THE JOSEF HERMAN PAPERS

CARBONIFEROUS

COLLISION:JOSEFHERMAN'S EPIPHANYINYSTRADGYNLAIS

OSIRHYSOSMOND

DATE March2006

SOURCE InstituteofWelshAffairs

COLLISION:JOSEFHERMAN'S EPIPHANYINYSTRADGYNLAIS

DATE March2006

SOURCE InstituteofWelshAffairs

Osi Rhys Osmond

Cover: Josef Herman, Miner, Circa 1949. Oil on canvas,20 X 30 inches.

Dr and Mrs R.Jarman collection,Bristol – son and daughter-in-law of Dr Frank Jarman (1905 – 1986),a chest physician in Neath and an early patron of Josef Herman.

Published in Wales by Institute of Welsh Affairs

The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural,social, political and economic well-being of Wales.The IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group.We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals.For more information about the Institute,its publications,and how to join,either as an individual or corporate supporter,contact:

IWA – Institute of Welsh Affairs

St Andrews House St Andrews Crescent Cardiff CF10 3DD

Telephone 029 2066 6606

Facsimile 029 2022 1482

Email wales@iwa.org.uk Webwww.iwa.org.uk

First Impression March 2006

ISBN1 904 773 079

© Institute of Welsh Affairs

All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers

Published with support from the Faculty of Art and Design Swansea Institute

This Paper is published as part of the IWAco-ordinated Creu Cyfle-Cultural Explosion project undertaken during 2005-06 (www.culturalexplosion.net).The project, funded by the European Commission, aimed to promote links between the cultures of Wales and those of the new Accession States:Lithuania,Latvia,Estonia, Hungary,Czech republic,Slovakia,Slovenia Cyprus,Malta,and,of course,Poland.An early version of this Paper was prepared for a lecture given by Osi Rhys Osmond at the IWA’s Creu Cyfle-Cultural Explosion stand at the Eryri National Eisteddfod in August 2005.

Publication of the Paper has been made possible as a result of generous financial support from Mrs Nini Herman who has also contributed the Foreword.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

Ystradgynlais

Influences

2

Much has been written about Josef Herman, and the list grows steadily. However, this latest work is a remarkably complete and much needed exposition of the artist’s slow and painstaking quest for roots in a world seemingly bent on fragmentation and self-destruction.

Osi Rhys Osmond provides an account of Josef’s life from his birth in Poland to his formative years in the mining village of Ystradgynlais in the Swansea Valley, his Alma Mater. He concludes by setting the artist in the wider context of the influences upon his life and work. The author demonstrates great depth of understanding of his subject whose life spanned most of the 20th Century, from 1911 to 2000.

Josef Herman’s stature might at times seem over-shadowed by our contemporary preoccupations with song and dance and trivia, illustrated by today’s Turner Prize. Appreciation of Josef Herman can all too easily sideline the impact of his Jewishness. However, the reality was that, along with other youthful left-wing Jewish intellectuals, he was twice imprisoned for months by the Warsaw fascist police in an atmosphere of intensifying anti-semitism. Nor should we overlook the fact that during the same period his entire family of three generations was cast into a single room, in the ‘smaller ghetto’. Here any early attempt at painting had to be restricted to the small hours while the others slept.

None of these setbacks can be compared with the months of torment in Glasgow while he awaited the dreaded, inevitable news from the Red Cross of the extermination of his entire family. Their ‘smaller ghetto’ was liquidated and. along with the entire population, they had been pushed into waiting gas vans:

“I walked the streets of the Scottish city and all I could see was what my memory wanted me to see, a fabric of distant life which was nonetheless part of me; men and women in the refinement of a unique spirit. Most of them were poor, certainly, but I saw them in an aura which I can only call enchantment. I could not touch them but I could follow them with a line; I could draw a characteristic detail of their clothing, a characteristic expression, a characteristic gesture of their hands … I was a lover not a documentarist.”1

We find the most poignant entry in his Journals on the occasion of a visit to Paris in the late 1940s to hear from his old friend Pearl the excruciating details he had anticipated and so dreaded. As if in self defence he fell asleep at Pearl’s kitchen table, guilty at being spared and having been unable to save his loved ones.

There is a steady flow of such entries in his Journals.2 Memories constantly accused and tormented him in his hour of rising at 4am. It was a life sentence and led to recurring episodes of deep depression, one of which needed hospitalisation for almost three months to combat serious suicidal compulsions.

1)Josef Herman, Memory of Memories: The Glasgow Drawings 1940-43, Third Eye Centre, Glasgow, 1985.

2) Josef Herman, The Journals, Peter Halban 2003.

It was perhaps unsurprising that much of this was overlooked during his life. Streams of critics, journalists, and television teams for ever in and out of his studio met with a cheerful, hospitable and at times effusive man. They seemed to draw the very stuff of life from his presence in that old leather armchair at the foot of his huge easel.

Indeed, there were times when it seemed impossible to reconcile the ongoing agony and despair of his inner self with the warmth and life-affirmation of his outer presence. More generally, we have a psychodynamic sense of denial when facing the holocaust, that incomprehensible human transgression. One result is that Josef Herman’s heroic life awaits reassessment, a process that Osi Rhys Osmond has begun with this monograph. His achievement is to weave the first 44 years of Josef’s life into an organic whole. As the catalogue for one of his touring exhibitions put it, long ago in 1975:

“One does not seek roots: one grows them. And one is able to grow them only when one owns an organic energy, a capacity for inner development, which in turn owns as its necessary counterpart a capacity for response to the outer world, to nature and one’s fellow beings …”3

London January 2006

Today’s road to Ystradgynlais is very different from the one travelled by Josef Herman when he first arrived in this small west Wales mining village in the summer of 1944. In the 62 years that have elapsed the collieries and coal tips have all disappeared and the river runs clear. Today the main source of employment is found in the new industrial estates that flank the road into the small riverside village. Many commute to Swansea, fifteen miles away along a much faster and straighter road than the one Herman knew. Today Ystradgynlais is less isolated, less self-contained and less the product of a specific and singular way of life. The people are different too. Mining produced a particular kind of radical communitarianism. It reflected the difficulties of colliery work and its impact on family life and deeply marked the social interactions of the mining community.

Although the local Miners Welfare Hall has been refurbished and still serves as a vibrant community centre, one cannot help but wonder what kind of effect the present circumstances of Ystradgynlais might have on a stranger, particularly an artist such as Josef Herman. At the time of his arrival the Second World War was still being fought and the extraction of coal, essential for the war effort, gave a vital rationale to the workers and to the community’s sense of purpose. More generally the post war mood of positive change, of the realisation of long fought for social justice, was affirmative and optimistic. It was in this expectant world that the ambitious young painter was to find his own artistic and personal raison d’etre.

The arrival of Josef Herman in Ystradgynlais marks an important moment in the development of Welsh art. Before his paintings became familiar to the Welsh public, most of the art that took the miner as its theme looked at the subject in a documentary fashion. Usually the mood was sombre or sometimes fancifully dramatic, but without the vitality of the expressionist handling which give Herman’s images their primal power. Many of the painters who drew upon the miner as the subject of their art had come from the mining communities. Some had been miners themselves and while they did not aspire to be professional artists, they took it upon themselves to represent the drama, politics and sociability of their working and resting lives in a highly developed amateur art.4

Josef Herman’s refugee journey from Warsaw in his native Poland across Europe to Brussels, Glasgow, and then Ystradgynlais provided him with a long learning curve as he made contact with a wide range of artists and intellectuals along the way. He had been familiar to some extent with the history of the art of Europe and had met and exchanged ideas with contemporary Polish artists as a young man in Warsaw, while his interest in poetry also began during his early Warsaw years. In his writing Herman gives a vivid account of street life in the inner city of Warsaw and describes in great detail the social and political changes that occurred during his youth. As we know, Polish independence was finally achieved as a consequence of the geopolitical realignments that came at the end of the Great War in 1918. However, the ramifications of the changes that independence brought would prove to be extremely alarming for Warsaw’s Jewish community. Persecution of the Jews of Warsaw did not begin with the Nazis.

4)See

Josef Herman was the oldest of three children, born into a poor family. His illiterate father David, cheated out of a share in a successful business, failed hopelessly in an attempt to earn a living as a cobbler for which he lacked all talent. In these circumstances his beloved mother, Sarah, who had a middle class background, assumed the role of provider. She took in washing in the single room which housed three generations of the family. As a child Herman experienced real and debilitating poverty. However, what stayed with him throughout his life as a result of his upbringing was a constant fear of persecution. As a young man he served several prison sentences when Jewish intellectuals were rounded up.

His school days were generally a great disappointment. A bright child, he found the subjects interesting but the people who taught them insufferable. The exception was a Miss Rose Dickstein who was, as he says in his autobiography “the only bright spot in this stark universe of my memory”.5 This teacher of Polish literature and language introduced him to poetry and the magic of literature. Her reading, he says, “transformed each lesson into a dream. She made Poland’s poets and writers our personal friends. At some moments we actually felt the loneliness and desolation of a particular poet entering our inner selves”. The influence of such an inspirational teacher is possibly the determining factor in his own very effective writing in English, although he didn’t learn English until he came to Britain in 1941.

The adolescent recognition of the necessary isolation of the artist is significant and there are passages in his memoirs where Herman vividly describes his childhood feelings of darkness and despair. He experienced periods of a numbing separation from everyday life, times when his memory provided him with nothing but atmosphere, a sensation of not being a part of the world. He describes himself feeling as if he had been dead for five years, coming alive for a year and then sinking back into a kind of living death. This amorphous, swirling and undefined world later haunted him in his search for subject matter as a painter

Like all true artists it was such wrestling with the inchoate, a continuing quest for solidity behind the vagueness of the world, that led to clarification of an indeterminate but persistent form into appropriate subject matter for his painting. In the act of painting a similar situation pertains. The painter now has the nascent matter, the paint and the indeterminate but persistent form – the idea, thought or concept – and these are resolved in a harmonious exchange within the strictures of palette and canvas. The metaphysical becomes physical and the painting exists. Later in his autobiography, reflecting on his adult life, he describes his severe mood swings and bouts of depression. These seem to have been with him from his earliest days as those recollections of childhood periods of insensate amnesia remind us.

In his autobiography he talks also of “filling the void of inner emptiness” which he was only able to achieve after his move to Ystradgynlais, where he was accepted by the mining community and took miners as his subject matter. There his painting was underpinned by a personal and social stability that he had never previously experienced. Herman’s great joy at the discovery of the possibilities of monumentality in painting is understandably related to the

5) Related Twilights, Robson Books, 1975.

horrors he had experienced, memories lodged in the darker reaches of his soul. The relief is all the greater given the anguish he felt at the loss of his family and friends. In considering Herman’s life and work we must always remember that his past was taken away from him in every sense of the word. He had no one and no place to which to return. All had been totally destroyed. Ystradgynlais comforted him. It offered the essential social, physical and human corrective to his deep and persistent sense of loss which was also, perhaps, mingled, with the guilt of the survivor.

Recalling the schooldays of his childhood, Herman tells of the beginning of his love for the Polish language, first established by his inspirational teacher Miss Dickstein, and which was to remain with him. His fascination with Yiddish came later. At first he despised the language, seeing it as coarse and brutal, a product of the shettl and the slum. However, his Yiddish poet

friends made a huge effort to persuade him of its beauty and eventually he came to acknowledge it, no doubt helped by his structural appreciation of language passed on by his remarkable Polish teacher. Concern with the poetic value of the Yiddish language was prompted primarily by debates around the desire for a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. The Jewish people of Europe had suffered centuries of persecution and this had become particularly serious in the late 19th century. Pogroms had occurred with varying degrees of violence in many European countries, especially those in the east and those with their own problematic demons of identity, persecution and national aspiration. The Zionist World Congress had met in Basle in 1896, when Herzl declared the necessity for a Jewish state. Various movements to assert this ideal had already been established, largely as a result of the pogroms, and Jews had begun to leave to settle in what was later to become Israel. In his writing Herman refers to being called a ‘Madagascan’ by some thugs in the street, a reference to the fact that Madagascar had been cited for many years as a suitable location for the establishment of a Jewish State.

The Poland into which Herman was born in 1911 was home to a people longing for independence, pressed between the Czarist Russian Empire in the east and a rising and powerful Germany in the west. Much of what is today’s Poland was then held by these two great powers, while the once mighty, but decaying Hapsburg Empire stretched along the southern edges of the country. The nationalist movements of 19th century Europe had raised expectations everywhere and as the old empires crumbled new states rapidly came into being. Following the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles in 1918 achieved much more for Poland than the many uprisings of the previous century had done. It gave the country a defined boundary and a route to the sea at the expense of German territory. Later Poland gained more land from Lithuania and the Ukraine. Josef Herman’s early development cannot be appreciated without an awareness of the intricacies of modern Poland’s political evolution.

The country’s first Prime Minister was Padereweski, an internationally renowned concert pianist. However, the optimism of his first government soon gave way to the militaristic régime of the proto-fascist Pilsudski. From Herman’s writing it is apparent that even before this something very fundamental had changed in the relationship between Poles of Jewish extraction and some of those who considered themselves ‘true Poles’ and who suspected the former of having divided loyalties. Of course, in the growing debate about a Jewish state, a desire to leave could be perceived as a form of treachery. In the changing atmosphere, with worrying neighbours on every side, these two forces, Polish nationalism and Zionism, began to feel like justifications for one another.

As throughout much of his childhood, during this time Herman knew what it was to have an empty stomach. He describes the difficulty of following school lessons while suffering hunger pangs and of a new, idealistic headmaster who managed to obtain the assistance of an American charity to feed the famished pupils. This spirit of idealism was something that Herman was to encounter again during his stay in Ystradgynlais, something for which he felt a great debt to that community. To an extent it restored his faith in humanity after the bleak brutality of the war years.

When he left school at thirteen Herman at first abhorred all work. While this didn’t bother him, it worried those around him. He began employment in a small factory producing cardboard

boxes and worked as a carrier, moving packs of boxes on his back to various locations around Warsaw. He lasted less than a week. His back was too weak for the work, he was unable to stand and his constant falling damaged the boxes. His boss told him to get his mother to feed him better. “Lots of meat, that’s what you need” he was told.

Herman drifted in and out of various dead end jobs, and in doing so never felt humiliated by his failure in other people’s eyes, or by being told that he was no good, incapable of doing the

work. Instead, he felt relieved. He was deeply aware of his parents’ poverty and regretted his inability to assist them. In adolescence his lonely wonderings found an inner solace in a meditative appreciation of his growing sexual maturity. This eventually became a transcendental journey into the Polish countryside in the company of his friend Stephen, who had stolen some money from a coal merchant uncle to finance the trip. It was during this youthful odyssey that Herman realised that he was perhaps less able than average in sexual terms. However, he considered himself above average in matters of romantic love. His observations of colour and the sensations of the peaceful rural world accompanied his reflections on shared love between two people, the importance of which was to stay with him throughout his life.

Herman had no idea of what he might do with his life. He had no identifiable ambition and this became a worry to the family. Eventually an uncle agreed to introduce him to contacts in the printing industry, which at the time meant a well-paid job with favourable working conditions. Entry into the industry was much sought after, open to bribes and favours and for Herman it was to be a seminal experience. He was taken on as an apprentice to the typesetter Felix Yacubowitch, who was, in Herman’s words, “The warmest and kindest human being I ever set eyes on.”

For Herman the printing shop provided the equivalent of a university education. In the first place it gave him an aesthetic education. The discretion and subtlety of the typesetting process, the necessary sensibility to the formal elements of type and spacing, meant that the young apprentice had an intensive introduction to the dynamics of visual form. At the same time the printing shop gave him a challenging and stimulating initiation into the wonder of intellectual debate. The atmosphere was one of radicalism and political dissent. The print unions encouraged learning, had libraries and study centres where the apprentices could hear the finest speakers of the day. Among the visiting speakers were emerging poets and political idealists at the forefront of the modernist European avant-garde. They infused the young apprentice with new and exciting ideas. It was here, too, that he began to develop his appreciation of Yiddish, as noted earlier a language he had previously despised. Until the age of seventeen he had preferred speaking Polish. However, due to his growing awareness of the beauty and importance of Yiddish, for the first time Herman now began to be proud of his Jewish identity.

In the printing shop Herman’s innate aesthetic awareness and intellectual curiosity found a focus. The strict discipline of the type room formed the pattern for his fastidious working life as an artist. Indeed, he might have remained a type setter if it had not been for one particular incident at the end of his apprenticeship. In a welcoming ceremony for the newly qualified he was handed his lunch sandwiches into which one of his new colleagues had placed several pieces of old lead type. Swallowing the type before he realised what his lunch had contained he was welcomed into the fraternity of printers. Herman felt ill soon afterwards and was hospitalised for a few days. Tests revealed serious lead poisoning and he was advised never to come into contact with lead again. Consequently, work as a type-setter was out of the question. He recalled that “Felix Yacubowitch’s eyes filled with shock and disappointment at the news.”

He had been given magazines and encouraged by Yacubowitch to study modern typography and design. As a result Herman developed a growing appreciation and awareness of the world of the visual arts. He was introduced to the art of the Cubists, of Futurism and Constructivism. He read their manifestoes and absorbed their ideas and images. The colours of the Russian

Constructivists especially impressed him with their basic reds, pale greys, browns and blacks. It is fair to say that when he came into his own as a painter in Ystradgynlais he brought those colours with him.

What might have meant the end of a promising, but perhaps unrewarding career as a printer turned out to be the beginning of a much more rewarding and fulfilling one as a graphic designer and illustrator. In turn this led the way to Herman’s eventual life as an artist. Biting the lead had marked a watershed in his life, and after the initial disappointment, things would be very different. Herman now saw real art for the first time, in the shape of original paintings in the office of publisher Oscar Stern, a man who was familiar with contemporary art and artists.

He was able to meet other designers and enjoy the creative society of Warsaw, while he gradually became less enthusiastic about the business of design. Stern was concerned enough with this change of mood to tell the young Herman that he may after all “be a natural painter.”

Approval from a respected elder set Herman’s head spinning. Other discussions and encouragements came from the new friends he had made among the young artists Stern introduced to him. On evening he was walking home with the painter Felix Freidman who said, “Oscar told me you wanted to be a painter. What do you think, have you got enough talent for this?” Freidman elaborated upon his own theories about what made a painter, and what made a painter as distinct from what made an artist. He believed the musician and the poet have many things in common with the artist, particularly the painter, but they lack that essential ingredient, the sense of pigment. The painter should innately have this sense of pigment. It should be something he feels in his fingertips, and only if he has this can he really be confident in his vocation. Herman realised that the word ‘art’ had always made him feel embarrassed. He was a craftsman from a long line of craftsmen, while art seemed out of reach. Painting, however, was something more ‘down to earth’ with no need to feel embarrassed. And he felt that he, too, could feel the pigment, an itch in his fingertips. He looked down at them and realised “that they held a deep secret.”

Yet Herman was still not ready to launch his career as an artist. He hesitated, still unsure about the path ahead. In exchange for painting lessons he began to work as a model for a wellknown professor of painting whom he refers to as Professor S. The circumstances he found struck him as preposterous in the extreme – high academic pretensions, the studio stuffed with allusions to classical subject matter, and the young Herman posing naked with a fig leaf. The final straw was the ridiculous canvas the professor was working on, an allegory on the young Orpheus. Undoubtedly this alarmed Herman. However, the end came when he discovered that the Professor S was the author of an article advocating that restrictions should be placed on the numbers of Jews allowed to study in higher education. Standing before this strange picture, whose creator he held in similar contempt, the almost naked Herman thought to himself “with that silver fig leaf covering my sex nobody will ever guess that yours is the first circumcised Orpheus in the history of art.”

I think it probable that the ruminations the posing Herman engaged in as he went through the motions of becoming Orpheus finally convinced him that he needed to become a painter himself. The tired uselessness of the high academic was over. The world was changing rapidly. Herman became aware that a new kind of art was necessary to speak for a new period in history. Several months later he enrolled in the School of Fine Art and Decoration.

Art school education was a disappointment to him as in his day it would have been a very academic affair with none of the passion and freedom he was seeking. He left after eighteen months and began to keep the company of a painter who had spent a considerable period in France, J.C. as Herman refers to him. From him he learnt matters of technique, what was happening in French art and the importance of the triumph of the spiritual over the physical. He began to be interested in the work and writings of Edvard Munch (1863-1944), who had spoken of the necessity for a modern art that addressed modern issues.

Herman quoted Munch: “No more painting of interiors with men reading and women knitting! … I will paint a series of pictures in which people will have to recognise the holy element and bare their heads before it, as though in church.” J.C. recognised the value of seriousness over experimentation. He also emphasised the importance of the basic craft of painting and drawing which was a lesson that stayed with Herman for the rest of his life. Under the critical influence of the mysterious J.C. this period seems to have been Herman’s real visual art education. He felt deep self-doubt in those early years, something that remained with him to the end, and this very necessary self-examination was always punishing for him, difficult and troubling.

In 1932 Herman had his first exhibition in Warsaw in a shop belonging to a frame maker. He doesn’t mention any sales, so we have to assume that nothing was sold. The artist was looking for something else, a critical view, something to help him in his struggle to become a

painter. Friends offered comments most of which he felt were not very illuminating. He sent pictures to the academy and was active among a group of painters known as ‘The Frigian Bonnet’, a group of socially aware young artists whose radical political standpoint soon attracted the attention of the police. The change in Polish society since independence had seen an increase in anti-Semitism, and anyone who was a radical was assumed to be a communist and therefore an enemy of the state. To be radical and Jewish was seen as particularly dangerous. Additional pressure was building up as Poland and her neighbours began to see their Jewish population in a contradictory form of political double jeopardy: either as capitalists exploiting the workers or as some kind of threatening Bolshevik fifth column. At the time Jewish society was itself divided between two main groups, the Bund that was affiliated to Jewish and Polish socialism, and the Zionists who believed in religious salvation. Both advocated a return to the Holy Land, as outlined in the Balfour Declaration of 1917, as the answer to the growing problem. However, differences within families where younger members had begun a process of assimilation fired by socialist and anarchist ideas exacerbated the tensions.

Laws were passed preventing or restricting Jewish access to education while Jewish and Polish students were segregated in the classroom. The streets of Warsaw became the battlefields of a new ideological struggle as students, known as the ‘Green Badges’, and other nationalist malcontents attacked Jewish people and property. Other Jewish groups felt that only by an armed struggle could they defend themselves from the growing persecution and harassment.

Herman comments on the indifference of the authorities to what was happening: “the police often accused the Jews of provoking street disorder.” By 1938 he had had enough. The uncertainty provided the spark that his artistic ambition needed and he decided to leave Poland for good, not simply to escape the political situation but to further his dreams as a painter. Ever the survivor, with the help of friends he managed to obtain forged documents provided by a cooperative lawyer. He left by train and was seen off by his mother and father and his two best friends.

In his autobiography his recall of the parting resonates to such an extent that he might be describing one of his own paintings. “It was a dark, moonless and starless night, and although it was only the beginning of autumn it was very cold; a terrible noisy wind made it impossible to talk.” His mother moved close to the window of the carriage and pressing her face against the glass said, “Never, never come back.”

The picture he describes of their scarcely audible, but stricken faces peering through the carriage window on that bleak night, as the train pulled away is clearly conceivable as one of his own images. He saw, but did not hear their final goodbyes. So he thinks that they, too, could not possibly have heard his.

Herman was twenty-seven and he was never to see his parents again. They perished in the Holocaust. It is possible to view the subsequent struggle in his work to create a sense of viable human monumentality as a deep-seated act of retrieval, to r emake in paint an immutable equivalent for his lost family. In the course of the Ger man invasion and the implementation of the ‘Final Solution’ no more than 400,000 of a population of over three million Polish Jews survived. Like Herman himself most did so by escaping before it was too late.

The departing train was bound for Brussels. Since developing his interest in painting Herman had felt a stronger pull towards the art of the Low Countries than Paris, a more usual place to gravitate towards. The French, he believed, were over concerned with “refinement and sophistication, intellectuality and sensuality.” He felt “uneasy about the French genius.” and concurred with Delacroix’s view that it was simply ‘le charme et le gout’. Herman enjoyed Italian art for its serenity, but it was the intensity and simplicity of the great Northern masters that really mattered, qualities that were to become vitally important to him in his own work. The artists he was most familiar with were Rembrandt (1606-1669) and Brueghel (1524-1569). Their subject matter echoed his own concerns. No kings and queens for them. Celebration of humble peasant life was sufficient for Brueghel while Rembrandt’s masterly paintings revealed the innate frailties and uncertainties of humanity.

In choosing to flee to Belgium Herman says he “followed a dream not a reality.” The little he knew about Belgium was garnered from his awareness of its artists and poets. The only contemporary painter he was aware of was James Ensor (1860-1949). He had not heard of Albert Servaes (1883-1966), van den Berghe (1883-1939), or even Permeke (1886-1952), who was later to become a major influence on his work. He had contacts with friends from Warsaw and their families and settled down quickly to his new life in Belgium. At first he was amazed by the civility of the police, and as he went about the business of registering as an alien, by the way bureaucrats used their powers to assist, rather than obstruct the citizen, as they had in Warsaw. He sometimes amused himself by asking the most brutal looking policemen he could find for advice. To his joyous surprise their civility never failed and this impressed him greatly.

Herman wandered the city, visiting museums making contacts and reflecting on his situation and desire to become a painter. He socialised with radical students, although much of their political idealism was lost on him in the light of his own experiences. He was still very politically aware, but feared the left’s inability as he saw it to distinguish between bourgeois democracy and fascism. He believed freedom to be basic to individual life and felt that as far as Marxist theory was concerned the same logic could be applied to Fascism or Marxism. He had developed a very personal vision of social democracy, which he believed offered the best structures for human society.

Discovering contemporary Belgian painting at the Musée des Beaux Arts a whole new world opened up for Herman. He was rapidly convinced by the quality of distinct individual assertiveness it displayed, seeming to pay no tribute to any other cultural style. Above all it was the integrity of the pigment that convinced him, its ability to carry the “iconography to a moral depth”. He felt this was more than painting for taste and pleasure, much more than a simply aesthetic expression. It echoed his regard for Munch and the search for a modern equivalent to the religious power of earlier art. More than this it reminded Herman of the artistic values he had absorbed from his old Warsaw friend, the mysterious J.C..

Herman began to exhibit. He met Constant Permeke, whom he mistook for a peasant and who was to become a major influence on his work. To give his life a form more acceptable to the authorities Herman enrolled at the Brussels Academy of Fine Art. Here he enjoyed the

friendship and tutelage of Professor Alfred Bastien who had been a friend of Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and Monet (1840-1926) in Paris. The Professor helped him in his troubles with the Immigration Authorities. Times were changing. In pre-war Belgium the government was being continuously and systematically pressurised by the Belgian fascists and the laws relating to foreigners were relentlessly tightened. For Herman life was a continuous struggle against a gradually hardening administration, which was aware of and preparing itself for the momentous changes that lay ahead. After two years in Brussels and following the German invasion in May 1940 Herman joined two million Belgians as a refugee on the road to France.

As usual he was fortunate in meeting someone who was able to help him. This time it was an American woman who had been touring in France in her small car when war broke out. She gave him a lift and by taking the back roads they avoided the police who were arresting holders of Belgian identity cards. Eventually Herman was able to make his own way to Bordeaux. The Germans had over-run Belgium, had invaded France and were soon on the outskirts of Paris. Herman was sitting in a café, when he overheard some Polish civilians talking about La Rochelle, where apparently there was a Greek ship that would take Poles to Canada. Herman seems to have remained silent at the time about his own Polish identity Wisely he decided to make his own way to La Rochelle.

The Germans were now controlling large parts of northern France and most main routes were too dangerous to travel. He went outside on to the terrace and saw a parked car he recognised. It was the car of June Peach July, the extraordinarily named American lady who had helped him earlier. He sat in the car and waited for her to return. When she arrived, some time later when it was quite dark, he explained his predicament and she agreed to assist him again. She took him to La Rochelle, where the port was full of confused people, milling around and desperate to leave France. He was explaining to June the unlikelihood of them ever getting a ship out of France when suddenly he was seized by two huge Polish military policemen. In the panicking crowd he lost contact with June and never saw her again. Due to a black leather overcoat he was wearing the military policemen had mistaken him for a Polish deserter. He was billeted among a group of Polish Air Force men on board a ship, and after ten days, found himself off the coast of Britain. Herman came to Britain by mistake. He came, as he said, “… like a stranger, among strangers, in the night.”

The ship docked at Liverpool in June 1940 and Herman, who was obviously not a Polish airman, was ordered by immigration to report to the Polish Consul in Glasgow. He was absolutely penniless but found his way to Glasgow by hitching a lift with a Polish journalist. He was soon stationed at Biggar in southern Scotland as a member of the Polish army. He stayed for six weeks during which time he agitated for a transfer to the British army, raising objections to anti-semitism in the Polish ranks. This was eventually granted, but after his return to Glasgow he heard no more from the British military authorities.

Glasgow was to prove very hospitable. There was a large population of refugees, many of whom were Jewish, who had fled from the Nazis in Europe. In wartime the city had, as Herman described it “an ominous look” although in his writing he reflected as well on the beauty of the colour and light. The Blitz had just begun and Herman described the mood of the period as a time “when everybody listened to the sky.” In his usual, acute observations he recalls the Barrage balloons that hovered mysteriously and the searchlights that swept the night sky.

Since he had volunteered for the British Army he was still waiting to be called up for duty in industry or in the forces. During this period of uncertainty he occupied himself with visits to the Gorbals public library. As in most of his life, especially when circumstances seemed to be getting difficult, Herman found himself in the right place at the right time, In the Gorbals library an unnamed stranger with whom had he struck up a casual conversation first advised him to attend the Glasgow Arts Club, but then changed his mind and suggested that he make contact with a certain Professor Benno Schotz (1891-1984).

The change of mind was providential. Benno Schotz proved to be an extremely important figure since it was he who reunited Herman with his old Warsaw friend the painter and printmaker Jankel Adler (1895-1949). The dramas of Adler’s peregrinations rival those of Herman’s in their complexities and coincidences and effectively illustrate the peculiarities of the time. Like Herman, Adler had been born in Poland, in Tuszyn, and thus the two friends had a great deal in common. Between 1911 and 1914 Adler had attended art school at the Barmen Academy in Germany. On his return to Poland he was conscripted into the Russian army, where he served until captured by the Germans during the First World War. On his release at the end of the war he returned to Warsaw, but in 1922 settled in Düsseldorf where he became friendly with leading German artists. Later he began travelling widely in Europe, living chiefly in Paris, before returning to Düsseldorf in 1931 where he took up a teaching post. After two years there he fled back to Paris, escaping the increasing intolerance of the Nazis. During this period he lived and exhibited intermittently in Warsaw, which was where he and Herman first met.

Jankel was considerably older than Herman, but they quickly became firm friends. After settling in Paris in 1937 he worked with the famous S.W. Hayter (1901-1988) at the printmaking studio Atelier 17. He served briefly in the Polish army during the Second World War, before arriving as a refugee in wartime Glasgow. An intellectual with an enigmatic style of speech he rapidly became an influential figure in the Scottish visual art world. His relationship with Herman was, it seems, mutually tutorial in that they were able to exchange ideas from a shared understanding of the complexities of Euro-Judaic culture and an appreciation of aesthetic form from all over the world. Adler moved to London in 1943 where he and Herman continued to enjoy a firm and mutually supportive friendship.

Adler’s story also serves to illustrate another important aspect of artistic life during this unsettled period. This was the impact of moving and meeting caused by the political uncertainties of the time. While living in Germany Adler had been a friend of Paul Klee (1879-

1940) and by some kind of creative symbiosis was able to pass on the critical ideas discussed in Düsseldorf to his new friends in Warsaw, Paris, Glasgow and London.

In the contentious and convoluted r elationship between Poland and her more powerful neighbours, to be Polish was troublesome enough. However, to be Polish and Jewish was more than doubly so. The fact that both artists lived through this scorching cr ucible of persecution, the prelude to the horrors of the Holocaust, goes a long way towards understanding their consequent ambitions as artists and their characters as men. The complexities of these experiences and the way in which they served to inform and develop Herman’s philosophy of life and art are among the most crucial aspects of his existence. We need to reflect on them in some depth in order to draw out the real power of his subsequent work. He met many diverse personalities of different nationalities, people with other histories and with an assortment of ambitions, and in a variety of places and circumstances. Additionally, this diversity of places and peoples, pressured by the urgency of meetings and movements conducted in adversity, operated as an intellectual forcing house that enriched his language and ideas. Discussions enter ed into in these conditions take on an exigency that is dictated by the situation, as well as by their content. The heightened sense of being alive that war and calamity bring to life is palpable in the writings of Herman as he reflects upon those uneasy times.

On his way to meet Professor Benno Scholz he became involved in a chance conversation with the sculptress Helen Biggar. He describes her as looking “as mysterious as one of those Egyptian monuments in which the head sits on a block” – monumental is a word that occurs r egularly in Her man’s writing. She had failed to develop after a childhood accident, but for Herman she radiated an innate goodness and had achieved a sense of physical grandeur fr om her spirited r esponse to her bodily dif ficulties. They became close friends and she helped him acquire an easel (borrowed from the School of Art) and find a studio. He shared the building with, among others, Joan Eardley (1921-63) who is consider ed to be among Britain’s finest twentieth century painters. Although born in England she had studied in Scotland and her work was at first mainly concerned with the childr en of the Glasgow tenements and later with the coastline of North Eastern Scotland. Her interest in the social responsibilities of the artist and his subject matter coincided with those of Herman and they too became firm friends.

Schotz was keen to introduce Herman to J.D. Fergusson (1874-1961) a newly important figure on the Scottish art scene who had trained as a doctor before deciding on a career as an artist. He was a painter, printmaker and sculptor as well as a prolific writer on matters artistic. Fergusson had studied in Paris at the Atelier Colarossi and lived in the city from 1907 until the outbreak of the First World War. There he came under the influence of the Fauves as a painter and the Cubists in his sculptural work. In 1911 he began to edit an avant-garde magazine, Rhythm, at a time when his work was influenced by contemporary dance and music. Fergusson exhibited with the Post-Impressionists and the Futurists and became friendly with the major figures of European art. As a founder member of the New Art Club he exerted a huge influence on Scottish art. Like Herman, Fergusson had spent much of his life on the move, living for long periods in Europe and London, before establishing himself in Glasgow in 1939.

The pattern of influence that encouraged the spread of the latest ideas and philosophies is evident in all of the relationships that Herman and his coterie enjoyed in these hectic times. A sense of urgency prevails as each character acts as a catalyst for the creative development of himself and those around him. One of Fergusson’s tenets was that the international style did not rule out the possibility of a national style. Of course, at this time and even up to the emergence of post-modern theories in the 1970s, discussions about visual art focussed markedly on the ability of visual art to reach across the barriers of language and culture, communicating above the Babel and beyond the narrow confines of national identity. He wanted Scotland to have a distinct visual art identity of its own, but he also wanted it to have an international appeal.

Fergusson’s dilemma was echoed in Wales, where the heat of the debate forced national questions out of serious consideration in the fine arts. The fairly recent emergence of Welsh subject matter and the foregrounding of questions of identity, culture and politics is inherent in the latest cultural theories. Fergusson brought a refreshing liveliness to the Glasgow art world, both through his own somewhat eccentric personality and the value of his contacts with the seminal figures of early 20th century European art. Herman’s description of his spontaneous and theatrical lectures on the importance of Cézanne (1839-1906) makes one wish to have been there to hear them in person.

Benno Schotz and his home formed a social as well as an artistic milieu for Herman who had yet to find a subject matter to which he could really commit himself. Although conclusive subject matter was proving elusive Herman continued painting. In the spring of 1942 he exhibited in Edinburgh at Aitken and Dott, at the time Scotland’s leading private gallery. The exhibition featured Jewish themes painted in an expressionist style and was a great success, attracting a number of other artists who admired the power and energy of his work. Among these was a young woman artist, Catriona MacLeod, the daughter of a wealthy and wellknown whiskey distiller. She bought five paintings and almost immediately came to Glasgow to visit Herman and ask if he would take her on as a pupil. He did not want to take pupils, but after she came to visit him in his studio a relationship developed and within a few months they were married.

Towards the end of 1942 Herman received a letter from the Red Cross telling him that his entire family had been wiped out when the Germans had driven their murdering gas-vans into the ‘Smaller Ghetto’ of Warsaw. In 1948 Herman visited an old Warsaw friend, Pearl, now living in Paris, who was able to give him a graphic description of events on that dreadful day. He was haunted by wanting to know the details of what had happened to his family. At the same time he was terrified of finding out.

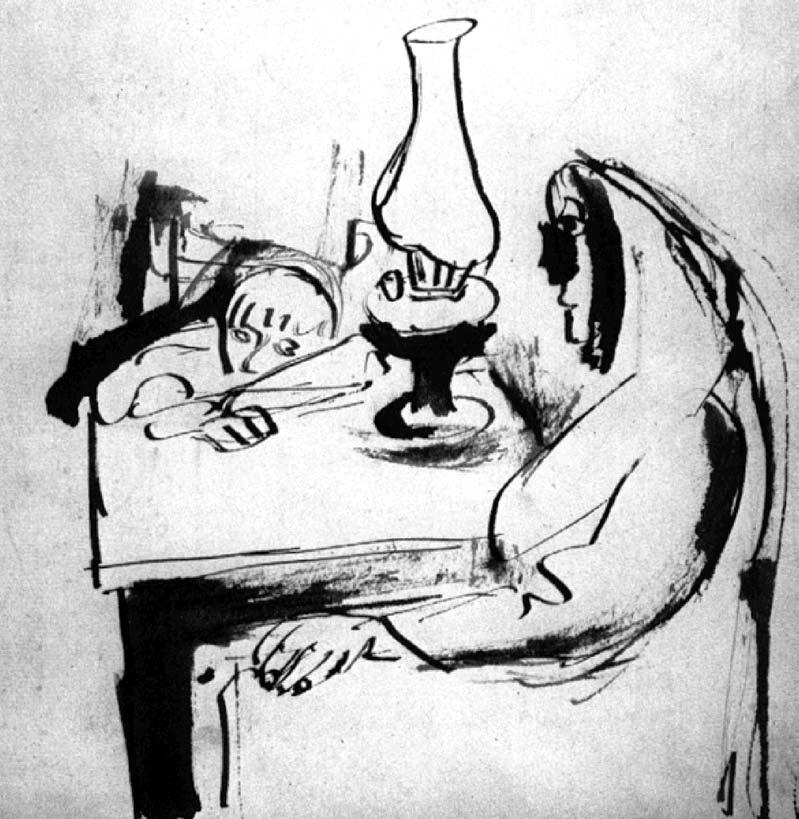

This was a necessary but traumatic experience and Herman records in his journal being ill for days afterwards. He suffered a deep depression, diagnosed as schizophrenia, which was to recur later in his life. It was during this time that he began to think back to his early life in Poland. He wondered whether his subject matter might lie there with his lost people who provided an abundance of imagery that he began to interpret. There were the memories of his family, the stories he had heard as a child, the Yiddish Theatre, and the folk art.

He worked with the support of his old friend Jankel Adler, producing drawings made in a quite experimental way. He adopted an almost trance-like perspective, not trying to illustrate but working from as he describes it, “a depth of memory.” He used ink and line and graduated washes to introduce elements of tone, reflection and shadow, with occasionally an accidental play of light, creating a suggestive atmosphere.

Later, when Herman looked at these drawings, he sensed they were not his own work but done by someone else. Shortly after completing them Herman moved to London where he was to stay between spring 1943 and the summer of 1944. During this time he showed a collection of the drawings at the Lefevre Gallery, an exhibition that had been arranged while he was still living in Glasgow

Soon after arriving in London Josef Herman took one of the Alma Road studios in Stratford Road. After finishing the paintings in good time for the Lefevre exhibition he realised that he was once again in a deep spiritual and creative crisis. The pictorial reminiscences of his Polish childhood had been an act of release in terms of his past. There was a sense now that that past no longer existed. Producing the images had emptied him of his beginnings as a person and he ached with a great internal void. He describes the situation thus: “The nostalgia for my childhood years had burnt itself out and nothing had taken its place, except a vague feeling for big forms and a cry within me for a new belief in man’s serenity.” There was also a feeling that art and morality should have some connection. Yet how this might happen seemed to be beyond his imaginative powers.

Only friends and conversation were capable of stilling his anxieties. Amongst these Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966) and Davie Bomberg (1890-1957) were fundamental. Meidner had been born in Germany and had studied in Berlin and Paris before serving in the German army during the First World War. A poet and expressionist painter whose pre-war work foretold of the terrors to come, he fled Germany in 1939 and was interned in England before making his home in London in 1941. He returned to live in Germany in 1953 and later exhibited there and in Italy. Meidner believed that the future of art lay in the city and in his early work had taken this as his main theme. Herman describes him as an excitable, ardent Judaist who would not utter the name of God without placing his deep blue, skull-cap on his head. Bomberg, too, was of Polish-Jewish descent although he had been born in Birmingham. Herman acted as translator when the three friends were together. Meidner’s English remained poor and Herman was required to explain to Bomberg in English what Meidner was saying in German. Their highly animated conversations, usually about art and revolution, were often interrupted by the roar of German aeroplanes overhead and the noise of exploding bombs.

Bomberg, a much quieter and more reflective character, was to become highly regarded as a painter. He had studied at the Slade and was active in the avant-garde of pre-First World War London, before serving in the war as an official war artist. In 1913 he travelled to Paris with the sculptor Jacob Epstein (1880-1959), where he met Picasso (1881-1973), Derain (1880-1954) and Modigliani (1884-1920). In London he showed with the Vorticists, was championed by Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) and became a founder member of the London Group. He travelled extensively in Europe and Palestine producing powerfully expressive landscapes. He disagreed with Meidner’s main thesis, as he felt that the artist could make any subject relevant to contemporary experience. As Herman quotes him, “Even flowers can be painted so as to remind us of all the terror in the human breast!” Bomberg was an influential teacher at Borough Polytechnic, where contemporary London Group painters Frank Auerbach (1931-) and Leon Kossoff (1926-) were among his pupils. Herman himself accepted an invitation to join the group in 1948.

Another of the exiles in Herman’s wartime London circle and one who was also to spend time in Wales, chiefly as a visitor, was Martin Bloch (1883-1954). His painting ‘Down From Bethesda Quarry’, commissioned for the 1951 Festival of Britain, is in the collection of the National Museum Wales in Cardiff. Bloch was born in Germany and studied art in Munich and Berlin under Lovis Corinth (1858-1925) before travelling extensively in France, Italy and Spain.

He left Germany in 1933, spending a year in Denmark before arriving in England and took out British citizenship in 1947. Bloch was always the expressionist, a fine draughtsman whose work was strong in colour and emotion. He exhibited widely and taught in America and Britain. Herman’s coterie in London included prominent members of the new English Romantic movement. They celebrated the achievements of Palmer (1805-1881) and Blake (1757-1827) and strove to connect their iconography to a contemporary sensibility. Graham Sutherland (1903-1980), Henry Moore (1898-1986) and John Piper (1903-1990) were the chief protagonists, with John Minton (1917-1957), Keith Vaughan (1912-1977) and Michael Ayrton (1921-1975) as junior disciples and the Scottish painters Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962) and Robert Macbryde (1913-1966) representing youth and colour.

In his descriptions of these and other artists of the London years Herman constantly refers to their work in terms of dignity and humanity, qualities that have great significance for him in his own work. He stresses his own deeply felt foreign roots and admits that these gave him the ability to recognise and celebrate the features that endow English art with its distinct characteristics. He sees Moore’s ‘Sleepers’ as possessing “a terse beauty, an elegiac power and a heroic structure” and comments on “their Masaccio like solidarity.” He credits their influence on his decision to begin making his own work again. But, however desperately Herman wanted to paint, desire was not enough. He could not begin, for he was without a significant subject.

Carboniferous Collision Josef Herman’s Epiphany in Ystradgynlais

Herman and his wife Catriona came to Ystradgynlais through a serendipitous meeting with Dai Alexander Williams who at the time was a colliery carpenter and short story writer. Herman had been wondering what to do to break the creative impasse that faced him. Nothing seemed appropriate as subject matter and try as he might there was nothing that could fill the deep void he felt within.

A friend of his had holidayed in south Wales and thought that Herman might enjoy the dramatic landscape of the mining Valleys. He decided to make a short visit and see for himself exactly what it was that had so excited his friend. While in Brecon he chanced upon the colliery carpenter who was to introduce him to Ystradgynlais and the mining community. He and Catriona were to stay in Williams’ home in the village until they found a place of their own.

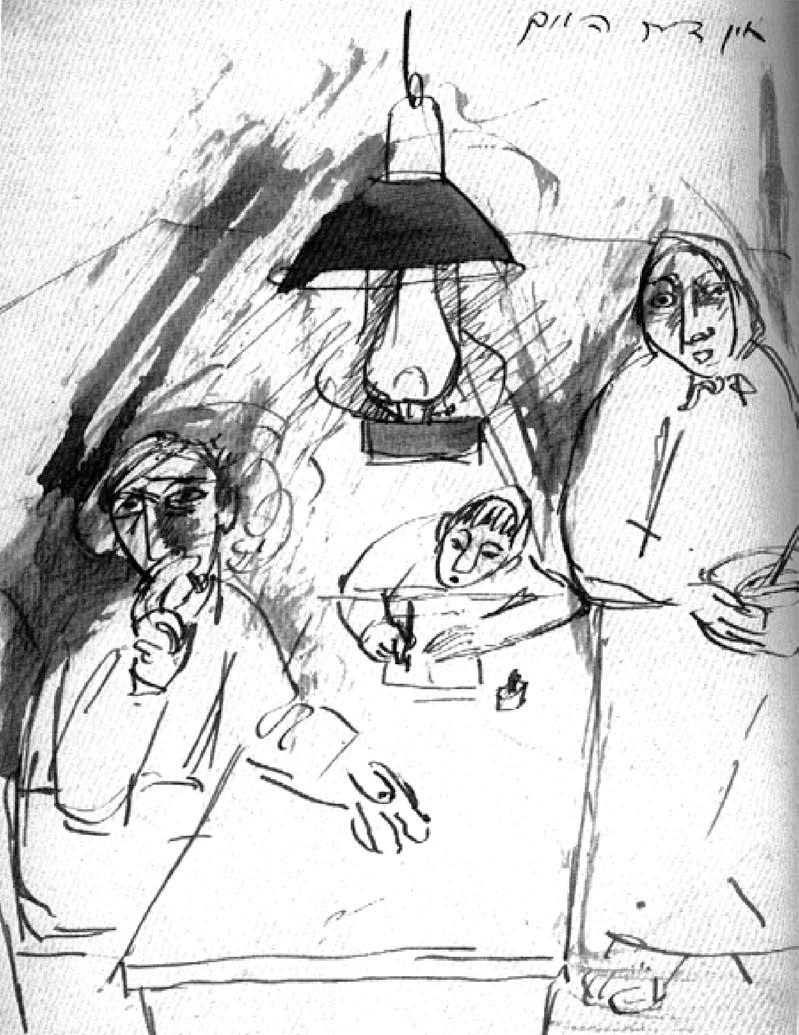

They arrived in the high summer of 1944 during the stillness of a hot afternoon and Herman immediately noticed the calm and quietness of the village. What deeply impressed him and what he comments on in the greatest detail is the nature of the light, golden and diffused through a warm copper coloured sky that reddened the stones of the cottages and the trunks of the trees. The stream under the bridge trickled out of a cold shadow, running over pebbles

that glittered as it flowed, emerging from the darkness and surrounded by a rich sparkling light. Herman was gazing in awe at the wonder of this scene, the strange composition and the strong contrast between the cold water and the warm light when suddenly and completely unexpectedly, a group of miners appeared on the bridge. They stood and talked and then turned and went their different ways.

Josef Herman might have spent the whole of his thirty-three years waiting for that one moment on the bridge at Ystradgynlais. The refugee from intolerance looked up and saw the sun set spectacularly behind the homecoming miners. In an instant all his anxious musings on life, humanity and subject matter seemed resolved in an overwhelming but glorious revelation that here was a way forward for his practise as a painter. The sun had silhouetted the men as great monolithic blocks, throwing into clear contrast the dark and essential matter of mankind and the life giving force of the sun setting behind them. In his autobiography Related Twilights he recalls that one dramatic experience as the seminal event of his entire creative life. After this epiphany in Ystradgynlais his south Wales paintings seemed to be entirely composed of that carboniferous mixture of sunbeams, coal dust and humankind.

The vision opened up his future path as an artist. In his written descriptions of the sight of those figures standing, talking and then parting on the bridge he portrays the miners as icons, silhouetted against and haloed by the golden arc of the setting sun. What he says he saw in the scene was sadness combined with grandeur and the acting out of something mysterious. He would probably have seen Christian icons during his younger days in Warsaw, particularly when he worked as a graphic artist and would, in any case, have been aware of them from his historical studies. It is also likely that the men on the bridge spoke in Welsh, a language he would have had no knowledge or understanding of, and this may have further emphasised their iconic status, their almost religious quality. In the days before nationalisation pithead baths were the exception rather than the rule and miners usually travelled home from the pit with the black colliery dust still encrusting their clothes and their faces. The homogeneity of the coal dust turned them into something a more than human, a more solidified object, thus further enhancing their otherness.

What Herman did not foresee was the huge impact the experience would have on his creative life. He describes the image melting into him. He sensed its enigmatic presence flooding through him filling the void created by that apprehensively awaited letter from the Red Cr oss infor ming him of the death of his family. Now we need to r ecall that statement of his made in London after he had completed the series of drawings begun in Glasgow. Following the dreadful news he had graphically exhausted his memory of the images and stories of his Warsaw childhood. When he looked at those images later he felt they must have been drawn by someone else. They were not, he thought, his own. “The nostalgia for my childhood years had burnt itself out and nothing had taken its place, except a vague feeling for big forms and a cry within me for a new belief in man’s ser enity.” Herman had felt empty, dispossessed and without hope. But on that warm summer afternoon, looking in amazement at miners on the bridge at Ystradgynlais he discover ed both. The lar ge, enduring for ms of the miners gave him the monumental images for which he had been searching. Simultaneously they awakened within him a new belief in man’s serenity.

Herman began at once to work with a revitalized sense of purpose and a new urgency. In his writing he describes working as though for the first time, such was the excitement he felt. He had always believed that effective art must be underwritten by a moral prerequisite. In Ystadgynlais and its mining community he recognised an appropriate subject and around it developed an objective as an artist that properly fulfilled this requirement. His Notes from a Welsh Diary, eloquently describe the experience:

“At first I spent entire days looking. I walked the small streets and the open hills where you can touch the sky. I also went down the mines, with a lamp on my helmet, a sketchbook in my hand … The River Tawe below, Craig-YFarteg above, in between the ground of daily life. Between waking and sleeping life like anywhere else, but nowhere else such a dreaming place… One sleepless night I recalled how much I liked walking in the dark woods outside Warsaw. There I often felt that having a soul and a mind I needed little else. In the years of perfecting my painter’s craft I lost that wonderful feeling. Now it is back … At five each morning I hear hobnailed boots on the road. I go to the window of my room at Pen-Y-Bont Inn. Miners in the dark going to work. Some look up to my light and lift an arm in greeting. When the echoes of the feet fade, I leave the window and go on with my work …”6

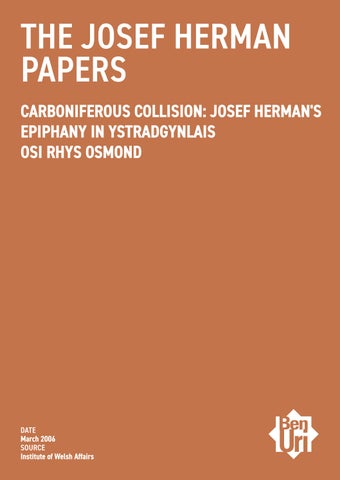

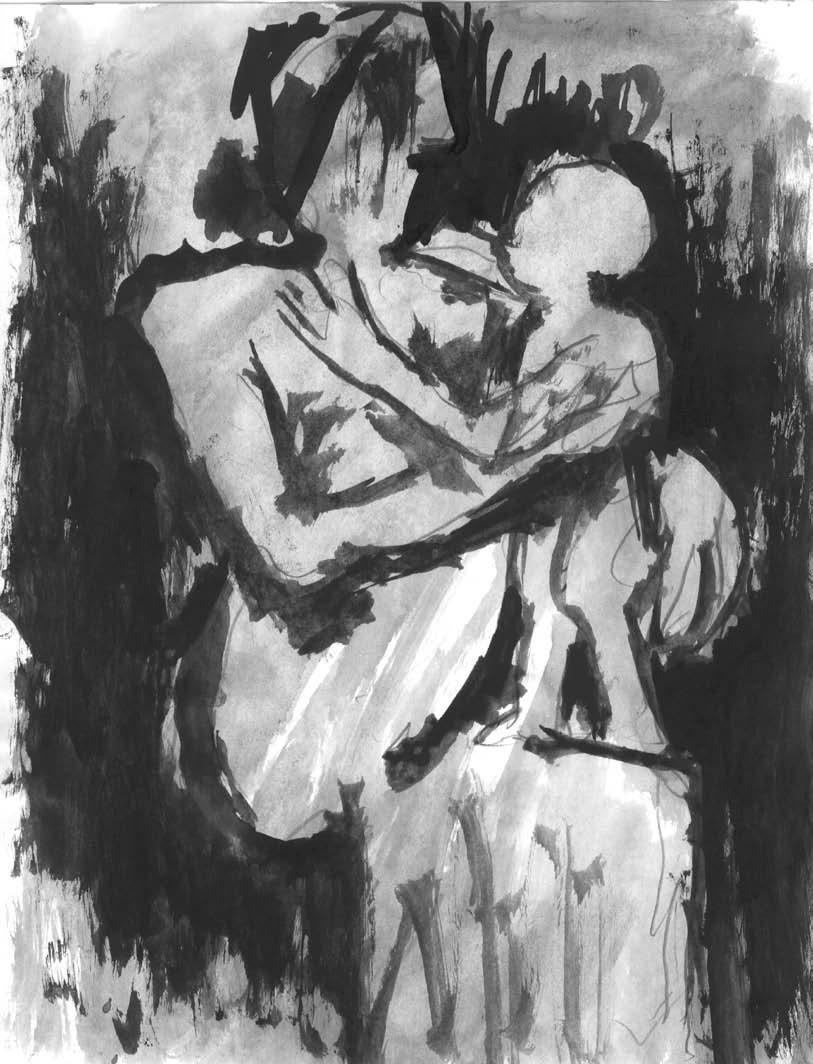

He began to work by drawing. At first he used charcoal, which, with its dense darkness and dusty carboniferous smudges reflects the mysterious qualities of the figures on the bridge. Later he resorted to ink which had an immediacy that responded in a seismographic way to his rapid and nervously urgent visual reactions. It flows in opaque pools, and can be watered down to create nuances of tone and shade. Moreover, it was black, like the fine particles of coal that covered his collier subjects.

These initial outpourings established a vocabulary of subject, form and design, creating a basis from which to work further. He now needed to introduce colour and to this end he used pastel, a medium that was new to him and around which he engaged in a great deal of experimentation, studying Degas in particular. Degas’s theories on under-painting and the use of colour were a great influence, although by taking his own liberties with them he managed to create an extraordinarily original intensity in his own pastels.

He worked this way for two years drawing in all three media and combinations of them before beginning to use oil paint. As a result of the practical understandings he first developed with pastels his subsequent paintings bear the same unusually luminous intensity. He felt his work was now beginning to function effectively, at least in formal terms. He was beginning to be able to create the elusive pictorial object he sought after. With the technical and aesthetic means effectively understood these could now join forces with his longstanding ambition to express the intrinsic symbolism rather than simply the observable actuality of his themes. He could expose what he saw as the idealism inherent in his subject.

Technical control was closely related to principled imperative in what Herman was seeking to achieve as a painter. Technique was important, although it must be liberating, “but it must always bend to the subjective needs of feeling and expression”. In the resultant oil paintings it is possible to see a more considered and reflective response to his theme as the concept becomes rooted physically and metaphysically in the object, which is the painting itself. He worked on a dark ground and built up a haunting luminosity in his images by the use of successive layers of glazes. Herman had also carefully studied the under-painting of the ‘old masters’ and he mixed this in his work with the direct painting first seen in 19th century Europe. This method creates a striated geology of paint depth, and the surface of the paintings throb with intensity as veils of warm colour and tonal subtleties reveal their richness as our eyes travel across them. The key areas, the defining features, are often applied in a strong impasto, with thick layers of vivid colour scumbled onto the surface, dragged and deposited with a sculptural flourish. These features are particularly noticeable in his single portraits of miners and mothers.

The washes sit, sensuous and diaphanous and are contrasted with tactile slabs of flat colour in key passages. The clear, decisive, final strokes define the artist’s intentions. By isolating a slash of light or bright colour that then dominates our reading of the image, he brings us back from our visual wanderings over the picture plain, to the primary focal point of the whole enterprise. Invariably this was connected to the significant human presence that they featured as their main focus. In this way the paintings organise and contain our emotional response to them. They are their own arbiters, and they move us by their own life force. We recognise the physical, emotional and intellectual power that brought them into being, and the final, tangibly physical application of the paint confirms and enhances the irrefutable nature of their subject’s presence.

The figures in the paintings are perhaps not easily identifiable as individuals, and this is one of the problems that the critic John Berger faced in his analysis of Herman’s work. Ironically, the Marxist critic wanted the individual, but was faced by the universal. Berger had reacted favourably to the paintings with the reservation that he felt they demonstrated a lack of commitment to social change. The paintings themselves are generous acts. Their manufacture is not frugal, the paint is lavishly applied and there is a luxury in their making which, in the austerity of post-war south Wales, must in itself have been something of a shock. We confront paintings that, as a consequence of the creative process that made them, resonate with a sense of history, and not just their own, but the whole history of the act of painting. The best of his mining images looked old, even in their newness. With their rich glazes and sombre light they carry an ancient patina which reflects their sense of immutability, reinforcing the permanence that Herman sought in his depictions of humanity.

In 1948 Herman acquired a derelict pop factory in Ystradgynlais which, in an era of relaxed planning controls, he was able to turn into a studio and home for himself and his wife. The studio became a focal point for meetings with other artists, intellectuals and political sympathisers. The Neath artist, Wil Roberts (1910-2000), was a frequent visitor. Very rapidly the account of Herman’s trajectory from Warsaw to south Wales through a momentous period of European political and cultural change became a means of enriching the lives of many other people. All those encounters and associations with artists and thinkers who had exchanged ideas and theories with the great figures of 20th Century European art were extended into the creative life of Wales.

It was in this year, 1948, that Herman became a British citizen and his personal history, work and experience made him a huge influence on the arts in south Wales. He became the focus of a great deal of media interest, at first locally and later across the UK. He was seen as a somewhat bizarre refugee artist who lived among the miners and braved the dangers and hardship of the colliery to make his art alongside them. These newspaper articles raised his profile and reflected the growing editorial interest in the south Wales coalfield during the late forties and early fifties. At that time there was an almost anthropological fascination with the culture of the mining Valleys. The colliery workers and their communities were seen as a strange, dusty and somewhat exotic species.

Documentary interest had begun somewhat earlier in the 1930s when many notable photographers, among them Bill Brandt and Edith Tudor Hart visited south Wales. In the same period Roosevelt’s Federal Works Administration Programme launched the huge photographic project that was to document the blighted industrial working class and rural life of depression America. Robert Frank and William Eugene Smith were among those who visited the Valleys in the 1940s. The documentary movement in Britain also began in the thirties and included the Mass Observation project begun by Humphrey Jennings and others. Again this was a photographic examination of working class life and as usual it was the coal industry that attracted the most attention.

Like many other large industries, including the GPO, the coal industry had its own documentary film and photography facility which continued as the National Coal Board Film Unit after nationalisation in 1947. Magazines in Britain and America also celebrated the miners as exemplary working men. The adversity of their life and employment demonstrated great

human dignity and optimism as well as political awareness and informed intellectual curiosity. The stark and dramatic south Wales landscape made an ideal visual laboratory for social enquiry. In this way the Welsh mining communities became convenient and attractive subject matter for documentation in photography, magazine editorial, literature and film-making.

These documentary productions produced expectations of the way working class mining life would be represented, expectations that also held good for painting and sculpture. The majority of the imaging of the subject was conditional on a possibly unconscious compositional conspiracy. In the absence of colour film it invested the working class experience with a grainy, gritty sheen. Strangely, these forms of documentation often provided a guide for how life should be lived, and sometimes the subjects’ own lives became constructed from the same compositional and dramatic values.

Life was not quite like that, not to my recollection at least. The colour and the vivacity were missing. However, Herman included them and as a result gave his subjects an iconographic power over and above the quotidian. Although these documentary representations were effective and moving, they dealt with a partially desired truth which was far from the reality.

An even bigger question was the value or even the justification of placing documentary image-makers into a culture of which they had little knowledge and could only view as spectacle. However well-meaning, they were largely middle-class privileged, strangers and their views could always be seen as condescending. This dilemma exercised many a good Marxist mind. In Herman’s case he overcame the problem by virtue of his foreignness, his politics, and his personal integrity, quite apart from his remaining in the community for such a long time. Then, of course, was the work itself. His representations strove for something quite different from that of other artists and especially from the documentary makers. This difference was partly acknowledged in the questions raised by the Marxist critic, John Berger, who, it appears, felt Herman had substituted revolutionary fervour for quiet acquiescence. Herman’s authenticity was to be found in the power of the sympathetic expression he engendered in his images. His paintings rose above the so-called truth of the photo-documentary image which, of course, was nothing of the sort anyway. The camera is complicit in the way that it records. It is not neutral or objective. It responds readily to the preconceived agenda of the photographer.

As well as these documentary films and photographs Herman’s paintings were the pictorial corollary to a surprisingly large number of feature films from the forties and fifties. Among them were Humphrey Jennings’s 1943 Silent Village and Jill Craigie’s 1949 Blue Scar which dealt in part with the recent nationalisation of the coal industry. The latter was a much more socially aware film than the earlier, romantic but popular Proud Valley from 1940 which starred Paul Robeson or the cloyingly sentimental How Green was My Valley (1941). Adapted from the 1939 novel of the same name by Richard Llewellyn (1906-83) this last was set in Wales, but shot in Hollywood. Both novel and film represented the miner and his community in a very particular way, generally putting the collier forward as a focus for social stoicism combined with a jaunty radicalism. Many of the best mining novels were by writers whose own experiences informed their stories. One of the most objective was A.J. Cronin’s The Citadel written as a result of his work as doctor in Tredegar and Treherbert. This also featured as a film by MGM, directed by King Vidor in l938.

The poet Idris Davies (1905-53) came from mining stock and worked underground before training as a teacher in the depression of the late 1920s. His poetry was underwritten by moral outrage and anger at the indignities suffered by his people. He wrote Angry Summer in 1943 after he had been evacuated to Northants with his East End school. His highly pictorial poetry was an inspiration to many in its visualisation of the vicissitudes of valleys life. Rhondda born Gwyn Thomas, (1913-81) wrote humorous novels with a serious political undercurrent illustrating the adventures of characters from the mining valleys. Jack Jones (1884-1970) and others from mining backgrounds added to a large body of writing depicting life in and around the colliery.

These multiple representations of the miner, in a range of media, are critical in considering the imaging of the miner prior to and during Herman’s south Wales sojourn. In contrast Herman’s work takes a very different path from these accepted ways. He elevated archetypal figures to iconic status by means of expressionist handling. His painting filter ed through a range of profound and deeply emotional experiences on his journey to Ystradgynlais.

Partly as result of the depiction of the plight of the mining communities, but mostly as a result of developing political will, a sustained campaign begun during the early forties changed the Welsh political climate. Westminster responded to pressures to consider ‘the problems of the future government of Wales’ and for the establishment of a Welsh Office with a Secretary of State and a seat for Wales in the British Cabinet. At first this call was rejected by the post-war Labour Government. Wales had to wait until 1964 for Jim Griffiths, himself an ex-miner, to be appointed as the Charter Secretary of State for Wales. However, the lobbying led to the more immediate setting up of the appointed Council for Wales, and the Welsh Joint Education Committee in 1948, followed by a Minister for Welsh Affairs in 1951. Earlier, in 1946, David Bell had been appointed as Regional Officer for the Arts and had begun to direct his considerable energies into constructing a coherent policy for the creation and dissemination of the visual arts.

As the new Labour administration began to put into place the structures by which a more equitable society could be created the whole climate of cultural provision and patronage in Wales began to slowly change for the better. More important exhibitions toured to Wales and artists began to enjoy a growing prestige within the life of the nation. In 1953 Bell was to become the Assistant Director of the newly formed Welsh Arts Council and later keeper of the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. He was a key figure in the British arts establishment and always a strong advocate of Herman’s work.

As a consequence of these political changes the range of arts provision and consumption began to br oaden and a critically appr eciative public patr onage developed. This was largely, though not exclusively, built around a socially conscientious middle class. Institutions like the BBC, the Health Ser vice, the newly nationalised industries and the universities developed purchasing and display policies that fostered a growing awareness of the visual ar ts and suppor ted fledgling ar tists. But, as Peter Lor d obser ves, “Nevertheless, more than any other single factor, it was the sustained critical interest in Josef Herman which raised the public profile of the artist’s view of the life of Welsh industrial communities”. 7

7)Peter Lord, The Visual Culture of Wales, Industrial Society, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1998.

Living in the wake of the decline of heavy industry and with in some ways a more developed visual art scene, it may be difficult for us to understand the impact that the work of Herman had on the public imagination. Complemented by images in other media his paintings of miners and their families consolidated and celebrated the humanitarian values of an entire community. For some observers, Herman’s figures of the miners had an iconic power. Not just descriptive, much more than documentary, his figures elevated and idealised the working man and his labour as secular toilers in a sacred human cause. This was not to every ones taste. The Marxist art critic John Berger, for example, felt that the artist “substituted endurance for hope”. Many of the subjects themselves were unimpressed by the work, tolerating Herman and his images, but seeing little of value in them, other than curiosity

Berger may have been more perceptive than he realised when he talked of the “endurance” of Herman’s figures. For a man who had spent almost his whole past life slipping away from institutionalised persecution, the physical permanence of the figures he saw and the group solidarity of communitarian culture which the mining tribe represented, held a confirming and continuing life force, which recent European history had devalued and even denied. In Ystradgynlais Herman sensed optimism, purpose and decency. If he was to ever find a subject that spoke adequately of his own fears and hope for humanity, here it was. In many ways it seems as though Herman was rediscovering what he himself had lost, a community which was to become his family, representing the lost principles of interdependent living and shared values.

His friendly conversations with the miners confirmed this feeling and he was surprised by the intimacy of the culture and the speed of his acceptance. Arriving, as a stranger, becoming ‘Joe’, and then ‘Joe Bach’ all within two days, confirmed his affection for the place and the warmth of the people. The political and social philosophies of the community were close to his own and in these ideals he found a common and developing bond. Following the defeat of Fascism, south Wales was buzzing with the excitement of a new political order. And in the heady optimism of post-war Britain, the real and important priorities of the community were becoming ascendant over the interests of capital. The pits were soon to be nationalised and a health service that placed the medical needs of the patient at the top of the agenda was on the way.