1.1.Background Study

1.1.1.Defining

Slums

A slum is a densely populated urban residential area with compact dwellings and incomplete infrastructure, primarily inhabited by impoverished people. In recent times urbanization has led to over 50% of people living in urban areas worldwide (Fig 1) and is expected to reach 66% by 2050, with more than 50% of people living in cities in nearly every nation. 1

Figure 1: Share of urban population living in urban areas by 2050(Source: UN Human Settlements Programme)

The word "slum" initially originated to describe a "room of low repute" or "undeveloped poor region of the town" in London at the beginning of the 19th century, but its definition has changed ever since While physical, spatial, social, and behavioural aspects of urban poverty were included in early definitions of slum dwelling the range of associations has recently decreased.2 The United Nations Program on Human Settlements has redefined a slum as "a contiguous settlement where the inhabitants are characterised as having inadequate housing and basic services.” The public authorities frequently fail to acknowledge and treat slums as equal or essential components of the city.3

1 The Challenge of Slums - Global Report on Human Settlements 2003 | UN-Habitat” 2003

2 Nolan, Laura B. “Slum Definitions in Urban India: Implications for the Measurement of Health Inequalities.” Population and Development Review 41, no. 1 (March 1, 2015): 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00026.x

3 “Urbanization.” Our World in Data, February 23, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization

1.1.2.Slums in India

Slums are the residential areas in cities that are generally uninhabitable due to poor building structures, overpopulation, narrowness, faulty arrangements of street designs, and lack of basic facilities like water, light and sanitation. The term ‘slum’ is usually recognised for its three distinct characteristics which are physical, social, and economic.4

The government of India has been changing the definition for identifying slums since the development of the first policy for Slums, in the year 1956 “Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act”. Various authorities, such as state and local administrations, have different definitions for slums.5

Figure 2: Contrast showing formal and informal housing implying unequal development. (Source: Google)

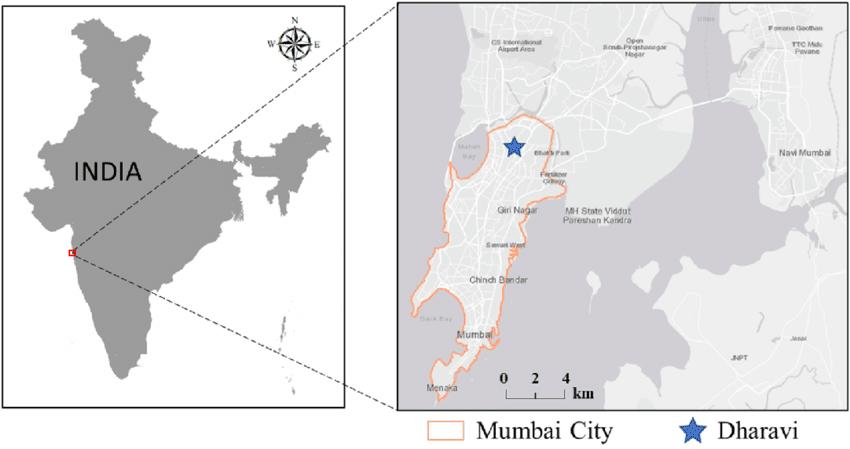

2.1.Dharavi

With more than six million people living in Mumbai, it is known as ‘Slumbai or Slumbay’ as it is home to one of the biggest populations of slum-dwellers worldwide. Mumbai, India's financial hub, draws a lot of skilled immigrants seeking jobs, which increases housing costs and leads to the development of slums6

4 “Urbanization and Condition of Urban Slums in India.” Indonesian Journal of Geography 48, no. 1 (August 2, 2016): 28. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.12466

5 “Urbanization and Condition of Urban Slums in India.” Indonesian Journal of Geography 48, no. 1 (August 2, 2016): 28. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.12466

6 Baweja, Vandana. "Architecture and Urbanism in 'Slumdog Millionaire': From Bombay to Mumbai." Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 26 (2015): 7-24. https://architexturez.net/doc/10-2307/24347523

With several development plans under consideration, Dharavi has been the centre of attention because of its central location in Mumbai. Dharavi is crucial for the transformation of Mumbai, according to the State Government, local real estate developers, and global capital investment firms.Dharavihas attracted alotofattentionfromprivateandpublic developers inrecentyears. This slum settlement is ideally located between the Western and Central Railways, Mumbai's two main suburban railway lines. Thousands of people are connected by these railway lines, due to which it acts as Mumbai's primary transit hub. This has additionally added to the rising land value of Dharavi.7

3: Location map of Dharavi (Source: Google)

2.2. History of Dharavi

The history of Dharavi is divided into colonial, post-independence, and post-1981 when the Dharavi Redevelopment Project was proposed. In pre-colonial times, Dharavi was home to the ‘Koli fishing community’, relying on the Mahim Creek 8 for fish and livelihood for centuries.9

Portuguese were the first colonists in the area during the colonial period to build a small fort and church in Mumbai’s Bandra district. The second British governor of Bombay, Gerald

7 Sharma, Kalpana. 2000. Rediscovering Dharavi. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

8 “Mahim Creek” is a tidal channel in Bombay (Mumbai). The creek is swamped by mangroves and has a miniecosystem within it.

9 Sharma, Kalpana. 2000. Rediscovering Dharavi. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

Figure

Aungier built the Riwa (Rehwa) Fort at Dharavi in 1737. In the 18th century, the swamps and salt pans separating the islands of Bombay began to be reclaimed, and efforts were made by connecting all seven islands into one landmass. This reclamation resulted in the drying up of the Mahim Creek, leaving the fisherfolk stranded and thus creating new space for new communities to settle in.10

In the late 19th century, Mumbai was divided into a colonial area in the south and a native area in the north. Dharavi, originally it was a fishing village, was located at the northernmost edge of the native part. In 1877, potters from Saurashtra Bombay settled in Dharavi, establishing the "Kumbharwada" pottery community. With the arrival of the first tannery in 1887, Dharavi's economic activities were expanded and Muslim tanners from Tamil Nadu were brought in. In the early 20th century, migration caused major changes in Dharavi, which led to the construction of community spaces like schools and temples. After independence, Dharavi developed into a centre for immigration and unofficial settlements. Dharavi is now a very valuable piece of land because of its proximity to the airport and railway lines.11

4:Location map of Khumbarwada (Source: Google)

10 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010. https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

11 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

Figure

Figure 5: Timeline of Dharavi ((R[e] Interpreting, Imagining, Developing Dharavi))

2.3.Living Conditions in Dharavi

Dharavi is just not one place, but a collection of distinct neighbourhoods connected by mazes of lanes. Each neighbourhood has its unique characteristics and layout. The common features among these neighbourhoods are houses connected to narrow streets, shared public toilets, lack of basic infrastructure such as toilets, and lack of light and ventilation, as the houses are built close to each other without setbacks12 . The settlements intersect and diverge in mysterious ways, with only the residents capable of explaining the rationale behind the divisions. Each neighbourhood differs greatly from each other, not just by the communities in that locality but also by the history of their development. The Chawls, for example, are low-rise buildings with tiled roofs that were constructed for mill workers. Usually, the units are single-bedroom apartments that open on the same side to a shared corridor. At present these chawls are surrounded mostly by unplanned structures. Certain neighbourhoods, like Kumbharwada, have evolved to accommodate the occupations of the locals; where the backyard of the house is a workspace and the front acts as a shop to sell their products. Although some developments have been made in some neighbourhoods, such as moving the tanners, high-rise buildings now stand on the outer edges of the settlement, which seems abnormal compared to the surrounding landscape of slums and unplanned structures.13 However, most of Dharavi remains badly in need of organization, sanitation, adequate and clean water, and decent housing.

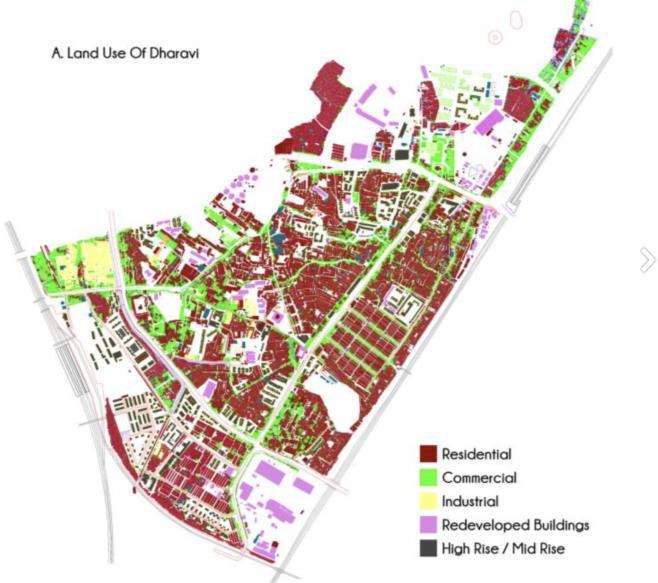

2.4.Site Analysis of Dharavi

Dharavi is a 239-hectare (2390000 sq.m) informal settlement with diverse land use. It is almost the size of a small township and has a very highpopulation density, estimated at 18,000 persons per acre (4046.8 sq.m). Within this densely populated area, there are 27 temples, 11 mosques, and 6 churches.14 The land use pattern of Dharavi has a variety of uses, such as residential, business, and industrial. The majority of the buildings in Dharavi have been classified as huts by the government due to their lack of structural stability and poor construction. while the residential areas are mainly concentrated within the inner clusters,15 the industrial and

12 Liza Weinstein and Xuefei Ren, “The Changing Right to the City: Urban Renewal and Housing Rights in Globalizing Shanghai and Mumbai,” City and Community 8, no. 4 (December 1, 2009): 407–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01300.x

13 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010. https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

14 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

15 Clusters: groups of buildings usually with shared amenities such as green space or parking

commercial spaces are mostly aligned to the main roads and streets. Major industries are located in the western part of Dharavi, while smaller industries are scattered throughout the settlement, often hidden between housing units or occupying the upper floors of the residential building.16

Figure 6: Land Use Map of Dharavi (Source: Google)

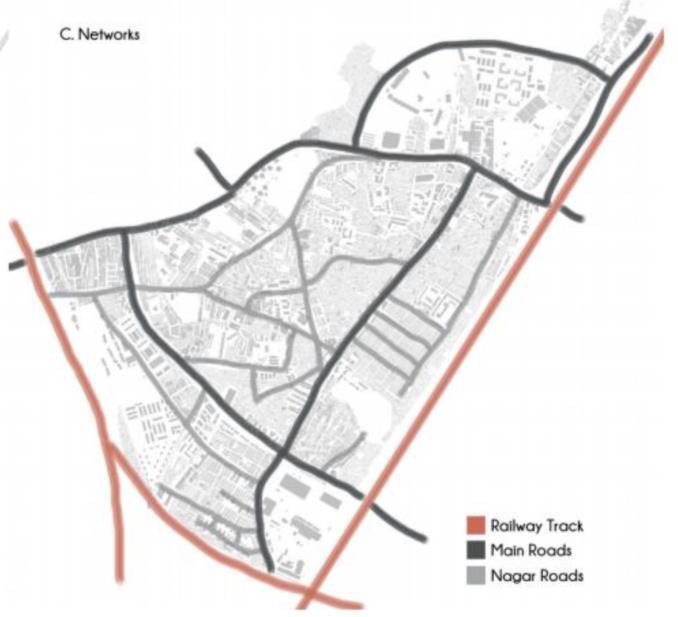

Over the years, several government-led developments have resulted in high-rise buildings along the main roads, particularly along the 18-metre-wide road area initially occupied by Tanners17. These tanners were asked to relocate to the outskirts of Mumbai, leaving behind large empty sites for developers to build high-rise buildings.18 Dharavi can be accessed through several different routes and is conveniently located within easy reach of three railway stations: Matunga and Mahim on the Western Railway and Sion on the Central Railway. It is also linked by two link roads that connect East and West Mumbai - Sion and Mahim. The eastern and southern boundaries of Dharavi are the railway tracks of Central and Western Railways, while

16 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

17 Tanners: hunters and butchers (the suppliers of skins) and leatherworkers who made commercial products from the tanned hides.

18 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

theeasternandnorthernboundary iscreatedbytheSion-MahimLinkroad,creating atriangular shape plan for Dharavi.19

Figure 7: Transport Network of Dharavi (Source: Google)

Two major roads connect the internal settlement, the 27-metre wide road running northeast to southwest and the 18-metre wide road running northwest to southeast. Major streets in Dharavi are connected to these roads, and it is apparent from the land use map that major formal developments in Dharavi are along these roads20 .

Dharavi's urban fabric has distinctive characters in different neighbourhoods. The neighbourhood of Kumbharwada in Dharavi has an urban fabric that comprises four divisions known as wadis, each with its distinct character and used as a workspace and public space21 .

3.1.Research Area (Site)

Khumbarwada was one of the first settlements built in Dharavi in the 19th century by the Gujarati community whose major profession was pottery back then. This community migrated

19 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010. https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

20 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

21 SPARC, Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, Aneerudha Paul, and Sheela Patel. Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010 https://sdinet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/ReDharavi1.pdf

to Dharavi after their native in the state of Gujarat was hit by drought. Initially there were about 250 families that migrated but over the years this number increased to up to 2000 families. 22 Atpresentthiscommunityoccupies12.5acres(50585.71sq.m)ofDharavi’sland.In the1930s, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) allocated land in Dharavi to the Prajapati Sahakari Utpadak Mandal, a cooperative society of potters, for pottery-related activities. Nowadays, out of the approximately 250 original tenants, about 120 still engage in potterywithsmallkilns.Theneighbourhood'sname,'Kumbharwada', comesfromHindi,where 'kumbhar' refers to potters, a caste of ceramicists, and 'wada' means the area or neighbourhood23

3.2.Why Khumbarwada?

The settlements of Khumbarwada provides a unique opportunity for analysing environmental performance and climate-resilient architecture due to several key factors such as:

• The cultural significance of the community in Khumbarwada lies in pottery making which has been their profession for decades. This is at risk due to rapid urbanisation thus making it necessary to explore sustainable architecture solutions to preserve the heritage and enhance the environmental performance of the settlement.

• Due to high population density, Khumbarwada faces challenges in urban planning and environmental sustainability thus providing an opportunity to explore climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable architecture by addressing the present living conditions.

• This dissertation focuses on the importance of community involvement in urban regeneration efforts. As the residents of Khumbarwada have a personal interest in improving their living conditions without losing their cultural roots this location is ideal for studying community-led initiatives aimed at enhancing environmental performance.

• Kumbharwada faces threats from Dharavi Redevelopment Plan 2030 led by Govt. of Maharashtra in collaboration with The Adani Group which overlooks the livelihoods of the residents. Thus, this context is important for analysing how climate-resilient architecture can protect the community and environment from unsustainable growth while preserving the values of the community.

22 “Kumbharwada - a Pottery Village | Urbz,” December 15, 2016. https://urbz.net/articles/kumbharwadapottery-village

23 Rupali Gupte et al., “TYPOLOGIES and BEYOND,” July 2010, https://crit.in/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/slumtypologies1.pdf.

In summary, the unique socio-cultural and environmental context makes it a perfect location for studying how to enhance environmental performance and develop climate-resilient architecture in slums. This settlement provides a compelling case for research due to the challenges faced by the community, combined with their active participation in regeneration efforts.

3.3.Living conditions in Khumbarwada

The houses in Kumbharwada are designed to double as workplaces, as the nature of the work requires day-long involvement and yields minimal income. Most of the houses are long and narrow, set in long rows with streets and open spaces between them where kilns, workspaces, and storage spaces for the pottery business are located. Houses that face the main roads have shops for selling the products. The ground stories of these houses are built with brick or timber framing, while upper stories are constructed with timber or steel framing and tin sheet cladding.

Figure 8: Site Map of Dharavi (urbz)

Additionally, part of the house is used as a storage space for raw materials and finished products.24

4.1.Aims and Objectives

This dissertation aims to assess the current living conditions, past and present policies, and to study the successful climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable practices in similar cases around the world. The goal is to propose a design framework and set of policies for urban planners and policymakers to follow to redevelop slums like Dharavi in a climateconscious manner by preserving the social and cultural heritage of the residents by providing them with better living conditions.

5.1.Research topic

The main goal of this research is to tackle the challenges faced by the residents of slums in terms of living conditions and enhancing the living conditions with Climate-conscious design strategies while preserving the sociocultural roots of the community. The main interest of this research is the settlement in Khumbarwada because of its unique socio-cultural and economic characteristics and an emerging need for sustainable development. Khumbarwada has been home to hundreds to thousands of pottery-making families over the past many decades thus holding a rich cultural heritage and community spirit. This research aims to evaluate the

24Rupali Gupte et al., “TYPOLOGIES and BEYOND,” July 2010, https://crit.in/wpcontent/uploads/2011/10/slumtypologies1.pdf .

Figure 9: Images of Khumbarwada, Dharavi (Alamy)

possibility of using climate-conscious and environmentally sustainable architecture in current low-rise buildings with few modifications to the layout and thermal comfort.

6.1.Research Question

6.1.1.Main Question

Can climate-responsive design strategies enhance the living standards in Khumbarwada, Dharavi while preserving the socio-economic fabric of the community?

6.1.2.Sub Question

1. Accessing the current situation:

• What are the present environmental and infrastructural issues of Khumbarwada, and how do they impact resident’s living conditions?

• How have the residents of Khumbarwada transformed their living conditions due to climatic and sociocultural shifts, and is this transformation beneficial or detrimental?

2. Considering the failure of previous policies and implementation from 1971 what can be learnt from Dharavi's previous and current urban regeneration initiatives that have not been successful in addressing the city's core issues?

3. With a focus on housing, what are the possible advantages and disadvantages of implementing climate-responsive design strategies on the clusters of housing in the Khumbarwada area?

7.1.Literature review

7.1.1.Understanding previous policies

The slums of Dharavi provide housing and various economic opportunities for the migrants but at the same time, they face many challenges related to living conditions. In response, the Government of India and local authorities in Mumbai have launched initiatives to improve living conditions and upgrade slums over the years.

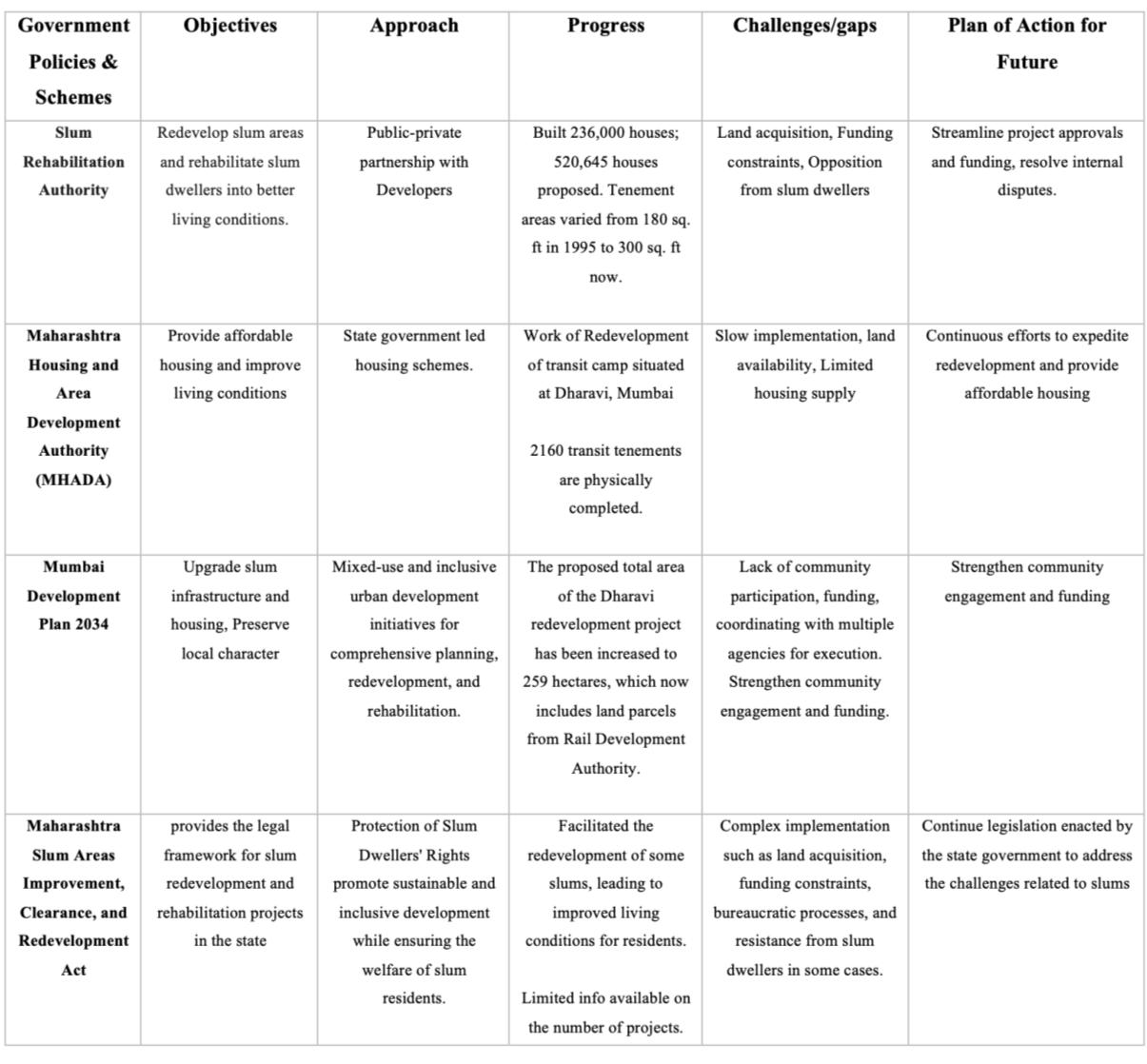

Table 1: Policies developed by the government and other authorities over the years to support the development of Dharavi (Author)

The initiatives and policies were developed to improve the living conditions for the people of Dharavi. Rapid urbanization and limited resources in the past have presented many challenges. Upgrading the slums while ensuring sustainable growth is difficult given the past efforts.25

7.1.2.Case Study 1

There have been very few successful attempts to solve the problem of slum upgradation or redevelopment around the world where the dwellers have accepted the proposal. This case study focuses on a slum regeneration project in India.

25 Nagargoje, Arundhati Thakur School of Architecture & Planning, Mumbai, SDSN’s Youth Fellow, Local Pathway Fellowship, 2023. https://ic-sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-submission_701.pdf

Yerwada Slum Redevelopment, Pune, India

The project began in 2009 to create a "Sustainable slum less city" in the long term. The main aim of the project was to create an Incremental Housing Strategy that could be implemented anywhere, the government worked with several non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including Mahila Milan, the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF), and the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC). The beneficiary community's participation, contribution, and consent are necessary for the sustainable improvement of housing.26

Four key design elements were created by Stockholm-based architects Filipe Balestra and Sara Göransson. The first and most important is that the project respects the neighbourhood's preexisting social networks and makes use of its organic patterns that have evolved over time. The goal has been to preserve the slum's general layout, including the street patterns and house footprints that are still there. The buildings were initially recognised by the team as Pacca and Kaccha houses, respectively. Pacca houses are defined as permanent houses or houses with a solid structural foundation and basic utilities, while Kaccha houses are temporary homes constructed of lightweight materials without basic amenities.27

The team proposed Three single-family house prototypes for upgradation, with each family being permitted to select the design that best suited their needs. The participants were also free to alter the selected prototype slightly to suit their own needs or not to take part in the project at all. Although the structure was designed to be two stories, it had the structural stability to support three stories, so the user was free to add more floors in the future. The prototype had the following design: House A is a two-story house with a three-story structural layout that enables the owner to expand the home vertically without taking any structural risks in the future.28

26 Srivatsa, Shreyas, Sandeep Virmani, Vidhya Mohankumar, Vikas Jha, and Mangesh Wagle. Incremental Housing Strategy: Yerawada - Project Review, Human Settlements. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281647512_Incremental_Housing_Strategy_Yerawada__Project_Review_Human_Settlements

27 Srivatsa, Shreyas, Sandeep Virmani, Vidhya Mohankumar, Vikas Jha, and Mangesh Wagle. Incremental Housing Strategy: Yerawada - Project Review, Human Settlements. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281647512_Incremental_Housing_Strategy_Yerawada__Project_Review_Human_Settlements

28 Srivatsa, Shreyas, Sandeep Virmani, Vidhya Mohankumar, Vikas Jha, and Mangesh Wagle. Incremental Housing Strategy: Yerawada - Project Review, Human Settlements. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281647512_Incremental_Housing_Strategy_Yerawada__Project_Review_Human_Settlements.

The project demonstrated successful collaboration among various stakeholders, including the government, professionals, non-governmental organisations, and local representatives. House B is a two-story house on pilots that gives its owner the option to use the space for parking or to add a shop or an additional bedroom. House C is a three-story building with a gap in the centre. The family can close it off to make room for a new bedroom in the future, or use it as a courtyard, living area, or workspace.29

29 Srivatsa, Shreyas, Sandeep Virmani, Vidhya Mohankumar, Vikas Jha, and Mangesh Wagle. Incremental Housing Strategy: Yerawada - Project Review, Human Settlements. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281647512_Incremental_Housing_Strategy_Yerawada__Project_Review_Human_Settlements.

Figure 10: Image of Community Involvement in slum regeneration (Alamy)

Figure 11: Strategies for incremental housing (Incremental Housing Strategy)

8.1.Research Methodology

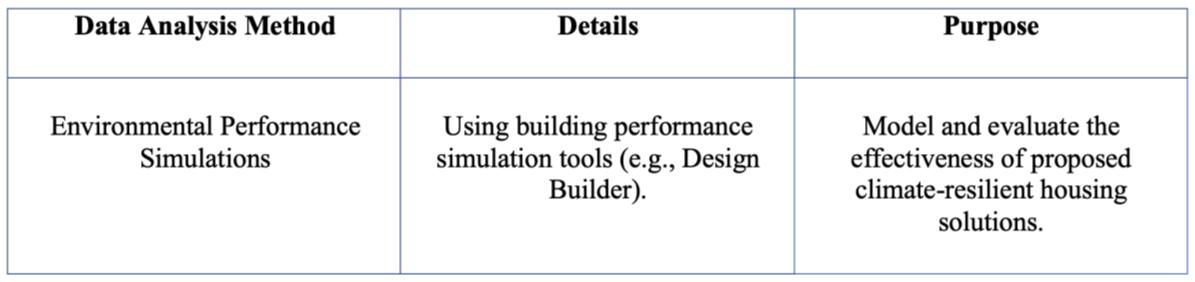

This dissertation uses a mix of methods for its research design. Combining qualitative and quantitative techniques to analyse the environmental performance and climate-resilient architecture of Khumbarwada. This approach aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the social and cultural dynamics, environmental conditions, and architectural practices in the slum.

Figure 12: Flow Diagram of Research Methodology (Author)

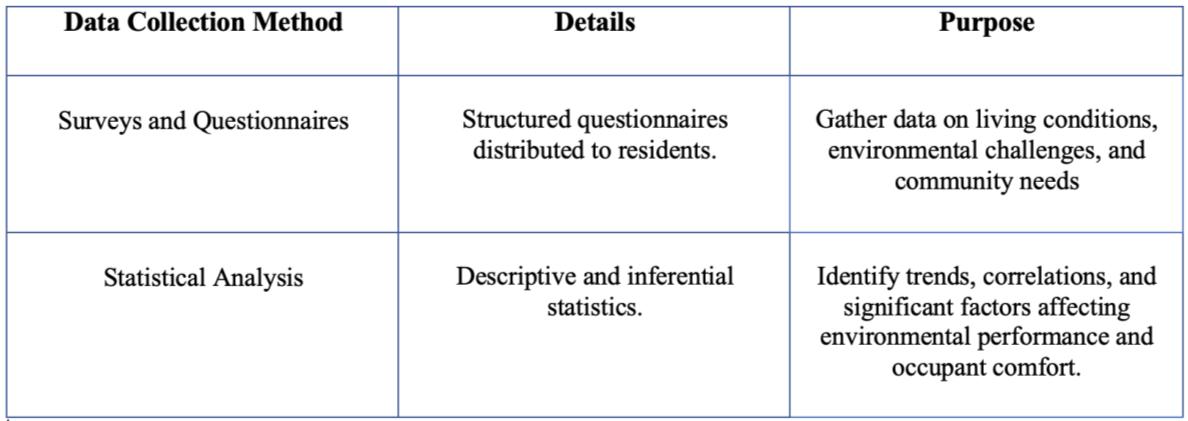

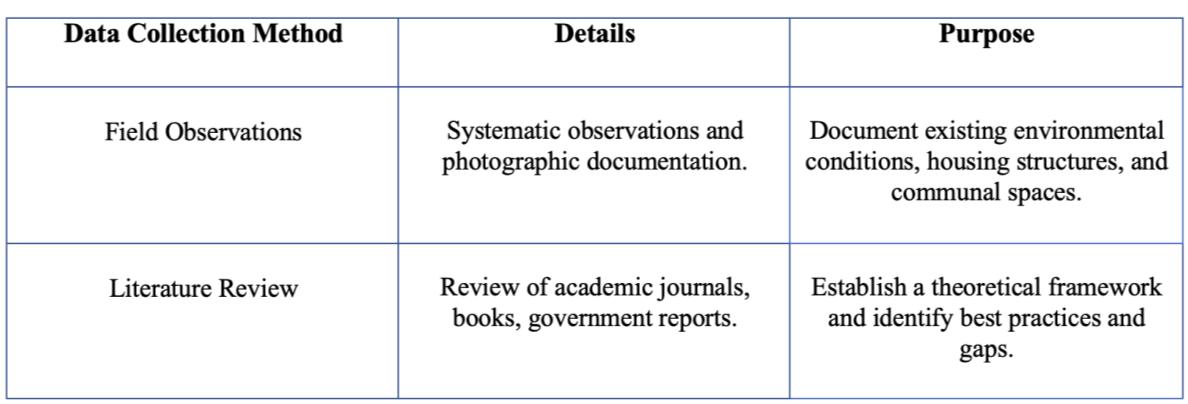

Table 2: Quantitative method for data collection (Author)

Table 3: Qualitative method for data collection (Author)

Table 4: Qualitative method for data analysis (Author)

Table 5: Qualitative method for data analysis (Author)

9.1.Conclusion

Through a comprehensive mixed-method approach this dissertation aims to enhance Climate Resilience and living conditions in Kumbharwada, Dharavi. This study will aim to provide a holistic understanding of current living conditions, environmental challenges and community needs by integrating quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. This approach does not only address the pressing need for living conditions but also preserves the cultural heritage and community spirit of Khumbarwada. The development of low-rise housing solutionswillbe guided by environmentalperformancesimulationsthatofferpractical climateresilient housing solutions that improve indoor and outdoor living conditions. The proposed design strategies and policy criteria will be culturally sensitive, ensuring they resonate with the local community of Khumbarwada. The findings from this study will provide a valuable example for similar informal settlements, like the slums of Dharavi worldwide, promoting a balanced approach to modernization that values and enhances the existing social and cultural landscape.

Figure 13: Gantt Chart for dissertation project(Author)

10.1.Bibliography

1. Baweja, Vandana. "Architecture and Urbanism in 'Slumdog Millionaire': From Bombay to Mumbai." Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 26 (2015): 7-24. https://architexturez.net/doc/10-2307/24347523

2. Digambar Abaji Chimankar, “Urbanization and Condition of Urban Slums in India,” Indonesian Journal of Geography 48, no. 1 (August 2, 2016): 28, https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.12466.

3. Gupte, Rupali, Prasad Shetty, Collective Research Initiatives Trust (CRIT), Rajeev Mishra, Sir. JJ College of Architecture, Anuja Mayadeo, Apoorva Jalindre, et al. “TYPOLOGIES and BEYOND,” July 2010. https://crit.in/wpcontent/uploads/2011/10/slumtypologies1.pdf.

4. Hannah Ritchie, Veronika Samborska, and Max Roser, “Urbanization,” Our World in Data, February 23, 2024, https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization.

5. “Kumbharwada - a Pottery Village | Urbz,” December 15, 2016, https://urbz.net/articles/kumbharwada-pottery-village.

6. Laura B. Nolan, “Slum Definitions in Urban India: Implications for the Measurement of Health Inequalities,” Population and Development Review 41, no. 1 (March 1, 2015): 59–84, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00026.x

7. Liza Weinstein and Xuefei Ren, “The Changing Right to the City: Urban Renewal and Housing Rights in Globalizing Shanghai and Mumbai,” City and Community 8, no. 4 (December 1, 2009): 407–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01300.x.

8. Nagargoje, Arundhati. Thakur School of Architecture & Planning, Mumbai, SDSN’s Youth Fellow, Local Pathway Fellowship, 2023. https://ic-sd.org/wpcontent/uploads/2023/10/2023-submission_701.pdf

9. SPARC et al., Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, 2010.

10. Srivatsa, Shreyas, Sandeep Virmani, Vidhya Mohankumar, Vikas Jha, and Mangesh Wagle. Incremental Housing Strategy: Yerawada - Project Review, Human Settlements. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281647512_Incremental_Housing_Strategy _Yerawada_-_Project_Review_Human_Settlements

11. United Nations Human Settlements Programme, U.N. (2003) The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003. 1st edn. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group.

12. Note: for this report, I have used the AI-Powered writing bot Grammarly (https://app.grammarly.com ) to find and correct low-level errors and I have used plagiarism checker ( https://plagiarismdetector.net ) as well.