BY PAUL GOLDBERGER

The title of this book is Modern to Classic II, picking up on the theme of Landry Design Group’s initial book of a decade ago, Modern to Classic That title was chosen to indicate the range of Richard Landry’s work, which has always had much in common with that of the most talented and committed eclectic architects of the American tradition: architects like Delano & Aldrich, John Russell Pope, David Adler, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, James Gamble Rogers, Cass Gilbert, Carrère & Hastings, and Warren & Wetmore. They were designers who moved easily from style to style, with little concern about whether they were designing a house in the style of the Italian Renaissance or that of Tudor England. What garb their houses wore was something they were generally willing to leave up to their clients. What mattered most to them were the things

underneath—scale, proportion, light, materials, the floor plan, and perhaps most important, space and how we move through it, all the fundamentals of architecture, the things that have always meant more than style. These architects all knew, as Richard Landry knows, that a Spanish Mediterranean villa or a Georgian house or a French château can be well-proportioned or badly proportioned, that it can be well detailed or badly detailed. The difference comes not from the choice of style, but from what the architect does with it. And Richard Landry by and large has known how to make the most of whatever style he works in.

All of that said, this new book might almost have been called Classic to Modern, inverting the earlier title, because while the array of styles is still present—there are some excellent traditional houses to be found

in these pages—it has been clear for some time that Landry is moving, slowly but steadily, toward a more modern form of expression. No, not all of his recent houses are full of glass, not by any means, and I suspect that he will always be designing in a range of traditional styles. He enjoys all of them too much. But there is more glass, and more openness, in his newer work, and in almost all of his newer houses, whatever the style, we see and feel his buildings as shapes, not just as exercises in one architectural language or another. They come off as clearer, less fussy, and more self-assured than his houses of a decade or more ago.

The spaces flow well from one into the next, and the overall massing of the exterior is almost always a well-crafted composition. Landry houses may be visually striking, but they are not visually awkward.

Quite a number of his new houses do use the language of modernism, a language that by now, of course, is worthy of being called a historical style itself, since it owes much to the early experimental modern architecture of Europe and the United States, some of which is now a century old. As Landry, in the tradition of the great eclectics, has taken historical styles and adapted them to contemporary American life, he has done the same thing with modernism, showing as vividly as in his traditional work that he is not a copyist at all, but an imaginative synthesizer. The cold, white starkness of early modernism is not the theme of his modernist houses. Neither is the rough, heavy concrete of Brutalism, or the swooping curves of midcentury futurism, or the tensile energy of midcentury’s Case Study Houses, so important to the architectural history of Southern California.

But all of these things are somehow present in Landry’s new work (as they are visible in the striking and expansive new office building he designed for his firm on the west side of Los Angeles). They represent a kind of genetic heritage that he has absorbed, and begun to use to create something new, just as he has used the genetic material of Spanish Mediterranean to make of those styles something new and right for the life lived today. In a house like the Collingwood Residence, one of the finest houses in this new volume, there are hints of John Lautner and Richard Neutra, two of California’s greatest modernists, but no one would mistake this house for the work of either of these architects. Landry, like all good architects, has taken in the influence of his predecessors and transformed it into something that is entirely his own. This house is not restrained by any means; indeed, it has a panache that represents Landry at his best, here bringing the flamboyance of much of his traditional work to the challenge of reinterpreting southern California modernism.

The house is beautifully sited, making the most of one of those challenging, steep hillside sites that are characteristic of Los Angeles, and that in many other cities would be considered unbuildable. The skill with which Landry has integrated a large, multi-story house, complete with a circular motor court and a large garage, into a tiny site stands as a reminder that, like all good architects, he is also a solver of practical problems, and that he is able to perceive buildings not only in terms of their façades and their floor plans, but also in terms of how their pieces fit together vertically. He understands sections, and he takes an architect’s joy in being as creative here as in his plans and details. The result is a house that is perched exuberantly over the city, looking out over the expanse of Los Angeles with a drama that calls to mind Pierre Koenig’s legendary Stahl House nearby, the house that, thanks to Julius Shulman’s legendary photograph, has always embodied the aspirations of Los Angeles modernism.

Where the Stahl House was relatively modest, the Collingwood Residence, like almost all of Landry’s work, is extravagant, designed for a client with large ambitions and an ample budget. Yet Landry is able to work under tighter conditions; one of the best modernist projects in this

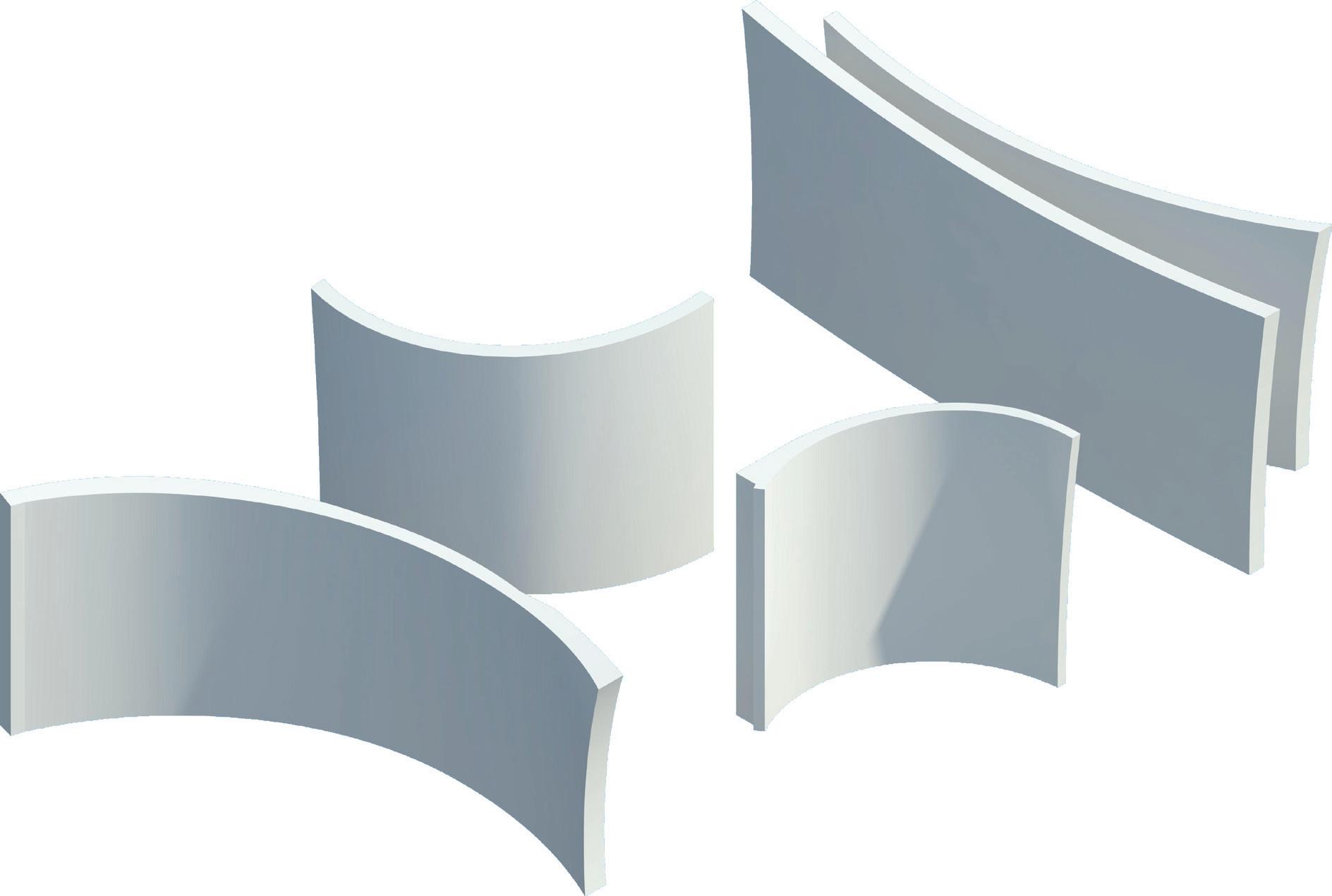

book is the Sea Level Residence in Malibu, which is squeezed onto a tight oceanfront site and yet addresses the Pacific with the same openness with which the Collingwood house embraces the entire city. The same skill for making much out of a smaller footprint is visible in the lovely studio barn on the property of Landry’s Brady-Bündchen Residence II, in Boston, a small wooden structure that manages to combine both serenity and energy, as well as to sit comfortably beside a much larger traditional villa. The ability to work on a confined site brings even more exciting results at the Samson Beach House, also in Malibu, now under construction and presented in the final section of this book, “Works in Progress.” Here, in a composition of curving walls, Landry manages both to be contained and to break free with a real sculptural energy.

The final section of the book gives an intriguing indication of where Landry is heading. There are a number of modernist houses, but there is no more a single modernist direction than there is a single traditional direction in his work: he is playing with everything, from the abstract masses of the Bell Canyon Residence in Ventura County to the wild, curving skeletal structure of the Aronowitz-Chalom Resi-

dence in Beverly Hills to the angular James Residence in Malibu, where, as at Samson, Landry experiments with the idea of the wall as a sculptural element on its own, this time as something angular, not curving. There is the Rosen Residence, another modernist villa in which grandeur is rendered in sleek form, perched on a dramatic hillside. And then there are what Landry calls his “transitional” houses, buildings that are neither demonstrably modern nor traditional, but seem somewhere in between, of which the most striking is probably the Xanadu residence in Beverly Hills, which plays on the 20th-century Hollywood Regency style, and which is, for all intents and purposes, a stripped-down version of a traditional French classical château. There is nothing wrong with this; architects have been stripping down classicism to find a modernist heart beating inside it since the 1930s. So here, too, Landry belongs to a tradition—but a tradition to which, as with all others, he makes his own contribution, and brings his own creative spark.

It is a spark defined, in the end, by his enthusiasm, and by that of his colleagues at the Landry Design Group. Landry does not work alone: not the least of the things he has in common with an earlier generation of American eclectic architects is that he has built a large, diversified practice around exceptionally skillful and committed partner and associates who share his love of the whole of design, ranging across style, and his ability to deploy all of the elements of architecture. Landry’s practice, like the eclectic architectural firms of earlier generations, is a studio of active practitioners, not an atelier based around a single superstar. As in those firms, Landry sets the general design direction, but the outcome of any project is a shared effort.

To the Landry Design Group, the world is a vast smorgasbord of architectural possibility, and it is clear that Richard Landry and his colleagues enjoy all of it too much to rule out any chapter of it. Their architecture, whatever its style, is celebratory, which is why Landry may be the least cynical architect around today: he wants to embrace all of the history of architecture, and to help his clients experience what he himself seems to feel, time and time again, with every project, which is the thrill of discovery.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

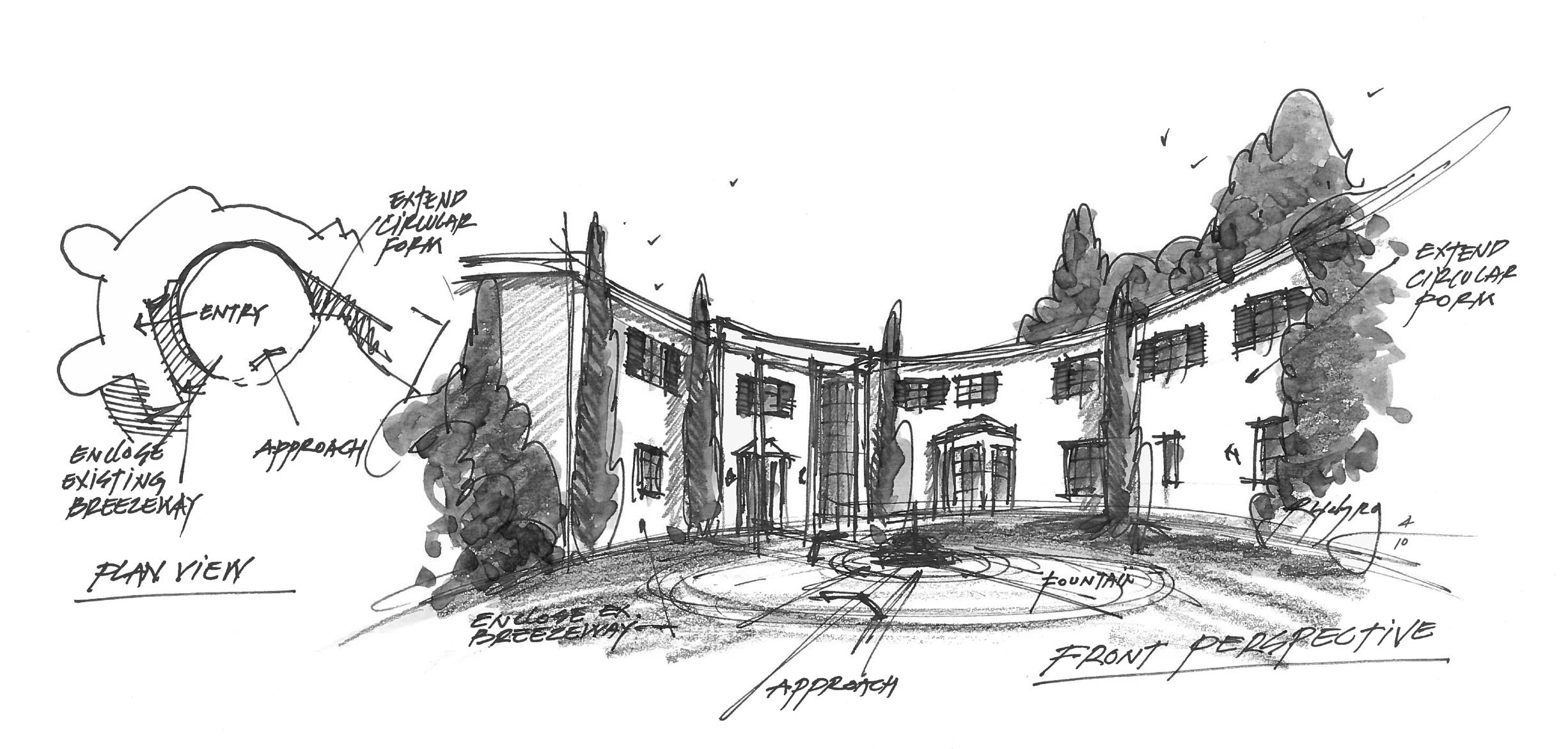

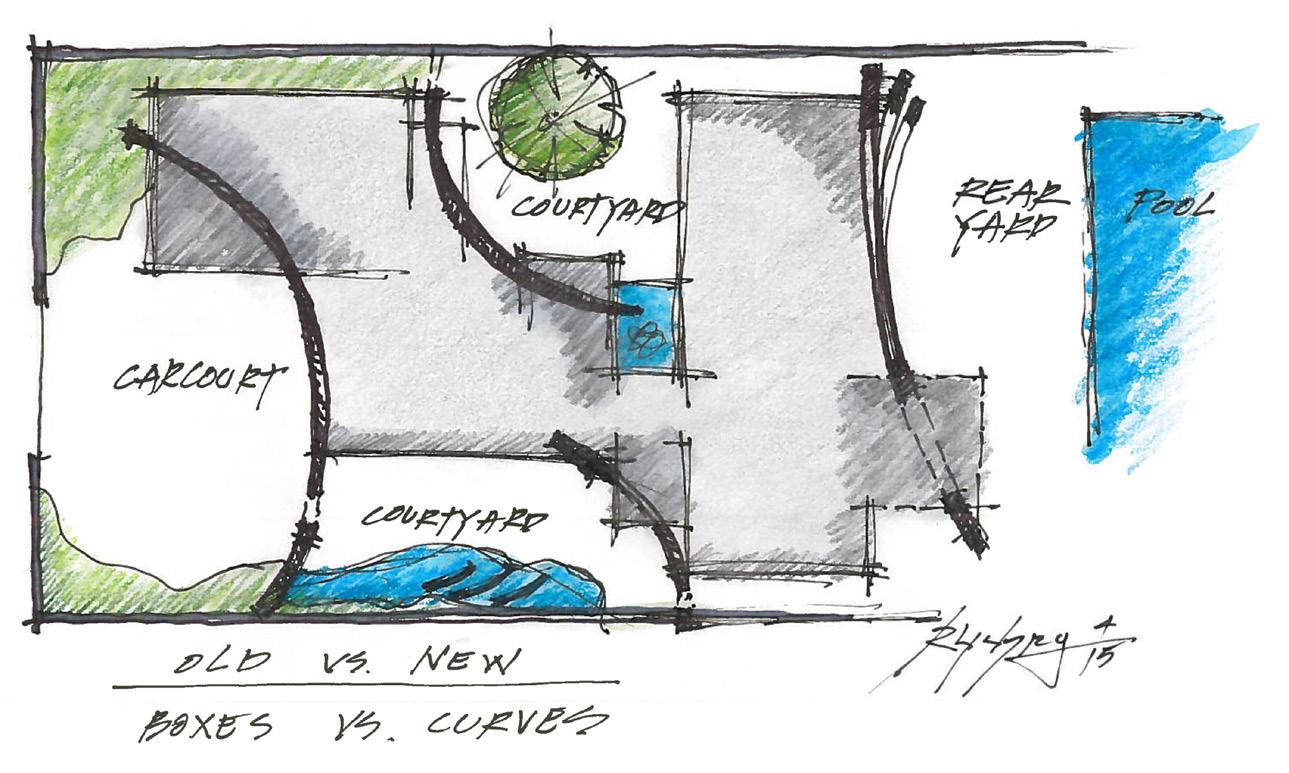

The request was a unique one for Landry Design Group: to renovate an original house in a Los Angeles canyon by respected architect Paul Williams. Before approaching the firm, the clients had lived in the house for several years and fully understood its benefits and drawbacks, which gave them a clear sense of what the renovation should entail relative to their lifestyle. They wished to retain the home’s Hollywood Regency bones and semicircular flow, but needed to add a new master suite and larger bedrooms for their children, as well as introduce a family room that better related to the more formal living and dining rooms. The firm answered with a cohesive layout that resulted in a more pronounced interpretation of a circular plan, plus an expanded garage that would connect to the house, a subterranean home theater and wine room, a new pool house, an upstairs gym with its own terrace, and, on the ground floor, a grand covered loggia.

In addition to the spatial requirements of the renovation, more potential improvements were immediately apparent to the firm. Ceilings were oppressively low, rendering the rooms dark. Windows were small and, typical of homes of the era, the house was not as well connected to the outdoors as a more contemporary structure would be. The

firm raised ceilings throughout, and opened rooms to the exterior. The entrance, living room, and parlor now step out to the covered loggia through bifold doors that open the length of entire walls. Wherever possible, portions of the existing house were kept, such as the inward-curving entrance façade or details like the bay window projecting from that façade, formerly part of the kitchen and now the source of natural light in the breakfast nook.

Spaces were based on the study of the rhythm found elsewhere in the original plan. Take the parlor, for example: its graceful curve now matches that of the living room, whose parameters remained largely intact. Within that curve, as elsewhere in the interior scheme set by interior designer Thomas Pheasant’s firm, a sofa specially selected for the space captures the essence of the architecture. The Regency references in the original home were carried over to the new pool house, which has a curved tower that links directly to those shapes in the main house. The residence offers an updated design for the clients’ lifestyle, while keeping the spirit of the original home.

Opening photograph The villa borrows from Andalusian architecture, with a tall entrance and porte-cochère to protect the clients from weather. 01 Reclaimed antique Spanish brick was used for the base of the gatehouse. The exterior walls are smooth plaster and the roofs are antiqued tile. 02 Landry Design Group modeled the lanterns in the courtyard after some the clients had admired on their travels. 03 The dining room opens directly onto the courtyard. An oak tray ceiling offsets a door surround in chengal (a Malaysian hardwood) and limestone walls.

The great arc walls of sculptor Richard Serra provided a point of inspiration for the development of the forms that cut through the Samson Beach House in Malibu, a remodel of an existing oceanfront home. From the street, its effect is immediate: a cube covered in reflective glass (the garage) punches through the colossal main plane, creating interest on arrival. A second reflective cube intersects more planes on the ocean side, and a third cube housing the entrance, made of transparent glass, disappears into another curve. On the rear façade, a curved plane breaks away from the house, its sense of movement resembling a sail carried by the wind.

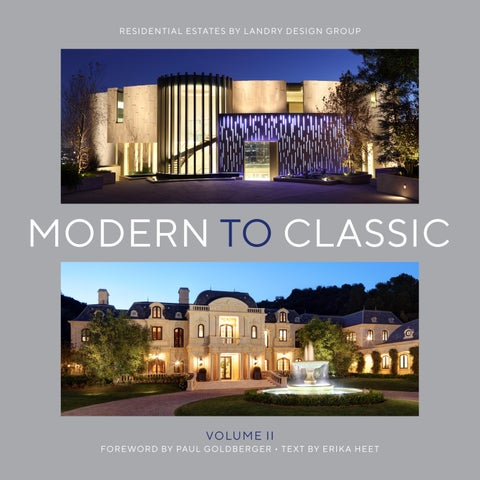

Modern to Classic II: Residential Estates by Landry Design Group explores the Los Angeles firm’s recent work, defined by an eclectic range of references and styles. Emphasizing the unique stories that inform each of the projects, the monograph’s 15 chapters—each dedicated to a single completed residence and opening with a conceptual sketch by principal Richard Landry—demystify the process behind creating the grand estates the firm has become known for. From a modern steel and glass aerie perched above L.A.’s Sunset Boulevard to a lakeside stone villa in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, the houses selected embody the spirit of those who inhabit them. A special section, Works in Progress, previews 25 current projects from the firm consistently sought for its ability to collaboratively intuit architectural styles, siting, and materials in structures that innovatively reflect the area vernacular and elevate the imaginations of their clients, who include celebrities, creatives, and industry leaders.