Lawyer The Arkansas

PUBLISHER

Arkansas Bar Association

Phone: (501) 375-4606

www.arkbar.com

EDITOR

Anna K. Hubbard

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Karen K. Hutchins

PROOFREADER

Cathy Underwood

EDITORIAL BOARD

Caroline R. Boch

Turquoise Early

William Taylor Farr

Abigail Grimes

Jim L. Julian

Tory Hodges Lewis

Drake Mann

Tyler D. Mlakar, Chair

Michael A. Thompson

Brett D. Watson

Amie Schoeppel Wilcox

David H. Williams

Nicole M. Winters

OFFICERS

President

Jamie Jones Walsworth

President-Elect

Representative Carol Dalby

Immediate Past President

Kristin L. Pawlik

President-Elect Designee

Tim Cullen

Secretary Glen Hoggard

Treasurer

Marc P. Martinez

Parliamentarian

Brent J. Eubanks

YLS Chair

Samuel W. Mason

BAR ASSOCIATION STAFF

Executive Director

Karen K. Hutchins

Director of Operations

Kristen Frye

Finance Administrator/CPA

Staci Clark

Publications Director

Anna K. Hubbard

Office & Data Administrator

Cynthia Barnes

Professional Development Coordinator

Lisa McCormick

Information Technology Specialist

Rachel Henderson

features

Arkansas Bar Association Members

The Arkansas Lawyer (USPS 546-040) is published quarterly by the Arkansas Bar Association. Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, Arkansas. POSTMASTER: send address changes to The Arkansas Lawyer, 1401 W. Capitol Ave., Suite 170, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201. Subscription price to nonmembers of the Arkansas Bar Association $35.00 per year. Any opinion expressed herein is that of the author, and not necessarily that of the Arkansas Bar Association or The Arkansas Lawyer. Contributions to The Arkansas Lawyer are welcome and should be sent to Anna Hubbard, Editor, ahubbard@arkbar. com. All inquiries regarding advertising should be sent to Editor, The Arkansas Lawyer, at the above address. Copyright 2025, Arkansas Bar Association. All rights reserved.

Lawyer

Advertise in the next issue of The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

President: Jamie Jones Walsworth; President-Elect: Representative Carol Dalby; Immediate Past President: Kristin L. Pawlik President-Elect Designee: Tim Cullen; Secretary: Glen Hoggard; Treasurer: Marc P. Martinez Parliamentarian: Brent J. Eubanks; YLS Chair: Samuel W. Mason

Trustees:

District A1: Elizabeth Esparza, Samuel W. Mason, William M. Prettyman, Lindsey C. Vechik

District A2-A3: Payton C. Bentley, Kelsey Boggan, Evelyn E. Brooks, Jason M. Hatfield, Michelle Rene’ Jaskolski, Sarah C. Jewell, George Rozzell, Russell B. Winburn

District A4: Kelsey K. Bardwell, Craig L. Cook, Brinkley B. Cook-Campbell, Dusti Standridge

District B: Brooke Blackwell, Randall L. Bynum, Mark Kelly Cameron, Thomas M. Carpenter, Bob Edwards, John A. Ellis, Bobby Forrest, Joseph Gates, Michael K. Goswami, Steven P. Harrelson, Michael M. Harrison, Jim Jackson, Anton L. Janik, Jr., Victoria Leigh, Skye Martin, Kathleen M. McDonald, J. Cliff McKinney II, Jeremy M. McNabb, Molly M. McNulty, Meredith S. Moore, Andrew Norwood, John Ogles, Casey Rockwell, Lauren Spencer, Aaron L. Squyres, Caitlin C. Stepina, Danyelle J. Walker, Patrick D. Wilson

District C5: William A. Arnold, Joe A. Denton, John T. Henderson, Brett D. Watson

District C6: Bryce Cook, Paul N. Ford, Jeffrey W. Puryear, Paul D. Waddell

District C7: Kandice A. Bell, Robert G. Bridewell, Sterling T. Chaney, Ledly Jennings

District C8: Meagan E. Davis, Amy Freedman, John S. Stobaugh, Joshua R. Thane

Ex-officio Members: Judge Craig Hannah, Judge Chaney W. Taylor, Vicki S. Vasser, Dean Cynthia Nance, Dean Colin Crawford, Glen Hoggard, Eddie H. Walker, Jr., Karen K. Hutchins

Board of Trustees

Class of 2000

Congratulations to Members Celebrating Their 25th Year of Practice

Ryan A. Bowman

Andrea Brock

Bryan Burns

Charles Jason Carter

Holli Fawcett Clayton

Sarah M. Cotton Patterson

Jennifer Craun

Laura Lee Cunningham

Jennifer Woodruff Douglas

Dawn Christine Egan

James R. Estes, Jr.

Timothy C. Ezell

M. Cody Flynn

Amy L. Grimes

Julie M. Hancock

Maureen H. Harrod

Glen Hoggard

Scott Hunter, Jr.

Randi F. Hutchinson

Timothy C. Hutchinson

Carol Johnson

Terry Goodwin Jones

Duane A. Kees

Shala J. Klutts

Cynthia Worthing Kolb

Tamara Gail Martin

John J. Mikesch

Joshua C. Nelson-Archer

J. Richard Newland, Jr.

Brianna Spinks Nony

Stephanie I. Randall

Brian W. Ray

Steven T. Robbins

Kyle B. Russell

Derrick W. Smith

Jeremy Snell

Eric Soller

R. Shane Strabala

Jay T. Taylor

John Vines

Nicole Sippial Williams

Susan P. Williams

Perry L. Wilson

Daniel Yates

Oyez! Oyez!

Accolades

Meredith Moore, Rainwater, Holt & Sexton, received the 2025 Odyssey Medal for Service to the World from Hendrix College. Matt Boch of Kutak Rock LLP has been named the Lawrence L. Larry Lasser Tax Judge of the Year for 2025 for his service as Chief Commissioner of the Arkansas Tax Appeals Commission.

Appointments and Elections

Don Curdie, Little Rock, was appointed to the Tax Appeals Commission. Sarah Jewell, McMath Woods, has been named to the Board of Directors for the Arkansas JLAP Foundation.

Word About Town

Hilburn & Harper, Ltd. announced the addition of Mackie M. Pierce, a highly respected attorney and former Circuit Judge, to the firm’s roster of distinguished legal professionals. Caitlin E. Campbell has joined Jones, Jackson, Moll, McGinnis & Stocks, PLC as an associate. Quattlebaum, Grooms & Tull PLLC announced the addition of three associates in its Little Rock office — E. Jonathan Mader, Madison A. Dedrick, and Jacob H. James — and one in its Northwest Arkansas office, Carter M. Wade

Send your oyez to ahubbard@arkbar.com

Louise E. Tausch, Atchley, Russell, Waldrop & Hlavinka LLP, Texarakana, was honored with a Golden Gavel award at the 2025 Annual Meeting for her work on the Personnel Committee. She is recognized here after being inadvertently missed in the Summer issue.

Anna Hubbard Marks 20 Years with ArkBar

Anna Hubbard, Publications Director for the Arkansas Bar Association, celebrates 20 years of service. She leads The Arkansas Lawyer magazine and the Editorial Advisory Board and oversees the Association’s marketing, communications, and publications. She also serves as staff liaison to the Young Lawyers Section.

“Anna is the quiet force guiding the Association’s marketing, communications, and member engagement. For 20 years, she has led The Arkansas Lawyer with professionalism and care, helping make it the state’s premier peer-reviewed legal publication,” said Executive Director Karen Hutchins.

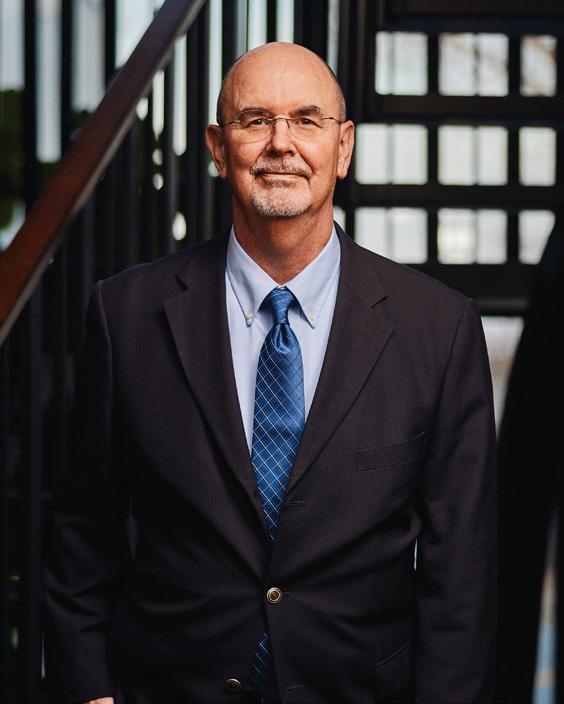

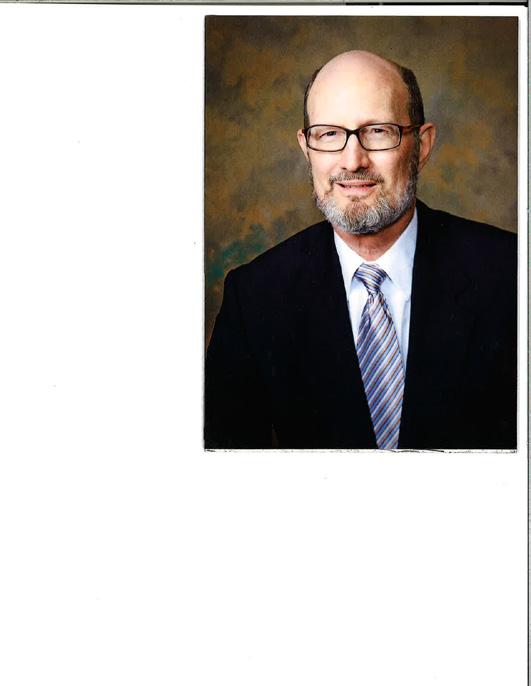

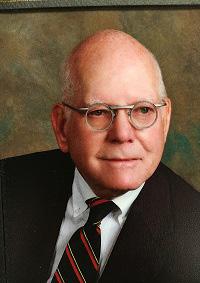

Tim Cullen elected the new ArkBar President-Elect Designee

Tim Cullen of Fayetteville was elected President-Elect Designee without opposition at the close of nominations on October 6, 2025. He will begin his one-year term as President-Elect in June 2026 and will assume the office of President at the 2027 ArkBar Annual Meeting.

Tim graduated from the University of Arkansas with a B.A. in Communications and earned his J.D. from the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1996. He clerked for Judge Terry Crabtree at the Arkansas Court of Appeals before entering private practice.

He has been active in the Arkansas Bar Association, serving as Chair of the Young Lawyers Section and as a member of the Board of Governors, House of Delegates, Board of Trustees, and Jurisprudence and Law Reform Committee. He also chaired the Governance Drafting Committee and has received three Golden Gavel Awards for his bar association service. He is a Fellow in the Arkansas Bar Foundation, where he received the Foundation’s Writing Award for an article in The Arkansas Lawyer on judicial campaign finance. He also served a term on the Board of Governors for the Arkansas Trial Lawyers Association.

In his spare time, Tim is an adult volunteer with Scouting America and serves on the Executive Board as a past president of the Natural State Council of Scouting America.

Tim has participated as lead counsel on appeal in well over 250 cases before the Arkansas Supreme Court, Arkansas Court of Appeals, and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. He has served on the AMI–Civil Committee, the Arkansas Supreme Court Task Force on Electronic Filing, and the 8th Circuit Federal Practice Committee.

Tim relocated from Little Rock to Fayetteville two years ago. His wife, Dr. Lauren Poindexter, is a sports medicine specialist practicing in Fayetteville. Tim’s three kids are grown up. Katie rides the subway to work every day from Brooklyn to Manhattan. Connor is in his third year of law school at UA Fayetteville. And Quinn is a sophomore accounting major at Indiana. Their dog, Olaf, keeps the nest from feeling too empty.

Icing Out Burnout

Burnout……that feeling of being emotionally exhausted, disrupted sleep, anxiety, unable to accomplish your tasks. It is a feeling that may make a lawyer contemplate leaving the profession entirely. According to a survey by Bloomberg Law, 52% of lawyers reported feeling burned out “most of the time.” Those surveyed identified feeling disconnected, having a heavier workload, and an inability to focus on work tasks. It should not be surprising that lawyers are prone to burnout because we are as a profession a group of people who value being busy and feeling accomplished. After all, the consequences of burnout can be dire. According to the American Bar Association, losing lawyers to burnout costs firms between $200,000 and $500,000 each. The personal cost is higher. Lawyers have higher rates of alcoholism and drug addiction. A 2023 research project commissioned by the California Lawyers Association and the District of Columbia Bar concluded that lawyers are “twice as likely” as the general population to contemplate suicide.

By the way, if you are a woman lawyer, you are more likely to experience burnout. And if you are a litigator, you are more likely to experience burnout. These statistics do not bode well for someone like me—a woman litigator. Knowing then how to combat burnout is important for our well-being and success, personally and professionally. Over the last year, in which I have seen a lot of personal changes and an extremely busy schedule, I have realized the following was helpful in avoiding burnout: Educate yourself. Many of us are from a generation that simply does not talk about things like burn out. Honestly, I was gifted a shirt that says “suck it up, buttercup” because it is a self-philosophy. However,

Jamie Jones Walsworth is the President of the Arkansas Bar Association. She is a partner at Friday, Eldredge & Clark, LLP in Little Rock.

the reality is that I cannot do all things on my own. (This was a hard lesson for me to learn!) Educate yourself about the topic, and recognize that it is okay to ask for help, and it is okay for others to need help. Articles and resources like those presented in this issue may provide education for you.

Have a support system. Friends, family, co-workers. Normalize talking about your feelings with those around you. ARJLAP is an incredible confidential resource to talk about what you are experiencing. For me—an incredible group of friends and my husband remind me often to take breaks from my task lists and to slow down and engage with them. It is okay, they remind me, to take a nap when I need it, or watch Saturday football. (Although the Hogs have not been good for my mental health as of late.)

Set realistic goals. Small goals that you can take on with your schedule are important. Celebrate meeting those goals. Wins can be big or small, but celebrate them with your support system. I will, for example, celebrate finishing this article here shortly.

Turn off social media. Books like The Anxious Generation, by Jonathan Haight, point to neurological studies to show that social media and technology are re-wiring our brains and making our attention spans shorter. Even if you reject those conclusions, it does not take scientific research to know that social media gives a false sense of the world around us. Taking a break or turning it off and engaging with the people around us helps us feel centered in the world. I have noticed myself disengaging by watching reels on social media and realizing that I had done it for hours. What a waste of time, and it did nothing to relieve any anxiety. I did, however, feel a need to shop and buy the newest trend.

Hobbies. For me, my lifeline from a busy schedule is reading. Anything, Everything. Reading gives me a sense of disengagement from whatever stressor is impacting me and lets my mind breathe a little bit. My favorites so far this year, just in case you need a book to read: August Lane by Arkansas lawyer and Bowen Professor Regina Black, My Friends by Fredrik Backman, and Mississippi Blue 42 by Arkansan Eli Cranor (a whole fictional universe where the Razorbacks are national champion contenders every year!).

Exercise. I am told that this helps, and I should do more of it. Apparently, it produces endorphins that are great at combating anxiety and stress. I will try it sometime and report back. All joking aside, a nice autumn walk can often do wonders for my stress level.

I am not an expert in mental well-being, but I am open to learning more about how to be a better, more productive lawyer and live a healthier life for myself and my family. The younger generation of lawyers are better than my generation at discussing these issues, and have some tricks to teach an old lawyer like me.

On October 16, 2025, the Arkansas Supreme Court issued a per curiam that it is considering a change to the minimum continuing legal education rules, which would include a mandatory well-being hour. Comments are open until December 31, 2025, for everyone to weigh in and let the Arkansas Supreme Court know your opinion—pro or against. You can email them to rulescomments@arcourts. gov or send to Kyle Burton at the Justice Building.

Building Connections, Strengthening the Bar

Arkansas Bar Association’s Young Lawyers Section has started off with a bang! First and foremost, we had a rearranging of our board members and have brought in some outstanding representation from District C—let’s give a warm welcome to Eric Brown and Cordell McDonald. Now that we have a fully functioning and eager team, it is time to get to work.

District B members Eli Cummins, Amanda Kennedy, Hayley Ferguson, and Sydney Rasch, along with At-Large Representatives Beau Duty and Grace Fletcher, planned a social mixer on October 30. It was a great opportunity for newly practicing attorneys and law students to connect in a relaxed, casual setting and build relationships beyond the classroom and courtroom.

Further, District C members Lindsey Roy-Brown, Stephen Cory, Eric Brown, and Cordell McDonald are working to host a social mixer in South Arkansas sometime this Winter or early Spring. Similarly, District A members Brittany Hawkins, Martha-Kay Crowder, Marcus Priest and I are finalizing plans to hold a social mixer in Northwest Arkansas to happen this Spring. Many will say that by the time this executive year has ended, the social will be mixed all across Arkansas!

Networking is a critical factor in our practice and young lawyers are crucial members of the Arkansas Bar. The more young lawyers we have who are connected to each other and the Arkansas Bar and local Bars, the better those Bars will become. The importance for law firms and seasoned

Samuel W. Mason is the Chair of the Young Lawyers Section. Sam is a trial attorney at the Oliver Law Firm in Rogers.

lawyers to help young lawyers cannot be stated enough. As a younger lawyer myself, I can attest to this. Fortunately, a majority of the elder lawyers I work and interact with are very able and willing to help, whether it be to better my knowledge of the law, better my skills, or provide everyday professional and personal tips. As a matter of fact, in my very first jury trial against a country-wide corporation with well-versed lawyers, the Defense lawyers helped me in more ways than one and I will never forget that. The more help a young lawyer has from seasoned lawyers (and sometimes vice-versa), the better the practice of law becomes and, maybe more importantly, the better that lawyer becomes as a person of good will and a servant to others.

Stay tuned for more things happening! ■

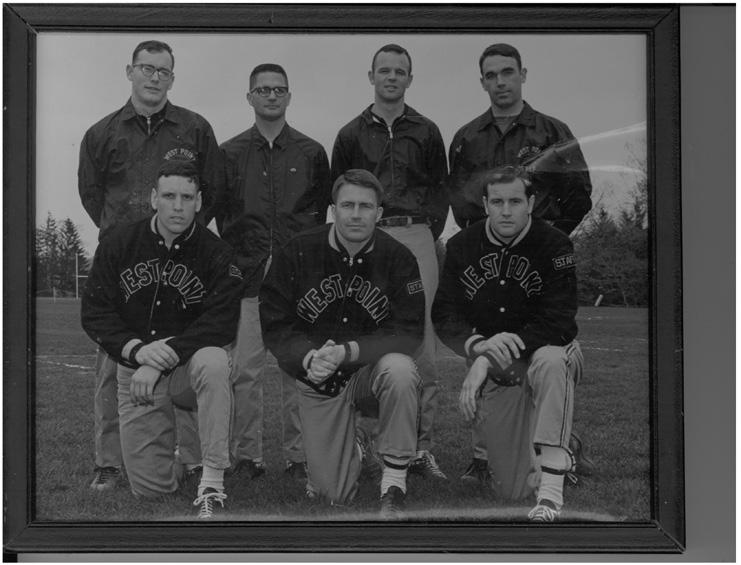

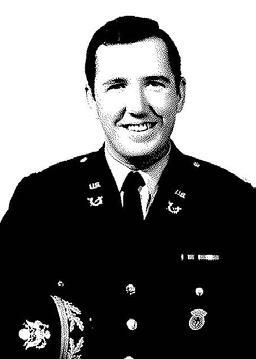

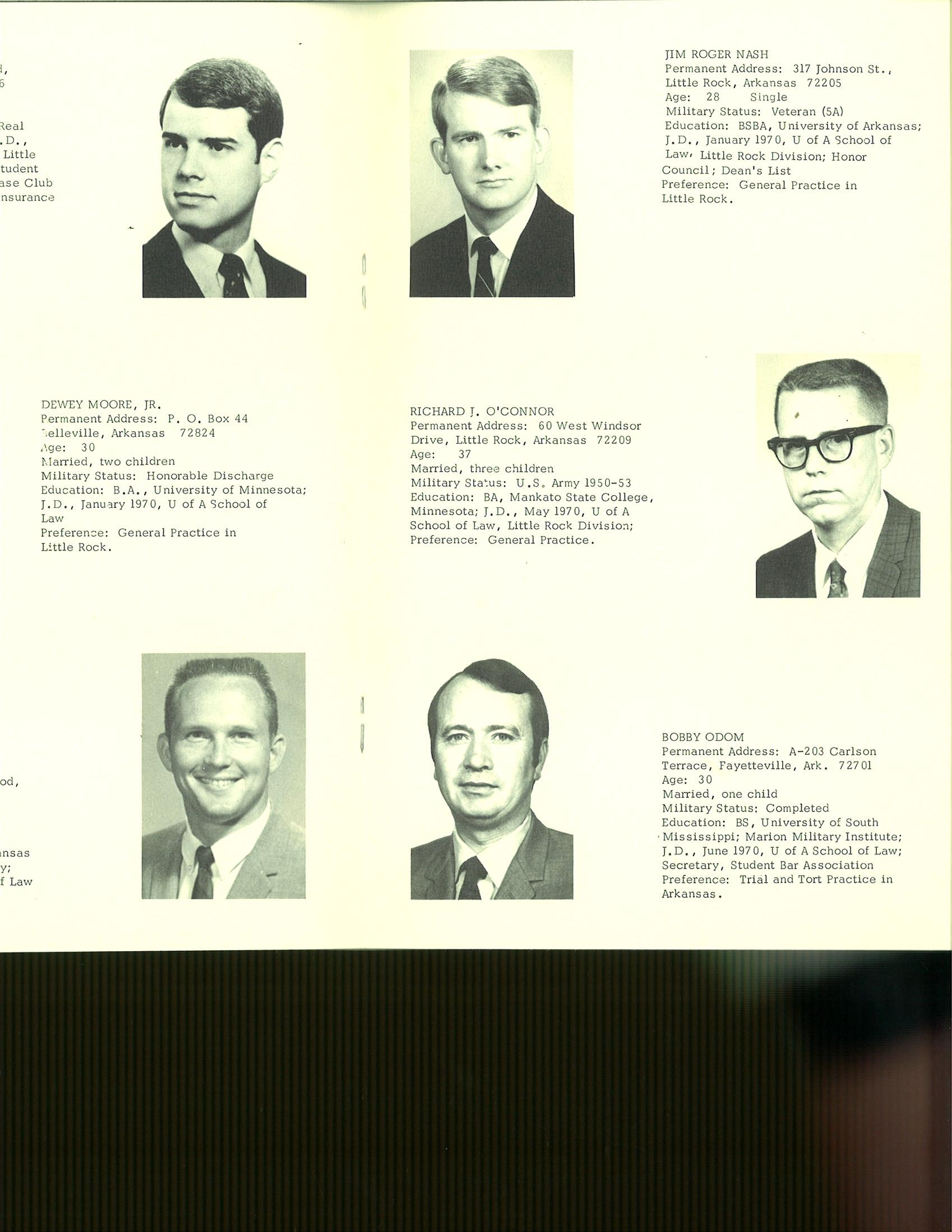

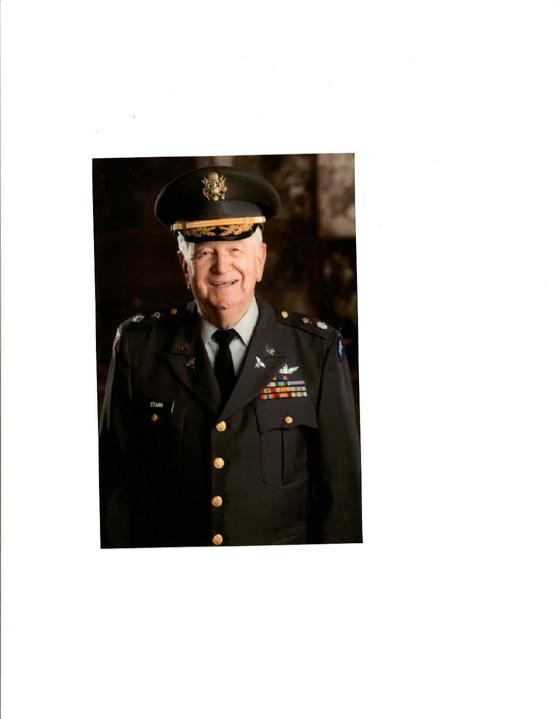

Honoring

ArkBar Members Who Serve in the U.S. Military

Celebrating the Courage and Dedication of Our Military Members

We proudly honor Arkansas Bar Association members who have served in the United States military. Their courage, dedication, and sacrifice have made a lasting impact on our nation and our profession.

A full list of members who have served—including posthumous recognitions—is available on our website. While this tribute reflects many who have served our country with honor, we know it may not include everyone. If you know a member who should be recognized in future publications, please contact the editor so their service can be honored.

Please visit ArkBar’s Tribute to Members who Have Served in the Military at www.arkbar.com.

Michael D. Barnes

Marilyn Dearien Barton

Zach Baumgarten

Jonathan W. Beck

Joe Benson

Allen W. Bird II

Judge Denzil Keith Blackman

Daniel C. Blaney

John Dudley Bridgforth

Charles A. Brown

Major Natalie G. Brown

LeAnne Pittman Burch

William Jackson Butt, II

Anthony B. Cameron

Worth Camp, Jr.

Gene C. Campbell

Jennifer Carlisle

Charles L. Carpenter, Jr.

Jerry W. Cavaneau

John S. “Jack” Cherry

Murray Claycomb

Nathan Coulter

Justice Paul Danielson

Thom Diaz

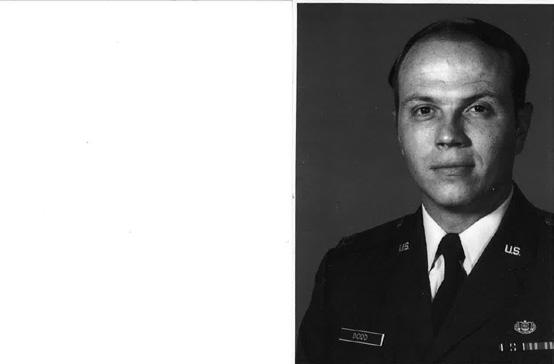

Jerry Dodd

Greg Downs

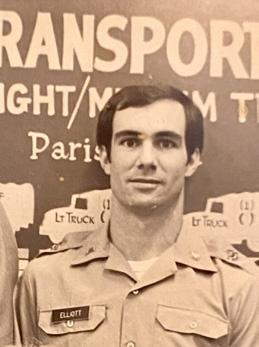

Don R. Elliott, Jr.

Bob Estes

Peter G. Estes, Jr.

John C. Everett

Judge Vic Fleming

William Charles Frye

Sam Gibson

Martin G. Gilbert

John P. Gill

Morton Gitelman

James C. Graves

Ron Griggs

Judge Wayne Gruber

Will Gruber

Judge David F. Guthrie

Stuart W. Hankins

Dick Hatfield

William D. Haught

LaQuetta S. Henry

Robert L. “Skip” Henry

Donald C. Hill

Randal Hobbs

Cyril Hollingsworth

Roy Douglas House

James W. Hyden

Greg S. James

C. Cole Jeffries, Jr.

Glenn W. Jones

Robert L. Jones, Jr.

Dak Kees

Hugh R. Kincaid

Joseph M. Kraska

Richard L. Lawrence

Tim Leathers

M. Melissa Lee

John C. Lessel

Fletcher C. Lewis

Stark Ligon

Phillip A. McGough

Joseph P. McKay

Cody A. McKinney

J. Conley Meredith

Cal McCastlain

James McMenis

Henry N. Means, III

Russ Meeks

George B. Morton

Lee Muldrow

J. R. Nash

Edward Nelson

Judge David Newbern

Jim Nickels

Anthony (Tony) W. Noblin

Alan J. Nussbaum

Richard C. Ourand, Jr.

Hugh Overholt

William L. Owen

Michael Parker

Charles (Charlie) W. Pearce

Ellis Lamar Pettus

David Dero Phillips

John M. Pittman

George Plastiras

David M. Powell

Donald E. Prevallet

Joseph Purvis

Brian D. Rabal

John “Buddy” W. Raines

Gordon S. Rather, Jr.

George Ritter

Fred Roberson

William S. Robinson

Adam M. Rose

James (Jim) A. Ross, Jr.

Thomas S. Russell

Marissa A. Savells

Corey Seats

Brenda Simpson

Damon C. Singleton

Ted C. Skokos

Berl S. Smith, Jr.

James E. Smith, Jr.

Judge Kim Smith

Richard H. Smith

Scott E. Smith

Rex Earl Starr

Paul Suskie

F. Mattison Thomas III

Bass C. Trumbo

Lonnie C. Turner

Richard E. Ulmer

Fred Ursery

Glenn Vasser

Magistrate Judge Joe Volpe

Wyman R. (“Rick”) Wade, Jr.

Stan L. Warrick

John Dewey Watson

Phillip Wells

David H. Williams

W. Jackson Williams, Jr.

Jeffery D. Wood

Daniel H. Woods

Judge Wm. Randal Wright

Steven S. Zega

Bird A.

Campbell Blackman

Brown Burch

Butt Camp

Coulter Beck Benson Bridgforth

Dodd Elliot

Downs

Gitelman

Graves Griggs

Gruber Wa. Gruber Wi. Guthrie

Barnes

Hankins

Haught

Hill Hobbs

Hyden

James Jones Kees

Kraska

Danielson

Holt

Fleming

Baumgarten

Diaz

Claycomb

Cameron

McGough Ligon

Turner

Nash

Meeks

McKay McMenis

Meridith

Williams

Wade

Nussbaum

Purvis

McKinney

Parker Muldrow

Vasser

Noblin Pearce

Skokos

Smith R. C. Starr Trumbo

Shape the Future of ArkBar: Leadership Opportunities Election Cycle Timeline

The Arkansas Bar Association thrives because of the dedication and leadership of its members. Serving in an ArkBar leadership role is one of the most impactful ways to help shape the future of our profession, strengthen our community, and ensure that the voices of Arkansas lawyers are heard.

Leadership in ArkBar offers opportunities to collaborate with colleagues across the state, contribute to the direction of the Association, and make a lasting impact on the legal community.

Questions? Contact Karen Hutchins at khutchins@arkbar.com or 501-801-5663.

Nominations are now being collected for the following positions:

A1 4 1

A2, A3 8 2 Washington

A4 4 1 Boone, Carroll, Crawford, Franklin, Johnson, Logan, Madison, Newton, Sebastian B9-15 28 11 Pulaski

C5 4 1 Baxter, Cleburne, Conway, Faulkner, Fulton, Independence, Izard, Jackson, Lawrence, Marion, Perry, Pope, Randolph, Searcy, Sharp, Stone, Van Buren, White, Yell

C6 4 1 Clay, Craighead, Crittenden, Cross, Greene, Lee, Mississippi, Monroe, Poinsett, Prairie, St. Francis, Woodruff

C7 4 2 Arkansas, Ashley, Bradley, Calhoun, Chicot, Clark, Cleveland, Columbia, Dallas, Desha, Drew, Grant, Jefferson, Lincoln, Lonoke, Ouachita, Phillips, Union

C8 4 1 Garland, Hempstead, Hot Spring, Howard, Lafayette, Little River, Miller, Montgomery, Nevada, Pike, Polk, Saline, Scott, Sevier

Total Trustees 60 20

ArkBar’s Statement of Ownership for USPS is printed here. PS Form 3526 is required by the Post Office annually to show proof of continued eligibility for mailing under a Periodical Permit.

Board of Trustees (open seats) –nomination deadline January 26, 2026

Secretary – nomination deadline January 26, 2026

ABA Delegate – nomination deadline January 31, 2026

President-Elect – nominating petitions due Monday, October 5, 2026

Just a Small Town Arkansas Lawyer

By Donald K. Campbell, III

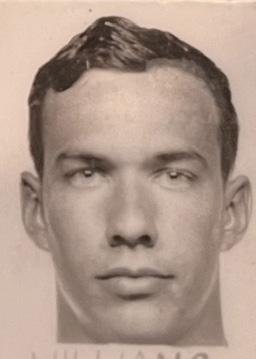

He went to law school, came back home, went into practice with his father and older brother, then spent the next 57 years practicing law in his own hometown. On the surface, Adrian Williamson’s career followed a path like many attorneys who end up going into the family business. Scratch a little deeper, and you’ll find that he tucked a lot more into those five decades than just wills and trusts and The Law.

Military service, aviation, astronomy, photography, archeology, banking, church work, community leadership—he was a man with a broadly curious mind and boundless energy who made his mark far beyond the walls of his law office and the courthouse. And even though his military career took him around the world and through two world wars, he always came home to Drew County and the beloved town of his birth, Monticello, Arkansas.

The Early Years

Born at home on November 7, 1892, Adrian was the third child of J. G. and Lulu Williamson. His brother, Lamar, was six years older and a major influence in his life, but Adrian never knew his sister, Corinne, who died the year before he was born. Due to problems with asthma, he was sent to live with relatives around 1902 in the drier climate of Brownwood, Texas, where brother Lamar was a student at Daniel Baker College, a Presbyterian school there.

After graduating from high school, Adrian entered the New Mexico Military Institute in the fall of 1909 then transferred the following year to the College of Charleston in South Carolina. In the fall of 1911, he transferred to Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, where he graduated with a bachelor of science degree in 1913. His many interests and achievements in college included playing on the football team, rowing on the varsity team, and earning a scholarship in philosophy.

He entered Harvard Law School that fall and finished his formal education two years later in June of 1915. Among his professors were Samuel Williston, Roscoe Pound, Felix Frankfurter, and Joseph Beale. In an interview decades later, his older daughter Ann said, “One deep regret, even small embarrassment to him, was that he never actually graduated from Harvard. A relative who lived in the East died about the time of his final exams, and Father was required to leave school to accompany the body on the train back to Arkansas. Such was the priority of family loyalty, but it haunted him for years,” she added.

Diploma notwithstanding, he did in fact finish law school and was duly examined by the Bar of Arkansas and admitted to the Bar on July 15, 1915—less than a month after returning home from Harvard. He then went into practice with his father, J. G., and brother Lamar, expanding the firm’s name to Williamson, Williamson & Williamson.

Donald K. Campbell, III (1958–2025) was a partner at Campbell, Grooms & Spaulding in Little Rock. He submitted this article shortly before his passing in August 2025.The Arkansas Bar Association is honored to share his reflections on his grandfather’s legacy and to remember Don Campbell’s own lasting contributions to the Arkansas legal community.

A Call to Serve

Two years later in April of 1917, the United States entered World War I, and Adrian answered the call to serve his country by volunteering for military service. He enrolled as a cadet in May at Fort Logan H. Roots outside North Little Rock and was soon commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Artillery Corps at Camp Pike on August 15. In 1918, he was transferred to the U.S. Army Air Corps where he was sent for flight training at Kelly Field near San Antonio, Texas. There he learned to fly the Curtiss JN-4 biplane, also known as the “Spinning Jenny.” He received additional training at Payne Field in Mississippi and Wilbur Wright Field in South Carolina, earning his pilot’s wings and a love of flying in August of 1918.

He was assigned to active duty in Europe and spent the fall in Hoboken, New Jersey, waiting to sail to the Continent, but the war ended on November 11 that year. He was discharged from active duty in the U.S. Army on December 6.

This would not be his last time in uniform.

Back to Monticello and The Law

After returning home, he settled down to practice law and pursue his other interests. One of those “interests” was a young woman from Pine Bluff named

Catherine Montgomery, whom he met at a cousin’s house in Little Rock. They fell in love and were married on April 9, 1924, at the First Presbyterian Church in Pine Bluff. The newlyweds moved to Monticello and into the same house where his parents had been living when he was born. He and his bride started their own family a year later when their first child, Adrian, Jr., was born in that same house on August 20, 1925.

Adrian continued to build his law practice during the 1920s and established a reputation as a careful and successful civil attorney. He also was a booster and builder in the community and an energetic member of First Presbyterian Church.

Catherine Ann, their second child, was born in a hospital in Pine Bluff on November 9, 1928, two days after her father’s birthday. Named after her mother, she became known as Ann. Their third child, Margaret, was born on August 8, 1933. The growing family lived in a cottage deeded to them by Adrian’s father, and they expanded it around the same time Ann arrived. Set near the top of a hill, the house came with a pecan orchard and a fenced yard to protect the lawn and garden from wandering cows.

According to his nephew Lamar, Jr., Adrian grew tired of having to stop to open the gate each time he drove home, so he invented a mechanical system of

levers and cables that opened the gate when a car drove over hinged metal panels in the driveway. “He delighted to surprise first-time visitors by driving up the hill at full tilt, swinging right into the driveway, and watching their reaction when the closed gate miraculously opened while they braced for the crash,” Lamar said.

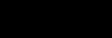

A Man of Many Interests

Adrian first took up astronomy in 1929, and in 1933 he designed and built an observatory of white-washed brick crowned with a metal dome near the house. The dome had a sliding panel and could be rotated or lifted completely out of the way for a clear view of the sky. Inside this “Astrohut,” he installed a telescope on a tripod and an enormous chair he’d designed to go with it. At five and a half inches in diameter, the telescope was reportedly the largest of its kind in the state at the time and one of the largest privately owned telescopes in the USA.

Thanks to the photographic skills of his friends Les Pomeroy and Gene Conner, Adrian also learned the art of photography and eventually built his own darkroom, which was a marvel in itself in Monticello, AR in 1929. Basing it on the adobe houses of indigenous people in the West, he had workmen build it using wet soil and Drew County clay tamped

into wooden forms. The exterior was then covered with a rough plaster of local materials and whitewashed lime. This simple building served for many years as the source of family photo albums made, developed, and printed by his own hands. Beyond astronomy and photography, Adrian also developed an interest in local archeology and would take the family on Sunday outings to investigate prehistoric Native American mounds in and around Drew County. He also installed a ham radio in the small vestibule of the Astrohut and carried on conversations with other ham operators around the world.

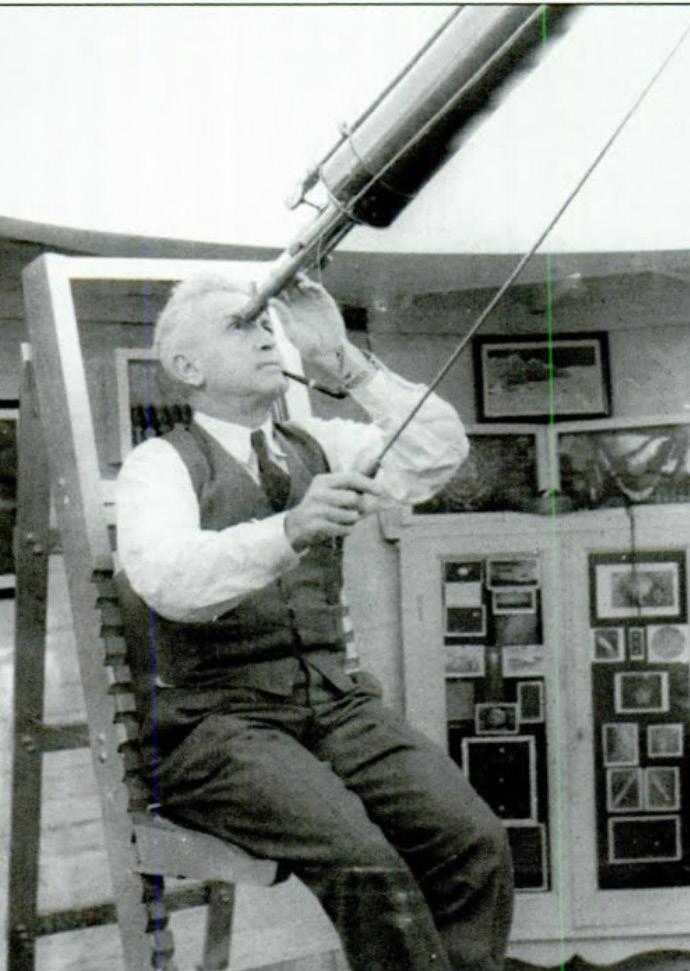

A Return to the Skies

Even though Adrian was discharged from the Army in 1918, he never gave up his love of flying and continued to serve in the U.S. Air Service Reserve after the war. In June 1923, he was promoted to first lieutenant and became one of the founding members of the 154th Observation Squadron of the Arkansas Air National Guard when it was organized in Little Rock in 1925. Two years later, the 154th saved many lives through its aerial reconnaissance during the great flood of 1927, and one of the photographs Adrian took of the devastation hung in his home study for years.

He was promoted to captain in 1927 and to major in 1933 when he was placed in command of the 154th. While

he also practiced law in Monticello, he was Commander of the 154th Squadron from July 1, 1933 to September 1, 1941. War returned to Europe in the late 1930s, and by the summer of 1940, his drills with the Air National Guard had taken on a new urgency. When the 154th was mobilized into federal service in September 1940, he declined an appointment as adjutant general of Arkansas and instead chose active duty with the Army Air Corps. The squadron was ordered to Fort Sill in Oklahoma for intensive training that year, and Adrian and his family moved with it. His leadership in the 154th squadron resulted in at least 12 officers becoming full colonels, and over half of the squadron became officers during WWII.

The War Years

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, Adrian and the family moved again, this time to Washington, D.C., where he was assigned to the Air Plans Division of the Army Air Corps. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the spring of 1942 and helped plan General James “Jimmy” Doolittle’s successful bombing raid over Tokyo on April 18.

He was promoted to colonel that summer and appointed Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff for Air Plans to help with strategic air planning on a global scale. In addition to the Doolittle air raid, he was involved in air plans for

Operation Overlord (later known as D-Day Invasion). His work at the Pentagon led to his participation in the Quadrant Conference in Quebec in August of 1943 with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King where the D-Day invasion of Europe was planned and agreed upon by the Allies.

Several months later in November, he was a planner and attendee at the Sextant Conference in Cairo with Roosevelt, Churchill, and Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek which outlined the Allied position against the Empire of Japan during World War II and made decisions about post-war Asia. The Conference agenda was to formulate a strategy to counterattack the Empire of Japan, make arrangements for the post-war international situation and coordinate the counter-attack on Burma and the aid to China. For this service, he was awarded a Legion of Merit in December. The citation for the award read in part, “His keen appreciation of strategical requirements and his knowledge of Army Air Forces’ capabilities and tactical developments contributed materially to the decisions reached by the Combined and Joint Chiefs of Staff.”

In January 1944, he was assigned to active duty in New Delhi as the air plans chief for the China-Burma-India Theater. From there he was promoted to assistant chief of staff for plans for the combined Chinese-American air and ground forces in the theater. In addition to the Legion of Merit, he was awarded several Oak Leaf Clusters, a Bronze Star, and the Air Medal of the U.S. Armed Services, as well as the Cravat Order of the Precious Bronze Tripod by the Chinese government.

When World War II ended in August 1945, Colonel Williamson, representing the United States, and Major General Pan Kwa-Kuo, representing China, were observers at Hong Kong on September 9, 1945, when all Japanese Armed Forces in the area surrendered to British Rear Admiral Harcourt, the commander of the Allied Forces in that theater.

Home Again

Adrian gave up a promising military career and promotion to brigadier general so he could return to his life and law practice in Monticello after he was honorably discharged from the armed service on April 8, 1946.

As his daughter Ann remembered many years later, “He enjoyed the challenge of his law practice, his various intellectual pursuits, and his hobbies. He put as much energy into each endeavor as a civilian as he did with the military, but he preferred civilian freedom to pursue those interests and felt it no great sacrifice to return to his law practice after the war. His greatest love was Home and all that represented.”

A Return to the Law after the War

Back home in Monticello, Adrian once again proved himself to be a careful and thorough attorney. As his nephew Lamar wrote in a 2008 memoir, Adrian’s “Calvinist work ethic often took the shape of a briefcase carried home every night in the week except Saturday and Sunday. For him, Saturday night belonged to the family and Sunday night to the Lord.”

His fellow citizens in southeast Arkansas saw Adrian not only as scrupulously honest but also as a reliable civil lawyer they could turn to for help with titles, wills, and estates. As a result, he became widely known for his expertise in probate law. According to Elizabeth Wells Chandler, a secretary with the law firm in the years following the war, “His wills just couldn’t be broken. Some people tried it, but they never got anywhere.”

Evidence of this came in 1948 when he was asked to serve as the Chairman of the Arkansas Bar Association and Arkansas Supreme Court Committee to draft Arkansas’s modern (and current) Probate Code. It was he alone who originated and drafted the statute allowing adoption by reference of fiduciary powers. He and Prof. Robert R. Wright were two of the members of the Amici Curiae brief writers in Robins v. Hammons , 1 which was

one of the early cases interpreting the “new” Probate Code of Arkansas. In Sims v. Schavey , 2 his portion of a presentation in 1957 of how to interpret the Probate Code 3 was cited as a “source” by the Arkansas Supreme Court in the Probate Code. He was also cited as a “source” of interpretation of the Probate Code in Huff v. Bruce 4 Much of the Arkansas Probate Code he and the committee produced was copied in large measure by many other states and continues in use today in Arkansas.

In 1969 the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws and the American Bar Association published and proposed the creation of the Uniform Probate Code. Prof. Robert Wright was one of the Co-Chairman and Adrian Williamson was one of 15 members of the American Bar Association’s Advisory Committee to the Special Committee Uniform Probate Code. These two men were the only two Arkansans out of the 67 lawyers who helped craft the Uniform Probate Code. He also served as Monticello’s city attorney for more than two decades and was a trusted counselor to many corporate entities in the area who were clients of the firm.

Beginning in 1936, he joined the board of Union Bank and Trust Company of Monticello as a director and later served as chairman from 1957 until he retired from practice in 1972. He was also an active member of the Monticello Rotary Club and served two terms as president.

As a strong supporter of Arkansas A&M College (now the University of Arkansas at Monticello), he also served as legal advisor to the college. The Arkansas Bar Association honored him with its 1960 Lawyer-Citizen Award.

A Faith Woven Through It All

Undergirding Adrian’s professional and civic life were his Christian faith, his service to his beloved church, and his personal relationship with God. A lifelong member of the First Presbyterian Church of Monticello, he served variously as deacon, elder, Sunday School teacher,

and superintendent throughout his adulthood.

Among his many contributions to both his home congregation and the larger church was his work in the 1960s as a member of the Mountain Retreat Association board of directors, helping oversee the operation of the denomination’s conference center in Montreat, North Carolina.

According to nephew Lamar, the inclusiveness of Adrian’s faith shone in his warm human relationships with people of other faiths in Arkansas and throughout the world. This also extended to people of color. In the late 1960s and early 70s, one of his great disappointments was his inability to convince his fellow session members to reach out to African American Presbyterians and invite the choir of Holmes Chapel in Monticello to sing at First Presbyterian.

A Legacy of Service

After his retirement from the law firm in 1972, he spent the last years of his life with his wife, Catherine, until her death in 1979.

Adrian Williamson, Sr., died in 1982 at age 90 while living at Presbyterian Village in Little Rock. He left behind a legacy of service that lives on more than 40 years later through family, friends, and clients who knew and loved him during his remarkable walk through life as “just a small town Arkansas lawyer.”

Endnotes:

1. 307 S.W. 857, 228 Ark. 329 (1957).

2. 351 S.W.2d 145, 234 Ark. 166 (Ark. 1966).

3. 12 Ark. L. Rev. 38, 50. 4. 549 S.W.2d 282, 261 Ark 498 (Ark. 1977). ■

A Quarter Century of Caring: ARJLAP and the Evolving Needs of Arkansas Lawyers

By Laura Mack Gilson and Jennifer Donaldson

As we approach the 25th anniversary of the Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program (ARJLAP), the changing mental health needs among judges and lawyers through ARJLAP’s dedicated and specialized mental health program for our profession helps chart our path forward.

The Arkansas Supreme Court created ARJLAP in 2000 to help address behavioral health and substance abuse affecting Arkansas judges and lawyers. All 50 states, including Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, have adopted a similar JLAP program.

Prior to ARJLAP, mental health issues and addiction robbed our profession of some of the best—judges and lawyers who were tops in our field but too ashamed or uninformed about mental health to know where to turn. They withered before us or died in the shadows, leaving their families and colleagues with the pain of the inexplicable loss. As research into neuroscience and genetics began to develop in the late 20th century, insight into mental health increased substantially. ARJLAP’s formation coincided with those medical advancements to bring that knowledge and support to judges and lawyers.

From 2000 to 2017, ARJLAP’s primary focus was individual assistance, supported by expanding educational outreach to the legal community and developing peer support networks. ARJLAP records show contact with attorneys reached in the thousands, and all these efforts were driven by a small team that consisted of an executive director, a staff counselor, and a secretary.

In 2017, the National Task Force on Lawyer Well Being published a seminal report1 that laid bare hard truths about the practice of law that those of us in the trenches know all too well: more than 1/3 of lawyers have a problem with alcohol and substance abuse, another 1/3 face depression, and another 1/5 struggle with anxiety and stress—all to a degree that interferes with the successful practice of law. A final sobering statistic from the report: lawyers rank No. 8 in the top 10 professions for suicide. That’s not business as usual. Those statistics reflect the pressures of the profession and the nature of those of us drawn to it.

After the 2017 report, JLAPs across the country, including ARJLAP, began to focus on preventing, rather than just treating, these behavioral issues to break the dismal statistical trend for lawyers. The prevention movement sprung hope and “wellness,” so it seems, eternally. Fidget toys, sensory stickers, aromatherapy,

breathing buddies, and (no doubt) some snake oil flooded the movement. And while some of these preventative therapies seem dubious to baby boomers, most are sound and scientifically based treatments for a variety of mental health issues. These latest gadgets are meant to supplement, not replace, other tried and true wellness practices such as social interaction, a healthy diet, and tennis, anyone?

In 2018, ARJLAP received more new clients than in any previous year, in part because of increased educational presentations in response to the 2017 report. In fact, self-referred clients told ARJLAP they learned of ARJLAP’s services through these educational presentations. ARJLAP’s recorded number of contacts that year also reflected an expansion beyond central Arkansas, and additional growth from the law school student population.

In 2020, when lockdowns and social restrictions prevented inperson services, ARJLAP quickly transitioned to providing clinical services through videoconferencing technology. Telehealth proved to be more convenient for some clients and also enabled ARJLAP to schedule more client sessions.

ARJLAP’s clientele has also changed since the program was first created in 2000. In the formative years, attorneys assumed any association with ARJLAP was due to a referral by the Office on

Laua Mack Gilson is General Counsel for the Arkansas Public Employees' Retirement System and Chair of the ARJLAP Committee.

Jennifer Donaldson is the Executive Director of the ARJLAP.

Professional Conduct when the attorney’s license was in jeopardy. Often, that referral was due to an addiction to drugs (legal or not) or alcohol. While ARJLAP continues to serve clients with substance use concerns, the vast majority of clients self-refer to ARJLAP for help and directions with depression, anxiety, or life or work situations that are affecting their ability to practice law. This is the precise goal of ARJLAP—to encourage and enable judges and lawyers to reach out before a small problem becomes big, or before an acute problem becomes chronic.

Since 2020, ARJLAP has tallied more than 3,000 office contacts. In addition, 875 attorneys and law students have attended ARJLAP in-person events. Over 7,500 judges and attorneys have attended ARJLAP’s online webinars for CLE or wellness education. Those significant numbers show that in a state with roughly 6800 attorneys,2 we are paying attention to mental health and wellbeing and understand that ARJLAP helps us maintain our trust with the community we serve.

But why should the legal profession have a special program of mental health and wellness to individually and collectively care for its own? As leaders who often solve problems for the community, our ability to give sound advice requires soundness of mind as well. We wisely serve the interests of the state by building mental resilience and displaying the temperament needed to practice law. We are role models whose clients often face the same or similar mental health issues that predicate their introduction to the court system. As is often the case, but for the (untreated) mental illness or addiction, attorneys or their clients would not have made detrimentally fateful decisions. Who better to seek and maintain mental health than those who serve the public and dispense justice? Consequently, ARJLAP is more than about saving our own endangered law practice; in the process of doing so, we serve others.

Lawyers must function at a high level, but often perform our jobs autonomously. That may allow us to ignore or deny dangerous mental health conditions that are treatable and often curable. To our way of thinking, even if we have reached a point of unbearable discomfort, getting help for

our mental health translates as defeat— anathema in the legal world. ARJLAP counters that thinking with education and counseling. Building strong mental health is a triumph, not a defeat. ARJLAP by design caters to attorneys by providing confidential counseling that recognizes these unique professional characteristics. Through ARJLAP, attorneys can also avoid the huntand-peck method in seeking help, which means getting back to peak performance sooner.

Like other national JLAP programs, ARJLAP has evolved throughout the years to address the changing landscape of mental health and develop a comprehensive program of education, peer support, counseling, and referral. Events unforeseen in 2000 that affected mental health, such as the opioid crisis or the covid epidemic, continually require ARJLAP to adapt.

As we celebrate the successes of 25 years, ARJLAP is seeing remarkable progress in a strengthened judiciary and bar. With tremendous support from the Arkansas Supreme Court and the hard work of judges and attorneys willing to be role models in our courthouses and communities, ARJLAP continues its work through:

• Statewide counseling services (free of charge up to designated grant amount)

• Confidential contact for inquiries

• Lawyer-to-lawyer peer support

• CLE webinars

• Year-round mental health and wellness education

• In-house voluntary and mandatory alcohol and drug use monitoring

• Educational programs for U of A and UALR law school students

• Demonstrations of wellness techniques and products

To contact ARJLAP for confidential assistance or to volunteer call 501-907-2529 or email confidential@arjlap.org.

Endnotes:

1. The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change, August 2017.

2. American Bar Association, updated 2024; https://www.americanbar.org/news/ profile-legal-profession.

Results from the 2024 Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program Mental Health Survey

By Catherine Crisp, PhD, MSW & Jennifer Donaldson, LCSW

Overview

In 2016, the American Bar Association, in collaboration with the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, conducted a multi-state study to examine mental health, well-being, and the prevalence of substance use among judges and lawyers. Led by Patrick Krill,1 an attorney and researcher, this study was one of the first studies to examine this issue. In 2023, Jennifer Donaldson, ARJLAP Executive Director, approached Dr. Catherine Crisp, an Associate Professor at the UA Little Rock School of Social Work, about conducting a study of judges, lawyers, and law students that would replicate some of the study conducted by Krill and explore other questions of interest to ARJLAP. Dr. Crisp had conducted meditation workshops for ARJLAP and was supportive of the challenges that judges and lawyers face. This article presents some of the study’s findings.

The survey included the three measures that Krill used: the AUDIT,2 a 10-item instrument developed to screen for unhealthy alcohol use; the DASS-21,3 a 21-item measure to assess depression, anxiety, and stress in three subscales, each of which is reported separately; and the DAST-10,4 a 10-item measure to assess drug use, not including alcohol and tobacco use, in the past 12 months. With each of the measures, higher scores indicate more severe problems. Demographic questions and two questions about contact with ARJLAP were also included in the survey packet.

continuted on next page

2024 ARJLAP Mental Health Survey (cont.)

1,547 lawyers responded to the survey

In April 2024, the Office of Professional Programs sent an initial email to all licensed attorneys in Arkansas informing them about the study and asking them to complete the survey instrument. This was followed by reminder emails every two weeks until June 9, 2024. Lawyers who agreed to the informed consent and submitted the survey were eligible to receive a link to an online training that was worth one CLE credit. 1,547 lawyers responded to the survey, and 1,149 (76%) answered all 53 items in the summed scales, while 1,425 (94.37%) answered all the demographic questions. For each of the measures, only those who answered all questions in the scale or subscale were included in the analysis.

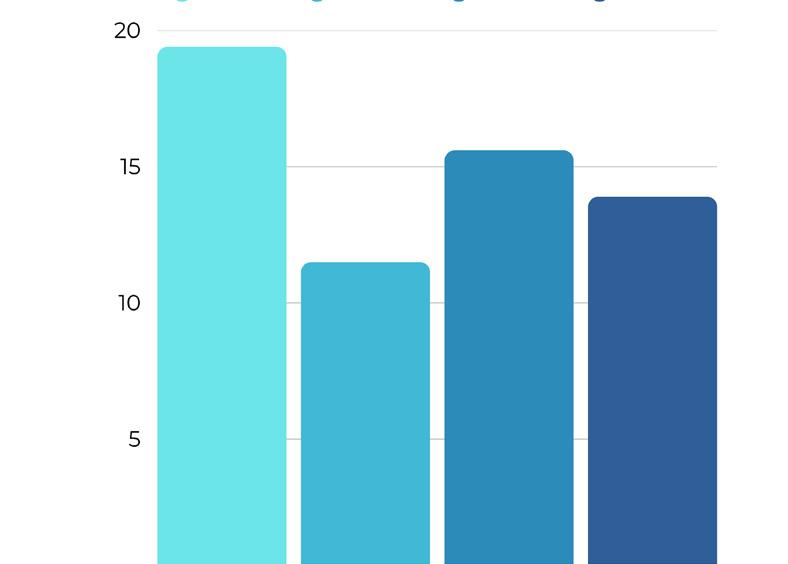

Results

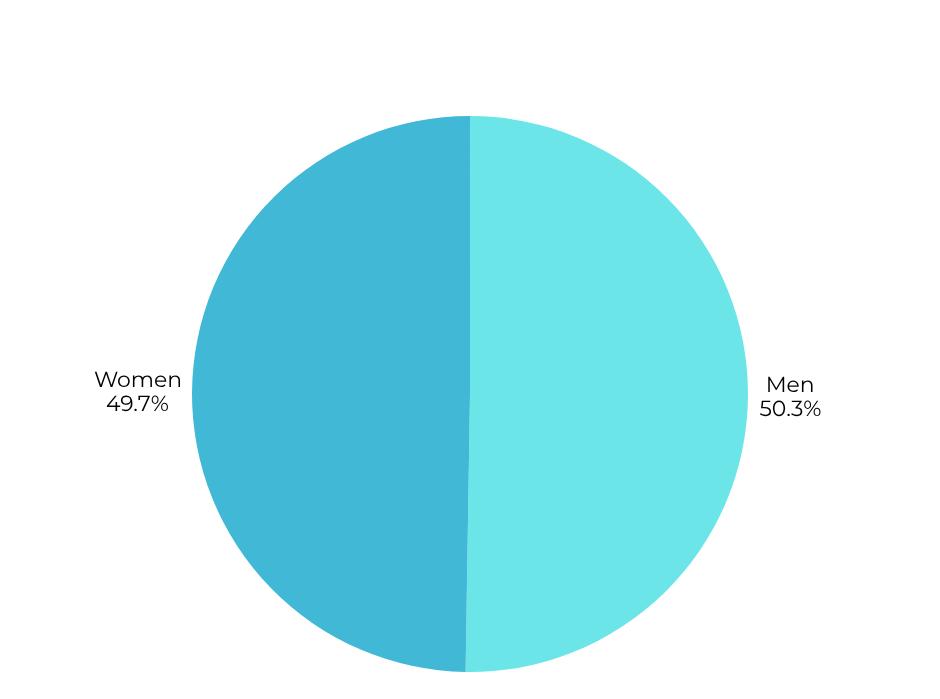

Men (49.7%) and women (49.2%) responded in almost equal percentages, while those aged 41–50 (24.3%) and 51–60 (24.3%) were equally likely to respond and more likely to respond than other age groups. The sample was largely Caucasian/ White (89.4%). Most respondents identified as being married (69%) and as having children (68.8%).

Audit

Of 1,211 lawyers, 19.4% of the respondents could be classified as having problematic alcohol use. This is slightly lower than Krill’s finding that 20.6% of lawyers had problematic alcohol use. Men had significantly higher scores and higher rates of problematic use than women. Lawyers aged 31–50 had the highest mean score of all age groups.

DASS-21

Responses to all three measures indicated

more severe challenges than Krill found. 11.5% of 1,425 lawyers could be classified as experiencing severe or extremely severe depression compared to 8.4% in Krill’s study. 15.6% of 1,433 lawyers could be classified as experiencing severe or extremely severe anxiety compared to 5.6% in Krill’s study. 13.9% of 1,429 lawyers could be classified as experiencing severe or extremely severe stress compared to 5.7% in Krill’s study. Women had significantly higher scores than men on the anxiety and stress subscales but not on the depression subscale. Lawyers aged 30 and younger had the highest mean score of all age groups on all three subscales.

DAST-10

Of 1,357 lawyers, 1.1% could be classified as having severe or extremely severe drug use, a finding lower than Krill’s finding of 3.1% who experienced severe or extremely severe drug use. There were no significant differences in men’s and women’s scores. Lawyers aged 31–40 had the highest mean score of all age groups.

Contact with ARJLAP

This finding may be the most telling: lawyers who indicated any type of engagement with ARJLAP had significantly higher scores on all measures of mental health and substance use than those who did not report contact with ARJLAP. An argument could be made that ARJLAP is thus attracting those with the greatest need: those with the most severe substance use and mental health challenges.

Summary

The findings presented here underscore the crucial need for ARJLAP’s services by revealing significant well-being challenges among Arkansas lawyers. With 19.4% of

lawyers reporting problematic alcohol use, 11.5% experiencing severe depression, 15.6% severe anxiety, and 13.9% severe stress, lawyers in Arkansas experience more challenges than lawyers represented in a well-known national study. While these results may be disconcerting, the finding that those who engaged with ARJLAP had significantly higher scores on all measures of mental health and substance use confirms that ARJLAP effectively reaches those most in need of support. This study also affirms the unique and vital role that ARJLAP has in Arkansas: to serve impaired members of the legal community and protect the public at large. Just as it has for almost 25 years, ARJLAP will continue to evolve to address the needs of lawyers and law students.

Endnotes

1. P.R. Krill, R. Johnson, & L. Albert, The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys, 10 J. Addiction Med. 46 (2016).

2. B. Saunders et al., Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II, 88 Addiction 791 (1993).

3. J.R. Crawford & J.D. Henry, The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Normative Data and Latent Structure in a Large Non-Clinical Sample, 42 Brit. J. Clinical Psychol. 111 (2003), https://doi. org/10.1348/014466503321903544.

4. H.A. Skinner, The Drug Abuse Screening Test, 7 Addictive Behav. 363 (1982), https://doi.org/10.1016/03064603(82)90005-3.

All Rise for Attorney Well-Being

By Arkansas Supreme Court Chief Justice Karen R. Baker

We lawyers pretend that our profession is immune from the harsh reality that struggles with mental health and substance abuse impact us all. But the truth is, we are humans first and attorneys second. In my nearly 40 years in the practice of law, I have witnessed firsthand the debilitating impact that stress and pressure can have on the legal community. And, I have lost friends that might have been saved. However, times have changed for the better and we are fortunate to have access to a resource unavailable to our predecessors and no longer have to suffer in silence or in shame.

Amendment 28 to the Arkansas Constitution vests the Arkansas Supreme Court with the duty and authority to make rules regulating the practice of law and the professional conduct of attorneys at law.1 The purpose of the amendment is to protect the public and to maintain the integrity of the courts and the honor of the profession.2 Part of this responsibility involves the establishment and maintenance of programs like the Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program (“JLAP”) that directly aim to provide services to members of the legal community and to protect the public at large. When JLAP was created in the early 2000s, it both validated and rose to meet the needs of attorneys plagued by issues that have persisted in our profession since the beginning. For over two decades, JLAP has worked tirelessly to meet the needs of the Arkansas bench and bar, and it is my honor to be the court’s liaison to JLAP, and it has been my honor for many years. Through my involvement with JLAP, I have heard directly from countless attorneys that JLAP has changed the trajectory of their lives.

Not long ago, in furtherance of JLAP’s mission to promote attorney wellness, the Committee has presented the court with a recommendation to amend our Continuing Legal Education (“CLE”) requirements to include a one-hour lawyer “well-being” course. This recommendation stems from a published report from National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change.3 Specifically, the report explains,

To be a good lawyer, one has to be a healthy lawyer. Sadly, our profession is falling short when it comes to well-being. [Studies] reveal that too many lawyers and

law students experience chronic stress and high rates of depression and substance use. These findings are incompatible with a sustainable legal profession, and they raise troubling implications for many lawyers’ basic competence. This research suggests that the current state of lawyers’ health cannot support a profession dedicated to client service and dependent on the public trust. The legal profession is already struggling. Our profession confronts a dwindling market share as the public turns to more accessible, affordable alternative legal service providers. We are at a crossroads. To maintain public confidence in the profession, to meet the need for innovation in how we deliver legal services, to increase access to justice, and to reduce the level of toxicity that has allowed mental health and substance use disorders to fester among our colleagues, we have to act now. Change will require a wide-eyed and candid assessment of our members’ state of being, accompanied by courageous commitment to reenvisioning what it means to live the life of a lawyer.4

In response to the National Report, the court authorized the formation of an Arkansas Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being. The Arkansas Task Force later issued its own report and recommended that our CLE requirements be amended to require a one-hour “well-being” course. This proposal garnered the unanimous support of the JLAP Committee. For the next several years, JLAP was willing and able to expand its already-established clinical services

Arkansas Supreme Court Chief Justice Karen R. Baker is the Co-Liason for the Court on the ARJLAP Committee

and activities by researching, developing, and implementing a wellbeing program. As part of this program, JLAP has hosted well-being and mental health first aid training sessions for JLAP volunteers; organized confidential group support sessions; presented well-being topics at numerous non-JLAP conferences attended by Arkansas attorneys, judges, and law students; and attended multiple outreach events at both Arkansas law schools. Additionally, JLAP has offered well-being CLE programming covering topics ranging from stress preparedness, addiction, trauma, boundary development, and the power of positive thinking. The existence of such a comprehensive well-being program would not be possible without the unwavering dedication of those who are devoted to making JLAP a success.

Many of you have reaped the benefits of JLAP’s services and can attest to the value of setting aside time to work toward a healthier version of yourself. For those of you who have not, I would highly encourage you to do so. As we all know, it is a very commonly held belief amongst attorneys that we cannot possibly fit another task into our already busy schedules. However, it is my hope that this well-being CLE programming will become a requirement for each and every licensed attorney in Arkansas. Our mental health and well-being are too high a price to wager. You, your family, your colleagues, your clients and our profession will be better for it.

Endnotes:

1. See Ark. Const. amend. 28.

2. In re Shepard, 2015 Ark. 93, at 5–6, 457 S.W.3d 280, 284.

3. Nat’l Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, The Path to Lawyer

Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change, American Bar Association (2017), available at https://www. americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/news/2021/ ThePathToLawyerWellBeingReportRevFINAL.pdf.

4. Nat’l Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, supra note 3, at 2.

SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS PER CURIAM

In re Amendments to the Rules for Minimum Continuing Legal Education (Rule 3 and 5) and Rules of the Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program (Rule 1), 2025 Ark. 160

The Arkansas Supreme Court issued proposed rule changes to add a mandatory one hour of "well being", in the present required twelve hours of yearly CLE. Written comments should be sent to the Clerk of the Courts through December 31, 2025.

https://opinions.arcourts.gov/ark/supremecourt/ en/523862/1/document.do

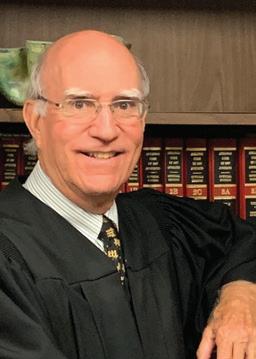

The Origin of Arkansas's JLAP: A View from the Bench

By Justice Robert L. Brown, Retired

When I first was sworn in as a justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1991, there was no program in place to help or assist lawyers, law students, or judges who suffered from depression or debilitating illness brought on by stress or anxiety associated with the study or practice of law. Most, if not all, of the states in the U.S. had such a program, but Arkansas did not, though several attorneys and Chief Justice Jack Holt in particular had voiced the need for a substance abuse counseling program since the mid-90s. Several years later in 2000, a per curiam order was issued by our Supreme Court, creating Rules and Regulations for a Lawyers Assistance Program (LAP) to provide physical and mental assistance to those in need of help. Thus, a LAP for attorneys came into existence, but a program for law students and judges still did not exist.

Because of my keen interest in the issue, I became liaison for the Arkansas Supreme Court to develop a Lawyers Assistance Program. My counterpart in the Arkansas Administrative Office of the Courts was Chris Thomas, who had a similar interest, but he was way ahead of me. He used a Tennessee Supreme Court per curiam that created that state’s Lawyer Assistance Program as a template and tailored it to fit Arkansas. As I recall, the drafting did not entail much more than changing “Tennessee” to “Arkansas.” I doubt that Tennessee ever knew it provided the blueprint for the Arkansas Supreme Court per curiam order creating a LAP program.

At least 10 years before the issue reached the Arkansas Supreme Court, several persistent lawyers formed committees within both the Pulaski County Bar Association and the Arkansas Bar Association to advocate for an Arkansas LAP. The bar associations eventually joined forces to advocate for the approval of the per curiam order by the Arkansas Supreme Court.

I recall that there were a couple of members of the Court who had reservations about the new program. They raised the questions: “Was this the best use of the Court’s money?” and, secondly, “Was the LAP program just another do-good program without much substance?”

The Rules and Regulations for the Arkansas LAP, however, were ultimately approved by the Supreme Court effective December 7, 2000, for counseling and mentoring of attorneys who sought assistance or who were ordered to undergo evaluation under LAP. Embraced within the rules was a $15 annual fee collected from every lawyer to fund the program.

The Supreme Court appointed a LAP Committee to administer the LAP. In addition, the Court hired a director to train and work with LAP volunteers. A leader in the early development of the LAP has been Dr. Sarah Cearley, a lawyer, licensed social worker, and one of the first executive directors of JLAP. Her law review article

in 2014 for the University of Arkansas at Little Rock provides a more comprehensive history of the JLAP (née LAP) effort from its inception.1 Dr. Cearley helped guide JLAP to meet the goals formalized in the December 7, 2000, per curiam order.

In 2011, law students and judges were covered. I remember learning of a circuit judge, who was under considerable stress as a judge, committing suicide. This case, and I’m certain other cases with similarly fatal or disastrous outcomes, led to renaming the program JLAP, for a Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program.

When JLAP originated, counseling for substance abuse was by far the number one medical need for lawyers, with 76% involving alcohol abuse and 9% concerning prescription drugs. Other categories of programs where JLAP counseling was in demand were marriage and family problems, financial and career challenges, and issues surrounding aging. Now, a majority of attorneys seek JLAP assistance for depression and anxiety-related disorders.

The largest percentage of referrals to the JLAP program because of mental impairment in 2012 were lawyers who had a solo practice—45%. The second largest conglomerate of referrals to JLAP was 21% of career referrals representing lawyers or associates working in law firms, who were not satisfied with their careers. Moreover, statistics tell the legal profession that law students enter law school with a 10% level of depression, which equates to the level of depression for the general public. However, by the end of the threeyear program for law school, some 40% of students had a debilitating mental disorder brought on by stress and anxiety associated with the study of law. Other comparisons with the general public are witnessed in a Johns Hopkins study that revealed that lawyers are 3.6 times more likely to suffer from clinical depression than other professions.

Endnote:

1. See Sarah Cearley, Lawyer Assistance Program Bridging the Gap, 36 U. Ark. Little Rock L. Rev. 453 (2014).

Justice Robert L. Brown served as an Associate Justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court from 1991 to 2012 and currently is Of Counsel at Friday, Eldredge & Clark LLP.

Preferred IOLTA Banks support justice for all Interest earned on IOLTA accounts funds legal aid Learn more at arkansasjustice.org/IOLTA.

By Bill Putman

Well-Being in the Arkansas Legal Community

The Arkansas legal community’s interest in lawyer wellbeing is a relatively recent phenomenon.1 When I graduated from law school in 1991, no one was talking about lawyer well-being. Arkansas JLAP did not come into existence for another nine years, law students were not eligible for JLAP services for another 10 years after that, and it would take a full quarter century before the first national survey of lawyer well-being in the United States would be published. Issues like depression and alcoholism were seldom acknowledged, much less discussed, due in large part to the risk of stigma and fear of professional repercussions. As a profession we have made some progress, but there is much, much more work to be done.

Research on lawyer well-being is also relatively new, and for many years it was pretty sparse. One of the first such articles was published in 1986 by Dr. Andrew Benjamin and his colleagues.2 In a longitudinal study of law students at different stages in their education, the authors found that the students’ mental health declined significantly during their three years in law school. While 8 to 9% of the students showed signs of depression when they entered law school—the same level found among their non-law student peers—40% did by their third year. Dr. Benjamin followed some of the students for two years after graduation, and he found that their mental health did not improve during that time.

In the early 1990s, further research indicated that lawyers might be experiencing mental health and substance abuse issues at a rate significantly higher than the adult population overall. A 1990 study by Dr. Benjamin found that 18% of lawyers surveyed were “problem drinkers” compared to 10% of American adults.3 19% of these lawyers reported statistically significant levels of depression, while rates of depression in studies of Western adults ranged from 3% to 9%. Another 1990 study published in the Journal of Occupational Medicine assessed the prevalence of depression in 104 occupations and found the highest rate among lawyers, who suffered from depression at a rate 3.6 times greater than employed persons generally.4 The 1993 book Listening to Prozac by Dr. Peter Kramer, which spent four months on the New York Times bestsellers list, served as a catalyst for a national discussion on depression and mental health, but by and large the legal profession appeared not to participate in that discussion.5

Fortunately, the landscape began to change for the better in 2016 when the results of the first national study of lawyer well-being were published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine. 6

This research, spearheaded by Patrick Krill and sponsored by the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation and the American Bar Association Committee on Lawyer Assistance Programs, provided strong empirical support for the growing belief that lawyers were experiencing well-being issues at astonishingly high rates. Among other things, the ABA study found that rates of depression, anxiety, and stress among lawyers were 28%, 19%, and 23% respectively. 20.6% of lawyers surveyed screened positive for alcohol abuse and dependence, with 36.4% screening positive on the dimensions of frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption. These figures are all well above the levels reported in the general population. For example, at the time data for the ABA study was being collected the National Institute of Health reported that the rate of depression among adults in the United States was 7.3%.7 At the same time, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration assessed the rate of alcoholism among adults at 5.9%.

The alarming results of this ABA study led to the formation of a National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being in August 2016. A year later, the Task Force published a report titled The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change 8 Key objectives of that report were to educate the legal community on the nature and extent of its well-being issues and outline incremental steps stakeholders could take to facilitate positive change.

Bill Putman is a solo practitioner in Fayetteville where he represents clients in civil litigation and appeals in state and federal courts.

One of the ABA report’s specific recommendations was for states to form their own well-being committees. The Arkansas legal community took this recommendation to heart. The Arkansas Supreme Court authorized Chief Justice John Dan Kemp to form the Arkansas Supreme Court Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, which issued its own report in October 2019.9 Echoing the national report’s emphasis on the central role of state lawyer assistance programs in facilitating improvements in lawyer wellbeing, the Arkansas report noted that Arkansas JLAP is “understaffed and underresourced to meet current and increasing demand for JLAP services” and emphasized the importance of securing “stable and adequate funding” in order to adequately serve the needs of our state’s lawyers and judges.

Given all the positive things that followed in the wake of the ABA report, lawyers had good reason to be optimistic that our profession would start making meaningful progress toward improved wellbeing in 2020. But then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, sending shock waves through all sectors of the legal profession. Paradoxically, the pandemic greatly increased the need for well-being education and services at a time when COVID restrictions made meeting those needs even more challenging.

In 2019 American Legal Media began conducting annual surveys of mental health in the legal profession. The results published in 2020, which were based on data collected in 2019, showed 31.2% of lawyers who responded to the survey were suffering from depression while 64% were experiencing anxiety. In the first survey conducted during the pandemic in 2021, the rate of depression increased to 37% while the rate of anxiety rose to 71%. Data from 2022 through 2024 showed little to no change in those numbers. One result that has changed, however, is the percentage of lawyers who believe mental health issues have reached a crisis level. Just over 41% responded affirmatively to that question on the survey in 2020 and 2021. The percentage of affirmative responses increased to 44% in 2022, then to just over 49% in 2023 and 2024.

While it is difficult to compare numbers from different surveys using different methodologies, compelling evidence shows that the disturbingly high levels of wellbeing issues found in the 2017 ABA study have gotten worse in the past decade, not better. And while the COVID pandemic undoubtedly exacerbated the prevalence and impact of those issues, the elevated levels of post-pandemic depression, anxiety, and substance abuse should be concerning to everyone in our profession. Also concerning is what some in our community see as a waning of support for well-being initiatives at a time when the evidence strongly suggests that we should be redoubling our efforts to implement the recommendations set forth in the ABA and Arkansas task force recommendations.

Arkansas lawyers, judges, and law students are truly fortunate in having the services and resources available through Arkansas JLAP. We live in one of the few states that offers free, confidential counseling services to members of the legal community, either through JLAP staff or contract therapists located throughout Arkansas. In recent years Arkansas JLAP has taken significant steps to increase awareness of the nature and extent of mental health and substance abuse issues our profession faces, provide information concerning the causes of those issues, and educate the legal community on the steps we can take to address them.

Arkansas JLAP offers regular online CLE presentations on a variety of well-being subjects, many of which are offered free of charge and some of which are available at low cost on demand.

Both the ABA and Arkansas well-being task forces emphasized the importance of properly staffed and adequately funded lawyer assistance programs. For a quarter of a century Arkansas JLAP has worked to address the needs of our legal profession, and as a result Arkansas can proudly say it has one of the most respected and effective lawyer assistance programs in the country. I encourage each of you to consider supporting Arkansas JLAP, financially and as a volunteer, and to demonstrate your support for the program. The well-being of the Arkansas legal community depends on all of us doing our part.

Endnotes:

1. As used herein, “well-being” is an umbrella term encompassing issues relating to or arising from depression, anxiety, stress, substance abuse, aging, and other factors that may affect a lawyer’s ability to practice law and enjoy a good quality of life.

2. Andrew Benjamin et al., The Role of Legal Education in Producing Psychological Distress Among Law Students and Lawyers, 11 Law & Soc. Inquiry 225 (1986).

3. Andrew Benjamin et al., The Prevalence of Depression, Alcohol Abuse, and Cocaine Abuse Among United States Lawyers, 13 Int’l J.L. & Psychiatry 233 (1990).

4. William W. Eaton et al., Occupations and the Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder, 32 J. Of Occup. Med. 1079 (1990).

5. Peter D. Kramer, Listening to Prozac: A Psychiatrist Explores Antidepressant Drugs and the Remaking of the Self (Viking 1993).

6. Patrick R. Krill et al., The Prevalence of Substance Abuse and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Lawyers, 10 J. Addict. Med. 46 (2016). For convenience, this report will be cited herein as the “ABA report.”

7. Renee D. Goodwin et al., Trends in U.S. Depression Prevalence From 2015 to 2020: The Widening Treatment Gap, 63 Am. J. Prev. Med. 726 (2022).

8. National Task Force on Lawyer WellBeing, The Path to Lawyer Well-being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change (Am. Bar Ass’n 2017), available at https:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/ administrative/news/2021/ThePathToLawyerWellBeingReportRevFINAL.pdf.

9. Arkansas Supreme Court Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, Report of the Arkansas Supreme Court Task Force on Lawyer WellBeing (Ark. Judiciary 2017), available at https://arcourts.gov/sites/default/files/taskforce-on-lawyer-well-being-report.pdf.

At Public Notice Agency, we have one important mission: place all legal notices for firms like yours, saving you money and time while ensuring accuracy. Our team uses innovative technology to place your notices in qualified newspapers. We confirm scheduled publication, manage accounting, and provide you with proofs along with one invoice.

EMAIL US! INFO@PUBLICNOTICEAGENCY.COM OR BY PHONE (501) 823-9002

Why Wouldn't We Struggle?

By Caleb G. Conrad

On the first day of law school orientation, the faculty gravely informed us that law students and practicing attorneys face significantly increased risks of substance abuse and depression. A dry chuckle rippled through the E.J. Ball Courtroom. Yeah, right. Not us.

Eight months later, a large group of us were sleep-deprived and half-drunk at our favorite Dickson Street bar, casually discussing whose Adderall prescription might get us through finals week. I sipped my beer and thought about those statistics, wondering if I’d be Exhibit “A” in next year’s orientation.

The real question isn’t “ Why do lawyers struggle? ” It’s “ Why wouldn’t we struggle?”

The struggle starts day one of 1L year. We’re thrust into direct competition with our peers—each one seemingly smarter, more well-adjusted, and better dressed than we are—while trying to extract holdings from case law written before indoor plumbing was commonplace. At the same time, we’re attempting to convince everyone (mainly ourselves) that we belong and that majoring in political science wasn’t a catastrophic life choice. We navigate this labyrinth of cold calls, curved grades, and crippling self-doubt while piecing together an employable GPA and padding our résumés with clerkships and extracurriculars— credentials we hope will land us our dream job after graduation. Of course, we have no idea what that job actually is, and its definition shifts with the wind. One day we’re certain our calling is public interest law, the next we’re fantasizing about living lavishly as a powerful partner in a top global firm, and a month later we’re convinced we’re destined to be a hometown circuit judge, living out a John Grisham novel. These often unrealistic and self-imposed expectations breed bad habits and questionable coping mechanisms, and the open bar at every law school or law firm networking event is happy to nurture them. Why wouldn’t we struggle?