ORO Editions

Setting the Stage: The Social Lives of Urban Landscapes

Chris Reed

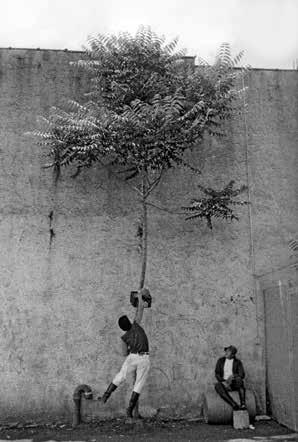

Kids are amazing. They come with no pretenses, few preconceptions, few socializations. They don’t know things in the way that they will as they grow up, they don’t understand that certain things have certain uses—they encounter the stuff of the world for what it is: shapes, colors, tastes, smells, sounds, three-dimensional figures in space—all things to touch, to taste, to smell, to kick, to sit on, maybe to lick, to play with, even to test and challenge, and to explore on their own terms.

My own children, early on, would create an adventure of simply walking down the street. As many of us have, they would make games around sidewalk cracks, and of hopping from one utility cover to the next, completely unaware that these heavy, dark discs in the paving were portals to an infrastructural underworld that powers and services the city. Curious, they responded unabashedly to the world they encountered, exploring their environment through their senses, before they were conditioned to understand functions, relations, associations, customs. They invented uses and meaning for themselves.

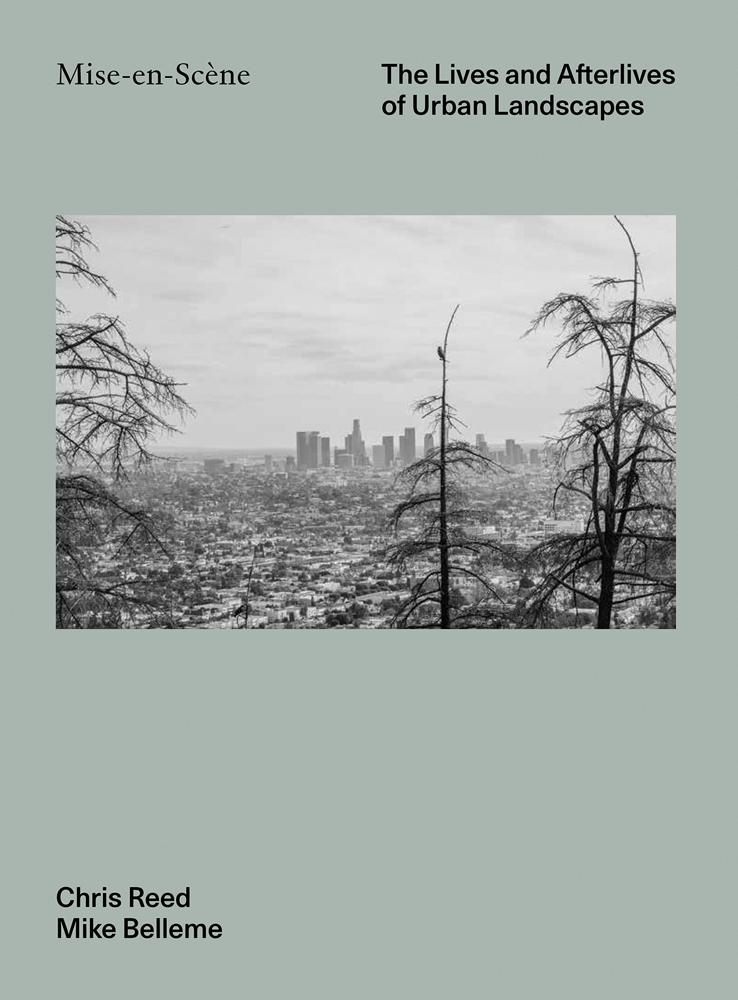

This unselfconscious appropriation of things has always fascinated me. In school we were often told to sit still, sit up straight, not to lean back—as if there were only one way to sit , as if we were all comfortable in standardissue school furniture, and even though we all have different body sizes and shapes. Certain seats are more comfortable for some of us than for others. And sometimes we want to sit improperly, to slouch, lounge, or relax, or sit with someone in our lap. We find different ways to sit on a log, lie on a lawn or at the beach, recline against a tree. We adapt to the conditions around us and put them to unintended use to suit our purposes. This is what is happening in Herman Hertzberger’s photo of two ladies, lunching in front of a cafe and sandwiched between two parked cars rather than in the cafe itself or as part of the cafe’s sidewalk seating.

ORO Editions

People like them find their own place in this world. We appropriate the stuff around us and adapt it and our own bodies to the tasks or desires at hand.

In the 1970s, William Whyte extensively studied the behavioral and social tendencies of people as well as our ability to adapt flexibly and shared his findings in his The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1980). Why te’s studies of the ways in which people gathered on the plaza and ledge in front of Mies van der Rohe’s

Photo by Herman Hertzberger

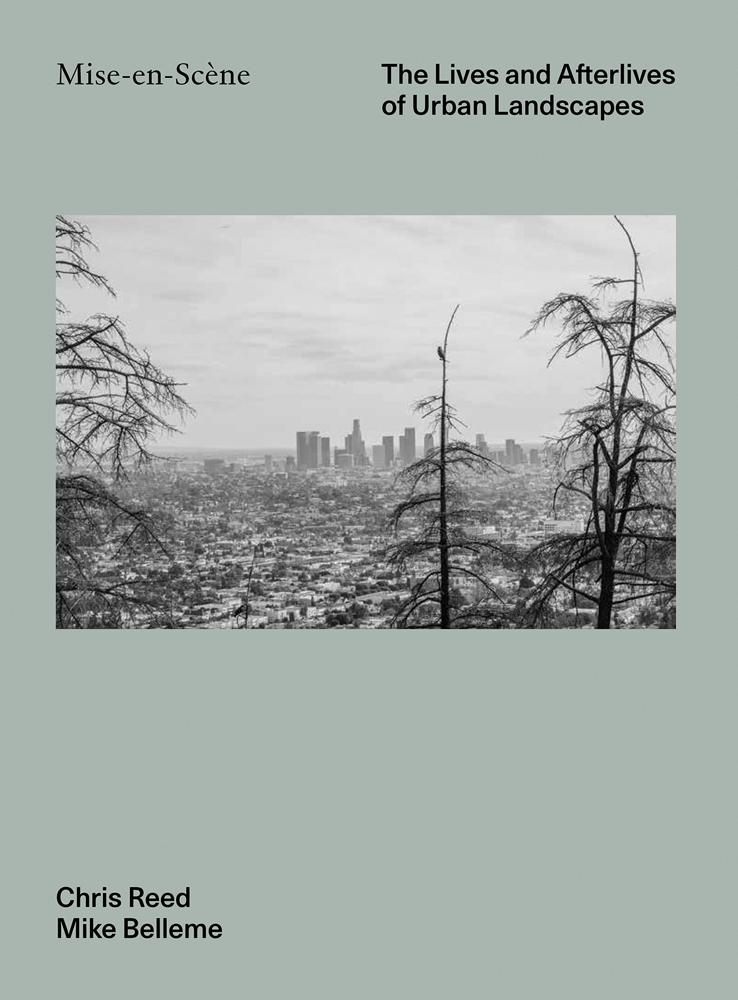

Photo by Jules Allen

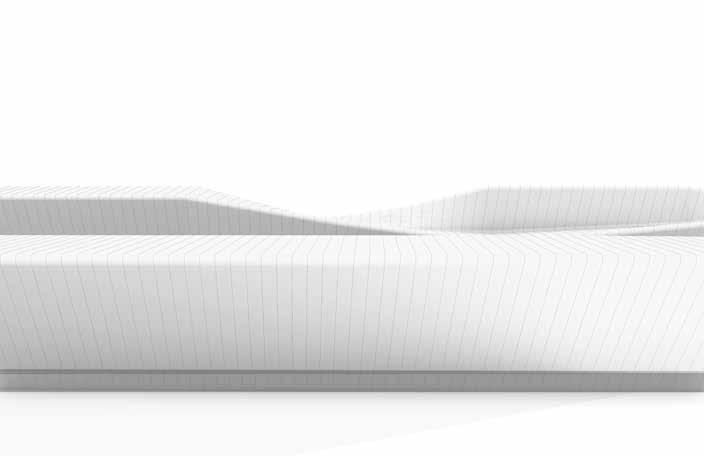

Harvard Science Center Plaza Benches, drawing by Stoss

Seagram Building in New York, for example, highlighted human, behavioral adaptations to this particular space and its environment, and demonstrated more broadly how people can and want to act in the public realm of the city. Whyte studied the evolving relationships of people’s chosen sitting and gathering locations on the plaza and then mapped his findings with changing sunlight and shade over the course of the day; to work and lunch and commuting schedules; and to each other—noting how folks would use the space differently at different times and in response to different microclimatic conditions and social schedules.

This work is significant to me as a watchful observer of people and the urban scene and of the unfettered ways in which people interact with their settings and with each other. It is also significant to me as a designer to understand how what we design—whether a bench, a public space, or an entire district of the city—might pick up on the innate, behavioral characteristics and habits of people (and of larger social/environmental systems and dynamics) as a star ting point for thinking about how we shape people’s environments.

ORO Editions

As informants to physical design, we can learn by observing closely, and we can anticipate by applying our research. Choice, diversity, flexibility, and adaptability—of designed elements and spaces and of the people who will come to inhabit them—are critical informants for a place to be conducive to richly changing social and collective uses. But we must also leave room for the unanticipated, the unexpected—and those things that are simply beyond our control.

Photo by Mike Belleme

networks, and ecological dynamics are, together, the starting point for our work at Stoss and for what we try to instigate, initiate, or interact with as we design and program public space projects. They also represent the larger scene within which our work—and life itself in the contemporary American city— is set.

commercial street we’ve witnessed Black motorists stopped for no apparent reason. Yet my kids live an otherwise privileged life in what we generally consider an open, multiethnic, and somewhat multiracial community. Like many other parents in far more threatening circumstances, I have deep concerns paired with an enormous amount of hope and optimism about the lives my kids are leading and will lead, about the opportunities and challenges all three of them have ahead. Will their skills, intellects, efforts, and personalities bring them the rewards of a happy and productive life, or will skin-deep judgments, policies, and perceptions negatively affect what they can and will do, or worse?

Racial prejudices and social inequities run deep across America and around the world, and continue to have a negative impact on the daily lives of and opportunities for young black- and brown-skinned people throughout the US and for immigrant and migrant populations nationally and globally. The last few decades have seen unprecedented advances in race relations and public discourse on the social and economic inequities built into systems of government, politics, and other institutions—and yet much of the hatred and contempt behind these historic injustices (fueled especially by a President whose power and authority seem to rest on chaos and inequity) has also surfaced publicly. In the spring of 2020 with its pandemic-infused restlessness and frustration, systemic racism has reemerged front and center in American life, triggered once again by the senseless killings of Black people by police. Optimistically, it has also inspired a wave of protest and activism—with a demand that we consider how institutional power and decision-making benefit some at the economic and health expense of others. Societal and political concerns are only one part of all the work that has yet to be done.

My life has grown more complex over the past two decades. I have three interracial kids (including two 6'-1" boys who read as Black) growing up in a post-Ferguson, post-Trayvon Martin world, but in the relatively safe and liberal town of Brookline, Massachusetts, right in the heart of the Boston area. Within this seemingly innocuous setting, my Black wife has been challenged by police officers on our own property, and on Brookline’s main

ORO Editions

On other fronts, cities, people, the environment, the globe are all fraught with rapidly increasing challenges, brought to a head by political and economic forces that maybe are not always looking out for everyone’s best interests. These tensions, between societal, racial, and environmental advancement and retreat, the battle for the hearts and minds of people, continue to play out in so many of today’s public discussions, especially about new development, open space, and planning and design strategies in cities. This is where broader societal questions and battles—very

Photo by Frank Gohlke

Photo by Jules Allen

much in play in the world at large as well— infuse my professional work, my teaching, and my day-to-day life as husband, father, and city-dweller. And this book is where those lines come together: a photojournalist’s depictions of the people and urban landscapes of seven cities across the US intersecting with the work we do at Stoss, and as impacted by the politics and racist planning policies, currently looking forward from the COVID pandemic, ongoing racist attacks, social unrest . . . . The stages on which we work, the actors we engage with, are already in motion when we arrive. Our work

begins many acts in, and our appearances are sometimes relatively short. You might think of our work as understanding the scripts and dialogues as they are playing themselves out; interacting with those on stage and the forces behind the scenes in ways that both respond to and shift what is at work; re-setting the trajectory of the play in ways that sometimes reveals what is hidden; and giving new voice to those who have been off stage—all allowing for new and healthier interactions among urban dwellers, their cities, and the environments in which they live.

ORO Editions

Mise -en-Scène is about the social lives of cities and the people who live in them—and the urban, social, political, cultural, and environmental contexts in which they are situated. Its photographs document, interrogate, and tease out the issues, tensions, joys, everyday activities, celebrations, and intimate moments of people—people who are getting by, looking for opportunities, looking for social interactions of various sorts and for moments to

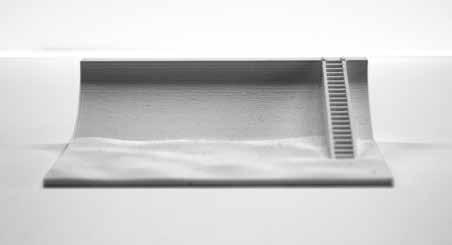

Galveston Seawall, model by Stoss

Drawing of current and projected storm surge events at Galveston Seawall by Stoss, atop photo by Mike Belleme

explore and to be liberated, or looking just to be themselves.

It’s a book about the diverse and complex issues that shape and impact cities today: current and impending effects of climate change, rapid economic redevelopment, potential displacement, homelessness, increasing cultural and ethnic diversity, social and racial inequities, social and cultural life. This book is about life itself: our lives lived and experienced as urban dwellers, as sentient, animate human beings, as social beings, as belonging to the flora and fauna of an increasingly changing and challenging environment. And it’s a book about what we, as designers, landscape architects, and urban strategists at Stoss encounter in our everyday worklives. The lives and situations depicted in the photographs here set the stage for the work we do in cities, just as our designs and projects set up new or altered conditions that themselves prompt new responses, new actions, new dynamics, new scenes that continue to play out long after we leave.

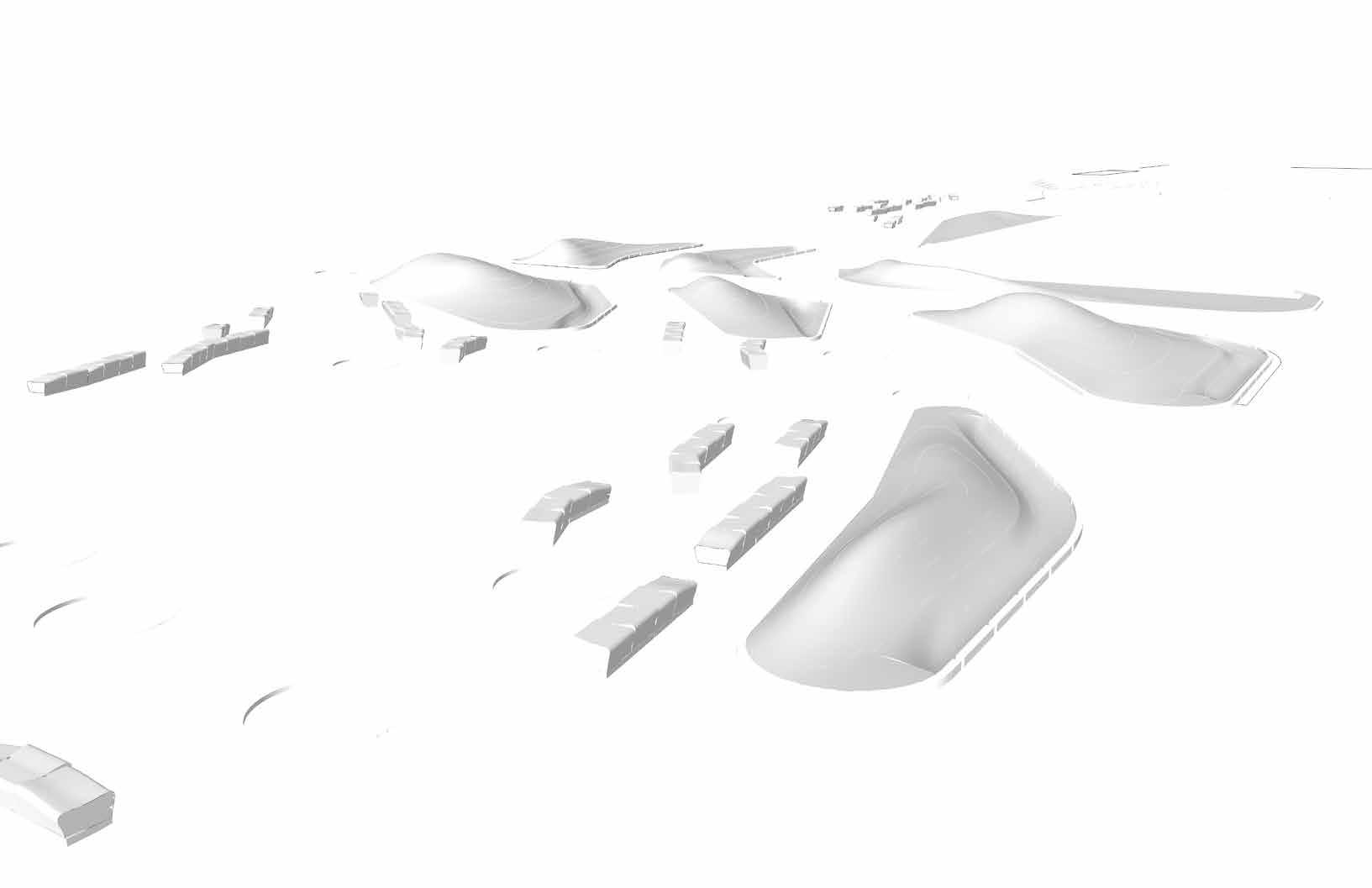

Belleme’s photographs not only intimate where we begin as designers and urban strategists; they also document the afterlives of the places we have designed or that our designs have activated. Mise-en-Scène’s accompanying drawings depict this in relationship to the physical features and infrastructures we discover on a site: the Galveston sea wall, for instance, with the many, local, current, and projected levels of tides, rising seas, and storm surges. They depict the very physical elements that we as designers have direct control over, such as a bench, wetland terraces, a civic plaza, and the like, and that we articulate to both respond to those underlying conditions and set off an entirely new set of social and environmental dynamics that we hope will contribute to a richer, healthier, more robust urban landscape.

More importantly, this is a book about contemporary urban life in the American city. Belleme’s photographs offer scenes from a pre-pandemic urban America from the standpoint of a photojournalist, in keeping with a lineage of street photographers that date back over a century. The five interspersed essays by contributors whose backgrounds range from curator to ecologist, from designer to social advocate and artist to critic, were written during the pandemic and the many calls for social and racial justice for Blacks and for all non-white people. The Stoss drawings capture the wide range of scales

and environments that we work in, and illustrate especially the ways we document our proposals for projects intended to work with the dynamic milieus in which we work. They capture the multiple tools and techniques we use to analyze, communicate, and project— and focus on those parts of a project or collaboration that we control, that we inscribe—with the hope of triggering anew the social and environmental forces that are in play. Quotations from a broad canvas of literary, design, and environmental writings bring forward some of the intellectual and cultural provocations of Mise-en-Scène ; short outtakes from city-dwellers involved in the outreach and engagement processes around Stoss’s work provide a real-world perspective from a multitude of competing voices that are at work informing the futures of these places.

In this way, Mise-en-Scène is a bit of a scrapbook, a collection of artifacts and documents that are not necessarily intended to create logical narratives, more intended as a curated collection of stuff that might reverberate, one thing off another, to offer multiple readings, multiple musings, multiple futures on city-life. While design is present here and there in the drawings and some of the texts and photographs, the book captures the broad contexts in which designers work and the issues we face in contemporary cities and politics—and therefore addresses a broader audience of city-lovers, photography buffs, activists, sociologists, cultural aficionados, art lovers, and critics. It is intended to engage others in conversation about cities and landscapes to ultimately continue to inform the ways in which we, as designers, can think and work—and deliberately not limit those conversations to our own circles in design.

ORO Editions

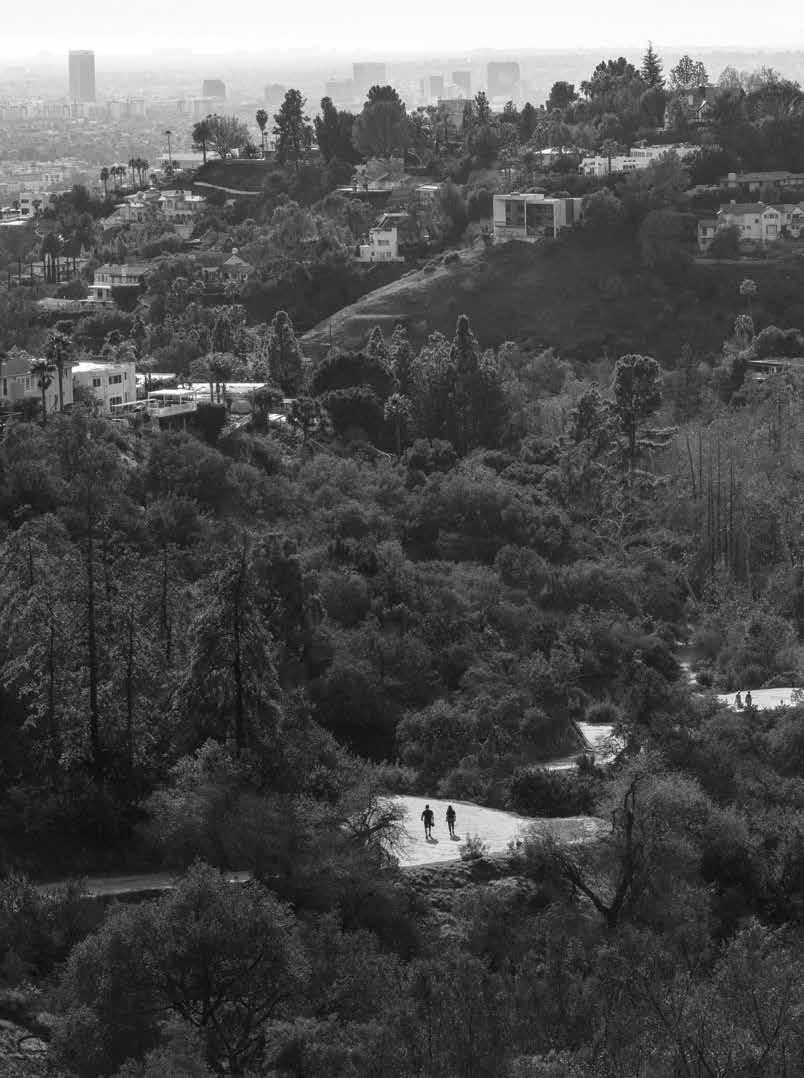

Mise -en-Scène , then, turns to the physical and social conditions of seven distinct cities across the United States—Los Angeles, Galveston, St. Louis, Green Bay, Ann Arbor, Detroit, and Boston. It explores the social lives that they give rise to, sometimes in spite of the environmental, social, cultural, political, and economic circumstances around. A collaboration between Mike Belleme, a photojournalist, and me, a landscape architect and urbanist, this book brings to light the challenges, tensions, hopes, special moments, and everyday activities of people who live and work in contemporary cities. It pictures some of the social, cultural, environmental, and economic challenges and changes that cities around

the world are facing today. It suggests both starting points for and some aftereffects of design work in the public realm, work that must confront both the realities of contemporary urbanism (including climate change, social and racial tensions, rapid development, and multiculturalism) and create new opportunities for everyday common grounds and places for all of us to interact directly with one another.

These seven contempor ary American cities range in terms of size, geography, politics, ambitions, and character. They represent a national cross-section but are somewhat serendipitous in that they are places where the Stoss Landscape Urbanism practice has worked over the past decade on strategic planning and design projects. In Mise-en-Scène , a west to east arrangement of cities, from Los Angeles to Boston, is meant to facilitate comparison and contrast. A curated set of maps, drawings, and diagrams by Stoss relate the various modes and methodologies invoked in crafting public spaces to respond to the conditions in Belleme’s photographs and to set up conditions for new forms of human interaction.

This book offers a more expansive idea of the potential influences on and implications or effects of design disciplines regularly practicing in and thinking about cities. While these cities are quite different from one another in terms of geography, size, population, people, climate, economics, ethnic composition, cultural heritage, lifestyles, etc., this project speaks to a remarkable interconnectedness

ORO Editions

across these geographies, scales, and situations: that the tensions invoked by a redeveloping and inundated waterfront in East Boston shares a story or a lineage with an emerging set of conversations on race and identity in St. Louis, with an impromptu workers’ rally on a beach in Los Angeles, or with White families living off the land in a predominantly Black Detroit; or that increasingly frequent street flooding faced by residents of Galveston Island is tied to the same forces that guide the design of a stormwater garden in Ann Arbor and a dry courtyard in Venice Beach; or that the detail of a bench in Green Bay shares an origin story with a mattress stuffed under an old bleacher in a Boston park, or with teenagers sprawled on a dock in Michigan. These kinds of connections are offered implicitly through the imagery of the different cities, and explicitly through drawings and cross-referencing around topics including ecology, water, social space, housing, and infrastructure. Introductory maps of each city, provided at a consistent scale for easy

Map of Boston by Stoss

Photo by Edward Burtynsky

Photo by Ansel Adams

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

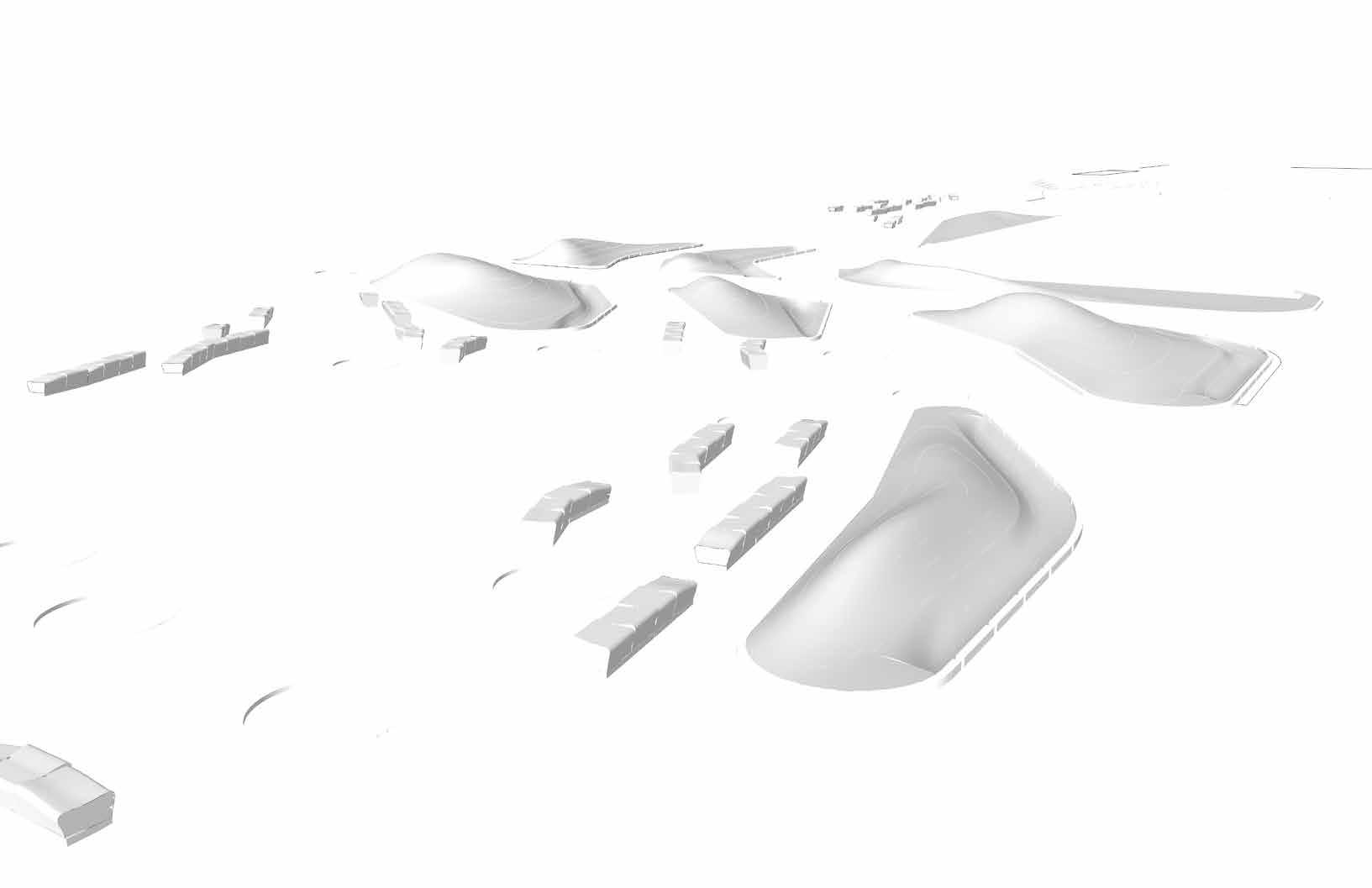

Circulatory flows of people and water amidst cluster of hillocks and seating, opening to large areas for gathering and flexibility. Landscape as teaching tool in an arid climate.

ORO Editions

Venice High School, Venice

ORO Editions

ORO Editions