THE MAKING OF THE EMBROIDERY IN A CROSSCHANNEL CONTEXT

David Bates

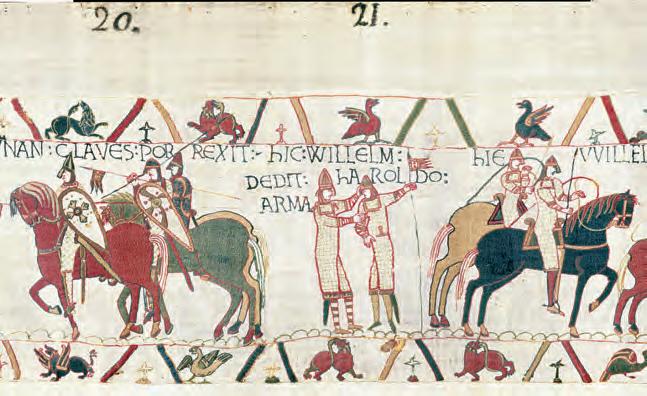

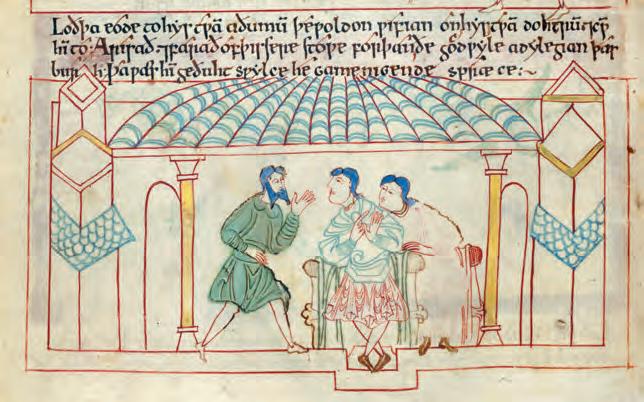

This chapter must begin with the statement that there is no definite evidence about who the Embroidery’s patron or who its designer (or designers) was. All arguments in favour of specific individuals or institutions are therefore only hypotheses. Since it was first proposed by Honoré-François Delauney in 1824, there has been consensus among the vast majority who have studied the Embroidery that its patron was William the Conqueror’s half-brother Odo, who was bishop of Bayeux from either 1049 or 1050 until his death at Palermo in 1097 as he travelled with the First Crusade. Its basis is his prominence on the Embroidery (scenes 35, 43, 44, 54), his position as earl of Kent from 1067, and his extraordinary wealth and ambition.1 During the twentieth century the abbey of St Augustine’s, Canterbury, was identified as the likely place of production, again a conclusion that many have accepted. This was mainly because of the many parallels that were believed to exist between the Embroidery and manuscripts that were known to have been at St Augustine’s and neighbouring Christ Church, the monastery that served Canterbury Cathedral. Odo’s demonstrably close relations with St Augustine’s enabled the collaboration to take place. There are scenes, such as the one showing the gesticulating Odo addressing William about how to prepare the invasion (scene 35), that resemble the portrayal of Lot advising his intended sons-in-law to leave the condemned town of Sodom in the St Augustine’s manuscript known as the Old English Illustrated

52 Scene 35 (detail)

Here Duke William ordered ships to be built Seated to the left of William on his throne, Odo of Bayeux.

Hexateuch (fig. 53). For those who could read the Embroidery’s message, it was arguably making Odo the planner and driving-force at crucial moments. But it has also been suggested that the allusion to Sodom indicated a lack of respect for the integrity of the Normans.2

53 Old English Illustrated Hexateuch Genesis: Lot urging his sons-in-law to flee Sodom C. 1025–50, ink on parchment London, British Library, Cotton MS Claudius B IV, fol. 31v

108 Trajan’s Column: detail of the spiral band of bas-reliefs 107–113, marble, H. 39.50 metres Rome, Trajan’s Forum

are not strict boundaries, but adapt to the images. In the Embroidery, when a scene in the central frieze requires more height, it extends into the space of the border (the soldiers’ spears, for example, often overlap the ‘frame’); and on the column, the upper line sometimes bends to give more breadth to a segment.

There are also analogies in the general pace of the narrative. Episodes are shown in chronological order, with scenes of action or violence – processions of Romans or prisoners (on the column), for example, or groups of horses ready to enter battle (on the Embroidery) – alternating with quieter episodes, such as building work or meals.

The themes depicted are also very similar. Naturally they include all the motifs related to war: soldiers preparing for battle, negotiations, the attack itself, pillaging, the dead. The preparations are shown in considerable detail. On the column, we see the construction of fortresses and ramparts, and in the Embroidery, the Normans build a motte and fortification on English soil, and men fell timber with which others build ships. The horses taken aboard the ships also provide

interesting points of comparison. Trajan’s Column shows the Roman fleet preparing a campaign on the Danube against the Dacians, who are threatening the imperial province of Moesia Inferior. Next to the loading of provisions and equipment, we see a boat carrying four horses of disproportionate size (fig. 109) – a symbolic number to convey the scale of the expedition. This scene also appears in the medieval embroidery (scene 38). Both works show various forms of aggression on the land under attack. A fire scene bears particularly strong similarities, depicting a woman and a child. On the Embroidery, two Normans set an English house ablaze (scene 47); in the foreground, a richly clad woman flees, holding her child by the hand. On the column, horsemen armed with torches set fire to a building represented by a pediment. The woman is also richly clothed but carries the child in her arms; a boat nearby suggests she might be a prisoner about to be taken on board. In both works, the main characters are shown larger in size to differentiate them from the others: this is how William appears on the throne, on the left, in scene 46, and Trajan, next to

the woman. The representation of the ground beneath this fire scene is also an excellent element of comparison. It is an undulating line in the Embroidery, while it is materialised by two lines on Trajan’s Column. This line of the ground which is different to that in other scenes tells the viewer that the episode is taking place in a land that the warriors are conquering by force.

A few generic symbols serve as a kind of visual punctuation, separators forming the transition between two sequences, such as a tree (as in the fire scene) or a building. Or it might be the same figure shown twice side by side; the figure then adopts a different pose to indicate a change of scene. It is important that the spectator follows the direction and continuity of the story; repetition served this purpose in the Middle Ages, just as it did in Antiquity, but even more systematically. A motif, pose or gesture repeated regularly along the length of the frieze serves as a marker. On both the column and in the Embroidery, a leader directing an action can be recognised by his identical gestures, giving orders with a raised arm and pointed

109 Trajan’s Column: Boat carrying horses for the campaign against the Dacians 107–113, marble, H. 39.50 metres Rome, Trajan’s Forum

110 Scene 38 (detail) Here Duke William in a great ship crossed the sea Ship carrying horses.

NARRATIVE STRATEGIES

Xavier Barral i Altet

Once the concept of the work was clear – the overall plan decided, the story written and approved by the patrons – it was time to propose its artistic interpretation: the cartoon, or full-size drawing of the work, laying out the future Bayeux Embroidery. To translate their instructions into a tangible artefact, the artists made use of various techniques and pictorial strategies that would determine the rhythm, sizing, colours, image combinations and physical settings depicted. The result was a continuous narrative, punctuated with separating elements, which would have reflected the collective imagination and visual repertory of the men and women of the time. But in their work we also see references to worlds and figurative conventions of the past, dating back to Late Antiquity and the early medieval period. In the Middle Ages, narratives in images were performative and borrowed from both written and oral storytelling tradition.1 While legend featured prominently, the narrative would often centre on a historical or contemporary hero, praising the person and their deeds (gesta). This is the principle of the chanson de geste, a form of epic poem that was highly popular at the time. The genre served to legitimise power and was extremely codified. When translated into images, every detail was key: a figure’s pose, accessories or the setting of the action would refer the viewer to the social pyramid with which they were familiar.

The first essential requirement in the telling of the Embroidery’s story was to indicate the time in which the narrative was taking place, to distinguish it from the date of execution. This indication is sometimes given precisely and directly, through the depiction of a historical

128 Scene 26 (detail)

Here the corpse of King Edward is borne to the church of the Apostle Saint Peter

event whose date was known, and sometimes in a more indirect manner. The scene showing Edward the Confessor on his deathbed is a direct chronological marker, as the date of his death is recorded as 5 January 1066 (scenes 27–28). More pointers are required to date other images, such as King Edward’s funeral (scene 26). A man is perched on a sort of gangway between a tower of the royal palace and the roof of the church of St Peter at Westminster. With one hand he hangs onto the tower up which he has probably just climbed, and with the other he brandishes a weathercock on a long rod that he

129 Scene 26 (detail)

A tower of the palace of Westminster and the apse of the church of St Peter.

130 The Lanalet Pontifical Consecration of a church

Between 1031 and 1046 (England, Wessex), miniature Rouen, Bibliothèque Municipale, ms. 368 - A 27, fol. 2v

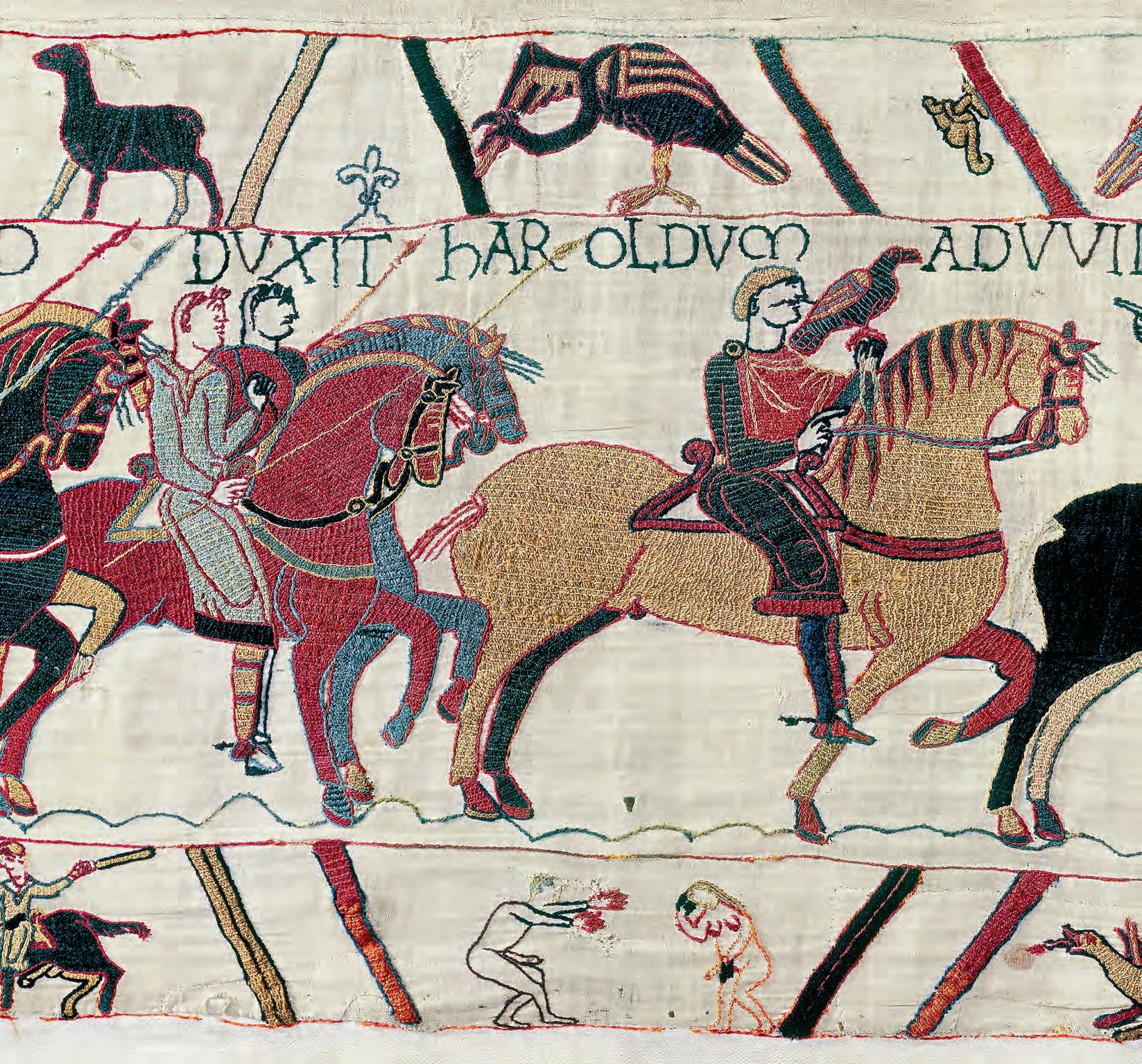

UBI HAROLD DUX ANGLORUM ET SUI MILITES EQUITANT

AD BOSHAM

Where Harold, duke of the English, and his soldiers ride to Bosham

This dignified procession of Harold and his court is undoubtedly one of the most majestic scenes in the whole embroidered narrative, and one of the finest on an artistic level. The story presented in the Bayeux Embroidery addresses the ruling class, the elites. Here, two groups of horsemen walk behind their leader, away from the royal palace. Their size is disproportionate to the small gate through which they have passed. Hounds run before them, as if in a hunting scene. The procession’s movement is harmonious, elegantly paced; the horses’ heads and bodies are graceful, their deportment the result of good training. After the fixed and frontal, almost photographic opening scene, the story here begins to move, from left to right. The image tells us that the story will continue to unfold in the same direction until a second fixed image, right at the end: that of the coronation, which is now lost. Every narrative needs a beginning and an end and a

journey in between, represented here by this group of horsemen parading before our eyes. Riding a male horse and named in the inscription, Harold heads the procession, carrying his hawk with pride. The presence of this bird alone, held on a bare or gloved fist, signifies membership of an elite. The leather straps fixed to its feet are plainly visible. A hawk appears several times in the Embroidery, but only in the first part of the story: it is an attribute of Harold and Guy of Ponthieu in several scenes, before passing to William, to whom it may have been presented as a gift. Hawks were very expensive and owned only by the wealthy in the Middle Ages. They differ from each other in the Embroidery but all have a long tail and short, broad wings; they resemble the goshawk, which inhabits the forest. Hawks were trained for hunting small game; once killed, the quarry was retrieved by dogs. Along with one’s cloak, standard and shield, ownership of one

or several birds of prey was a status symbol. In medieval imagery, it distinguished the lord from the other knights. In images depicting the labours of the months, May is often shown as a rider with hawk on wrist; the bird’s repeated appearance in the Embroidery may indicate the season of spring.

An ornamental tree separates this scene from the next. Domestic and exotic animals as well as composite creatures fill the borders, including two winged centaurs. x.b.i a.

Bosham (West Sussex) is named in Domesday Book as a possession of the family of Earl Godwine of Wessex, who had died in 1053. With the Embroidery only occasionally naming places, its mention of Bosham is arguably surprising. However, we know from other sources that it was an important place for the family and was where they kept their fleet. William of Malmesbury also

names Bosham as the place from which Harold set out across the Channel. Situated to the west of Chichester and to the east of Portsmouth, it was a convenient harbour from which to sail to Normandy, Ponthieu or Flanders. The fact that two of the other eleventh-century sources that mention it, namely, the Vita Ædwardi Regis and the ‘E’ version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, were written at Canterbury supports the argument that the making of the Embroidery involved someone there who was familiar with these histories and with specific knowledge of Harold and his family. It has also been suggested that the inclusion of Bosham is suggestive of irony on the part of the Embroidery’s designer, since it was from there that the Godwine family departed into exile when driven out of England in 1051. This scene on the Embroidery is historically accurate. But it could also be signalling that, despite the way he is presented as a nobleman,

trouble for Harold lay ahead. The fables that start to appear in the lower border at this point are all indicative of trickery and deceit. d.b.

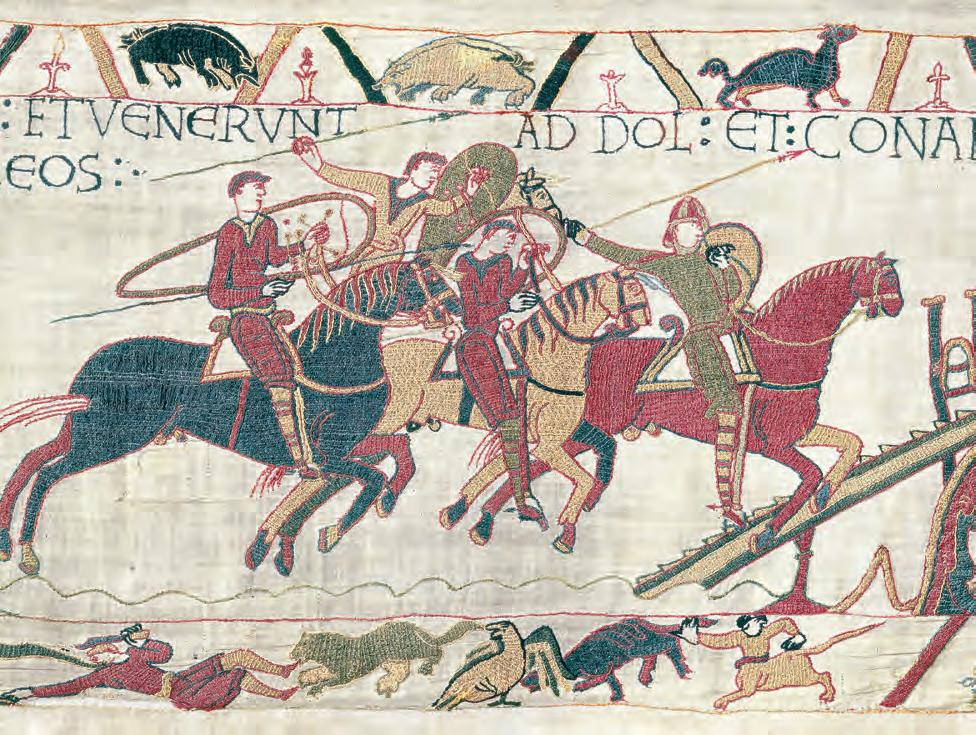

ET VENERUNT AD DOL

And they came to Dol

ET CONAN FUGA VERTIT

REDNES

Rennes And Conan turned and fled

Two singular buildings, among the most evocative in the Embroidery, are illustrated in the main episode of the Breton campaign: the motte castles of Dol and Rennes. Archaeologists have often used these images to explain the construction and visual principles of the feudal mound. This, especially in the Romanesque Early Middle Ages, was a construction of stone or wood erected at the top of a natural, or more often man-made, mound of earth, designed to elevate the building and make it difficult and dangerous to access. A comical but graceful detail corroborates this: Conan II, duke of Brittany, is escaping from the fortress in Dol down a rope that looks as rigid as a slide to the ground on the other side of the motte. The mounds are large and monumental in both cases, but the artist has distinguished between them by using different forms, rounded for Dol, more pointed for Rennes. Animals are shown in front

of each one: birds at Dol, four-legged creatures at Rennes. These are not decorations, as might be found on a cloth or wall painting, but rather suggest the environment and its inhabitants, the nature and animals surrounding the feudal mound, like a bailey. The usual scalloped lines symbolise the ground while thicker, inverted Vs indicate the ditch around the motte. The Dol fortress is quite simple, made up of a square, two-storeyed structure of wood, an outer wall and elevated living quarters. A movable staircase serving as a gangway spans the ditch, leading to a monumental door with a barrier seen from the front. The upper part of the gangway rests on the top of the motte and the bottom reaches to the other side of the ditch, supported by a movable prop on the ground.

The building in Rennes appears more luxurious and robust. The stairway to the entrance is not retractable but is cut directly into

the mound of earth. It leads to crenellated wall, probably made of wood. There is a large gateway in the front, and the castle itself, built of stone, is shown as a domed construction inside the fortified enclosure.

Animals and various monsters inhabit the borders, including a centaur, below the entrance ramp to the Dol fort, hunting with its bare hands, grabbing the tail of some earthly creature. Several types of winged dragons follow. One of them has a very long, rolled tail ending in a floral element, in keeping with the customary decorative and ornamental devices used to represent flora and fauna in the Romanesque period. x.b.i a.

William of Poitiers also mentions William’s attack on Dol. But his account has none of the drama indicated by Count Conan’s escape from Dol by apparently lowering himself down from the ramparts on a rope. Neither William of Poitiers nor the Embroidery are particularly coherent in their accounts, except that from Poitiers we can deduce that William advanced into Brittany at the request of Rivallon de Dol. He does, however, go on to say that Conan was besieging Dol. Hence, the apparent portrayal of Conan escaping from the castle seems to contradict the Embroidery. The problem can be resolved either if the scene on the Embroidery is taken to show that Conan had taken over Dol or as a metaphor for him abandoning the siege. Charter evidence shows that Rivallon and Conan rapidly came to terms after the siege. It is therefore likely that this part of William’s intervention had the limited objective of restoring stability on

the frontier between Normandy and Brittany. William of Poitiers’s account, for all its rhetorical flamboyance, pretty much says this.

This is a scene that is very clearly modelled on an illumination in the Old English Hexateuch, yet another demonstration of the links between the Embroidery and the abbey of St Augustine’s, Canterbury. How far the borrowing was intended to convey a message is, however, unclear since the scene in the Hexateuch represents a Jewish spy escaping from Jericho. It is possible that the designers simply appropriated a good image to illustrate the narrative. d.b.

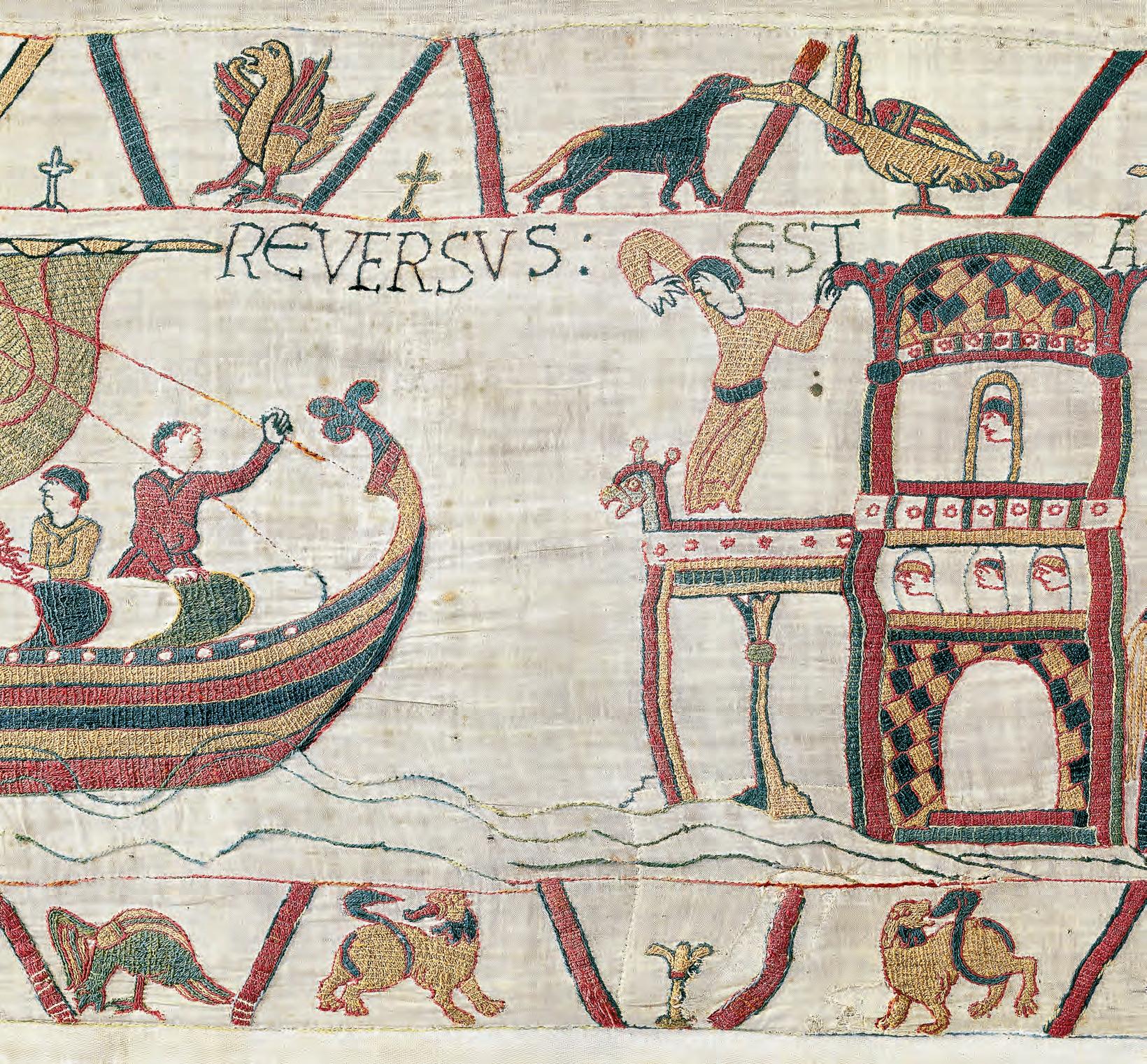

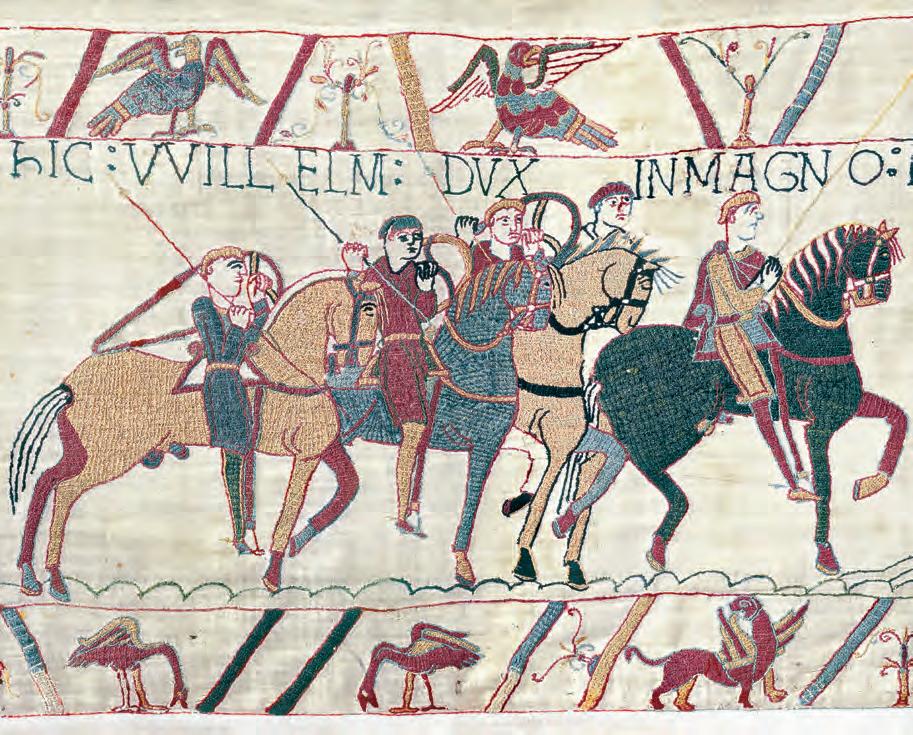

HIC WILLELM DUX IN MAGNO NAVIGIO MARE TRANSIVIT

Here Duke William in a great ship crossed the sea…

… and came to Pevensey

The crossing of the Channel by William’s fleet is spectacularly depicted in the Embroidery, capturing the impact that this departure for war must have had at the time. The poet Baudri of Bourgueil penned a vivid description of the episode in the early twelfth century (see pp. 67–73). In his poem for the Countess Adela of Blois, daughter of the Conqueror, he describes an embroidered hanging similar in every way to the Bayeux Embroidery: ‘Mighty Xerxes could not have gathered a fleet so impressive, / Nor could have built even one ship of comparable size. / This will astonish you more: three thousand keels were assembled; / William manned them all, outfitting all the men. / Not only that: there were separate ships to carry the soldiers, / Others to carry the lords, others to carry their mounts. / Over all these rose the royal ship with its beak all gilded; / No need for it to fear the Channel’s turbulent seas. / From the royal ship’s stern comes a shout:

“cast off the ropes!” / And the ropes are released; all hands tend to their tasks. / Nautical noises start up, a clamour, a wild confusion: / Those left behind on the shore, mothers and wives, are in tears. / This one blesses her man; that maid bids farewell to her sweetheart. / Every girl with her eyes follows the man she loves. / This woman here says a prayer for a happy and speedy reunion; / To Countess Adela / Men and women alike give free rein to their tears. […] If the world’s structure were lapsing, the stars falling from the heavens, / All firm land swallowed up by the voracious sea, / The noise could not be louder, the chaos could not be greater; / Nor could the cries of the crowd top the cries at this scene. / Fleeing the harbour, the ships make haste and gain open water / Gradually the clamour recedes; suddenly all is quiet. / The pilot has already turned to observe the stars and the weather; / All the men on the ships see to their several tasks. / Turning their sails at

an angle, they manage to make good speed, / Finally reach the shore, never touching the oars. / All the ships and the fighters, as well as the names of the fighters / Were to be found on this cloth –could it be only a cloth?’1

The Bayeux Embroidery shows all the stages of the crossing until the landing on the English coast at Pevensey. Before the ships are boarded, William arrives solemnly on horseback, accompanied by a small group. The duke’s black stallion is shown with an erection, probably representing the rider’s determination. William bears a standard to rally his troops as he walks right to the water’s edge. The series of ships that follows exhibits a particularity of the Embroidery: in the Middle Ages, ships were generally depicted with their hulls partly immersed, sometimes hidden from view, sometimes still visible under the water; in the Embroidery, the hulls simply sit on the

water, which is symbolised by more or less parallel, compact, wavy lines creating a sense of movement.

The fleet makes good speed, going by the billowing sails and sailors’ busy activity on board. There are differences between the various vessels: some carry soldiers with their kite shields, others carry men and horses. In some cases, shields are fastened to the bow and stern; other ships display carved wooden figureheads. Smaller boats in the background may be carrying foot soldiers, escorting the main force. Their elevated position gives depth to the image, heightening the visual impression of multiple vessels.

William’s ship is larger than the others and occupies the centre of the scene. The bow and stern are higher and have more spectacular figureheads. The atmosphere on board seems more relaxed and lively discussions are taking place. A sailor is tending to the mast and sails.

Another addresses the group from the bow. The steersman watches the movement in the sails. Perched on the figurehead, a lookout bearing a standard sounds the horn. The mast is topped with a cross, very similar to some of the small crosses in the border, while standards top the masts of other ships. On William’s ship, it would be the cross of the standard that was blessed and sent by Alexander II, pope from 1061 to 1073. William had appealed to the pope after learning that Harold had broken his oath. This papal cross presiding over the expedition serves as a guarantee of the Christianity and justice of William’s undertaking, and confirms the religious legitimacy of the future battle.

The lower border pursues its catalogue of animals and monsters of the earth and air. Under the ship to the left of William’s vessel, a four-legged animal is attacking a bird; this vignette has sometimes been identified

as a fable. The upper border is entirely occupied by the masts and wind-filled sails, except at the beginning of this long scene, showing the solemn procession towards the ships. Here, two elegant birds of prey appear in a symmetrical arrangement on either side of a plant motif. They could be two eagles, in keeping the Embroidery’s designers’ and sewers’ usual practice. But it is just possible that they reference the hawks accompanying the noble figures in the early scenes. Throughout the rest of the story, there will be no hawk at William’s fist. x.b.i a.

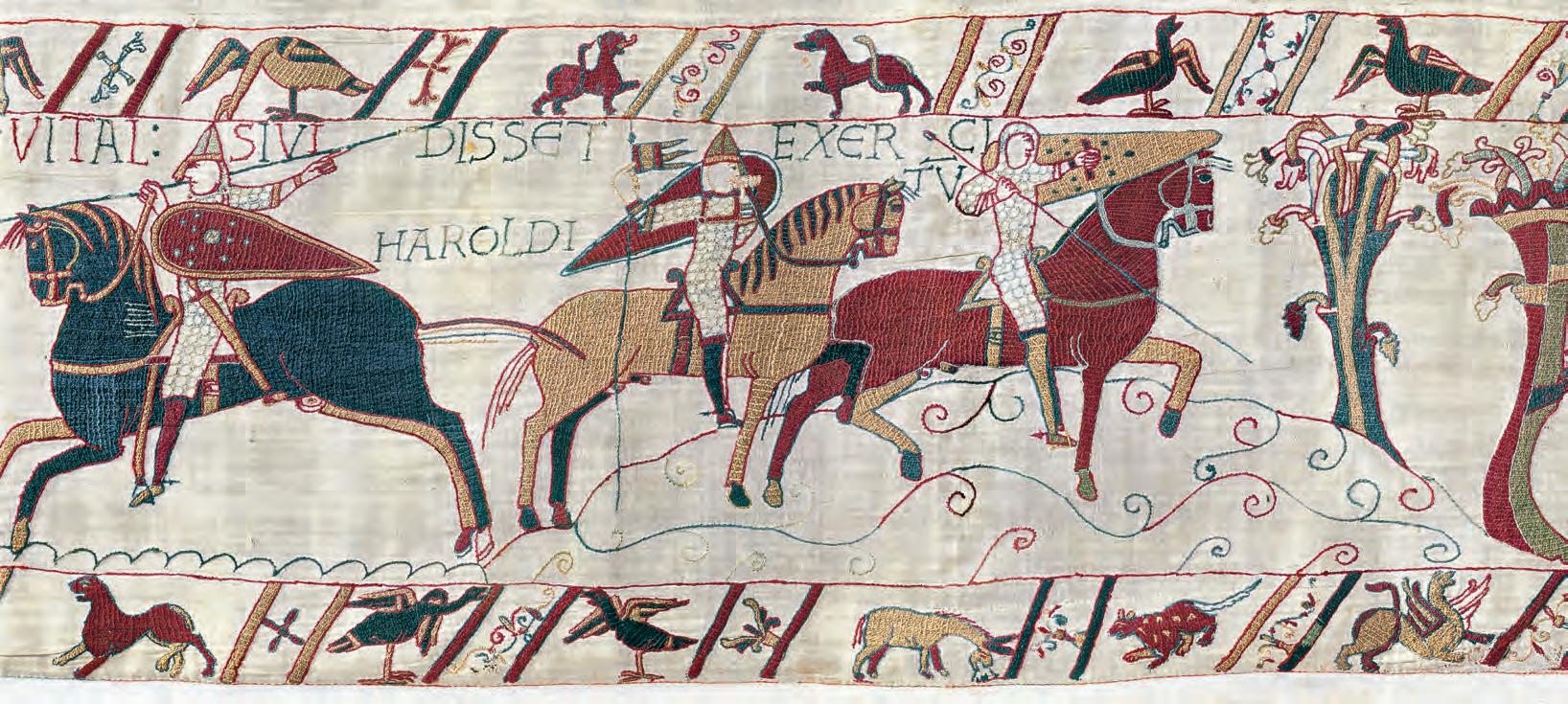

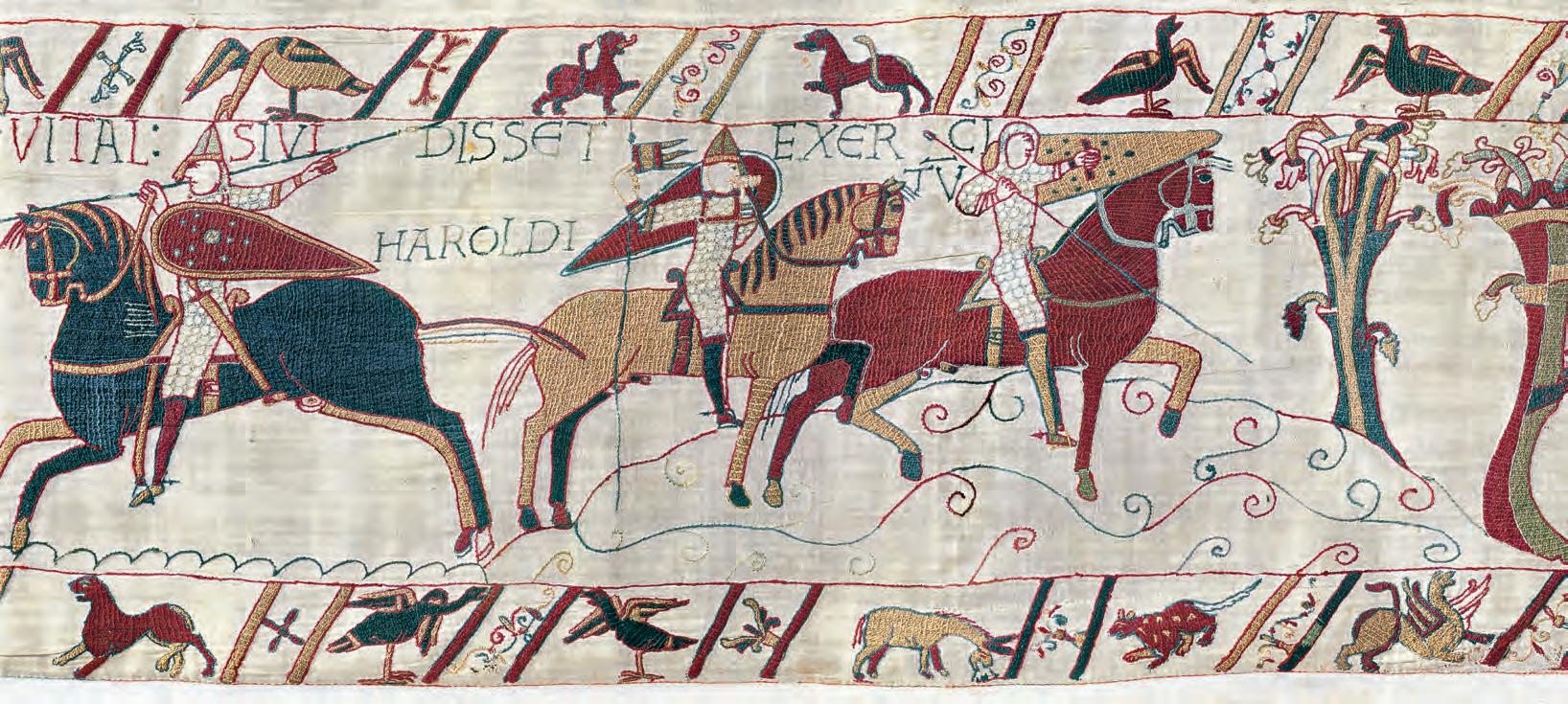

HIC WILLELM DUX

INTERROGAT VITAL

SI VIDISSET EXERCITU[M]

HAROLDI

Here Duke William asks Vital if he had seen Harold’s army

This scene describes the encounter between William and Vital: a magnificent exchange on horseback. The main group is formed by three horsemen wearing coats of mail and helmets with nose guards. William is the duke and warrior, the army leader, who has decided to wage the battle. Here, his gold-coloured mount walks with great elegance, gracefully lifting its left foreleg while appearing to salute by slightly lowering its head. In his right hand, William carries the baton of command, in the form of a club. With the index finger of his left hand holding the reins at the horse’s neck, he points at his interlocutor with authority. The latter is approaching at a gallop on a black horse, armed with a lance. His feet, like William’s, are in stirrups suspended from the saddle. He carries a shield with a boss and ten studs arranged in four parallel lines. This is probably the most common type of shield decoration

in the Embroidery, used indifferently by soldiers of both armies.

The two horsemen speak to each other whilst maintaining a respectful distance. The inscription names William’s interlocutor: Vital. This man is not mentioned in any source from the time, but historians believe he could be a tenant of Odo, bishop of Bayeux; like Wadard, named in scene 41, Vital may have been granted holdings in Kent by Odo. The Embroidery presents him as one of William’s companions in the military campaign. Vital has been sent ahead to observe the Anglo-Saxon army and report back to William. In the manner of an ancient warrior leader, the duke asks Vital if he has seen the army of Harold II of Wessex. The spy gives him details of the war preparations he was able to observe. Behind William, another horseman witnesses the meeting. The inscription does not identify him but it has been suggested that he is Bishop Odo,

who will now bravely accompany William in his military campaign; he carries his baton of office against his right shoulder.

On the right, near a large ornamental tree, two mounted soldiers are surveying the enemy’s movements. Each carries a shield in his left hand, revealing its underside and gripping straps. The more eager horseman in the front is armed with a lance and points his kite shield at the enemy. The second advances more slowly, carrying his shield in a neutral position, pointed backwards, and bearing a standard that he sets on the ground. The banner points in the opposite direction to which the horse is walking, so must be made of a stiff material; if it were made of cloth, it would drop down along the shaft at a standstill, and at a pace its three points would fly backwards. The line of the ground here is unique in the Embroidery, tracing scrolls and undulations suggesting the hilly terrain on which the ornamental tree marks the transition. x.b.i a.

The man being questioned by William is undoubtedly Vitalis of Canterbury, a man about whose life we are very well informed. That he is being asked by William to provide information that was vital to the strategy and tactics to be followed in the forthcoming battle shows that he was someone in whom William had exceptional confidence, something his career indicates was likely to be the case.

Vitalis appears in Domesday Book and related documents written at Canterbury as holding land in Kent of Bishop Odo, St Augustine’s, Canterbury, Christ Church, Canterbury, and Haimo, the Norman sheriff of Kent. In other words, he was closely linked to all the most influential landholders in the shire. Like Wadard, he was a member of the St Augustine’s confraternity. We know from the St Augustine’s Martyrology that the monks prayed for his soul after his death. Even more informative

is a miracle story that appears in the Miracles of St Augustine, written at Canterbury in the later eleventh century by the Flemish monk and distinguished hagiographer Goscelin of Saint-Bertin. Here we are told that Vitalis was in charge of a fleet of fifteen ships transporting stone across the Channel from Caen to build the king’s palace at Westminster and the new abbey church at St Augustine’s. Hit by a terrible storm, the fourteen ships carrying stone for the king’s palace all sank, with only the fifteenth with the stone for St Augustine’s with Vitalis on board completing its journey. The importance of Caen stone for the reconstruction of St Augustine’s is known from excavations on the abbey site, which have estimated that approximately 83% of the stone used came from Caen. Vitalis therefore emerges as a great entrepreneur responsible for a major expansion of the quarries at Caen and an important contributor to the great

building projects started in England soon after 1066. In all likelihood, he was also directly involved in the work on the two great abbeys that William and Matilda had founded at Caen. We know that he founded a church at Canterbury dedicated to the English saint St Edmund, whose cult crossed the Channel to France. His descendants flourished as citizens of Canterbury. The elements in common between his life and those of Turold and Wadard make all three of them worthy witnesses to the narrative of the Embroidery. Vitalis’s remarkable life shows just how his life would have conveyed authority and interest to an audience viewing the Embroidery in the years immediately after 1066. d.b.

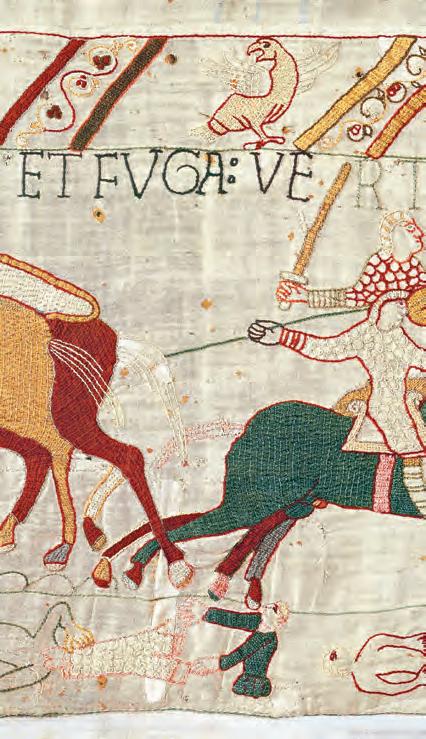

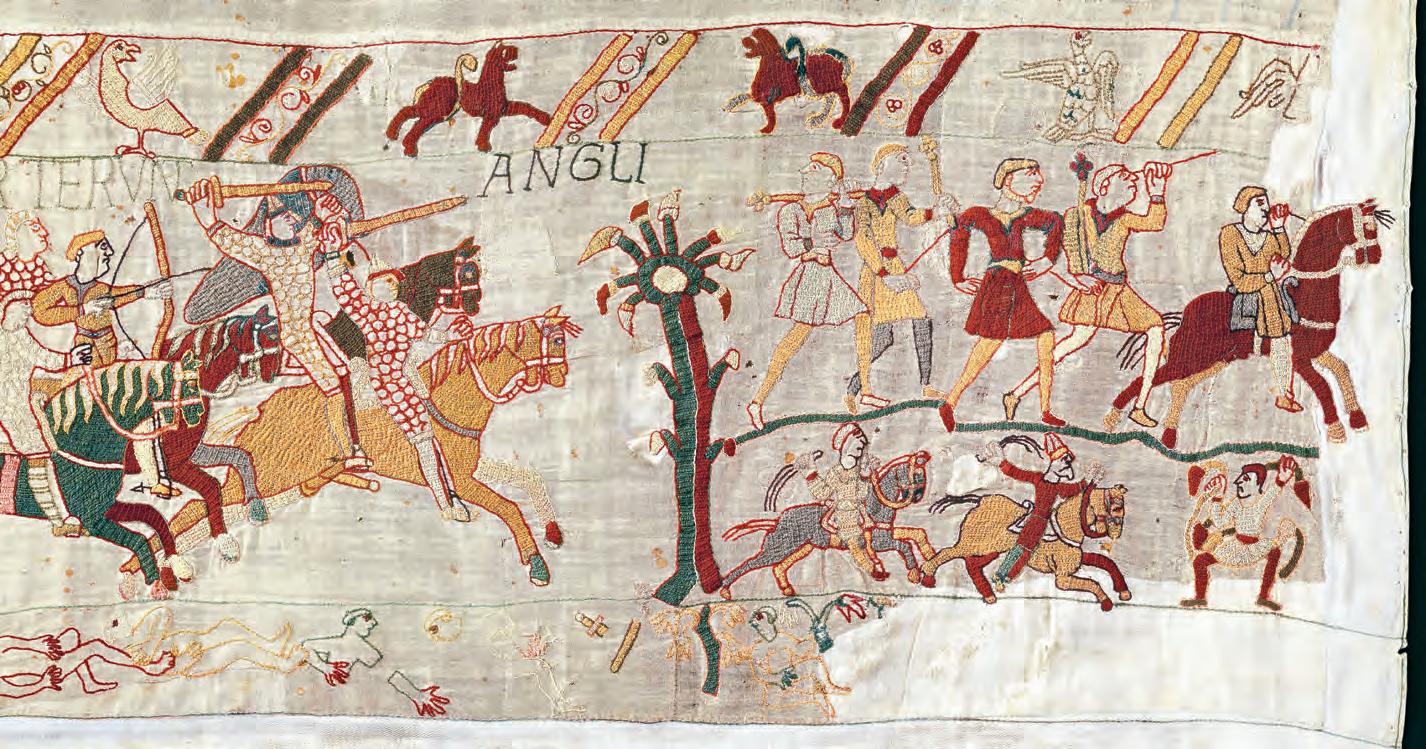

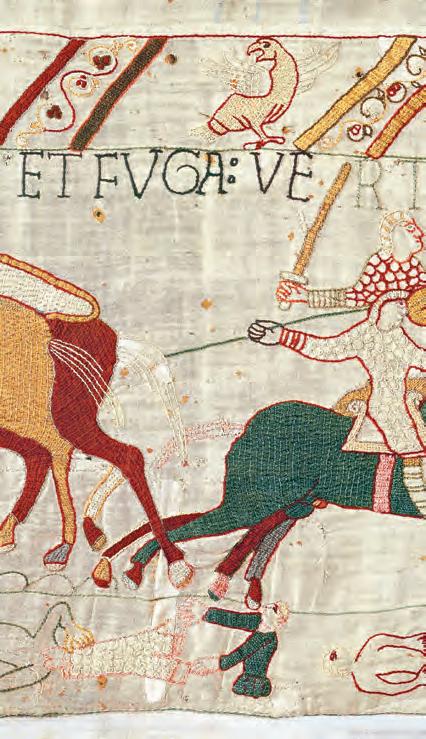

ET FUGA VERTERUNT ANGLI

… and the English have turned in flight

The Embroidery that has come down to us ends here, with the pursuit of the last of the fleeing Anglo-Saxons. Only the Normans remain heavily armed, although some of them have lost their helmet in battle. They are galloping and wielding spears, swords and bows. A tree separates them from the vanquished men, who are depicted on two levels, as in the scene of Edward’s death (27–28). The upper level shows soldiers mostly on foot, some still carrying their battle club on their shoulder. The last one is looking back to see how far he is from their pursuers, like the damned watching the saved with despair and with fear that which awaits them in Romanesque scenes of the Last Judgement. In the lower level Normans are still pursuing civilians. But the authenticity of this part is questionable because it has undergone substantial repairs and alterations.

The final images of the Embroidery have been lost. Accounts by contemporary historians and Baudri of Bourgueil’s text about the embroidered

hanging he saw in the chamber of Countess Adela suggest that they may have shown William’s coronation, on Christmas Day 1066 in Westminster Abbey. Without this final image to conclude the military deed, the Embroidery’s story wouldn’t make sense. The event is described in a poem usually attributed to Guy, a historian who was Bishop of Amiens from 1058 until his death in 1074 or 1075: ‘At the time appointed for the king’s coronation, the magnates of the realm, the people, the dignitaries of the church, and the venerable Witan assemble from all sides for the royal ceremony. From these, to consecrate and at the same time to crown the king, by ennobling the king’s head with a coronet, was chosen the most celebrated of the bishops, a man of distinction, renowned for his goodness. By his order the procession to magnify the Lord was organised, according to the usual and ancient custom, in double file. The monastic order and the clergy with their prelates make for the church of St Peter.

Crosses are borne before the procession of the clergy; and after the clergy follows the episcopal order. The king, escorted by a great concourse of counts and dukes and the applause of the people, comes last. The metropolitan follows with an identical speech in English. The congregation gives assent to both, hails the king and pledges service. It promises subjection with all its heart. The archbishop then turned towards the holy altar and set the king to face him. He summoned all the prelates to join him and, together with the king, they all prostrate themselves [...] The archbishop tells the people to pray and starts the oce proper to the occasion. He recites the Collect, raises the king from the dust, anoints the king’s head with the chrism he pours out, and consecrates him king according to royal rites.’ 8 x.b.i a.

This final surviving scene peters out into a portrayal of some English leaving the battlefield in an apparently orderly fashion. However, much of the

scene has been heavily restored and some of it may be a much later creation. This could well include the unique mounted archer. Its first part shows some more fighting before proceeding to portray William’s army driving the defeated English away. The mutilated corpses in the lower border are presumably a reference both to the horrors of war and to brutality of these final stages of the battle. They may also draw attention to William’s initial decision not to allow the English to bury their dead, an act of punishment from which he appears subsequently to have relented. It is notable, however, that no graves have ever been found on what is believed to be the battlefield.

It is generally thought that the lost concluding section of the Embroidery would have concluded with William’s coronation on 25 December 1066. It is interesting to think about what the intervening scenes might have been. Given the argument that approximately 2.8 metres have been lost, three scenes of the conventionally

accepted length plus the coronation scene would probably once have existed. These could not possibly have contained much, if any, of the narrative of William’s army’s march around the south of London up until the submission at Great Berkhamsted (Hertfordshire) and the subsequent siege of London uniquely described in the Carmen. Canterbury’s submission is a possibility for inclusion. But since the Embroidery’s theme is ultimately William’s triumph over Harold, it may be that Harold’s burial would have been represented. And also that, although William himself was not directly involved, Winchester’s submission and, with it, Queen Edith’s, would have been included.

The Embroidery’s representation of William’s coronation would certainly have been grand. It illustrated his victory over a perjurer and God’s will that he triumph. But how exactly might it have been done? Would it have followed the ‘D’ version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that has Archbishop

Ealdred of York exact special oaths from William before he would crown him? And what would it have made of William of Poitiers’s narrative of the soldiers outside the abbey panicking at the noise of the acclamation within the church and setting fire to neighbouring houses? Would it have anticipated Orderic’s elaboration of this story into a portrayal of a trembling king crowned in the presence of a small number of clergy and monks, everyone else having fled the church? Orderic was later to see it as the moment when the Devil intervened in human affairs to sow long-term discord between the French and the English. Born in England in 1075 of a mixed marriage and sent in 1085 to the abbey of Saint-Evroult in Normandy to become a child oblate and then a monk, he was writing about the world in which he had grown up. This was also the world that created the Bayeux Embroidery. We may think that the thought-provoking ambiguities present from its beginning would have continued to be present right to the end… d.b.

© 2019, 2020, Editio – Éditions Citadelles & Mazenod © 2024, Editio – Éditions Citadelles & Mazenod for this edition 8, rue Gaston de Saint-Paul, 75116 Paris www.citadelles-mazenod.com

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978 2 38611 009 2 Legal deposit (France): March 2024

For the original edition

Editorial director: Geneviève Rudolf

Editorial assistant: Gwenaël Ben Aissa

Translation of texts by David Bates: Christian Vair

Picture researcher: Marion Jouan

Copy editor: Suzanne Madon

Graphic design and layout: Ursula Held

Production: Ingrid Bœringer

Colour separation: EBS, San Giovanni Lupatoto

For the English-language edition

Translation of texts by Xavier Barral i Altet: Alexandra Keens

Copy editor and proofreading: Bernard Wooding

Editorial coordination: Marie Rocamora

Graphic design and layout: Ursula Held

Production: Luc Martin

Printing and finishing: Norprint Artes Gráficas, Santo Tirso

Printed in Portugal in February 2024 on Magno Natural 140g paper made from wood fibre from sustainably managed forests and controlled sources.