Jeremy Lloyd

Christen Waddell

Serina Marshall

Austin Schreiner

Rick Johnson

Bonjwing Lee

Meghan Henley

Macy Roberts

Brad

Sallie Lewis

Jeremy Lloyd

Christen Waddell

Serina Marshall

Austin Schreiner

Rick Johnson

Bonjwing Lee

Meghan Henley

Macy Roberts

Brad

Sallie Lewis

Think about the notes and instruments in the songs you love listening to and how unique each place you’ve traveled to is. Imagine all of the emotions you feel throughout a single day. Or the differing interests between your children. (With a 15-year age gap between my oldest and my youngest, the interests in my family definitely cover a big spread!) We experience range in every part of life. This was a really fun theme to consider, because, true to its name, it opened endless possibilities for the content we could explore. The result was great conversations about personal journeys, authentic expression and how to look at things in new and unexpected ways.

In this issue, I ask Seb Bishop all about his artistic process and designing for Summerill & Bishop. Meghan Henley shares about the power of the full moon, writer Isabel Burton explores the benefits of allowing ourselves to feel every emotion – even when it’s hard – and our beloved friend Rick Johnson shares about the evolution of the Sam Beall Fellows Program. We got the unique opportunity to publish an excerpt from an upcoming book, and we journey into the diverse and incredible plant and animal life in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Fitting to the theme, the stories, photos and designs in these pages represent a beautiful variety of people and subjects. As you dive into this volume of Blackberry Magazine, I hope you learn something new and perhaps think a little differently about the ranges you experience in your life.

PROPRIETOR OF BLACKBERRY FARM & BLACKBERRY

MOUNTAIN

Mary Celeste Beall

EDITORS

Kathryn Sullivan

Sarah Elder Chabot

CREATIVE CONSULTING & DESIGN

FerebeeLane

Helms Workshop

BLACKBERRY CREATIVE TEAM

Andrea Rule

Sarah Rau

Paige Miller

Tim Sengaroun

Lora Cate Parker

Josie McDevitt

Tyler Ridgeway

Macy Roberts

Mikayla Devotie

PRODUCTION & PUBLISHING

Hawthorn Creative

ALLISON RUSSELL

Singer-Songwriter

AUSTIN SCHREINER

Blackberry Mountain Bike Supervisor

BONJWING LEE

Writer and Photographer

BRAD STULBERG

Author, Coach, Faculty at University of Michigan

CHRISTEN WADDELL

Blackberry Farm Farmstead Director

CHRISTINE CARNEY

Blackberry Farm Director of Design

GEMMA & ANDREW

INGALLS

Husband and Wife Photography Team

ISABEL BURTON Writer and Editor

JEREMY LLOYD Manager of Field & College Programs, GSMIT

DR. KEVIN DELAPP Professor of Philosophy

LOGAN GRIFFIN

Blackberry Mountain Director of Food and Beverage

MACY ROBERTS

Blackberry Content Writer

MEGHAN HENLEY

Blackberry Assistant Director of Wellness

RICK JOHNSON

Executive Director of the Blackberry Farm Foundation

SALLIE LEWIS Writer

SARAH RAU

Photographer for Blackberry Farm and Blackberry Mountain

SEB BISHOP

CEO and Creative Director, Summerill & Bishop

SERINA MARSHALL Writer

ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS

Becky Fluke beall + thomas photography

Cassidee Dabney

Elizabeth Kreutz

Ford Yates

Joel Werner

Joey Edwards

John Alban

Josh Feathers

Kelli Woodell

Kelly Schmidt

Phillip Hare

Reid Long

Sean Miller

Shauna Niequist

Trevor Iaconis

Tyler Florence

William Hereford

Pop quiz: If Yosemite has Half Dome and Yellowstone has geysers and bison, what makes the Smokies special? Answer: The range of life.

But what does this mean exactly? In scientific terms, it means the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most biodiverse ecosystem in North America. In layperson’s terms, it means the Smokies have got the goods on nature. This landmass functions as a living Noah’s Ark filled with biological riches and wonders we are still discovering and documenting.

Amazing fact: The Smokies boast more tree species (130) than the entire continent of Europe. Bringing it a little closer to home, if you were to step onto your cabin porch, you would likely be able to spot a greater variety of trees than exist in all of Yellowstone National Park, which has only nine. Why the stark difference? For one thing, consider that the American West is far more arid, and many landscapes contained in national parks out there are at a higher elevation, including above the tree line where few organisms can survive. The Smokies, on the other hand, dwell in the humid Southeast where precipitation is abundant in several forms – rain, fog, snow – and where there is no tree line.

Elevation also contributes to the range of life by mimicking latitude. For instance, if you were to drive from Walland, Tennessee, to Kuwohi (formerly Clingmans Dome), which is the highest peak in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, it would be like traveling from Georgia to Maine. At each stage of elevation, you would spot many of the same plants that you would find along the Appalachian chain if you were to head north.

Also playing a role is landform – the varying and complex shapes of mountain ridges and the “finger” ridges protruding off them – as well as the influence of the most recent Ice Age. Though glaciers never reached this far south, cold temperatures caused many plants

and animals to gravitate to a less frigid climate. After finding refuge in the Smokies, many stayed once the Ice Age began to wane and temperatures rewarmed. For instance, Fraser fir and red spruce trees migrated from lower elevations up the sides of mountains until they reached the sky islands where the climate is similar to that of Canada.

Thus the variety of life includes the great panoply of organisms living at all elevations, in every niche habitat, and in every kind of weather the Smokies throw at them.

One more testament to the diversity of life in this region is that almost as many different kinds of mammals live in the Great Smoky Mountains as do in the entire state of North Carolina.

For all their ruggedness, the mountains are rather hospitable if you are an animal. And not just any animal, but wildlife.

The word “wild” can be misleading, since, in contemporary usage, it can mean out of control. In a sense, this is true even in the context of wildlife: As untamed creatures, they are indeed self-willed and thus exist outside our control. And a good thing too, since wild animals flourish best by adapting to the cycles of nature and the self-willed landscapes where they are born.

The fact that we see little actual wildlife activity in forests within our region is also a good thing. It means animals are truly wild. Of course, most wildlife isn’t diurnal, or day-active, like birds and squirrels are. The majority of them are nocturnal and make their peregrinations while we humans snooze through the night.

Black bears provide one unique exception. Famous for their voracious appetite, they can be active any time of day or night, catching bear naps in between periods of time spent foraging for berries or nuts. Their range is also larger than most mammals in the Smokies, which makes sense: The larger the animal, the larger its territory.

Animals don’t recognize arbitrary human boundaries, and as a result, many range far outside the relative safety of the national park. This brings up some vital questions having to do with the future of conservation and the health of the Smokies. With human development of oncewild spaces happening all the time, can our range become theirs, and vice versa? Is there enough room for all? What wilderness spaces are we willing to set aside just for them in our towns and yards, while continuing to steward those who have freedom to roam in our national parks?

Imagine you have inherited a library from a long-lost relative. The only problem is that there’s no record of which books the library contains – no list, no oldfashioned card catalog, nothing. The first thing you’d likely do is find out which books you now own. What scientists call an “all-taxa biodiversity inventory” is something like this, only it’s far more challenging because the “library” is a half-million acres large.

Such an ambitious project began in the Great Smoky Mountains in the 1990s, with the goal of cataloging every living organism in the Smokies. At the start, roughly 9,000 species were known. Since then, the number has more than doubled, with over 11,000 additional species found living in the park. Of these, an astounding 1,092 are new to science.

In short, we don’t need to visit distant planets to discover new plants and animals. We’re still finding them right here. The range of life found in the Smokies is immense, which is something to both celebrate and preserve.

Waddell navigates a delicate balance between the rhythms of nature and the responsibilities of stewardship. In this contemplative portrait, she takes us into the life of the sheep at Blackberry Farm to explore what it means to be free.

ON A COLD FEBRUARY MORNING, while it’s still dark, pregnant ewes munch calmly on alfalfa hay inside their barn. It’s 30 degrees Fahrenheit and wet outside, but their wooly bodies are warm, standing together around the trough or resting in the soft, dry bedding. A set of triplet lambs were just born. They’re tiny – about seven pounds each – and all legs. Their mother is licking them clean. She takes her time and does it well, knowing that they are safe from predators and hypothermia inside the barn. At 5:30 a.m., I walk in and turn on the lights. I make notes of all of the new lambs in my notebook and which ewe they belong to. Are they nursing well? Do they look healthy? Are they so small that they need extra assistance? Is their mother taking good care of them?

The ewes are all used to me. I fed them as babies. I fed their mothers and grandmothers when they were babies as well. They don’t mind me walking through to look at their lambs. Inside the barn, it’s easy for me to be sure that I don’t miss anyone. Some of the ewes are ready

to be milked. I open the back doors, and they follow me into the parlor. They line up at the door and enter in the same order that they did yesterday. There’s Sydney in spot number five next to her sister. There’s Delilah in spot 12, and on down the line they go. Sheep love routine, and they’ve come up with this pattern themselves. They lick up the sweet grain in the parlor stalls while I milk them; then they go outside. Once the sun comes up and predators aren’t as active, I open the barn doors for the ewes with young lambs and offer them the choice to go outside. A couple of them run out, kicking up their heels in the cool morning air with their lambs stumbling behind them, but most of them choose to stay inside. About 20 minutes later, I hear the “baas” of the two that went out, letting me know that they have changed their mind. I go back out to let them in their barn, and they push their way through me as I start to open the doors, offended at how slow I am. By May, we are well into our milking season. The lambs are weaned, and the sheep are out on rich spring

grass. They start grazing before the sun comes up, while it’s still cool out. By 5:30 a.m. they’ve made their way over to the pasture gate and are waiting for me. As I walk up to open the gate, Daphne, the Farm’s gray donkey, makes her way over to survey the situation. She recognizes me and begrudgingly lets me borrow her sheep. If I had been a bear or some other predator that might threaten the sheep, she would have pushed her flock to the other side and come stomping in between, ready to chase me off. Donkeys are powerful protectors.

The sheep know where they’re going even in the dark morning, and they cross the street ahead of me heading for the Dairy Barn. They line up outside the parlor door and wait their turn to come in for milking. They prance excitedly down the parlor floor and turn into their stalls. After milking, I open the gate to let them go back down the road and into the pastures. The sheep lead the way across property and wait patiently for me to put them back into the fence.

bring Neza with me into the pasture and ask her to walk close to me. Her focus is fixed on the group of sheep, and she walks slowly and intently toward them.

“What domestic sheep value more than wide open space is

Later in the day, it’s gotten hot. The sheep are resting in the shade of the trees, and it’s still a few hours before they need to come up to the barn for the afternoon milking. I notice that one of them is limping, and it isn’t one of the few that like to be caught. I essentially have three options for treating her. One is to try to catch her in the field myself, running here and there, chasing her, startling the other sheep and the donkey, and inevitably being outmaneuvered by her in the end, leaving both of us stressed and panting. The second is to get a bucket of grain and convince all 130 sheep to follow me out of the field, take them on a 15-minute walk in the heat to the corral, where I could shut them into a smaller space and through a chute where I could treat her. This would work, but it takes the sheep away from their grazing time and puts them under more heat stress. The third option is Neza, the border collie. I

comfort and a sense of safety.”

They notice her immediately and begin to gather closer together. I tell her, “Come bye,” and she runs to the left, swings out and gets behind the sheep so that they are between her and me. The sheep move as a group away from Neza. They start to trail off to the right, but she runs out ahead of them and blocks their path. Neza doesn’t bite or even touch the sheep. She uses her body language to make them want to move away from her and her speed and agility to block all of the wrong paths. Then, the flock of sheep trot over to where I am and stand close to me. I ask Neza to lie down where she is. The sheep know me, and they are coming to me for protection. They don’t trust that Neza isn’t a predator. Even the sheep that normally avoid being caught will stand still and let me treat them if Neza is around. I pick up the limping sheep’s hoof and see a small stone wedged into a little crack between the hoof wall and the sole. There’s the problem. I trim it out with my shears and spray on a treatment. “That’ll do, Neza,” and we head back out of the field. The ewe is already walking much better, and the herd goes back to grazing.

Freedom is a very emotional word. It is a very human word. I will never truly know what another animal is thinking, but in my experience with livestock, it hasn’t seemed to me that freedom as we consider it is a concept that most of them think about. Rather, “Do I feel safe enough to relax here?” “Do I have access to meet my needs, both physical and mental, here?” Often, it seems that whether or not a space feels large enough or “free” enough to them depends more upon the answers to those questions than on what we as humans might define as free.

Sheep, for example, are prey animals. A sense of safety is important to them. When you observe them in a situation where they don’t feel safe, it will be obvious. Their heads will be held up high and tense, and their ears will be rotating about. They aren’t able to rest like this, and they usually won’t eat or drink either. What domestic sheep value more than wide open space is comfort and a sense of safety. We as caretakers can give that to them in different ways, like ensuring they are always with a companion, giving them a consistent routine and making sure they have ample sources of nutritious food.

One important thing for anyone working with sheep to understand is body language, both the sheep’s and their own. When sheep are in the barn, it is especially important to know how to move in a way that won’t make them panic. That varies greatly from sheep to sheep. Some sheep are very accustomed to humans being close to them and even like cheek scratches. Others have a wide bubble that they want people to stay out of. There are times, of course, where we have to invade that bubble for their own good, like when they need medical treatment, but it’s important to minimize the stress in that invasiveness as much as possible. Having proper equipment and proper knowledge are critical. Often, when moving or sorting sheep, you can set it up so that the location that you want them to go is the most appealing choice. Then, just give them the choice to walk there on their own.

Many people imagine animals roaming in wide open spaces to be the happiest, but that isn’t always the case. Often when those animals are given a choice, they choose what is comfortable and convenient over what we might see as being free. More often, it’s the freedom to engage in

natural social behaviors with each other, the freedom to choose between shelter and exploration, the freedom to eat when they want, the freedom that comes with feeling safe and comfortable. Those are the freedoms that make them happy, not the freedom to live without fences. In fact, that probably isn’t too different from the way a lot of humans feel. We often choose to give up a few of our own freedoms by, say, working a job or following laws, in order to maintain a higher level of comfort. Sometimes we have to take a bit of that freedom away from others if they aren’t capable of making those decisions themselves. I know my toddler would likely choose a lapse in safety over losing freedom by being strapped into a car seat. However, it is my responsibility to protect her and sometimes make choices for her when she doesn’t have a good understanding of the consequences. Taking care of animals could be seen in a similar way. There’s a balance between giving them appropriate choices when you can, and sometimes making choices for them when their health and safety is at stake. At the heart of that balance are respect and understanding.

SERINA MARSHALL

The rise and fall of a melody and the cascading notes of an orchestra can move us to tears, lift us to joy or stir emotions we didn’t know we were holding. It’s not just what we hear, but how we hear it – the pitch, the tempo, the tone – that shapes how we feel.

Every range, every shift in sound paints emotion across the canvas of silence, turning simple vibrations into human experience.

“As humans, I think our emotional responses to music certainly vary across contexts and cultures,” explains Jon Luttrell, a Tennesseebased performer with a background in music studies. “Breaking it down from a music theory perspective, the basic structures of music (i.e., the scales) vary significantly between traditionally Western and Eastern cultures, particularly in what they emphasize, such as chord and harmonies versus melodic lines.”

Jon adds that even these fundamental differences can help us understand the roles that music has played within these respective cultures across time and how people respond to it.

“Thinking specifically of Western culture, even as far back as the ancient Greeks and Romans, music was primarily used as a device within drama performances and religious ceremonies – two situations where its role was to convey or deepen the connection with a story and to evoke emotions within an audience.

Especially within Western music traditions, the mechanics of music compositions ranging from simple chants to large-scale choral masses are ultimately engineered to inspire feelings of awe, grandeur, mystery, repentance … irrespective of lyrical content. This is evidenced by the fact we can feel these same emotions

when listening to a piece of music (religious or secular) with lyrics in a language we don’t understand.”

Those who perform music vocally use their voices to convey emotion through the way they present the piece they are singing. This is done in a variety of ways, but according to stage performer Leigh Woodfin, tone and delivery are key components to making this happen.

“Through your tone you can express your emotion; through delivery you can use your body to convey the emotions with facial expressions and body movements. You can also intentionally adjust your vocal style to make listeners feel something specific,” Leigh says. “My favorite is adjusting my style to be silly and bring joy. I think that the same song can evoke different emotions depending on who is singing it or how it is being sung. Many songs

can be changed up to express something different. When someone covers another’s song, they bring something new to the delivery of it.”

There are also ways to express and illicit emotion just by changing the volume or tone of how a song is delivered. These dynamics can change the emotional impact of a song.

“For instance, whispering versus belting – these can convey many things. For example, whispering can come across as sorrow and heartbreak, while belting can come across as boldness and victory,” Leigh explains. “I was recently in a local production of Shrek the Musical . During the song ‘Freak Flag,’ we were encouraged to be ourselves and let our freak flags fly, so to speak. I enjoyed this performance because I could make it my own and send my own message, which was just that: Be yourself. I expressed that through tone and delivery.”

As a composer, Broadway’s Kim Scharnberg says that when composing, he doesn’t necessarily aim to make the listener feel a certain way. If there are lyrics or a story being told, he tries to get as deep within whatever emotion is trying to be conveyed.

“It’s always nice to go unexpected places musically, unless ‘calm’ is the goal. Now, different instruments contribute to different moods and emotional tones in every way possible,” Kim emphasized. “Each instrument has inherent qualities that are sometimes expected based on how it was used in the past. Whether we know it or not we’ve all been influenced by television, film and every music genre that exists.”

Possibly the most important question is this: What is the relationship between silence or pauses and emotion in music? Because the truth is, the silence of the song is just as important as the notes.

“Many don’t think of silence or pauses as part of music. They might think of it as the space before, between or after music. Well-placed silence or pauses can feel huge by their lack of content. They can feel louder than the music!” Kim says. “Performance is also a craft, researching what the music is about or what the ‘inside story’ might be. If it’s something I wrote, then I try to convey the core emotion, whatever it is. Sometimes the audience gets it, sometimes not, and that’s OK. We all relate to emotions differently.”

Is emotion in music universal, or does it depend on the listener’s own story? First, the degree to which an individual connects emotionally to music is proportional to some general measure of emotional intelligence and their receptiveness to feeling and being open to those kinds of experiences.

“This applies to music just as it would any other form of art, literature

or even a listener’s general interpersonal relationships. You’re not likely to see opposite reactions to the same piece of music absent some lived experience by one listener that has caused them to feel a certain way toward it,” Jon notes.

“Hypothetically, let’s take something seemingly innocuous like ‘Jingle Bells’ or another generic Christmas tune. For most, that piece would likely bring about generally warm or at least neutral sentiments about the Christmas season, perhaps reminding them of their own excitement as a child connected with the season; more than likely, an average listener isn’t going to have a strong negative reaction to that tune.

“Let’s say, however, that one individual experienced some sort of traumatic event – like illness, the death of a loved one or perhaps the end of a relationship or the loss of a job. Something negative occurred in their life around that time of year

or potentially even in an environment or location where that song was playing at a particular point in time. It’s likely they will forever have a negative association with that song or even the whole genre of Christmas music. The key thing to note is that their response to it is not dictated by the piece of music itself, but by the context and external influences on how it is now experienced by that individual.”

So, if music disappeared tomorrow, would we lose an emotional language? This notion has been famously expressed by a couple of noted artistic figures in both the 19th and 20th centuries. Victor Hugo, French author of the novels The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Misérables is quoted as saying, “Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent.” Another similar expression is attributed to 20th-century choreographer, actor

and director Bob Fosse. As it relates to why characters in musical theatre suddenly began singing or dancing, he is noted as saying, “The time to sing is when your emotional level is just too high to speak anymore, and the time to dance is when your emotions are just too strong to only sing about how you feel.”

Based on those notions, without music, we wouldn’t necessarily be losing emotional language; rather, we would be losing a tool of expression to help us convey emotions when all our other systems or language fall short.

“What is your range?” The question confused me at first, but I came to understand his meaning. He wanted to know how far I typically ride. There is no easy answer to that question. I responded, “It depends.” Most things in life are like that, I guess. There are factors to consider. What kind of bike am I riding? A sleek road bike surely covers the miles faster than a burly mountain bike. Traveling down smooth pavement is a lot faster than climbing up a rough, rooty trail. Am I out for a leisurely spin to the coffee shop or looking to spend the whole day on the move? I didn’t have a quick answer, but the question has stuck with me. What is my range?

When I was young, my range started with my neighborhood. All of us kids would cruise around on our bikes, staying within the confines of our suburban boundaries. Our world was one neighborhood big. That is until the day we learned if we cut through a small patch of woods, we could connect to another subdivision, and just like that, our scope doubled in size.

As I grew, so did my perspective. I can clearly remember the first time I rode 50 miles. 100 miles. I prepared for my first century like I was laying siege to a mountain, meticulously planning the route and my stops for food. When I had completed those 100 miles, I thought I had reached the pinnacle of human achievement. Suddenly that 50mile ride that had seemed so impressive at the time was dwarfed by the scale of this new accomplishment, but was this the peak of what I could do? Spoiler alert: It was not. It’s a simple fact that once you ride 100 miles, there’s always 101. 102. Eventually, you’ll ride around the entire Earth. But then you can simply turn around and do it again. And again. It turns out there is always more.

So far, we’ve only thought about this in two-dimensional terms, but true range exists in 3D. It’s one thing to ride 100 miles on flat terrain. But what about 100 miles on mountain bike trails? I found out that it is a lot harder than doing it on roads. Then, I learned riding 585 miles across the state of Virginia in three days was even harder yet. Could I accumulate the equivalent elevation gain of climbing Mount Everest (29,032 feet) in one ride? Yes, and more. What about climbing one million feet in a year? That will match you to roughly the altitude that the International Space Station orbits Earth. That seemed like an impossible feat until I did it. I know a guy in Alabama who regularly climbs two or three million feet every year. There is always more.

The beauty of all this is that each individual’s capacity is unique. We all have our own perspectives, our lines drawn in the sand that define what we consider “hard.” Those perspectives shift as we push beyond what we previously thought were our limits. If it’s your first time riding a bike, 10 miles will probably seem daunting. For you, at that moment, it is! One person’s struggle isn’t minimized just because it appears smaller than someone else’s. Hard is hard, even if our definitions differ. We would do well to remember that.

You might think this is where I will make my conclusion, perhaps with an inspiring quote and a call to action for you to get out there, to push your limits, find your own personal range and then extend it. I certainly advocate for everyone to do just that, but I have a confession to make. I have misled you, dear reader. There is a fourth dimension

to this idea of range that I haven’t touched on, and I think it’s the most important. Not to minimize the significance of physical challenge, but I’ve come to realize that there is a lot more to range than just the numbers. To borrow a wellworn cliché: It’s not the destination; it’s the journey. Throughout this process of expanding my own limits, I have seen countless sunrises and sunsets that took my breath away. I have ridden through swarms of fireflies at night, seen the Northern Lights, shooting stars, a solar eclipse and multitudes of other natural wonders. I’ve experienced the full scope of human emotions, cried tears of joy and tears of pain. I have met more different types of people than I thought existed, and I have fostered deep, meaningful friendships through bikes, connecting in ways that would not have been possible without all that pedaling. I’ve even found a way to make a living out of helping people push their own boundaries on bicycles. And now I get to see my own children learn to ride. I watch them struggle through challenges, discover things about themselves and the world around them, and create their own friendships through riding. All of these things mean so much more to me than the number of miles traveled or feet in elevation gained I could use to define my riding.

What is my range? Frankly, it’s limitless. Sure, there is actually a physical limit to how many miles I can ride in an hour, a day or a week, and if you want, we can have that discussion. I’m happy to geek out with you on numbers and data, but that’s the least interesting part of the story. For me, my range is defined by my ability to push myself, to rise to a challenge, even if it means failing. My range is the breadth of my personal growth, my connection with the world around me and the people I meet in it, and my capacity to absorb those things into a life of meaning and purpose. A life of fulfillment and wonder. A life that is lived.

So, I’ll ask you: What is your range?

by Rick Johnson

Self-made men and women, take note: Your aims and accomplishments, skills and proficiencies, the sum of who you are and who you are becoming are formed by all you take in, what you witness, touch and feel, by the words you hear, the marvels and mysteries revealed to you – the whole astounding arc of life that shapes us as we live it. We aren’t really so self-made after all.

That realization is especially evident to a select few young people who are called to be Sam Beall Fellows at Blackberry, and their range of experiences has gotten broader and deeper as the result of a program that offers them an immersive time of learning by doing, but also by observing, asking and coming to know. It is the ongoing work of the Blackberry Farm Foundation, and its story begins with another young person whose curiosity and passion for excellence and how to achieve it are as vital after his passing as they were when he was first preparing to become Blackberry Farm’s visionary proprietor.

In his early 20s, Sam Beall was fortunate enough to go on a once-in-a-lifetime journey that would forever shape him – and Blackberry Farm. After graduation from culinary school, he immersed himself in learning at The French Laundry, Cowgirl Creamery, The Ritz-Carlton in San Francisco and during weekends spent with winemakers, learning all he could about creating experiences that would become lifelong memories for his guests back home at Blackberry. Sam returned to become proprietor in 2003, and the path the Farm took was nothing short of extraordinary. The Fellows program is named in his honor, and he is its inspiration.

They are among the most accomplished students at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York, nearing the completion of their years of study and almost ready to begin or resume their careers in the hospitality industry. After being nominated, and following a rigorous application process, they are chosen to be Sam Beall Fellows and invited to spend a semester at the Farm, working in every phase of operations, from the gardens to the wine cellars, from making beds to making cheese, having the opportunity to learn first-hand and hands-on.

The Fellows program began the year after Sam’s passing because it was something he would have wanted done – to give people just starting their careers a way to be fully engaged in learning how to be the best at caring for guests, of being in every way hospitable, just as he had. It would be a chance – and a rare one – for young people to know not just how to prepare a meal or offer a place to stay, but to gain a deep understanding of how ingredients are grown and why that matters; to learn what about the soil and climate shows up in the wine; which first words of greeting make anyone feel truly welcomed; how treating a coworker shouldn’t be all that different from how you treat your guest.

In its early years, the program brought Fellows to Blackberry who had just begun their careers and who were nominated by the chefs, hotel managers and sommeliers who recognized their talent and potential. They spent time in immersive learning at the Farm and at some of the most highly acclaimed restaurants and hotels in America. But the COVID-19 pandemic brought the program to a halt, and in its aftermath, a shortage of labor in the industry caused a shift to the current relationship with the Culinary Institute of America and the focus on a full semester of study exclusively at Blackberry.

If you were able to spend some time with them, you would hear Fellows talk with a kind of quiet awe and gratitude about the “legacy of learning” that’s here: the genuine respect everyone has for each other; the excitement of new approaches to whatever goes on in the kitchen; getting their hands dirty in the garden; and coming to see their life’s work as a “passion project,” as one called it, rather than a job. They marvel at their exposure to so many amazing people who are always ready to answer when they ask “why,” or “how do you do that,” or “can you tell me more?” They are being made into more than they were by all they are experiencing, by the scope of possibilities in every day they live and learn here.

So maybe we should all see ourselves as Fellows, but with a small “f,” learning by doing, coming to know how to care well for others, making life into our own passion project.

If you’re on a road trip and get a flat tire, I’m not the friend you want with you. I wouldn’t know where to begin.

Someone in your golf scramble dropped out and you need a fourth? Nope, not me either. I’m not even sure I know how the sport is scored.

Need a charming plus-one to help you schmooze your way through a new company party? Definitely not. I’m highly allergic.

But when trivia night rolls around, am I that friend you want? You bet I am.

With the exception of a few, glaring blind spots – sportsball and contemporary pop culture among them – my mind is a vast and cluttered collection of esoteria. You need to know the last song from a Broadway musical that topped the pop charts? I’ve got you. What’s that decorative thingamabob that screws onto the top of a flagpole called? I know that, too. What candy was originally called “chicken feed?” Why, why do I know this? None of it has any applicable or practical value for daily life. I suppose that’s why we call it trivia.

Nearing 50, with no apparent expertise, I often worry that I’ve frittered away too much of my time and energy on fruitless pursuits. Among them are two college degrees that are currently serving time as wall decoration.

In a fast-paced world, where everyone has so much access to so much information all the time, being a specialist, we are told, is the key to success. Ten-thousand hours of practice

gets you closer to perfect. And perfect is what we’re all aiming for, right? That’s how you win an Oscar or an Olympic medal, become a concert pianist or a CEO. But where does that leave the rest of us curious folks, whose collective experiences are less monolithic and more diverse – in my case, more patchwork?

I had no intention of writing about any of this. Instead, for this issue of Blackberry Magazine, I had been preoccupied with a dinner I had shared with a couple of elite athletes. Former professional cyclists Robbie Ventura and Christian Vande Velde were at Blackberry Farm for the biannual Tour de Smokies event, and I was fortunate to have dined with them at The Barn one night. During dinner, I couldn’t help but notice that the two of them have extremely sharp and extended range of memories, reaching back decades. It was a recurring observation by others at our table that night as well.

I called Robbie a few days later to talk about this, hoping to build a story for this issue of the magazine. When I told him about this issue’s theme, he was astonished. By complete coincidence, he had just attended a lecture the day before by one of his favorite authors, David Epstein, who wrote a book entitled Range

In that book, David challenges the 10,000-hour theory. He says that success through deep repetition is the exception, not the rule. If anything, he noticed that credentialed experts can become narrow-minded, and their effectiveness decreases as their confidence increases.

Instead, accruing experiences in a wide range of subjects and fields creates a more flexible mind, one that is more nimble and able to pivot. It also creates a broader, more dynamic base from which to launch higher, build taller. Being a generalist, not a specialist, David says, is the way most people can maximize their potential.

This rang true for Robbie, who used himself as an example. He told me that his physical build doesn’t predispose him to being a competitive cyclist. However, Robbie was an avid athlete growing up and played a wide array of sports, including hockey, soccer, speed skating and baseball. Each one taught him a different skill set that would later prove useful in cycling. As he puts it, “The skills I gained from all my other sports allowed me to punch above my weight class as a cyclist.” In his 12 years as a professional athlete, Robbie rode for the U.S. World Team and earned over 70 career victories.

Now retired from the professional circuit, he parlays these lessons and life experiences into coaching others. He founded Vision Quest, which creates personalized training programs for endurance athletes of all levels and ages – from 8 to 80.

If this wasn’t immensely heartening for me to hear – a middle-aged man grappling with middle-aged questions – it was certainly delicious confirmation bias. Perhaps, having wandered from career to career isn’t a liability after all, but an asset.

David’s book brims with examples of people who have harnessed their diverse experiences to achieve incredible things. He shows that it’s breadth, not depth, that makes them dynamic.

Perhaps all of the trivia crammed in my head isn’t so useless. I must keep the faith that my coursework in Dostoevsky and Japanese Law will come in handy … someday. (Why didn’t I take Tax Law? I should have

taken Tax Law.) And even if it doesn’t, hey, it was an interesting detour on this journey. I’m definitely a lost cause when it comes to being charming – there are some things you just can’t learn. But I suppose it wouldn’t hurt for me to extend my range a little more and learn how to change a flat tire and play a round of golf. It still won’t make me a Renaissance man. But Robbie has me believing that it will help me punch above my weight one day. Until then, I’ll happily be the friend that everyone invites to trivia night.

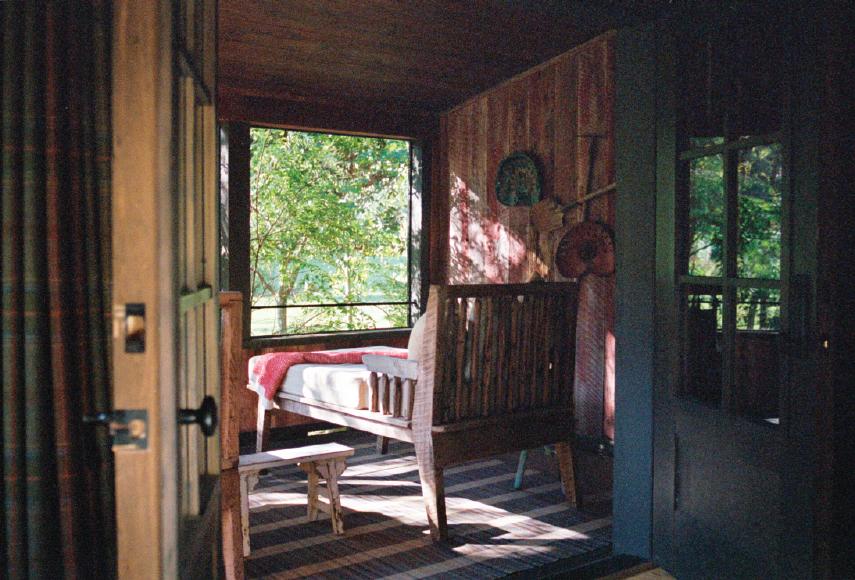

T his collection of photos is a small example of the range of life, experiences, beauty and impactful moments that are captured by some of the photographers that document life at Blackberry. These photos were not the ones on their shot lists, but they’re the unexpected details or scenes observed by

the artists that they couldn’t help but take.

by Sarah

Meghan Henley, Blackberry’s assistant director of wellness, curates meditative and movement experiences that lean into the connection between mind, body and the natural world. In her full moon practices, she creates a space for transformative energetic release, calling on the energy of this powerful lunar phase to help us let go.

I began my wellness journey much like many I know, in that I was, at first, focused on physical fitness and healthy habits of eating nourishing foods and prioritizing mindful movement. For years, this is where all of my attention went. As my children and I grew older, and I had a bit more time to explore my own emotions, I recognized patterns and cycles. There were clear times when I felt motivated and creative each month. There were also times when my mind and body needed a different type of nourishment: rest. I began to track them in my daily journaling, and when speaking with a colleague, I was inspired to look at the moon phases. I learned so much about myself during this time and began to learn more about how affected and interconnected we are with the lunar cycles.

Often when we think of the full moon, unfortunately we think of heightened emotions and intense or turbulent circumstances. What is gaining popularity in the wellness world, however, is what ancient traditions have been trying to remind us for centuries: When we are able to move into the full moon’s energy with awareness, it can be a truly special time for beneficial reflection and introspection. It offers us a unique opportunity each month to take some time to dive deep into our own needs and desires.

To me, the moon and its phases represent a mutable energy, almost personifying each individual’s soft, feminine and changeable nature. The full moon in particular is a great time to release thought patterns, behaviors and energies that no longer serve us.

What’s one sound, scent, or movement that captures the energy of your full moon work?

Sound: the deep, resonant vibration of a gong

Scent: the cleansing smell of frankincense

Movement: a powerful full moon salutation (Chandra Namaskar) yoga class

Leading up to the full moon, we instinctively feel something stirring inside of us. When we take the time to tune into these feelings, the motivation and inspiration for change comes naturally, and it seems almost easier during this time to do those deep dives. It is as if the illumination of the full moon highlights our needs, our current circumstances, seasons and cycles.

So, what differentiates full moon wellness work, at Blackberry Mountain or in personal practice, is that the experience is meant to help you harness the power of the moon in a deep and intentional way. At the Mountain, our teachers and healers may use breathwork, meditation, journaling or sound healing to assist in releasing old ideas or actions that are no longer beneficial. Each full moon is unique in what it is highlighting, and practices each month can be curated to lean into and support those distinctive themes.

Each month, we explore two experiences to work with the full moon’s energy – on the day of the full moon as well as the day before, while the energy is beginning to build. Moonstone Meditation is a wonderful opportunity to work with the energy of rainbow moonstone, which is associated with intuition and, true to its name, holds a connection to lunar cycles. This beautiful stone is said to create a calm energy and promote a sense of emotional balance and acceptance. Full Moon Alchemy Soundbathing is an elevated sound experience featuring our highest-quality Crystal Tones Alchemy bowls, meant to enhance the experience of release during the powerful lunar moment.

Having the time and space to bring to mind something that needs to be let go can allow for gentle or even momentous shifts, depending on the need of that individual under that moon. Whether it’s a guided experience or a simple meditation at home, a full moon practice is a wonderful time to clear stagnant energy and an opportunity for impactful emotional expansion.

Where the full moon is a time of peak energy and completion of a cycle, ideal for introspection and release, the new moon is associated with the start of a cycle and new beginnings. It is the perfect opportunity for selfreflection and intention setting – asking what we might like to call into our lives. This can be both broad and specific, not only bringing forth the big picture items but also those small details in daily life that could use a gentle “refresh.” It is a great time to create new habits for a happier and healthier version of yourself.

What is a good journal prompt to explore during a full moon?

I often focus on releasing negative thoughts and old practices or projects that are simply no longer working for me. To do that, I first spend some time journaling about those things that are no longer working in my life. I refer to this journaling practice as “WHY? HOW? WHAT?”

WHY do I feel these things no longer fit into my lifestyle or work life?

HOW have these old practices or procedures been affecting me both negatively and positively? Is there a way to hold onto those things that are still working?

WHAT adjustments need to be made once I let go of these things? And WHAT steps can I take to help my future-self acclimate to this new way of doing things?

These two moments seem to call us inward to explore either release and culmination – full moon – or intention setting and manifestation – new moon.

If the full moon had a voice, it would ask us to explore what we are refusing to relinquish in our lives. It would ask us to imagine our lives if we were willing to let go of what is holding us back. In what positive ways would our lives differ in just one week? One month? One year?

So, we asked the executive chefs of Blackberry Farm and Blackberry Mountain about their secrets to making sauce. What does it need? What’s your formula for striking the right balance of flavor? What makes a great sauce?

technique, contributing to a vast profile of sauces that create the memorable and distinct flavors in our favorite meals.

“A good sauce is an opportunity to push the overall flavor of a dish into something you can’t wait to taste again. I love when a guest tastes a sauce and their facial expression immediately changes – eyebrows raise, followed by a big smile. We do that with bright, fresh flavors to complement things like grilled meat or vegetables in the summer, or with a rich, slow-simmered sauce that is comforting in the winter. Either way, our goal is to always elevate the existing flavors, not mask them.”

– Joey Edwards, Three Sisters

“A sauce can make or break a dish. It needs a balance of richness, acid and interest, with playful texture that clings to the palate, allowing the flavors to linger. The sauce needs to complement a dish, not diminish or overpower.”

– Cassidee Dabney, The Barn at Blackberry Farm®

“What makes a great sauce, in my opinion, is the emulsification. A well-blended sauce is crucial for even distribution of flavor.”

– Joel Werner, Three Sisters

“Sauce is one of my favorite parts of a dish. It can bring that exciting pop of big flavor that takes a dish to the next level. It’s also the perfect place to have the richness, acidity or umami transform or tie flavors together. One of my favorite sauces for wine dinners is a mustard jus, where we take rich chicken stock and add dijon and whole grain mustard to caramelize throughout the reduction process, then finishing with more of both mustards to bring that bit of fresh spice and acidity to cut through the richness and sweetness of the caramelized mustards.”

– Trevor Iaconis, the Dogwood

“I think any sauce can go from good to great with a little garlic or lemon. Adding savoriness and acidity, whether fresh, microplaned garlic, roasted garlic and/or lemon juice or zest, can give the sauce a brighter and stronger flavor.”

– Phillip Hare, Firetower

“For me, a great sauce comes down to how it ties all the ingredients together. A wellmade sauce should create the backdrop for every other component in the dish to shine!”

– Sean Miller, Bramble Hall

“Sauce could mean the condiment on a sandwich, the dressing on a salad or the finish to a main entrée that could be a key component to pairing food with wine. Each different but they’re doing something similar for your food. Most have an ingredient or flavor in common that matches well with the other flavors happening in the dish. Think of an herb that may be in a marinade for a steak, such as rosemary, then making a red wine reduction for the sauce that has a subtle hint of rosemary.”

BY MACY ROBERTS

Pull. Aim. Release.

Tens of thousands of years have passed since humankind discovered archery, and while the practice has seen its fair share of developments over time, its core principles remain the same.

Whereas early bows and arrows were made entirely by hand from natural materials like wood, stone and plant and animal fibers, today we see their forms take on all kinds

of shapes and sizes. From relatively simple, machine-produced longbows to high-tech designs featuring a sophisticated mix of man-made metals, cables and pulleys, modern technology has –quite literally – changed the game.

As society evolved from nomadic hunter-gather communities where food had to be hunted and foraged to modern civilizations in which fully

prepared meals can be delivered to our doors with a few clicks on a screen, our reliance on the bow and arrow – much like its design – has shifted massively.

Whether it be a leisurely activity booked by hobbyists or an Olympic competition that sees skilled athletes from across the globe compete for gold, what was once a critical means of survival has transformed into a beloved

sport and an unconventional way to tap into meditative principles for focus. Pull. Aim. Release.

Regardless of if you were born in this century or millenniums ago, these foundational steps have stood the test of time.

It sounds easy enough, and if you’re picking up a bow for the hundredth time, it might even feel like second nature. Like many skills, archery is one that is honed through repetition. However, if it’s your first time encountering the sport, you’ll discover rather quickly that to perfect the fundamental motions of the sport, you must first conquer something else entirely.

As much as it’s a game of the body, archery is a game of the mind.

Hunter McDaniel has been practicing archery since he was 10 years old. Now the clay course manager at Smoky Mountain Sports Club in Louisville, Tennessee, he helps guests at Blackberry Farm and Blackberry Mountain experience and practice the ancient skill.

“I tend to see two main fears in people picking up a bow for the first time,” says Hunter. “They’re fearful of hurting themselves or others, and they’re fearful of failure.”

Fear and anxiety are natural human responses to trying something new. When picking up a bow for the first time, the body often reacts first, and the mind follows later. Our initial reaction is to grip the bow as tight as possible in an effort to control it. Adrenaline quickly kicks in, and we find ourselves holding our breath, stiff in our movements.

We can follow the instructions perfectly: standing with our feet

shoulder width apart, nocking the arrow at the optimal location, placing three fingers with a small gap in between, pulling the string back to our eye, in line with our mouth, and finally letting it fly. But if we forget to simply relax, to take a deep breath and relieve the tension from our bodies, the arrow hardly stands a chance of hitting the target.

To truly master the art of archery, we must let to go of more than just the arrow. We must let go of worry and overthinking.

state of mind, the more natural the bow begins to feel in our hands, and the more reliable our shots become.

“Once adrenaline has calmed down, we hone repetition. It’s crucial to understand the importance of each step and follow them every time,” says Hunter. “I’ll often see guests holding their breath at the start of the activity, but by the end of it, they’ve picked up a routine and can hit the target consistently.”

Archery has rich history, and the adrenaline inspired by the snap of the bow and a successful target

“The more we repeat the motions with a calm state of mind … the more reliable our shots become.”

“The older we get, the wiser we get. But also, the more we fear,” says Hunter. “We don’t feel as much fear when we’re kids. If someone says to go run down a hill at full speed, we do it without thinking of the consequences. But as we get older, we develop a comfort zone, and we don’t want to get out of it.”

By reminding ourselves to relax as we follow each of the steps we’ve been taught, our chances of striking the bullseye increase dramatically, and our experience improves altogether. The more we repeat the motions with a calm

hit fosters a unique connection to the ways of our ancestors from long ago. While most of us no longer rely on the skill for survival, the instant gratification of hitting the mark remains an exhilarating feeling.

In a modern age filled with countless responsibilities and endless distractions, archery asks us to ignore the noise around us and focus our attention on something much smaller. Letting go is often easier said than done, but great challenges yield high rewards.

Pull. Aim. Release.

And don’t forget to breathe.

Seb Bishop is the CEO and creative director of Summerill & Bishop, which specializes in luxury linen tablecloths and thoughtful home accessories designed to foster connection and celebrate individual style. &

mary celeste: Your professional story has spanned industries, including marketing, philanthropy and e-commerce. What personal experiences or skills from outside the world of design have unexpectedly shaped your approach at Summerill & Bishop?

seb: My sense of purpose guides everything I do. It is a constant driving force and provides direction and motivation to move forward every day. At Summerill & Bishop, creativity has a purpose beyond beauty. We’re here to bring people together; that’s our purpose.

Every time we sell a tablecloth, we know a family or group of friends will unite around the table. In the last few years, we estimate that close to a million people have gathered around one of S&B’s tablecloths. This stat makes me very proud and is

how we determine success. My background in advertising is where I learned the power of storytelling. It taught me to think from the outside in – to begin with emotion, not just product. That skill influences how I drive design at Summerill & Bishop today: I don’t just think about how something looks, but how it makes people feel.

mc: Was there a moment in your career journey when you felt out of your depth but chose to dive in anyway? What did that teach you?

s: I’ve never been one to tread the safest path. I’ve never chosen to stay within the same industry for years at a time. That, for me, isn’t how you challenge yourself. My career has taken me into the worlds of advertising, online search marketing, philanthropy, e-commerce, physical retail and now music. Each industry is a new lesson that you learn from the ground up, but that’s also what makes it so interesting – no two days have ever been the same. I’m driven by change, disruption and ideas.

When Mum passed away unexpectedly in 2014, though, everything changed. My purpose changed. Up until that point, my career trajectory was entirely in the digital space. I had previously worked in advertising, was at the helm when search marketing was first developed in Europe and helped establish both GOOP and (Product) RED as their CEO. I welcomed the advent of the digital age very much in the driving seat.

Bricks, mortar and physical product were completely out of my comfort zone. So, it was the first time I’d made a business decision with my heart rather than my head. I stepped in to take Summerill & Bishop in a new direction for my mum, Bernadette, and for June, her late co-founder, to act as a custodian for their vision and to continue the legacy of this beautiful brand

they had created. It taught me that you should take risks, especially if it involves your heart. If you love something, always fight for it.

mc: Your brand operates at the intersection of art, craftsmanship and luxury design. How do you consider the balance between functional utility and aesthetic expression within each product?

s: Our goal is to design products that people do not just use, but also keep, because they connect to both mind and heart. We are creating modern heirlooms to be enjoyed, cherished and passed down through generations. The table is a place to come together and to connect; it’s where life and all its big decisions and conversations happen. So, we want to encourage people to put away their digital devices and be fully present with one another. Setting the table, even if simply, is a form of art that we can all do at home. For us, tablecloths and tableware are more than just humble objects. If they encourage people to sit and stay at the table for longer, then they are the catalysts to conversation and mental well-being.

mc: Summerill & Bishop has built a reputation for its signature linens, but the collections are really diverse in theme – bold brights, quiet neutrals, lovely florals. How do you decide what belongs in the range?

s: For each of our designs to go into production, we always consider one important rule in our studio. We ask ourselves: Would we hang it on the wall as a piece of art? (Which many of our clients do!) I would say that Summerill & Bishop style lies somewhere between the contemporary, classic and cool. We offer something for everyone. If your heart skips a beat when you encounter beautiful table linens and thoughtfully crafted, oneof-a-kind items for your tabletop and your home, then you’re in the

right place at S&B. Our designs are playful, bold and memorable, but also simple and usable – full of joie de vivre. Our roots are very much a mix of rustic and modern aesthetics – a true reflection of the personalities of June and Bernadette. Their partnership and shared love of entertaining informs so much of what we do.

mc: Are there specific cultures or traditions of entertaining that have influenced your work – either in subtle design choices or broader philosophy?

s: I grew up in West London, and family meals were a weekly mainstay. My mum was the warmest host; my father a brilliant raconteur. It really came so naturally to them, and they made certain that my brothers and I were involved in the “mechanics” of mealtimes. Whilst we weren’t always trusted to cook (although I could always be counted on for a mean croque monsieur, which tells you everything about my culinary skill), we were given the role of setting the table. We would go out to forage for fallen leaves (London plane tree, the largest we could possibly find) to use as place cards.

who, after mere moments of sitting next to them, I wound up looking up to and admiring, personally and professionally. She taught me to really cherish what we have, as belongings aren’t necessarily ours. We are just enjoying and keeping them safe until it’s time to pass them down. This notion of togetherness and being present is really what influences me most.

At my parents’ dinners, I was always encouraged to pull up a seat at the table. For Mum, the more the merrier. It’s here that I learned the art of conversation: how to tell a joke, how to debate and crucially, how to listen. She had this brilliant way of getting me to engage by inviting people

mc: Tell me a little about your creative process. Do you start with a pattern or a color in mind? Or do you start with inspiration – a place, a season, a person – and develop from there?

s: Experiences and memories are my greatest inspiration; you have to get out into the world. Staring into the same old space will do you no favors. How can you design something if you haven’t

felt it, lived it, had your senses awoken by it? I find the best ideas come to you when you least expect them to.

mc: You’ve turned the simple tablecloth into a statement piece. What does it take to elevate the everyday, and how do you balance tradition and innovation in your designs?

s: At the simplest sense, we sell time. Yes, our products are tablecloths and tableware, but ultimately, we are selling quality time, time together around the table. The more beautiful a table, the longer we linger. Sitting together for a meal is one of the oldest traditions, but today we are often distracted. Our modern world constantly entices us to swipe and scroll. We’ve become unconscious.

We want our designs to be beautiful and usable, but what the tablecloth represents is crucial. I find that our

clients want to recognize the brand they have come to love but also be surprised by it. Our most successful designs combine familiarity with something unexpected, a twist we have become known for. We are not interested in the fast or faddish; we have always been about slowing down.

mc: I imagine it’s complicated to pick favorites among your designs. But is there a collection that feels particularly personal or reflective of your own inner creative style?

s: The first tablecloth that I designed, Bernadette’s Falling Flowers, was a way to commemorate my mother after she passed away. It was inspired by a floral motif that my mother would use to sign off on her correspondence. We trademarked her design to create our beautiful first collection, honoring Mum and commemorating her love for being surrounded by family and friends at the table. The design has now blossomed into many other products, including a serveware collection. Even though she may no longer be with us, the “Falling Flower” ensures that her presence is always felt around the table. This collection, which first launched in 2015, inspired me to take the business in a new direction and truly served as the catalyst for the beautiful statement pieces we create today.

mc: Summerill & Bishop was founded by two extraordinary women. You are continuing their legacy, as well as shepherding the brand to align with the evolution

of modern times – something I can personally relate to! What keeps you grounded in the roots of what your mother, Bernadette, and June originally founded?

s: I want Summerill & Bishop to be thought of as a cult brand in its own right, and so I’ve focused heavily on the development of our own branded product. Today, our table linen collections are at the heart of our business and are what is really driving the business forward. They are what we are known for, the reason why people come to us, our signature items. We see the laying of the table as an art form that we can all do from the comfort of our own homes – a simple and creative way of showing someone you care. Everything else is secondary to the tablecloth – we both design and source tableware to complement the linen designs.

Success at Summerill & Bishop is measured in how many people we unite at the table. We know Mum and June are looking down on us, watching us continue what they started, and I hope they’d be very proud of all that we’ve achieved in their name.

mc: I can imagine how much you miss your mom. Tell us about the first time you created a new piece for Summerill & Bishop that your mom would have LOVED.

s: I think she would love so many of our tablecloth designs, many of which reference our lives and memories made together. I know she would love the lavenderscented folding cards too, which we pop into all our tablecloth boxes. That is basically the smell of our shop every time you open the box. I’d like to think she would think those are great.

mc: In the story of Summerill & Bishop, you share that for June and Bernadette, “the heart of a home was the table.” I could not agree more. How do you want people to feel when they sit at a table dressed by your brand?

s: I would like them to feel at ease, knowing that they can speak openly and honestly about whatever is on their mind, whatever the topic. It’s really that simple.

You likely have a go-to cocktail order, a reliable default that rolls easily off the tongue when you prepare to answer, “What can I get you to drink?” But next time you’re scanning the shelves of bottles neatly lined behind the bar, take a moment to consider them. There’s a reason there are options for each spirit. There are nuances in flavor held within each bottle, and with the right order, they can shine.

Logan Griffin, Blackberry Mountain’s director of food and beverage, chose three of his favorite gins that are heralded examples of their category. The range represented goes from light (Sông Cái), to medium (Hayman’s) to bold and heavy (Bristow), offering an exciting display of how much variety one spirit can bring to a menu.

Gin notes: Sông Cái is floral and botanical in style. It pairs great with citrus, fizz and sweetness.

Ingredients:

1 oz. Sông Cái Gin

0.5 oz. lemon juice

0.25 oz. simple syrup 2 – 3 oz. dry Champagne

Lemon peel for garnish

To make: First, add the gin, lemon juice and simple syrup to your cocktail shaker. Add ice and shake until cold. Strain into a flute. Top with the dry Champagne. (For this recipe, we used Le Mesnil Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru.) Lastly, garnish with a lemon twist.

Gin notes: Hayman’s London Dry shows off a strong herbal note and texture, great for classic gin drinkers and using for martini variations. Hayman’s Old Tom Gin is also a great choice for this recipe. It’s subtly different from London Dry in that it’s less juniper-forward and more highlighted by a black licorice sweetness.

Ingredients:

1.5 oz. Hayman’s London Dry Gin 1.5 oz. Cocchi Vermouth di Torino 0.25 oz. Luxardo Maraschino liqueur 2 dashes orange bitters

Orange peel for garnish

To make: Pour all ingredients into a mixing pitcher and add ice. Stir until properly diluted or until the mixing pitcher is cold to the touch. Strain into a chilled coupe glass and garnish with an expressed orange peel.

Gin notes: Bristow Barrel is a gin for whiskey lovers. It can replace whiskey in a lot of classic drinks for a fun variation that has more herbal and dry notes. The 1-year aged was used in this recipe.

Ingredients:

2 oz. Bristow Barrel Aged Reserve Gin 0.5 oz. simple syrup

2 dashes of orange bitters 1 dash of Angostura Bitters

1 lemon or orange peel for garnish

To make: Pour all ingredients into a mixing pitcher, add ice to the brim and stir until properly diluted or until the mixing pitcher is cold to the touch. Pour over a large ice cube in a rocks glass. Next, express the oils of the lemon or orange peel into the glass and insert for garnish.

by Brad Stulberg

PRIOR TO ATTEMPTING A BIG LIFT IN THE GYM, THERE’S GENERALLY AN ELEMENT OF FEAR.

Will I make or miss the lift? What will a bar this heavy feel like? Am I willing, let alone able, to tolerate the discomfort? I often experience similar thoughts and feelings before speaking to a large crowd or shortly after committing to a challenging writing project. It’s a mixture of doubt, fear, and What am I getting myself into?

Runners feel it on the starting line of a race. Physicians feel it before performing a new procedure. Musicians feel it prior to a difficult solo. Discomfort is a natural byproduct of pushing our limits – which is to say discomfort is a natural by-product of growth.

Whenever we’d approach the bar prior to one of those big lifts in the gym, my training partner began saying brave new world. It represents the fact that we don’t know what is going to happen, but it sure will be interesting to see.

Herein lies the power of curiosity, a formidable antidote to fear that makes even the most challenging moments more satisfying. Curiosity is also integral to growth.

Think about how young children navigate their surroundings. They pick up objects and tinker, make all manner of sounds, try new movements, contort their bodies this way and that. When they stumble, fall down or hit some other roadblock, they may experience brief

frustration, but it’s not long before they are exploring again. Nobody taught them to do this. They do it because learning is innately rewarding, because curiosity is in their nature – which means it is in our nature, too.

Our hardwiring for curiosity doesn’t magically disappear when we reach a certain age. What happens is that our focus shifts to achieving specific outcomes, avoiding failure, and safeguarding our egos. Rather than perceiving challenges as opportunities to learn and grow, we view them as potential threats. Fear of failure overrides the joy of exploration.

Fortunately these behaviors can be unlearned. It starts with understanding the tug-of-war between fear and curiosity that happens inside our heads.

When confronted with significant uncertainty or challenge, a part of the brain called the amygdala livens with activity. Its primary purpose is to trigger a stress response if we face grave danger. It is a central part of what the late neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp coined the PANIC pathway: the neural circuitry that is predictably activated when our sense of self comes under threat.

The PANIC pathway evolved for good reason – if a tiger is chasing us, our survival depends upon our ability to feel fear and act on it. In the modern world, however, our threats rarely come from tigers. When pushing our limits, what we perceive as threats may not really be threats at all – and if they are, they

are probably somewhat tolerable. Performing at our best is rarely a matter of life or death. Even when it is, as in the case of a trauma doctor, for example, we improve our chances of getting into the zone and reaching peak states when we operate from a place of openness and curiosity.

Another brain region, the basal ganglia, receives input from the amygdala via a group of neurons that make up a tiny structure called the striatum. You can think of the striatum as a bridge connecting the basal ganglia to the amygdala, as well as to other parts of the brain. The basal ganglia is not solely connected with PANIC. It is implicated in other behaviors, too, including what Panksepp named the SEEKING and PLAY pathways.

The SEEKING pathway facilitates planning and problemsolving. It underlies our ability to exert agency and move toward challenges instead of being overtaken by fear, descending into helplessness, or impulsively running away. The PLAY pathway is linked to exploration, discovery, and adventure. When we embrace a mindset of curiosity, we activate the SEEKING and PLAY pathways.

Panksepp’s research shows that different pathways in the brain compete for resources, engaging in what amounts to a zero-sum game: If the SEEKING and PLAY pathways are activated, then the PANIC pathway is deactivated.

What’s more, the neural circuitry associated with curiosity is like a muscle: It gets stronger with use. If we are able to muster curiosity toward a challenge today, we’ll be more likely to do so out of habit tomorrow. Curiosity is what neuroscientists call a reward-based behavior. It feels good, motivates us to keep going, and builds upon itself.

When we adopt curiosity as a default attitude toward the challenges we face, we put ourselves in a better position to meet the moment and grow. It’s what the mantra brave new world is all about.

Adapted excerpt from The Way of Excellence by Brad

and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2026. Visit bradstulberg.com to learn more and purchase the book.

We asked some friends and contributors to share a book they enjoy – a read that stayed with them long after they turned the last page. If you’re looking for a great recommendation for what to read next, visit TheBlackberryMagazine.com to see why these titles were chosen.

bonjwing lee's pick Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein

isabel burton's pick Boom: Mad Money, Mega Dealers, and the Rise of Contemporary Art by Michael Shnayerson

editor's picks

Smart Mouth: Wine Essentials for You, Me, and Everyone We Know by Jordan Salcito

The Way of Excellence: A Guide to True Greatness and Deep Satisfaction in a Chaotic World by Brad Stulberg

mary celeste's pick House of Smoke: A Southerner Goes Searching for Home by John T. Edge

sallie lewis' pick Crossing Stars by Peggy Wolff Lewis

The numbers here represent some of the incredible statistics specifically from the selections currently on the wine list for The Barn at Blackberry Farm® The Farm’s cellar is rich with opportunities to learn about amazing wines and the people who make them, and the total number of bottles in the renowned collection is more than 150,000.

6,915

Distinct wine selections

1850 – 2024

Range of years represented

by the 16 1,400

Countries represented

106

Distinct producers

278

Pages in our wine list Grand Cru Burgundies

137,992

Bottles in inventory

81

Different vintages

6

Full-time sommeliers at The Barn

BY SALLIE LEWIS

THE GREAT FRENCH NOVELIST Marcel Proust once said that “the true voyage of discovery is not a journey to a new place,” but rather, “learning to see with new eyes.” Those words resonate deeply, even for someone like me who crisscrosses the globe for a living. My career as a journalist has afforded me no shortage of memorable trips and cultural awakenings, yet in recent years, I’ve come to learn that the greatest discoveries await much closer to home.

This revelation began back in 2020 when I moved to Fredericksburg in the Texas Hill Country to heal after my divorce. Little did I know as I left San Antonio in my rear view that just weeks later, COVID-19 would become a global pandemic, and the world would be locked down indefinitely.

My house, which was nicknamed “The Paloma” for its uncanny doveshaped architecture, sat on the outskirts of town, on a hilltop overlooking rolling fields and verdant farmland. In the depths of winter, I leaned into the cold, quiet environs and slow, steady rhythm of my new rural reality. Though my possessions were few, for my birthday that year, my father gifted me his vintage 1960s Leitz binoculars that were passed down to him by my grandfather years before. Imagining all the life they had witnessed through its lenses – including safaris in eastern Africa and countless adventures across the Lone Star State – made them even more meaningful to me.

As months passed and seasons changed, I found comfort and solace by immersing myself in the outdoors. With binoculars in tow, I foraged the countryside on daily walks, returning home with sharpened flint and woven nests, fallen feathers and dried turtle shells to add to my growing collections. As the moon waxed and waned, I marveled at sandhill cranes migrating high over my home and spotted newborn fawns perched on wobbly legs.

“I found comfort and solace by immersing myself in the outdoors.”

One morning, I awoke to the sound of gobblers outside my bedroom window. Slipping through the back door, I tiptoed outside and brought the binoculars to my eyes, watching in awe as the turkeys’ tail feathers splayed like golden fans beneath the sun. On another afternoon, just before dusk, I noticed a mysterious mound in my front yard. Reaching for my trusty glasses, I peered through the lenses and found a giant rabbit staring back at me, with large amber eyes aglow in the sun and long apricot ears pinned back on its cashmere coat.

That year alone in the country gave me a profound appreciation for the avian world too. Day after day, I marveled at the barn swallows working dutifully to build their nests along the eaves of my roof. As the weeks and months progressed, I saw their muddy, cup-shaped homes hatch with activity as tiny swallows with gaping yellow throats emerged with a fervor. Watching the next generation eat, grow and learn to fly was a heartwarming reminder of life’s continuity. Furthermore, the hatchlings, whom I named Thistle, Verbena, Primrose and Lantana, after Texas wildflowers, gave me faith that despite

the challenges we face, nature heals, and time marches on. Through it all, I began to sense a deep-seated curiosity bloom within me as I pondered my place in the world.

I’m especially grateful that I kept a journal during those silent, solitary days. Even now, when I leaf through its pages, I can relive the peaceful memories made outside, from the dreamy double rainbow that arced wide over my home to the wild turkey whose head beamed blue as it wove through long grass in the morning sun. I can remember treasure hunting for ancient flint on an old Texas riverbed and learning a foreign language constituted in native wildflowers – silver leaf nightshades, white prickly poppies and blackfoot daisies, to name a few.

In the wake of my sabbatical, I met someone new who shared in my burgeoning love of the outdoors. We’ve since gotten married and made Fredericksburg our permanent home. Today, we delight in the little things together, from feeding the cardinals, finches and sparrows that feast from the feeders in our trees, to watching deer graze beneath the light of the moon.