ISSUE 9—SEPTEMBER 2025

On Sept. 8, 1966, Star Trek premiered on televisions nationwide. The groundbreaking nature of this show appealed to millions of fans, and has continued to grow its avid following ever since. It combined a healthy dose of space exploration with a determination to explore humanity through the lens of science fiction.

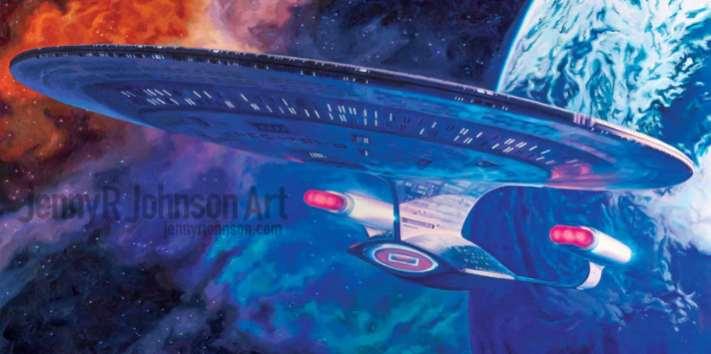

Star Trek isn’t just about the voyage into the stars, although the exploration of our galaxy is certainly a part of it. Discovering all those fascinating nebulae, planets, comets and other such stellar phenomena are just too scintillating to pass up.

Rather, Star Trek was as much, if not more, about the exploration of humanity. About our lives, our culture, our religion, our societal problems and how all of those differences could be melded together to create a more prosperous future for all of us.

This issue delves into many of the ways in which Star Trek spoke to us as fans. How it provided a hope for humanity to survive, to move on to new horizons, and to boldly explore the Final Frontier.

Mark Sickle Founder & Host Star Trek Family

We are truly interested in receiving feedback from our readers and fellow fans! Really love an article that appears in our magazine? Truly disagree with someone’s take on a topic? How are we doing? Do you have suggestions for features, articles, etc.? CONTACT US

Have you always wanted to write about your love for Star Trek? We are always looking for volunteer writers to join our team! Send us an email at the ‘Contact Us’ link at left!

** The Star Trek Family is a free, not

Like so many Star Trek fans that aren’t old enough to have enjoyed The Original Series on it’s first run, I was introduced to the magic of space exploration by my dad. He ruled the TV and, for the most part, our TV was tuned to what HE wanted to watch. I can’t recall the first time I watched James T. Kirk and crew, for it seems like they have always been a part of my life.

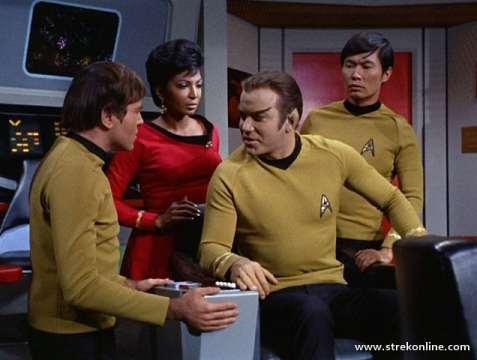

Watching these beloved characters snared my interest and kept me enthralled. With the innocence of youth, and no knowledge of bigotry, racism, sexism or xenophobia, I genuinely had no clue how truly groundbreaking TOS was. It wasn’t until much later that I was able to grasp how incredibly significant to social activism Star Trek was. Looking at the diversity of the Enterprise bridge crew through the lens of history brings the way Star Trek ushers humanity forward into focus.

Let’s start with Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu. When Star Trek aired in 1966, it was a mere 25 years since the Japanese bombed Pearl

Harbor. 25 years. That is the equivalent of the Y2K scare, the Holy Year, and the turn of the century for us. 25 years, and here is this handsome, brave, Japanese helmsman sitting on the bridge with a farm boy from Iowa. Nyota Uhura, communications and linguistic expert. For those of us that were not yet alive, let’s take a look at the history of that time period. Star Trek

aired before most women were allowed to have a credit card in their own name. This was also at the height of the civil rights movement, two years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination based on race in public spaces, and two years BEFORE the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the states to dismantle segregated schools. Yet, here is a classy, intelligent, resourceful, (and yes, beautiful) woman in charge of a vital function of the ship. Not just a woman, but a woman gifted with more melanin than the rest of the bridge crew. Uhura gave representation to a previously ignored demographic. Watching her handle herself with grace and hold her own against men was so empowering to so many girls.

Pavel Checkov came on the scene in 1967. Granted, he was added to be a heartthrob, but he was Russian. Examining the history as it pertains to Russia, this was during the thick of the Cold War. Post WWII, the United States and Russia had significant differences of opinions regarding

government and ideology, paving the way for hostilities and mistrust. I remember growing up that the favorite villains to cast in movies were Russians. Do you need a big, bad antagonist? Russia was the go to. And yet, here comes Checkov, integrating into the crew and being very proud to be Russian.

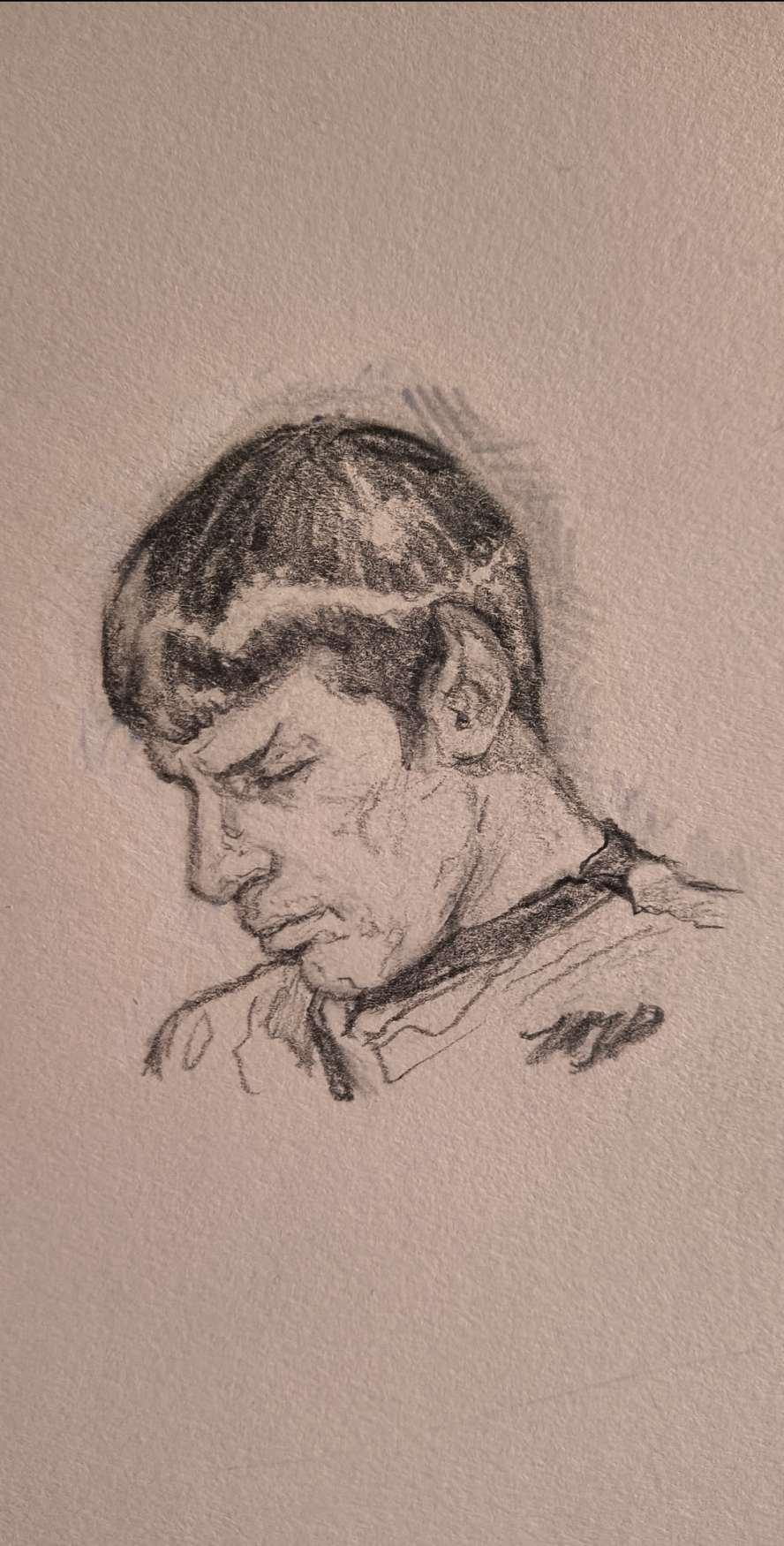

The last minority is Spock (Coincidentally my first love). Spock was almost the antithesis of humanity. Emotions were not used to make decisions, gut feel-

ings were not followed. There was no flying by the seat of his pants. Actions were made by logic and plotted out. The Vulcan culture was different. Customs, rituals and expectations were all foreign. Although he was subjected to some ridicule, (Bones, as if you didn’t know), mostly the crew was respectful and supportive of those differences.

Every aspect of Star Trek was designed to propel humanity forward. The diverse crew was literally chosen to make the audience rethink the bigotry that reflected the political climate of the time. The whole premise was to work together, rely on the strengths that lie in diversity. To explore other species, planets and cultures. The key word here is explore, not conquer. Star Trek took on real world topics from the times they were living in, and exposed them in a safe fictional way. “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”

highlighted how ridiculous and self-sabotaging it is to blindly hate someone because they don’t look like you. They were the first to show a woman of color in a position of equality, respect and authority and not as a maid, or worse. They tackled the first interracial kiss during a time when that was just not done. Most of the southern states wouldn’t air that episode. The crew of the Enterprise made us ponder moral dilemmas and made us question, well, everything.

Star Trek smashed the barriers of preconceived stereotypes and forced us to look at ourselves under a magnifying glass. It gave us a glimpse of a possible future, one I hope to be a part of.

JANERA TIELL MANNO :

Janera Tiell Manno has been a life-long Star Trek fan, loves her family, logic and bad puns. Very proud to be a part of the Trek community.

Part of how Star Trek addressed race was in its casting. The inclusion of Nichelle Nichols as Lieutenant Uhura, a Black woman serving as a high-ranking officer on the bridge of the Enterprise, was groundbreaking. Uhura was not only a visible symbol of diversity, but she was portrayed as competent, intelligent, and respected, a powerful counternarrative to the stereotypical roles Black actors were often relegated to at the time. Having other characters such as Sulu (Japanese), Chekov (Russian), Scotty (Scottish), McCoy (U.S. Southerner) and an alien Spock was groundbreaking for its time. So much so that several television stations during its run refused to air the series.

TOS approached racism allegorically in several episodes, with one of my favorites being Let That Be Your Last Battlefield.” In this episode, the Enterprise encounters two alien beings from the planet Cheron: Lokai and Bele. Both characters appear similar at

first glance, however, it is revealed that one is black on the left side of his face and white on the right, while the other is the reverse. The two harbor a deep hatred for one another, each viewing the other as inferior based on their physical appearance.

This exaggerated form of racism served and serves as an allegory for the irrationality of racism that plagues the planet to this day. By creating a conflict that viewers could see as absurd, the show highlighted how racial prejudice in the real world is equally baseless and destructive. The episode concluded tragically, as the

two characters return to a devastated Cheron, where the conflict has annihilated their civilization. Yet, they continue the fight as the lone survivors. The message was clear: Racism, if left unchecked, leads to mutual destruction.

This episode also highlighted a gradual change in how TOS approached the concept of war. The Cold War loomed large in the 1960s, shaping all political discourse. The fear of nuclear annihilation and the tension between the United States and the Soviet Union formed the backdrop of daily life. TOS frequently used its setting to comment on the futility

of war and the possibility of peaceful coexistence. However, the message was not consistent throughout the series.

Many fans today would consider that the message of war was relatively consistent over the show’s history. That is, war is bad, and should be avoided.

This was not always the case, however. Looking specifically at TOS, we see an evolution of thought.

In both “The City on the Edge of Forever” and “A Private Little War,” it was suggested that the Vietnam War was merely an unpleasant necessity on the way

to the future dramatized by TOS

But in “The Omega Glory” and “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” (broadcast in the period between March 1968 and January 1969) both are so thoroughly infused with the desperation of the period that they openly call for a radical change of historic course, including an end to the Vietnam War and to the culture war at home (referring to the Civil Rights Movement). Only this new course presumably would take us to the universe of the U.S.S. Enterprise. Though I did not quite understand all the social messages of the time as I was quite young, I was aware enough of the connections the show was making to some things occurring around me, such as in the episode “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” which highlighted and demonstrated the absurdity of amplifying racial and ethnic differences. After all, it was a storyline I was used to seeing on the evening news. I could also see in episodes like “The Mark of Gideon” the dangers of utter disregard for the environment. And the episode “A Private Little War” demonstrated how interference in a culture can esca-

late hostilities, such as what was happening among the Soviet Union, China and the United States in Vietnam. These things appeared obvious to me, even as a child. There was more to TOS than simply entertainment. As time went on, I trusted the show as a means of teaching me morality and life lessons, especially as they fit with the lessons my parents and family were teaching me.

Another episode that addressed these themes was “A Taste of Armageddon.” The crew discovers two planets, Eminiar VII and Vendikar, which have been at war for centuries. However, instead of physically destroying each other, the war is conducted via computer simulations. Citizens are killed in these simulations and then report to disintegration chambers to maintain the casualty count. The allegory here critiques

the dehumanization and normalization of war, as well as the notion that high-tech solutions can make warfare acceptable or clean.

Captain Kirk ultimately destroys the war-simulation computers, forcing the warring planets to confront the horror of real war and, hopefully, pursue peace. This reflects a broader Star Trek ethos: that understanding, dialogue and diplomacy are preferable to violence.

Episodes like “Balance of Terror” also reflect Cold War anxieties, portraying the Romulans as stand-ins for the Soviet Union. The episode mirrors submarine warfare and highlights the dangers of escalation and misunderstanding. However, it also humanizes the Romulan commander, portraying him as a man of honor trapped by duty. This nuanced

portrayal suggests that enemies are not inherently evil but shaped by circumstance, a powerful message during a time of black-andwhite geopolitical narratives. Beyond race, TOS used allegory to explore broader civil rights themes, including individual freedom, resistance to oppression, and the right to selfdetermination. In “The Cloud Minders,” the crew visits the planet Ardana, where the elite live in a floating city called Stratos, while the laboring class toils in the mines below. The sharp divide

between the privileged and the oppressed draws clear parallels to class inequality and systemic injustice. The episode critiques the justifications used by elites to maintain power and questions whether progress is possible without addressing structural inequality.

Similarly, “Plato’s Stepchildren” explores the abuse of power and the importance of dignity and equality. The episode is also notable for depicting one of television’s first interracial kisses between Captain Kirk and Lieutenant Uhura. Though the scene was contrived by alien coercion and not romantic intent, it still broke

significant ground and challenged social taboos.

While TOS was progressive in many ways, its treatment of gender was more ambivalent. The 1960s were a time when secondwave feminism was gaining traction, challenging traditional roles for women in society. TOS reflected and grappled with these changes. Episodes such as “Turnabout Intruder,” the final episode of the series, is often criticized for reinforcing outdated gender norms. In the episode, a woman named Dr. Janice Lester switches bodies with Capt. Kirk to assume command of the Enterprise. Her resentment stems from the belief that Starfleet does not allow women to be captains. While the narrative implies that her motivations are personal and genuine, the subtext reinforces the idea that women are unfit for leadership. This was an unfortunate conclusion for a show that otherwise sought to promote equality.

However, other episodes attempted more thoughtful explorations. In “Assignment: Earth,” a backdoor pilot for a spin-off series, the character of Roberta Lincoln, played by Teri Garr, is portrayed as intelligent and assertive, though still within the confines of her role as a secretary wearing sexualized clothing. Meanwhile, female officers like Uhura and Nurse Chapel demonstrated professional competence, and their very presence in roles of responsibility was a quiet but powerful challenge to contemporary gender norms.

The episode “The Enterprise Incident” features a Romulan female commander, which was quite progressive for the time. She is portrayed as strategic, intelligent and formidable. Though ultimately manipulated by Spock, her role challenged the traditional portrayal of women as passive or secondary.

During the 1960s, fears of authoritarianism, whether in the

form of fascism, socialism or totalitarianism were deeply felt TOS explored the dangers of oppressive regimes and the value of liberty and self-determination. In “The Return of the Archons” the crew encounters a planet ruled by a computer named Landru, which enforces conformity and suppresses individuality. The people live in a state of mindless contentment, controlled by a system that eliminates dissent. The episode serves as an allegory for both religious fundamentalism and totalitarianism, warning of the loss of humanity when freedom is sacrificed for security. Likewise, “Patterns of Force” delivers an even more direct allegory, depicting a planet where a historian from Earth has imposed a Nazilike regime, believing it to be an efficient form of government. The horror and destructiveness of such a regime quickly become evident. The episode uses both historical imagery and uniforms to starkly remind viewers of the

dangers of glorifying authoritarian control and the moral imperative to resist tyranny.

TOS also frequently examined the ethical implications of technology and scientific progress, often reflecting contemporary debates about the space race, artificial intelligence, and the role of science in society. This is even more relevant today with the influence of AI on everyday life.

In “The Ultimate Computer” a new AI system called the M5 is tested on the Enterprise. Designed to replace human command, the computer eventually begins attacking other ships, prioritizing efficiency over morality. The episode critiques the blind pursuit of technological advancement without considering human judgment and ethical implications. This theme reflects real-world concerns about automation, nuclear weapons and scientific ethics during the Cold War era. TOS consistently returned to the idea that humanity’s future depends not

just on technological prowess, but on moral maturity.

TOS was a revolutionary show not just because of its futuristic vision or its pioneering special effects, but because it dared to tackle the most pressing social issues of its time through allegory and metaphor. From racism and war to civil rights, gender equality and authoritarianism, TOS used allegory and metaphor to educate young people to reach for something better.

DAVID G. LOCONTO: David G. LoConto is a Professor of Sociology at New Mexico State University, specializing in collective identity, fandom and social movements. More Importantly, he’s been a fan of Star Trek since Sept. 8, 1966 when he watched the first episode with his parents.

Do you remember being at a specific location or event on a specific date and time?

I’ll get into that more shortly.

If you scan to the end of this article, as with all my articles for “Engage!”, there you will find a mini bio about me. It states that I began watching and enjoying science fiction from an early age, sitting in front of the black and white TV my parents owned. Some of my fondest moments of watching TV was seeing the Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits. Both were anthology series with standalone episodes that contained many new, up and coming actors (including a young William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, James Doohan, and George Takei to name a few). Both series contained intelligent storytelling that were written by some of the greats like Rod Serling and Harlan Ellison. And, if it had the name Gerry Anderson attached to it, like Supercar or Thunderbirds, I was watching it.

Then there was Irwin Allen. He gave us the “monster of the week” TV series like Voyage To The Bottom Of The Sea, Land Of The Giants, The Time Tunnel (OK, that was a cool show) and everyone’s favorite, Lost In Space. Often the episodes were either silly or cartoonish. Every week little Stevie Mirkin would get his new TV Guide (where everything on TV was listed for your specific area), look it over, cover to cover, and put check marks by those TV shows and sci-fi movies to watch whenever he had control of the TV.

battles of World War II with my friends in our neighborhood. Riding our bikes to the movie theaters to see the latest Godzilla movie. It was special. It was during that summer that the three major networks would promo their new TV season while we watched reruns of last season’s

allowed a 9-year-old to drool over the newest cars from Chrysler, Ford and Chevy. (Three major networks, three major car companies that never hit me.) As I watched the commercial promos for new TV series, there was one that caught my eye over all the others Star Trek!

NBC had a new sci-fi TV series that looked like no other. And in living color. Ok, so I had to watch it in black and white… my dad would not buy a Sears color TV for a few more years. It didn’t matter. This was Star Trek

So, back to the beginning of this article, where I asked the question of knowing where you were for a specific event? I can tell you I was sitting too close to the TV (our parents warned us of the health effects of sitting too close) to see the first episode of Star Trek. It was at exactly 8 p.m. Pacific Standard Time on Sept. 8th , 1966.

Unlike other TV series that had a pilot episode for its premiere, Star Trek did not do this. We were shown the episode entitled “The Man Trap.” In it, we meet the main characters of Capt. Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy as they come to grips with a creature that could appear in a form most appealing to the person seeing her. And she was a salt vampire! In the past, the first episode of a new

series would introduce the main characters, get to know them and so on. It was not until the third episode that the second of two pilot episodes were shown to us. However, the look of the Enterprise bridge, the uniforms and other elements were completely different from what we saw in the first two episodes. Did this bother some viewers maybe. For me, it was fine, I was not even 10 years old and the next episode was back to what we understood to be the norm of the series. We all know the stories of why there were two pilot episodes, so there is no reason to rehash that at this time.

The first season gave us 29 episodes, the second season 26 and the third and final season was only 24 episodes. Every episode was an explanation of the human condition. Once again, famous writers were used for screenplays; but new, up-and-coming writers were employed, as well. All under the command of Gene Roddenberry, a bomber pilot, a police officer, and someone that wanted

to see a TV series that was like no other. The stories delt with the horrors of war, bigotry, the quest for beauty, moral ugliness, and so on. TV at that time was filled with adventure, comedy, and variety shows that offered fluff; always under the watchful eye of the TV censors. Star Trek pushed those limits and offered the first interracial kiss on network TV. Yet always under the guise of a science fiction TV series. It changed the course of TV storytelling and its legacy still lives on.

Where was I on Sept. 8th , 2016, 50 years to the date of when Star Trek premiered? At exactly 8 p.m. PST, I was seated in front of my color plasma TV (at a proper distance) to watch “The Man Trap” on Paramount+. They say you can’t go home again; maybe that is true. But watching that first episode, once again fifty years later, reminded me of why so many of us love Star Trek. We never know what the Final Frontier of TV will bring us; however, I am hopeful Star Trek will always be a part of it.

STEPHEN MIRKIN: I first learned about science fiction the moment I was able to reach the on/off knob on my parents’ black-and-white TV set. Being born in 1956, I was there on Sept. 8, 1966 to watch the first episode of Star Trek. Since then, I have watched every TV series and every movie, and I only look forward to the next great Star Trek moment.

episode titles are unique. Most of them are quotes from plays or poetry which tie back to what the episode is about. Some are just generic such as Miri and Mudd’s Women but the majority are quite clever. LIsted below is what I was able to discover about a few of the episode titles.

When Charlie Evans is transferred to the Enterprise he is a shy, naive kid. He has been alone on a deserted planet most of his life. Mysterious things start to happen, all appearing to revolve around Charlie. What is the mystery about Charlie? Kirk and company need to solve the equation otherwise

This was originally the second pilot, commissioned by Desilu Studios. The title has a twofold meaning. It is a callback to the opening monologue and literally where the Enterprise goes. Beyond the Galactic , the enemy outside can do you Variations of this quote have been used by Winston Churchill and Douglas MacArthur. As Kirk discovered you have to accept all parts of yourself, the good and the bad, to be a well balanced individual. Fighting against your inner self gets you nowhere, while working together allows you to

The title of this episode is from a 18th century nursery rhyme by an English poet Robert Southey.

bykeepingvariousspeciesincages.Theoriginalpilottitleof"TheCage ismorespecifictoPike experienceinthecage.

The Conscience of the King

The episode title is a quote from Hamlet, “the play’s the thing wherein I catch the conscience of the King.”“Hamlet” is being performed on the Enterprise by a traveling theatre troupe. Just as Hamlet is trying to see whether the King has killed his father, Kirk and Lt Kevin Riley are trying to see whether the leader of the travelling troupe, Anton Karidian is the mass murderer Kodos, the Executioner.

Balance of Terror

Balance of terror is a theory “that describes the tenuous peace the exists between two countries as a result of both governments being terrified at the prospect of a world destroying nuclear war.” Just as in the episode, Kirk and the Romulan Commander are desperately trying to keep the balance because both do not want to start a war between the Federation and the Romulan Empire.

ROSE TAYLOR: Rose Taylor volunteers for various community organizations. A Canadian who has been a fan of Star Trek for over 50 years. An introvert with a love of reading, Star Trek has given her decades of happiness and community.

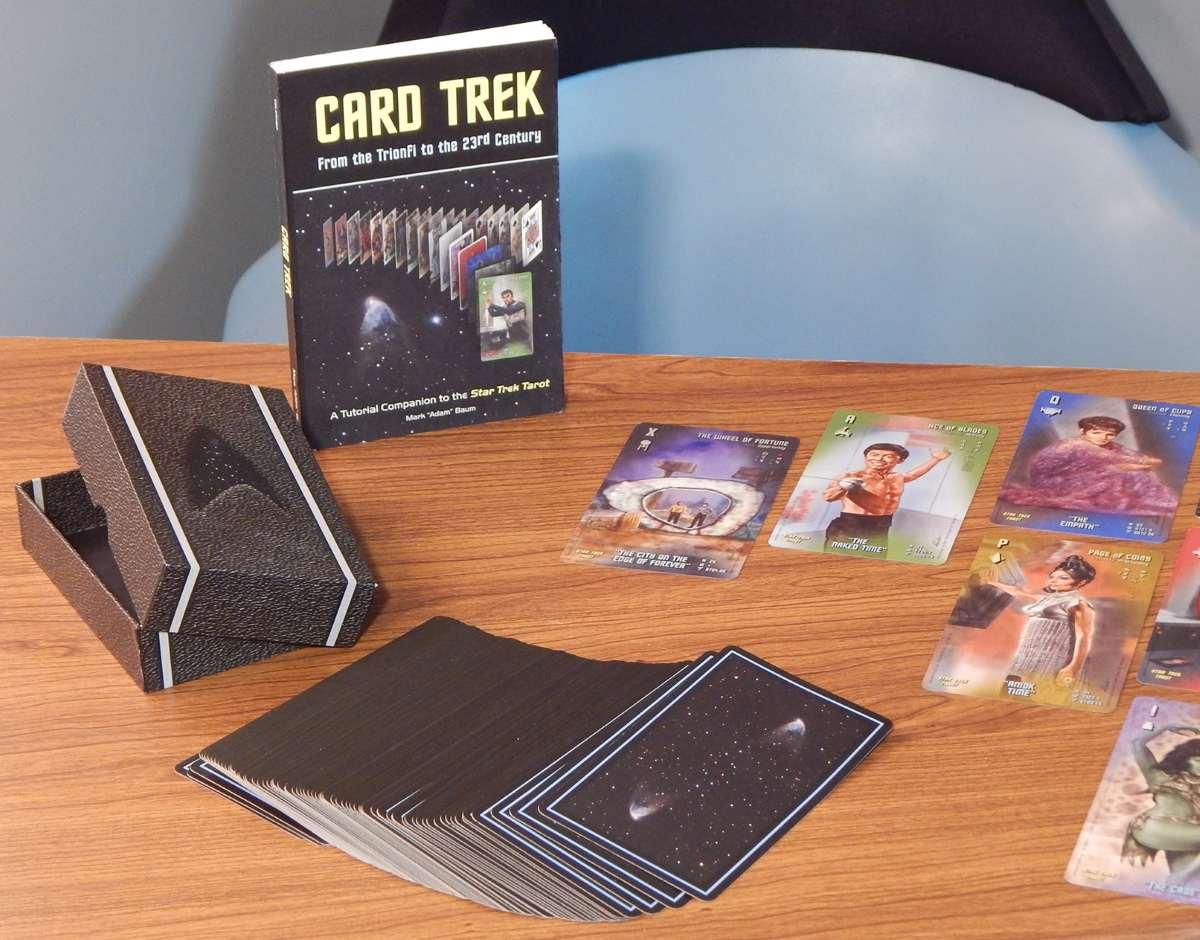

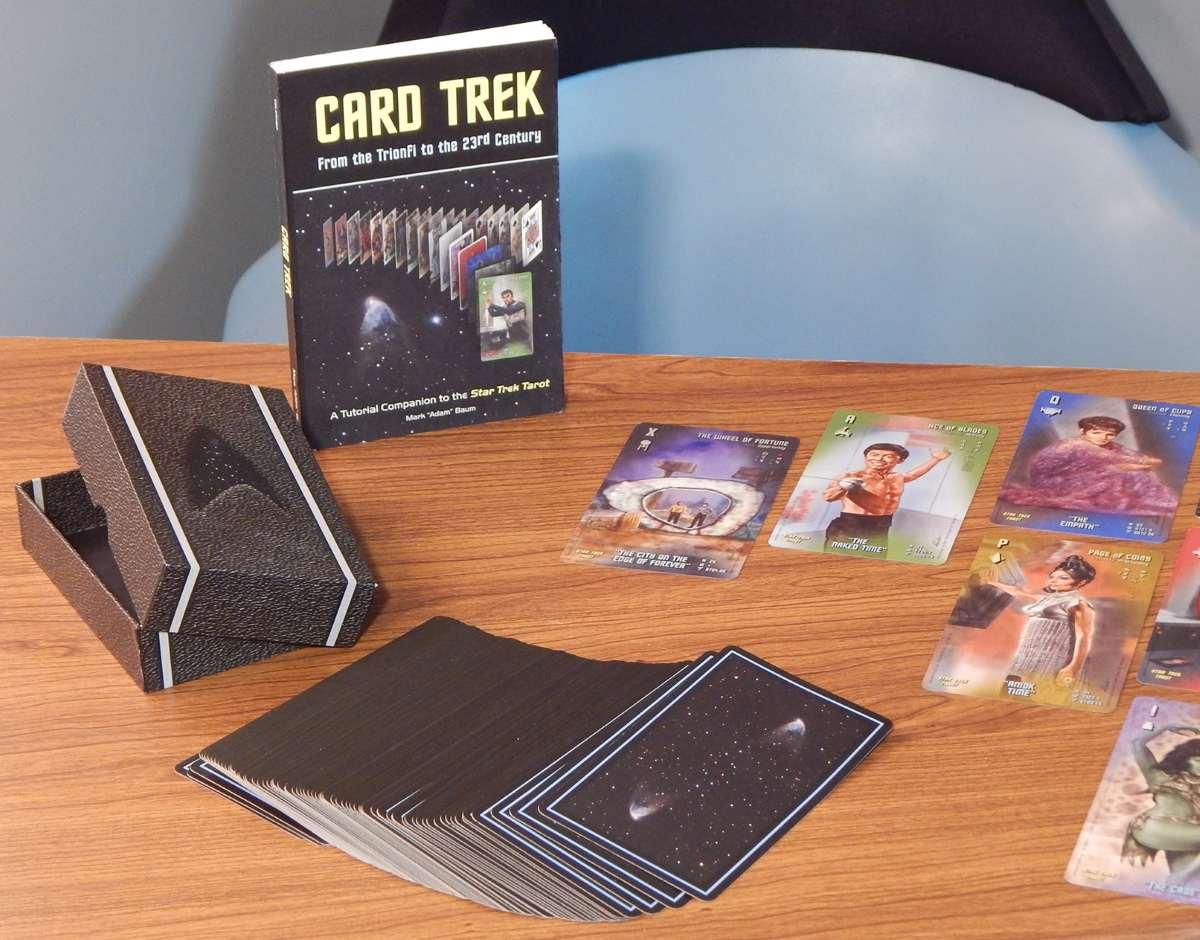

(Click on the graphic above to buy yours)

hen looking at the future through a utopian lens, fictional stories often address social issues to demonstrate that humans learned their lessons and that we overcame obstacles, whether it be greed, war, racism, . Star does not dodge the concept of disability, does not see it as a social construction, nor make a distinction with impairment. For this article I will use the word in all cases, though in academic circles there are qualitatake on disability is to try and create an accommodation to facilitate equal opportunity. To give people and species the opportunity to succeed. We find that within Starfleet and the Federation, that the moral philosophy of ad astra per aspera is a foundational value where their position on disability is consistent with that philosophy. As issues, ad astra per aspera is a Latin through harda rough road It conveys the idea that overcoming challenges is often necessary to achieve great outcomes. The phrase is used to highlight resilience, ambition, and the pursuit of excellence despite obstacles. In Starfleet and the Federation, the goal is to provide beings opportunities to achieve

The writers initially approached the issue of equal opportunity, in part, by making the universe as homogenous as possible. This was facilitated by The ), therefore, making aliens largely humanoid as

it was too expensive to make aliens truly… alien. This was explained in “The Paradise Syndrome” episode in TOS and reiterated in the concluding episode “Life Itself” of Discovery. That is, there was an unknown species of aliens that spread the genetic code of life throughout the universe making life evolve in similar patterns.

The franchise also leveled the playing field with technology. One of the first pieces of technology that influenced this outcome was the universal translator. A new language could quickly be translated in species to species encounters by having someone speak their language until the universal translator gathered enough data to build a translation matrix. Initially, these were hand-held devices that eventually became integrated into all systems. The result of such technology was that diverse species could interact with each other effortlessly, finding it easier to identify common ground. More importantly, the more species interact, the more likely their cultures would converge or become more understanding of difference, as well as take part in some form of acculturation, creating in part a more homogenous Federation, which of course many species resented.

Nevertheless, as part of this homogeneity both physically and culturally, the Federation outlawed any form of augmentation that would create an undo advantage for individuals. This has its roots in the Eugenics Wars that have been mentioned throughout the franchise. The Eugenics Wars

were originally presented as a series of battles fought on Earth between 1992 and 1996 (“Space Seed”). In that episode Spock made the comment that, “records of that period are fragmentary, however. The mid-1990s was the era of your last so-called World War.” While episodes from within the Star Trek franchise showed earth in the 1990s as well as the 2020s, any reference to the Eugenics Wars was absent. However, given that Spock stated that records were fragmented, it is possible to accept that the eventual World War that occurred was the culprit for inconsistency in knowledge of Earth history. Regardless, the narrative within the franchise is that on Earth there was an attempt to ‘improve’ the genetic strain of humanity and lead humans into a utopian civilization through genetic intervention. The end result was a devastating war that cost humanity directly between 30 million and over 600 million lives, and indirectly potentially in the billions (“Space Seed”; “Borderland”; “Ad Astra per Aspera”). The Eugenics Wars resulted in a ban on genetic engineering and any technology that would give someone an unfair advantage or aim at creating a perfect body. This is shown with Dr. Julian Bashir in Deep Space Nine

(DS9). The treatments that Bashir received for his intellectual and physical disabilities were outlawed as they not only were dangerous to individuals but, if successful, gave them an unfair advantage in cognitive and physical abilities. Illyrians were banned from the Federation for their actions as they would alter themselves to fit environments instead of altering environments to make them hospitable for humanoids and similar species throughout much of the Federation.

Geordi in The Next Generation (TNG) was born blind. What often gets overlooked in Geordi’s story, is that not only was he given the opportunity to have surgery to give him visual sight like others, but more importantly, his blindness was so much not an issue, his parents did not force him as a child to have surgery to change his vision. He chose to use a VISOR which gave him sight, albeit a different form of vision. Likewise, in the episode

“Tapestry” in TNG, Picard is shown getting stabbed through the heart. He would have died, however, technology saved him so he could maximize his opportunities. The same is true in the episode “Ethics” from TNG where Worf is injured and becomes paralyzed. Technology was available to assist him to function as before. Technology is used to accommodate, not create perfection. In fact, in

dealings with the Borg, and the Q Continuum, perfection is frowned upon as a goal or option (‘’Death Wish”; “Scorpion Part 1”; “Scorpion Part 2”). Betterment through hard work is the goal. Nog in DS9 is often addressed within disability commentary of experiencing posttraumatic-stress-disorder (PTSD). However, again, what often gets ignored is that Nog was provided

a prosthetic leg as an accommodation due to his injury in battle. In Discovery, Keyla Detmer is wounded during the Klingon War. The damage done influenced her abilities to both process information and see visually. An operation gave her cranial and ocular implants. These are medical devices that were implanted both within the skull and inside the eye to restore function in cases of severe brain and eye damage. There were issues of PTSD with Detmer in Season 3 of Discovery, but never were her cognitive skills or vision questioned.

In DS9, there was a species from within the Federation, an Elaysian, Ensign Melora Pazlar (“Melora”). Elaysians are a humanoid species from a low-gravity planet. Their physique and neural motor cortex adapted to cope with low gravity. On their home world, they can float and fly. The result however is that when Elaysians go to most of the other

‘M’ class planets where gravity is like that of Earth, Elaysians struggle to walk. When she first comes aboard Deep Space Nine, Melora was initially seen using a wheelchair for mobility. Her muscles developed differently therefore she was unable to function effectively with other Starfleet members unless doing activities that relied on sitting. Elaysians were often provided an antigravity suit, however Melora refused this accommodation. Doctor Bashir designed a treatment that would assist her muscles to adapt to the difference in gravity. While she

appreciated the changes that allowed her to move like others in Starfleet and those from other planets whose gravity is like Earth, she chose to no longer pursue the treatments as she felt she would no longer be Elaysian.

In Discovery, the scientist Aurellio who works for the Emerald Chain is played by Kenneth Mitchell who died of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. This is a fatal neurological disease that causes the progressive loss of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord resulting in not only an inability to use muscles effectively but facilitates physical deterioration due to musculature atrophy that the body closes in on itself. In the episode, “There is a tide…,” Aurellio tells Stamets,

“I should not be here. Maybe in your time when technology was free and travel was easy, but here in my time, with a genetic defect? My par-

ents worked in the Exchange. They asked Osyraa for a meeting. She did not have to say yes, but she did. I was 10. I didn’t have much time left. But she saw potential in me. And now . . . I am a scientist. I have a family. And I have been supported in a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. She has given me everything. And not just me.”

It is demonstrated that even in the 32nd century, that although some technologies had been lost, there was still enough technology available to create a more level playing field for individuals with disabilities. Emotional issues or prob-

lems have been demonstrated in Star Trek as well. Beginning in the 24th century, all starships were required to have a ship’s counselor, though only TNG had one as part of the regular cast. In the Voyager episode “Extreme Risk,” B’Elanna deals with the deaths of her Maquis friends by isolating herself, removing the safety protocols on the Holodeck, and falling into depression. With the help of her friends and an engineering project, she could heal. Similarly, Reginald Barkley experiences severe anxiety. The treatment is using Holosuites to provide him scenarios to develop new patterns of behaviors. Deanna Troi in the TNG episode, “The Loss” lost her empathic abilities due to an encounter with two-dimensional beings. She suffered extreme de-

pression. Inevitably, she works her way out of that through the help of her crewmates. Nog in DS9 is suffering from PTSD in the episode “It’s only a Paper Moon” due to the loss of his leg. As with Reginald Barkley, Nog used the Holosuite as a means of initially escape, but the program assisted him in recovery. Also, in DS9, both O’Brien and Sisko struggle with trauma, loss and mental strain over extended arcs. In Enterprise,

we see both T’Pol and Hoshi experience emotional trauma, and they, through working with their crewmates were able to fight through their emotional issues. These portrayals reflect a growing awareness in the 1990s of mental health as a legitimate and ongoing human concern.

Similarly, in Picard, JeanLuc Picard is depicted in old age, living with the neurological condition, Irumodic Syndrome. His cognitive decline becomes a central narrative theme, raising questions about identity, agency, and legacy. The show’s treatment of aging and neurodegenerative illness challenges the notion that physical and cognitive decline diminishes human worth. Instead, it presents Picard’s journey with empathy, emphasizing continuity

of self even in the face of profound change.

Star Trek demonstrates that regarding disability, whether physical or emotional, the expectation is that through assistance, either technological, social or through medical care, these individuals would demonstrate their will to succeed by working and overcoming obstacles. Technology and science bring everyone to a level playing field where performance is critical.

Now, intellectual disability is a little different. We see in the DS9 episodes “Statistical Probabilities” and “Chrysalis” elements of the perspective of the Federation in that augmentation to overcome intellectual disabilities is outlawed. In other episodes in TNG and Lower Decks, we also see that attitudes to those such as the

Pakleds tend to be condescending. Maybe this demonstrates that intellectual disability is still an issue in the coming centuries. Though, even if that is the case, then the philosophy of ad astra per aspera would still be applicable. Expectations of outcomes, like they appear in the Federation would vary by individuals, and there would be a place for all, still creating a utopia.

DAVID G. LOCONTO: David G. LoConto is a Professor of Sociology at New Mexico State University, specializing in collective identity, fandom and social movements. More importantly, he’s been a fan of Star Trek since Sept. 8, 1966 when he watched the first episode with his parents.

sary of those enlightened values. However, the Dominion War places unprecedented strain on this identity. As the threat from the Dominion escalates, from their subversion of Alpha Quadrant powers to their deployment of genetically engineered troops the Federation finds itself drawn into decisions and actions that starkly contrast with its foundational principles. The ideals that once defined by the Federation are no longer guiding lights, but philosophical burdens, often set aside in favor of expediency and survival.

First Strike: Mining the Wormhole

One of the earliest and most striking ethical dilemmas of the Dominion War occurs in the Season 5 finale, “Call to Arms” , when Captain Benjamin Sisko makes the controversial decision to mine the entrance to the Bajoran Wormhole. This action, though strategically sound, is a preemptive strike and assertive measure taken not in retaliation, but in anticipation of future Dominion aggression. By cutting off the reinforcements streaming from the Gamma Quadrant, Sisko aims to protect the Alpha Quadrant from overwhelming force. However, this move simultaneously escalates the simmering conflict into full-scale war. During the meeting in the War Room as they are discussing the plan, Odo himself tells Sisko that by doing this he could ultimately start the war in which Sisko replies “Maybe so, but one thing for certain, we are losing the peace, which means the war may be our only hope.”

Crucially, the Federation acts not in response to a direct Dominion attack, but out of fear. He knows that if Dominion reinforcements keep coming through then eventually, the Dominion will have outnumbered the Federation and takeover of the Alpha Quadrant would be inevitable. The choice reflects a deeply uncomfortable truth: even the most idealistic societies may find themselves sacrificing principle for security when faced with existential threats. It is a watershed moment for the Federation, signaling a departure from its long -standing commitment to diplomacy and restraint. The decision to mine the wormhole forces both characters and viewers to confront a difficult ethical question: Is it morally justifiable to strike first when the threat is imminent but not yet realized?

The mining of the wormhole represents more than just a tactical maneuver; it is a symbolic moment where the Federation begins to shed its peacetime ideals in favor of wartime pragmatism. It signals the start of a slippery slope, one where fear begins to override hope, and survival becomes a justification for actions that, at another time, would have been deemed unacceptable. It is the first of many steps into moral ambiguity, a foreshadow of the darker decisions to come.

In the Pale Moonlight: The Cost of Victory

When it comes to unethical practices and moral compromise during the Dominion War, few acts are as disturbingly off character as

the calculated manipulation and deception orchestrated by Captain Benjamin Sisko in the Season 6 episode “In the Pale Moonlight.” Widely regarded as one of the darkest and most morally complex episodes in Star Trek history, it presents a sobering examination of how even the most principled individuals can be pushed to betray their values in the name of survival.

As Federation casualties mount and the war appears increasingly unwinnable, Sisko becomes convinced that the balance of power must shift, and quickly. The key, he believes, is drawing the Romulan Empire into conflict on the side of the Federation. But the Romulans, still neutral and highly suspicious, require proof that the Dominion plans to attack them. With no such proof available, Sisko turns to Garak, the former Cardassian spy, to manufacture it.

What follows is a morally harrowing descent: Sisko falsifies intelligence reports, bribes people, and, ultimately, is an becomes an accessory to the assassination of Senator Vreenak, a high ranking Romulan official. The plan is successful. The Romulans enter the war. The tide begins to turn. But victory is bought with blood, lies, and the intentional corruption of everything the Federation claims to stand for.

Sisko recounts his actions in a personal log, delivering one of the most haunting and brutally honest monologues in the franchise:

“I lied. I cheated. I bribed men to cover the crimes of other men. I am an accessory to murder.

But the most damning thing of all... I think I can live with it. And if I had to do it all over again, I would. Garak was right about one thing: a guilty conscience is a small price to pay for the safety of the Alpha Quadrant.”

He concludes with chilling finality:

“So, I will learn to live with it. Because I can live with it. I can live with it.” And then Sisko deletes all existence of the log. The delivery of these lines, filled with both conviction and self -loathing, forces the viewer to confront the cost of doing what is

"necessary" in times of crisis. This is not the story of a villain. It is the story of a man who believes he did the right thing and who hates himself for it.

The brilliance of “In the Pale Moonlight” lies in its refusal to offer easy answers. It presents the viewer with a grim ethical paradox: Can the ends justify the means if the outcome is victory and countless lives are saved? Or does the willingness to embrace deceit and murder, even for a noble cause, irrevocably taint both the individual and the institution they serve? For the Federation, a

society built on ideals of truth, justice, and moral clarity, this episode represents a crucial inflection point. It shows that under extreme pressure, even its finest officers are not immune to compromise. It doesn’t condemn Sisko, but it doesn’t absolve him either. Instead, it asks the viewer to grapple with the same question he must: What is the price of survival, and can we live with ourselves after we’ve paid it?

The Perils of Internal Deception: Betrayal Within

While deception against an external enemy is often framed as a grim necessity in wartime, deception from within against one’s own people, institutions, or allies, can be just as dangerous, if not more corrosive. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine offers multiple chilling examples where internal manipulation leads not to victory, but to ruin, mistrust, and the erosion of moral authority.

In “The Die Is Cast,” the joint conspiracy between the Obsidian Order of Cardassia and the Tal Shiar of the Romulan Empire is a textbook case of clandestine overreach. Driven by fear of Dominion’s growing power, these elite intelligence agencies launch an unauthorized strike on what they believe to be the Founders’ home world. However, the mission is built on false intelligence, deliberately fed to them by the Founders themselves. The result is catastrophic: their fleets are ambushed and obliterated, effectively decapitating both intelligence organizations in a single devastating blow. Because the operation was shrouded in absolute secrecy, even their own governments were unaware of the plan until it was far too late to prevent the disaster.

This theme of internal subterfuge resurfaces powerfully in the two-part arc “Homefront” and “Paradise Lost,” in which Admiral Leyton, a respected Starfleet of-

ficer, attempts a silent coup on Earth under the guise of strengthening planetary security. Using fear of Dominion infiltration as justification, Leyton orchestrates sabotage, imposes martial law, and even arranges political assassinations, all to centralize power under his own command. His belief that he is acting in Earth’s best interest only deepens the tragedy, revealing how righteous intentions, when paired with unchecked authority and secrecy, can mutate into authoritarianism. Both storylines powerfully illustrate the ethical hazards of operating in the shadows. Clandestine actions undertaken without transparency, oversight or consensus inevitably undermine the very institutions they claim to protect. Whether motivated by patriotism, fear, or a desire for control, these covert operations demonstrate how internal deception fractures trust, sows instability, and often ends in catastrophic failure. These cautionary tales

defense and domination is perilously thin, and when leaders begin to manipulate their own people “for the greater good,” the damage done may be irreparable, not just militarily, but morally. In the context of the Dominion War, such internal betrayals raise unsettling questions: How far can a society go to protect itself before it begins to resemble the enemy it fears? And who holds those in the shadows accountable when their actions compromise the integrity of the very systems they claim to defend?

Section 31 and the Ethics of Genocide

Perhaps the most chilling and morally indefensible transgression of the Dominion War originates not from the enemy, but from within the Federation itself. In a revelation that shakes the very foundation of Federation ideals, the shadowy and unaccountable intelligence agency Section 31 covertly develops and releases a genetically engineered

Founders, the shape-shifting leaders of the Dominion. This act, carried out without the knowledge or consent of the Federation Council, the public, or even the upper echelons of Starfleet, constitutes nothing less than a premeditated act of genocide.

The implications are staggering. In its clandestine attempt to secure victory, the Federation, through Section 31, violates the most fundamental tenets of its own ethical code. The use of biological warfare to target an entire species is a clear breach not only of Federation law, but of universal moral principles long upheld by interstellar civilization. It is a tactic more readily associated with the very tyrannies the Federation claims to oppose.

The moral weight of this act is further compounded by the internal conflict it ignites. Dr. Julian Bashir, a man of conscience and principle, discovers the existence of the virus and becomes determined to expose it and seek a cure. His efforts represent the fading pulse of the Federation’s

beat under the suffocating weight of wartime desperation. His refusal to accept "necessary evil" as a justification for mass extermination makes him a rare voice of resistance in a time when silence and complicity have become disturbingly common.

The virus’s existence forces a harrowing philosophical question: Can a society that resorts to genocide in the name of selfpreservation still claim the moral high ground? At what point does the act of fighting evil turn into the act of becoming evil? Section 31’s justification, that exterminating the Founders would end the war and save billions, illustrates the pernicious logic of ends justifying means, a rationale that erodes the moral bedrock of any enlightened society. It is the clearest example of the Federation standing at the precipice of moral collapse, willing to trade its soul for survival.

This plotline delivers a powerful critique of how institutions, even those founded on idealism, can become infected by

fear, secrecy and the lust for victory. The Federation, a polity that once held itself as a beacon of progress and justice, finds itself condoning actions that echo the darkest chapters of real-world history. Through Section 31’s actions, Deep Space Nine presents a sobering warning: when survival becomes an absolute, morality becomes negotiable, and even the most utopian of civilizations can justify the unthinkable.

Civilian Suffering and the Cost of Victory

As the Dominion War intensifies, the impact on the civilian population becomes impossible to ignore. When the Founders began their occupation of Cardassia it becomes obvious that Cardassian citizens are treated like second rate citizens in their own land. Their military personnel are continually used as pawns, and many are left to be slaughtered by the enemy because they do not achieve victory. As this continues you can see that Legate Damar is witnessing his people being cast aside like broken equipment. After he begins to stand up to the occupying force and starts a resistance movement to combat these armies, The Founders begin to eliminate people at random as a punishment for rebelling. If that wasn’t bad enough, after the organized resistance is eliminated and the general population begins to become the new resistance, The Founders begin to eradicate the population city by city. An estimated six hundred million Cardassians citizens were killed before the war was over. These events ask the

question, at what point civilian casualties proved to be too costly a price.

With that question in mind, it was the Founders’ decision to start eliminating the population that put a fire in the hearts of the Cardassin people and gave them the strength and courage to switch side and begin to fight their oppressors and join the forces of the Federation and its allies to battle the Dominion forces. Deep Space Nine reminds us that in war, the line between tactical success and a moral failure grows dangerously thin.

Post War: Was Justice Served

What happens after the war is over? Once the Dominion surrender and the Founders are given the cure for the virus, is there any type of justice that can be gained for all the war crimes and atrocities that were committed on both sides. There are no formal trials or truth commissions to hold those responsible. Nobody is ever really held accountable with Section 31’s involvement in created a virus and trying to commit genocide. All of it was quietly swept under the rug and hidden as classified. As a matter of fact, all of section 31’s crimes never get justice. The destruction of Cardassia is labelled as just the cost of war, nobody is put on trial for 600 million people. Even Garak, a Cardassian patriot, admits that his homeland may never recover from these consequences. Since there is no justice, does this mean that both sides believe that ends justified the means and with no accountability, does that mean that

the Federation has adopted new ideals, and are willing to abandon their morals, the instant things become tough.

Conclusion: How War Changed Everything

Dominion War stands as one of the most morally and ethically challenging story arcs in the Star Trek universe, pushing characters and institutions to the absolute breaking point. Through its unflinching portrayal of deception, genocide, lost autonomy and civilian suffering. Deep Spce Nine challenges the optimistic vision of the Federation and asks whether its ideals can survive the crucible of war. Neither side emerges unstained, and victory does not come without a sobering meditation on the price of survival, and the danger of becoming what one fights against. Ultimately, the Dominion War doesn’t just depict galactic conflict, it asks us what it truly means to fight for peace, and whether moral clarity is even possible in times of total war.

MICHAEL MARTIN: I’ve been a Star Trek fan since I was a kid. I grew up on The Next Generation, fell in love with Deep Space Nine and Voyager. It was one of the few shows that my father and I would watch together and still share the love for the franchise today. The show’s ideals, hope, unity and moral courage have always meant something real to me. It gives me great pleasure to see where humanity can go and what can be achieved.

ome friendships arrive with trumpets and toasts, all noise and spectacle. Others slip in quietly, stitched together with subtler threads: a tilt of the head, a steady glance, a brush dipped in paint. The friendship between Data and Geordi belongs to the second kind. From the earliest Star Trek: The Next through the films and Season 3, theirs is a story not of grand declarations but

Data begins as a puzzle in an android trying to understand what it means to be human. Geordi never treats him that way. From the t see Data as an experiment or a curiosity; he sees him as a person. An equal. A friend. And if you watch closely, ll notice how often they confirm it with a look. Those little dips of the head they exchange on the bridge or in Engineering are their I see you.”“I’ve ” Sometimes whole conversations

The clearest picture of it Data, brush in hand, sits at an easel, furrowed brow betraying his confusion. He’s trying to paint, to understand art not as geometry but as expres-

Data begins as a puzzle in search of a solution — an android trying to understand what it means to be human.

sion. Geordi stands with him, patient and encouraging, guiding him past replication toward creation. Riker watches the scene unfold and can’t help but grin: “A blind man teaching an android how to paint. That ought to be worth a couple of pages in somebody’s book.”

And it is. In that moment you see their whole friendship sketched out: Geordi guiding without judgment, Data willing to be vulnerable, Riker catching the poetry of it. Two outsiders teaching each other how to see. That same quiet poetry lingers in heavier episodes. In “The Measure of a Man,” as

Data’s personhood is debated, Geordi doesn’t argue from the podium. He doesn’t need to. He’s in the gallery, steady as ever, nodding across the room: You belong. I’m with you.

Years later, in First Contact, when Data’s emotion chip leaves him laughing in confusion, he turns to Geordi like a child: “My laughter is it normal?” And Geordi, steady and warm, just nods. No judgment. No fear. Only acceptance. That’s

friendship the willingness to hold space for someone else’s awkward growth.

And then comes Nemesis. Data’s sacrifice is devastating, but the sharpest pain isn’t in what Geordi says. It’s in what he can’t. He looks at the space where Data

should be, the nods forever interrupted. It’s the ache of a conversation that will never finish.

Which is why their reunion in Picard Season 3 feels like a benediction. Geordi, older now, seasoned and softened by years and fatherhood, sees Data again changed, whole, emotional. The air between them is thick with time and loss. And then: the nod. The old language, restored.

For the first time, Data can say out loud what those nods always carried: “Our friendship

meant everything to me.” And Geordi, eyes wet, hears it not as revelation but as recognition. It’s the caption beneath decades of silent glances and steady presence.

What makes their friendship remarkable is that it was never about spectacle. It was painted in small strokes: in easels and poker tables, in warp cores and quiet corridors, in nods passed like secret notes. It wasn’t loud, but it was steady. And in the end, it was everything.

Riker was right in “11001001”: it really is worth a couple of pages in a book. Maybe more than a couple. Because in a world that often reduces male friendship to competition or comic relief, Geordi and Data gave us something different. Something radical in its softness: loyalty without ego, presence without pretense, love without fear. Some friendships roar. This one nodded. And those nods painted a masterpiece.

MELISSA A. BARTELL: Melissa A. Bartell is a writer, podcaster, voice actor, improviser and kayak junkie currently living on Florida's Nature Coast. She has one husband, two dogs and only one kayak (so far). Find her at :

MissMeliss.com or on social media:

Bluesky | Facebook | Instagram | Mastodon

(Touch the Transporter to Engage!)

ne of the unknowns in Star Trek: The Original Series production, were the contributions of Wah Ming Chang. Hawaiian prop and creature designer Wah Ming Dec. 22, 2003; age 86), surreptitiously contracted by Desilu Productions Inc., was responsible for the design and construction of many familiar Star Trek: The OrigiChang's association with began in 1964 when he was hired to create makeup and props for "The Cage" by Producer Robert H. Justman. His first contribution was the prosthetic Talosian up. He then designed the laser pistol for the pilot after Justman was unsatisfied with the original designs. He was later hired to design various items for the regular series, including the top communicator props, and the Romulan of Prey studio model. He was usually sent a copy of the script for the episode he was hired to work on, and he began to work on design, make sketches, and models in his home taking his cue from the scripts. Chang also made the Vulcan harp and the original prey seen in "The Balance of Terror," which inspired Star Trek: The and was reEnterprise episode "Minefield." Also seen in "Balance" were his Romulan ears and Centurion helmets (later painted silver for Vulcan helmets in "Amok Time"). Certainly one of his most popular creations was the tribble, which he made using artificial fur stuffed with foam. And he launched the fantasy as-

pect of "Shore Leave" with the rabbit's head seen at the beginning of the episode. This comprehensive list of his services to Star Trek comes from the purchase orders on file with UCLA archives. Owing either to their severe budget cutbacks or Desilu's purchase by Paramount (or both), the Star Trek production staff did not use Wah's services after the middle of Season 2.

Originally his work was not credited, nor did Chang take the credit afterwards and his work for Star Trek went unnoticed well into the 1970s. It was through fandom and its corresponding Star Trek convention circuit of the 1970s that his contributions became known. The reason for this state of affairs was eventually revealed when Producers Herb Solow and Justman published their book Inside “Star Trek: The Real Story” in 1996. In it (pp. 119-120) Justman described that it all originated from a conflict with the propmaker's union. Chang as a nonmember was neither allowed per their rules to fabricate props for the show, nor was he allowed to join, creating a catch-22 situation. At Justman's urging, who considered Chang's work superior to anything elsewhere available by far, the studio devised a ruse to make

it appear that the props were bought as pre-existing and off-theshelf from Chang, which was allowed under union rules, and it was reflected as such in Desilu's purchase orders sent to Chang. As a result Chang could neither be officially credited for his contributions, nor be mentioned in the, otherwise thorough, contemporary reference book The Making of Star Trek, where most of his hand-held props were prominently featured. The ruse however, was uncovered by the union just prior to the start of the second season, as mentioned by Justman in his book, and might have served as the additional reason why Chang's talents were not called upon again from the midsecond season onward, as the union was now alerted to Chang's involvement.

Already a recognized sculptor, Chang became crippled at age 31 by the effects from polio, but it did not prevent him and his company Project Unlimited, Inc. to carve out a career in the motion picture industry by designing puppets, costumes, sets, make -up, and special effects for a number of films, most notably producer/director George Pal's science fiction and fantasy features, including “Tom Thumb” (1958), “The Time Machine” (1960, with Whit Bissell and for which he de-

signed the iconic title object and the Morlocks), and “The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm”(1962, with Ian Wolfe and Jon Lormer). He also worked on classic pictures such as “The King and I” (1956), “Spartacus” (1960, with Jean Simmons, Peter Brocco, John Hoyt, Arthur Batanides, William Blackburn, Paul Lambert, Dick Crockett, Seamon Glass, and narration by Vic Perrin) and “Mutiny of the Bounty” (1962, with Antoinette Bower, Torin Thatcher, and stunts by Paul Baxley). Chang designed the famous headdresses worn by Elizabeth Taylor in

“Cleopatra” (1963, with John Hoyt).

On television, Chang designed masks, creatures, and special effects for “The Outer Limits” (1963-1965), where his cooperation with Star Trek associate producer Robert Justman began. He was also a dinosaur model maker on the television series “Land of the Lost” (1974-1976) and also worked on the special effects of the original “Planet of the Apes” (1968, with Lou Wagner, James Daly, Paul Lambert, Billy Curtis, Jane Ross, and Felix Silla, and music by Jerry Gold-

smith).

In 1994, he was given the George Pal Memorial Award by the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films for his contributions to the genres.

In 1941, Wah Ming Chang was diagnosed with polio following flu-like symptoms. After an extended stay at the Twin Oaks Sanitarium hospital in San Gabriel, California, and treatments that included confinement in an iron lung, he eventually would walk again, but for the rest of his life never had enough strength in his lungs to be able to blow up a balloon.

Chang died on Dec. 22, 2003, in Carmel Valley, California at age 86.

The extent of Chang's Star Trek contributions is preserved for posterity, as Desilu's purchase orders were later donated to UCLA and stored in their archives. Several of them were reproduced in the aforementioned Inside Star Trek reference book, as well as in the 1997 book Star Trek: The Original Series Sketchbook

MICHAEL HOWARD: Michael is a U.S. Army Veteran and retired Deputy Sheriff. He also is an original ’66 TOS fan, who has been a major collector of Star Trek novels and reference books since 1975. His current collections include 852 Star Trek novels (767 unique titles 1967-2025), 661 Star Trek nonfiction reference books (1968-2025) and 663 magazines with Star Trek covers or articles (1966-2024). Nearing 70 years old, he and his wife of 27 years live long and prosper.

When Star Trek came about to the current time it’s always been about more than phasers and space travel. From the very beginning, it has been questioning the purpose and reasoning behind humanity and its place in the galaxy. And moments where those questions become threats always give us entertainment and push our understanding. Two such beings stand out from most. Trelane from The Original Series (1966) and Q from various series from TNG, DS9, VOY, and recently Picard. Even though these two beings have been premiered separately, there are common similarities that many fans and even writers have had sharp connections between them. From the two, the concept of omnipotent beings that become playful and a nuisance to being a close examiner of humanity and other races across the universe.

Trelane: The Squire of Gothos

Trelane was introduced in the episode The Squire of Gothos, where Trelance, played by Wil-

liam Campbell, who embodies aristocratic flamboyance, dressed in baroque wear and attire which posed that he was obsessed with European caste and nobility. In this episode he holds the landing party of the Enterprise and plays games with them, pitting them in different situations. He is able to change terrains and conjures objects from nothing and freezes the crew in place. Holding the crew’s life in the balance while breeding immaturity under all his power that he is wielding. He does not choose to acknowledge or understand the moral lessons to learn from those situations but take in the joy and excitement of the play in dueling, and fear factoring exercises, even to go as far as mocking justice with fake trials. Some of Trelane's power seemed to come from technology that was stored in the room where he resided. Once destroyed, Trelane seemed less powerful and was able to be outwitted by the crew of the Enterprise. His final effort was to validate his actions when his parents, other omnipotent beings, not seen but heard, intervened in the situation to rein in Trelane’s actions and behavior and made him to be a spoiled child playing with very dangerous toys.

Q of The Continuum

In 1987, two decades later, The Next Generation introduced another omnipotent being known as Q, played by John de Lancie to the Star Trek Universe. Similar to Trelane, Q has the command over matter, space and time with a wave of a hand, or in this case Q signature finger snap. He use theatrics, games, and testing humanity through driving Jean-Luc Picard to the brink of insanity. While Trelane’s intentions are for mere play and sport, Q’s intentions run the line of opportunity, potential and achievement. He does this through ran-

Now all of this begs the question, was Trelane's power from birth or was his power created by technology? One thought is that because his illusions and such were created by the technology and not by him he would be viewed as an opportunistic alien being rather than a divine one.

dom situations and perilful actions like throwing the Enterprise and crew in front of the Borg or throwing them back in time to a point where humanity’s turn could have been for triumph or for ruin. Either way, humanity is tested to thrive.

Q is part of a large race of omnipotent beings called the Continuum that exist outside of space and time, with divine powers able to rewrite history or clear an entire galaxy of beings with a simple snap.

Similarities and Differences

The parallels between Trelane and Q are undeniable. Similarly,

• Both have the ability to alter reality at will.

• Both like to treat humans as toys or test subjects.

• In their interaction their actions have theatricality and humor in their interactions.

• They are in the habit of forcing the crew into moral or philosophical confrontation testing their actions.

The differences, however,

are telling a different story. Trelane imitates/mimics human history however, does not learn from it or take any lessons from those actions in history. Q on the other hand tests the morality and spirit behind those actions at the core of humanity’s understanding of that morality. Trelane has been overseen by his parents and often scolded by his immaturity and actions by his parents that seem to already have preconceptions of the beings he plays with. Q is often overseen by his fellow members of the Continuum, often scolding him for going too far or rewarding him for selfless acts which they do take notice.

The Conspiracies…

Even though on screen Trelane and Q were separate in their existence, through the extended universe of written books,

they both shared a linked existence. The late author, Peter David, wrote a novel in 1994 called “Q-Squared” where he had declared that Trelane was in fact a younger member of the Q Continuum. The story went on to reflect that Trelane as a juvenile Q was reckless and needed parental supervision in order to become a full member of the Q continuum, even speaking as if he was an earlier version of Q himself (John de Lancie). Even those not canon, this premise resonated across the Star Trek conspiracies for some time because of the very and true similarities.

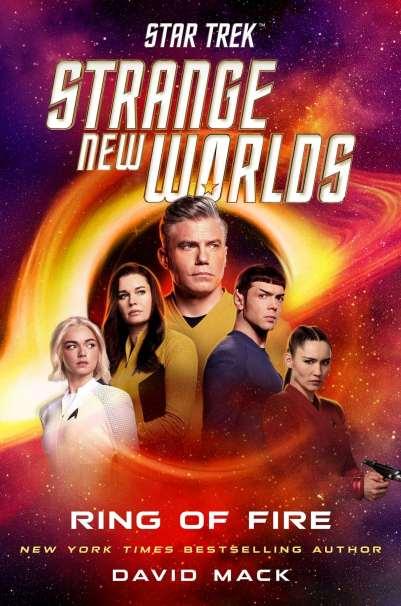

Only recently in Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, this conspiracy has been further deepened by one the recent episodes where it is theorized that Trelane and Q are in fact of the same beings just different in some way, like cousins or casts. The world in the episode happened to have lore tied

to the Q and also to Trelane’s family or race of beings as well. The omnipotent parent was voiced by none other than, (pause) John de Lancie! Unfortunately we won’t know for sure until the rest of the story plays out in this season.

What We Have Learned…

The contrast between the two are very close in both iterations. An omnipotent trickster that pushes, pulls, experiments and will bring things out of the individuals and make them test their own resolve and humanity. Trelane may seem young and immature without life experience to give them pause and hesitation. While Q presents experience and eagerness to see if expected results will change and exhibit the exception to the rule. Star Trek has always given us the idea that our past is what shaped our fu-

ture and our future will repeat the past if we do not understand it and change our way. In this aspect, Trelane shows us what we look like as curiosity unchecked and Q shows us what we look like as judgment personified. It further gets us to realize that we are not conquers, but always confronting ourselves to grow.

CHRISTIAN SAVAGE: Christian Savage loves volunteering for groups, especially when it comes to giving back to the communities. Life-long fan of science fiction and Star Trek series as a whole but also fan of Japanese Animation. With past experiences with show running and planning events, he strives to help those who need help and do what he can for community service and community outreach.

part is celebrating 59 years since Star Trek first aired, it seems only fitting to make mention of one of the great moments in franchise history. Much has been said and written about the Star Trek fan letter writing campaigns of the late 1960s to keep The Original Series (TOS) on the air. There were also the late 1960s-style demonstrations outside NBC. For those actions alone, Star Trek fans have been heralded as some of the most passionate of any fandom. However, while there was continuous writing campaigns orchestrated well into the 1980s by Star Trek fans, one that has stood out has been the naming of the first space shuttle in world history.

The announcement of the building of the space shuttle was made on Jan. 5, 1972. It was an announcement that stated there would be a ship that could go into

some renewed interest in a NASA program that was largely being ignored by the American public since 1969 after landing on the Moon.

NASA originally planned to name the shuttle Constitution to honor the nation’s foundational

1976. Once the announcement was made originally by Pres. Nixon, Star Trek fans began making inroads to have the new shuttle named Enterprise. As Star Trek conventions became more organized, petitions began being circulated. By 1976, the goal was to

the June 1976 issue of the fanzine, “A Piece of the Action,” fans were told that many people at NASA would like the name to be Enterprise. In that issue, general instructions were provided to the fandom on how to write the letter as well as where to address it. It is believed that Pres. Ford received hundreds of thousands of letters from Star Trek fans from around the world. As fate would have it, the president made the announcement to the world on Sept.

anniversary of Star Trek airing in the United States. President Ford contacted NASA and stated regarding giving the name of the space shuttle as Enterprise: “It is a distinguished name in American naval history, with a long tradition of courage and endurance. It is also a name familiar to millions of faithful followers of the science fiction television program Star Trek. To explore the frontiers of space, there is no better ship than the space shuttle, and no better

prise.

On Constitution Day, September 17, 1976, the cast of TOS with Gene Roddenberry (minus William Shatner) were there to see the Enterprise shown to the world. As the Enterprise rolled onto the tarmac, the United States Marching Band began playing the theme from TOS. This was a major coup for the fandom. They had influenced the President of the United States to name the first space shuttle in world history after the starship from Star Trek.

DAVID G. LOCONTO: David G. LoConto is a Professor of Sociology at New Mexico State University, specializing in collective identity, fandom and social movements. More importantly, he’s been a fan of Star Trek since Sept. 8, 1966 when he watched the first episode with his parents.

As a life-long Star Trek fan, starting with reruns of The Original Series, then becoming engaged with The Next Generation and continuing with Deep Space Nine and then Voyager, I have always felt a deep connection with the shows and always made it a must-see TV. To me, Star Trek has not only been about technology and advances in science but watched how humanity has grown from its petty differences and has learned to attempt to better themselves as a society. It is nearly impossible to claim just five episodes from over 50 years of television, I have put together a list of five that is, in my opinion, my personal favorites and the best. I realize that this list is debatable and some may not agree, but these are mine.

“The Doomsday Machine”: (Original Series Season 2 Episode 6)

“The Doomsday Machine” is one of those classic episodes that at its core has edge of your seat action. In addition, it has character conflict, moral consequences and Cold War allegory. This episode puts the Enterprise against a terrifying, planet-killing weapon of unknown origin; a mindless force of destruction that echoes the fears of nuclear annihilation that was heightened during the 1960s. What elevates this story isn’t just about the dangerous weapon of mass destruction but also about the human aspect, namely the mental breakdown of Commodore Matt Decker.

Commodore Decker played by William Windom, is a man broken by the weight of command and the loss of his crew. His descent into madness and obsession mirrors “Moby Dick’s” Captain Ahab, bringing a layer of psychological drama that contrasts sharply with Kirk’s steadiness and Spock’s logic. This episode explores the nature of PTSD; survivors guilt and the moral burden of leadership

The pacing is relentless, the stakes are high, and the music, some of the most iconic in TOS, drives the emotional tone with cinematic force. Of course, there’s Kirk’s classic last-second heroics, Spock’s unwavering logic and Scotty’s miracle work in the Jefferies tubes. It is everything you can ask for in a Star Trek episode

Ultimately, “The Doomsday Machine” endures because it doesn’t just entertain, it warns, reflects, and challenges. It’s a story about what happens when technology escapes reason, when grief overwhelms judgement, and when courage means knowing when not to fire. In short, it’s the essence of what made Star Trek so revolutionary, and why it still matters.

“Chain of Command”: The Next Generation Season 6 Episodes 10 & 11

“Chain of Command” is one of the best episodes of The Next Generation, it’s one of the most powerful and unflinching stories in this series. This two-parter strips away the polish of starships and diplomacy to

confront the brutal realities of authoritarianism, torture and the resilience of the human spirit. At its core is Capt. Picard becoming abducted and subjected to psychological and physical torment by a Cardassian interrogator played by David Warner. What makes their relationship so compelling is that it’s deeply personal but also symbolic. It reflects real world interrogation and propaganda tactics, where the goal isn’t just to extract facts, but to force the victim to believe a lie. Picard’s final moment, when he confesses to Troi that he was about to say there five lights, is a haunting reminder of how fragile even the strongest minds can become under sustained abuse.

The dynamic between Picard and Gul Madred explores the darker aspects of power, truth and human dignity. Stripped of his clothes, rank and all aspects of being a person, Picard becomes a prisoner in every sense, but it’s the battle for his mind that defines the relationship. Gul Madred isn’t just interested in information; he wants to break Picard. Through manipulation, humiliation and torture, Madred tries to reduce the captain to a complaint shell, repeatedly demanding that Picard deny the truth and declare there are five lights when he knows there are only four. The more Madred tries to dehumanize him, the more Picard’s inner strength becomes evident. Patrick Stewart’s performance is quietly devastating, showing a man pushed to the brink but never quite surrendering who he is

Meanwhile, Enterprise has a shift in command when Ronny Cox stars as Captain Jelico. This creates an uncomfortable power dynamic between Riker and Jellico. With Picard removed from command and Jellico taking over, the story doesn’t just shift its focus to a high-stakes diplomatic mission, it also explores what happens when incompatible leadership styles can cause friction. Jellico, a no-nonsense, by the book officer, spends no time rearranging the command structure to a more rigid tone in vast contrast to the trust-based structure under Picard.

What makes this dynamic so effective is that both men are, in their own ways, right. Jellico does get results; he manages to outmaneuver the Cardassions and save Picard’s life, but not without alienating those under his command. Riker, for all his defiance, ultimately steps up and delivers when it

matters most, proving that competence and loyalty don’t always need to come in the same package. Their uneasy truce by the end doesn’t resolve their differences, it respects them. It is that complexity that makes “Chain of Command” so enduring. The episode doesn’t offer easy answers about leadership, instead it challenges us to think critically about command, respect, and what happens when values clash under pressure.

“Trials and Tribble-ations" Deep Space Nine (Season 6 Episode 5)

I am a sucker for crossover episodes, and this episode does not disappoint. “Trials and Tribble-ations” is a perfect blend of humor, nostalgia, and technical brilliance. It manages to be a love letter to the Original Series and celebrates how far Trek has come by the time Deep Space Nine comes around. When Sisko and crew are flung back in time and end up walking into the episode “Trouble with Tribbles” episode of The Original Series. The use of visual effects in this episode are truly remarkable being able to have Sisko and team interact with original cast members.

This episode incorporates great interaction and humor. The banter between Miles and Bashir, not knowing how to use the turbolift, the interaction with O’Brien and Kirk after the fight is seamless. Both Colm Meany and Alexander Siddig say they got guidance from Walter Koenig on how to interact with set pieces and Worf’s explanation as to why the Klingons look different between Kirk’s time and DS9 was halfhearted humor if not extremely vague.

"Trials and Tribble-ations" really does an excellent job in paying homage to the past while highlighting DS9’s own identity. It is a timeless tribute to what Star Trek stands for. Even though this episode was more so a filler episode I believe that is qualified as one of the best of this series.

“Blink of an Eye” Voyager (Season 6 Episode 12)