JOURNAL

FOR PROFESSIONALS WORKING IN SAFEGUARDING AND CHILD PROTECTION

SAFEGUARDING AND CHILD

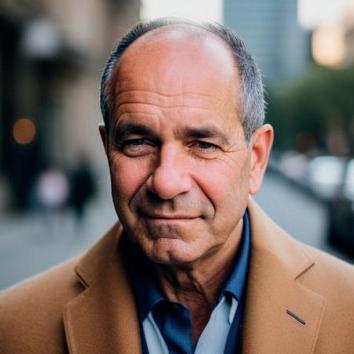

DR MARIYA ALI DIRECTOR, SACPA

Mariya is an internationally recognised safeguarding and child protection expert with more than 30 years of experience across advisory, academic, legal and leadership roles. She previously served as Deputy Minister in the Maldives, leading national reforms in child protection, and has worked with UNICEF, Save the Children, and Lumos on developing protection systems globally. With qualifications in human rights, social work, and traumatic stress, she has published widely on child rights, online safety, and trauma-informed safeguarding. Known for her strategic vision and practical expertise, Mariya brings both global insight and local implementation experience to SACPA.

Welcome

It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to this edition of the SACPA Journal, my first as Director since joining the association in August 2025. I am honoured to step into this role and to support our vibrant community of safeguarding and child protection professionals at such a pivotal time.

This journal brings together a diverse range of perspectives on the evolving safeguarding landscape. Our contributors examine pressing questions such as how much safeguarding is too much, the importance of allyship, and the unique challenges faced in

higher education. We also look at the role of parents, the realities of online safeguarding, and the impact of overscheduling children with activities – all issues that sit at the heart of safeguarding practice today.

At SACPA, we are committed to fostering open dialogue, sharing expertise, and supporting all those who hold responsibility for the welfare of children and young people. I am deeply grateful to our authors for their insights, and I hope you find this journal both thought-provoking and practical in your work.

Sponsored by

ANDREW HAMPTON CEO, GIRLS ON BOARD AND WORKING WITH BOYS

Andrew is an author and wellbeing specialist. He empowers girls to navigate friendships and supports boys in adopting compassionate masculinity, drawing on 18 years’ experience as a headteacher.

Safeguarding:

how much is too much?

Statutory guidance has grown so much in volume and complexity over the last 20 years that the responsibility for safeguarding pupils – and all members of the school community – has become very difficult to manage. While schools have significantly expanded their provision to safeguard pupils, the extra-mural services – such as psychological, psychiatric, speech and language, and SEND diagnostic support – have not kept pace.

Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSiE) is the most significant of the many guidance documents issued by the Department for Education (DfE) to keep children safe in England. It defines safeguarding as, ”taking action that promotes the best outcomes of all children”. Every year KCSiE is revised and new sections and paragraphs are added. A close examination of KCSiE (2023) reveals that, in addition to its 166 pages, there are 77 recommended websites to visit for more information, and more than 2,100 pages contained in downloadable PDFs. It is hard to believe that even the most proficient safeguarding professional has read all this material, or could boast a comprehensive recall of every detail.

The guidance has become so complex that you could argue that it is – very ironically – not clear

enough to be safe. For example, I have visited hundreds of schools in the last few years in my capacity as a trainer of teachers, and I have found that, despite all those thousands of pages of guidance, the interpretation and application of safeguarding protocols for visitors is inconsistent.

In some schools, I am free to wander unaccompanied down a corridor with a red visitor’s lanyard with no ID, yet in other schools my photo ID and Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) status are checked and recorded, and I am accompanied by a staff member for every moment of the day.

BATTLING AGAINST THE ‘MYTH OF MORE’

The principle seems to be that more words within a policy will make us safer, and more training on safety measures will reduce the incidents of harm. Maybe that’s true, but what are the unintended consequences?

The labour costs involved in safeguarding interventions are substantial – every school has a Designated Safeguarding Lead (DSL) and that person is usually a Deputy Head. The DSL often spends several hours a week on safeguarding issues and that has a knock-on effect on their ability to perform other senior leadership duties. As a result, more Assistant Heads are employed,

and it all costs money. School budgets have not expanded to meet the additional needs of safeguarding, meaning that schools have less money to spend on everything else.

Another unintended consequence of safeguarding is felt in the loss of freedom for pupils and staff. The security arrangements in some schools are oppressive and feel like you are entering a prison, guarding a precious and vulnerable set of inmates from predators who may come from any walk of life and attack at any moment. I therefore ask: how far has our extreme aversion to risk caused greater levels of anxiety in pupils, de-skilled everyone in the school community and promoted learned helplessness in children?

USING RISK ASSESSMENTS TO ENHANCE RESPONSES TO SAFEGUARDING CONCERNS

Safeguarding is focused on safety and is therefore an extension of the conceptual edifice of ‘Health and Safety’. Over the years, society has honed its ability to root out unsafe practices in every walk of life and make things safer. There are fewer people falling off ladders or being maimed or killed in relatively minor car accidents. But even the most zealous health and safety expert would admit that there is a diminishing rate of return. It is not possible to make all aspects of life entirely safe and that’s why we have risk assessments: to understand how we can mitigate risk and reduce harm. A good risk assessment will always consider the unintended consequences of mitigations, and that is something schools could do better.

In relation to safeguarding, we need a more calibrated and triaged approach. KCSiE already recommends a three-step response with Early Identification and Intervention leading to Escalation of Concerns and finally Multi-Agency Cooperation However, it is in the first stage –Early Identification and Intervention – that DSLs, understandably, tend to over-react for fear of being accused, later on, of under-reacting. There is no reason why an individual school shouldn’t take the opportunity to create a new labelling system that sits within the umbrella of safeguarding, but which allows practitioners to calibrate the seriousness of the concern being raised. In particular, a risk assessment should be

the initial response to every report of a safeguarding concern, and on the risk assessment pro-forma should be the question: “What are the potential unintended consequences of every possible planned.

THE PREVENTION CURRICULUM

Schools put a lot of thought into lessons and assemblies that focus on keeping pupils safe in both the real and digital world. In primary schools it is appropriate to teach pupils how to be safe, to warn them of danger, how to recognise it and therefore avoid it. Teenagers, however, can be counter-suggestive and messages are far more effectively delivered using guided reflection as the pedagogical style.

For instance, a good way to discourage sexting is not to over-emphasise the illegality of the practice but to guide pupils to reflect empathetically on how violating and traumatising it can be to receive when unsolicited. The reality is that local police forces are very reluctant to criminalise teenagers for these activities, and the best way to prevent it from happening is to promote self-regulation. The curriculum needs to focus on the dignity and power of self-control, looking at the benefits of mutually respectful behaviour for both the individual and cohort.

Safeguarding has become a permanent part of running a school and statutory guidance will no doubt continue to grow in volume and complexity. That doesn’t mean that the people running the school should not consider carefully how to safeguard the school community in the most efficient way and apply strategies that minimise cost and unintended consequences. Above all, DSLs need to calibrate, triage and identify what is and what isn’t a safeguarding issue and have the confidence to trust their judgment.

References

iRSPH (2025) The Top 10 Health Achievements of the 21st Century. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/top20-public-health-achievements-of-the-21stcentury.html

DONNY MCCORMICK DIRECTOR, SAFEGUARDING HE

With extensive experience in senior roles across universities and the purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) sector, Donny specialises in creating responsive services and implementing safeguarding frameworks aligned with legislation and government guidance.

Safeguarding in higher education: where to start?

Context is important. Universities have always been more than just places of learning. They each have their own fascinating economy, idiosyncrasies, reputations and politics. Even their regulators are different (or non-existent) depending on which part of the UK they are based in.

However, one thing they certainly all have in common is their responsibility to safeguard their students. This expectation, often framed as a university’s ’duty of care‘, has become a national talking point, driven by multiple student tragedies, rising mental health needs, and the evolving perception of higher education. Currently, the landscape remains both complex and unsettled, with universities balancing legal ambiguity, strained public services and diverse student needs.

DUTY OF CARE

Currently, universities have no statutory duty of care such as those found in health, social care or school settings. Higher education is subject to a common law, or ’general’, duty of care. At its core, this is a legal obligation to act with reasonable care to prevent foreseeable harm. Determining whether a duty of care exists is complicated and there are several legal tests that can be applied

when challenged in court. Notably, the Caparo test outlines three elements that are required to establish a breach of duty of care where harm has occurred: foreseeability, proximity and standard of care.

For universities, these elements are not straightforward. Most students are legally adults, and the historical doctrine of in loco parentis, the idea that institutions act ’in the place of a parent’, is often mistakenly assumed. Instead, universities are expected to adopt a more nuanced role: supporting students through reasonable and proportionate measures without assuming parental responsibility. The tension between autonomy and protection continues to define debates about duty of care in adult environments.

This creates unique challenges for higher education institutions, which cater to diverse adult populations, but also under-18s. Unlike schools, where safeguarding duties are clearly codified, universities operate in a legally grey area, interpreting provisions from multiple laws which, in their drafting, did not consider university environments. This ambiguity can leave the institution, and staff, uncertain about when and how to act.

LEGAL COMPLEXITY AND PUBLIC SCRUTINY

Recent legal cases have sharpened the focus. The civil case of Abrahart v University of Bristol (and the subsequent appeal) was pivotal. The court ruled that the university breached duties under the Equality Act 2010 by failing to make reasonable adjustments for a student who disclosed a disability, though it stopped short of recognising a broader tort-based duty of care.

The case of Feder and McCamish v. The Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in 2023 established that there was indeed a duty of care owed to students by the university that could be breached where services are not delivered to a reasonable standard.

What followed were public campaigns pushing for statutory recognition of a university duty of care, citing preventable student deaths. Although Parliament rejected the proposal in 2023, alternative initiatives such as the Universities’ Mental Health Charter and the Higher Education Mental Health Implementation Taskforce have gained some traction. Nevertheless, uncertainty remains, with universities often ’holding the risk’ in the most complex cases, even where statutory agencies have been informed.

CONFIDENTIALITY AND DATA PROTECTION

Adding to the challenge are the strict requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Universities must balance the need to protect privacy with the obligation to report safeguarding concerns. Article nine of GDPR allows data sharing if it is in the “vital interests” of the individual, but the staff interpreting these requirements are typically not lawyers, social workers or clinicians.

The priority, as many safeguarding professionals stress, is that data protection should never become a barrier to protecting life. Despite this, the heavy-handed approach to the embedding of GDPR has instilled anxiety across sectors regarding the consequences of data breaches. Misunderstandings of data protection between sectors and services remain a significant contributor to failures in protecting those that are at risk. There is also the persisting complexity regarding the role of parents in such circumstances where the student is over 18.

MENTAL HEALTH AND STRAIN ON PUBLIC SERVICES

Reports show a sharp rise in students disclosing mental health challenges over the past decade. Universities have responded by expanding counselling services and establishing mental health advice teams. These developments have made support more accessible, but they have also blurred boundaries between what universities should provide and what they must provide.

A critical issue is the strain on such statutory services. Access to NHS mental health care and adult social care varies widely across the UK, a postcode lottery of access. Some regions offer highly responsive support, while others struggle with long delays or a lack of response altogether. In practice, universities have absorbed more responsibility as external services have become overstretched. Yet, as non-clinical environments, they cannot – and should not –replace the role of statutory health and social care. Building strong relationships with safeguarding partners is essential but resource intensive, and there is no guarantee that safeguarding partners will engage at all.

WATCH THIS SPACE

The complexity of safeguarding in universities cannot be overstated. Institutions operate within a patchwork of laws, public expectations, and resource constraints. Guidance is limited and, as public services struggle, boundaries of institutional responsibility remain blurred, increasing the risk that universities will be held accountable for areas traditionally managed by the NHS or social care.

The way forward requires both clarity and investment. Clearer guidance, better-resourced public services, and potentially a requirement for partnerships between universities and local authorities would provide consistency and confidence for staff and students alike. As the government debates budgets and reforms, it is worth noting that safer, better-supported universities depend not only on institutional action but also on the resilience of the wider public sector.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SKYLER MOULDER LEAD NURSE AND DDSL, THE LEYS SCHOOL &

SENIOR NURSE ADVISOR, AND ADVISORY BOARD MEMBER, HIEDA

Skyler is an experienced community school nurse with an MSc in public health nursing. She is also a Deputy DSL and Mental Health First Aider, drawing on her training in CAMHS and safeguarding children.

Partnership working in health and safeguarding

The role of health professionals in schools has developed considerably over recent years. From the ‘nit nurses’ of the 1940s, to the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) implementation of an official School Nurse qualification in 2004, the role has developed and grown in line with the changing needs of young people (BBC, 2013; RCN, 2019). Safeguarding is now a crucial part of the School Nurse role, and School Nurses are well equipped to identify risk in young people (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, 2023). There are fantastic examples across the country of skill mixes in schools, with nursery nurses, first aiders and support workers delivering healthcare to pupils in educational settings. All professionals working closely with young people have the opportunity to protect them from abuse, neglect and exploitation. Key legislation and guidance help health professionals to understand their responsibilities in safeguarding children. There are several documents that are mandatory reading for health professionals in education, including Working Together to Safeguard Children Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSiE) and The NMC Code. This article will pull together the relevant legislation to focus on real-life examples of partnership working in healthcare and safeguarding.

WHY IS PARTNERSHIP WORKING IN SAFEGUARDING SO IMPORTANT?

Communication and information sharing are repeatedly identified as contributing factors in serious case reviews (NSPCC 2024), yet there are still areas where there is a lack of knowledge or confidence in information sharing between services. Several serious case reviews identified that health professionals were often unsure about what level of concern should prompt a referral to social care, or whether social workers should be challenged in the safeguarding arena. The Department for Education (DfE) Information Sharing guidance (2024) helps explain the legality of information sharing in the context of safeguarding children. As with Working Together (2023), the justification to safeguard a child is always enough for a proportionate, accurate and relevant disclosure of personal information to another service or professional, without the need for consent. In my experience, professionals sometimes avoid these difficult conversations with families, but they can be very valuable and consent should always be sought if the safety of the child, family or professional is not compromised. The discussion so far relates to the most serious outcome of poor partnership working: the death or serious injury of a child. However, there are various ways that outcomes can be improved for all aspects of a child’s wellbeing by building professional relationships with mental health and sexual healthcare services, GPs and community School Nurses and many more. The key word is relationships. Building relationships and connections with partner organisations and services will ultimately lead to better outcomes for

the children and young people we work with. The Adaptive Mentalization Based Integrative Treatment (AMBIT) approach gives a structure to mentalization approached partnership working (Anna Freud, 2024). The AMBIT approach works with the expectation that dis-integration or loss of connection can and will occur between professionals/services. We must acknowledge the imperfection in our systems and attempt to address them with techniques such as ‘thinking together’.

WHAT DOES THIS LOOK LIKE IN PRACTICE?

In practice, developing relationships between services can be challenging due to heavy workloads, time and geographical constraints. A good place to start is with the services you use regularly, such as CAMHS or other local mental health services, charities, sexual health clinics, GP practices and community School Nursing teams. How can you build connections with them so that each service understands the needs, criteria, referral pathways and structure of the others? GP surgeries tend to have a monthly practice meeting, so perhaps a School Nurse could attend to explain their role in the local school? They can identify how the two services can work together to meet the needs of children in both their care.

KOOTH is an online counselling service that is available to 85% of England and 50% of Scotland (KOOTH, 2025). KOOTH has outreach teams who deliver workshops to pupils and staff in schools. In this case and with other mental health services, School Nurses can register and receive newsletters, workshops and training from them. By doing this, you will understand their organisation, service offer

and referral criteria much more and ultimately improve the care you provide. The same could be said for charities who support young people with mental health, gender identity and sexuality, bullying, domestic abuse and so much more. This will vary by area, so go and have a look at what is available to you and your school.

The best relationships between health and the wider school are forged by having the School Nurse on the school safeguarding team. School Nurses have a sound understanding of confidentiality and often have direct experience of working in the child protection arena (RCN, 2017). Schools’ approaches vary in practice, but training a School Nurse as a Designated Safeguarding Lead (DSL) or Deputy DSL will create the best opportunities for information sharing and team-working to safeguard the children in your school. Nurses should have access to regular supervision in order to practice with confidence and to ensure that they have the opportunity for robust reflection and professional challenge (RCN, 2021).

CONCLUSION

The importance of information sharing and multidisciplinary working in safeguarding is well documented. By implementing the key legislation and guidance available, combined with some of the practical suggestions in this article, School Nurses can build their confidence and competence to work collaboratively in order to safeguard children. Addressing and managing interprofessional disintegration and conflict can ensure that we always keep the child’s best interests at the forefront of everything we do.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anna Freud (2024) AMBIT Manual. Available at: https://manuals.annafreud.org/ambit/

BBC (2013) Why are school nurses important? Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health22106939

Department for Education (2024) Information Sharing: Advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services for children, young People, parents and carers

Department for Education (2024) Keeping Children Safe in Education

HM Government (2023) Working Together to Safeguard Children. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/med ia/669e7501ab418ab055592a7b/Working_to gether_to_safeguard_children_2023.pdf

KOOTH (2025) Available at: https://www.kooth.com/

Local Government Association (2022) School Nursing: Looking after the health and wellbeing of school children

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2017) The Code. Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedo cuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf

NSPCC (2024) Learning from Case Reviews. Available at: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/researchresources/learning-from-case-reviews/multiagency-working-information-sharing

O

ffice for Health Improvement & Disparities (2023) Commissioning health visitors and school nurses for public health services for children aged 0 to19. Available at: Commissioning health visitors and school nurses for public health services for children aged 0 to 19 - GOV.UK

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2017) An RCN Toolkit for School Nurses

Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2021) Safeguarding Children and Young People –Every Nurse’s Responsibility

DELYTH LYNCH FTIOB DIRECTOR OF SAFEGUARDING, WELLINGTON COLLEGE AND EDUCATION

REPRESENTATIVE, SAFEGUARDING AND CHILD PROTECTION ADVISORY BOARD FOR SACPA

Delyth has more than 20 years' experience of teaching and senior leadership in UK boarding schools, the last decade of which have focussed on safeguarding and safer culture.

How we turned safeguarding challenges into

collaborative success

Effective teamwork in safeguarding is paramount for ensuring the best outcomes for vulnerable children and young people. When safeguarding professionals work together well, they create a robust support system that enhances decision-making, promotes continuous learning, and fosters resilience in the face of challenging situations.

I am very lucky to find myself working with a group of colleagues at Wellington who all look at safeguarding from different and diverse perspectives. Our core team consists of me, the Director of Safeguarding and DSL, the Safeguarding Manager, Deputy Head (Pastoral), Nurse Manager and Head of Student Emotional Health and Wellbeing. Our PA is also a crucial cog in our wheel: minute taker, tea maker, tears mopper upper, diary coordinator… there isn’t much she doesn’t support us with. We have a rather unique synergy – and one which is praised and commented on by those outside of our unit – but one area which continues to challenge is that of confidentiality and information sharing. What to share? Who to share with? When to share? When to break a young person’s trust by informing their parents? We sometimes found ourselves awkwardly pushing against one

another as conflicting roles meant differences of opinions and distinctive contrasts in our roles within the college.

We were all aware that the power of teamwork in safeguarding lies in its ability to create a safety net of shared responsibility. This is where no single professional bears the entire weight of critical decisions alone but where we could safely challenge one another and be curious around a comment being made or a certain viewpoint being expressed, particularly around the area of confidentiality. For a while, I have been listening to a podcast called You are not a frog. Primarily designed for healthcare professionals, particularly those in high-stress environments such as doctors and nurses, it focuses on providing strategies for managing stress, improving resilience, and enhancing work-life balance. I was immediately able to draw parallels between the two work environments and began to wonder if the ‘Shapes’ toolkit which was developed by the podcast’s host – Dr Rachel Morris – might benefit our team and enable the creation of a shared language to further enhance the way we communicated with one another, particularly where there were necessary differences of opinion.

Finding a day when we could all give seven uninterrupted hours of our time proved to be a challenge in itself. But we did and, several months on, we are all exceptionally glad we did as the impact has been profound and far reaching.

Firstly, it provided us with a common vocabulary to articulate our thoughts, feelings and approaches to safeguarding challenges. This shared language has become a cornerstone of our communication, allowing us to express complex ideas succinctly and with mutual understanding. One of the most profound impacts of the training, however, was the opportunity it created for vulnerability within our team. As we worked through the ‘Shapes’ exercises, we found ourselves opening up about our fears, uncertainties, and personal challenges in safeguarding and pastoral work. This vulnerability fostered a deeper sense of trust and camaraderie among team members.

The Shapes Toolkit has also been instrumental in helping us strike the delicate balance between professional challenge and support. We’ve learned to use the different shapes as metaphors for various roles we play in our interactions:

• The Circle: representing the ‘zone of power’, we have learnt to appreciate what we can directly control, but also consider how to leverage our collective and individual zones of power. This has allowed us to be more creative as a team and be more proactive by trying to influence and expedite decisions being made by others.

• The Hexagon: representing what hinders our productivity, the stressors hexagon required us to think more about our own stress levels and what we might be able to actively change to support longevity in our roles.

• The Corner: symbolising structure and boundaries, we employ this shape to respectfully challenge decisions and ensure adherence to best practices, as well as setting boundaries in our lives to ensure a healthy work-life balance. We have learnt to interrogate reality and step out of any corners which we may have inadvertently created ourselves.

• The Triangle: being already aware of the drama triangle, we were able to further relate Karpman’s thinking to ourselves and those we work alongside. We therefore moved out of the ‘game’, changing our roles and coaching others to change theirs to enact positive long-term change.

By incorporating the ‘Shapes’ methodology, we’ve enhanced our ability to approach safeguarding issues creatively. The toolkit has encouraged us to think outside the box, considering multiple perspectives and innovative solutions that we might not have explored previously.

Our team now operates with a level of cohesion and effectiveness that surpasses our previous performance. The shared experience of the training day itself was invaluable, filled with laughter, learning and the forging of stronger bonds among team members. In the weeks and months following the training, we’ve observed a marked improvement in our team’s resilience and productivity, and we believe that we have navigated complex situations with greater ease and mutual understanding. My personal goal was to set firmer boundaries, which is always hard in a boarding environment and with the ever-increasing emphasis on contextual safeguarding, but I now find myself at a pottery class every Thursday evening. Whilst I might not be the new Emma

Bridgwater just yet, I have begun to really value the quiet space and where I slip into a state of mindfulness. Nothing else can be thought about or else my pot ends up like a lopsided, wobbly monstrosity that looks more like a confused pancake than a vessel for holding anything.

We all find ourselves better equipped to handle the emotional toll of safeguarding and pastoral work, supporting each other through challenging cases while maintaining a positive and solutionfocused outlook. Perhaps most importantly, however, our enhanced teamwork has translated into more effective safeguarding practices. We’re making decisions more confidently, challenging each other constructively, and consistently placing the needs of vulnerable individuals at the heart of our work. The Shapes Toolkit has not just improved our professional and personal lives, it has reinvigorated our passion for safeguarding and our belief in the power of collaborative effort.

As we continue to face the ever-evolving challenges of safeguarding, all of us working with the field need to work together with a sense of purpose and unity. We are not just ‘colleagues’, we need to be able to lift one another like balloons, challenge each other to question our decision making and work tirelessly to protect those who need us most. Our training has meant that we are not just ‘coping’ but thriving and it has underlined our deep commitment to making a long-lasting difference to the lives of those we come to work for every day –the young people in our care.

FURTHER READING

The Shapes team have kindly provided a free resource for readers to access. This is a handout for the Zone of Power, which you might find useful to use with your teams:

• https://www.shapestoolkit.com/zone-ofpower-handout

• Podcast website: youarenotafrog.com Recommended episodes:

• Embracing Your Limits in a Limitless System

• How to Overcome the Toxic Effects of Shame on Your Team

• Why You Should Expect Pushback and What to do About it

REFERENCES

• Shapes Tookit (2025) Programmes & Trainings. Available at: https://www.shapestoolkit.com/programm es-and-trainings

• Karpman, S. B. (2014), ‘A Game Free Life’

GAELLE SULLIVAN MTIOB DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND INCLUSION, BSA GROUP & DIRECTOR, IELA

Gaelle is an experienced senior leader and has worked in a range of state and independent schools. She is a qualified SENCO and holds a Masters in Inclusive Education.

Impact of suicidal ideation on safeguarding professionals

Safeguarding professionals, particularly Designated Safeguarding Leads (DSLs), occupy some of the most emotionally demanding roles within our schools and child-focused organisations. They are the frontline guardians of children’s wellbeing, often tasked with supporting young people who experience suicidal ideation. To better understand the realities of this responsibility, SACPA conducted a survey with safeguarding professionals last year.

The findings paint a sobering picture of the challenges DSLs face, the personal toll of their work, and the strategies that help them to cope. They also highlight urgent systemic improvements needed if we are to safeguard not only our young people but also those professionals who choose this path.

The backdrop to this research is one of rising mental health difficulties among young people. NHS statistics from 2023 reveal that one in five children now has a probable mental health disorder, a steep rise from one in eight in 2017. Tragically, suicide rates among under-18s have also increased since 2014.

In response, safeguarding leads are seeing more young people presenting with suicidal thoughts. While many schools now have Mental Health Leads or DSLs dedicated solely to safeguarding, the majority of safeguarding professionals still

carry multiple responsibilities. This dual role compounds the pressure when crises emerge, especially when suicidal ideation is disclosed.

IMPACT ON SAFEGUARDING PROFESSIONALS

Our survey found that supporting suicidal young people has both immediate and longer-term effects on safeguarding professionals.

Short-term impacts: Nearly half (48%) reported disturbed sleep, 39% experienced physical fatigue, and 27% reported emotional distress. Anxiety affected 21% of respondents. Interestingly, 17% described desensitisation, a defence mechanism that can protect against distress but may also risk distancing practitioners from the very young people they seek to support.

Long-term impacts: While 37% said they do not experience lasting effects, a significant number reported persistent consequences such as anxiety (10%), physical fatigue (27%), disturbed sleep (25%), and emotional distress (14%). These are well-documented precursors to burnout and compassion fatigue.

Alarmingly, 31% of respondents admitted that the emotional toll and inter-agency frustrations had made them reconsider their safeguarding role altogether. For some, this was compounded by the absence of adequate managerial support

following particularly traumatic cases, such as student suicides.

BARRIERS TO WELLBEING

DSLs recognise the importance of prioritising their mental health, but many feel unable to do so.

Time pressures were cited by 63% as the main barrier.

Stigma remains an issue, with over 12% fearing they would be judged for prioritising their own wellbeing.

Workplace culture can exacerbate strain, with some respondents feeling obliged to “put on a brave face” despite mounting pressures.

These barriers not only risk individual burnout but also jeopardise the stability and continuity of safeguarding provision within settings.

COPING STRATEGIES AND SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Despite the challenges, many DSLs employ a range of coping mechanisms.

Supervision and counselling: Around a third (32%) have access to external supervision, while 40% receive internal supervision. Just over half

(51%) can access counselling services through Employee Assistance Programmes or in-house counsellors. Respondents consistently highlighted supervision as one of the most effective safeguards against the impact of their work.

Supportive teams: 65% reported having supportive colleagues and HR teams, which significantly reduced long-term negative impacts.

Personal coping strategies: Talking to friends and family (54%), engaging in hobbies (42%), and maintaining a healthy lifestyle (40%) were among the most common strategies. Meditation and mindfulness were also used by 21%.

However, 5% of respondents reported having no workplace support at all, and this group was more likely to experience anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

TRAINING AND PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

While 68% had received suicide prevention or awareness training – commonly through MHFA (Mental Health First Aid) or ASIST – several respondents noted that DSL training in mental health remains too superficial. Practical, scenariobased training was highlighted as an urgent need to better equip safeguarding professionals for the complexities they face.

Reflective practice also emerged as a doubleedged sword: while helpful as a form of debriefing, 38% reported often feeling they could have done more, which risks fuelling guilt and self-doubt unless balanced with professional supervision and reassurance.

CHALLENGES WITH EXTERNAL AGENCIES

A recurring frustration among respondents was inconsistent collaboration with external agencies.

Access to services: demand for NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) has risen dramatically, with referrals increasing from 520,000 in 2016–17 to over 1.4 million in 2023–24. Yet only 32% of referrals enter treatment, while 39% are closed before accessing

services. As a result, some DSLs reported that the only way to secure help for a suicidal child was by taking them to A&E.

Information sharing: many respondents described one-way communication and a lack of transparency around safety plans. Non-standardised referral systems also complicated matters, particularly for schools working across multiple local authorities.

Partnership with parents: while many parents were described as shocked but grateful when contacted, some conversations proved tense, particularly where parents felt exposed or judged.

Effective engagement, empathy, and clarity were highlighted as key in such circumstances.

These challenges often leave safeguarding professionals shouldering disproportionate responsibility for holding risk, intensifying their stress and anxiety.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

From the findings, several clear recommendations emerge:

1. Supervision must become standard practice for all safeguarding leads, across all types of schools and organisations.

2. Stronger managerial support is essential to buffer the emotional strain of safeguarding roles.

3. Time allocation must allow DSLs to balance both reactive crisis management and proactive preventative work.

4. Training beyond statutory requirements should be prioritised, focusing on practical strategies and mental health expertise.

5. Improved communication with external agencies is urgently needed, alongside clearer guidance on information sharing.

These changes are not simply desirable; they are necessary to safeguard the wellbeing of those who dedicate themselves to protecting children.

The role of the DSL has evolved significantly in recent years, shaped by changing mental health trends and a shifting safeguarding culture. While this evolution has increased responsibility and pressure, it has also underscored the critical importance of safeguarding professionals within our communities.

SACPA calls for systemic recognition of the emotional labour borne by DSLs and for concrete measures to sustain their wellbeing. If we neglect this, we risk undermining the very safeguarding system our children rely upon.

The research findings serve as a reminder that safeguarding is not just about protecting young people – it is also about protecting those who safeguard. To build resilience in our safeguarding workforce, we must ensure they are supported, trained, and valued. Only then can they continue their vital role with the compassion, clarity, and commitment that children deserve.

DR VAUGHAN CONNOLLY DIRECTOR, THE GLENLEAD CENTRE

Vaughan’s team bridges research and policy for a digital future. Vaughan contributes to international and national policy level discussions, for example on how school schedules affect exam results and staff retention.

Privacy and safety by design

Digital tools are now central to education, shaping how children learn, communicate, and socialise. This brings opportunity but also risk.

The Children’s Code (Age Appropriate Design Code), launched in 2020 and enforceable since September 2021, requires online services likely to be accessed by under 18s to embed privacy and safety by design. Yet awareness in schools and compliance among vendors remain low. Independent audits show that many apps used daily in classrooms fail to meet even basic safety standards, making the case for rigorous technical audits urgent.

THE CHILDREN’S CODE

The Code applies to all online services likely to be accessed by children, including apps, onlinegames, search engines, and streaming platforms. Its standards require services to:

• Act in the best interests of the child

• Provide high privacy settings by default

• Minimise data collection and retention

• Avoid profiling and targeted advertising

• Switch off geolocation unless necessary

• Present clear, age-appropriate information

• Avoid ‘nudge’ techniques that encourage oversharing

• Give children and parents control over data.

The Code is enforced by the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), which can investigate and fine non-compliant companies. For schools, this means any app, website or platform used by pupils must meet these standards.

The Code complements the Online Safety Act (2023) which regulated harmful content and user interactions. Together, the Code and the Act form a dual framework: one ensures safe design, the other safe operation. However, the Code will only be effective if schools and parents insist on compliant products. Unfortunately, awareness of the code is worrying low. In 2022, the ICO found that only 20% of parents and 20% of children were aware of the code and what it does.

Furthermore only 14% of service providers reported a detailed understanding of the code, while only 72% of teachers were aware of it.

Unfortunately, awareness does not guarantee compliance. Findings from Internet Safety Labs (ISL), a US-based nonprofit, reveal critical shortcomings in the design and deployment of US EdTech. These lessons offer a compelling case for UK schools to adopt more rigorous, designaware technical audits that interrogate the safety architecture of EdTech systems.

ISL FINDINGS

Independent audits highlight the scale of the problem. ISL analysed thousands of school recommended apps in the US and found widespread unsafe practices:

• More than 96% of apps share student data with third parties.

• 78% of apps were rated ‘critical risk’ due to unsafe behaviours (e.g. advertising, databroker software development kits (SDKs), data aggregators on Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, Adobe, etc).

• 18% were ‘high risk’ (e.g. data-aggregators on Apple or Google, high risk SDKs, use of WebView, dangling domains).

• Nearly 75% contained high-risk SDKs, often linked to advertising or tracking.

• Excessive permissions were common, with apps requesting permission to location data (73%), file access (73%), physical environment such as camera or microphone (65%), user behaviour (65%), and social information (52%).

• Many apps transmitted children’s data to third party companies, creating hidden data flows.

• Many apps did not live up to privacy and safety commitments made.

• Safety scores were poor even among apps widely promoted by schools and districts.

ISL’s methodology combined network traffic analysis, permissions audits, and SDK mapping. They analysed thousands of data points from 663 K-12 schools and 1,700 unique apps as recommended by schools for students and analysed the network traffic flows for more than 1,200 apps. The results show that unsafe design is not the exception but the norm. For schools, this means that simply trusting vendor assurances is not enough.

RISKS OF SDKS AND PERMISSIONS

A major concern is the use of SDKs. These are third party code bundles that developers plug into apps to add features such as analytics, ads, or social sharing. The risk is that SDKs can quietly collect and transmit children’s data to external companies.

Excessive permissions compound the problem. An app designed for homework submission, for example, should not need access to a child’s location, microphone, or contacts. Yet ISL found such permissions were routinely requested, creating unnecessary risks for profiling, surveillance, and potential exploitation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOLS

Schools have statutory duties under Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSiE) to safeguard children, including online. While KCSiE does not explicitly mention the Children’s Code, schools must still ensure that the apps and platforms they use comply with it. This means:

• Auditing apps and online services for compliance with the Code

• Demanding transparency from vendors about SDKs, permissions, and data flows

• Only adopting apps and services that meet privacy by design principles

• Training staff to understand privacy and safety standards

• Involving governors and safeguarding leads in procurement decisions.

The ISL findings make clear that many apps used in US schools today would fail a UK Children’s Code audit. Schools cannot assume that popular or widely recommended apps are safe.

CONCLUSION

The Children’s Code and the Online Safety Act together create a robust framework for protecting children online. But laws alone are not enough. Independent audits like those from ISL show that many apps fail to meet basic safety standards, requesting excessive permissions and embedding risky SDKs. For schools, this makes an urgent case for technical audits. By demanding transparency, auditing rigorously, and embedding privacy by design in procurement, schools can better meet their safeguarding duties and ensure that technology enhances learning without compromising children’s safety or rights.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ICO (2023) Children’s code evaluation. Available at: https://ico.org.uk/media2/aboutthe-ico/documents/childrenscode/4025494/childrens-code-evaluation-rep ort.pdf

ISL (2022) 2022 K-12 Edtech Safety Benchmark National Findings part 1. Internet Safety Labs. Available at: https://internetsafetylabs.org/wpcontent/uploads/2022/12/2022-k12-edtechsafety-benchmark-national-findings-part-1.pdf

Will smart phone bans keep children safe online?

ANDY PHIPPEN, PROFESSOR OF DIGITAL RIGHTS, BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY

Andy has worked with the IT sector for 20 years in a consultative capacity on issues of ethical and social responsibility, presenting evidence to parliamentary enquiries and being widely published.

Over the last year there has been increasing demand to ban children from owning smartphones or accessing social media.. Politicians and campaigners have called for raising the legal age for social media to sixteen, for prohibiting phones in schools, and even for manufacturing ’child-safe’ handsets that restrict internet access. These ideas resonate strongly with public anxiety about children’s exposure to bullying, pornography, grooming, and mental health pressures. On the surface, they offer a simple solution to what feels like an overwhelming problem.

But that simplicity is, of itself, deceptive. Prohibition does not equate to protection. Indeed, evidence suggests that bans may do little to reduce online risk. For those of us working in online safeguarding, the challenge is not only to protect children from immediate harm but also to build the conditions in which they can navigate digital spaces safely, responsibly, and with trust in the adults around them.

The fundamental problem with prohibition is that it fails to account for the realities of young people’s lives. Smartphones and social media are deeply woven into the fabric of

childhood and adolescence. For many children, the device is not simply a screen, it is a means of friendship, identity exploration, entertainment, and learning. Banning smartphones or delaying access to platforms may be perceived as the means to satisfy adult anxieties, but it does little to address the fact that children will continue to find ways to connect, often in ways that are harder to monitor or support.

It is also worth remembering that the legal power to restrict smartphone use in schools has existed for more than a decade. Since the Education Act 2011, headteachers have had the authority to regulate mobile phone use and even search and confiscate devices where necessary. More specifically, the Education and Inspections Act 2006 gave schools the power to search pupils without consent, but only for a narrow list of ‘prohibited items’ such as weapons, alcohol and illegal drugs. While

mobile phones were not included, schools had powers to ban them in their behaviour policies. However, they had weaker legal backing to enforce those bans. The Education Act 2011 strengthened these powers by allowing headteachers and authorised staff to search for and confiscate any item banned under the school’s rules. This expansion gave schools clear authority to include mobile phones on their prohibited items list and enforce wholeschool bans. It was down to individual decisions by senior leaders and boards to decide the best course of action in their settings.

In that sense, the recent calls for ’tough new bans’ in schools ring hollow. They are not introducing new powers but re-stating what has already been possible since 2011. Or do those who are proposing new powers not understand existing legislation? This makes the renewed political interest feel performative: a way of signalling decisive action to the public rather than addressing deeper challenges in practice.

Prohibition can also erode trust. When adults impose blanket bans, children might learn to conceal their online activities. This undermines disclosure: if a child experiences bullying, exploitation, or other harm online, they may be less likely to seek help from adults if they fear punishment. Safeguarding depends on openness, yet prohibition tends to drive behaviours underground.

POLITICAL THEATRE AND MORAL PANIC

The appeal of prohibition lies as much in politics as in safeguarding. Calls to ban smartphones often arise during moments of public concern, fuelled by media narratives about suicide games, pornography epidemics, or the purported catastrophic effects of screen time. These stories are compelling, but they are also frequently exaggerated, taken out of context or do not stand up to scrutiny.

Such narratives create moral panics that push policymakers towards symbolic solutions. A ban is highly visible; it reassures the public that ‘something’ is being done, regardless of whether that something is effective. Yet these measures often amount to little more than political theatre. They create a sense of urgency and control without addressing the underlying causes of harm, such as inadequate digital literacy education, underfunded mental health services, or the absence of trusted adult support.

Another function of prohibition is that it shifts risk rather than reducing it. When governments legislate for bans, responsibility for managing children’s online lives is effectively pushed onto schools, parents, or platforms. This relieves the state of deeper obligations – such as investing in family support services, child and adolescent mental health, providing comprehensive digital literacy education, or ensuring that safeguarding professionals are well-trained to deal with online issues.

While a ban on phones in a classroom is perfectly reasonable, blanket bans do not eliminate online risk; it merely displaces it from the school setting into children’s bedrooms, streets, and social gatherings. Similarly, raising the age of access to social media may exclude children from legitimate opportunities for learning and connection, while doing little to stop determined teenagers from bypassing restrictions. The risk does not disappear, it just becomes less visible to adults.

But perhaps the greatest danger of prohibition is that it can create complacency. If we believe that banning smartphones or restricting platforms will solve the problem, we may neglect the harder but more necessary work of education, empowerment,

and trust-building. Children need to know how to recognise risks, how to manage their digital footprints, how to seek help, and how to support one another. None of this is achieved by confiscating devices.

The false sense of security is particularly damaging for safeguarding professionals. When institutions adopt prohibitionist policies, staff may assume that risk has been eliminated, rather than recognising the ongoing need for vigilance, conversation, and support. This illusion of safety can leave children more exposed when harms inevitably occur.

TOWARDS EFFECTIVE SAFEGUARDING

What, then, should be done? A more effective approach starts with recognising the complexity of children’s digital lives. Online safety cannot be achieved through blunt prohibitions; it requires strategies that engage children, families, schools, communities, and platforms.

First, education must be prioritised. Children who are equipped with digital literacy skills, such as critical thinking, awareness of privacy and strategies for resilience, are better able to navigate risks than those who are simply shielded from them. Education must extend to parents and professionals too, who need confidence in guiding children without resorting to fear or punishment.

Second, safeguarding must be relational. Children are far more likely to disclose harm to trusted adults if they feel heard and supported. Building environments of openness, empathy, and trust is far more protective than punitive restrictions.

Third, we must strengthen the wider ecosystem. Safeguarding does not rest solely on platforms or schools. Social services, mental health provision, NGOs, and government all have roles to play in ensuring that support is available and accessible. Collaboration across these stakeholders is essential if we are to move beyond prohibition and towards genuine protection.

CONCLUSION

Smartphone bans and similar prohibitive measures offer political spectacle but little safeguarding substance. They distract from the hard work of building resilient systems, educating young people, and addressing the complex social dynamics of digital life. Indeed, the fact that schools have had the power to ban smartphones for years suggests that current political calls are less about introducing real solutions and more about performing concern.

For safeguarding professionals, the way forward lies in rejecting simplistic bans and embracing holistic, child-centred strategies that empower rather than restrict. By listening to young people, equipping them with skills, and strengthening the networks of support around them, we can build an approach that is realistic, respectful, and genuinely protective.

Because the truth is this: keeping children safe online is not about banning the technology they use. It is about preparing them, supporting them, and trusting them to navigate the digital world they will be unable to avoid as they grow older, with resilience and confidence.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fyfe, W. (2025) Teachers urge parents not to buy children smartphones. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cwyxggv9j9zo

Lavelle, D. (2025) UK police chiefs call for ban on social media for under-16s. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2025/apr/12/uk-policechiefs-call-for-ban-on-social-media-for-under-16s

UK Parliament (2025) MPs to debate a petition relating to a minimum age on social media. Available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/326/petitionscommittee/news/205317/mps-to-debate-a-petition-relatingto-a-minimum-age-on-social-media/

Topping, A. (2025) Fathers plan legal action to get smartphones banned in England’s schools. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/jul/13/fatherslegal-action-smartphone-ban-england-schools

Phippen, A. (2024) Should you give your child a ‘dumb’ phone? They aren’t the answer to fears over kids’ social media use. Available at: https://theconversation.com/should-you-giveyour-child-a-dumb-phone-they-arent-the-answer-to-fearsover-kids-social-media-use-238129

Odgers, C. (2024) The great rewiring: is social media really behind an epidemic of teenage mental illness? Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00902-2

Phippen, A (2025) Policy and Rights Challenges in Children’s Online Behaviour and Safety, 2017–2023, Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-80286-7

Setty, E. (2022) Online safety: what young people really think about social media, big tech regulation and adults ‘overreacting’. Available at: https://theconversation.com/online-safety-what-youngpeople-really-think-about-social-media-big-tech-regulationand-adults-overreaching-196003

Bond, E. & Phippen, A. (2019) Digital Ghost Stories; Impact, Risks and Reasons. Available at: https://swgfl.org.uk/research/digital-ghost-stories-impactrisks-and-reasons/

ADAM TESCHNER UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT, UNIVERSITY OF EAST ANGLIA

Loving the limits: a snapshot of a guided adolescence

Secondary school was where I really started to come out of my shell.

Reflecting on my seven years at City of London Freemen’s School now, as a 20-year-old university student, I can confidently say this metamorphosis was beautiful. I was finally making deeper sensitive friendships, exploring passions enough that I felt confident pursuing them into my career, receiving grades I felt accomplished with and enjoying the challenge of getting them. This all sounds great on paper, but this journey of finding your own space in adolescence does not always have a happy ending. In fact, those very acts I listed –making new friends, exploring passions, revealing your true self – can easily steer you down the wrong path. As organic as

my metamorphosis felt, it is undeniable that my environments, both at school and at home, were products of careful construction and intentionality.

Freemen’s was always firm with online safety. We would get the regularly mandated online safety courses that were held during the school day instead of afterwards, so students couldn’t skip them, and these were sent to all the parents too.

Of course, this gave the parents more peace of mind about their child’s safety, but I think what’s more crucial is that we would have a common knowledge base with our parents instead of having to tell them everything ourselves. Some notable warnings were on content, for example no watching 13 Reasons Why or playing Blue Whale.

Hiding these entirely from kids seemed better than explaining their harmfulness, otherwise how would we know what a safe and comfortable world looks like?

A lot of trust was placed in our parents to be active in setting these limits in the home. Beyond that, I had to have a lot of trust in my parents to listen to them taking away some of my freedoms. How did both parties earn that trust?

I can answer for the school easily – it was just really good. Great teachers who were passionate about their subjects helped you follow your own interests in the subject, and gave you external opportunities to pursue the talent you gained from the course. Massive grounds with specialised facility buildings (you’d often see me in the art

block), sports fields for playing or relaxing, and a clean, refurbished sixth form building that gave my two final years a sense of maturity and importance. This place had enough space to feel like home, with love, safety and support; and ultimately, with safety come limits, boundaries and responsibilities. We all loved being at school, so when they set limits, we listened on the basis that these limits would maintain our safety. It was not an attack on adolescent free will, it was an effort to make things feel more like home.

In this sense, I had more comfort trusting that authority figures were indeed looking out for me, which made listening to my parents much easier. We all know the risks of social media and gaming, but after discovering them through YouTube early on, my passion for these pastimes was here to stay in my definition of relaxation. Because my home life was now largely spent in the digital world, my mum saw the need to get involved.

The thing is, alongside online platforms being a hub for toxic messaging, exploitation and catfishing, the people that posted snippets of

their life on YouTube or made the designs and stories within video games were still real people that anyone could connect with. These characters were the new celebrities, girl-nextdoors, and mentors.

My mum therefore chose to move her work setup to the living room, where I had my console. She would tell me about any videos she did not like, for example, she never liked British YouTuber KSI for being too vulgar for a 13-year-old. But crucially, she told me which ones she did like too. Yes Theory was a positive role model for fostering curiosity and anxiety, whilst YouTuber Jarvis Johnson was funny, but intelligent and informative – introducing me to many of the ethics I carry today. Rocket League, a car football game, reignited my mum’s sporty side – so much so that she accompanied me with a friend to the live E-sports final event in London, arguably getting more invested in her favourite team than we did.

In this way, my mum shared my space of comfort and exploration and made me more aware of how everything was influencing me. Because of that shared experience, I did not have as much desire to hide things that connected with me, and thus never really connected with things I had to hide. When my mum prevented me from getting any social media until I was 16, or when school encouraged students to stay away from violent games or keep phones out of bedrooms overnight, I listened because my racing games and history YouTube channels kept us company.

The key takeaway is that any child can be compliant with strict, annoying restrictions if they have enough space for the rest of their life within them. And with time, they will probably grow to love these limits as proof that they have a home. I always miss the peacefulness of going to bed without being tempted to scroll on Instagram for an hour, but at least I was never tempted to download X or TikTok. And now that I’ve upgraded out of a shoebox university room, maybe I’ll try putting my phone in the living room again.

PIET JANSEN MANAGING DIRECTOR, YES WE

CAN YOUTH CLINICS

Piet is the managing director of the world’s largest inpatient specialist centre for young people having to deal with mental health issues, addictions and related behavioural problems.

Lost in the virtual world

“PLEASE HELP, OUR SON GAMES ALL DAY AND WE DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO ANYMORE!”

These are just a couple of the painful cries for help we receive from parents on a daily basis. Although games and social media have been around for decades, it was only in 2018 that compulsive gaming was officially added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a charter used worldwide to classify mental health issues.

You don’t have to be a wizard to understand that the internet and social media have completely changed our way of living. The term social implies these platforms connect people, as originally intended, but nowadays many of them are abused by trolls to disorganise (elections), misinform (fake news) and groom (advertisers know more about you than you know about yourself). It is clear that many lifestyle pictures are too good to be true; children are constantly presented with a world that cannot exist in reality.

A FEW FACTS

• Almost one in two people on the planet age 13 or more has a Facebook account (3 billion users)

• Gaming revenues ($250bn in 2022 and expected to grow to $665bn in 2030) are five times higher than the film industry revenue ($43bln in 2022)

“SAVE US, OUR DAUGHTER IS CONSTANTLY ON HER PHONE AND WE ARE UNABLE TO GET THROUGH TO HER!”

• About 5.5 billion people have internet access (68% of the entire population), with the US and Europe having the highest percentage of people connected to the internet (83% and 94% respectively).

If you know that 1 in 6 people (1.8 billion) are between the ages of 10 and 24 and that 1 in 3 suffers from a mental health issue, you roughly have more than 600 million youngsters at risk. You do the math and decide for yourself if compulsive social media and console use is at a pandemic level, destroying the lives of families all over the world.

When 33% suffer from mental health issues, it is not so exceptional that your child may suffer too.

In a school with 1,000 kids, statistically around 330 will struggle and, of those, 10% severely with perhaps life-threatening issues. For the 300 kids, outpatient services will most probably be sufficient, but for the 30, more intensive measures are needed. If you extrapolate that on a global scale, we’re talking millions of young people in desperate need of inpatient services.

Take Jimmy: a 15-year-old intelligent and sensitive boy; a gamer who is suspected to be autistic but is undiagnosed and bullied for years but has never told a soul. His school curriculum is dreadfully dull to him and does not cater for his intellectual needs. So Jimmy becomes lazy and

his grades drop rapidly. The kids at school, his teachers and even his parents think he is unintelligent. So he starts to act like he is. But in fact, he is smarter than most. His social skills were never well developed, an unfortunate consequence of being autistic. So the only way out for him is to isolate and the virtual world offers salvation. His intelligence and ability to focus on one specific activity for lengthy periods of time make him the King of the Game. He gets high doses of dopamine every time he wins and opponents applaud him. In his view, he finally feels accepted. According to him, his virtual friends understand and respect him. So he needs more, every day. More dopamine, more wins. Now he hardly leaves his room, underperforms in school, sees none of his real-life friends (although he had few in the first place), neglects his hygiene, isolates even more, eats his food in his room and no longer engages in any family activities, let alone speaks to anyone. Aggression and sneers have become his daily routine to keep everyone out of his room. Ask a gamer why he games and he will respond it is not the game that pleases him, but the social contact…

Or take Sarah: an 18-year-old girl, never diagnosed with anything, smart, hyper-sensitive and super creative. She skipped through high school with no problems. But at university, she is no longer part of the cool crowd and just one of many in a landscape with too many challenges. So Sarah tries to belong and decided her appearance is the key to success. Her phone is her most treasured possession. She posts like crazy and adores a bunch of influencers who seem to live the life she always envisaged for herself. Slowly she loses weight and, after her relationship ends badly, starts to self-harm. Sarah no longer likes the person she is and starts to hate the body she is in. Other students see her slip away into isolation, although Sarah has become a master of keeping up appearances.

TOP 5 TIPS TO THINK ABOUT:

1. You are in this as a family

When one family member is not well, the entire system is affected.

2. Labelling is not the answer

Having been diagnosed with autism, ADHD or some other neurodevelopmental issue may provide some clarity, but a label in itself is never the answer to what is needed. The answer is how to adapt and accept.

3. Nature versus nurture

Some of the traits may have been passed on genetically, but the influence of the environment is just as complex. The more you heal yourself, the better you will be able to let others heal themselves too.

4. Understand the darkness

Young people, particularly during puberty, are bound to rebel. Yet resistance to treatment always stems from fear, anxiety, pain and shame. Underneath the aggression and isolation lies a deep-rooted problem of not feeling heard, seen, loved or accepted.

5. Ask for help

No matter what the neighbours might think or anybody else for that matter, ask for help and do not fear. To reach out is brave and you will see you are not the only one struggling.

Yes We Can Youth Clinics is recognised as the world-leading treatment centre for 13-25 year olds suffering from a wide array of mental health issues, addictions and related behavioural disorders.

With a global reputation for excellence and the highest staff to client ratio in the world (550+ staff vs 200 beds) over 10,000 young people have been through the Yes We Can Programme and gone on to rebuild their lives.

For more information, go to www.yeswecanclinics.com or info@yeswecanclinics.com

DR RUKHSANA AHMED CONSULTANT PEDIATRICIAN AND EPIDEMIOLOGIST ADVISOR

Dr Ahmed has 30 years’ global experience integrating clinical care, research and teaching to advance child health, nutrition and public health systems, leading services, trials and advisory roles across diverse, low-resource settings.

Avoiding triple burdens: overload of schoolwork, extra activities and digital drive

Modern children are growing up in an achievement driven world. They live in an increasingly demanding environment packed with academic expectations, extracurricular commitments and digital distractions. To keep pace, early morning tutoring, evening homework, weekend enrichment classes and prolonged screen time have become the norm. The triple burden of academic pressures, structured activities and digital drive mirror the daily saturated schedules of busy adult corporate executives. Yet these are young minds still developing emotions, cognition and selfregulation. While education and skill building offers vital benefits, the cumulative overload raises serious concerns about the mental, social, emotional and physical wellbeing of young children. This article explores the toll of overloading young children and strategies that families, educators and communities can provide to protect children from mental fatigue to help them grow into resilient, kinder and fulfilled adults.

THE TOLL OF OVERSCHEDULING

In today’s world, children are expected to excel in multiple areas: academic, sports, arts, social and digital literacy. The multi-tier pressure and overloading often affects their young minds in the following ways.

Stress and anxiety: constant juggling between school tasks and other activities, including performance expectations, exhausts their minds and triggers anxiety, sleep disturbances and sometimes leads to depression.

Physical exhaustion: long study hours and homework followed by extracurricular activities can result in fatigue, weakened immunity, poor concentration and becoming unwell frequently, which leads to missing school and other activities.

Academic disengagement: evidence suggests excessive academic pressure can lead to a decline in intrinsic motivation to learn, driving disengagement and resentment towards learning.

Loss of play and creativity: unstructured play together with imaginative exploration is essential for cognitive and creative development. Overloading gives less room for spontaneous joy and to develop creative arenas.

Reduced family time: when evenings and weekends are consumed by school assignments and extracurricular activities, children miss out on shared family times such as storytelling, meals, family play and bonding. These are key areas for emotional security and social development.

Loss of real-world connectivity: children can use digital media as an escape from overloaded schedules, or as a substitute for rest and play. Excessive screen use can displace direct interactions, play and family time. In addition, overuse of screen time can pose risks of reduced focus and decreased concentration on school assignments.

The highlighted problems indicate that overloading of children affects their cognition, emotional and behavioural development, and impacts their health. If we are to raise wellrounded children, instead of overburdened performers, we must protect their young minds from burning out and nurture their full potential by embracing compassionate learning.

Safeguarding children from overloaded daily schedules means more than protecting them from physical harm. It involves nurturing holistic development, ensuring space to grow, reflect and thrive, and protecting their overall wellbeing. It is not about restriction, but connection over competition, and wellbeing over pressured

achievements. A shift in mindset for a culture of balance and boundaries needs to be adopted by families, educators and communities. Highlighted below are key strategies for safeguarding young children.

Restorative time: families and educators should ensure that children get downtime to process experiences and regulate emotions. These include:

• A minimum of one unscheduled afternoon or evening per week

• Quiet time and screen-free relaxation

• Weekends protected from excessive academic demands and enrichment activities.

Encourage playtime: unstructured play is a developmental necessity for children. It should not be considered a luxury. We should:

• Value free play and children being their own self

• Create safe spaces for imaginative, unstructured outdoor and social play

• Avoid the temptation to turn every activity into a competition.

Limit extracurricular activities: while extra activities can enrich a child and are included with good intention, too much can overwhelm and comprise children’s wellbeing. When choosing activities, make sure they meet the child’s interest and not parental ambitions. In addition, all activities should be age appropriate. It is important to regularly check whether children are enjoying their extracurricular activities.

HIRA ALI LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT SPECIALIST, EXECUTIVE CAREER COACH, WRITER AND SPEAKER

Safer together: allyship strengthens safeguarding

Rethink homework policies: schools play a vital role in preventing overload and safeguarding proper development. Thoughtful homework practices, such as assigning meaningful tasks to reinforce learning, and avoiding homework over weekends and holidays would benefit children.

Foster open communication: children often internalise their feelings silently. Safeguarding would involve creating safe space for children to express their feelings freely, listening and validating their emotions, and encouraging children to say “no” when they are overwhelmed.

Safeguarding children is a shared responsibility of families, schools and communities. The different stakeholders can contribute to their responsibilities to avoid overloading. Families should value rest, play and emotional health, and resist pressure for competitive achievement. Schools can prioritise wellbeing alongside academic achievement, promote flexible learning environments, and train teachers to recognise signs of burnout and anxiety in children. Finally, communities could help by providing safe spaces for free play and social interactions, and encouraging celebration of all forms of success, not just academic or athletic achievements.

A simple yet profound truth in safeguarding children from overload begins by recognising that a child’s worth is not defined by grades, trophies and packed schedules, but by curiosity, laughter and a sense of belonging. Our goal is not merely to prepare children to produce test results, but to help them embrace and enjoy life. Providing compassionate learning is therefore important to nurture well-rounded children who feel valued. Together, families, schools and communities hold the power to protect the present and shape the future of today’s children. By embracing this shared responsibility, we can ensure that every child has the freedom to flourish safely.

Children deserve safe spaces where they can learn, grow and build friendships without fear of harm. Yet safeguarding challenges often show up not only in extreme cases of abuse but also in the everyday interactions that shape a child’s sense of safety and belonging. The words we use, the jokes we normalise, or the way we respond to a child’s “no” can leave lasting marks.

When we teach children empathy, consent and allyship, we protect them in the present while equipping them with lifelong skills to respect others and stand against harm.

Take bullying. It doesn’t always look like punches in the playground. It can be subtle; mocking a child’s accent, excluding them from a game, or constantly overlooking them when partners are chosen. These moments chip away at confidence and reinforce isolation. If a child believes speaking up will only earn a dismissive “don’t take it so seriously,” they may retreat into silence.

Safeguarding means noticing the quieter signs, such as withdrawal, reluctance to attend school, or a sudden change in appetite. A gentle, “Are you okay? Do you want to talk about it?” can open the door. Intervening doesn’t require grand gestures. It might be as simple as refusing to

laugh at a cruel joke, calmly asking, “What do you mean by that?” or reminding a classmate to let someone else finish speaking. These small actions model allyship – stepping in to create safer spaces for everyone.

Real-life examples demonstrate how young people can make a positive impact. Ruby Williams, a 12-year-old from the UK, stood against hair discrimination after being repeatedly sent home for wearing her natural afro. By speaking out, she helped change her school’s policy and raised awareness for countless others. Her story shows that safeguarding is not just about protection; it is about fairness and equity. Children need to know that when they challenge injustice, they will be heard.