DAVID AARON

A GODDESS BY THE GREYWACKE

MASTER

LONDON | 2025

A GODDESS BY THE GREYWACKE MASTER

'when we consider the work is executed in the hardest kinds of stone... few will deny that the best of Egyptian sculptors must be reckoned among the greatest artists of antiquity.'

E.A. Wallis Budge, A history of Egypt: from the end of the Neolithic period to the death of Cleopatra VII, B.C. 30 (London, 1902)

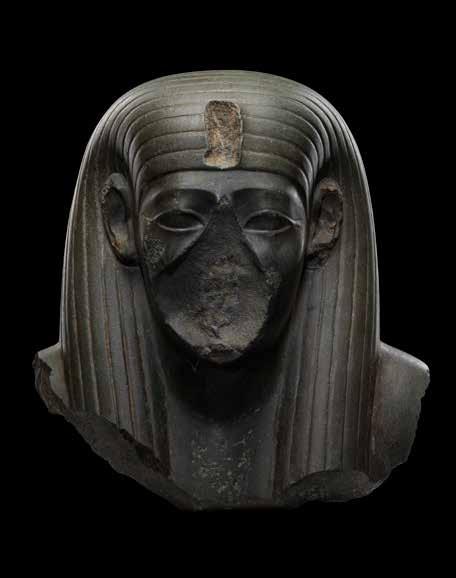

A Goddess by the Greywacke Master

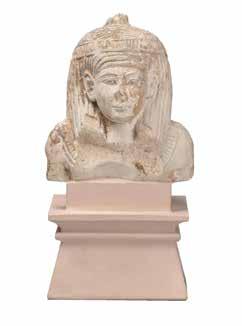

A masterful statue carved from dark grey stone that mystified experts when it was offered for sale in a small local UK auction house in 2022. Its delicately carved features recall some of the finest craftsmanship of 26th Dynasty Egypt, positioning it alongside masterworks from important temples and now in major museums. However, outdated restoration practices left layers of dark paint, wax, and damage on the bust, hiding its true antiquity.

Through extensive provenance research and conservation work, the history of these damages and restorations was unveiled, revealing the statue’s tumultuous journey through time. Through ancient reuse and iconoclasm, eighteenth-century recarving and restoration, and early twentieth-century cosmetic interventions, this bust tells a story of changing attitudes towards ancient statuary over time, and how we can best study and care for them today.

Provenance

Brief Description

A Goddess Rediscovered and Unearthing the Provenance Documented History

Investigating the Provenance and Attribution Scientific Analysis Dating the Restoration Attributing a Masterpiece Understanding the History

Bernard V. Bothmer

Restoration of the Greywacke Goddess Restoration Timeline

Assessing the Damage Smashing Statues and Accident or Iconoclasm? Reuse and Recycle

18th- Century Restorations Under Our Noses

Identifying the Stone Metagreywacke

Wadi Hammamat

The Turin Mining Papyrus

Sculpting History: The Fascination with Greywacke Time-line of Important Greywacke Sculpture

The Greywacke Master

A New Work by the Master The Temple of Neith at Sais

Egypt in the 26th Dynasty

The 26th Dynasty Amasis II (r. 570-526 B.C.)

Collecting Egypt: Ancient Roman Collectors

Hadrian's Villa

18th-Century Italian Excavations

Other Known Goddesses in Stone

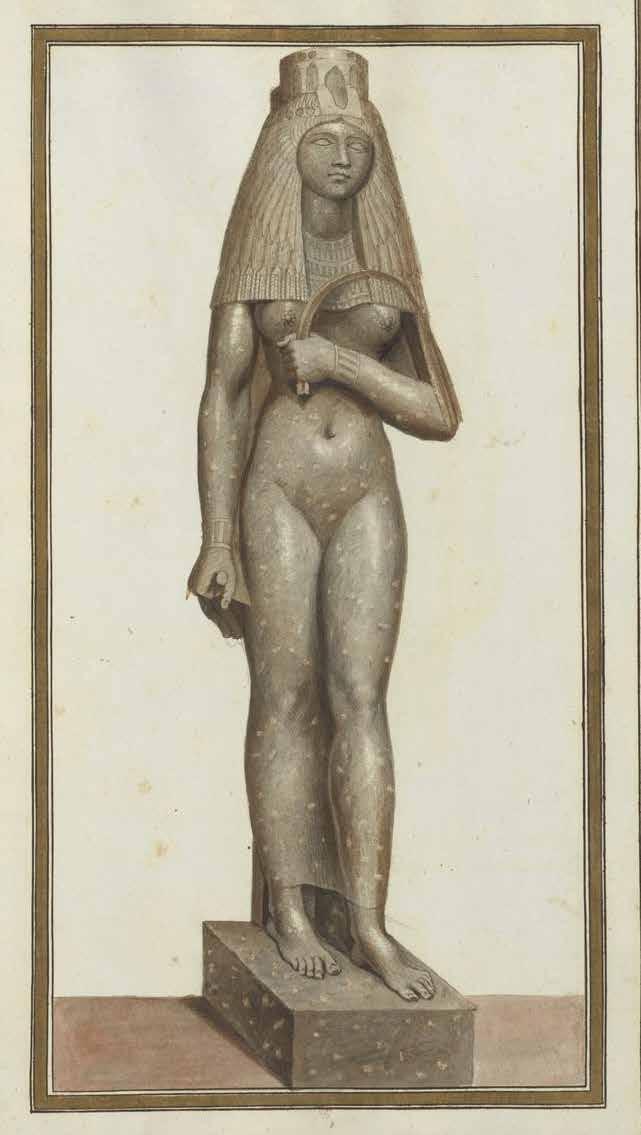

'The chronicle of this sculpture began over two and a half millennia ago, during the reign of King Amasis (570-526 B.C.). Subsequent alterations, as well as damage both intentional and accidental, have contributed subtly to the serene beauty of the original. The creator of this sculpture was the Greywacke Master who carved some of the most beautiful statuary made in ancient Egypt.'

A Goddess by the Greywacke Master

Dynasty XXVI, Reign of Amasis, 570-526 B.C.,

Egypt

Greywacke

H: 24 cm

Provenance

Most likely from the Temple of Neith at Sais, Egypt.

Previously in an 18th-Century European Collection, based on historical restorations.

Sold at: Objets d’Art, Antiques Egyptiens, Grecs, Romains, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 12 February 1923, Lot 55.

With Mr. Miguel, acquired from the above, according to sale notes of the auctioneer André Desvouges.

London art market from at least 1978.

Sold at: Fine Antiquities, Christie’s, London, 14 June 1978, Lot 387 (consigned from the above).

Private Collection, UK, acquired from the above sale.

Thence by descent.

Sold at: Stroud Auctions Rooms, Gloucestershire, UK, 12 January 2022, Lot 1300A.

London art market, acquired from the above sale.

With David Aaron Ltd., acquired from the above on 3 February 2023.

ALR: S00235260, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

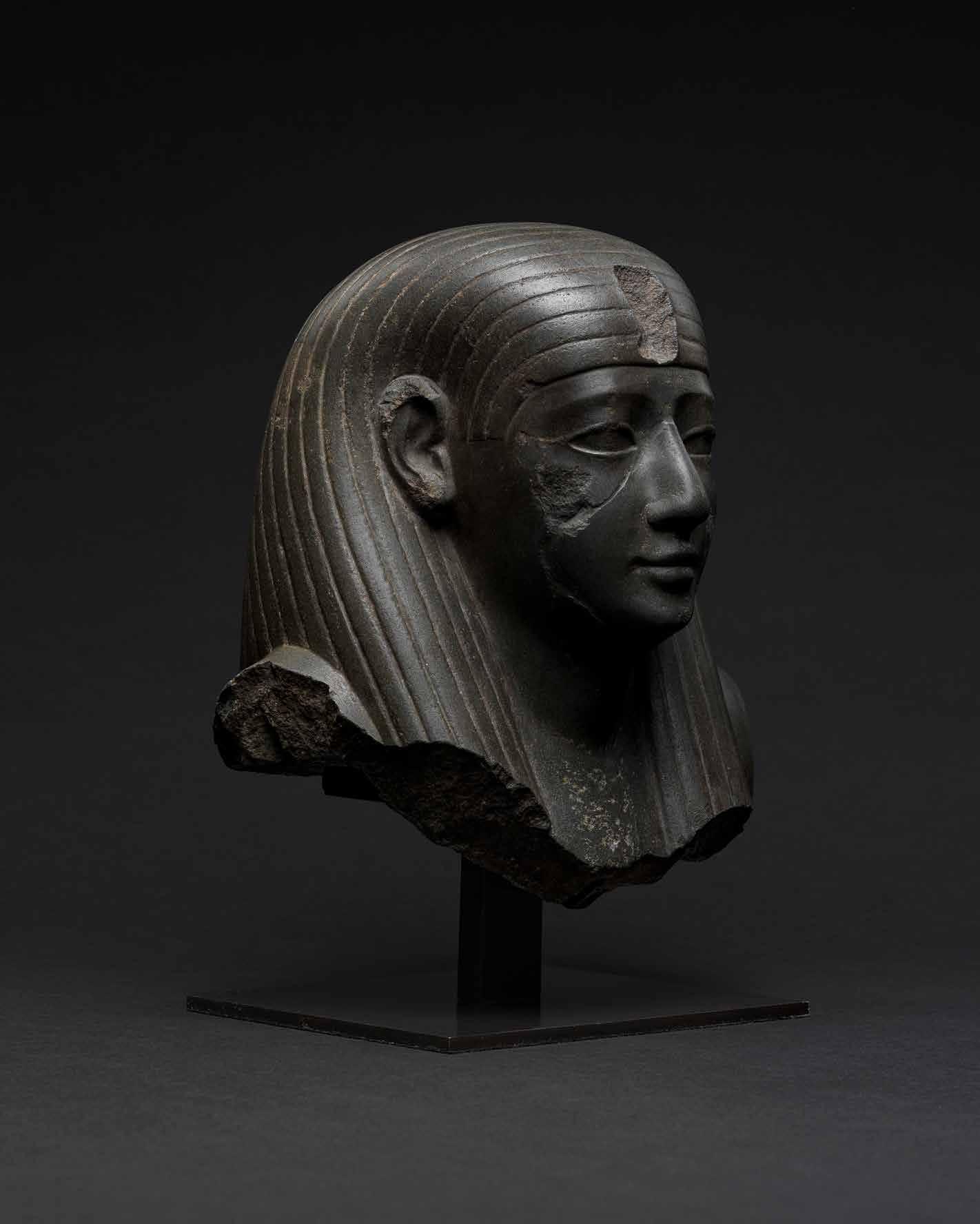

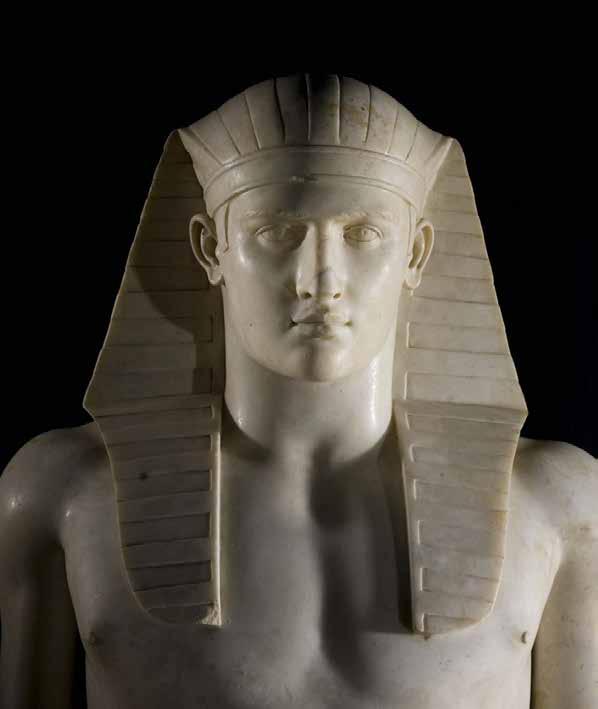

A fine Egyptian head of a goddess carved from dark metagreywacke stone. The facial features are smoothly carved, with lightly suggested eyebrows above eyes with extended cosmetic lines. Both ears are visible in front of the wig. The tripartite wig is parted unusually over the shoulders, with incised lines dividing into two sections above the centre of each shoulder, one parting forwards in a smooth curve, the other running parallel to the lines down the back of the wig. Damage to the front of the wig suggests it was originally surmounted by a uraeus. The nose, mouth, and chin were previously skilfully restored, using a piece of stone taken from the underside rear of the head, most likely in the eighteenth-century.

The metagreywacke (or greywacke) rock is commonly misidentified as schist, slate, or basalt. It occurs in many parts of Egypt’s Eastern Desert, but its only known quarry is in Wadi Hammamat. This stone was worked with intermittently from at least as early as 3200 B.C. until about 250 A.D.. We know this from the thousands of dated objects carved from metagreywacke and the hundreds of dated inscriptions on the quarry walls; the Late Period was certainly a time when major quarrying occurred in Wadi Hammamat.

'For forty-four years, this bust was hidden from the public eye, but has now been revealed as the work of the Greywacke Master.'

A Goddess Rediscovered

In January 2022, a bust carved from greenish-black stone and wearing an Egyptian wig was listed for sale by a small auction house in Gloucestershire. Although the piece was very finely carved, with smooth facial features and a serene expression, it was covered in a thick layer of some kind of paint or wax. This, combined with the poor quality of the available photographs, puzzled experts, who could not work out if it was a true ancient Egyptian work, or a later imitation or fake. However, through two years of careful cross-disciplinary research, we discovered that not only was the piece an authentic antiquity, but that it underwent a fascinating transformation in its journey through the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries

Unearthing the Provenance

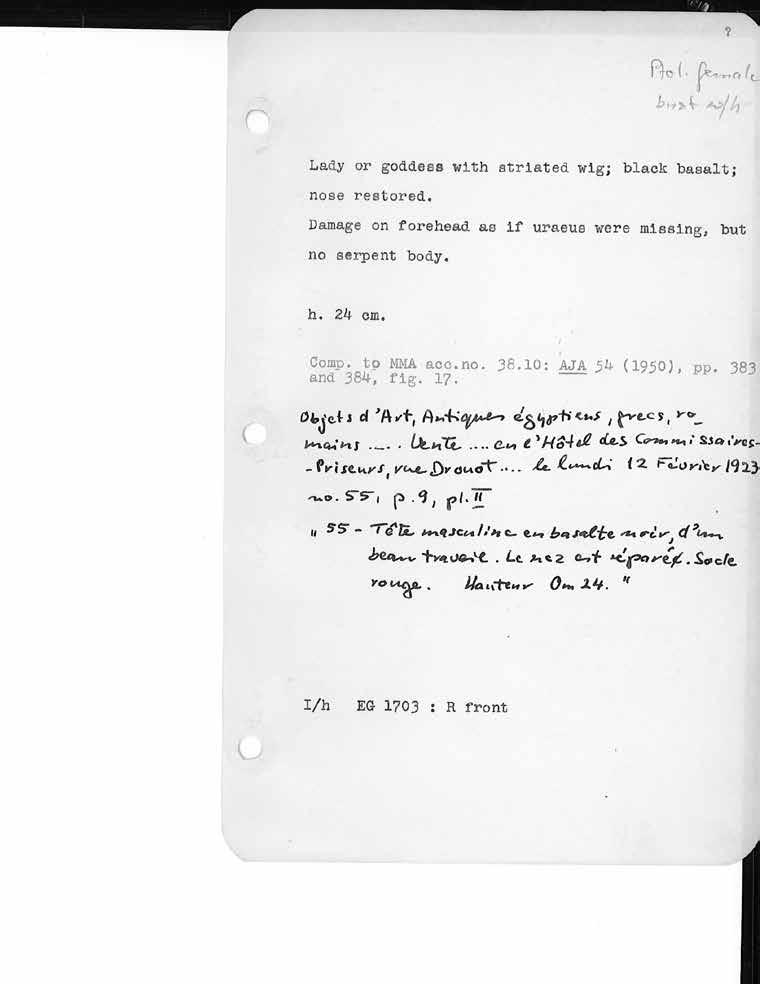

Our investigation into the bust’s provenance began when we found it in a 1923 publication. The head was listed and illustrated as Lot 55 in a sale at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, which took place on 12 February 1923. The catalogue describes it as, ‘Tête masculine en basalte noir, d’un beau travail. Le nez est reparé’. The photograph in the publication also shows that at this stage, the restorations to the face had already been made.

Interestingly, Curator and Chairman of the Department of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art at Brooklyn Museum, Bernard V. Bothmer also recorded this statue in his notes (EG 1703). Bothmer described the piece as ‘Lady or goddess with striated wig; black basalt; nose restored’.

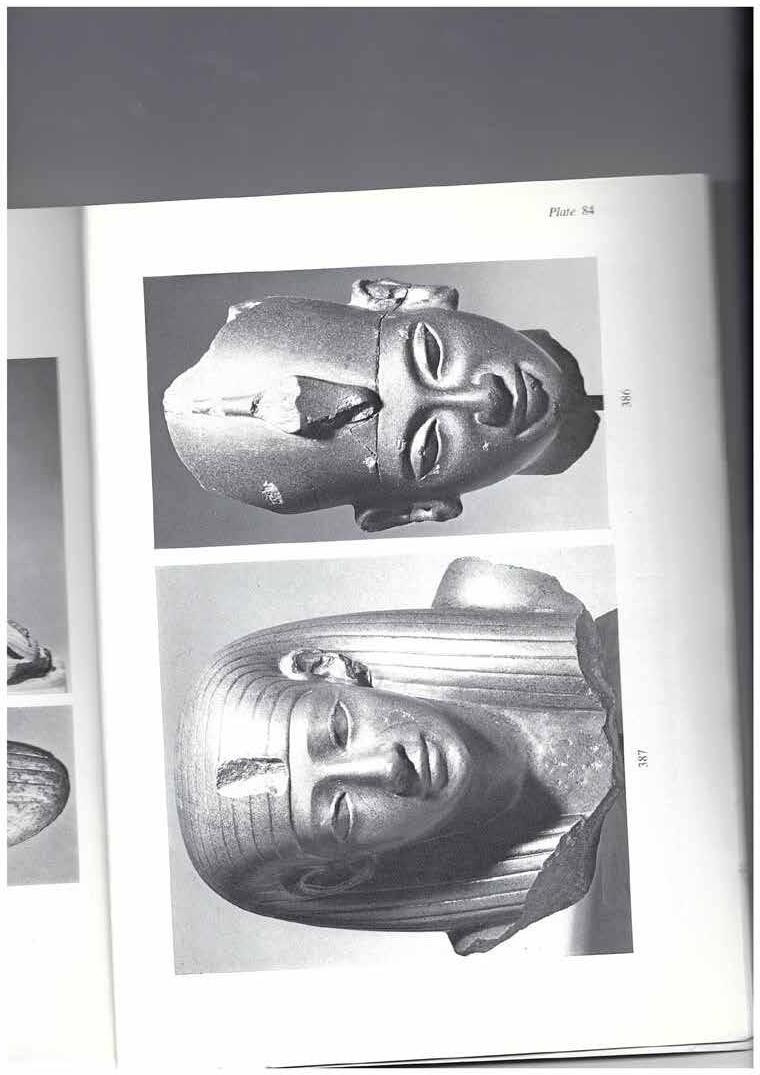

The head resurfaced on the art market in 1978, this time at Christie’s in London. In the 14 June 1978 Fine Antiquities sale, the piece was listed as lot 387, and described as, ‘An Egyptian green schist head of a king (?) or god’, consigned from the London art market. A private collector in the UK bought the piece from this sale, and it was then passed down through their family, disappearing from public knowledge until 2022.

The art-historical research builds a picture of the head’s whereabouts in the twentieth century, but also raises some new questions. Who was the head – a man, a king, a god, or a goddess? What was it made from? And what happened to its nose?

Documented History

The head was first recorded in modern history on the French art market, as Lot 55 in a sale at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, on 12 February 1923. It is pictured on plate II, and described as ‘Tête masculine en basalte noir, d’un beau travail. Le nez est reparé. Socle rouge. Hauteur 0m 24’

(Above) The sale notes of the auctioneer for this sale, André Desvouges, record that this head sold for 2000 francs to a Mr. Miguel

The sale notes of the auctioneer for this sale, André Desvouges, record that this head sold for 2000 francs to a Mr. Miguel, making it one of the most expensive lots in the sale. The name of this buyer appears several times in the sale notes from this sale against several other Egyptian antiquities, including Lots 40, 47, 54, and 57. This suggests he was either a prolific collector or dealer of Egyptian antiquities, or an agent for one.

The meticulous and extensive notes of Bernard V. Bothmer (kept in the Brooklyn Museum archives) recorded pieces he saw, owned, or found of interest. This head is logged in his notes as EG 1703, with a description, the dimensions, comparanda in the Metropolitan Museum, and a handwritten note on the Drouot sale. Interestingly, he goes against the Drouot description, and instead describes the head as a ‘lady or goddess’.

'The meticulous and extensive notes of Bernard V. Bothmer ... recorded pieces he saw, owned, or found of interest. This head is logged in his notes...'

This piece next appears in the Christie’s Fine Antiquities sale on 14 June 1978, as Lot 387. Christie’s have confirmed that the piece had been consigned by a London dealer who is no longer active; meaning the head was in England prior to the sale, by at least 1978. An anonymous private UK collection purchased the head from this sale.

The head was most recently sold in 2022 at Stroud Auctions (now known as Harper Field Auctioneers & Valuers). It had been consigned by a relative of the 1978 buyer. However, it was covered with so much overpainting and wax that the stone itself was hard to assess.

The auction house listed the bust as ancient but misattributed it as a male bust, undated but possibly from the 13th Dynasty. Despite the 1978 Christie's provenance, many collectors and dealers were put off by the presumption that the piece was, in fact, fake. The antiquated 18th-century restoration, along with the more recent 19th- or 20thcentury overpainting caused a lot of confusion amongst scholars and Egyptologists. The carving techniques were hard to assess, we now know that this was due to the wax and overpaint. Similarly, the facial features were not in line with ancient Egyptian work – we have since identified this as the result of the 18th-century restoration.

'Closely connected is the sense of endurance... carried into practice in the laborious work on the hardest rocks. It was for endurance that statues were made of diorite or granite...'

Sir Flinders Petrie, Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt (London, 1910)

Investigating the Provenance and Attribution

Scientific Analysis

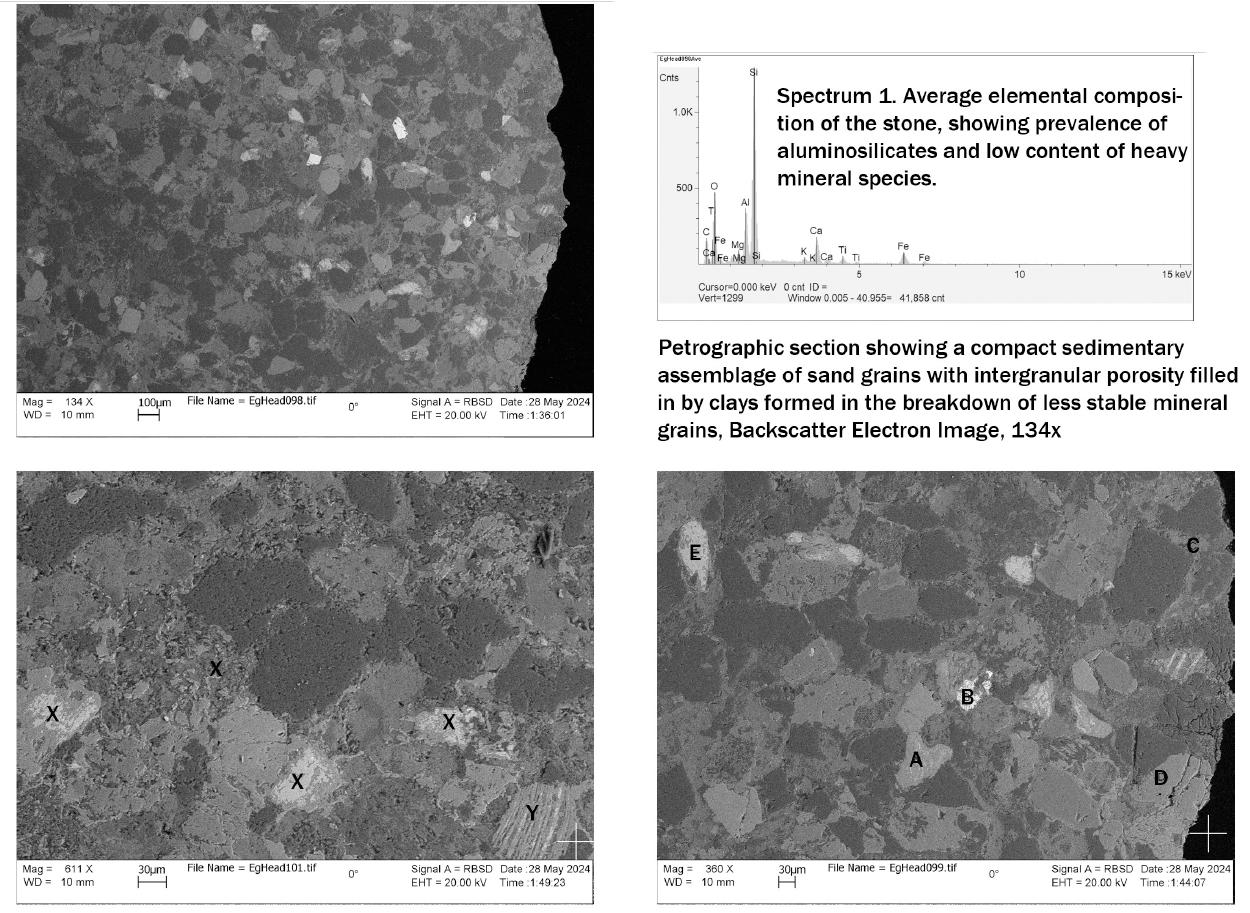

Geologist Dr. James Harrell proposed a new theory about the stone’s identity: metagreywacke, a greenish-grey stone used by the Egyptians for important statues from at least the Middle Kingdom onwards. In pursuit of answers, art conservation scientist John Twilley analysed small samples of the statue through optical petrography, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray spectrometry. The results confirmed that Harrell’s theory was correct, but, intriguingly, they also revealed that the stone samples taken from the restored nose matched those from the rest of the bust. The samples were so close in colour, porosity, and grainsize, that it seems they were crafted from the same piece of stone, despite the nose’s later date.

Further close study revealed traces of sharp chisel blows along the rear of the wig, and parts of the base of the bust – someone had intentionally cut away large chunks of the sculpture. Could it be that the stone was taken from the back and base of the statue to make its new nose?

More clues about this unusual nose job were unearthed when conservationist Kate Bowles carefully removed and documented the restorations. A layer of paint and dark wax were removed from the base of the head, revealing a large section of green resin, which seemed to match the resin on the surface of the nose and chin. With the resin removed, the fragments of stone forming the restored areas could be extracted and examined individually. These fragments were of varying size and shape, and some of them were clearly carved with designs that matched the rest of the bust. We found pieces that lined up with the bottom right end of the wig, the rear of the wig, and the division between the arm and shoulder. The fragments were marked with traces from a reciprocating saw, which were also found on the underside rear of the statue.

The story of the bust was captured in its physical material. A section of stone was cut from the underside rear, then trimmed into a block, from which the new nose was carved. A chisel was then used along the sawn edges, and leftover fragments were mixed with magnesite cement and applied to surface to cover up the traces of the sawing. The cement was carefully colour-matched to the stone, and a final layer of talc mixed with organic resin and pigments was then applied as a cosmetic coating to further conceal this clever restoration.

'...

the stone samples taken from the restored nose matched those from the rest of the bust.'

(Right) Excerpts from the analysis report by John Twilley. Various techniques were used, including optical petrography, which involves examining thin sections of the metagreywacke under a petrographic microscope.

A restoration of this kind would be virtually unthinkable today, when great emphasis is placed on minimally invasive and reversible conservation techniques that try to stay as true to the original object as possible. The restoration was clearly done by someone incredibly skilled in stone carving, and who had great confidence in their ability to recreate ancient Egyptian work – once the stone removed from the underside of the bust had been carved, there would be no material for a second attempt without doing further damage to the statue. No matter the skill of the carver, however, any restoration speaks to the character and tastes of its own time period. To modern eyes, the restored nose simply raised questions about the sculpture’s antiquity. With these restorations removed, it became clear that the piece was truly an ancient Egyptian masterpiece.

Dating the Restoration

The new nose was definitely added before 1923, as it can be seen clearly in the photograph in the Drouot catalogue. In this photo, however, the edges of the inset piece of stone are still visible, as is the damage to the right cheek. The surface layer of talc-based material, must, therefore have been added later to smooth over the surface, before it was next photographed for the 1978 Christie’s sale.

Close comparison of the bust with a statue in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, supplies the next piece of the puzzle. A greywacke bust of a man dated to the end of the fourth century B.C. (Ägyptische Sammlung, INV 20) exhibits clear signs of reworking. Like our bust, the Vienna statue has an unusually shiny and polished surface, and evidence of re-carving. The reworking looks distinctly modern, though clearly trying to follow the style of the Late Period. Most notably, the nose of the Vienna bust is probably not original – the nostrils are too wide for the base of the nose on the face – and yet is carved from the same stone as the rest of the statue. Vivian Davies, previously Keeper at the British Museum, noted that the new nose must have been crafted from fragments of the lower part of the statue.

The bust was sold to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in 1799 by Prince Poniatowski, who probably acquired the piece in Rome shortly before then. It is one of several Egyptian sculptures of the Late Period which were probably brought to Rome in antiquity, and were then “completed” and reworked according to Roman tastes.

Another group of five Egyptian statues, found at the ancient Roman estate of Horti Sallustiani and now in the Gregorian Egyptian Museum, were restored by Francesco Maratti Padovano (c. 16691719) for Pope Clement XI at the start of the 18th century. Maratti crafted new pieces to replace missing sections of the statues, including a new nose and chin for a statue of Queen Tuya (Musei Vaticani, cat. 22678).

As it so closely matches the style of other, securely dated restorations, it seems highly likely that our bust was also given its new nose in 18th-century Italy. It may well have followed the same historical trajectory as these parallels too, being brought to Rome by the ancient Romans to decorate their sanctuaries dedicated to Egyptian cults.

Attributing a Masterpiece

Through close stylistic analysis, Egyptologist Biri Fay has proposed that the bust of a goddess belongs to a series of works attributed to a single artist or workshop by Bernard Bothmer. The hand of this artist, dubbed the Greywacke Master, can be clearly seen in three works found in the Tomb of Psamtik at Saqqara in 1863 and now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo (CG 38358, CG 38884, and JE 38927), as well as in a head of the Goddess Selket, formerly in the collection of Christos G. Bastis. Fay adds to this group a sphinx of Amasis II (Museo Capitolino, Rome, inv. 35) and the greywacke goddess. All of these pieces exhibit the same fine quality of carving, overall proportions, and smooth surface, that mark out the works of this master sculptor. This attribution also helps to firmly date the bust of the goddess to the reign of King Amasis II (r. 570-526 B.C.) in the 26th Dynasty.

'Although there are many questions still left to be explored, the answers revealed through our multidisciplinary research demonstrate the value of such a collaborative approach.'

Understanding the History

The combination of scientific examination and art-historical and Egyptological research thus reveals a great deal about the history of the bust. After Amasis II’s death and the defeat of his son and successor by Cambyses II, the invading Persians destroyed much of the Saite Dynasty’s architectural and cultural projects. The face and lower of half of this bust were probably intentionally damaged during this period, along with many other statues.

But not all of the damage to the bust seems to have been enacted with the intention to destroy. A small incised rectangle on the front of the wig shows where the uraeus was removed very carefully, as was some kind of ornament around the neck, now attested by small pick marks left where it was removed. The ears and parts of the wig were also reshaped at some point. These changes suggest that the bust was altered in order to represent a new subject, before it was damaged more dramatically. Reusing statues in this way was a common practice in ancient Egypt, as fine materials were costly and scarce. Moreover, as this bust was carved by a skilled master sculptor, repurposing it would associate its fineness with the new subject.

This explains why the bust has been described in so many ways. Without the uraeus or other identifying emblems it is hard to pinpoint exactly who it was designed to embody, both at first, and after the uraeus was removed. The initial presence of a uraeus and tripartite wig means it must have represented either a royal or divine subject originally. The tripartite wig was much more commonly seen on women of the Late Period, and can be seen on images of elite unmarried women, queens, and goddesses. As it was so finely crafted, and the other works by the Greywacke Master were all dedicated at the Temple of Sais, it follows that this bust would have also been displayed there. This suggests that the bust probably represented one of the goddesses of the ancient Egyptian pantheon when it was first made, as stated by Bothmer.

Although there are many questions still left to be explored, the answers revealed through our multidisciplinary research demonstrate the value of such a collaborative approach. Through scientific and art-historical study, this bust has been restored from an unknown, un-understood, and uncelebrated piece of lost history, to its rightful place as the work of a master craftsman, made to adorn the main sanctuary of the Saite Pharaohs. Based on our research, we have chosen to non-invasively reattach the 18th-century restorations, as they represent a key part of the bust’s story. Despite its long journey through tumultuous times and changing attitudes towards sculpture, the Greywacke Goddess has returned as one of the masterpieces of its age.

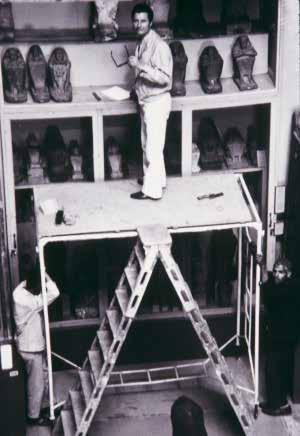

Bernard V. Bothmer (1912-1993)

The eldest son of Wilhelm Friedrich Franz Karl von Bothmer, of a Hanoverian noble family, and Marie Julie Auguste Karoline Baroness von und zu Egloffstein, Bernhard Wilhelm von Bothmer was born in Charlottenburg, Berlin, on 13 October 1912. He studied at the Universities of Berlin and Bonn, before he was invited to join the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin by then-director of the Egyptian Museum, Heinrich Schäfer, in 1932. He worked as a curatorial assistant and developed his passion for Egyptian art under the tutelage of Schäfer and Hans-Wolfgang Müller, who also introduced him to photographing ancient Egyptian artworks. Bothmer was an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime, and escaped to France and then Switzerland just before the outbreak of the Second World War. He emigrated to the United States in October 1941, and worked for the Office of War Information and the War Department, and later in army intelligence in Europe until 1946. He dropped the ‘von’ and the ‘h’ from his first name when becoming an American citizen, as a symbolic protest against Nazism.

Bothmer was appointed to the role of assistant curator in the Department of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1946. He worked here until 1955, and began his Egyptological publishing career with two articles discussing the identification of the scattered remains of ancient monuments – a subject which he returned to throughout his career. Whilst at Boston, Bothmer developed his main scholarly focus on Late Period Egyptian sculpture, and began compiling his Corpus of Late Egyptian Sculpture. This archive would come to include thousands of photographs and other documentation on Late Period sculptures, including his record on the Greywacke Goddess. Müller also consulted as the Corpus’s specialist on royal sculpture, with Herman de Meulenaere of Brussels as the expert on inscribed material.

Notes in the files of Bernard V. Bothmer (1912-1993) recording the Greywacke Goddess as EG 1703, Brooklyn Museum Archives, New York

'...every time we are confronted with a partial, or fragmentary, piece of sculpture, we ask ourselves what the missing portion may have looked like, or what the lost part of an inscription may have contained.'

Bernard V. Bothmer, Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period, exhibition catalogue, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, 18 October 1960-9 January 1961, p. xiii.

After Boston, Bothmer worked as Director of the American Research Center in Egypt from 1954-56, and as Fulbright resident fellow in Cairo from 1954-6 and 1963-4. He became associate curator in the Department of Ancient Art at The Brooklyn Museum, New York in 1956. In 1960, he curated a special exhibition on Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period: 700 B.C. to A.D. 100; the exhibition catalogue remains the seminal text on Late Period statuary. The stylistic analysis used to date uninscribed pieces in this exhibition was a huge step in the field of Egyptology – only a handful of these objects have required redating in the sixty years since. This analysis allowed the dating of works such as the two goddesses by the Greywacke Master and, by extension, of the Greywacke Goddess.

In 1963 Bothmer was promoted to the position of curator and became chairman of the department in 1979. He would remain associated with the Brooklyn Museum until his retirement in 1983. Bothmer continued to teach at various American universities until a few weeks before his death in 1993, and helped to found New York University’s Mendes expedition, supporting the eight seasons of archaeological fieldwork undertaken at Mendes and Thmuis between 1964 and 1980. He remained a major figure in Egyptology throughout his long and storied career.

Restoration of the Greywacke Goddess

The de-restoration of the Greywacke Goddess was done strategically in multiple stages.

The first step was to remove a thick layer of dark wax and overpainting from the surface. This allowed the colour of the stone and the condition of the carved surface to be properly assessed, leading to the identification of areas of 18th-century restoration and infill.

Dr. James Harrell was then able to define the stone as being metagreywacke, specifically ‘Wadi Hammamat metagraywacke’.

UV-assessment showed that potentially modern infill materials had been used around the 18th-century carved nose and lips and on other areas. The decision was made to fully remove all restoration to better understand the reason for this, and to evaluate the full extent of the ancient damage.

Once all restoration was removed, art conservation scientist John Twilley undertook a thorough investigation into the bust. It was clearly evidenced that restoration had been made to ancient Egyptian damage (either accidental or iconoclastic) using stone from the bust itself. This technique of borrowing stone from a donor site on the sculpture and masterfully carving a replacement was practiced by top restoration workshops of 18th-century Italy, a technique that would never be used today.

After all art-historical and scientific assessments had been completed, the decision was made to re-attach the 18th century nose and lips.

Following our research into the restoration workshops of Italy and the skill it would have taken to carve such a fine replacement section, it was agreed that the nose section was important to the bust’s history and physical journey, and should, therefore, remain.

The areas illustrated in grey show the damage done in antiquity, and their relation to where the 18th-century carved nose and chin now sit.

The most substantial damage to the Greywacke Goddess is to the face, running from the bridge of the nose in a triangular form encompassing the nose, lips and chin. The areas in grey illustrated above show areas of damage done in antiquity and their relation to where the 18thcentury carved nose and chin now sit. This damage was most likely done at different times in antiquity. Egyptians often repurposed sculptures for new patrons or royalty; changes in facial features and fashion meant that noses and decorative elements, for instance, were re-carved or cut off.

It is thought that this bust originally dates to the Saite Dynasty. When Amasis II's rule fell to the Persian King Cambyses in 525 B.C., the invading forces destroyed many of Egypt’s temples including sculptures.

The historical journey of the bust, and its timeline of restorations can be estimated by assessing the style and techniques used to alter its appearance. According to Egyptologist Biri Fay, the largest alterations are clearly 18th-century and were performed by a master worker. It is obvious that this statue has been prized for centuries, with adaptations and expensive restorations made over time. A projected timeline can be followed as such:

This bust was carved in c. 550 B.C. during the reign of Amasis II (570526 B.C). A raised decorative area on the chest was “erased” from the finished sculpture, leaving visible picked marks, which differ noticeably from the polished surrounding stone.

Egypt, c. 570-526 B.C

This bust was most likely among the many Egyptian sculptures that were imported to Italy by the ancient Romans in order to decorate their Egyptianising sanctuaries and shrines. The bust has many similarities to the statues that adorned Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.

Roman Period, c. 30 B.C.-641 A.D.

Egypt, c. 525 B.C.

Following King Cambyses’s victory over the final Saite ruler, many of Egypt’s temples and statues (including this bust) were destroyed as part of a coordinated campaign of iconoclasm.

Italy (Rome), 18th Century.

During the 18th century, fashions changed and ancient artworks hidden in the ruins of Roman sites were brought to light. It is during this time that the master restorer would have worked on the damaged bust.

The bust appears for sale in Paris, 12th February 1923. The 18thcentury restorations are visible on the nose, chin and mouth. The cheek is also visibly damaged. It is also possible that at this point, the bust had undergone more recent 20thcentury restoration and been covered with a dark overpaint.

Paris, France, 12th February 1923.

The bust appears on the UK art market, seemingly in similar condition to 1978. The surface is still covered in overpainting and the 18th-century attachments are still present. It seems the bust is still mounted on the same base as it was since 1978.

Gloucestershire, UK, 12th January 2022

London, UK, 14th June 1978.

The bust is listed for sale at Christie’s, London, on 14th June 1978. The edges and back of the restored nose have been smoothed, and the damage to the cheek and the tip of the nose have been repaired with new infill material.

London, UK, February 2023- Present

The Greywacke Goddess was acquired by David Aaron Ltd and our investigations into its condition and previous restorations began. All restoration, including that from the 18th- and 19th-centuries, was removed in stages for analysis. The 18th-century elements have since been sympathetically reattached as they are an important part of the history of the artwork.

1) A thick layer of dark waxy overpaint was carefully removed in stages to reveal the true surface condition and stone colour. After this, the 18th-century nose and lips, along with surrounding infill, were detached and studied, revealing that repairs had been made using stone from the bust itself.

2) Following scientific and art-historical analysis, the 18th-century nose was sympathetically reattached as a meaningful part of the sculpture’s history.

3) The reattached nose was originally carved from a section of stone taken from the back of the bust itself, a sophisticated method used by leading Italian workshops of the 18th- century. Though such a practice would be unacceptable today, the quality, historical value of the carving and the fact that it was most likely done by a master Italian restorer, along with its role in the object's physical story, justified its reinstatement as a key part of the artwork’s identity.

Assessing the Damage

Smashing Statues

What sets the bust of a goddess apart from the three sculptures produced for Psamtik is its state of preservation. The statues of Osiris, Isis, and Hathor with Psamtik are all in near-perfect condition. All other greywacke statues from this period were damaged after Amasis’s death and the brief reign of his son, when Cambyses II held Egypt. It has been suggested that these statues were not originally created for the nonroyal tomb of Psamtik, but were instead intended for a temple. There is plenty of evidence for greywacke statues that were found in or known to have originated from the Temple of Neith at Sais. This would mean that the three sculptures must have been removed from the temple by Psamtik when he realized that they would be at risk from the invading Persians. Burying them in a cache ensured they remained safely out of harm’s way. Psamtik must have considered these three statues, of the divine king and queen and of himself being protected, to be the most important of those he commissioned. The other works by the Greywacke Master, such as this bust and those of Isis and Selket, must have been left behind at Sais and smashed.

Accident or Iconoclasm?

Today, many ancient Egyptian statues are missing their noses. While it is true that the nose, as the furthest projecting facial feature, was particularly vulnerable to damage from erosion or accidents, many of the nasal removals occurred in antiquity. Archaeologists are still discovering statues in situ that have missing noses, suggesting that the damage took place centuries ago.

Ancient Egyptians believed that souls could inhabit images or objects. Inscriptions and texts from temples and tombs describe certain actions that should be performed by living worshippers in order to furnish the souls of those represented in the wall carvings and statues. So too, would damaging an image cause harm to those represented. Texts and inscriptions forbid and promise punishment to those who dare to damage tomb statuary, but this did not stop ancient looters. Some scholars even believe that looters intentionally broke statues in order to prevent the tomb owner’s soul from targeting them. Removing the nose of a statue would prevent the soul from ‘breathing’ and so prevent it from interacting with the world of the living.

The goddess bust with 18thcentury restorations removed, revealing the damage to the nose, lips and chin. Possibly an act of iconoclasm.

‘As for anyone in this entire land who may do an injurious or evil thing to your statues … my majesty does not permit that their property nor that of their fathers remain with them, nor that they join their spirits in the necropolis, nor that they remain among the living.’

Royal decree found at Coptos, Egypt, dated to the First Intermediate Period (c. 2170-2008 B.C.)

Large-scale campaigns of iconoclasm were carried out against the carved images and names of pharaohs who had fallen from grace. Famous rulers who were targeted for erasure after their deaths include the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (r. c. 1479-1458 B.C.) and the radically monotheistic Akhenaten (r. c. 1353-1336 B.C.).

After Cambyses II defeated the Saite Dynasty in 525 B.C., he ordered the destruction of temples throughout Egypt, including the Temple at Sais, the home and burial place of the dynasty’s rulers. Hundreds of statues were smashed as a result of this, and the sites of the once-grand temples were left in ruins.

It was most likely during this campaign of destruction that the bust of the goddess was broken from the rest of its body and the lower portion of the face smashed off. Similar damage was enacted on many sculptures of Amasis himself, including the sphinx now in the Museo Capitolino, Rome.

Reuse and Recycle

However, not all of the damage to the bust fits the pattern of iconoclasm. The uraeus, for instance, was removed with great care: the edges of the recess at the front of the wig are cleanly cut and encompass the smallest area possible. The eyes, normally one of the first targets of ancient iconoclasm, have been left intact, in what must have been a deliberate choice. Combined with the reshaping of the ears and parts of the wig, these changes may have been made in order to display the statue with different headgear and a new emblem at the forehead.

A slightly raised area with small picked marks on the goddess’s chest suggests that something else was also removed from the bust in antiquity. The remains of an ornament of some kind appears to encircle the base of the goddess’s neck. This pattern of marks is frequently seen when official jewellery or inscriptions have been removed from ancient statues, often prompted by a change in the sitter’s status or the accession of a new ruler. In some cases, these marks are present when a precious metal has been picked off to be melted down and reused elsewhere.

A repurposing of this kind must have taken place before the more aggressive damage to the bust occurred, suggesting that it was carried out during the reign of Amasis. However, a firm explanation for who made these alterations and why has yet to be discovered.

18th-Century Restorations

Although the restoration to the nose of this bust seems shocking to us today, in previous periods it was not only common, but expected, that missing portions of sculptures would be recreated by contemporary sculptors.

In the second half of the 18th-century, the popularity of the Grand Tour among the wealthy generated a huge demand for antiquities, and antiquity-inspired artworks. In response to this demand, an industry grew up around repairing and restoring ancient sculpture. As well as providing a source of income for artists and their workshops, this industry created work for labourers, shippers, and antiquities dealers. From around 1750 and into the early 19th-century, the majority of ancient works traded in Europe underwent restoration of a kind that would never be countenanced today.

Treatises from the 18th-century record the various techniques that could, and should, be used to restore ancient statues. It was recommended that the surface be cleaned and scoured with abrasives and tools, and any broken sections reattached or, alternatively, broken and corroded surfaces cut away. Missing portions could be replaced with newly carved sections, which were frequently attached using holes drilled into the original stone to insert metal pins. The ancient fragments could also be reshaped to better fit with the modern additions. Entirely new sculptures were even crafted from disparate excavated fragments.

‘... data per esempio una figura che sia senza testa, braccia o altro, vestita con panneggio in parte mancante, e con qualche indizio d’emblema troncato, conviene speculare da questo resto, e indovinare, se sia possible, il soggetto che essa rappresentava, e l’andamento del moto delle parti mancanti.’

‘... given for example a figure that is without a head, arms or anything else, dressed with partly missing drapery, and with some traces of a truncated emblem, it is appropriate to speculate from this remainder, and guess, if possible, the subject it represented, and the movement of the missing parts.’

Francesco Carradori, Istruzione elementare per gli studiosi della scultura (Florence, 1802), pp. 27-28.

Invoices submitted by a number of restorers in 17th-century Rome frequently charged their clients for ‘commettere, impernare, attaccare, stuccare’, ‘adjusting, pinning, joining, filling’. The texts also advise on the best way to disguise restorations, advocating for the use of plaster and hot dye made from chimney soot boiled in urine or tobacco juice to match the colour of the stone.

Restoration was a highly praised artform of its own during this period, with commentators ranking different artists based on their skills at “completing” ancient works. Artists would even compete against each other to see who could best restore a given classical sculpture. When the Laocoön was excavated, it was missing fragments of the limbs and the snake, so a competition was held to see which artists could best suggest how it was posed originally. The winner of this contest, Jacopo Sansovino, had his model cast in bronze. But the King of France was not satisfied with this example, and commissioned Baccio Bandinelli to craft another completed version, which could surpass the original. Bandinelli’s cast was so admired that the Pope refused to send it to France and instead kept it for Florence. The idea of a restored work outshining the original was also not uncommon; Pietro Bracci’s bronze cast of the Farnese Mercury was described in a 1758 letter by John Parker, agent to the first Earl of Charlemont, as ‘much better than the original’.

Another famous intervention undertaken directly on an ancient sculpture is Bernini’s work on the Ludovisi Ares. As well as replacing the right foot, Bernini also added elements that appear unignorably Baroque to modern eyes, such as the cherub and sword hilt. Moving forward into the twentieth-century, restorations continue to reflect the tastes of their own times. The statue of Queen Hatshepsut in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, (29.3.2) has undergone three major restorations since its excavation in 1929. In the 1930s, the separate fragments were fixed together, and all the losses filled with painted plaster to create the appearance of a complete and unbroken statue. In 1979, these plaster fills were removed and replaced with infills that, although still reflecting an intact statue, were painted a slightly different colour and recessed from the surface of the ancient stone to create a visual distinction between the original and restored elements. However, this left a large and jarring gash across the face of the queen. A final restoration in 1993 sought to rectify this by combining respect of the object’s integrity and age with a desire to show the beauty of the statue in full.

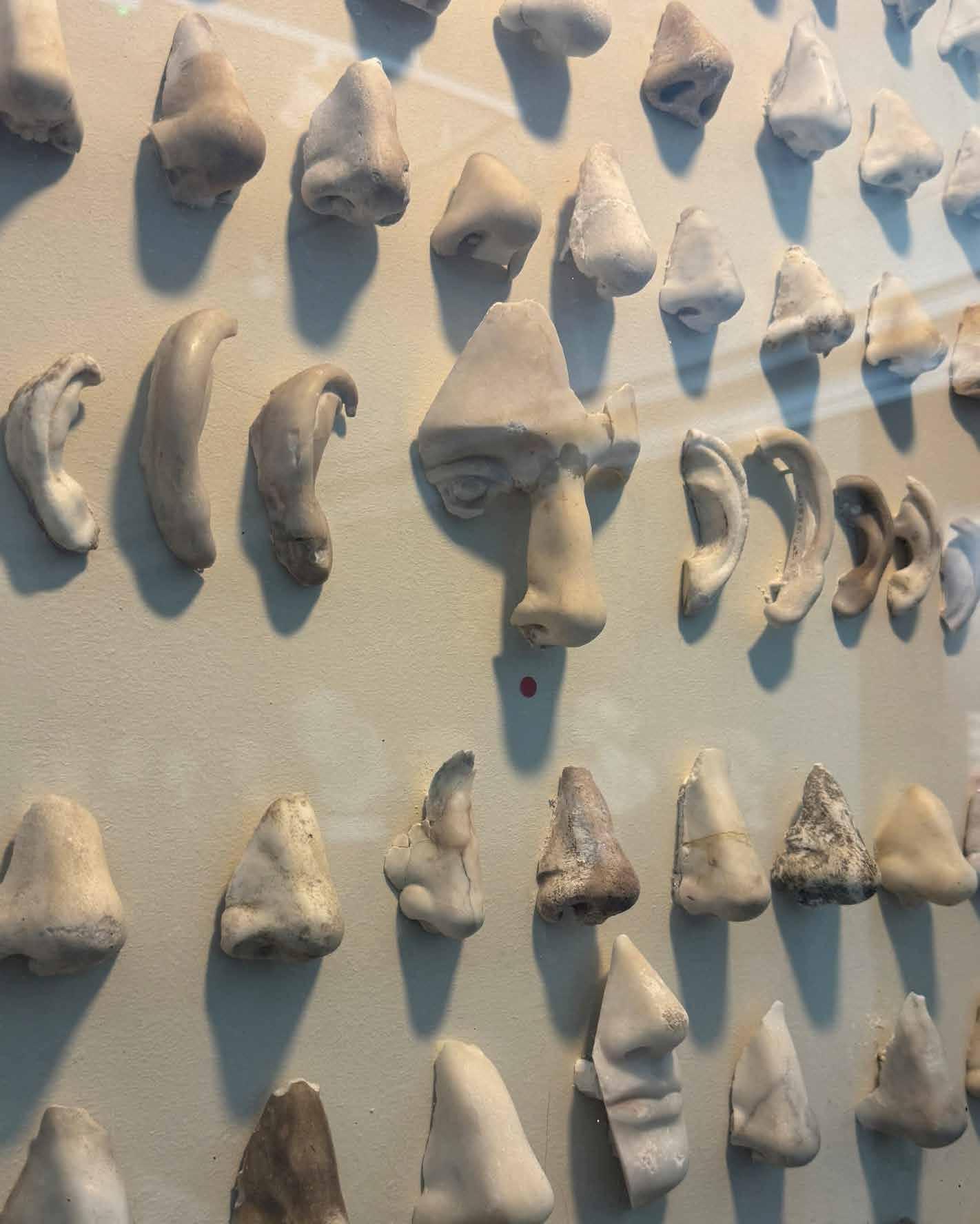

Under Our Noses

With changing tastes and changing times, there is an ongoing debate as to how to best handle modern restorations of ancient works. Museums are increasingly opting to remove restorations that change large aspects of a piece’s appearance. For instance, a head in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, (545) was previously given a new nose and chin, which have now been removed.

In fact, there were so many nose jobs of this kind, that the museum has now created a display case filled with the removed restorations: the Nasothek.

The question of whether to remove or to keep historical restorations, which comprise part of an object’s history over time and a record of its earlier owners and provenance, is not an easy one to answer. Both options can be seen as their own kind of authenticity, and their own way of staying ‘true’ to the story of an object.

'The gods are in all things, but it is in stone that they endure, silent and immutable, as time itself bends before their gaze.'

Identifying the Stone

The stone from which this statue is made was incorrectly identified until 2023. In 1923, this head was described by Hotel Drouot as ‘basalte noir’, black basalt, and by Christie’s in 1978 as ‘green schist’. However, scientific analysis has determined conclusively that this statue is carved from Wadi Hammamat metagreywacke. Its earlier misidentification is not uncommon – historical archaeological literature frequently confused metagreywacke for schist, slate, and basalt.

Geologist Dr. James Harrell determined that this statue is not made of basalt based on a number of reasons. While basalt from some parts of the world can have a greenish hue, the kind found in Egypt never does. Basalt also almost always contains some magnetite, so responds strongly to magnets, whereas metagreywacke has no magnetite and so is not magnetic. Metagreywacke usually contains a little calcite, so will effervesce when touched by dilute hydrochloric acid; basalt lacks calcite and will not react to acid. With a strong magnifying glass you can see the sand and/or silt grains in the metagreywacke, which differs greatly from the crystalline texture of basalt. Moreover, metagreywacke commonly contains pebbles, which can be clearly seen within the stone of this sculpture. Optical petrography, scanning electron miscopy, and X-ray spectrometry tests run on samples of the stone confirmed that this was the case.

Metagreywacke

Metagreywacke (also known as greywacke) is a variety of sandstone, which is characterised by its hardness (6-7 on Mohs scale), dark colour, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and other small rock fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. A mildly metamorphosed sedimentary rock, metagreywacke’s formation could originally not be explained by geologists. The gravel, sand, and mud found within metagreywacke should not normally be laid down together, and must have been brought together by submarine avalanches or strong turbidity currents churning the sediments together before they were deposited. Because of this, deposits of metagreywacke are only found on the edges of continental shelves, at the bottoms of oceanic trenches, and at the bases of mountain formational areas, where these avalanches and turbidity currents occurred. Deposits are found in Wales, the south of Scotland, the Longford-Down Massif in Ireland, and the Lake District in England. Metagreywacke also composes the majority of the main South Alps in New Zealand, and has been found in the Ecca Group in South Africa. In Egypt, metagreywacke is found in parts of the Eastern Desert.

Greywacke differs from fine-grained sandstone, which sometimes contains pebbles, as it contains three varieties of finergrained mudrock: siltstone, mudstone, and claystone. Although geologists only acknowledge the one variety of sandstone as greywacke, Egyptologists have long used the term to refer to all mudrocks with the

same clay-rich matrix. As the original clay minerals have been replaced by chlorite, epidote, and sericite due to metamorphism over time, the rock is also known as metagreywacke.

Due to its fine grain size and resistance to fracturing, metagreywacke is highly suitable for use in sculpture, as it can be carved into fine and intricate details without crumbling. It is the same stone as the basanites used by the Romans, and the pietra bekhen, basanite, and basalte verde antico used by traditional Italian stonecutters. In ancient Egypt, metagreywacke was known as bekhenstone, from at least the Middle Kingdom onwards, and early dynastic Egyptian vessels represent the earliest known use of metagreywacke in history. The green hue of metagreywacke may have been part of its appeal to ancient Egyptians, as green was associated with vegetation and growth, and, therefore, with joy and delight.

Wadi Hammamat

The only known source of metagreywacke in Egypt was the quarry at Wadi Hammamat, a dry river bed in the Eastern Desert, roughly halfway between Al-Qusayr and Qena. Its location between the ancient city of Koptos (present-day Qift) and Al-Qusayr on the Red Sea, placed it on the major trading route from Thebes to the Red Sea, and onwards to the Silk Road. The wadi (valley) exposed Precambrian rocks from the Arabian-Nubian Shield, meaning basalts, schists, metagreywacke, and gold-containing quartz were all accessible in this region. The natural cleavage of the metagreywacke meant that blocks could be separated from the ground using stone hammers. Ancient Egyptians sent expeditions to quarry the stone at Wadi Hammamat from at least as early as 3200 B.C. until about 250 A.D.. The famous Narmer Palette, produced in circa 3200-3000 B.C. and containing some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions as well as one of the earliest depictions of an Egyptian king, was carved from metagreywacke quarried at Wadi Hammamat.

There were two ancient quarries in Wadi Hammamat, approximately one kilometre apart, from which over 10,000 tonnes of stone was worked. The stone would then be transported over 90 kilometres through the desert, and finally shipped along the river Nile to its destination. The remains of unfinished or broken sarcophagi still in the valley reveal that the stone was worked at least partially in situ at the quarry site, before being transported. Almost 600 rock inscriptions, covering a period from Predynastic times until the late Roman period, document the quarrying activity in the region. These inscriptions are concentrated in a stretch of only about two kilometres in the wadi, demonstrating just how unique and important this site was; by the New Kingdom, it was referred to by the new topographic term ‘mountain of bekhen’.

One of the earliest pieces of evidence of quarrying at Wadi Hammamat is a graffito containing a serekh (king’s name) of the Early Dynastic King Narmer, inscribed on a rock in the Wadi el-Qash (an offshoot of the main valley). Eighty other inscriptions can be dated accurately to the reign of Pepi I Meryre (r. c. 2332-c. 2283 B.C.), recording expeditions gathering metagreywacke for use in temple statuary. Several other Old Kingdom pharaohs are represented amongst the inscriptions, including Khufu (r. c. 2589-c. 2566 B.C.), Djedefre (r. c. 2566-c. 2588 B.C.), Khafre (r. c. 2558-c. 2532 B.C.), Menkaure (r. c. 2532-c. 2503 B.C.), Sahure (r. c. 2491-c. 2477 B.C.), Unas (r. c. 2375-c. 2345 B.C.), and Merenre Nemtyemsaf (r. c. 2283-2278 B.C.).

Ancient Egyptians sent expeditions to quarry the stone at Wadi Hammamat from at least as early as 3200 B.C.

Despite the upheaval of the First Intermediate Period, Wadi Hammamat remained in use, with small graffiti referencing rulers of the 10th Dynasty, before it was reopened in the 11th Dynasty with large expeditions sent there throughout the Middle Kingdom. Vizier Amenemhat (most likely the later pharaoh Amenemhat I) records a mission of 10,000 men sent to quarry metagreywacke for the sarcophagus of Pharaoh Nebwawyre Mentuhotep IV (r. 1997-1991 B.C.). The block of stone selected for this purpose was marked by an auspicious omen, when a gazelle gave birth atop it. Senusret I (r. 19711926 B.C.) sent roughly 18,660 workers to the quarry to acquire stone for 60 sphinxes and 150 statues, with two large rock stele recording the administrative details of the expedition, such as the personnel and the rations issued. Surprisingly few New Kingdom inscriptions are found in the quarry, suggesting an alternate, more northerly, route may have been used to cross the Eastern Desert in this period. The reign of Ramesses IV (r. 1155-1149 B.C.) however, marked a huge amount of activity in the quarry. In the first three years of his reign, Ramesses sent four separate missions to Wadi Hammamat to procure stone for his monuments in Thebes. The most extensive mission occurred in the third year of his reign, when the high priest of Amun was sent with a large workforce to quarry stone for the Theban necropolis. Graffiti has also been found from the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period. Inscriptions and cartouches relating to kings Psamtek I, Necho II, and Psamtek II of the 26th Dynasty demonstrate that the quarry was still very much in use at the time this statue was produced. The hieroglyphic inscriptions continue into the 30th Dynasty, and are then succeeded by demotic and Greek texts from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

The Turin Mining Papyrus

The oldest known topographical sketch map, which predates by nearly three millennia the next oldest known geological maps, is identified as the ‘Turin Mining Papyrus’. It records the land around Wadi Hammamat, including gold and silver mines, and the location of the metagreywacke quarry. The map is colour coded to represent the different materials found at each site: the ‘mountains of gold’ are painted in rose, and brown bands on their slopes represent veins of quartz embedded in the granite, while metagreywacke and siltstone are shown in greenishgrey. The map was drawn by the scribe Amennakhte, son of Ipuy, who was commissioned by Ramesses IV on the expedition in his third year of rule. The map shows part of the route through the valley, as well as identifying features such as hills, and marks the distances between the various quarries and mines.

The black rectilinear forms visible along the route where the quarry is marked on the map seem to be representations of blocks of metagreywacke. The associated texts on the map give the dimensions of quarried blocks, and two other passages on the map discuss the hauling of stone blocks or mention ‘bekheny’.

‘[…] bekhen-stone, found in the mountain of the bekhen-stone. [His Majesty] L.H.P. [sent out] the high officials […], in order to bring back a statue of bekhen-stone to Egypt. One put it at the Place of Truth next to the temple of Wsr-m3r .t-R’w stp.nR’w (Ramesses II), the Great God. [One(?)] left it behind at the compound of the tomb, being their unfinished. Work of year 6.’

Inscription on a fragment of the Turin Mining Papyrus, which records how metagreywacke was quarried for the Theban necropolis under Ramesses IV.

Sculpting

History: The Fascination with Greywacke

Timeline of Important Greywacke Sculpture in International Museums

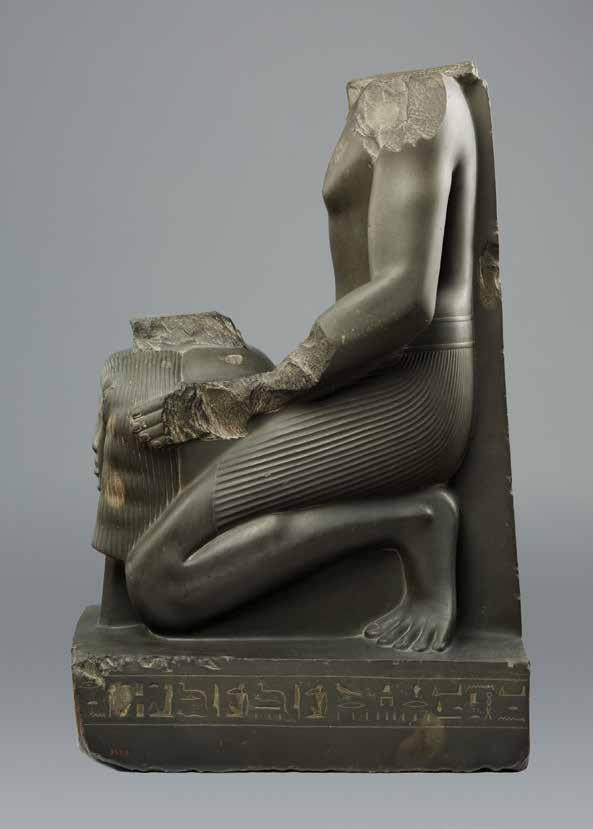

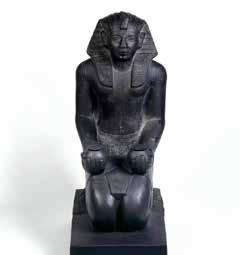

The Triads of Menkaure C. 2532-2503 B.C.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo (JE 40678, JE 46499, JE 40679), and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (11.3147)

Narmer Palette C. 3200-3000 B.C.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo (CG 14716)

Statuette of Amenemhat III C. 1855-1810 B.C.

Musée du Louvre, Paris (N 464)

Statue of Amenhotep II

C. 1427-1401 B.C.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo (JE 36680)

Statue of King Khasekhemwy C. 2690 B.C.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo (JE 32161)

Kneeling Statue of Pepy I C. 2338-2298 B.C.

The Brooklyn Museum, New York (39.121)

Seated Statue of King Senwosret I C. 1961-1917 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (25.6)

Head of Ankhkhonsu C. 664-525 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (04.1841)

The Boston Green Head 380-332 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (04.1749)

Agrippina the Younger 54-59 A.D.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (753)

Bust of Scipio C. 17th Century A.D. Post-Renaissance

Fondazione Torlonia, Rome (MT 346)

Statue of Ramesses IV C. 1155-1149 B.C.

The British Museum, London (EA1816)

Statue of Harbes, called Psamtiknefer, son of Ptahhotep 595-589 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (19.2.2)

Head of Ptolemy II C. 280 B.C. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (22.109)

Statue of Aphrodite Late 1st-Early 2nd Century A.D. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (28.57.6)

‘Celles-ci

sont l’œuvre d’un practician extraordinairement habile et adroit; elles sont polies et achevées comme tout ce qui appartient à cet art patient et délicat qu’on a nommé l’art saïtique’

‘These are the work of an extraordinarily skilful and adroit practitioner; they are polished and finished like everything that belongs to that patient and delicate art that has been called the Saïtic art’

The Greywacke Master

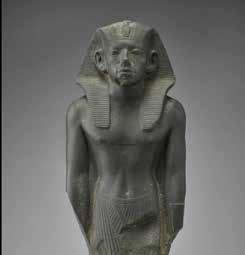

In 1863, French archaeologist and Egyptologist Auguste Mariette (1821-1881) found a cache of sculptures buried in a deep pit in the Tomb of Psamtik at Saqqara. These three greywacke sculptures were found in almost pristine condition, alongside an ushabti of King Nectanebo II and the sarcophagus of an unknown queen. The inscriptions on the statues can be philologically and epigraphically dated to the time of Amasis, and Psamtik’s title has been translated as "The Overseer of Sealers and Governor of the Palace under Amasis". The statues represent the god Osiris, the goddess Isis, and the goddess Hathor in bovine form standing protectively over the figure of Psamtik. As early as 1872, the commonalities between these three statues were noted by Mariette, who felt they must have been carved by one extraordinarily talented sculptor.

In 1960, Bernard V. Bothmer, then Curator of the Department of Egyptian and Classical Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, also grouped these statues by their shared artist, and added a fourth to the group – a statue of the goddess Selket in the Christos G. Bastis collection. Bothmer notes that the images of the two goddesses, Isis and Selket, are ‘line for line and trait for trait identical’ and so must have been produced in the same workshop from the same model (Bernard V. Bothmer, Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period, exhibition catalogue, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, 18 October 1960-9 January 1961, p. 64).

In 1987, Bothmer attributed another statue to this workshop, recognising the same facial features on the bust of the goddess Isis in the Museo Nazionale Archeologico, Florence (313), which were ‘undoubtedly fashioned by the same sculptor as the head of Selket’ (Bernard V. Bothmer, Antiquities from the Christos G. Bastis Collection (Mainz, 1987), no. 21). This sculpture can also be securely dated to the reign of King Amasis, as the inscription down the back pillar features the prenomen and nomen of the pharaoh. So too, is it roughly the same size as the other sculptures in the group.

A New Work by the Master

When Bothmer recorded the greywacke bust of a goddess in his archives (EG 1703), he had not seen it in person but only been made aware of it through the image in the 1923 Drouot catalogue. This provides a possible reason why he drew the comparison between this work and the Ptolemaic head attributed to Arsinoe II, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (38.10). Certain key features of Ptolemaic portraits are lacking in the greywacke bust; Ptolemaic sculptures are united by their rounded foreheads, and eyebrows which peak at the centre and sweep downwards towards the ears.

The greywacke goddess does, however, have a marked stylistic similarity to the 26th Dynasty statues attributed to the Greywacke Master. As well as the overall proportions, fine carving, and smoothed surface, the eyebrows are carved as a simple ridge above the eyes that meets the nose at near-right angles and gradually decreases in depth towards the outer edges of the face. Biri Fay has made a strong case that this deity may well be the sixth member of the group carved by the talented sculptor in the reign of Amasis. So too, does she argue that the sphinx of Amasis II in the Museo Capitolino, Rome, must have been carved by this master.

The Temple of Neith at Sais

It appears that the greywacke goddess was probably part of a sculptural program designed for the Temple of Neith at Sais, a major cult centre during the 26th Dynasty.

Located on the Western Nile Delta on the Canopic branch of the Nile, the ancient city of Sa, or Sais in Greek, was the capital city of the 26th Dynasty. Sais had been an important political and economic centre further back in Egypt’s past, serving as the centre of power for Tefnakhte – ‘Great Chief of the West’ – in circa 727 B.C.. The city’s position provided great control over the whole Western delta, with access to agriculture, sea trade down the western branch of the Nile to the coast, and possibly trade routes to the oases. It also had a thriving linen industry, and was in close proximity to the Wadi Natrun, which produced the material for mummification. The Saite rulers of the 26th Dynasty commissioned large building projects in the city, such that Greek historian Herodotus was in awe at the size and quality of the statues, temples, and palaces he saw when he visited. Many artworks produced during Amasis’s reign can be reliably traced back to Sais, with many officials following the example set by the pharaoh.

Sais was also the centre of the cult of the goddess Neith, one of the earliest recorded gods in the Egyptian pantheon. Goddess of both war and weaving, she was the patron goddess of Sais and of the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. According to the Iunyt (Esna) cosmology, Neith was the creator of the world and the mother of the sun, Ra, making her the mother of all the gods. Her temple at Sais was a key centre of pilgrimage in the Late Period, and possibly much earlier: a wooden label inscribed with the name of Hor-Aha, the second or first pharaoh of the 1st Dynasty, features the symbol of Sais, and several tablets record the king’s visit to Neith’s shrine there.

The temple was connected with a medical school, which notably had many female students and teachers, often in the fields of gynaecology and obstetrics. One inscription there reads ‘I have come from the school of medicine at Heliopolis, and have studied at the women’s school at Sais, where the divine mothers have taught me how to cure diseases’. In the Late Period, the Temple of Neith was known for weaving linen cloth of such fineness that it was almost transparent. The splendour of the temple was also supplemented by tribute paid by the Greek trading settlement at Naukratis.

The archaeological rediscovery of the temple of Sais is far from complete. Up until the mid-19th-century, western explorers noted a large brick enclosure wall and a citadel at the city’s location. However, these were all but destroyed by treasure hunters and local builders repurposing the stone by the end of the century. A 1993 excavation uncovered the location of the capital city and its industrial area. Sais’s strong trade links were evidenced by the presence of Greek trading amphorae and Syro-Palestinian wine jars at the site. Objects and material dating to circa 1100 B.C. were also found, revealing that Sais had long been a wealthy town.

Archaeological excavations continue there today, as many of the sites recorded in written sources have yet to be located. For instance, Herodotus described a sacred lake used by the temple for rituals and washing, where he attended a ceremony of lights. So too, has a statue dedicated to the official who built the lake been found, even though the lake itself remains undiscovered.. There is much still to learn about this important centre and its manifold artistic and architectural beauties.

'The chronicle of this sculpture began over two and a half millennia ago, during the reign of King Amasis (570-526 B.C.).

Subsequent alterations, as well as damage both intentional and accidental, have contributed subtly to the serene beauty of the original.'

Egypt in the 26th Dynasty

The 26th Dynasty

The 26th Dynasty gained power in Egypt after the Neo-Assyrian conquest of 670-663 B.C.. During the reigns of 25th Dynasty pharaohs Taharqa and Tantamani, Egypt was in constant conflict with the Assyrians. From 664 B.C., the Assyrian-allied rulers of the 26th Dynasty controlled Lower Egypt, while Taharqa and Tantamani continued to hold Upper Egypt. In 663 B.C., Tantamani launched a full-scale invasion of Lower Egypt, retaking Memphis and killing 26th Dynasty ruler Necho I of Sais. In response to this, the Assyrians launched a counter-attack led by Necho’s son, Psamtik I, which forced Tantamani north of Memphis. The Kushites of the 25th Dynasty subsequently retreated to their spiritual homeland in Napata, where they established the Kingdom of Kush, which flourished there until around the second century B.C..

Thebes peacefully submitted to Psamtik’s fleet in 656 B.C., and he affirmed his authority there by positioning his daughter in line to be the next Divine Adoratrice of Amun. Psamtik also secured Egypt’s southern border at Elephantine, effectively uniting Egypt. He managed to negotiate freedom from Assyrian control while remaining on good terms with Ashurbanipal, thus ensuring increased stability for Egypt throughout his 54-year reign. Because of this, the foundation of the 26th Dynasty is viewed by many as the start of the Late Period.

The 130-year rule of the 26th Dynasty, also known as the Saite Period, ushered in a new phase of artistic expression in stone monuments and statuary, drawing on the long traditions of earlier periods in ancient Egypt. 26th Dynasty art would go on to be emulated by later ruling dynasties of Egypt, as a representative example of ‘Egyptian style’.

Following the fall of the Assyrian empire in 612 B.C., the Saites launched military campaigns into Asia Minor and Nubia. Their armies were supported by foreign mercenaries, who had their own quarters in the capital city of Memphis. A trading settlement with the Greek city-states was established at Naukratis in the western Delta, and Thonis/Heraklion was populated by both Greek and Egyptian locals, facilitating a direct interchange of cultures. The Greeks also settled many other areas in the Delta. The 26th Dynasty came to an end when the Persian empire conquered Egypt in 525 B.C., bringing an end to native rule of Egypt.

Amasis II (r. 570-526 B.C.)

This bust has been dated to the reign of the penultimate ruler of the 26th Dynasty, Amasis II (also known as Ahmose II). According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Amasis was a civilian officer in the Egyptian army, who gained the throne during a revolt against King Apries. Apries’s unsuccessful military campaign against Cyrene in Libya made the Egyptian troops suspect that they had been deliberately betrayed so that the king might gain more complete control through the use of Greek mercenaries. Amasis, then a general, was sent to calm the troops and prevent a revolt, but was instead proclaimed king by the rebels. In the ensuing civil war, Apries fled to an island and was then killed in a final attack in circa 567 B.C.. Amasis then married Apries’ daughter, Khedebneithirbinet II, in order to legitimise his kingship.

Amasis’s forty-four year reign was a period of new prosperity for Egypt. He took a philhellenic approach to international relations: marrying the Greek princess Ladice to secure good trade relations, assigning the commercial colony of Naucratis on the Nile to the Greeks, and donating 1,000 talents to the rebuilding of the temple of Delphi after it was burned. Herodotus even claims that Ladice cured Amasis of his impotence by praying to the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite. Under Amasis, Egypt’s agricultural economy flourished and large cities were established across the country. He conquered Cyprus, and defeated an attempted invasion by the Babylonians, led by Nebuchadnezzar II. He spent the last years of his reign defending the country from the growing threat of Persia under the rule of Cyrus the Great. Herodotus tells that the Persian invasion was brought about when Amasis forced a disgruntled ophthalmologist to serve either Cyrus or his successor Cambyses II, in forced exile in Persia. The doctor grew close to Cambyses and suggested that he ask Amasis to allow him to marry one of his daughters to solidify their growing closeness. Amasis refused to send his own child, and instead sent the beautiful Nitetis, daughter of his predecessor Apries. Nitetis revealed this ploy to Cambyses, who vowed to take his revenge and launched an invasion of Egypt. Amasis, however, died six months before the Persians reached him, leaving his son Psamtik III to be defeated by their troops in 525 B.C..

Amasis was viewed as a cunning and shrewd ruler. One story tells of how he, when he heard that the Egyptians were disparaging his low-born origins, had his golden footbath melted down and moulded into a statue of a god. He placed this statue in the centre of the city to be worshipped. Once the citizens had paid great reverence to the statue, Amasis revealed that it had once been the footbath in which people had vomited, urinated, and washed their feet. Like the footbath, he claimed he had been transformed from his humble origins and now should be accorded the respect due to a king.

Amasis was also celebrated as a builder of temples and religious centres, particularly in Lower Egypt. For instance, he commissioned the new Banebdjed temple at Mendes, a temple for the cobra-goddess Wadjet at Buto, and chapels in the Bahariya oasis. He also continued construction on the temple of Neith at Sais and the temple of Ptah in Memphis.

In his portraits, Amasis is depicted with a long face and high-set brow line, and commonly represented in greywacke stone. His features were so distinctive that he can be recognised even in a head that was reworked for a non-royal official now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (2007.81).

One sphinx inscribed for Amasis and found at the Temple of Isis in Rome (Museo Capitolino, Rome, inv. 35) is damaged in a similar manner to this bust of a goddess, with the nose broken off, chipping to the edges of the ears, and an inscription on the chest that has been partially picked away. The erasure to the chest of the sphinx was most probably made during pharaonic times, as was the corresponding damage on the greywacke goddess.

A number of finely carved statues in greywacke from Amasis’s reign have all been attributed to the same workshop or artist, dubbed the ‘Greywacke Master’ by Egyptologist Biri Fay. As well as the portraits of the king himself, non-royal sculpture for officials in Amasis’s government also exhibit the same high standards of workmanship. It is probable that many of these were created in the same royal studio.

'Animula vagula blandula, Hospes comesque corporis, Quae nunc abibis in loca

Pallidula, rigida, nudula, Nec, ut soles, dabis iocos...'

'Little soul, drifting, gentle, Guest and companion of my body, Where now will you go, Pale, stiff, and bare, No longer joking as you used to?'

Collecting Egypt: Ancient Roman Collectors

The Greywacke Goddess was probably among the many fine pieces of ancient Egyptian art that were brought to Rome during antiquity, as Egyptian artworks, materials, and fashions became hugely popular throughout the Roman empire.

Following his victory against Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII at the Battle of Actium, Emperor Octavian (later known as Augustus) conquered Egypt in 30 B.C.. The annexation of Egypt cemented the pre-existing political and trade links between the Romans and the Egyptians, and sparked an ‘Egyptomania’ amongst the Roman populace. As well as bringing Egyptian artworks themselves to Italy, the Romans made their own Egyptianising artworks and included Egyptian features in their wall paintings and furniture, as well as glass and metal tableware. The term aegyptius was used to describe both locally-made and imported objects relating to Egypt, and the most popular kinds were those that looked most ‘Egyptian’ to Roman eyes – such as representations of royals and gods, sphinxes, and animals like hippos and crocodiles.

Some elements of Egyptian religion also found a new home in Rome. The goddess Isis, in particular, found great popularity amongst the Romans, and many personal household shrines were dedicated to her. An obsidian skyphos (wine cup) inlaid with precious gold, coral, lapis lazuli, jasper, carnelian, and malachite found at the Villa San Marco in Stabiae, dating to 1st Century B.C.-1st Century A.D., attests to the fusion of artistic and religious culture taking place at the time. Egyptian statues were also used to decorate Roman cultic centres and temples, possibly suggesting that the solemnity of sculptures that were ancient even to the Romans lent an additional grandeur to their own important cultural sites.

Hadrian’s Villa

Hadrian’s Villa on Monti Tiburtini near Tivoli, outside Rome, was built by Emperor Hadrian in around 120 A.D. as a retreat from the city. The villa complex contains over thirty monumental buildings arranged across a series of artificial esplanades and landscaped gardens, cultivated farmlands, and water features – covering an area of at least a square kilometre in total. The region was selected due to its abundant water supply, in close proximity to four aqueducts that continued on to Rome: Anio Vetus, Anio Nobus, Aqua Marcia, and Aqua Claudia. It was easily accessible, and could be reached via the ancient Roman roads Tiburtina and Prenestina, as well as the River Aniene.

The complex was constructed as a series of independent and interlocking structures, each with their own purpose. The Poecile was a vast garden with a swimming pool, surrounded by an arcade so that it could be enjoyed in any season. The Canopus was a long water basin featuring columns and statues, leading to a temple topped by an umbrella dome, and the remains of two bath areas (the Grandi Terme, and the Piccole Terme). These structures were designed for the use of the imperial family and their guests, and were decorated with polychrome stucco. Other well-preserved areas includes the accademia, the stadio or arena, the Imperial Palace, the Philosopher’s Room, the Greek Theatre, and the Piazza d’Oro. There was even an artificial island, the Maritime Theatre, surrounded by a canal and colonnade.

One of the grandest rooms in the villa was dedicated to the Ptolemaic Egyptian god Serapis. The Serapeum was entered via a long pool designed to resemble the Nile, populated with statues of crocodiles and the god Bes. The Serapeum itself featured cult statues of Serapis as well as many fine greywacke sculptures imported from Egypt. Hadrian also commissioned a large number of statues in the likeness of his deceased favoured Antinous in Egyptianising style, many of which were excavated from Hadrian’s Villa. The deified Osiris-Antinous is depicted wearing the royal nemes-headcloth and shendyt kilt, standing with one foot in front of the other – a pose typical of Egyptian art. These foreign elements are combined with the highly naturalistic Roman style of carving in order to lend power and prestige to Hadrian’s beloved favourite.

18th-Century Italian Excavations

In the 18th century, Hadrian’s Villa became the site of many excavations performed by cardinals and other visitors as part of the Grand Tour. The first excavation was undertaken by Francis Antonio Lally in 1722, who unearthed a series of sculptures interred in pits, probably buried during antiquity. Other famous excavations include those by Alessandro Furietti in 1736 and 1737, leading to the discovery of the Furietti centaurs – a pair of black marble sculptures signed in Greek by Aristeas and Papies from Aphrodisias. Much of what was excavated during this period is now in the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican.

(Left) Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Avanzi del Tempio detto di Apollo nella Villa Adriana vicino a Tivoli (Hadrian's Villa. Remains of the Smaller Palace [Formerly called the Temple of Apollo]), c. 1768, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

(Right) Marco Carloni (1742-96) Excavation of Antiquities Rome, 2nd Half 18th Century Etching on paper.

Other Known Egyptian Goddesses in Stone

Figure of Isis

Third Intermediate/Late Period, Egypt

Steatite

H: 10 cm

The British Museum, London, EA60750

Head of a Royal or Divine Woman

18th Dynasty, Egypt

Granite

H: 36.50 cm

The British Museum, London, EA956

Fragmentary figure of IsisSerqet

Late Period, Egypt

Basalt

H: 10.50 cm

The British Museum, London, EA57365

Fragmentary Female Figure, likely a Goddess Ramesside, Egypt

Limestone

H: 8.67 cm

The British Museum, London, EA2384

Fragmentary Statue of Queen Ahmose-Merytamun wearing Hathor Wig

Early 18th Dynasty, 15001450 B.C., Egypt

Limestone

H: 113 cm

The British Museum, London, EA93

Head of a Queen or Goddess Circa 230 B.C., Ptolemaic Period, Egypt

Limestone

H: 10.8 cm

Brooklyn Museum, New York, 86.226.32

Statue of Isis

Reign of Amasis/Khenemibre, Late Period, Egypt

Basalt

H: 23 cm

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence, 313

Head of a Goddess Circa 1295-1270 B.C., New Kingdom, Egypt

Limestone

H: 16 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000.62

Fragmentary Statue of Isis

30 B.C.-395 A.D., Egypt

Diorite

H: 43 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris, E 22459

The Goddess Mut Circa 664-525 B.C., 26th Dynasty, Egypt

Schist

H: 16.2 cm

Brooklyn Museum, New York, 76.38

Head of a Ptolemy Queen or Goddess

2nd Century B.C., Ptolemaic Period, Egypt

Steatite

H: 48 cm

Benaki Museum, Athens, 32525

Figure of a Queen or Goddess Ptolemaic Period, Egypt

Granite

H: 68.5 cm

Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin, ÄM 21763

Bibliography

'Among the major arts associated with the funerary cults of ancient Egypt... none gives us a deeper understanding than sculpture. Like man himself, it is three dimensional and thus encompasses the human measure, the essence of his humanity, tangibly, in a durable material, on a human scale.'

Bernard V. Bothmer, 'On Realism in Egyptian Funerary Sculpture of the Old Kingdom’, Expedition, (Pennsylvania, 1982)

Bloxam, Elizabeth, et al., ‘Investigating the Predynastic origins of greywacke working in the Wadi Hammat’, Archéo-Nil, 24 (2014), pp. 11-30

Bothmer, Bernard V., Antiquities from the Christos G. Bastis Collection (Mainz, 1987)

Bothmer, Bernard V., Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period, exhibition catalogue, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, 18 October 1960-9 January 1961

Bothmer, Bernard V., ‘On Realism in Egyptian Funerary Sculpture of the Old Kingdom’, Expedition, 24:2 (Winter 1982)

Burnett Grossman, Janet, Podany, Jerry, and True, Marion (eds.), History of Restoration of Ancient Stone Sculptures (Los Angeles, 2003)

Carradori, Francesco, Istruzione elementare per gli studiosi della scultura (Florence, 1802)

Cavaceppi, Bartolomeo, Raccolta d’antiche statue, busti, bassirilievi ed alter sculture: restaurate da Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, scultore romano, Volumes 1-3 (Rome, 1768)

Champollion, Jean-François, Lettres écrites d’Égypte et de Nubie en 1828 et 1829 (Paris, 1868)

Clark, Anthony M., ‘The Development of the Collections and Museums of 18th Century Rome’, Art Journal, 26:2 (Winter, 1966-1967), pp. 136-143

Dallaway, J., Anecdotes of the Arts in England or Comparative Observations on Architecture, Sculpture, & Painting, Chiefly Illustrated by Specimens at Oxford (London, 1800)

Edwards, Amelia B., Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers (New York, 1892)

Fazzini, Richard A., ‘Bernard V. Bothmer (1912-1993)’, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 32 (1995), pp. i-iii

Fowler, Abdel-Rahman, and Hamimi, Zakaria, ‘Turin Papyrus Map and Historical Background of Geological Work in Egypt’, in The Geology of the Egyptian Nubian Shield, ed. Hamimi, Zakaria et al. (Cham, Switzerland, 2020), pp. 1-13

Friedland, Elise A., ‘Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture around the Bay of Naples. An Exhibit at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.’, Near Eastern Archaeology, 72:1 (March 2009), pp. 55-59

Gamba, Claudio, ‘Maratti, Francesco’, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 69 (2007): https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-maratti_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (accessed 17/04/2025)

Hardwick, Tom, ‘The Victorian Collectors who Loved Art from Ancient Egypt’, Apollo, 25 January 2020: https://www.apollo-magazine.com/bolton-ancient-egypt-museumscollecting/ (accessed 17/04/2025)

Harrell, James A., and Brown, V. Max, ‘The Oldest Surviving Topographical Map from Ancient Egypt: (Turian Papyris 1879, 1899, and 1969), Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 29 (1992), pp. 81-105

Harrell, James A., and Brown, V. Max, ‘The World’s Oldest Surviving Geological Map: The 1150 B.C. Turin Papyrus from Egypt’, The Journal of Geology, 100:1 (January 1992), pp. 3-18

Harrell, James A., Archaeology and Geology of Ancient Egyptian Stones, Volume 1 (Oxford, 2024)

Heywood, Ann, and Serotta, Anna, ‘Queen Hatshepsut Restored’: https://www.metmuseum. org/about-the-met/conservation-and-scientific-research/conservation-stories/2020/ hatshepsut (accessed 17/04/2025)

Hikade, Thomas, ‘Expeditions to the Wadi Hammamat during the New Kingdom, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 92 (2006), pp. 152-162

Howard, Seymour, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi: Eighteenth-Century Restorer (New York and London, 1982)

Hughes, Jessica, ‘The myth of return: restoration as reception in eighteenth-century Rome’, Classical Receptions Journal, 3:1 (May 2011), pp. 1-28

Johns, Christopher M. S., ‘Papal Patronage and Cultural Bureaucracy in Eighteenth-Century Rome: Clement XI and the Accademia di San Luca’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 22:1 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 1-23

Jones, Prudence, Stephanie Pearson, The triumph and trade of Egyptian objects in Rome: collecting art in the ancient Mediterranean. Image & context, 20. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter, 2021. Pp. viii, 264.