Betting the Ranch on Crypto

The digital asset industry finds a new home...Wyoming?

BY WHITNEY CURRY WIMBISH

TAP NEEDS CHAMPIONS

Join the Prospect Legacy Society

The American Prospect needs champions who believe in an optimistic future for America and the world, and in TAP’s mission to connect progressive policy with viable majority politics.

You can provide enduring financial support in the form of bequests, stock donations, retirement account distributions and other instruments, many with immediate tax benefits.

Is this right for you? To learn more about ways to share your wealth with The American Prospect, check out Prospect.org/LegacySociety

Your support will help us make a difference long into the future

Features

12 Down and Out on the Crypto Frontier

In Wyoming, the Delaware of cryptocurrency, industry players celebrated their fortunes and said everyone will benefit. But workers haven’t seen it.

By Whitney Curry Wimbish

20 This Greenland Is Red

The small island nation has one of the largest and most successful portfolios of state-owned companies in the world. What? By Ryan Cooper

26 Can Resistance Succeed?

The more authoritarian Trump becomes, the more he provokes effective opposition. By Robert Kuttner

36 Big Banks Behaving Badly

Decades of consolidation have made large financial institutions the primary partners for small businesses. Two case studies show how this can go awry.

By David Dayen

45 A Beacon of Progress

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu’s first-term achievements shine, but numerous challenges persist after her re-election. By Naomi Bethune

I love to travel,

and I love to talk to people about travel. There’s something about being somewhere new, and something about giving others the impression of what it was like, that’s intoxicating to me. Maybe that’s why I’m a journalist: It’s a way to put people into another reality, to have them see through the eyes of the people we report on. I’ve never been to a couple of the places profiled in our latest issue, but I’m grateful that we had some great reporters to help me understand them.

Whitney Wimbish was on-site at the Wyoming Blockchain Symposium. It’s the story of a conference featuring the leading lights of the crypto industry, and how Wyoming, the least populous state in the country, is trying to leverage digital assets to drive its fiscal future. But because it’s Whitney, the piece is something more than that. It’s also about the disconnect between the elites who flew their private jets into the luxury resort of Jackson Hole, and the workers whose job it is to wait on them and serve them, who don’t earn enough money for that toil even to live in the same state or maintain a decent quality of life. And none of them think of crypto as their financial savior.

Then we crossed the Atlantic with Ryan Cooper, our roving reporter of all things Nordic. Ryan has written from the Faroe Islands, Finland, and now Greenland, the apple of Donald Trump’s eye. Trump may not like it so much if he picks up this issue and reads that this autonomous territory of Denmark is one of the biggest practitioners of public ownership in the world, with the government owning businesses that account for more than half of Greenland’s total gross domestic product. But again, Ryan didn’t stop there. You’ll also get a history lesson and an appreciation for Greenland’s natural, if unforgiving, beauty, along with an economic lesson about Nordic cooperation, state capacity, and triumph over long odds.

And our newest writing fellow Naomi Bethune, a native Bostonian, returns to her hometown to check in on the success of a progressive mayor, Michelle Wu, as she cruises to re-election. I didn’t only read about the issues facing Boston, but also the historical challenges of an Asian American woman leading a city where politics has traditionally been confined to back-slapping Irish and Italian pols.

Not every story needs detailed geography, of course. Bob Kuttner in this issue offers a nationwide tour of the resistance to Donald Trump, from coast to coast, emerging with an ultimately hopeful story of people from all walks of life organizing with common purpose. And my story is about the landscape for small-business owners, who used to have a local banker that they knew and could turn to for help, but who now must deal with giant financial institutions that aren’t as committed to their survival.

The best writing, whether tied to place or not, puts you in someone else’s head so you understand their motivations, the forces they’re up against, and the ways they can prevail. I think these stories offer excellent examples of that. –David Dayen

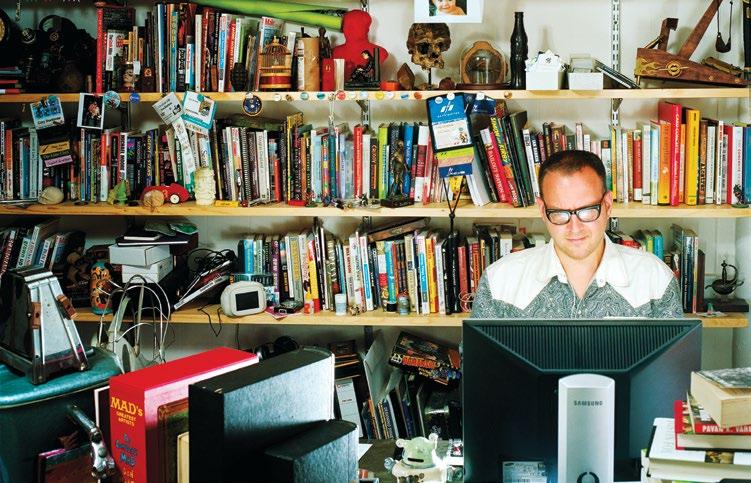

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITORS GABRIELLE GURLEY, RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

MANAGING EDITOR AND DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL OPERATIONS

CAITLIN PENZEYMOOG

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

STAFF WRITER WHITNEY WIMBISH

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

WRITING FELLOWS EMMA JANSSEN, JAMES BARATTA, NAOMI BETHUNE

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS BRANDON MALAVE, CHARLIE MCGILL, EYCES TUBBS, ELLA TUMMEL

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, JULIAN ZELIZER

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER MAX HORTEN ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR LAUREN PFEIL

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAN CANTOR, DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, ELI LUBEROFF, LINDSAY OWENS, MILES RAPOPORT, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/ MEMBERSHIP

REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

VOL. 36, NO. 5. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2025 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Thank You, Reader, for Your Support!

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

PROSPEC TS

HAROLD MEYERSON

Class Matters

Sixty years ago, the leaders of the civil rights movement faced an unavoidable question: What now? In successive summers, Congress had enacted the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. The South’s de jure segregation and denial of Black citizenship were no more; the battle for equality before the law appeared to be settled. The battle for social and economic equality, however, was only just beginning.

Even before the legislative triumphs, the instigators, organizers, and leaders of the 1963 March on Washington understood that their fight had to become a much broader social revolution. On the day after the march, they convened a conference to discuss what they could do to make that happen. The conference was sponsored by the Socialist Party, which, despite its minuscule membership, contained within its ranks the instigators and organizers of the march.

The keynote speakers at the conference were the instigator, the venerable socialist A. Philip Randolph, and the organizer, Randolph’s deputy Bayard Rustin. Randolph’s socialist activism dated back to the 1910s, when his newspaper urged Blacks to oppose U.S. participation in World War I. In the 1930s, as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, he astounded and alarmed business leaders and delighted Black Americans when his union won recognition and a contract from the reactionary Pullman Company. In the early 1940s, with war looming, his threat of a march on then-segregated Washington, D.C. (which 100,000 Blacks had pledged to join) compelled President Roosevelt to meet Randolph’s demand for a ban on racial discrimination in defense plants. In 1948, a similar Randolph threat compelled Presi-

dent Truman to order the desegregation of the armed forces.

In late 1962, Randolph and Rustin proposed a march for the following year—the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation—centered on job creation. The Emancipation March for Jobs set a bold vision, that the civil rights struggles of Blacks “may now be the catalyst which mobilizes all workers behind the demands for a broad and fundamental program for economic justice.” But in the early spring of 1963, the nonviolent campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama, led by Martin Luther King Jr., was met by a violent response from the Birmingham police, who set dogs, nightsticks, and fire hoses on children and adults, all captured on television newscasts. The ensuing uproar compelled President Kennedy to call on Congress to enact a civil rights law requiring the desegregation of private and public facilities. Randolph and Rustin added that demand—and successfully urged that the legislation also include a section requiring a ban on discrimination in employment—to their march’s agenda, which they renamed the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

The march, organized by Rustin, was of course a historic success, climaxing in King’s address, and providing major momentum to enact the civil rights legislation of the next two years.

At the Socialist Party’s follow-up conference, Randolph laid out his ideas for the future. Pointing out that white sharecroppers had civil rights but lived in abject poverty, he said, “We must liberate not only ourselves but our white brothers and sisters.” Rustin followed by declaring a need for economic planning that would deal with

the technological unemployment he saw coming in the auto and steel plants that employed large numbers of Black men. By 1965, after the enactment of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, Randolph, Rustin, and King turned even more forcefully to the economic policies they saw as imperative if Blacks were ever to achieve social as well as legal equality. They believed Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, while good as far as it went, fell lamentably short of remedying the inequality hardwired into the economy. Their advocacy steered clear of programs specifically directed to help Blacks and other racial minorities, focusing instead on huge economic reforms that would, in Kennedy’s famous phrase, lift all boats.

They had ample reason to think that a white backlash would follow policies aimed only at helping racial minorities, and not just in the South. In the 1964 Democratic presidential primaries (which were held in only a handful of states), Alabama Gov. George Wallace, the nation’s foremost champion of segregation and virulent racism, took 34 percent of the vote in Wisconsin and 30 percent in Indiana.

The new civil rights laws did nothing, and the War on Poverty programs precious little, to alleviate the pervasive poverty, ghettoization, and systemic police abuse of Blacks in Northern cities. The 1965 Watts Riots made clear that those ghettos were powder kegs that needed only one more police outrage to explode. So later that year, Randolph announced that he’d “call upon the leaders of the Freedom Movement to meet together with economists and social scientists to work out a ‘Freedom Budget’” that spelled out how the nation could achieve de facto —not just de jure—equality.

Randolph, Rustin, and King, standardbearers of this Freedom Movement, were all avowed democratic socialists. Chief among the academic and union economists who worked with them on developing the budget was Leon Keyserling. As an attorney and economist on the staff of New York Sen. Robert Wagner in the 1930s, Keyserling had actually written most of the text of both the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act. In the following years, he’d held multiple posts in both the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, arguing for planned full employment and higher minimum wages. (His advocacy led Truman and the Congress to

enact what is still the greatest percentage increase in the federal minimum wage.)

When the Freedom Budget was released in late 1966, it called for planned full employment, income provision for those who couldn’t be employed, universal medical care, higher minimum wages, new housing to replace the nation’s 9.3 million “seriously deficient housing units,” the eradication of air and water pollution, and preservation of the nation’s natural resources, among other social necessities. It was Keyserling’s achievement that it did so without running a deficit or raising tax rates. By mandating a high level of production and planned full employment, the budget penciled out so that revenues coming in to the government would grow to provide an additional $185 billion over the next ten years that could fund its proposals, without diminishing the billions needed to fund other government activities. Full employment was the key, boosting the number of taxpayers, the level of their wages, and the government’s revenues.

We need to recall that in 1966, the highest marginal federal income tax rate was 70 percent (today, it’s 37 percent); the federal corporate tax rate was 53 percent (it’s 21 percent today); and the rate of private-sector unionization was 30 percent (it’s 6 percent today). Keyserling’s numbers were based on the more egalitarian income and tax rates in place when he wrote.

To say that the odds against the Freedom Budget’s adoption were steep is an understatement. It presupposed that the burst of liberal legislation that came out of the overwhelmingly Democratic Congress of 1965 would continue, yet the Democratic majorities were quickly diminished in the 1966 midterms. The budget also failed to account for the growing spending on the Vietnam War— and by ignoring the moral as well as financial costs of the war, it failed to reach out to and interest its most natural constituency—liberal and left-liberal anti-war activists. With the election of Richard Nixon in 1968, hopes for any of the budget being even partly enacted abruptly ended. When Jimmy Carter recaptured the White House for the Democrats in 1976, alongside a lopsidedly Democratic Congress, a movement for full employment emerged. It was backed by the more progressive unions, embodied legislatively in the Humphrey-Hawkins bill setting full employment targets for the government, and led intellectually by socialist Michael Harrington, who argued in print

and on podiums that planned full employment was the only way to create the kind of broad economic security necessary for the public to support a comprehensive progressive agenda. (Harrington explained how planned full employment in the Nordic social democracies gave those nations the political space to enact other progressive policies—feminist, environmental, and so on.) Harrington also assembled a coalition of unions and newer social movements in support of both Humphrey-Hawkins and the broader cause.

Carter and centrist Democrats in the Congress so watered down HumphreyHawkins, however, that the enacted version made no real impact on the nation’s economy. Still, as late as the 1992 Democratic presidential primaries, before neoliberalism had captured not just the Republicans but most of the Democratic Party as well, candidate Bill Clinton would occasionally refer to Sweden’s full employment policies as something the U.S. would do well to emulate.

What remains clear nearly 60 years after the Freedom Budget is the conviction of its authors—Randolph wrote its introduction, King wrote its foreword, and Rustin supervised its production—that the only real way to produce a social revolution for America’s Blacks was to produce a social revolution for all Americans. The Black nationalism, Black separatism, and Black capitalism that also began to surge once the government had struck down de jure segregation, they believed, wouldn’t and couldn’t change the contours of the nation’s economy in a way that could alleviate Black poverty. In a speech Rustin delivered shortly after the budget was unveiled, at a time when both Black nationalism and white backlash were on the rise, he said that any viable strategy had to be addressed “equally to Negro frustration and white fear.”

The Urban League’s Whitney Young eagerly endorsed the Freedom Budget, but he also backed a policy that stood in stark contrast to the budget’s universalism. He argued that the government should set quotas for hiring and advancing Blacks in public- and private-sector jobs, and in colleges and unions. An attenuated version of that proposal became a key part of various affirmative action programs, and over the years won considerable support from the one sector of white society with which the Urban League interacted most: corporate

elites, who could admit Blacks and other minorities to their ranks without the kind of reversals to power relationships (and, despite Keyserling’s calculations, higher taxes) to which the Freedom Budget could lead. To be sure, Young and his successors still favored many of the social programs spelled out in the budget and subsequent progressive legislation, just as the successors to Randolph and Rustin were to support affirmative action in the absence of the kind of sweeping changes their budget called for.

But today, as Idrees Kahloon recently documented in The New Yorker, the past half-century of affirmative action and DEI have failed to move the needle in reducing the still vast gap between Black and white wealth and income. Politically, such policies were in retreat well before Donald Trump attained and then regained state power. Kahloon argues that the sole remaining path forward to reduce our soaring economic and social inequality is the kind of class-based universalism embodied in the long-forgotten Freedom Budget. I’d add that the downward mobility of the American working class in recent decades makes such universalism more politically plausible than it was in 1966. The class-based universalistic politics of the socialists of the 1960s and ’70s hold important lessons for the socialists of 2025. One socialist who understands those lessons in his very bones is New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, whose affordability agenda steers clear of a multitude of more particularist agendas—some very worthy, some less so—in favor of policies directed at the broadest possible population of poor and working-class, middle-class, and even upper-middle-class New Yorkers. While New York city government has no real power over levels of employment, much less full employment, it does have power over municipal provision of such services as child care and rent controls.

At a time when nationalism, xenophobia, and racism are all around us, socialism certainly should be universalistic. As it happens, class-based universalism is also the most pragmatic course for progressive initiatives in America today. That Democrats of all tendencies have embraced varieties of affordability platforms illustrates the appeal of sharply drawn but universally targeted economic policies. In his class-based, universal, and very pragmatic socialism, Mamdani is the proper heir to Randolph, Rustin, and King. n

NOTEBOOK

FEMA’s Years of Living Dangerously

The Trump administration’s determination to force states to shoulder disaster funding burdens guarantees more deaths and destruction.

By Gabrielle Gurley

The federal government had come a long way from the heckuva-job-Brownie days of George W. Bush and Michael Brown, the unqualified head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) who mangled the Hurricane Katrina disaster response in New Orleans and on the Gulf Coast.

Yet 20 years and another unqualified FEMA leader later, despite reforms intended to guard against future agency heads joking (or not) about the hurricane season, America’s disaster response has devolved into something more akin to the pre-FEMA era’s improvisions. After two decades of major disasters in the 1960s and ’70s like the Hilo, Hawaii, tsunami, the Alaska earthquake (the worst in American history), and major hurricanes including Agnes, the National Governors Association called for a reorganization of the country’s decentralized emergency preparedness and disaster response systems in 1977. FEMA debuted two years later.

The Trump administration’s zeal to stamp out a flawed but essential agency has been interrupted by the mind-numbing display of bureaucratic micromanaging: the federal response to the Central Texas flash floods in July that killed 135 people, among them children vacationing in summer camps. “As sad as that is, unfortunately, that is typically what moves the needle in terms of disaster policy throughout history,” says Jeff Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. “It’s not the data forecasting what’s going to happen. It’s the lives lost when it does happen—and this happened in a red state.”

The requirement that Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem sign off on agency expenses above $100,000 compromised FEMA disaster hotline availability and search and rescue missions so severely

that FEMA’s head of urban search and rescue resigned in frustration.

None of those facts made it into an August DHS press release that offered an upbeat, wholly unsubstantiated perspective on the agency, declaring that after 200 days, “FEMA is 100% faster in getting bootson-the-ground to respond to disasters.” Nim Kidd, the head of the Texas Division of Emergency Management, claimed, “I’ve been doing this for more than 30 years, and I can say with confidence that this was the fastest and most effective federal support Texas has ever received.”

Earlier this year, President Trump signed an executive order that “empowers State, local, and individual preparedness and injects common sense into infrastructure prioritization and strategic investments through risk-informed decisions that make our infrastructure, communities, and economy resilient to global and dynamic threats and hazards.” An administration “review council” will consider what comes next for the emasculated agency, with a final report due in November.

But common sense isn’t so common. Only the federal government can come up with the billions of dollars and assets to backstop the 50 states, local governments, territories, and tribal lands in the direst catastrophes. In an era when storms and wildfires are more frequent, stronger, and more expensive to respond to and recover from, shifting more of that burden onto states and localities after a jumble of executive orders, layoffs, firings, and delaying or withholding funds displays an obsession with cost-cutting by any means necessary and no concern with the ability of states to deal with catastrophes.

One long-held fallacy that cratered FEMA’s public image is the misguided belief that the federal government parachutes in with fists full of dollars to backstop local efforts as soon as the rains end or the last embers

flicker out. It’s led to “Where’s FEMA?” outbursts by angry, despondent survivors who aren’t aware of officials scrambling, or have been taken in by mis/disinformation that compounds their agonies.

After a disaster, local and state officials are the first ones on the ground in many cases, not FEMA . The amount of financial assistance that a community might receive depends on the scope of devastation. A small storm or fire that affects few properties, with no loss of life, particularly in areas that are susceptible to severe storms and wildfires, is usually handled by municipalities and states.

Even broader damage might still not reach the federal threshold for a disaster declaration. The federal government has been selective in how it responds. The National Emergency Management Association reports that in fiscal year 2023 there were nearly 25,000 disasters in the United States; of those, only 60 received a federal disaster declaration.

Under the 1988 Stafford Act, the president approves major disaster declarations for cataclysmic situations that are beyond the capabilities of local and state officials, and emergency declarations for smaller upheavals where federal assistance can help stave off more serious consequences.

“The issue that it often comes down to is who is going to pay for those resources?” says Samantha Montano, a Massachusetts Maritime Academy associate professor of emergency management. “That’s why that declaration is so important, because it comes with money.”

FEMA has historically paid most of the costs for major disasters. Urging states to improve how they gear up for seasonal upheavals like tornadoes, hurricanes, and wildfires is not new. Having states budget for disasters as they might for education or health care has had support from Demo -

crats and Republicans. One such proposal, a state disaster deductible proposed by Craig Fugate, the FEMA administrator during the Obama years, evaporated under the first Trump administration.

But swerving from dependence on Washington after a catastrophe to deep budget cuts and homegrown self-reliance in just a few months produced the horror show that played out on the ground in Texas Hill Country.

President Biden signed a major disaster declaration for North Carolina after Tropical Storm Helene on September 28, 2024. The day before, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont (D) approved the deployment of an eightmember volunteer urban search and rescue team to assist local officials in western North Carolina under the auspices of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact

(EMAC). The mayor of Norwalk agreed to send a volunteer from the city’s fire department, a hazmat command and communications unit, along with a fire department utility truck and an ATV for the mission.

EMAC, a national mutual aid framework overseen by the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA), provides disaster relief in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana

Only the federal government can come up with billions of dollars in the direst catastrophes.

Islands, with people and equipment, but not funding. States providing assistance can seek reimbursement or send aid at no cost to a receiving state; but that is not linked to a state’s request for a federal declaration or funding. Connecticut and the other New England states also have reciprocal disaster assistance relationships with Canada’s eastern provinces through the International Emergency Management Assistance Compact.

With fewer natural disasters, Connecticut sends more assistance than it receives.

“When we put in a bid to help another state, we up front say this is what it’s going to cost, so we know what resources are going to get reimbursed if we send them,” says William Turner, the state’s emergency management director. “[EMAC] is really the mechanism that allows all of us to respond and recover before we have to get FEMA pulled in.

The flash floods in Texas Hill Country killed 135 people this summer.

We’ve got that piece pretty well figured out. We just need to understand where FEMA is going to end up when the dust settles.”

EMAC isn’t safe from a disintegrating FEMA . The mutual aid system runs exclusively on National Incident Management System funding provided through DHS and FEMA . However, in early September, FEMA failed to sign off on EMAC’s annual $2 million grant. Lynn Budd, NEMA’s president, told the national news outlet NOTUS that the episode “certainly flies in the face of the idea that states need to take on more responsibility.” The system finally received its monies, but this snafu raises critical questions about how EMAC can remain effective and navigate the volatile federal environment.

“ EMAC works well, as long as there is trust and security among the states that there is going to be funding to pay for those resources,” Montano says. “Once you lose assurance that there is going to be funding for those resources, that can break apart very quickly, not because other states don’t want to help each other, but because the funding isn’t there to do it.”

Before Helene, North Carolina was fairly well off, with a healthy $5 billion in its reserve fund for disasters. Today, about $1 billion has gone to disaster relief, with that account now down to about $3.5 billion. State officials have estimated the total cost of Helene at $60 billion. The proposed state budget for fiscal year 2026 is nearly $34 billion. FEMA has reimbursed about $1 billion.

Trying to work around bureaucratic inertia can backfire. Henderson County in western North Carolina decided not to wait for FEMA funds for debris removal and spent $20 million up front, thinking that the federal payout would be speedier. Across the border, Tennessee took another tack, setting up a Helene Emergency Assistance Loan Program. The $100 million loan fund provides no-interest loans to eligible counties for hauling debris, as well as water and wastewater infrastructure repairs.

Even wealthy states that see frequent natural disasters don’t have the fiscal wherewithal to absorb the multibillions of a major catastrophe. Florida relies heavily on the federal government for response assistance and dollars. In the wildfire sector, California and Washington have devised budgetary formulas based on past disaster costs to allocate funds to disaster accounts. Montana moves a portion of excess general funds once every two years into a wildfire

In New Orleans, local residents have stepped into the city’s disaster preparedness void.

suppression fund. But though those steps have to be taken, particularly now, they don’t deliver enough money.

For some states, moving from “what if” to the “when” in state disaster budgeting is a radical paradigm shift. Historically lessprepared states have had to step up recovery and resilience programs. After several years of federal disaster declarations, an extreme rainfall event in 2015, and Hurricanes Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018, South Carolina created an office of resilience. Focusing on coastal and riverine areas, the state encourages strategies to manage waterways and mitigate flooding across communities, recognizing that if a downstream area has strong building codes, storm plans, and public awareness of risks, those efforts may not matter much if an upstream town doesn’t make comparable investments.

Being proactive is critical, says Peter Muller of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Managing Fiscal Risks project. “They’re trying to put money aside for costs they know they’re going to have, officially, before it happens, so that you don’t have to go and suddenly scramble and pull money from other priorities when a disaster does happen.”

Local residents also have stepped in to fill disaster preparedness gaps. Imagine Water Works, a New Orleans climate and disaster relief group, set up community power stations in neighborhoods after Hurricane Zeta in 2020, when three hurricanes and two tropical storms hit the state, the most in any calendar year. Residents were able to charge devices at homes and businesses that still had or regained power.

With the pandemic raging, residents were also able to pick up hand sanitizer, masks, and other COVID -19 supplies. The group asked fire stations to host charging stations and help people get oxygen for medical devices. They reached out to the city again the following year, and by the third year New Orleans officials began to duplicate their efforts. Fire stations also offer cooling facilities now.

With a robust network of indigenous and LGBTQ people, the group also has locations in Houma and southwest Louisiana as well as other local groups across the Deep South. “My relationship is very good with government. Folks who work in that space will contact me directly and ask for help spreading messages to folks, and we have a large social media presence, and we’re trusted,” says Klie Kliebert, the group’s executive director.

To mark the Katrina anniversary, a group of past and present FEMA employees demanded that Congress wake up to the threat posed by dumping the agency leadership reforms that came out of the 2005 debacle. Some employees were suspended. Restoring FEMA’s independence has support in Congress, but saving FEMA , much less any of the dozens of vital agencies that have been rocketed into oblivion by the Trump administration, hasn’t prioritized faster action. President Trump’s assault on disaster assistance has had one unifying effect, ginning up varying degrees of outrage and disbelief from every corner of the country. In the short term at least, there’s been the faintest glimmer of off-camera comity between Texas and California, two of the most disaster-prone states in the country, despite the cold civil war over redistricting: In mid-July, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) sent a three-member human remains detection team to Texas, which boosted urban search and rescue personnel in Texas to 42 people.

Twenty states have sued FEMA and DHS to restore funding that had already been allocated under incentivized mitigation programs like Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC), enacted under the first Trump administration. This second time around, FEMA canceled BRIC. A federal judge ordered the White House to halt any reallocation of $4 billion in BRIC funds.

2025 has been a quiet season on the hurricane front—so far. Escaping the threat posed by Hurricane Erin, which steered off into the open Atlantic away from coasts, appears to have dampened any urgency in Washington surrounding this mess. What happens next will signal whether the states can hang together and demand an end to whims disguised as policy or whether federalism is as moribund as the rest of America’s democratic systems. It may take another massive calamity to field-test that proposition. n

Supermarket Shaping

Critics say Zohran Mamdani’s public grocery store proposal will never work. But Mamdani’s idea isn’t the problem—market consolidation is.

By Emma Janssen

One of the more intriguing kitchen-table economic proposals from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani is a pilot program for five city-owned grocery stores. Like his other ideas in his platform (free buses, rent freezes), public groceries aren’t a new invention. But New York City would be the largest municipality to test

them, and all eyes would be watching to see if they succeed.

The logic behind city-run grocery stores is simple. Privately owned grocery stores have to turn a profit, so they mark up their goods. City services don’t need to make a profit. So a city-run grocery store could sell goods at lower prices.

Perhaps more importantly, public groceries can prevent food deserts, which the USDA

defines as any low-income community ten miles or more from the nearest grocer (in cities, it’s one mile). Both rural and urban food deserts have seen independent grocers gutted while giants like Walmart, Kroger, and Aldi rise. Public grocers can bring fresh food options to communities that corporate groceries don’t consider profitable.

Several cities are testing the public grocery model, from Madison, Wisconsin, to Kansas City, Missouri . But many of the examples are in rural areas, and often in red states. Food deserts proliferate in rural America, and small-town governments are more flexible than the 306,000-person city government of New York City. They can innovate without wading into a multiyear bureaucratic process first, like in Chicago, which floated the idea of a public market but hasn’t yet followed through on it.

Take Little River, Kansas, a town of 472 people. There had always been a grocery store in this community; whenever one owner retired, they passed the responsibility on to someone else. But in the 2010s, the Nelsons, who owned and operated the store, started to feel the financial stress of maintaining decades-old freezers and refrigerators. The city bought the building and took responsibility for maintenance costs. When the Nelsons retire, the city will just need to find new operators, keeping the town fed. At least three other Kansas towns—Erie, Caney, and St. Paul—have public groceries as well.

Not all public groceries have succeeded; the Kansas City store had chronically empty shelves before closing this August. That has much to do with the inability of groceries with small inventory needs to win the same deals from suppliers as the industry’s giants. A law that made special pricing for big chain stores illegal nearly a century ago has been barely enforced in recent decades. But adding New York City’s muscle to demand fair treatment for noncorporate grocers could change the game.

Different Models

Some municipalities have experimented with entirely publicly owned and operated models, while other stores are coops or nonprofits. Sean Park, a program manager at Western Illinois University who works with independent grocers, sees the municipally owned, privately operated model (like Little River’s) as one of the most promising. At their best, these pub -

New York City would have the resources to fight for fair treatment from suppliers for public groceries.

lic-private partnerships take the administrative support of a city and combine it with the fast-moving entrepreneurship of a business owner. The model also sidesteps the need for cities to learn how to become grocery store operators.

Cities often take a role in real estate, constructing and leasing the grocery building to its operator. Cities can also provide the initial funding needed to get off the ground and lower the rent for the first few crucial years. From the operator’s perspective, Park explained, having the city available to absorb the shock of those early costs can make all the difference. Cities also win: When issuing a bid for an operator, they can choose what to prioritize, whether it be years of experience or entrepreneurial creativity.

Most important, the city gains certainty, said Park. “That community can never lose the grocery store. They can lose the operator. But so often, with Walmarts and Dollar Generals, when they close up their stores … [they] just sit there in probate as an eyesore.”

A municipal grocery with private operators creates an opening for a local smallbusiness owner to invest and grow in the community. An entrepreneurial model can broaden the appeal, particularly for those on the right who might balk at the idea of government entering the grocery business.

Rial Carver, the program director of the Rural Grocery Initiative at Kansas State University, suggested that local governments tend to be better suited as grocery store funders or landlords rather than operators. “It can really be the best of both worlds,” she said. “You’re able to leverage partners and also leverage interest in this concept of having access to healthy food, but also not forcing anyone out of their comfort zone.”

Atlanta recently announced a publicprivate partnership with Savi Provisions, a small chain of community markets that is already established in the area. The city’s development agency will award Savi Provisions $8.2 million to build two stores in neighborhoods that had been left behind by other grocers. Savi Provisions CEO Paul Nair said that they hope to keep costs comparable to Kroger, even if that means that they won’t be making a significant profit.

Disadvantaged Independents

Park is skeptical that a grocery store both owned and operated by a city would be suc -

cessful, due to the bureaucratic nature of city governments. “Because it’s such a tight margin, any addition of bureaucracy or cost is just not going to be profitable,” he said. If purchasing decisions must go through multiple levels of city approval, stores could miss out on attractive options and struggle with management.

Carver also questioned a city-owned and -operated grocery. “I think that the traditional municipal grocery model [where the city owns and operates the store] is a little less known, less established, so I think that a local government would really want to do their due diligence … before stepping in,” she said.

Criticism of Mamdani’s proposal has typically fallen along those lines. But that argument misidentifies the real issue. It’s not that all public grocery stores are inherently doomed to fail, but that the grocery industry is structured against all independent grocers, whether they’re public or not. The grocery industry experts I spoke to identi-

fied market consolidation as likely the biggest issue facing independent grocers today.

“Walmart specifically precipitated this big change in grocery competition,” explained Claire Kelloway, the food program manager at the Open Markets Institute. She accused Walmart of “bullying, bludgeoning, ruthlessly negotiating with suppliers, because they have access to this market that is so big, and suppliers really can’t afford to not be on Walmart’s shelves.”

To ensure they get on those shelves, distributors will often give massive discounts to Walmart and other large grocers. Those discounts get passed along to customers, which is why it’s practically always cheaper to shop at Walmart than your local momand-pop market. While I love the tiny grocery store on my street in Chicago that sells locally grown produce, for example, it’s much more economical for me to bike to the huge Jewel-Osco, a chain owned by Albertsons, in the next neighborhood over.

Independents struggle to work with dis-

Zohran Mamdani has proposed a pilot program of five cityowned grocery stores.

tributors that deliver goods to stores, said Carver. “In a rural area … sometimes it’s hard to get a wholesale supplier to even service your store,” she said, because it’s so far from their base. In urban areas, a wholesaler might see a small grocery as not worth their time. Even if independents can source goods, the price could be steep.

A look at a grocery funding initiative in Illinois, the Fresh Food Fund, shows how hard it is to get small grocers off the ground, even with robust government support. A 2024 ProPublica and Capitol News Illinois investigation found that only two grocery stores out of the original six announced in 2018 had survived. Community members said cost was the biggest reason they chose stores like Walmart over a local independent store in Cairo, Illinois. Even if the community is excited about having an independent store close by, low-income residents may prefer to travel farther for groceries if it means they can buy at the lowest price.

But there is a law already on the books that experts say could transform the grocery industry by leveling the playing field for small stores. It just hasn’t been enforced.

Rise and Fall of an Anti-Monopoly Law

The Robinson-Patman Act, passed in 1936, required all distributors to offer the same pricing on their goods, regardless of the size of the retailer. It was designed to thwart the market power of A&P, the nation’s first and biggest chain grocery.

Once it was passed, Robinson-Patman did significantly level the playing field. But in the 1970s and 1980s, the ideological tides shifted, and the law fell out of favor. Government enforcement all but stopped, precipitating the rise of Walmart and today’s biggest grocers. Today, Walmart is responsible for some 50 percent of all groceries sold in hundreds of regions throughout the country.

Stacy Mitchell, co-executive director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR),

argues that the rise of food deserts is almost entirely caused by the lack of RobinsonPatman enforcement. In a 2024 article for The Atlantic , she takes the case of Deanwood, a low-income, majority-Black neighborhood of Washington, D.C. In the 1960s, Deanwood had numerous grocery stores, including some independent businesses and co-ops. By the 1990s, there were only two left, and now there are none. That change tracks the timeline of the rise and fall of Robinson-Patman enforcement.

During the Biden administration, antimonopoly advocates looked to revive Robinson-Patman. Alvaro Bedoya, a former commissioner on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Lina Khan, the FTC ’s former chair, championed the law and the need to fight price discrimination against small retailers. During Khan’s tenure, the FTC filed two Robinson-Patman suits: the first against Southern Glazer’s Wine and Spirits in December 2024, and the second against PepsiCo in January 2025.

“It would have a massive impact on the grocery industry,” Carver said of a return to enforcement.

But Donald Trump’s election spelled doom for reinvigorating Robinson-Patman. In May, the FTC dismissed the case against PepsiCo, arguing that the case was a “ legally dubious partisan stunt ,” in the words of current chair Andrew Ferguson. The FTC failed to release further details from the heavily redacted case materials. The suit alleged that PepsiCo gave one big-box retailer better prices, disadvantaging their competitors—but the name of that retailer was never revealed, along with several crucial details (reporting suggests the retailer is Walmart).

Typically, Mitchell explained, those redactions would be lifted within weeks or months of the case’s filing, but that never happened with the Pepsi case. So in August, ILSR asked a judge to disclose the details to see whether or not it really is just a “partisan stunt.” In response to Ferguson’s comments, Mitchell said: “If it was so baseless, then why not just let the complaint out into the public realm?”

murky. It’s not yet clear if his proposed grocery stores would be 100 percent publicly owned and operated, or if the city would partner with private operators. But we do know that the pilot program would begin with five stores, using city-owned land and exempted from rent and property taxes. That, and the lack of needing to turn a profit, could hold down costs a bit.

But big-box stores’ ability to secure wholesale products at much lower prices makes it hard for public groceries to compete. “I don’t think companies are sweating it too much yet,” says Kelloway, who adds that Robinson-Patman enforcement is the key. “It’s going to take someone just trying, and bringing [a] case, and we are seeing some of that happen.”

The FTC ’s case against Southern Glazer’s still stands. In addition, a number of Biden-era FTC officials have taken roles in private law firms that have a strong antitrust focus, Kelloway noted. Robinson-Patman includes a “private right of action,” which means that independent grocery stores or municipalities can file suit over price discrimination.

The problem, of course, is that most independent grocers cannot afford the time and expense of filing a RobinsonPatman case. Small towns like Little River, Kansas, can’t either. But New York City, the nation’s largest, has far greater resources. Mamdani could use the leverage of city government to pressure distributors to give fair deals.

This could spur more enforcement outside of Washington. Nine states already have laws on the books that are functionally mini Robinson-Patman Acts, banning price discrimination within their borders. New York is not one of those states, but it could consider passing such a law, giving New York City even more firepower.

A law already on the books could transform the grocery industry by leveling the playing field for small stores.

Mitchell sharply criticized the dismissal of the case. “The FTC has said to the entire grocery industry: ‘Just go back to what you were doing before, we are not at all serious about enforcing this law,’” she said.

New York City’s Promise

So far, the details of Mamdani’s plan remain

Mitchell, of ILSR , stressed the real-world need to reform grocery markets, including with public options. “It’s a daily hardship and indignity for people not to be able to shop for groceries where they live,” she said. “If a city wants to step in and run a grocery store immediately to deal with that, by all means.”

But Mitchell also advises governments, whether federal, state, or municipal, to consider structural change. “The optimal role of government is to structure the market in a way that enables independent grocers, local grocers, to compete and succeed.” n

DOWN AND OUT ON THE CRYPTO FRONTIER

JACKSON HOLE , WYOMING – The shuttle bus rolls beneath the Teton Range. The afternoon is warm and bright. The scene is dreamlike, with aspen trees and tall grasses and round hay bales stacked in neat rows. A black horse and foal are in the center of a field and raise their heads in unison to watch the group drive past. Elk leap over a fence to walk among grazing cattle, then leap out again, free.

The scene makes me catch my breath. I turn to the other passengers, ready to say, “Did you see that?” But my seatmates in the black Mercedes van are all glued to their phones. They work in crypto, they’re heading to the Wyoming Blockchain Symposium at the Four Seasons Resort and Residences Jackson Hole, and there’s no time to look out the window.

They stay locked on those phones even as they commiserate. One man reminisces about how convicted fraudster Sam Bank-

man-Fried’s FTX once ran a conference and gave his company $15,000 to spend. He sighs. That was awesome. Another offers an update on his company. “Everyone is trying to create these walled gardens,” he says, “and we’re trying to create a public good.” The company presented their idea to the

Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Treasury last month: What if you could create a basket of assets that perfectly tracks inflation? The regulators “were super stoked,” he says.

In Wyoming, the Delaware of cryptocurrency, industry players celebrated their fortunes and said everyone will benefit. But workers haven’t seen it.

By Whitney Curry Wimbish ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOSEPH GOUGH

“Ugh, the SEC,” says another man. His company just hired two former SEC employees, and they can’t give clear “yes” or “no” answers to anything. They’re great, but “I just want to work in tech where people are really cracked out,” he sighs. Unfortunately, they’re the ones with expertise in TradFi—traditional finance—and that’s where all the money is.

The shuttle stops at the resort, where the cheapest rooms cost more than $1,000 a night and tickets for the invitation-only conference went as high as $10,000. The crypto guys agree to meet at the gondola later, where decals of American BTO, Kraken, and the Solana Policy Institute are stuck to the windows, blocking the view.

Jackson Hole is a playground for the rich,

but that’s not why Anthony Scaramucci’s company, SALT, is holding a blockchain symposium there. Wyoming is the underappreciated heart of the American cryptocurrency boom; lawmakers have passed more than 50 industry-friendly laws over the last eight years, more than anywhere else in the country. One established the Wyoming Chancery Court for businessrelated litigation, similar to the chancery court system in Delaware. With wide-open spaces and twice as many cattle as people, Wyoming’s political leaders want to base the entire state’s economy on crypto.

The executives, lawmakers, regulators, and even a member of the Trump family who congregated here were in party mode. Fresh off buying Washington, D.C., with hundreds of millions of dollars in the last election, crypto’s elite celebrated the passage of one industry-written federal law, and two others in the works. They gloated about owning the SEC, Federal Reserve, and most of all the White House. They heaped scorn on Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), former SEC chair Gary Gensler, and anyone else who wants to pump the brakes on what proponents say is an inevitable takeover. It’s the Pax Cryptomanica, haters be damned.

They spoke, too, of the public-mindedness of their industry and how it will benefit Wyoming, though they were short on specifics. One man insisted that his cryptocurrency company, which he had recently relocated to the state, would help regular people, but couldn’t say how, exactly. Would it create more jobs? No. Would it fund any social programs? Not exactly. But somehow it would get cash into people’s hands who needed it the most, the details of which would be worked out later.

Then he offered to send me an amethyst from a mine he owns. I declined, per the Prospect ’s policy against accepting gifts of gems.

“Thank you for getting rid of Sherrod Brown!” exclaimed Senate Banking Committee chair Tim Scott (R-SC) from the stage, referring to Ohio’s former Democratic senator, who used to have his job. The main crypto PAC, Fairshake, spent more than $40 million last year to stop Brown’s re-election; it now has more than $141 million stored up for next year’s midterms.

Scott’s panel, the second of the day, was a conversation with Austin Reid, global head of revenue and business at crypto prime broker FalconX, who would later pump a

glop of mayo onto a burger at a cookout and agree that doing so was either trashy or European. But that was ten hours away. It was still shortly after 9 a.m.

“We are working hand in glove,” Scott told the audience. He launched into a story about growing up in poverty with a single mom. “This industry offers a woman like that more access at a lower cost point.” It will also help him “accomplish the goal I had when I was 19 years old, to impact a billion people.” That’s about three times the

population of the United States. Scott praised his fellow banking committee member, digital asset subcommittee chair Sen. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), for cosponsoring the industry-friendly Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins, or GENIUS, Act, which creates a federal regulatory system for the cryptocurrency supposedly pegged to the dollar. It passed with help from 16 Democratic senators this spring, and Donald Trump signed it in July. The law offers a “vision” for what

The Wyoming Blockchain Symposium featured speakers (clockwise from top left) Eric Trump, Anthony Scaramucci, Federal Reserve governor Michelle Bowman, Rep. Angie Craig (D-MN), and Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC).

the world looks like in 2028, Scott said. Reid asked him to elaborate.

“I have a dream!” said Scott, who is Black. The mostly white audience shifted in their seats. Scott chided them: Let a man have some fun. He rose to meander through the crowd. We must innovate before we regulate, “because competition needs time to grow up.” America must “empower people to want to take the risk,” and set rules of the road to make that happen, to “give people the chance to jump in, completely be miserable while they’re failing, and get better.” He returned to his seat and concluded the koan-like monologue about the new law. “That will allow that single mother like me to get more of her money faster.” The audience felt comfortable enough to clap. Reid asked: What advice does Scott have for people in the room?

“Number one,” Scott said, “fire the legislators that are in your way.”

The lone Democratic lawmaker at the symposium, Rep. Angie Craig (D-MN), offered not so much resistance as a shrug. She’s running against populist Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan for a U.S. Senate seat and told the audience that inviting digital assets

With lawmakers in both parties falling all over themselves to win their favor, you can understand the crypto elite’s delusions of grandeur.

into the financial system should be apolitical. Her presence on the cusp of an expensive campaign suggested otherwise.

With lawmakers in both parties falling all over themselves to win their favor and their campaign donations, you can understand the crypto elite’s delusions of grandeur, even amid enthusiastic ignorance. Who even knows what a “CUSIP number” is, sneered Kyle Samani, co-founder and managing partner of Multicoin Capital, on a panel with Scaramucci. The two laughed together. (For the record, it’s the Committee on Uniform Securities Identification Procedures number, the unique identifier for most financial securities in North America.)

“I learned yesterday what a registration statement is,” Samani said, “and I described it to my team as, quote, carrier pigeon for TradFi.”

Eric Trump, whose mining company American Bitcoin just went public in the beginning of September, was on hand as well. He took the stage with the intensity of a black hole, drawing all the attention toward his unblinking face. He towered over the other panelists and hugged them; he said he spends most of his business life involved in crypto, and that Bitcoin would one day soon cross $1 million in price. Crypto “might actually be the best asset class of all,” the president’s son gushed.

Bill Tai, co-founder of NTF company Metagood, offered one of the only sour notes. He said the U.S. has less than two years to build dozens of power plants to accommodate a panoply of data centers set for construction. The entire grid must be “redone,” he said, or “we’re gonna be having some very big issues.” This is an urgent topic in Wyoming, where a recently announced data center near Cheyenne intends to use 10,000 megawatts, the generation capacity of the entire state, as independent news outlet WyoFile reported last month.

You saw all the rolling blackouts in Portugal, Tai said. “In about 18 months, if all of these data centers come up, we’re going to start having that issue in the U.S.”

Another way to resolve the issue would be to not build the data centers, but Tai did not mention that. In fact, he’s counting on a fortune from there being no alternative but to power more crypto. Tai is chairman of the board of Hut 8 Corp., which has remade itself as an energy infrastructure company. Shortly after the conference, the firm announced that it “expects its platform to exceed 2.5 gigawatts of capacity under management” with the addition of four new production sites in Illinois, Louisiana, and Texas. The news pushed its stock up by 10 percent.

Let’s take a tour around the conference. Here is a man in a teal suit jacket and matching cowboy hat, more Huggy Bear than cowboy. Here is Morgan Murphy, a senior adviser to Trump’s special envoy to Ukraine and a food writer, with his dog, Chester. He’s running for senator in Alabama and is “thinking about making crypto a plank” of his campaign.

Here is Brittany Kaiser, who worked at Cambridge Analytica, the company that secretly used personal data from Facebook to get Trump elected. She fled to Thailand with a film crew in tow when the news broke. But now she’s the co-founder of AlphaTon, wearing patent leather red boots and speaking so rapidly and in such a byzantine way that it’s difficult to follow what she is saying.

She is far from the only one speaking in riddles. Her fellow panelist, Jeff Park, chief investment officer of ProCap BTC, utters the following: “The reality is Bitcoin tends to sometimes get a little bit of the short end of the stick when it comes to its utility because part of why people find it so useful is potentially its uselessness.”

If you can explain what that means, the Prospect will pay you ten billion Zimbabwean dollars, cash. That is the denomination of the banknote taped under the audience’s chairs, which human rights activist and pastor Evan Mawarire uses to make a point during a speech about how digital assets can help activists. Conference handouts refer to him as a “Zimbabwean hyperinflation survivor,” but a more accurate description is “torture survivor,” since that’s what the Robert Mugabe dictatorship did to him after he demanded government accountability in 2016 via an online video that went viral.

There are three other panels on human rights and crypto, accompanied by soaring music and video montages. Then the panel discussions snap back to moneymaking.

Here are women in frilly dresses, some of whom brought their dogs, and serious ones in smart ensembles, and others who got into the spirit of the state and the request by conference schedulers to wear “Cowboy Casual.” Some of them have gone downtown to buy bespoke cowboy hats, which range from $245 to $1,795.

Here is Zunera Mazhar, vice president of policy at lobbyist The Digital Chamber, who posted a photo of herself in the conference Telegram channel in cowboy boots and a short leather skirt with a slit up the thigh, standing shoulder to shoulder with the chair of the SEC, Paul Atkins, and two other stylish women.

Here is a man in a cowboy hat and a black shirt with gold diamonds strewn across the fabric, and dark wraparound sunglasses though the room is dim. His cowboy boots are bedazzled with numerous sparkling studs. Here are the casual hoodie tech bros, sleeveless fleece zip finance bros, blazer-withsneakers bros, and at least one Brazilian jiu-jitsu bro.

Here is a man cramming his mouth with popcorn from a red-and-white striped bag in steady five-second intervals. The uninterrupted rustle of paper prompts another man to glare at him from across the aisle. But popcorn guy is rapt by his snack and the speaker, Premier of Bermuda E. David Burt.

David Hirsch, former head of the Crypto Assets and Cyber Unit in the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, has also availed himself of the popcorn. Now he works in private practice representing crypto firms.

Let us go next to the Cowboy Cookout, an evening activity that followed the first day of speakers, held at a ranch near the foot of the Tetons and sponsored by blockchain platform Avalanche. The same day, Fortune reported that Scaramucci’s SkyBridge Capital would bring $300 million in assets to tokenize on Avalance’s blockchain, about 10 percent of total assets under management.

Elk graze in the distance. Servers pass what they say is crudités: two celery sticks and two mini carrots rolling around in a paper dish, with an optional puddle of ranch dressing. A drone zips above the party and a man drives his rental car into a ditch.

I talk to a “digital nomad” from the Bay

Area who says he was once a park ranger in Yellowstone. He’d like to move back to Jackson Hole, but everything is expensive, so he’s come up with a plan. “I’ll start with a studio,” he says, “and rent it out to companies who need a Wyoming address.” So they can get the Wyoming tax benefits? Yes, but what they really need is a human who has the address. “Luckily, I’m a human.”

There are a lot of swindlers in this industry, and you might not know that right away, a man who’s at the party with his wife tells me. Both are executive coaches. The man is also an ex-Marine, or, as he puts it, “a protector.” Scaramucci is also making the rounds, urging people to call him Tony. “He’s one of the good guys,” the protector says.

The sun sets behind the mountain range and the temperature drops. Ground fog rises

through the field. The rental car is still in the ditch. “That’s a problem for tomorrow,” says the man who put it there. A woman laughs as they catch the Four Seasons shuttle back to their rooms. “I like that attitude.” she says.

“Regulatory capture” used to mean corruption. And, well, it still does. But crypto executives in Wyoming discussed it as an imperative. Take Henson Orser, founder and CEO of Soter Insure, which provides theft and loss insurance for digital assets. If there is to be a global crypto economy, he said, “you nevertheless need to have local regulatory capture.” That was the overwhelming sentiment of the symposium, and it was on display immediately.

Fortunately for the industry, the regulators are so happy to be captured these days,

One expert estimated that the number of digital asset companies domiciled in Wyoming runs into the “thousands.”

they’d probably build the prison cells themselves. The ones who took the stage were bent on jamming cryptocurrency into the American financial system.

The crypto industry has for years seethed at the SEC, led in the Biden years by Gary Gensler, who once called the digital asset industry the “ Wild West ” because it lacked adequate investor protections. But “it’s a new day,” said Gensler’s successor, Paul Atkins.

The agency is no longer “head in the sand, hoping crypto would go away,” Atkins said. Instead, the recently announced Project Crypto and other initiatives will make sure everyone in the room has what they want, including the ability to choose what regulator oversees their outfit, so that “if one regulator becomes too obstinate,” they can take their idea and go to another.

Atkins praised the passage of the GENIUS Act, “which was great, hallelujah,” called Scott “a great guy,” and looked forward to the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act, which passed the House in July and would create a regulatory framework for all digital assets other than stablecoins. The centerpiece of the bill would take oversight over most crypto assets away from the SEC, and to the much friendlier Commodity Futures Trading Commission. And here was the head of the SEC, beaming about the prospect of having his agency’s power stripped away.

“The good thing is we have a president who’s thrown down the gauntlet. I mean, he’s not shrinking from this and he understands the importance of it,” Atkins said, adding that Trump wants “the world running on American technology” and for the country to be “the crypto capital of the world.” The Trump clan, of course, has gorged on crypto cash. It now represents more than half of Trump’s total net worth.

“There’s a benefit to not regulating too quickly,” said Ian De Bode, chief strategy officer of Ondo, on a later panel, and he’s “in active conversations with the SEC about

how to figure this out.” Until last year, De Bode was a partner at scandal-addicted consultancy McKinsey, which helped the first Trump administration terrorize immigrants. His aside about grinding the regulators into submission was unintentionally revealing about how capture works.

Michelle Bowman, vice chair for financial supervision at the Federal Reserve, was another bearer of good news, telling the audience that it was “inspiring” to be at the symposium, extolling the virtues of tokenized assets, and remarking that stablecoins “are now positioned to become a fixture in the financial system” thanks to the GENIUS law.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City would hold its own symposium in the same town in just a few days. But before then, Bowman sympathized with the crypto industry’s unsatisfying interactions with regulators.

“When you start from a world of possibility, where you move fast and break things to make rapid improvements, you may struggle with the complex and rigid regulatory constructs familiar to bankers and regulators,” she said, and reassured the audience that “despite this past inertia, change is coming.”

Bowman explained what questions the industry should answer for regulators and mentioned her recent fireside chat about artificial intelligence with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, whose Chat GPT program led a teen to kill himself this year, his parents allege in a lawsuit, including by providing encouragement and detailed instructions on how to tie a noose.

But regulating based on “an imaginary ‘worst-case’ scenario” is not the way forward, Bowman said, nor is it the role of examiners or policymakers to direct which customers or industries to serve or which products to offer. That’s the job of bank management. The relationship between industry and regulators should be collaborative, she said, and Fed staff should be allowed to hold crypto. Otherwise, how will they know how it works? “I certainly wouldn’t trust someone to teach me to ski if they’d never put on skis,” Bowman said.

Caitlin Long, founder and CEO of Wyoming-chartered Custodia Bank, sat smiling in the front row, sometimes pumping a fist in agreement. Her bank is for cryptocurrencies and offers various services, including custody and a token it calls an “electronic negotiable instrument.”

She’s been locked in a regulatory fight for the last two years after the Federal Reserve

board denied her application to make Custodia part of the Federal Reserve System because she failed to convince members that it could operate in a safe and sound manner. “Instead, the record indicates Custodia could in fact pose significant risk to its community,” the Board of Governors ruled.

After Bowman’s speech, Long tweeted, “ PINCH ME!! – the @federalreserve Vice Chairman for Supervision is making a speech *supportive* of #tokenization & @ stablecoins, incl facilitation of near-real time payments, in my home state – the leading state for #crypto – of #Wyoming. ‘Change is coming’ – Bowman ”

The digital asset industry has good reason to pick Wyoming as its HQ. In addition to being the least populated state in the union, it’s also one of the world’s major tax havens, drawing wealthy elites from all over who want to hide their money from investigators and tax collectors.

The state’s “cowboy cocktail” of laws, as wealth managers call it, offers a variety of maneuvers, such as the ability to create a trust with a private company at the head rather than a specific person, and another law that allows for the creation of a company within a trust to hold bank accounts, property, and other assets. The state offers 1,000year dynasty trusts, laws that protect assets against creditors, and freedom from taxes on capital gains, estates, gifts, or income.

There are incentives for creating limitedliability companies, the formation of which Wyoming was the first to authorize in 1977, though Delaware steals all the credit as the home of legalized financial trickery. Wyoming LLCs have tripled over the last five years, outstripping Delaware as the location of choice, according to OpenCorporates. In 2023, 166,960 entities incorporated in Wyoming, and all but 8 percent were LLCs. That’s 348 LLCs per 1,000 adults in Wyoming versus 268 in Delaware. It’s easy and cheap. First hire a registered agent, which can run as low as $25 a year, according to one firm’s online advertisements. Then pay the state’s fee of $100.

The arrangement has made Wyoming attractive for crooks. In March, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found that a small building in Sheridan was the incorporation address for 266,000 companies between 2019 and 2024, including one called Alo Group. That company used its Wyoming address when it received more than $500,000 in emergency COVID -19 Pay-

Everyday residents in Jackson Hole struggle to keep up with rising cost of living on meager salaries.

check Protection Program money from the U.S. government. Then it switched its mailing address to China. Then it disappeared.

The same laws have made Wyoming attractive for cryptocurrency companies.

Steven Lupien, director of the University of Wyoming’s Center for Blockchain and Digital Innovation and Long’s life partner, estimated in July that the number of digital asset companies domiciled in the state runs into the “thousands.”

During the conference, Gov. Mark Gordon unveiled the nation’s first state-sponsored stablecoin, the Frontier Stable Token, or FRNT. It will be available on Avalanche, Base, Ethereum, Optimism, Polygon, and Solana. The state will hold collateral for the tokens at 102 percent and put income over the reserve requirement into a public school fund, lawmakers said.

Asked for her thoughts on Wyoming’s embrace of crypto while waiting for a hamburger at the Cowboy Cookout, Long told me that it’s all “about jobs, it’s about revenue to the state, and it’s about the University of Wyoming, attracting donors, students, and scholars in this space.” Others echoed Long’s optimism about the rise of the state’s digital asset industry.

But Lee Reiners, lecturing fellow at the Duke Financial Economics Center, said that, for all of Wyoming’s chatter about the benevolence of its stablecoin and crypto’s

benefits, lawmakers still haven’t solved the central problem that the industry is full of liars and thieves. The stablecoin, for example, could easily be used to fund drug trafficking or launder terrorist financing.

The digital asset players brush that aside. “Nobody believes that anymore,” Lupien told me in an interview before the symposium. Unless you’re a real anti-crypto zealot like Elizabeth Warren, this is the way the world is going,” he said. “I think the day of referring to us as money launderers or drug dealers or terrorists is gone.”

That style of thinking has made Wyoming a magnet for the industry. Crypto exchange Kraken relocated its headquarters to Cheyenne in June, because the state’s pro-crypto environment “made it a uniquely well-situated backdrop” to “foster institutional understanding” of cryptocurrency as an asset class. The press release announcing the move includes a quote applauding the decision from Sen. Lummis, who took the stage with Kraken co- CEO Arjun Sethi. Lummis has been crypto’s cowboss in Washington for years now. She has been pushing, along with Custodia, to give Wyoming crypto banks access to the federal payment system, as well as calling for the creation of a “strategic Bitcoin reserve.” Her nickname is the “Crypto Queen.” At the conference, Lummis forecast that the Senate’s version of a market structure bill, which she

predictably co-authored, would be voted out of the Senate Banking Committee by the end of September and finished by the end of the year, hopefully before Thanksgiving, which the audience rewarded with cheers. Kraken’s Sethi commented that he’s still stuck in California’s expensive Menlo Park after his company relocated. He wants to move to Jackson, but that’s expensive, too. “Can you subsidize my house?” he asked Lummis. “Move to Cheyenne and I won’t have to,” she responded. Cheyenne is the seat of Laramie County, where Lummis lives. The audience laughed.

Sethi asked about Lummis’s crypto holdings; she has individual stock and five Bitcoin in a blind trust, she said. “Which exchange do you use?” Sethi asked. The audience laughed again, this time punctuated with “ohhh!” Sethi offered for his firm to custody her assets “in a blindly trusted way. I’ll leave it there.” Lummis threw her head back and laughed, clapping over her head. “I’ll say this to that: Arjun, you had me at hello.”

That evening, the two held a fundraiser for Lummis at the Teton Village home of former Interior Department official Rob Wallace and his wife Celia, where the suggested contribution was at least $1,000.

There is another story in Jackson Hole that deserves oxygen, one that unfolds every morning at dawn.

Not a single worker I spoke with had heard about the state’s cryptocurrency industry or Wyoming’s new stablecoin.

It is 7 a.m. on a crowded local bus from downtown. Riders greet each other briefly, mostly in Spanish, sometimes in English, then settle in for the hour-long ride to Teton Village, where the symposium is taking place and where snow and sun bunnies stay in luxury resort suites. One-way bus fare is $3, higher than the cost of public transportation in New York City.