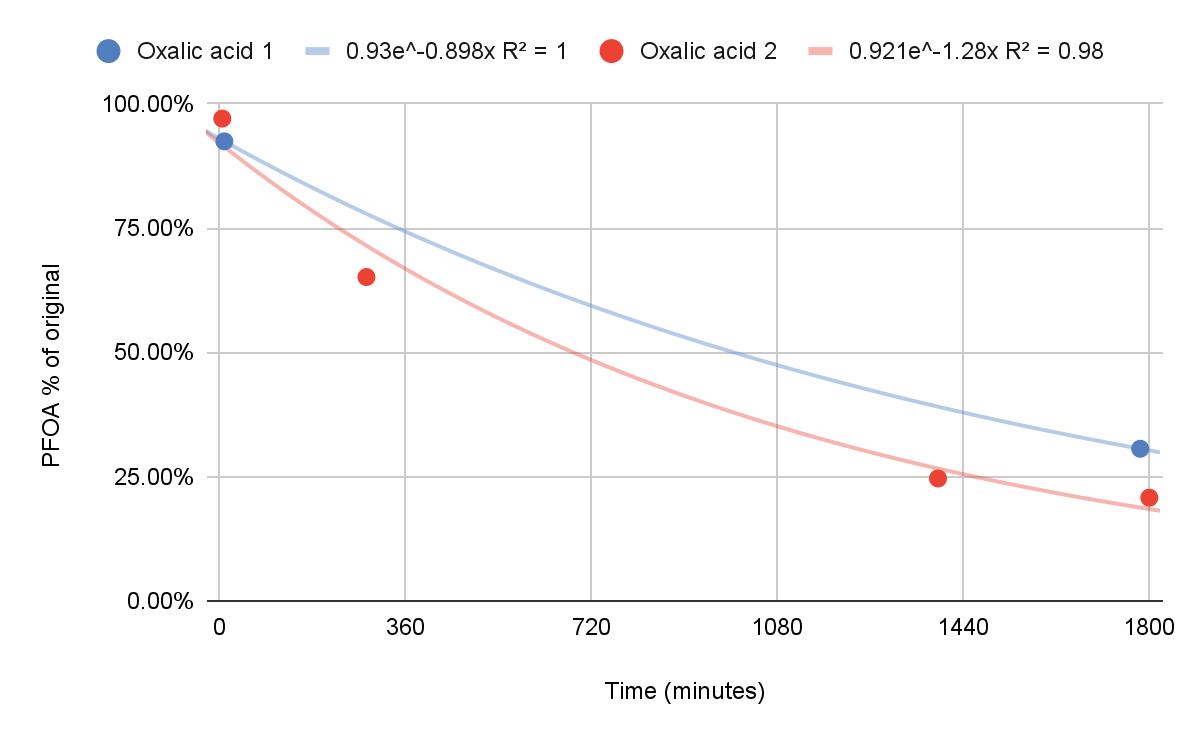

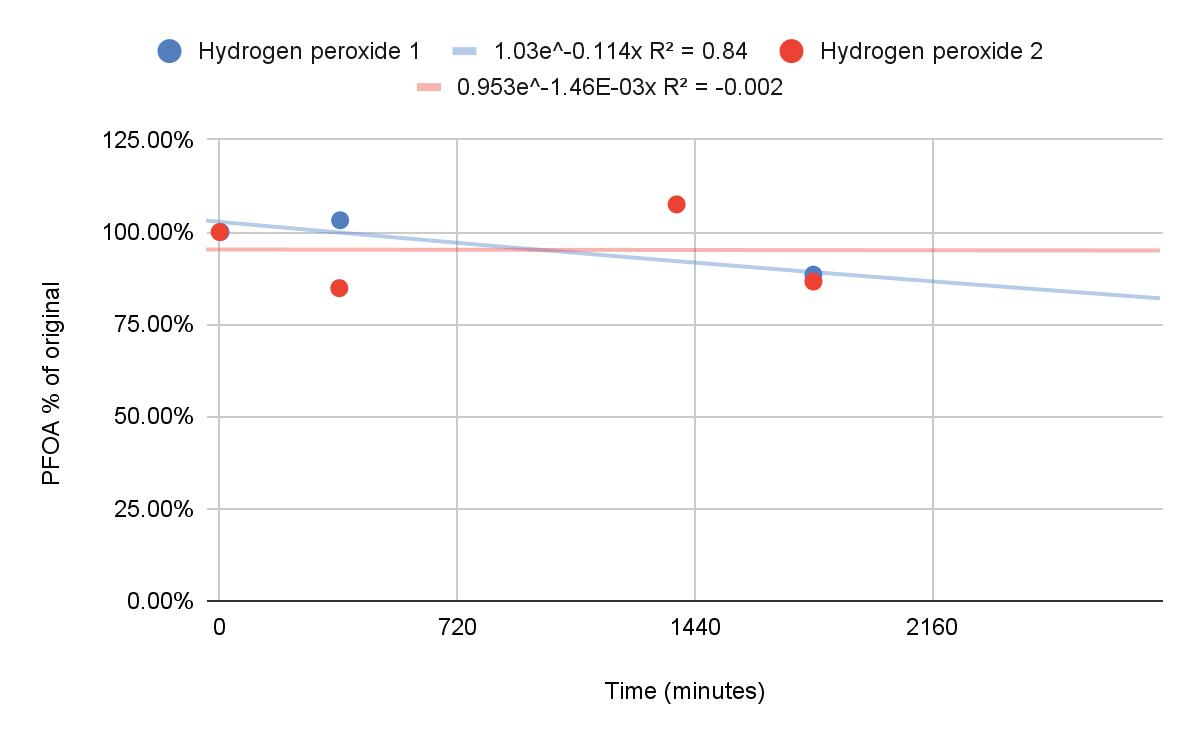

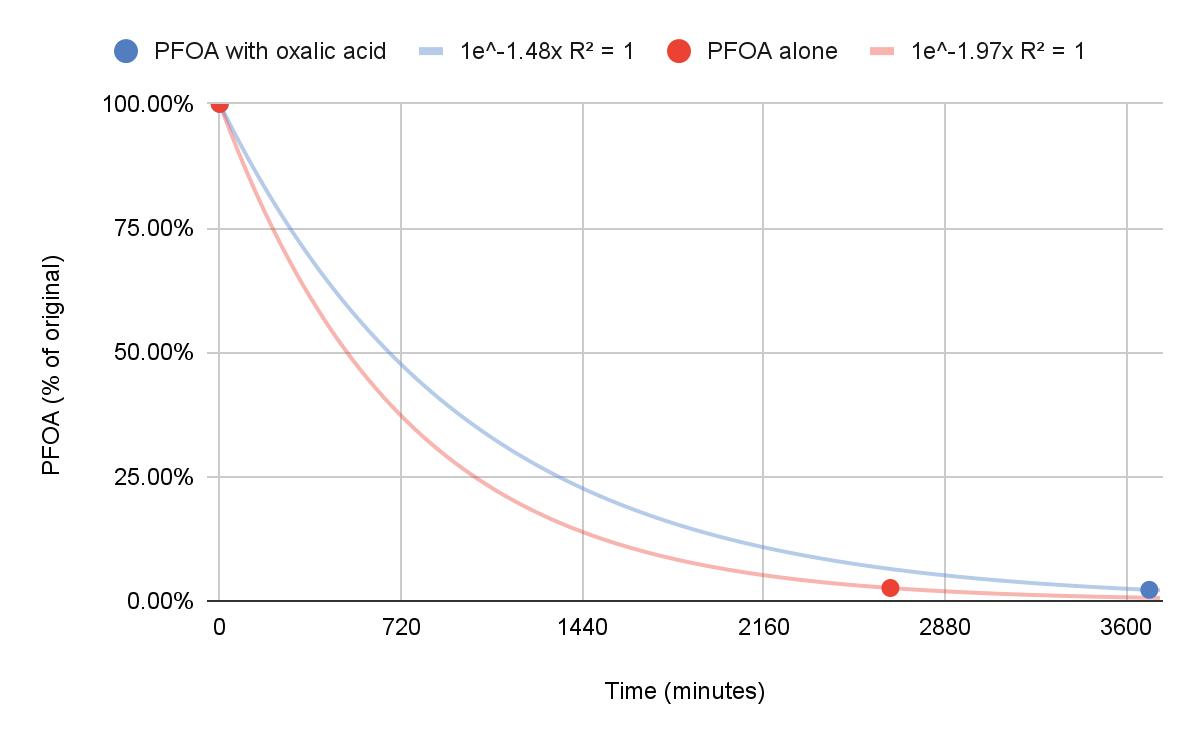

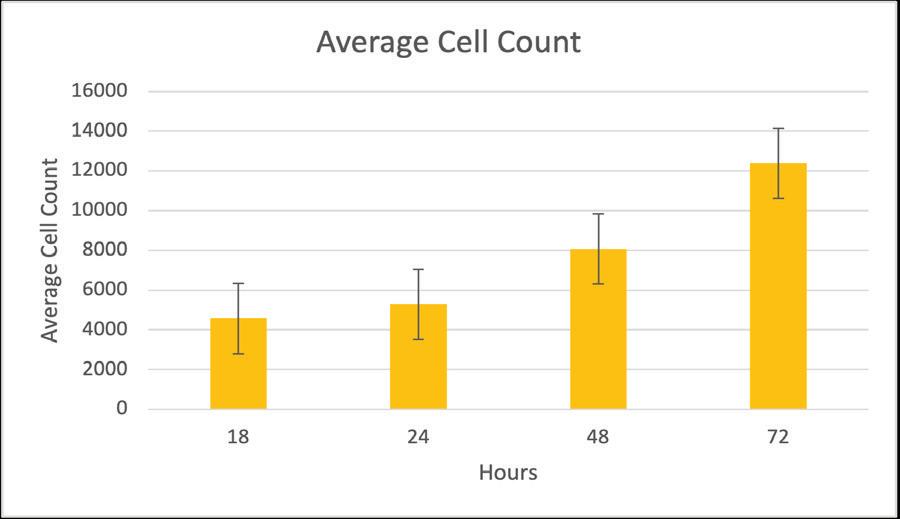

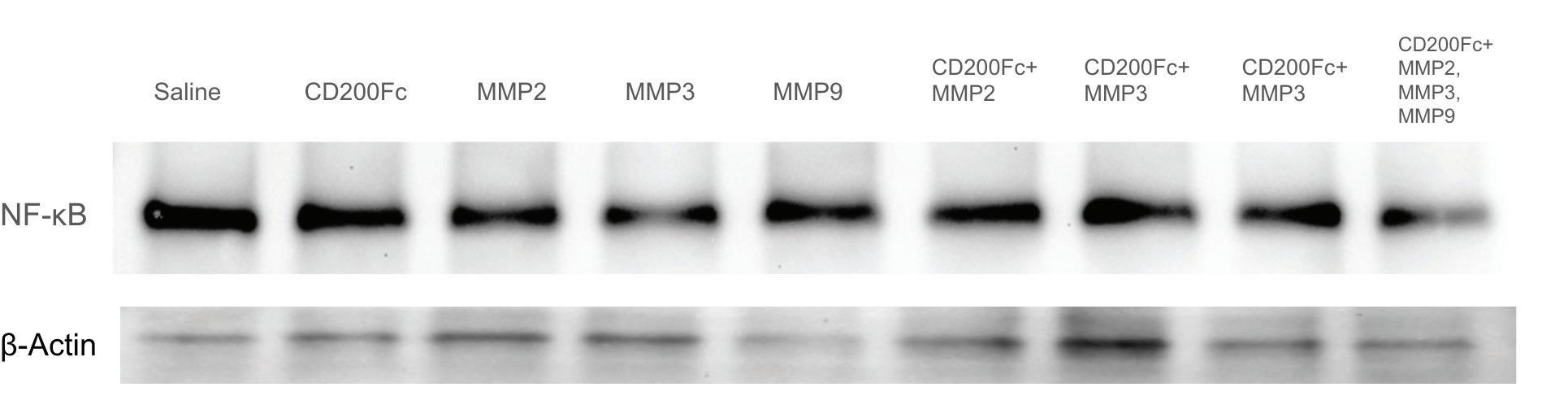

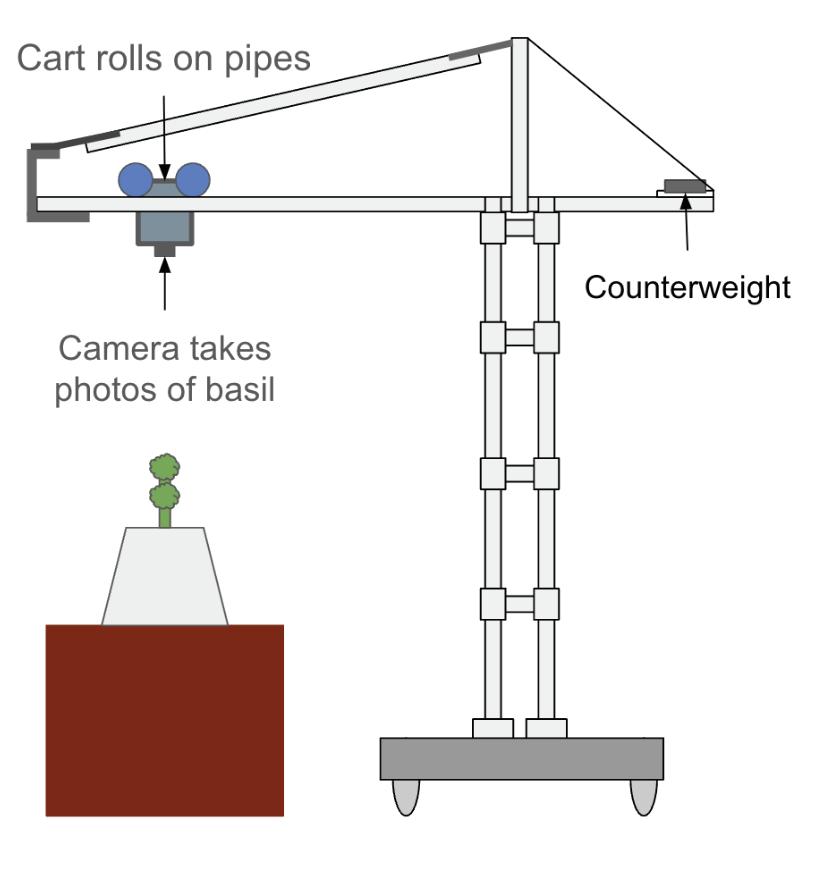

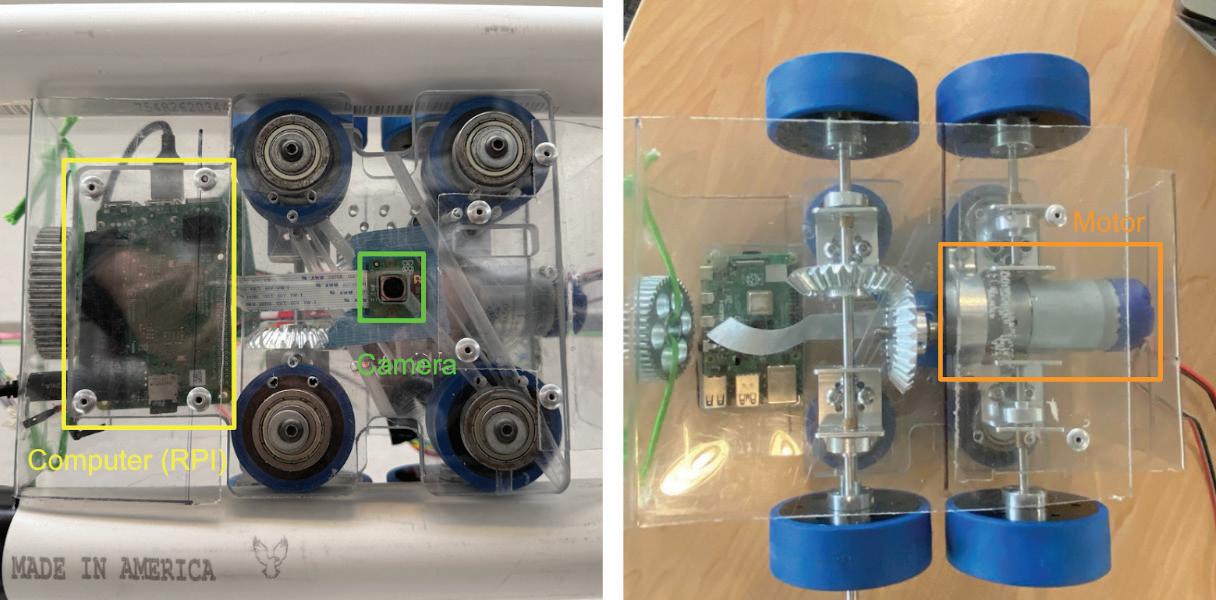

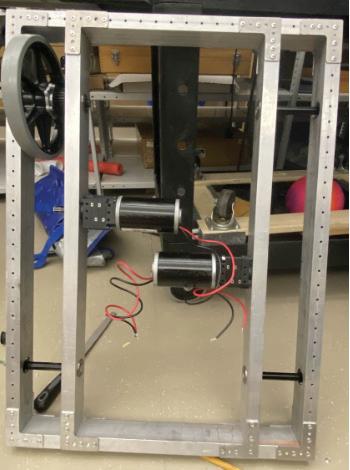

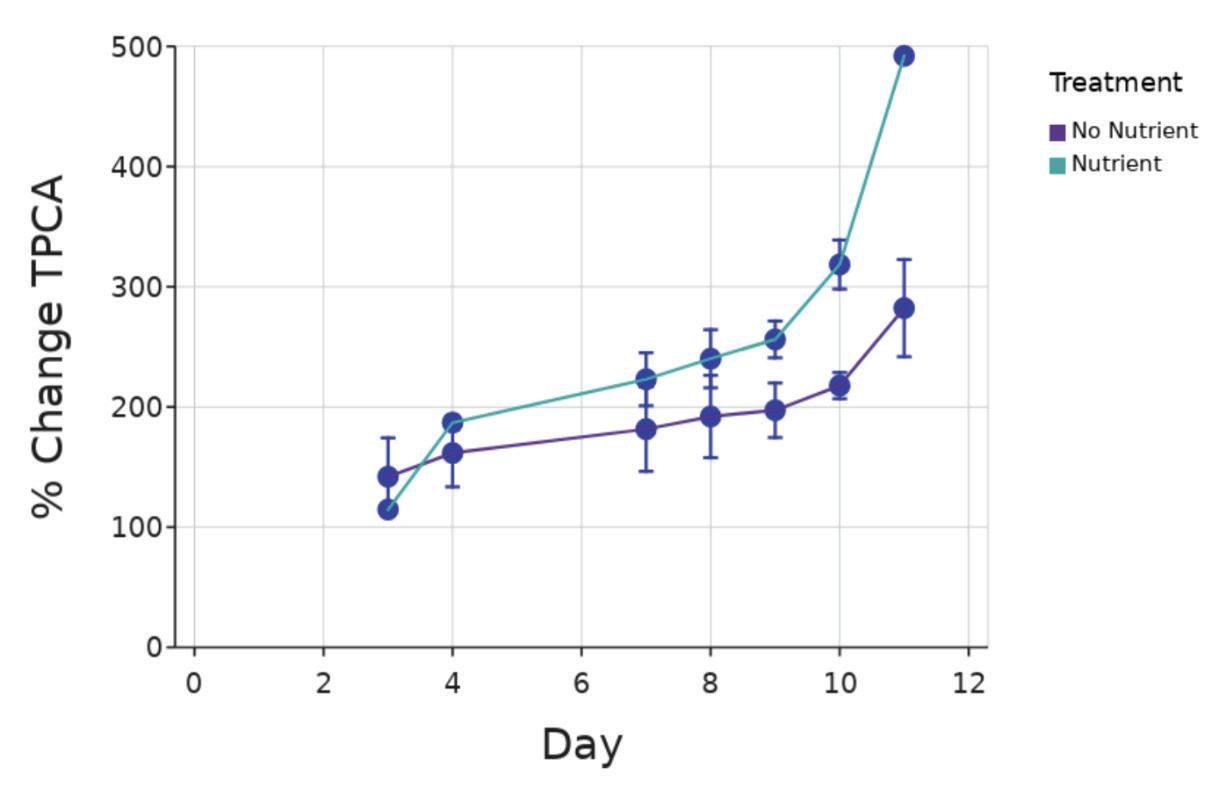

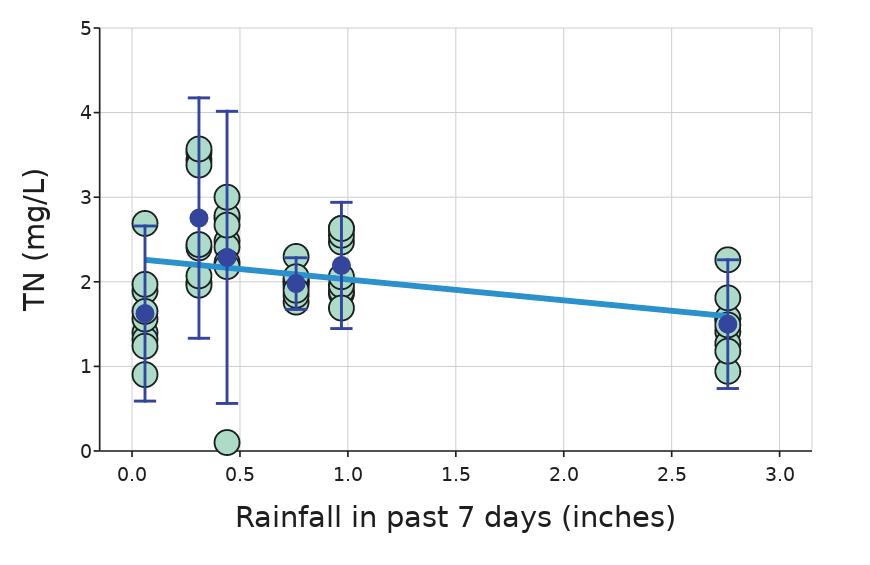

Control: cells cultured in 20% FBS HMM (n=6) IFN-γ: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6) 4h dox and IFN-γ: 4 hour exposure to 200 ng/mL doxycycline followed by a 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6) 4h dox: 4 hour exposure to 200 ng/mL doxycycline followed by a 16 hour period in 20% FBS HMM (n=6) 16h dox and IFN-γ: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline and 200 ng/mL IFN-γ (n=6). 16h dox: 16 hour treatment with 200 ng/mL doxycycline (n=5) (Figure by authors)