Architectsand Furniture

Edited by Neil Spiller and Ashley Simone

Architectsand Furniture

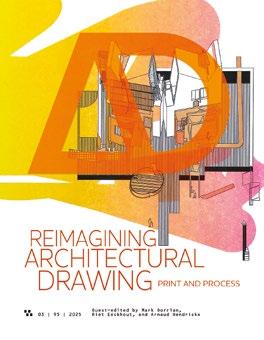

| 95 | 2025

Edited by Neil Spiller and Ashley Simone

1 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

SEPTEMBER 2025

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editorial Offices

Axiomatic Editions, an imprint of ORO Editions

250 Bowery

New York, New York 10012

Editorial Director

Ashley Simone

Editor

Neil Spiller

Managing Editor

Caroline Ellerby

Contributing Editor

Abigail Grater

Publisher Gordon Goff

Assistant Production Editor

Sarah Fingerhood

Design

Artmedia Ltd, London

Front cover

Nigel Coates, Gallo collection, Poltronova, Florence, Italy, 1989.

© Poltronova, photo Carlo Gianni

Inside front cover

Stuart Munro, Traumatic Furniture, 2000

© Stuart Munro

Page 1

Kiki Goti, Nuphar Mirror, 2024.

© Vetralia Collectible

VOLUME 95 | ISSUE 02

Denise Bratton

Paul Brislin

Mark Burry

Helen Castle

Nigel Coates

Peter Cook

Kate Goodwin

Edwin Heathcote

Brian McGrath

Jayne Merkel

Peter Murray

Mark Robbins

Deborah Saunt

Patrik Schumacher

Jill Stoner

Ken Yeang

Disclaimer

The Publisher and Editors cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this journal; the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Publisher and Editors.

Journal Customer Services

For ordering information, claims, and any enquiry concerning your journal subscription please go to www.archdesignjournal.com

Print ISBN: 978-1-961856-98-1

Print ISSN: 0003-8504

Online ISSN: 1554-2769

Institutional

$950 print and online

$850 print only

$850 online only

Individual $190 print and online

$160 print only

$120 online only

Individual issues

$40

All prices are subject to change without notice.

All content of 2 and archdesignjournal.com is copyright Axiomatic Editions and may not be reproduced in any manner, either in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE EDITORS

NEIL SPILLER AND ASHLEY SIMONE

Architect and Editor of 2 Neil Spiller is based in London. He was Visiting Professor of Architecture at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada (2020–22) and Visiting Professor at IUAV Venice in 2021. He was previously Hawksmoor Chair of Architecture and Landscape and Deputy Pro Vice-Chancellor of the University of Greenwich, London. Prior to this, he was Dean of the School of Architecture, Design and Construction and Professor of Architecture and Digital Theory at Greenwich, and Vice-Dean and Graduate Director of Design at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London (UCL).

His architectural design work has been published and exhibited worldwide.

He has guest-edited eight 2 issues, including Architects in Cyberspace I and II (1995 and 1998), and Drawing Architecture (2013), and more recently edited the issues Emerging Talents: Training Architects (2021), Radical Architectural Drawing (2022), California Dreaming (2023), and, with Aleksandra Wagner, Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years (2024). His books include Visionary Architecture: Blueprints of the Modern Imagination (2006), Architecture and Surrealism (2016), and Educating Architects (2014), all published by Thames & Hudson. He is also the author of How to Thrive in Architecture School: A Student Guide (RIBA, 2020).

He is the founding director of the Advanced Virtual and Technological Architectural Research (AVATAR) group, which conducts research into the impact of advanced technologies such as virtuality and biotechnology on 21st-century design.

Educator and Editorial Director of Axiomatic Editions Ashley Simone is based in New York City, where she teaches and works on books and other publications about architecture and design.

Ashley is an Associate Professor at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture and a Lecturer at the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona.

Her writing has appeared in numerous books and journals published by 2, Actar, BOMB Magazine, Lars Müller, ORO Editions, and Thames & Hudson. Select essays include “Polymorphic Matters” in 2 Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years (2024), and “Value and the Metaphor of Phenomenology” in the anthology Modern Architecture and the Lifeworld (Thames & Hudson, 2020), edited by Karla Britton and Robert McCarter.

Among other books on architecture and design, she is the editor of Kenneth Frampton’s A Genealogy of Modern Architecture (2015), Allan Wexler’s Absurd Thinking Between Art and Design (2017), and Michael Webb: Two Journeys (2018), all published by Lars Müller, and Frank Gehry Catalogue Raisonné, Volume One, 1954–1978 by Jean-Louis Cohen (Cahiers d’Art, 2020), and The Other Modern Movement by Kenneth Frampton (Yale University Press, 2021). 2

Text © 2025 Axiomatic Editions. Images: (t) © Robbie Munn; (b) © Willis Roberts

An Intimate

Are You Sitting Comfortably?

Relationship Then I Shall Begin …

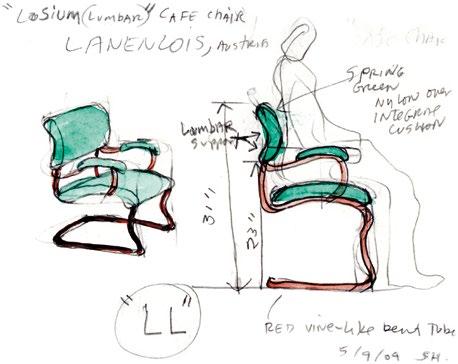

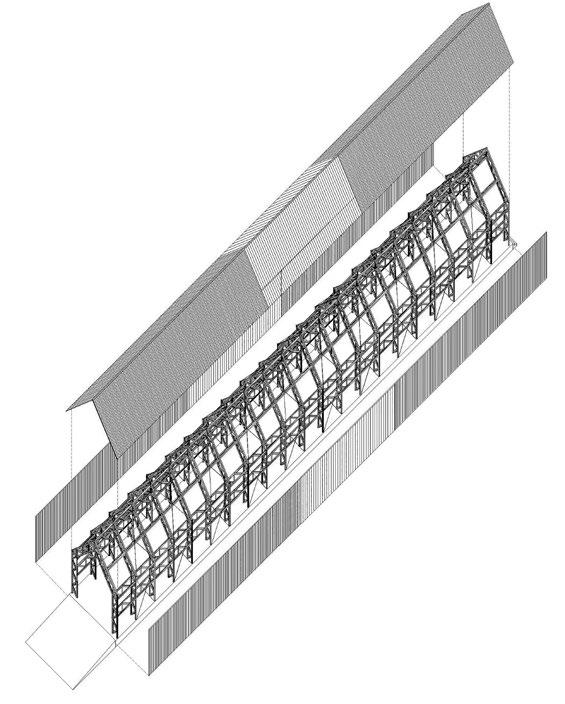

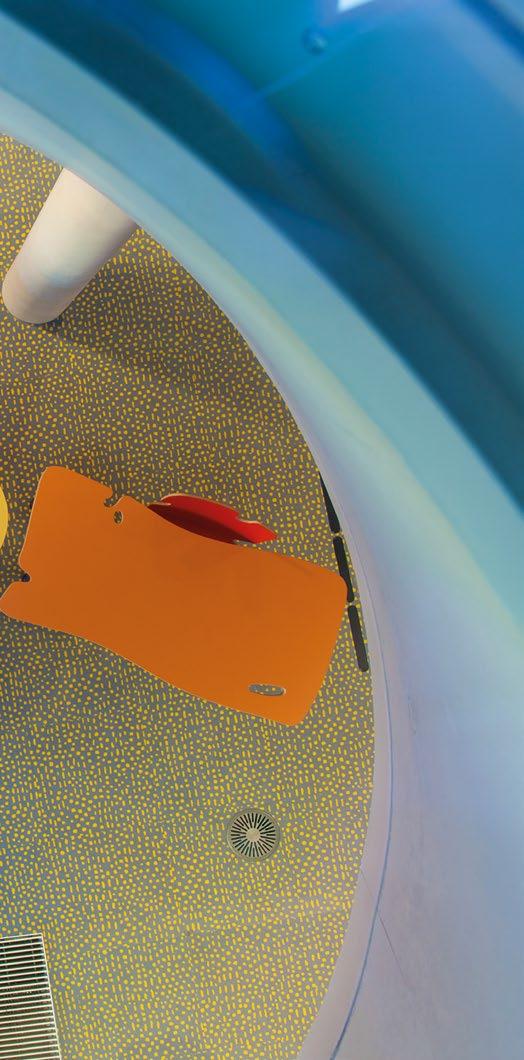

Moxon Architects, Mull chair for Tacchini, Milan, Italy, 2007

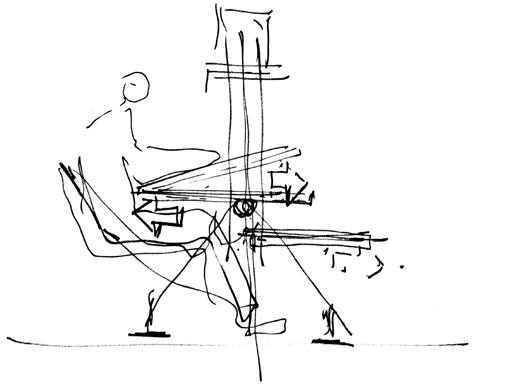

The Mull chair was the result of a competition win in 2006. Manufactured by design brand Tacchini, it consists of post-formed lacquered plastic shells skinned with upholstered suede padding. It has a removable and deployable footrest that at other times can be stored in the underbelly of the chair.

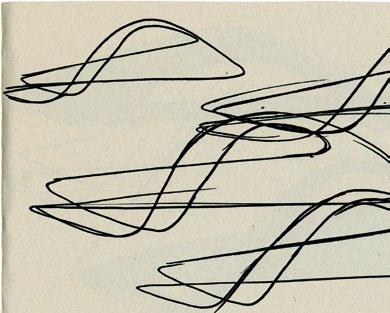

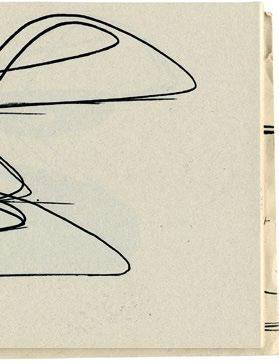

: An initial design sketch by

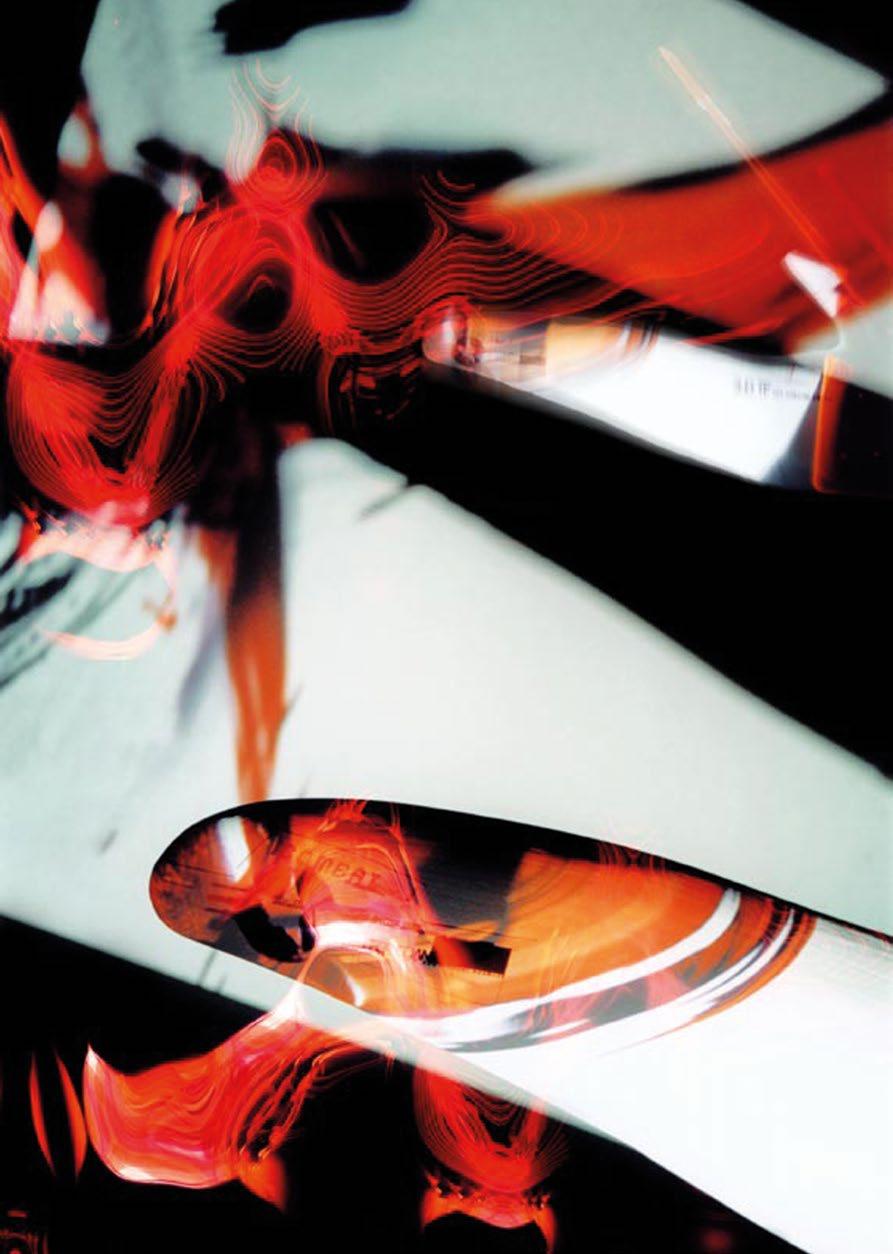

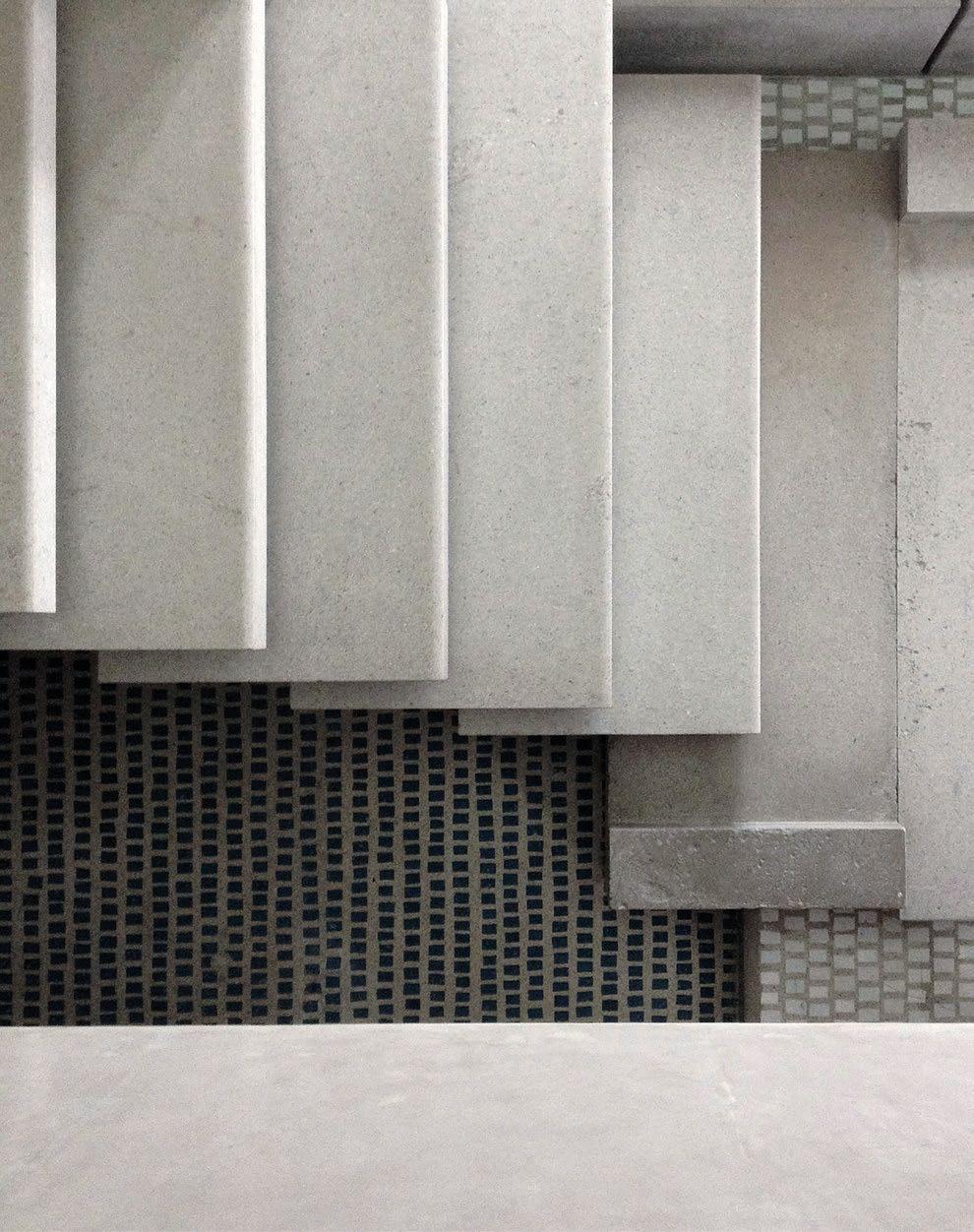

opposite top : The Nomos table can be part of a modular office system or can be deployed as a one-off. The table’s design language is one of rejoicing in its material efficiency and its beautiful structural economy.

Of all the relatively inert objects we haptically experience in our lifetimes, the relationship between our flesh and our furniture is perhaps the most intimate. While architecture can be seen as providing a protective environmental carapace around our bodies, furniture is about ergonomically cosseting and making these bodies comfortable in repose—particularly in the case of chairs, tables, and beds. Likewise, when we engage with the fabric of buildings, via handrails, door furniture, and the like, we find elements that are tailored to our human grip. Architects have often been fascinated by this close intimacy between body and design. Their interests in furniture can on one level create a displacement design activity in times of sparse architectural work, or conversely pander to their sense of creating the complete holistic great work where their architectural prowess and lexicon is explored and demonstrated at all scales—furniture is the ideal vehicle for such endeavors.

This edition of 2 commences with Sandy Jones, Assistant Curator of Architecture and Urbanism at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). Through examples in the V&A’s collection, her article “If an Architect Were a Chair” considers why architects cross over into furniture design, how they apply their design thinking to smaller-scale projects, and the ways in which their furniture and building projects share a distinct design language. Examples include pieces by Marcel Breuer, Nathan Silver, Venturi Scott Brown, and Ron Arad. It traverses through varied stylistic preoccupations—Adhocism, Postmodernism, and Mid-century Modernism among them.

Canadian architect based in Los Angeles, Frank Gehry, needs no introduction: he and his office have developed a signature approach to designing buildings and artifacts that are at once complexly curvilinear and breathtakingly inviting. Likewise, his maverick furniture exploits the curvilinear and is highly inventive. Vanessa Grossman, Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, explores some of these designs and their materiality. She focuses on Gehry’s “Easy Edges” series of chairs (1969–73), constructed from cardboard as a way of playing creatively to understand the material’s qualities and exploit them. Different but similar in its exploitation of its constituent materials, this time glass and steel, is Foster + Partners’ Nomos table (1987), which pushes its materials to high-tech limits.

Dada and Decon

In the 1980s a new exuberance seemed to invade furniture design, particularly that posited by architects. They explored using different materials in different ways and playfully, often distanced from the structural expediency of designers like Norman Foster. One such rising star was Zaha Hadid. Before completing any of her subsequent building projects, Hadid designed furniture and products for a handful of companies across Europe, America, and Japan. Like her interiors and exhibition designs, her furniture designs functioned as templates for trying out architectural strategies. Hadid believed that the satisfaction of designing products is that the process between idea and result is so quick and uncomplicated compared to a building. In terms of form, though, design and architecture interested her equally—there is a useful dialogue between the two. For her, design objects were fragments of what could occur in architecture. What were the key design strategies? How did these collaborations come about? And in what ways did furniture design shape Hadid’s career in architecture more broadly? Johan Deurell—curator, researcher, and latterly of the Zaha Hadid Foundation—investigates.

Like his friend Hadid, London- and Tuscany-based architect Nigel Coates is known for his extravagant and arresting buildings as well as for his domestic products that include furniture, lights, rugs, and vases. Some examples have a baroque playfulness, some an amorphous voluptuousness, and some a Modernist organic purity, or sometimes a mixture of all three and more. His work is eclectic, sensuous, tactile, and welcomingly amenable, as he rejoices in the movements and interactions between the human body and his pieces. Each item is narratively and imaginatively named to evoke its conceptual inspirations. Here he takes us on a journey of discovery that started during a period parallel to that of Hadid’s.

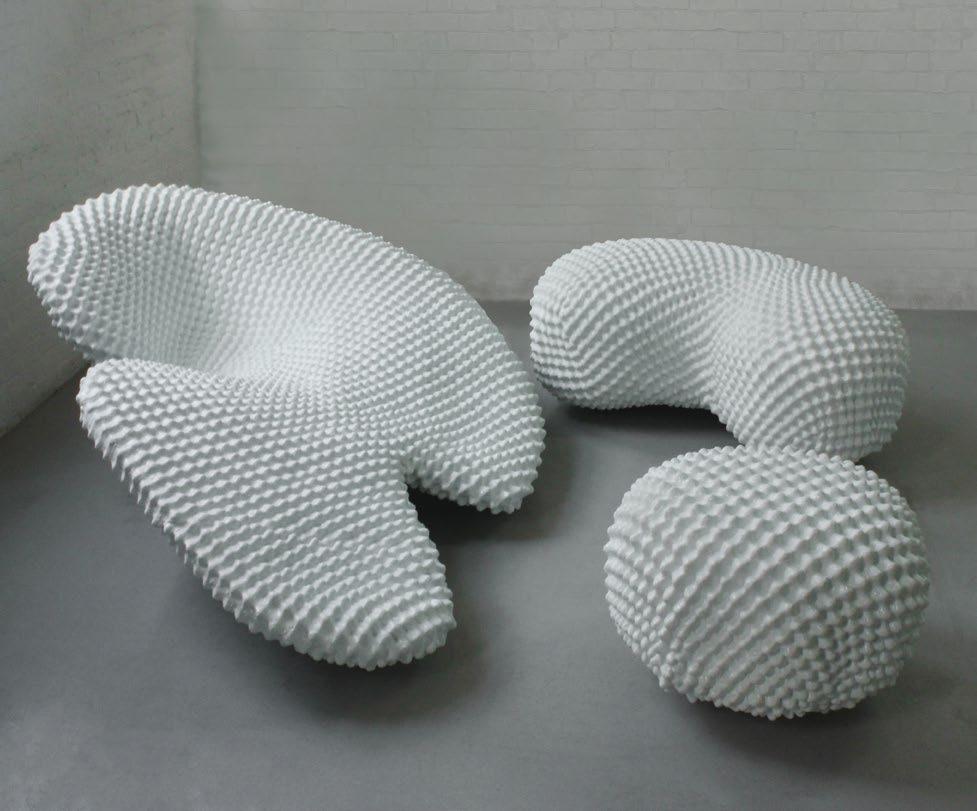

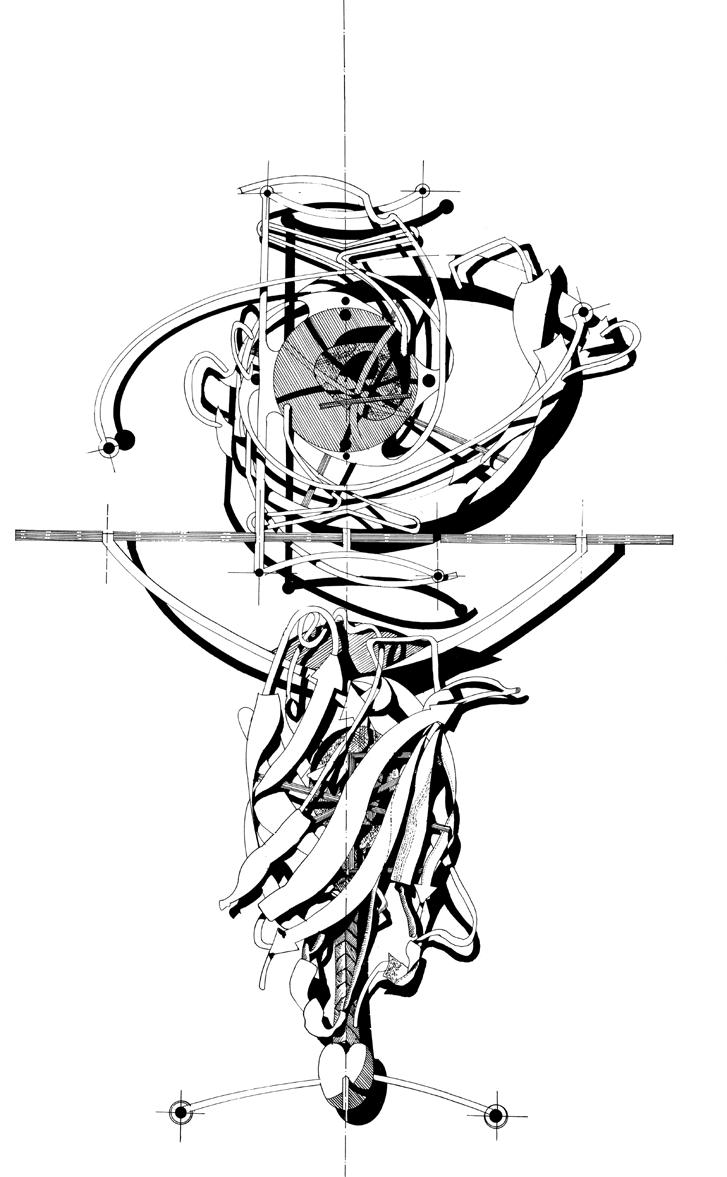

Similar to Hadid and Coates, at the same time in New York, Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto were developing and exploring their own unique architectural lexicon through their fledgling practice, and articulating and manifesting their architectural ideas in highly surreal furniture pieces for both interior and exterior spaces. They developed and constructed a suite of designs informed by literary but mainly off-piste writings such as Alfred Jarry’s ’Pataphysics and Raymond Roussel’s Impressions of Africa (1910). This already heady mix of associations is further

Foster + Partners, Nomos table for Tecno, 1987

right

Norman Foster showing the Nomos table in various articulations.

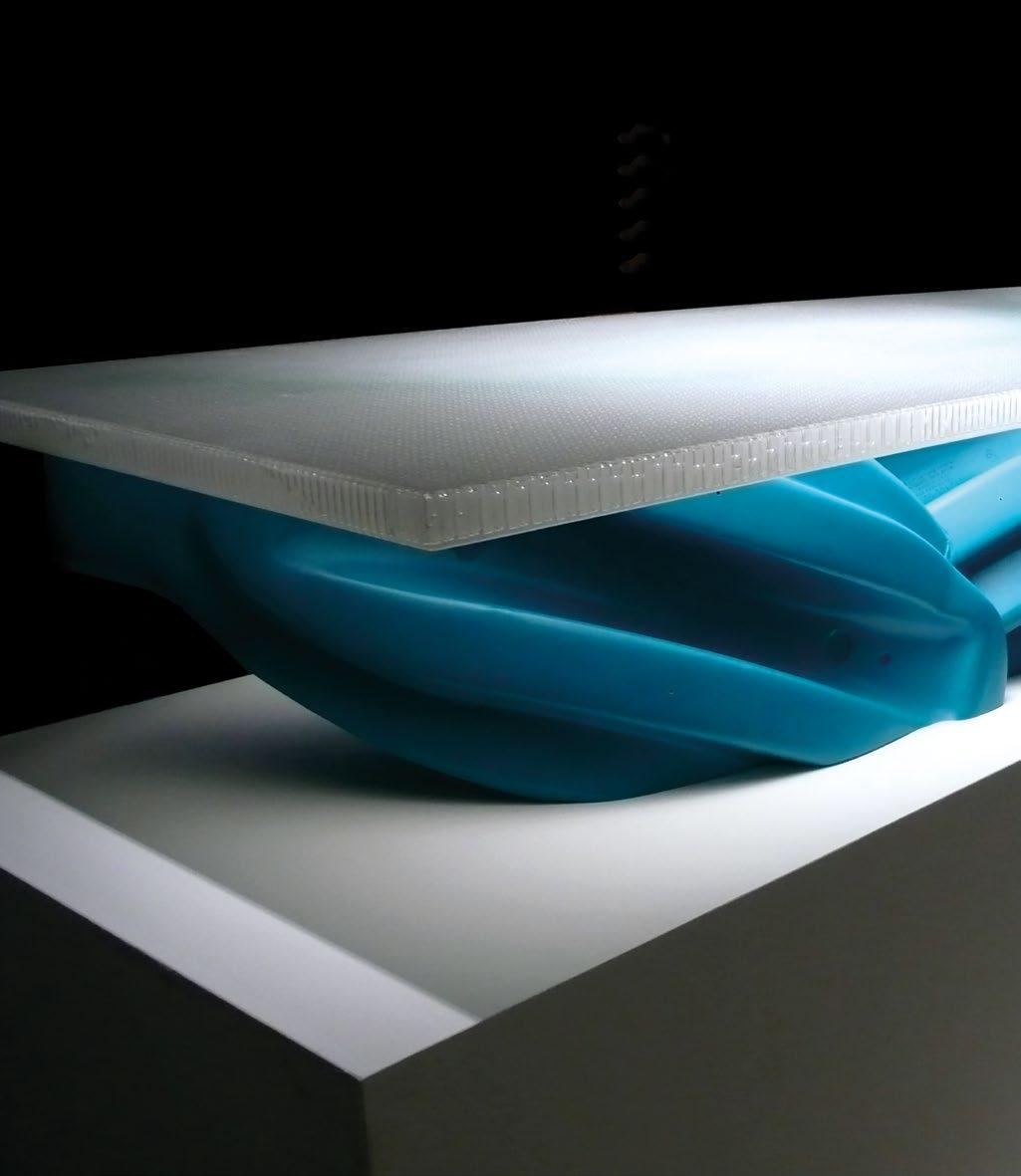

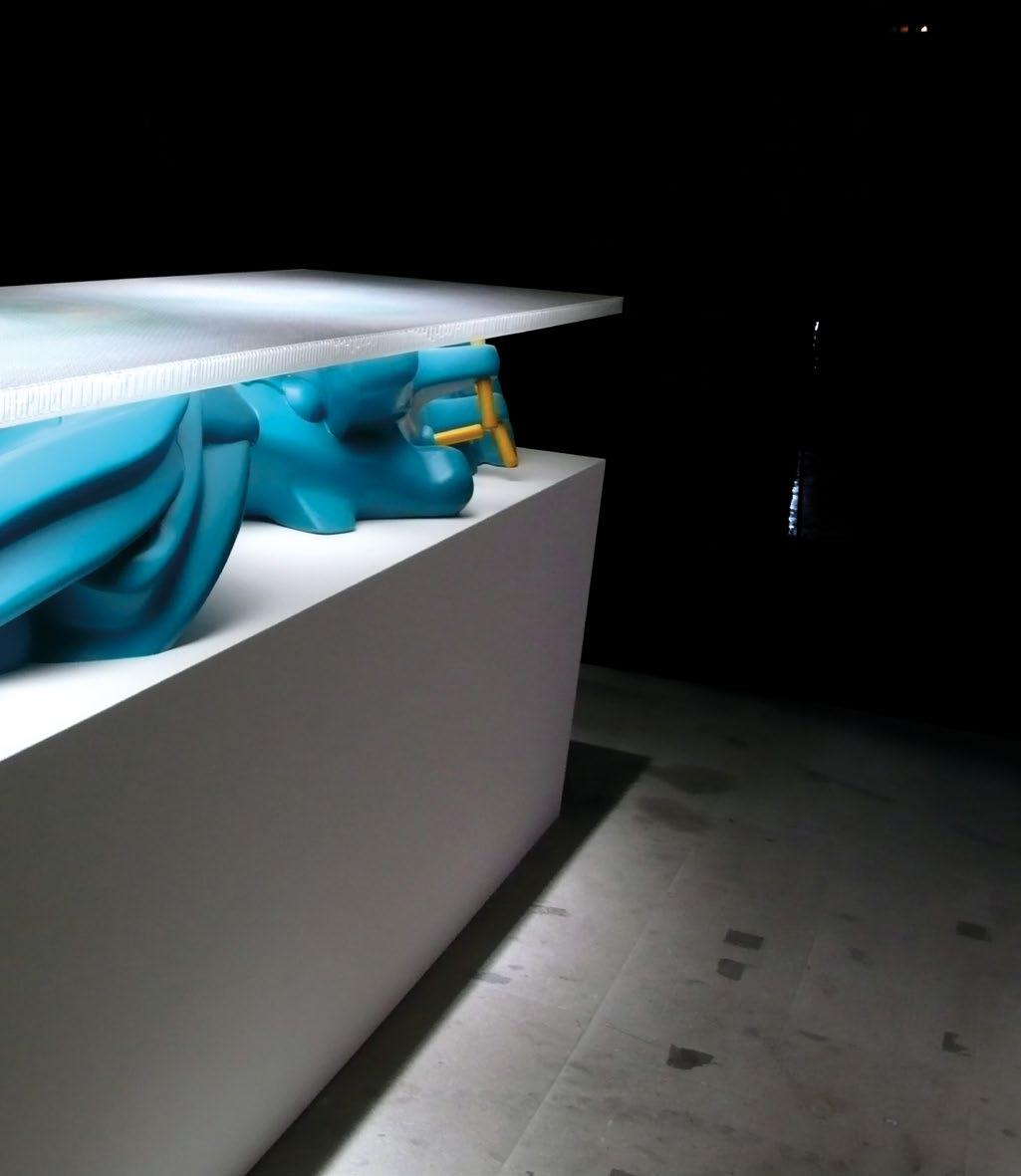

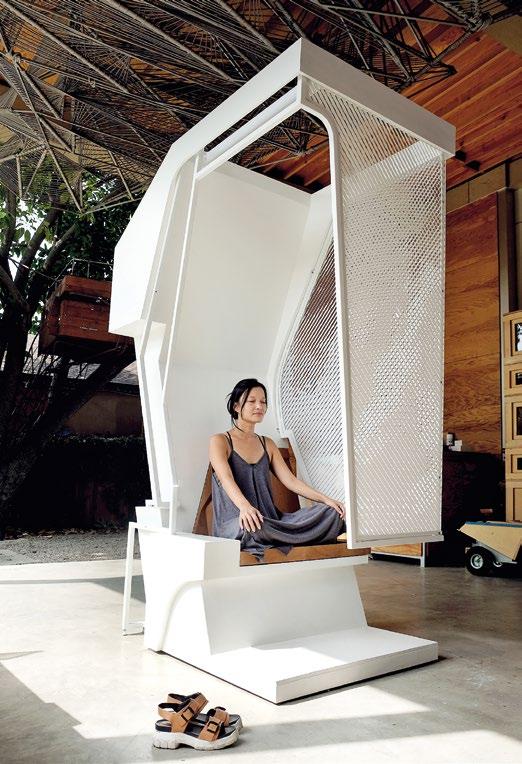

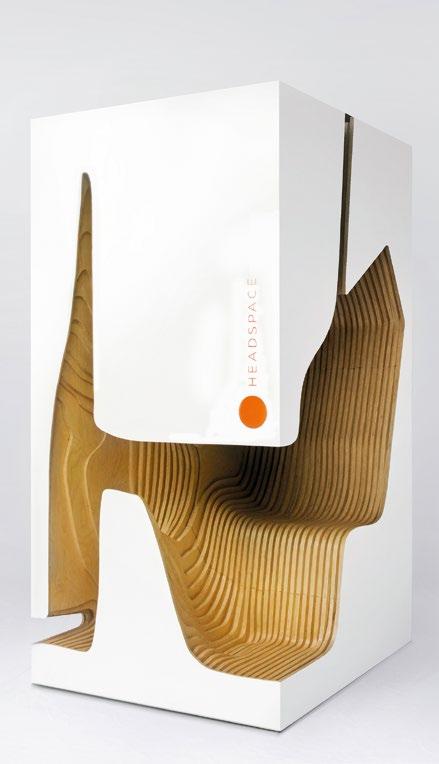

Reiser+Umemoto, RUR Architecture, Lounge Chair, New York, 2018

below : Like many architects, the architectural and artistic lexicon of Reiser+Umemoto has changed and developed over the years. The Lounge Chair is an ecology of amorphous forms that can be used in multivalent ways. The composite skin was stretched and compressed to generate the appearance of a seamless tailored topology with local gradients.

augmented with visual references to Dada artist Marcel Duchamp’s works, architect Daniel Libeskind’s vectors, and architect John Hejduk’s lyrical presences, thereby creating highly original and strangely beguiling architectonic performative forms.

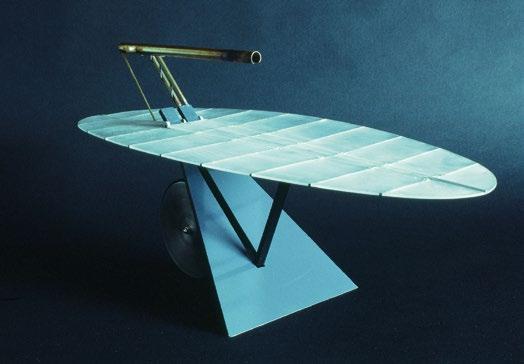

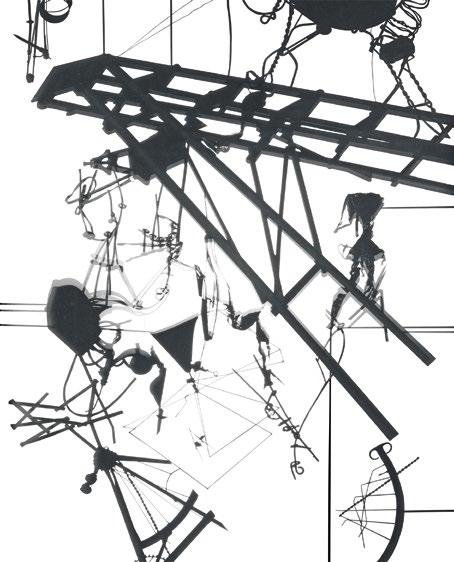

During this period, other Dada/Surrealist-inspired architects such as Ken Kaplan, Ted Krueger, and Christopher Scholz produced metallic furniture more akin to vehicles and airplane forms inspired by shoes, insects, human limb prosthetics, and fish, to name but a few of their influences.

As the 1980s decade waned and the avant-garde of the architectural profession was gripped by the stylistic and formally liberating nihilism of deconstruction, Morphosis cofounder and Angeleno Thom Mayne and others designed the Nee chair (1989)—a Deconstructivist symphony in miniature. Each element of the chair, whether seat, backrest, or leg, was individually designed and composed, and then joyfully joined together with a celebration of such junctions—again a manifesto piece for buildings yet to come.

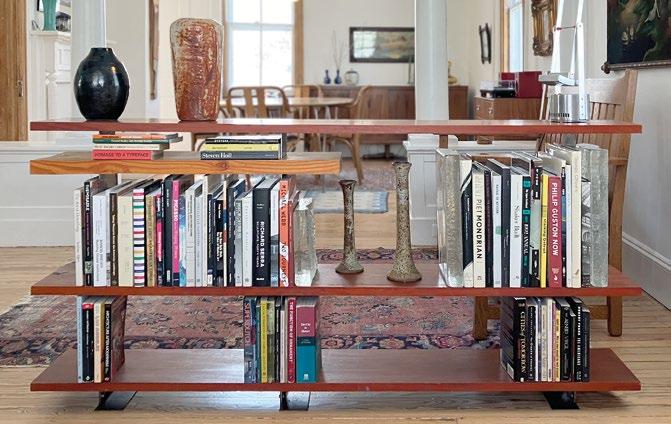

Multivalent Design

An architectural firm that has been highly successful and yet, while practicing all over the world, has also managed never to let go of the small-scale joyful product and its conceptual relationship with the larger whole, is New York-based Steven Holl Architects (SHA). Producing furniture and fittings that resonate with the same rigor and joy as the practice’s buildings and their spaces, they have a reputation as multivalent designers adept at trying their hand at all manner of design scales and products. Dimitra Tsachrelia Holl—Principal at SHA—runs us through some of their recent design escapades in this respect.

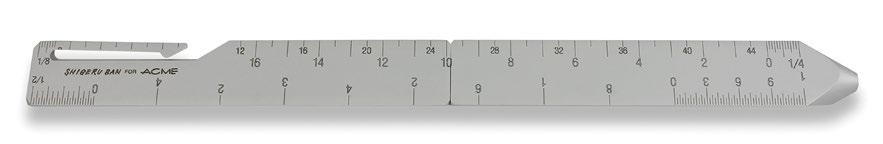

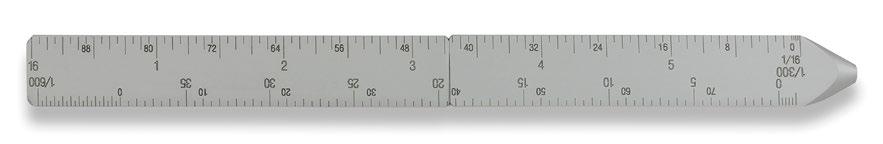

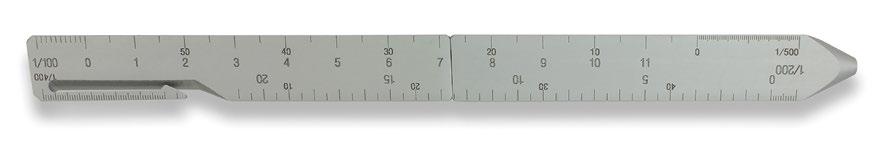

Similar to SHA, Japanese architect Shigeru Ban and his practice have a reputation for designing buildings and furniture that can be viewed as three-dimensional poetry. The work has a presence that does not celebrate and expose its structure in the way that, for example, Norman Foster’s Nomos table does, but structure is integral to Ban’s designs, part of their holistic material geometry. Ban’s long-time partner Dean Maltz, who leads the New York office, describes this design approach and its outcomes. Like Gehry’s “Easy Edges” furniture, the experimentation with materials pays dividends and offers a designed, gentle humanity to architecture and products alike.

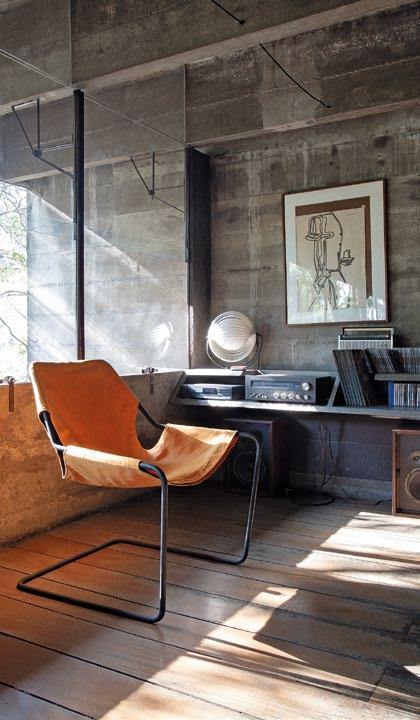

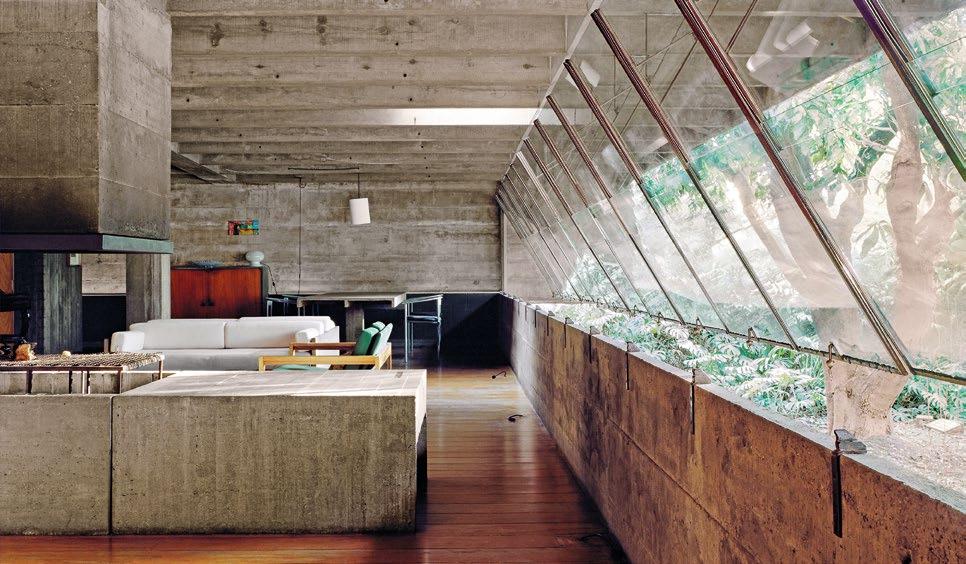

We then travel to Brazil, and alight on the work of Paulo Mendes da Rocha who, during a lengthy career, made a great contribution to many of the cultural buildings in São Paulo and is often referred to as a Brazilian Brutalist. He augmented such architectural endeavors with furniture designs, illustrating his multivalent design lexicon and bringing it down to the bodily scale. He was an original and instantly recognizable architect. Guilherme Wisnik is a tenured professor and Vice Dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo. His article focuses on da Rocha’s emblematic Paulistano chair, originally designed in 1956.

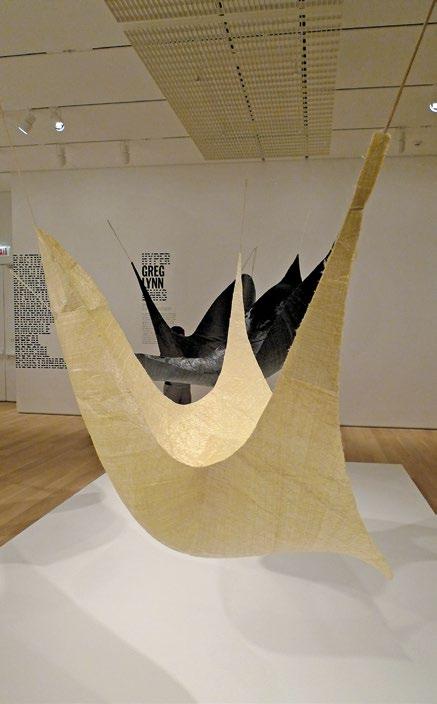

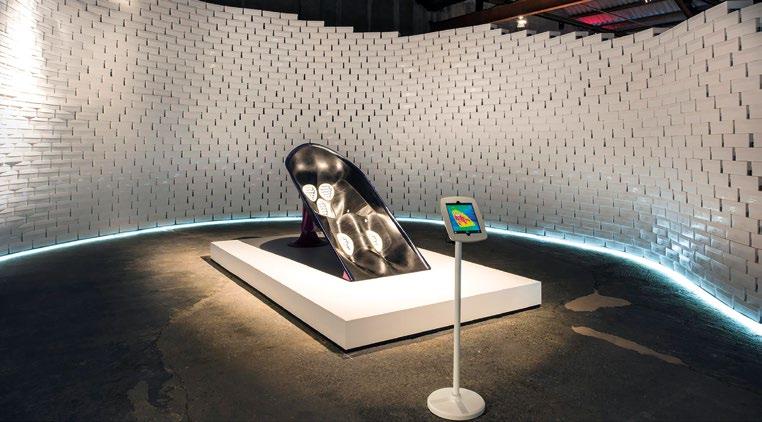

All good architects exhibit a design philosophy that sees creative opportunities in all manner of materials, technologies, and original applications, and turning received design logics on their head. New York-based architect John Szot examines some of the forays into furniture by Los Angeles architect Greg Lynn and his creative design methodology that makes whatever he tries his hand at result in distinctly different outcomes from project to project.

Recently

In recent years, Amanda Levete and her London-based firm of architects AL_A have created some audacious works of furniture alongside some stunning buildings. The practice’s work always has a fluid dynamism about it, again instantly recognizable at any scale. Design writer William Richards investigates their productbased oeuvre and interviews Levete in a wide-ranging and insightful conversation.

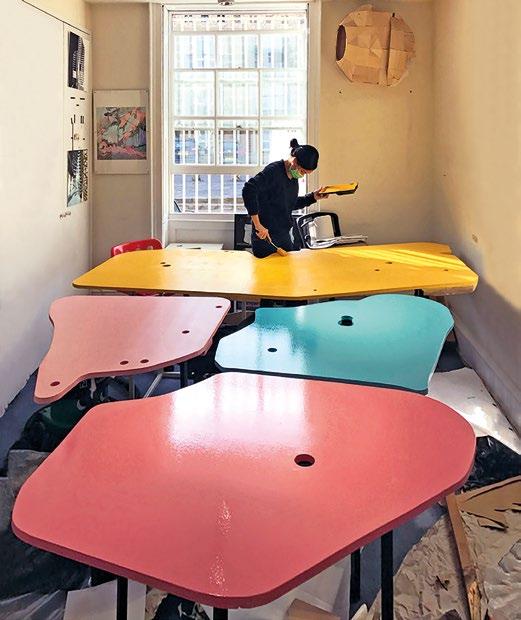

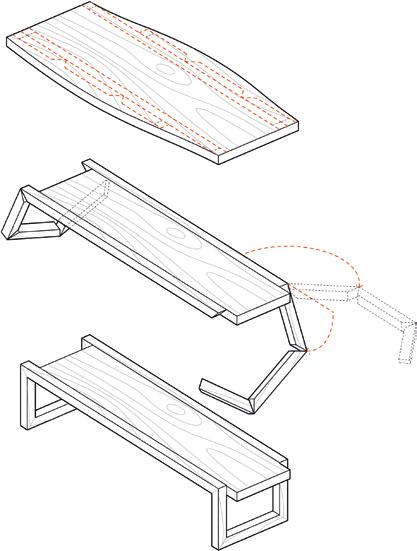

CRAB Studio has had a longstanding preoccupation with designing tables, originally instigated with ex-fellow office founder Sir Peter Cook. While AL_A’s furniture utilizes curves and contemporary materials and technologies, CRAB Studio’s tables are simply made and designed yet still have a quotidian beauty. The tables populate some of CRAB’s built projects such as the Abedian School of Architecture at Bond University, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, and have the designed-in ability to cluster together, if need be, in various combinations. Member of the CRAB office Eoin Shaw describes their evolution, their progeny, and their ongoing metamorphosis.

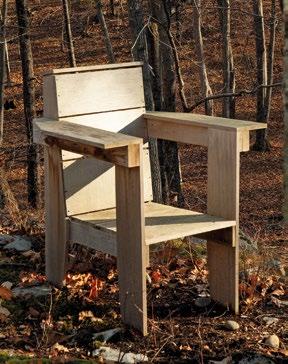

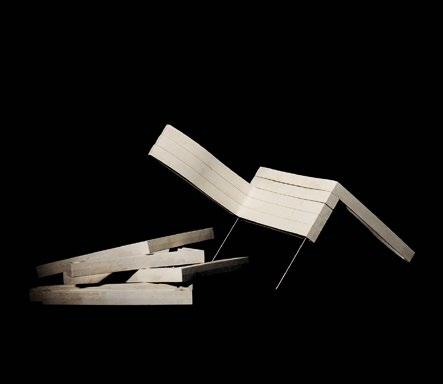

In another act of quotidian lateral thought, University of Arizona School of Architecture faculty Carrie Eastman explores a trajectory of work by the architect and industrial designer Andrew Skey, beginning with a static wooden slab and progressing to dynamic constructs. The narrative moves from a table to a shelf to a pared-down skateboard: a rideable piece of wood.

Ken Kaplan and Ted Krueger with Christopher Scholz, Crib-batic, 1986

opposite : This children’s stroller is conceived as a vehicle for stimulation and as a tool cart, with the capacity to move through space and to present the child with a selection of tools to aid in exploration. These tools, rich in reference to simple mechanics and elemental material, were selected to be especially stimulating to the absorbent memory and intelligence of a three-year-old.

Morphosis (Thom Mayne with Kazu Arai, Craig Burdick, and Paul Burnsweig), Nee chair for Tom Farrage & Co., 1989

top : Another example of the inventiveness of the late 1980s that architects injected into furniture design. Morphosis’s Nee chair showcases the then-fashionable “Deconstructivist” aesthetic, with elements finely articulated relative to each other.

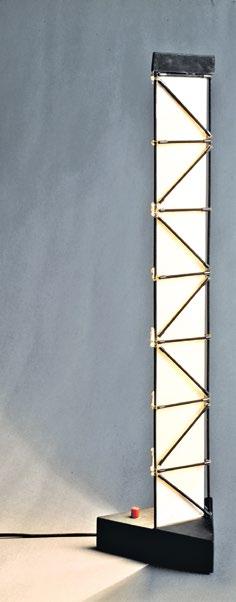

Christopher Scholz with Ken Kaplan and Ted Krueger, Lamp-Table, 1986

left : This design proposes that furniture be both transforming and dynamic, changing states and locations to fulfill different functions. When horizontal, it is a table capable of seating six people. Its leaves can be folded up and raised vertically to become a mobile standing lamp. Materials include translucent Lexan polycarbonate, aluminum, brass, and rubber.

Some architects not only design furniture for others to make but also make it too, sometimes taking a more artisan approach yet utilizing contemporary methods of jointing, prefabrication, computer-aided materiality, and forming. Los Angeles architecture practice Oyler Wu Collaborative has a remarkably hands-on design ethic. Jenny Wu also designs jewelry; all their design outputs at whatever scale are highly articulated, finely detailed and honed. Over recent years they have worked on furniture pieces both in the private and public realm. Todd Gannon, Professor of Architecture at The Ohio State University’s Knowlton School, describes Oyler Wu’s approaches to such designs, their material palette and fabrication techniques.

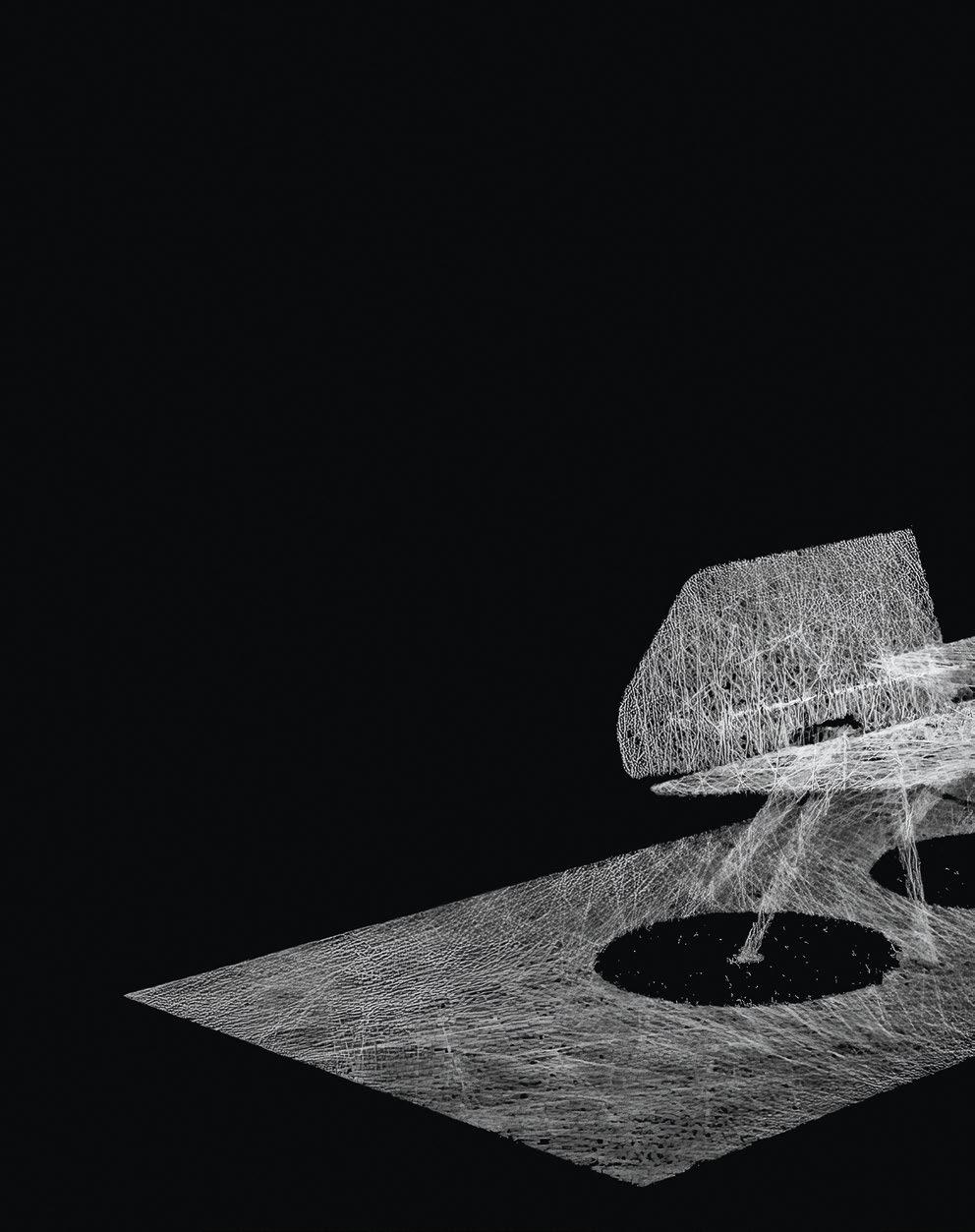

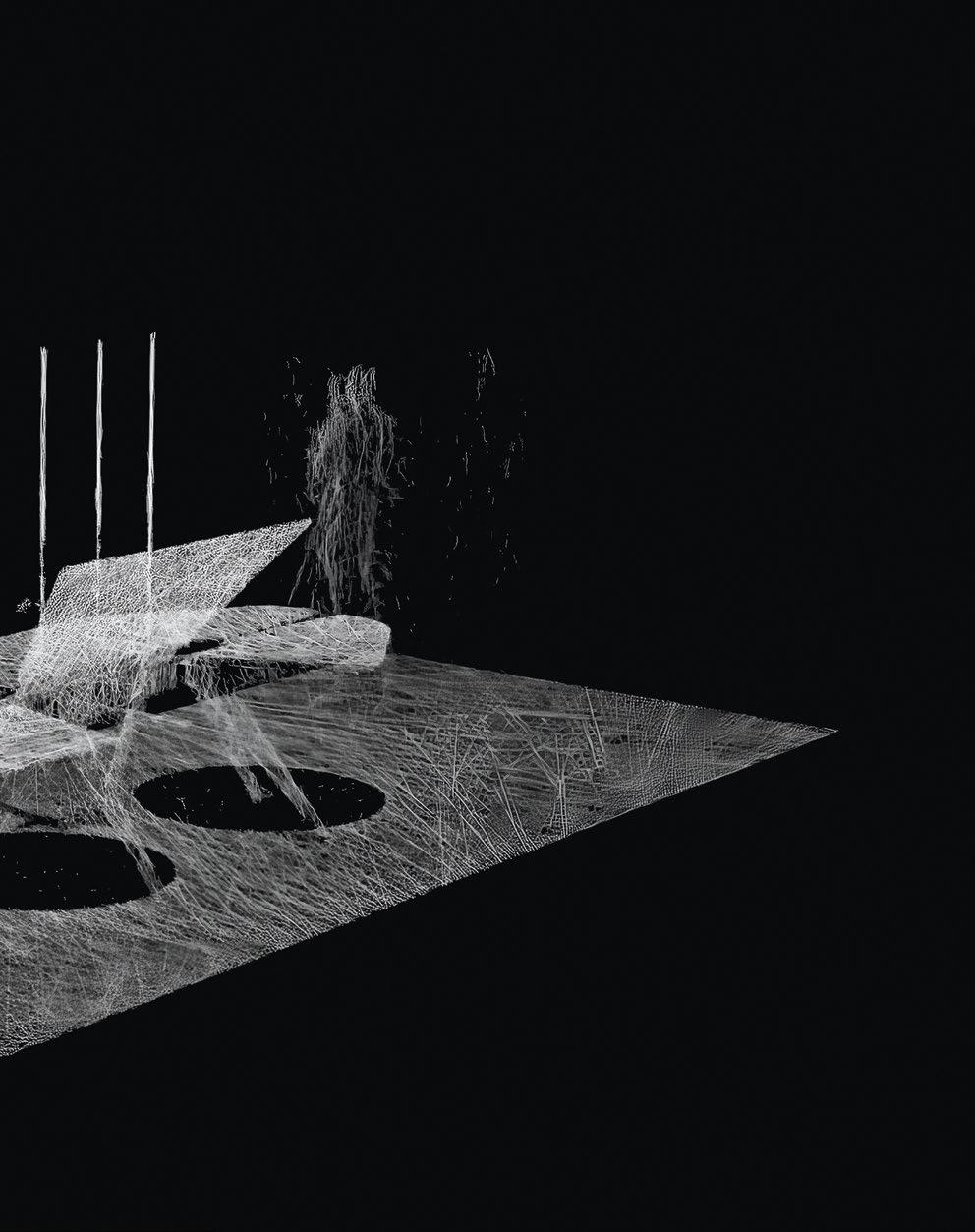

Digital Anatomies

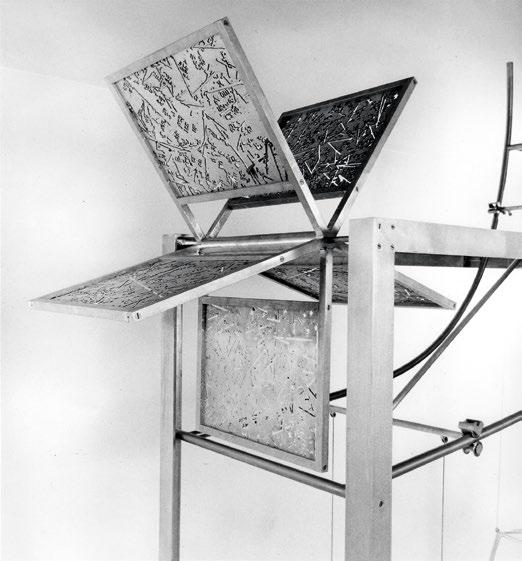

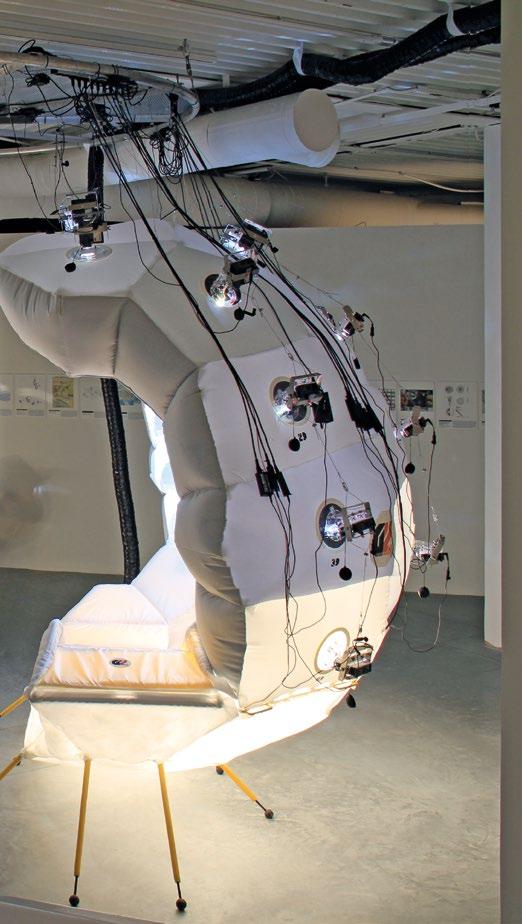

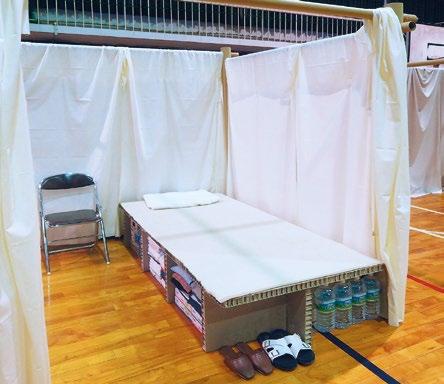

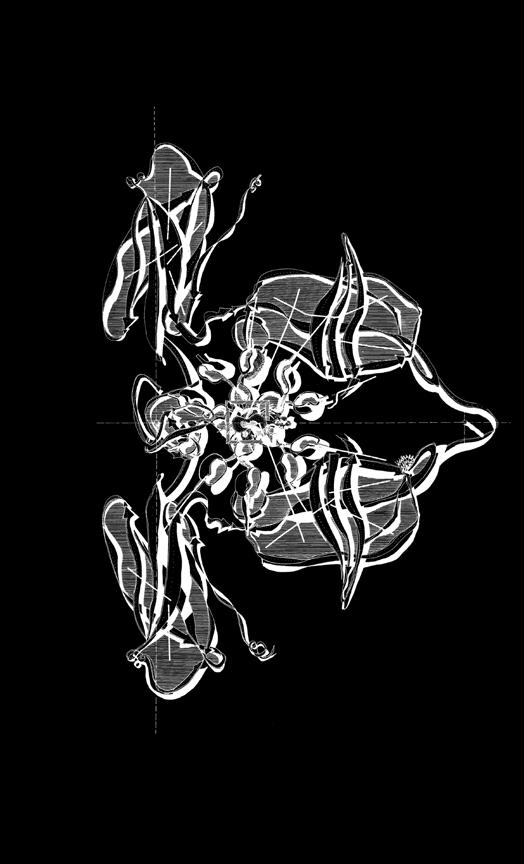

The synthesis between digital sensing and dynamic furniture, particularly in relation to the Internet of Things, is only now being explored and exploited. The potential of such technologies can create motive furniture designs, able to have a sense of themselves and the shifting context that they find themselves within. This notion consequently offers a new terrain in which furniture designs can become much more dexterous, accommodating differing, even digital, anatomies—as for example in the Traumatic Furniture (2000) designed by Stuart Munro in the final year of his studies at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

What happens when a table is designed to incorporate all manner of technologies, is adaptable, and operates at many differing scales both conceptually and contextually? 4/16 Architects, steered by architect Nick Elias, a design tutor at the University of Greenwich in London and principal of his own architectural practice, have posited and built such a table. Elias explains the motivations behind this project and its beginnings, uses, and material consistency.

Stuart Munro, Traumatic Furniture, 2000

opposite : When a final-year student at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, Stuart Munro developed a series of furniture forms that could be used to lay on, sit on, eat off, etc. Each piece surfed on an invisible “energy carpet” that provided each furniture element with a sense of itself and its relationship with its peers. Once a new piece was introduced in the room, the others would readjust accordingly like magnets in a box finding a new state of equilibrium.

Ramiro Diaz-Granados and Heather Flood, C-Hub table, Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Los Angeles, 2008

is

organic

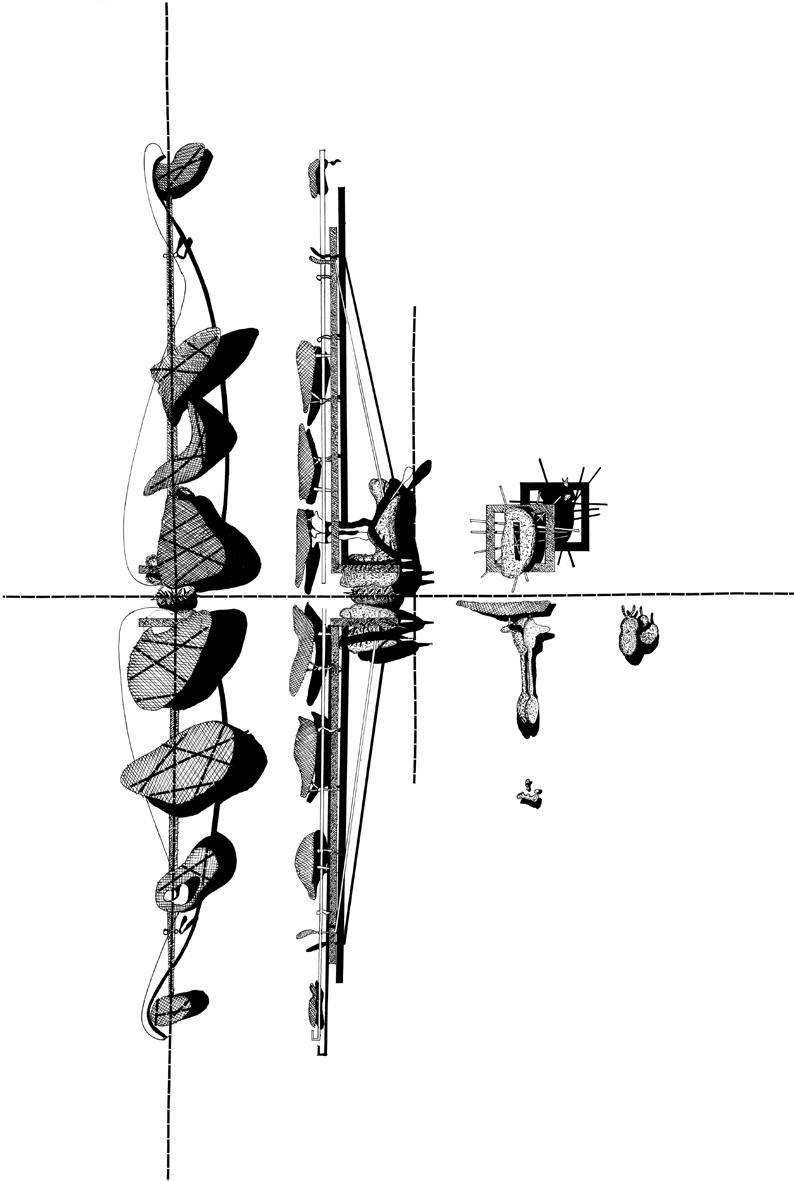

Other furniture can be inspired by nature: the petals, buds, leaves, or the bloom of flowers. A good example is Ramiro Diaz-Granados and Heather Flood’s almost triffid-like Board of Directors table for the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in Los Angeles, called C-Hub (2008). While organically symmetrical, it is also wired—a fixed centerpiece cossets the main computer equipment. Around this central core are positioned 11 potentially independent “Chubbies”—outer sections that have their own internet, and USB ports. The whole is alive digitally as well as aesthetically. The table provides a focal point to the Kappe Library at SCI-Arc, with students and staff dismantling and reassembling the table for their own transient purposes.

Another designer who has a mechanized organic aesthetic is Greek architect and New Yorker Kiki Goti. Her furniture and fittings work has a certain vitality, almost blossoming into rooms, creating a sense of uncanny cyborgian nature. The pieces are often constellations of brightly colored materials—modern but rejoicing their almost Postmodern formal qualities.

Finally, the organic quotation and inspirational approach is continued in my own forays into furniture design; some made it off the drawing board, others didn’t. The set featured in this issue takes inspiration from biological forms found in nature: some microscopic, others not.

This 2 illustrates the profound breadth and originality architects have brought to furniture design. While our selections are not exhaustive—nor could they be in a publication of this size—we have endeavored to provide the reader with a comprehensive and chronological spectrum to delineate the broad scope of contemporary architects and their furniture-related preoccupations and triumphs.

The hope is that these microcosmic architectural sojourns into slightly different realms will themselves motivate and inspire a new generation of architect-designed furniture.2

© Foster + Partners, photo Peter Strobel; p. 9(b) © Reiser+Umemoto, RUR Architecture; pp. 10, 11(b) © photos Christopher Scholz; p. 11(t) © Morphosis, photo Jasmine Park; p. 12 © Stuart Munro; p. 13 © Photo Ramiro Diaz-Granados

left : This seemingly organic design

a contemporary retake on Art Nouveau formmaking and

inspiration, yet with machine-cut, layered build-up and a mobile modular construction.

Sandy Jones

Marcel Breuer and F.R.S. Yorke, Ventris living room at Highpoint One, London, 1937

For art collector Dorothea Ventris’s apartment in the Highpoint One block designed by Berthold Lubetkin and his Tecton group, Breuer and Yorke envisioned the finished interior with woven tatami-style wall panels and furniture arranged around a centrally placed floor heater. In the foreground is Breuer’s Long Chair (1936), influenced by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto’s earlier seating furniture designs.

If an Architect Were a Chair

Furniture as an Extension of Architecture Collections

Architects’

engagement

with furniture design has a long and illustrious history. Sandy Jones, Assistant Curator of Architecture and Urbanism at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, considers a few examples of “Mid-century Modern” design held within its collections. She gives us a quick tour of architects’ different stylistic approaches during the latter half of the 20th century.

The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in South Kensington, London, is home to the national collection of architecture and holds models, drawings, and sketchbooks by some of the best-known architects from the 15th century to the present day. Architecture’s history is visible throughout the museum, from its Architecture Gallery and monumental Cast Courts to large-scale architectural fragments and reconstructions of historic rooms. The new V&A East Storehouse features the only complete Frank Lloyd Wright interior outside the US, the office he designed in 1937 for Pittsburgh department-store owner Edgar J. Kaufmann.

Architects are also responsible for the design of furniture in the collection, including one of the most historically significant, technical, and highly visible pieces of furniture in society: the chair. As an opportunity to experiment with structure, form, materials, ergonomics, and aesthetics on a small scale, the chair is unrivaled. As designer-maker and curator Huren Marsh observes, “you can put a lot into it, which you wouldn’t put into other furniture.”1 What motivates architects to design chairs, and how do the design elements of their buildings and chairs intersect? Six chairs in the V&A’s collection offer some valuable insights and trace the history of modern furniture design.

Early “Mid-century Modern”

Although he always thought of himself as an architect, the HungarianGerman Modernist designer Marcel Lajos Breuer spent the first years of his career designing furniture and interiors. Breuer graduated from the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1924 and returned as Master of the carpentry workshop in 1925 when the school moved to Dessau. He is best known for his tubular steel furniture, particularly the Club Chair Model B3 (1925–6), much later marketed as the Wassily Chair. In 1934, following the school’s closure the previous year by the Nazis, its former director and Breuer’s mentor, Walter Gropius, emigrated to London to form a partnership with architect Maxwell Fry. With an uncertain professional future in Europe, Breuer followed Gropius, arriving one year later to work as a partner to architect F.R.S. Yorke. Breuer stayed for less than two years before following Gropius again, accepting an appointment to teach architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design. His work in England, however, made a significant impact on British architecture and design.

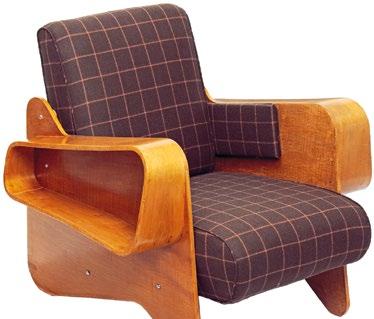

As part of a commission to design an interior in a Modernist style for art collector Dorothea Ventris’s apartment in Highpoint One, North London—which was designed by Berthold Lubetkin and his Tecton group in 1935—Breuer designed a pair of armchairs and a matching sofa to furnish the living room. Produced by P.E. Gane for Isokon, for whom Breuer worked and designed numerous pieces of furniture, they were made from large, cut-out plywood sheets for the frames, and feature molded armrests with distinctive plywood loops attached to the arms for storage and display. Breuer’s decision to design curvilinear architectural pieces in preference to the severe geometry of his tubular furniture reflected, in part, the need to soften his earlier designs to suit British taste, which favored the warmth of wood, as well as a material and production method cheaper than tubular steel. The origins of what has come to be called “Midcentury Modern” design are clearly visible in Breuer and Yorke’s interior, which was part of a trend toward biomorphic shapes evoking the natural world that emerged in the avant-garde art of the 1930s.

During this period, Breuer worked with F.R.S. Yorke on several buildings that served as testing grounds for his architectural ideas. A notable project was the design of the Gane Pavilion at the Royal Agricultural Show in Bristol in 1936, where he incorporated regional, even rustic, materials to express a more accessible Modernist aesthetic.

This period of experimentation and change in creative direction would be seen in the interiors and armchairs he later designed for the Pennsylvania Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

Marcel Breuer, Armchair for the Ventris flat, London, England, 1936

The chair is made from sycamore-veneered plywood and the side panels are cut from flat sheets, using a template.

Breuer’s decision to design curvilinear architectural pieces in preference to the severe geometry of his tubular furniture reflected, in part, the need to soften his earlier designs to suit British taste, which favored the warmth of wood

The 2024 V&A exhibition “Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence” highlighted how architecture became intertwined with postcolonial independence and nation-building in India and West Africa during the 1940s and 1950s. Following India’s independence from British rule in 1947, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru commissioned Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Maxwell Fry, and Jane Drew to build a new administrative capital, “unfettered by the traditions of the past,” in Chandigarh, northern India. The project also aimed to become a training ground for local architects.

Eulie Chowdhury was India’s first female architect and the only Indian woman on the Chandigarh project team. A fluent French speaker, she was responsible for designing the Home Science College, the Women’s Polytechnic, and several houses for government. She also prepared drawings for Le Corbusier, and designed furniture, including the Library Chair for the Palace of Justice, although she has not always been credited for her work. The chair’s design reflects the functional simplicity and geometry of her brick buildings. Local teak and cane were used to make the chairs in the workshops

surrounding Chandigarh. Today, these humble chairs, regarded as design classics due to their association with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret, command high prices, with the origins of their design and manufacture mostly overlooked. The Chandigarh Chairs project seeks to fill the gaps in the story of Chandigarh’s Modernist furniture and critically examine its construction and dissemination.2

Eulie Chowdhury, Le Corbusier, and Pierre Jeanneret, Library chair and Officer’s chair, Chandigarh, India, 1950–55

Eulie Chowdhury adapted Le Corbusier’s universal system of proportions, based on the average French man’s height, to design furniture for smaller frames. Fifty years later, after the 2005 refurbishment of Chandigarh’s Palace of Justice, the chairs appeared for sale on the open market.

“Ad Hoc” and Playful Pastiche American architects Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver’s influential book Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation (1972)3 explores the practice of “bricolage” in both everyday material culture and professional design. Challenging the formality of Modernism and the notion that true innovation only originates from “eureka” moments, it urged architects and designers to take pleasure in designing ad hoc by working with resources immediately to hand for the “resolution of present needs.” Viewed as a core Postmodern text, its themes and early examples of recycling strategies have become increasingly important in subsequent years and the book was updated and reprinted by the MIT Press in 2013.

The Ad Hoc chair (1968) is one of the most memorable and well-known furniture designs of that period. Made entirely from improvised parts, it was designed to solve a problem in a particular context. Having refurbished the dining-room floor of

his Cambridge, England, home with a rough brick paving, Silver wanted seating that would not be damaged or produce a scraping sound when moved. His solution was to design a chair mounted on wheelchair wheels with a frame made from gas piping, bicycle axles and bearings for the wheels, and a chrome-plated tractor seat attached by auto-bumper bolts. Silver comments, “my architectural training with primary structural and materials knowledge instigating ideas that I developed, has always inevitably come into critical play for me when I’ve designed the likes of chairs, tables, restaurant trolleys … .”4

Venturi Scott Brown (VSB; now VSBA) are among the most influential architects of the 20th century, known for their architecture and contribution to Postmodern theory, including their seminal work Learning from Las Vegas (1972), co-authored with Steven Izenour.5 Denise Scott Brown describes their design approach, which includes cross-cultural and historical research, as “a troika: we

move between observing-studying, designing, and theorizing-writing.”6 This research-led practice is evident in architectural projects such as the National Gallery’s Sainsbury Wing extension in London (1991).

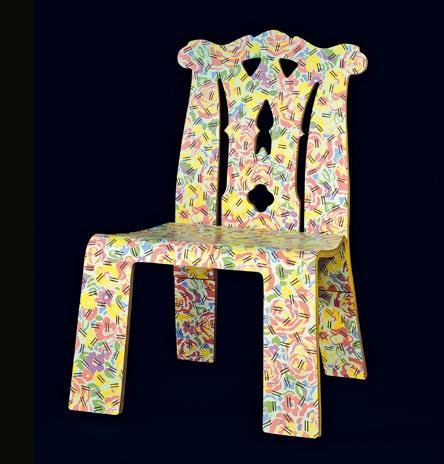

Knoll first asked Scott Brown and Robert Venturi to redesign its Madison Avenue furniture showroom in 1980. Four years later, the business commissioned them to design a furniture collection. The result was a Postmodern comment on the history of the chair, with the Chippendale Chair with Grandmother Pattern being one of five pieces launched in 1984 along with the Queen Anne, Sheraton, Empire, and Art Deco styles.

Inspired by Thomas Chippendale’s British rococo chairbacks, VSB’s chair is a witty historical pastiche yet its reference point is instantly recognizable. Made from plywood with a cut-out detail on the backrest and “ears” either side, it was designed for ease of manufacture and affordability. The surfaces are printed on both sides with a pattern featuring two layered motifs. The floral motif was inspired by an old tablecloth belonging to the grandmother of their colleague, Robert Schwartz, which is overlaid with a series of dashes. Venturi observed, “we wanted a pattern … that was explicitly pretty in its soft, curvy configurations and sweet combinations of colors, and represented as well something with nice associations, those of flowers.”7

Nathan Silver, Ad Hoc chair, 1968

This is the first Ad Hoc chair created by Silver, which was featured on the cover of Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation (1972). The vermillionenameled prototype cost approximately £30 in 1968.

Art

and Utility

Venturi Scott Brown, Chippendale Chair with Grandmother Pattern, 1984

right : The chair was one of five designed by VSB for manufacturers Knoll International. It featured in the 2018 exhibition “Thomas Chippendale, 1718–1779: A Celebration of British Craftsmanship & Design” at Leeds City Museum, England, which marked the tercentenary of Chippendale’s birth and highlighted how his legacy had become part of 20th-century popular culture in Britain and America.

Ron Arad, Little Heavy chair, 1991

opposite left : One of the last chairs produced in Arad’s London workshop, it is number 9 of a limited edition of just 20. Arad works with a variety of metals including tempered steel strips and the woven metal used for industrial conveyor belts.

Gaetano Pesce, Crosby child’s chair, 1998

opposite right : Made from molded and poured polyurethane resin, each chair features a unique color palette and detailing, while the dimensions remain consistent. Individuality and humor are themes of Pesce’s designs.

In the early 1980s, British-Israeli architect Ron Arad set up the One Off design studio with Caroline Thorman. At that time, he experimented with making furniture out of welded tempered steel, which he manipulated, shaped, and crushed into sculptural forms. His first furniture piece was the iconic Rover Chair (1981), which he made with a Rover V8 SL car seat salvaged from a scrapyard. Legend has it that fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier saw the first chairs Arad made and bought them all.

The Little Heavy chair (1991) is part of the “Volume” series in which Arad explored the “illusion” of volume. Designed as an edition piece, it is crafted from highly reflective stainless steel, giving it an overall smooth, organic appearance, yet the traces of the maker remain visible in the rough surfaces of the backrest and seat. These imperfections, created with a rubber hammer, not only reveal the material’s inherent characteristics but also challenge the machine-driven

perfection of Modernism. Cool, unyielding and fixed, the chair blurs the boundaries between furniture and sculpture in the same way that his architectural commissions—such as ToHa1, completed in 2019 as part of an office complex designed in collaboration with Avner Yashar Architects in Tel Aviv—merge into monumental art forms.

Arad’s process of design is collaborative and involves a continual reworking and reconceptualization to push form and materials to their limits. His experimentation with Little Heavy led to a new interpretation designed for mass production and comfort, the Soft Little Heavy (1991–3), which retained the volume and profile of the original but was produced in a soft, upholstered foam.

Described at the time by then New York Times critic Herbert Muschamp as “the architectural equivalent of a brainstorm,” Italian architect Gaetano Pesce’s multidisciplinary work is characterized by a vivid use of color and material, tireless

experimentation, and playfulness. Pesce was part of the Italian Radical Design movement active at the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s. The movement embraced kitsch and historical eclecticism in its rally against Modernism, proposing instead that architects and designers should actively and critically engage in social and political issues through their work. Throughout his life and practice, Pesce upheld these ideals and the belief that architecture should both represent and support the place and community it inhabits, observing: “long gone is the time of mute objects and decorative architecture. Today, they should express the places where they are built on, the identity, culture, geography, and should no longer transport ‘the same’ to different locations.”8 This approach is evident in Pesce’s nine-story residential block, Organic Building (1993), in Osaka, Japan. In its red steel façade, Pesce integrates the precursor to contemporary “living walls” through a system of small bays with built-in

irrigation, which ingeniously support a vertical garden that includes over 80 varieties of plants and trees.

In furniture, Pesce’s humanistic approach is expressed in anthropomorphic and symbolic forms designed to be in dialogue with the user. His most famous piece is the UP5_6 chair (1969), known as “La Mamma,” which invited debate about the objectification and oppression of women. Pesce named his Crosby chair after the location of his studio and produced it in adult and child versions. The seat is the profile of a head, and the piercing in the chair’s backrest evokes a smiling face. Produced with molded and poured polyurethane resin, the candy color palette of each chair is as individual as the user, while the dimensions remain consistent.

The appeal of his work endures. Four hundred of Pesce’s Come Stai? chairs provided an exuberant colorsaturated swirl of seating at couture house Bottega Veneta’s Summer 2023 show in Milan, Italy.

A Shared Design DNA Architects design chairs for various reasons: to furnish their own buildings, to fulfill commissions, from a desire to experiment with form and materials, or to critically engage with contemporary issues in an easier-toachieve form than building. Perhaps it is also the challenge of balancing creativity, structure, and ergonomics in one of the most essential pieces of furniture we own.

This brief survey has shown that their building projects and chair designs share a distinctive design DNA: it would not be difficult to identify who designed each one in a line-up. Chairs designed by architects not only represent a moment in their creative practice; they reflect the culture, society, and technology of their time. 2

Text © 2025 Axiomatic Editions. Images: pp. 14–15 Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections; p. 17 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, photo Pip Barnard; p. 18 © FLC/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2025. Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, photo Peter Kelleher; pp. 19–21 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Notes

1. Huren Marsh, video call with the author, November 29, 2024.

2. See the Chandigarh Chairs project www.chandigarhchairs.com.

3. Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver, Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation, Secker & Warburg (London), 1972.

4. Nathan Silver, email to the author, November 26, 2024.

5. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA), 1972.

6. Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, “Interview with Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi: Is and Ought,” Perspecta 41, 2008, p. 41.

7. VSBA Archives, project statement, July 19, 1990: venturiscottbrown.org.

8. Gaetano Pesce, “No More Silent Objects” exhibition by Salon 94, New York, September 14–October 30, 2021: https://salon94design.com/exhibitions/gaetano-pesce.

Easy Edges in Uneasy Times

Vanessa Grossman

Reflections on Frank Gehry’s Cardboard Furniture Design

Architect Frank Gehry’s cardboard furniture has become iconic in the design world. Vanessa Grossman, Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, discusses the evolution of his “Easy Edges” series in the 1970s, which unlocked the potential of designs made from waste.

The

Frank O. Gehry, Wiggle side chair, “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture series, 1972

Wiggle side chair is one of the most iconic pieces in the “Easy Edges” collection, celebrated for its sculptural form and innovative use of cardboard.

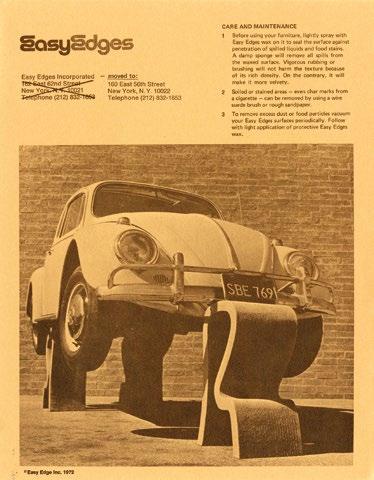

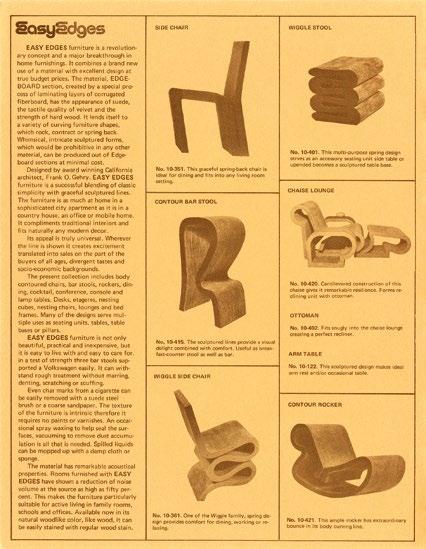

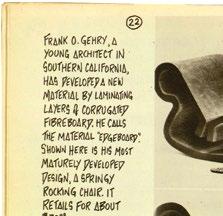

Frank O. Gehry, “Easy Edges” series sales catalog, 1972

right : A “Test of Resistance” with three “Easy Edges” chairs supporting a Volkswagen Beetle, which became the most iconic promotional image for the line, was featured in a 1972 sales catalog for “Easy Edges.”

Frank O. Gehry, “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture series, 1969–73

opposite left : The assembly line of “Easy Edges” pieces in the workshop, with the laminated board edging.

opposite right : The stacked pieces of corrugated cardboard used to make “Easy Edges” furniture in the workshop.

Frank Gehry’s innovative furniture design of the “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture line (1969–73) quickly gained widespread attention. Building on his earlier interior design work, “Easy Edges” featured unconventional materials and playful forms that propelled Gehry to celebrity status in the furniture world— though he did not fully embrace this role. As he puts it, “When I get excited about a material—like cardboard—I try to find out what that material does. I play with it until I get something that is comfortable and that expresses the character of the material. What I’m doing is very personal, exploring a material, seeing where it goes and where it takes me. It’s something that keeps me interested in between projects, like some people play chess.”1 Gehry’s experiments with cardboard were driven not only by the desire for affordability—echoing modern designers’ push to mass-produce and democratize furniture—but also by the rise of ecological thinking in car-centric Los Angeles. As he explains, “When I did the cardboard furniture in 1972, I was trying to make the Volkswagen—a really cheap line of furniture for people. Since then, the fish lamps and the new line of cardboard furniture haven’t been designed with the idea of selling them. I’m simply interested in the materials—the Formica and the cardboard.”2

Above all, “Easy Edges” reflected Gehry’s drive to shape architectural form using non-precious materials that bridge aesthetics and technology. Like many of his early works, the furniture range captured the intersection of the low-tech, utopian culture that emerged in California in the 1960s and the high-tech, research-driven environment that fused art and technology—a

high- and low-tech that continues to define the region today, with Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurs and Gehry’s architecture as landmarks. The patenting of “Easy Edges” eerily mirrored the fleeting rise of today’s startups that develop low-cost technology— an innovation whose potential was cut short, as it diverted attention from Gehry’s true calling as an architect.

In 1983, Gehry’s rising prominence led to his selection as a juror for the Third International Furniture Competition of Progressive Architecture magazine, alongside Kenneth Frampton and Arata Isozaki. Gehry’s reflections on the winning projects, as well as his broader comments about the competition, offer valuable retrospective insights into his “Easy Edges” designs. He remarked, “You must understand that I’m very interested in comfort and tactile qualities,”3 and also mused, “It would be very expensive. Are we being reactionary? I like it.”4 Regarding the role of fantasy in design, he commented during the competition’s general discussion—without pointing to any specific project: “The pieces that had something to do with fantasy were not really strongly brought off as fantasy.”5 Among the awarded furniture designs was a side chair by Michael Graves, with the first prize going to another side chair by Roger Crowley, both crafted from wood veneer. “Easy Edges,” in today’s context, holds potential as a model for the still-elusive circular economy, which seeks to combat climate change. It also resonates with Gehry’s sevendecade legacy of fusing artistry with technology—creating projects that can be “really strongly brought out as fantasy,” even if they do not conform to mass-market ideals, like the Volkswagen Beetle.

The Untapped Potential of Waste and Paper Gehry became acutely aware of waste economy while working for Joseph Magnin, the San Francisco merchant and founder in 1919 of the Joseph Magnin department-store chain. Gehry later explained that he was “disturbed” that half of the construction budget went toward store fixtures that would soon be obsolete due to “changing fashion and retail methods.”6 Gehry’s solution was to use disposable, inexpensive fixtures. He was not alone in his pursuit of creating furniture from locally available—and even discarded—materials. His experience designing shopping malls, interiors, and retail spaces in Los Angeles influenced his focus on using the city’s waste products. In 1970, architect and furniture designer Jim Hull, along with his wife Penny, founded Hull Urban Design Development Laboratory, Etc. (H.U.D.D.L.E.), a Los Angeles-based brand that recycled industrial waste into affordable, experimental furniture. Like Gehry, Jim Hull had worked for Victor Gruen Associates, though Gehry had left before Hull started. They eventually met in the 1970s, when Gehry, no longer running his furniture company, advised Hull on H.U.D.D.L.E.7 Shaped by their experiences working with figures like Gruen and Magnin, both developed a keen awareness of the wastefulness and environmental impact of the retail economy—in particular, of what since the 1990s has come to be called “fast fashion.”

While H.U.D.D.L.E.’s furniture primarily used formed-fiber hardboard—made from fiber by-products of the lumber industry, as well as reconstituted newspapers and cardboard boxes for tubular chairs and sofas upholstered in less environmentally friendly petroleum-based polyurethane foam—Gehry favored the simplicity and ubiquity of cardboard. His breakthrough came from a pile of corrugated cardboard, or “Edgeboard,” that he kept in his office for architectural models. In 1969, when it was

decided that a NASA-sponsored symposium on art and science would be held in the studio of artist Robert Irwin, Irwin enlisted the help of Gehry and artist Larry Bell to transform the space on a shoestring budget. In response, Gehry designed innovative seating made of stacked cardboard.8

Working with artist Josh (Joshua) Young, Gehry embarked on an experimental process to explore the potential of paper, which, in his words, evolved “very scientifically” as they developed “a whole assembly-line technology.”9 Young was a student of Irwin’s at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine), and played a key role in developing the Market Street Program (1970–74) in Venice, California. Frequently listed as a “curator” for the initiative, he also collaborated closely with Gehry, working in his office throughout the 1970s. Their research with paper led to the creation of Edgeboard Sections, a groundbreaking design in which Gehry emphasized the raw, exposed edges of the cardboard rather than its flat surfaces. This approach was inspired by the layered construction of architects’ contour models. He also discovered that stacking single sheets of cardboard exponentially increased their strength. This insight led him to transform the material into sculptural, ribbon-like folded chairs and tables, with hardboard facing applied to the flat surfaces—thick, laminated layers of corrugated cardboard that acquired the strength and solidity of durable material. “Easy Edges” emerged as the most economical and robust design to produce. Gehry’s use of the Volkswagen Beetle was not merely a metaphor for mass production, as he had initially suggested, but rather a more literal—and somewhat sarcastic—gesture.10 By placing a two-thousand-pound Beetle on three of his cardboard chairs, Gehry turned the scene into a striking art installation, which became one of the most iconic advertisements for the design.

Gehry’s and H.U.D.D.L.E.’s designs were featured in the 1973 book Nomadic Furniture 1, subtitled How to Build and Where to Buy Lightweight Furniture that Folds, Inflates, Knocks Down, Stacks, or Is Disposable and Can Be Recycled. 11 Part instruction manual, part catalog, the book was aimed at offering easy-to-move furniture solutions for a nomadic lifestyle. Design theorist Victor Papanek, a strong advocate for socially and environmentally responsible design, co-organized the publication with James Hennessey. Their goal was to create a book that, unlike other DIY projects of the Whole Earth Catalog era, would teach readers how to build furniture suitable for the “nomadic living” of Americans, who are said to move about every two to three years on average, through furniture “that also folds, inflates or knocks down, or else is disposable while being ecologically responsible!”12

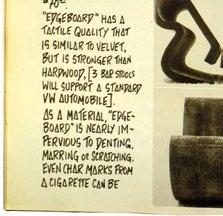

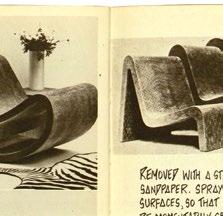

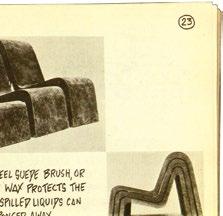

The book also highlighted Gehry’s new-material furniture, describing it as an “excellent example of design made from ‘waste,’”13 emphasizing its low maintenance and acoustic properties. It featured Gehry’s “springy rocking chair,” hailed as his “most maturely developed design.”14 Its tactile quality was described as “similar to velvet, but … stronger than hardwood.”15 The material, Edgeboard, was noted for its resilience: “nearly impervious to denting, marring [sic] or scratching,” with even cigarette char marks easily removed using a steel suede brush or sandpaper.16 Spray wax protected the surface, allowing spilled liquids to be quickly wiped away. Most notably, the material exhibited unique sound-absorbing properties, reducing noise at its source by up to 50 percent.

The remarkable development of so many versatile properties from such a simple material even led mainstream media, like the New York Times, to dispel concerns about its flammability.17 The paper emphasized that cigarettes left burning on the surface would not ignite, as the material could be made flame-retardant with a deterrent spray, applied either during manufacturing or by consumers at home, “at only a small additional cost.”18 The collection, which included 17 patented pieces—such as “bodycontoured chairs,” bar stools, rockers, and dining tables—was introduced in major department stores in New York and Los Angeles. The East Coast newspaper dubbed it “paper furniture for penny pinchers,” noting, “It’s the price that represents a real breakthrough for items of good modern design.”19

A page from the catalog showcases the Side chair, Contour bar stool, Wiggle stools, Chaise Lounge ottoman, Wiggle side chair, and Body Contour rocker—celebrated as a revolutionary concept and a groundbreaking advancement in home furnishings.

Frank O. Gehry, “Easy Edges” series sales catalog, 1972

Frank O. Gehry, “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture series, 1969–73

“A springy rocking chair” featured in James Hennessey and Victor Papanek’s Nomadic Furniture 1 (1973), a book that highlighted the durability and sound-absorbing qualities of “Edgeboard,” the innovative, velvety material developed by Gehry.

Frank O. Gehry, Study sketch for a lounge chair for the “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture series, c . 1969–72

The drawing, rendered in graphite on tracing paper, reflects the design language of the bentwood furniture pioneered in the mid-19th century by the German-Austrian pioneer in the industrialization of furniture manufacture, Michael Thonet.

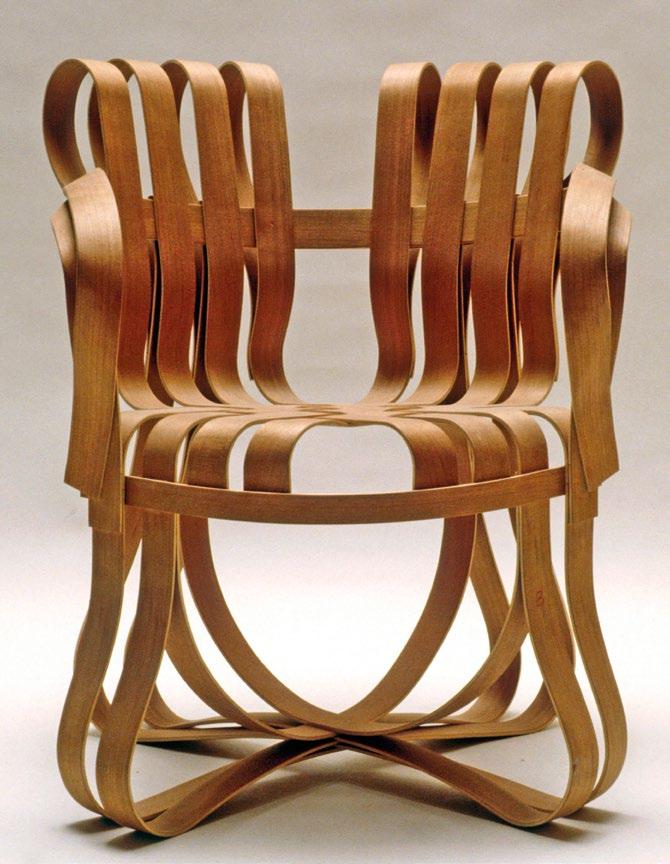

Frank O. Gehry, Cross Check chair, bentwood furniture series for Knoll, 1992

below : Manufactured by Knoll since 1992, this chair is crafted from continuous wood strips, with no upholstery or traditional chair frame, showcasing a sleek, minimalist design.

Frank O. Gehry, Body Contour rocker, “Easy Edges” cardboard furniture series, 1969–73

opposite : The rocker boasts a distinctive profile, shaped by a single layer of laminated fiberboard.

While the 20th-century Finnish architect Alvar Aalto’s influence on Gehry’s “Easy Edges” designs has been noted,20 the virtuosity, sleekness, and sculptural curves of certain pieces also recall the mid-19th-century pioneering bentwood designs of the German-Austrian cabinetmaker Michael Thonet. This connection extends to Gehry’s later work, such as his 1992 series of bentwood furniture for Knoll, including the Cross Check chair designed in 1990. As early as 1972, the New York Museum of Modern Art added the “Easy Edges” Body Contour rocker (1971) to its design study collection.21 However, by 1973, what had begun as a way to fill time between architectural projects was at risk of becoming a full-time pursuit—a direction Gehry ultimately chose to abandon. Production ceased after the initial run, and since 1986, Vitra has reissued four models from the “Easy Edges” collection, transforming them from affordable, household furniture into high-priced couture pieces—far removed from their original reference to the Volkswagen “people’s car.”

Outside the Global North, the parallel economies of a city like São Paulo are defined by the work of catadores de papel—cardboard pickers who work independently or within cooperatives, earning a living by collecting and selling cardboard and other recyclables. From these alternative labor networks, remarkable grassroots social initiatives have emerged, such as Dulcinéia Catadora, a project born from a collaboration between the catadores and artists like Lúcia Rosa at the 27th São Paulo Art Biennial in 2006. Dulcinéia Catadora operates as a recycling collective in São Paulo, where members develop inclusive editorial projects featuring authors working outside the commercial publishing circuit, with research-based works of art, poetry, and storytelling. On the design front, Brazilian brothers Humberto and Fernando Campana were inspired by the work of the catadores to create their “Papelão” collection (1993), which includes sofas, chairs, and coffee tables. These designs, however, also echo Gehry’s “Easy Edges” in their use of cardboard. While the Campanas have often framed their work as a social critique of Brazilian poverty, they have faced criticism for aestheticizing and commodifying22 what Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi called “design at the impasse”23—everyday objects crafted from scarcity. Though this may be seen as “reactionary,” as Gehry suggested in 1983, the Campanas’ luxury furniture reflects a trajectory like Gehry’s own shift from affordable, experimental cardboard designs to high-end pieces produced by Vitra. In both cases, this evolution illustrates the inevitable fate of “good design.”

Fantastic Visions for Ecological Imagination

In the context of today’s environmental crises—exacerbated by the toxicity of fast fashion and the waste generated by Amazon’s packaging—it is timely to revisit Gehry’s “Easy Edges,” a groundbreaking exploration from the late 1960s that playfully reimagined the untapped potential of waste and paper. While shopping centers are reportedly “making a comeback,”24 defying even pre-Covid-19-pandemic predictions of a retail apocalypse, the true crisis may lie elsewhere. Consider fast fashion: despite an overabundance of clothing “sufficient to outfit the next six generations,” production in the Global North continues to surge, flooding countries like Ghana with discarded garments— primarily from the UK, US, and China, as highlighted in a disturbing 2024 report.25 These textiles, often dumped into the ocean, harm marine life and ecosystems. As concerns grow over the export and dumping of recyclables, there is increasing support for phasing out non-recyclable products, and designing for reuse. Today, the waste generated by students’ 3D-printed models produces harmful emissions and ultimately ends up in the trash, despite students being taught critical perspectives on sustainability in the age of the Anthropocene. In these uneasy times, Gehry’s original concept for “Easy Edges”—despite the challenges it faced in the commodity market—feels more relevant than ever. It offers a vision of how (environmental) imagination might be “strongly brought off as fantasy,” providing an edge over mainstream architectural theory and practice.2

Notes

1. Frank Gehry in “Furniture: Seven Leading Architects Talk About What Works, What Doesn’t— and Why,” Architectural Digest, August (no. 8), 1988, p. 58.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., p. 176.

4. Ibid., p. 171.

5. Ibid., p. 180.

6. Cited in Jean-Louis Cohen, Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Volume One, 1954–1978, Cahiers d’Art (Paris), 2020, p. 252.

7. Jim Hull, interview with the author in Malibu, Los Angeles, January 5, 2010.

8. See “Interview with Robert Irwin about the First National Symposium on Habitability of Environments,” Weisman Art Museum, October 1, 2018: https://wam.umn.edu/interview-robertirwin-about-first-national-symposium-habitability-environments.

9. Robert Irwin, quoted in Joseph Giovanni, “Edges, Easy and Experimental,” in Rosemarie Haag Bletter (ed.), The Architecture of Frank Gehry, Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN), 1986, p. 67, cited in Cohen, Frank Gehry, p. 255.

10. See Francesco Dal Co, “The World Turned Upside-Down: The Tortoise Flies and the Hare Threatens the Lion,” in Francesco Dal Co and Kurt W. Forster, Frank O. Gehry: The Complete Works, Monacelli Press (New York), 1998, p. 47.

11. James Hennessey and Victor Papanek, Nomadic Furniture 1, Pantheon Books (New York), 1973, pp. 20–23 and 46.

12. Ibid., p. 2.

13. Ibid., p. 46.

14. Ibid., p. 22.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Norma Skurka, “Paper Furniture for Penny Pinchers,” The New York Times, April 9, 1972.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Francesco Dal Co in Dal Co and Forster, Frank O. Gehry: The Complete Works, p. 60, n. 30.

21. “Cardboard is for Jumping,” Life, July 14, 1972.

22. See Adriana Kertzer, Favelization: The Imaginary Brazil in Contemporary Film, Fashion, and Design, DesignFile (New York), 2014.

23. See Lina Bo Bardi, Tempos de grossura: o design no impasse, Instituto Lina Bo e Pietro Maria Bardi (São Paulo), 1994.

24. Joe Gose, “What Retail Apocalypse? Shopping Centers Are Making a Comeback,” The New York Times, June 9, 2024.

25. Fleur Britten, “Where Does The UK’s Fast Fashion End Up? I Found Out on a Beach Clean in Ghana,” The Guardian, September 24, 2024.

Johan Deurell

Fragments of The Role of Design in Zaha

Architecture

Hadid’s Early Practice

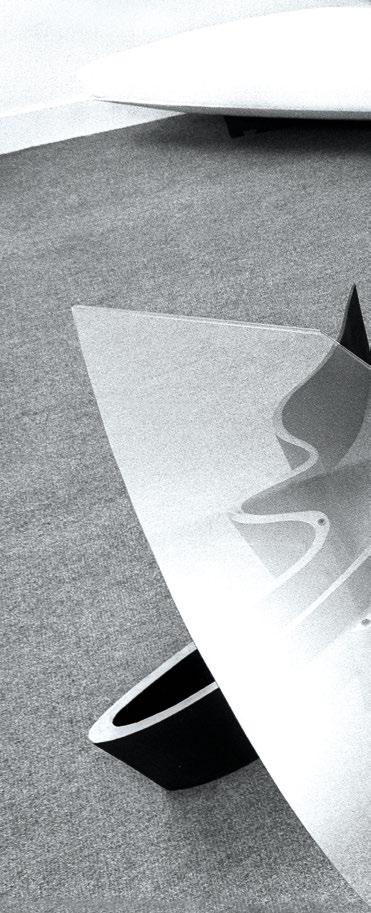

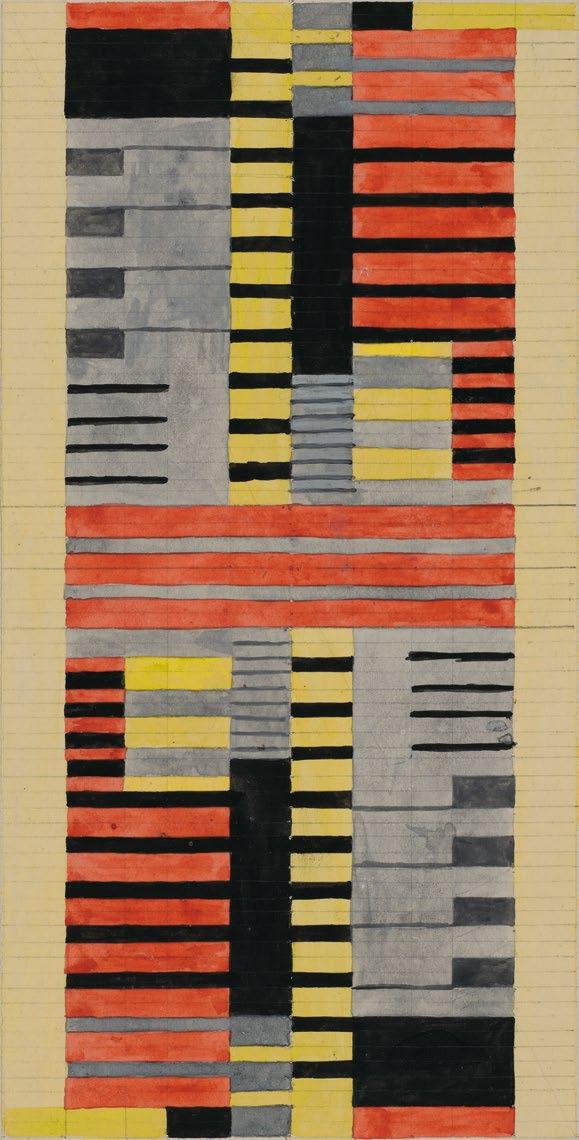

Zaha Hadid Architects, Hommage à Verner Panton, 1990

In 1989, Zaha Hadid was commissioned by the Vitra furniture company to make a painting paying tribute to Danish designer Verner Panton’s cantilevered chair. Hadid was a fan of the classic Panton Chair and would furnish her office and home with it.

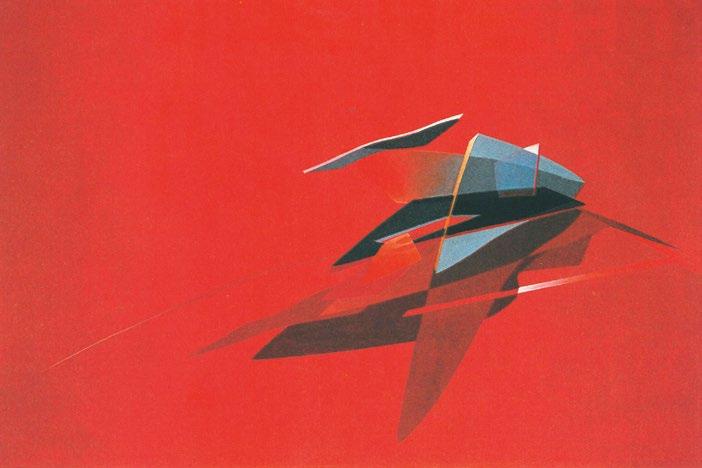

When Zaha Hadid set up her London office in the early 1980s, it was mostly sustained by furniture and small interior design commissions. These projects were embryonic but highly influential in Hadid’s continuing trajectory to architectural superstardom, and were important testbeds for her early nascent talent. Curator and writer Johan Deurell describes these heady days, the ethos of the office, its clients, and the furniture it designed.

The satisfaction of design is that the production process between idea and result is so quick and uncomplicated compared to a building. In terms of form, though, design and architecture interest me equally—there is a useful dialogue between the two. You might say that design objects are fragments of what could occur in architecture.

— Zaha Hadid, 20061

After finishing her diploma at London’s Architectural Association (AA) and spending a year as a partner of Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Hadid set up her own architectural office in 1979. From then until the completion of her first building—the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, Germany—in 1993, Hadid used interior commissions to experiment with space and think about furniture in relation to buildings. Much like the practice’s early architectural projects, interiors and furniture were frequently exhibited and publicized. In fact, they represent the first time the world experienced how Hadid’s Suprematist-inspired architecture could be transformed into something tangible and useable.

Three design projects chart the development of Hadid’s practice during the 1980s and the role of furniture and interiors: 59 Eaton Place

(1981–2), 24 Cathcart Road (1985–7), and Edra (1987–8). What were the design methods used to deliver the projects? How did these collaborations come about? In what ways did interiors and furniture contribute to Zaha Hadid Architects’ reputation?

Explosions and Dynamism

Zaha Hadid’s office initially worked between her home and the AA, where she taught, and from 1985 in a studio in a 19th-century former school building in London’s Clerkenwell district. It operated almost like an atelier, with a handful of Hadid’s former students and other young, aspiring architects working under her direction. She made no rigid distinction between architecture, interiors, furniture, and product design, and often the same people worked across disciplines. For example, Hadid’s architectural paintings had multiple authors.

During her student years, Hadid was introduced to the early 20thcentury Soviet avant-garde, notably Kazimir Malevich; his work would inform her ideas on abstraction. Influenced by OMA, she started using abstract painting as a design strategy for architecture, as much for concept development as a presentation tactic. Many of the early paintings were conceived as exploded views with hovering fragments, offering multiple

perspectives and viewpoints. The different elements in the paintings relate to an assortment of sketches, technical drawings, existing sitemaps, photography, and other material. Former collaborators have described how they would sit around a table late into the night painting together, and the idiosyncratic language Hadid used to describe her techniques: “whooshing” for gradation and “beams” for slabs.

For the interior commission of her brother’s home at 59 Eaton Place in London’s Belgravia district, Hadid developed a concept inspired by an explosion at the nearby Italian consulate. Her paintings show architectural elements, supportive structures, and furniture, all scattered across space in exploded views. She recalled: “My brother wanted something really quite extraordinary. He wanted something new. He wanted to have an unconventional house.”2 This 19th-century townhouse had been renovated and extended in the 1960s and divided into apartments, of which her brother’s occupied three floors. The perspective drawings, aerial views, and floor plans show how she intended to divide the space into two zones: one for entertaining (with a cloakroom, kitchen, dining and living room), and one for living (where six rooms were turned into three bedrooms). By removing internal

walls and inserting columns that doubled as light fixtures, Hadid sought to obtain flexibility and dynamism through mobile partitions, warped bookshelves, oblique canopies, and walls that seamlessly curved into floors. She said: “In the end every object in that house was seen as a piece of architecture. The inside of the house, the terrain, was seen as a landscape. The objects were designed as if they were buildings.”3

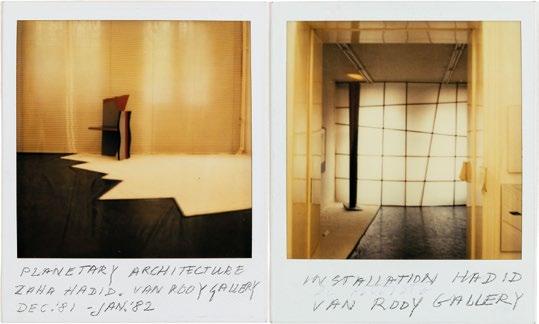

Although this interior was never completed, it gained critical attention as her paintings were exhibited in architectural galleries. Hadid’s exhibition “Planetary Architecture” opened at Amsterdam’s Van Rooy Gallery in November 1981, and featured student work and 59 Eaton Place. Her first known furniture design was also shown here: a chair constructed out of three different irregular wedges in painted wood (backrest/leg, armrest/leg, and seat), coming together in an inverted explosion. A year later, when critic Kenneth Frampton reviewed the second iteration of the exhibition at the AA’s gallery, he described the furniture as “neo-Futurist chairs which jump off the floor like Boccioni’s fist.”4 For Frampton, the chairs were part of the same universe as Hadid’s architecture, namely, an exploration of spatial fluidity and dynamism.

Zaha Hadid Architects, “Planetary Architecture I” exhibition, Van Rooy Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981-2

For her first solo presentation at the Van Rooy Gallery in Amsterdam, Hadid presented her first known furniture design, an “exploded” chair.

Zaha Hadid Architects, 59 Eaton Place, aerial perspective of master bedroom and library, 1981-2

This interior painting disrupts conventional architectural representations by playing with perspective, showing furniture and structural elements in an “exploded view.” The overall scheme won 2’s gold medal in 1982.

Interior as Landscape

In 1985, Hadid worked on several interior concepts in London, such as broadcasting studio Harlech Television (HTV and private residences Melbury Court and Halkin Place. Through the addition of penthouses, the opening up of floor plans, and introduction of mechanized partition walls and oblique canopies to these 19th- and early 20thcentury structures, her team sought to create landscapes furnished with sofas in irregular shapes, glass and steel tables, rotating beds, and boomeranglike recliners. The furniture shares qualities with mid-century pieces by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and the Danish designer Verner Panton, and would not look out of place in the Jetson family’s living room. In its eclecticism and historicism, including its references to the Soviet avant-garde, the furniture relates to Postmodern design strategies proliferating at the time. Although these interior commissions were never realized, they can be seen as speculative research projects. The archive at the Zaha Hadid Foundation includes drawings that map London interiors, connecting disparate projects to each other and the city at large. The paintings and technical drawings for Halkin Place, for example, present interiors and furniture as forms of

urban intervention. Arguably, this kind of critical engagement allowed Hadid to formulate links between architecture and design. Tellingly, a few years later, technical drawings for an art and media center at Zollhof 3 in Düsseldorf, Germany (1989–93), an unrealized major urban project, featured furniture originally created for 24 Cathcart Road in London’s Kensington district.

The 24 Cathcart Road commission came from timber heir William Bitar, and the brief was simple: white furniture and no timber surfaces.5

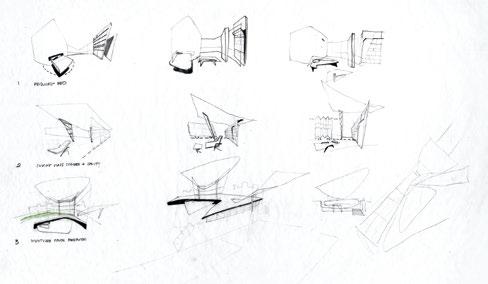

Conceptually, the furniture engaged with ideas of flexibility (the pieces were multifunctional) and dynamism (either by design or construction), and turned the client’s generic 1960s apartment into a site of architectural innovation. Hadid said, “the furniture developed out of the idea of creating an environment.”6 For this project, sketches and model-making, instead of Hadid’s Suprematist-styled paintings, were the chief methods for achieving the dynamic shapes. Michael Wolfson, one of the key architects in the early office, designed and developed many of the pieces. A briefing could be a drawing on a Post-it or notepad. For example, the bronze base of the Sperm Table derived from a quick squiggle by Hadid.

Zaha Hadid Architects, Halkin Place, rotations of interior design sketches, 1985

Hadid’s sketches of Halkin Place use a repertoire of warped walls, oblique canopies, and rotating or boomerangshaped furniture. These design concepts reoccurred across interiors, furniture, and architectural projects in the 1980s.

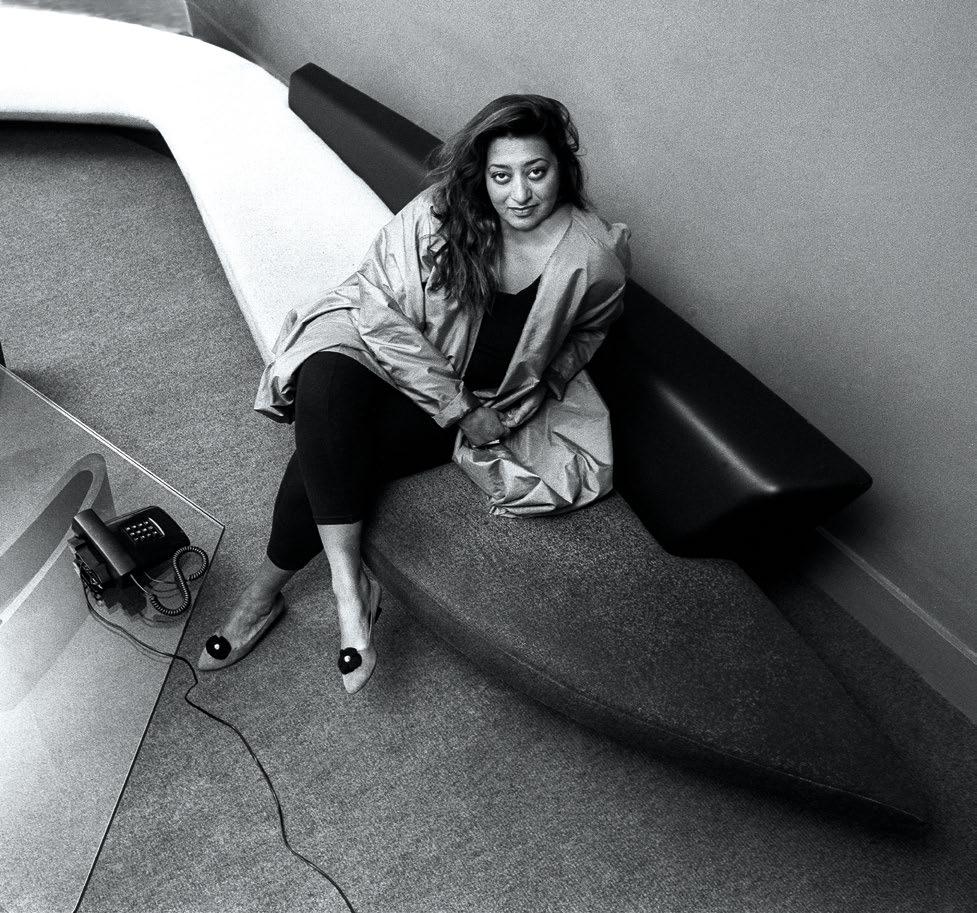

This portrait shows Hadid with her furniture designs, the Whoosh sofa and Sperm table. During this time, fashion and lifestyle magazines became increasingly drawn to her star qualities, making her the ideal architect to feature.

Portrait of Zaha Hadid in Studio 9, 10 Bowling Green Lane, London, England, 1985

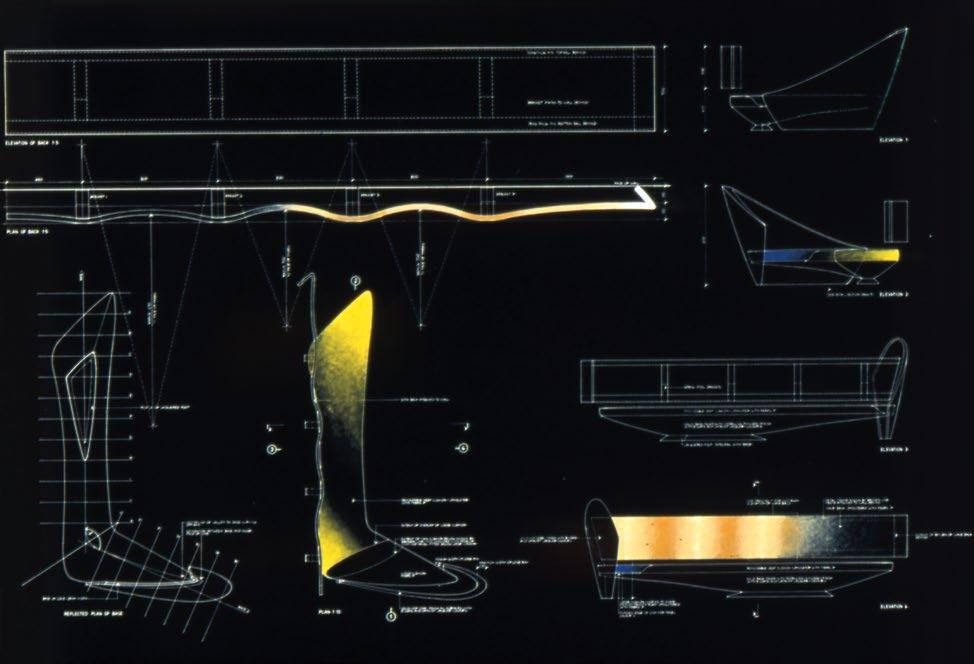

Technical

Zaha Hadid Architects, 24 Cathcart Road interior, London, England, 1986

The 24 Cathcart Road furniture was featured in Casa Vogue, where the Edra team spotted them and initiated a commercial furniture line with Hadid.

Zaha Hadid Architects, 24 Cathcart Road (Interior), Wavy-back sofa, 1986-7

drawings of the 24 Cathcart Road furniture were reverse printed and painted on, which turned them into artworks. These were exhibited in Hadid’s furniture exhibition at the Architectural Association’s members’ room, London, in 1988.

As with her unrealized London interiors, Hadid treated these furniture designs as part of an architectural landscape of movement. The Wavyback sofa wraps around a corner of the room, with its separate backrest attached directly to the wall, implying an exploded view. The boomerangshaped Whoosh sofa with its oblong “beam” backrest has a seat covered in a fabric spray-painted in a grayscale gradation to suggest speed. Other pieces physically moved. The storage unit, which was also a partition wall, was set on an oblique with elements that open and slide. The Metal Carpet coffee table rotated around its own orbit. Allegedly, the more complex furniture required the input of structural engineer Peter Rice at Arup,7 who was a mentor to Hadid during those early years. In 1986, when the furniture was in situ, 24 Cathcart Road became Zaha Hadid Architects’ first completed project. Within a year, however, the client returned the furniture in exchange for a couple of paintings. The sofas and coffee tables ended up in Hadid’s own living room: “His mother didn’t like the furniture, so I said, ‘fine, I’ll take it back.’”8

Furniture as Commercial Strategy

Before the furniture was returned, Hadid commissioned photographer Richard Bryant to document the project, and his images appeared in magazines such as Casa Vogue, Blueprint, and Architectural Record Invariably, the articles described the furniture as Suprematist, dynamic, gravity-defying, and architectural. At this stage, Hadid’s interest in abstraction was just as much a design method as a marketing asset. And the publicity campaign paid off. In late 1987, the director of the newly established Italian furniture company Edra, Valerio Mazzei, and creative director Massimo Morozzi, who had co-founded Archizoom in the late 1960s, spotted the Cathcart Road interior in a magazine. Mazzei recalls: “[We] were fascinated by the harmony of the volumes and the dynamism of the furniture in its relationship with space.”9

After meeting with Hadid in London, Edra developed the Whoosh and Wavy-back sofas and the Metal Carpet table for commercial release, and added a new, smaller cantilevered sofa called Projection. The latter’s

constructivist design of three slabs coming together, supported on a zigzag base, was conceived by Hadid through sketches and models. While the design of the original Whoosh and Wavy-back remained the same, the construction had to change. Padding was introduced to increase seating comfort, and medium-density fiberboard (MDF) bases were changed to solid wood for quality purposes. At a time pre-dating computernumerically controlled (CNC) milling, curvilinearity was achieved using molded wood, plywood, and fiberglass, by a model maker who had previously worked for motorcycle company Piaggio. Leonardo Volpi, research and development manager at Edra, says: “We tried to reproduce them as faithfully as possible, because any curve created by Zaha was not up for interpretation.”10

Zaha Hadid Architects, Projection sofa model for Edra, 1987-8

Hadid’s team made small furniture models in cardboard and wireframe for the 24 Cathcart Road and Edra projects to experiment with shapes and functions.

created a

In September 1988, the collection launched at the Salone del Mobile, the annual international furniture trade fair in Milan, Italy. For the occasion, Edra published a handout featuring Hadid’s much-publicized competition win for a leisure club in Hong Kong, The Peak (1983), as well as her signature-style paintings of the red Projection sofa. To the launch party (which kept going to 4 AM), she wore a custom jacket embellished with beaded capital letters spelling out ‘Zaha Hadid’. She also made a name for herself in the international press: the furniture was featured in several articles, which talked as much about their design merits as her persona. A typical example comes from Interior Design’s recollection of the launch party: “That evening, with her black hair flowing like her loose vowels, and with a cigarette dancing on her lips, the 39-year-old designer gazed regally over the heads of her harem of design groupies.”11 Hadid recuperated this exoticizing narrative and performed to a Western audience. In a sense, she and her designs were the whole ticket.

Dialogues Between Design and Architecture

When the Edra line launched, journalist Cristina Morozzi suggested in the company’s brochure that Zaha Hadid’s universal vision for architecture led her to think about interiors as means to “solve space,” and furniture helped her do so.12 Indeed, Hadid inserted her own furniture designs and those of Verner Panton into her technical drawings for architectural projects, as well as her physical office. Incidentally, for a celebration of Panton’s cantilevered chair at Cologne’s furniture fair, the Swiss furniture company Vitra commissioned Hadid to make the painting Hommage à Verner Panton (1990). Abstracted into a rotational drawing in her signature style, the chair painting was exhibited, and reproduced in advertising material and on beer bottles. Rolf Fehlbaum, then chairman of the company, also asked her to design a chair for them. However, this proved too complicated, so they commissioned Hadid’s first building instead, the Vitra Fire Station.

Furniture and interior designs intersected with Zaha Hadid’s

architectural projects from the beginning. The same design strategies were used, the same people worked on them, and the same ideas were applied across the two. Interiors and furniture design helped Hadid formulate an architectural vision for living in the 21st-century city and made her famous outside architecture circuits. 2

Notes

1. Kenny Schachter, “Celebrating Zaha: The Late Architect’s Interview from Pin-Up’s Debut Issue,” Pin-Up 1, 2006: www.pinupmagazine.org/articles/zaha-hadid-interview.

2. Alvin Boyarsky, “Post-Peak Conversations with Zaha Hadid: 1983 and 1986,” in Yukio Futagawa (ed.), GA Architect 5: Zaha M. Hadid, A.D.A. EDITA (Tokyo), 1986, reprinted 1990, p. 13.

3. Ibid.

4. Kenneth Frampton, “A Kufic Suprematist: The World Culture of Zaha Hadid. Planetary Architecture II,” AA Files

6, May 1984, p. 101.

5. “Deconstructed Kensington,” The Sunday Times Magazine: House Style, Autumn 1988, pp. 46–50.

6. “Alvin Boyarsky Talks with Zaha Hadid” (October and December 1987), in Joseph Giovannini et al., Zaha Hadid, Guggenheim Museum Publications (New York), 2006, p. 48.

7. Deborah Dietsch, “Furniture by Zaha Hadid,” AA Files 17, Spring 1989, p. 76.

8. “Alvin Boyarsky Talks with Zaha Hadid,” p. 50.

9. Gloria Mattioni, “Zaha Hadid,” Edra Magazine, October 2023: www.edra.com/en/art/223406/Zaha-Hadid.

10. Leonardo Volpi, video call with Francesco Fiammenghi, October 23, 2024.

11. Jonathan Turner, “Royal Flush: Zaha Hadid,” Interior Design 17, 1989, p. 74.

12. Cristina Morozzi, Zaha Hadid in Milano Settembre 1988, Edra marketing material (Pisa).

Zaha Hadid Architects, Edra Furniture, Projection sofa, 1988

Zaha Hadid Architects

signature-style architectural painting for the launch of the Edra collection. Here, several abstract components come together in a piece of furniture.

Zaha Hadid Architects, Edra furniture collection, MAXXI—the National Museum of 21st Century Art, Rome, Italy, 2022

The Edra collection consisted of the Whoosh and Wavy-back sofas, and the Metal Carpet coffee table, all created for 24 Cathcart Road, as well as the newly designed Suprematiststyle Projection sofa. The line was produced between 1988 and 1993. Here, the collection is photographed inside one of Zaha Hadid’s most important architectural projects, MAXXI (2009).

© 2025

Text

Axiomatic Editions. Images: pp. 30–1, 33(b), 34(l), 36(t), 37, 38 ©

Zaha Hadid Foundation; p. 33(t) © Drawing Matter Collections; pp. 34–5 © Christopher Pillitz; p. 36(b) © Richard Bryant/ Arcaid.co.uk; p. 39 Photo Alessandro Moggi

Form Follows …

Coates

Nigel Coates UNPACKS HIS Furniture Oeuvre

Nigel Coates, Gallo collection, Poltronova, Firenze, Italy, 1989

The Gallo armchair was inspired by the wings of a cockerel, the sofa stretched a single wing into an upholstered back, and the console has a carved and curved bow supporting a glass top and a single sculpted leg. They are still in production today.

Nigel

If there is one overriding word that describes the buildings and product design of architect Nigel Coates, it is “playful.” His work is imaginatively eclectic, combining many tropes from the history of art and design in his own inimitable way to create objects of desire. Here he describes his personal creative journey in respect to his furniture and the myriad inspirations that inform it.

In London in the early 1980s, during the fallout from punk, my work developed a rough spontaneity and often included fragments retrieved from old buildings. The future was on hold as my students at the Architectural Association and I reinvented the here-and-now as a salvage operation. By 1985, I had realized my first interior project in Japan, the Metropole restaurant, for which I had been commissioned to design the furniture. I was following in the footsteps of my Italian heroes—those architects who had opted not only to build, but to think and make, especially furniture.