Jacques Callot

I Balli di Sfessania I Gobbi

The Noblesse

1620-1623

November 2025

I Balli di Sfessania I Gobbi

The Noblesse

1620-1623

November 2025

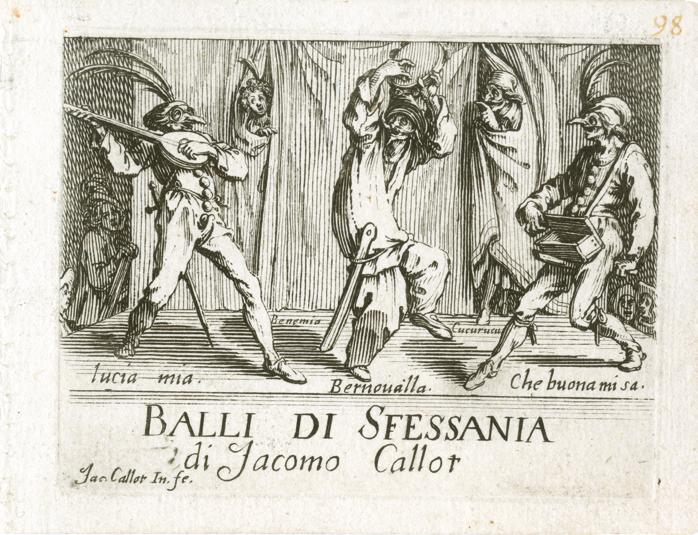

Created after Jacques Callot’s return to Nancy around 1620, these three complete series of etchings rank among the most iconic works by the artist from Lorraine. Influenced by his time in Florence – where he likely produced most of the preparatory sketches – these prints fuse distinctly Tuscan elements (notably the commedia dell’arte themes in the Balli di Sfessania) with popular and grotesque imagery (the Gobbi), and figures that blur the line between comedy, portraiture, and fashion illustration (the Noblesse).

With realistic detail, ornate composition, and a satiric tone, each series offers a distinct form of social commentary. In celebrating both theatrical performance and the poetry of everyday life, Callot’s prints reflect two key elements of the Baroque Zeitgeist: a love for spectacle and entertainment, and a deepening interest in the individual human figure.

Though rooted in the artist’s imagination, these series are also vital documents of the intersection between visual culture and the dramatic arts in the early 17th century – linked by a central thread running through Western modernity: theatricality.

Among Callot’s most celebrated achievements, these etching series are essential to understanding the visual and theatrical culture of early 17th century France and Italy. Likely sketched between 1615 and 1617 during his stay in Florence, the etchings appear to have been completed after his return to Nancy, as suggested by the paper’s watermark – an angel or double C with a cross of Lorraine.

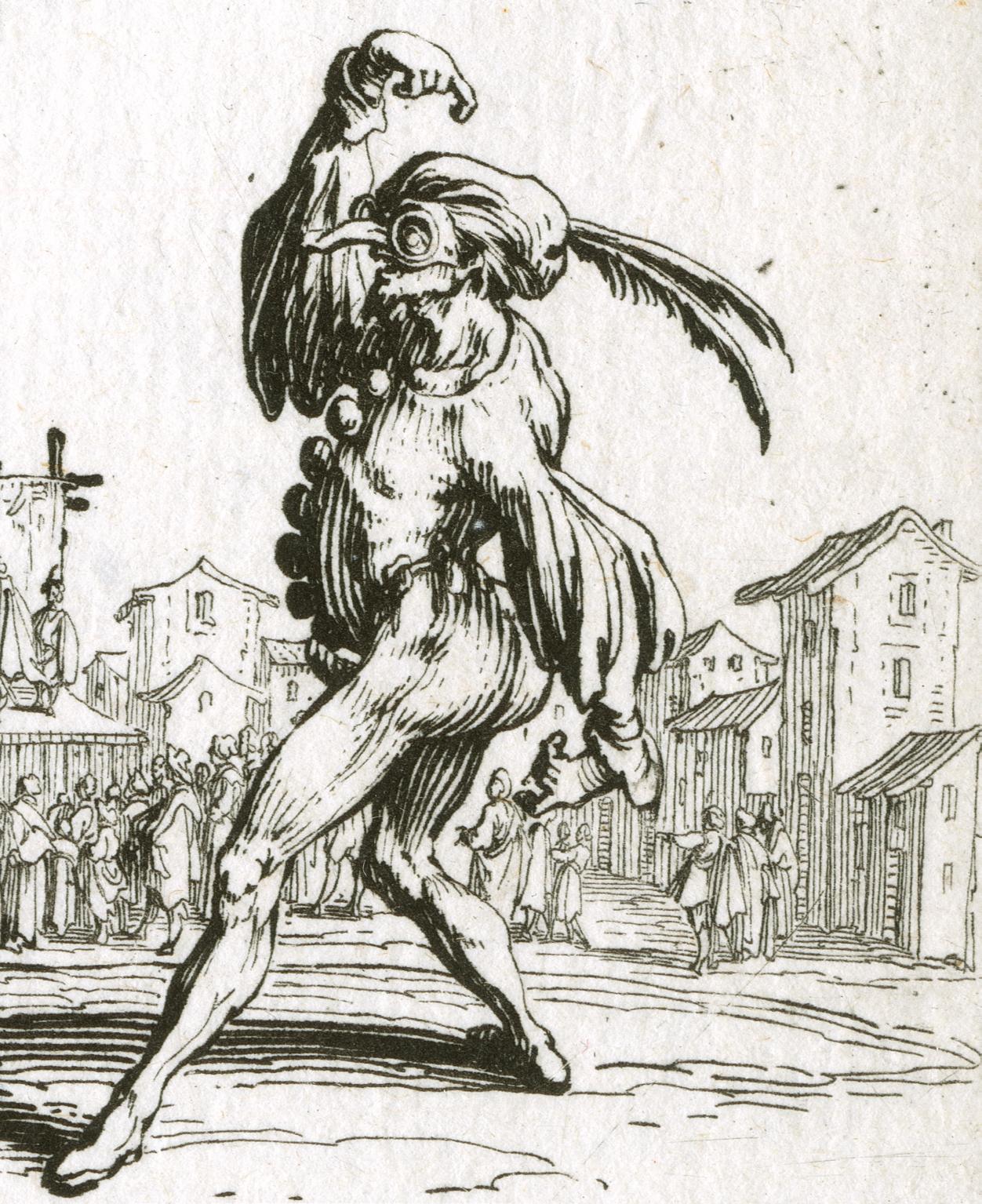

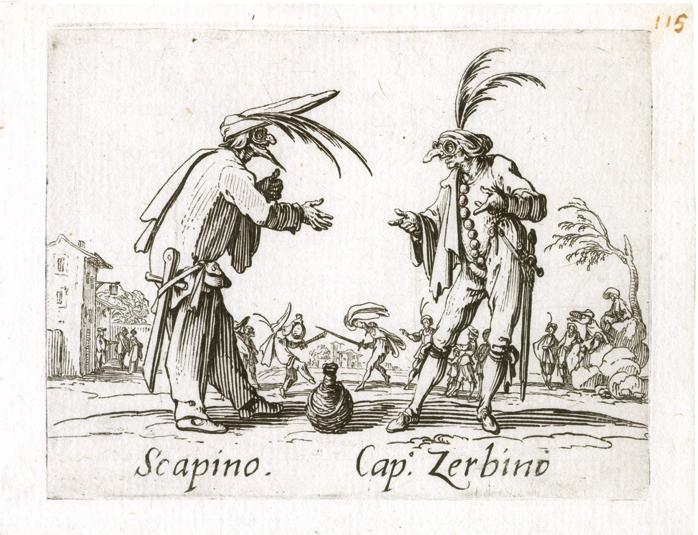

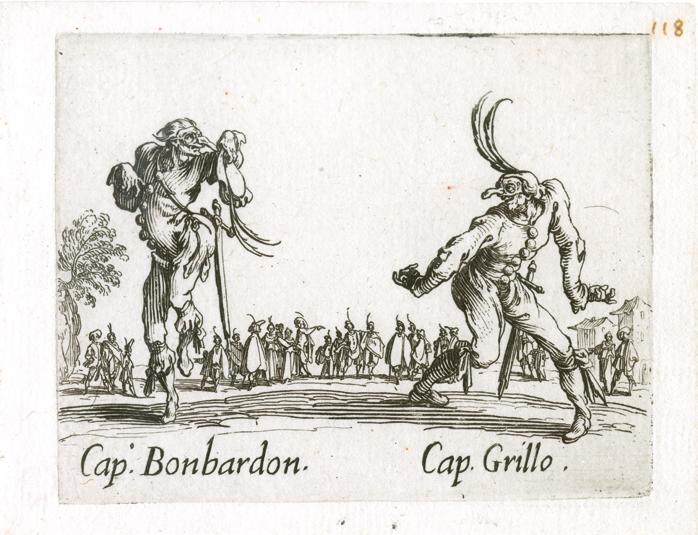

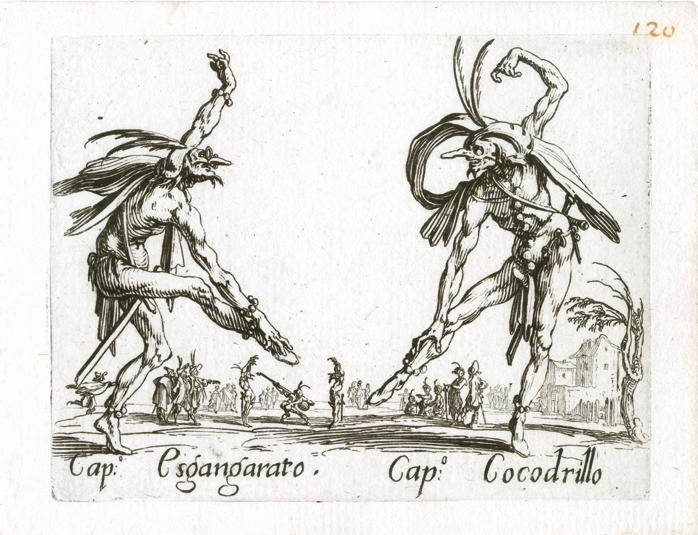

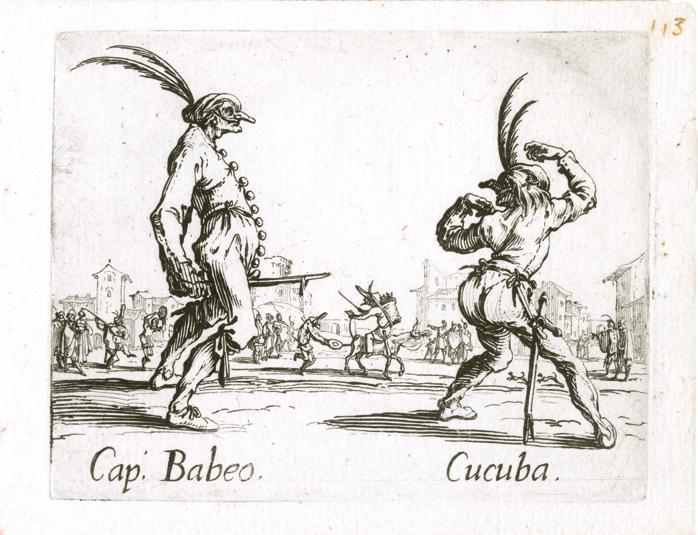

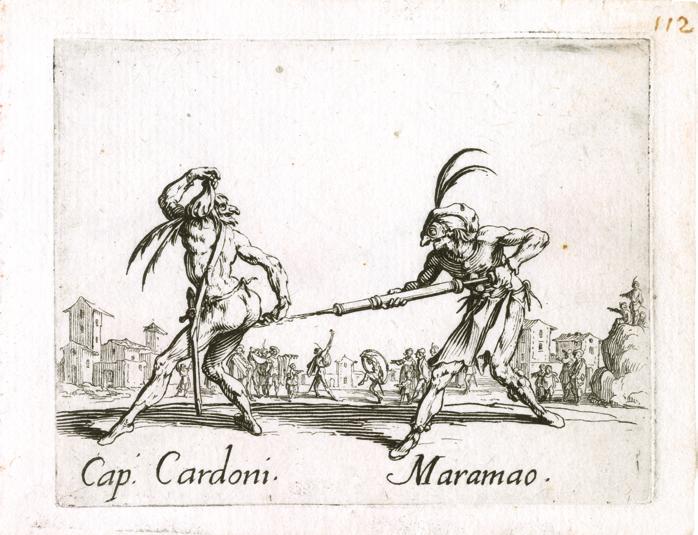

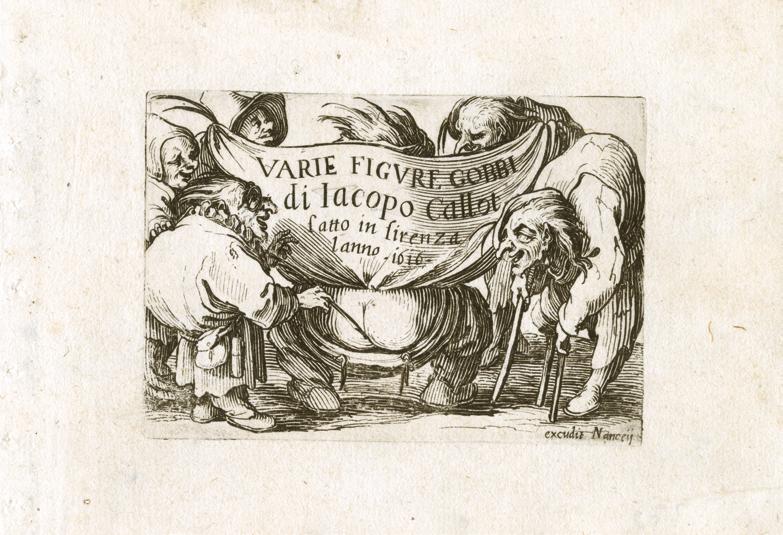

The Balli di Sfessania illustrates scenes from commedia dell’arte, featuring its most iconic characters. The Gobbi – meaning “hunchbacks” in Italian – depicts grotesquely deformed dwarfs, who historically performed at courtly festivities and public celebrations. Callot likely

encountered such figures in Florence, but he exaggerated their traits for dramatic effect. The etchings, though produced later in Nancy, blend faithful observation, idealized memory, and fanciful imagination.

In the Noblesse series, printed on Troyes paper (common in eastern France), cultural influences intermingle, complicating the identification of its subjects. Listed in Callot’s posthumous inventory as ennobled members of the bourgeoisie (and thus members of the Duchy’s elite) it remains unclear whether these figures represent his acquaintances, relatives, or anonymous archetypes.

Combining speech and gesture, the expressive vocabulary of commedia dell’arte actors was gradually codified in Italian treatises, though the genre itself was rooted in improvisation. This improvisational spirit animates Callot’s Balli di Sfessania, which captures the gestural flair and bodily language of its characters. While not strictly documentary, these etchings vividly suggest the movements and styles specific of early theatrical performance, offering clues for reconstructing the essence of live pantomime.

Reflecting the humanist idea that art should imitate nature – not merely other art – Callot’s etchings embrace the expressive freedom of the body. The actors in the Balli perform rhythmic, mimetic dances reminiscent of medieval jesters, whose gestures had long been codified. These figures – Pantalone, Harlequin, Pulcinella – are depicted in exaggerated dance postures, evoking a grotesque, fantastical world.

In the Gobbi, similarly distorted bodies and absurd posters accentuate the dysmorphic grotesque. Meanwhile, the Noblesse figures – engraved in the same style as Callot’s Great Apostles – take on an ironic gravitas, lending a subtle satirical undertone to what initially appears as straightforward social portraiture.

The Balli series features stylized mock battles – duels that resemble dances more than combat –echoing medieval traditions of theatrical swordplay. Examples like Cap. Cardoni and Maramao reveal a performative choreography steeped in parody. In the Gobbi, too, characters brandish swords and musical instruments alike, flailing them in the air and amplifying the absurdist tone.

Most figures in the Balli are set in pairs, highlighting a choreographic interplay and theatrical dialogue. In contrast, the Noblesse and Gobbi often feature solitary figures that emphasize costume and individual expression. The compositions of the Balli are built on symmetry

and contrast, with each partner accentuating the other’s excessive quirks, in the playful, provocative spirit of comic theatre – as seen in Cucurogna and Pernovalla , Fracischina and Gian Farina, and Scaramuccia and Fricasso, among others. Only the frontispiece of the Gobbi includes multiple figures, grouped under a cartellino bearing the work’s title, date, and signature. Yet even this introductory image veers into scatological and anti-religious satire, with a punning reference to “Huguenot” and an exaggeratedly exposed backside.

Through both visual and verbal jokes, the etchings provoke laughter via a form of earthly, realistic comedy. Peasants, courtiers, and rustic villagers urinate, defecate, expose themselves, gesture obscenely, and spit – injecting a crude, everyday vitality into the satire. Gesture and posture become key vehicles of caricature and symbolic force.

Callot’s attention to gesture and pose mirrors dramatic conventions codified in literature and embedded in contemporary visual culture. His characters – musicians, dancers, braggarts, soldiers, capitani – draw from the Italian theatrical tradition and are easily identifiable by their costumes. Embellished with doublets, brocades, embroidery, ruffs, felt hats, and breeches, the figures are richly costumed, their sartorial excess integral to their role.

In the more refined Noblesse series, the figures resemble those in a costume book, continuing the tradition of Abraham van Bruyn and anticipating Abraham Bosse. Minute details – lace, fur, jewelry – especially on the women, are so finely rendered that the outfits themselves seem to become the true subject.

The mask, however, remains the most potent theatrical tool. It conceals identity, enabling greater freedom in gesture and speech while shifting focus to physical performance. Descended from ritual and tied to specific social archetypes, masks signal familiar caricatures and collective cultural associations. They transform actors “speaking statues,” as critiques described them. Traditionally, only elderly and servant characters wore masks, while lovers and female roles did not – a convention Callot honors, further underscoring his sensitivity to theatrical codes and customs.

The decorative dimension of Callot’s series contributes significantly to their interpretive richness. In the Balli di Sfessania and Noblesse, expansive open-air backgrounds serve as theatrical spaces in their own right, seamlessly connecting performance and nature. Rather than mere embellishment, these backdrops often host secondary performances – mimed, danced, or acted – within loosely drawn architectural frames suggestive of stage design.

In many cases, the viewer is no longer outside the scene but represented within it, drawn into the performance as a participant. In the Balli series especially, background comic vignettes add narrative depth, enhancing the symbolism of the main subject.

The ambiguous geography – blurring Italy and Lorraine – further complicates the scene. In La Dame masquée from the Noblesse, the architecture is so indeterminate that it could be either Florentine or Lorrainian. This ambiguity seems intentional, echoed in the presence of a mask – the only one in the series – hinting at uncertainty of identity and place. In Razullo. Cucurucu from the Balli, a second stage is depicted in the central background, where dancers perform for an admiring crowd. Their layered arrangement offers a visual counterpoint to the main action, merging theatre, comedy, portraiture, and genre scene. Callot thus blurs not only the lines between viewer and performer but between artistic categories themselves.

Callot’s etchings were instrumental in the emergence of caricature in Western art. Straddling Mannerism and the Baroque, he merged grotesque traditions of the previous century with post-Tridentine secularism. No longer an end in itself, the imitation of nature became a springboard for transformation – elevating the mundane into theatrical spectacle. In the Balli di Sfessania and Gobbi, the human body is warped, exaggerated, and deconstructed, breaking from naturalism to embrace metaphor and satire. These caricatural distortions aren’t merely stylistic; they function as visual arguments – critiques of social types, artistic conventions and European cultural norms.

Callot also obscures the lines between sacred and profane: in the Noblesse, bourgeois subjects are treated with the grandeur of saints, their dignity undercut by the absurdity of this elevation. Born of his Florentine experience, Callot’s vision reflects a cynical view of a culture obsessed with refinement and artifice. Back in Lorraine, he fused irony, lyricism, and theatricality in ways that resonate with contemporaries like Filippo Napoletano and Giovanni da San Giovanni. His works occupy a space between social typology and caricature of the human condition; some, like the sag-bellied figure in the Gobbi series, may even be self-referential.

Bursting with exuberance, flirtation, quarrels, and vulgarity, these three series – conceived during the same period – capture through Callot’s “theatrical eye” a spirit of derision central to 17th century art. Though shaped by distant worlds – Tuscany and Lorraine – they are united in their satirical, grotesque vision of human behavior, laying the foundation for caricature as a popular art form. By transforming the anecdotal into aesthetic statement, Callot created lasting visual archetypes. These masterpieces of visual satire endure as vivid chronicles of courtly and theatrical life, driven by a rhetoric of exaggeration that remains as striking now as it was then.

Etchings (24) on laid paper, ca. 1621-1622

Plates ca. 73 x 95 mm

Reference Lieure 379-402, first state of two (first printing of three)

Literature Paulette Choné (ed.), Jacques Callot, 1592-1635, exh. cat., Nancy, Musée historique lorrain, 1992, cat. nos. 137-170

Provenance Private collection, USA

Condition In very good condition

Etchings (21) on laid paper, ca. 1621-1622

Plates ca. 65 x 85 mm

Reference Lieure 279 and 407-426, first state of two

Literature Paulette Choné (ed.), Jacques Callot, 1592-1635, exh. cat., Nancy, Musée historique lorrain, 1992, cat. nos. 171-194

Provenance Private collection, France

Condition In very good condition

26 • L’Homme s’apprêtant à tirer son sabre

33 • Le Duelliste à l’épée et au poignard

34 • L’homme au gros ventre orné d’une rangée de boutons

35 • L’homme au gros dos orné d’une rangée de boutons

36 • L’homme au ventre tombant et au chapeau très élevé

•

•

Etchings (12) on laid paper, ca. 1620-1623

Plates ca. 143 x 93 mm

Reference Lieure 549-560, only state (except Lieure 551, first state of two)

Literature Paulette Choné (ed.), Jacques Callot, 1592-1635, exh. cat., Nancy, Musée historique lorrain, 1992, cat. nos. 305-316

46 • La Dame à la petite coiffe relevée en arrière

48 Le Guerrier au chapeau orné d’une grande plume

47 • Le Gentilhomme qui salue tenant son feutre sous le bras

49 La Dame de profil ayant les mains dans son manchon

50 • La Dame coiffée d’un grand-voile et à la robe bordée de fourrures

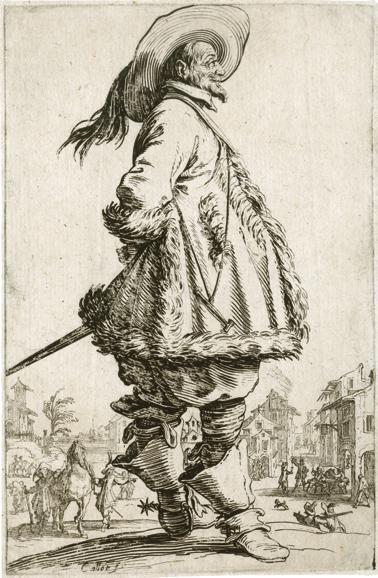

52 L’Homme au manteau bordé de fourrures tenant ses mains derrière le dos

51 • Le Gentilhomme au plastron de fourrure

53 La Dame à la grande collerette et à la coiffe retombant en arrière

54 • La Dame à l’éventail

56 Le Gentilhomme aux mains jointes

55 • Le Gentilhomme enroulé dans son manteau bordé de fourrures

57 La Dame aux masques

Catalogue entries

Charlotte Lange

Design

Tia Džamonja

Editing

Eric Gillis, Catherine Gimonnet, Noémie Goldman & Andrew Shea

Scans & Photographs

Jérôme Allard – Numérisart

Special thanks to (by alphabetical order) Melissa Hughes and her team, Dominique Lejeune and her team, and to all of those who have contributed to the publication of this catalogue.

© Agnews – November 2025