ORO Editions

TEMPLES & TOWNS

ORO Editions

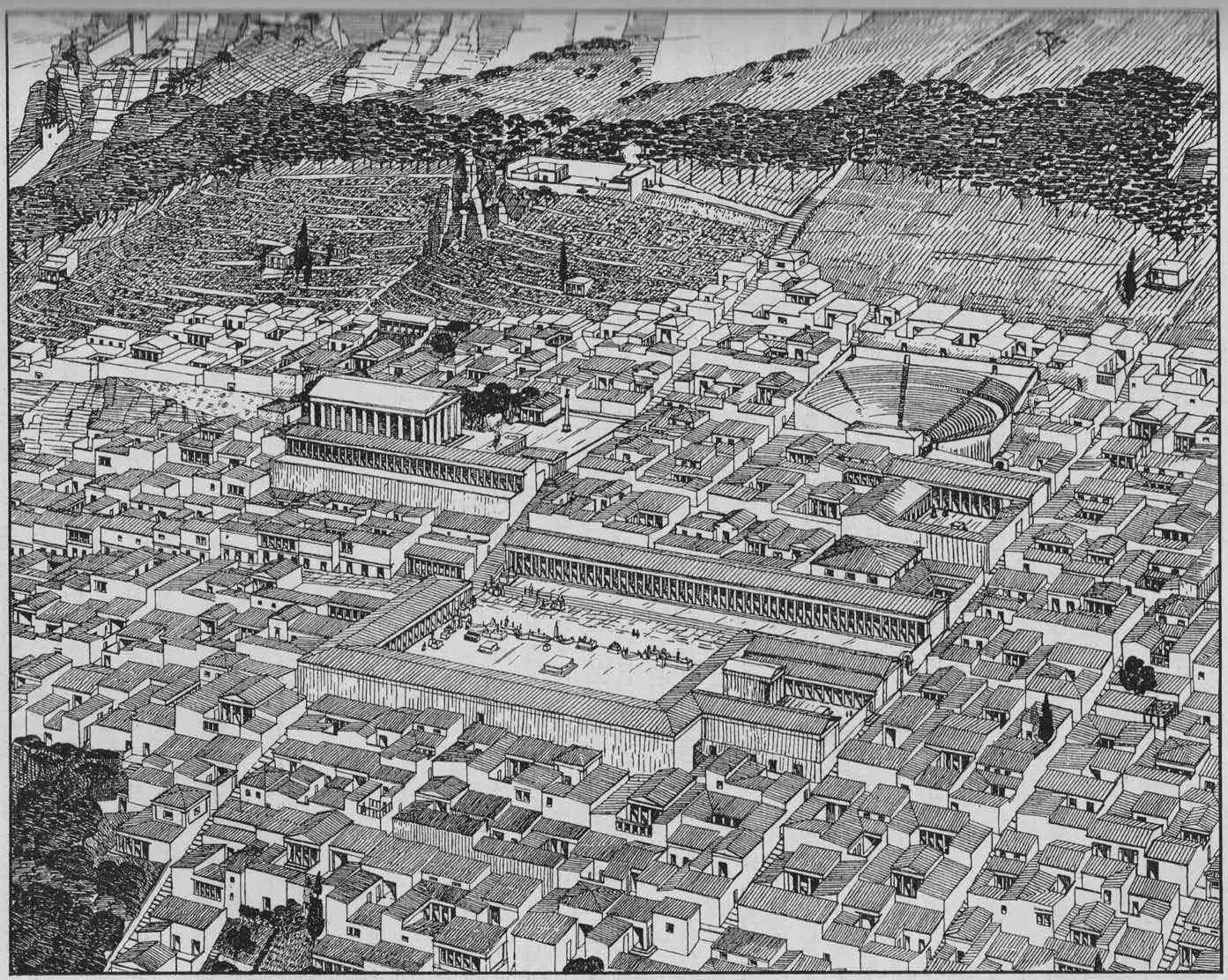

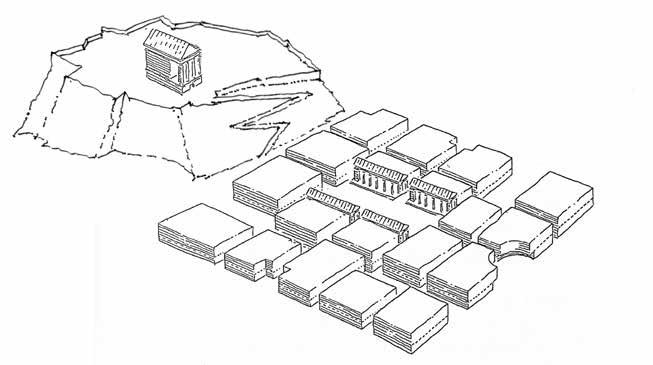

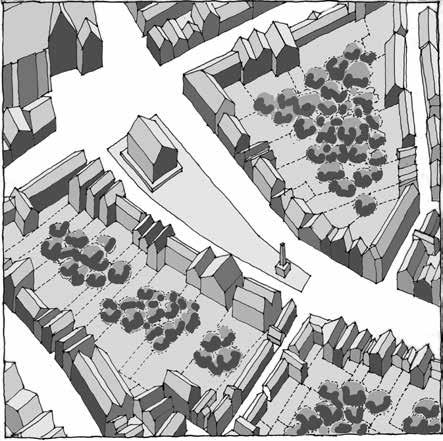

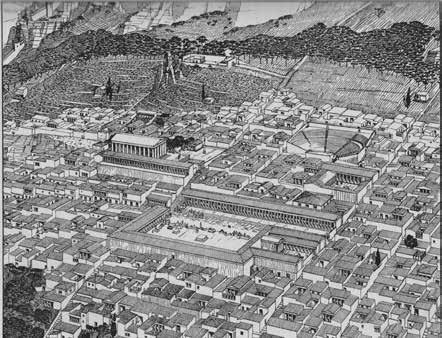

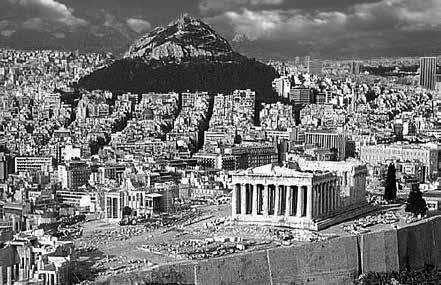

Aerial reconstruction view of Priene, ca. 350 BC

TEMPLES & TOWNS

The Form, Elements, and Principles of Planned Towns

Michael Dennis

Foreword by Steven K. Peterson

ORO Editions

Publishers of Architecture, Art, and Design

Gordon Goff: Publisher

www.oroeditions.com info@oroeditions.com

Published by ORO Editions

Copyright © 2022 Michael Dennis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Author: Michael Dennis

Foreword: Steven K. Peterson

Book Design: Michael Dennis

Project Manager: Jake Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-957183-02-2

Color Separations and Printing: ORO Group Inc. Printed in China.

AR+D Publishing makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, AR+D, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.

A cknowledgments

This book grows out of studies made during the fall of 2009 by students and faculty of the SMarchS Architecture and Urbanism program in the Department of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As such, it follows in a long tradition of informal publications of ongoing research at academic institutions. Most remain as useful “unpublished manuscripts.” Often, however, these studies result in public lectures; occasionally in published articles; and sometimes they are preludes to finished books.

The following people contributed to the initial research: Allison Albericci, Matthew Bindner, Kathleen Dahlberg, Laura Delaney, Chris De Vries, Yashar Ghasemkhani, Theodossius Issaias, Priyanka Kapoor, Amrita Mahindroo, Mahsan Mohsenin, Nathan Prevendar, Eva Strobel, Sagarika Suri, Tony Vanky, Matti Wirth, and Kui Xue.

Copy editing at various stages was done by Judy Feldman, Evan Anderson, and Christie Monroe Dennis. Christie, however, contributed ideas and improvements well beyond what I could ever have imagined. For all the above contributions, I am profoundly grateful.

Michael Dennis Boston, MA 2022

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

For Christie

t emples A nd t owns

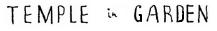

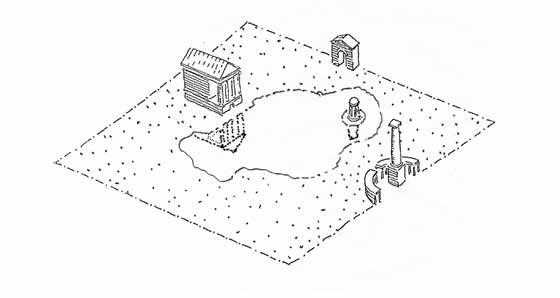

In Classical Greece the most sacred temples were often located on the acropolis, separate from the town. In Hellenistic Greek towns and Roman towns, however, the temples were usually within the town. This condition of reciprocity between architectural monuments and urban fabric remained until approximately the mid-eighteenth century, when important Western institutions began to be expressed as articulate architectural monuments—free-standing icons—often in gardens.

This Neoclassical change in sensibility re-emerged after the frenzy of nineteenth-century city building as the spatial and philosophical underpinning of modern architecture and town planning. Essentially, the city disappeared; architecture became more and more assertive and violent; and the private realm of architecture finally achieved hegemony over the public realm of the city.

During this process, society lost its sense of community and urbanity; staggering amounts of finite resources were consumed; and our planet became so polluted that the damage may be irreversible.

“Temples” without “Towns” is untenable. Both temples and towns are needed. Hence, the title and content of this book.

Illustrations with gratitude and apologies to Leon

ORO Editions

FOREWORD

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

I. THE PREINDUSTRIAL CITY

GREEK CITIES: 800 BC–200 BC

Selinunte ca. 650 BC

Poseidonia (Paestum) ca. 600 BC

Priene ca. 350 BC

Pergamon ca. 300 BC

Assos ca. 200 BC

Miletus ca. 466 BC

ROMAN CITIES: 350 BC–100 AD

Roman Town Planning

Roman Colonies and Castra Cosa 273 BC

Roman Castra

Timgad 100 AD

Florence ca. 50 BC

Verona 89 BC

Turin 27 BC

Aosta 25 BC

Roman Dwellings

Pompeii

Ephesus and Taormina

Roman Fora

MEDIEVAL BASTIDES: 1200–1400

Halls

Monpazier 1284

Grenade-sur-Garonne 1290

Villefranche-de-Rouergue 1252

RENAISSANCE CITIES: 1400–1700

Frontality and Centrality Perspective and Painting Perspective and Architecture

Ideal Cities

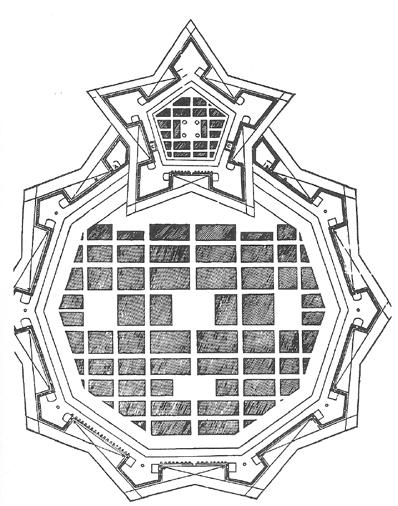

Palmanova 1593–1603

Grammichele 1693 Cartography

Orthogonal Plans

Sabbioneta ca. 1550

Avola 1693

Neuf Brisach 1698

Philadelphia 1683

Savannah 1733

The Laws of the Indies

Renaissance Gardens

BAROQUE CITIES: 1700–1800

Rome and Sixtus V Baroque Gardens and Cities

Versailles

Washington, DC

Noto 1693

Sicily

Lisbon 1756

Edinburgh 1767

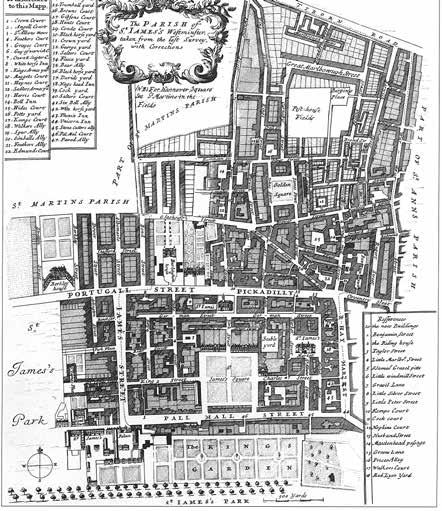

GREAT LONDON ESTATES: 1750–1850

London 1630–1850

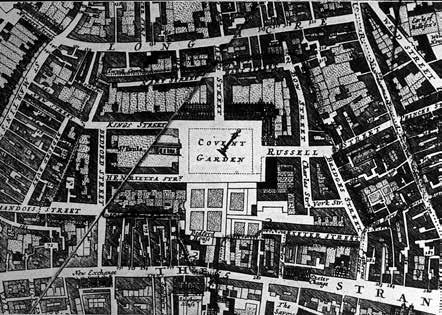

Covent Garden Bloomsbury

St. James Hanover Grosvenor

Bedford

Knightsbridge and Belgravia

II. THE INDUSTRIAL CITY

NINETEENTH-CENTURY EXPANSION: 1800–1890

III. THE POSTINDUSTRIAL CITY

THE RECOVERY OF THE CITY: 1975–2000

Postwar Urban Design in America

Battery Park City

Postwar American Context

The Cornell School

The European School

Leon Krier

Rob Krier

Peterson Littenberg Koetter/Kim Campus Design

Craig Neely

Leon Krier

Duany Plater-Zyberk New Urbanism

Moule & Polyzoides

Dan Solomon and John Ellis Krier Kohl West 8

PosadMaxwan

OMA

Foster + Partners Calthorpe Associates

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY URBANISM

The Contemporary Ecological Environment

PROTO-MODERN URBANISTS: 1890–1922

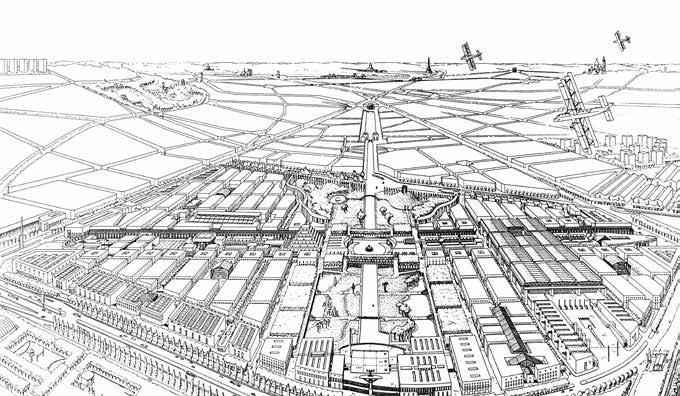

Proto-Modern Planning

Joseph Stübben

Camillo Sitte H. P. Berlage

Otto Wagner and Daniel Burnham

Eugène Hénard

The Garden City

Tony Garnier

THE MODERNIST CITY: 1922–1975

Painting and Modern Architecture

Le Corbusier the Architect

Le Corbusier the Town Planner

The Ville Contemporaine

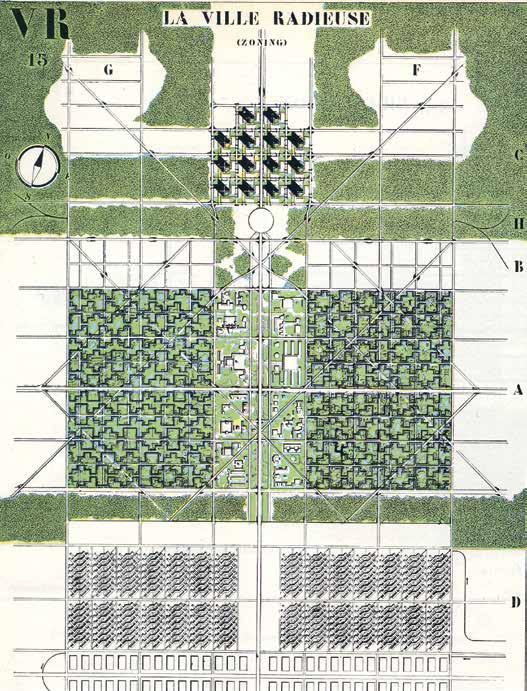

The Ville Radieuse CIAM and Town Planning World War Two

ORO

Richelieu 1628

Postwar Reconstruction St. Die

Chandigarh

Marseilles

Team

The Contemorary Built Environment Urban Form and Ecology Freiberg im Breisgau Vauban Malmö Bo 01 Västra Hamnen

Stockholm Hammarby Sjöstad Eco-Cities and Urban Form

Conclusion

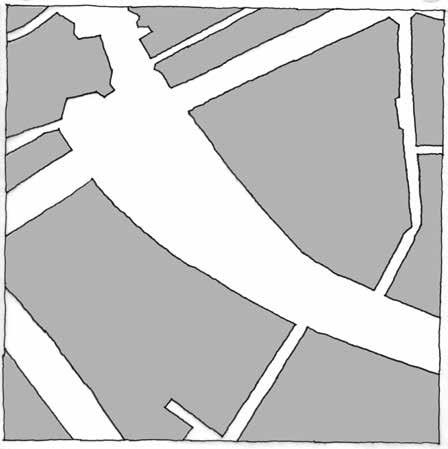

EXCURSUS: IRREGULAR & COMPOSITE PLANS

Irregular Plans

Rome Venice Palermo

Jaipur

Bussy St. Georges

ORO Editions

Foreword

Steven K. Peterson

The importance of this book by Michael Dennis, following his Court and Garden, published in 1986, is its assertion of the imperative presence of the urban plan. This book contains such a dense compilation of city plans and aerial views, that it can almost be “read” without the words as a visual narrative of the formal urban layouts covering 3,000 years of Western building. The book makes apparent that plans endure as a language in themselves, commenting on each other as protagonists of thought and engines of criticism. The city plan is the essential notational grammar of urban form.

ORO Editions

To begin this discussion of cities, let me tell you a story about New York.

Our five-year-old granddaughter, Esmee Elisa Sherrill, lives in the small town of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. It is, just as it sounds, a charming, tiny place with handsome brick Craftsman-style houses on treelined streets. Esmee comes with her parents to visit us in Manhattan about twice a year. This time, and at her age, she had become especially fascinated by all things in the city, and was excited to see and ask questions. She wanted my wife Barbara to take her out for a walk to look at our Manhattan neighborhood—the buildings, the streets, and Central Park. The view of Park and 65th Street is what it looks like in our neighborhood.

She heard the trains under the street. She saw the steam rising from the red and white cones over manholes. She asked about everything, and Barbara, holding her hand as they walked, explained: about the trains under the grass center strip of Park Avenue that could take you to Buffalo and Chicago; about the dragons below the street that heat the buildings and spew their steam; about the baby alligator pets brought back from Florida that are flushed down toilets to grow up in the sewers. Esmee smiles. She has a kind of W. C. Fields skepticism that comes from an experienced life of cartoon television.

Back at the house after their walk, Barbara told me Esmee’s last question: “Why do people in the city live in apartments instead of houses?”

Barbara and I looked at each other, jaws dropped, eyebrows arched. Of course, this was not a question at all, but a child’s accurate, innocent (and because of its directness), very potent observation: “People in cities live in apartments instead of houses.” That is the whole deal. It is radical. This is an aspect that is common to all urban places as different as New York, Paris, or Rome. There are no separate houses, and very few object buildings. All the buildings touch. They go together wall to wall. This discussion about “urban” is not just about the definition of words. It is a recognizable physical condition sensed intuitively, even by a five year old, but it flies under the radar of professionals with vast amounts of analysis and discussion.

ORO Editions

New York street view at Park and 65th Street

Not all cities are urban. To statisticians the word “urban” literally means “not rural,” and their word “city” just means a gathering of 100,000 people or more. Not very helpful at all as to shape and form.

This is obvious enough since most of what is being rapidly built and called cities today are actually not urban at all, and this is a real problem.

As of 2010, more than 50 percent of all people in the world lived in an urban area. Of all these urban dwellers 60 percent live in cities defined as 100,000 people or more. By 2050, 70 percent of all people will be living in urban areas.

What does this mean for us? What form will these places have?

w h At i s U rb A n ?

What is urban? How can we make it? It is not a matter of density, or size, or a particular architectural style. Large cities, medium towns, and even small villages can be urban.

We already know that, both Los Angeles, California, and Savannah, Georgia, are not really urban. Everybody in those places lives in houses. To Esmee, they would look like big versions of Hollidaysburg. “Urban” means no houses. Both the historical center of New Orleans and the city of Manhattan are urban. Rome is urban, while large parts of London are not.

Urban is a special condition of cities and towns in-

dependent of their size or density, and results when buildings touch and are not free standing. Attached buildings combine into common urban walls, which are necessary to both define exterior space and subdivide it. This continuous wall is the essential urban element; it makes precise edges to streets, defines squares and parks like exterior rooms, and closes blocks, dividing outside from inside, front from back, public from private. A one-street English village can be urban, while a big city of millions like Detroit might not be. I realized the importance of this a few years back when Mike Dennis called me to talk. It was part of our ongoing conversation about cities and urban design that began at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, in 1969.

Mike is always calling to test his observations, and being a Texan, he charms you by disguising assertions as questions: “Steven, I want to ask you a question about something. Do you think there are any real cities in America?” What? Well, I knew the answer. No, there are very few real “cities” in America. We both knew this was true. But it was a shock to say it out loud. I was raised in Chicago, which is a vast sprawl of free-standing houses and small walk-up apartments. Except for New York and some downtown cores, most US cities are really just vast grids of mostly wooden houses. Of course, this, like all useful characterizations, is also somewhat of an exaggeration.

t he U rb A n b lock

The first urban condition is the closed block. Only without houses (also, without free-standing buildings) does a city or town become truly urban. This is because, instead of houses, everything gets pushed together and becomes a closed block, a compound form, another entity. The closed block with its compressed, multiple architectures is a somewhat illusive and singular aggregate form. The enclosed block is the miraculous key from which every urbanity flows.1

The block provides:

Density, and sharing of services and costs. Every apartment building is a community secured by a doorman, with garbage removal, mail delivery, and all commonly managed. It is urbane and civilized.

The block provides:

Diversity. Many different people with different incomes can live in the same place—in apartment buildings—without knowing each other.

The block provides:

Privacy. In Hollidaysburg, Esmee’s side window looks into the neighbors’s dining room. In the city, you can’t even see the building next door because you are attached to it.

The block provides:

Mixed use. In Hollidaysburg you can’t buy a lightbulb or get groceries down the street in shops under your neighbor’s house.

The block provides:

Conjunctions of potentially conflicting uses. In the view along Park Avenue, the three-story private club at the far end doesn’t disturb the next two four-story residential town houses, and they are unperturbed by the twelve-floor hotel at the corner, with its busy French restaurant’s entrance around the corner.

Notice, too, the detailed architectural relationship of cornices, openings, and materials among the very different styles and sizes of the buildings. It is conversation in architectural language.

ORO Editions

Aerial view of Chicago

U rb A n s pA ce

The second urban condition and the primary medium of city design is space.2

The next time Esmee came to New York, I took her to the Museum of Natural History. We went to the planetarium first for the new show about outer space. The lights dimmed, the stars appeared, and the vast empty universe surrounded us. Esmee cried in terror. We left in a total state. She was not amused. Back at the apartment, her mother Lee tried to understand: “But Esmee, you like the stars in the night sky. What was wrong?” Puzzled, she thought, and responded: “I don’t know Mom, I think I am just space shy.”3

“Space shy,” the terror of vast emptiness. This is part of why we make cities, to corral space and make it our own size, to divide it into discernible packages. We invent enclosure to protect us, boundaries to define our place, and to guide the order of our movement. Cities are the created world that substitutes for emptiness and the undefined. We make the design of bounded urban places because we are all fundamentally “space shy.” We need the discipline of contained public space, the security of defined streets, and enclosed squares and parks. Only the walls of urban form mediate between the calm of private apartments in the midst of public chaos. This is not historical, modern, or traditional; it is universal to any urban city: space formed by the walls of attached buildings enclosing blocks for private use.

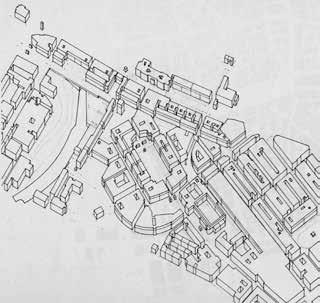

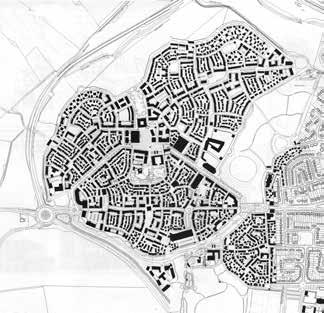

Rob Krier and his partner Christian Kohl have built new towns, such as Kirchsteigfeld, outside of Potsdam, using these urban conditions.4 It is the essence of urban form in woven patterns, and varieties of places; an amazingly inventive and richly varied plan of particular spaces and blocks. Although the buildings, unlike New York’s, are three and four stories, Kirchsteigfeld nonetheless epitomizes what is urban. Its block scale is flexible and adaptable.

There is a real joy in just squinting at the white spaces and the variety of urban elements: grids, boulevards, squares, lozenge-shaped piazzas, round points, rotated urban fabric of blocks and streets. Why couldn’t this be built outside Washington, DC, or in downtown Newark, New Jersey?

ORO Editions

Plan of Kirchsteigfeld, Potsdam, Krier Kohl Architects

The closed figural spaces shown here have to be consciously made and carved from the plasticity of solid blocks. You can’t have one without the other. Incidentally, depending on the height and depth of buildings, this plan could probably be one for an urban city of 100,000 people.

The new cities we build tomorrow can be just as urban as our existing historical ones because the urban structure of cities is independent of the architecture it contains. The city does not have to be reinvented with each era or change of style, because it is already the container for change and the structure for a conjunction of differences. If so, why isn’t real urbanism happening in the vacuous new cities being rapidly built around the world?

A nti U rb A n h yper -A rchitect U re

It is easy to blame the famous designers of hyperarchitecture for the lack of urbanism because they reject city contexts and just emphasize superficial shapes. But they are caught in their own spiraling bind as architectural entertainers. To be continually noticed in the competitive context of explosive world growth, more extreme notorious gestures will be required each time successively.

The world of hyper-architecture does not cause a rejection of urban form. It is just the inevitable fallout from a culture driven by the desire for fast cities (like fast food) that are banal, expedient, and technically proficient. They fill up quickly, but cannot satisfy or sustain a public life of genuine urbanity. They derive from the politics of power and image, from economic speculation, and from an excessive imbalance of wealth.

t he U rb A n p l A n

The failure of contemporary “fast cities” to be designed as urban places that are culturally sustainable over time is due to a societal void, the lack of political will, and the complacency of technocratic consultants. It is not caused by the arrogance and indifference of individual architects.

A city is the broader plan, an independent urban formal structure that has values and assets that even the most entertaining acts of architecture can never provide alone.

Look at New York City. Since the 1970s, the number and types of buildings have radically expanded and changed, but the urban structure, the basic armature of spaces, blocks, and streets, are still the same. It did not need reinvention or rethinking to accommodate the changes in architecture and scale because, in a very real sense, the urban form of New York City did not change at all.

c oncl U sion

This book illustrates the vast story of settlement plans, blocks, and spaces. It is a potent reference source of urban knowledge that might easily be subtitled “Templates for Towns.” So, as you look through this marvelous and useful collection of town and city plans, be careful and participate. Watch out for city designs that are just large patterns made of individual houses and free-standing buildings. Instead, be aware of subtle differences: look for blocks; pry out public space; and keep asking: is it urban?

ORO Editions

2. The French Building, 1927, Sloan and Robertson

1. Street view, Kirchsteigfeld

ORO Editions

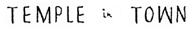

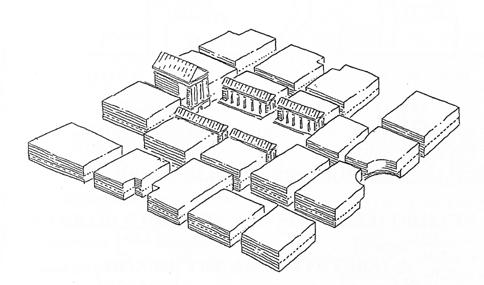

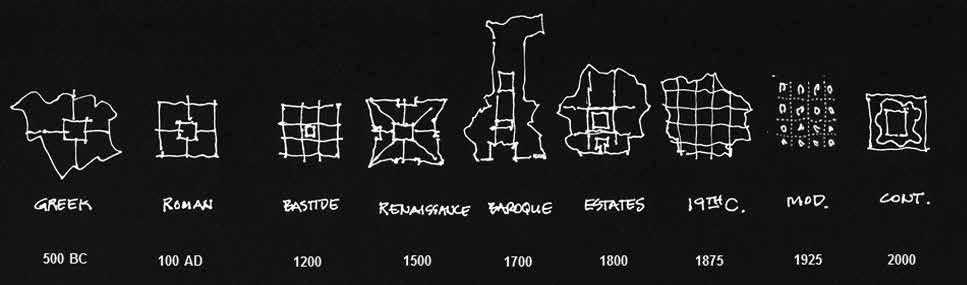

Diagram of town planning types

Preface

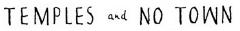

This book may be seen as a companion to my first book, Court & Garden: From the French Hôtel to the City of Modern Architecture (1986). Both books chronicle the disintegration of the city and long for its reconstruction, but Court & Garden traces the formal and social transformation of an architectural type from embedded urban buildings to free-standing private icons, while Temples & Towns focuses on the larger issue of town planning—a discipline that too many conceive as large-scale architecture.

This book has three aims: to trace the historic evolution of urban form, principles, and design; to serve as a compendium, or reference, of city design; and to polemicize the necessity for the recovery of the city and a contemporary urban architecture. As such, it may be read graphically, textually, or both. I like to think that it falls into the long tradition of illustrated treatises in which theory is embedded in the projects, with only occasional assistance or clarification from the text. Architecture and urban design are physical arts, not verbal arts, and they are best understood from graphic representations.

Illustrations graphically represent the urban language and the architectural language just as words represent spoken languages. At one time architecture and urbanism were analogous to slightly different dialects of Latin, but today they have come to be separate, but related languages, like Spanish and Italian. Despite their common base, however, today many people who understand one do not understand the other. Nevertheless, both can be understood without being verbally described. Mathematicians do not need verbal descriptions of their equations; they understand them directly. Architects should be able to read the drawings and pictures without reading someone else’s description of them.

From eighteenth-century French treatises on domestic architecture to Rob Krier’s 1982 monograph, architects have understood their profession through graphic representation, bolstered by a few facts. For those who understand architecture and urban design without assistance, this study can be “read” without literally reading the text. The text does add something, however. For example, it is good to know that, contrary to common assumptions, Cerdà did not win a competition for the Barcelona expansion plan. (He did not even enter the competition.) It is also useful to understand the difference and development sequence of the Roman cross-axial plan versus the Roman castrum plan. But these are clarifications that augment understanding, rather than being necessary.

Finally, a word about terminology: town and city are used interchangeably, but town planning is preferred over city planning because, though old-fashioned, it implies design more than the contemporary use of planning. The terms city and urban are more problematic. At one time urban was synonymous with city. Cities were urban. In our time, however, not all cities are urban. In fact, many are not—especially new ones. More like warehouses for people, cities in rapidly developing parts of the world are built quickly and expediently to house urban immigrants, but with little regard for the quality of urban life. To be genuinely urban two things are required: sufficient continuity of buildings to define the public space of the city—the civic structure—and mixed-use neighborhoods that provide a variety of social and functional amenities. In his Foreword, Steven Peterson discusses the formal requisites for urbanity, and why small towns like San Jose del Cabo in Mexico are urban, but most American cities are not.

ORO Editions

1. Aerial view of Chicago

2. San Jose del Cabo, street view

ORO Editions

Introduction

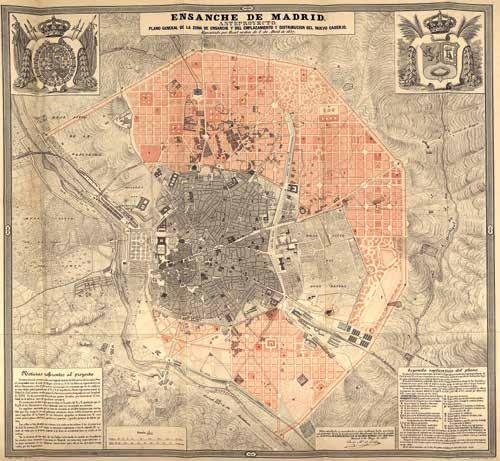

This study grew out of curiosity about two contrasting but interrelated issues: the pervasive estrangement of contemporary architecture and the city; and—in complete contrast—the apparently sudden sophistication of late-nineteenth-century city expansion plans, such as those by Poggi for Florence, and Cerdà for Barcelona.

For about 2,500 years town planners designed and drew cities, or parts of cities, and architects designed and drew buildings that occupied them; but in the late nineteenth century, and early in the twentieth century, town planners began to draw buildings rather than cities—which has created enormous confusion about the relationship between architecture and the city.

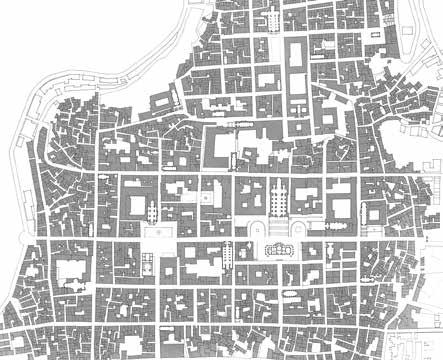

We therefore set out to trace the long evolution of urban design, or town planning, through planned cities and towns—not urban interventions such as Vienna’s Ringstrasse, and not organic, or cumulative, cities such as Athens and Rome.

We begin with the planned cities of Greece and the Roman Empire from about 500 BC, through the late-medieval Bastides, the ideal Renaissance cities, and Baroque new towns, to the urban planning strategies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Town planning will again be crucial in a world of diminishing resources.

ORO Editions

View of Rome from the dome of St. Peter's

o n c ity F orm , t heory , A nd h istory

Confrontation with the complexity of the city is daunting—unlike science and mathematics where, according to Richard Feynman, problems are nearer the surface and significant work can be achieved at a relatively young age. With architecture and the city, problems and solutions are more elusive. Architecture and the city are slow maturation fields where history and culture are essential. The issues are less clear, and significant work tends to come later in life.

It is difficult to find clarity or consensus, for example, regarding the questions: What is a city? What is urban? What is urbanism? What is urban design? What is planning? There is little consensus today regarding answers to these questions, partially because the terms themselves have become confused, co-opted, and disconnected from meaning. Experience and conviction are required.

The terms design, theory, and history further confound the discussion, even if we speak of urban design, urban design theory, and urban design history The articulation of these three terms is a distinctly modern (post-Kantian) phenomenon. The ancient Greeks, for example, steeped as they were in the concreteness of Homeric precedent, would not have understood such a distinction.1 In our own time, Leon Krier has observed that you only need a theory if you don’t know how to do something. But today there is little consensus about architecture and urbanism, and theory is a necessity.

At its purest, design is the manipulation of form and space. It is also about something, however, and throughout most of history, design was accomplished within a set of conventions. These conventions formed the theory base that guided design decisions. (Not everything had to be reinvented every Monday morning.) Indeed, it could be argued that theory grew out of design practice, and that design practice grew out of societal circumstance. Because design was embedded in the circumstance of culture and politics, it was part of the continuity of history. Within this framework better designers made better designs: e.g., Michelangelo versus Bandini. On occasion, great inventions transcended the conventional, or revolutionary ruptures precipitated an abrupt change in either

form or society, but the norm was a condition of evolution or continuity.

Much has been written about the fact that this all changed in the twentieth century; theory now often precedes—and sometimes replaces—practice; major architectural designers are often trivial or disastrous urbanists; and the design professions have a generally uncertain relationship with the society of which they are a part.

According to William Westfall, a city has three constituent elements:2

the political character of its citizens; their institutional arrangements; and the embodiment of their politics and institutions in architectural and urban form.

As architects and citizens we should be mindful of the first two of these. As architects and urban designers, however, our focus should be on urban form as the physical embodiment of the idea of the city. The city may also represent the political aspirations of its citizens, but most cities have reflected different political aspirations throughout their history.

The most fundamental characteristics of urbanity are spatial definition, density, and mixed uses. Other physical characteristics are also important: continuity, scale, pedestrian orientation, varied neighborhoods, uniqueness of place, possibilities of both community and anonymity, incremental growth, and possibility of movement—ideally through public transit.

Worldwide, cities exhibit more similarities than differences. Many physical attributes, such as typology, are persistent and cross-cultural. Indeed, it can be argued that the biggest changes in the long evolution of traditional urban form have been prompted by changes in technology—especially the technology of movement: e.g., the invention of the sprung carriage in the eighteenth century; the advent of the railroad and the elevator in the nineteenth century; and the advent of the motor car, and perhaps the airplane, in the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century the traditional city “loosened” to accommodate this new condition of movement, and expanded to accommodate the urban population explosion precipitated

by the industrial revolution. But until the twentieth century all these changes utilized traditional urban typologies. Cerdà’s Barcelona is a particularly beautiful example.

Cities are composed of buildings, blocks, streets, squares, parks, neighborhoods, and a legible civic structure, and this—the form of the city—was the beginning point of this study. In other words, the concreteness of town plans was used to reveal the principles, or urban design theory, behind them, and this in turn led to authors, philosophy, culture, and history. The intent was to bring the professional artifacts themselves to the foreground for comparative purposes. This revealed a surprisingly consistent (and surprisingly continuous) tradition of urban design, or town planning theory—at least until the twentieth century. What follows are the components of the study that have been outlined above.

o n U rb A n d esign

Urban design is the design of the physical framework of cities within which architects design buildings. More precisely, it is the design of the public realm of the city, including specific landscape and public space design. Architectural design is the design of the private realms of the city, but also its civic buildings. Urban and architectural design occasionally overlap, and the “fit,” or relationship, between the two is a contentious issue today.

Cities have always been composed of monuments and fabric, but until the middle of the eighteenth century the city’s monuments, or civic buildings, were embedded within the city fabric. There was hegemony of the public realm. But in the eighteenth century formal sensibilities changed as societal institutions expanded, and public buildings became articulated from the urban fabric. Gradually this formal propensity toward free-standing objects extended to private buildings as well, and the private realm achieved hegemony over the public realm in the early twentieth century.3

ORO Editions

The dilemma of urban design today: even the most inconsequential private buildings are often considered “art,” and few buildings contribute to the urban fabric and space—the matrix of the city.

U rb A n F A bric

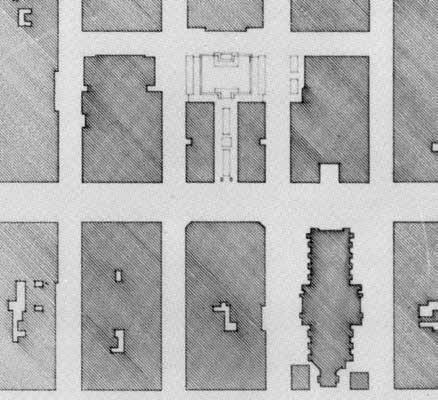

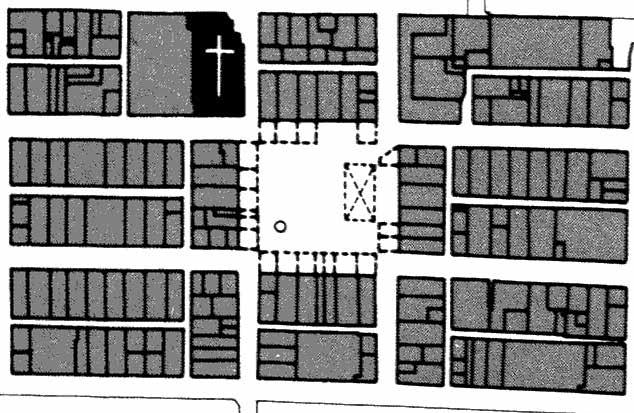

Spiro Kostof points out that in the morphogenetic approach to urban geography by M. R. G. Conzen, “urban fabric” comprises three interlocking elements: (1) the town plan of streets, blocks, and spaces; (2) the land use pattern of parcels; and, (3) the three-dimensional building fabric.4

Generally speaking, this is also a rough description of the differences between what town planners, or urban designers, have traditionally done (1 & 2), and what architects have done (3). Town planners had to be conversant with the building typologies for which they were planning, but they usually were not in-

volved with the specific design of buildings that filled the urban fabric.

ORO Editions

The size, scale, and block structure of the private parcels is a primary determinant in the character of the city, and the argument has been made that as the size of the parcels goes up, the quality of the environment goes down.

1. Town plan: Streets, Blocks, and Spaces

2. Land use pattern: Parcels

3. Building fabric: Architectural design

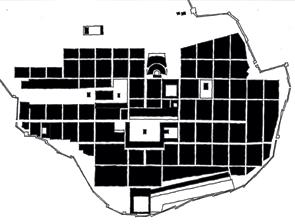

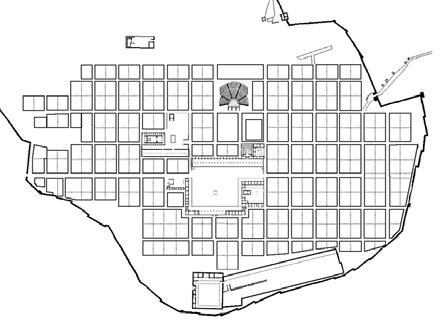

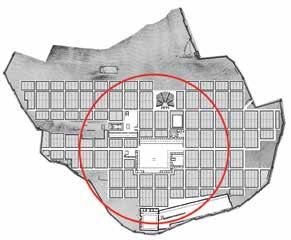

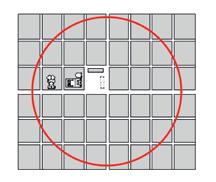

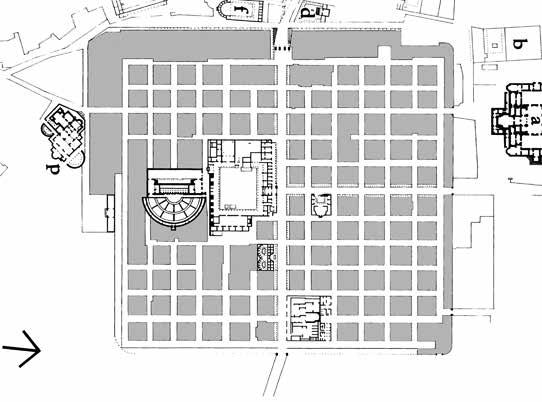

4. Town plan of Priene, ca. 350 BC

5. Land use pattern of Priene

6. Building fabric of Priene

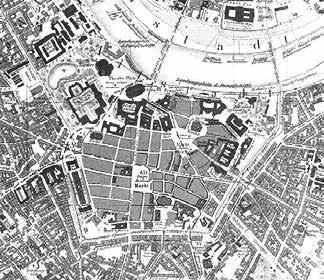

p l A nned A nd U npl A nned c ities

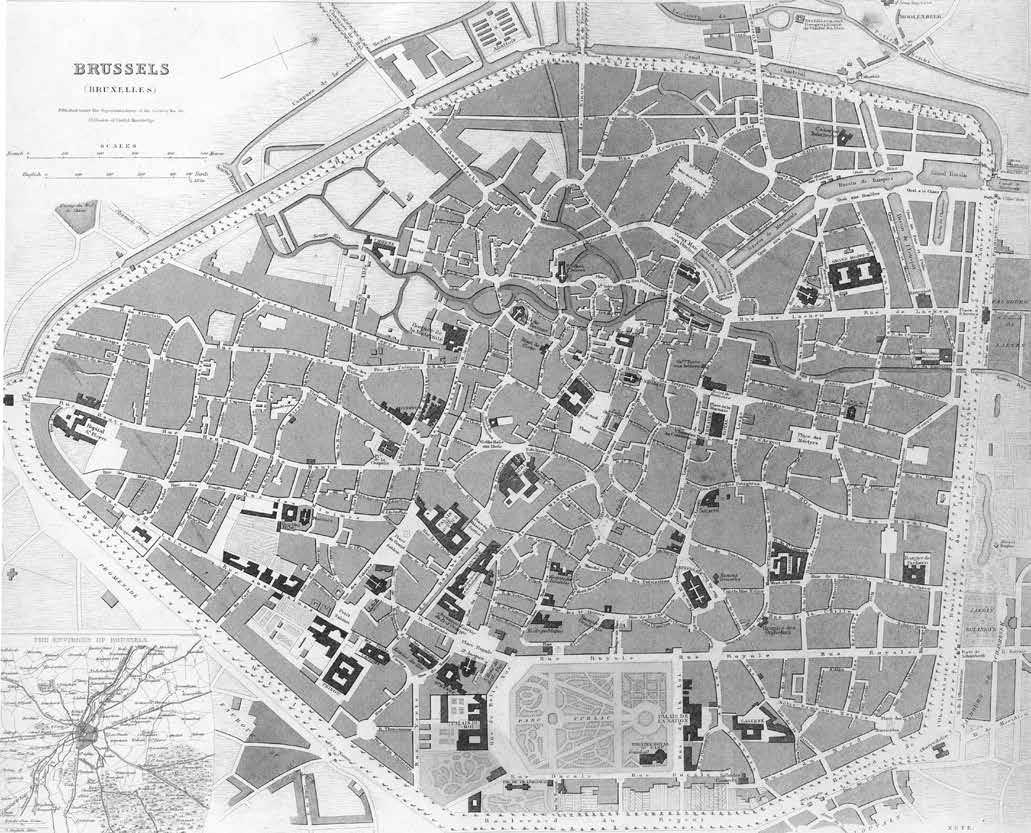

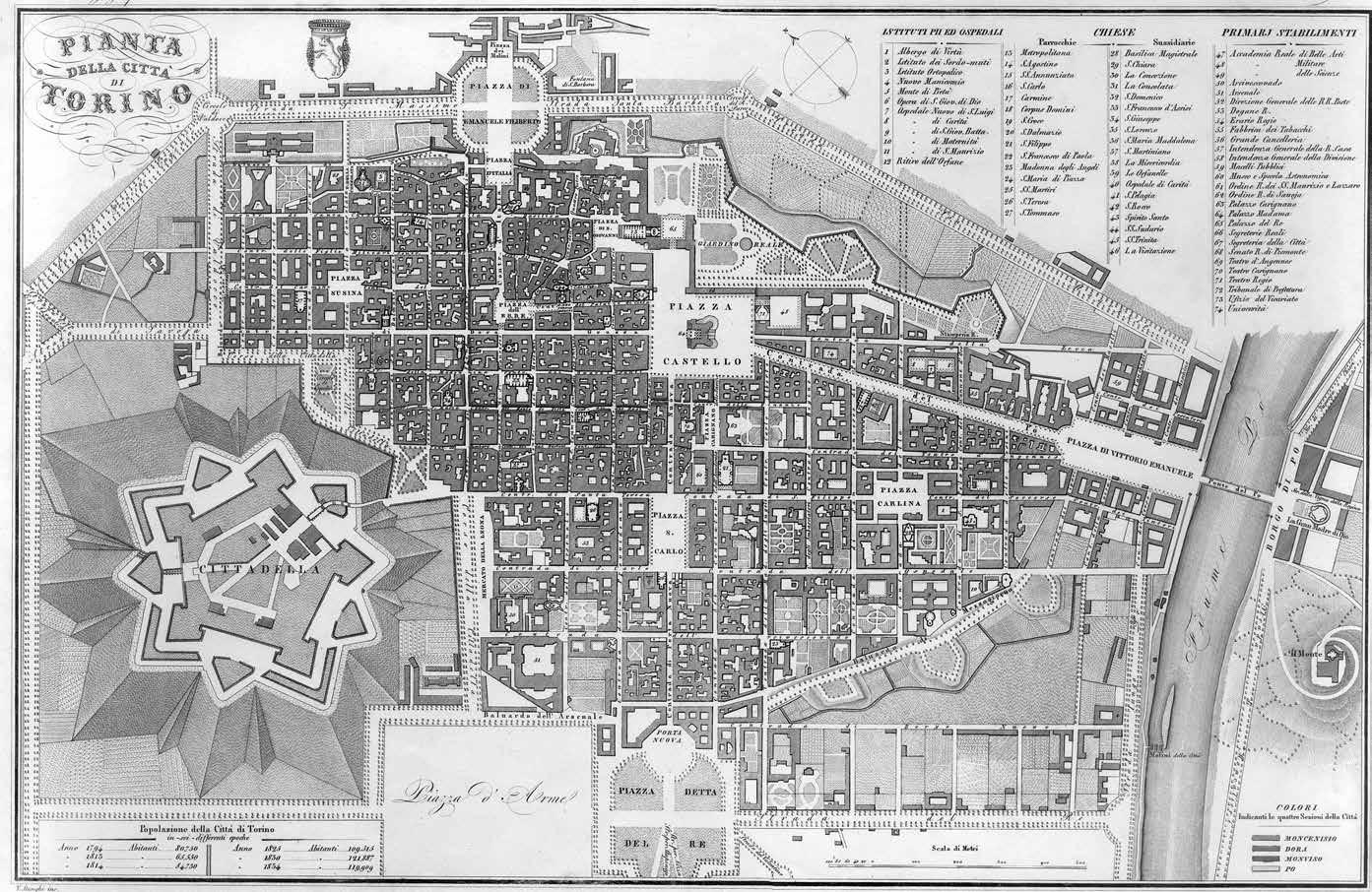

Both regular, planned cities, and irregular, unplanned cities grow incrementally—usually over a long period of time—to become cumulative cities. We often associate cumulative cities with organic or picturesque patterns, such as Rome, or irregular medieval cities, such as Brussels. But in fact, Manhattan is a cumulative city despite its grid and relatively short life, as is Turin, with its much longer life.

t ypes o F U rb A n d esign

There are three types of urban designs: planned cities and expansions; urban interventions; and architectural interventions.

p l A nned c ities A nd e xpA nsions

Planned cities and their major expansions are the subject of this study. Urban and architectural interventions happen within a plan, and may support or contradict it. They are also, by definition, a blend of architecture and urban design. But the design of an urban plan must stand alone. It is also not largescale architectural design. Pure—perhaps ideal—values are visible and essential in designed plans, as the nuance and variation of years of incremental development cannot be envisioned and designed. This is why there have never been designed irregular town plans, nor unplanned grid towns. This is also why the new world was colonized almost entirely with planned grid towns. The very tip of Manhattan is a bit irregular, but the only city in America with an irregular plan is Boston. Because of their interest, however, a section on irregular plans is included at the end of this study.

ORO Editions

Plan of Brussels, 1837

ORO Editions

Plan of Turin, 1844

U rb A n i nterventions

For present purposes, urban interventions are sizable urban design projects that alter existing urban fabric. An intervention may be destructive—as by fire, war, or “urban renewal”—or constructive—in order to connect, alter, or revise parts of the city.

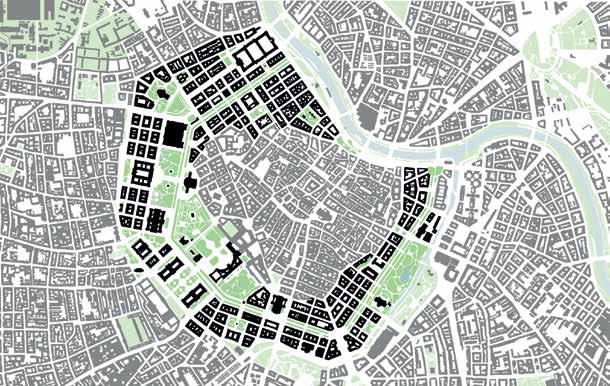

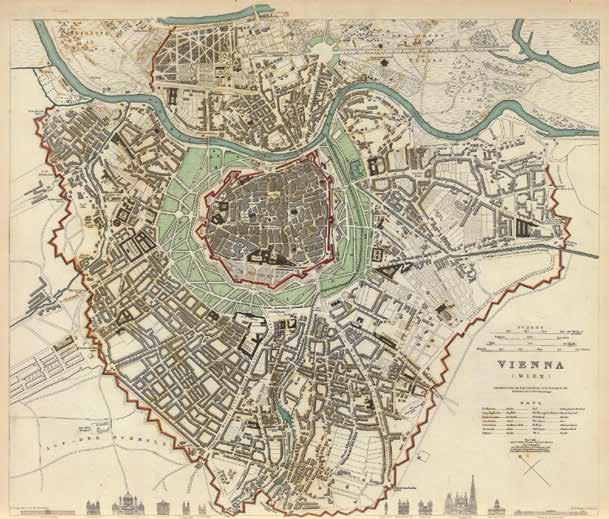

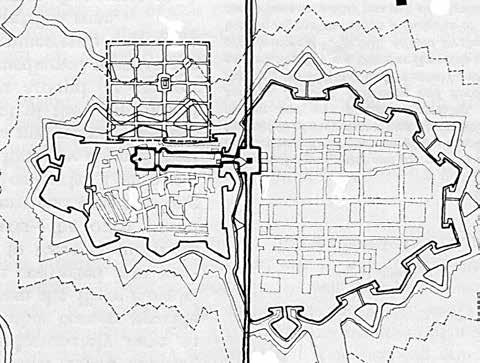

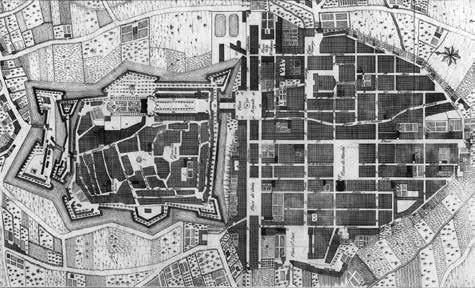

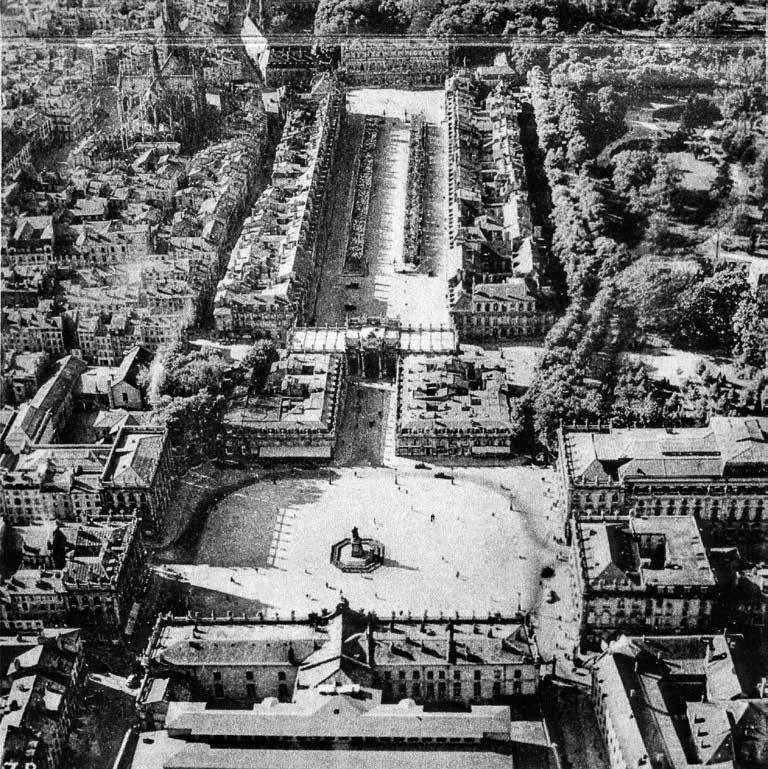

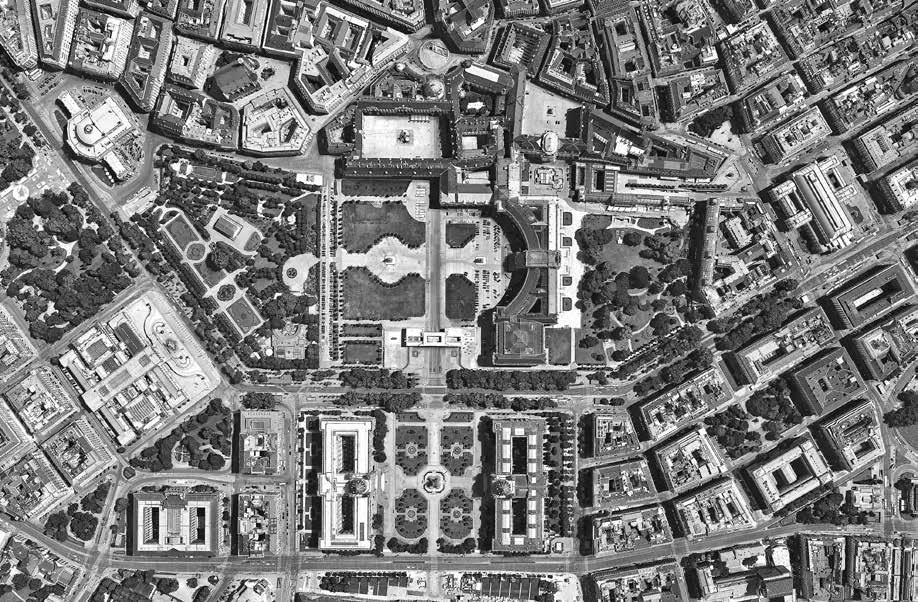

The Ringstrasse in Vienna, for example, filled a previously open space, to bind the existing inner and outer parts of the city together. In fact, many European cities found urban design opportunities after the fortification walls were torn down during the Napoleonic era. Another superb example is the Baroque sequence of spaces designed by Héré in Nancy, to bind two distinct parts of the town together.

Other notable urban interventions include: the Roman designs for Sixtus V; Paris streets by Percier and Fontaine; London projects by John Nash and George Dance; and Vasari’s Corridor in Florence.

ORO Editions

1. Plan of Vienna, showing the Ringstrasse, begun 1857

2. Plan of Vienna before the Ringstrasse, 1840

ORO Editions

4. Aerial view of Héré’s spatial sequence

1. Nancy, the fortified medieval and Renaissance towns, 1645

2. Plan of Nancy, showing Héré’s intervention, begun 1753

3. Plan of Nancy, with Héré’s intervention, begun 1753

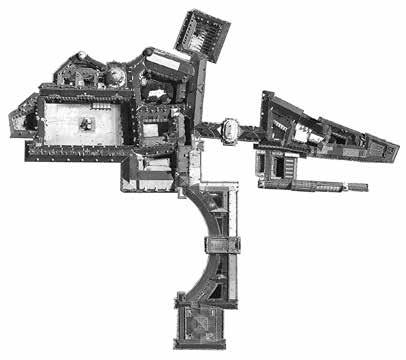

c omposite A rchitect U r A l i nterventions

Cities often have mega-buildings that are accumulations of interconnected buildings. The best ones, like the Hofburg in Vienna, respond, reflect, and enhance the urban context. Others, like the Massachusetts State House in Boston, are more modest in scale. Still others, such as Rockefeller Center, are primarily public spaces and extensions of the urban fabric. Other notable composite buildings include: the Vatican; the Quirinale; and the Palais Royale.

1. Rockefeller Center, plan

2. Rockefeller Center, aerial view

3. Hofburg, aerial plan

4. Vienna, Ringstrasse, aerial plan, detail, begun 1857

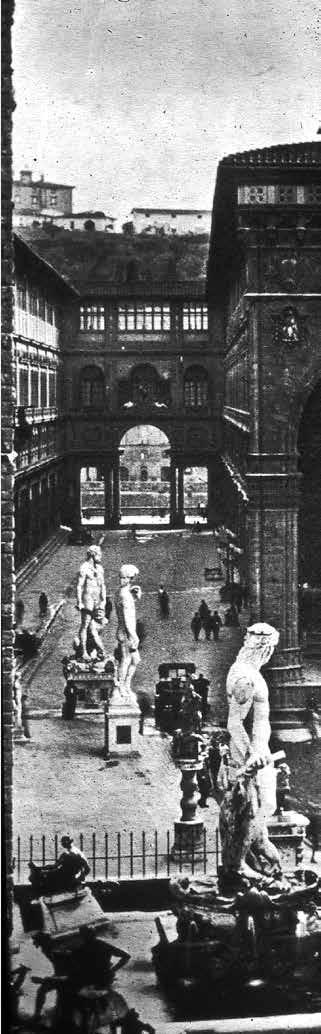

A rchitect U r A l i nterventions

Buildings that define public space and function as urban fabric—such as the Uffizi—buildings that function as monuments, and ambiguous buildings can all serve as positive urban interventions.5

Other notable architectural interventions include: the Zwinger in Dresden, and the Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome.

ORO Editions

1. The Uffizi, view

2. The Uffizi, aerial plan

3. The Uffizi, plan

4. The Zwinger, aerial view

5. Prewar Dresden, plan

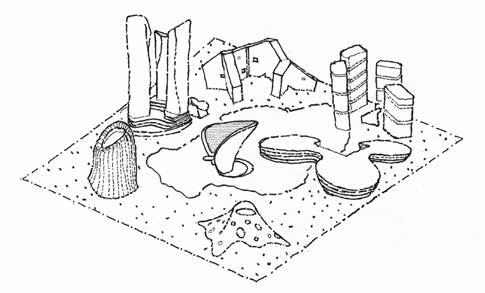

g reek t emples A nd t owns

Traditional treatises on ancient Greece tend to emphasize temples rather than towns. Thus, our mental image is typically that of an Acropolis of picturesquely arranged temples separated vertically from the town—as at Sunium, Aegina, or the Acropolis in Athens. These complexes were usually unrelated directly to the town itself, but were always related to the larger landscape.6 The sacred precincts at Delphi and Pergamon are extreme examples of a collection of temples.

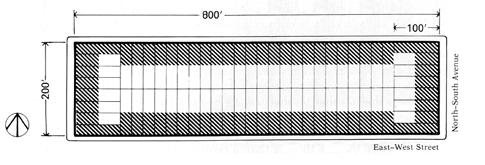

With the advent of planned Hellenistic colonial cities, however, the temples were usually brought “down” and integrated into the fabric of the town.7 They were more articulate and emphatic than the civic buildings, such as the stoa, gymnasium, bouleterion, and ekklesiasterion, but they were organized into the grid of the town, thus fundamentally changing their relationship to both the town and the landscape. The civic buildings were integrated into the fabric of the town as at Priene and Miletus, and the housing blocks were generally small and uniform. The original parcels were usually rectangles of about 2,500 square feet—oddly enough, the same area as the typical 25' x 100' New York City block.8

Thus, a dialogue was established: between the sacred and profane; between temple and town; or, formally, between monument and urban fabric.

r om A n t owns

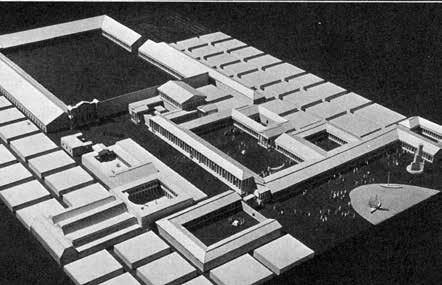

Beyond Rome, the Roman colonies and castra followed Greek and Etruscan precedent—as grid towns that included the temple within the fabric of the town. The forum was located at the center of the town, like the agora at Priene, but unlike Greek towns, the original Roman towns had clear geometric perimeters. Roman blocks were often more squarish in proportion than Greek blocks, but the parceling system is unclear due to medieval rebuilding.

It can be argued that the Greeks were not interested in space, but the opposite may be argued for the Romans.9 This can be seen most clearly at Miletus. Begun in about 466 BC, the planned Greek town was extended and completed by the Romans. The southern portion of fabric is Roman, but it is in the central civic sequence of spaces that the Roman system of spatial enclosure is most evident.

Timgad was founded in north Africa for retired Roman soldiers in 100 AD, and was one of the last Roman towns. As the Roman Empire disintegrated, towns and town planning in the West ceased for several hundred years.

ORO Editions

1. Athens Acropolis

2. Plan of Priene with five min. walk shed

5. Model of the core of Miletus, second c.

3. Plan of Roman Florence with five min. walk shed

4. Plan of Roman Timgad, 100 AD

b A stide t owns

As trade grew, and western Europe began to emerge from the so-called dark age, medieval towns also began to grow—mostly incrementally, and sometimes over the remains of Roman towns.

But after a lapse of about eleven centuries, a series of regular grid towns began to be founded, primarily in southwestern France. Between 1200 and 1400, nearly 700 Bastides were built in this area.10

Following the Roman pattern, the town’s market square was located in the center of the grid plan, usually with a colonnade around the square. The square was complete and open, the town church being located outside the square. The residential blocks were modest in size, with long narrow parcels, and alleys down the middle.

i de A l r en A iss A nce t owns

Although the first planimetric maps of cities did not appear until the middle of the sixteenth century, the reconnection with antiquity through the discovery of Vitruvius’s Ten Books in 1414 sponsored a seemingly endless series of ideal town plans beginning in the middle of the fifteenth century.11

These proposed city plans were centralized and fortified. They were of two types: radial and orthogonal. And though many plans were proposed from the middle of the fifteenth century, built examples—such as Sabbioneta and Palmanova—did not occur until almost 1600. The practice continued, however, until after the earthquake in Sicily in 1693, with the construction of Grammichele and Avola.

The “New World” was also touched by colonization and the grid tradition. The “Law of the Indies” evolved between 1512 and 1680, and was the basis for most towns in Latin America, including the southwestern United States.12

b A roq U e n ew t

owns

Destruction by earthquakes also precipitated Baroque plans such as those for the reconstruction of Noto after the 1693 earthquake, and Lisbon after the earthquake of 1756.13

These plans might be seen as fragments of ideal Renaissance plans, except for their organization around a civic structure comprised of a theatrical, Baroque sequence of spaces and buildings. Major buildings are not articulated as “temples,” but form an integral part of the spatial sequence. Blocks are modest in size with varied parcels.

1. Plan detail of Monpazier

5. Aerial view of Palmanova

2. Plan of an ideal city by Pietro Cataneo

6. Plan detail of Noto

3. Plan of Lisbon, 1756

4. Aerial view of Monpazier

t he e A rly n ineteenth c ent U ry

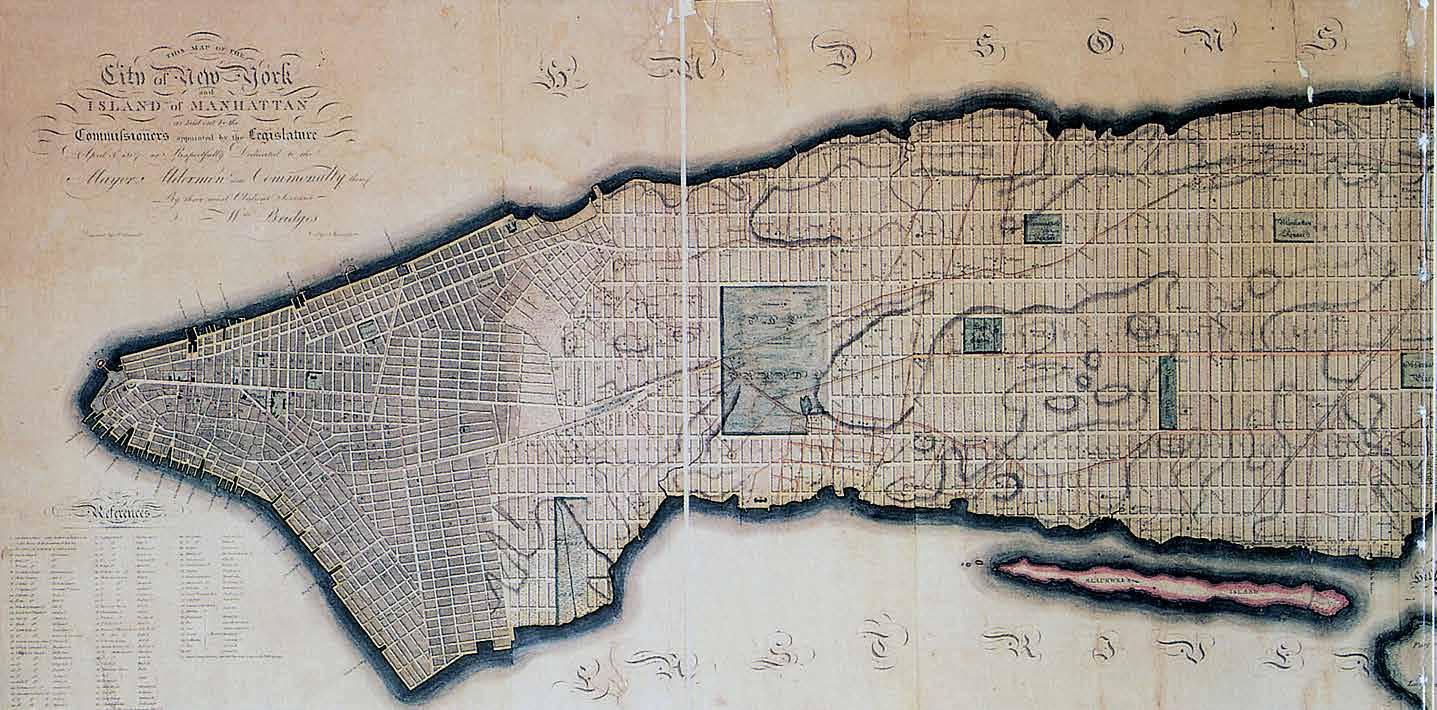

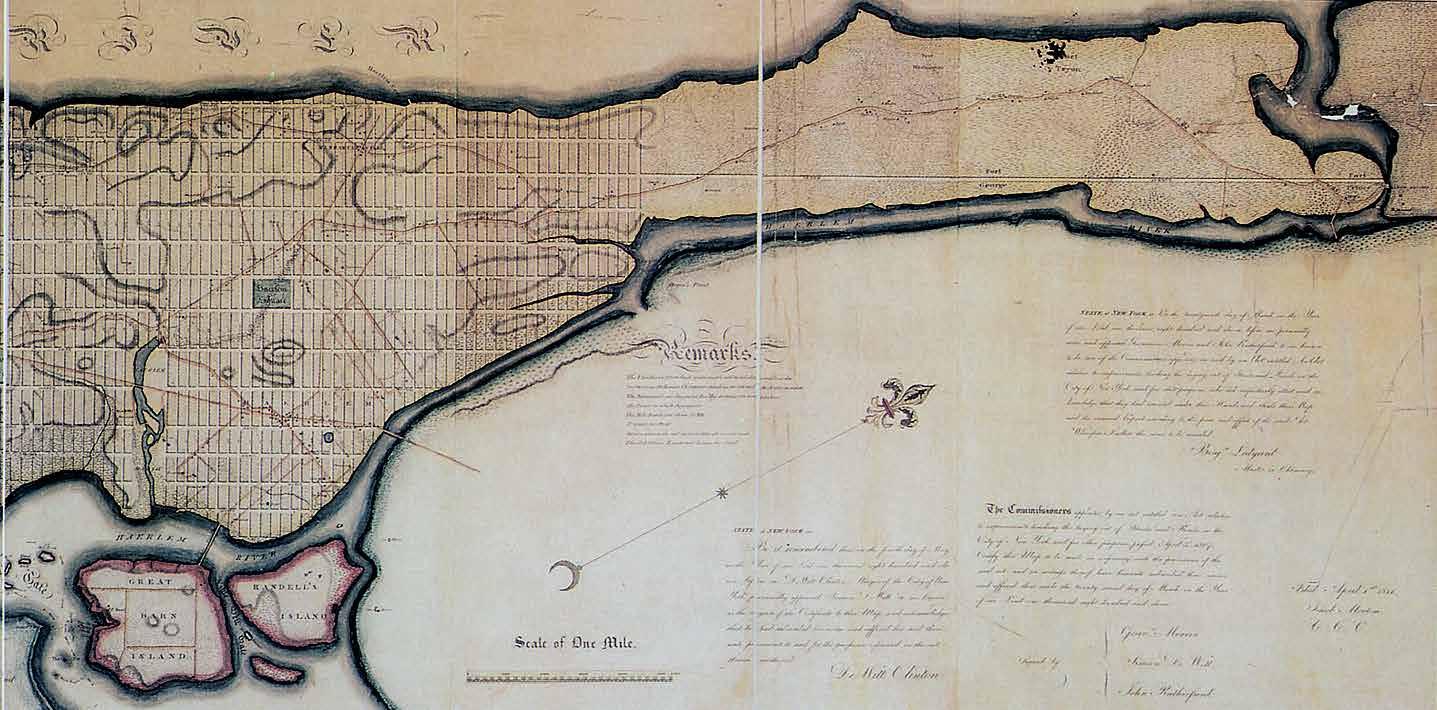

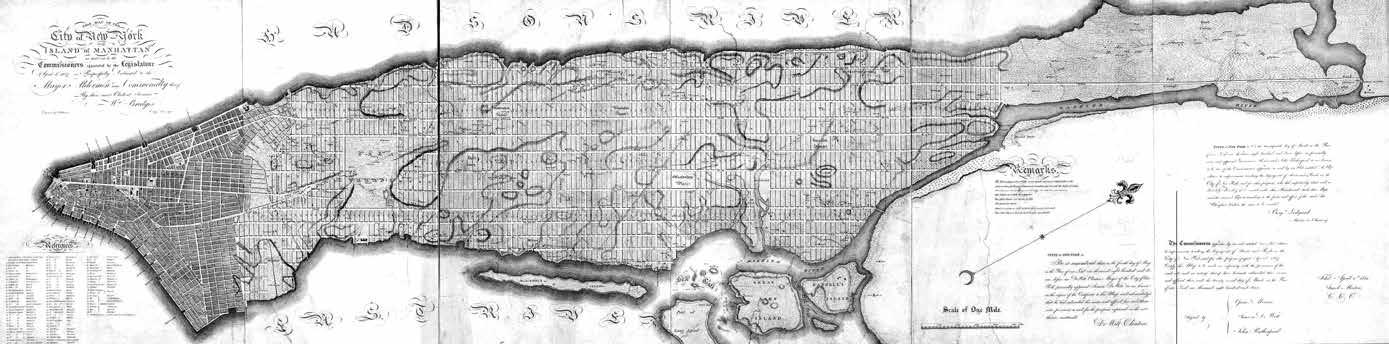

While Napoleon was conquering Europe and tearing down city fortification walls, a startling event was initiated in New York City: “The Commissioner’s Plan” for the expansion of the city was approved in 1811. A regular grid composed of 200' x 800' blocks, divided into 25' x 100' parcels, was proposed to cover the entire undeveloped part of the island, flattening the topography as it moved north. Minor variations of the plan appeared until 1821, and by 1836, as the Coulton Plan illustrates, the armature of New York City was established.14

The first half of the nineteenth century in Europe— at least until 1835 or ’40, if not 1850—was involved on the one hand with the late phase of Neoclassicism: detached, small-scale buildings, and the beginning of suburban residential quarters in Paris.

On the other hand, since the late eighteenth century there were the important urban interventions of George Dance, John Nash, and the Napoleonic forays into urban design by Percier and Fontaine. But for the most part, these were the beginnings of unified nineteenth-century street design, not the large-scale production of urban fabric. These projects did, however, establish a precedent, and an unbroken line of development for the Parisian boulevards of Haussmann and Napoleon III.

Another notable early nineteenth-century planning model—one that could be a precedent for the many late nineteenth-century urban expansion plans—was the continued planning of the “great estates,” such as Belgravia, in London. This tradition of new, planned towns-within-the-town began in the seventeenth century and continued unabated throughout the first half of the nineteenth century (while Napoleon III was in exile in London). None of these plans were on the scale of the late nineteenth-century expansion plans, but other than this, there appears to be no obvious, continuing tradition of town planning that could be drawn upon to respond to new demands that began around the mid-nineteenth century.15

ORO Editions

1. Commissioners Plan for Manhattan, Bridges,1811

2. Plan of St. James, 1660s

View

t he l Ate n ineteenth c ent U ry

Within a relatively brief period—approximately from 1860 to 1890—very sophisticated plans for the urban expansion of major American and European cities were designed, drawn up, and implemented by architects and engineers. These plans included comprehensive infrastructure (sewers, water, lighting), urban parks and landscape, new methods of finance, accommodation of increased urban movement via carriages, and the incorporation of a fashionable new building type, the apartment building

One notable characteristic of these nineteenthcentury urban expansion plans—one that they did share with the long tradition of planned towns—is that their urban authors did not draw buildings. During this time, the production of urban plans consisted of designing and drawing cities, and parts of cities, not buildings.

In other words, consistent with M. R. G. Conzen’s theory of urban geography, urban planners designed the public realm of the city—the streets, blocks, and squares, and sometimes the parcel divisions—while architects designed the buildings within the urban framework. This period, on the eve of massive change, might therefore be seen as both the zenith and the twilight of what used to be called town planning.

ORO Editions

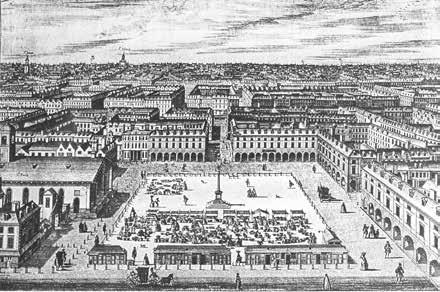

2. Expansion plan for Madrid, 1860

3. Aerial plan of Back Bay, Boston, begun 1859

1. View of Champs Élysée, Paris

p roto - m odernist t own p l A nning

With the rapid urban expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century, new urban issues emerged. Architects and town planners of the period between 1890 and 1910, however, did not question the validity of the traditional elements of the city: the streets, squares, and blocks. Rather, they tried to rationalize them and adapt them to “modern” demands. They also still utilized urban building types—buildings that defined the public space of the city.

This general consensus unites such otherwise disparate planners as Eugène Hénard, Camillo Sitte, Joseph Stübben, and Otto Wagner; and this consensus renders trivial the commonly framed oppositions, such as that between Sitte and Wagner. As either traditionalists or proto-modernists, these planners were united in their acceptance of the city. It remained for Le Corbusier and the other modernists to jettison the city.

The proto-modernists did, however, begin to draw buildings as well as plans; buildings tended to become as large as blocks; and planners did propose state management and distribution of land, as well as monofunctional zoning—all characteristics of later modernist planning.

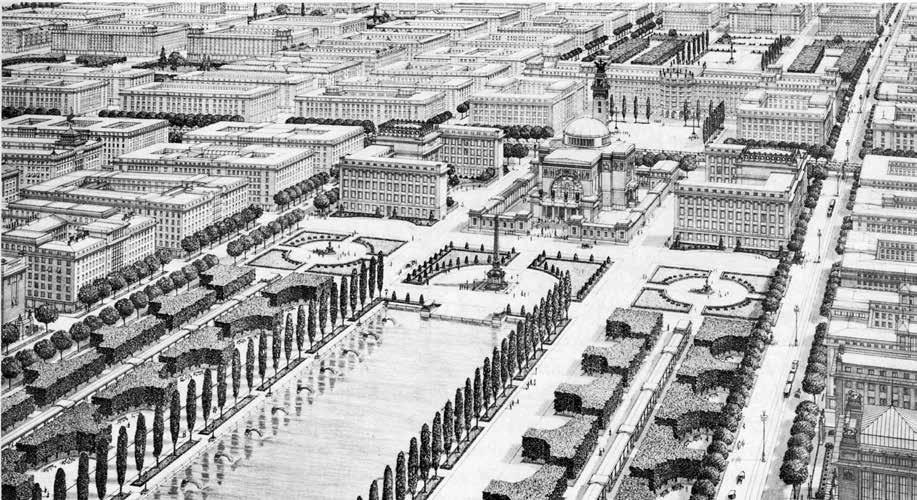

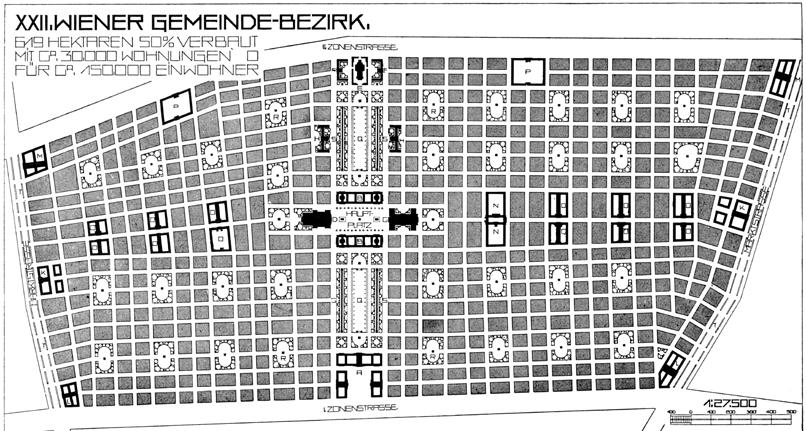

ORO Editions

1. Perspective of the core of the expansion plan for Vienna, Otto Wagner, 1910

4. Expansion plan for Vienna, Otto Wagner, 1910

2. City of the Future, Hénard

3. Intersection, Hénard

m odernist t own p l A nning

The original thesis of this study was that sometime in the early 1920s, architects and town planners, such as Le Corbusier and his CIAM colleagues, began to draw buildings rather than cities, and that this has created confusion and promoted the degradation of the urban environment.

Until this time there had been a symbiotic relationship between architecture and urbanism: architectural styles could change as desired because there was hegemony of the urban realm; when architecture achieved hegemony over urbanism, however, the public realm disappeared as a legible, spatial entity.

New, fundamentally antiurban architectural typologies conspired with increased freedom of movement and monofunctional zoning to challenge the hegemony and validity of traditional urban form.

This period marks nothing less than a complete inversion of urban form and design principles. In simple terms it marks the death of the street, the end of legible urban space, the end of mixed-use zoning, and the hegemony of movement over place.16

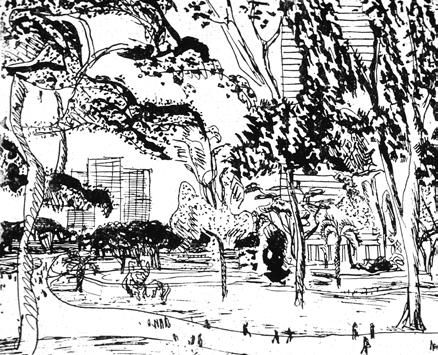

2. Le Corbusier, Ville Radieuse, 1933

1. Le Corbusier, Ville Radieuse, Plan, 1933

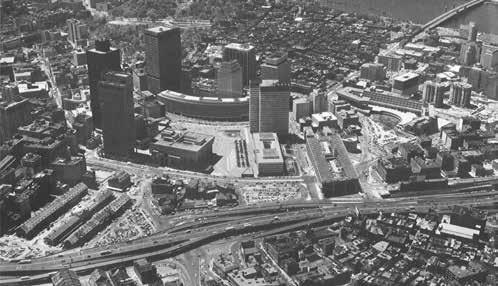

p ostwA r p l A nning

The Second World War was devastating for many European cities. Dresden was almost totally destroyed. Before the war Dresden had been one of Europe’s most beautiful cities. Afterward, there were competing strategies for rebuilding the city, but the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 freed the planners to establish a socialist utopia based on modernist typologies and principles.

In America, “urban renewal” accomplished at the hands of planners what the bombings had in Europe. White flight to the suburbs and the Highway Act conspired with the planners in the disintegration of American cities. The influx of European modernists, such as Gropius (and later Sert) at Harvard, and Mies at Chicago, helped ensure that reconstruction would be based on modernist—fundamentally anti-urban—principles.

Beginning in 1959, the successors to the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), the members of Team X, tried to modify and transform the limitations of CIAM principles, and to extend their influence in America. Jose Sert introduced the urban design program at Harvard in 1956, and although his was a “softer” agenda, it was nevertheless an extension of CIAM principles.17

3. Contemporary aerial view of the inner city of Dresden looking west

1. Aerial view of the historic core of Dresden, before the war

4. Aerial view of the historic core of Boston, before the war

6. Aerial view of the historic core of Boston, 1970s

5. Aerial view of the historic core of Boston, 1960s

2. Aerial view of the Prager Strasse, 1960s

t he r ecovery o F the c ity

As the limitations and reality of the modernist agenda became visible in the late 1960s and early 1970s, reaction against CIAM planning principles had already begun—as early as the 1960s. For many architects and urbanists the reconstruction, or rediscovery, of the city—its typologies and morphology— was a prerequisite for the recovery of quality urban life.

In Europe, the so-called rationalists—Aldo Rossi, Rob and Leon Krier, and others—began to revise architecture within the context of the city. As Andres Duany has pointed out, Leon Krier was the first in forty years to comprehensively draw the city, and his principles were, brashly, the complete opposite of those of CIAM.

In America, urbanists from Jane Jacobs to Denise Scott Brown advocated a gentler return to traditional urban ideas. The preservation movement and “advocacy planning” both emerged in resistance to the destruction of neighborhoods and cities.

Also, during the 1960s and early 1970s, Colin Rowe and colleagues at Cornell University began to explore ways to combine modernist and normative urban form strategies in order to produce a habitable contemporary urbanism. For about twenty years the urban design studio at Cornell was a continuous urban research lab.18

ORO

1. Leon Krier, La Villette, Perspective, 1976

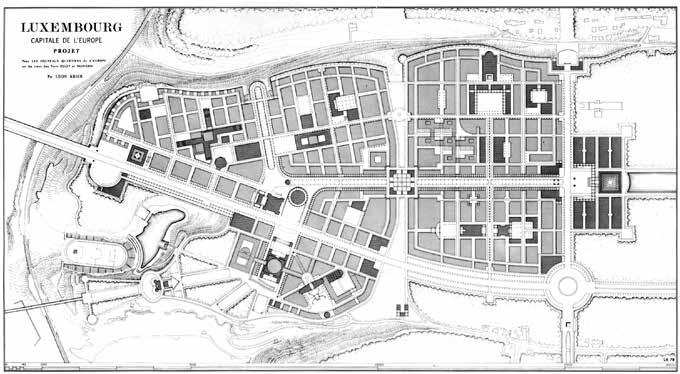

2. Leon Krier, proposed plan for Luxembourg, 1978

3. Steven Fong, Marylebone Project, 1979

4. Rowe Studio, Buffalo, model, 1966

5. Rowe, et. al., Roma Interrotta, 1978

c ontempor A ry A rchitect U re

Despite efforts to redefine architecture and urbanism during the last quarter of the twentieth century, contemporary architecture has become ever more narcissistic and autonomous—the result of a three-hundred-year formal and social transformation, from near complete hegemony of the public realm in the seventeenth century to a no less tyrannical hegemony of the private realm in our time. The physical civic realm has all but disappeared.

Legible urban space is required for a physical public realm, but little architecture today contributes. This may be the most crucial professional issue of our time.

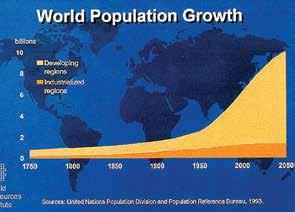

As the world continues to urbanize (over 50 percent of the world’s population now lives in cities); as population increases (it is predicted to increase from six billion to nine billion by 2050); and as the world’s resources diminish (especially petroleum); it will become imperative to reexamine architecture and its relationship to the city.

ORO Editions

2. Aerial perspective of “Downtown” Dubai

1. Popstage, Breda, NL, E. van Egeraat

3. London City Hall, Foster + Partners

4. Performing Arts Center, F. Gehry 5. Global urbanism, W. Alsop

t hree c ontempor A ry n ew t owns

Despite the propensity of many contemporary architects to favor narcissistic anti-urban buildings, some of a series of new, planned towns have explored the relationship between architecture and urbanism.

Three such new towns are: Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, by Foster + Partners; Poundbury in Dorset, by Leon Krier; and Rak Gateway in Dubai, by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

All three are compact, with finite limits, and all three claim to be “sustainable,” even though two are located in the desert. None of the three have traditional urban design plans showing blocks and parcels, and all illustrate building types and volumetric development, and sometimes the architectural character of the buildings.

One of these new towns has been built (Poundbury), and has been socially and financially successful—to the consternation of “avant-garde” architects.

ORO Editions

4. Aerial perspective of Masdar City

3. Aerial perspective of Masdar City

2. Plan of Masdar City, Abu Dhabi

8. View of town square, Poundbury

7. Aerial perspective of Poundbury

6. Plan of Poundbury, UK

5. View of Poundbury

12. Aerial perspective of RAK city center

11. Aerial perspective of RAK Gateway

10. Plan of RAK Gateway, Dubai

9. Perspective view of RAK Gateway

1. Perspective interior view, Masdar

c ontempor A ry

e nvironmentA l i ss U es

Data indicate that in the beginning of the twenty-first century, our planet has passed into an irreversible environmental crisis—one that, without intervention, could result in the extermination of human life within the not-too-distant future. This outcome may still be averted, but it will be difficult, and life will be radically different than that of the twentieth century.19

The size and lifestyle of our human population are the drivers of this crisis through production of food and materials, consumption of renewable and nonrenewable resources, and waste and pollution.

The Earth can naturally support about 2.5 billion people. Population size beyond that has only been supported by technology in the production of food, with some segments of world population living in marginal conditions at best. Production of food has plateaued, however, and population continues to increase.

The production of material goods in the developed part of the world has also increased to an extravagant degree. The lifestyle to which we have become accustomed demands the production of ever more massive amounts of “stuff.”

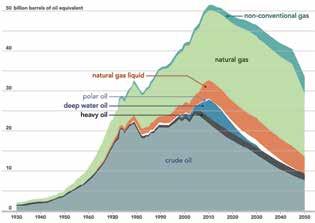

c ons U mption

Humans are consuming the Earth’s nonrenewable resources, such as petroleum, gas, coal, and metals, at a geometrically increasing rate. There are relatively fine-grained arguments about the remaining amounts of these resources, but nonrenewable means that when they are gone, they are gone. Tragically, an excessive proportion of nonrenewable resources are squandered on America’s predominantly suburban lifestyle. We have 4.6 percent of the world’s population, but we use almost one-third of the world’s petroleum. World population is also consuming renewable resources at a greater rate than can be replenished. As population increases, consumption grows, and as diets in the developing world become more proteincentered, consumption expands further.

ORO Editions

4. Suburban family

2. World population growth, 1750–2050

6. West Virginia strip mine

3. Atlanta highway infrastructure

1. View of Earth from space

5. Nonrenewable resource depletion

p oll U tion A nd g lob A l w A rming

The results of our complex, modern lifestyle of consumption are no longer unseen, but visible: from toxic pollution of the food chain and water system to melting ice and snow caps, rising sea level, acid seas, deforestation, desertification, fresh water loss, soil erosion and loss, and species extinction. Of all of the results of our lifestyle, however, global warming is by far the most devastating. We can live without oil, but we cannot live on an excessively warm planet.

The political excuse for non-action is always economic. But remediation is more expensive than prevention, and extinction is even cheaper. All we have to do is continue what we are doing, and natural forces will purge the Earth of the problem—us. Even if it takes a millennium or more for the Earth to come back to equilibrium this is an insignificant period in the timeline of the world.

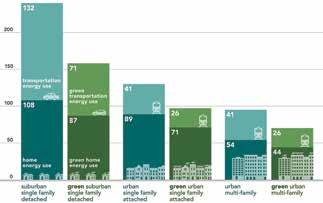

U rb A nism A nd the e nvironment

What do environmental issues have to do with architecture and urbanism? Almost everything. The form of our cities and buildings is the solution, not the problem. Our whole culture is based on the idea of limitless resources and continuous growth, and we have become so accustomed to the idea that we have forgotten that we live on a finite planet. Urbanism is crucial to a solution of environmental problems as it is the most efficient form of inhabitation with the smallest ecological footprint on a per capita basis.20 We need to use fewer resources and less infrastructure, and create less pollution. This means living smaller, closer, denser, simpler—more urban. We need to (again) conceive architecture and urbanism in these terms.

Most architectural and urban design proposals today derive from the facts—the status quo—of our contemporary society, not from scientific environmental projections. From urban farming to driverless cars to social media to big data, most proposals are technologically hopeful extensions of the status quo rather than radical rethinking of the basic conditions of the way we live.

Our industrial society has evolved incrementally over a century and a half to our current environmental crisis with most of that evolution happening within the last fifty or sixty years. To continue to rely on incremental change without a long-range strategy would be catastrophic.

p rinciples F or A s U stA in A ble U rb A nism

The basic form guidelines for good, sustainable urbanism are simple. They are revolutionary only because they have been abandoned for so long that their value is no longer recognized. These are a good start:

Dense, contiguous urban buildings forming modestly sized blocks;

Streets as narrow as possible, designed primarily for people, not cars (or diesel buses);

A pattern of plazas or squares of moderate size;

Neighborhood and civic parks and gardens;

Mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods;

A legible civic structure of public spaces and buildings; and,

Efficient public transportation systems.

Technology has been the enabler to the problem of population growth and lifestyle. It is important, but should be used to enhance basic decisions, not supplant them—the final step, not the first.

ORO Editions

1. Air pollution in Shanghai

4. Bordeaux urban life

3. Comparison of single-family energy use

2. Modern life

From the earliest planned Greek cities to the railroad age, Western cities had several characteristics in common: relatively small size, dense urban fabric, legible public spaces, multifunctional neighborhoods of walkable dimensions, limited vehicular circulation, and a limited range of known building types.

Maps of many of these cities were published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in the middle of the nineteenth century. Beautifully drawn, these maps illustrate the cities at the last moment of preindustrial innocence, just as the railroads enter.

ORO Editions

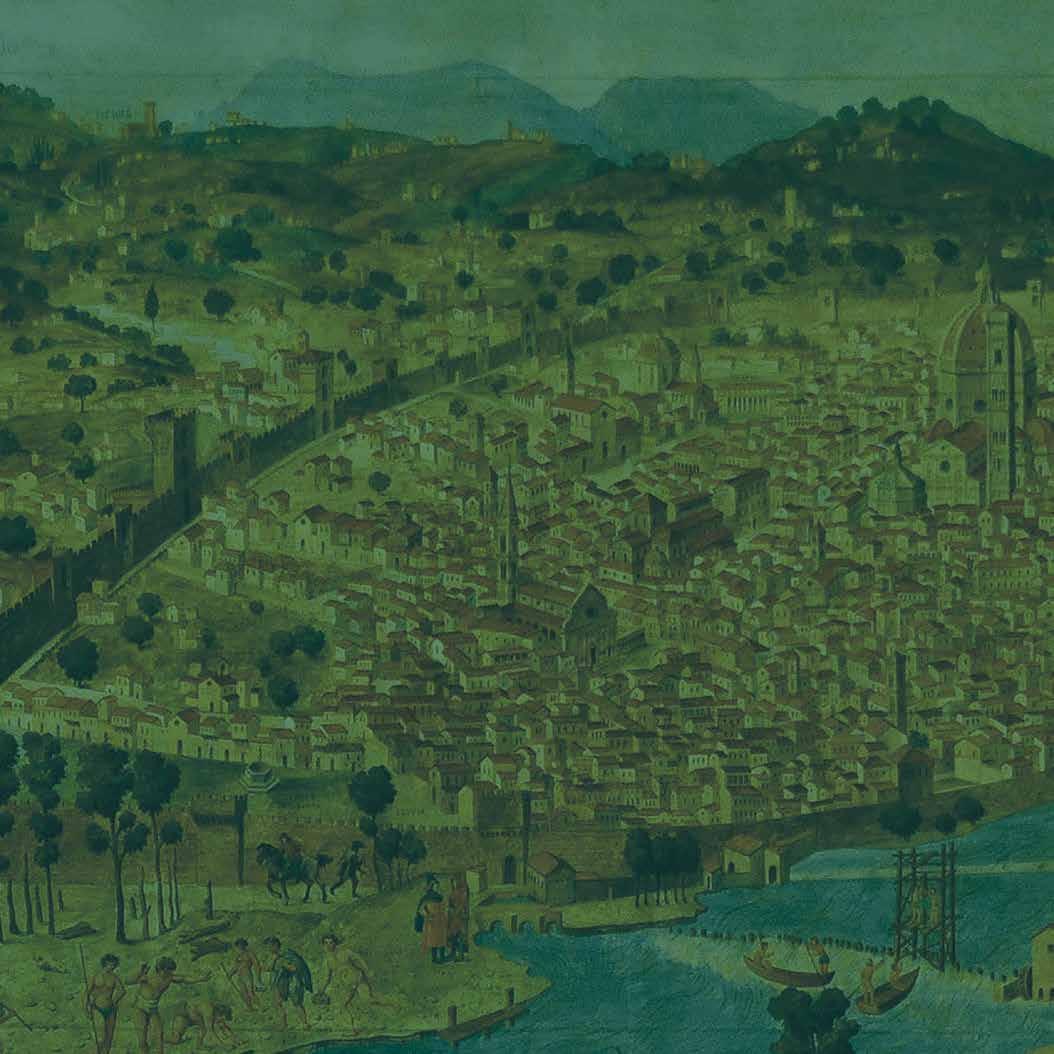

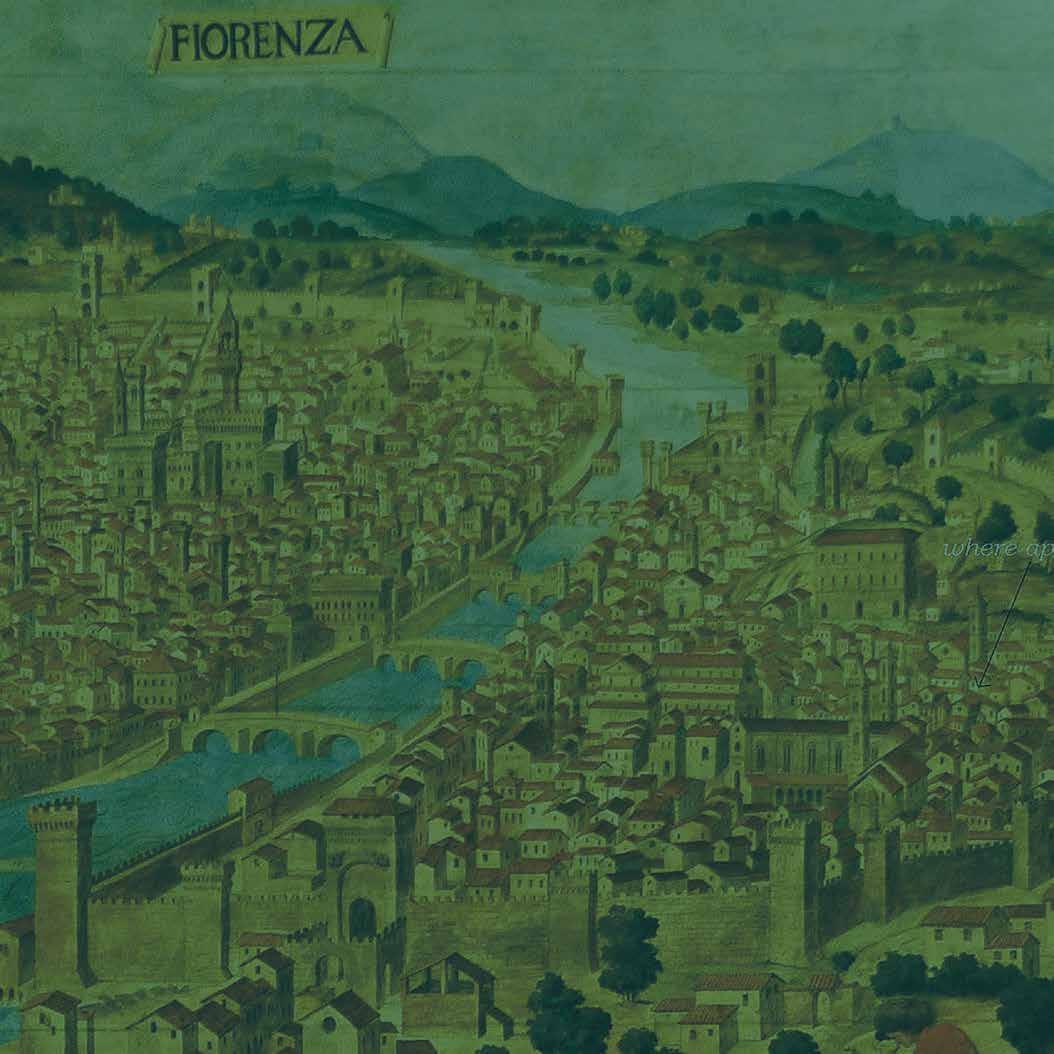

Catena view of Florence

Editions

Map of Greek and Phoenician colonies in the Mediterranean