A Common Grace

Calvin University & Calvin Theological Seminary

God is glorified in the total development toward which human life and power over nature gradually march on under the guardianship of ‘common grace.’ It is His created order, His work, that unfolds here. It was He who seeded the field of humanity. . . . Without common grace the seed which lay hidden in that field would never have come up and blossomed.

—Abraham Kuyper, Common Grace, Volume 1

Copyright 2025 © Calvin University & Calvin Theological Seminary

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Calvin University & Calvin Theological Seminary.

Calvin University & Calvin Theological Seminary Grand Rapids, Michigan USA calvin.edu calvinseminary.edu

Author Sarah Turnage

150th Anniversary Program Director Heidi DeBlecourt

History Consultant Dr. Will Katerberg

BOOK DEVELOPMENT

Editor Rob Levin

Cover and Book Design Richard Korab

Project Management Stacy Moser

Production Management

Renée Peyton Covington, Georgia www.bookhouse.net

March 15, 1876, was the day Calvin Theological Seminary and what has now become Calvin University were born. Calvin had a very small beginning 150 years ago, and we doubt if there was even a birthday cake! n A single pastor was identified by the Christian Reformed Church’s Synod of 1876 to be the sole teacher of a new school. That synod also decided that they were going to follow the curriculum from the theological school of Kampen in the Netherlands. The delegates to synod, representing 22 churches in all at the time, also pledged to pay the teacher’s salary and support the school. At the end of the installation service, Rev. Geert Egberts Boer looked out at the five students who were being taught and welcomed two more for a total of seven students in the fall of 1876. n Here are Rev. Boer’s words from that day: “I now stand in a special, specific relation to you. This tie will be drawn ever tighter in a communion of true faith; henceforth I hope to work at your training and development; to point out to you your needs according to the requirements of the times, to warn you of dangerous shoals upon which you could easily be shipwrecked, to teach you and to pray with and for you—this is the task that awaits us.” n The year 1876 was marked by a centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence in the United States, just a few years after the spilling of blood from a national civil war came to an end. Ahead would be world wars, depressions, technological wonders, and more that all led to the global connections we may take for granted. n The founders and supporters of Calvin could not know what was going to unfold. What they did know, and what they

trusted, was that this was an endeavor God was calling them to take up. n As presidents, we have had the opportunity to work with countless others in the planning of the 150th celebration of Calvin—both Calvin Theological Seminary and Calvin University. We have reflected on early stories, current challenges, and future hopes. n Through the twists and turns of challenges and opportunities that Calvin has faced and will face, there is a trust that God is not done working in us and through us. We invite your own reflections on the descriptions given by Jesus of the Kingdom of God in Matthew 13. n The founders and supporters of Calvin in 1876 were seeking to be faithful in their moment. They were trusting that God would bless their steps, but we are sure they did not know where those steps would eventually lead. What has unfolded in the story of Calvin?

The story of Calvin is one of global connections

The university and seminary are made up of students, faculty, staff, and alumni who come from around the world and serve across the globe.

The story of Calvin is one for every square inch

The well-known quote of Abraham Kuyper has helped define the scope of the work and vision at Calvin: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!” n This world and life view emphasizes that Christ has ownership and dominion over every aspect of life. Calvin grew from a school focused on training pastors

31 He told them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed, which a man took and planted in his field. 32 Though it is the smallest of all seeds, yet when it grows, it is the largest of garden plants and becomes a tree, so that the birds come and perch in its branches.’

33 He told them still another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed into about sixty pounds of flour until it worked all through the dough.’

—Matthew 13:31–33

(which we still do), but now disciplines from philosophy to biology, education to business, and myriad other fields have developed because of the seeds planted over these past 150 years. Every square inch is ripe for renewal, so we send graduates out into every sphere to facilitate the flourishing that God intends for His creation.

The story of Calvin is one of leavening

In the scope of the wider world, we may feel like our story is a small one, but Calvin has provided “leaven” in different ways and has provided learning and perspective for countless individuals and communities in those different spheres of life that God has developed.

The story of Calvin is one of bridge-building Calvin has been a place where people beyond the Christian Reformed Church have found community. From the Symposium of Christian Worship and the Meeter Center, to The de Vries Institute of Global Faculty Development and the Kuyper Conference, the gatherings and institutes that Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary have developed have become vital “third places” for hospitality and hope. Calvin is committed to reaching out as partners in teaching, learning, and scholarship with other institutions in higher education and beyond.

The story of Calvin becomes one of blessing

The biblical mandate is clear. We who are blessed with the gospel story need to share that message with others.

We are witnesses of God’s faith, grace, hope, and love. We are called to be a blessing to others. n The scope of the Kingdom of God is more than the world of Calvin, of course, but we are called to do our part. We are called to be faithful in our moment and take the next step on the ongoing journey that God has set before us. n As you review pictures and stories of the last 150 years, will you join us and pledge again, like those who have gone before us, that we will do our part as God uses us and these institutions to build up His Church and Kingdom? To God be the glory for great things He has done!

Geert Boer

Theological School’s First Professor

Johannes Broene College Interim President

James A. DeJong Seminary President

Johannes Broene College President

Samuel T. Volbeda Seminary President

CHAPTER ONE

Calvin’s origins trace back to 1865 in Graafschap, Michigan, where Reverend Douwe J. Vander Werp began training young men for ministry in his humble parsonage. Appointed by the True Holland Reformed Church, Vander Werp’s living room served as the first classroom for what would grow into a formal denominational school in Grand Rapids by 1876. Rooted deeply in Dutch Reformed principles, the curriculum of De Theologische School, as it was then known, expanded beyond theological training in the 1890s to provide broader education while maintaining its spiritual foundation. This unwavering commitment to the integration of faith and learning has shaped every stage of development into the present-day Calvin Theological Seminary and Calvin University.

On a brisk March day in 1876, the Christian Reformed Church’s (CRC) fledgling Theologische School opened its doors to students in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The first instructor, Rev. Geert Egberts Boer, brought his experience as a pastor from the Netherlands to guide the school’s modest, yet critical, mandate: training pastors for Dutch immigrant congregations to replace the only itinerant minister. Lacking resources for a proper seminary building, Boer’s first lectures took place on the rented upper floor of a Christian school on Williams Street. By 1892, the CRC synod had funded and built the school’s first dedicated facility, a sturdy brick structure on Madison Avenue that was optimistically deemed to be sufficient for decades to come.

These humble origins belied an ambitious vision, and the school had two programs from the start: “literary” preparation with general education courses, followed by theological subjects for seminary training. Reverend Boer believed in training the mind broadly, just as he had been educated at the Kampen seminary in the Netherlands. He introduced his future seminarians to geography, Dutch literature, logic, and mathematics “to think, to reason, and to discriminate” beyond pulpit duties. Once students completed this initial course of study, their seminary training centered on biblical and ministerial subjects: Bible and church history, Reformed doctrine, and preaching. Though all instruction was conducted in Dutch for decades, this curricular approach foreshadowed a broader academic mission. Meanwhile, church leaders, who had previously rejected several students’ request to study elsewhere briefly to learn English, realized that clinging solely to the Dutch language was alienating youth who lived in an English-speaking society. In 1888, the school appointed Geerhardus Vos as its first Englishproficient professor, tasking him not only with teaching theology and other courses, some in English, but also with preaching in English on Sundays. While there were students who initially resisted this English focus—a language they did not readily understand since they had been raised in Dutch-speaking homes—others embraced the change. Though the language of the seminary and church would remain Dutch into the 1920s, this shift signaled that, by the early 1890s, Calvin was already encouraging

the slow process of Americanization.

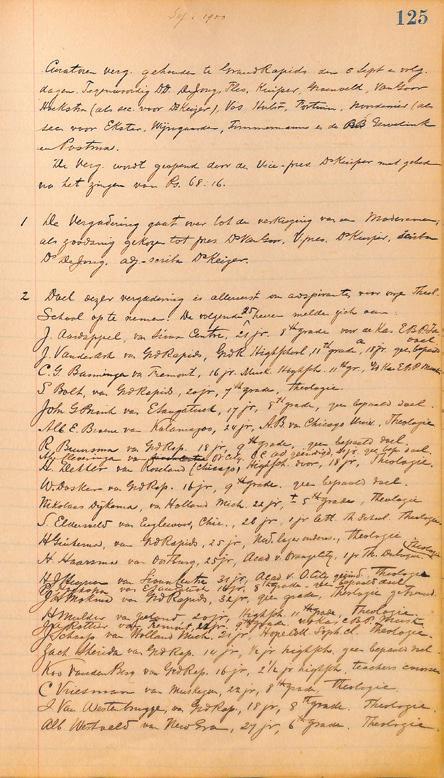

A turning point for the Theological School came in 1894 when the synod formally reorganized it and opened the literary program to students not intending to become pastors. None enrolled until 1900, however, the year when the Theological School formed its new Preparatory Department, with pre-seminary, classical, and scientific tracks. What had begun as a tiny theological training program was evolving into a broader institution; it was no longer just a seminary but it also included a high school academy that, over the next 20 years, would evolve into a liberal arts college. The 20th century thus opened with Calvin at a crossroads—built on a robust Reformed theological foundation, yet branching into literature, science, and the arts. The little parsonage school had laid groundwork for an enterprise serving both church and society.

By the early 20th century, the institution had firmly established itself, though its educational identity continued to develop. The first women enrolled in the Preparatory Department in 1901, many of them aspiring to be teachers in the CRC’s growing network of Christian schools, and the

Theological School added a junior college program, John Calvin Junior College (JCJC), in 1906. By 1908, JCJC was renamed Calvin College and, just a year later, the schools bought a property on Franklin Street and began to raise money for a new campus, where they finally moved in 1917.

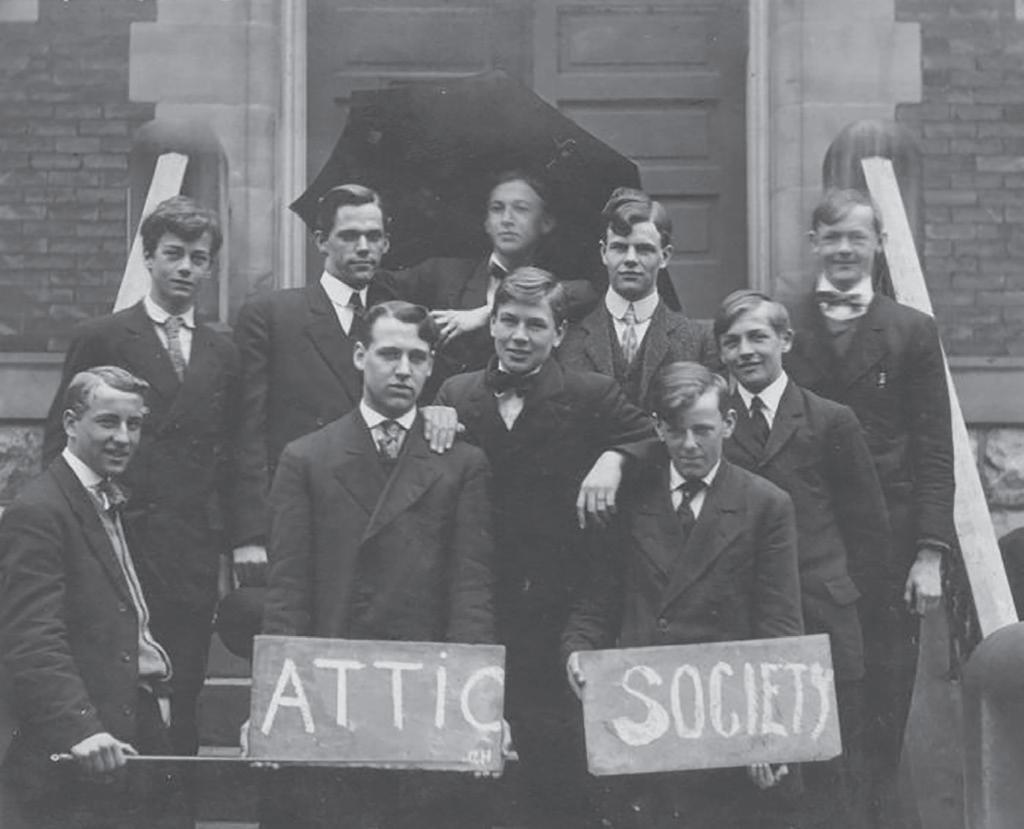

Also during the 1900s and 1910s, students organized clubs, informal sports teams, musical groups, and publications—among them Chimes, which is still Calvin’s student newspaper today. The student body continued on page 5

Future doctors, teachers, and chemists at work: early-twentieth-century science students in the Madison campus lab, where curiosity met calling.

continued from page 3

remained almost entirely homogeneous in this era, but the potential for the school’s mission to attract a more diverse student body can be seen even in those early days. The first international student, from Persia, entered the literary program in the 1890s; and, in the 1910s, Calvin enrolled its first Chinese and Navajo students. Students from other ethnic backgrounds and nations followed in subsequent decades.

Throughout these years, the denomination’s clear commitment to the college signaled its belief that all areas of study, not only theology, fell under Christ’s lordship. Calvin College began awarding occasional bachelor’s degrees in

1913 for students who completed the college’s three-year program and then sufficient coursework in the Theological School program or at another school. By 1920, dozens of students had earned these ad hoc degrees and, the following year, the college launched a full four-year bachelor of arts program, awarding its first regular BA degrees in 1921. During these years, the college also organized its faculty into distinct academic departments, mirroring other American universities while infusing courses with Reformed perspectives. In addition to ministers, Calvin was now producing graduates fully grounded in a Reformed Christian worldview who became educators, writers, nurses, university professors, businesspeople, and myriad other professionals.

Calvin College’s programs thus answered the evolving needs of the Christian Reformed community. As one early advocate wrote, “We need a school to which we can confidently entrust our sons and daughters, so that they will not be drenched in the poison of all kinds of errors.” The ethos was protective—providing safe Reformed education in an America whose public institutions were perceived as religiously compromising—but it was also constructive, giving Dutch immigrant youth paths into mainstream vocations. And so the college and the seminary continued to grow alongside one another, still sharing one campus and one board.

Academically, these decades saw Calvin step into a

broader arena. Under President Johannes Broene in the late 1920s, Calvin College earned formal accreditation from the North Central Association of Colleges, marking its acceptance into the ranks of established American colleges and universities. The curriculum increasingly reflected Abraham Kuyper’s vision of integrally Christian scholarship. Faculty members, some trained in the Netherlands and directly influenced by Kuyper and others trained in American schools, taught according to Augustine’s maxim that “all truth is God’s truth” and brought a Reformed approach to every discipline.

In 1930, the two schools became known as Calvin College and Seminary and, in 1931, Louis Berkhof became the first leader of the seminary with the title of president. By this time, prospective ministers were generally expected to earn a college degree before entering the graduate divinity program, and most did so at Calvin College. Seminary professors produced influential textbooks in subjects such as Bible, theology, and church history for the growing Christian Reformed Church, even as they navigated theological controversies that occasionally roiled the denomination, the seminary, and the college. Through these challenges, Calvin’s faculty and students remained grounded in the Reformed confessions—the Heidelberg Catechism, Belgic Confession, and Canons of Dort—that had inspired the school’s founding. Classes and daily chapels fully transitioned to English by the end

of the 1920s, a gradual but decisive shift in integrating the college into American life.

Culturally, Calvin navigated two world wars during this period. World War I tested the loyalties of a DutchAmerican campus; Calvin men served in the U.S. Army, and the war spurred further Americanization and the broadening adoption of the English language, a process completed after World War II. The interwar years brought steady growth, with Calvin’s combined enrollment hovering around 450 by 1930. Women had become a regular part of the student body, though rules governing their dress and conduct remained characteristically strict, more so than for men, in line with CRC and conventional American mores.

The Great Depression strained finances in the 1930s; faculty took pay cuts and students sometimes paid tuition in produce. Yet Calvin persisted, even expanding its Franklin Street campus with a new library and classroom building in 1938.

When the United States entered World War II in late 1941 and early 1942, dozens of Calvin students and alumni enlisted in the armed forces, some seeing combat in Europe and the Pacific. On the home front, the college participated in the government’s Army Specialized Training Program, accelerating courses for enlisted trainees. The war’s toll was keenly felt as Calvin community members were lost in battle, but it also broadened Calvin’s horizons. In 1945, as the war ended, Calvin stood poised for dramatic change. It had evolved from a tiny Dutch seminary into two connected and complementary institutions serving the Christian Reformed community and beyond. Veterans among students and the faculty returned more confidently American and with experience of the wider world, and the G.I. Bill flooded the campus with new students.

The quarter century after WWII brought explosive growth and transformation to Calvin. Veterans bolstered enrollment almost immediately and, by the 1950s, incoming student classes were double or triple the size of pre-war cohorts. The Franklin Street campus—an assemblage of brick buildings in the city’s Oakdale neighborhood—soon proved inadequate. Under College President William Spoelhof (1951–1976) and Seminary President John Kromminga (1956–1975), Calvin embarked on a bold plan: relocating to a new, expansive campus on Grand Rapids’ outskirts. In 1956, Calvin

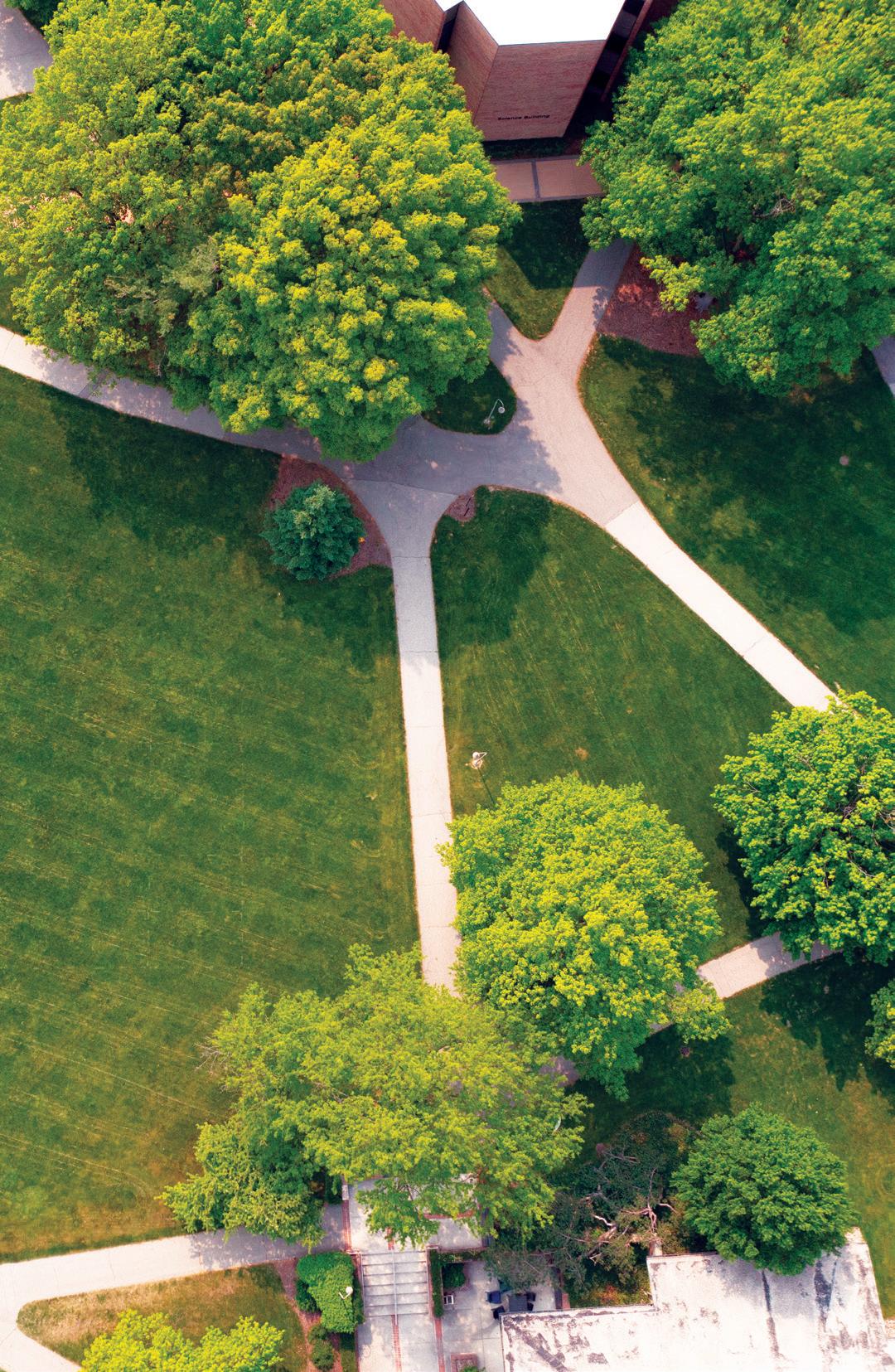

purchased the Knollcrest Estate, a 166-acre tract of rolling farmland that would be transformed into a modern campus over the next decade.

Spoelhof commissioned architect William Fyfe, a Frank Lloyd Wright protégé, to design a cohesive campus reflecting Calvin’s Reformed Christian ethos. Fyfe’s plan clustered academic buildings around a central quadrangle and residence halls around a secondary green, embodying a vision of integrative learning in community. Calvin Theological Seminary was first to move to the new Knollcrest campus in 1960, relocating to a newly constructed building on the property’s east side, complete with classrooms, offices, and a temporary library—an intentional step to anchor the campus in theological education from the outset.

Calvin College began its phased move shortly thereafter. By 1962, the first college buildings were completed, and departments gradually transferred from Franklin Street, mostly completing the process by 1970. The Knollcrest campus, with its signature low-rise “Calvin brick” architecture and Prairie-style horizontal lines, was the physical manifestation of Calvin’s second coming of age: a forward-looking educational village rooted in Christian principles, yet engaged with contemporary design and pedagogy.

Enrollment and programs surged during these years. Calvin College grew from a few hundred students in 1946 to over 3,000 by the mid-1960s, adding departments such as engineering, psychology, sociology, and art.

The seminary likewise grew, from 56 students in 1945 to 117 in 1952 and 178 in 1965. It also expanded its offerings for advanced study and welcomed a steady number of students from outside North America. Notable among these were students from Korea and Japan. They typically came as pastors with divinity degrees, seeking further graduate education. They often became leaders in their churches, universities, and seminaries back home. The relationships the seminary developed during these years would pave the way for Korean-American congregations in the CRC in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. They foreshadowed how the student bodies of the seminary and college both would become truly global by the 2010s.

Both institutions experienced shifts in campus culture during this period. The late 1960s brought societal turbulence associated with the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, and the counterculture, and Calvin’s students were not immune. A new generation pressed for reforms in American life and on campus. Mandatory daily chapel services became voluntary by the 1970s, and strict rules regarding curfews and dress codes gave way to a more open atmosphere. Despite these changes, Calvin’s spiritual life remained vibrant. Chapel still drew faithful attendance as it pioneered new worship forms, including student-led contemporary services complementing the traditional liturgies.

The mid-20th century also saw Calvin increasingly engage broader culture. The Reformed Journal, an intellectual magazine founded by Calvin faculty and CRC ministers, gained national readership in evangelical and Reformed circles during the 1960s. By 1970, Calvin was enrolling more and more students from outside the CRC, including students of color (with the first African-American student graduating in the 1960s). The college soon established programs to recruit and support minority and international students, and these efforts brought an increasing diversity in the following decades. The seminary, too, became more diverse and global, hosting visiting scholars from abroad and incorporating global missions into its training.

Presidents Spoelhof and Kromminga worked in tandem during this pivotal era, coordinating shared resources and

championing a Reformed Christian worldview that could hold its own alongside secular academia. By 1972, Calvin College had matured into a comprehensive Christian liberal arts college with national recognition, and Calvin Theological Seminary had weathered cultural upheavals while deepening its academic rigor and Reformed identity.

The late 20th century brought both increased stature and new challenges to the institutions, as they strove to remain faithfully Reformed while engaging the rapid religious and cultural changes occurring in the United States. Under College President Anthony Diekema (1976–1995) and Seminary

President James A. De Jong (1983–2001), Calvin gained a reputation as a center of Christian thought leadership.

Calvin College’s faculty produced scholarship that enhanced the school’s profile, while the college regularly ranked among top Midwest liberal arts institutions and influenced Christian higher education nationally through founding membership in the Christian College Consortium. The college also launched the January Series in 1987, bringing renowned speakers and discussions to campus each winter and further raising the institution’s profile. Similarly, the seminary hosted the Stob Lecture Series and extended its influence through faculty as well, whose writings reached far beyond denominational audiences.

Amid these achievements, Calvin faced significant challenges. The Christian Reformed Church from the 1970s to the 1980s again wrestled with doctrinal and social issues that inevitably affected its educational institutions. A major debate concerned women’s roles in church offices. For most of Calvin Seminary’s history, women could not be ordained as CRC ministers. Thus, while female students had enrolled in the Preparatory Program since 1901 and the college program since 1906, the seminary did not see women in its master of divinity and theological programs until the 1970s, albeit with uncertain futures. By the late 1980s, however, the CRC was moving toward opening all church offices to women, a change formally adopted in 1995.

Calvin Seminary prepared for this shift by admitting women who were called to ministry. These tensionfilled years were navigated with remarkable grace on campus: male seminarians who opposed women’s ordination were challenged to reexamine scripture and

tradition, while women preparing for ministry demonstrated spiritual integrity despite the controversy about their very presence on campus. In 1990, the seminary celebrated as several female students graduated; and, by 1991, Ruth Hoffman became the first woman candidate for ministry in the CRC, ordained in 1996.

Culturally, Calvin College students experienced an institution increasingly engaged with the world beyond not just its campus borders and denomination but North America. The college intentionally recruited students from racial and ethnic minority groups and city residents, adopting an official statement on racial reconciliation in 1985. Study-abroad programs expanded to multiple continents, reflecting Calvin’s growing international outlook. The arts and athletics flourished. Music ensembles toured nationally and internationally, while Calvin Knights teams began winning NCAA Division III national titles, demonstrating that competitive sports could be pursued to God’s glory.

A pivotal institutional change came in 1991. After years of operating under one umbrella, the Christian Reformed synod approved formally separating Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary into independent institutions, each with its own board of trustees. This practical decision acknowledged that both had grown too complex for unified governance. President Diekema noted that a single board had become “unwieldy” in addressing each institution’s unique challenges. However, this was not a divorce but an evolution of structure. The college and seminary continued to affirm their shared history, mission, and Reformed perspective, remaining neighbors on the Knollcrest campus and continuing collaboration through joint use of the Hekman Library, Meeter Center archives, and other resources.

The subsequent three decades brought both continuity and change as Calvin Theological Seminary and Calvin College embraced a more global vision. The 1991 separation enabled each institution to innovate while maintaining their longstanding partnership. Calvin College immediately began to strengthen diversity initiatives—then, in 2004, it issued From Every Nation, a comprehensive plan for racial justice and multicultural enrichment. Progress was gradual but significant: By the 2010s, Calvin’s student body included learners from all 50 states and dozens of countries. People of color from the United States and international students had grown to a quarter of the student population.

The seminary experienced even more dramatic internationalization. By the early 2000s, nearly 50 percent of Calvin Theological Seminary’s enrollment comprised international students from over 20 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Latin America. Where once seven Dutch young men sat in G. E. Boer’s classroom, now students from Korea, Kenya, or Brazil might debate theology in their own languages. The seminary community began celebrating global cultures, transforming into a living laboratory of global Christianity that enriches discussions and extends an impact worldwide. Graduates now serve not only in the CRC in North America but in churches and ministries from a variety of Christian traditions across continents, truly making Calvin a servant of the global church.

Calvin College continued expanding its academic profile and programs through new centers and institutes. The Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, founded in 1997 in collaboration with the seminary, began hosting annual

symposia, drawing thousands globally. The Festival of Faith & Writing, launched in 1990, brought international attention as authors explored intersections of literature and faith. In professional fields, Calvin added important offerings: new concentrations in undergraduate professional programs such as business and engineering, and new graduate programs in areas from speech pathology and audiology to accounting, media and strategic communication, and geographic information science.

In 2019, Calvin College became Calvin University, reflecting its new status as an institution with multiple graduate programs and distinct academic schools. This transition included reorganizing into schools and structural enhancements to support graduate education and promote research. University leadership emphasized that the name change amplified rather than altered Calvin’s mission to “integrate faith and learning across the full spectrum of academic disciplines” while inviting wider participation in its educational offerings.

Calvin Theological Seminary has likewise innovated in the new millennium, introducing distance learning for global accessibility and launching initiatives like the Center for Excellence in Preaching to provide resources worldwide. Campus renovations embodied the seminary’s forward-looking outlook while serving a changing church. Following the CRC’s decision to ordain women, female enrollment in the seminary’s MDiv program climbed steadily; by 2000, nearly a quarter of students were women. The seminary further deepened global Reformed scholarship engagement through initiatives like the Herman Bavinck Institute.

As Calvin Theological Seminary and Calvin University celebrate their 150th anniversary in 2026, their

transformation from a one-room, one-professor seminary into two internationally recognized and engaged institutions reflects a legacy of bold vision and enduring faith. Anchored in the conviction that “our world belongs to God,” they continue to integrate rigorous learning with deep spiritual

formation. Calvin’s first 150 years tell a compelling story of faith, learning, and renewal—a narrative still unfolding as Calvin confidently strides into the future, guided by the same “hearts promptly and sincerely offered to God” that inspired its humble beginnings. n

We certainly have exceptional reasons to acknowledge the Lord, to raise the Soli Deo Gloria to the praise of God alone. . . . What we then could not have expected, God has done for us and others, and that is the reason we repeat emphatically, ‘Soli Deo Gloria.’

—Geert Egberts Boer, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Calvin in 1901