BY NANCY BRUNNING

PACK

Acacia O’Connor

EDUCATION

Compiled by

Contributions by Acacia O’Connor and Anna Richardson

2 – 20 MAY 2023

ABOUT THE PLAY

The phenomenal women of Witi Ihimaera’s writing, including The Parihaka Woman, The Matriarch and Pounamu Pounamu, take focus and lead us powerfully through the universe of Rongopai (the wharenui at Waituhi) to reveal that which lies deep behind the veil of a world we think we know and occupy.

AUCKLAND THEATRE COMPANY & HĀPAI PRODUCTIONS PRESENT

CAST

Roimata Fox

Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu

Awhina-Rose Henare Ashby

Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine

Pehia King

Shetland Islands, Ngāti Mahuta ki te Hauāuru, Ngāti Maniapoto

Olivia Violet Robinson-Falconer

Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Te Wairoa

CREATIVE

Playwright — Nancy Brunning

Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāi Tūhoe

Directors — Ngapaki Moetara

Waikato, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Whanaunga, Ngāti Ruanui & Teina Moetara

Rongowhakaata, Ngāpuhi

Hāpai Productions Producer —

Tanea Heke

Ngāpuhi nui tonu, Ngāti Rangi, Te Uri Taniwha, Ngāti Hineira

Hāpai Productions Associate Producer

— Ash Moor

Ngāti Awa, Te Ātiawa, Ngāi Tūhoe

Set Designer — Penny Fitt

Costume Designer — Sandra Tupu

Lighting Designer — William Smith

Sound Designer — Tyna Keelan

Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Te Aupōuri

Video Designer — Delainy Kennedy

Wardrobe Assistant — Nina Douglas

TIRA

Maramaria Ki-Tihirahi Moetara

Rongowhakaata, Waikato, Ngāpuhi

Pepi-ria Moetara-Pokai

Rongowhakaata, Ngāti Porou, Ngāpuhi, Te-Aitanga-a-Māhaki

Raiha Moetara

Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti Matawai Hanatia Winiata

Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Whakaue

PRODUCTION

Production Management — Jamie Blackburn, Pilot Productions

William Smith, Hāpai Productions

Production Management Support — Khalid Parkar & Billie Holland, Pilot Productions

Stage Manager — Ashley Mardon

Te Arawa – Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Pākehā

Deputy Stage Manager —

Chiara Niccolini

Props Maker — Alex Martyn Ngāti Tūwharetoa

Technical Operator — Ruby van Dorp

QLab Programmer — Andrew Furness

Audio Mix Engineer — Matt Eller

Fly Technician & Mechanist — T.J. Haunui

Whakatōhea, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Rangitihi

Teaching Artists — Millie Manning

Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha & Acacia O’Connor Ngāti Porou, Tainui

Artist Liaison, Gisborne — Leo Garcia

Photographer — Andi Crown Publicity — Michelle Lafferty & Jess Karamjeet, Elephant Publicity

The world premiere of Witi’s Wāhine was at Te Tairāwhiti Arts Festival in October 2019, returning to the Festival the next year before performances at Kia Mau Festival, Auckland Writers Festival and Matariki Lighting The Beacons Festival.

This new production of Witi’s Wāhine, presented by Auckland Theatre Company and Hāpai Productions, is the second production in the Auckland Theatre Company 2023 Season.

The production is 1 hour, 20 minutes without an interval. Please remember to switch off all mobile phones and noise-emitting devices.

3

Introduction

A Whakapapa of Women

4

Witi's Wāhine is an invitation into the lives of the women in author Witi Ihimaera’s stories. Set on the East Coast reaching back to the Pākeha Wars and up to the 1980s, these wāhine are passionate, hard-working, loving, straight-up, and fierce. Their stories have been woven together by actor, director, and playwright, Nancy Brunning. Ultimately, this is her love story: a tribute that places wāhine, whenua and Māori wisdom centre stage.

Many of the characters in Witi Ihimaera's books, and in this play, are based off Witi’s real-life sisters, nannies, and aunties. Characters from Whale Rider, The Parihaka Woman, Game of Cards and Bulibasha are as familiar as the women in our own lives.

The actors, Olivia, Pehia, AwhinaRose, Roimata, Matawai, Raihana, Pepiria and Maramaria, guide us through a rich and contrasting world on our atamira: sometimes they laugh and play, other times the kupu are heavy in their mouths. But they always speak with love for the women who walked this whenua before us.

– Witi Ihimaera

“They are not mine at all; they are everyone’s. And they share one thing in common: protecting, nurturing and looking after the iwi, whānau and hapū during changing times, no matter what.”

5

A Summary of the Show

Witi's Wāhine is a cleverly ordered compilation of stories, and we have summarised each scene to awaken your memory of each moment.

The Māori kupu in capital letters are steps in the process of being welcomed onto an East Coast marae.

6

WAHAROA (THE GATE)

Scene 1: The Whale

The scene is set with four wāhine standing on the apron of the stage. They are dressed in striking red, yellow, green and blue - the colours used in the paintings at Rongopai Marae. Two streams of light on the closed curtain behind them represent the whare we will shortly be entering. A Pīwakawaka, representing both a tīpuna (ancestor) and mokopuna runs through the audience. Her Nanny begins to narrate and we hear a heart-beat; the whare is alive and it holds the stories of everyone who has ever inhabited it.

The whale and the ancient wisdom are dying, our Nanny says. “No wai te he?” the youngest asksWho is responsible?

7

MATATAKI (MEETING)

Scene 2: Introduction

No answers are given to Nanny’s question, instead the cast sing a karanga, then break the fourth-wall; they are Olivia Violet RobinsonFalconer, Pehia King, Roimata Fox and Awhina-Rose Henare Ashby. They tell us clearly why they’re here, and that the first story they told us is from The Whale Rider. They introduce Nancy Brunning and the reason she wrote this show.

‘The film industry is way too patriarchal,’ Roimata pronounces.

‘Perhaps in society today, women still have to prove our worth?’ Olivia challenges.

‘We are not here to hate on men by the way, or diminish their mana.’ Roimata clarifies. ‘But, we do want to set things right. For everything in Te Ao Māori is relative and this is what maintains balance.’

The women acknowledge us and invite us to hold our Nannies, Mothers, Sisters and Daughters close so we might honour them all.

8

KARANGA (CALL)

Scene 3: A Once Upon A Time Story

And then we go back to the whimsical world of Witi’s childhood, when he was nine and wrote about his sisters being dragons who marry princesses.

WHAKATAU (SETTLING)

Scene 4: Waituhi part 1

We hear the voices of the Tira, (Ensemble) singing The Call of Waituhi, the cast join in, harmonising together though physically distanced.

You call… to your people… come

To your people…

To your sacred home…

We have come, we are with you today, to remember

To answer the call of Waituhi

‘Witi Ihimaera Stories are heart stories, and if you ever had to see what his heart looked like, all you have to do is go to Rongopai.’

9

WHAIKŌRERO (WORDS ARE SPOKEN)

Scene 5: Mana Wāhine (Bulibasha)

The cast throw on gumboots and we’re cutting scrub with the tireless mana wāhine of Bulibasha. They sweat in the rain for weeks and it is with joy that they are able to burn the cuttings and watch it all go up in flames.

10

WAIATA/HONGI/URU

KI TE WHARE (SONGS, HONGI AND ENTERING THE MEETING HOUSE)

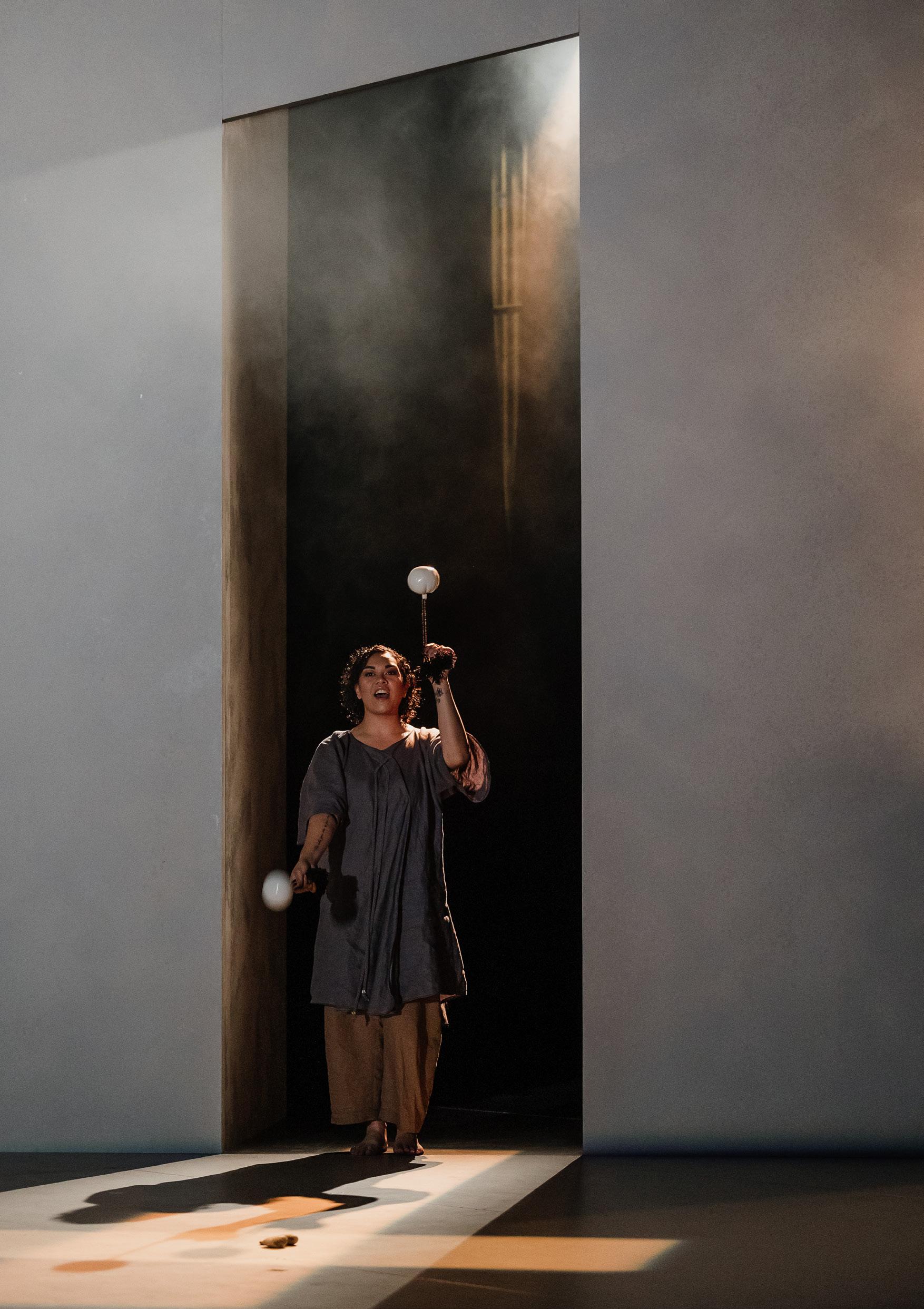

Scene 6: AV Sequence

An AV sequence begins with fire sparks and ends with bees, and a full image across the stage of Nancy Brunning as a kaikāranga as filmed on Mahana. Through her karanga, a small door appears, followed by a reveal of the rest of the stage.

The cast place a novel and four river stones at each doorway, they then face the audience and complete the Haka Pōwhiri.

11

PEPEHA (WHO WE ARE ANCESTRALLY)

Scene 7: The Sister

Awhina reads from Ask the Posts of the House by Witi Ihimaera, where an old woman remembers dancing with her handsome brother before he left for war. She makes an impossible journey to Sfax to lay white river stones at his grave.

The scene ends with Olivia kneeling by a cross of light on the floor.

‘Never forgotten, your sister, Aroha.’

12

Scene 8: Te Matua, Miro and Tama

Nanny Miro, an older woman carrying the weight of her iwi on her shoulders graces the stage next. Miro shares the gratitude and pain of loving a man twenty years younger than herself in a brave monologue performed by Pehia.

13

The relationship between wāhine and tāne turns to personal politics as Riripeti, a woman at war with herself, stands up to a room of men and shows them where they came from.

14

Scene 9: Riripeti and the Politicians

WHARE KŌRERO (CONVERSATIONS INSIDE THE MEETING HOUSE)

Scene 10: Nanny Miro

The stories of card-players Nanny Miro and Maka Teko Bum have us laughing and crying. The stage is alive as Olivia and Pehia play them as their best selves, cackling and boogying as they cheat. Awhina wins our hearts as the dying Nanny Miro messing with her mokopuna.

15

Scene 11: The Child (Nanny Putiputi)

Based on Witi’s real nanny who had dementia, Roimata embodies a woman who has lived a full life and now wants to play ‘Where’s my Rahu’ and go to the sea with her grandchild. It’s a rollercoaster of a scene, flicking between pain and play. The crashing waves grow louder and she loses her hold on this physical world. Death, in the form of a young girl visits her and leads her to Hawaiiki.

16

Te Ao Wairua

POUTUARONGO

Scene 12: The Dream Swimmer

The waves get louder, lightning flashes across the stage, Tiana’s children watch on as her feet paddle and her nightmare pulls us closer to the heart of the matter.

Scene 13: The Warrior

We are reaching the climax. Awhina, the dreaming mother is levitating and calls out a powerful, ominous cry;

‘Ko te tangata he toa, Ko te wāhine he toa!’

The man is the warrior, so too is the woman a warrior.

With the scene, we are transported to Waituhi, to experience the violence of the Pākehā wars.

17

POUTOKOMANAWA

Scene 14: The Call of Waituhi, Part 2

As we are reeling, the cast gently soothe our emotions with a reprise of Call of Waituhi. We are given time to breathe and let our feelings settle.

Scene 15: The Progenitor

And if your heart is open and you are listening, you will hear the wero. Miro had an implicit contract with her past, she knew when her time was up her ancestors would ask these hard questions:

‘Under your custodial care Matua, have the iwi prospered?

‘Have your hands nurtured the seed planted at Raiatea?

‘Have you assured their future by anointing a successor to look after them when you have passed through the vale of tears to join us?’

If your heart is open, you will know your tīpuna will ask you similar questions. You too have a long line of tīpuna to whom you are accountable.

Scene 16: The Hockey Coach

The makers of the show won’t leave you in this heavy state: Miro was also a crack-up terrifying hockey coach!

18

POU TĀHU

Scene 17: The Last Spear

The cast lift us up and share the gifts of The Whale Rider. They show us the last spear he threw, 1150 years into the future, to help his people when they would need it most.

Scene 18: Song

Each of the cast take two white river stones and leave us with a final waiata. The song is fluid, gentle and whimsical, and a waiata that was much beloved by Witi’s family. It is the final piece of medicine this show is offering you. Breathe it in.

19

How the Show was Made

Witi's Wāhine premiered at the Tairawhiti Arts Festival in 2019, the whenua where the stories originate from. Nancy herself directed the first iteration. She was sick at the time but was described as fierce as an eagle as she brought this art-piece to life.

The mantle has been passed to Ngapaki Moetara (Waikato, Ngāti whānaunga, Ngāti Ruanui) and her husband Teina (Rongowhakata, Ngapuhi) to direct this iteration. Ngapaki performed in the original performance so brings embodied knowledge of what she’s asking of the actors today.

This company started rehearsals in Tūranganui-a-Kiwa in early April to ground the words in authenticity. Ngapaki explains; “We felt that it

was actually important that we ground the design team, the crew and the cast in the whenua here knowing that these stories are based on real people.”

Rehearsals in Tāmaki Makaurau started two weeks later and producer Tanea Heke spoke for Hāpai Productions and Jonathan Bielski spoke for Auckland Theatre Company.

Rehearsals were rigorous, playful and meaningful. Every artist is involved because they believe in the kaupapa of the show. Every character, scene, shape made on stage, lighting state and sound effect is purposeful. Witi's Wāhine is designed to invite you on a journey into our whare, into our hearts, and back out, changed.

21

Nancy Brunning

Nancy is dearly loved by many of the people working on Witi's Wāhine and many artists around Aotearoa. Sadly, she left us in 2019. Nancy was a prolific actor, director, and writer who won awards in film and television and made major contributions to the growth of Māori in the arts. Nancy graduated from Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School in 1991 and worked across film, theatre and television right up until the year she passed.

Nancy is known by many New Zealanders for her role as Jaki Manu on Shortland Street but if you want to get to know her artistically we urge you to look to her more independent and Māori-based works. Her credits include Mahana, directed by Lee Tamahori and based on the novel Bulibasha by Witi Ihimaera.

Nancy and Witi met when she was seventeen in the 1980’s. Her school was putting on a production of Whale Rider, Nancy wore a grey wig and had painted on wrinkles. Witi maintains that she will always be his first Nanny Flowers.

Alongside fellow actor, theatremaker and educator Tanea Heke, Nancy formed Hāpai Productions in 2013 with a vision to "produce mana enhancing Māori Theatre productions whilst upholding Māori Values.”

For her, Witi's Wāhine lays down a wero to other storytellers to write female characters with more depth and complexity that can be role models for future generations.

“I want to show women with history who aren't one-dimensional but who have character and influence. They are the types of people I am interested in.”

22

Witi Ihimaera

Witi grew up in Waituhi on the East Coast where Rongopai Marae is nestled. He began writing at a young age, sometimes even on his bedroom wall. Witi felt the pull to take writing more seriously at fifteen when he realised that Māori never featured in the books he read. His teacher had instructed his class to read the short story The Whare by Pākehā writer Douglas Stewart, about a young man who encounters a Māori settlement. He found the story "so poisonous"

that he threw the book out of the window and was caned for doing so. Writing about the incident in his 2014 memoir Māori Boy, he said:

“My ambition to be a writer was voiced that day. I said to myself that I was going to write a book about Māori people, not just because it had to be done but because I needed to unpoison the stories already written about Māori; and it would be taught in every school in New Zealand, whether they wanted it or not.”

Witi became the first Māori published novelist in 1972 and continues to inspire Māori artists and storytellers to this day.

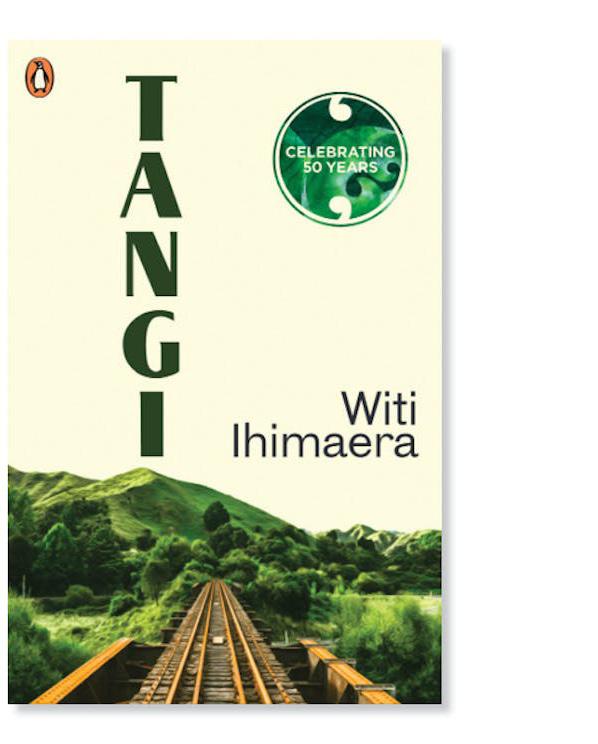

This year is the 50 year anniversary of his pukapuka Tangi and as part of the celebration, Tangi alongside a few other pukapuka are being translated into te reo.

Witi’s final dream is to write a book in te reo himself. He has applied to a full-immersion te reo programme for 2024 to claim back the taonga of his reo.

“If you ever had to see what my heart looked like all you had to do was come to Rongopai.”

23

24

Witi’s interview for Auckland Theatre Company

All of the women in my work are always women who are wanting to change the world. And through them, as a writer, that was my destiny.

I like to think that what I do is called writing for the tribe. And I like to think that my books are books that you can hongi with and when people read my books and they hongi with my books they are sharing their breath not with me but with those women. So the inspiration comes from the fact that they have breathed into me and now I am able to breathe out… them, in all of their joy and their gory and their splendour.

My favourite part has always been the sequence from The Matriarch. When the actress playing Riripeti takes to the stage you are not just seeing her whakapapa from real people but you are also seeing her mythology from the Atua. They can’t help being these strong women, they’ve had to fight all their lives for justice, for equity, for equality. I’m just so fortunate that I was able to witness my times, that I was able to come out of this valley to do this work to ensure that they kept on saying what they wanted to say through the novels, through the plays, through the screenplays that have been made. I’ve been a very very exceptionally blessed writer in that respect.

25

Director's Vision

Ngapaki Moetara’s interview for Radio New Zealand

How did you become involved in this?

Back in 2018, I was asked by Nancy to see if I would come on board as an actor. I live in Manutuke and with all the pūrākau pakiwaitara coming from there, she asked if I’d be involved with it. It was the first iteration of it at the Tairāwhiti Arts Festival. I was just ‘mīharo rawa atu.’ She's one of the prolific mentors, creative artists and I felt really humbled to be asked by her.

We miss her a lot eh?

I te wā e i mōhio au, e māuiui ana. Yeah, of course there's sadness, a pōuritanga. For me as a person who’s looked at different examples in our ao

whakaari and felt different people’s work, he tipua ia, he taniwha hoki. She was the one that I saw first on the pouakawhakaata, it means so much to have your own face and spirit represented. I think it’s no small thing she achieved, stood for and represented. Definitely missed. Definitely someone who is very distinctive in what we were doing because she wouldn’t take what was on offer for Māori in this artform. Often the roles, especially when I first came out of drama school our roles for wāhine Māori were supporting roles and we just weren’t treated the same because we weren’t cast in those lead roles. And she was brave enough to start speaking about those things and from that comes change.

26

How do you implement authenticity?

To me, the authenticity part is ‘I am here, I am present, I am awake while I’m saying these lines.’ Some actors go behind the words and don’t understand what I call the inner bowels and don’t know their intention and why they’re saying what they’re saying, it’s just a thin layer. And so to me the authentic part in a process has to be spending the time embodying their intention.

How do your kapa haka skillsets transfer to theatre?

I was just talking to Matawai and Raiha this morning and going, ‘You know you fullas can keep using the ways that you enter so boldly on the stage in hakas in here because it’s a big stage we’re going on. It will swallow you if your presence is too small. I think when I was learning about theatre, composition is an important piece but I think the level at which hakas deals with composition is phenomenal, because it’s dealing with spirit, wairua as well, it’s not just looking at shapes and forms that don’t mean anything.

Why do you do this?

I think there's so much deficit thinking in our storytelling spaces. I think it’s time to start looking at our stories as having real vital energy inside them, ahakoa ngā peke me ngā heke i roto i te hītori o ētahi.

No matter what’s happened in our history, there’s actually a rongoā inside there. And I think for me that’s probably more of a political thing to start turning around the way that we’re approaching our stories. We’re not victims of circumstance, you’ll see it in our show, our tīpuna, you know, tragic things happened but I don’t think they died tragically. I think they died with mana and that’s what I think goes missing a lot from a lot of the Māori content that I see. The aspect of, the mana, the integrity that our people had you know, he rongoā tērā mo tātou i tēnei rā i ēnei wā.

What will it be like for you when Witi comes in to see the work?

I don’t want this to sound funny but, the way I look at it is if I stand in my own knowing of the purpose of what I’m doing. That has to take precedence. I’m not there serving anyone else's agenda. Not even Nancy. And I feel that Nancy held that too, she did things on her own terms. So my orientation to when Matua Witi comes and sees it is just ‘I just can’t wait for him to see the delicious work we’ve been cooking up. To serve it with love.’

27

Designer’s Vision

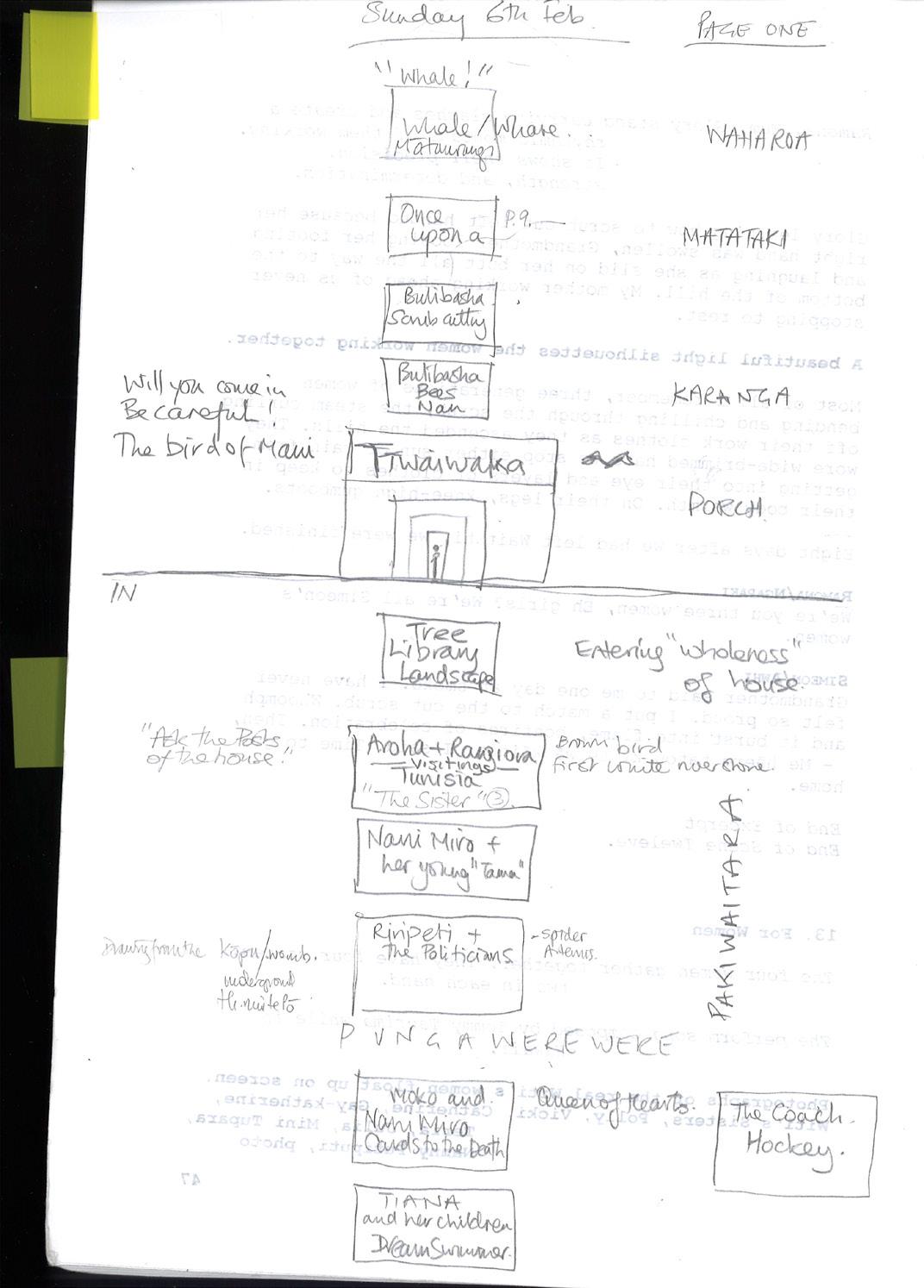

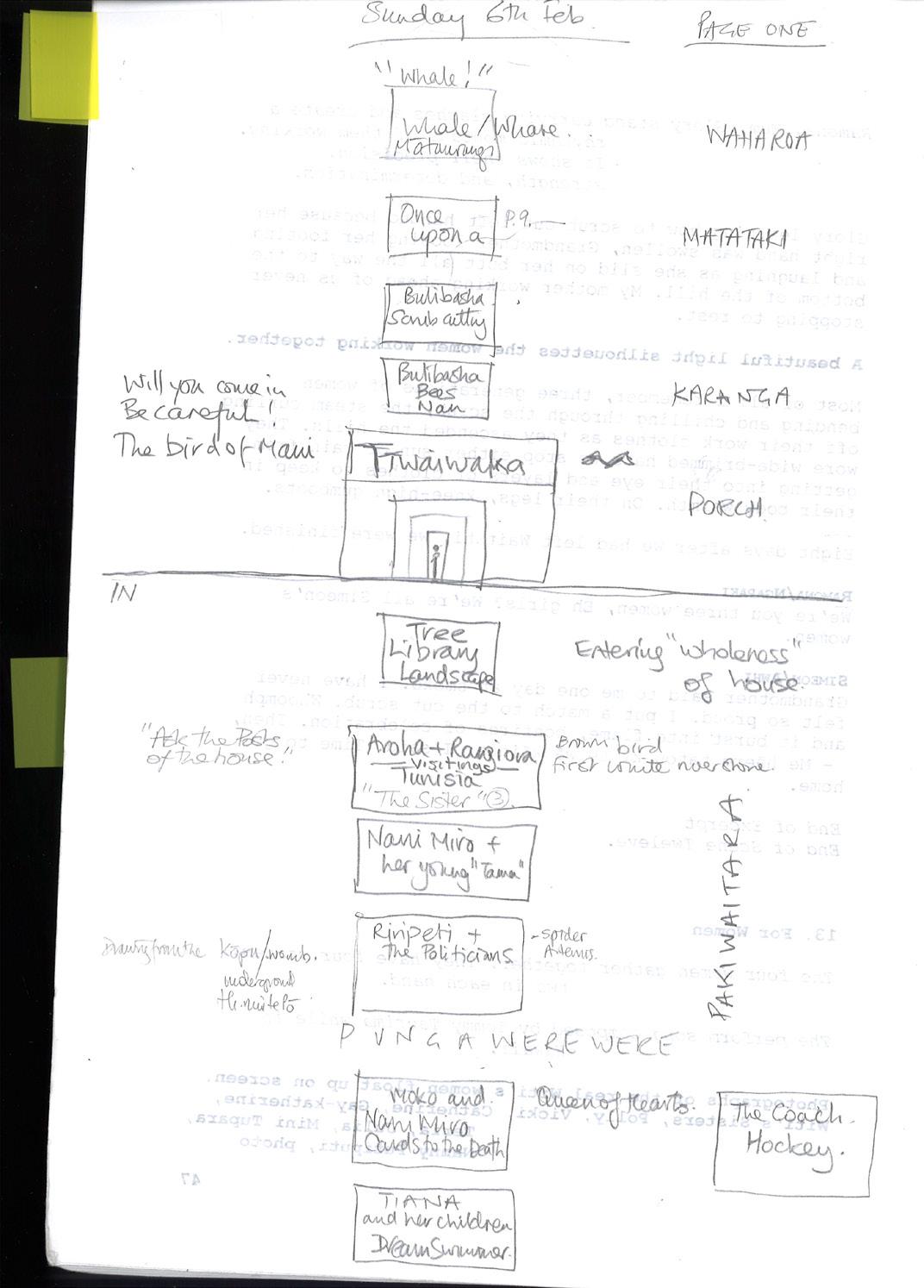

WITI'S WĀHINE SET DESIGN PROCESS:

We wanted to make our own sense of the way the play had been put together from all Witi’s stories.

Witi Ihimaera writes stories about growing up in the 50s through to the 80s, and Witi's Wāhine takes the female characters who are strongly described, but never central to Witi’s stories, and makes them the main focus instead of the the male characters.

In the play, you get a sense of an Auntie or matriarchal figure through extracts and snippets from Witi’s stories. Our job was to make sense of the order of these pieces and get from one bit to the next. That’s one thing design can do: help transition from one place to another, from one mood to another and from one story to another.

28

29

THE JOB OF A DESIGNER:

Often a script won’t give you clues about space. You might get hints about setting or location, but there's not always an indication about the space that the audience and the actors share together. So, a job of set design is to work out the relationship: to make actors moving around a space meaningful to the audience watching.

Audiences make meaning naturally, but set design can enhance meaning by designing shapes and forms to help to lead us through the story.

PENNY’S PROCESS:

I made a model of the theatre space, the ASB Waterfront Theatre, and then the directors and I played with how we might set certain scenes.

When I go into the theatre for the first time, I walk around the stage and work out where I would most like to stand, facing the auditorium. There's usually a “sweet spot” that an actor can sense. I ask myself: “where is it nice to stand?”

The second layer is once actors come in from a certain place on the stage the audience start to map locations. So another part of the set designers job is to track the traffic that's coming through and see all the ways you can use it.

30

THE DESIGN

It's quite a simple set that is based on a wharenui, a meeting house. The directors and I want to create an event for an audience where we very gently take the audience onto a marae, into the wharenui, and invite them to look at all the stories on the wharenui walls.

31

THE SPACE

At the beginning of the piece, during the introduction and the initial story, the actors are performing in front of the theatre curtain and the audience is quite well lit. The show starts by meeting the audiences and bringing them in. We're suggesting that downstage is the marae ātea, the open area in front of the wharenui, at the apron of the stage.

Then we do a fancy trick of opening the door, which opens up to reveal more of the set, and we begin telling more of Witi’s stories.

There are pou that hold up the meeting house. At the very back of the meeting house is the pou tuarongo which connects into whakapapa and the spirit world. The pou in the middle is the pou tokomanawa, which connects to heart and relationships, and the pou at the far end, where we usually arrive and leave, is the pou tahu.

We’ve used this shape to bring people into the wharenui, through, and back out again. This organises all the scenes and conveys their purpose for both the actors and the set design. It's important for me as the designer to know which elements we want to use. I chose not to have representations of carvings or tukutuku panels because I want to encourage the audience to imagine themselves into this space. My hope is that audiences feel being invited in and getting further and further into the world of Witi's Wāhine.

The other thing this set design does is put walls behind the actors, supporting them and funnelling the action out into the space, directing their energy into the audience and helping them to feel that they’ve got the audience in their grasp.

32

THE DOORWAYS

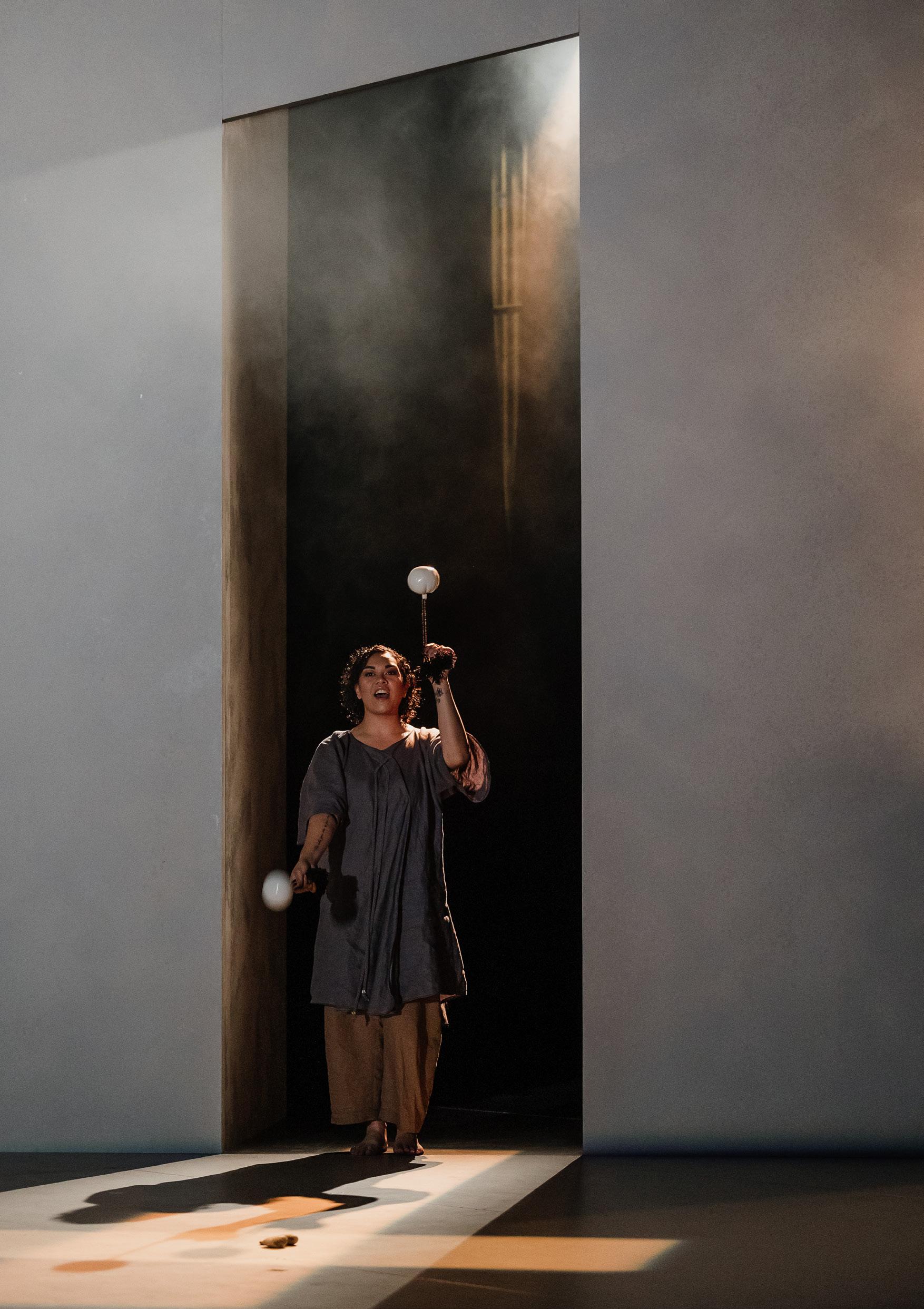

The doorways are where the stories from the past come from; there's a kind of sacredness in that space and beyond, the space of spirit or of ancestors. The actors can't go in and out of those doors because they'll appear to come in and out of life. But we've got a tira, a chorus who come from these spaces, bringing characters and memories to life.

33

Costume Vision

34

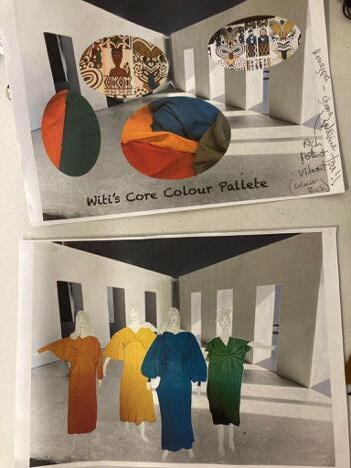

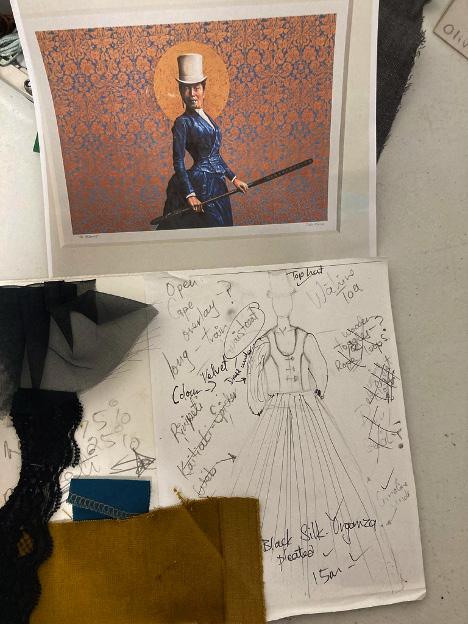

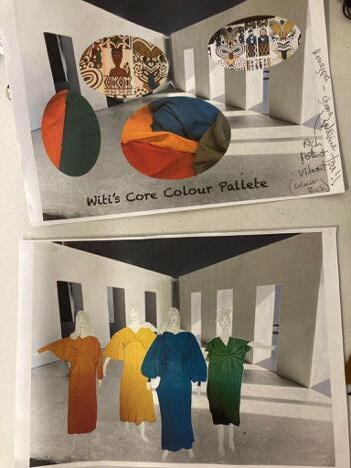

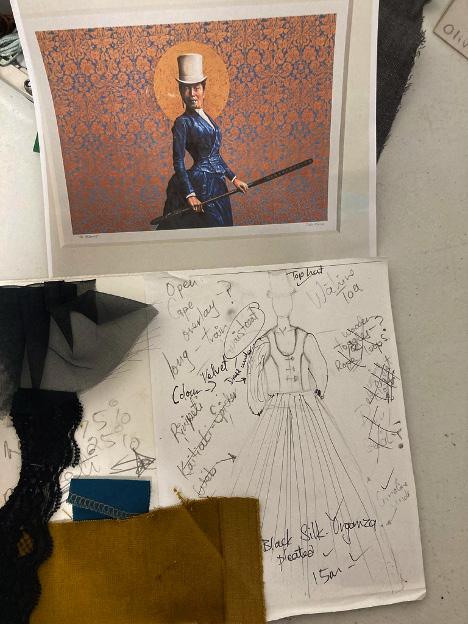

Everytime Sandra Tupu designs costumes, she spends a long time researching. For Witi's Wāhine, she read all of Witi’s books, watched documentaries on NZ on Screen, observed Māori carvings and paintings and learned from Ngapaki and Teina. From there, she contemplates which images are sticking with her and asks herself ‘what do I want to take from all that research?’

What stood out for her when designing Witi's Wāhine was the spiritual world and the space in between. Eventually, she condensed her ideas down to the manu messengers and whales that appear thematically throughout the piece.

After landing on her theme, Sandra cut out the shape of a whale fluke in cloth and figured out how to make that the central part of each costume. Each actor has the fluke of the whale somewhere different in their garment. For example, in Olivia’s green garment the whale flukes are upside down and over her back.

The colours of the costumes are inspired by colourful paintings done by hundreds of young artists from the 1860’s who were optimistic about a ‘brave new world’ of peace between Māori and Pākeha.

Sandra wanted the costumes to pack a punch and represent wāhine toa and the different facets of wāhine.

35

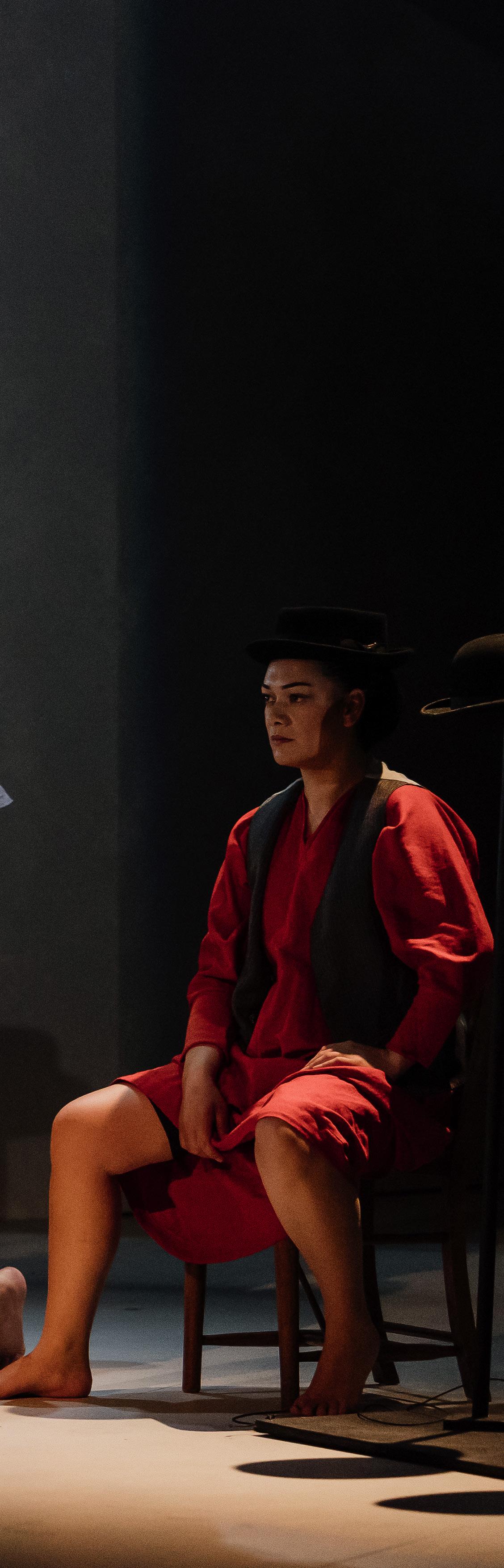

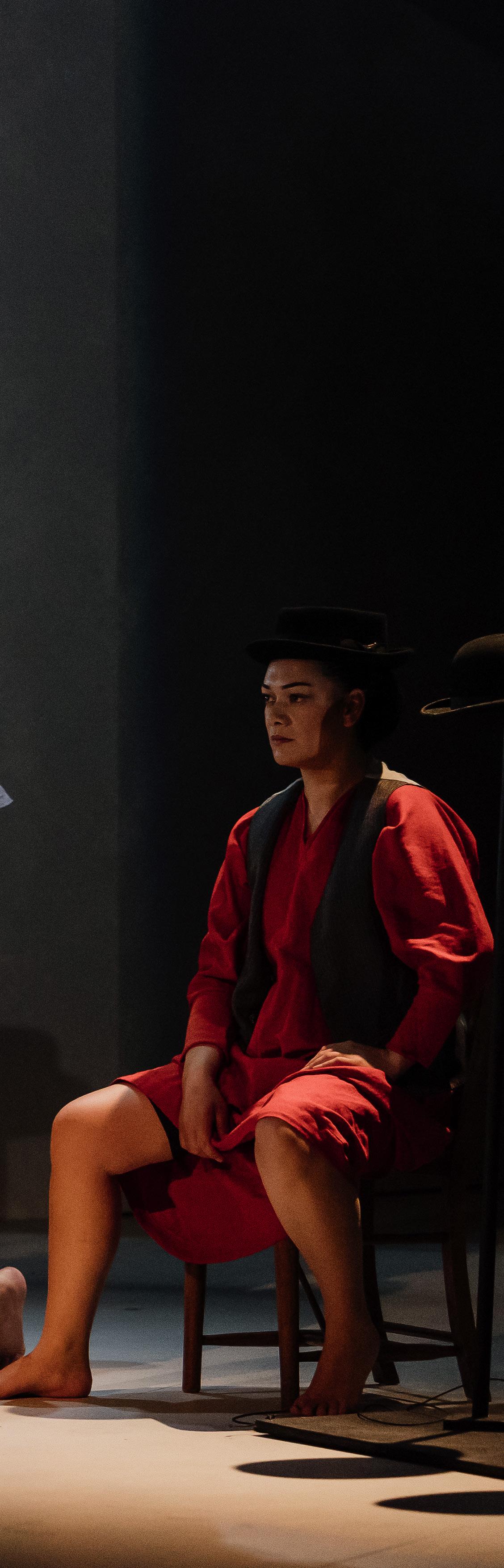

Ngapaki and Teina connected the colours to the actors and the different pou that they all hold:

Pou āwha: Dark blue.

Roimata Fox: Her characters are Riripeti, Nanny Putiputi and Tilly with her card-playing grandmother. She represents an outward expression of mana and austerity.

Pou tahu: Golden Yellow.

Pehia King: Her characters are Miro in her monologue, Nanny Miro playing cards and smoking, Narrator and Simeon. She represents playfulness and wāhinetanga.

Poutokomanawa: Green.

Olivia Falconer-King: Her characters are The sister Aroha, The Narrator in Riripeti’s scene, The Mokopuna with her grandma at the sea and the hockey coach. She represents the range of humanity, heart and relationships.

Poutūārongo: Red.

Awhina-Rose Henare Ashby: Kaumatua, Tiana the dream swimmer, and Tiri. She represents whenua, context and groundedness

The Tira colours were taken from the back tukutuku panels of the Rongopai wharenui which are muted, earthy and hang alongside photographs of tīpuna. These four colours represent the link between Te Ao Mārama and Te Pō. Sandra wanted the costumes of the Tira to move like a piupiu in haka and fight.

All of Sandra’s costumes are made of recycled and self-dyed materials. She prints with natural materials instead of ink.

The silk capes that appear in the warrior scene are recycled silk curtains printed with pūriri trees and jet-black paru from the whenua at Rongopai. To make the silk capes, Sandy bundled up the garment and boiled the leaves over an outdoor fire for an hour. With no-one watching her, Sandra threw the garment into the boiling water, imagining the battles and explosions and feeling like she was at war.

Sandra teaches design at AUT and is taking Fashion Design into a more sustainable future.

36

37

Cut out whale flukes that would the basis of every costume piece.

Carvings by Rex Homon

Left: Photos taken inside Rongopai Marae

Right: The fabrics that were then found to make the costumes of the four leads.

This painting by Ngati Porou artist, Sofia Minson: The Navigators

Left: Photos taken inside Rongopai Marae

Right: The fabrics that were then found to make the costumes of the four leads.

This painting by Ngati Porou artist, Sofia Minson: The Navigators

38

This was part of the trial and error process. Sandra experimented with dirtying doilies to then print on to the white silk, representing colonisation and the mess that ensued. The idea was scrapped because it wasn’t visible from the audience but could be beautiful if this show ever becomes a film.

that inspired Sandra.

make piece.

would

39

Cast

ROIMATA FOX

Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu Roimata Fox was born and raised on the East Coast. She moved to Auckland at the age of 19 to study film for a year and is blessed that she is still working today.

Theatre highlights:

Purapurawhetū, The Māori Troilus and CressidaToroihi rāua ko Kāhira, Much Ado About Nothing, Witi’s Wāhine and The Haka Party Incident.

Screen highlights:

Waru (2017), Muru (2020), and television series Head High (2021). Also, she had the pleasure of working with Katie Wolfe in three seasons of The Ring Inz.

AWHINA-ROSE HENARE ASHBY

Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine Awhina-Rose Henare Ashby graduated from Excel School of Performing Arts in 2008 and Te Kura Toi Whakaari o Aotearoa: NZ Drama School in 2012. She has continued working in the creative industries.

Theatre highlights:

The Māori Troilus and Cressida - Toroihi rāua ko Kāhira, Party with the Aunties, Marama, The Mooncake and the Kūmara, The Vultures and Kororāreka: The Ballad of Maggie Flynn.

Screen highlights: Shortland Street, Dear Murderer, Resolve, three seasons of a Māori comedy television show The Ring Inz. Feature films: Whina, Waru, Te Pāmu Kūmara and film turned-Emmy-winning series Rūrangi.

Awhina-Rose was raised on a farm in Mōtatau, a small place in the Bay of Islands. She grew up with te reo Māori as her first language.

PEHIA KING

Shetland Islands, Ngāti Mahuta ki te Hauāuru, Ngāti Maniapoto

Pehia King was brought up in Ōtorohanga and Tahaaroa and went on to attend Te Kura o Kuīni Wikitōria. She studied at Whitireia Performing Arts (WPA) and travelled extensively, showcasing Māori and Pasifika performance. After returning to WPA in 2012 to upgrade her qualification to a degree (BAppA), she was introduced to theatre and had a new-found excitement for acting. She has since gone on to do television, Māori media and theatre work.

OLIVIA VIOLET

ROBINSON-FALCONER

Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Te Wairoa

Olivia Violet RobinsonFalconer is a theatre and screen actor with a career that spans more than 25 years. She trained at Te Kura Toi Whakaari o Aotearoa: NZ Drama School.

Theatre highlights: Ngā Pou Wāhine, When Sun and Moon Collide, Into the Woods, Blue Smoke, Ngā Tāngata Toa, Le Sud and The Motor Camp.

Screen highlights: Needles and Glass, Mataku series: Te Whakaahua and Aftershock.

When she is not acting, Olivia is helping students reach their academic goals at Te Pūkenga: New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology, in the māra, buried in a book or listening to music.

“Thank you for supporting this beautiful work. To my dear friend Nancy, thank you for choosing me. And to my son, remember sweetheart, reach for all the stars!”

40

41

Ngātapa

“Where you see one woman, you see a thousand”

The siege of Ngātapa took place between the 31st of December 1868 to the 5th of January 1869.

“Ko te tangata he toa, ko te wāhine he toa.”

The man is the warrior, so too is the woman a warrior.

Before 1860, localised conflicts began to erupt between Māori and Pākehā over disputed land settlements. By 1860 the Pākehā government became convinced they were facing united Māori resistance to Crown Sovereignty and so the wars began. To Māori, they were the Pākehā wars.

They were fought in the Waikato, the Taranaki, then the North. They came to the East Coast, 20-years after their war had begun.

Whareongaonga, 10 July 1868: Te Kooti escaped his imprisonment on the Chatham Island’s with 297 supporters. Te Kooti was to many, a prophet, founder of the Rinagtū religion, who waged guerilla warfare against the government for many years. Te Kooti likened the situation

the Māori people were facing to those of the enslaved Israelites in Egypt during biblical times.

In 1868, Te Kooti and his followers attempted a pilgrimage to Te Urewera. They ran into Major Biggs multiple times and many of his people were killed. He sent this message “Three times Biggs you have attacked me and three times I have asked you to leave us alone. You still pursue us in our pilgrimage. Therefore, I shall take my people up unto Puketapu Mountain. There I will establish my church, the Ringatū. And from there, in November, I shall fight you. This is my declaration of war for, verily, I see that you will not relent and you will not let my Israelites out of their bondage unto Egypt.”

42

9 November, 1968:

Te Kooti took his revenge on Biggs. The story was that they massacred 63-people and that some of the victims were in the church praying when they slaughtered them. But history is written by the victors and the descendents of Te Kooti’s people maintain these were lies. It was a military attack.

Christmas 1868:

Te Kooti’s people were cornered at their cliff top fortress, Ngātapa. The back of the pā was a steep cliff and there seemed to be no way out. They held strong against over 700 militia but they were running out of food, water and ammunition. With 125 slain, they knew this would be their last stand.

The evening of 4 January, 1869: Wāhine made flax ladders for Te Kooti and all his able-bodied followers to escape over the side of the cliff.

5 January, 1869:

Pākehā soldiers took the fortress in the morning. They found only the wounded: fourteen men, sixty-six women, the rest children. No mercy was shown.

In 2004, in a report on land claims in the regions, described the executions as "one of the worst abuses of law and human rights in New Zealand's colonial history."

43

Ways into Witi Ihimaera’s Works

Writing about the Māori world, both rural and urban, often knocking into the Pākehā status quo, Witi Ihimaera’s writing has always offered a broader view of what New Zealand literature could be – should be – about.

But with numerous short stories, novels, libretti, plays, memoirs – well over 20 books, plus many more he has edited or contributed to – where do you begin? Following is a sampling from Penguin Random House Fiction Publisher, Harriet Allan.

44

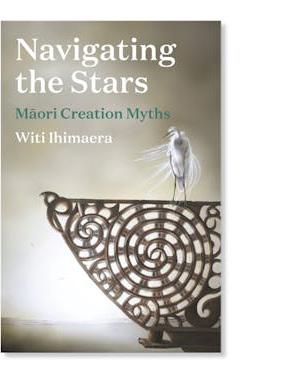

Navigating the Stars

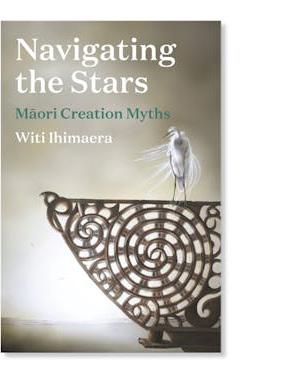

Māori mythology has had a significant impact on many of Witi Ihimaera’s works – and indeed his life. He feels he was always destined to write Navigating The Stars so this significant publication is a good way into his inspiration and world. In this book, he explores Māori creation myths, retelling the versions he was brought up with, while also considering alternative traditions and what they are telling us. He tracks the journey many of the myths have taken to reach Aotearoa from the migrations across the Pacific, and he conveys how mythology embodies our identity, history, religion and philosophy, both fact and the fantastical, celebrating our heroes and ancestors, explaining and enriching our world. You may already be familiar with the tales of Māui or the story of the separation of Rangi and Papa, but this book will reveal so much more.

Witi’s Memoirs

Witi’s memoirs not only reveal where he came from but also the source of his various books. They give a taster of many of his works and an insight into their writing, so this may well help you decide which book to jump into next. The memoirs themselves offer a poignant, revealing and fascinating read. To explain his formative years – the formative years of a Māori boy – Witi demonstrates in the prize-winning Māori Boy that you need to understand his ancestry, his whānau and his myths, just as much as the details of his individual life. Circling these rich, multiple layers, he also gives a vivid, moving and shocking account of his early experiences. One event in particular overshadows his life and, as you can go on to discover in the pages of Native Son it would continue to do so. Native Son follows Witi from the age of fifteen until he left New Zealand in his late twenties with the first of his publications being released.

45

Short stories

Pounamu Pounamu was his first publication. A collection of short stories, it drew inspiration from the valley of Waituhi and the lively array of people who were part of his upbringing. Witi’s stories offer a tremendous variety, though all are distinguished by his trademark humour, humanity and political edge. If you want more short stories – and they are as entertaining as they are informative. Then seek out His best short Stories or his most recent collection The Thrill of Falling The latter presents an array of different narratives – literally different ways into story. You might also like the hybrid book Sleeps Standing a novella based on the Battle of Ōrākau, together with a Māori translation, photographs and eyewitness reports.

Some of Witi’s stories later expanded into novels, such as Tangi, The Whale Rider and Bulibasha.

Tangi

Beginning as a short story published in 1969, then expanded and released in 1973 as Witi’s very first novel –and the first by a Māori – Tangi has recently been revisited again to mark its 50th anniversary. At the centre of the novel is the story of a father and son set within a three-day tangihanga. The novel won the James Wattie Book of the Year Award.

46

The Whale Rider

A young girl, a whale, a village under threat and an ancient myth all combine into a compelling story for adults and children alike (and there’s a te reo Māori version being re-released soon to give you a completely different way into Witi’s work). Yes, there is also the film to watch, but this is not a long novel, so if you want a quick read, this is the perfect place to start.

Bulibasha

With echoes of Shakespeare’s rival families in Romeo and Juliet, this is a Māori Western set amid shearing gangs. A grandson takes on his dominant grandfather and discovers a dark secret that concerns his beloved grandmother. This novel was made into the film Mahana.

White Lies

As mentioned, both the above novels have been made into films, as has White Lies. This publication shows that films and the books they come from can offer very different ways into the same ideas. This volume has the original short story, alongside the novella it inspired and also the screenplay for the film by Dana Rotberg. If you are interested in film-making, this book is for you, but there’s also a whole lot more, including insights into Māori medicine, moral dilemmas, the position of women and the colour of skin.

47

Nights in the Gardens of Spain

This has also been made into a film. It is a novel about coming out, a brave move for it was also a public coming out for the author. As the blurb says, the novel takes us along the precarious divide between sexuality and social mores, exploring dilemmas of contemporary gay culture with anger, laughter, sensitivity and honesty.

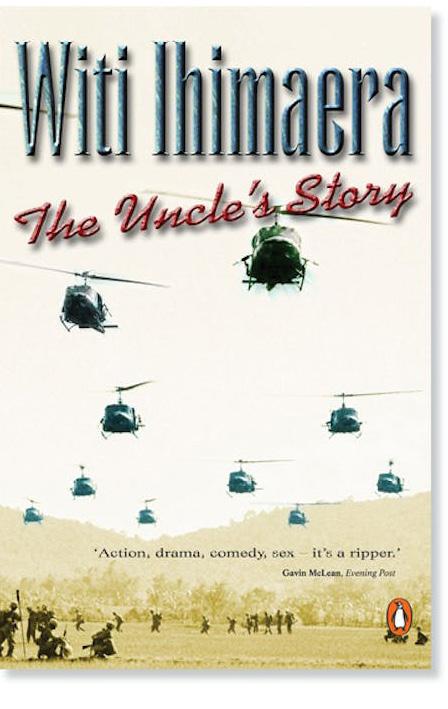

The Uncle’s Story

This is another novel about sexuality and masculinity, homing in on Māori attitudes. Set in the war-torn jungles of Vietnam and in present-day New Zealand and North America, it is also a moving love story.

The Sky Dancer

Māori mythology is never far from Witi’s work. This novel is a great example of that, being based on the Māori legend of the battle between the land birds and sea birds. Although longer, like The Whale Rider, it is a good way into Witi’s work for younger readers, while being equally appealing for adults.

48

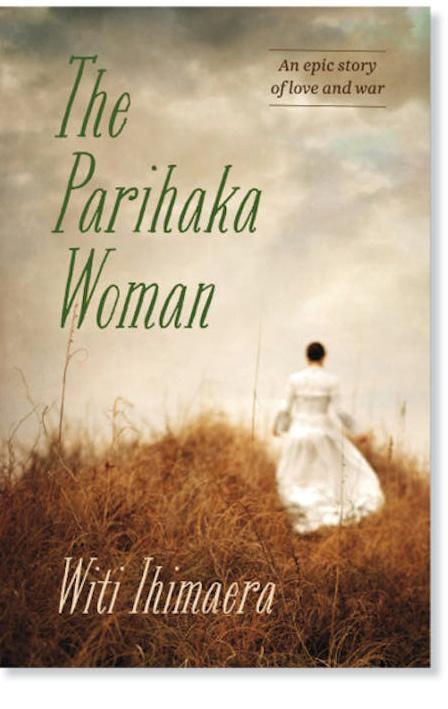

The Parihaka Woman

Witi has always been interested in Māori history, and here the fate of the pacifist Parihaka protestors forms the backbone to this novel. Witi has also long been interested in opera, and this fascinating story takes on an increasingly operatic flavour as it progresses. It’s an unexpected and inventive love story.

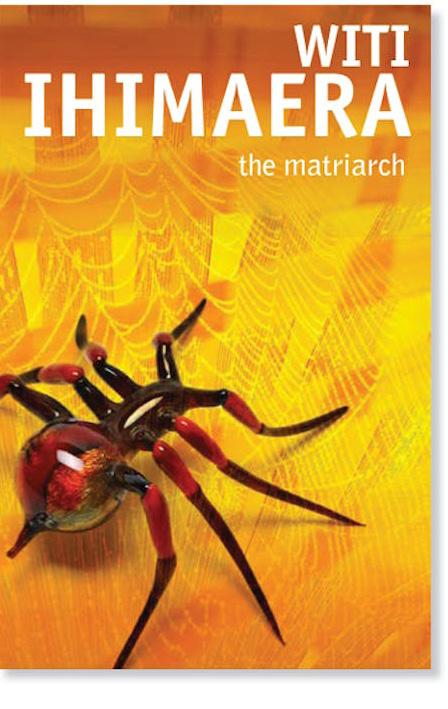

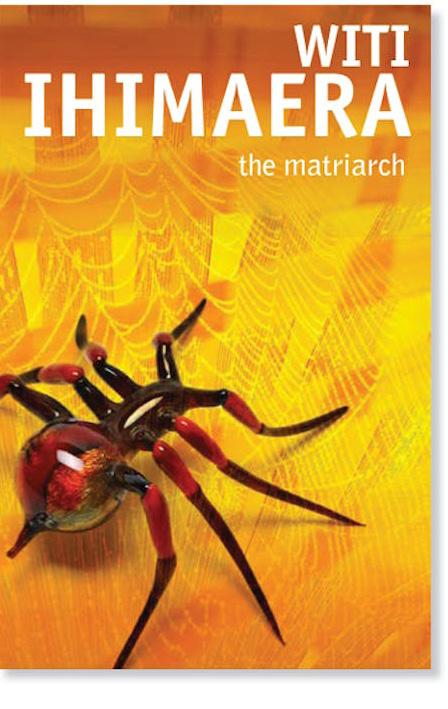

The Matriarch and The Dream Swimmer

Also showing the influence of opera, these two novels are particularly experimental, so a bit more of a challenge. Give these a go once you have some of Witi’s other works under your belt. The Dream Swimmer is the sequel to the prizewinning The Matriarch, following the journey of Tama Mahana, as he tries to understand the Matriarch, the ruthless beauty who fought for her land.

The Astromancer

If you want to introduce children to Witi’s wonderful writing then, this is a gripping picture book, which will also introduce them to Matariki. And if you want to extend your te reo Māori, there’s the translated version: To Kōkōrangi.

49

Article reprinted with permission of Penguin Random House NZ.

Final Letter from Witi Ihimaera

Ko Ōkāhuatiu te maunga, Ko Waipaoa me Repongaere ngā wai tapu

Ko Rongopai te marae, Ko Te Whānau a Kai te iwi, He uri ahau nō Teria Pere, te wahine, Tihei mauri ora

In May 2023, I am publishing two books: Tangi my first novel in a 50th Anniversary Edition, and A Kind of Shelter, an anthology of writing which I have co-edited with Michelle Elvy.

Tangi looks back to the past; A Kind of Shelter looks forward to the future. And Witi’s Wāhine is the pivot,

smack bang in the middle, from which to take a check on where I, and we, have reached in the ever-evolving story of Aotearoa New Zealand.

I began Tangi in Wellington, prior to embarking with Jane for London on our honeymoon in 1971. But the bulk of my debut novel was written in a small bedsitting room at 67 Harcourt Terrace, South Kensington, London. Every day when Jane went to work as a relief teacher in Hounslow, I sat at a small Olivetti typewriter and bashed away on it. I fiddled with carbon paper to make sure I had a duplicate copy. Between trips to France and Greece, and tours in a small minivan whizzing around England, Scotland and Wales, I kept on typing away. On returns to London, the mahi continued. Sometimes May, the housekeeper at Harcourt Terrace, would look in to see that I was not slacking on the job and Mr Way, who owned the four-storeyed building, would invite me up to his apartment for a beer.

Tangi was one of three books

I published between 1972 and 1974; guess who was a busy boy. They comprise a publishing trifecta of Pounamu Pounamu (1972), Tangi (1973) and Whānau (1974).

Image: Witi Ihimaera, circa 1974. Photo courtesy of Witi Ihimaera.

50

With these three books, I began to create what might be called the Ihimaera multiverse. I was 29 when Tangi was published, which was young at the time for a novelist, and I was very proud when the book won the Wattie Book of the Year Award (1974).

I hope you enjoy the extract from the 50th Anniversary Edition in which I have rewritten large parts of it. Some of the rewriting is seriously good; after all, I am older and wiser now and I hope I have brought maturity and richness to my craft as well as cunning.

As for A Kind of Shelter, well, it’s a product of my other literary career as an editor and anthologist: another kind of multiverse. I keep on getting the count wrong but I think I have edited at least 25 books with titles like Into the World of Light, Vision Aotearoa, Te Ao Mārama (there are five of those), Growing up

Māori, Get on the Waka, Black Marks on the White Page, Pūrākau and Navigating the Stars.

A Kind of Shelter is kind of special and I am grateful that Massey University Press has agreed to offer it to all Auckland Theatre Company theatre-goers. Seventy-six writers and artists take a look at some of the challenges that we are actually already facing. In other words, my literary career hasn’t always been just about me! Pick it up at its seriously discounted price; it’s going to be one of the books of 2023.

And my sisters and I hope you enjoy our lives as portrayed in Nancy Brunning’s brilliant play Witi’s Wāhine. They are not my sisters. I am their brother.

Ngā mihi, Witi

Image: Tangi book cover. Photo courtesy of Witi Ihimaera.

51

Exploring the Journey to Stage

When you are revising for your live performance exam, you will want to unpack what you think the Directors; Ngapaki Moetara and Teina Moetara, intended to communicate through their choices. In the case of Witi’s Wahine and its journey to the stage it is important to consider the show's whakapapa - the writer, Witi Ihimaera’s point of view, Nancy Brunning’s role and Moetara’s vision, as part of the director’s concept. These activities will help you brainstorm and collate your ideas, as well as providing evidence or quotes to support your explanations and discussions around the exam questions.

Instructions for ākonga:

Use the following reading and brainstorming activities to pull out the major themes and ideas, as well as evidence you can use for revision. You will need paper to brainstorm on or whiteboard markers, as well as your drama book or device. Remember to take photos of group work. You will need to reference:

• How the show was made - page 21

• Nancy Brunning and Witi Ihimaera’s bio’s - page 22 and 23

• Witi’s interview - page 25

• Director’s Vision - page 26 and 27

52

A GLOSSARY OF QUOTES: INDIVIDUAL ACTIVITY

In your drama book or on your device create a document called “A Glossary of Quotes.” As you read through pages 21 – 27 copy out quotes from Brunning, Ihimaera and Moetara that you think will be useful in your Live Performance exam. Make sure you note down a short statement about why you think this quote will be useful. This could be connecting the quote to a social, historical, political, or geographical idea, something that drove acting or design choices or you have a hunch it might be powerful evidence to support your ideas in the exam.

REVISION: GROUP ACTIVITY

• Choose someone in the group to read each of the sections identified above out loud.

• Write down, circle, or highlight major ideas, themes or challenges that have been laid by Brunning, Ihimaera or Moetara.

• Discuss these and flesh out mini brainstorms around the aspects you have identified. You could use these questions to guide discussion:

• What ideas or comments support the way actors have created their characters or are acting in the space?

• What aspects of personal whakapapa are Brunning, Ihimaera or Moetara bringing to this work?

• What do you find interesting or compelling about this idea?

• Why do audiences need to think about this idea?

• What challenges were laid for the audience and why were these important?

• Discuss the common themes or threads that run through all the commentary. Extend:

• Identify moments in the performance that brought these common themes or threads to life.

• Explain these moments in detail - what was physically happening on stage?

• What characters or actors embody these themes or threads?

• How does the technical design reflect these themes or threads?

53

IDEAS THAT SPEAK TO YOU: GROUP ACTIVITY

Looking at your group's brainstorm, discuss ideas, themes or challenges that jump out. Use this discussion as the provocation or stimulus to create a short, devised performance. Ensure you are using the following in the performance:

• Narration

• Dialogue

• Chorus of movement

• A moment of chorus of voice

• A strong entrance and exit

Before you perform your scene, give a short explanation of what inspired the performance and what you intend to communicate to the audience.

After you perform ask the audience the following questions:

• Was the intention for the performance clearly communicated?

• Could you see the drama conventions clearly in our performance?

• What was effective about our performance?

• What could we extend or improve on for next time?

• What could we have done to link our performance more strongly to Witi’s Wahine?

54

Exploring the Designers Concept

When you are revising for your live performance exam, you will want to unpack what you think the Designers; set, lighting, sound, costume, props, make-up, and special effects, intended to communicate through their choices. These activities will help you brainstorm and collate your ideas, as well as providing evidence or quotes to support your explanations and discussions around the exam questions.

Instructions for ākonga:

For these activities you will need to reference pages 28 – 41 of this education pack:

HOW DESIGN CHOICES HELP LINK THE STORIES:

Think about the way the narrative is structured and how the design choices are instrumental to moving the story from one moment to another. Create a timeline of the narrative either on some large craft paper, the white board or in a way that suits your class. Using the “Summary of the Show” at the front of the pack, plot the design choices and the story along a timeline. Make detailed notes using the following prompts:

• How the lighting helped transition from moment to moment

• How the set was used by the actors during transitions

• How props and pieces of costumes helped you understand which story was being told

• How sound increased tension, indicated mood or created atmosphere

• How the technology placed the audience in a distinctly Aotearoa setting

56

SYMBOLISM, SKETCHING AND ANNOTATION

Witi’s Wahine journey’s through Witi’s Ihimaera’s stories and explores the lives of the women who populate them. The set, costumes and lighting have been explicitly designed to reflect the place and time these stories were told. The way we are welcomed into the world of the play is also designed to specifically reflect a Te Ao Māori point of view and voice.

REVISION ACTIVITIES:

• Sketch the stage on three separate pieces of paper - the apron in front of the curtain, the moment the curtain opens and when we see the main set for the first time.

• Select and sketch one costume that you found compelling

• Choose a moment where lighting created an interesting or surprising effect on the set/stage or on an actor/s.

Add colour and comprehensive annotations to support your understanding of these uses of technology. Discuss their function, purpose, and symbolism. Add annotations about what the actors were doing in a specific moment in time. Especially how the actors supported the transition from one space to another and what aspects of Theatre Aotearoa were used to bring the audience into the world of the play. Ensure that you support your annotations with quotes from the designers.

57

Exploring Acting Choices

The following two activities will help you build a picture of the characters in the performance, experiment with them in a new situation and contribute to your kētē of knowledge for your live performance exam.

Instructions for ākonga:

Use the information on Page 42 of the education pack

REVISION ACTIVITY:

Create an acting profile an actor you found interesting or compelling, using the following template: (You could do this for multiple actors if you have time during revision)

Description of characters the actor played: name and the stories they come from

Costume and makeup: colour, material, what this says about the characters they play throughout the performance, how it impacted posture and movement

Relationships: who they are connected to and why

Motivations/links: what motivates or links the characters they portray?

Actors use of body, voice, movement, and space: think about what feels new, fresh and uniquely Aotearoa about the acting or performance choices.

Subtext: think about specific moments where a character was communicating through subtext.

Favourite quote:

58

PRACTICAL ACTIVITY:

Choose characters from your character profiles or who inspired you in the performance. In a group take the characters and expand their storylines OR choose a storyline or theme that you would like to explore further. Devise or improvise a short scene that didn’t happen in the play but could add more information to that character's storyline or unpack a theme. Ensure that you structure your performance using drama conventions and/or if appropriate in your classroom context, aspects of Theatre Marae.

REFLECTION: How did performing in a scene based on Witi’s Wahine impact your understanding of the play? Why is exploring ideas through performance an important or useful way to understand ideas or themes?

59

Theatre Marae

(Teaching note: you may need to support ākonga with kupu and the deeper concepts they encompass. Some pre-teaching may be needed here. Te Rakau Theatre Company and Helen Pearse-Ortene’s writing is an excellent reference when teaching Theatre Marae: Kaupapa rangahau | Research | Te Rākau Theatre (terakau.org)

When we go to live theatre, we can often see features of theatre form in the way the play is scripted, staged, directed, or performed.

Theatre Marae emerged in the 1990s when playwrights such as Jim Moriarty, John Broughton, Roma Potiki, Rangimoana Taylor, and Hone Tuwhare were carving out space in the theatrical world, to give voice to the indigenious people of Aotearoa. The practices of this form can be used as a decolonising tool within theatre, as well as in kura, prisons and within the wider community. The framework of this theatre form aims to address themes and ideas around trauma, social justice, and honour Māori perspectives in these areas, without being pushed through an exclusively western lens. It allows for western theatrical practices to be woven with te ao Māori and performance traditions. Every theatrical work comes from the point of view of the writer, creator, and director, with further collaboration with the actors and/or subjects of the writing. The point of view will be built around specific backgrounds, experiences, cultural framework and collected knowledge.

60

When thinking about how Marae Theatre is applied within a theatrical context it is important to think about how the following rituals or practices are present in performance:

• Pōwhiri, mihimihi, karanga or pepeha

• Karakia

• Whaikorero (oratory)

• Hui (gathering)

• Haka, Waiata, Poi and other aspects of Te Ao Haka

• How the structural and symbolic aspects of the Marae building influence the work. This includes the carvings, paintings and weavings that adorn the inside of a Marae. The structural design of the building, inside and out.

• The methods of passing on oral histories; myths, legends, tā moko and whakataukī

• Mauri (life force), wairua (spirit), Te Reo Māori and Tikanga

• A sense of inner landscape or voice, that speaks to what it means to be Māori and people of this land

• Giving voice to the voiceless, within the parameters of their own cultural practice.

Instructions for ākonga: for these activities reference pages 5 – 19 and 44 – 45.

REVISION ACTIVITY:

To understand Theatre Marae and how it appears or is applied within Witi’s Wahine we need to draw alignment between the structure of the show and the key features and ideas of the theatre form.

• Unpack and discuss “A Summary of the Show.”

Brainstorm around the following prompts and present your ideas back to your peers. You could create a short presentation, record a short podcast on voice notes on your phone or create a big brainstorm, with sketches and annotations on paper. Be creative, how could you share information in a fun and inventive way?

• Identify powerful moments that utilise the features listed above

• Discuss how these features helped to drive the narrative, drew the audience into the story and highlighted important moments

• What moments will stay with you, discuss why

• How do you think the source material impacted the way the performance was structured

• Discuss why using a Theatre Marae framework for this production enhances the performance.

61

UNIQUELY AOTEAROA THEATRE:

Divide into three groups, each with a big piece of craft paper. Take one of the following prompts per group. Discuss how the prompt applies to Witi’s Wahine, why it is important to have theatre that speaks to a Māori world view and think about how this impacts the audience.

• Mauri (life force), Wairua (spirit), Te Reo, Tikanga

• A sense of inner landscape or voice, that speaks to what it means to be Māori and people of this land

• Giving voice to the voiceless, within the parameters of their own cultural practice.

PRACTICAL ACTIVITIES:

Using an idea from your discussion around the prompts above or a story from Witi’s Wahine, as stimulus for a short, devised performance. Brainstorm the storyline and the message you are hoping to communicate to the audience. Using the list of key features from the explanation of Theatre Marae, decide which ones you could use in an appropriate way in a performance.

If appropriate you might draw on classmates, older students or teachers who hold knowledge of Te Reo Māori and Te Ao Haka and can support your learning in your classroom.

Use these questions as a guide:

• How do you introduce the characters of the scene to the audience?

• Should anything preface or come before the performance?

• Would song or movement be appropriate to use to support the story you are trying to communicate to the audience?

• What is the key message you are trying to communicate to the audience? Why is a drama performance the appropriate way to communicate this?

RITUAL IN PERFORMANCE

To provoke ideas to devise from you could do one of the following:

• Brainstorm the themes, symbols and motifs that you drew from the brainstorms and discussions you have had about Witi’s Wahine

• Choose a moment from the brainstorms or discussions that you wish to expand on

Ritual as a Drama Convention

• Ritual appears in everyday life but can be more symbolic or religious

• Discuss the rituals that appear when you visit a Marae.

• Research is encouraged.

62

Choose a small idea from your brainstorms or discussions. Your performance must be ritualised and use the following conventions:

• Chorus of movement

• Slow motion

• Repetition

• Canon

• Features of Theatre Marae you feel are appropriate to use

Complete the following reflection after your performance and use it as a springboard for further drama creation:

• How did you drama conventions or features of Theatre Marae in performance? Describe the examples.

• How did you use our discussions and brainstorms to create a performance?

• What did you think was the most effective part of your performance?

• How could other features of Theatre Marae be incorporated into your performance to extend your ideas?

REFERENCES:

Note: Description of Theatre Marae originally researched and constructed as part of my own classroom teaching and learning. It has been built upon and tweaked for plays that have encompassed the Theatre Marae form in my educational writing.

• Kewene, F. W. (2017). Verbatim and Maori Theatre Techniques: Documenting People’s Experiences of Hauora (Thesis, Master of Arts). University of Otago. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10523/7028

Permanent link to OUR Archive version: http://hdl.handle.net/10523/7028

• Pearse-Otene, H. (2020). Theatre Marae: Maori theatre pedagogy in research. Mai Journal. A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship. Retrieved from: http://www.journal.mai.ac.nz/content/theatre-maraem%C4%81ori-theatre-pedagogy-research

• Purapurawhetu and The Pohutukawa Tree: The bicultural landscape and Maori theatre. Accessed from The Arts/Nga Toi materials www.tki.org.nz/r/arts/drama/purapurawhetu

63

Revision for Drama Externals

Below are the specifications for Achievement Standards for external drama exams (taken from the NZQA website, via the following link: https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/ subjects/assessment-specifications/ )

Keywords are bolded to aid you and the questions in this pack are designed specifically to prompt discussion or written answers that will enable you to revise successfully. You will want to have access to a glossary of Drama Components or Aspects on hand as you revise. Your teacher should have access to these or they can be found at TKI’s Arts Online. This list is not divided into the four categories Techniques, Elements, Conventions and Technologies, so a good starting point would be to make a chart dividing them up and ensuring you know the difference: https:// artsonline.tki.org.nz/Teaching-andLearning/Pedagogy/Drama/Glossary

Level One: 1.7 (90011)

Candidates should be familiar with the use of drama techniques, the use of technologies, character, and elements.

Level Two: 2.7 (91219)

Candidates should be familiar with subtext, the use of drama elements, conventions, and technologies.

Level Three: 3.7 (91518)

Candidates will be expected to make connections between the director and designer’s concept(s) and the performance seen.

Candidates should be familiar with the use of elements such as techniques, and the use of technologies and conventions.

For the purposes of this assessment, “conventions” refers to strategies that are established to make meaning; and “wider context”, as required by the criterion for Achievement with Excellence, could refer to:

• the performance as a whole

• the playwright’s purpose

• the nature and / or purpose of theatre as an art form

• the candidate’s own social, geographical, or historical context.

NOTE: Questions at all levels may cover a combination of elements, techniques, conventions, and technologies.

Revision Questions for Witi’s Wahine

Note: When answering the following question you will want to find and provide physical examples from the production. A physical example is when you describe, with specificity, what is happening on stage at the time. Get down to specific detail, for example, explaining how the actor/ performer is standing or moving, how far away from the audience they are, what is happening with technology, where exactly they are in space, etc. The more detail, the better!

DRAMA TECHNIQUES: BODY, VOICE, MOVEMENT AND SPACE:

• Describe how an actor who you found interesting or compelling used drama techniques in a specific moment in the performance.

• Describe how two or more actors used movement during a moment of tension - what were they communicating with the audience? How did this moment connect with the audience to reveal information?

• Discuss how an actor used drama techniques during a solo moment on stage. What were they aiming to communicate? What did you understand at that moment?

• Explain another actor’s use of drama techniques and how they created a sense of authenticity within the performance.

• Choose specific moments where you felt the actor used their body, voice, movement and space in combination to create impact, focus or to support an important idea.

• Discuss why you think authenticity is important in a contemporary work written by an Aotearoa playwright.

• Thinking about each of the actors and one of the characters they played:

• What did each of the wahine represent within the world of the play?

• How did they use techniques to create a sense of community or unity?

• How did they use techniques to create contrast between them?

• What do they represent in today’s world? Why are their narratives important?

• How did an actor use drama techniques to communicate subtext in their performance? Use a specific moment and example to discuss this use of subtext.

• Discuss what you found compelling about an actor’s use of drama techniques in the performance. Choose a specific moment to focus on.

• Discuss how male characters were represented in the performance. Why do you think these choices were made?

67

CHARACTER:

• Draw up character profiles for compelling or interesting characters presented in the performance - use the following prompts to help you:

• Reference the original text that that the character comes from, what was their purpose in that story? How has this been brought to life in this play?

• How they interacted with the other characters and what this communicated about their character?

• Actor’s use of drama techniques to communicate the character.

• -What did you understand about the character and the story?

• How they challenged you as an audience member

• How their costume, hair and makeup represent their character.

• How subtext was used in a specific moment to communicate an important idea.

DIRECTOR/DESIGNER CONCEPT:

• Discuss how aspects of Theatre Marae were used on the stage in ensemble scenes? How does this enhance the story? What did you understand about the power of each character through the use of key features of this theatre form?

• Discuss the purpose of the performance and how the themes or ideas link to what is happening in the world; socially, politically, or historically. Link your ideas to specific moments or examples from the performance.

• How did the way the performance was realised tell a story about this moment in time in Aotearoa/New Zealand?

• What features of the Theatre Marae did you see within the performance?

• How does the use of this theatre form challenge and serve the audience?

• Discuss how the directors brought the story to life using Drama Components - Elements, Conventions, Techniques and Technologies.

• What do you think Ngapaki Moetara and Teina Moetara are asking you to think about in the way they have directed Witi’s Wahine?

• How did the choices affect you as an audience member?

• What was the impact of the way the design, directorial and acting choices worked together? Choose a moment that surprised, shocked or excited you to talk about.

• Discuss why the use of the earthy colour palette, sound and lighting design was integral to this performance?

DRAMA CONVENTIONS - STRATEGIES ESTABLISHED TO MAKE MEANING AND CONNECT TO WIDER CONTEXT:

(NB - make sure you are familiar with what the established Drama Conventions are by discussing this with your teacher)

• Identify a moment in the performance where Drama Conventions were used to create focus, mood or atmosphere:

• Explain how the convention or combination of conventions were used in the performance

• Discuss the impact of the use of the convention or combination of conventions in this moment

• Discuss how meaning was created for you, as an audience member, in this moment

• Discuss how the use of a convention or combination of conventions in a specific moment helped you think about the big ideas and themes of the play.

• What was the wider context (socially, historically, politically or geographically) that this moment linked to?

DRAMA ELEMENTS AND HOW THEY DRAW OUR ATTENTION TO THEMES, MOTIFS AND SYMBOLS:

• What were the main themes, questions, and ideas evident in the performance? Link these themes, questions and ideas to specific moments or examples from the performance.

• How were design and directorial elements (props, setting, AV, costuming, audience positioning and interaction) and the Drama Elements used to build the performance? How did this make you feel as a member of the audience?

• Identify recurring symbols or motifs throughout the performance. Explain why they were important in helping you understand ideas being communicated in Witi’s Wahine?

• Discuss how subtext was highlighted through the way the directors created focus, mood, and tension in their directing choices.

• How do these themes, symbols or ideas link to the wider world of the play and what impact does this have on the audience?

• Were there moments where the content was confronting or forced you to think about something in a new light? What impact does this have on the audience and you as a member of the audience?

• What story does Witi’s Wahine tell about Aotearoa/New Zealand? What can you link the themes or ideas to?

TECHNOLOGY: LINK YOUR IDEAS TO SPECIFIC MOMENTS OR EXAMPLES IN THE PERFORMANCE.

Think about lighting, set, sound, props, costumes, make-up and how this helped bring you into the world of the play.

• How was technology used to create the atmosphere in the performance?

• How was technology used to support a contemporary realisation of a Shakespearean performance?

• How was technology used to highlight important ideas, themes and symbols in the performance?

• How was contrast and/or focus created or built through technology and why was this important?

• How did the use of technology help you gain a deeper understanding of the themes of Witi’s Wahine?

• How did technology highlight each of the actors within the performance?

• Discuss why this was impactful, exciting or challenged your expectations.

• How were costumes used to communicate the character or actors purpose in the performance?

• How did the use of technology highlight or enhance a character's use of subtext in the performance? You could think about:

• How does lighting contribute to mood or tension in a specific moment that highlights the character's use of subtext?

• How does sound underscore a moment where a character is using specific subtext? What does this help you understand as an audience member?

• How do actors’ placement on the stage enhance a moment of subtext?

• How the use of a prop supported an actor’s communication of subtext in a specific moment.

IMPORTANT NOTE: When you are writing about Set or Costume, you need to be specific about the following details and also sketch what you see. Imagine the person you are writing for has not seen the production and create a vivid image in their mind of what you saw:

• For example: Set/Props

• The size, shape and dimensions of any set pieces or props used

• The materials used, their textures and the colours

Education Pack Writers: Acacia O’Connor and Anna Richardson

Education Pack Graphic Designer: Wanda Tambrin

Article reprinted with permission of Penguin Random House NZ

PRINCIPAL FUNDERS:

CORE FUNDER:

UNIVERSITY PARTNER:

SAVE THE DATE FOR 2024 SEASON LAUNCH

Be the first to learn about Auckland Theatre Company's 2024 lineup of shows and the creative learning programme for schools. Keep an eye on your inbox and post-box from Tuesday 10 October

Aotearoa’s healthcare system has a much-needed check-up.

Things That Matter

BY GARY HENDERSON

adapted from the memoir by David Galler

11 – 26 Aug | BOOK NOW atc.co.nz

Left: Photos taken inside Rongopai Marae

Right: The fabrics that were then found to make the costumes of the four leads.

This painting by Ngati Porou artist, Sofia Minson: The Navigators

Left: Photos taken inside Rongopai Marae

Right: The fabrics that were then found to make the costumes of the four leads.

This painting by Ngati Porou artist, Sofia Minson: The Navigators