Honoring Austin Bar Member Veterans

Wayne Cavalier

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

The military taught me problem-solving and working with people to resolve the problem and that is what I do now. I’m given a problem; I research solutions; I decide which solutions will best resolve the problem. I work with the person who has the problem to pick and implement the selected solution.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

After I was elected mayor of my town, I interacted with several topnotch lawyers and observing them led me to choose my law career.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

My military experience taught me that a truly resolved problem included a prepared “end-game strategy,” and that led me to estate planning.

How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

Those veterans who connect with the legal system are very well-served. Many veterans are not

served by the legal system because they do not connect with it; either they can’t connect or they don’t know how to connect.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

My military experience taught me to set a goal; determine the steps required to reach the goal; action the steps; and persevere. NEVER QUIT.

Sam Denton

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

I think the Army has a lot of best practices they teach that help you operate successfully in an office environment and from which I’ve benefited.

Listen to Eisenhower. Use the Eisenhower matrix – if you have folks to whom you can give tasks, push those tasks to them whenever you can, and retain only those tasks that are urgent and important.

You Can’t Expect If You Don’t Inspect. Tasking things down is great…but, where necessary, check over the finished product and, when possible, provide feedback, so that expectations are better understood in the future. Also, even when you assign tasks, since peo-

ple almost always have competing priorities, your task may not be prioritized unless you check on it. You can’t expect the task to always be completed (or completed to your standard) unless you check and show that it’s a priority.

The Backwards Timeline When you receive a mission (or a case), the first thing to do is to plot out the endpoint and then work backwards, plugging in the necessary milestones.

1/3 and 2/3 Rule. When you receive a mission, a case, or a project, you should do the initial analysis and planning and then make sure that you give those working under your direction at least 2/3’s of the time to do the actual work. This also applies elsewhere in the office – try to confine yourself to the first third of the timeline to do the planning and make the de -

cisions before you assign tasks to others. This is especially important for higher level managers, as the larger the boat, the longer it can take to turn.

Make the Plan, Start Movement, Refine the Plan. In order to follow the 1/3 and 2/3 rule, you may need to make the plan and allow others to begin carrying it out while you revise and perfect it. Don’t wait until things are flawless, as you’ll cheat those who are helping you of the valuable time they need to complete the project. Task, Condition, Standard. In the Army, they train you on “task, condition, standard.” They have broken most items down into processes, and the goal is to teach you the process and ensure that, given a task and a specific environment, you can complete that task successfully and to standard. I think that, as a result, I’m far more focused on commemorating and following repeatable processes than many attorneys that I’ve met. Having said that, one of my favorite things to do is crack a legal manual or CLE article and see a clearly outlined process that can take you to the successful resolution of a matter – so perhaps I’m giving the Army and myself too much credit.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

After observing corruption elsewhere in the world, I applied

to law school with the theory that I wanted to arm myself with the tools necessary to fight corruption, should it arise here.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

At its best, I see law as a service, one that you can perform for others and with which you can greatly and positively impact their lives. “Counselor” is my favorite title for an attorney, as I think that one of the most rewarding parts of our job is to carefully listen to someone’s problem and then help them solve it.

How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

There are so many services and benefits for veterans…but there can be more. The percentage of veterans who are homeless is disproportionately large when compared to the percentage of the overall population that veterans represent. Additionally, sadly, we’re seeing reductions that have negative impacts on veterans. This encompasses everything from the erosion of a federal workforce that gave preference to veterans; to the loss of critical caregivers and research dollars; to cuts to Medicaid and SNAP upon which, again, a disproportionately large number of veterans rely.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

The most important thing that the military taught me was that

leadership is different than management and, while both are very important, leadership can be what the military would refer to as a “force multiplier.” Intentional and excellent leadership can inspire others, with disparate goals and personalities, to row in the same direction and with more force.

Claude Ducloux

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

My Army experience helped me realize how precision in your demeanor and your communications with others can make or break your career. Like many others, I made my mistakes, learned from them, and tried not to repeat them. I wanted everyone to know that I was honest, dependable, and more than anything else, I did my share of every job big, small, or dirty and humbling. Doing little things well earns you respect and friendship. Some of my Army friends from 50 years ago still text each other almost daily, even though we haven’t seen each other in decades.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

I always wanted to be a lawyer, and my grandfather and great-grandfather were lawyers in Switzerland. I always thought that, somehow, they might be guiding my life toward the law. I still feel that way today.

Are there particular areas of

law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

I helped prepare court-martial paperwork for the 1st Cavalry Division as one of the first “paralegals” – a new word in the legal lexicon. Before I ended my time in service, I was writing scripts for the newer lawyers on how to try court-martial cases. I knew that’s what I would do, too: try cases in court. Moreover, I learned so much from the Army’s Manual for Courts-Martial, which showed lawyers the elements of each crime, i.e. what you have to prove to win. I think about that elemental approach to win cases and always ask myself: “What do I need to do to win this case?” Just like in the Army.

How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

Unfortunately, we only give lip-service and “thanks” to the mighty contributions our veterans face. That’s because too few of our

politicians (men AND women and too few of our presidents) have ever worn a uniform. Veterans are a valuable resource for mentoring and guidance, and we should give them care, honor, and opportunities to succeed.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

My most valuable skill was realizing and gaining confidence that I can overcome sleeplessness, fatigue, harassment, and pressure and still succeed. I will handle anything you throw at me. In other words, the most important result of my service was self-confidence and resilience. I still feel that way.

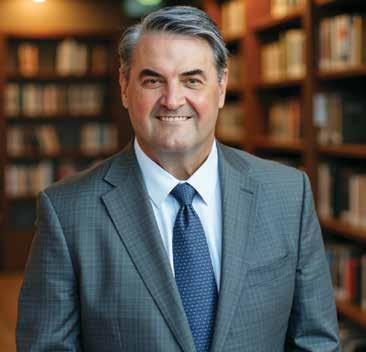

Judge Daniella DeSeta Lyttle

Daniella DeSeta Lyttle was elected by Travis County voters to the 261st District Court in 2022, becoming both the first Latina and the first female Army

veteran to serve on this court. She presides over a wide range of civil and family-law cases, including business, commercial, administrative, consumer, real estate, divorce, child-custody, and Child Protective Services matters.

Before her election to the bench, Judge DeSeta Lyttle was a full-time trial lawyer in Austin. She litigated cases not only in the district courts of Travis County but also across central Texas and in federal courts throughout the state. As the founder and managing partner of Lyttle Law Firm, PLLC, she specialized in Immigration, Family, Business, and Entertainment Law. Her extensive experience as both a litigator and a judge reflects a lifelong commitment to justice, service, and advocacy for her community. Prior to her legal career, Judge DeSeta Lyttle served in the U.S Army as an enlisted combat medic in an infantry unit.

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

I joined the Army at 17, straight out of high school, and served in an infantry unit with the military occupational specialty (MOS) of Combat Medic. That experience shaped the foundation of who I am today. The determination, perseverance, attention to detail, and work ethic I developed in the military carried directly into my work as a lawyer, where preparation, discipline, and tenacity were essential to advocating effectively for my clients. Those same qualities now guide me on the bench as a district judge. Perseverance allows me to carefully work through the most complex legal issues, while attention to detail ensures fairness and accuracy in every decision I make. Most importantly, the Army instilled in me a deep sense of duty and service — a commitment that I strive to honor each day by upholding the law and ensuring access to justice for every litigant who comes before my court.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

My decision to pursue a legal

career was deeply personal. Growing up in a low-income neighborhood, I witnessed firsthand how Latinos, immigrants, and people of color were too often taken advantage of because of language barriers or a lack of access to legal resources. After serving in the Army, I carried with me the discipline, resolve, and sense of duty the military instilled in me. Those experiences strengthened my commitment to address the inequities I had seen throughout my life. As a lawyer, I was able to advocate directly for clients who needed a voice and ensure they had fair access to justice. Now, as a district judge, that same motivation informs every decision I make on the bench. I am committed to maintaining fairness and accessibility in the courtroom, ensuring that every litigant — regardless of background or circumstance — is treated with respect and has an equal opportunity to be heard.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

While the skills I gained in the Army — discipline, attention to detail, and perseverance — are valuable in all areas of law, I have found that my ability to remain calm under stress and pressure is particularly resonant in family law cases. Many of the individuals who come before the court are experiencing profound emotional pain, and navigating those situations requires patience, empathy, and a steady presence. My military background trained me to stay composed in high-pressure environments, assess situations clearly, and make decisions with clarity and fairness — qualities that are essential when guiding families through some of the most challenging moments of their lives. In this way, my service continues to inform how I approach the courtroom and support those seeking justice.

How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

The legal system has many resources available to veterans, but

it often falls short in addressing the unique challenges they face, particularly when it comes to mental health. Issues such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety are prevalent among veterans, yet the system is not always equipped to respond to these needs in a timely or effective manner. I believe more specialized support, including access to mental health professionals trained in veterans’ issues and greater coordination between the courts and veteran services, would make a meaningful difference. By prioritizing mental health and providing tailored resources, we can ensure that veterans receive not only justice, but also the support they need to rebuild and thrive in civilian life.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

The military instilled in me a foundation of leadership and discipline that has been invaluable throughout my legal career. From the Army, I learned the importance of accountability, decisiveness, and leading by example — skills that helped me advocate effectively as a lawyer and now guide proceedings fairly as a district judge. Discipline taught me to approach complex legal matters methodically, maintain focus under pressure, and persevere through challenges, while leadership reinforced the responsibility to serve others and make thoughtful, principled decisions. Together, these qualities continue to shape how I approach my work, ensuring that I act with integrity, fairness, and a commitment to those who rely on the legal system.

Kyle Ryman

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

It has deeply influenced how I approach litigation. War and litigation are just different tools for resolving what are fundamentally disputes between people. That’s why I always focus on the people involved. So in both the Army and now in the law, I don’t pick fights to pick fights. I pick fights that I

think will lead the people involved closer to resolution of the matter — so my clients can get relief.

Just as important is how it shaped me as a trial lawyer. America’s sons and daughters are an incredibly diverse bunch. And you’ve got to figure out how to relate to them if you want to get them all rowing in the same direction in the Army. The same is true for the jury. They’re diverse. They come from different backgrounds and hold different priorities. You’ve got to figure out how to relate to them at trial; what’s going to persuade them to find in favor for your client. And that’s not always what us lawyers think is enough or even the most persuasive.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

Continued service. There’s a lot of momentum for junior officers getting out to go get their MBA and go work on Wall Street. But I wanted to continue serving my community. And there’s no better way to do that as a veteran than becoming a lawyer. You can do good and get paid in the process. You’ve got access to tools nobody else does — the courts! And when you practice the kind of law I do, you get to see how your work changes lives. You get to right wrongs; to correct injustice. You get to make your clients’ lives better. There’s nothing more professionally rewarding than that.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

In a way, yes. The Army is built on procedure. You’ve got regula-

tions and policies for everything. Nothing gets done until you navigate the often Byzantine bureaucracy of the Army. So when I got into the law, I wasn’t shocked at how long things took or all the procedural hoops you’ve got to jump through as a lawyer. If anything, I felt at home. But the other thing the Army teaches you is that every rule, every procedure has an exception. And that’s spot on in the law. All that’s to say the law is full of interesting questions and substance. But what resonates most deeply with me is how analogous the law is to the Army procedurally.

How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

I think we don’t do enough to encourage veterans to enter the law. Post World War II, we had a wave of veterans go to law school or otherwise enter the law. We haven’t had that since. Veterans in the law are a rare breed. We need to change that. We need more veterans in the law — as judges, as lawyers, as paralegals, and as

staff. We do that and we’ll be filling the law with people who have a demonstrated commitment to public service. Access to justice— for veterans and civilians alike— will take care of itself.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

I commanded three companies in the Army. I got to learn firsthand what it takes to build an effective team of diverse professionals. There was no better training than that to start my own law firm. I was able to hit the ground running from day one, setting clear objectives and then building effective systems to accomplish them. I couldn’t have done it so easily without my time in the Army to lean on.

Mark Santos

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

“Mission First, People Always,” is a phrase that virtually anyone

with a military background has heard before. It simply refers to the fact that while mission accomplishment is always the primary goal, no mission can be accomplished without the people who carry it out. Put differently, for military leaders, meeting the needs of people is a responsibility that is of equal importance to meeting the requirements of any mission. The elements of “mission” and “people” aren’t opposed to one another, rather they work hand in hand — good leaders find balance between the two and success is the result. I think that lawyers constantly face the same

need for balance, with cases or transactions and people.

Most of us lawyers are competitive people. We want to win. We work hard to win. We expect to win. Our shelves aren’t filled with opinions from or tokens of memory on the cases we lost or the transactions that never closed. No, we memorialize our successful cases or “missions” on our websites, in social media posts, on our bookcases, and in our files. But, in each of those successes (or failures), I think, regardless of how small a lawyer’s practice group or team might be, there were likely other people involved. Clients who needed our help and expertise. Co-counsel with gifts that were complementary to our own. Paralegals and other legal professionals who made us look good and kept us from making mistakes. Family and friends who were there after another long day in front of the computer. Judges, juries, or deal partners who heard our arguments, believed in our theme or us, and decided to rule in our client’s favor or sign the contract. I hope that one day when I

“hang up my shingle,” I’ll be able to say that I did my best to always try to find that balance between mission and people.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

Initially commissioned as an army intelligence officer at Texas A&M University, the Army allowed me to proceed directly to law school under its Educational Delay program; after which, I was selected for the Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps. I was then blessed to spend the next four years of my life on active duty as a member of the Army’s Trial Defense Service “Defending Those Who Defend America.” I had the privilege of representing soldiers at courts-martial, in administrative separation proceedings, and in other adverse actions under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).

In other words, there was never really any doubt that I was pursuing a legal career, regardless of my time in service. But I will say that a motivation for my entry into private practice was a desire to work alongside and against the best and brightest non-military lawyers and advocates in the legal profession — to test my own skill with and against different peers and adversaries who the profession considers “super” or “best” lawyers. Luckily, I’ve been blessed to do that also.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

When I was transitioning from military to private practice, a mentor of mine keenly observed that the position I was interviewing for at an Austin law firm’s energy and regulatory section was a great fit for me. She noted that I’d simply be moving from one highly regulated environment (the military) to another (energy companies and utilities). Different games with different playbooks but very similar basic tenets and aspects from a legal practice perspective. It turns out she was right. Something must have “resonated” with me because I’ve now been an energy and regulatory lawyer for over 20 years. How do you think the legal system serves (or fails to serve) vet-

erans, and what changes would you like to see?

Wow. Probably not enough pages in this edition of the Austin Lawyer to provide a complete answer. I’ll say this: I think that veterans can present challenges that other clients do not — especially when the veteran isn’t advocating strongly for themselves. I think that the values of duty, selfless service, and personal courage can be so strongly ingrained in the DNA of a veteran that we are likely to miss just how harmed that veteran might be in a particular case under a particular set of circumstances. A veteran with those core values is often the last to raise a hand for help and may be the first to say that help isn’t needed. It’s true that they need help, but they may not know how to ask for or receive it.

I’m not sure that any kind of change is necessary but certainly an awareness might make us better servers of those who’ve served. Look out for when that veteran client or witness gives you a consistent “yes, ma’am” or “yes, sir” and few follow-up questions; or when that client doesn’t seem as “injured” by their situation or position as other similarly situated clients; or when a seemingly “successful” and “happy” veteran suddenly takes a downward turn not anticipated or detected by those around them. You may have a smart, professional, and resilient person in front of you. You may also have someone who has put others before themselves for so long that they can’t see their own needs in a normal light.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

See my comments preceding on “Mission First, People Always.” Beyond that, my family and friends sometimes hate it, but my eyes open around four a.m. most mornings, regardless of whether I want to sleep longer. After waking up, I usually try to keep myself from my computer for an hour or two as I get caffeinated, digest what’s going on in the world, and workout. After that, I’m usually pretty clear-eyed and focused when I look at my calendar and open my email inbox to assess the next emer-

gency or problem to be solved for the day. If I’m lucky, I’ll have the initial plan for dealing with the emergency or problem to be solved worked out when I get to the office around eight a.m.

I don’t think that I “do more before nine a.m. than most people do all day” (which is a line used in an Army advertising campaign in the 1980s), but early starts to the day have served me well throughout my legal career.

Kevin Terrazas

How has your military experience influenced your approach to practicing law or working with clients?

The Army taught me many things, including the importance of both leading and being part of a team. I learned that teams are most effective when they work collaboratively, which has translated to a team-first mentality at the firm. Also, when you are serving, it is much harder to put yourself above the mission because others are relying on you. This instilled a strong sense of client-service — to put the client’s interests above our own.

What motivated you to pursue a legal career after your time in the service?

I actually determined that I was going to leave the military while I was serving in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom. I did not know what I was going to do next. But one of my closest friends during the deployment was a JAG officer, and he recommended that I apply to law school. Since I had always been interested in how we govern ourselves, I decided to give it a try.

Are there particular areas of law that resonate with you more deeply because of your military background?

I wouldn’t say that there’s one particular area of law that resonates more deeply because of my military experience, but it does drive me to be passionate about representing others and doing everything I can to get the best outcome for my clients.

How do you think the legal sys -

tem serves (or fails to serve) veterans, and what changes would you like to see?

The legal system has made strides in recognizing the unique needs of veterans, particularly as it comes to mental health and the unique challenges that veterans may face because of their experiences. For example, I was just in Comal County recently and the county court has a Veterans Treatment Court, which diverts veterans from the traditional criminal justice system to focus on their unique needs. At the same time, there are still gaps — particularly in navigating benefits, accessing affordable legal support, and addressing issues like housing that often overlap with legal problems. I’d like to see more specialized courts and outreach programs that connect veterans with attorneys who understand both the law and military culture.

What leadership or discipline skills from the military have been most valuable in your legal career?

My military service taught me that leadership isn’t about giving orders — it’s about accountability, setting an example, and taking responsibility for outcomes. That mindset has been invaluable in earning trust with clients and colleagues. In addition, my service experience taught me to remain calm and decisive in high-pressure situations. Being shot at and having rockets fired at you definitely puts practicing law and its high-stress environment into perspective. AL

Ari Cuenin is a partner at Stone Hilton, where he litigates complex government disputes. He has presented more than 30 arguments in state and federal courts, and has been involved in more than a dozen U.S. Supreme Court cases for the State of Texas.

The following are summaries of selected criminal opinions issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The summaries are overviews; please review the entire opinions. The subsequent histories are current as of October 20, 2025. Below are recent decisions from the United States Fifth Circuit of Appeals.

TAKINGS: Fifth Circuit rejects constitutional challenge in construction dispute.

Mesquite Asset Recovery Group v. City of Mesquite (Fifth Cir. No. 24-11025). The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of developers’ takings claims arising from the City of Mesquite’s termination of a master development agreement. The plaintiffs alleged that the city’s refusal to extend contractual deadlines, and its about-face on enforcement of a prior flood-control variance, constituted an uncompensated taking in violation of the Fifth Amendment. The panel held that the developers’ allegations failed to show that the city acted in its sovereign rather than its commercial capacity. When a government acts as a market participant in contracting, any dispute sounds in contract, not sovereignty. Actions that would constitute mere

breach by a private party do not transform into Fifth Amendment takings merely because a contracting party is a municipality. Because the alleged wrongs were intertwined with contractual obligations and renegotiation efforts, the city’s conduct was commercial, not regulatory, and thus no taking occurred. The court also upheld dismissal of the related federal declaratory-judgment claim and remanded residual state-law contract issues to state court.

This decision reinforces a clean demarcation between contract disputes and constitutional takings. As Mesquite illustrates, claims framed as those for “inverse condemnation” are barred when the underlying relationship is contractual. Government contractors should take note of this distinction when navigating municipal-development disputes: breach remedies lie in contract law, not the Fifth Amendment. The opinion provides clear Fifth Circuit guidance, consistent with Preston Hollow Capital, L.L.C. v. Cottonwood Development Corp., 23 F.4th 550 (5th Cir. 2022), when a purported Fifth Amendment claim actually “sounds in contract.” Municipalities face no special exposure to such contract-based takings claims simply because they are public entities.

PRISONER LITIGATION: Panel rejects inmate medical claim for lack of standing.

Haverkamp v. Linthicum (5th Cir. No. 24-40709). Haverkamp, an inmate serving a 45-year sentence for child abuse, sued several Texas prison officials, claiming that the denial of “sex-reassignment” surgery violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the claim – not on sovereign-immunity grounds as the district court had ruled but for lack of standing. The court held that Haverkamp failed to allege a concrete, redressable injury traceable to any defendant. Although Haverkamp sought prospective injunctive relief under Ex parte Young, the alleged injury hinged on speculative medical decisions within prison doctors’ discretion.

Even if sovereign immunity did not bar the suit, Haverkamp still could not show that the requested injunction would remedy a cognizable constitutional harm. Judge Wilson’s opinion for the unanimous panel emphasized that federal courts cannot compel state medical providers to perform a surgical procedure in the absence of any indication that a physician treating Haverkamp would ever recommend the surgery, and that the prison medical policy’s silence on “sex-reassignment” procedures did not itself amount to discrimination among similarly situated inmates.

For civil-rights practitioners, Haverkamp underscores the skepticism toward prisoner challenges seeking medically elective procedures. The ruling narrows potential use of Ex parte Young to force specific medical interventions and clarifies that standing – especially inadequate redressability – can serve to dispose of such suits without reaching sovereign immunity or the merits of equal protection. And for institutional defendants, Haverkamp may provide additional support for arguing that disputes over medical discretion or treatment protocols do not present justiciable constitutional claims.

RELIGIOUS LIBERTY: Divided panel affirms summary judgment, dismissing employment claims under church-autonomy doctrine.

McRaney v. North American Mission Board (5th Cir. No. 2360494). In a 2-1 decision by Judge Oldham, the panel affirmed summary judgment for the Southern Baptist Convention’s North American Mission Board (“NAMB”), holding that the First Amendment’s church-autonomy doctrine barred plaintiff Will McRaney’s tort claims. McRaney had alleged defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress (“IIED”) arising from the termination of his employment by a coordinating Baptist convention and subsequent disputes with NAMB. The Fifth Circuit ruled that adjudicating McRaney’s claims would impermissibly require inquiry

into ecclesiastical matters – ministerial selection, internal communications, and religious discipline – foreclosed by the First Amendment. Tracing centuries of Anglo-American precedent, the opinion reiterated that civil courts lack authority to resolve controversies over “faith, scripture, and religious doctrine.” Because McRaney’s employment and reputational claims were inseparable from matters of religious doctrine and polity decisions, they were non-justiciable.

McRaney is a major Fifth Circuit articulation of the modern church-autonomy doctrine, in line with other recent decisions like Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, 591 U.S. 732 (2020), and Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. EEOC, 565 U.S. 171 (2012), in shielding religious institutions from suits implicating ecclesiastical judgment. The McRaney majority extended that solicitude notwithstanding Judge Ramirez’s argument in dissent that, because “there is no unified ‘Baptist Church,’ there can be no ‘intrachurch dispute’ or dispute about ‘church government’ in this case.” For counsel serving religious organizations, McRaney reflects an opportunity for limiting discovery and litigation over internal communications and ministerial disputes, even for ostensibly “secular” claims. Said differently, even facially neutral claims – defamation, tortious interference, or IIED – may be barred when their resolution would entangle courts in matters of religious governance. AL

Laurie Ratliff is a former staff attorney for the Third Court of Appeals. She is boardcertified in civil appellate law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization and owner of Laurie Ratliff LLC.

The following are summaries of selected civil opinions issued by the Third Court of Appeals during September 2025. The summaries are an overview; please review the entire opinion. Subsequent histories are current as of October 13, 2025.

>ATTORNEY’S FEES: Court reverses appellate-fee award when not contingent on successful appeal.

YCUL, LLC v Peterson, No. 0324-00429-CV (Tex. App.—Austin Sept. 16, 2025, no pet. h.) (mem op.). In a dispute over the sale of real property, the jury found that the deed at issue failed to convey the property from Peterson to

YCUL because of failure of consideration or fraud. The trial court signed a judgment on the verdict and awarded Peterson trial-court fees and appellate fees if appealed to the court of appeals and an additional fee award if briefs were filed in the supreme court. Peterson sought attorney’s fees under Business and Commerce Code Section 27.01(e) that allows fees against a person who commits fraud in a real estate transaction. The court of appeals affirmed the trial-court fee award. YCUL challenged the appellate attorney-fees award which failed to make the award contingent on Peterson’s success on appeal. The court held that the failure to condition the award of appellate fees on an unsuccessful appeal by YCUL was error. The court concluded the error was harmless as to the court of appeals fee award since YCUL was unsuccessful. The court, however, modified the appellate-fee award for the supreme court to be conditioned on the appeal being unsuccessful and affirmed the remainder of the judgment.

FAMILY LAW: Court reverses child-support amount for insufficient evidence.

Ly v. Nguyen, No. 03-23-00535CV (Tex. App.—Austin Sept. 19, 2025, no pet. h.) (mem. op.). In this divorce appeal, husband challenges the trial court’s deviation from child-support guidelines. The trial court ordered husband to pay the maximum standard child support under the guidelines, or

$1,840 per month. Family Code Chapter 154 uses the net resources of the obligor to determine the amount of child support. If the child support ordered by the trial court varies from the guidelines, the court must make specified findings without out regard to Rules 296-299 findings of fact and conclusions of law. With one child, the statutory percentage of husband’s monthly net resources to be allowed for child support was 20 percent. Thus, the award of $1,840 per month requires an implicit finding that husband had at least $9,200 in monthly net resources. Husband contended his monthly net resources after deductions was $1,619. Thus, applying the 20 percent guideline, his child-support obligation would be $323.98. The court of appeals held that the trial court’s implicit finding that husband had net monthly resources of at least $9,200 is contrary to the overwhelming weight and preponderance of the evidence to be clearly wrong and unjust. The court concluded that on the existing record, it could not render judgment on the amount of support owed. Accordingly, it reversed and remanded for a new trial on the child-support issue and affirmed the remainder of the judgment.

DECLARATORY JUDGMENT:

Court holds that claim for attorney’s fees survives nonsuit.

Toscano v. Brown, No. 03-2500142-CV (Tex. App.—Austin Sept. 19, 2025, no pet. h.) (mem.

op.). Toscano sought declaratory relief to prohibit Brown from blocking an easement on her property that allowed Toscano access to his landlocked property. In response to Brown’s motion for summary judgment, Toscano nonsuited without prejudice. The trial court granted summary judgment on the merits for Brown and awarded Brown attorney’s fees. The court of appeals rejected Toscano’s argument that the nonsuit deprived the trial court of jurisdiction. The court concluded that the trial court erred in granting summary judgment on the merits because the nonsuit terminated the case from the moment the notice of nonsuit is filed. The nonsuit, however, did not prevent the trial court from awarding attorney’s fees under the UDJA. A claim for attorney’s fees under the UDJA constitutes a claim for affirmative relief that survives a nonsuit. The court affirmed the attorney’s fees award but reversed and rendered judgment that Toscano’s claims are dismissed without prejudice. AL

The following is a summary of selected criminal opinions issued by the Third Court of Appeals from April 2025. The summary is an overview; please review the entire opinions. The subsequent history is current as of October 6, 2025.

>SENTENCING:

Sufficiency of evidence and recusal of trial judge: Sufficient evidence supported trial court’s sentencing decision and trial counsel was not ineffective in failing to file a motion to recuse the trial judge.

Jaquez v. State, 712 S.W.3d 217 (Tex. App.—Austin 2025, no pet.). Jaquez pleaded guilty to murder and the trial court sentenced

him to 25 years’ imprisonment. On appeal, Jaquez asserted that (1) the trial court’s finding that he was ineligible for community supervision was based on legally insufficient evidence, and (2) counsel provided ineffective assistance when she failed to pursue a motion to recuse or disqualify the presiding trial judge after learning the judge had presided over a different case in which Jaquez’s uncle was the deceased victim. Regarding the punishment assessed, article 42A.102(b)(4) of the Code of Criminal Procedure provides that a person convicted of murder is ineligible for placement on community supervision “except that the judge may grant deferred adjudication community supervision on determining that the defendant did not cause the death of the deceased, did not intend to kill the deceased or another, and did not anticipate that a human life would be taken.” Jaquez argued that the plain language of that provision “requires the trial court to first correctly determine the three factors that would allow a consideration of deferred adjudication community supervision and then gives the trial court discretion to impose any sentence within the statutory range.” In his view, “there was no evidence presented that he anticipated there would be a loss of life,” and the sentence should be reversed for that reason. The appellate court disagreed, concluding that “nothing in the statute requires the trial court to grant deferred adjudication community supervision even

“Information is power, the not knowing is devastating.”

if the three factual prerequisites exist” and that there was nothing in the record to suggest that the trial court abused its discretion by sentencing Jaquez to 25 years’ imprisonment, which was within the statutory range of punishment. Regarding ineffective assistance, Jaquez contended that counsel should have filed a motion to recuse the trial judge under Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 18b, which requires that a judge shall recuse herself in any proceeding in which her impartiality might reasonably be questioned or she has a personal bias or prejudice concerning the subject matter or a party. Jaquez argued that the judge had heard prejudicial information involving Jaquez’s family during sentencing in a prior case and that she should have recused herself for that reason. However, the appellate court concluded that there was no evidence to overcome the presumption that the judge’s sentencing decision was based on the facts developed during Jaquez’s case, and it was unable to conclude that the trial judge was required to recuse herself or that she would have granted a motion to recuse had trial counsel filed it.

SEARCH AND SEIZURE: Cell phone search-warrant affidavits: Officer’s affidavit provided magistrate with a substantial basis for finding that probable cause existed to believe that searching defendant’s cell phone was likely to produce evidence in the investigation of offense.

Llanas v. State, 711 S.W.3d 766

(Tex. App.—Austin 2025, no pet.). Llanas was charged with murder, specifically by shooting the victim during a drive-by attack. During the investigation into the offense, officers seized Llanas’s cell phone pursuant to a warrant. Llanas moved to suppress all evidence obtained from a search of the phone, arguing that the officer who prepared the affidavit provided no evidence that the cell phone had been used to plan, discuss, commit, or conceal a crime. The trial court denied the motion, and Llanas pleaded guilty. The appellate court affirmed, explaining that a judge may issue a cell-phone warrant only on a peace officer’s application, which must state the facts and circumstances that provide the applicant with probable cause to believe that: (1) criminal activity has been, is, or will be committed and (2) searching the telephone or device is likely to produce evidence in the investigation of the criminal activity described. In this case, the officer’s affidavit alleged facts tying both Llanas and his cell phone to a series of driveby shootings, including the one in which the victim was killed. The court summarized that evidence in detail and concluded that the magistrate could have reasonably inferred from the facts alleged in the affidavit that the officer had probable cause to believe that the phone belonged to Llanas and that searching the phone was likely to produce evidence in the investigation of the drive-by shootings and the victim’s death. AL

Divorce and Child Custody Surveillance ~ Undercover Background Checks Computer & Phone Forensics Corporate Investigations Expert Testimony and more Austin, Round Rock, & Dallas STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Featured in

Zak Hall is a staff attorney for the Third Court of Appeals. The summaries that follow represent the views of the author alone and do not reflect the views of the Court or any of the individual justices on the Court.

August 2025 District & County Court Jury Trial Verdicts

BY VELVA PRICE, TRAVIS COUNTY DISTRICT CLERK

CIVIL

Lee Lewis v. Alejandro Bueno

Cause No.: D-1-GN-23-009090

Judge: Sherine Thomas

Dates: August 18-21, 2025

Attorneys:

Plaintiff: Jerry Lee, III, Thomas J. Henry Law (San Antonio)

Defendant: James e. Ajay, Witt, McGregor and Bourland, PLLC (Waco)

Summary: On or around March 19, 2022, Plaintiff claims that, as a passenger, he was injured by the defendant’s negligence. The defendant was found negligent and 11 jurors awarded: Past medical care expenses - $16,959; future medical care expenses - $0; past physical pain and mental anguish - $2,000; future physical pain and mental anguish - $0; past physical impairment - $1,000; future physical impairment - $0. In addition, the jury found no gross negligence.

Tifanny Nicole Cook v. Texas Tow Boys, LLC and John Daniel Vasquez

Cause No.: D-1-GN-23-006930

Judge: Maya Guerra Gamble

Dates: August 18-21, 2025

Attorneys:

Plaintiff: Ernesto Sigmon, Thomas J. Henry Law (San Antonio)

Defendants: Scott Talbot, Hanna & Plautt, LLP (Austin)

Summary: On or around July 8, Plaintiff claims that she was pushed into a third vehicle when she was rear-ended by the defendant, Vasquez, who was driving in the course and scope of employment with Defendant Texas Tow Boys, LLC. The defendant, John Daniel Vasquez, was found negligent and 11 jurors awarded: past physical pain and mental anguish - $50,000; future physical pain and mental anguish - $0; past medical care expenses - $43,598.94; past physical impairment - $10,000; future physical impairment - $0.

Lovely Johnson and Wendell Mackey v. Jeanne Namosoma and Jean Kirahura

Cause No.: D-1-GN-23-003213

Judge: Daniella Deseta Lyttle

Dates: August 18-22, 2025

Attorneys:

Plaintiffs: Martin B. Martinez, Thomas J. Henry Law (San Antonio)

Defendants: Chanel Glasper, Skelton & Woody, PLLC (Austin)

Summary: The lawsuit claimed that Plaintiff Johnson was driving in Comal County, Texas, and Plaintiff, Mackey, was a passenger when they had a tire blow out.

As they were waiting for a tow truck, the plaintiffs claim that the defendant negligently failed to keep a proper lookout and hit the right side of the plaintiffs’ vehicle. Eleven jurors found that Defendant Namosoma 25 percent and Plaintiff Johnson 75 percent negligent.

Ryan Willis v. Rainier Management Ltd and Baustin Oak Park Ltd.

Cause No.: D-1-GN-22-003413

Judge: Jan Soifer

Dates: August 19–28, 2025

Attorneys: Plaintiff: Sally Metcalfe, Joe

Caputo and Matt Breland (Austin)

Defendants: David Chamberlain, Scott Taylor, and Alex Ciechanowicz, Chamberlain/McHaney (Austin)

Summary: Plaintiff sued apartment management company Rainier Management Ltd. and landowner Baustin Oak Park Ltd. because a tree fell on him as he was walking on a pedestrian pathway. Plaintiff stated his back was broken in four places, requiring emergency surgery and insertion of two rods and 12 screws. Defendants claimed that

the plaintiff was a trespasser, and the tree fell because of the weather (act of God). Eleven jurors found that the plaintiff was an invitee and found Ranier 85 percent and Baustin 15 percent responsible. The jury awarded damages: past Physical pain$275,000; future physical pain$1,650,000; past mental anguish - $47,520; future mental anguish - $0; past reasonable necessary medical expenses - $165,000; future reasonable necessary medical expenses - $393,121; past disfigurement - $38,000; future disfigurement - $0; past physical impairment - $337,260; future physical impairment - $2.4 million; no gross negligence was awarded.

CRIMINAL

State Of Texas v. Antonio Lopez Elizalde

Cause No.: D-1-DC-25-904057

Judge: Selena Alvarenga

Dates: August 4-7, 2025

Attorneys:

State of Texas: Jacob Salinas/ Jordan Ninh

Defendant: Raymond Espersen

Summary: The defendant was accused of continuous sexual abuse of a child under 14. The jury found the defendant guilty and sentenced him to 50 years in prison.

State of Texas v. Timothy Embody Cause No.: D-1-DC-22-100036

Judge: Dana Blazey Dates: August 25-28, 2025

Attorneys: State of Texas: Jacques Roussel Defendant: Lindsey Richards, Cofer & Connelly, PLLC (Austin) Summary: The Defendant was indicted for sexual assault, which occurred on or about July 2021. A mistrial was declared after an Allen charge was issued to the jury. The State has filed and the Court granted an Amended Indictment. AL

The beauty of mediation is that it gets people out of conflict so they can move on with their lives.

— Kim Taylor, CEO and President, JAMS

Did you know that AYLA used to plan monthly community service and volunteer opportunities prior to 2020? Obviously, something happened. While the needs and opportunities have not decreased, the interest and support has most definitely. Speaking and working with executive directors and boards, it is no secret that volunteer and interest in service have decreased in the past years. There are obvious factors and global events that probably shifted mindsets and availability. Instead of focusing on what happened, I’d like to discuss the importance of service as advocates, and the positive impact it has not only on the organizations that are being supported, but also on the individuals taking the time to serve others.

The Personal Benefits of Volunteering and Community Service

Adding one more thing to your plate may be the last thing you want to do. However. I’d like readers to consider the benefits of volunteering, which include things like easing some of the stress, connecting with others, and growing. Personally, I’ve always been drawn to public service and volunteering. I love doing it because it makes me feel good to help other people. I’ve observed it starts at a young age, as my toddlers are very interested in being helpers with everything. Without getting too far into the scientific details, there is some connection between volunteering and a sense of purpose, reduced stress, and increased overall happiness.