Rebel Video

London Bern Lausanne Basel Zurich

Basel Bern

Lausanne

Christian Schmid Researching the City with Video 229 Thomas Krempke Züri brännt as a Collective Process

253

Samir Jamal Aldin We’ve Already Made 100 Films but What We Really Sell Are Ideas

269

Margrit Bürer Participatory Video and Its Impact 281 Christian Iseli Look Me in the Eye! The Direct Gaze into the Camera in the Documentary Interview

On the Beginnings of the Video Movement

In the beginning was the Portapak

In the late 1960s, a portable, battery-operated recording system bearing the odd name “Portapak” came onto the market. With the Portapak, sound and image could be recorded on a magnetic tape and played back directly after the recording or at a later point in time. The Portapak comprised the videotape recorder and a light, electronic camera with a monitor. The home video recorder (VCR) later developed from this first, portable recording device. The Portapak was also present at the start of the alternative video movement—community video—and promised a new, participatory way to handle image and sound.

In the United States and Canada, artists, students, hippies, creative inventors, and political activists from the 1968 movement were the first to take an interest in the Portapak. The nascent video scene in New York declared in their journal Radical Software:

Power is no longer measured in land, labor, or capital, but by access to information and the means to disseminate it. As long as the most powerful tools (not weapons) are in the hands of those who would hoard them, no alternative cultural vision can succeed. Unless we design and implement alternate information structures which transcend and reconfigure the existing ones, other alternate systems and life styles will be no more than products of the existing process.1

In comparison to 16-mm film, video was relatively inexpensive. The twenty-minute tapes could be reused multiple times, enabling savings on film material; and there was no need for developing in expensive labs. Recordings could be viewed directly. After a brief introduction, camera and recorder were easy to operate and the video recordings

So Much Energy Came out of It

I grew up in Bromley, which is a South London suburb right on the edge of the countryside. The country was next to us. My parents had moved there before the war, from what was called the Medway Towns. Our house was a three-up, two-down house on a suburban street called Meadway. Other names were Cherry Tree Walk, Bourne Vale, and all those slightly bucolic names. It was kind of a dream suburb for people to live. I remember seeing the adverts for it from the 1930s. It was promoted as somewhere to realize your dreams, both town and country in one place.

Caring Methodists

The most distinguishing thing about us is that we were Methodists. Serious Methodists, Methodism was a kind of tribe, really. A lot of the rest of the street went to the tennis club, or did those kinds of things, whereas my parents went to the church. My father was a lay-preacher, my grandfather was the equivalent of a bishop, and my brother became a Methodist minister. My dad was the head of the Sunday school. I used to go to church two or three times a week, and I wasn’t allowed to go out and play on a Sunday. So they were quite strict Methodists. They didn’t drink. I always felt slightly outside, or I was aware the family was slightly outside the

Murchison Tenants

West London Media Workshop

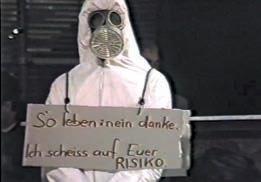

Der Rest ist Risiko

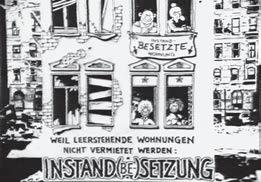

Sus Zwick & Videogenossenschaft Basel