Acknowledgement of Country

This edition of 1978 was edited, compiled, and published on the occupied lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded, and that the occupation is violent and ongoing. We extend our deep respect and solidarity to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and to their Elders past and present.

THIS LAND ALWAYS WAS AND ALWAYS WILL BE ABORIGINAL LAND.

First published 2025 by the University of Sydney

Funded by the University of Sydney Union & the University of Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

© Individual Contributors 2025

Foreword © Lesley Podesta

Graphic design © Faye Tang & Claudia Blane

Layout © Faye Tang & Claudia Blane

© The University of Sydney 2025

Images and some short quotations have been used in this book. Every effort has been made to identify and attribute credit appropriately. The editors thank contributors for permission to reproduce their work.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-74210-584-0

PDF ISBN: 978-1-74210-583-3

1978

Reproduction and communication for other purposes:

Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below.

Fisher Library F03

The University of Sydney

NSW 2006 Australia

EmailL sup.info@sydney.edu.au

Website: sydney.edu.au/sup

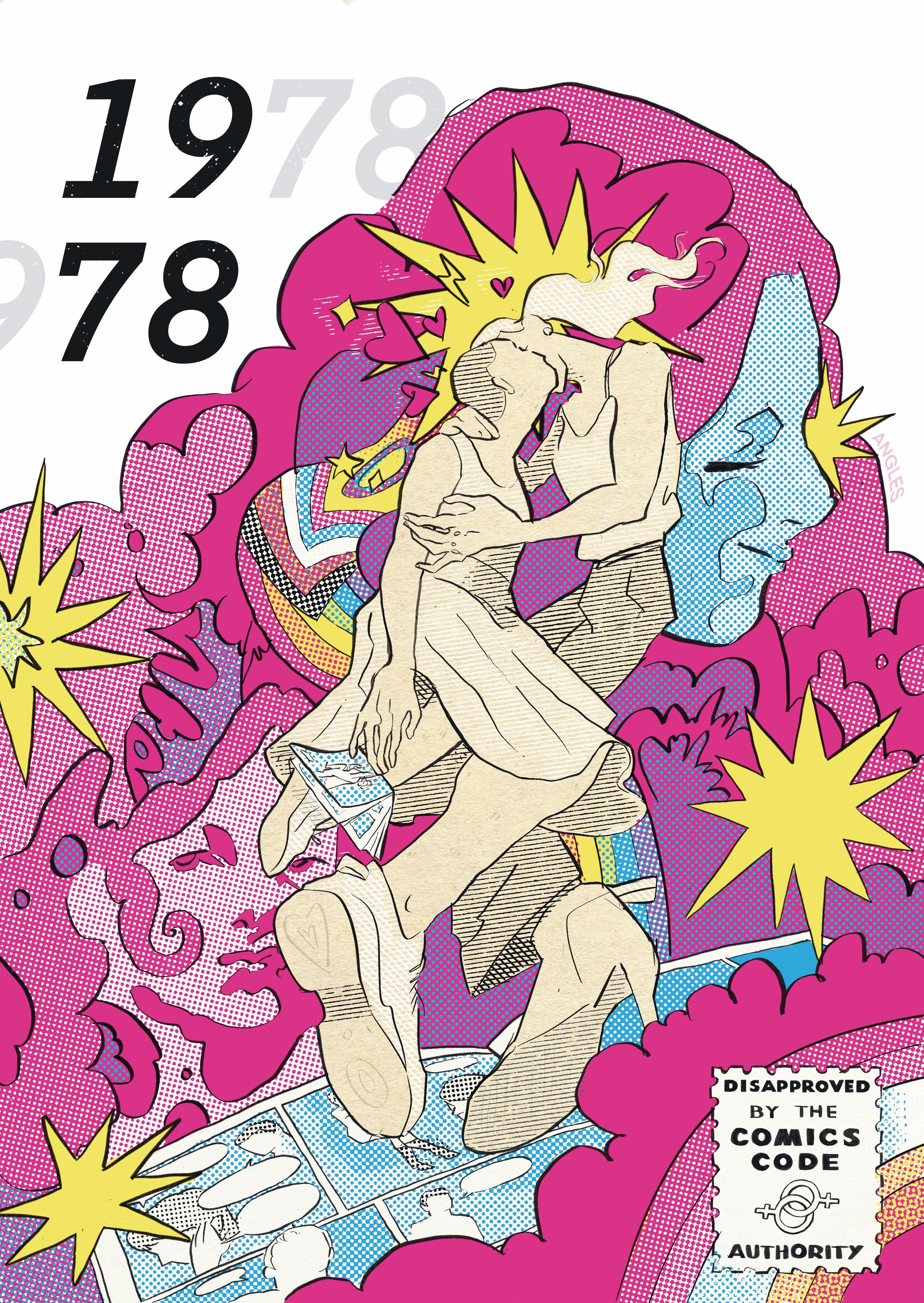

Cover design by Caitlin Angles.

To those who refused to shrink and comply: your ‘too much’ is just enough.

OperatiOns Manager

Madison Burland (she/her)

editOr-in-Chief

Samaira Dua (she/her)

Creative direCtOr

Ethan Floyd (they/them)

general editOrs

Madison Burland (she/her)

Marc Paniza (he/him)

Jenna Ritchie (she/her)

pOetry editOrs

Alice Heffernan (she/her)

Gracie Allen (she/her)

prOse editOrs

Ramla Khalid (she/her)

Katie Short (she/her)

nOn-fiCtiOn editOrs

COntributOrs

Rory Blue

Maddie Carter

Cate Chapman

Stella Feltham

Kelsey Goldbro

Hanna Liszka

Victoria Natthanicha

Simone Wong Feronia Ding

Isabella Guzman

Wood Lesley Podesta

MaysaEmmaSarkis Lee

Emma Booth

artists

Gracie Allen (she/her)

Alice Heffernan (she/her)

Mehnaaz Hossain (she/her)

Marc Paniza (he/him)

visual art editOrs/designers

Faye Tang (she/her)

Claudia Blane (she/her)

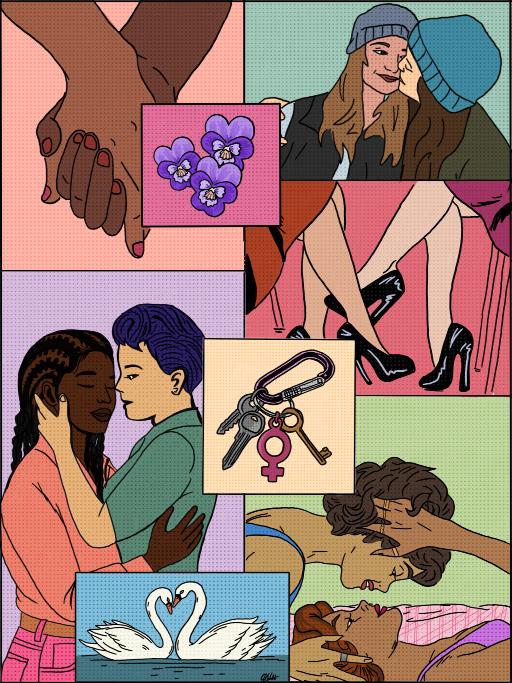

Artwork by The #1 Feminist Second place in the 2025 1978

A Note From the Editors-in-Chief

SamairaDua&JennaRitchie

Dearest Readers,

As a journal, 1978 is inherently subversive — named after Sydney’s first Mardi Gras — aiming to amplify and broadcast the voices of women and the queer community to whoever will listen. It was created five years ago by Kate Scott and Jenna Lorge, and SASS has since published three beautiful editions.

Last year’s edition never made it to press. So when we stepped into this role, we carried a responsibility: not just to avoid past mistakes, but to pick up the scattered pieces and arrange them with care and purpose. We were fighting — for recognition from the University, from our fellow students, and for the simple reminder: we’re here, we’re queer, and we’re bringing 1978 back with a bang.

This edition is a product of its time — born in a moment of political and economic precarity, simultaneous cultural oversaturation and degradation, and a collective search for meaning and belonging. We loosely kept to a style of comics, as they have historically been used to subvert, to satirise, to speak; an art form that combines both play and provocation. In that context, 1978 serves not just as a publication, but as a protest, a celebration, and a gathering of voices that refuse to be quiet.

Every piece in this journal speaks to the messiness of life and brings form to not only what it means to be queer today, but what it means to be human today.

With that, first and foremost, We would like to thank Madison Burland, my fellow publications officer and the operations manager for 1978. Her resilience has carried us through, day in and day out, and her sheer determination is the reason we get to hold this magazine in our hands. We would also like to thank our editors, contributors, and art competition winners for pouring their time, heart, and talent into this journal and helping shape what it has become.

It has been an honour to breathe life back into 1978.

—Samaira Dua & Jenna Ritchie

Foreword

1978 was my second year at Sydney University where along with my dear friend Garrett Prestage we ran Active Defence of Homosexuals on Campus (ADHOC). This popular organising and socialising group, supported by the SRC, actively campaigned on gay rights and feminism. We held workshops on subjects such as censorship of gay press, Stonewall, the threat posed by the emerging Right including the homophobic US Save Our Children campaign, and police violence on the beats of inner Sydney.

Though not formally politically aligned, most members leaned Left, with various socialist factions and many anarchists attending. Our lesbian and radical feminist sisters were crucial too — ADHOC attracted women who valued collaboration with like-minded men despite the undercurrent of lesbian separatism that existed at the time. ADHOC prided itself on welcoming people and encouraging students to come out knowing there were kind, funny and friendly people who would embrace them.

We were perpetually in motion—silk screen printing posters at the Tin Sheds, staging danceoffs to “In The Flesh” at Manning Bar, holding sit-ins at the General Philosophy department over aspects of French feminism, writing columns for Honi Soit, drafting motions for the SRC, attending AUS council, parading through campus singing “Glad to Be Gay” and running fundraisers and gay dances on campus. It was always busy, always exhilarating, and honestly, we didn’t attend many lectures but somehow we managed to pass.

Amidst the activism came intimate connections. Many of us regularly went bar-hopping along Oxford Street — we knew every song, danced together and usually went home with someone

Bridging Our Past and Future: A Call for Unity Across the Queer Spectrum

Lesley Podesta

new. In those days, we consciously avoided whoever we fancied most when out in public. Coupling up wasn’t the done thing, and very few of us practised monogamy. We had crushes, we explored, we fell in love, but mostly we laughed and found joy together. It was a glorious period of activism, growth, provocation and learning, forging lifelong friendships and professional relationships.

Naturally, many of us became closely involved in planning the first Mardi Gras, a lot of us were active members of the Gay Solidarity Group. On that fateful day, I attended the morning march with my megaphone. In the afternoon, I delivered a detailed presentation about Anita Bryant, Save Our Children, and the threat posed to gay rights by an Evangelical movement fronted by a former beauty queen. I remember Dennis Altman, my American Politics lecturer, approached me afterwards to commend me for transforming a recent essay into an engaging talk. Well—we were flat out; who had time to write two separate pieces, Dennis?

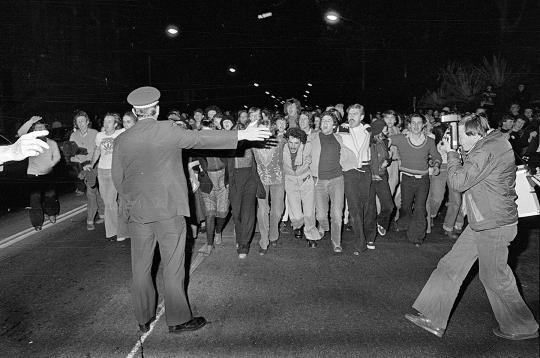

The events of that night are now legendary— our joyful, dancing, singing parade of beautiful troublemakers, encouraging bar patrons to join us “out of the bars and into the streets” as we wound through Kings Cross, was suddenly confronted by hostile police who chased, beat and arrested many of us.

I watched in horror as my girlfriend Maria was dragged into a police van by her arm, my dear friend Chips was chased and tackled by two large officers as he tried to escape down a lane, and my friend Peter was struck hard, his head deliberately slammed against a van door. I twisted my ankle while fleeing and spent weeks on crutches. It was shocking, terrifying and brutal.

We spent the entire night organising bail money and legal representation, keeping vigil outside the police station until dawn. The subsequent weeks and months became a whirlwind of demonstrations, meetings and court appearances. Though I hadn’t been arrested despite being in the thick of it, I served as an informed witness, appearing in court countless times.

Looking back from 2025, our world has transformed in both uplifting and challenging ways. As the lesbian mother of a transgender daughter, I’ve expanded my understanding of gender beyond what we conceived in the 70s. It saddens me when feminists from my era—women who fought fiercely for women’s empowerment and against male appropriation of female identity — struggle to embrace our current moment. My heart breaks hearing older activists dismiss transgender women as “men in drag” or performers undermining lesbian spaces and identity. I detest how right-wing extremists have targeted older lesbians in their campaigns against transgender people.

I long to recapture the joy, inclusion and revolutionary spirit of the seventies — when we danced, laughed and created change together regardless of our differences. The venomous rhetoric directed at transgender people from some activists of my generation is profoundly distressing and, as my daughter rightly says, “exhausting.”

My vision for 2025 is to rekindle genuine dialogue and further dismantle binary notions of gender. Let’s extend respect and inclusion to everyone in our beautifully diverse queer community. If that means 70-year-old CIS lesbians need to connect with 19-year-old non-binary and gender-diverse folks on the dance floor, then I say — crank up the music and let the healing begin. Stop feeling threatened by this generation of gender activists. Human rights are not pie, you don’t lose your rights, just because someone else is afforded respect.

Congratulations to the 1978 committee for continuing to amplify the visibility, diversity and voice of all members of our community. The revolution we started requires us to keep evolving — together.

www.78ers.org.au/the-78ers.

and

Branco. Protesters and Police at the First Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. 24 June 1978. City of Sydney News, https://news.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/.

Lesley Podesta was an Arts/Law student at Sydney University in the mid seventies. She was an SRC rep, the SRC women’s officer and the local AUS Secretary. She was an active member of Active Defence of Homosexuals on Campus ( ADHOC) and part of the original Mardi Gras in 1978. She has had a long career in government, public health and social impact and has continued to be a strong advocate for social justice and inclusion.

78ers. The 78ers.

Swift, David. Unite

Fight for Trans Rights protest. News. com.au, NewsWire.

Gaica,

summer solstice / came too soon / lazed around and tried to read a book / watched some films instead / plans fell through / painted my nails to pass / the time / pretended to write in my journal / as if I had something / to say / as if my bedroom is not a grave / as if love had found me / composing letters of longing / spent minutes upon minutes imagining how touch might feel / entering beautiful worlds / that dissipate into smoke / forming ripples upon the lake’s smooth surface / preserved into ammonite / the absence / remembering itself / reminiscing over winter’s song / smoking cigarettes outside the bar / cried to my friends 2 hours before / don’t leave me don’t leave me please don’t leave me / new years passes like an autumn leaf / midnight does not renew / there is a sickness in my body / it will not leave / no matter how many doctors appointments / no matter how many times it is washed and scrubbed / even poetry cannot rid its lingering spirit / want to stay this age forever / never want to be this age again / 20 is too old / the centre cannot hold / and there is no room for my voice / lonesome and quiet / like waiting outside a party / the door bolted shut / no teenage loves / or even heartbreak / wonder if the ability still remains / without exercising it / can a songbird still be a songbird / if it does not sing / imagine living my whole life this way / the tears rise easily / sisyphean in nature and seeking a holy answer / neither catholicism nor atheism renders / my world complete / can’t quite believe / that David Lynch is dead / decide to get an angel / tattooed / almost / as if that can make up / for the loss / I am still reeling from / reminds me of my grandma’s passing / how I still tear up / every time I think about her / how I can never speak to her again / nor hold her hand / the incomprehensibility of / summer storms / how heat is / followed / by sharp rain / and then returns / to still warmth / existing in extremes / the only way

Immaculate conception.

a birth squeeze into an ocean deep. My divinity refused by my own blood,

By a conflicting current of care

That upturns and capsizes apathetic vessels, and burdens

Those who wish to mythologise me.

To hold my seafoam hair in their clutch.

To press my chest to theirs.

To push me away

When they cannot contain all of me, Or handle the pruning of skin,

The purification of what weighs them down And threatens to drown them

When their legs can tread no more.

All that they once prayed for from me.

Martyred in worship of my own name.

Naiad below the surface with destiny assured:

If I rise again,

My head will belong to earth, My throat to air,

My body to fire.

Only spirit will remain my own.

Perhaps I would sit atop a hill shaded by a fig tree overlooking my sea, and with discontent,

turn away any new venture that beckons me in favour of a solitary mourning of the storm that had passed. Tethered evermore to the tide’s whims.

And someday, when I am found by an unborn generation, captivated by my myth–which you took and told as villainy–I would look the same as I always have.

Maybe my heart would learn how to forgive grudge Entirely.

Only then would the seaspray wholly replace the ash from the fires I nursed–

Seeking salt from water in fear of accepting the humiliation of my lapse in judgement.

The belief in fate threaded together–Not a brief entanglement. Not expecting that what I wanted to shake off and destroy, Would include our connection–Dissolving in my gentle grip the instant I brought it into the water with me.

Bitterness released through change. Towards Enlightenment.

There is closure in the end. The drawn out death

To kiss to sleep Doubt.

If Girl asks for compassion, A turned cheek.

The experience Of life

Leading spirit to slow rest.

Renting the space

Of an earthen womb– Neglected. ‘Til the silt

Mercy

Aches and shrinks Into what was— Existent.

If Girl begs care, Knife it will be.

Decided cause of spontaneous homicide,

O, killer laying in wait

For that jugular strip tease

Where I will plead and embody politeness.

I, The Angel. you, you, you, you, you— a bone infection.

I have carried dead weight before— I never wanted to admit it— And you say nature cannot be helped.

Convicted nothing but shameless. Convinced you are worthy of Me. So, I will rip you off at the joint and throw you away.

Proof of cure.

Proof that when your ego grows sore from the thought of Reciprocation, you hold My ankles tight. So I cannot rise, So I cannot heal.

Unfounded faith in My beating wellspring of generosity. Where I would never bow forward and let it flow, Unending.

Kelsey Goldbro

Kelsey G

DRIVING

Smileatyoursmile

Timeisonepasteleven

You’repassingmeapieceofapplepie

Oh,italmostmakesuscry

Don’tknowwhy

Don’tknowwhy

— Sibylle Baier,

‘Driving’

My dad and I go on drives when the house gets too bright for us to bear. At night, when the light is contained in sixty square metres, stifling and artificial and blue. I told him to change the LEDs to yellow bulbs a few weeks ago, but he just looked up at me with those thin, creased eyes and said, “If you wanna go to Bunnings and buy new ones to replace them, you’re welcome to do so.” I replied something like, “Forget about it,” and left it be. Now I bear the icy blue overhead. But I know he hates the clinical way our house feels in the evenings, a cold vacuum on a long straight street. I know our neighbours have asked him about it, joked tentatively (teetering on the edge of concern), and he probably just scoffed in return. Stubbornness is a blood-borne disease. We carry it like an heirloom.

So we don’t talk about the sterility of our interior decorating. We drive. Me behind the wheel, him with the seat pulled far enough back that he can kick his feet up on the dashboard. I disapprove, and he is well aware. We exchange the same squinty, unimpressed stares. He always breaks first, chuck ling as I roll my eyes.

But tonight, I stare at him, and he mutely watches Carol from two doors down shove a plastic bag into a too-full red bin. His fingers, calloused and slightly double-jointed, restlessly drum against armrest.

The disquiet is to be expected. The house was stuffier today, before we escaped into the unhesitat ing autumn chill. Too still, too silent. My mum used to say that when a house was always restless, bodies jostling, a din of voices, it had been lived in properly. Now: days-old coffee separating be side the sink, a circle stain on the granite, amber leaves circling the straw rocking chair on our back veranda, my mum’s CD player shoved in the TV cabinet. I can draw hearts and wonky stars in our carpet of dust, but they are erased with more of those near-invisible particles by the morning. And when the sun lowers just so, spilling through our front window, our floor lights up with the fuzzy, blurry stuff, and I feel genuinely disgusted. But not enough to grab a broom from our untouched storage cupboard. I sit there in the dust.

“Do you want to head out coast?”

My dad blinks, remembering himself, and turns to me. “Okay.”

“Down to Maroubra or something.”

“Sure.”

Jazz hour on the radio, the thrum of the engine, my phone knocking against the cupholder. I chew my lip and think about driving somewhere out of town, overnight, to where the stars glisten fruitfully across the endless black. My dad sniffs and rubs his nose.

“Are you working tomorrow?”

“Gave my shift to Rebecca, actually.”

“Oh?” He twists in his seat, sniffing again. “Got plans?”

The conversation was inevitable, but I still wince. Avoid eye contact. “Amy and I are going to visit Mum.”

My dad’s face seems to set in its mould. A slow grimness sinking in. Smoothing out the wrinkles around his nose.

Amy is my mother’s sister. She sews and knits prototypes for a living, and she comes by our house every weekend with a new piece for me and cookies for my dad. She and my dad haven’t spoken in a month, but still. Every week, a tupperware tied with a sheer blue ribbon in exchange for an empty one, its ribbon reapplied. Amy and I set this date weeks ago.

“Okay,” my dad says.

“Okay?”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I just…” The road is empty and I have nothing to say, despite practising this conversation for weeks, lying in my bed with too many words piled around me.

He’s silent as I pull onto the main road. Headlights flash around and through the car. I’m focusing on the high beams of the car behind me so I can ignore the awkwardness pressed against the roof, too tall for my Corolla and taking up all the air.

“Wait, pull into here.”

I startle at the breaking of silence and look sideways to see my father adjusting himself in his seat, hands reaching for the door handle. I don’t answer but do as he requests, turning into the petrol station.

He unclasps his seatbelt and practically launches himself out of the car before I’ve even shifted into park. My hands grip the wheel, the gear stick. I don’t know how long it has been: my fingertips and my sweat are pressing into the leather wheel; my dad is rummaging around the petrol station store. The streetlights are glaring white, and I am reminded, ridiculously, of our home.

Then, the automated bell chimes and there he is, lumbering towards me with a plastic bag, weighty and swinging. He closes the door gently, purposeful, when he enters the car. As if showing me that he’s cooled down. He sets the bag between his feet.

“Are we gonna talk about it?” I ask.

He speaks gruffly. “I’m no good at talking.”

“But that’s the problem, dad. That’s—” I stop my voice from rising. I sigh. “We go on these drives and discuss trivial things. The weather. My job. But I don’t understand what we have to gain from these conversations when we can’t even talk about her.”

Tilting his head, not quite looking at me, he is quiet as he admits, “I know silence makes you feel lonely.”

I think, at first, that that’s not true. That silence can pillow loneliness and make it softer, bearable, though not quite comfortable. It can both seize you in the gut and melt over your head. I frown and notice my dad glancing to the left at the side mirror.

“When was the last time you saw Sara?” he’s asking.

I sigh. I could ask him about his own friends, spin the conversation back on him, but I don’t. The stars look further away than they usually do, more unreachable. Dewdrops on a drying wall. I stare at them and forget to reply.

We drive for a bit longer, the jazz channel switching over to some symphony written centuries ago by some Mozart type. Strings swell and fill the stiff gaps between the two of us. Though it does feel far less choking.

I make an unplanned decision to turn into the parking lot of Maroubra beach. It is quiet, slowly draining of cars, and the waves have slunk back to low tide. They roll gently, and the sound of their foam fizzing against the sand carries over the dunes through the now open windows of my Corolla. I stick an arm out and rest it on the window’s edge, hand tapping the red metal. The air is sticky and sweet.

“Maybe we should stop driving around all the time.” I look at my dad sadly. “It’s getting expensive.”

He exhales a short, breathy laugh and leans back. “I guess so.” There’s something unfixed in the distance that his eyes track back and forth, far off the shore. Sliding on the horizon.

Wordlessly, my dad pulls out two cans from the opaque plastic bag and hands me one of them. I turn it over, its metal cool and sweating on my palm. A vanilla coke.

I’m struck by how I’ve gotten used to our empty fridge. The absence of vanilla cokes lined up in rows. Wind stings against my bare skin, and I bring my arm back into the protection of the car. The can crackles as I snap the tab. A pop and then sizzling. I take a sip and am overcome with the taste of her. The way her smell sits at the back of my throat as a spicy sweetness runs over my tongue, making my eyes water. She exists in its bubbles, its lick of caramel.

This feels like the end of something. Not a mourning period—I don’t believe that will ever end—but an immediacy. The sharp pain in the spine when you wake up and remember that she isn’t. The emptiness of it all. I will never stop looking for her in the corners of our house, but I think it’ll be less gutting when I do look.

“I don’t think I’m lonely, Dad,” I say. “Tired, maybe.”

He hums into the opening of his can, an echoing sound that turns down at the edges and fades melancholically. “How can I make that go away? I want to make it go away.”

I close my eyes. “It’s okay. You can’t. But,” I say. “You could change out our lightbulbs.”

When I peek one eye open, he’s there, smiling without his teeth. Yet, genuine. The end of immediacy and sterility and shying from change like it’s a restless bull with a spiked collar.

“I can do that.”

I smile back, full of the kind of relief that streams through your whole body, and drop my coke can into the cup holder so I can plug in my phone. The car shivers with music, alive. The bass shakes the skin on my leg where it’s pressed against the speaker. Sibylle Baier pouring out and floating around us as we drive back home.

The Ritual

Tonight, engaged in the unconscious ritual of the porcelain altar I doused my fingers in pungent granular creams, its secondary nature, the screw lids holding potently feminine essence, Trying to assimilate you within its lavender embrace.

Sterilised cabinets, exposed, placid white lined with miscellaneous treatments. Bold inscriptions: ‘Rejuvenate,’ ‘Revitalise,’ shedding haggard skin, the user pink and teeming, emerged from the chrysalis young and lovely, Eve, untouched, relishing in an unabashed nakedness.

All the assortments blend, a feathery concoction, mimicking femininity and I am seized by that juvenile need to conform, that desperate desire, a thick corrosive acid, migrating slowly through my body, a slow-moving cancer.

I will lather my body, pollutive essence, aged children’s pageant star, jaundiced skin, sad eyes. I lie in bed, waiting for my consciousness to slip from beneath me. Is this the zenith of self-fulfilment?

Before sex’s thorned head rose, a lofty beacon breaching childhood’s tranquil waters

I remember how the world unfurled, unadulterated, burnt wet bark in the air, freshly flowered fauna, a musky sweet concoction.

I remember being a girl, before the word was tainted before the sexes diverged, before smooth chests, narrow hips, before womanhood, carved from stone, adorned with dark rouge lips, eyes round and colourful.

I remember sitting at the stool in the fish and chip shop with my mother young, sweet. I remember a woman walking, consumed by intoxicating aromas, skin scrubbed of grime the invisible layer beneath the flesh.

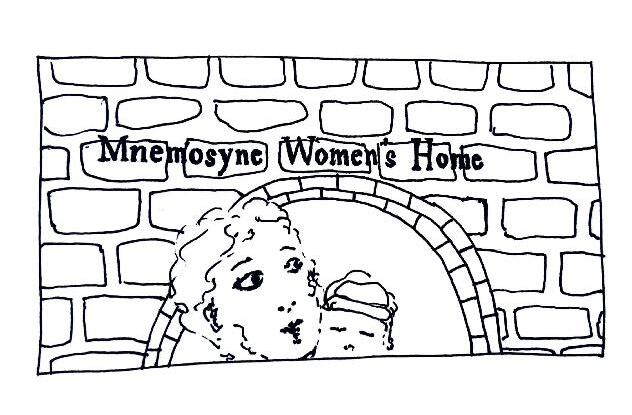

Maddie Carter

It was the winter of 1970, the winter I first saw suitcases sprout wheels in airport lines. This curious incentive to travel was the sign I needed to coax myself into accepting one final post as a nursing practitioner before I retired; before I knew it, I was standing before two enormous, wrought-iron gates dragging a wheelie suitcase of my own. The post was at a place called the Mnemosyne Hotel—a perennial, red-bricked Victorian building that stood high on a cliff, with a mansard roof and fleur-delys fencing. Heading up from the driveway, one got the impression that it resembled, spectrally, an inflating doll’s house.

The hotel (a women’s asylum turned postcard-esque family resort, which reverted to its medical purposes as a hospice at the mid-century) was a high-acuity setting, meaning each nurse was assigned a single patient. It was for people with mid-to-late-stage dementia. As well as overseeing the other nurses, I had a patient of my own: an eighty-nine-year-old woman called Penelope H.

My first impression of Penelope was in the hotel’s garden maze. She was seated on a wooden bench at the maze’s centre; a sleight, pixie-ish woman in thick-lensed spectacles, who trepidly held a pair of enormous knitting needles. When I introduced myself and inquired to know a little about her, she was puzzled: had she not had nearly nine decades to ponder this question herself, and since she, as the patient, was the one here to be looked after and indulged, should I not divulge who I was first? Self-disclosure by nurses was generally discouraged in the Nightingale school, but I chose to make an exception since I thought I might be caring for her for some time. I told her of how I’d grown up in fosters homes, of how as a travelling nurse—in the spirit of my former vagabond ways—I found it absolutely necessary to keep with me a locked suitcase of my most precious belongings—my own secret, portable archive.

These arbitrary details seemed to engage my new patient. While continuing her knitting, she basked me in follow-up questions—had I ever had children of my own? (No, I replied, I had always been more concerned with guarding life than creating it; also—though—I omitted this detail to her—I was a lesbian), and had I ever contacted my birth mother? (No again—a letter on my eighteenth birthday without a return address had been the extent of our communications). While telling her my story, I resolved to insist—given my job was, after all, to know her as best I could—might she share with me something about who she was?

Penelope was quiet for a moment, then placed the needles and the half-knit baby’s cardigan in her lap. From her basket of yarn, she removed a thin pile of photographs and began to shuffle through them.

She had been the mother of one and an author of children’s books. Her daughter, who was now in her sixties, was her pride and joy, and had grown up to be something quite like her. She too was an author, though her specialty was historical realism. Penelope had tried this genre at university herself and found she possessed no great skill in it.

“How time flies! I still remember the day I was swaddling her in her cradle.”

She glanced at the photographs spasmodically as she spoke, continuing her knitting.

“Look here—the nursery. You should have seen it the day I brought Laura home. Lucky she’d been a girl—you couldn’t tell beforehand in those days, you know—but of course a mother always has her own feelings about those sorts of things. The whole room was top to toe with everything I’d knitted for her.”

The photo she showed me was of Laura’s cradle. A spangled array of pink-and-red garter stitch; blankets, cardigans, and sun hats with ruffled brims. Indeed, the cradle was so full one could barely discern the child within it at all, and I had not the time to pinpoint a fugitive nose or hand belonging to the baby before she had moved on to the next photo.

We had been in the garden for two hours when the sun began to set and it was time for the evening rounds. Penelope had spoken of her past with a surprisingly feverish intensity. I offered to help her fold up her knitting—she’d completed the cardigan’s bonnet while we were talking—but she insisted on packing up the woolly mass alone.

“Whatever happens,” she said to me quietly, placing the photos in her basket, “I mustn’t lose my knitting needles.”

In the Spring, Penelope was moved into a larger room, one of those higher up in the hotel’s torso. This was a backhanded luxury: it meant she was getting sicker.

I had spent the first week of August helping her rearrange her possessions on the countertops and shelves of her new residence. “The nightlamp goes on the right side of the bed, “ she explained, “so that Henry can find it when he gets up in the middle of the night.” She had begun to speak casually of her husband, as if he were sitting just beyond his office door. I had wanted to ask her about him, but I stopped myself; when faced with blind spots in a patient’s memory, it was better to avoid them. Try to understand their reality instead of imposing your own, a nursing tutor had once told me.

The doll’s house had to go on the bookshelf’s second-lowest shelf, though she no longer knew why. Each morning, the miniature elephants rearranged themselves around the house. “I told you,” muttered Penelope one Sunday morning while finishing a row of purl. I was making the coffee and spreading jam on her toast. “That woman’s been playing with the elephants again. I heard her. Baby elephant—she was tucked in with the mother last night, but now she’s gone. Don’t you see?”

Having already attempted to explain to Penelope her own sleepwalking habits (she fervently denied having ever done anything of the sort), I tried to remember my tutor’s old advice, avoiding contradictions. “What woman, Penelope? Is she someone from around here?”

“She looks like Laura. But why does she keep running away from me?”

I tried to assure her it couldn’t have been Laura, since her and I were the only ones with keys to her room. If she was hearing noises in the night, it might’ve been the trees teetering against the windowpanes or the bats.

Tentatively, Penelope accepted this. Her knitting needles were stashed away in the drawer below the bookshelf, she said, and if the woman came back would I please make sure she didn’t touch them.

It was past midnight when the siren-like buzzer under my bed went off again. In the month since Penelope had moved rooms, nightmares had become a regular occurrence.

When I entered her room, she was still asleep; sat upright against the bed frame and muttering, digging her fingernails coarsely into her palms.

Her voice was sharp but trembling. “I’ve lost her—the knitting needles, they’re gone. Open the door for her—Laura—she’s gone!”

I sat beside her and tried to unfurl her clenched fists. Her face loosened and she opened her eyes.

“Will you be alright to get back to sleep, Penelope? Would you like me to fetch you a sleeping pill or your knitting?”

She shook her head, her gaze resting beside mine. “I knew you’d come back,” she said to Laura, or to me. “I tried darling, but I’m tired. What do I do when I’m tired?”

The nightmares worsened towards the winter’s end. By September they were no longer contained to the night, and Penelope was moved into palliative care.

As I folded up her belongings into four navy suitcases, I was overcome by a nauseous feeling that I was trespassing. So delicately had Penelope curated her room, bringing the nine decades of her life within reach, that it felt wrong she could not have a say in its dismantling. Her yarn basket, the doll’s house, the nursery books piled up beside the bed frame, even the forget-me-nots plucked from the garden only two days before: it was as if the weight of a thousand infinitesimal traces of her conjured up such a likeness that I could almost see the old woman’s figure from the corner of my eye. On the bookshelf, she had left her knitting needles.

As I folded up her clothes, the scent from her dresser was so concentrated that I had to pinch my nose. It smelt of old linen and castoreum, bereft and lonely, mingled with punches of lavender perfume.

The scent became more pungent near the bottom drawer, which snagged when I tried to open it. The insides were overflowing with knitted garments, all baby wear: cardigans in shades from mint to mauve, bibs, sunhats, pyjamas with tiny inbuilt shoes, and rompers with pockets that said in embroidered letters: LAURA. Some of the pieces were new, like the cardigan Penelope had been knitting our first afternoon in the garden. Others must have been older—I recognised one of the sunhats from the photo of Laura’s cradle—but none had any sort of fading or warped stitching, or any other sign indicating they’d been worn.

The photographs from the garden were tucked into the sunhat’s folds. I could look at them more closely now: they were mostly of Penelope’s former home, bathed in a golden, matronly light. Except there was no one at the dining table, no one listening to the radio whilst sunk deep into the couch. It was like looking at a real estate advertisement without the people in it.

The only photo containing faces was at the very bottom of the pile. It showed a young woman in a white patient’s gown, swaddling her newborn. September 1909, with Laura. Mnemosyne Women’s Home. Crossed out: for the Mentally Deranged. Under the pile of photos was a letter from Penelope to a Laura Havisham, with a stamp which said 1923. Laura had been fourteen. In stark lettering on the envelope’s back: RETURN TO SENDER.

So this had not been Penelope’s first time at the Mnemosyne. Laura was born here, when it had still been a women’s psychiatric facility. Then they had been separated, I supposed, for whatever reason Penelope had been admitted, and that was that: in the legal and most practical sense of the term, she was no longer a mother. Why Laura hadn’t replied or been able to reply to her letter, she would never know.

I thought about why Penelope had been so intent on knitting baby’s clothes, even as her memory declined. I had heard procedural memory was the last kind of memory to be lost—patients would remember the familiar route of their morning walk, but not their spouse’s face. Perhaps it was a similar thing with her knitting. Perhaps she was tracing her way back to a memory—to the short time when she’d been a mother—suspending the moments she had shared with Laura alongside the tick of the needles if not indefinitely, at least until the final row. Her apartment, too: enveloping yet forlorn, she had curated it as if it were a kind of family shrine. All in the hope of bringing her daughter back to her. A fractured, piteous light shone through the window and into the doll’s house. She was trapped in the memory like it were a children’s picture book.

Theoretically, I might have been Penelope’s daughter. Laura and I were the same age, after all; and despite the lure I felt towards objects from the past, I had never found my mother. Still, the chances were slim.

In the moment, those chances didn’t seem to matter too much. I hoped Penelope had been able to find the refuge she sought in her illness, if not anywhere else.

I picked up my mother’s suitcases to take to her room, following this final, indelible thread to where I was meant to be.

Carmilla, The monstrous feminine. With rot that lingers in her teeth, The pinprick on her lovers’ hearts And the blue spot beneath.

The guiding lady Languid in her form A servant of lust Without remorse.

You are freedom from man Their plots of marriage and female death

Who dominate the ending In Laura’s stead.

When your head becomes a symbol of Rebellion, Cut off at the throat so your Words no longer threaten him.

Your body, an object. Exposed. Penetrated. Your Violet Heart of Girlhood–Desecrated. Cremated.

Be boy’s dream Virgin-Whore, Spared of your spirit’s sin. Or be the hunter, Knowing self in resurrection.

Be she who dreams of naked dance and fire. Behold that familiar beast and go to die by Her Touch.

Be transformed into a creature Forever youthful. To join the grave-robbed darlings With bloody mouthfuls.

And you would dance, dear Laura, Unafraid and free. Comfort in your exclusion. Pride in Girl and Girl’s sovereignty.

Velvet x Doe

Kelsey Goldbro

Is It Now?

Casual

“Oh, you must be demisexual then,” my cousin remarked casually. I had just confessed that casual hookups left me feeling hollow and uncomfortable, explaining that without an emotional connection, physical intimacy felt meaningless to me.

I blinked, perplexed. Demisexual? The term was entirely foreign to me. As he explained this sexual orientation where one only experiences attraction after forming deep emotional bonds, I felt a curious mix of validation and resistance. Here was a neat, clinical label that apparently described my experience, yet I found myself bristling against it.

For years, I had operated under the refreshingly straightforward philosophy of “just fuck who you want to fuck.” The proliferation of increasingly specific labels struck me as unnecessarily compartmentalising something as fluid and personal as sexuality. Did I need this vocabulary to understand myself? Was my aversion to casual sex truly a manifestation of some inherent orientation, or simply a preference born from my values and experiences?

This moment crystallised a broader cultural shift I had been observing but struggled to articulate. We have moved from moral frameworks surrounding intimacy to psychological ones, with little room remaining for simple intuition or personal preference. Our choices must now be explained, categorised, and legitimised by established terminology. I just don’t feel right about casual sex, no longer a valid argument, but now a socially unacceptable position without explanation that needs to be couched in the language of orientations, attachment styles, or trauma responses.

The problem with this shift isn’t the existence of these new frameworks but their subtle coerciveness. They create the illusion that without proper classification, our experiences are somehow invalid or incomplete. They demand that we translate our instinctive knowing into acceptable jargon. This translation process often distorts or diminishes the original experience. When we force our complex, nuanced feelings about intimacy into predetermined categories, we risk losing the distinctive texture of our personal truth. This compulsion to classify can lead to an unhealthy external focus, where we become more concerned with how our experiences are perceived and validated by others than with how authentically they reflect our inner reality

We begin to doubt ourselves when our experiences don’t match the available terminology, wondering if perhaps there’s something wrong with us rather than recognising the limitations of language itself. The pressure to fit neatly into established frameworks can alienate us from our own authority, leaving us perpetually seeking external validation for deeply personal choices.

Human beings rarely construct their lives from first principles. We don’t coolly deliberate over a catalogue of values before selecting those that seem most rational. Rather, we intuitively apprehend what matters to us, what feels right or wrong, and only afterwards — if pressed — do we attempt to articulate why. This articulation is often imperfect, because language itself imposes categories upon experience that may not perfectly fit.

This path of self-doubt and perpetual revision can lead to a radical disconnection from oneself. What once stood firm within as a source of inner certainty becomes a haze of competing voices, none truly one’s own. By seeking justifications palatable to others, we may forfeit the only justification that ever truly mattered: our own internal compass.

The framing of sexual choices exclusively in psychological rather than moral terms has other risks. When we frame our preferences solely as psychological phenomena rather than personal choices, we might miss opportunities to reflect on whether our actions align with our deeper values. The language of determinism, rather than agency, can disconnect us from our own power to shape our own intimate lives.

This is not to advocate for shame-based sexual morality or religious prohibitions. Rather, it’s to suggest that perhaps the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction. Between stern moral judgments and clinical diagnoses, lies the fertile ground of personal intuition—the quiet knowing that certain choices feel right for us while others don’t, regardless of whether those feelings can be neatly labelled.

When I reflect on my own resistance to casual sex, I recognise now that I was searching for a way to honour my intuition without succumbing to either religious conservatism or psychological determinism. I didn’t need the term “demisexual” to validate my experience, though I understand how such labels can provide comfort and community to others.

What I did need — what perhaps we all need — is permission to trust ourselves. To acknowledge that not every preference requires explanation or categorisation. That sometimes “because it doesn’t feel right to me” is reason enough.

The paradox of our label-obsessed culture is that in our quest to name and validate every possible variation of human experience, we may inadvertently constrain that very experience. By insisting that every feeling be classified, we create new hierarchies of legitimacy. Those whose experiences neatly align with recognised categories find validation, while those with more ambiguous intuitions may feel pressure to contort themselves into recognisable shapes.

I found myself struggling to articulate boundaries around intimacy because I feared my reasons wouldn’t hold up under scrutiny. “I can’t just say I don’t want to,” I thought to myself, “I need a better reason.” But why? When did my own intuitive sense of what feels right or wrong for my body become insufficient justification?

Perhaps the most radical act in a culture obsessed with external validation is to reclaim the authority of personal knowing. To say: I do not need to justify my intimate choices with acceptable terminology. I do not need to pathologise or diagnose my preferences to make them legitimate. I can simply know what I know, feel what I feel, and act accordingly. We have become so zealous in our search for causal explanations that we often refuse to accept the simpler truth: sometimes people simply are who they are.

This isn’t to suggest we shouldn’t examine our motivations or seek to understand ourselves better. Self-reflection is valuable, but there’s a profound difference between curiosity about one’s inner landscape and the anxious need to justify one’s existence through socially sanctioned categories.

If there’s freedom to be found in this confusing terrain of modern intimacy, perhaps it lies in recognising that we need not choose between rigid moralism and clinical categorisation. We can acknowledge that our choices may be influenced by psychology, values, culture, and countless other factors without feeling compelled to reduce them to any single framework.

The next time someone offers you a label for your experience, consider whether it illuminates something valuable or merely repackages what you already know. Remember that you are not required to explain your intimate boundaries in terms others find convincing. Your intuition, your sense of what feels right or wrong for your body and spirit, is a valid guide — perhaps the most valid guide — through the complex landscape of human connection.

I’ve made peace with understanding my own preferences around intimacy. Whether others find connection through casual encounters or committed relationships, what matters is that we each honour our authentic selves. For me, recognising that I need emotional connection isn’t a part of my sexuality, nor a moral statement about how others should navigate their intimate lives — it’s simply my truth. In embracing that, I’ve found more freedom than any category could ever provide.

Marc Paniza