Bird’s Eye View

Every autumn, Malta becomes a vital crossroads in one of nature’s greatest journeys: bird migration from Europe to Africa. Thousands pass overhead, reminding us of the fragile connections that link continents and ecosystems. I encourage everyone to experience this spectacle - whether by walking through Buskett during the peak of raptor migration or visiting our nature reserves at Għadira, Simar and Salina. Each site offers a unique chance to witness migration while immersing yourself in nature.

This year, BirdLife Malta is proud to have received the Environmental Stewardship Award at the 2025 ERA Awards for restoring a small wetland next to Salina. Once buried under construction waste, this

area has been brought back to life, becoming a haven for wildlife and proof of what dedication and science can achieve. The award is more than an honour: it confirms the value of our work and highlights Malta’s responsibility in safeguarding biodiversity.

As the season unfolds, I invite you to celebrate and protect nature with us. Whether by visiting, becoming a BirdLife Malta member, or simply pausing to watch the sky, every action strengthens our mission. Together, we can ensure Malta remains a place where birds - and people - can thrive.

Mark Sultana CEO

Culprits brought to justice after being seen and reported by

Jul 2025

from trapping for three years.

An Egyptian Vulture named Hugo made a rare stopover in Malta just hours before the hunting season opened on 1 September. Hugo is one of only two chicks hatched this year at CERM’s captive-breeding centre in Tuscany, part of efforts to bolster Europe’s dwindling population. His movements were tracked by satellite, while BirdLife Malta volunteers, the Malta Rangers and the EPU police unit ensured constant monitoring during his three-day stay. On 2 September, aided by favourable winds, Hugo safely left Malta and continued his migration towards Africa.

Board Antonia Micallef (Editor), Victor Falzon (Naturalist & Field Teacher), Cinzia Mintoff (Graphic Design & Digital Media Communication Officer), Nadia Sodano (Communication Assistant), Sofia Meskhidze (Events & Outreach Assistant),

Officer).

BirdLife Malta Council Darryl Grima (President), Caldon Mercieca (Vice-President), Norman Chetcuti (Treasurer), Denise Casolani (Council Secretary), James Aquilina, Miriam Camilleri, Eurydike Kovacs, Paul Portelli, Kathleen Psaila Galea, Raphael Soler, Steve Zammit Lupi (members).

Senior Management Team Mark Sultana (CEO), Nicholas Barbara (Head of Conservation), Mark Gauci (Head of Land Management), Stefania Papadopol (Head of Public Engagement), Antonia Micallef (Public Engagement Executive), Gabriella Seguna Galea (Finance Manager), Manuel Mallia (Salina Park Manager), Manya Russo (LIFE PanPuffinus! Project Manager), Janet Borg (Office Coordinator).

Design Cinzia Mintoff

Printed at Poultons on sustainably sourced paper

Front cover photo Sooty Falcon by Ian Balzan

Reg. Vol. Org. VO/0052 © 2025 BirdLife Malta. All rights reserved.

On 27 August, BirdLife Malta received the ERA Environmental Stewardship Award 2025 for voluntary organisations, recognising long-term efforts in safeguarding Malta’s natural heritage. The Salina Wetland Restoration Project was highlighted for sciencebased habitat restoration and community engagement.

BirdLife Malta and other NGOs urge the withdrawal of July’s planning bills that are set to substantially weaken environmental safeguards and public rights. They call for a genuine public consultation before debate resumes.

The UK banned toxic lead ammunition to protect wildlife and public health. BirdLife Malta urges the EU to adopt similar measures. Lead is highly toxic to wildlife with no safe exposure level.

A coalition of NGOs, including BirdLife Malta, is urging the Planning Authority to reject an application that seeks to sanction illegal development at Dwejra. The application would set a dangerous precedent, undermining environmental protection and rewarding unlawful activities in a protected area.

BirdLife Malta has contributed to the designation of Croatia's first marine protected areas for seabirds, including the Lastovo Channel and Northern Adriatic. This achievement stems from the EU LIFE Artina project, highlighting the importance of cross-border cooperation in seabird conservation.

BirdLife Malta is restoring a 3200m² buffer zone around IsSimar nature reserve, through the EU-backed Community Greening Grant Scheme. Formerly a degraded dumping site, it now features habitats, a pond, paths, seating and panels. Opening this autumn, with free daily access.

On 14 August 2025, Italian port authorities at Pozzallo (Sicily) stopped a man trying to smuggle 2687 finches onto a transport destined for Malta. The illegally trapped birds were squeezed tight into boxes in subzero conditions. Their sale in Malta would have fetched a hefty total of €400,000 on the local black market.

BirdLife Malta's protected wetlands at Simar, Għadira, and Salina nature reserves provide safe nesting grounds for several birds. Our efforts to restore rare wetland and reverse habitat loss often lead to success stories. This year, Little Ringed Plovers, Black-winged Stilts, Eurasian Coots, Common Moorhens and Common Reed-warblers nested at these sites. Our nature reserves are the only sites in Malta where most of these species nest.

WORDS Antonia Micallef BirdLife Malta Public Engagement Executive

The Sooty Falcon is a medium-sized, long-winged bird of prey with a sleek, all-grey plumage. While it shares many similarities with the better-known

Eleonora's Falcon, a closer look reveals key differences: the Sooty is generally paler, slightly smaller, with a more prominent yellow cere. Its

Sooty Falcons are high-speed fliers that primarily hunt on the wing, often at dusk. Their diet includes bats, large insects like dragonflies, and small birds which they can

consume in mid-air. While they can hunt alone, they have also been observed working in groups to chase down migrating birds.

Unlike most falcons, the Sooty Falcon has a fascinating and unusual breeding schedule. It nests during the hottest months (late July to the end of August), laying 2–3 eggs in cliff ledges or rock crevices. This seemingly odd timing head is also proportionally larger and its tail shorter and more wedge-shaped than Eleonora's. Juveniles are browner on top, with buff-edged feathers; they can be confused with juvenile Eurasian Hobbies but they are slightly larger.

MALTESE NAME: Żumbrell Għarbi

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Falco concolor

LENGTH: 33–36cm

WINGSPAN: 78–90cm

IUCN CONSERVATION STATUS: Vulnerable

LOCAL STATUS: Vagrant

is a brilliant survival strategy, shared only with the Eleonora's Falcon. By breeding in late summer, the chicks hatch just in time to feast on the peak autumn migration of small passerines.

The Sooty Falcon is a social species, though less colonial than the Eleonora's Falcon. It breeds in mountainous desert regions and rocky coasts from eastern Libya to parts of the Middle East and as far east as south-western Pakistan. It is a long-distance migrant, travelling over 5,600km to its wintering grounds. Sooty Falcons depart their breeding colonies from midOctober through November, often travelling alone or in pairs. Their migration route typically takes them inland over Africa to their main wintering destination: Madagascar and the coasts of south-eastern Africa. The Sooty Falcon is an extremely rare vagrant in Europe, with only a handful of recorded sightings. As of late 2024, the Maltese Islands have six accepted records, while Italy has three.

WORDS Edward Bonavia Malta Rarities and Records Committee Secretary, and BirdLife Malta National Raptor Coordinator

CALL: A slow, coarse Kreeee-ah kreeee-ah, similar to Common Kestrel. Generally very quiet except when breeding. BEHAVIOUR: Highly aerial, feeding on insects for most of the year, but raising young in autumn on migrant passerines. HABITAT: During breeding confined to barren deserts, arid coastal areas and rocky islands.

Opening hours

Nature Reserve: Daily 7am–6pm

Visitor Centre: Mon–Fri 8am–2pm Entrance free (donations welcome!)

More info at http://bit.ly/SalinaNatureReserve

Fjamingu Phoenicopterus roseus

The greater flamingo is one of the most striking birds we see in Malta: large, with impossibly long neck and bubblegum pink legs (in adults), and a spectacular black-red wing plumage that would catch the eye of even the least nature-inclined among us. The flamingo's odd beak seems almost like a deformity but it's actually ideal for sifting small crustaceans from the shallow lakes where these birds live. Flamingoes are gregarious animals, living, nesting and travelling in groups. We have nowhere in Malta large enough for a bunch of them to nest but nearby Sicily and Tunisia do, thanks to which we too can enjoy regular annual sightings of flocks flying past on migration. The fact that Salina’s logo sports a flamingo is no accident, as the site is the best spot in Malta for these avian ballerinas to stopover.

Pispisella Actitis hypoleucos

If you’re on a quiet rocky shore and hear this persistent pss-wss-wss-wss! pss-wss-wss-wss! you’re probably sharing space with a common sandpiper. You probably won’t spot it as it’s small and its dark back merges with the rocks. But if you sit awhile and happen to be carrying binoculars, a slow scan of the shoreline should show him up. Although camouflaged the bird is rarely still, constantly bobbing its tail and poking around with its longish bill. It’s one of several wader species that visit our islands, usually staying a few days to rest and refuel before resuming its journey north or south depending on the season. But in protected areas like Salina a few sandpipers sometimes stay entire months, adding to life and movement around the saltpans.

Għansar Urginea pancration

The sea squill is a strange plant. After a dry summer that withers away its large fleshy leaves, you'd think the plant has died. But then, this weird vertical stalk appears, thin, pale and leafless, grows a metre tall and opens a plume of exquisite flowers. That's the trick of bulb plants. Like a medieval castle, the sea squill grows its food in times of plenty (= winter and spring), but with impending hardship (= summer) it draws all produce into the underground bulb, withers its leaves, and survives on its stored goodness. Its other trick is to flower at just the time when there are few other competing flowers, so it gets all the insects’ attention. Neat! Salina is largely a wetland, but there’s a nice strip of garrigue at the back where you can enjoy sea squill and other rocky habitat plants.

Rather than enduring the harsh European winter weather, many raptor species that breed in Europe prefer migrating southwards towards Africa in search of more favourable conditions and where prey is more plentiful. Migration is a very demanding task for birds, a journey full of challenges on their way to their destination.

Birds of prey are reluctant to cross large expanses of open water because thermals (warm rising air currents), which they use for soaring flight, do not form over the sea. As a result, raptors migrating between Europe and Africa concentrate at land “bottlenecks” to avoid long sea crossings. The most important of these are the Strait of Gibraltar in the west, the Bosphorus in the east, and the central route down Italy and Sicily: the birds that migrate over the Maltese Islands are those using this central flyway. Even locally, some areas attract more birds of prey than others, mainly due to habitat and location, and varies throughout the year. For example, Buskett is excellent for watching raptors in autumn, but less so in spring.

Weather strongly influences bird migration. Favourable winds help birds save energy, while unfavourable conditions may

slow them down or cause delays. Storms and heavy rain can lead to exhaustion or increased mortality, especially during sea crossings. Temperature and air pressure can also affect migration timing. Weather is therefore a crucial factor, heavily influencing the number of birds visiting our islands.

Raptor migration across the Mediterranean is strongly seasonal, occurring mainly in spring and autumn. In spring, birds move northward from their African wintering grounds to their European breeding territories, while in autumn they return south to avoid the harsh northern winter. Migration timing varies between species. For instance, honey-buzzards migrate in good numbers in late summer and early autumn, whereas eagles usually follow later. Juvenile birds also tend to migrate after adults, which makes sightings particularly interesting as they change within just a few weeks.

Although the Maltese Islands may not experience the large numbers seen at other Mediterranean migration points, they still attract a wide variety of raptors, especially in areas like Buskett. Among the regular migrants observed here are European Honey-buzzards, Western Marsh-harriers, Common Kestrels, Eurasian Sparrowhawks, Eurasian Hobbies, Eleonora’s Falcons and Lesser Kestrels. These birds are often seen in mixed flocks converging in the sky over Buskett, especially in the late afternoon. In addition to these common species, several rarer raptors occasionally appear. These include Egyptian Vultures, Saker Falcons, Short-toed Snake-eagles, Booted Eagles and Lesser Spotted Eagles. Some species, such as the Egyptian Vulture, have declined drastically in Europe, making their protection during migration crucial for survival.

The concentration of raptors at Mediterranean bottlenecks highlights the conservation importance of these regions. Because so many birds pass through relatively small areas, any threats along these routes can have disproportionate impacts on entire populations. Illegal shooting remains a serious problem in parts of the Mediterranean, including the Maltese Islands, where raptors are often targeted despite being protected species. Habitat loss at stopover sites and electrocution on poorly designed power lines also pose significant risks. Raptors are especially vulnerable to persecution since they gather in predictable places during migration. Coupled with the fact that they reproduce slowly, their decimation can have a ripple effect across regions and generations.

The predictable concentrations of raptors at migration hotspots make these areas key locations for research and long-term monitoring. In Malta, Buskett is one of the best sites for observing migrating raptors during autumn. Annual counts provide valuable data on population trends and conservation status. Data collected in Malta not only informs national conservation but also contributes to international monitoring, where information from several countries is collated to build a more holistic picture. More recently, satellite telemetry has revolutionised our understanding of raptor migration, offering much deeper insights into their movements.

Raptors are not only impressive and charismatic birds but also ecologically important species. As top predators, they regulate populations of smaller birds, reptiles and mammals, helping to maintain balanced ecosystems. Their migration across the Mediterranean is also a striking reminder of the interconnectedness of ecosystems across continents, linking nesting grounds in Europe with wintering habitats in Africa. Conservation efforts in breeding or wintering areas are effective only if these magnificent birds are also safeguarded during their migration. Birds have no borders: they belong to everyone. Protecting them is a duty and watching and enjoying them is a privilege we must ensure for future generations.

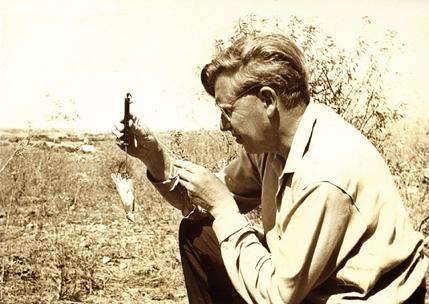

On 6 September 1965, a small bird made history in Gozo. In Xagħra, an Icterine Warbler became the first bird ever to be scientifically ringed in Malta. It was a modest beginning: a bird, a numbered metal ring and a handful of young naturalists from the recently formed Malta Ornithological Society, guided by Mont Hirons from the British Trust for Ornithology. Yet that simple act began a scientific journey that has stretched across six decades, with over three quarters of a million birds ringed and countless discoveries, all helping to shape the BirdLife Malta Ringing Scheme we know today.

With Malta at the heart of the Mediterranean, migration has always been central to the scheme’s work. Recoveries of at least 150 species from around 90 countries – stretching from Russia to Angola – highlight Malta’s role in the central Mediterranean flyway and beyond.

Since 1977, BirdLife Malta’s ringing scheme has been part of EURING, the network that coordinates ringing across Europe. Each year, data from Malta feeds into the shared EURING databank and the EURING Migration Atlas. The scheme also participated in regional collaborations such as the Piccole Isole project, which coordinated standardised ringing on Mediterranean islands. In 1992 and 2011 BirdLife Malta hosted EURING's general assembly.

Along with Għadira and Simar nature reserves, the Kemmuna Bird Observatory lies at the heart of our ringing effort. Established in 1990 it is today one of our main sites for monitoring migrants. Kemmuna’s position between Malta and Gozo makes it both a bottleneck and a vital stopover. Each spring and autumn, thousands of birds are ringed here during migration camps. The observatory also supports species-focused studies while training new ringers and hosting overseas visitors.

Ringing is not only about where birds come from and go to. It also throws light on longevity, survival rate and population health and trends. Every bird recaptured adds another piece to a knowledge base that has grown steadily since 1965. This monitoring is especially valuable for Malta’s breeding seabirds, which form internationally significant colonies. Ringing at their colonies has revealed survival and recruitment rates, as well as the pressures they face from factors such as light pollution, alien species and shifting food availability at sea.

Behind every ringed bird are the ringers, who rise before dawn, set up mist-nets, handle and record birds with skill, patience and care. Many ringers in Malta are volunteers, giving their time for love of birds and conservation. Across the decades, knowledge has been passed down, ensuring continuity and building a community of committed naturalists.

Ringing in Malta has never been easy. Limited sites, the high density of hunters and trappers and occasional intimidation and vandal attacks pose big challenges. More recently, politics has complicated matters, with ringing being maliciously propounded as an excuse to sustain rampant trapping, which is illegal under the EU Birds Directive. For ringing to remain a credible, scientific practice it must stay true to its mission: a tool for conservation, not a cover for exploitation.

Alongside traditional ringing, advances in technology are opening new horizons. We have successfully deployed telemetry devices on a number of species, tracking birds in real time. Genetic studies are shedding light on the taxonomy of local breeding populations. Blood sampling adds physiological insights, with various markers showing if and how birds are coping with challenges. While these are exciting and powerful methods that continue building on our knowledge, ringing remains irreplaceable for large-scale, long-term monitoring.

The scheme is also investing in the future of its data. A major digitisation project is under way to make all records available digitally. At the same time, plans for an interactive online migration atlas will bring this data to life for researchers, schools and the wider public.

But ringing is not only about birds and data. Its power also lies in people. Demonstrations, training camps and outreach, nowadays also through social media, are vital to inspire and recruit the next generation of ringers and ornithologists.

As the scheme marks this milestone, it is right to thank all who have made it possible: the visionaries who established the scheme, past and present ringers, committee members, and countless supporters who have contributed time and passion. Their dedication has ensured that from that single Icterine Warbler in 1965, the scheme grew into 60 years of discovery and an essential part of BirdLife Malta’s success.

WORDS by Nicholas Galea Head of Bird Ringing Scheme, BirdLife Malta

Stejjer mir-Riżervi Naturali is a new set of three children’s books published by BirdLife Malta, launched during Salt Fest 2025 at Salina on 26 and 27 July. Based on short animated videos co-produced with Toontuloon Animation Studio, the books are designed mainly for children aged 7–9, though they can be enjoyed by all ages.

Aron Tanti

Through engaging stories, the books introduce young readers to environmental care, perseverance, and the joy of protecting nature. They highlight how human actions—such as the creation of nature reserves—can make a lasting difference for the planet. Ideal for classroom read-alouds, bedtime stories, or as inspiration before visiting a reserve, they spark curiosity and learning about Malta’s natural heritage.

The three stories each celebrate one of BirdLife Malta’s nature reserves:

• Kiljan u Selina fis-Salina follows a young killifish exploring the Salina Saltpans with the help of friends Drinu and Kilina, and Selina the Flamingo. Together they discover the history and function of the saltpans, and how to survive predators.

• Manu u Ava fl-Għadira tells the tale of two newly hatched Little Ringed Plovers. Along the way, they meet a pompous chameleon and a kind Black-winged Stilt named Fej, who explains how Għadira Nature Reserve was created.

• Lozza u Martinu fis-Simar celebrates the wonders and challenges of migration. A resident Moorhen, Lozza, meets a migrating Kingfisher, Martinu, along with a meticulous dragonfly and a young eel, highlighting the many creatures that pass through Simar.

The original scripts were written by BirdLife Malta’s Head of Land Management, Mark Gauci. Field teacher Jason Aloisio translated and adapted them into Maltese, using a simple, engaging style for young readers. He also designed and produced the books. The colourful illustrations are carefully chosen stills from the animations, bringing the stories vividly to life.

The books are available from the nature shops at Għadira, Salina and Simar Nature Reserves. Each book costs €5.00 or €12.50 for the full set.

WORDS by Jason Aloisio Field teacher, BirdLife Malta

BirdLife Malta is leading a determined effort to control invasive plant species threatening the ecological balance of Salina Nature Reserve.

The reserve was once a centre for salt production but in recent years it has restored for nature conservation. One recurring challenge in this transformation is linked to its disturbed soils and altered water systems. These conditions provide opportunities for invasive plants such as Flaxleaf Fleabane and Giant Reed to spread quickly, reducing the ability of native species to recover.

Two culprits identified flax-leaved Fleabane, a native of South America, produces thousands of lightweight seeds that are dispersed by wind, water or human activity. Its life cycle ends between August and October, when seeds mature and spread widely, making early removal essential to block dispersal.

Giant Reed, introduced centuries ago, is another aggressive invader that reproduces mainly through underground rhizomes. Left unchecked, they quickly form thick stands, suppressing local vegetation and disrupting the natural water flow of the wetland. Seed production is extremely rare, with vegetative spread remaining the main driver of colonisation.

The spread of both these species has been accelerated by human activity, including past introductions, changing land use, and climate shifts that favour invasives. Flaxleaf Fleabane and Giant Reed are both officially classified as invasive species in Malta.

Work at Salina began in June, targeting flax-leaved Fleabane before flowering to prevent seed development. Control efforts will continue until November, by which time the plants will normally have either released or germinated seeds. Manual uprooting is most effective at this stage, whereas Giant Reed is managed through repeated cutting to weaken its rhizomes and reduce regrowth.

Occasionally, acacia trees too are uprooted during these sessions to avoid further establishment; these too are alien species and considered invasive. The wetland is monitored regularly, and the frequency of interventions is adjusted depending on how the plants spread.

The initiative relies on the commitment of dedicated volunteers whose work reduces the spread of these invaders and gives native vegetation space to recover. In turn, this helps safeguard Salina’s unique habitats, which provide critical refuge for birds, amphibians and other wildlife.

WORDS by Iñaki Leunda Land Management Assistant

Date: July & August 2025 I Location: Ta’ Ċenċ Cliffs

Date: July & August 2025 I Location: Salina Nature Reserve

Date: 13 June 2025 I Location:

Event: Flight in time: birds, evolution and Malta

Date: 14 June 2025 I Location: Salina Nature Reserve

Event: Sunset walk with Friends of the Earth

Date: 12 July 2025 I Location: Kemmuna

Event: STEM and VET Curriculum Hub

Date: 17 July 2025 I Location: Pembroke

Event: House martin and shearwater walk with YBC

Date: 24 July 2025

Location: ĦalFar

Event: Salt Fest

Date: 26 July 2025 I Location: Salina Nature Reserve

Event: Salt Fest

Date: 27 July 2025 I Location: Mellieħa

Event: Summer Night Eco Market

Date: 14 August 2025 I Location: Mellieħa

26, 27 Sep 2025 Find our Science in the City stand at Triton Square (6–11pm) in Valletta. Games and educational activity for everyone. This year’s theme is Past Forward: exploring the past and future of wildlife conservation. See you there!

28 Sep 2025 Join our guided walk at Għadira nature reserve’s sand dune and discover the rare flora and fauna of this very rare habitat. Allday activities, with bird ringing from 9–10am

4, 5 Oct 2025 Euro Birdwatch weekend. Many activities planned for everyone, whether you’re beginner or experienced birdwatcher. Saturday 4th: we spread across Malta for birdwatching at 6 hotspots. Sunday 5th: Bird ringing sessions at Għadira nature reserve. Don’t miss this chance to join birdwatchers from all across Europe!

join an event?

On 23 July 2025, BirdLife Malta released three rehabbed birds of prey in Sicily’s Parco dell’Etna. Two European Honey-buzzards and one Red-footed Falcon – all victims of the 2024 autumn hunting season – were set free after months of recovery. The honey-buzzard pictured above had crash-landed at the Seminary in October 2024 and later rescued and cared for by BirdLife Malta. The release was authorised by ISPRA (Italy) and ERA (Malta) in collaboration with LIPU (BirdLife in Italy) and park officials. The Parco dell’Etna was chosen as a safe, protected habitat where hunting is banned, giving the birds a real chance to survive away from Maltese hunters. The honey-buzzards were also fitted with satellite tags, allowing their movements to be monitored.