This is a compendium of incidents, observations, and discoveries on travels around the world. I’ve drawn on memories, journals, articles, and correspondence, arranging the notes in a rough chronology and by location. Some are composites, of repeated trips to favorite cities and countries over many years.

Early expeditions were loosely structured and serendipitous. As a film programmer in the 1970s, I would take a few days off from screenings in exotic locales to look around. I’ve spent the past four decades writing architectural books and articles, planning every journey in detail to explore a diversity of buildings and meet their authors. So the tone shifts, and there are digressions on film, design, and art along the way.

Even the shortest journey can bring rewards, and I’ve been a compulsive wanderer from the time I could walk. In this quirky travel memoir, I’ve recalled some of the places and people that seized my attention, but have omitted many more. There seemed no point in adding to the voluminous coverage of famous buildings, so (with a few exceptions) I’ve stayed off the beaten path, especially in such familiar locations as London, Paris, and Rome. I hope these recollections and images may prompt readers to make their own discoveries and share my nostalgia for what has been lost. — m.w.

Wayne Ratkovich, a visionary developer, to save the mid-town Wiltern Theater, and rallied public support with The Best Remaining Seats, a series of ten classic movies introduced by their stars or directors, most of whom were older than the theaters.

It was a challenging task. We had almost no budget and only a few weeks to clean, repair, and re-light theaters that had been sadly neglected. Happily the projectors were still in working order. Lilian Gish launched the series at the Wiltern, a pink and gold gem of Art Deco ornament within a green terracotta tower. The Wind, made in 1928 by Victor Sjöstrom, was filmed in Death Valley, and she described the ordeal of filming in a sandstorm, whipped up by studio fans in the searing heat of summer. The arts editor of the LA Times assured me that no one would come to the shows on Broadway – Angelenos knew it was far too dangerous to be on downtown sidewalks after dark. In fact, every performance was SRO and we took the series to the Arlington Theater in Santa Barbara with Mel Oberon hosting, and to Catalina Island, where Douglas Fairbanks Jr. introduced The Black Pirate. As Variety would have said, the series was boffo, and the LA Conservancy has reprised the concept as a fundraiser over the past four decades.

Lillian Gish was one of the first and greatest film actresses, and at age 87 she could outlast audiences a quarter her age. She still had the porcelain-pretty looks of a silent movie star, but it was spine that carried her through. We went on tour to palaces in Columbus, Milwaukee, and Chicago in mid-winter, and she spent an hour on stage after each showing recalling her years with D.W. Griffith when she had to perform her own stunts. In Way Down East she clings to an ice floe in the Connecticut River before being snatched to safety, and the scene still provokes incredulous gasps. [1979]

After 15 years in Britain and the US, film programming lost its allure and a real-estate boom frustrated my attempt to establish a cinematheque in LA. AFI and I amicably parted ways and I was suddenly unemployed. I dreamed of producing a feature and agreed to help JoséLuis Borau, a Spanish writer-director, find backing for his script – a contemporary version of Romeo and Juliet set on the Mexican frontier. It was coldly received; a similar movie starring Jack Nicholson had just flopped. Job interviews were inconclusive and proposals went unanswered. A friend suggested I use my free time to take a long vacation. Pan Am was offering an 80-day, 12-stop round-the-world flight for only $1,279 and impulsively I bought into the adventure.

Planning a journey can be as rewarding as the experience of travel. I spent a month poring over maps, fantasizing about all the places I had never been, and reading every travel book I could find. Unknown to me, Pan Am was in sharp decline, pruning its routes and patching up decrepit planes. As my list grew longer the options shrank. Finally I had a schedule: Hawaii to southeast Asia, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and home, along with the mandated visas and shots. Remembering the hapless William Boot in Scoop, who was burdened with a plane-load of excess baggage, I decided to travel light. A few shirts, non-crease pants, and sneakers, plus a lightweight high-tech parka guaranteed to retain or deflect heat, and to be detectable by radar should I stray off course. I packed and set off for LAX on the first leg of my journey.

The departure lounge was full to overflowing, with passengers from the previous night’s flight, which had been canceled when a door fell off the plane. They all had reservations; I was flying on stand-by. Two hours passed as the twin loads were fitted into one plane and I

Nazi Germany. In Europe their work was scattered and they had to struggle to express themselves. Here they were given a free hand and were able realize their dreams. It shows what might have been—in Germany and other countries—had history taken a different course. I was thinking of this over dinner when Gideon’s phone rang. A friend was calling to say that Yitzhak Rabin had been shot at a peace rally less than a mile away. He sat numbly, not speaking, and I shared his grief. I remembered Rabin from when he was Israeli ambassador to Washington. We even stood in line together for the Eastern Shuttle to New York, in those far off times when he didn’t need a bodyguard. Now his security detail had failed him. For both of us it was the assassination of JFK once again: the death of hope, and a fatal turn for the country.

Two days later I was on the streets of the White City when sirens sounded and everyone froze for two minutes of silence. Even more moving than the broadcast of the funeral were the programs that followed. Israelis, despite their differences, are as tight-knit as a family; only the black hats failed to mourn that day. For the first time since 1963, television realized its potential to respond to a people united in sorrow. For once it was not shallow, exploitative, and voyeuristic, but healing and sincere. Leah Rabin and Shimon Peres paid their tributes. Young people sat silently holding candles, looking lost and bewildered, as an older generation sang songs of lamentation. Shalom: peace and farewell. How far has Israel fallen from the promise Rabin offered. Jewish extremists murdered British officials in the quest for independence; now their heirs occupy the seats of power, posing as great a threat to the integrity of the country as the Arabs. [1995]

No country provides more surprises than Japan, and after a dozen trips I still felt as though I had strayed onto another planet. Tradition and technology are fused in an inwards-looking society that shut itself off from the outside world for three centuries and is still xenophobic. Contradictions abound: speeding on the Shinkansen through a landscape of paddy fields and smoking chimneys to sleep in a ryokan; strolling an ancient garden that’s flanked with vending machines; confronting the language barrier in a country where only Japanese is spoken but English signs abound. Foreigners are treated with exquisite politeness, but the gaijin are secretly perceived as red-faced barbarians.

In 1978, my friend Patrick Macrory took a sabbatical from his legal practice to teach law in Tokyo, and invited me to stay with his family. I flew over by Cathay Pacific; the screening of Oh God! was partially obscured by the shaven heads of five Buddhist monks in the front row. A day after arrival we were off, exploring the newly completed megastructures of Kenzo Tange, ancient temples, and the craft stores of Akasuka. There, I bought a hand-painted kite from an old man with a wispy white beard, and a T-shirt

All that’s lacking is the Sunday evening paseo, which I experienced in San Miguel de Allende. By 8 pm every bench in the Jardin de Allende was full and the mating dance began. Girls paraded counter-clockwise around the plaza, arm in arm and three abreast, gossiping but watchful, in a progress as brisk as a cotillion. Boys made a perfunctory clockwise movement, but most darted into line to walk with the girls or draw them aside. Foreigners and couples threaded in between, balloon sellers worked the families on the benches, a band blasted away from the kiosk. Nothing slowed the youthful carousel, which revolved late into the night. [1988]

Luis Barragán built very little during his last 40 years in Mexico City, but each project is a portrait of an inspired architect who had the means and will to follow his solitary path. The elemental simplicity of his houses is a fusion of modernism and the rural vernacular, mass and void, rough plaster and refined proportions. On a recent trip, I was able to visit four of them by appointment. The architect moved from his home city of Guadalajara in the early 1940s and spent the rest of his life in the Casa Barragán. Behind its anonymous exterior little has changed since his death in 1985, thanks to the housekeeper, Ana Luisa.

A lofty living room doubles as an office, littered with books and papers, and a cross of glazing bars divides a wall of glass that frames the jungle-like garden. Stairs of black volcanic rock are lit from above, and the eye is drawn up to a gold canvas by Mathias Goeritz, a close associate of Barragán. A simple wood sidechair from a farmhouse kitchen is set off by a bright pink wall. The bedroom is spartan and a crucifix hangs over the single bed. Barragan was a devout catholic and I remember a whip and scourge from an earlier visit, but this has been edited out. In the studio, cantilevered wood treads lead up to a roof terrace that is fully enclosed by colored walls.

The other houses play variations on these themes. Casa Prieto is the largest and was meant to be a model for Jardines de Pedregal, a planned community that would respond to the volcanic rockscape south of the city. In contrast to the others, the colors are subdued: dusty pink, gray, and blue. Jorge Covarrubias, the architect who restored the house for a new owner, insists that “Barragan is not about color but atmosphere. Choices had to be made – not always the first layer of paint.” Living spaces flow into each other as the house steps

down a slope from the entry court to a pool court with rock outcrops. Light reflected off walls inflects their color, turning pink to pale blue-gray. The shifts of level and generous proportions, broad pine floor boards and massive wood furniture give this house the elemental quality that characterizes Barragan’s best work.

The Cuadra San Cristobal is located in a northern suburb of Mexico City. On the tedious drive out you pass the cluster of colored obelisks that Goeritz designed for Satellite City, another planned development that was hijacked by speculators. The Egerstroms, a Swedish couple who loved horses, commissioned a modest white house and an expansive stable yard in the gated community of Los Clubes. Pink walls are cut away to frame the house and are highlighted by panels of blue and violet, with a row of stables to one side. A cantilevered conduit gushes water into a shallow pool: an image that has long defined Barragán to the world. Just up the street is a similar spout and pool to serve horsey neighbors.

Barragán came out of retirement to design a double town house for the Gilardi family, and the present owner, Martin Luque, allows visitors to immerse themselves in fields of vibrant color as they explore the ground-floor rooms. A gallery with yellow-lined openings opens onto an indoor pool with blue walls and an intense red shaft. A ray of sunlight creates a diagonal accent. The richly grained stone floors resemble wood. A glass door opens onto the central patio, which was built around a jacaranda tree, with a blue wall that merges into the sky, and another of pink. Unrailed, polished wood stairs lead up to a living room that opens onto a little courtyard and a library. At every turn, shutters open to reveal another vista. [2017]

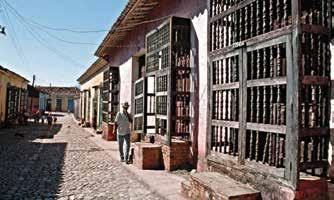

The highlight of our trip was Trinidad, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The town grew rich from the yield of sugar mills through the 19th century but then went into a long slumber. Anywhere else in the Americas such a gem would be a parking lot for cars and tour buses, and the main street would be lined with souvenir shops and plastic signs. Nothing disturbed the tranquility of Trinidad at sunset but a couple of cowboys from the sugar plantations clip-clopping over the cobbles, and some musicians warming up for an evening gig. Faces appeared behind the window grilles but the streets remained empty. Next day, the town came alive, and the architect who showed us the buildings he had restored stopped a hundred times to hug his neighbors. Here in the country, we could recapture the lazy, pre-revolutionary rhythms of Cuba, where people may make a living from the land and ignore the sloganeering. [2000–01]

I first went to Brazil in 1971 when filmmakers and musicians were finding inventive ways to tweak the noses of the military junta and avoid censorship. Monday through Friday I selected movies—How Tasty was my Little Frenchman was a great find—for a program in Washington, and nights I went to concerts by Antônio Carlos Jobim, Maria Bethânia, Baden Powell, and other greats, where young audiences sang the lyrics of banned songs as the musicians played along. At weekends I joined a couple of journalists at noon, spending a few hours on a specific stretch of Leblon Beach in company with their professional peers. Back for lunch at 4, a long siesta in their cool apartment and then to dinner around 11. Four years later I returned and knew I would find them at the same spot, chatting away to friends and ignoring the nubile bodies playing paddle ball. I made an excursion to the newly completed center of Brasilia and drove south from Rio to meet Roberto Burle Marx, the white haired maestro of landscape design.

Those brief encounters inspired a later trip to explore the work of Oscar Niemeyer, the architect who embodied the sensual Carioca spirit and put Brazil on the international map.

In 1939, when he was completing designs for the Ministry of Education and Health in downtown Rio, I could have flown there from New York on the Pan American Clipper, landing in the bay beside the Sugar Loaf mountain. Today, the flight is prosaic, though much faster, and you reach the waterfront though a decayed and horrendously congested city. Happily, the essentials haven’t changed. My taxi raced along the waterfront, skirting the promenade with its undulating mosaic waves, and the terminal where the flying boats used to dock.

Health has been supplanted by Culture, and the Ministry has been renamed Palacio Gustavo Capanema for the progressive politician who threw out the retro competition-winning design of 1935, and hired a bunch of adventurous young architects.

Best known as Italy’s Detroit, Turin is a treasury of unique architecture, from the baroque churches of Guarino Guarini to the Mole Antonelliana, a towering synagogue turned movie museum, and Lingotto, the former Fiat factory with its rooftop test track. But the ghost one keeps encountering is that of Carlo Mollino (1905–73), a flamboyant contemporary of Gio Ponti –and almost as versatile. He designed houses and a riding club, rebuilt the Teatro Reggio, and created eccentric chairs and tables that go for astronomical prices at auction. He also found time for erotic photography, downhill skiing, and racing cars.

The Casa Mollino is run as a private foundation by family members, one of whom guided me around. Mollino never lived here—he had four other houses—and he furnished this apartment in 1968 as a self-portrait and a surreal work of art that blends personal references with inherited furniture. After his death an engineer lived here, and the apartment had to be restored to its original state, based on Mollino’s detailed plan.

A vintage milking stool stands next to the thin-backed white chair it inspired. The dining room has an oval table supported on fluted classical columns, surrounded with Eero Saarinen’s tulip chairs. A German forest engraving frames classical doors. The bed is in the form of an Egyptian boat with mystical signs that indicate a voyage into world of dead. Velvet curtains can be drawn to close off each room. Claustrophobic and exhilarating by turns, the apartment is the embodiment of decadence and the free spirit of a true original. [2009]

Architect, designer, artist, and founding editor of Domus – Gio Ponti (1891–1975) was a Renaissance man for our own times. I have had the good fortune to explore his houses and churches in Milan, stay in the shadow of his Pirelli tower, and sit on his Superleggera chair. Highlights of a recent trip to Italy were his interiors for an ancient university and a cool modern hotel.

The University of Padua was established in 1222 by students from Bologna and everyone of importance seems to have taught there, from Dante to Copernicus and Galileo, drawn by its tradition of tolerance. Today, there are 60,000 students, giving it a commanding presence in a city of 200,000. In 1939, a courtyard of the Palazzo Bo was remodeled and Ponti was

Cruising around the waterfronts of Stockholm on a fine summer’s day is one of the most civilized pleasures I know. The city covers 14 islands of varied size, a tiny part of the archipelago of 24,000 rocky outcrops that extends from Lake Malaren out into the Baltic. The water acts as a giant mirror, intensifying the cool northern light, and enhancing the fanciful skyline. The islands break up the mass of the city, giving it an intimacy and charm that belies its size. Monuments—including the landmark City Hall and a forest of church spires—stand out boldly from streets and promenades of uniform scale and height. The cobbled lanes of the old city frame views of other islands, leafy parks, and an animated mix of ferries and sail boats. Though Stockholm has an abundance of restrained modern buildings, it preserves the rich character of earlier centuries in which architects competed to impress.

A short walk over the bridges to the north and west takes you past the House of the Nobility (Riddarhuset) a triumph of the baroque with its giant Corinthian pilasters and graceful copper roof, and on to City Hall, the finest monument of the last century. Its tall corner tower has a fanciful lantern topped with three crowns, and they are echoed in turrets that protrude from the tall, brick walls. It’s a hybrid of the National Romantic style that flourished in Scandinavia in the early 1900s, and the clean lines and bare surfaces of modernism. The mosaic-lined Golden Hall, where the Nobel Prize ceremony is held, was inspired by St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

I crossed the bridge to the irregular oval of Skeppsholmen. Rafael Moneo’s Museum of Modern Art has one of the finest collections of 20th-century paintings and sculptures in Europe and the architectural museum also presents lively exhibitions. A ferry carried me to the waterfront Vasa Museum, a soaring modern container for the royal flagship that capsized and sank on her maiden voyage in 1628. The richly carved hull was raised and restored 50 years ago and you view it close-up at different levels. A short walk inland brings you to Skansen, the word’s first open-air museum of rural life and a model for those that have followed. Farm buildings, churches, a manor house, and a village school were brought here from all over Sweden, plus wild and domestic animals, transporting city folk to a pastoral world that still survives in remoter parts of the country. Another ferry carries you back to the central square of Nybroplan, past the palatial facades of Strandvagen.

There’s a design store named for the architect, Gunnar Asplund, who designed two of the city’s masterworks. The Public Library is a lofty book-lined rotunda of the 1920s, and Skogskyrkogarden, which translates as Woodland Cemetery, is a serene enclave with

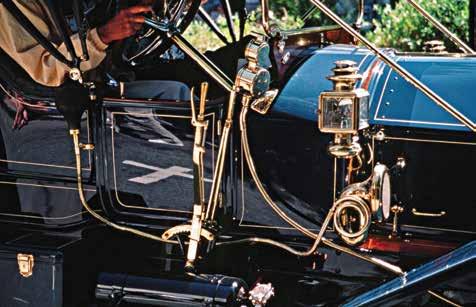

trumpet-like horns and—most covetable and distinctive—hood ornaments. Like the armorial bearings of chivalry, these mascots were proudly flaunted and a few became as famous as the cars they adorned. These classics make me deeply covetous and it’s just as well that only millionaires can afford to restore and maintain them or I might be tempted to plunge. My 1968 Mustang convertible occupies middle ground between style and practicality and, as long as it runs smoothly I’ll resist the lure of European sirens and vintage chariots. Look but don’t touch, as owners tell the admiring throng. [1999]

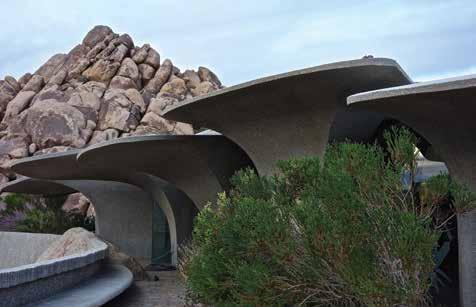

The High Desert House near Palm Springs is the masterpiece of Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, an organic architect who draws inspiration from nature and from his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright. Beginning in 1957 at age 23, he created a succession of houses and commercial buildings that shape space in daring ways, but his originality condemned him to obscurity. Like the late John Lautner, another protegé of Wright, he cannot be readily categorized and has thus been largely ignored by editors and critics. As a maverick in his ninth decade, he craves recognition and the opportunity to build but proudly refuses to compromise his vision.

Kellogg’s last great project was commissioned by two artists, who found a site perched among sandstone boulders, overlooking Joshua Tree National Monument. The architect conceived a giant flower of overlapping concrete petals that enclose a soaring open space, an elevated master bedroom, and a downstairs guest suite. The structure seems to grow out of the boulders like the spiky Joshua trees that give this expanse of wilderness its name. Construction stretched out over many years, and the rough-textured shell was then enriched for another two decades by John Vugrin, a craftsman of rare skill from San Diego. Etched glass, sinuously

curved marble, wood, and bronze define an open work area, a sunken sitting room, dining area, kitchen, and bathrooms. The pool terrace was transformed into a glass-enclosed spa.

Chance played a large role in the creation of this extraordinary house. Jimmy and Beverley Doolittle acquired the four-hectare site in exchange for a flat plot on the street that would have been much easier to build on. They saw several of the houses Kellogg had built in San Diego and invited him to drive up to Joshua Tree. He chose the ridge as the ideal location, then sketched an open, light-filled space on a yellow pad. Aerial photographs were combined with land surveys to create a site model as the plans grew from the initial concept. Little did the Doolittles realize what they were embarking on. To describe the experience, they quote a line from science-fiction author Ray Bradbury: “you jump off a cliff and build your wings on the way down.”

No contractor would assume responsibility for such an audacious design in so remote a location. Instead, the owners hired a supervisor and paid him for time and materials, without setting a deadline. A team of unskilled workers figured out solutions as they went along. It took three years to cut the rock, lay a concrete pad, and construct a driveway, while leaving many of the boulders in place. Twenty-six hollow columns are deeply rooted in the rock and fan out to form the overlapping planes that block the sun, while admitting refracted light through the glazed spaces between. Steel and concrete withstand the desert climate much better than wood, and neoprene joints allow the glass to expand. Terraces extend out to either side, shaded and protected by the house from fierce desert winds. There’s an architectural promenade from the road, up a winding paved path, and through the interior spaces to the wall of rocks behind. The house is a place of grandeur and mystery; a total work of art, seamlessly fused with nature at its most sublime.

From the rusted steel fence and a gate that resembles a dinosaur skeleton to the ornamental

Michael Webb was born and educated in London. He was an editor at The Times and Country Life, before relocating to Washington DC in 1969 as AFI Director of National Film Programming. The French Government named him Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres for his services to French culture. In 1978, Michael moved to Los Angeles and left the AFI to write and consult on the arts. He curated Hollywood: Legend and Reality, the acclaimed Smithsonian exhibition, which toured to leading museums in the USA and Japan, wrote the companion book, and created film sequences within the exhibition. He also produced an Emmy-nominated television special, The Greatest Story Ever Sold.

Michael is the author of 28 books, most recently Architects’ Houses, and Building Community: New Apartment Architecture. Previous titles include Modernist Paradise: Niemeyer House, Boyd Collection, Venice CA: Art +Architecture in a Maverick Community, Adventurous Wine Architecture, Art/ Invention/House, Through the Windows of Paris, Modernism Reborn: Mid-Century Modern American Houses, The City Square, and Hollywood: Legend and Reality. He has contributed essays to many other titles, as well as to travel and architectural journals in the US, Europe, and Asia.

All photographs were taken by the author, except for the image of Fire Over London from the Mary Evans/Grenville Collins Post Card Collection (p10); the poster for An American in Paris, MGM via All Posters (p11); the Ohio Theatre by D.F.Goff (p 44); the Gilardi House by Rebeca Mendez (p 82); and Marina One by H.G. Esch, courtesy of Gustafson Porter + Bowman (p 104). Back cover: The Churchill Arms pub on Kensington Church Street, London.