PETER NEILSON

Two Exhibitions Together

Paintings and drawings . . . plus sculpture

18 November - 6 December 2025

Two Exhibitions Together

Paintings and drawings . . . plus sculpture

18 November - 6 December 2025

Two Exhibitions Together

Paintings

Opening Night

Tuesday 18 November 2025 6pm – 8pm

28 & 35 Derby Street Collingwood VIC 3066

Exhibition Dates

Tuesday 18 November – Saturday 6 December 2025

Open 7 days 10am – 6pm

T 03 9417 4303

melbourne@australiangalleries.com.au australiangalleries.com.au

Andrew Benjamin

Honorary Professor in the School of Communication and Cultural Studies in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne

There are two aspects of this extraordinary exhibition that demand to be addressed. The first is the actual specificity of the works, of the two large paintings - Rough Justice (just as we promised) and Going Home (a long time overdue) as well as the smaller paintings and drawings that are related to the larger works. The second, which is much more demanding, concerns the relation between all the works. To configure the second one as a question: what is the nature of the relation of these small works to the larger paintings?

In a sense this second question dominates precisely because any attempt to answer it necessitates addressing the particular nature of Peter Neilson’s project as a painter. Not only are there drawings that relate to the larger works, there are also smaller paintings that equally have a relation. Often in writing about paintings it is essential to concentrate on a detail and thus to pick a particular moment, such moments are often thought either to capture a work’s essential quality, or, at the very least, to present a fundamental or defining aspect of it. Here, however, something different is at work. Neilson has already staged a form of relation by surrounding the larger works with what can be called provisionally, details. And yet, even accepting this term for a moment, these details are not excisions. They are not parts of a whole. The visual connection is obvious and yet at the same time as there is a connection there is equally a disconnect. In certain instances the drawings contain a recognisable character who, while appearing in the larger works, the drawings provide them with a different place and a different setting. In Exiting Stage Left not only is there a shift in medium - from painting to drawing - there is a repositioning of one who, for viewers of Neilson’s work, has a singular familiarity. To the extent that attention is given these elements of the larger whole (a whole in this context being no more than the exhibition) what continues to be noticed is the way in which both physical displacements occur and temporal disjunctions are introduced. Narrative time therefore is allowed its own irregularities. In addition, shifts in medium continue to be staged. Taken as a whole there is the presence of a form of continuity in which surety and unsurety work together. What is both undone and asserted is the idea of a complete work of art.

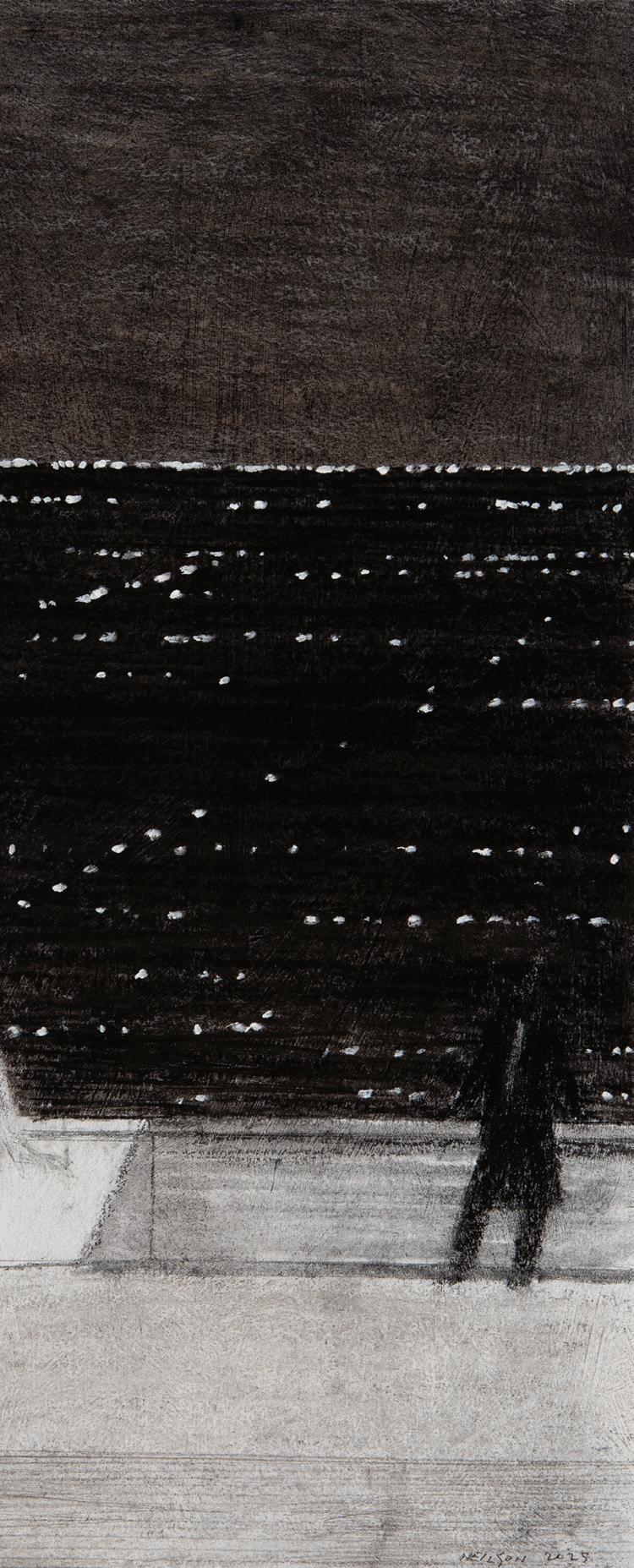

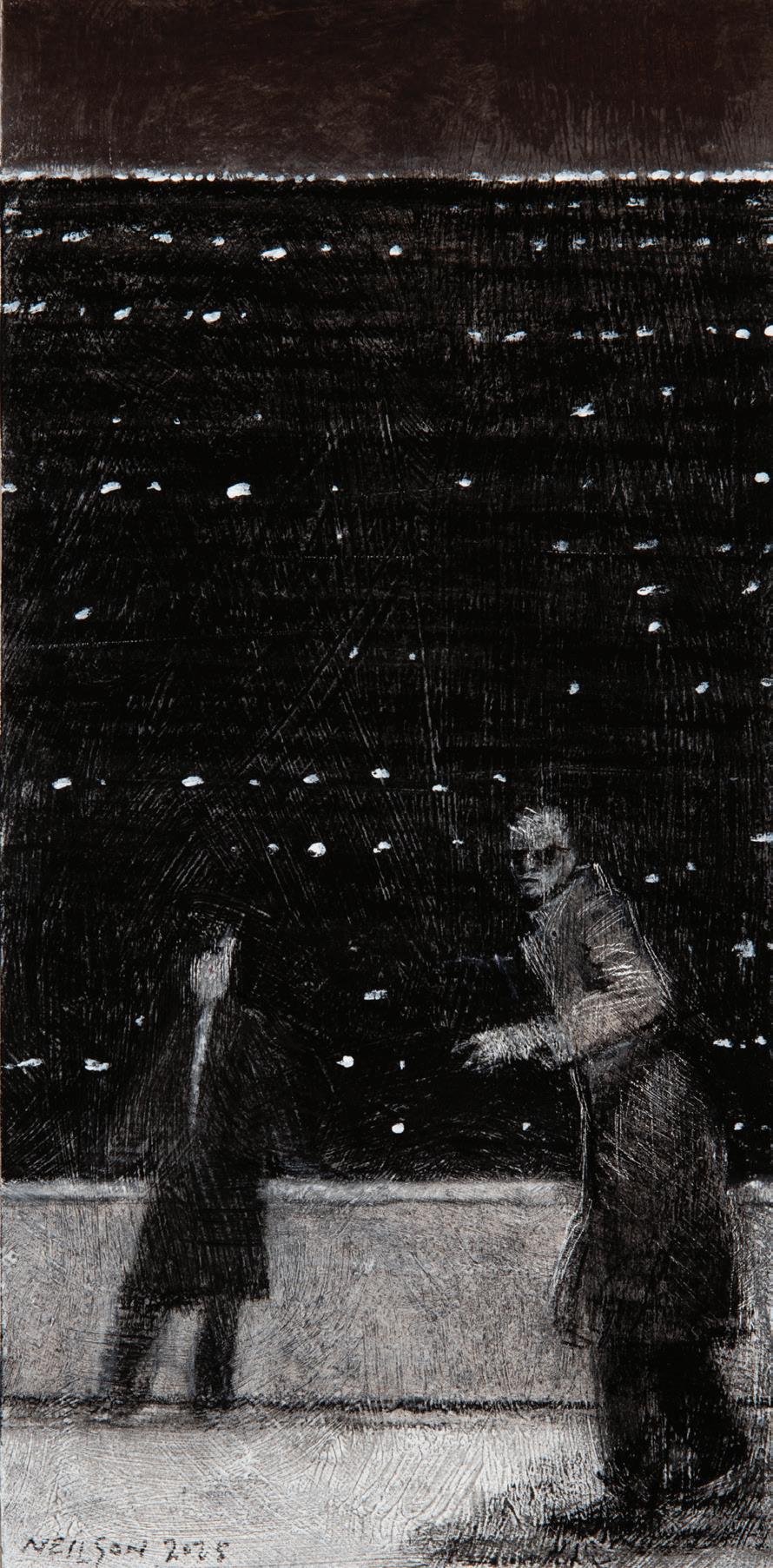

In both of the large paintings works there are horizons. It is night. From within the frame of Rough Justice (just as we promised) a female figure looks out. Occupying a similar setting in Going Home (a long time overdue) a coated figure moves towards the night. Both are positioned at what conventionally might be understood as the work’s centre. As the figure is held by a relation to the horizon, established as a result are connections to the history of painting. In being evoked they are also displaced. Moreover, to the extent that these figures are defined by these scenes then they equally, and simultaneously, resist any automatic incorporation into

that which defines them. There is a reference to the cityscape. In addition, there might be an allusion to landscape. And yet, these generic determinations are undone – displaced - the moment they are announced. There are no longer details, were they to be assimilated to a part/whole relation. What endures therefore are scenes. Nielson is a painter of scenes. It is at this precise point that works of these works becomes fundamental.

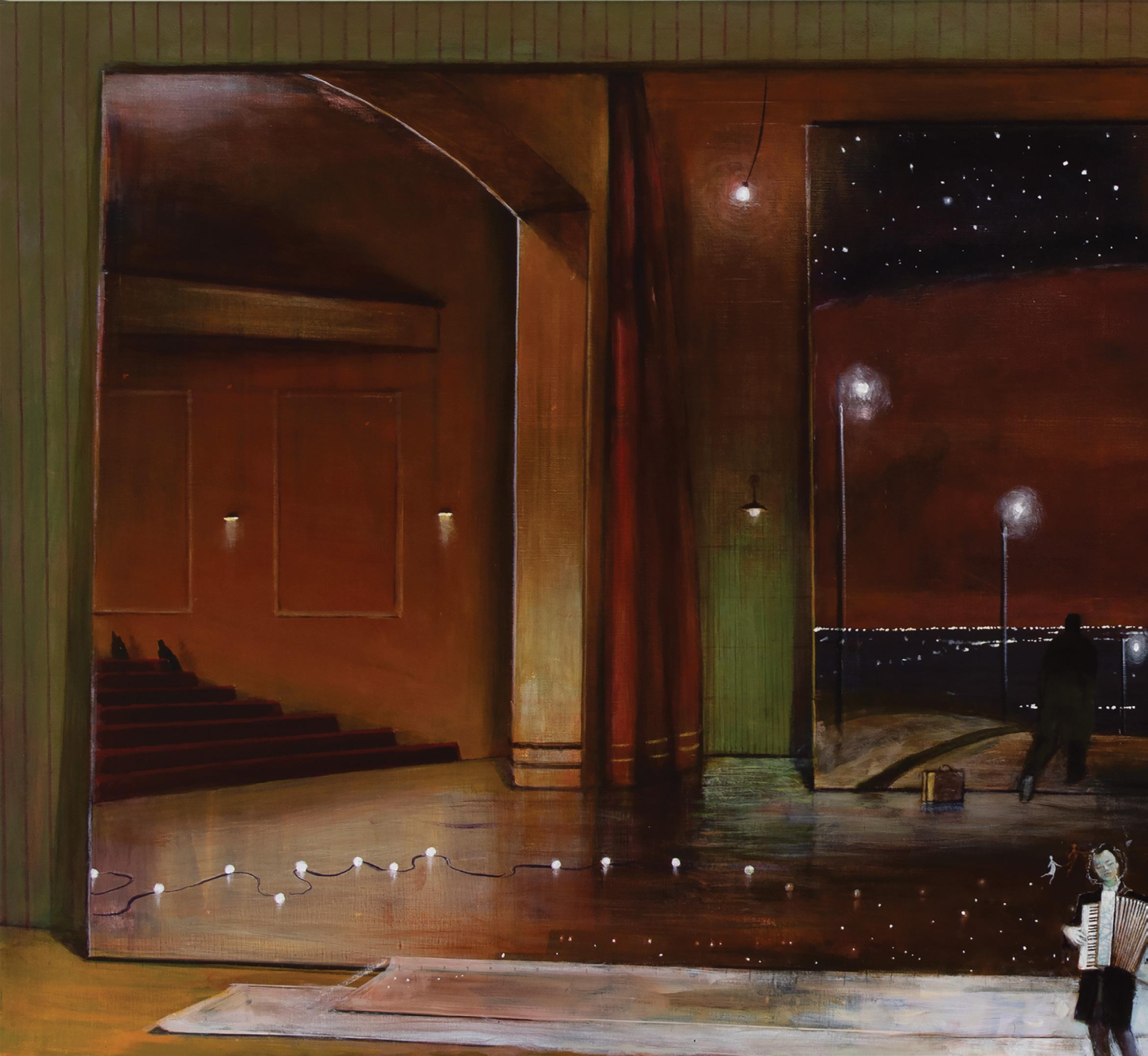

The identification of these larger paintings with the presentation of scenes - and it is essential to insist on the plural scenes - is not a claim this is applicable to the genre of painting as a whole. The particularity of Neilson’s scenes needs to be maintained. Hence, the displacing effect of these works. If the use of perspective within the history of figurative painting can be interpreted as the continual attempt to eliminate the possibility that a work of art devolve into scenes, where those scenes pose the question of how they are to be related, then Neilson’s work provides another form of narrative coherence. It demands of the viewer that they create the scene. However, what is demanded is an act of creation that contains openings and fissures and thus allows questions to endure. The act of creation of course - the creation resulting from the work of scenes - is already inscribed into the structure of both of the larger paintings. The presence of a stage in Going Home (a long time overdue) is given by the presence of an accordion player. She stands outside a frame that is itself perched on a table and which contains a frame into which a figure walks. The figure walks towards the night. The night, within the painting’s own work, is itself a framing device precisely as a result of the presence of lights on the horizon (thus creating the horizon). There is a multitude of scenes. Within each one activity is occurring. It is due to the presence of differing modes of activity that the question of the relation between scenes becomes insistent. That insistence gives rise to a straightforward question: If coherence no longer resides in that which is given as complete, then how is coherence to be understood?

Again, in Going Home (a long time overdue) a figure moves from one frame to another. To the work’s left other figures move up stairs; the stairs of a theatre. They are leaving. There is a stage behind them. To the right within another canvas, another frame, shadows are cast as figures move. In regards to the these figures it is no longer a choice between anonymity and collectivity. There is a gesture towards something else. Another quality of both presence and agency continues within each frame and thus, in complex ways, more broadly, in the work as a whole. The combined presence of these scenes - and a proliferation of scenes yielding the question of their own coherence is also at work in Rough Justice (just as we promised) - incorporated within a proliferation of frames continues to yield the question of narrative coherence. The work, as its work presents the question and refuses a response. This is not the generation of an incoherent narrative. Rather, that particular proliferation is itself the recognition that a narrative can only ever be given coherence within a frame of reference that is itself sustained by a specific ethical or political choice. In the refusal by both of these larger paintings to resolve, the work of painting is then at its most political and at its most ethical. The works attain this position, namely, the link to both the ethical and the political that occurs, not because of literal content, but in the way its presentation takes place. What is staged is the unavoidability of the decision. The demand for coherence, and thus the provision of that which informs it, necessitates decisions whose very contestability can be understood as the political.

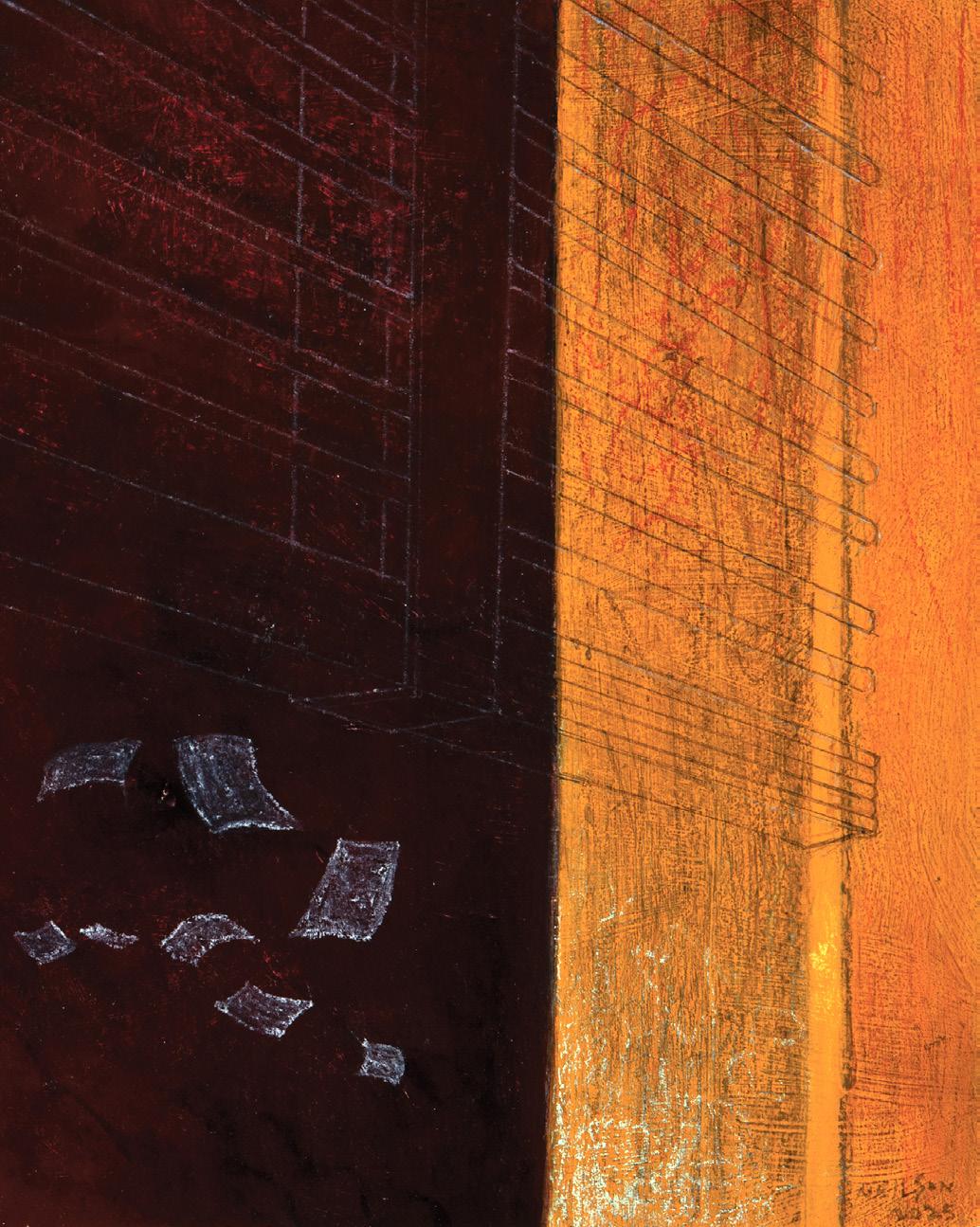

In in Rough Justice (just as we promised) a figure with a briefcase is seen leaving. Above him papers fall. Indeed, throughout the painting as a whole, pages flicker across or through each scene. The

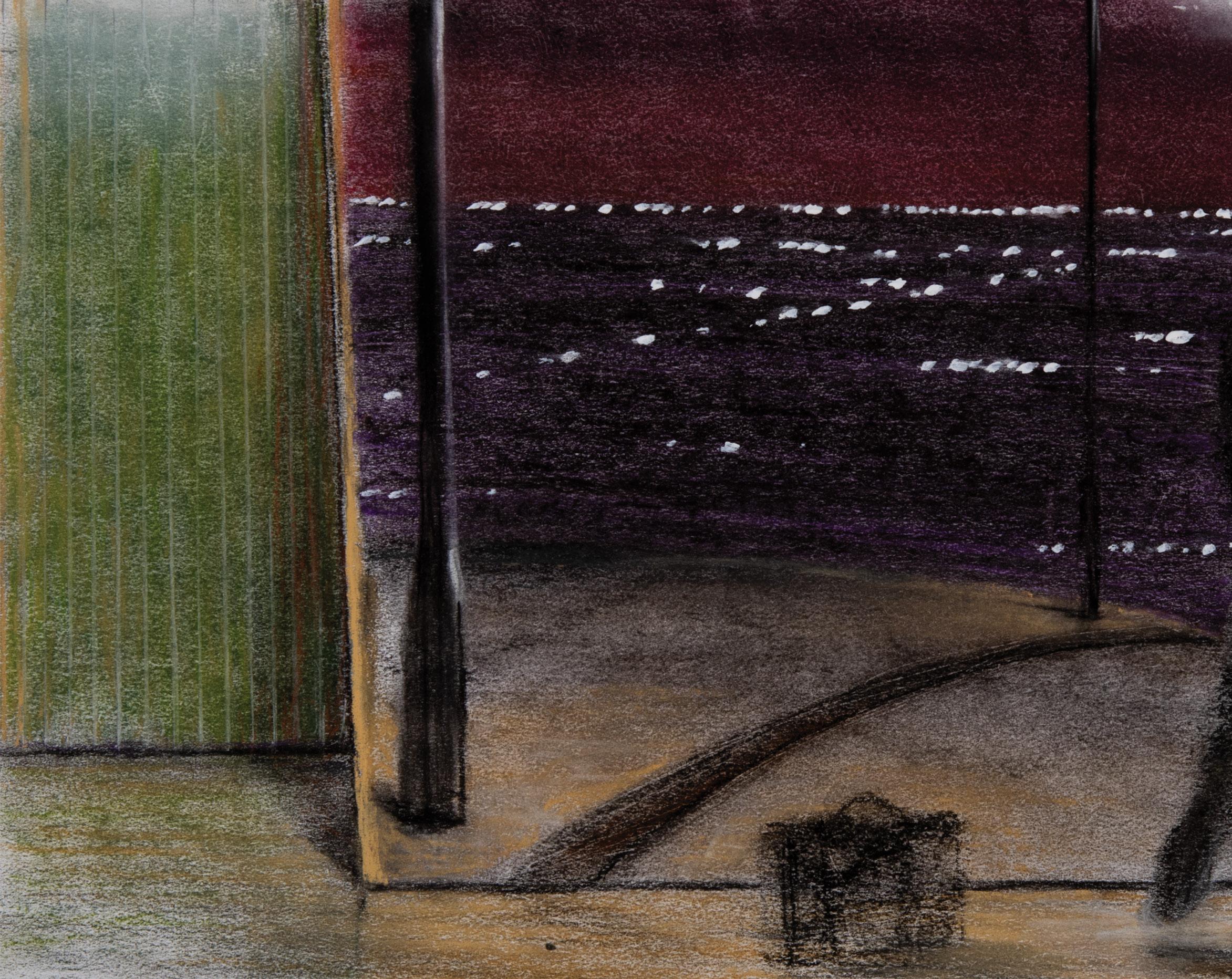

To the balcony II 2025 charcoal and oil on board 42.5 x 28 cm

pages might be evidence; they might even be decisions. Their ubiquity may register therefore as the open demand for justice. The figure leaving is carrying a briefcase, a briefcase whose closure might be the closure of the possibility of justice alluded to in the work’s title. The movement of solitary figures within the frame - their movement across and within the scenes - opens up, as a question, specifically when asked in relation to the title, of the possibility of justice giving the presence of fleeing figures. The response lies not in the prescription that a narrative of closure would enjoin, rather it can be found in the necessity to create a form of coherence with that form of creation that is itself informed by political and ethical decisions. Such a project is only possible within the work of art by the creation of scenes demanding coherence.

It is at this point possible to return to the drawings and smaller paintings incorporated in the exhibition. They, too, can now be understood as scenes. They are not excised from the work. They are not clips simply because the two larger paintings are not films. They are not parts of a whole. Each of these smaller works provides therefore a glimpse into what might come after. Each one, while complete in itself, demands within the context of the exhibition the question of its coherence within the totality that the exhibition has created. That question is of course the one that is operative through Neilson’s work as a whole. It should be noted that in a world marked by cruelty and catastrophe the question that each of us confront is the question of its coherence, that is the question of its meaning. That those questions elude us and force us back to the necessity to understand that which is continually encountered as the world, allows for recognition of Neilson’s art as perhaps the most acutely political being provided today.

Iqbal Barkat, Senior Lecturer in Screen Production at Macquarie University & Maree Delofski, Adjunct Senior Fellow at Macquarie University

“Nothing was sold. We had a marvellous exhibition and symposium, but still nothing sold... I thought, well, I’ve come to a dead end, you know, what do I do?” Peter Neilson’s candid reflection reveals a crucial insight about artistic practice: crisis often proves generative. Following his 2024 exhibition, faced with commercial disappointment and creative uncertainty, Neilson began Going Home (A Long Time Overdue) 2025—a painting of departing figures, the player taking his leave into his thoughts and future, travelling light, and of the emptying stage during “bump out” as they say in the theatre. Yet in the foreground an accordionist plays, perhaps forever. She’s surrounded by tiny angels—humble witnesses to the enduring power of art even as the audience departs and the lights go down. The painting became more than a response to disappointment; it became a meditation on endings that refuse closure, on departures that suggest new arrivals, on the stubborn persistence of art and attention in the face of emptiness.

From this work, something unexpected emerged. Small paintings began—extracted scenes, isolated moments, fragments that demanded their own existence. Rough Justice (Just As We Promised) 2025 was commenced and completed, generating its own constellation of smaller works. What began as a response to crisis evolved into a radical reinvention—a method of seeing that challenges the very foundations of how we understand the relationship between part and whole, fragment and totality.

The small paintings represent more than mere excerpts from larger compositions. They constitute what we propose to call “cutins”—a term borrowed from cinema that describes the transition from a wide shot to a detailed view of a specific element within the same scene. This cinematic concept proves particularly apt for understanding Neilson’s practice, which involves a violent act of extraction that simultaneously reveals and conceals, illuminates and obscures.

The cut-in, as a cinematic technique, carries with it an inherent violence—the violence of selection, of forced focus, of interpretive constraint. Cinema history is marked by moments where the cut-in functions as an act of violation, forcing the viewer’s attention whilst simultaneously exposing the subject to a form of visual violence. The extreme close-up of the eye being sliced in Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) literally cuts into the organ of vision itself; the fetishistic close-ups of feet in Tarantino’s films redirect desire through isolation; the lingering cut-in on the key in Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946) transforms an ordinary object into something laden with threat and meaning.

Yet perhaps nowhere is this violence more psychologically disorienting than in Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), where the cut-in achieves a kind of ontological instability. The knife that appears on the breadboard, the key that shifts from mouth to hand, the flower placed on the road—these objects refuse to remain passive props within the diegetic world. Through Deren’s obsessive return to these images in extreme close-up, the objects accumulate weight that exceeds both their narrative and symbolic function. The knife is never just a domestic implement; isolated by the cut-in, it vibrates with potential violence, its blade catching light in ways that suggest threat, desire, and self-annihilation simultaneously. The key, filmed so close

that its serrated edge becomes abstract, transforms from a tool of access into something occult—a talisman, a puzzle piece in a dream logic that refuses resolution. Unlike the MacGuffin (Hitchcock’s favourite plot device), which propels plot through narrative desire, Deren’s cut-ins arrest movement. They create ruptures in causality where the object itself becomes subject, gazed upon with such intensity that it seems to gaze back, implicating the viewer in the protagonist’s unravelling psyche. This is the true violence of the cut-in: not simply directing attention, but severing the object from stable meaning, leaving it—and us—suspended in interpretive free fall.

Each of these moments represents what André Bazin might have recognised as cinema’s capacity for both revelation and violation. Bazin famously critiqued montage for imposing meaning rather than discovering it, arguing that editing brings an element which reality itself does not possess and forces the spectator into a predetermined interpretation. The cut-in operates precisely through this mechanism of imposition: it doesn’t merely show us something we missed; it forces us to see it, wrenching the object from its spatial and temporal context, demanding attention and thereby changing the nature of what is seen. Where Bazin championed the long take and deep focus for preserving the ambiguity of reality, the cut-in performs the opposite function—it is montage at its most aggressive, isolating and intensifying meaning through violent extraction.

Neilson’s small paintings perform a similar operation. When he extracts a scene from Rough Justice or Going Home: A Long Time Overdue or Going Home (A Long Time Overdue), he commits an act of visual violence upon his own work, forcing into isolation what was once part of a larger narrative fabric. The larger “history” paintings invite circularity, continuity, contemplation on perspectives, character and narrative—they allow the eye to wander, to discover, to return. The smaller extracted works refuse this generosity. They arrest the moment, demanding immediate confrontation rather than gradual exploration. Yet this violence proves generative, creating new possibilities for meaning whilst simultaneously constraining others.

Neilson himself refers to these works as “vignettes,” a term that proves inadequate for describing their true function and effect. The vignette, by definition, suggests a self-contained scene or story, something complete in itself. Yet Neilson’s small paintings resist such containment—they are simultaneously autonomous and dependent, complete and fragmentary. They exist in a state of productive tension with their source paintings that the term “vignette” fails to capture.

The cut-in, by contrast, acknowledges this tension. It recognises that these works are not simply small paintings but rather acts of cinematic editing applied to the medium of paint. The cutin transforms the relationship between viewer and image, forcing a confrontation with details that might otherwise remain peripheral or unnoticed. They represent a rupture in the expected order in the world of painting that creates new possibilities for truth.

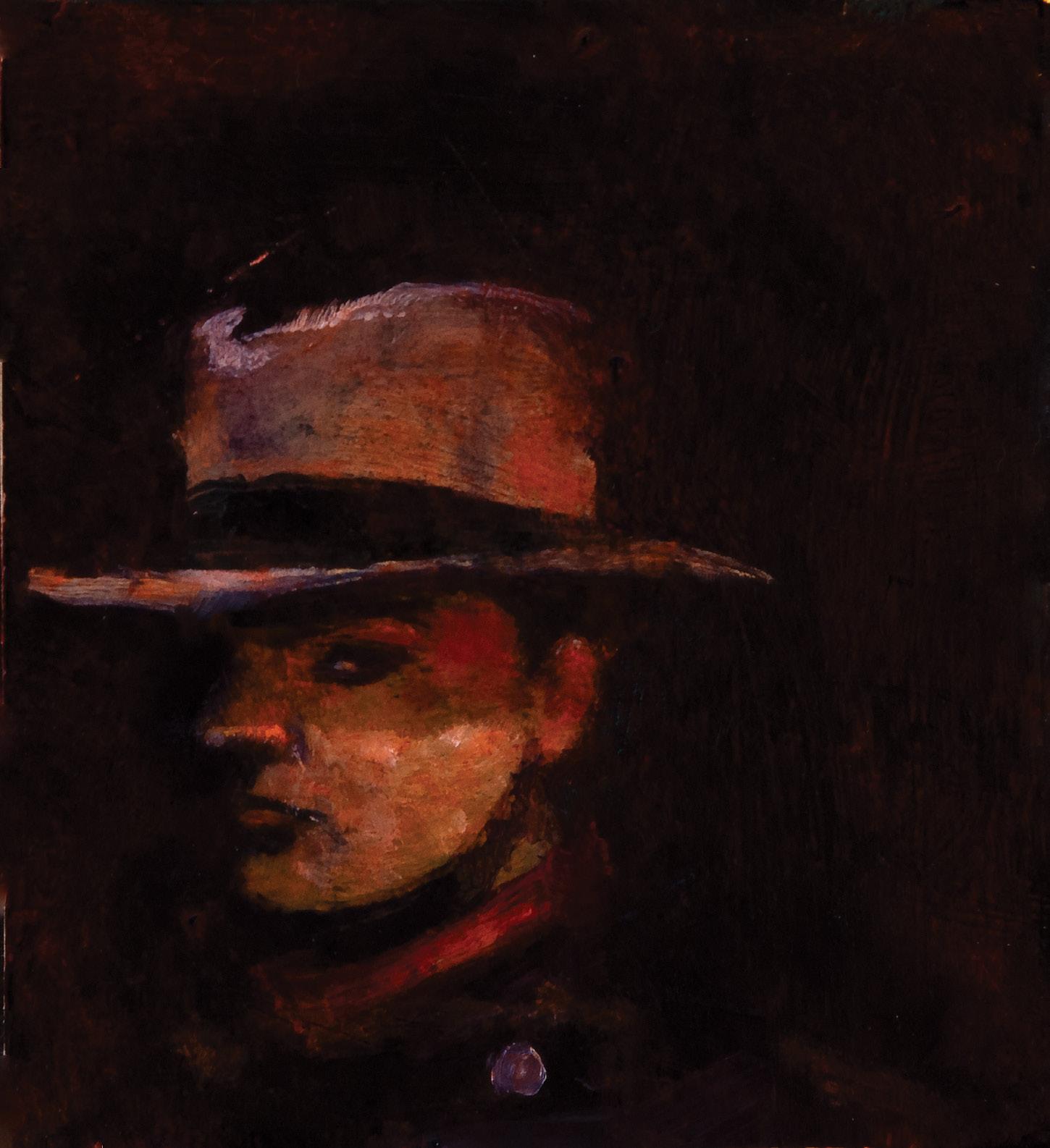

Consider Neilson’s “The Go-Between: Only Recorded Image,” extracted from Rough Justice. In the larger painting, this scene exists behind folding doors, conceptually present but visually occluded—suggested, implied, but never directly shown. The small painting reveals what was always there but hidden: a figure who has arrived, who stands waiting, whose presence we could only intuit from the narrative logic of doors and thresholds. Yet what emerges is not clarification but complication. This character now stares directly at us with unsettling stillness, their gaze confounding our assumptions about what we thought we understood. The figure tells us that the narrative suggested by the larger painting—of arrival, of passage, of theatrical movement—may not be what it seems. Behind every closed door in Neilson’s theatrical worlds lies not resolution but further mystery, not answers but more precise questions. This is not a vignette offering comfortable completion. This is a cut-in that multiplies uncertainty, that insists we reconsider everything we thought we saw in the larger work.

The relationship between Neilson’s large and small paintings illuminates a fundamental paradox in visual representation: the tension between openness and closure. The larger paintings, with their complex narratives and multiple entry points, invite prolonged contemplation and multiple interpretations. They are what Umberto Eco would recognise as “open works”—texts that actively involve the viewer in their completion, allowing meaning to circulate and proliferate across the painted surface.

The small paintings, by contrast, impose a form of closure. They direct attention, limit scope, provide what appears to be definitive statements about particular moments or objects. Yet this apparent definitiveness conceals a deeper violence: the cut-in doesn’t merely isolate but transforms, arresting movement and fixing what was fluid.

This transformation is perhaps best illustrated in Going Home (Travelling Light), the cut-in extracted from Going Home (A Long Time Overdue). The larger painting suggests movement between perspectival planes—these planes bleed into one another, creating transitions between painting and reality, between theatrical space and lived experience. The departing figure moves through these permeable boundaries with a kind of melancholic grace. But in the smaller work, something has changed fundamentally. The character has become ephemeral, translucent, clearly occupying a different plane of reality altogether. He is no longer departing but arrested, no longer travelling but stuck. The cut-in has transformed passage into stasis, journey into imprisonment. What was open has become sealed.

These works are, as Neilson admits, “almost quite cruel” in their self-sufficiency. They force viewers to encounter them as autonomous objects whilst denying access to their larger context, refusing the consolations of narrative continuity. This cruelty is not accidental but essential to their function. The cut-in’s violence lies precisely in this forced autonomy—the way it wrenches elements from their narrative context and insists upon their independent significance, even as that very independence becomes a kind of exile, a separation that can never be undone.

Particularly significant is Neilson’s decision to render many of the small paintings in charcoal and pastel rather than the oils of the source paintings. This shift in medium carries profound implications for our understanding of the cut-in’s function. These works bear an uncanny resemblance to the preparatory studies artists traditionally make before committing to a final painting—the sketches and explorations through which Rembrandt worked out the light in The Night Watch, or Picasso’s countless studies for Guernica, mapping compositional possibilities before arriving at the monumental final work.

Yet Neilson’s charcoal pieces are studies made after the fact, not before. This reversal dismantles one of painting’s most persistent fictions: that a work can ever be truly finished, complete, sealed against further investigation. The traditional study serves as scaffolding, discarded once the painting stands. Neilson’s post-facto studies suggest something more unsettling—that every painting remains perpetually unfinished, forever generative, always capable of yielding new forms of attention. The study, we assumed, leads to the painting. But here the painting leads back to the study, creating a temporal loop that refuses the comfort of completion. The work is never done; it simply opens onto further work.

As Neilson observes, these drawings provide “another view on the painting itself”—they are not reproductions but translations across media. The shift from oil to charcoal transforms our understanding of the painted scene by presenting it through radically different material conditions. The drawings possess what Neilson describes as a “looseness” compared to the “fixed” quality of oils—a material quality that mirrors their conceptual function as interrogations rather than conclusions. But what exactly do these interrogations reveal? What is it that we see in the charcoal that we could not see in the oil?

Here Neilson performs the work of the camera itself. Walter Benjamin recognised that cinema reveals hidden dimensions of reality—aspects of movement, gesture, and spatial relation that remain invisible to the naked eye. The camera creates what Benjamin called “a different nature” that “speaks to the camera than to the eye,” an “optical unconscious” made visible through mechanical reproduction. Neilson’s cut-ins operate similarly within the realm of painting. By extracting and translating scenes from oil to charcoal, from colour to monochrome, from the fixed to the loose, he reveals the painterly unconscious— dimensions of his own work that were present but imperceptible until isolated and transformed. He becomes the camera turned upon his own painted world, capturing moments to expose their hidden structures, their latent possibilities, their secret lives. The cut-in functions as a kind of mechanical eye, dissecting the painting to reveal what was always there but never quite visible, making manifest the unconscious of the image itself.

Cinema itself, at its most fundamental level, is a subtractive art. Editing is the art of removal—the filmmaker shoots hours of footage only to subtract, to cut away everything that isn’t essential, revealing the film that was always latent within the excess. Each cut is an act of subtraction that paradoxically creates meaning. Neilson’s cut-ins perform precisely this editorial function upon his own paintings. By subtracting the surrounding context, by cutting away the narrative fabric in which a scene is embedded, he reveals dimensions of the work that the fullness of the larger painting necessarily conceals.

This is not destruction. Subtraction is a procedure that reveals truth through removal—a process of clearing away to expose what lies beneath. The subtractive operates through negation, but this negation is profoundly generative: by taking away, we discover what remains, what persists, what was always essential but obscured by accumulation. When Neilson extracts scenes from his larger paintings, he enacts subtractive operations in the field of representation. The small paintings don’t destroy elements from the larger works but subtract everything else, allowing what remains to speak with new clarity and intensity. The subtraction functions as revelation: by removing, we finally see.

Returning to the circumstances of these works’ creation, we find in Neilson’s crisis a moment of radical creative transformation. Faced with disappointment, Neilson didn’t retreat from his practice but radicalised it, taking the subtractive step of cutting into his own paintings and forcing them to yield new meanings through careful removal. This subtraction proves generative precisely because it refuses the consolations of wholeness. Instead of creating new complete works that might repeat earlier patterns, Neilson embraces fragmentation as a creative principle—but fragmentation understood as subtraction, as a process that reveals truth through strategic removal.

This subtractive quality explains the cut-in’s generative power. Unlike the vignette, which simply isolates a pleasing detail, the cut-in subtracts strategically, creating an absence that demands new relationships, new meanings, new possibilities for understanding precisely through what it removes. The surrounding context doesn’t disappear but haunts the cut-in as a productive absence, as the ghost of the whole that makes the fragment meaningful. It transforms viewing from passive consumption to active encounter—we must supply what has been subtracted, must feel the weight of what is missing. The cut-ins acknowledge that meaning doesn’t reside in totality but in the relationships between fragments, in the gaps and connections that viewers must actively construct, in the space where what has been removed continues to exert its pressure on what remains.

Peter Neilson’s cut-ins represent more than a new direction in his artistic practice—they constitute a fundamental reimagining of the relationship between painting and cinema, whole and fragment, openness and closure. By applying cinematic logic to painted surfaces, Neilson reveals the inherent cinematicity of painting whilst simultaneously demonstrating painting’s capacity to exceed cinematic categories.

The violence of the cut-in—its forced isolation, its interpretive constraints, its cruel autonomy—proves ultimately generative. These works don’t simply fragment existing meanings but create new possibilities for meaning, new ways of seeing, new relationships between viewer and image. They demonstrate that crisis embraced, can become the foundation for radical creativity.

In an age increasingly dominated by moving images, Neilson’s cut-ins remind us that the image possesses its own form of temporal complexity—not the duration of cinema but the intensity of the arrested moment, pregnant with past and future, whole and fragment, revelation and concealment. They prove that painting, properly understood, has always been cinematic, and that cinema, at its best, has always been painterly.

The cut-in, then, represents not a departure from Neilson’s established practice but its logical culmination—the moment when his long-standing interest in theatrical spaces and narrative possibility finds its most precise expression. These small paintings don’t simply comment on their larger counterparts but transform our understanding of what painting can do, what seeing involves, and how meaning emerges from the productive tension between fragment and totality.

In the end, Neilson’s cut-ins remind us that every act of framing is an act of violence, every selection a rejection, every revelation a concealment. Yet it is precisely through such violence that art achieves its highest purpose—not the comfortable reproduction of existing reality but the difficult creation of new possibilities for truth. In embracing the cruelty of the fragment, Neilson creates works that are simultaneously generous and demanding, complete and incomplete, closed and endlessly open to new interpretation.

* Maree Delofski and Iqbal Barkat are currently making a documentary film on Neilson’s history paintings. The project is funded through a research grant from Macquarie University.

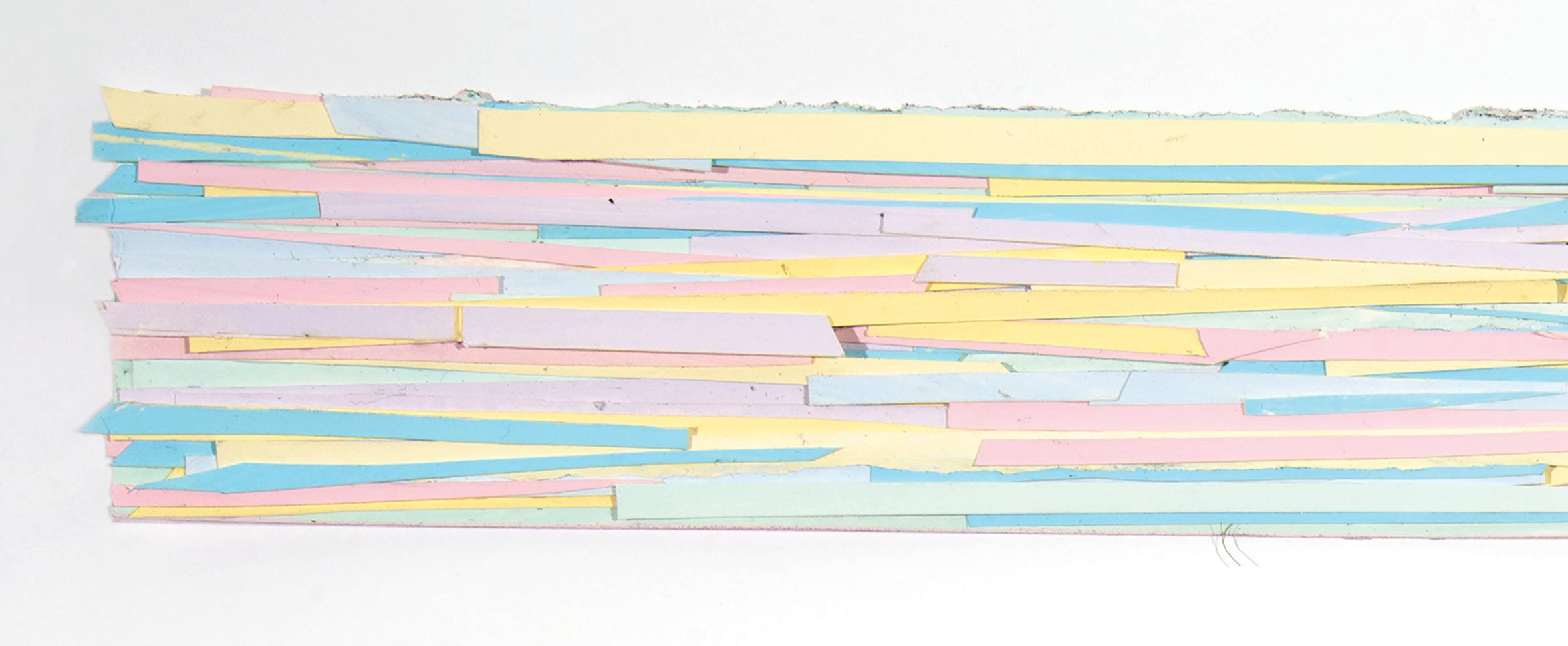

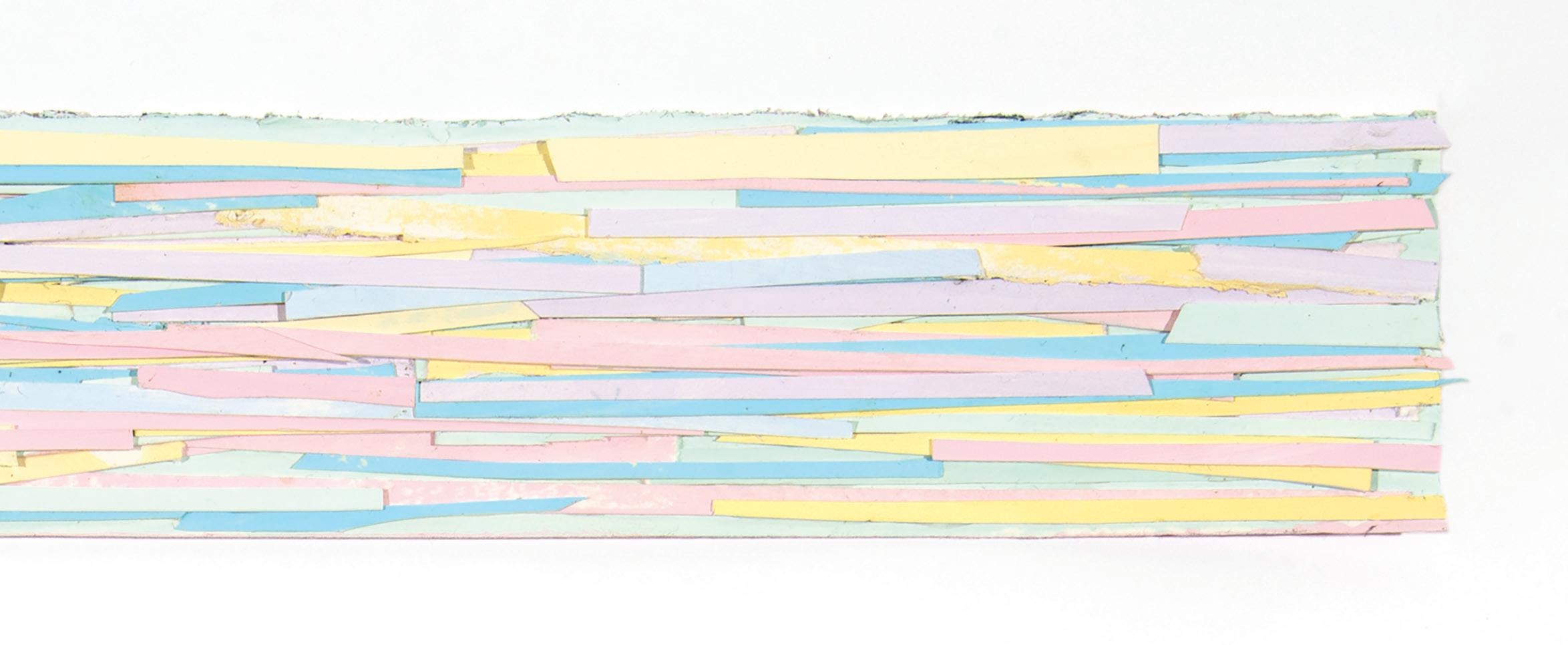

Sculpture . . . plus paintings and drawings

I am a painter who sculpts. So, for like souls, I look for painters/drawers who also made sculpture. I turn to Degas (“Give me a piece of paper and a stick of charcoal and I am happy”)

Degas wrote to a friend, “One amuses oneself only with what one doesn’t know how to do . . .”

The bricoleur - a word for which such English translations as “jack of all trades” and “handyman” are not quite adequate. The true bricoleur does not just make do, he prefers to make do. He enjoys turning materials and devices to uses for which they were not intended; he rejects the easy, orthodox approach. Since he is more interested in the process, in the bricolage itself, than in the product, he has an irrisistable itch to tinker, repair, modify, metamorphose. He is a problem-solver, to the point of creating problems for the pleasure of solving them. And in all these respects Degas (along with many other great artists) was an inveterate bricoleur. McMullen p. 350

And on that, I rest my case, and my sculptures.

Peter Neilson, 2025

All artwork photography: Viki Petherbridge

Peter Neilson’s small cardboard sculptures invite us into a world of whimsy and playfulness; almost involuntarily we smile and for a time leave behind the pressures of our troubled world.

Constructed with the skill and finesse of a highly accomplished artist, the chosen material, however, implies an acceptance of the ephemeral, of the transience of life. Perhaps it is this attitude that enables the artist to celebrate a breezy light-heartedness.

A number of the works play with the precariousness of balance. The sinking Sunking could conceivably be interpreted as a light-hearted nod to that famous French monarch, Louis xiv, Tall thin bend invokes an almost Zen-like stillness while Squally Weather Sunset is simply enchanting and quirkily captivating.

Each sculpture invites us to slow down: to peruse and laugh, to reflect and quietly enjoy.

Ken Scarlett OAM, 2025