ROBERT GERARD PIETRUSKO

Robert Gerard Pietrusko is a designer living in Somerville, Massachusetts. His research focuses on geographic representation and the history of spatial data sets. His design work is part of the permanent collection of the Fondation Cartier in Paris and has been exhibited in over 15 countries at venues such as MoMA, ZKM Center for Art & Media, and the Venice Architecture Biennale, among others. Pietrusko is currently an associate professor of landscape architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

geoscience, MILITARY SCIENCES, BOTANY

at the same time, suggest that the concept of “tactical media” should be understood as a dynamic site of differential inflection, shaped by diverse cultural experiences and histories. It is also important to recognize that tactical media, especially those of Indigenous Americans, also have built within them implicit languages that are not intelligible to all, and are articulated with what Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance” – native presence that “remains obscure, elusive and imprecise” yet works to renounce “domination, tragedy and victimry.”2

In this essay I approach Indigenous Americans’ tactical drone videos as vertical mediations – audiovisual discourses that enact, materialize, or infer conditions or qualities of the vertical field.3 These mediations demonstrate what is happening in the air, spectrum, or orbit, and how those happenings impact life on Earth. In doing so, they render intelligible material conditions and power relations of the vertical field, in the stretch of space from the air to underground. As Caren Kaplan crucially suggests, “airspaces,” which include the vertical, are often ambiguous and “are produced by assemblages of human and machine and can be apprehended through a broad array of material objects, elements, infrastructures, practices, and operations.”4 The analysis in this essay is intended to draw further critical awareness to the relations between vertical power, drone technologies, and publics, and to highlight the surveillance strategies and discourses of law enforcers and private security firms who criminalize civilian drone use by activists. The anti-DAPL protests expose state forms of vertical power that are immanent with the globalization of civilian drone technology, and make tribal sovereignty claims over air space more urgent.

Drone Warriors

Dean Dedman, Jr, also known as Shiyé Bidzííl (Hunkpapa Lakota and Diné), began using his civilian drone at Standing Rock in March 2016. Myron Dewey (Newe-Numah/Paiute-Shoshone) joined the effort in August 2016. The two were celebrated for their drone media work throughout the protests, and became known as “drone warriors” in the camps.5 Though there were other activist drone pilots, I focus on the work of Dedman and Dewey because their drone videos circulated widely, became integral to their activism, provoked police action, and won film awards.6 In his book Through Indigenous Eyes, Dedman recounts the first flight of his Chinese-made DJI Phantom 3 – purchased for 2500 dollars with his tax return. On March 11, less than one week after purchasing his drone, Dedman formed a drone video business called Drone2bwild, and by March 28 posted his first anti-DAPL drone video—Dakota Access Protest. The Run for Water—on his Drone2bwild Facebook page. Between March 2016 and January 2017, he recorded over 100 drone videos of various activities at Standing Rock – from gatherings at camps to phases of the pipeline’s construction, from incursions on sacred sites to law enforcers’ activities. He live streamed and archived these videos on Facebook and Unicorn Riot, and posted longer videos on YouTube and other platforms.7

B.W. Higman is emeritus professor of the Australian National University and of the University of the West Indies. He has doctorates in history and geography. An Australian, he lived almost 30 years in Jamaica and has published widely on Caribbean slavery and landscape history. His work on the spatial concept of flatness began with an interest in the Jamaican lawn, spread to the flatness of the Australian continent, and grew into an even larger project, discussed in his book Flatness (2017).

History, Design, Technology

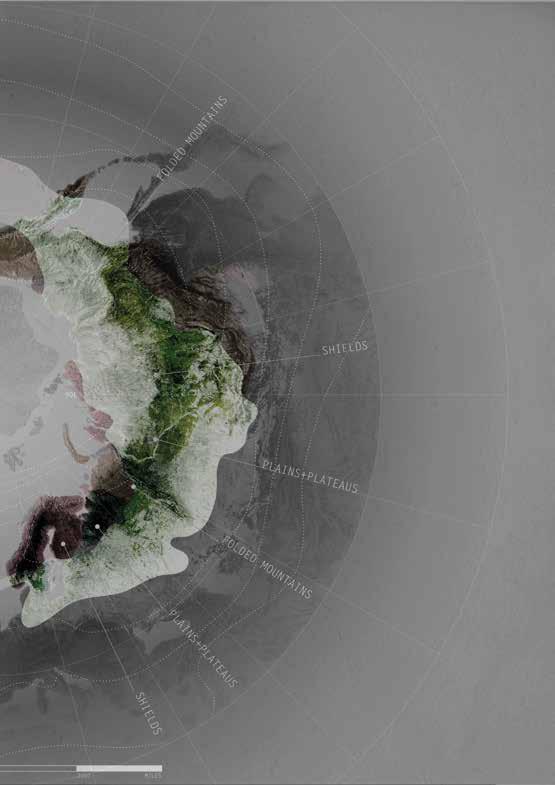

Crossing rough ground, in the absence of clearly defined pathways, in unfamiliar territory, we choose our steps carefully. Nature’s landscape is unpredictable, the surface full of hidden hazards: protruding rocks, sudden declivities, slippery slopes, snakes in the grass. Its successful negotiation, indeed our very survival, depends on close attention to navigational clues, leaving us little time to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of the larger landscape. When walking in a “landscaped” place, by contrast, we expect few surprises, few risks to life and limb, and feel able to lift our eyes to contemplate the world around us – or safe to stare at the flat screens of our phones. We follow hardsurfaced pathways built into the design and, most of us, obey signs directing us away from the seductive softness of carpet-like lawns: “keep off the grass!” If we trip on an unexpected upraised paver in a public pathway, workers are dispatched to grind down the offending stone, or we sue.

At the base of this contrast is flatness, a spatiality rarely found in nature but essential to modern life. For many of us in today’s world, almost every surface on which we move, on most days, is a flat engineered technology; our feet barely touch the rough ground. Indeed, flatness is a concept and a condition central to the entire architectural enterprise, and a key to many other aspects of modernity. As an abstract concept, flatness is applied not only in the physical work of engineering—moving earth and pouring concrete—it is equally important in visualization and design, not merely enabling simplified mental maps but also supplying the tools and techniques needed to communicate ideas to clients, and to satisfy surveyors, regulators, and lawyers.1

What is it about flatness that makes it so important and why does it have a special place in the spatial history of the modern

world? Broadly, the essence of flatness is invariance, a quality underpinning predictability and practicality, and contributing handsomely to profitability. In the modern world, flatness is valued for its reliable uniformity and relative lack of hazards, values that extend beyond the landscape to projects such as precision engineering and graphic design. These virtues spill over into concepts of social equality, justice, and fairness, exemplified by the level playing field. Yet flat landscape surfaces are often disparaged for their aesthetic blandness and baldness, their featurelessness, and indeed their emptiness.2

Negative perceptions of landscape flatness typically attach to broad vistas—deserts and plains—where topographic invariance can be viewed on a grand scale. These attitudes have something to do with the uncertainty of finding in such places the biodiversity needed to supply resources for survival, but also fears about getting lost in spaces lacking landmarks, going around in circles searching for waterholes or roadhouses. In contrast, local flatness is rarely disparaged or even noticed. In spite of these striking differences in landscape appreciation, one thing that is broadly common, whatever the scale, is a preference for pathways with surfaces as flat as possible to enable safe and speedy transit. Whether traveling through rocky mountains or across an arid plain, or simply negotiating a shopping mall, qualities of smoothness, straightness, and flatness are much to be desired. The modern engineered landscape caters effectively to these desires, ensuring efficiency and profit by constructing pathways that provide comfortable passage. Very often, these routes facilitate movement between diverse types of engineered sites—from home, to work, to shop—most of them, in turn, taking advantage of the profit to be made by building on a flat platform.

Noah Heringman teaches English at the University of Missouri. His publications include Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology (2004); Sciences of Antiquity: Romantic Antiquarianism, Natural History, and Knowledge Work (2013); and a digital edition of Vetusta Monumenta (2019). He is currently completing a monograph entitled Deep Time: A History

History, Literature, Design, Geology

Thanks to the efforts of gifted popular science writers such as John McPhee and Robert McFarlane, deep time is widely held to be synonymous with geological time. Many writings on the Anthropocene epoch presuppose this association, since the idea of a human-driven Earth system effects a spectacular collapse of historical into geological time. There are other deep-water currents in the time stream, however, and some of these have been mapped by ethnographers, literary critics, and science fiction writers including J.G. Ballard (The Drowned World) and Eric Temple Bell, who revisits the “illimitable desert” of the primitive world only to uncover an even deeper past of advanced civilizations fueled by limitless energy in The Time Stream (1931).1 Geological evidence suggests that the original, molten earth formed about 4.6 billion years ago, but this period is only about a kalpa in Hindu cosmology, a single day in the life of Brahma. Since Brahma is now about 50 years old, this makes our current world much older, well over 150 trillion years.2

Opposite: Artificial volcano at Dessau-Wörlitz's Island of Stone mid-eruption.

Following: "The Stone of Wörlitz," aquatint by Wilhelm Friedrich Schlotterbeck after Carl Kuntz (1797).

Deep time is older than geology, and crosscultural speculation about rocks and time merits renewed attention as a pursuit that informed the creation of the modern geological time scale. Even the Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772), a seemingly frivolous exercise in chinoiserie by the Georgian architect Sir William Chambers (1723–1796), has something new to offer a world in which geological “scenes of terror” are envisioned in earnest by spectators haunted by global warming and the catastrophic depletion of natural resources. Though blatantly inauthentic in many of its details, Chambers’s account of Chinese landscape design offers a distorted echo of Chinese practice in its treatment of rocks, as suggested by the following injunction to designers of gardens in a late Ming treatise: “At the foot of the pine tree are rocks and the rocks must be strange.”3 The most extravagant “scenes of terror” in Chambers’s imagined Chinese garden feature

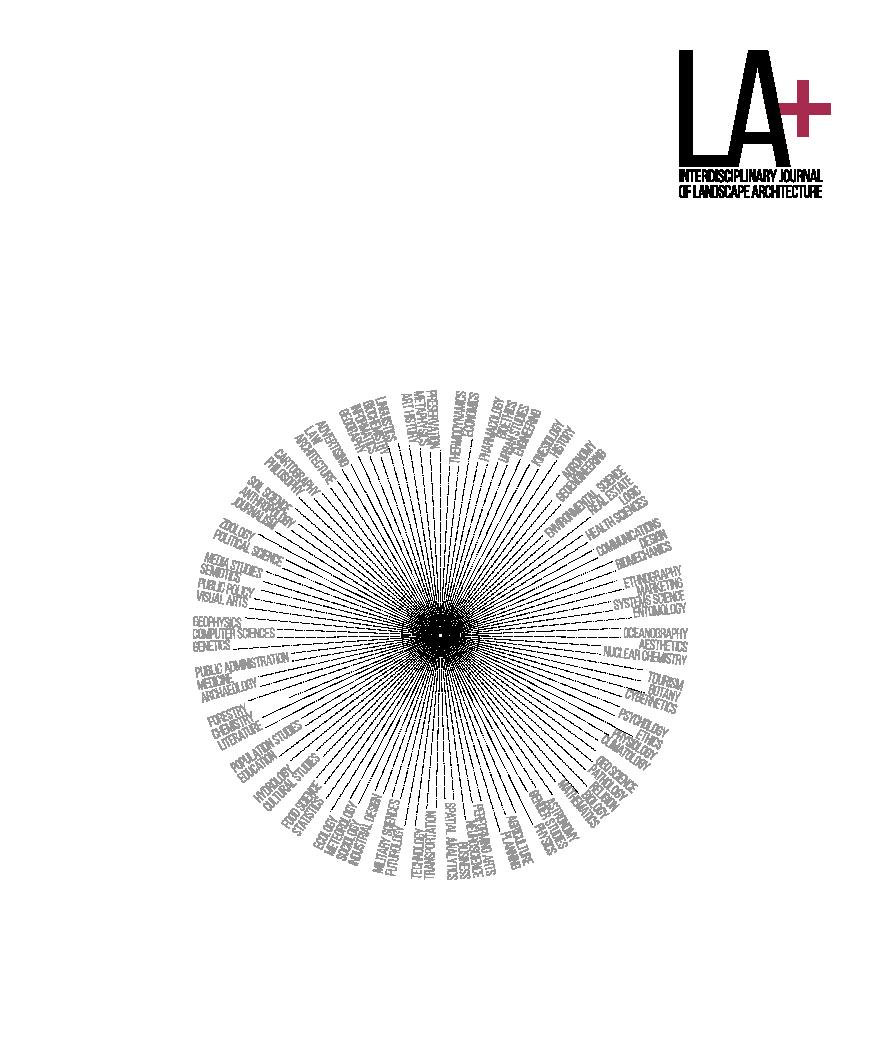

LA+ (Landscape Architecture Plus) from the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design is the first truly interdisciplinary journal of landscape architecture. Within its pages you will hear not only from designers, but also from historians, artists, philosophers, psychologists, geographers, sociologists, planners, scientists, and others. Our aim is to reveal connections and build collaborations between landscape architecture and other disciplines by exploring each issue’s theme from multiple perspectives.

LA+ brings you a rich collection of contemporary thinkers and designers in two issues each year. To subscribe follow the links at www.laplusjournal.com.