There are many contemporary pressures and shifting roles within architectural practice and education. The discipline is ever-growing and constantly evolving. Throughout this paper, the profession is discussed expansively and then centres an argument on the diminishing polymathy and cross-disciplinary teachings that architecture has benignly faced in recent times. Dynamic paradigms are causing tensions in the architectural space; with some arguing that an algorithmic approach to architectural education and practice has overtaken the celebration of individuality and unique creative design. Beginning by looking into the contemporary use of the word polymath and what it means to learners today and then contrasting it against its origins, then looking at the recent resurgences of the term and what could potentially be a ‘new-wave’ renaissance that would become a saving grace for artistic fields and the creative world. Boundaries between disciplines are blurring as technology grows and learning resources become more available to people so those who draw on knowledge from many fields have become the essential drivers of innovation. Polymathy, as a concept, has its roots in the Renaissance period, often heralded as the epitome of human creativity and the rebirth of art, science, engineering and humanitarianism as we knew them. However, modern architecture has to face a new challenge with the growth of technology and the digitalisation of architecture right before us. We are witnessing unimaginable change with the use of AI and other computer software that is stripping away the soul of design. With a growing reliance on specialised, technical skills the conversation of the future of architecture must be discussed. Polymathy, although still valued in theory, is becoming less and less visible in architecture; however, it may be the answer to combat this digitalisation, the commodification of design and the focus on meeting technical and sustainability requirements when there is no need. This paper will aim to question why this is the case and what actions can be taken to reintroduce polymathy and restore architecture as the artistic expressionism of building design.

1

Albert Einstein’s Bookplate

A figure standing on the top of a mountain surrounded by a star filled sky. Made by the artist Erich Brisson.

Venice.

Recent contemporary research has showcased the plethora of benefits that polymathy can have in creative fields. As Miura (2020) suggests, “Interdisciplinary thinking enables designers to approach problems from diverse perspectives, fostering solutions that are both innovative and adaptable.” This way of thinking is no longer just a desirable trait in practice but essential for addressing complex, systemic challenges like the climate emergency, urbanisation of farmland and social inequality. For all practising and future architects, embracing polymathy means going beyond the confines of traditional design education by instead becoming active learners and seeking knowledge and understanding in fields such as environmental science, sociology, data analytics, humanitarianism and psychology. “To develop a complete mind: Study the science of art; Study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else.” (da Vinci, 1883, p. 46). Unfortunately, this is rarely encouraged in the current architecture curricula, which often prioritise narrow technical proficiency and repetitive design structure over broad-based learning.

The algorithmic approach to architectural education has created both opportunities and constraints; we must attempt to negate the downsides and also use new technology as an aid, as opposed to drawing a reliance on it. Certainly, tools such as parametric design and building information modelling (BIM) have revolutionised how architects can conceptualise and visualise projects with 3D modelling becoming a staple of practice and education. However, these tools may have begun to stifle creative experimentation and have instead generated a dependency on computer-aided design (CAD) with a lack of free-flowing ideas and sketching. As noted by Schumacher (2022), “Algorithmic design offers precision but risks producing homogeneity, where buildings are optimised for efficiency rather than distinguished by individuality.” This phenomenon has led to the rise of what some critics call “cookie-cutter” architecture, where designs are mass-produced with little regard for their cultural or artistic context.

There is no question that educational institutions play a major role in shaping the architects of tomorrow. After analysing and cross-examining it’s clear that boards such as the Architects Registration Board (ABR) often emphasise technical and regulatory competencies to ensure employability, but does this come at the cost of creative exploration? Their recent reforms have drawn vast criticism for this prioritisation and lack of support for creative brilliance. As RIBA Board Chair Jack Pringle (2023) points out, “Competence and innovation must go hand in hand, but recent shifts risk sidelining the latter in favour of standardised design outcomes.” To combat these changes, architecture schools must find a way to balance technical rigour while also providing opportunities for interdisciplinary development and creative exploration.

Finally, the paper will form an argument and discuss how and why reintroducing polymathic principles into education and practice is necessary. Encouraging those who design to develop broader and more well-rounded skills could lead to the resurgence of individual talent and potentially another shift in architecture as we know it. By embracing polymathy, architecture can reclaim its status as both a technical and deeply artistic discipline, addressing contemporary challenges while inspiring future generations.

4

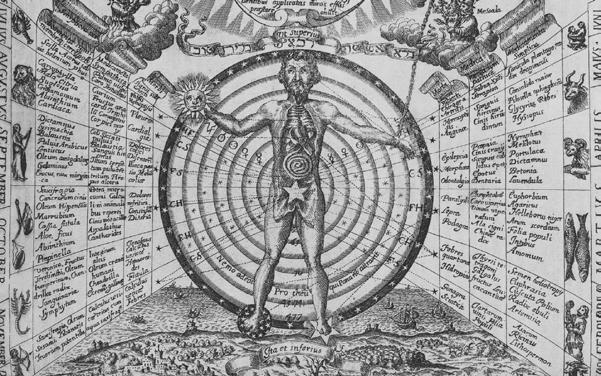

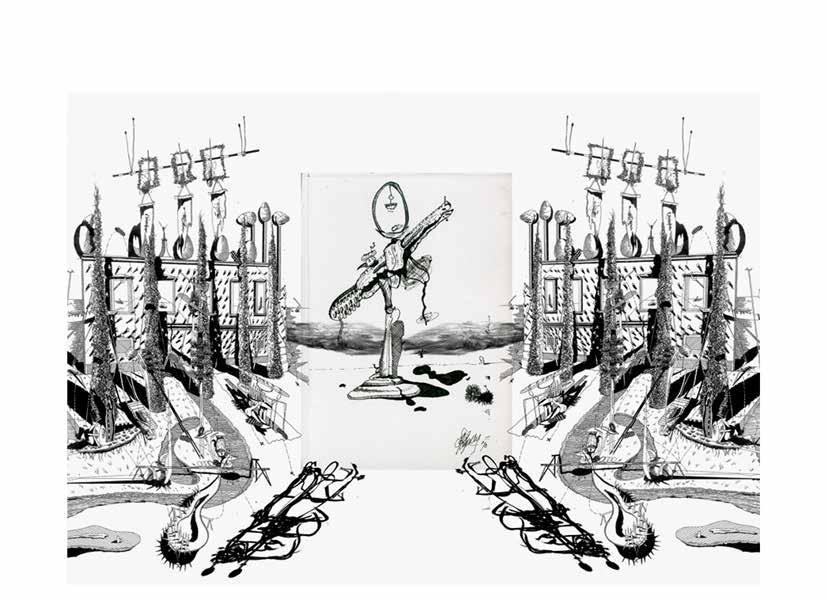

This chart is taken from the book ‘Ars

which was published in 1646 by the Jesuit scientist and inventor,

Commonly misinterpreted as a ‘jack of all trades’ ideology, Polymathy, at its core, is the deep-rooted understanding and mastery of a modicum of disciplines and the application of those skills in conjunction within one particular area or field. “A polymath is someone who becomes competent in at least three diverse domains and integrates them into a top 1% skill set.” (Ahmed, 2018, p. 24). The word polymath comes from the Ancient Greek word polumaths, which means “having learnt much.” It is an accumulation of the words polús, which means “much,” and manthánō, which means “to learn.” The first documented use of the term was in 1603 by Johann von Wowern in his work De Polymathia tractatio: integri operis de studiis veterum. Von Wowern defined polymathy as “knowledge of various matters, drawn from all kinds of studies” (Von Wowern, 1603). A Polymath has since become an umbrella term that covers a large base of names and historical figures such as ‘the Renaissance man,’ ‘the universal man,’ and ‘Polyhistor.’

Many imagine the Renaissance era in Italy as the birthplace of polymathy with figures such as Brunelleschi, da Vinci, and Alberti being the founding fathers of multidisciplinary mastery. “An architect should be able to do much more than just design buildings. He should be an expert in history, geometry, and the natural sciences.” (Alberti, 1485, p. 67). This highlights how polymathy was integral to Renaissance thinking, where architecture was seen not merely as a profession but as a practice that intertwined various disciplines. Alberti’s views emphasise the importance of breadth and depth, which are often lacking in contemporary architectural education.

So, in current, contemporary terms the new-wave Renaissance largely relies on the same historic ideology but applies the practice to new contexts such as the use of technological advancement and the vast amounts of ongoing research to further knowledge within a multitude of disciplines.

5

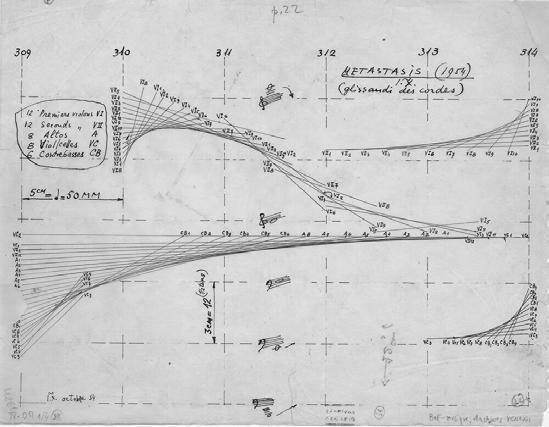

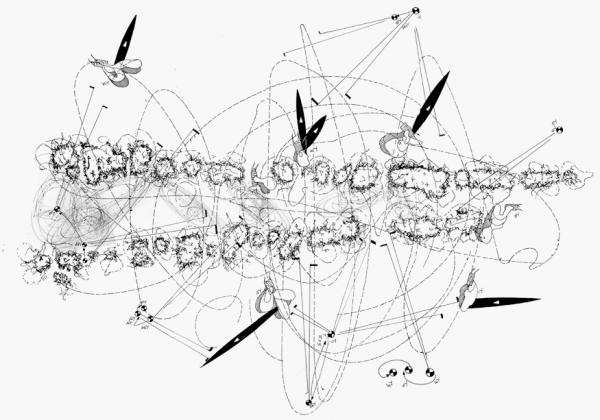

Metastasis Bars 309 to 314, 1953-1954 Image: Courtesy of the Xenakis family

Unlike their historic counterparts, contemporary polymaths benefit from tools such as the internet, and online teaching allowing them to synthesise knowledge at a speed previously unimaginable. Considered to be current-day architectural polymaths are Santiago Calatrava, Neri Oxman and Tadeo Ando. “Architecture is not only a science, it is also a deeply human art that must reflect the beauty of life, nature, and the human spirit. The fusion of engineering and artistic expression can create works that transcend pure function.” (Calatrava, 2011, p. 85).

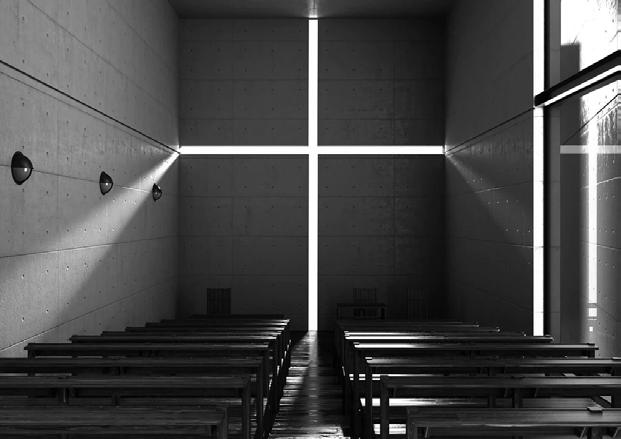

Expanding on this, a contemporary example of a building project that was developed by Tadeo Ando, considered to be a current polymathic architect, is the Church of Light in Osaka, Japan. Built in 1989, the structure exemplifies Ando’s ability and knowledge in many fields, with the primary showcase being his blend of philosophy and religion within the design and artistic approach. Ando uses a playful mix of concrete and light to juxtapose each other while simultaneously creating a spiritual and contemplative atmosphere. Ando’s polymathic approach to this project provided him with significant recognition by winning the 1995 Pritzker Architecture Prize alongside the International Award for Architecture in 1999. These recognitions demonstrate clearly that, when designing, a multi-disciplinary approach can lead to a profound and impactful outcome.

The resurgence of this methodology in the modern era is especially evident in the technology industry, where the capacity to integrate insights from multiple domains such as engineering, psychology, business, and art is seen as a key to driving exceptional work in the field. The digital age has democratised access to knowledge. “In the age of the internet and digital tools, polymathy is more accessible than ever before, allowing individuals to transcend boundaries between fields, engage with multiple disciplines, and apply knowledge in innovative ways” (Kaufman, 2020, p. 45).

This accessibility fosters self-taught expertise, supported by online platforms such as MOOCs, YouTube tutorials, and open-access resources. Consequently, a new generation of polymaths is emerging, bridging domains like science, technology, humanities, and art to address complex global challenges, including sustainability, artificial intelligence, and urban planning.

In the context of creative professions, polymathy is increasingly recognised as a remedy for the compartmentalisation that stifles innovation. Many industries value cross-disciplinary knowledge as a driver of creativity. “Polymathy fosters creativity by allowing individuals to approach problems from multiple perspectives, which is particularly valuable in design and architecture, where innovation often comes from the intersection of art, science, and technology” (Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein, 2017, p. 78). Modern architects, for example, can blend digital technology, environmental science, poetry, art, and philosophy to produce designs that are not only functional but also deeply meaningful. This aligns with the growing demand for humanitarian and emotionally resonant design solutions.

Although this is the modern use of the term, its application in architectural education has not yet been wholly integrated. Architecture has always been a balance of science and art so it follows that in order to keep this balance, artistic and scientific expressionism must be shown and taught equally. “Educational institutions have increasingly emphasised technical skills over creative breadth, leaving little room for the interdisciplinary thinking that once defined architectural mastery” (Wilson and Anderson, 2019, p. 119). As a result, architecture often suffers from lifeless, generic designs—a phenomenon exacerbated by over-reliance on digital tools. “Digital tools and algorithmic design processes have both enabled and constrained creativity in architecture, emphasising technical efficiency over the broader interdisciplinary knowledge that once defined the profession” (Wilson and Anderson, 2019, p. 123).

A more profound integration of polymathic principles in architectural education could address these challenges. Encouraging architects to draw inspiration from diverse disciplines could lead to a renaissance of innovation and individuality in the field. “Architects equipped with interdisciplinary knowledge can create spaces that resonate on multiple levels, blending technical precision with artistic vision” (Smith and Clarke, 2021, p. 67). The profession must adapt its pedagogical methods to foster polymathy. This would involve reshaping curricula to include not only technical and regulatory competencies but also opportunities for students to explore subjects like philosophy, environmental science, anthropology, and digital humanities.

The growing reliance on digital technologies presents both opportunities and challenges for the integration of polymathic approaches in architecture. While digitalisation offers unprecedented tools for efficiency and precision, it often prioritises standardisation and algorithmic thinking over creative and interdisciplinary exploration. This tension highlights the necessity for architects to critically engage with technology, using it not merely as a tool for replication but also as a medium for innovation. By bridging the gap between traditional polymathic ideals and the capabilities of contemporary digital tools, the architectural field can evolve to meet modern demands without sacrificing its creative and humanistic roots. This dynamic interplay between digitalisation and polymathy sets the stage for examining how technology is reshaping the profession and education of architects.

Discussing the digital age is a challenge due to the ever-changing shifts in technology. In the context of architecture, however, it can be easier to analyse by looking at the updated building codes and architecture curricula as well as the modern techniques that are currently being used by practising architects. Discuss whether they do indeed remove creativity from the design process entirely or do these tools allow for greater creativity. For example, can AI solve some of the technical issues/maths thus allowing for a flourishing of more ‘out-there’ ideas?

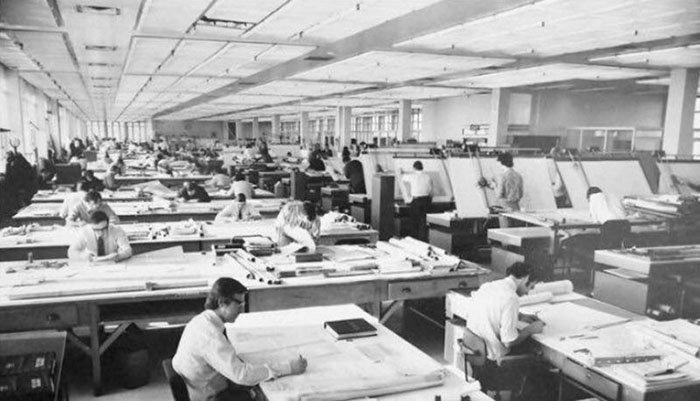

The digitalisation of architecture has revolutionised the way buildings are designed, constructed, and managed. Tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software have become essential in modern architectural practice, providing architects with the ability to create highly detailed models and simulate construction processes with precision. These tools have streamlined workflows, enhanced project coordination, and allowed for the efficient management of complex structures. However, this heavy reliance on digital tools has also introduced significant challenges, particularly concerning creativity and individuality in design. BIM and CAD software, while powerful, often encourage architects to follow standardised templates and preset parameters, prioritising efficiency and technical accuracy over original, artistic expression. “The integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) into architecture is reshaping how design, construction, and management processes are carried out. BIM enables more efficient collaboration, real-time updates, and accurate visualisations, ensuring that every stakeholder has access to the latest project information. This digital shift reduces errors, enhances productivity, and improves sustainability by optimising resource use and minimising waste.” (Eastman et al., 2011).

The inherent logic of BIM and CAD systems can lead to formulaic designs that lack the uniqueness and innovation that once defined architecture as an art form. The integration of these tools into every stage of the design process risks turning architects into technical operators rather than creative thinkers, as the focus shifts towards meeting the efficiency-driven needs of developers, contractors, and regulatory bodies.

While these tools allow for error reduction and facilitate the design of highly technical projects, they can limit the ability to experiment with new forms, materials, and concepts. The over-reliance on digital workflows tends to favour safe, tested solutions, which in turn contributes to the rise of cookie-cutter buildings ie. structures that meet functional needs but fail to inspire or push the boundaries of architectural thought. As a result, digitalisation has created a growing tension between technical mastery and creative freedom, leaving many to question whether architecture is losing its artistic soul in the pursuit of efficiency. This pursuit has also begun to bleed into the architectural curricula with some universities encouraging practical solutions to briefs rather than pushing the creative theoretical boundaries by teaching young learners that ideas should always be grounded in reality. This is apparent in the Architects Registration Board’s (ARBs) newest curricula proposal for 2027 where they are trying to emphasise technical competencies like sustainability and safety at the expense of creative exploration. Jack Pringle (2023), Chair of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Board, has expressed concern that the reforms “fail to ensure that competence and innovation in architectural education are prioritised”. We can see from the many responses of professionals that the proposed changes have elicited a variety of opinions. Of course, a highlight on design safety and human consideration is hugely important but that does not mean creativity should be neglected and forgotten. Wendy Colvin, an architect and senior lecturer, sees the reforms as ‘potentially beneficial but stresses the importance of maintaining the core creative aspects of the profession while improving access to registration.’ (Colvin, 2023)

Old-School Pre-CAD Drafting Pools

Shots of Old-School Pre-CAD Drafting Pools Core

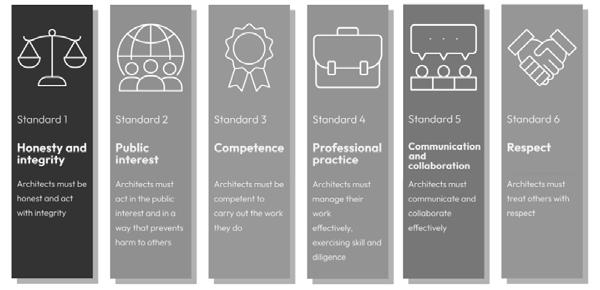

To gain a better understanding of this we must look deeper into the RIBA and the ARB and analyse what makes them so different and what we can learn from both moving forward in teaching the new wave of architects. Starting with the RIBA which has a long history of positioning itself at the forefront of creativity, individual brilliance, and the broader intellectual development of architects. This stems from its focus on fostering innovation and maintaining architecture as a profession deeply rooted in art and culture, as well as technical skill.” We must continue to champion the power of design and the unique skills of architects to address the challenges of our time” (Allford, 2021). This reinforcement is clearly stated in initiatives such as the RIBA President’s Medals, which celebrate exceptional individual projects that push the boundaries of design. This, along with many other examples, showcases that the RIBA is actively trying to recognise and celebrate the individual for forwardthinking design. The RIBA also pushed for wider research to be conducted and reward design that is constructed in many fields of research, aligning clearly with the ideology of polymaths in the Renaissance. Insights, as recent as 2023, suggest that the RIBA was unhappy and unsupportive of the ARB and how they were conducting and curating the new architecture education outlines and curriculum in preparation for the upcoming changes. The ARB, as a statutory body, emphasises compliance, technical proficiency, and public safety, often prioritising these over the fostering of creativity or the encouragement of broader intellectual pursuits. While this approach can be valuable and is critical to ensure that future architects are being taught the limitations of their work, with safety being the number one priority, this can come across as rigid and suppressive of individuality.

RIBA also critiques the ARB’s bureaucratic processes, which can be seen as a hindrance to creative and entrepreneurial practices within the field. Whilst documenting the research for this paper the ARB released their proposals for the ‘Architects Code’ text which lists six driving standards that all architects in practice must follow strongly; Honesty and integrity, Public interest, Competence, Professional practice, Communication and collaboration and Respect. While all of these are vitally and fundamentally important, the ARB is still neglecting the use of creative, forward-thinking design for architects which, therefore, risks removing the motivation and enthusiasm of people to create innovative pieces of work that will instigate discussion and to instead simply follow trends and copy what has come before them with no premeditation.

This argument will aim to provide a critique of the way architecture is progressing while also attempting to propose one of many solutions to avoid this art falling into the corporate world and becoming too stale. There have always been and will always be innovators in the design of spaces but to allow this to continue we must look at, and understand, that if things keep progressing down the road of AI and heavily computer-assisted workflow then things will look bleak in the future. Spiller said “The future of architectural education lies in embracing a pedagogical approach that integrates both theory and practice, enabling students to engage critically with the built environment.” (Spiller & Clear, 2014, p. 45). By making certain that architectural education is grounded in creative expressionism and encourages individualism we can be sure that the creative aspect of this profession will not be lost. “The role of technology in architectural education is to enhance the creative process, rather than replace the fundamental skills of design and critical thinking.” (Spiller & Clear, 2014, p. 108). We therefore must also push the ideology of polymathy in this curricula and encourage wider learning and skill-making as “to understand architecture, one must appreciate that it is an open system, continuously influenced by external factors such as culture, politics, and economics.” (Till, 2009, p. 130). The clearest solution to algorithms plaguing architecture is to make certain that students and those in practice fully understand the tools available are to be used as aids or tools, not complete replacements. It’s impossible and impractical to suggest the abolishment of AI and computer-aided work but architects must retain control over the design process, using algorithms to enhance their creative output rather than to limit it. A pioneer of this collaboration is Studio Gang’s design for the California College of Arts where computational design aspects were employed to solve the environmental challenges whilst the architects prioritised the design process and the vision of the project.

This allowed for a collaboration of sorts by allowing the technical works to be completed by the trusted and structured algorithms but the human intervention comes when we look at aesthetics and artistic choices, avoiding computational assistance as much as possible in this stage of design. “Engaging with students and local residents throughout the design process ensured that the new building reflects the aspirations of the college and the broader community.” (Gang, 2019, p. 52).

The most significant concern that arises due to the increased usage of AI and lack of polymathy in architecture is that it will diminish the role of human creativity and humanism in designs. Architecture has never been about just solving technical problems and creating efficient lifeless designs. It’s clear that when used correctly, algorithms and AI are able to optimise functionality and efficiency, however, they are ultimately limited by their programming and source material/data inputs. With the lack of ability to conceptualise, sympathise and think like a human, architecture can never reach the same capability and have the same soul and emotion that humans can convey. “The fundamental nature of architecture is human experience, and this cannot be fully captured by algorithms or digital tools” (Pallasmaa, 2012, p. 34). This creates the risk that architecture, over time, will become increasingly generic with aesthetically bland design and no cultural significance and character.

This leads to the next concern that could occur due to the growth of algorithms and computational design which is the decline and gradual loss of architects’ intuition and judgement. Architecture has historically always been a humanistic discipline that relies upon the intuition of the designer, years of experience and a vast understanding of social, cultural and emotional factors. As Till (2009) argues, “To understand architecture, one must appreciate that it is an open system, continuously influenced by external factors such as culture, politics, and economics” (Till, 2009, p. 130).

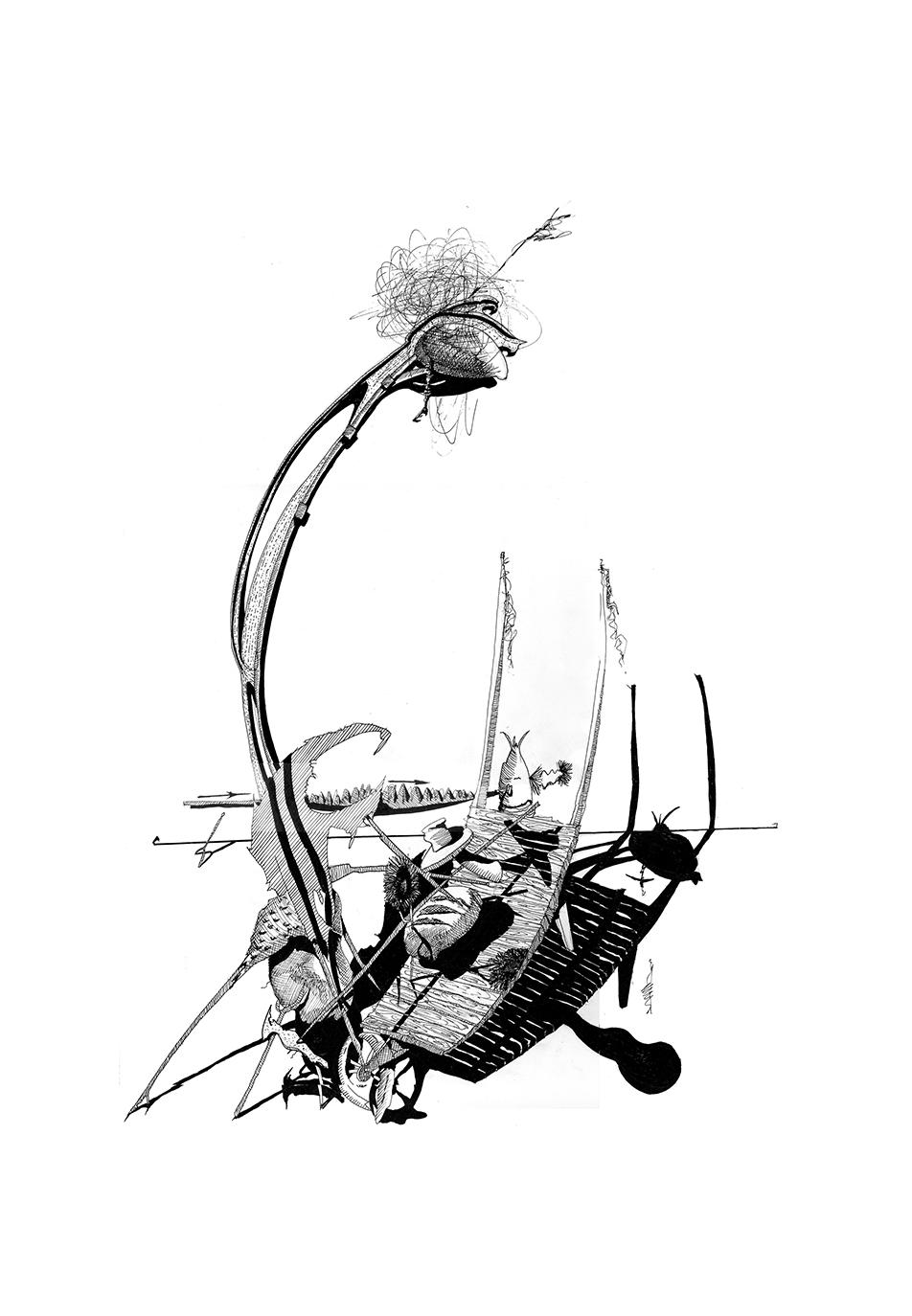

Aughtman’s Square 1

Even though algorithms are capable of processing data and creating design optimisation, they are simply unable to account for the intangible qualities that create meaning for the occupants and the broader communities that would be affected by it. As Spiller & Clear (2014) cautioned, “Architectural education and practice must retain an emphasis on creative expressionism and individualism, ensuring that the profession does not become mechanised or impersonal” (Spiller & Clear, 2014, p. 108).

Looking at the other side of the argument to gain a deeper, broader understanding of this problem, we can see AI and algorithms as a tool. An aid in design that can be used to exhaustion to eliminate the human error of design. One of the most compelling arguments that support integrating AI into architecture is the increase in precision and efficiency that it provides. When used correctly, computational applications can free architects by automating the tedious, repetitive tasks and taking projects that would have previously taken months, or even years, to design and cut them down to week or month-long projects. This would be unimaginable to architects just a few decades ago; illustrating just how fast technology can move and why adaptation to the current times is critical. Acting as if these tools don’t exist and rejecting them entirely would be foolish due to their helpful qualities. As Spiller & Clear (2014) noted, “The role of technology in architectural education is to enhance the creative process, rather than replace the fundamental skills of design and critical thinking.” They have clearly understood already that combining the power of algorithms and human design will enhance visions.

Within this argument, we must also discuss the paradox of the digital age. While information has become more accessible and widespread than ever before, it has subsequently caused hyper-specialisation and rather than people wanting to learn multiple fields in depth they attempt to bury themselves in one topic causing dead ends in new design.

Some people believe that polymathy is no longer viable as the amount and depth of knowledge have passed the capacity that the human brain is able to retain, “As knowledge increases, the human capacity to master it remains finite. This reality compels a move towards specialisation, as the breadth of knowledge becomes unmanageable for individuals to sustain across multiple domains.” (Baker, 2015). However, I and many others believe that this is not the case; just as the founding fathers before us did, we must extend our knowledge across a range of disciplines and master them as expertly as we are able to. “Specialised thinking can become a trap that limits the scope of understanding. True problem-solving requires the ability to synthesise ideas across disciplines, not just focus narrowly on one.” (Gardner, 2011)

To complete this argument, the future of architects relies on how the profession responds to this algorithmic growth and how the profession can navigate a constantly changing landscape by effectively managing the balance of technological advancement and the preservation of humanrooted design. While the growth and importance of AI and computational power are indisputable, the way architects respond to them can be. Believing that architecture will become overrun with diminishing, soulless work can cause a jumpstart into action to prevent this from happening future architects are taught that AI should never be the final steps of a design but simply a tool to be utilised along the way and that it is important to use their skills from multiple disciplines to create unique and forward-thinking work that will translate into practice. To ensure that architecture does not fall into the mechanised and generic state, the importance of creative expression must be shown in our academic schemes and practice workplaces.

This debate is currently ongoing as it must be understood that we are currently in the process of deciding what should be the appropriate compromise between the long-term importance of polymathy in the 21st century, and the adjustments needed to make architecture more interconnected. The loss of polymathy and personal genius in architecture schools and practices represents a radical reversal in the profession’s current approaches to creativity, knowledge and innovation. This disparity is not only a function of individual abilities or preferences but also reflects structural challenges within the discipline, driven by a growing dependence on technical expertise and narrow specialisations. What lies at the heart of the problem is a wider cultural and professional pressure to value productivity and compliance above the multidisciplinary and creative thinking that once defined polymathic thought.

Architecture has always been a discipline that has needed a deep engagement with a range of subjects, from mathematics to engineering to philosophy and art, renaissance polymaths exemplify the power of this with figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Leon Battista Alberti blending their diverse intellectual understandings and traditions into some of the greatest works we have documented. Having work grounded in various fields of knowledge these great minds are still studied as inspirations for architects today. As the renowned architectural historian Kenneth Frampton noted, “The architect is not simply a technician, but rather a cultural agent whose work demands an engagement with both art and science” (Frampton, 2007, p. 10). The ability to move fluidly through practices and integrate the arts and sciences is the mark of a true polymath. As we progress into the contemporary world we must use these pillars of understanding and apply them in a relevant way meaning a focus on using and understanding technology.

Organisations like the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and ARB (Architects Registration Board) continue to play a role in maintaining professional standards and pushing for architects to possess the technical proficiency required for safe and ethical practice. These organisations and many others like them are essential to upholding the integrity of the profession and the safeguarding of the public interest. However, as previously discussed, because some of these organisations put emphasis on technical proficiency, legal compliance, and regulatory standards, which can sometimes overshadow the interdisciplinary and exploratory approaches that are characteristic of polymathic thinking, they are inadvertently constraining the creative potential of architects. Whilst these qualities are crucial to ensuring safety and functionality, they do limit the space for more experimental or cross-disciplinary approaches. As architect and educator Juhani Pallasmaa asserts, “The pursuit of technical efficiency has led architecture to an aestheticisation of the technological, while humanistic values are often reduced to the background” (Pallasmaa, 2012, p. 52). This observation highlights how the professional environment, especially in regulated bodies, can prioritise technical precision at the cost of broader creative exploration.

The rise of digitalisation has also further complicated this dynamic. Computational tools such as BIM and CAD continue to push forward with constant updates and useful features. The use of these technologies will always be an invaluable asset to architects and designers, but finding a balance between these tools and analogue techniques to not hinder the design flow and fluidity of the brain still needs to be explored even further. It is clear to see that while digitalisation has provided unprecedented opportunities for innovation, it has also contributed to the same narrowing of focus within architectural practice as the aforementioned curricula standards this is because digitalisation, for all its potential, often leads to an emphasis on technical efficiency and precision, sometimes at the cost of the more humanistic, cross-disciplinary creativity that once defined architectural genius.

Instead of serving as a bridge for polymathic collaboration, modern and current tools and technologies have, to some extent, perpetuated the trend towards specialisation. Architects now often work in silos, their tasks segmented into specialised domains of expertise. This has diminished the opportunities for the kind of interdisciplinary exchange that was central to the Renaissance approach. For example, while an architect today may be proficient in digital design and understand structural engineering principles, the opportunity to delve deeply into the philosophical or aesthetic implications of their work - qualities that would have been integral to Renaissance architects - is often lost. The very nature of digital tools, with their focus on efficiency and predictability, encourages a kind of professional compartmentalisation that limits the possibility of engaging in the broader intellectual exploration that polymathic architects once embraced.

We currently stand at a pivotal moment. Despite these challenges, the opportunity and potential for a revival of polymathy in architecture is palpable, but it remains largely unrealised. We stand in an era where, more than ever, the tools to synthesise knowledge across disciplines are available. The vast proliferation of online resources, academic literature, and digital platforms offers architects unprecedented access to a variety of fields - ranging from environmental science and technology to philosophy, sociology, and the arts. Yet, for all of this access, the field has to fully capitalise on the opportunity to merge these disparate areas of knowledge in the way that Renaissance architects did. The challenge is not in the availability of information but in the capacity to integrate and apply that knowledge holistically.

It is important to appreciate that there are very real limitations concerning the speculative nature of this topic. This is largely due to the forward-thinking elements such as AI, the speed of technological advancements and the unknowns of the future digitalisation era. Moreover, this paper is based on the understanding that polymathy is a positive constituent within creativity. This could therefore mean an unintentional bias towards the need for polymathy to be part of a newwave Renaissance. The research relies heavily on secondary sources such as academic papers, books, and case studies, potentially overlooking primary data such as interviews or surveys from architects, educators, or students.

For future work on this topic, exploring how architectural education can better integrate multidisciplinary learning will ensure that emerging architects are equipped and wellpractised in the skill of effectively utilising multiple practices when working. This could be achieved by investigating pedagogical models that prioritise the critical thinking skills and intellectual curiosity of the individual opposed to blanket briefs that limit the creativity of the students. Gathering primary source data from those currently working in and/ or studying the subject of architecture would be beneficial. Furthermore, this work might explore the societal and cultural impacts of architecture by showing students the impact that buildings have on communities and people’s emotions about the built environment. All of this would allow the students to open their minds when designing and consider that their projects are not just generic algorithm-sorted modules but should be, in a sense, works of art, which are bespoke to the client and the needs of the surroundings. Also by encouraging them to ask questions such as, how does this influence the lived experience of spaces? What are the long-term implications for cultural identity and the role of architecture as a medium of human expression? By addressing these areas in the immediate future, it is ensured that architecture will remain a discipline that embodies both technical innovation and timeless humanistic values. Surely, the end goal is not to reject digitalisation but rather to shape and mould it in a manner that creates new pathways for students and future architects to become as multifaceted and inspiring as the society they serve.

Ahmed, W., 2018. The Polymath: Unlocking the Power of Human Versatility. New York: Wiley. Alberti, L.B., 1435. On Painting. Florence: Leon di Bartolommeo de’ Alopa. Alberti, L.B., 1485. On Architecture (De re aedificatoria). Florence: Antonio di Bartolomeo Miscomini. Alberti, L.B., 1733. A Parallel of the Antient Architecture with the Modern. London: Edward Owen. Allen, E., 1985. Design and Construction: The Architect’s Role. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Allford, S. 2021. Memo to Members. Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved from Architecture.com Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE), 2018. The changing role of the architect in the 21st century. N/A Azhar, S. 2011. Building Information Modeling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 11(3), 241-252.

Baker, A. 2015. The Future of Knowledge Work: Specialization or Generalization? Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(2), 134-145. Burke, P., 2020. The Polymath: A Cultural History from Leonardo Da Vinci to Susan Sontag. New Haven: Yale University Press. Buchanan, P., 2012. A new agenda for architectural education. The Architectural Review. London. Calatrava, S. 2011. The Architecture of Santiago Calatrava: Art, Science, and Engineering. London: Thames & Hudson.

Carpo, M., 1998. Architecture in the Age of Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Carpo, M., 2011. The Alphabet and the Algorithm. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. da Vinci, L. 1883. The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Edited by J.P. Richter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 46. Eck, C. van, 2010. The legacy of the Renaissance architect. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 69(4), pp.451–464.

Frampton, K. 2007. Architecture and Identity: The Construction of European Architecture. London: Academy Editions. Gang, J., 2019. Designing for Learning: The California College of the Arts. In: N. Spiller & N. Clear, eds. Educating Architects: How Tomorrow’s Practitioners Will Learn Today., pp. 49-67. London: Harvard University Press.

Gardner, H. 2011. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. 3rd ed. New York: Basic Books.

Groat, L. & Wang, D., 2013. Teaching design thinking: Expanding horizons in architectural education. Journal of Architectural Education, 67(2), pp.285–294.

Hernandez, L., & Potvin, A. (2021). Architecture and the Digital Turn: Redefining Creativity and Practice. London: Routledge. Hollins, P., 2020. Polymath: Master Multiple Disciplines, Learn New Skills, Think Flexibly, and Become an Extraordinary Autodidact. n.p.: Peter Hollins.

Kaufman, J.C., Beghetto, R.A., Baer, J. & Ivcevic, Z., 2010. Creativity polymathy: What Benjamin Franklin can teach your kindergartener. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(4), pp.380–387.

Kolarevic, B., 2003. Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing. London: Taylor & Francis. Mallgrave, H.F., 2010. The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. McGrath, B., 2015. Learning by doing: Architecture and polymathy. AD Architectural Design, 85(2).

Pallasmaa, J. 2012. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley. Pringle, J. 2023. ‘RIBA responds to ARB’s Tomorrow’s Architects consultation,’ RIBA. RIBA. 2023. (Royal Institute of British Architects), 2024. Future Trends Survey Reports.

Root-Bernstein, R. and Root-Bernstein, M., 2017. Sparks of Genius: The Thirteen Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Ruhl, C., 2016. Polymathy in architecture: Rediscovering the master builder. Architectural Theory Review, 21(1), pp.23–36. Schön, D., 1983. Learning to think like an architect: Design, education, and the future of practice. Journal of Architectural Education, 37(1), pp.2–9. Spiller, N. & Clear, N., eds., 2014. Educating Architects: How Tomorrow’s Practitioners Will Learn Today. London: Thames & Hudson. Till, J., 2009. Architecture Depends. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vitruvius, 1914. De Architectura. Translated by M.H. Morgan. London: Harvard University Press. Wilson, D. and Anderson, J., 2019. Architecture and the Age of Algorithms: Creativity in the Digital World. London: Thames & Hudson. Wulf, A., 2015. The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science. New York: Knopf.

01. Albert Einstein’s Bookplate

A figure standing on the top of a mountain surrounded by a star filled sky. Made by the artist Erich Brisson.

02. The Vitruvian Man c.1487/90 Accademia, Venice.

03. RIBA & ARB

Logos for the Royal Insttute of British Architects and the Architects Registration Board

04.Art Magna Lucis Et Umbrae’ This chart is taken from the book ‘Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae’ which was published in 1646 by the Jesuit scientist and inventor, Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680)

05. Metastasis Bars 309 to 314, 1953-1954 Image: Courtesy of the Xenakis family

06. Tadao Ando, Church of Light, 1989. Image: Photograph © Copyright Adam Friedberg.

07. Shots of Old-School Pre-CAD Drafting Pools Core 77, Rain Noe (2018)

08. Shots of Old-School Pre-CAD Drafting Pools Core 77, Rain Noe (2018)

09. ARB proposals for a new Architects Code - Designing Buildings (Designing Buildings Wiki)

10. Aughtman’s Square 1 SPILLER’S WORLD (2011)

11. Ga-twistedchrist SPILLER’S WORLD (2011)

12. Wheelbarrow with Expanding Bread, Neil Spiller